|

Paul Nash

b. May 11, 1889

_______________________

Very Little....Almost Nothing

Death, Philosophy, Literature

Simon Critchley

google books

pdf

Lecture 1

Il y a

Just as the man who is hanging himself, after kicking away the stool on which he stood, the final shore, rather than feeling the leap which he is making into the void feels only the rope which holds him, held to the end, held more than ever, bound as he had never been before to the existence he would like to leave. (Thomas the Obscure, revised version)

Reading Blanchot is, in a sense, the easiest of tasks. His French is limpid and clear, it is daylight itself; almost the French of the Discours de la méthode. And yet, as nearly everyone who writes on Blanchot points out, his work seems to defy any possible approach, it seems to evade being drawn into the circle of interpretation. The utter clarity of Blanchot’s prose would appear to be somehow premised upon a refusal of the moment of comprehension and the consequent labour of interpretation and judgement. Absolutely clear at the level of reading, yet fundamentally opaque at the level of comprehension; a vague fore-understanding that somehow resists being drawn up into an active comprehension.

Reading Blanchot, and this will be my only hypothesis in what follows, one is drawn from daylight into an experience of the night. An experience of the night which is not the sleep which blots out and masters the night, preparing the body for the next day’s activity – the sleep of Dasein, of heroes and warriors, that allows the night to disappear and transforms it into a reserve of possibility. The latter is what Blanchot calls the first night, the night in which one can go unto death, a death one dies each time sleep comes – sleep as mastery, as virility unto death.

Reading Blanchot one is led rather into an experience of the other or essential night, the night which does not permit the evasion of sleep, the night in which one cannot find a position, where the body refuses to lie still – this is the spectral night of dreams, of phantoms, of ghosts. In the other night, one can neither go to sleep nor unto death, for there is something stronger than death, namely the simple facticity of being riveted to existence without an exit, what Blanchot calls le mourir in opposition to la mort: the impossibility of death (ED 81). In the other night, one is not permitted the fantasy of suicide, that controlled and virile leap into the void that believes the moment of death is a possibility that can be mastered; a perverse version of the belief that one can die content, in one’s bed, with one’s boots on. In place of the mastered leap into the void, all the suicide feels is the rope tightening around his neck, binding him ever tighter to the existence he wanted to leave. This condition of being riveted to existence is also the experience of insomnia, a reluctant vigilance in the night, the night that slowly exhausts and sickens the body, thereby preventing sleep the following night and thus engaging insomnia’s vicious circle. This is the bodily recollection of the night that one carries around during the day like a thousand invisible aching scars – eyes quietly burning beneath closed lids. Blanchot’s original insight, obsessively reiterated in his work, is that the desire that governs writing has for its (impossible) origin this experience of the night, which is the experience of a dying stronger than death, what Levinas will call, and I will keep coming back to this, the il y a.(....)

_______________________

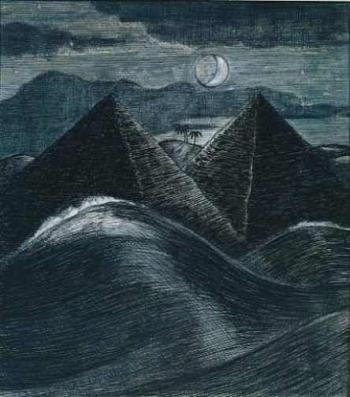

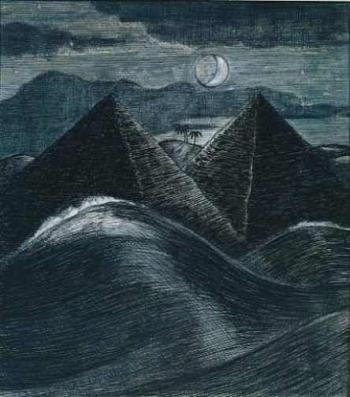

The Pyramids in the Sea

Paul Nash

1912

_______________________

From Second-Hand Time

Svetlana Alexievich

Translated by Bela Shayevich

(....)

Communism had an insane plan: to remake the ‘old breed of man’, ancient Adam. And it really worked … Perhaps it was communism’s only achievement. Seventy-plus years in the Marxist-Leninist laboratory gave rise to a new man: Homo sovieticus. Some see him as a tragic figure, others call him a sovok. I feel like I know this person; we’re very familiar, we’ve lived side by side for a long time. I am this person. And so are my acquaintances, my closest friends, my parents. For a number of years, I travelled throughout the former Soviet Union – Homo sovieticus isn’t just Russian, he’s Belorussian, Turkmen, Ukrainian, Kazakh. Although we now all live in separate countries and speak different languages, you couldn’t mistake us for anyone else. We’re easy to spot! People who have come out of socialism are both like and unlike the rest of humanity – we have our own lexicon, our own conceptions of good and evil, our heroes and martyrs. We have a special relationship with death. The stories people tell me are full of jarring terms: ‘shoot’, ‘execute’, ‘liquidate’, ‘eliminate’, or typically Soviet varieties of disappearance such as ‘arrest’, ‘ten years without the right of correspondence’, and ‘emigration’. How much can we value human life when we know that not long ago, people died by the millions? We’re full of hatred and superstitions. All of us come from the land of the Gulag and harrowing war. Collectivization, dekulakization, mass deportations of various nationalities…

(....) ...(more)

_______________________

Paul Nash

_______________________

The Aesthetic Politics of Affect

Todd Cronan reviews The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigwort

NONSITE

republished from Radical Philosophy March/April 2012

(....)

(Lauren) Berlant’s analysis focuses on the moment in the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts in which Marx describes the “abolition of private property” as signaling the “emancipation of all human senses”. No longer seeing objects as fetishes and nature as a matter of use, the senses, Marx says, become “theoreticians”. Berlant draws on this passage in Marx to understand John Ashbery’s untitled send-up of the American Dream. According to Berlant, “our senses are not yet theoreticians because they are bound up by the rule, the map, the inherited fantasy, and the hum of worker bees who fertilize materially the life we are moving through”. The problem, for Berlant, is the suburban fantasy “of the endless weekend,” the “consumer’s happy circulation in familiarity,” and the “privilege of being bored with life”. (Gregg’s essay similarly takes up the regressive “politics of the cubicle”.) As a reading of Ashbery this might be right, but as an account of Marx, it isn’t. For Marx, of course, the problem is the privilege of private property, not the “privilege of being bored.” One could safely eradicate boredom, without it bearing on the problem of capital. The anxious worker, after all, lacks (and perhaps looks forward to) the privilege of being bored. And affects, despite their “sensorium-shaking” transformation of the “bourgeois senses”, begin to look a lot like the fetishized private property Marx scrutinized. Affects are, Berlant insists, “radically private, and pretty uncoded”, and like the fetishized commodity, they make their dazzling appearance with the labor behind them obscured. These private experiences are in fact beyond analysis—an affect, after all, “is just a fact”....(more)

_______________________

A Translation of Ungenach

Thomas Bernhard

Translation by Douglas Robertson

(....)

walking and thinking, this simultaneity,” said Moro, “I observed in your esteemed father as well as in your esteemed guardian, as well as in my father throughout his life. I myself do not take walks. On account of this more than anything else I aroused the distrust of your father, as well as the distrust of your esteemed guardian…the walk-takers distrust people who do not take walks, who are not walk-takers, the anachronisms and so forth…and so this lovely landscape, this landscape of ours, is permeated in the most remarkable fashion by an unrelenting, in truth an omni-obfuscating distrust, a delicate tissue of distrust of non-walk takers by walk-takers permeates this landscape.”

“Thus friendships between walk-takers and non-walk takers are unthinkable…as is friendship in general,” said Moro. ...

(....) One wakes up and awakens into vulgarity and into baseness and into dullness and into weakness of character and starts thinking and thinks in nothing but vulgarity, baseness, dullness, weakness of character. In nothing but the pathology of death and existential dilettantism. One hears and sees and thinks and ages, each according to one’s innate fashion[,] in loneliness, incapableness, shamelessness.

The notion that life is a dialogue is a lie, and the same goes for the notion of life as reality. Although not fantastical, it is nevertheless a misfortune qua infamy, a period of horror that, [regardless of its brevity or longevity / sooner or later], is composed of melancholy and the begetting of discontent…merely in the billions of walking causes of death, effects of death…we are dealing here with a colossal intolerance of creation that renders us ever-more depressed and bitter and ultimately kills us. We think we have lived and in reality we have died. We think that the whole thing has been an apprenticeship, and yet it has never been anything but sheer drivel. We look and we ponder and are obliged to keep looking all the while that that at which we are looking and that which we are pondering eludes us, and the world, which we have undertaken to master or at least to change, eludes us, and the past and the future elude us, and we elude ourselves, and in the end everything becomes impossible for us. We all exist in a state of mental catastrophe. We are constitutionally predisposed to anarchy. [With] everything [with]in us standing permanently under suspicion. Where there is feeble-mindedness, where there is no feeble-mindedness, there is insufferableness. At bottom the world, from out of which we also gaze at it, is made out of insufferableness. The world is always insufferable by us. Our endurance of this insufferableness is the lifelong capacity for sorrow and anguish [possessed by] every single one of us, a pair of ironically [twinned] elements within each of us, an irrational idiom of idiocy; all the rest is slander.”

...(more)

_______________________

Paul Nash

Splashed Colour Landscape of

Beautiful Mountain Qingcheng

1973

Zhang Daqian

b. May 10, 1899

_______________________

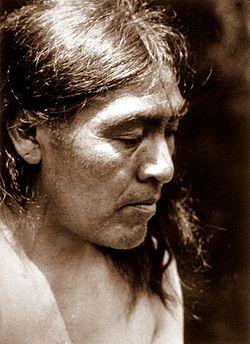

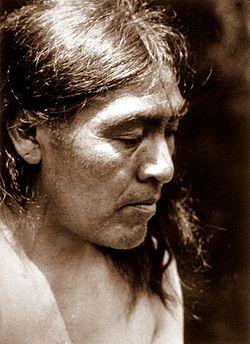

For The Hundredth Year Anniversary Of Ishi’s Death

Scott Ezell

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

Die into what the earth requires of you.

—Wendell Berry

1.

square tongues speak brick words

that couple into nothing,

surrounded by hair and flowers.

decay of fruit and love and sex,

all subside

into chemical contemplation,

alcohol and buzzing bees,

sweet sticky scents.

police machines chop the sky

into thistles of noise and fear—

I pick up and carry a river on my back,

a cloak of home

to drape across

the shoulders of the world,

enfolding streams and stones.

glaze of bone

across my eyes,

a hood of silence,

my tongue of salt

dissolving into words

I speak to you.

...(more)

Songs from a Yahi Bow: A series of poems about IshiEdited by Scott Ezell

with poems by Yusef Konumyakaa,• Mike O’Connor • Scott Ezell, and an essay by Thomas Merton • poems and prose

Ishi

(c. 1861 – March 25, 1916)

_______________________

Six Proposals for the Reform of Literature in the Age of Climate Change

Nick Admussen

(....)

2. Retire the portrait of the single soul

Most stories specifically identify individuals who profit from narratives of progress, whether intellectually or materially. In Joyce’s epiphany model, the reader sees some moral profit. In the standard adventure story, it’s both the reader, who is entertained, and the hero—Phileas Fogg makes it around the world in eighty days, Katniss has a family with Peeta, James Bond gets the bad guys. The triumphal feeling of these stories comes from their selective attention to just a tiny part of the network of relationships that enfolds their characters.

In the stories we need, though, nobody exists outside of some reference to social and physical contexts. Life touches at life from all points on the globe at all times.

Individualism is an intervention we make into our environment. It is a destructive and atomizing act of imagination. It erases our radical dependence on each other and on the environment. We know the intellectual and moral thinness of this trope (just try to watch the 1992 “iconoclastic-cowboy-in-the-rainforest” film Medicine Man) yet we remain endlessly fascinated by its variations in media, from the popular to the avant-garde.

This is the original sin handed down from Thoreau’s Walden: pretending no one else exists, unmaking the blacksmith that sold Thoreau $3.90 worth of nails, the man who carried his luggage to his pond-side cabin, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, who housed and fed Thoreau while he edited the manuscript. Readers experience a book as one person speaking to another, almost epistolary, missing the way in which a book is a collaboration of many hands. Romantic ideas of the artist slaving away at a desk alone in the middle of the night prevent us from seeing the way in which all artwork is the product of many minds thinking together.

Reducing literature to a procession of isolated actors (or authors) belies the responsibility readers have to see the disastrous paradigm in which a focus on individuals occludes acts that harm the broader community.

...(more)

The Critical Flame_______________________

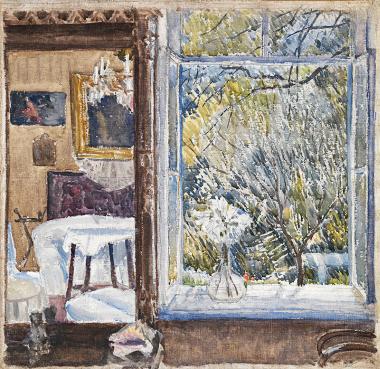

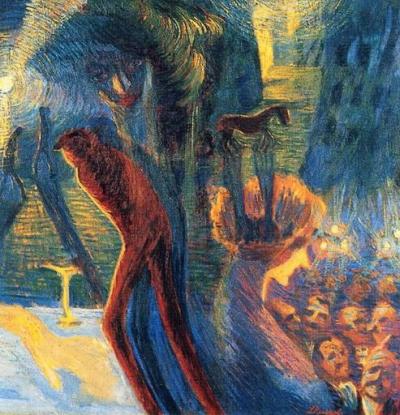

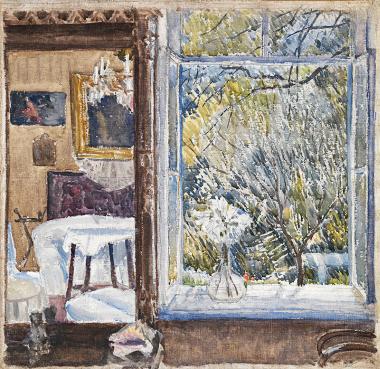

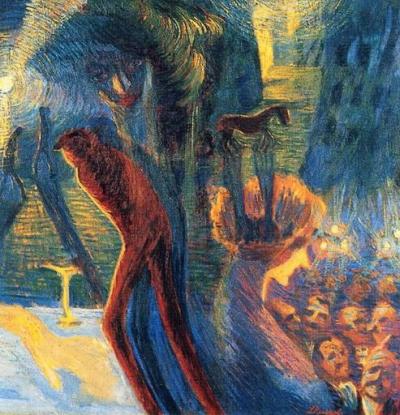

Une journée de mai

Mikhail Larionov

d. May 10, 1964

_______________________

Sometimes You Need a Record of Your Life: on Lisa Robertson

Zachariah Wells

Critical Flame

(....)

“Can the poem,” Robertson asks rhetorically, “become the space of that solitude? In this instance I took 9 years to build a pronoun. During that time I didn’t talk about it, and that was a freedom and a pleasure.” The solitary struggle “towards a pronoun caked in doubt” has culminated in the “complex structure” of Cinema of the Present, her most extended essay at the autobiographical poem of distributed subjectivity—and its pronoun is “you”:

What is the condition of a problem if you are the problem?

You move into the distributive texture of an experimental protocol.

A bunch of uncanniness emerges.

At 20 hertz it becomes touch.

A concomitant gate.

At the middle of your life on a Sunday.

A dove, a crowned warbler in redwood, an alarm, it stops.

You set out from consciousness carrying only a small valise.

(....)

The polyvalent character of the second person pronoun, however, is precisely what makes it the mot juste for a hundred-page extension of Robertson’s earlier ventures. The “you” is the very embodiment of “distributed subjectivity”: it can be singular, it can be plural, it can be the reader, it can be the poet, it can be anyone and everyone. One of Robertson’s favorite concepts is “utopia.” It crops up again and again in her books, from XEclogue (1993) to the present; it is the title of her most explicitly autobiographical poem and would constitute one of the chunkiest entries in her concordance. Utopia—literally “no place,” or, punned as “eutopia,” the best place—while inherited from Sir Thomas More, has connotations peculiar to Robertson’s idiolect. She articulates some of the parameters of the concept in her essay “Perspectors/Melancholy”:

Melancholy is big contemplative utopia. It is a system that functions to pose a seemingly boundless cognitive space where transformation, never a neutral event, always a grievance or an astonishment, can claim potential. Transformation may include decay, multiplication, reversal, inflation or minification, fragmentation or annexation, plus all the Ovidian modalities. But it is not possible to calculate which, or in what sequence. […] Melancholy is a latent or paused anticipation of something necessarily unknowable, where the latency is not passive, but an experimental site for non-identity. ...(more)

_______________________

Swiss Mountains

Zhang Daqian

1965

_______________________

Symposium on Pragmatism in Contemporary Political Theory

Guest editors: Michael Bacon and Clayton Chin

Political Studies Review

February 2016; 14 (1)

.....................................................

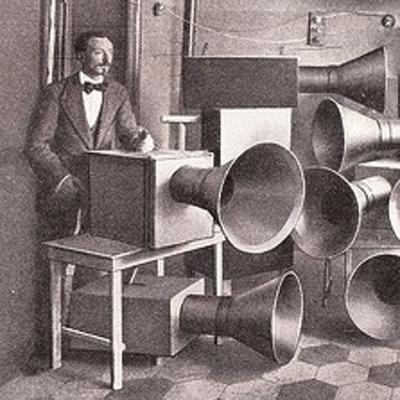

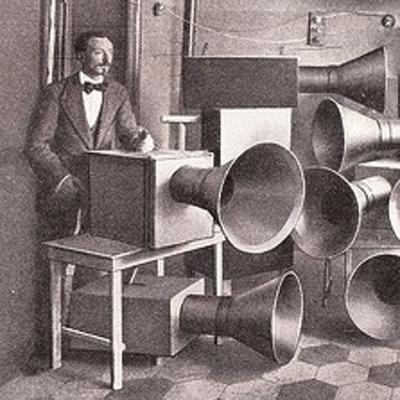

The Collected Recordings of Luigi Russolo’s (1885-1947) Intonarumori Noise Machines

_______________________

The Art of Noise [pdf]

futurist manifesto, 1913

Luigi Russolo

translated by Robert Filliou

(....)

First of all, musical art looked for the soft and limpid purity of sound. Then it amalgamated different sounds, intent upon caressing the ear with suave harmonies. Nowadays musical art aims at the shrilliest, strangest and most dissonant amalgams of sound. Thus we are approaching noise-sound. This revolution of music is paralleled by the increasing proliferation of machinery sharing in human labor. In the pounding atmosphere of great cities as well as in the formerly silent countryside, machines create today such a large number of varied noises that pure sound, with its littleness and its monotony, now fails to arouse any emotion.

To excite our sensibility, music has developed into a search for a more complex polyphony and a greater variety of instrumental tones and coloring. It has tried to obtain the most complex succession of dissonant chords, thus preparing the ground for Musical Noise.

This evolution toward noise-sound is only possible today. The ear of an eighteenth century man never could have withstood the discordant intensity of some of the chords produced by our orchestras (whose performers are three times as numerous); on the other hand our ears rejoice in it, for they are attuned to modern life, rich in all sorts of noises. But our ears far from being satisfied, keep asking for bigger acoustic sensations. However, musical sound is too restricted in the variety and the quality of its tones. The most complicated orchestra can be reduced to four or five categories of instruments with different sound tones: rubbed string instruments, pinched string instruments, metallic wind instruments, wooden wind instruments, and percussion instruments. Music marks time in this small circle and vainly tries to create a new variety of tones. We must break at all cost from this restrictive circle of pure sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.

(....)

_______________________

The Silence of the Lens

David Claerbout

Photography is currently undergoing the sort of transformation that music went through roughly fifteen years ago. This transition was a major shift for musicians but was generally considered positive by the listeners. For those young photographers keen on knowing how their profession will evolve, I would suggest they look at the music industry of today, fifteen years later, to get a glimpse of the changes to come.

In the short term, these changes may seem merely technical: simply a strange melting together of image-making and image-seeing, of production and perception. It will be sometime before this process will be complete, if it ever is. Then there will be a disappearance of photography as we know it. Instead of choosing how we want to see the world, we will see the world the way it wants to be seen by us. There will be a perfect equivalence between our gaze onto the world and the signals emanating from it, with no gap between the two where we might locate definitively the specificity of our own contribution. The emancipatory, modern, human point of view—which includes lovers of contingency and the mythical magic of photography—will hate this terminus, because it so resembles what we understand to be utter and total madness. The problem, as we will see, is that it is in the nature of the phenomenon that the subject cannot possibly know when this moment has arrived.

(....)

We are no longer in a world of contingency, of possibilities created by the collaboration of lens and world—that magical environment—but have become makers of everything down to the smallest detail. We are playing God, and by god, not even God had time to think of all these elements. No. God is a shortcut here: an assumption that further betrays the ideals of which we are unaware but according to which we nonetheless think and observe. This total fabrication implies that we are “observing from memory” and brings with it a sense of nostalgia and a feeling of loss, of having given up on a naive perception that supposedly happened spontaneously, without thinking. Such perception is remembered as being happy, because it was Unbewusst, unconscious—remember that consciousness, Bewusstsein, is unhappy—unencumbered by observing one’s own thinking, as Flusser reminds us in his simple but beautiful elaborations on representation (Vorstellung) and consciousness (Bewusstsein).

(....)

When images internal to the psyche “appear” or surface on the retina and are projected back inwards before making contact with the world, they generate looping pulses that turn the mind into a continuously repeating mental prison.

This happens, for example, when the affective link with the world is broken, or heartbroken, and in order to handle the grief one has to enter into the isolation I am trying to describe. We may think of this as a terrible thing to happen—and it is—but it also describes a larger social project collectively taking shape. My friend’s photograph of the sunset is a document of madness not because it is a delusion, but because it suggests that she had a role in producing it, and this is the delusion. Unlike Baudrillard’s schizophrenic, who cannot locate the borders of the self in the world of mass media, the world of pure ideologies perpetually projects borders onto the self that in fact do not exist, deluding us into thinking we produce some particular view on the world, when we do not. The lens was a machine for producing not only images, but authors and worlds as well. But now it has fallen silent. In the past, one had to believe that one was really a long-dead king or an alien from outer space to suffer from delusions of grandeur. Tomorrow it will be enough to consider oneself a photographer.

...(more)

e-flux journal issue 73

with Giorgio Agamben, Claire Fontaine, Vivian Ziherl, Rebekah Sheldon, David Claerbout, Franco “Bifo” Berardi with Marco Magagnoli, Stefan Heidenreich, and Maria Iñigo Clavo

_______________________

Memories of a Night

1911

Luigi Russolo

1885-1947

_______________________

Crazy Magdalena

A Translation of "Die Verrückte Magdalena," a Short Story by Thomas Bernhard

Translation by Douglas Robertson

(....)

“She was about 25 years old,” he resumed, “when I saw her in Paris. The postman’s little daughter, the crazy creature with the old-fashioned underclothes and the passion for donation, had been transformed into a dancer, a beautiful woman who rode along the Champs-Élysées to the theater every evening in a freshly waxed limousine. She danced to variations by Brahms and Debussy. I was nonplussed by the thought that a girl who was acquainted with nothing in the world apart from the old lady who ran the general store and the cross-eyed village school teacher, who indeed knew nothing at all about that world, nothing about the world of hatred, of calculation, of madness, of sentimental blather, of the world of irrationality, of war, of obloquy, of avarice, could be transformed…into a woman who ranged between red plush armchairs and the no less flattering than dubious odors of A Thousand and One Nights as though she had grown up immersed in an azure haze and the rustle of silk. I had a brief interview with her. Her comportment was off-putting and weird. She had turned into an obnoxious module of the urban cosmopolitan scene. Her eyes were filled partly with hunger and thirst for the hanging gardens of the modern Semiramis, partly with conflict, sorrow, and despair. Her eyelashes fluttered and after ten minutes of sitting face-to-face with her, of drawing closer to her as she drew closer to me, of feeling her out, I descried in her a doll conversing with the tips of its long white fingers, incessantly twitching its ears as though involved in a mechanical system….”

“And how was she as an artist?” I asked.

...(more)

_______________________

Duncan Grant

1885 -1978

_______________________

Drone Metaphysics

Benjamin Noys

(....)

The analysis of drone discourse has consistently registered the theological and metaphysical ‘supplement’ that surrounds the drone. I will argue – in line with Derrida’s analysis of the constitutive equivocation of the notion of supplement, which is both unnecessary extra addition and necessary element of completion – that this ‘supplement’ is not simply a mistaken appendage that could be removed to ‘really’ see the drone, but part of what we must critically analyse to grasp the drone. The risk of engaging with this theological or metaphysical resonance seriously is that we feed the technological fetishism that can impinge on the thinking of drones. To treat drones as if they were the ‘travelling eye of God’ is to flatter this mundane and brutal surveillance and killing device. We may give a technological object, or technological assemblage, a philosophical dignity it does not deserve.

This is the danger of techno-fetishism, which is not quite what Marx meant by fetishism, in his account of the fetishism of the commodity, or what Freud meant by fetishism, as a diagnostic category of sexual perversion, but something which mixes both. It involves the mysticism of material object being treated as possessed of divine powers, and the sexualisation of that power as a peculiar displaced potency. The result is the inflation of the technological object to something that horrifies and fascinates, electing it out of history into a natural or metaphysical realm.

This risk may be particularly acute when one approaches the drone as a philosopher or theorist. The absence of technical, sociological or other expert analysis can lead to the reification of the drone into a metaphysical dignity it does not warrant. It is, however, possible to interrogate the metaphysical stakes at work in this techno-fetishism, which cuts across both drone advocates and drone critics, without succumbing to it. It is only by taking seriously this fetishism that we can sharpen our critical discourse, the better to resist the seductions of drones.

(....) Drone CultureCulture Machine Vol 16 (2015)

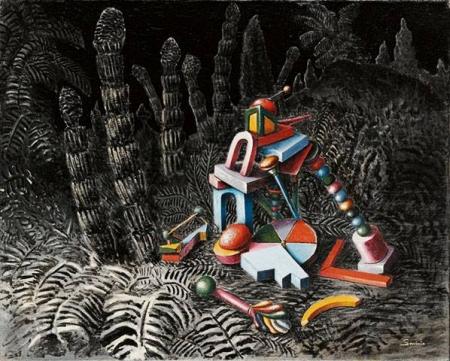

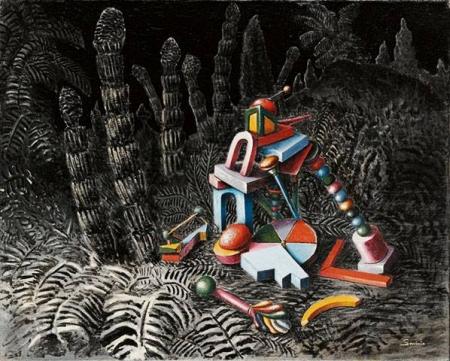

Le navire perdu

1928

Alberto Savinio

d. May 5, 1952

_______________________

The Lost World

Randall Jarrell

Born: May 6, 1914

I. Children's Arms

On my way home I pass a cameraman

On a platform on the bumper of a car

Inside which, rolling and plunging, a comedian

Is working; on one white lot I see a star

Stumble to her igloo through the howling gale

Of the wind machines. On Melrose a dinosaur

And pterodactyl, with their immense pale

Papier-mâché smiles, look over the fence

Of The Lost World.

Whispering to myself the tale

These shout—done with my schoolwork, I commence

My real life: my arsenal, my workshop

Opens, and in impotent omnipotence

I put on the helmet and the breastplate Pop

Cut out and soldered for me. Here is the shield

I sawed from beaver board and painted; here on top

The bow that only Odysseus can wield

And eleven vermilion-ringed, goose-feathered arrows.

(The twelfth was broken on the battlefield

When, searching among snap beans and potatoes,

I stepped on it.) Some dry weeds, a dead cane

Are my spears. The knife on the bureau's

My throwing-knife; the small unpainted biplane

Without wheels—that so often, helped by human hands,

Has taken off from, landed on, the counterpane—

Is my Spad.

O dead list, that misunderstands

And laughs at and lies about the new live wild

Loves it lists! that sets upright, in the sands

Of age in which nothing grows, where all our friends are old,

A few dried leaves marked THIS IS THE GREENWOOD—

O arms that arm, for a child's wars, the child!

And yet they are good, if anything is good,

Against his enemies . . . Across the seas

At the bottom of the world, where Childhood

Sits on its desert island with Achilles

And Pitamakan, the White Blackfoot:

In the black auditorium, my heart at ease,

I watch the furred castaways (the seniors put

A play on every spring) tame their wild beasts,

Erect their tree house. ...(more)

_______________________

The Story of Napalm

Greg Bem reviews Don Mee Choi, Hardly War

berfois

Perhaps in many ways the entire book is about the experience of the Photograph . . . as the daughter of the Operator living inside the Camera with Spectrum, with History. Everything and everyone inside the Camera are mad. They also enact their wish, the wish to return to the world.

It is difficult to talk about war. And yet many humans do. But how we do it and for how long is another question. Especially with relationships to information today, and relationships to time, I am thinking of fragments. Thinking of spliced conceptions. Thinking of history and those who came before, dealt with war before, and our relationship to those people, to how they interpret and process, and what we owe them. Those people, those we know closest. Family, friends, our allies, or our enemies. But different eras have different meanings. So is there coherence? What provides the link between what was spoken then, lived then, and what is spoken now, lived now? War within the world, but also war within worlds. War within language. The transcendence through language, but the overlap of meaning. Mutations and morphing utility of language, and its evocation and condemnation and control of identity. Whose identity? Whose existence? Whose soul, individual and collective? The tracings of the individual through artefact or ephemera. The ability to parse and discover through historical object, through stable or unstable essence of history and memory. The process of learning, and loving and exploring through memories. The tricky wonder of art, and of words.

Don Mee Choi’s Hardly War is a book about all of these themes and problems in existing within humanity. It’s a book of process as much as it is a book of witness. As intent on uprooting a beauty of family and love as it is allowing the space for risking an approach toward the chilling effects of our brutal world, the book serves as an undertaking, as an exploration most humans cannot fathom, do not allow themselves the chance to take.

...(more)

_______________________

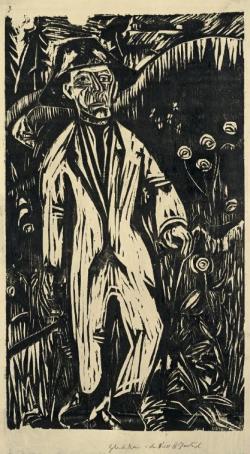

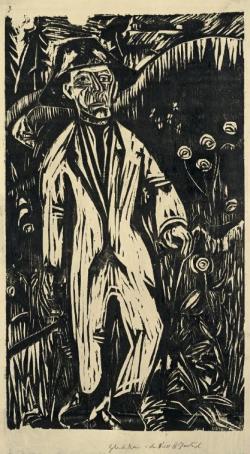

Walking Man in the Meadow

1922

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

b. May 6, 1880

_______________________

Springing the Trap of Repression from the Inside: Lacan’s Marcuse

Gad Horowitz

ctheory

(....)

Marcuse worked hard in Eros and Civilization to show that a liberated Eros would subsume the death instinct, taking it up into Life, exorcizing Death, as it were, of its sting, bringing forth nonviolent aesthetic equivalents to war.

Lacan begins and ends otherwise. Very early in life human being is constitutively divided, “split.” Language, culture, the insistence of the Other, bite into the being: a traumatic cut, a rip in being, experienced as an Intensity unbearably, painfully pleasurable. This is the first human experience. Lacan calls it “Jouissance”, a term which is untranslated in all English, Spanish, etc. versions of his work. The cut opens an abyss, an experience of loss of an unattainable object, a missing object which was never actually there, because before the cut there was no relationality, no subject, no object. The object of human desire is lost-as-such.

Psychoanalysis explores the continent of fantasy. The flora and fauna of fantasy represent the endeavour to obscure the abyss, to mend (or as Lacanians say to “suture”) the rip in being, primarily by means of identification of the being with images of self as perfect or perfectible, whether by conforming or refusing to conform, or both, but always in the eye of the Other. Adorno, Derrida, Gregory Bateson, Alfred Korzybski and others have diagnosed humanity’s pathology as “identity thinking.” From Lacan we learn the fantasy work of identification with images of perfection (and damnation) is prior to all identity thinking.

The fantasies are played out as human “reality,” sexual, cultural, and political, a reality far from the intolerable traumatic Real, yet often dangerously, painfully and deliciously close. What is insistently at work is the ambivalent attraction/terror of regression, the slide to what Lacan’s friend Bataille called “expenditure,” wasting the self, bursting its boundaries whether by self-immolation or self-expansion, especially in war. Bataille: “The desire to be consumed for no reason other than desire itself: to burn.” What Bataille’s disciple Nick Land calls “the thirst for annihilation.”

...(more)

_______________________

On Cuban Time: New Writing from the Island

Words without Borders May 2016

Cuban time moves to its own complex rhythms. It most certainly does not stand still. But neither does it sweep forward like a Swiss watch—though a pricey shop in Old Havana will be happy to sell you a Cuervo y Sobrinos, designed by a family-owned company founded in Havana in 1882 and manufactured to the highest specifications in Switzerland today. As the stories in this issue of Words without Borders show, Cuban time moves in many directions simultaneously, leapfrogging and plodding, at once groundbreaking and nostalgic, the present moment eternally stretched almost to breaking in a cosmic tug-of-war between past and future.

The Bleeding Hands of Castaways

Erick J. Mota

Translated from Spanish by Esther Allen

(....)

I’d always tell you that for some strange reason I was destined to be a dream. A wave slowly lapping at a rock without detaching a single grain of sand for any future beach. A light, finite rain that barely dampens the earth, no umbrella required.

But you’re a space man, and you needed to build me a bar on an asteroid. A bar with old beer barrels and the perfect acoustics for my voice. You promised you’d even serve a screwdriver with a real screw at the bottom of the glass. At first I laughed at your wild ideas, watching the way you looked at me with your Tuareg eyes. Then, as you explained about gravity conditioners and old USB victrolas that could be had for a song on the inter-orbital black markets and asteroids abandoned to their fate, I sometimes began to see myself in the place you were dreaming up for me. Sometimes, when I was alone, I’d see myself singing with you under the soft lights that you said would be a perfect match for my eyes, singing I’m gonna switch off the light, and think about you, and let my imagination dream . . .

...(more)

_______________________

In the Forest

Alberto Savinio

_______________________

the architecture of crisis

Owen Vince

3am

(....)

Over the past decade, this contemplation of ruins and abandonment – in the shadow of the necrotic half death which the advancement of Late Capitalism reproduces – has seen a new industry of ruin contemplation emerge. For the former Soviet eastern bloc, Owen Hatherley caustically refers to a genre of expensive coffee table books featuring “Totally Cool Abandoned Soviet Architecture”. Blogs – Abandoned Berlin, abandoned London, abandoned places. Online photo essays and Facebook groups provide expansive records and, often, explorer’s tips, for desktop archaeologists to purr and fascinate over. Hospitals, parking lots, former Olympic parks, football stadia, hotels, resorts and schools. It represents an immense and mortal infrastructure of decaying buildings which are celebrated first and foremost for the degree of their “coolness”, the weirdness of their function, the extent of their desolation. As Lyons argues, the “allure” of these ruins – including Sydney’s Magic Kingdom and the German Spreepark – are captured by “urban explorers”, creating a tendril of connection to the idea of risk, of arriving into an unknown “heart of darkness”. Richard B. Woodward is more caustic, still – to him, so-called “ruin porn” is little more than “immature” and “gawky”.

And nobody ever asks, “why?”. Why were they abandoned, and how?

Our representation of these buildings is important. To a large extent, the work of 18th c. painters and traveling Englishmen shaped how we receive the classical past of Rome. The narrative is always of Rome’s “fall”, rather than its centuries of continuity and development, or of the people who lived after it. The fall of the empire was not an act of depopulation – it was not an apocalypse. As a past, it is compressed and erased to suit aesthetic tastes of what the past should “be” and should look like. Its collapse is credited to little more than the fact that it was its “time” to collapse. The folly of empires and emperors. Edward Gibbon is still leaning over us, wagging his thick-set fingers. For those Romans who still had the “bad” taste to live among or around the ruins, to whom the baths of Caracalla were likely a nuisance, the English painters happily painted them out of the picture. They were too – “real”. Not “authentic”. I find the same problem with Lyon’s insistence that ruin aesthetics are salvaged by their offering of a travel to “the future within the present”, as if they can serve only as a warning. The implication is that the “ruin” is beyond hope, and its causes are unstoppable.

And so, this practice of “looking” is not a neutral activity, and aesthetics are not disconnected from real effects and worlds. ...(more)

_______________________

Naturalism and Metaphors. Towards a Rortian Pragmatist Aesthetics [pdf]

Kalle Puolakka

European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy

(....)

Effective metaphors make us see things in a different light. Yet, metaphors do not have

to be assumed to possess cognitive content to achieve this. Rorty elaborates the naturalistic

account of the cognitive value of metaphor with the distinction between causes of beliefs

and reasons for beliefs. Metaphors are for him similar to other “unfamiliar noises” we en-

counter in that their functioning cannot be fully predicted by our present means and they

cannot be assigned determinate content by our present cognitive resources. For this reason

metaphors cannot serve as reasons for beliefs. This, however, does not deprive metaphors

of cognitive significance, for their lack of cognitive content does not imply that they could

not have a causal role in shaping our beliefs and desires. Good metaphors make us attend to

novel aspects in our environment and they can, thus, make us change our beliefs. This,

however, does not mean that the metaphor expresses the novel belief we come to hold as a

result of the cognitions the metaphor causes in us. From a naturalistic perspective, it is in

other words a mistake to think that a metaphor’s capacity to reveal new aspects in one’s

surroundings is based on its conveying information that we come to acquire as a result of

grasping the meaning of the metaphor. As Davidson himself explains, “joke or

dream or metaphor can, like a picture or a bump on the head, make us appreciate some fact

– but not by standing for, or expressing the fact”.

(....)

Though Rorty does not develop his view of metaphors as one of the central means for

enhancing the feeling of solidarity in relation to Davidson’s naturalistic account that explic-

itly, the picture of the engagement with a metaphor that view implies reveals the full sig-

nificance metaphors may have in furthering the social values central to Rorty’s liberalism.

The engagement with a metaphor structurally overlaps in some significant respects with the

sensitivity and alertness to contextual detail Rorty finds central to the enhancement of soli-

darity. Metaphors stir the same kind of mental powers that are also at the heart of the con-

struction of solidarity, and thus metaphors become important devices for developing those

capacities required in the enhancement of solidarity. There is no common set of rules or

axioms with the help of which it could be possible to spell out what the capacity to feel

solidarity with one’s neighbours in every possible situation requires. Similarly, it is impos-

sible to give a definite list of how the similarities a given metaphor can cause us to see

should be understood and the effect the metaphor may have on our beliefs and desires. As

in the case of solidarity, all one can do with respect to metaphors is to stay imaginatively

alert. In this respect, it is understandable why Rorty thinks that the question “How do meta-

phors work?” is in fact in no substantial sense different from such questions as ‘What is the

nature of the unexpected?” or “How do surprises work?”

(....)

via Synthetic_zero

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

On Jenny Diski

1947–2016

Justin E.H. Smith

n+1

(....)

...“[. . .] we are what we are. It’s not possible (or attractive) to be better than we are simply by morally withdrawing from the mess.” So this is life, and this, it was starting to dawn on me, is philosophy. It is a bloody mess, and it is wrapped up, of necessity, with death.

(....)

In a stunning testimony written for the Swedish Göteborgs-Posten in 2013, the year before her diagnosis, Jenny invokes the bleak wisdom of Beckett’s line, “Birth was the death of him.” She wonders with Nabokov why we do not worry about the infinite abyss a parte ante, before we were born. That wasn’t so bad, was it? Why should the one that follows this temporary interruption of nothingness be any worse? Well, the thing about it is that now we’ve wallowed in the mess of life, and only slowly, in the process of what is called “maturing,” come to feel the way death looms over all of it. Thomas Bernhard had said that death makes everything, notably all this spilling of words, “ridiculous” (Es ist alles lächerlich, wenn man an den Tod denkt), but for Jenny the death-horizon was, if not exactly something to rejoice about, at least an existential condition that had its own consolation. It demanded that one not waste one’s life in boredom, nor get too distracted by, nor place too much hope in, sex, drugs, long walks, or anything else that “palls, eventually,” but instead that one must respond to death in writing, by being a writer.

...(more)

_______________________

self portrait

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Returning Boat on a Spring River

Zhang Dai-chien

(May 10, 1899 - April 2, 1983)

_______________________

living words: ‘all hues in his controlling’

Greg Gerke

3am

(....)

Words conjure. Crack a novel or poem at random and most will have a tiny shout about the outdoors. Even in JR, William Gaddis’ novel of 98% dialogue, nature bursts into the rooms where the speakers speak: “Sunlight, pocketed in a cloud spilled suddenly broken across the floor through the leaves of the trees outside.” One can’t keep it out and nature can’t keep away—it is the leveler of literature: Just want to make sure you know I’m still here, it says, and we say, Just want to make sure you are still there. With this understanding we live, banking on the picture of the earth to always be in its place. Is this a happy arrangement?

I turn to Wallace Stevens and the last canto of the Auroras of Autumn for help:

An unhappy people in a happy world—

Read, rabbi, the phases of this difference.

An unhappy people in an unhappy world—

Here are too many mirrors for misery.

A happy people in an unhappy world—

It cannot be.

What are we that a poet can take three of the most used words in English and mix and match them in such easily understandable and memorable lines of verse? We have to be magic, and why I read is to feel who we are, to apprise myself of the distinguished enterprise of being.

This is me—the child trying to be father to the man—who has read Ulysses but has not made a son, who has been under Lowry’s Volcano but never under a car to understand its underbelly or twist on an oil filter to save money while hording the bragging rights, so my love could speak of her man. I continue reading—I am adding and addled by those ideas, those bristling feelings enjambed in sentences and lines of verse, but is this filler for what is truly desired?

...(more)

_______________________

The Amassing Harmony:

Wallace Stevens and the Life of the Imagination

Peter Marshall reviews Paul Mariani, The Whole Harmonium: The Life of Wallace Stevens

berfois

(....)

Every biographer must make an Icarian flight between facts and commentary, between objective distance and personal involvement with their subject. The art of turning the events, testimonies and records of a life into a narrative arch is not without a touch of fiction: Some imagination is needed to bring a sense of life to the person found on paper. Lacking this touch, Mariani’s biography leaves Stevens hidden in its pages.

Appropriate enough. Throughout his poetry, Stevens maintains a veiled presence, thickly disguised, elusive to us as he was to himself. The substance of who he was, like the nature of the reality in which he lived, is shaken by the uncanny transformations that run through so many of his poems. Stevens left faint fingerprints on his work, and occasionally, in the mere outlines of a memory, he is seen returning to youthful moments of self-creation, immersed in a freedom that has faded into a myth of the self:

It is an illusion that we were ever alive

Lived in the houses of mothers, arranged ourselves

By our own motions in a freedom of air.

...(more)

_______________________

Morning Mist In Spring

Zhang Dai-chien

_______________________

An excerpt of Marie Silkeberg’s The Cities

Translated from the Swedish by Marie Silkeberg and Kelsi Vanada

(....)

a test of the heart. the membranes. could come in the morning. sleep. a measure of freedom. somewhere dogs bark. in the night. anxiety like a contraction. dizziness in the body. a state of shock. kicks. kicks. against fetal membranes. the streetlight-lit greenery. horned owl in the awakening city. searching gaze. over the facades. boulevards. all the cars. among lilacs and chestnuts. pollution. bullet holes in house walls. no wind in the night. homeless dogs. a flock. beyond sight. earthquake. Vrancea. six point five on the Richter scale she says. the replica. I stood in the doorway. the house swayed. all the concrete. books fell from the shelf. porcelain. the piano she says. like a black monster slowly moving across the floor. the last books fell. the body’s sensors. the hair stood up on my neck. in that moment I could have strangled someone she says. out of terror. I knew I could kill. in winter morning stillness. a flashing string of images. understandings. in the borderland. beyond the border. Stalin square. famine victims. a black dog in darkening mist. the unlit city. in haze. trembling exhaust light. the voice that speaks. has spoken. about birthing. across continents. pazhalsta. woman and child. at the crossing. the baby was all-the-way silent. cried silently. in reluctant light. the white room. I shudder every time I hear it she says. the tragedy of being a human being. after being a woman. Ukrainian. doubling in the labyrinth. to enter the darkness. change places. be left behind. become one of them. unable to be re-translated. at the very threshold of the station. birth. second birth. to feel the unexperienced. the squinting glance. the double. to embrace. life. death. winter-shadow. black or white magic. each reconstruction a loss. an erasure of erasure. it began to happen in my own life she says. Andrea’s Slope. acacias. agile and burning. fire smoke in December chill. gray military coats displayed on the fence. a line of men raking leaves on the hillside. reluctant dawn light. white church. white patterned synthetic curtains. stillness over the cobblestone streets. silent subway tunnels. despite the many people. breath like a cloud over her frozen fingers. pork fat. the taste. the smell. a strange perfume in the orange soap. revenge. torture. transition period. no end of history. no end of geography she says. archipelago in a bleeding sunset. during landing. with incredible speed. the sun sinks at the brink

...(more)

Asymptote Spring 2016

_______________________

American Merchant Mariners’ Memorial

Battery Park

Marisol Escobar

(May 22, 1930 – April 30, 2016)

_______________________

Geopolitics of Hibernation

Mckenzie Wark

(....)

How might we conceive a world where climate changes fast, and history moves slow? As it turns out, this has happened before, at least on a local scale. There have been minor blips in climate in particular geographical regions that have happened quickly, but the results are not good. The range of climate conditions under which historical forms of social organization can persist turns out to be fairly narrow. It’s likely that the kinds of social disorganization that we are already seeing in many parts of the world—along the aridity line, for example—will only spread and accelerate.

For those of us used to a comfortable life in the over-developed world, one could imagine two kinds of response to this. One would be to wake up and get on with changing our social organization into something both flexible enough to deal with unpredictable change, and that does not worsen the heating of the planet by adding yet more carbon to the atmosphere. The other responses is to go back to sleep, build a big wall, hide behind it, and send out the armed drones to attack anyone who says otherwise. As much as one might want to see the former response take hold, the latter seems to be the dominant one.

“The Geopolitics of Hibernation” was the title of an essay published by the Situationist International back in 1962. They were thinking of fallout shelters as the characteristic architecture of the time and saw these bunker forms as extruded from an insane military-industrial rationality—one that posits living a suburban life underground, with TV dinners and a washing machine, when everything above had been reduced to radioactive rubble.

(....)

Whether or not so-called “peak oil” has arrived turns out to be a complicated question which still divides the experts. In any case, there’s still oil to be had, taking us well past the point where the climate is beyond repair. But what other resources are reaching their peak? The Anthropocene is not just about one potential constraint to the endless expansion of commodified production. Perhaps we have also hit “peak phosphorous” and will have to think again about how to fertilize industrial crops.

A rather large chunk of the periodic table is involved in making contemporary technologies, and some of those elements are getting harder and harder to find in readily extractable forms. There is no doubt that the best minds of the military industrial complex have studied all this carefully. Who knows what wars they have pre-planned to secure ongoing access to chemistry.

Resource wars are no new thing. They are a defining feature of the history of geopolitics. But perhaps the resource wars of the Anthropocene have some new features. For one thing, there’s no frontier left, there’s no outside. We no longer live in an open system where resources can be drawn in from without and waste chaos dumped back out again to some hinterland. The Anthropocene is about living in a closed system, where there is no longer an “environment” against which the social can seal itself. There’s no separate place for a bunker any more.

The so-called “refugee crisis” is really a sign both that the climate wars have started, and that there is no place to hibernate from them that can endure for all that long. The contested category of “refugee” implies that there is a refuge, and soon there may be none. The proximate cause of the millions streaming over the borders and trying to enter Europe or the United States or Australia may stem from complex political, imperial, and military forces, but underneath all of that is rising climate instability, which is already pushing various kinds of social organization past the point where they can adapt.

...(more)

Berlin Biennale For Contemporary Art

via Deterritorial Investigations Unit

_______________________

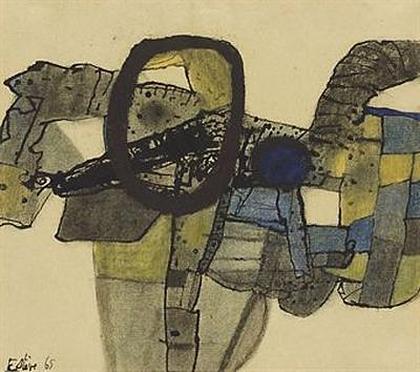

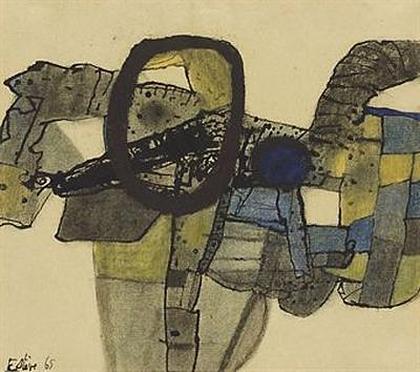

photo - mw

Maurice Esteve

b. May 2, 1904

_______________________

Child of Man

Eric Hoffman

from the Journals and Letters

of Ralph Waldo Emerson

(....)

3.

That night, I went out into the dark

And saw a glimmering star, and heard a frog.

A new scene, a new experience,

The tableau startlingly unique, and temporary.

In spite of all we do, every moment

Forms and disintegrates and in its place

A new occurrence surfaces, its minutiae

An infinite array of specifics and variants.

Each remnant, each shattered piece,

Is precisely replaced, until they reassume

Their fractured fallen positions,

Threadbare hours we manage to salvage

From the calendar’s pitiless thresher.

...(more)

OTOLITHS issue forty-one

southern autumn, 2016

edited by Mark Young

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Camus and the Aesthetics of Stone

Dwight Furrow

3 quarks daily

(....)

The world is not good enough and we can't do much about it. Soldiering on is the best we can do.

When in such a mood I like to consult Camus. No, I'm not masochistic, or at least I don't think so. The Camus that inspires me is not the fist shaking Camus of The Rebel or the dubious, Stoic-tinged Camus of the Myth of Sisyphus. There is another side to Camus that gets far too little attention. In an early essay, Nuptials at Tipasa, he writes:

The breeze is cool and the sky blue. I love this life with abandon and wish to speak of it boldly: it makes me proud of my human condition. Yet people have often told me: there's nothing to be proud of. Yes, there is: this sun, this sea, my heart leaping with youth, the salt taste of my body and this vast landscape in which tenderness and glory merge in blue and yellow. It is to conquer this that I need my strength and my resources. Everything here leaves me in tact, I surrender nothing of myself, and don no mask: learning patiently and arduously how to live is enough for me, well worth all their arts of living.

In the face of a world unresponsive to human values, despair is ruled out, for ensconced within Camus' numbing litany of all-too-human failure are lovely passages in which pure sensuous enjoyment lifts the spirit and provides justification even in life's trying moments. This is the lyrical Camus extolling what he sometimes calls the "Mediterranean life" where the live-in-moment vitality of sensory experience is a repository of meaning infusing life with significance in the absence of transcendental certification, even in the face of inevitable loss.

Intuitively, Camus' idea that meaning is to be found in the everyday rendered alluring by our willingness to see its beauty is appealing. The problem is I have never found an argument in Camus' work that links the Stoic-like absurd hero with the happy hedonist. How could something as seemingly trivial as the sun and sea provide meaning in the face of the absurd?

...(more)

_______________________

Maurice Estcve

_______________________

The Collapse

Jesse Miksic

berfois

There’s this feeling I get on the subway, when I reach a breakpoint in a book I’m reading, and I realize a whole chapter has just passed right through me without sticking, like my mind has secreted a Teflon coating.

I feel it when I browse my lists, day after day: Goodreads reviews of unremembered books, an Amazon wish list built on abandoned preoccupations, an infinite archive of vaguely interesting thinkpieces in Pocket, an RSS feed reaching into the stars.

I feel it when I look up, blinking, from two hours on Wikipedia and TVTropes.org, and I can’t even remember what curiosity led me into that labyrinth of distraction.

At these moments, I feel a subtle loss of equilibrium that marks a paradigm shift, a sea change in the way knowledge moves and settles around me. I feel our datasphere starting to overheat, and I feel myself fading away.

This feeling is part of a grand constellation of perturbations and effects, but for me, myself — the facet that reflects in my own life — it’s the feeling that I’m losing my purchase in the world of ideas. There’s so much to know… a whole universe expanding exponentially from the singularity of my free time and attention span… and simultaneously and paradoxically, it feels like knowing per se is losing its coherence. On any passing fascination, the amount of reading available and expected approaches infinity, and in inverse proportion, the amount of information I can absorb dwindles to zero. Between wanting to read a text, and having forgotten it, my connection with the content itself is compressed into nothingness.

...(more)

_______________________

Fifty shades of open

Jeffrey Pomerantz, Robin Peek

Abstract

Open source. Open access. Open society. Open knowledge. Open government. Even open food. The word “open” has been applied to a wide variety of words to create new terms, some of which make sense, and some not so much. This essay disambiguates the many meanings of the word “open” as it is used in a wide range of contexts.

First Monday Volume 21, Number 5

_______________________

Maurice Estcve

_______________________

Pure Vibe

Christopher Tayler reviews Zero K by Don DeLillo

lrb

(....)

One constant throughout these risk-filled spirit voyages has been DeLillo’s superbly take-it-or-leave-it posture towards the laity. ‘The writer leads, he doesn’t follow,’ he wrote in a letter to Jonathan Franzen in 1995. ‘The dynamic lives in the writer’s mind, not in the size of the audience. And if the social novel lives, but only barely, surviving in the cracks and ruts of the culture, maybe it will be taken more seriously … A reduced context but a more intense one.’ These are the words of a writer near the peak of his renown reassuring a fretful colleague, but they’re clearly marked by DeLillo’s time as a cultish, solitary figure in the 1970s, when intensity of context allowed him to thrive. There was a mainstream then and his place was outside it, a ‘child of Godard and Coca-Cola’, as the narrator of Americana (1971) calls himself, working up his vision with the singlemindedness of Ballard or the young Cronenberg. His high ambitions didn’t mean it wasn’t OK to dabble in thrillers and sports and science fiction, and to be funny as well as apprehensive about the image-addled world he saw coming into being. At the same time, he was free to trade in pure vibe, in ‘memory chains and waking dreams and every kind of mindlife’, and to manipulate large themes from a distance by writing about eloquent characters with a propensity to be dazzled by, as one of them puts it, ‘the neon of an idea’.

...(more)

|