|

Egg

Ness

Judith Crispin

_______________________

No one can tell

Poems from Ahava (WSOY, 1998)

Lauri Otonkoski

Translated by Herbert Lomas

Books from Finland

And life went on, went on as a kind of weird fugue,

a forked path that drops across your eyes,

rejecting simple questions.

(....)

Yes, even if speech

is like trying to master a hundred-string guitar with ten fingers.

Even if stories

masked in words are no longer enough

for a time drowned in virtual dreams.

Even though, day and night,

the same perpetual dusk drifts a continent of ice over the city.

Nevertheless

I do think of something, with clenched hands,

when I come to the edge of the park.

That park is just a slice of the city,

humming nostalgia for the forest.

Under a tree a dog, its ears wearing

the same look as when

perpetual motion's being invented.

A tree's armpit

is singing three bought vowels,

and there's something else in the air,

some thread unwinding from the eye

of a winged being that's crashed into winter.

...(more)

20 poems [pdf]

Lauri Otonkoski

translated from the Finnish by Anselm Hollo duration press

_______________________

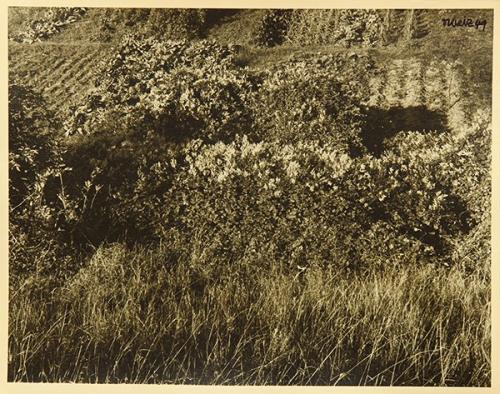

wind farm

photo - mw

_______________________

A Handful of Chisels: On Stones & Poetry

Claire Potter

In August 1913, Freud took a summer walk through the Dolomites with two friends, one of them being perhaps Rilke. In the idyll, Freud and the poet discuss how flowers and nature are prone to destruction and decay and possess an ill-fated beauty. And yet, in contrast to the poet’s pessimistic view, Freud sees value, and therefore a heightened beauty, in transience, arguing that scarcity and limitation only augment worth. He explains that what spoils an enjoyment of transient beauty was an antipathy to mourning.

The question of transience—as an expression of mourning—is almost a silent one, residing perhaps between the lines of all great poems—it is the question that stretches, enquires about, what we hold onto in a poem, what remains once the page has been closed. In some ways, it is the infans of the child before they learn how to speak, building word upon word, like raising stones upon a fledgling tower. A tower built, in Mallarmé’s terms, from words not ideas. Often these stones are not squared, their sides are not equal and their angles not perpendicular, leading perhaps to a sentence that wobbles, a wall that inclines, an architrave that bends. And here, residing within, is Freud’s sense of an oblique mourning, a transience we cherish and hold for a fleeting moment, before it is gone, or from another angle, indelibly remains.

(....)

Like ourselves, a page is opened to stand before us, words are read and lifted from a page, and then felled and put away, closed back into horizontal or vertical form. And the melancholy inherent to an imperfect memory of content when poem or book is closed, is made up for by the aesthetic object, like a stone stacked within memory, as an oblique, lost form requisite for re-entering, rebuilding, and rereading.

...(more)

via the page

_______________________

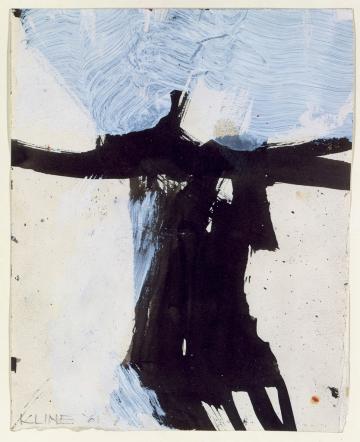

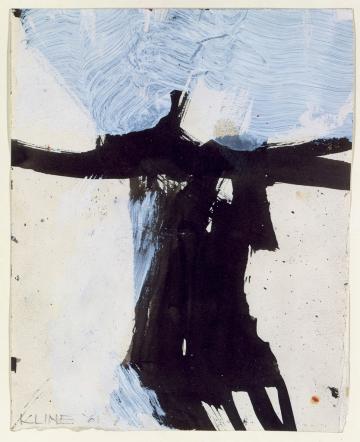

Franz Kline

b. May 23, 1910

_______________________

Lowlands

A Translation of "Ebene," a Short Story or Fragment by Thomas Bernhard

Translation by Douglas Robertson

...Many decades ago we should have relinquished what even if we go away and if we abandon and leave behind and extinguish, we now no longer can relinquish and abandon and leave behind and no longer can extinguish, because we no longer have the strength to do so, because our exhaustion is a total exhaustion. Decades ago we should have calmly abandoned these walls and these pieces of furniture and these books and papers and shut these doors and patiently exhaled this air in order to avoid having to inhale a single breath ever again and to be able to forget everything, as we can now no longer do. We have relinquished and abandoned and left behind and forgotten what we believed we had to relinquish, abandon and leave behind and ultimately forget; we have let ourselves go and we have gone away and we have gone under, but we have relinquished nothing and abandoned nothing and left behind nothing and forgotten nothing; we have in reality extinguished nothing whatsoever, because our parents did not inform us of or enlighten us about the fact that our life-process is in reality nothing but a process of illness. We were up above, in the company of our parents, locked up in our walls and in our rooms and in our books and papers and everything around us and in us was nothing but lethal and we are down below, without our parents, again locked up in these walls and in our rooms and in our books and papers and everything around us and in us is nothing but lethal.

...(more)

_______________________

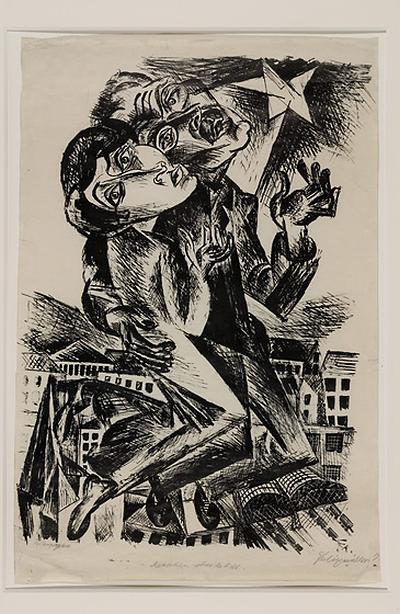

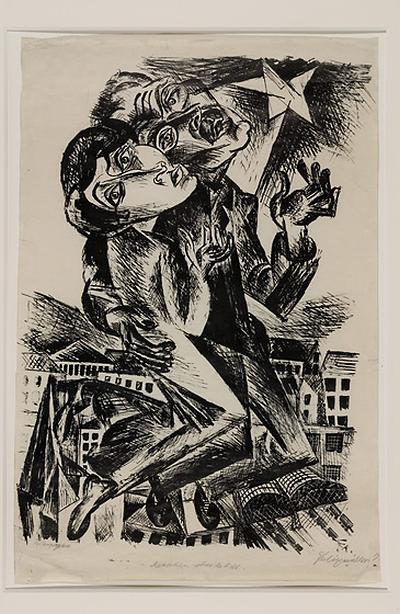

Men above the World

(Epitaph for Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht)

1919

Conrad Felixmüller

1897 - 1977

_______________________

Blogging Toward The Kingdom

Booze, rage and justice in the participation age

Joe Bageant

(1946–2011)

(....)

... it is the straight sober world and its truths that are hard. Alienation. Inner rage. Many of my essays were born in an attempt to communicate working class alienation, separation and rage -- which is the same as middle class rage, but self-described and expressed differently). Most of the liberal thinkers I know still do not grasp that the anxiety working people have, even the Tea Partiers, are rooted in the same things as their own. Yes, the right is definitely cruel. And yes, it can by now be called fascist. However, to deal with what has happened, one must come to grips with what produced the internal distrust upon which fascist empires are built.

The brutal way Americans were forced to internalize the values of a gangster capitalist class continues to elude nearly all Americans. Most foreigners too. This is to say nothing of how our system replaced our humanity with ideology, our liberty with money, and fostered fascist nationalism through profound degeneration of the people's mind and spirit. It's not as if one can ever escape that sort of thing, either by going to a place like Mexico, getting drunk or whatever. We are made in Americas' image, whether we admit it or not, and America's image is the face on a ten dollar bill.

(....)

It is now clear to me that the people's rage is a tool in the hands of the new electronic and digital corporate state. Its various channels, eddies and pools, regardless of type, can be directed toward all sorts of mischief and profit. Left or right, the angry throngs on both sides can be managed and directed. They can be sent chasing various injustices, denouncing evil characters on Wall Street, Times Square bombers, BP executives, or whatever, worked up into slobbering outrage over Sarah Palin, and thus kept divided and working against each other for the benefit of last gasp capitalism.

Once outside the furious drek of American political and economic life, and having finished the last book I will ever write, I found myself asking: "Why did the good in the American people not triumph? How can it be that so many progressive, justice-loving citizens failed? Their positions were well reasoned. The facts were indisputably on their side. Obviously, there was, and is, more going on than merely losing battles to demagoguery and meanness. Why do we lose the important fights so consistently? What has kept us from establishing a more just kingdom? Something is missing.

(....)

The blinking reptilian elites now own our entire material needs hierarchy chain, top to bottom. You eat, shit, work, fuck and die at the pleasure of their Great Machine. The presence of six billion others, most of whom are in the same situation, all but guarantees this as our material destiny on a finite and increasingly poisoned planet, before the big hasta la vista.

...(more)

photo - mw

RSS? It has come to my attention that the feed links aren't working. I don't know what is going on there but I'll see what I can do about it.

_______________________

The Far Field

Theodore Roethke

(....)

I learned not to fear infinity,

The far field, the windy cliffs of forever,

The dying of time in the white light of tomorrow,

The wheel turning away from itself,

The sprawl of the wave,

The on-coming water.

(....)

IV

The lost self changes,

Turning toward the sea,

A sea-shape turning around, --

An old man with his feet before the fire,

In robes of green, in garments of adieu.

A man faced with his own immensity

Wakes all the waves, all their loose wandering fire.

The murmur of the absolute, the why

Of being born falls on his naked ears.

His spirit moves like monumental wind

That gentles on a sunny blue plateau.

He is the end of things, the final man.

All finite things reveal infinitude:

The mountain with its singular bright shade

Like the blue shine on freshly frozen snow,

The after-light upon ice-burdened pines;

Odor of basswood on a mountain-slope,

A scent beloved of bees;

Silence of water above a sunken tree :

The pure serene of memory in one man, --

A ripple widening from a single stone

Winding around the waters of the world.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

from The Story of My Accident is Ours

Rachel Levitsky

presented at lemon hound

(....)

The trajectories set forth by such constraints, of suffering and the bloated plots to do away with suffering, for indecipherable, multiply gendered bodies, does not differ structurally from that which has been set for colonized bodies brought into The State originally from afar. The only difference is the one which is most articulated and most silenced—that occasionally a star possessing brilliance enough to be able to operate all the cultural and class systems at once does come along and this star has the force to cause the whole thing (on its very own terms) to rumble, at least quiver. Such a rattling has at times produced an amnesty in which doors open and a few others of us are able to rush in, or out, but for most of us, there is an ever denser charge—an injunction to buy our way out of our predicament by signing onto an ideology the best of us oppose vehemently and toward which the worst of us are ambivalent. We are led to believe and we convince ourselves this point of purchase is some minor detail, that if we know we don’t mean what we say then it will not materialize although here we fidget more restlessly even than our usual, we shuffle where we stand, nervous, suspecting, nearly knowing what we already do—that speech and knowledge are convolutes and cannot be any other way, that words, spoken or written, make it matter—each one having some sort of impact if not ‘meaning’ so to speak, despite ambiguity, complexity, politesse, magic tricks, good humor and the weather. Black, White and Left, Right can each mean many things so we are warned to not define these things narrowly or generally, to be particularly conscious when using these apparently basic even banal words for wouldn’t we all agree, black is a word that means dark and white was a word that means light and that dark is understood to be under, feared like a basement or as a place to hide, like in a thick forest or a blanket, and light is received as a place of hope and exposure, levity and wisp.

...(more)

_______________________

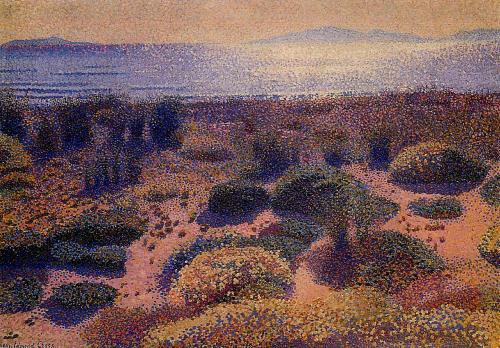

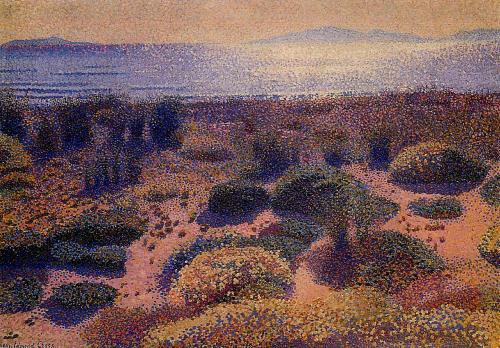

Plage De La Vignassa

Henri-Edmond Cross

1891-1892

_______________________

On the Creative Ecology of Words

Anand Pandian in dialogue withThomas Yarrow

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 22

acedemia.edu

(....)

One reflection on writing that I find myself returning to time and again is Walter Benjamin’s essay on the storyteller. What distinguishes the story as a narrative form, Benjamin writes here, is its interpretative amplitude – half the art of storytelling, he argues, is keeping the story free from explanation, leaving to the reader the responsibility for piecing together a sense of what is happening. Although we may owe our readers more than this in anthropology, there has always been a place for this kind of narrative and interpretative amplitude in the written work of the discipline. Think of what Bronislaw Malinowski published in this journal almost exactly a century ago, that long 1916 essay on the spirits of the dead written between two rounds of fieldwork in the Trobriand Islands. ‘In the field’, Malinowski notes, ‘one has to face a chaos of facts, some of which are so small that they seem insignificant; others loom so large that they are hard to encompass with one synthetic glance’. To be sure, the ultimate aim of the essay is to arrive at the ‘rules’ that would invest these facts with a systematic form. But this aim can hardly be said to govern the writing itself, its mode of expression, which wends its way through page after page of vivid reminiscences, asides, conjectures, and indulgences that draw the reader deep into the intricacies of an unfamiliar milieu with little sense, at least at first, of what precisely to do with these details. Indeed, as Malinowski himself observes, everything turns on what can be learned ‘bit by bit, through actual experience’.

Anthropology has always been a speculative enterprise, wagered on the chance to surpass some determinate picture of the human and its limits. This is something that happens between our stories and our arguments, between a space of evocation and the concrete possibilities for thinking otherwise that this space might sustain. With Reel world, and the ‘thickets’ to which you refer, what I tried to do was to allow each of the arguments made in the book to ‘grow’ from some empirical scene or circumstance, in the manner of expressing an immanent potential for an idea lodged within those scenes (expression, say, in the manner of a seed and stem, rather than as the reflection of a pre-given content). To proceed this way is to imply that description and argument are not mutually exclusive – instead, it’s a matter of relative weight or emphasis, a matter of modulating, in other words, that interpretative amplitude that Benjamin wrote about.

(....) ...(more)

_______________________

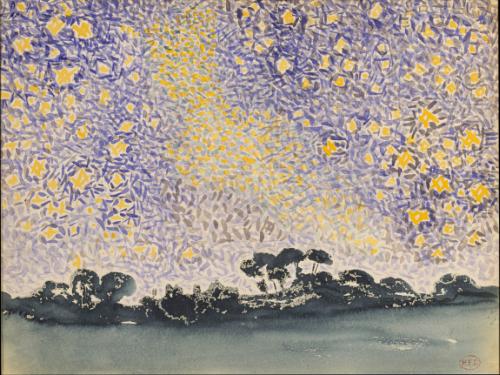

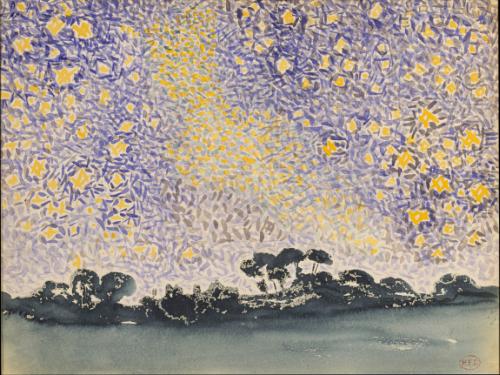

Landscape With Stars

Henri-Edmond Cross

b. May 20, 1856

_______________________

In Praise of the Long Sentence

Gerald Murnane

Meanjin

(....)

In 1986 I was invited, along with several other writers, to give a short talk at the Melbourne Writers Festival on the subject ‘Why I write what I write’. I was not surprised when the other writers talked about childhood experiences, subjects that inspired them, or concerns that drove them to write. I chose to talk about none of these, and my short speech must have impressed at least one member of the audience, the then editor of Meanjin, Judith Brett, who published the speech a few months later. My speech began ‘I write sentences. I write first one sentence, then another sentence. I write sentence after sentence…’ I made no mention of grammar in my speech. I spoke more about such matters as the shape of meaning, the sound of sense, the contour of thought. These were all expressions I had learned from other writers’ efforts to explain why some writing, to put it simply, is better than other writing. I quoted a remarkable passage by Virginia Woolf in which she claimed: ‘A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it … and then, as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it.’ I wrote my speech 30 years ago, and I’m as pleased with it today as I was then, but I acknowledge that my essay, so to call it, is no sort of compelling argument for grammatically sound sentences. Rather, it seems to suggest that I trusted for most of my life in a sort of instinct. I trusted in a sort of instinct and looked only for apt or suggestive forms of words, and yet I never needed to violate the principles of traditional grammar.

(....)

Several times during the writing of this piece, I may have seemed to be trying to justify my use of long sentences. Certainly, I left off writing this piece now and then and pondered on my liking for such sentences and my interest in punctuation and traditional grammar. These preferences of mine may have a simpler explanation than I sometimes try to find. During the first ten years of my life, I was closer in time to the nineteenth century than to the present century. For most of my childhood I read books written long before my birth, books by R.L. Stevenson, Charles Kingsley, Charles Reade, William Henry Hudson. Even our English textbooks at secondary school recommended the prose of Charles Lamb, Thomas Hardy, George Borrow. I long ago gave up reading contemporary writers, but I still look often into Hardy’s novels or Lavengro or The Romany Rye. Perhaps I learned the subtle rhythms of left-branching nineteenth-century prose in the same way that the authors of that prose learned the rhythms of their Cicero or their Livy. I would be far from disappointed to learn that this is so.

...(more)

via A La Recherche Du Temps Perdu

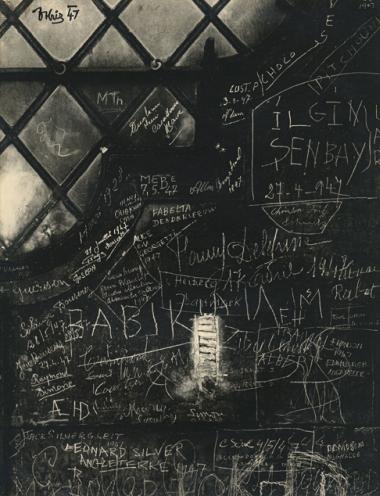

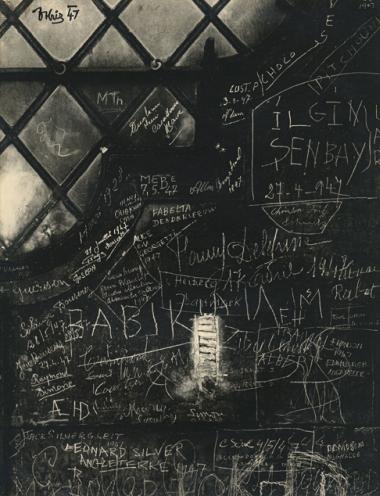

Writing on the Wall

Paris, 1947

Vilem Kriz

1921 - 1994 Vilem Kriz:Poet in Exile

Dean Brierly

_______________________

Insanity and Ecosophy from Guattari and Bateson to Malabou

and back to Spinoza [pdf]

Rick Dolpijn

(....)

Being in conversation with Antonio Damasio and interested in how the trauma in any

possible way affects the human individual, the conatus, with Malabou, mainly concerns the

brain or the nerve system we incorporate. For Spinoza (as for his contemporaries) however

the conatus is in no way limited to the human being. The conatus is necessarily at work in

every realized body and causes every realized body to think. In his famous letter to G.H.

Shaller dated October 1674 he ascribes the conatus to a stone, concluding that:

“[A] stone receives from the impulsion of an external cause, a certain quantity of motion, by

virtue of which it continues to move after the impulsion given by the external cause has

ceased. The permanence of the stone's motion is constrained, not necessary, because it must

be defined by the impulsion of an external cause…Such a stone, being conscious merely of its

own endeavour and not at all indifferent, would believe itself to be completely free, and would

think that it continued in motion solely because of its own wish. This is that human freedom,

which all boast that they possess, and which consists solely in the fact, that men are

conscious of their own desire, but are ignorant of the causes whereby that desire has been

determined. Thus an infant believes that it desires milk freely” (Spinoza 1955: 390).

Not only does the conatus, with Spinoza, show us how the mind is consequential to the body,

it also emphasizes that it’s desire to persevere in its being is necessarily at work in all of the

ideas that this produces. This is by all means a strong critique of how the ecological debates

are now evolving. It tells us that:

1. We cannot save the Earth. It is only because the human being, like the infant, like the

stone, like any material constellation, would believe itself to be completely free, which

is not the case at all, that dualist thought has been able to control and to destroy the

world we live in.

2. Since every individual is always a multiplicity of individuals, and since the conatus

accompanies every individual, we cannot but conclude that ecosystems think, that

they have an idea, that they are conscious of their deeds, and thus (very important)

can suffer from a tauma that consequently prevents the realization of their unity. (The

conatus then comes close to what Deleuze and Guattari called “the abstract

machine”.)

3. Emphasizing the ecosystem, our aim should be to start thinking insanity and

ecosophy is to think Lake Erie, or even worse, Fukushima. For when Malabou talks of

the coldness, the indifference, that happen with the trauma, isnt Fukushima then the

best possible example of how a form is injured, robbed of its plasticity, indifferent to

its own survival? Isnt Fukushima today showing us what it means to be actual but not

real?

The ecological crises that happens today, demands us to pay serious attention to how this

“sudden accomodation of the worst”, this trauma that continues to manifest itself, is at work

in all dimensionalities and directionalities of existence. For us human beings, ecosophy

demands us to open ourselves up to the coldness and indifference that has taken over some

of the ecosystems today, that has traumatized them, disturbed their presence, their ideas

with which we live.

(....) Terra Critica

...an international research network in the humanities, bringing together scholars specializing in critical and cultural theory. Its aim is to reexamine critical theory and critique under the conditions of the 21st century – given our immanent, terran existences, globally entangled across flows of capital, people, and ideas and living in ecological and economical multidependences.

_______________________

Massy, France

Vilem Kriz

1949

_______________________

Five Poems

Robert Fernandez

conjunctions

Those You Live Among

I have no camera

no game no tent, no word no mon-

strance no belt, no vent no succor,

no assuage no guilt, no music

*

The boarders they play games with you

those whose stomachs are full

of steaks they toy with you, the house

is full of toys

*

And each day, crime is easier, those

I live among, those I live among let me have my

speech, I can

not speak rocks in oil flounder

in oil and window pane almond al-

mond who is fragrant enough to live

among? Who is fair enough to be set beside?

*

My days are broken

and setting

and more truthful

*

The light despises me food

despises me the word despises me

I am no fate

I am no fate-in-his-robes

no styled light today I am bled

I see the rainbow’s metal blinds open

I am time, purple gold dripping out, sail-

fish fans fans fans monstrance monstrance

monstrance

I am no ointment here

I am no bruise-paste-of-day

...(more)

Robert Fernandez at the Poetry Foundation

_______________________

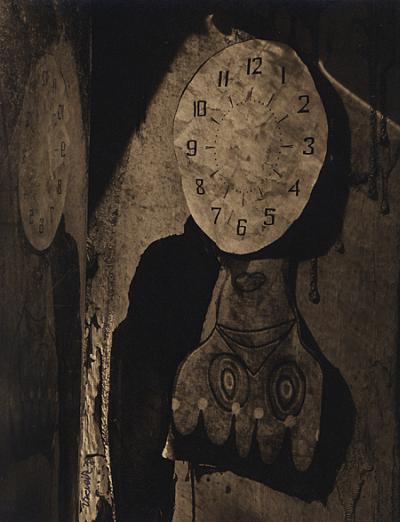

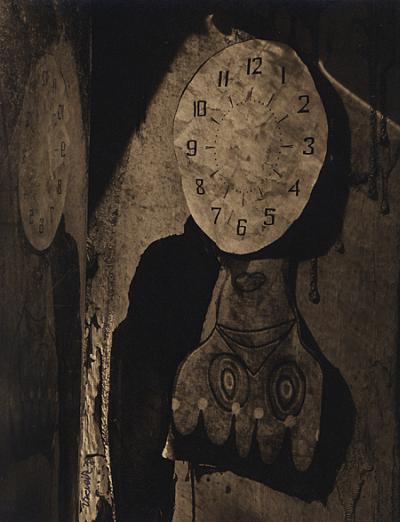

Untitled (time)

from seance, Berkeley

Vilem Kriz

_______________________

What the Dickens? On First Seeing Great Expectations in Mrs. Dalloway

Andre Gerard

berfois

When we want to decide a particular case, we can best help ourselves, not by reading criticism, but by realizing our own impression as acutely as possible and referring this to the judgments which we have gradually formulated in the past. There they hang in the wardrobe of our mind—the shapes of the books we have read, as we hung them up and put them away when we had done with them. If we have just read Clarissa Harlowe, for example, let us see how it shows up against the shape of Anna Karenina. At once the outlines of the two books are cut out against each other as a house with its chimneys bristling and its gables sloping is cut out against a harvest moon. At once Richardson’s qualities—his verbosity, his obliqueness—are contrasted with Tolstoi’s brevity and directness. And what is the reason of this difference in their approach? And how does our emotion at different crises of the two books compare? And what must we attribute to the eighteenth century, and what to Russia and the translator? But the questions which suggest themselves are innumerable. They ramify infinitely, and many of them are apparently irrelevant. Yet it is by asking them and pursuing the answers as far as we can go that we arrive at our standard of values, and decide in the end that the book we have just read is of this kind or of that, has merit in that degree or in this.

“How Should One Read a Book?”, Yale Review, October 1926

It is a truth too often accepted, that a modernist writer with Virginia Woolf’s feminist and elitist tendencies, had no use for Victorians in general and for Charles Dickens in particular. For instance, in Virginia Woolf and the Victorians (2007), Steve Ellis talks about “how Woolf’s own supposedly fundamental anti-Victorianism is sustained as a position by critics refusing to recognize key differences between her and ‘Bloomsbury.’”1 In “Two Londoners: Charles Dickens and Virginia Woolf” (a paper first presented at the Museum of London’s 2012 “The Global Meaning of Dickens and ‘Dickensian’ Today” conference), Francesca Orestano makes the even stronger claim that Dickens and Woolf “figure as incompatible entities in the literary canon, and therefore have never been associated.”2 Certainly, despite the profusion of Woolf scholarship, there do not seem to be any books or papers which closely examine Woolf’s engagement with Dickens. To counter the currently prevailing truth, my paper proposes that Dickens and Woolf were far from incompatible. Indeed, I would argue that Woolf was deeply influenced by Dickens, and intertextual readings of themes, plot, and characterization in Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse show deep and deliberate indebtedness to Dickens. Vivid traces of Bleak House are to be glimpsed in To the Lighthouse, and Mrs. Dalloway can even be read as a strong rewriting of Great Expectations. There is much to be learned by looking at how Woolf thought about Dickens, and at how she made use of Dickensian characters, plots and themes in her own writing. For all her modernism and her feminism, Woolf never abandoned or deserted Dickens.

...(more)

_______________________

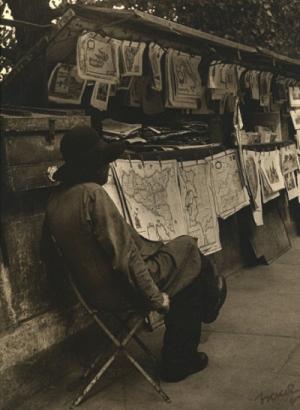

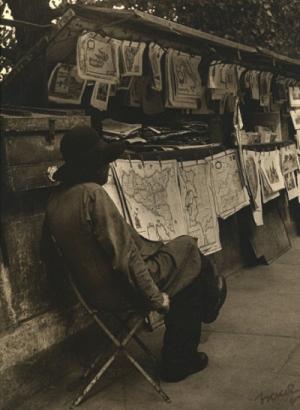

Map Merchant

Paris, 1949

Vilem Kriz, An American Surrealist

Scott Nichols Gallery

_______________________

Marginal Thinking: A Forum on Louis Althusser

Jason Barker, editor

los angeles review of books

Jason Barker

Dariush M. Doust

Nina Power

Richard Seymour

Greg Sharzer

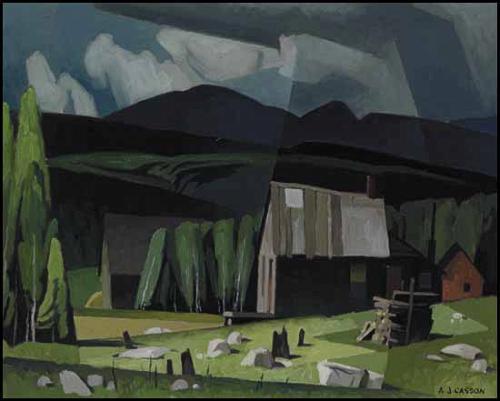

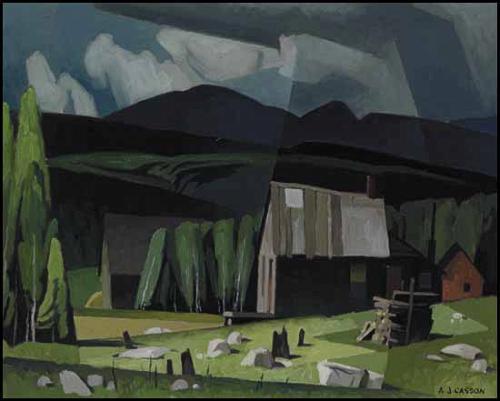

Settler's Cabin

c. 1955 - 1960

A. J. Casson

b. May 17, 1898

_______________________

Poems from Switching mirrors

Aksinia Mihaylova

parallel translation by Aneta Panteleeva

Searching

1.

We take out landscapes,

hidden in the darkest of our veins,

and we pile them on the table.

This is how people uncover themselves

meeting for the first and last time

because they are free of the future.

We smoke half a pouch of tobacco,

while digging in piles and counting

the bones that have sprouted in our souls,

but we cannot find the word,

that makes it come true.

The gorges in us echo

with different depths

and in a language unintelligible to the skin.

...(more)

Bulgarian Literature: PoetryDrunken Boat 23

_______________________

Plantanus occidentalis

Buttonwood

planted 1897

Experimental Farm

Ottawa

photo - mw

_______________________

the rhetoric and lethargy of the anthropocene

Ewa Binczyk interviewed by Richard Marshall

(....)

The main inspiration for my previous book, A Picture that Captivate Us. Contemporary Views of Language in the Face of Essentialism and the Problem of Reference (published in 2007), was a picture of a language in archaic, preliterate cultures. Analyzing the exoticism of such cultures, we head for the most remote regions of the human history and touch upon the problem of the beginnings of a symbolism itself. I framed in this book the speculative model of pre-referential cultures. I hope it facilitates resignation from the old habits of the traditional thinking about language (including essentialism, dualism between language and reality, and harmful overfocusing on the problem of referentiality). Interesting attempts were undertaken with a view to redefine the category of reference beyond the assumptions of essentialism. They are particularly prominent within the philosophy of Josef Mitterer, Stanley Fish, Latour, late Wittgenstein, John L. Austin, Willard V. O. Quine, Richard Rorty and Jacques Derrida.

The Wittgensteinian metaphor of picture that captivate us, which is the interpretive key to the arguments contained in my book, refers to a collection of futile philosophical assumptions, strongly criticized by the heroes of my narrative. Those assumptions prevented the development of more fruitful and more open views of language. While philosophizing about language we need to take into account a few factors, such as: 1) the existence of non-referential but meaningful expressions as well as the fact of the empirical underdetermination of reference, 2) the importance of performative dimension of language, 3) the role of practice of building and maintaining references in the area of situated speech (parole), 4) the existence of de-essentialised common area shared by the participants of acts of communication.

(....)

I am currently working on the book entitled: Rhetoric and Lethargy of the Anthropocene. A Fiasco of the Politics of Nature and the Irrationality of Late Capitalism. I can say that anti-essentialism and constructivism bind together my philosophical interests, and the notion of the Anthropocene is inherently constructivist. The idea of the Anthropocene embodies tensions and fears of our anti-essentialist age. In the Age of Man such notions as nature, climate, or weather are not neutral categories anymore.

In my opinion, a potential climate catastrophe is one of the most important political, philosophical, categorical and also existential challenges for the XXI century. Philosophy of science, focusing on its civilizational role can no longer avoid the problem of climate change. The current debates about the climate and the environment constantly redefine our understanding of nature as something worth protecting. It is a deeply normative and political concept now. At the same it has become very problematic. More and more people think that the climatic correction of late capitalism is unavoidable.

...(more)

_______________________

"Stillness after rain

A. J. Casson

Group of Seven

_______________________

On the Nature of Our Spirit

A Translation of "Über die Natur unsers Geistes" by Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz

by Douglas Robertson

A Layman's Sermon on the Text:

"I will pour out my spirit upon all flesh." (Joel 2:28)

(....)

... here most thinkers or philosophers are generally beset by a curious kind of self-deception. They believe they have carried their independence as far as it can go once they are capable of withdrawing their attention from the objects that immediately impinge upon them and redirecting it either to themselves or to other things of any old sort. They believe they have attained real worth if they manage to sedate their soul and lull it to sleep, instead of maintaining a counterweight to disagreeable external impressions by means of their own inner strength. The feeling of a void in their soul that consequently arises is sufficient punishment to them, and they always have their hands full just helping their ever-sagging pride back up from the ground. They feel that they cannot withdraw themselves from their disagreeable sensations without inducing a waste and a void in their soul, and this conflict-ridden condition is more harrowing than the disagreeable sensations themselves.

Thinking does not mean going completely numb; it means letting one’s disagreeable sensations rage with all their violence and feeling that one has enough strength to investigate the nature of these sensations and therefore to place oneself above and beyond them. To juxtapose these sensations with earlier ones and to weigh them against one another, to arrange them and survey them. Only then can one say that one feels—and once such a struggle has been weathered and survived, a human being, or that human being’s spirit, acquires a solidity that becomes for him or it the guarantor of the eternal duration and indestructibility of his or its existence. Hence, one is happy only upon attaining the conviction that one has oneself to thank for this happiness.

...(more)

_______________________

south of Kaladar

Sheffield Conservation Area

photo - mw

_______________________

Voyage

Charles Baudelaire

translated by Tony Brinkley

drunken boat

1

For a child in love with lithographs and

maps, his hunger and the universe are

equals. How vast his world appears at night

beneath a lamp—how small a memory!

We depart one morning—brains enflamed,

hearts coarse with spite and bitter wishes.

And we’re off, following wave-rhythms

cradling infinities, rocked by the sea’s

finitude. And some escape an infamous

country, some childhood horrors—and

are happy. Others, the stargazers, drown

in Circe’s tyrannies of lethal perfumes,

drink metamorphoses, not animal-becomings,

but sky-changes—changing space and light

and inflamed ceilings—cold mirror-gnawing

and sun-darkening—gently effacing every trace

of kisses. All voyages depart. Real travelers also

leave but only for the sake of leaving—hearts careless

as balloons but never swerving from their own

fatalities, not knowing, always chanting, “Come!”

“Join me!”—desire like the clouds, like nudes in

paintings—or a fresh recruit who dreams artillery—

dreams unknown variables—vast sensualities—

for which the human spirit has no name.

...(more)

Le Voyage

Charles Baudelaire

Fleurs du mal

Drunken Boat 22 - Translation

For this issue, Translation at Drunken Boat decided to indulge our love for experimentation and playing around the margins of what translation is and does. To that end, we sought out alternative, exploratory projects along the lines of translators' notes as translations; adaptations that move beyond genre- or time-shifting and into a kind of commentary on/conversation with the original; critical essays that play with translation to reflect on literature, poetics, and translation; and new translation manifestos.

We were lucky to receive a wide and sparkling range of responses to that call, eight of which we've selected to share with our readers.

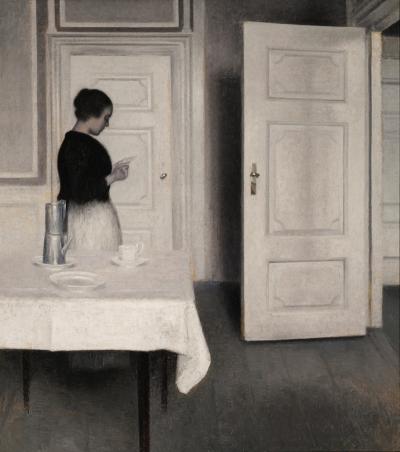

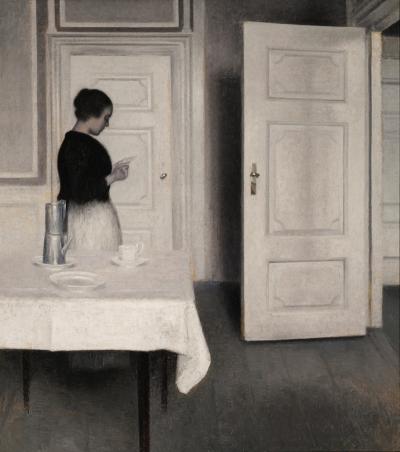

Vilhelm Hammershøi

1864 -1916

_______________________

Reading Proust on My Cellphone

Sarah Boxer

The Atlantic

... in the fall, shortly before my father turned 95, I began where I left off, in Sodom and Gomorrah, reading Proust on my cellphone at night when everyone else in the house had gone to sleep.

When I tell people this, they look at me like I have drowned a kitten. And when I tell them that not only did I finally finish all of Sodom and Gomorrah on my cellphone, but the rest of Proust’s opus, too, and in time to tell my father, they back away from me very slowly.

I do like books, real paper books. I have shelves full to prove it. But reading Proust on my cellphone was, I have to say, like no other reading experience I’ve had before or since. It was magical and—dare I say it?—Proustian in a very peculiar way.

(....)

... the smallness of your cellphone (my screen was about two by three inches) and the length of Proust’s sentences are not the shocking mismatch you might think. Your cellphone screen is like a tiny glass-bottomed boat moving slowly over a vast and glowing ocean of words in the night. There is no shore. There is nothing beyond the words in front of you. It’s a voyage for one in the nighttime. Pure romance.

...(more)

_______________________

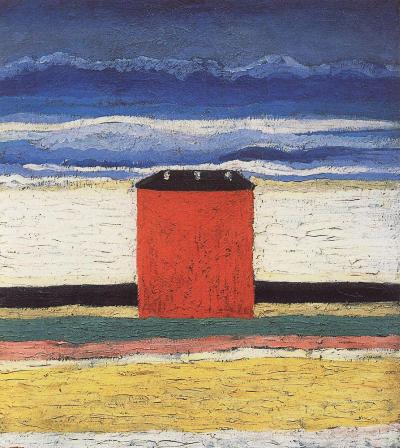

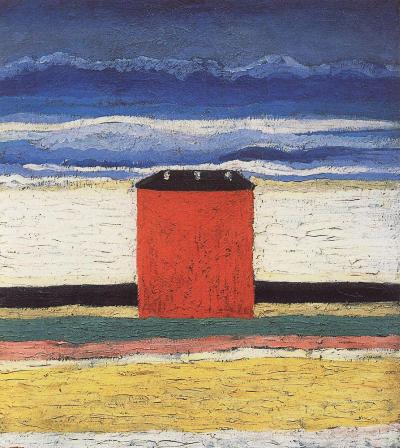

Red House

1932

Kazimir Malevich

1878 -1935

_______________________

from The Male Sentimental

Liz Kinnamon

courtesy of flowerville

(....)

Ultimately I am suggesting that a better way of thinking about patriarchy is as emotional manipulation. Characterizing it as misogyny, or “hatred of women,” increasingly misses the mark because it fails at descriptive precision. Hatred seems vague, outlandish, or unrelatable and this makes the accusation easy to dismiss. With the rise of feminism’s influence, patriarchy has sought different techniques, echoing Foucault’s belief that politics use a “sort of silent war to reinscribe that relationship of force.” The Male Sentimental can ultimately be seen as the result of a bargain with feminism: one can be a man with feelings, pass the feminist test, and still keep power. Patriarchy operates at the register of emotion where it can’t afford to operate through violence or coercion. In this light it also becomes quickly apparent that the appeal of the sensitive male subject is subtended by his potential for violence. As Eve Sedgwick’s therapist once described her father, “someone who could punish but doesn’t, or whom you can relate to so that he won’t.”

...(more)

_______________________

Ida Reading a Letter

Vilhelm Hammershøi

1899

_______________________

the beating heart: an argument for email

Tomoé Hill

3am

(....)

Our technology-driven world frowns upon lingering. Users—or people, as we used to be called—are not encouraged to spend time in the actual process of communication. Process is a means to an end; it does not equal pleasure. Every device and app we use makes this clear. Somehow we have found our lives increasingly automated for efficiency, yet we feel more and more like it is streamlining us right to death. Slow is bad, fast is good, faster is more productive. Hitting send once isn’t enough. Hit send repeatedly, now you’re getting things done. But like the impossible requests asked of Milo by the demon of petty tasks in the children’s story The Phantom Tollbooth, there is always one more send button to hit, one more thing to post. Our data has become increasingly valuable in the information economy; therefore, technology companies need us to share as much of ourselves as we can. When our interactions are driven by the needs of technology providers, rather than users, personal communication inevitably suffers.

Once we spoke, now we text. Tweets are 140 characters; DMs are a deferral of real communication; Facebook feels like messages tacked on a notice board. For the most part, these new platforms are designed for fast interactions—placeholders for a real conversation that you will most likely never have—or at least, while not impossible, finding the people who are truly kindred spirits becomes a less organic occurrence and more one akin to algorithm. Of course when we do, any negativity or cynicism dissolves in the face of this pleasure—the Saussurean ‘treasure’ of speech that can be extended to the online community and its keystroke interactions—but it does not quite erase the fact that the cacophony of chatter makes this a harder one to unearth.

(....)

Email reminds me of the days when I would write long missives on coloured notepaper, place stamps on the matching envelopes and post them off to Canada or England or wherever the love in my life lived at that moment. In this it is a kind of dance; there have been several romantic relationships in my life that were ‘virtual’ loves before they ever materialised in front me at an airport or a train station. It was the ceaseless exchange of words that made us fall in love, that immediate plunging into the depths of the other’s heart. As Barthes says about the love letter in A Lover’s Discourse, “for the lover the letter has no tactical value: it is purely expressive—at most, flattering (but here flattery is not a matter of self-interest, merely the language of devotion); what I engage in with the other is a relation, not a correspondence: the relation brings together two images.” Having what is in effect a blind conversation requires a larger degree of trust than if you initially met someone in person. After all, a letter is an invitation to discover, whether it is intentional or not. The absence of physical presence takes away a certain distraction. We focus on the words in front of us, and we read meaning not just in the words, but in the space between.

The romantic appeal of the letter still clings to the email like a ghost; not just in terms of love, but also as a pure exchange of thought. There is an assumption of directness that has remained in spite of its technological transformation. From this pen, these fingers, the contents of my mind emerge directly. This is an echo of Vilém Flusser in Gestures: “Thinking expresses itself in a whole range of gestures. But writing, with its unique straight linearity and inherent dialectic between the words of a whispered language and the message to be expressed, has a special place among the gestures of thinking.” Here there is something of another paradox: the logical application of writing one’s thoughts when the entire process is wrapped in some sort of dream-state. This is even more relevant when the two correspondents have never met. Does the real appear unreal, and if so, how does one become real through letters alone? At the best of times, we have a natural tendency to project aspects of ourselves onto others. Are correspondents a kind of automata, built and brought to life by words, a personality shaped with each new email? A fitting comparison; logic and fantasy brought together to create a complete being.

...(more)

_______________________

City Walls

1921/22

Niles Spencer

1893-1952

_______________________

Lydia Davis and Translationese

Multilingual Wordsmiths, Part 1

Liesl Schillinger interviews Lydia Davis

Los Angeles Review of Books

(....)

I love the English language. I know some people go into translating because they love foreign languages, but I love English above all, and I enjoy translating these foreign texts into my beloved English. I enjoy that aspect of translation — that it is a form of writing that doesn’t involve the invention of the piece of writing. I also love the puzzle aspect of it. I’m a fan of puzzles—sometimes crosswords, jumbles, cryptograms, but especially number puzzles, because they don’t involve words. Translation is both a form of writing and a puzzle to be solved: here’s a sentence; translate it into English. Constraints can be very helpful.

...(more)

_______________________

Station Without A Stop.

Kunzevo.

Kazimir Malevich

1913

_______________________

Kulterer

A Tale

Thomas Bernhard

translated by Douglas Robertson

The Philosophical Worldview Artist

(....) Out of boredom, and because otherwise he would inevitably have succumbed to despair, he would often read aloud to himself tales and stories of his own invention and composition—“The Cat,” for example, or “The Dry Dock,” or “The Swimming-Birds,” or “The Landlady of the Inn’s Manageress,” “The Death Bed.” The ideas for these stories came to him mostly at night, and in order not lose them he had to get out of bed in the dark and, while his cellmates were sleeping, to sit down at the table, and, in the midst of that “dreadful darkness,” to jot down what had just occurred to him. Moreover it seemed to him that for the time being he would be unable to write down an entire story all the way to the end without rather lengthy preparation beforehand, and this pleased him, because his stories did not admit of being interrupted by any kind of incident; he had once had to break off in the middle of a story because one of the three inmates with whom he lived in the cell had taken notice of him and brutally hissed him away from the table, and the story had been lost. But over time he had developed a method of getting up from his pallet and sitting down at the table so soundlessly that they did not perceive him even when they were hardly fast asleep. There was hardly ever a night, and in the past year-and-a half pretty much not a single further night, in which he had not been awoken by an idea or at least by a thought, by a hint of a thought. He called his writing “my pastime,” and it came to him the way dreams come to other people, and it was for him as fragile as a dream. ...(more)

|