|

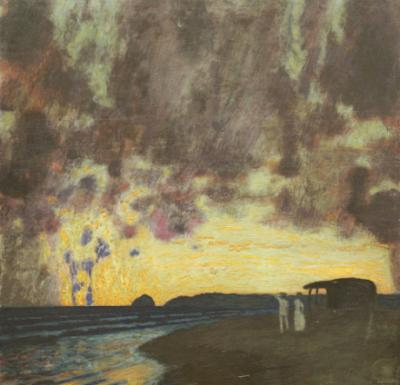

William Degouve de Nuncques

_______________________

Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene,

Chthulucene: Making Kin [pdf]

Donna Haraway

Environmental Humanities, vol. 6, 2015, pp. 159-165

There is no question that anthropogenic processes have had planetary effects, in inter/intra-

action with other processes and species, for as long as our species can be identified (a few tens

of thousand years); and agriculture has been huge (a few thousand years). Of course, from the

start the greatest planetary terraformers (and reformers) of all have been and still are bacteria

and their kin, also in inter/intra-action of myriad kinds (including with people and their

practices, technological and otherwise). The spread of seed-dispersing plants millions of years

before human agriculture was a planet-changing development, and so were many other

revolutionary evolutionary ecological developmental historical events.

People joined the bumptious fray early and dynamically, even before they/we were

critters who were later named Homo sapiens. But I think the issues about naming relevant to

the Anthropocene, Plantationocene, or Capitalocene have to do with scale, rate/speed,

synchronicity, and complexity. The constant question when considering systemic phenomena

has to be, when do changes in degree become changes in kind, and what are the effects of

bioculturally, biotechnically, biopolitically, historically situated people (not Man) relative to,

and combined with, the effects of other species assemblages and other biotic/abiotic forces?

No species, not even our own arrogant one pretending to be good individuals in so-called

modern Western scripts, acts alone; assemblages of organic species and of abiotic actors make

history, the evolutionary kind and the other kinds too.

But, is there an inflection point of consequence that changes the name of the “game” of

life on earth for everybody and everything? It's more than climate change; it's also

extraordinary burdens of toxic chemistry, mining, depletion of lakes and rivers under and

above ground, ecosystem simplification, vast genocides of people and other critters, etc, etc, in

systemically linked patterns that threaten major system collapse after major system collapse

after major system collapse. Recursion can be a drag.

(....) _______________________

"Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Staying with the Trouble"

Donna Haraway

vimeo

"Sympoiesis, not autopoiesis, threads the string figure game played by Terran critters. Always many-stranded, SF is spun from science fact, speculative fabulation, science fiction, and, in French, soin de ficelles (care of/for the threads). The sciences of the mid-20th-century “new evolutionary synthesis” shaped approaches to human-induced mass extinctions and reworldings later named the Anthropocene. Rooted in units and relations, especially competitive relations, these sciences have a hard time with three key biological domains: embryology and development, symbiosis and collaborative entanglements, and the vast worlds of microbes. Approaches tuned to “multi-species becoming with” better sustain us in staying with the trouble on Terra. An emerging “new new synthesis” in trans-disciplinary biologies and arts proposes string figures tying together human and nonhuman ecologies, evolution, development, history, technology, and more. Corals, microbes, robotic and fleshly geese, artists, and scientists are the dramatis personae in this talk’s SF game."

_______________________

La Jetée

Chris Marker

vimeo

_______________________

William Gibson on La Jetée

I first saw La Jetée in a film history course at the University of British Columbia, in the early 1970s. I imagine that I would have read about it earlier, in passing, in works about science fiction cinema, but I doubt I had much sense of what it might be. And indeed, nothing I had read or seen had prepared me for it. Or perhaps everything had, which is essentially the same thing.

I can't remember another single work of art ever having had that immediate and powerful an impact, which of course makes the experience quite impossible to describe. As I experienced it, I think, it drove me, as RD Laing had it, out of my wretched mind. I left the lecture hall where it had been screened in an altered state, profoundly alone. I do know that I knew immediately that my sense of what science fiction could be had been permanently altered.

Part of what I find remarkable about this memory today was the temporally hermetic nature of the experience. I saw it, yet was effectively unable to see it again. It would be over a decade before I would happen to see it again, on television, its screening a rare event. Seeing a short foreign film, then, could be the equivalent of seeing a UFO, the experience surviving only as memory. The world of cultural artefacts was only atemporal in theory then, not yet literally and instantly atemporal. Carrying the memory of that screening's intensity for a decade after has become a touchstone for me. What would have happened had I been able to rewind? Had been able to rent or otherwise access a copy? It was as though I had witnessed a Mystery, and I could only remember that when something finally moved – and I realised that I had been breathlessly watching a sequence of still images – I very nearly screamed.

_______________________

William Degouve de Nuncques

b. February 28, 1867

_______________________

Althusserians Anonymous (the relapse)

McKenzie Wark

I am a recovering Althusserian. For decades now I have been Althusser-free, for the most part, but we all have our lapses. The first step to becoming a recovering Althusserian is to recognize that you have no control and are unconsciously always a little bit Althusserian whether you want to be or not.

Louis Althusser is however not so much a poison as what Derrida and Stiegler and Stengers call a pharmakon. That is, something that is undecidable, both poison and cure. It may well be that there are good reasons, in the twenty-first century, to be an Althusserian. I am not objectively in a position to say, and in any case: by their results shall we judge them. When there is a useful Althusserian response to the Anthropocene (or whatever you want to call the current ‘conjuncture’) consider the matter settled. As of yet there is no such response, perhaps for reasons to be elucidated later.

Perhaps this is to judge too harshly. In what follows I want to read some essays by the ‘young Althusser’. I leave it to others to account for the mature works. I want to think about what is living and dead in the Althusserian ‘problematic’, through a series of antimonies that he had to face. ...(more)

_______________________

Félix Guattari: Thought, Friendship and Visionary

Cartography [pdf]

Franco Berardi (Bifo)

Translated and edited by

Giuseppina Mecchia and Charles J. Stivale

Ever since Félix Guattari died in 1992, I have been promising myself that I would write this book. But the book would never be finished, because rhizomatic thought is the cartography of landscapes yet to come, and so the landscapes in which this book proliferates have not ceased dispersing themselves before my eyes, with every passing day, faster than any light-speed writing. The development of the telecommunication network, biomechanical proliferation, the Genome Project, the constitution of a bioinformational paradigm, all are successive manifestations of this becoming rhizome of the world, of which Félix projected the earliest maps.

(....)

I don’t intend to summarize the contemporary success of DeleuzeGuattari thought. I simply want to tell my story, my encounter with this thought, and the perspectives that I see derived from it.

via —synthetic zero_______________________

Felix Guattari: The Schizo, the New Earth, and Subjectivation

S.C. Hickman

"From now on, no domain of opinion, thought, image, affect or narrativity can pretend to escape from the invasive grip of ‘computer-assisted’ data banks…"

-

Felix Guattari, Schizoanalytic Cartographies

“How should we talk today about the production of subjectivity?” asked Felix Guattari. Then he’d recognize the obvious: “A first observation leads us to recognize that the contents of subjectivity depend more and more on a multitude of machinic systems”. Ahead of his time, or just looking around and seeing what was already obvious, and yet bringing to the fore the hidden kernel of that ubiquitous world we now term the network society we’ve become.

I remember reading and rereading a particularly poignant section of Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia – that collaborative project of Deleuze and Guattari, two friends whose lives would be entwined. As Francois Dosse relates it in a biography of the two friends: Intersecting Lives, Deleuze and Guattari have described their work together on several occasions, but they did so somewhat discreetly. Describing their writing together when Anti-Oedipus first came out, Guattari remarked:

This collaboration is not the result of a simple meeting between two people. In addition to the particular circumstances leading up to it, there is also a political context. At the outset, it was less a matter of sharing a common understanding than sharing the sum of our uncertainties and even a certain discomfort and confusion with respect to the way that May 1968 had turned out.

Deleuze remarked:

As regards writing together, there was no particular difficulty and both of us realized slowly that this technique had some clear function. One of the very shocking aspects of books about psychiatry or psychoanalysis is their duality in the sense of what an ostensibly sick person says and what the healer says about the patient. . . . Curiously, however, we tried to get beyond this traditional duality because two of us were writing. Neither of us was the patient or the psychiatrist but we had to be both to establish a process. . . . That process is what we called the flux.

...(more)

_______________________

William Degouve de Nuncques

_______________________

George Quasha: from Alternate Lingualities (preverbs)

with a note on “Self-Organized Criticality”

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

(....)

2

spread

I’m revising my sense of beauty as we speak.

I write the line as if running out of ink.

It means the book means in flashes of the field, surrounded and self-erasing.

In the end nothing to rely on but a hunch.

The ego doesn’t die, it just fragments, pales, and multiplies.

It’s got craft if attachment releases without rejection of sensual texture.

You see it in deep cloud activity with your own eyes, not entirely yours.

My life or this dream may have matured to the point where I can say I drink dragons.

Running out of ink running out of my cave, all for love of cageless eggs and spread.

Order is performative.

It hits the spot.

The cloud is making offerings on my behalf which helps me across the bridge.

I can only say this due to the proto-allegorical tendencies of my life in footnotes.

Distraction is not knowing the speaking is going on without your apparent consent.

Duly noted and on foot as reflected by the page.

I get lost enough to let it show.

Notably: The greatest number of egos congregate where one has been annihilated.

This line of thinking accounts for my no count identity.

I grow less sure of one as a day ages.

...(more)

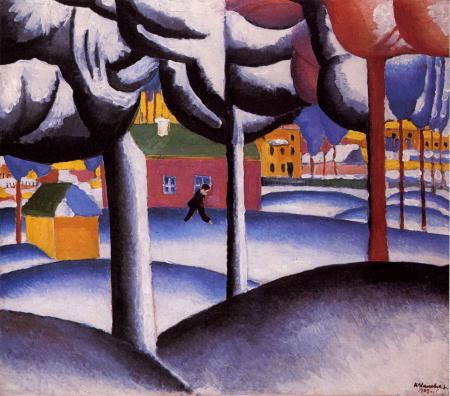

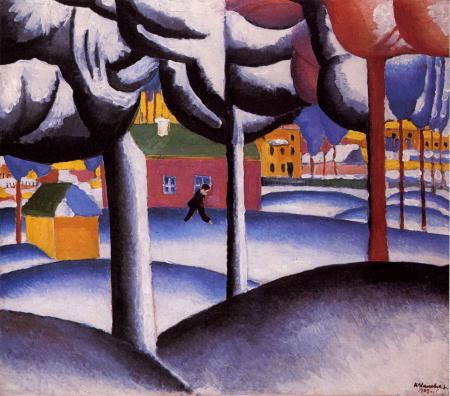

Winter Landscape

c.1930

Kasimir Malevich

1878 -1935

_______________________

Dana Gioia

_______________________

Writing, that powerful myth. The highest degree of distinction; how can it happen? How can the eye become progressively sensitive to reading, how can it get into the rhythm, the music; how can it be hurt – as if the light were bad – when a sentence doesn’t soar on strong wings? Nobody who emerges into the field of theory can do so without the soaring quill-feathers of writing. Althusser and his sentence about Mao Tse-Tung: ‘pure as the dawn’; Lévi-Strauss and his Latin prosopopoeia in all its imperial, Virgilian majesty. Lacan and his Greek, precious, baroque prosopopoeia. Derrida, or the transition to fiction. And a myriad of mediocre writings by junior masters diligently copying the rhetoric but without wings, serving up plucked chickens, birds with their breast-bones showing, naked animals.

–Catherine Clément (The Weary Sons of Freud, p. 46) reposted from an eudæmonist

_______________________

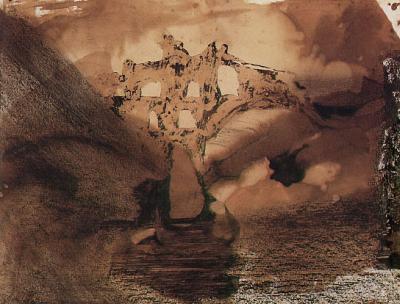

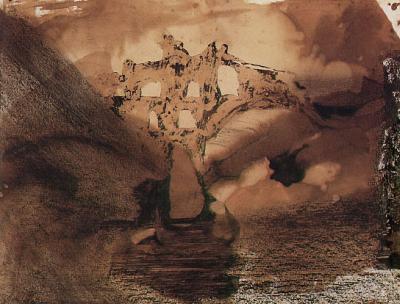

The key is here, the gate elsewhere

1871

Victor Hugo

b. February 26, 1802

_______________________

March/April issue of World Literature Today

We Were Born in the Houses of Storytellers

Ghassan Zaqtan

Translated by Sam Wilder

There is some cause for anxiety about the achievement accumulated by the last few generations of modern Arab poets, those dating back to around the middle of the last century. It is an anxiety that can only compound the mass of fears in face of so many losses on the ground—the withering of the social fabric, the erosion of an entire body of rights and truths produced through a long history of coexistence. It is an anxiety that is indeed wholly justified if we look to the facts on the ground and witness the transformations that have taken place, which have shifted a place and a people toward an other geography, an other history, an other culture. These transformations have been accompanied by an uprising called the “Arab Spring” and by the rise of “political Islam,” which includes among its numerous concomitants a discourse relying entirely on a Salafist vocabulary, drawing its proof-texts from a selective history shorn of all context and rendered blind through a violent process of negation and removal that combats the variety and differentiation of life and of daily values.

It is a discourse that emerges from the past and from loss, from the solemnity and silence of the past, from the bitterness and despair of defeat. It draws from this alone to produce its force and its power to convince and militarize.

It is a discourse that places the burden of the present and its losses squarely on the back of the “other,” the one who is different, a figure who hides around the corner setting his trap on our way home, defiling our pure garden and sending the children away from their family’s home.

A discourse that does not love poetry and does not trust poets.

This terror has left its mark on the poetry scene, whether in the summoning of ready-made methods from the past, or in the drawing of inspiration from the concepts of this discourse—its problems, language, and values—in what amounts to a “revival” movement that is wholly its opposite.

...(more)

via the Literary Saloon

_______________________

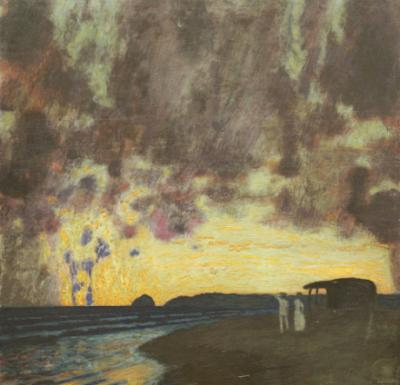

Evacuation of an island

Victor Hugo

1870

_______________________

Words

Dana Gioia

The world does not need words. It articulates itself

in sunlight, leaves, and shadows. The stones on the path

are no less real for lying uncatalogued and uncounted.

The fluent leaves speak only the dialect of pure being.

The kiss is still fully itself though no words were spoken.

And one word transforms it into something less or other--

illicit, chaste, perfunctory, conjugal, covert.

Even calling it a kiss betrays the fluster of hands

glancing the skin or gripping a shoulder, the slow

arching of neck or knee, the silent touching of tongues.

Yet the stones remain less real to those who cannot

name them, or read the mute syllables graven in silica.

To see a red stone is less than seeing it as jasper--

metamorphic quartz, cousin to the flint the Kiowa

carved as arrowheads. To name is to know and remember.

The sunlight needs no praise piercing the rainclouds,

painting the rocks and leaves with light, then dissolving

each lucent droplet back into the clouds that engendered it.

The daylight needs no praise, and so we praise it always--

greater than ourselves and all the airy words we summon.

Dana Gioia at the Poetry Foundation

_______________________

Ruined Aqueduct

Victor Hugo

1850

_______________________

Poems

Xu Lizhi

translated by Eleanor Goodman

China Labour Bulletin

I Swallowed an Iron Moon

I swallowed an iron moon

they called it a screw

I swallowed industrial wastewater and unemployment forms

bent over machines, our youth died young

I swallowed labor, I swallowed poverty

swallowed pedestrian bridges, swallowed this rusted-out life

I can’t swallow any more

everything I’ve swallowed roils up in my throat

I spread across my country

a poem of shame

...(more) via Jerome Rothenberg

photo - mw

_______________________

from “Thoreau”

Cole Swensen

In the essay “A Winter Walk,” which predated the more famous essay “Walking”

by a few years, Thoreau paid particular attention to the astonishing array of whites

from fog to snow to frost to the crystals growing outward on threads of light. The

fact that white is separately known. That it is its own wildness, entirely exterior,

like all weather you notice is a version of an open room coming through

the wind in prisms. White holds light in a suspended state, unleashing it later

across a field of snow or a sheet of water at just the right angle to make the surface

a solid, and on we go walking. Goethe’s Theory of Colors depicted each one

as an intense zone of human activity overflowing its object into feeling there is

a forest through which something white is flying through a wash of white, which is

the presence of all colors until red, for instance, is needed for a bird or green

for a world.

.....................................................

Timed instants

A review of Cole Swensen's 'Landscapes on a Train'

Jennifer K Dick

jacket2

I am on the TGV Lyria from Paris to Mulhouse reading Cole Swensen’s newest poetry collection, Landscapes on a Train. I am awash in “The infinite splitting of finite things”[1] as these one to five long-lined prose poems pass before my eyes with the rush and rumble of the train, the staccato catch and jostle of unexpected punctuation, the blur of the greens outside echoed in:

Green. Cut. And I count: the green of the lake the green of the sky and the field

Which is green and is breaking. (7)

Swensen’s anaphora is both visual and audible. The turning of the train’s wheels, the up-and-down of the hills, the words and end-stops, the rise and fall of gears and gaskets, noun and verb like metal pressing metal, run the train faster and faster through the landscape until outside is confounded and melds into such twinned, twined images as: “A / Train across open land opens night. (A train lands all night across an open field)” (11).

The first lines of Swensen’s book which I quoted above undercut potential casual normative prosy language with the delightful, surprising “is breaking” — so the field is splitting or else is rising up and breaking like a wave against the shores of our perception. It is the subtle crash of verbs and nouns in this book which undoes the potentially simple observations from a train and makes landscape, light, color, and language open themselves to new possibilities. Cause and effect skew, become the unexpected — so the train makes night open, or a train lands (like a plane or bird) but in a way that is ongoing, as “all night” in the second couplet quoted above suggests. We are “in a landscape almost held,” Swensen writes,“… By things that move / More slowly than trees” (13).

(....)

....This fragment indicates a time so slow our human eye cannot in a natural state notice the transformation, and yet trees grow and surround us. Trees in a state of emerging partake of how this book is about a landscape rising and falling — not just alongside some train on its singular journey but through all time, as Swensen indicates with “The light is an accident because the trees are old” (9). Here, the age of the trees and an accident of light are yoked together in a paradox of cause and effect, and of what can and cannot be perceived or known from a single train ride and rider in its passing. Things are lost or emerge over vast swaths of time along quickly perceived landscapes, as “There once was a church. There once was a steeple. These things fall into landscape” (17), or “One more house. Fallen down. Goes falling on” (20), or “And there goes a village of sand. Broke / The ruined ruin” (29) show. The green with which Swensen opens her book is a green being left, released to the air as she writes: “left sound, left the green alive / With houses, small, all stone and backing up on a green built of dust” (29).

...(more)

Cole Swensen, Landscapes On A Trainreview by rob mclennan (....)

An extended meditation constructed out of fifty-eight untitled, unnumbered prose-poems, each accumulated section of LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN suggest a series of quick notes composed during travel, capturing the details of landscape in the smallest brushstrokes, and held together to build into an essay on landscape and light around landscape painting during the Romantic (and even late Medieval) period.

Light slices across the tops of trees. White light cuts the presence back. The lack

Thereof. Light replaced. Light that is an approach. That we can’t see the light enter

The cells of the trees, not what leads, the path down to the cells below the trees.

...(more)

Cole Swensen at the Poetry Foundation and PennSound

Landscapes on a Train

Cole Swensen

amazon link

_______________________

Gustave Le Gray

_______________________

Moving Targets: On Writing and the New Realisms and Materialisms

Larval Subjects

(....)

I have often felt that this inability to stick with one philosophical scheme is a failure on my part. As an undergrad I had a curious fantasy. In Ohio State’s library, I noticed that a sort of archeology of books was possible. The books I would check out would be filled with underlining from a variety of different readers. It occurred to me that these different underlinings reflected different interpretations of one and the same text. I imagined writing a variety of articles on these books under pseudonyms based on these different underlinings, showing how books are holographic, capable of generating a variety of different readings. Each of these readings would be more or less well defended. How to decide between them? At the time I thought the decision was to be made at the level of the ethics and politics they each generated; at the level of practice.

I often feel as if it’s this way for me with philosophy. There is something holographic about the world, admitting of a variety of different theorizations or conceptualizations. Nonetheless, there is something compulsive in all of this for me, something superego. Maybe it’s among my symptoms in the proper Lacanian sense of the word. I could have gone on just fine after writing The Democracy of Objects, giving talks all over the world and writing endless articles recapitulating what I wrote to these various audiences. Yet whenever I sit down to write such things, whenever I resume, my superego screams at me, forbidding me from doing so, commanding me to go elsewhere, to think something other than I thought before. “Thou shall not repeat!”, it screams. Indeed, the moment I have written something it becomes shit for me, excrement, something that is dead.

...(more)

_______________________

Large Wave, Mediterranean Sea

Albumen print from two negatives

1857

Gustave Le Gray

1820 - 1884

_______________________

The lost hope of self-help

Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen

aeon

With metronomic regularity, new books about both the strange and the mundane things human beings do with metronomic regularity become bestsellers. The American ‘habit’ industry produces a huge popular literature examining how habits are formed and how they are broken, how they enable and how they hinder, and how they are a function of heroic self-discipline or a confession of its absence.

They maintain that people can cultivate not just a ‘learning habit’ but even an ‘achievement habit’. They suggest that ‘Jesus habits’ and ‘joy habits’ are liberating, but that the ‘worry habit’ is shackling. ‘Habits not diets’ are the best way to free the self from the siren call of the refrigerator.

(....)

As ever, the habits literature of today promises order in a disordered world, but it also comes with a subtle and significant difference. The most important difference is not the forgotten art of style, though the staccato prose, exclamation points, bland generalisations, and clichéd motivational quotations of today’s literature neither stimulate the imagination nor activate the will. Rather, it is the lost promise of habits literature as a form of ethical inquiry and social commentary. Individual improvement has always been the purpose of habits literature, but the genre used to require appraising the society in which the self, and the habits, formed. Historically, thinking about habits without social contexts or ethical consequences was unthinkable. Today it is axiomatic.

...(more)

Paris, neige au Champs de Mars

Henri Le Secq

1818–1882

_______________________

the novelist as failure, the language as failing: a recursive reading of melville’s pierre

Grant Maierhofer

3am

“His time of thought was brief. Rising from his bed, he steadied himself a moment; and then going to his writing-desk, in a few at first faltering, but at length unflagging lines, traced the following note:”

Pierre; Or the Ambiguities

“But of all the books brought back by supplemental boosting, none, surely, are more unlikely than Herman Melville’s “Pierre; Or the Ambiguities.” The author of “Pierre,” vastly unpopular in his early career, flirted with the temptations of a non- or anti-popular mode of writing when he came to the fullness of his ambition. A year before starting “Moby-Dick,” Melville wrote to his father-in-law, ‘So far as I am individually concerned, & independent of my pocket, it is my earnest desire to write those sort of books which are said to ‘fail.’’ But “Pierre” failed beyond Melville’s wildest dreams. This is arguably the least read work a major author ever wrote.”

The Book that Ruined Melville, Richard H. Brodhead

When attempting to elaborate either a reading or thesis-based-upon an apparently lesser, or minor text of a given, major author, the temptation is immediately to declare its obvious status as a masterpiece overlooked, and to base one’s reading/thesis muddle in this hyperbole to act as an excavator amid the ruins of literature. This is a possible, initial temptation, anyway; but typically proves inept. In approaching Melville, one can see this enacted in critical blips here and there, or in the tendency of contemporary publishers to unearth obscure late-era texts ceremoniously; and while this has its place—the marketplace, logically, a notion to which Melville was no stranger—it frequently elides critical rigor and—though doubtless bolstering sales—does little to deepen, or widen understandings of a given scrivener’s work. Melville himself is touchy because as curious readers in the twenty-first century we already rely upon several waves of unearthings just to read his works and their grand accompaniments. Without this sense of rediscovery amid the ruins would Norton even nod the time of day at Moby-Dick? Perhaps not, and thus scholars-as-archaeologists will always have their place, but as the dust clears our given wave is tasked in many cases with simply resorting to reading (newly, closely) to perpetuate and revivify these works; a simultaneous shrug and call to arms, as it were—at least that’s been my own attempted take on matters.

...(more)

_______________________

strayed

1891

Franz Stuck

b. February 23, 1863

_______________________

A Moment Knows

Jane Hirshfield

A moment knows itself penultimate—

usable, spendable,

good yet, but only for reckoning up.

A moment knows something’s almost over,

but not what that is.

There is still time, the day sings its old round, time still is here,

though you can’t hear

the new thing arriving inside the knots of its ticking,

though you can’t feel the brush of its wing

on the nape of your life,

or hope for the voice

to arrive, as it has always, saying,

“Come, I’ve returned to you, here is your gift.”

...(more)

Jane Hirshfield at the Poetry Foundatiion

_______________________

The Lives of the Translators: the Whence and the How

Josh Billings

asymptote

(....)

For Willa and Edwin Muir, the Scottish couple whose translations of Franz Kafka, Hermann Broch and many others introduced English-language readers to some of the greatest German modernists, translation was a gift and a curse. On the one hand, it offered them money and a sense of accomplishment; on the other, it encroached on the writing that both of them, at different points in their lives, considered a true calling. But no matter how they thought about it, translation remained a means of survival for the couple: a lifeboat in which they bobbed, happily or at odds, through some of the most treacherous waters of the 20th century.

(....)

Translating Kafka gave Edwin a key to understanding his own troubled history; at the same time, it served as a bridge between that history and the evolving horror of the 20th century. For Willa, on the other hand, the extraordinary thing about The Castle was less the philosophy that could be abstracted from it than the passageway it carved into her consciousness, or even further: to the grotto-like underworld of her dreams. Later in life, she tried to explain this difference between her and Edwin’s readings as a further example of his preference for “Whence,” over hers for “How”. “Edwin tried to divine and follow up the metaphysics of Kafka’s vision of the universe,” she wrote, “While I stayed lost in admiration of the sureness with which he embodied in concrete situations the emotional predicaments he wanted to convey, situations that seemed to me to come clean out of the unconscious, perhaps directly from actual dreams.”

...(more)

_______________________

Franz Stuck

_______________________

On reading Christian Bök's 'The Xenotext: Book 1' ten thousand years later

A xenoreview

Joshua Schuster

jacket2

(....)... I did not know that Bök would not tell in this work the lengths he has gone to strive for this project and the success and failures encountered along the way. All along it was understood that the poem was not going to be the verbal icon, and not the book either, but the work of the poem in its trying to get made. Poeisis included: all the computer programming, grant writing, art exhibits, promotional tweets, interviews, preposterous claims, raised eyebrows, and bioethical murmurings. The poem project also involved aiming to survive at least ten thousand years later with enough of these subroutines still running to keep the poem’s grammar warm and agential.

It is strange then that most of that work on the bioart poem goes unmentioned in Book 1. Instead, the book consists of five sections containing a mix of prose and poetry, whose form and content are structured in varying degrees by some aspects of genomics. There is also a “vita explicata” where Bök details his methods and states that he sees Book 1 as “an ‘infernal grimoire,’ introducing readers to the concepts for this experiment” (151). With the genome as muse and medium, this is really a DNA text. The book fits somewhere in the early twenty-first century between J. Craig Venter’s genome cowboying and GMO redemption rhetoric and Donna Haraway’s accusatory “fetishism of the gene,” the feminist eco-technoscience-inspired rejection of masculinized selfish genes and synthetic genome rescue operations in favor of a decentered, pluralized, and environmentally embedded sense of coming to know what genotypes and phenotypes can do.

(....)

Bök seeks to collaborate with the genome, writing along with it rather than through and over it. Many of the poems in the book take on the visual and organizational feel of nucleic material. Writing with the genome requires working with its generative and generational properties that occur at micro and macro scales. Bök’s project embraced writing with biological longevity and epochal time frames as enabling constraints. How do you write and read for (at least) a ten-thousand-year time span? There are clocks made to keep time for ten thousand years, and writings inscribed on tombs for radioactive nuclear waste meant for any possible reader who might stumble upon such a toxic archive. There are epic poems that believed themselves to be immortal and unforgettable and are long lost, while a fragment of an exchange of glances caught in Sappho’s scroll — “for when I look at you, even a moment, no speaking is left in me” — still carries an erotic charge thousands of years later. Although Bök has sometimes claimed he aimed to write a poem that would effectively become immortal, the writing of poetry has never been about striving for one temporality or one version of longevity.

...(more)

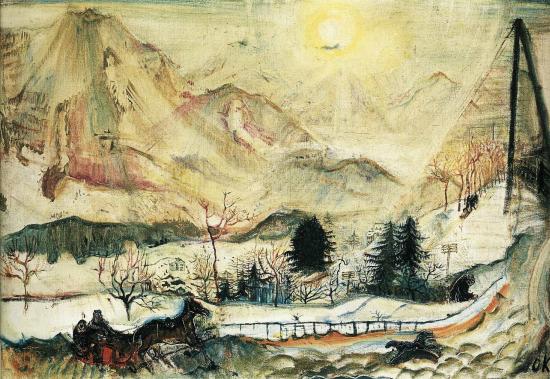

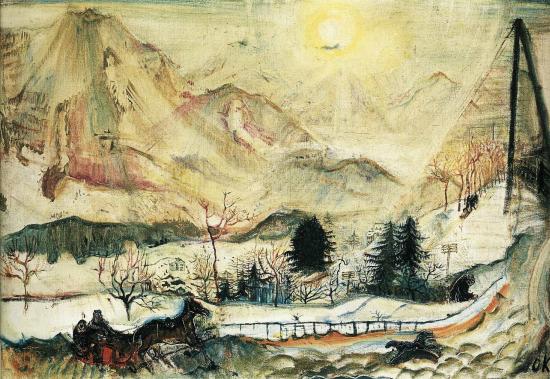

Dent du Midi

Oskar Kokoschka

d. February 22, 1980

_______________________

from “Further Autovariations,” Three Poems, 2016

Jerome Rothenberg

1/

the poem as landscape

the definition

of a place

is more than

what was seen

or what was

felt before

when dreaming

of the dead

the way

a conflagration

wrapped itself

around his world

leaving in his mind

a trace of dunes

the fallout from

a ring of mountains

reminders

of a vanished earth

the landscape

marked with rising tufts

the hardness of

clay tiles

that press against

our feet like bricks

the soil concealed

beneath its coverings

through which a weave

of twisted wires

crisscross the empty

field as markers

to commemorate

the hapless dead

the ones who fly

around like ghosts

...(more)

_______________________

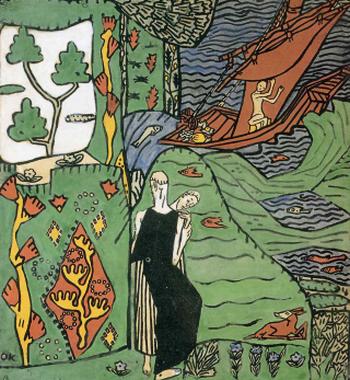

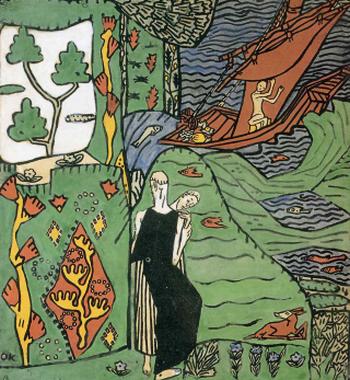

Orpheus and Euridice

Oskar Kokoschka

1917

_______________________

Second Acts:

A Second Look at Second Books of Poetry by Rae Armantrout and Ye Chun

Lisa Russ Spaar on Lantern Puzzle and The Invention of Hunger

l.a. review

(....)

I admire in Armantrout’s work much of what I prize in Dickinson — surprising, destabilizing diction; slippage of scale and person; paratactic daring; a fierce, riddling intelligence that is at once utterly clear and intricately obdurate; a mix of abstraction and image, of seriousness and humor, of discourses and contexts, particularly the scientific and the quotidian; an awareness of words; and a provocative, stereoscopic obsession with story and fiction that resists neat resolution. Because I am best acquainted with Armantrout’s relatively recent work, I was eager, for this series pairing a second book of poetry written over 20 years ago with a recently published second poetry collection, to locate Armantrout’s first two books, and to take a special look into the second to see something of the roots of this remarkable writer, who is associated with the L-A-N-G-U-A-G-E poets, but who also, like any original artist allied with any school or group, is very much her own stylist.

(....)

Like Armantrout, poet and novelist Ye Chun, whose second book of poems, Lantern Puzzle, appeared a few months ago from Tupelo Press, is a potent minimalist. Though perhaps a more recognizably lyric poet than Armantrout (Armantrout “belongs to what might be characterized as the literature of the vertical anti-lyric, those poems that at first glance appear contained and perhaps even simple,” Silliman writes, “but which upon the slightest examination rapidly provoke a sort of vertigo effect as element after element begins to spin wildly toward more radical ... possibilities”), Ye shares with Armantrout a gift for compressing into small spaces a prodigious and fluid range of at times seemingly unconnected and suggestive perceptions in a manner that becomes emblematic of inner questioning, desire, and a restless, travelling gnosis.

...(more)

_______________________

Oskar Kokoschka

_______________________

Elegy w/ Surrealist Proverbs as Refrain

Dana Gioia

“Poetry must lead somewhere,” declared Breton.

He carried a rose inside his coat each day

to give a beautiful stranger—“Better to die of love

than love without regret.” And those who loved him

soon learned regret. “The simplest surreal act

is running through the street with a revolver

firing at random.” Old and famous, he seemed démodé.

There is always a skeleton on the buffet.

Wounded Apollinaire wore a small steel plate

inserted in his skull. “I so loved art,” he smiled,

“I joined the artillery.” His friends were asked to wait

while his widow laid a crucifix across his chest.

Picasso hated death. The funeral left him so distressed

he painted a self-portrait. “It’s always other people,”

remarked Duchamp, “who do the dying.”

I came. I sat down. I went away.

...(more)

Dana Gioia at the Poetry Foundation

_______________________

The Sailboat

Oskar Kokoschka

_______________________

poor quartets

Dominic Jaeckle reviews Thomas Bernhard, Goethe Dies, translated by James Reidel

3am

Goethe Dies, a collection of short pieces initially published in German periodicals in the early 1980s, goes some way to frame its author’s relationship with the negative romance of a running order. Although pegged in a period pushed along by the booming influence of mass media, Thomas Bernhard’s insistence seems be constantly on looking backwards. For Bernhard, retrospection and nostalgia are tools to play with history – to upset the performance of culture’s chronology. Retrospect and nostalgia illogically amass as a personality, a name comprised of each of its unique memorial moments as componential. But memory is selective, elective and misleading. The voice in Bernhard’s prose always recognises the importance of a given moment, but the mass of moments cannot be ordered properly or coherently – their collation cannot do anything to justify the composed chaos of the contemporary instant. It cannot do anything to evade the determinate, plotted points of life that have lead up to our imprisonment in a heavy “now.” Bernhard rails against that now, but only in the knowledge that argument is acknowledgement – any anger with the present tense acknowledges the prior moment that initiates it; objectifying it through verbal action, through immediate response, making a parody of the past. This engenders a load-bearing melancholia that’ll reoccur as the keystone to each of his works, but more importantly Bernhard needs to remind us again and again that this is funny. Time has a sense of humor; it just scarcely carries the tenacity of a punchline. He’s ironised the very idea of an author’s collected stories before we even get here; he’s perverted the need to structure words on paper before we arrive at the thought he is scaffolding.

That’s true wherever the finger lands when gliding over any book in his oeuvre, but is central to a reading of Goethe Dies. ...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

The Anthropocene: Platonov and the Tragedy of the Commons

S.C. Hickman

McKenzie Wark in his latest work Molecular Red: A Theory for the Anthropocene tells us that the Anthropocene is a “catalog of the reasons why the ever-expanding commodifcation of everything is on a collision course with planetary limits”.1 Of all the authors he explicates it is Andrey Platonov as Wark reminds us who has a masterful intuition of what the Anthropocene future is going to be like. (Wark, p. 31) He’ll provide a short story of Platonov’s On the First Socialist Tragedy (translated by Tony Wood) as an opening toward a series of meditations of the impact of humans in the era of the Anthropocene. The Guardian talking of Robert Chandler’s translation of The Foundation Pit would say of Platonov that Stalin called him scum. Sholokov, Gorky, Pasternak, and Bulgakov all thought he was the bee’s knees. But when Andrey Platonov died in poverty, misery and obscurity in 1951, no one would have predicted that within half a century he would be a contender for the title as Russia’s greatest 20th-century prose stylist.

(....)We’ve entered the pit too far now, and the earth is at war with humanity, the balance has been upended and as climatologists tell us over and over we are facing a vast array of insurmountable obstacles in the coming century and centuries. We’ve been told by environmentalists for sixty years that we need to begin doing somethin to curtail our impact or face extinction as a species along with most of the biosphere itself. As of yet most of our political measures have been little more than fictional agreements to placate media and the elite rulers of finance, and governmental regulation and control. For the rest of us the truth is much grimmer, the truth is that the future is a bleak zone of waste, decay, and bare and futile existence. Why? Because our impact has already started processes that have become autonomous and independent of humanity, both technological and natural.

...(more)

_______________________

Rearmament

Robinson Jeffers, 1935

These grand and fatal movements toward death: the grandeur of the mass

Makes pity a fool, the tearing pity

For the atoms of the mass, the persons, the victims, makes it seem monstrous

To admire the tragic beauty they build.

It is beautiful as a river flowing or a slowly gathering

Glacier on a high mountain rock-face,

Bound to plow down a forest, or as frost in November,

The gold and flaming death-dance for leaves,

Or a girl in the night of her spent maidenhood, bleeding and kissing.

I would burn my right hand in a slow fire

To change the future … I should do foolishly. The beauty of modern

Man is not in the persons but in the

Disastrous rhythm, the heavy and mobile masses, the dance of the

Dream-led masses down the dark mountain.

.....................................................

Tatterdemalion

Sylvia Linsteadt

For look, the whole is infinitely newer

than a cable or a high apartment house.

The stars keep blazing with an ancient fire

and all the more recent fires will fade out.

Not even the largest, strongest of transmissions

can turn the wheels from what will be.

Across the moment, aeons speak with aeons.

— Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus

(....)

Robinson Jeffers said it a little bit differently than Rilke, but I think both men meant something similar. ‘I would burn my right hand in a slow fire/ To change the future… I should do foolishly’ wrote Jeffers in his ‘Rearmament’ (revisit the whole piece in the Dark Mountain Manifesto). Rilke is a little bit more hopeful, seeing our hasty and foolhardy fires ultimately burning out in the face of stars and aeons: ‘Not even the largest, strongest of transmissions/ can turn the wheels from what will be.’ We are hurtling toward something dark, but none of us can quite say what or when or where. Both Rilke and Jeffers would have us look to stones and stars to remember the great spans of trans-human time; to re-work the stories we tell ourselves so that they honour the vaster, slower things of the cosmos, and therefore help us weather great change. Wherever it is we find ourselves, now and down the road, we will need stories full of spider-threads and planets alike, to keep our hearts and our spirits whole.

...(more)

The Dark Mountain Project

_______________________

Le culte

1942

Louis Soutter

d. February 20, 1942

_______________________

Conversion Disorder

Jamieson Webster

public seminar

I wonder if “conversion disorder” — a classical psychiatric term for the conversion of psyche into soma in the form of psychosomatic issues — could be one way of thinking about the present. Especially with so many patients complaining of bodily symptoms, armed at times with cadres of healers; with so many seeking recourse to pharmacological treatments or bodily modification of various sorts, plastic and otherwise; with young men and women seemingly willing to direct violence at any-body, including themselves, in the name of powerful religious ideals. Something increasingly insists on the level of the body.

There are even times when I feel like we are living in the nineteenth century. The fads for body-based healing reminiscent of an age of sanatoriums and hydrotherapy in Europe and the global pull toward religious fundamentalism akin to the intensity of something like the burned-over district of western New York. In fact, the metaphor of burned-over feels apt, meaning that there is no fuel left to burn, everything having been converted — a nod to the chemical meaning of conversion as instantaneous and complete transformation.

Conversion disorder is a late-nineteenth century term originally fastened to hysteria, a term taken from the Greeks to denote bodily symptoms, mostly feminine, that were medically inexplicable and so linked to psyche more generally. Hysteria eventually disappears from the medical lexicon in the 1980s, marking the centennial anniversary of psychoanalysis with its absence. Conversion, however, remains. Ambiguous. More gender-neutral. Less arduous of a term than “conversion hysteria,” but one that still speaks to the problem of the relationship between body and mind — all those puzzling aches and pains that seem to come with anxiety or depression, that act like a constant companion of sorts, or, on the more extreme end, problems like hypertension and colonitis, and the more ambiguous diseases like auto-immune issues or the chronics of Lyme, pain, and fatigue. Conversion disorder carries within itself the failure of diagnosis mapping so many bodily issues that seem to follow the fault lines of culture.

...(more)

_______________________

Lucien Pissarro

b. February 20, 1863

Chemin enneigé

c. 1930

Léonard Misonne

1870 - 1943

_______________________

Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? [pdf]

Jean Baudrillard

Translated by Chris Turner

With Images by Alain Willaume

When I speak of time, it is not yet

When I speak of a place, it has disappeared

When I speak of a man, he's already dead

When I speak of time, it already is no more

LET US SPEAK, then, of the world from which human beings have disappeared.

It's a question of disappearance, not exhaus- tion, extinction or extermination. The exhaustion of resources, the extinction of species-these are physical processes or natural phenomena.

And that's the whole difference. The human species is doubtless the only one to have invented a specific mode of disappearance that has noth- ing to do with Nature's law. Perhaps even an art of disappearance.

LET'S BEGIN WITH the disappearance of the real. .......

_______________________

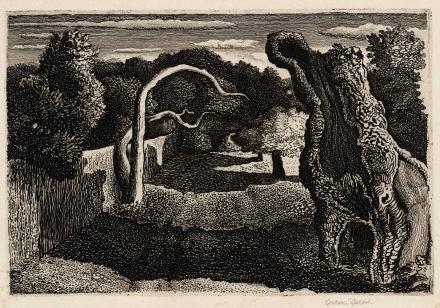

Sketch for Pastoral

1930

Graham Sutherland

1903–1980

_______________________

The Poetry of Osip Mandelstam: A Radio Play by Paul Celan (complete)

Translated from Celan's German by Pierre Joris

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

(....)

1. Speaker: The twenty poems from the volume “The Stone” strike one as strange. They are not “word-music,” they are not impressionistic “mood poetry” woven together from “timbres,” no “second” reality symbolically inflating the real. Their images resist the concept of the metaphor and the emblem; their character is phenomenal. These verses, contrary to Futurism’s simultaneous expansion, are free of neologisms, word-concretions, word-destructions; they are not a new “expressive” art.

The poem in this case is the poem of the one who knows that he is speaking under the clinamen of his existence, that the language of his poem is neither “analogy” nor plain language, but language “actualized,” voiceful and voiceless simultaneously, set free under the sign of an indeed radical individuation which, however and at the same time, remains mindful of the limits imposed on it by language and of the possibilities language has opened up.

The place of the poem is a human place, “a place in the cosmos”, yes, but here, down here, in time. The poem – with all its horizons – remains a sublunar, terrestrial, creaturely phenomenon. It is the language of a singular being that has taken on form; it has objectivity and oppositeness, substance and presence. It stands into time.

...(more)

_______________________

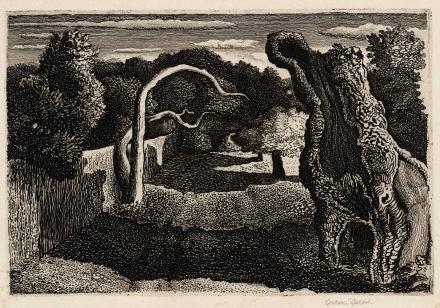

Thorn Tree

Graham Sutherland

c.1945

_______________________

Posthumanism in Literature and Ecocriticism

Serenella Iovino

“Where does the posthuman dwell? At what address? And in what type of house?”

These questions, borrowed from the opening of Deborah Amberson and Elena Past’s essay on “Gadda’s Pasticciaccio and the Knotted Posthuman Household,” tickle our eco -accustomed ears—ears that more often than not like to take ideas back to their earthly dwelling, something that the Greek all-too famously called oikos . In our case, however, to provide the right answer to these questions is definitely challenging and might require a little “veering.” The reason is simple: situated by definition in a mobile space of matter and meanings, the posthuman does not seem so prone to dwell . In fact, it moves, relentlessly shifting the boundaries of being and things, of ontology, epistemology, and even politics. And these boundaries, especially those between human and nonhuman, are not only shifting but also porous: based on the—biological, cultural, structural—combination of agencies flowing from, through, and alongside the human, the posthuman discloses a dimension in which “we” and “they” are caught together in an ontological dance whose choreography follows patterns of irredeemable hybridization and stubborn entanglement. In this mobile and uncertain dwelling, furthermore, the posthuman might not have a stable “address,” but it does address important issues: it addresses, for example, the alleged self-sufficiency of the human, the purported subsidiarity of the nonhuman, and the consistency of categorical essences and forms that hover over our visions and practices as if they had been demarcated ab aeterno by the hand of an inflexible taxonomist. Taking a closer look, finally, we can see that the posthuman’s house is not only mobile and a bit shambolic, but also operationally open: open to transformations and revolutions, ready to welcome the natures, matters, and cultural agents that determine the existence of the human and accompany it in its biological and historical adventures. It is a collective house for “nomadic” comings and goings, and most of all for belonging-together and multiple becomings: its inhabitant and “name-bearer,” the posthuman subject is, in fact, “a relational subject constituted in and by multiplicity”—a subject “based on a strong sense of collectivity, relationality and hence community building,” as Rosi Braidotti says in her beautiful interview with Cosetta Veronese. In other words, as its house is itinerant and accessible to numerous guests, including the elements, the posthuman subject is a restless and sociable agent, allergic to limitations and boundaries, and ontologically full of stories. A biocultural Picaro, one might say.

_______________________

Pastoral

Graham Sutherland

1930

_______________________

Fantasies of the Autobiographical Self: [pdf]

Thomas Bernhard, Raymond Federman, Samuel Beckett

Alfred Hornung

The recent increase of writings in the autobiographical mode seems to represent both a reaction to the so-called crisis of the novel and a possible artistic solution to the fragmentary nature of human experience. Yet at the same time the autobiographical turn reveals the paradox inherent in this form insofar as it reflects a nostalgia for stability and continuity as well as its constant denial in life. If conventional autobiographies could be regarded as the proper medium for the realistic representation of a self and for the narrative recovery of past events from the perspective of the present, contemporary autobiographical texts stress the illusory nature of such mythopoeic endeavours. Due to the breakdown of a clear demarcation between reality and fiction or reality and imagination, the traditional conception of the autobiographical genre has lost its degree of certainty and truth. Thus Frederick Exley admits in his autobiography, A Fan’s Notes, that he has “drawn freely from the Imagination and adhered only loosely to the pattern of my [his] past life” and asks “to be judged as a writer of fantasy.” This intrusion of fantasy into reality has equally affected the constitutive parts of autobiographical texts: the representation of a world, the recollection and narration of past experiences and the concept of the self. The recent autobiographical writings of Thomas Bernhard, Raymond Federman and Samuel Beckett elucidate the paradox of the autobiographical form, i.e., its nostalgia for and its denial of coherence, which correspond to the paradox of modern experience, the nostalgia for a lost presence.

Although Bernhard, Federman and Beckett are known individually, it might be worthwhile to

point out their interconnections, which eventually will permit us to speak of a common

autobiographical trend in contemporary American and European fiction. ..... _______________________

Conceptual writing (plural and global) and other cultural productions

Edited by Divya Victor

jacket2

This feature on Conceptual writing collects thirty-five responses from a wide group of practitioners and critics of diverse method, intent, and position, who responded to Divya Victor’s 2015 call for writing: 1) To expand the field of critical influences and frame its discourses through the lenses of anti-imperialism, postcolonialism, spirituality studies, disability studies, ecocriticism, and critical race theory; 2) To create records of aesthetic and political genealogies which resonate as true and lived for practitioners; and 3) To articulate the critique of dominant and hegemonic genealogies or histories associated with contemporary conceptual and conceptual-like writing.

Preface Divya Victor

Over the past year, many of us have written into, thought through, lashed out against, and endured polarizing discourses about North American and transnational poetics. Some of us have participated in these discussions carrying flags of myriad colors, some have been dragged through unwillingly, some have watched from the sidelines anxiously wringing hands or studiously taking notes. These discourses have polarized writers and critics on aesthetics, ethics, and politics, sometimes producing useful questions about the intersections between these realms, sometimes enforcing reductive homologies between them. While polarity has often characterized these discourses, it is hard to pin down even contingent names for the resulting dichotomies: Conceptual Writing vs. Lyric Poetry? Conceptual Writing vs. Political Poetry? Conceptual Writing vs. Positivist Representation? Avant Garde Aesthetics vs. Activist Poetics? To speak in the idiom of Maestro Ilayaraaja, my muse while I edited this feature: How to name it? How to, indeed?

...(more)

John Aldridge

1905 - 1983

_______________________

Song of Inexperience

Vivian Gornick revisits Howards End

(....)

Anxiety — that frozen sea within — still made it impossible for him to dive deep into the kind of desire that leads to self-knowledge; and without self-knowledge all remains murk and isolation. It was this sense of frozen solitariness, I now realized, that had colored all of Forster’s thought and feeling, and in time supplied him his signature concern: “Only connect!” Rereading “Howards End,” it was now easy to see that it is the writer’s own arrested development that haunts Forster’s work, and that which makes it moving.

“Howards End” is the most compromised of all Forster’s novels because its plot is the most fantasy-ridden; at the same time it is the book that most nakedly reveals his creative dilemma. Unable to achieve emotional experience himself, yet impelled to write about it, he here adopts the intellectually intelligent voice of a writer who senses the import of what lies behind the tragedy of life but doesn’t really know what he’s talking about — and he doesn’t know what he’s talking about because he cannot speak in the voice that would deliver truth to the reader a hundred years down the road: that of a man whose time and place has terrorized him into picking up a pen forever dipped in code.

...(more)

_______________________

Finnish vispo: Kokoomateos

Edited by Nico Vassilakis

jacket2

Nico Vassilakis returns to Jacket2 with a new feature on the current state of visual poetry in Finland. “There’s a stir going on, a textual free-for-all, a visible shift in how language is being handled in response to the machines in our lives,” he notes. “In Finland, visual poetry, in some way, sprang up almost fully formed. There are few antecedents that point to its appearance, yet here it is. The fully mature mingle with the nascent and in so doing form a new constellation of visual poetries.”

The ten poets included here — Cia Rinne, J. P. Sipilä, Jukka-Pekka Kervinen, Mari Laaksonen, Mikko Kuorinki, Reijo Valta, Sami Liuhto, Satu Kaikkonen, Tero Hannula, and Tiina Lehikoinen — reflect the potential of a close-knit Finnish scene, yet find diverse solutions to their own aesthetic dilemmas, producing “strong, flexible, and stunning work” in the process. In Vassilakis’ estimation, they’ve created “a visual poetry platform from which future poets can embark on a Finnish vispo experience.”

_______________________

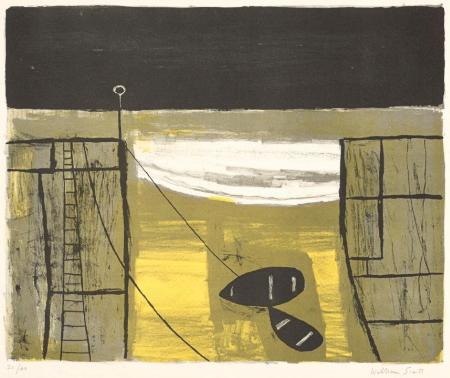

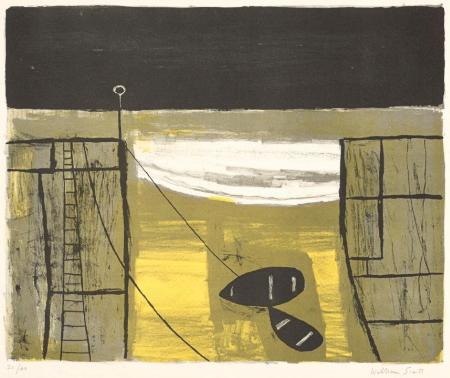

still lilfe

William Scott

1913-1989

_______________________

The Interview: C.K. Williams In conversation with Ahren Warner – an excerpt

(....)

I’m not actively interested in psychoanalysis anymore but it’s so much a part of the structure of my mind now, of the nomenclature of my mind, that I don’t have to think about it. It’s interesting – after all the study I did and all the reading I’ve done about psychoanalysis – the great presentation of psychoanalysis is still ‘In Memory of Sigmund Freud’, which is one of the incredible poems of the twentieth century. There are still people who will say “Freud was right, Freud was wrong…” – it doesn’t make any difference. He made these discoveries about consciousness, not all of them were right but many of them in their basic configurations are undeniable. The fact that there is something like a subconscious that makes you think things, that makes you say “Why did I think that?”. The work with kids I did was group therapy and I did it with a brilliant therapist who is still a good friend. And there were kids, you know, from… I guess the youngest might have been fourteen but they were mostly in their middle to late adolescence, sometimes up to twenty-five or thirty. And I guess the effect of it was mostly that you didn’t have to be afraid of anything that the mind does. Even though you can be thunderstruck at it, at its absurdity and sometimes obscenity, there really wasn’t anything to be afraid of. And I think that may have helped me write some poems that I might not have been able to write otherwise. Just that, being able to say “Oh, look, this is what mind does. And so what? Let’s think about it or talk about it or write about it.” If I got anything from that work, it would have been that. Although there were scary things too: kids trying to kill themselves, and sometimes succeeding. But basically it was that: realising how many different things consciousness can do, and how forgivable almost all of it is.

...(more)

via The Page_______________________

William Scott

_______________________

Introduction to « Anthologie Poésie Internationale »

Pierre Joris

1987

The only absolutes for poetry are diversity & change (& the freedom to pursue these); & the only purpose, over the long run, is to raise questions, to raise doubts, to put people into alternative, sometimes uncomfortable situations, to raise questions but not necessarily answer them, or to jump ahead with other questions, to challenge the most widely held of preconceptions in our culture, that “Western man” is the culmination of the human evolutionary process.

Jerome Rothenberg

As this century winds down it is becoming increasingly clear that poetry may well constitute the single area of literary endeavor that has managed to renew itself & widen its scope enough to accommodate our various new knowledges & perceptions; to embrace & honor a poesis of human vision going all the way back to the Paleolithic & still actively alive among the so-called primitive peoples of the earth; to open new areas of consciousness for investigation, and to create the tools that should make it open-ended enough to prevent closure and paralysis.

Relieved by the rise of the novel over the last 2 or 3 centuries of the burden of upholding & perpetuating the accepted imago mundi of repeating & banging home the doxa, the norm, political, moral & aesthetic, the powers that be want to impose as social & artistic orthodoxy, poetry has found itself more & more in the margins of the literary arena, & has found there an exhilarating freedom to breathe, and renew itself.

...(more)

_______________________

Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation: Hermeneutics, Aesthetics, Politics

Jesse S. Cohn

(....)I, too, contend that anarchism has something to contribute to projects that seek a way out of contemporary impasses in hermeneutics, aesthetics, and politics. However, when we look for this contribution, we will find that it is something more and other than mere antirepresentationalism. In fact, a care- ful rereading of the tradition will take us beyond the sterile opposition be- tween an unsupportable ‘‘representationalist’’ position and an incoherent ‘‘antirepresentationalist’’ one. It will require us to rethink the very premises that have premised the crisis, including such key concepts as essentialism, agency, construction, determination, and the subject.

It will also require us to dissolve some popular and academic misinterpre- tations of anarchism. Despite some rather unhistorical Marxist claims to the contrary, anarchism is also a socialism. ...(more)

_______________________

(foothills, Cumberland)

1928

Ben Nicholson

1894-1982

_______________________

Fantasy North

E R Truitt

aeon

The night sky pulses with colour: streaks of viridian, azure, violet and crimson vivid against the bleached land. Leviathans roam the seas, singing in haunting voices, and white bears hunt toothed whales on land and water. Giants make their homes in the mountains; elves and trolls live among the rocks. Half the year is spent in darkness and perishing cold, bleak and treacherous, the other half in sunlight and warmth, the landscape lush and verdant. Here is a portal to another world. The tribal inhabitants, some more animal than human, live in harmony with their harsh environment, bridle at outside authority, and fight with terrible ferocity. You know this place well. It is the Fantasy North.

You have spent quite a bit of time here over the past few years, perhaps even without trying. ...

(....)

What is it about the current era that draws our gaze towards the top of the globe? Where does our fascination with ‘northernness’ come from? Within Western culture, the North has long been both an imaginary realm and a geographic place. Since the ancient period, it has been a land at the edge of the world, one that exists on its own terms and as a scrim for various fantasies. Many of those fantasies have been preserved intact, in a sort of cultural permafrost that keeps our interest in the North evergreen. But every so often, something stirs.

...(more)

|