|

Rimbaud

1975-6

Frank Auerbach

b. April 29, 1931

_______________________

Walking in Literary Shoes:

Franz Kafka and Robert Walser on Walking, and the Horrors of Modernity

Jeffrey A. Bernstein

berfois

What do we do when we walk? What happens to us? Do we walk in order to get somewhere? Do we walk to get our bodies moving? Our minds? Do we walk to form an image and identity of ourselves (one thinks of Thoreau’s pronouncement “tis a great art to saunter”)? Do we walk to figure out problems? Or to escape from them? And what about missed walks? Are they happenstance? On purpose? Are they symptoms? When we ask the question concerning what we do when we write about walking, the problems only multiply. For here, the question is one of using the image or action of ‘walking’ as a moment of reflection, or an optic, in order to communicate something else. This holds equally for writing about the inability to walk as it does for writing about walking.

(....)

It cannot simply be a matter of holding that Kafka was symptomatic (to which his autobiographical writings surely attest) while Walser was insane (despite the fact that, when not moving from hotel to hotel as temporary residence, he spent the last 2-3 decades of his life in psychiatric hospitals). This reductive mistake would be analogous to suggesting that their respective texts were simply talking about walks (or even actually taking walks) rather than using walking as a lens through which readers are given to understand something. Instead, I wish to pursue the distinction between symptom and madness—what Freud calls ‘neurosis’ and ‘psychosis’—as narrative strategies by which Kafka and Walser are attempting to show us something. For Kafka and Walser, the literary trope of ‘walking’ presents itself in both a neurotic (i.e., symptomatically stuck) and psychotic (i.e., disavowing) manner. And despite the fact that these two authors are generally understood to have shied away from political or historical concerns (Walser even more so than Kafka), I want to argue that the access which they grant us to the political and historical time period in which they wrote lies in the different uses that they make of this trope.

...(more)

_______________________

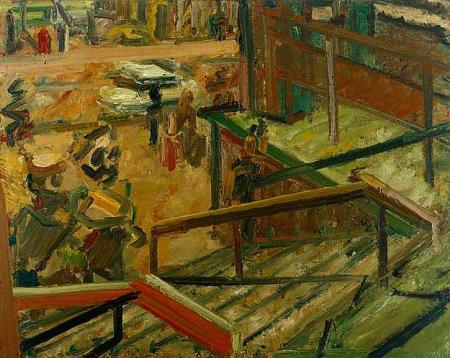

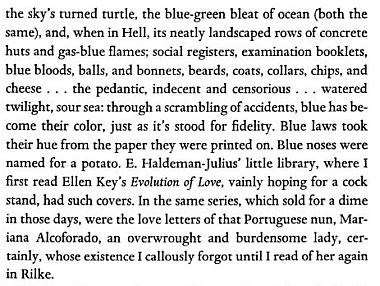

Euston Steps

Frank Auerbach

1980-81

_______________________

Walk

Daniel Bosch

There is room

In the Ouse

All one has

To do is

Take it take

A step just

One at first

The mud will

Hold wet stones

Will glue thick

Soles all Ouse

Has to do

Is rise not

All at once

Black mass just

Part for whole

None at rest

All one has

To do is

Walk on wet

Soles take steps

Rise walk walk

As if healed

Reach touch one’s

Own bones the

Still warm stones

Sewn in the

Ouse will make

Room for all

...(more)

Queen Mob's Tea House

_______________________

Walking

opening pages

Thomas Bernhard

Translated from German by Kenneth Northcott

THERE IS A CONSTANT tug-of-war going on between all the possibilities of human thought and all the possibilities of a human mind's sensitivity, and between all the possibilities of human character.

Whereas, before Karrer went mad, I used to go walking with Oehler only on Wednesdays, now I go walking--now that Karrer has gone mad--with Oehler on Monday as well. Because Karrer used to go walking with me on Monday, you go walking on Monday with me as well, now that Karrer no longer goes walking with me on Monday, says Oehler, after Karrer had gone mad and had immediately gone into Steinhof. And without hesitation I said to Oehler, good, let's go walking on Monday as well.

(....)

If we do something, we think about what we are doing until we are forced to say that it is something nasty, something low, something outrageous, what we are doing is something terribly hopeless and that what we are doing is in the nature of things obviously false. Thus every day becomes hell for us whether we like it or not, and what we think will, if we think about it, if we have the requisite coolness of intellect and acuity of intellect, always become something nasty, something low and superfluous which will depress us in the most shattering manner for the whole of our lives. For, everything that is thought is superfluous. Nature does not need thought, says Oehler, only human pride incessantly thinks into nature its thinking. What must thoroughly depress us is the fact that through this outrageous thinking into a nature which is, in the nature of things, fully immunized against this thinking, we enter into an even greater depression than that in which we already are. ...(more)

_______________________

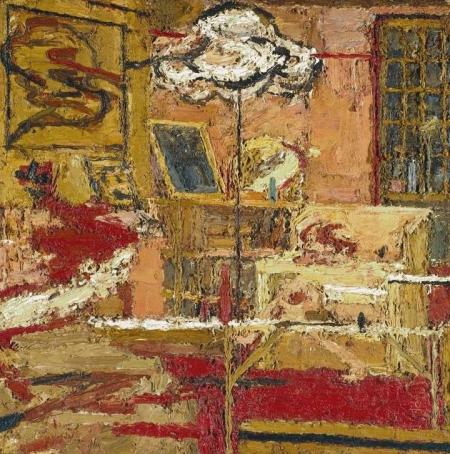

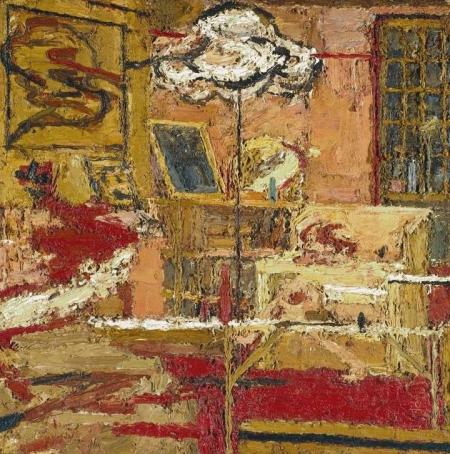

the sitting room

Frank Auerbach

_______________________

Why Spinoza still matters

At a time of religious zealotry, Spinoza’s fearless defence of intellectual freedom is more timely than ever

Steven Nadler

aeon

... Spinoza’s contemporaries, René Descartes and Gottfried Leibniz, made enormously important and influential contributions to the rise of modern philosophy and science, but you won’t find many committed Cartesians or Leibnizians around today. The Spinozists, however, walk among us. They are non-academic devotees who form Spinoza societies and study groups, who gather to read him in public libraries and in synagogues and Jewish community centres. Hundreds of people, of various political and religious persuasions, will turn out for a day of lectures on Spinoza, whether or not they have ever read him. There have been novels, poems, sculptures, paintings, even plays and operas devoted to Spinoza. This is all a very good thing.

(....)

Spinoza’s views on God, religion and society have lost none of their relevance. At a time when Americans seem willing to bargain away their freedoms for security, when politicians talk of banning people of a certain faith from our shores, and when religious zealotry exercises greater influence on matters of law and public policy, Spinoza’s philosophy – especially his defence of democracy, liberty, secularity and toleration – has never been more timely. In his distress over the deteriorating political situation in the Dutch Republic, and despite the personal danger he faced, Spinoza did not hesitate to boldly defend the radical Enlightenment values that he, along with many of his compatriots, held dear. In Spinoza we can find inspiration for resistance to oppressive authority and a role model for intellectual opposition to those who, through the encouragement of irrational beliefs and the maintenance of ignorance, try to get citizens to act contrary to their own best interests.

...(more)

_______________________

Primrose Hill Summer Sunshine

Frank Auerbach

1964

_______________________

Antin's 'Notes for an Ultimate Prosody' Revisited

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

Most discussions of prosody begin and end with metrics, but the contribution of meter to the sound structure of all poetry that was neither sung nor intended for musical

accompaniment, when it has been at all specific, has been trivial. Yet because most writers on prosody would probably dispute this, and since some recent poets have worked out sound structures on the basis of implicit defects in metrical theory, it's probably worth taking a look at the metrical background.

...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

Two Poems

John Ashbery

conjunctions

Playing in Darkness

The men on top of the hill

launched a new dirt lobby

meant to outstrip the precious,

that is, previous, tentative

by a better than three-to-one margin.

And slightly without you

horrified spectators esteem the rain input.

You would have too crude shelter

of boards circling a central meaning place.

Arrhythmia! You pant. Not by a long

chalk, crotch shot

on a bowling team, English-worthy kebabs.

Let Fido confide, or cough up. I can’t

vouch for the clientele, in lockdown mode.

They don’t want you there, aporia.

Mrs. Mulligan down the hall broached the topic

long after everyone had gone home

into the night.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

The Word Brambles, You Say

Yves Bonnefoy

translated by John Naughton

The word brambles, you say? Then I think of

Those boats stranded in sea-weed

That children drag on summer mornings

With cries of joy through dark pools of water.

Because in some, you see, there are traces

Of a fire that burned there at the prow of the world

–And on the blackened wood where time has left

The salt that seems a sign but vanishes,

You too shall love the shimmering water.

Brief is the flame that goes out to sea,

But when it is quenched against the wave,

The smoke is filled with iridescence.

–The word brambles is like this sinking wood.

And poetry, if we can use this word,

Is it not still, there where the star

Seemed to beckon, but only toward death,

Knowing how to love this light? To love

To open the kernel of absence in words?

In the Shadow's Light

Yves Bonnefoy

translated by John Naughton

University of Chicago Press

_______________________

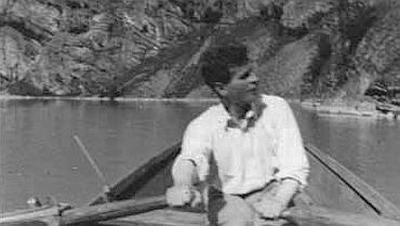

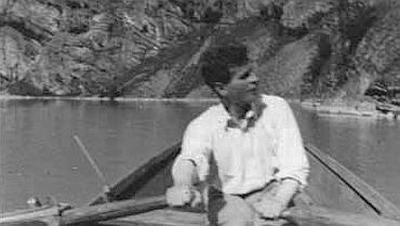

the remaining foundation

In Search of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Secluded Hut in Norway

A Short Travel Film

22 min.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

b. April 26, 1889

rowing from Skjolden to his house

Wittgenstein’s house

near Skjolden, Sogneflord, Norway

1914

_______________________

Intellectual Freedom in the Age of Social Media

Adam Kotsko

(....)

What makes the situation so difficult, though, is that we academics do need social media — particularly academics from marginalized groups. The intellectual community that it can create is far beyond what can be expected in even the healthiest academic department. The question is how to build that community without increasing our “exposure.”

(....)

... we should acknowledge that few academics have the skills or disposition needed to deal effectively with the general public. Even those who do should know better than to expect much intellectual nourishment from those encounters. The public square is not where any of us do our best thinking, because the intellectual life requires authentic comrades, not just whoever happens to come along. It also requires solitude, for developing ideas at length without the need to respond to questions or criticism at every step. In short, intellectual freedom entails a space of freedom from the general public, and we need to be more intentional about creating such spaces. .....................................................

Continental Thought and Theory: A Journal of Intellectual Freedom

Issue 1, April 2016

Edited by Michael Grimshaw and Cindy Zeiher

Introduction: What is Intellectual Freedom Today? A Provocation

Mike Grimshaw and Cindy Zeiher

(....)

The claim of the need for intellectual freedom in world of the academic precariat is an underlying tension across all contributions. And so the potentiality of responses could go on, like a manifesto of and for this spectre, this claim, this opiate perhaps, of ‘intellectual freedom.” And yet, as the number of respondents situated in a variety of fields, demonstrates there is something, a multiplicity of ‘somethings’, that we feel need to be attempted to be articulated, critiqued, argued and advanced as to the question ‘what is intellectual freedom today?’

More so, the precise way the question can be responded to, the manners in

which it can be engaged with is itself a central question of freedom for the

intellectual, of freedom as to how to undertake the practice of the intellectual. ....

via Philosophy In A Time Of Error

_______________________

In Search of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Secluded Hut

_______________________

Amnesia or Transmission

Jelica Šumic Riha

Continental Thought and Theory

(....)

The present time could then be designated as a time of amnesia, a peculiar amnesia to be sure, since we are not dealing here simply with the forgetting of some past events whose effects, to paraphrase Lacan, have stopped being written in the present conjecture. It is not merely about forgetting the forgotten. The amnesia of the amnesia is rather an anticipation of the amnesia, a readiness to forget in advance, a programmed amnesia, so to speak. Hence, for us, something is doomed to be forgotten even before it has actually taken place. This anticipated, programmed amnesia is namely the ability to wipe out not only what has happened, but to annihilate the very idea of the possibility for something to happen, in short, the ability to erase the possibility of the possible. What is crucial today, however, is not the question: how to restore the traces of the forgotten/effaced past, but rather: how to deactivate our readiness in advance to forget.

It is precisely in the present conjecture of the amnesia of the possibility of another world that the articulation of philosophy’s contemporaneity to the question of transmission has attained its central place. It is not a question, here, of merely bridging the temporal gap between the generation of the sixties and the present generation. What is at stake here is nothing less than the possibility of transmission under the circumstances of contemporary nihilism, a transmission from the “evental generation”, a generation that, in effect, experienced in the 1960s, if only for a brief moment, the possibility of a new beginning in the guise of a categorical departure from the existing state of affairs, to a properly nihilistic generation, marked, not by the event but by its absence, a generation that was literally marked by the nothing, a generation that was under the spell of the dominant ideology, according to which a new beginning that could be considered a clear-cut rupture capable of founding a new world and thus inaugurating a new time, a new historical epoch is no longer possible.

How then can the past beginning be inscribed in such a conjecture in which the gap separating the evental from the nihilistic generation seems to be ineliminable? ....

Montauk 1

Willem de Kooning

b. April 24, 1904

_______________________

Living in History

J.H. Prynne

Walk by the shore, it is

a cool image, of water

a bearing into certain

distinctions, as

the stretch, out there

the temple of which way

he goes; and cannot shake

the haze, from

a list of small

flames.

He wants

only the patient ebb, as

following the shore: that’s

not honest, but where

his foot prints and

marks his track

in the fact of

the evening

the path where he grabs at

motion, like a moist plant

or the worth, of

hearing the tide come in.

Walk on it, being a line, of rest

and distinction, a hope now lived up

to, a coast in awkward

singular desires

thigh-bone of the

world

from J.H. Prynne, The White Stones, 1968

_______________________

Karel Appel

b. April 25, 1921

_______________________

Turning-Point

Rilke

(translated by Stephen Mitchell)

presented by flowerville

(....)

Looking how long?

For how long now, deeply deprived,

beseeching in the depths of his glance?

When he, whose vocation was Waiting, sat far from home—

the hotel's distracted unnoticing bedroom

moody around him, and in the avoided mirror

once more the room, and later

from the tormenting bed

once more:

then in the air the voices

discussed, beyond comprehension,

his heart, which could still be felt;

debated what through the painfully buried body

could somehow be felt—his heart;

debated and passed their judgment:

that it did not have love.

(And denied him further communions.)

For there is a boundary to looking.

And the world that is looked at so deeply

wants to flourish in love.

Work of the eyes is done, now

go and do heart-work

on all the images imprisoned within you; for you

overpowered them: but even now you don't know them.

Learn, inner man, to look at your inner woman,

the one attained from a thousand

natures, the merely attained but

not yet beloved form.

...(more)

_______________________

Door To The River

Willem de Kooning

_______________________

Justin E. H. Smith on six types of philosophers

(....)

Is this book philosophy, or is it about philosophy?

JS: I don’t know that there can really be a valid distinction here. By the same token, I’ve never understood what people mean when they talk about ‘metaphilosophy’. We’re all just trying to come to a clearer understanding of the nature of this activity we’re engaged in, in order, in part, to better engage in it. Philosophy is peculiar in that a great deal of effort is expended, by those who profess to practice it, in seeking to determine where its boundaries are, and what falls outside of them. This is a problem sedimentologists, say, don’t have, and one might easily suspect that philosophy is essentially constituted by this activity, that there’s not much left over to do once philosophers have stopped trying to determine what philosophy is not. I think my approach, the transregional and wide-focused historical survey of the very different ways people we think of as philosophers have themselves conceived what they were doing, helps to establish this point: ‘philosophy’ is said in many ways, to paraphrase Aristotle. I’m sure some critics who have some stake in portraying philosophy as essentially thus rather than so, or vice versa, will be quick to say that this book is ‘not philosophy’. But I think I can survive that, and in fact I think they’ll be helping to support my thesis.

(....)

You draw on many sources that are not traditionally considered philosophy in the narrow sense. What is the purpose of this?

JS: I just don’t know how one could possibly coherently define the corpus of texts that deserve to be included in, as it were, the imaginary library of the history of philosophy. Recently (too recently to be included in the book) I’ve been thinking a great deal about the philosophical problem of the concept of ‘world’, as it developed in the 17th century, and the way in which this development is central for our understanding of the metaphysics of possibility, counterfactuals, one of Kant’s three transcendental Ideas, and so on. I’ve learned a great deal about the history of this concept from the work, in French, of Édouard Mehl. One thing I’ve come to appreciate is that this concept simply cannot be adequately understood without reading early modern novels, particularly the ones we might call ‘proto-science fiction’, such as Cyrano de Bergerac’s Les états et empires de la Lune. Am I supposed to exclude that just because it’s not a treatise? But then I will fail to adequately understand the philosophical problem that interests me, and that would be bad.

Often we are willing to pay attention to things that canonical philosophers say that are, quite frankly, no less fantastical than 17th-century lunar fantasy novels, simply because they are already categorized as canonical philosophers and therefore, we presume, everything they say is of interest. So Leibniz says that every drop of water in a pond is a world full of beings, and that is poetic and wonderful, but is it any more worthy of our attention as philosophers than when, say, Walt Whitman finds that he incorporates “gneiss, coal, long-threaded moss”? Both capture something profound about nature and our place in it. Whitman says it better, in my view, and there’s no reason not to pay attention to it, as philosophers, on the grounds that Whitman didn’t also come up with the principle of sufficient reason or the infinitesimal calculus.

...(more)

The Philosopher: A History in Six Types

Justin E. H. Smith

spring comes to the backroads of the Lanark highlands

photo - mw

_______________________

'the pleasure of / companionship'

A review of The Oppens Remembered: Poetry, Politics, and Friendship edited by Rachel Blau DuPlessis

Eric Hoffman

jacket2

(....)

As DuPlessis remarks in her contribution, writing was for Oppen an important means of connection with the world, one that became an almost existential means of commitment to both self and world. Oppen argued with himself and with others through his poetry, which was often filled with contradiction. Yet, as DuPlessis notes, he was also “engaging seriously with poetics and politics in his letters … He needed contact … He needed a circle, a coterie, a cenacle, and he sought actively to sustain that intellectual, social, and poetic network” (195–96). Anthony Rudolf, poet and friend of the Oppens during the 1970s and ’80s, concurs, arguing that “the life and work of this existentialist lodestar seem[s] more dialectically integrated than that of any other writer. By this I mean that his ontological integrity was peculiarly transparent and bound up with the purity of his writerly vision, whether in words or in their absence”.

The essays in this present volume form a kind of haphazard biography; nevertheless DuPlessis has done a heroic job of organizing the volume so that it follows a certain narrative trajectory. Given DuPlessis’s stated premise “that any biographical relationship is built from the dynamic space of the encounter, the space of the between,” the constraints and demands of biography, which are significant, are here somewhat less imposing. The Oppens Remembered, she explains,“is not so much the ‘life’ of George Oppen and Mary Oppen” as it is “the establishment of a dialogue, a ‘between,’ at the moment when one’s own life and the lives of the Oppens interacted with particular intensity”.

...(more)

_______________________

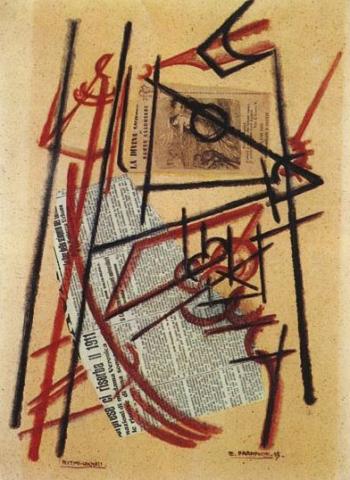

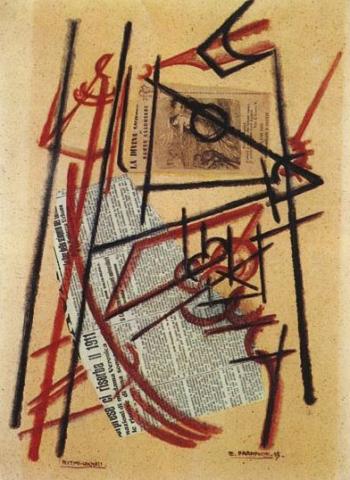

Guglielmo marconi

1939

Enrico Prampolini

1894-1956

_______________________

Arthur Kroker: Hyperstitional Gazer of Futurity

alien ecologies

"Post-history has been 'driftworks,' an indeterminate and increasingly violent series of technological experiments on the horizon of existence itself: the acceleration of space under the sign of digital culture until space itself has been reduced to a 'specious present,' and the social engineering of time into a micro-managed prism of empy granulartities."

- Arthur Kroker

As an maverick educator Arthur Kroker is a nexus of hybrid thought, a convergence of other scholars and philosophers, scientists and performativity thinkers and artists, yet he is able to take their thought and derive from it a glossalia of our hypercapitalist nihilism and hyperstitional memes, amplifying and simplifying them it into intelligible soundbytes for the hungry masses yearning for a meaning that has no meaning. In that he is typical of those singular drifters on the edge of our present apocalypse or 'revealing' moment, who jut ahead like vagrant poets of temporal dreams, his antennae always in the netwaves gathering the electronic thoughts from the hypervalent wires of futurity.

...(more)

_______________________

Enrico Prampolini

_______________________

It's not a debate, It's a war [pdf]

Nina Power

(....)

If anyone deviates from the ‘rules’, that is to say sees the debate-form for

the sham it is, or takes to the streets, displacing the imposed ‘platform’

for the construction of a new order, then the true face of all those who

defend ‘debate’ is revealed: suddenly those who are most powerful

pretend that they are under siege by those who are ‘unreasonable’ – we

see this lately at universities where those with bigoted views pretend that

they are forced to pull out because of the menace of protest, to cities

when politicians responding to the riots fall over themselves not to

understand why people might resent being killed and harassed by police

officers who never suffer any consequences.

Debate is a cover-story: never having to be honest about your true

intentions while pretending to be open-minded. Debate dissociates

argument from passion; phony talking-points from real life. There are

multiple things we do not agree about – and we also disagree with the

way in which you want us to say it. The narrowness of the debate-form

allows those with power to dictate the boundaries of ‘reasonable’

discussion and ignore (or police) everything that happens outside it. But

really, from Oxbridge to courts to government, we can easily see it’s not

a debate, it’s a war.

...(more)

Hostis

via Flowerville

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

old burning pieces of experience

from A Note in Music

Rosamond Lehmann

presented by Flowerville

(....)

It does not ease the burden of the past to share its recollections; for with each plunge into it, each withdrawal, something is left behind that weighs more heavily than memory; something that can never be shared or imparted -- a sense of accumulating unease, surprise and contrast, of going alone, in unsuspected isolation, on one's way; and worse, a comfortless suggestion that the way -- life, in fact -- is without continuity. Is it possible to look back from the present as if one watched the reel of a moving picture wound smoothly the reverse way from its close: to say, that time and that hour brought one inevitably, with only apparent deviation, to this hour, this place? No, as one rushes headlong, flying with Time, portions of life split off and float away, one little world after another; and looking back, one sees them behind one as stars and constellations. Old burning pieces of experience shine now from their fixed places with unimpassioned ray; perhaps that fragment torn apart with cruellest wrench and most shattering concussion now hangs there, close indeed, but cold, all fires extinct, like that dead star moon. And between these little lights lies trackless darkness: chaos and old night close up on one's heels, swallow the path forever.

...(more)

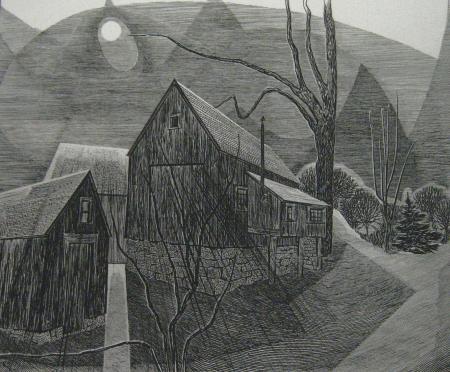

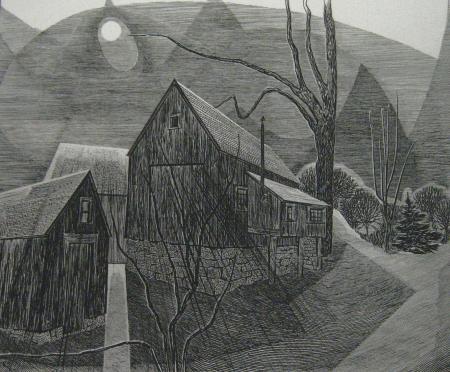

Armin Landeck

(1905-1984)

_______________________

Thin-Sliced Thoughts and Theory's Ends

Mark Andrejevic

Abstract

This article explores a variety of techniques for “cutting through the clutter” in an era of information glut: body language, neuromarketing, and data mining. It traces connections between these different strategies by arguing that they converge on an understanding of the social, political, and economic roles of information, which challenge the empowering promise of the digital information revolution. The attempt to short-circuit the discursive content of communication in order to get straight at the underlying sentiment is symptomatic of an impasse that Slavoj Zizek describes in terms of the demise of symbolic efficiency. The promise of direct access to emotional truths modeled, for example by deception detection experts on the show Lie to Me compensates for what might be described as a vernacular postmodernism in which representations are understood to be not only subject to contrivance, but completely reducible to it. The result, this article argues, is a shift in the relationship of information to power, and thus in strategies for challenging or resisting it.

MediaTropes

_______________________

On being (not quite) dead with Derrida

Bob Plant

Abstract

If mortality is the most important fact about us, then it is reasonable to think that fear of death is our most fundamental fear. Indeed, while philosophers continue to disagree about whether it is rational to fear death, they tend to assume that fear is the most common, natural response our mortality provokes. I neither want to deny the reality of this fear nor evaluate its rationality. Rather, drawing on Derrida’s remarks on ‘quasi-death’, I will argue that (i) fearful or not, death pervades everyday life; (ii) imagining one’s own death, and thereby remaining semi-present as a spectral observer, is not (as some allege) inherently misleading; and (iii) taking these imaginings seriously highlights another response we have toward our own mortality that is at least as significant as fear; namely, prospective, self-directed grief.

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

The Book of Dead Philosophers [pdf]

Simon Critchley

Introduction

This book begins from a simple assumption: what defines human life in our corner of the planet at the present time is not just a fear of death, but an overwhelming terror of annihilation. This is a terror both of the inevitability of our demise with its future prospect of pain and possibly meaningless suffering, and the horror of what lies in the grave other than our body nailed into a box and lowered into the earth to become wormfood.

We are led, on the one hand, to deny the fact of death and to run headlong into the watery pleasures of forgetfulness, intoxication and the mindless accumulation of money and possessions. On the other hand, the terror of annihilation leads us blindly into a belief in the magical forms of salvation and promises of immortality offered by certain varieties of traditional religion and many New Age (and some rather older age) sophistries. What we seem to seek is either the transitory consolation of momentary oblivion or a miraculous redemption in the afterlife.

It is in stark contrast to our drunken desire for evasion and escape that the ideal of the philosophical death has such sobering power.

(....)

To philosophize, then, is to learn to have death in your mouth, in the words you speak, the food you eat and the drink that you imbibe. It is in this way that we might begin to confront the terror of annihilation, for it is, finally, the fear of death that enslaves us and leads us towards either temporary oblivion or the longing for immortality. As Montaigne writes, "He who has learned how to die has unlearned how to be a slave." This is an astonishing conclusion: the premeditation of death is nothing less than the forethinking of freedom. Seeking to escape death, then, is to remain unfree and run away from ourselves. The denial of death is self-hatred. ...

(....)

_______________________

Armin Landeck

_______________________

The Mental Disease of Late-Stage Capitalism

Joe Brewer

(....)

...we should have seen this coming. Build an economic system based on wealth hoarding and presumed scarcity and you’ll get what was intended. The system is performing exactly as it was designed to. That is why wages have stagnated in the West for 30 years. It is why 62 people are able to have the same amount of wealth as 3.7 billion. It is why politicians are bought by the highest bidders and legislation systematically serves the already-rich at the expense of society.

A great irony of this deeply corrupt system of wealth hoarding is that the “weapon of choice” is how we feel about ourselves as we interact with our friends. The elites don’t have to silence us. We do that ourselves by refusing to talk about what is happening to us. Fake it until you make it. That’s the advice we are given by the already successful who have pigeon-holed themselves into the tiny number of real opportunities society had to offer. Hold yourself accountable for the crushing political system that was designed to divide us against ourselves.

...(more)

via forgottenness

_______________________

Colosseum

Armin Landeck

1955

_______________________

Revision

(....)

How light we are. How light our lives are. We weigh nothing. We have no substance. We lack, but what is it that we lack? We hurt, but what was it that wounded us? We took a blow – but what struck that blow? We stagger. But what was it that made us stagger? We were struck, robbed, and left for dead. But what was it that struck us and left us for dead?

We know too much. We understand too much. Our knowing is knowingness. Our understanding, cynicism. There is nothing fresh about our knowledge. We are not discoverers. Nothing came to us firsthand, or even secondhand. We are overhearers. We’ve listened. We’ve borrowed. We’ve found nothing out for ourselves.

We suffer, but not from anything in particular. We suffer, but it is not from any particular malaise. Nothing is wrong with us. It’s just that we’re lost. It’s just that we’re out of synch with the world. It’s just that we missed our appointment with the world. That we don’t know what is happening.

Our memories are false. They lack depth. They lack reality. We’re impostors. Who is it we’re trying to be? What are we trying to pass off? These are not our lives. This is not our world. We are not who we are. But who are we?

Our lives are not our own. Our moods are not our own. The days pass without sense. The nights pass without rest.

We do not live as our forebears lived. We are not of the world as our forebears were. We walk more lightly on the earth.

...(more)

Nietzsche And The Burbs

photo - mw

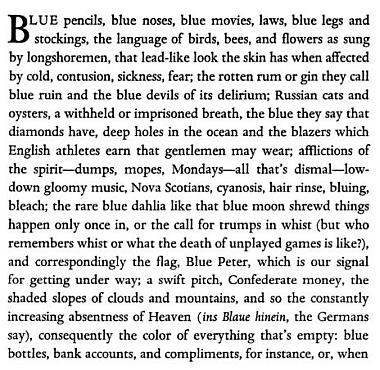

On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry

William H. Gass

google books

photo - mw

_______________________

William H. Gass, post-post-everything author

Benjamin Weissman

LA Review Of Books

(....)

... Thank God that morality for Gass is the ugly truth laid bare, grotesqueries and all, and that simple punishments, happy endings, and “lessons learned” are not suitable for the big reality of his fiction. What he has to say about humanity is communicated not by plot but through the radical vitality and violent inventiveness of his language.

Gass’s relationship to language is at once baroque, modernist, and extremely post-post-everything. He’s bent and invented more words in English than any wordsmith I can think of. His “On Being Blue,” a meditation on the color blue, is one of the most unique philosophical poetic riffs in world literature. Gass is so often pure music. You can’t find a single book review or any of his utterances in print where he’s not totally on point, being beautiful and perfect with his prose. Over the course of a 60-year career, his style and big fat word riffing has never dropped, nor has his tonal range narrowed.

(....)

In the revised and expanded preface to his first collection of stories, “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country and Other Stories,” William Gass writes about searching for the better word, since in his mind there always is a better one, and that insistence, that personal demand and writerly pressure, is central to his achievement as a fiction writer and critic. That contract with himself has also influenced several generations of writers. David Foster Wallace comes to mind. But his effect on other writers is not as traceable as the Barthelme-absurdist influence. Gass’s heirs are diffuse, his lineage is less specific, his talents, the full complex rainbow; those who’ve fallen under his spell have also spread far and wide.

(....)

Life-long readers of Gass know this: the man has never written a sentence that isn’t astonishing. He has the humility, scope, and all-embraciveness of Montaigne, the promiscuity of Bataille, and he is a despiser of plots. Conventional narrative is like rat poison to Gass. Not in my house, not on my page has always been his wide postmodern stance. Conventional narrative, to him, is the great stifler. It sends the wrong message to the world, of rigidity and unpleasant imposed order, manipulative hygiene that smells like ammonia. For Gass, conventional narrative kills the life inside language.......(more)

_______________________

A defence of ardour

Adam Zagajewski

Translation by Clare Cavanagh

eurozine

(....)

After a time I understood that I could draw certain benefits both from the wartime disaster, the loss of my native city, and from my later wanderings – as long as I wasn't too lazy and learned the languages and literatures of my changing addresses. And so here I am, like a passenger on a small submarine that has not one periscope but four. One, the main one, is turned toward my native tradition. The other opens out onto German literature, its poetry, its (bygone) yearning for eternity. The third reveals the landscape of French culture, with its penetrating intelligence and Jansenist moralism. The fourth is aimed at Shakespeare, Keats, and Robert Lowell, the literature of specifics, passion, and conversation.

(....)

... we find ourselves in a very ironic and sceptical landscape; all my four periscopes reveal a similar image. The last bastions of a more assertive attitude stand guard perhaps only in my homeland.

(....)

Some authors flog consumerist society with the aid of irony; others continue to wage war against religion; still others do battle with the bourgeoisie. At times irony expresses something different – our flounderings in a pluralist society. And sometimes it simply conceals intellectual poverty. Since of course irony always comes in handy when we don't know what to do. We'll figure it out later.

(....)

Too long a stay in the world of irony and doubt awakens in us a yearning for different, more nutritious fare. We may get the urge to reread Diotima's classic speech in Plato's Symposium, the speech on the vertical wanderings of love. But it may also happen that an American student hearing this speech for the first time will say, "But Plato's such a sexist". Another student will note, on reading the first stanza of Hölderlin's "Bread and Wine", that in our great cities today we can't experience true darkness, true dusk, since our lamps, computers, and energies never shut down – as if he didn't want to see what really matters here, the transition from the day's frenzy to the meditation offered us by night, that "foreigner".

We're left with the impression that the present day favours only one stage of a certain ageless, endless journey. This journey is best described by a concept borrowed from Plato, metaxu, being "in between", in between our earth, our (so we suppose) comprehensible, concrete, material surroundings, and transcendence, mystery. metaxu defines the situation of the human, a being who is incurably "en route". Simone Weil and Eric Voegelin (thinkers who loathed totalitarianism and from whom I first learned about Plato's metaxu) both drew upon this concept, albeit somewhat differently. Voegelin even made it one of the key points of his anthropology.

We'll never manage, after all, to settle permanently in transcendence once and for all. We'll never even fully learn its meaning. Diotima rightly urges us toward the beautiful, toward higher things, but no one will ever take up residence for good in alpine peaks, no one can pitch his tent there for long, no one will build a home on the eternal snows. We'll head back down daily (if only to sleep ... since night has two faces. It is a "foreigner" summoning us to meditation, but it's also a time of absolute indifference, of sleep, and sleep demands that ecstasy be utterly extinguished). We'll always return to the quotidian: after experiencing an epiphany, writing a poem, we'll go to the kitchen and decide what to have for dinner; then we'll open the envelope holding the telephone bill. We'll move continuously from inspired Plato to sensible Aristotle ... And this is as it should be, since otherwise lunacy lies in wait above and boredom down below.

We're always "in between" and our constant motion always betrays the other side in some way. Immersed in the quotidian, in the commonplace routines of practical life, we forget about transcendence. While edging toward divinity, we neglect the ordinary, the concrete, the specific, we turn our backs on the pebble that is the subject of Herbert's splendid poem, his hymn to stony, serene, sovereign presence.

(....) ...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Pebble

Zbigniew Herbert

The pebble

is a perfect creature

equal to itself

mindful of its limits

filled exactly

with a pebbly meaning

with a scent that does not remind one of anything

does not frighten anything away does not arouse desire

its ardour and coldness

are just and full of dignity

I feel a heavy remorse

when I hold it in my hand

and its noble body

is permeated by false warmth

--Pebbles cannot be tamed

to the end they will look at us

with a calm and very clear eye

_______________________

Molloy sucking-stones

Samuel Beckett

(....)

There was something more than a principle I abandoned, when I

abandoned the equal distribution, it was a bodily need. But to suck

the stones in the way I have described, not haphazard, but with

method, was also I think a bodily need. Here then were two

incompatible bodily needs, at loggerheads. Such things happen. But

deep down I didn't give a tinker's curse about being off my

balance, dragged to the right hand and the left, backwards and

forewards. And deep down it was all the same to me whether I sucked

a different stone each time or always the same stone, until the end

of time. For they all tasted exactly the same. And if I had

collected sixteen, it was not in order to ballast myself in such and

such a way, or to suck them turn about, but simply to have a little

store, so as never to be without. But deep down I didn't give a

fiddler's curse about being without, when they were all gone they

would be all gone, I wouldn't be any the worse off, or hardly any.

And the solution to which I rallied in the end was to throw away all

the stones but one, which I kept now in one pocket, now in another,

and which of course I soon lost, or threw away, or gave away, or

swallowed ...

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

|