|

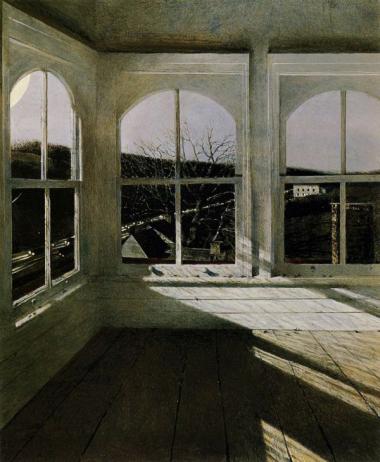

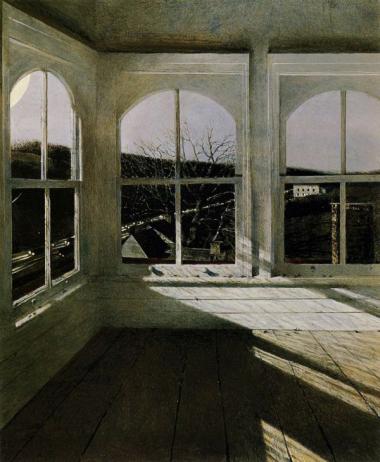

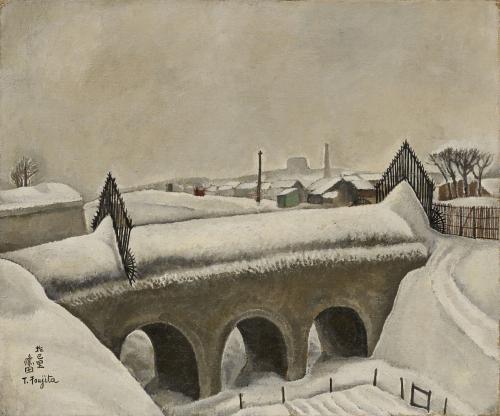

"The Garden in Winter"

(1967)

John Nash

1893 - 1977

_______________________

The Detail makes the Tragedy

Hélène Cixous

The Detail makes the Tragedy. No atrocious Tale possible without the frail crack in the wall that surrounds the unspeakable. Othello is contained in a handkerchief. This Handkerchief turns anyone who touches it into a monster. The Detail is this seepage and this handkerchief, which hides-shows, gives on the scene impossible to behold. The Detail is the representative and representation of the act of mutation that turns people like you and me into the monsters of Tales. The Detail is a visual shibboleth, dreadful to behold. Whoever sets eyes on it will never again be the same. Generally, when you enter the Tale for the first time, you pass over the Detail without noticing it. It gets lost among the host of signs. It was only many years later I noticed the Detail that gives us access to ‘‘The Metamorphosis’’ (‘‘Die Verwandlung’’) though it is perfectly obvious in the entryway where it vegetates and stinks, the eternal cadaver posted as a warning to the reader. But as it doesn’t call out or moan or squeak the avid visitor sweeps indifferently past the prophetic vignette and throws himself into the front room from which he doesn’t emerge alive. If only you’d read the warning Nothing wouldn’t have happened. But by definition the Detail hides what it shows. You can always look at the engraving Gregor Samsa cut out and deliberately framed in gilt on page one of the Tale, but it just so happens you still don’t see it you never will. The law of Details, how to think of its tricks? It hits you in the eye.

That engraving is a picture of the future.

Why do we always take the roads to madness? But for my mother who goes straight I have always gone zigzag.

[From Manhattan: Letters from Prehistory]

via Ballerinas Dance with Machine Guns

_______________________

Threshold

R. S. Thomas

1913 - 2000

I emerge from the mind’s

cave into the worse darkness

outside, where things pass and

the Lord is in none of them.

I have heard the still, small voice

and it was that of the bacteria

demolishing my cosmos. I

have lingered too long on

this threshold, but where can I go?

To look back is to lose the soul

I was leading upwards towards

the light. To look forward? Ah,

what balance is needed at

the edges of such an abyss.

I am alone on the surface

of a turning planet. What

to do but, like Michelangelo’s

Adam, put my hand

out into unknown space,

hoping for the reciprocating touch?

_______________________

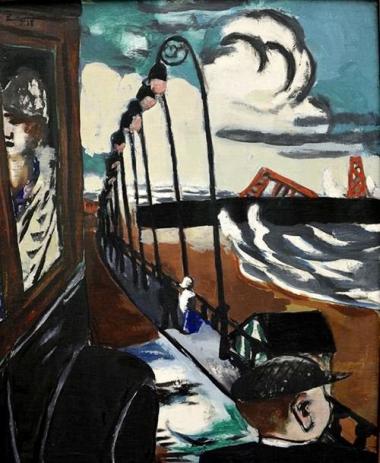

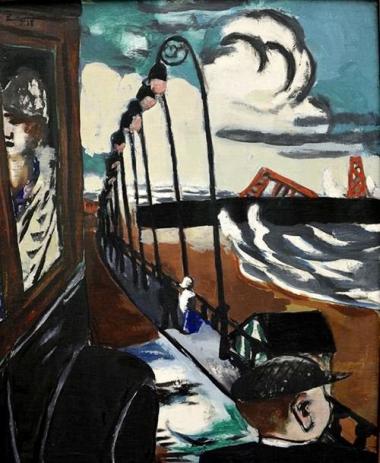

Strandpromenade in Scheveningen

1928

Max Beckmann

b. February 12, 1884

_______________________

After Jericho

R. S. Thomas

There is an aggression of fact

to be resisted successfully

only in verse, that fights language

with its own tools. Smile, poet,

among the ruins of a vocabulary

you blew your trumpet against.

It was a conscript army; your words,

every one of them, are volunteers.

via flowerville

_______________________

Crash Culture: Panic Shock, Semantic Apocalypse, and our Posthuman Future

S.C. Hickman

The machine gazes into the mirror, an abyss within an abyss. The eye that stares, stares back in a closed circuit – a feed-back loop contorted to the torsion of a solipsistic dance. Caught in the vacuum endgame of performativity rather than knowledge, each lost image moves in a circular void tempting it toward existence; else in utter disgust, an exit from this dark world of virtual multiplicity. Following the trajectory of ideas immanent to the register of thought unbound each image rides the time-wave of a falling arc into history, where human and machine gaze into each other’s eye discovering in the twisted lands of the twenty-first century a latent transport into oblivion.

Selfies are often shared on social networking services such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. We follow the gaze of their gaze through its manifold electronic incarnations like blip scores in a self-replicating image-feed for lost memes. Lost among our memetic images, our thoughts blank and emptied of their former glory, we ponder the inane vision of our bodies become immaterial objects – pixel pigments of another Order: the symbolon of an alien cult from the future displayed on the screen of our inexistence. All that remains is to chart the cartography of a hidden image; emptied of its meaning, we follow the nihilist gaze of dissident powers, extreme dispotifs accelerating us toward the extreme convergence of human history onto the Semantic Apocalypse.

...(more)

_______________________

As a God Might Be

Three Visions of Technological Progress

Meghan O’Gieblyn

boston review

The Brain Electric: The Dramatic High-Tech Race to Merge Man and Machine

Malcolm Gay

Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots

John Markoff

The Soul of the Marionette: A Short Inquiry into Human Freedom

John Gray

There are two kinds of technology critics. On one side are the determinists, who see the history of technology as one of inexorable progress, advancing according to its own Darwinian logic—the wheel, the steam engine, the autonomous car—while humans remain its hapless passengers. It is a fatalistic vision, one even the Luddite can find bewitching. “We do not ride upon the railroad,” Thoreau said, watching the locomotive barrel through his forest retreat. “It rides upon us.” On the opposite side of the tracks lie the social constructivists. They want to know where the train came from, and also, why a train? Why not something else? Constructivists insist that the development of technology is an open process, capable of different outcomes; they are curious about the social and economic forces that shape each invention.

Nowhere is this debate more urgent than on the question of artificial intelligence. Determinists believe all roads lead to the Singularity, a glorious merger between man and machine. Constructivists aren’t so sure: it depends on who’s writing the code. In some sense, the debate about intelligent machines has become a hologram of mortal outcomes—a utopia from one perspective, an apocalypse from another. Conversations about technology are almost always conversations about history. What’s at stake is the trajectory of modernity. Is it marching upward, plunging downward, or bending back on itself? Three new books reckon with this question through the lens of emerging technologies. Taken collectively, they offer a medley of the recurring, and often conflicting, narratives about technology and progress.

...(more)

_______________________

Journey on the Fish

Max Beckmann

1934

_______________________

RetroDada Manifesto

McKenzie Wark

RetroDada begins with disgust. Once again the world gets its war on. While some cities are attacked by bombers, others are strafed by art fairs. This time there’s no Switzerland of neutrality where refugees might cool their heels, as now the whole globe itself overheats. The insomnia of reason breeds monsters.

But before we can take two steps forward, let’s take one leap back. Back a whole century. Back to the first of the world wars to be numbered; back to the birth of Dada disgust. Back to that great refusal of what the century was to become. Why shouldn’t a .gif run backwards as well as forwards? Its RetroDada time! In principle RetroDada is against manifestoes, but it is also also against principles. So here goes nothing.

The world is full of mistakes, but the worst is the art that got made. Art gives us Dante’s Inferno as styled by interior decorators. RetroDada aims to please neither at art nor anti-art, as nobody should serve masters. We will put an end to spectacle and replace it with convulsive laughter from continent to continent. It’s shit after all, but from now on we mean to shit in different colors.

Psychoanalysis is itself the disease. It makes the bourgeois self seem interesting. Ethics produces atrophy like every plague produced by intelligence. Theory merely guides us in a round-about way to the prejudice we had in the first place. What we need are works that are tender and precise and forever beyond understanding. There is a lot of negative work to be done.

...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

ottawater / 12

Ottawa’s annual pdf poetry journal

edited by rob mclennan

The twelfth issue features new writing by Sylvia Adams, Susan J. Atkinson, John Barton, Frances Boyle, Stephen Brockwell, Carellin Brooks, Sara Cassidy, George Elliott Clarke, Anita Dolman, nina jane drystek, Claire Farley, Mark Frutkin, jesslyn gagno, Shoshannah Ganz, Jenna Jarvis, Ben Ladouceur, Sneha Madhavan-Reese, Karen Massey, Robin McLachlen, Colin Morton, Peter Norman, Julia Polyck-O'Neill, Roland Prevost, Tim Mook Sang, Lesley Strutt, D.S. Stymeist, Anne Marie Todkill, Deanna Young and Changming Yuan. Artwork by: Alysha Farling, Anna Griffiths, Anna J. Eyler, Erin Robertson, Gail Bourgeois, Jeff McIntyre, Nichola Feldman-Kiss, Patrice Stanley, Sarah Dobbin, Susan Roston, and Verbal.

from

Morning Song

Sylvia Adams

(....)

You don’t know the people inside your head,

are vaguely aware of them writing

feverishly through the night,

like the shoemaker’s elves fashioning, repairing.

You stand by sometimes watching, sometimes

listening transfixed as they read their diffident poems

or talk about their mothers, how this one’s

a nervous driver, that one has started dying

her hair, hoping to hide her age.

It takes you years to realize these nocturnal scriveners

wear many earnest faces all of them the same,

are constantly starting over, walk on the graves

of others, leaving tight little bundles of words

no longer needed, shaping what’s left into poems

weak and unpalatable as hospital custard

or once in a happenstance bearing the badge

of jaw-dropping inspiration. No matter:

last night’s flotsam and jetsam not worth

scooping up into your morning latte.

(....)

_______________________

“Indian Encampment, after Blakelock”

1977

Fritz Scholder

1937-2005

_______________________

Space Jew, or, Walter Benjamin Among the Stars

Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft

(....)

The growth of modern astronomy broke the enchantments of astrology, and on this reckoning Jantar Mantar (as viewed by our counterfactual Benjamin) might seem like a snapshot taken before the separation. Benjamin spoke, in elegiac terms, of the way we lost wonder’s trance, knowing all too well that from the perspective of the Enlightenment it had been good to wake up — sapere aude, “have the courage to use your own reason,” as Kant had said, and conquer unmündigkeit or “immaturity” — but Benjamin was more mindful of what “telescoping reason” had done to our rapport with the heavens. Benjamin’s question would likely have been, what are we to do with the ruins of wonder? Have we the time to build anything from them?

My fantasy about Walter Benjamin standing at Jantar Mantar involves a speculation about what a dead writer and critic might have thought about a site he never saw: what if astronomy and astrology were still allies, still lovers, my fictional Benjamin asks. What if the scientific revolution and the Enlightenment had not severed causation and meaning, the contingency of the universe and our sense of its purposefulness? My fantasy comes from a small but intriguing corner of the lively culture industry surrounding Benjamin: counterfactual fantasies about Benjamin successfully escaping Europe are a very real micro-genre. The expansive sweep of Benjaminiana includes Laurie Anderson’s 1989 album Strange Angels, dedicated to Benjamin and referencing his well-known description of the “Angel of History”; Jewlia Eisenberg’s 2001 album Trilectic, which tells the story of his 1927 trip to Moscow and his relationship with the Communist Party member Ana Lacis; and Charles Bernstein and Brian Ferneyhough’s opera Shadowtime, which is “counterfactual” in the sense that it starts with Benjamin’s suicide and then follows him, as if he were Odysseus or Dante, into the underworld. Very often, the Benjamin industry seems to be fueled by his charisma (his posthumous charisma; the living Benjamin seems not to have possessed that attribute in much abundance) as a weird combination of intellectual wunderkind and schlemiel loser.

(....)

While brushing aside counterfactuals as “unhistorical shit” or “parlor games” has become habitual for most professional historians, others take them seriously as means by which to expose causation. Still, other historians see counterfactual thinking as present in all historical thinking, whether made explicit or not. Counterfactuals are not, whatever their detractors think, pure leaps into fantasy. They are the renegotiation of empirical data — and yet they obviously flirt with an abandonment of the real, and with flights into fantasy. And beyond their task of illuminating causal relationships among historical developments, counterfactual questions have a kind of hermeneutic power, exposing the logics by which we read historical events, and exposing as well our attachment to different types of determinism.

(....)

If counterfactuals open our eyes to contingency, contingency in turn has the potential to disenchant. In many cases, a counterfactual glance at the sweep of human events would reveal no constellations, no signals, just noise, static, wave clutter. No grand unified theory, no ultimately rational emergent world-spirit, just particles, blood, and dust. Benjamin was against patterns, too, or against the search for certain specific historical ones. The myth that events are part of a larger story called “progress” was, for Benjamin, the hallmark of “bourgeois” history. He suggested that a more enlightened and free world (a world that was, among other things, socialist) would instead perceive the virtue of each moment, would daydream in terms of the immediate lived experience of hours, minutes, and seconds, rather than stringing events together over the centuries to make sense of it all. Still, if Benjamin was a Marxist, his Marxism was as selective as his Judaism, stripping away the teleology that still ran through Marx’s own thought, the sense that the logic of history would see our chains fall to our feet. Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History” is, in part, an argument for the recuperation of the potential latent in each moment of time, and against subsuming them within a larger progress-narrative; while one reading of Benjamin quite rightly emphasizes his “dialectics at a standstill,” there is another way to read his resistance to historicism: like formal counterfactualists, Benjamin was interested in restoring a sense of contingency to our understanding of the past.

...(more)

_______________________

"Portrait Of A Dream"

Fritz Scholder

_______________________

Spinoza Redux and Other Transpositions of the Posthuman Subject (Rosie Braidoti)

Zachary Braiterman looks at Transpositions: On Nomadic Ethics

(....)

–The ethical project is identified as “nomadic ethics” and “an ethics of sustainability,” with clear reference to the idea of nomadism in Deleuze and to the idea of conatus in Spinoza. The critical project is posed against tradition, which is mostly presented in terms of encrusted habit, toxicity, and authority.. Chapter 1 is meant to establish a posthuman ethics, whose main conceptual concerns are not rights, i.e. subjective rights or the rights of a human subject, but rather power-relations, capacity, and alterity. The transposition intended here is a shift in scale from the anthropocentric models to ones based upon more complex environments and material embodiments. The ethical is established as that limit beyond which human subjects are unable to sustain themselves in life. Therein lies the critique of late capitalism as an unsustainable economic and political system. What concerns the author as “ethical” is the self-formation of the inter-dependent body embedded in nature and with others.

–If there’s a telos to this book, it is in “becoming imperceptible,” by which Braidoti means no more and no less than the a future orientation and redemption from the past, becoming one with the common life of nature (zoe), merging into the environment. Understood here is a floating awareness, a radical and qualitative shift in perspective that comes when one abandons the self as a fixed social identity. At its heart “becoming imperceptible” is for Braidotit a coming to terms with death on good terms, in which the good, the ultimate ethical good is a self-styled death that overcomes the tension between eros and death. Allowing the organism to die on its own terms, to allow silence to wash over the subject at its end, the longing for death, for non-life at the heart of human subjectivity. Braidoti calls this the experience of eternity in time. Readers of Jewish philosophy will recognize this temporal and existential figure in Jewish philosophy, whereas Braidoti insists that this not a Christian or otherworldly figuration. Not unmoored entirely from “religion,” she calls it a “post-secular spirituality,” “redefined as a topology of affects”.

...(more)

via -synthetic zero

_______________________

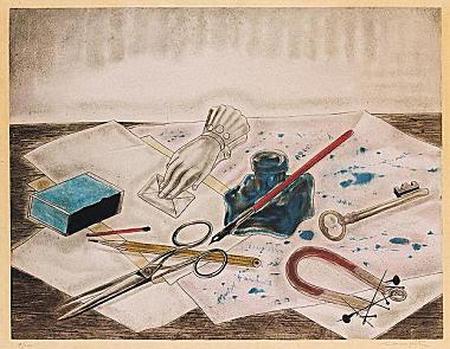

Carlo Carrà

1881-1966

_______________________

Untitled

Li Shangyin

translated by Chloe Garcia Roberts

Rush, rustling of the East Wind, a fine rain arrives

Beyond the Lotus Pool, is a delicate thunder

Golden Toad bites the lock, burning perfume enters

Jade Tiger weights the cord above the water well, circling

Young Secretary Han: glimpsed by Lady Jia though curtains, briefly

Talented King Wei: bequeathed Princess Fu’s pillow, only afterward

Spring Heart, refrain from competing with flowers in effusion

One measure of longing, one measure of ash

A Conversation on Li Shangyin: Chloe Garcia Roberts & Guangchen Chen critical flame

(....)

GC: A kind of hurting experience gets polished and decorated, which I think is indeed very Baroque—in other words, suffering becomes the object of decoration and aesthetic appreciation.

Now we finally see this poem wonderfully rendered into English. This is no small achievement. It’s quite a journey—from a purely visual experience of the Chinese characters to a word-to-word translation, to an elegant recreation of the original in a very different language. Can you tell me a bit about the process? Did your experience of Li Shangyin’s vision develop following a similar pattern?

CGR: I am always struck by the reverberation that Li Shangyin uses in his work. The images and the symbols in each poem reverberate against themselves and each other like notes, together they create a chord, which is the cord. (Cord: A “thread” which runs through and unites the parts of anything. –OED) He captures not just the components but the music that they make together, a harmony of disparate parts that I impossibly try to strive for in translating the work.

I begin of course by reading the poem. Reading it over and over again until the words coalesce into several different readings or understandings of the text. I do this so I can cast the net of the translation as widely as possible so as to catch as much of the implied meaning which resides behind the written words, the references, the wordplay etc. This is not to say that all of this multi-dimensionality can ultimately make it into the translation, only that I want to hold it in my head when creating the new incarnation, as superstitiously I believe that knowing these fine contours of the work can help me rebuild them in a balanced way in the new poem.

I then work on tracing the structure of the poem, finding the load-bearing words, the words that create the borders of the poems, the words that work in tandem with others, locating the images versus the symbols, the stories and images that are known, the stories and images that remain a mystery. Once I have taken everything apart and laid it out in front of me in notes and thought I then begin the process of putting it back together again, in English.

...(more)

Eis (Ice)

1981

Gerhard Richter

_______________________

Nature is What Hurts

Review of Timothy Morton's Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World

Robert Seguin

electronic book review

The posthumanist turn in recent theory and cultural studies continues apace. Posthumanism, briefly, is in general the effort to challenge and even displace the vestiges of anthropocentrism that persist within the conceptual regimes of the human sciences. In this, it follows a series of sustained and by now familiar decenterings of certain privileged subject positions: the postcolonial decentering of a certain Western subjectivity, or the queer decentering of a certain heteronormative subjectivity, for instance. Posthumanism wishes to go further, however, and seeks to decenter the human as such, principally by exploring the complex web of connections and correspondences that obtain between both human and non-human life forms and between the human and our increasingly multiform and complex technological apparatuses - to imagine then a kind of seamless continuum of earthly being, with no point on the continuum to be seen as ethically or epistemologically privileged in any way.

A certain upping of the conceptual stakes can be observed in the recent posthumanist theorizing that is indebted philosophically to those trends variously known as speculative realism or object-oriented ontology, two basic elements of which might be isolated for our purposes here. The first is captured in what philosopher Quentin Meillassoux calls ancestrality, the radical temporal disjunction and distention evidenced by things such as ancient rocks or the fossil record, which body forth realities and processes that radically transcend the operative evolutionary timeframe of human consciousness. The second element entails the attribution to nonhuman objects, and matter more generally, of a kind of generative power, thus evoking a “nature-culture continuum,” as Rosi Braidotti calls it. This is in contrast to the essentially inert, mute aspect that western idealism (an epithet that appears to characterize, for some posthumanists, the whole of western thinking as such) is typically understood to ascribe to matter. Taken together, these postulates partially define the growing field that Mark McGurl has recently labelled, in a nice phrase, “cultural geology.” These are the discourses of cultural study that have begun to borrow heavily from the physical sciences, especially cosmology, evolutionary biology, and chaos theory, in order to enframe the productions of human consciousness and human culture in an ever widening set of temporalities and physical processes - “deep time,” as it’s sometimes called, stretching back now thousands, now millions of years, radically re-inscribing our now rather puny seeming endeavors against a much vaster horizon, and challenging philosophy to stop being a “sop to the pathetic twinge of human self esteem” (xi), as Ray Brassier acerbically puts it.

Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World offers an interesting recent intervention in this context, particularly for those of us who come at cultural theory from a more materialist and dialectical perspective, as this last was an important aspect of Morton’s own approach before his apparent embrace of the object-oriented ontology of Graham Harman and others in this new book. ...(more)

_______________________

Matteo Massagrande

1 2 via Arsvitaest

_______________________

Philosophers As Bureaucrats Of Sadism

Peter Gratton

Philosophy In A Time Of Error

(....)

... it’s certainly not a task for us to imagine–sadistically–those cases that count, like the worst form of arm-chair philosophizing, a point I also had in mind when torture came up during the late Bush years in the classroom and students wanted to hash out various 24-style scenarios. Why spend our time in classes in such joint fantasies? Some will suggest that this then means that we will allow the lines to be blurred, we won’t distinguish–abstractly, mind you–between what is torture and what isn’t, and so on. But as philosophers, this only has the affect of making us bureaucrats of that violence, like those Bush-era (and no doubt, also Obama-era) attorneys parsing out in Kafkaesque ways all manner of horrors. We are not here to quantify pain, adjudicate this level of horror and no more, etc. Rather I always return the question: why precisely does that abstraction interest us, rather than dealing with the very specific example at issue? Why a need to measure how much horror a hypothetical Arendt would permit–here and no more? These moments end up as creative lessons in irresponsibility–not the reverse, a point I hope follows a bit from the above. If this means that leaves me out of many “applied ethics” or “political” discussions, then so be it.

...(more)

via —synthetic zero

_______________________

The Crusade Against Multiple Regression Analysis

A Conversation With Richard Nisbett

(....)

A huge range of science projects are done with multiple regression analysis. The results are often somewhere between meaningless and quite damaging.

I find that my fellow social psychologists, the very smartest ones, will do these silly multiple regression studies, showing, for example, that the more basketball team members touch each other the better the record of wins.

I hope that in the future, if I’m successful in communicating with people about this, there’ll be a kind of upfront warning in New York Times articles: These data are based on multiple regression analysis. This would be a sign that you probably shouldn’t read the article because you’re quite likely to get non-information or misinformation.

Knowing that the technique is terribly flawed and asking yourself—which you shouldn’t have to do because you ought to be told by the journalist what generated these data—if the study is subject to self-selection effects or confounded variable effects, and if it is, you should probably ignore them. What I most want to do is blow the whistle on this and stop scientists from doing this kind of thing. As I say, many of the very best social psychologists don’t understand this point.

...(more)

_______________________

September

Gerhard Richter

_______________________

Imagining a Poetry That We Might Find:

Conversation with Jerome Rothenberg and David Antin

MP3 (1:35:55)

Jake Marmer's introduction

“We were...desiring poetry, imagining a poetry that we might find – for which there was no strong evidence available,” says David Antin, reflecting on his college days, as he and Jerome Rothenberg sit with me in David’s dining room, in San Diego, around a tape recorder and a big French press. Desiring and imagining poetry – how different that is from merely writing, or reading, or even experimenting! Imagining and desiring: might that help shed some light on the incredible array of original, personal, deeply compelling poetic forms these titans of American poetry have invented, restored, and modified? As Antin points out in this interview: “I found a way to regard the poem itself as creating its own genre… We were looking for ways to overrun the tradition.”

To overrun the tradition, however, is also to extend back into the ancient past and retrieve, to recognize that which may not have been thought of as poetry. That impulse, as Jerome put it, “came out of the feeling that certain things were missing for us… Why is this not poetry? Why can it not be poetry, even great poetry? What keeps us from seeing it in those terms?... When I plunged into Technicians of the Sacred it was with desire for things to come with me and surprise me – and they did.” Note, this isn’t merely about finding new poetry, but more poignantly, recognizing within ourselves, that which prevents us from experiencing certain discourses as poetic. Is it a political barrier? Philosophical? Ritualistic? What’s at stake, as Rothenberg put it in the preface to Technicians of the Sacred, is “a life lived at the level of poetry.”...(more)

_______________________

Renfield

1999

Andrew Wyeth

Rough Sea

David Jones

1931

_______________________

“A Picture of Great Detail”: The Art of David Jones

Thomas Berenato

critical flame

“And so I make for myself a picture of great detail,” said the great Homer scholar Milman Parry in a 1934 address to the Harvard Board of Overseers. Parry was explaining to his audience how the “historical method” in the humanities works in practice. The researcher gradually learns the rhythm of inquiry: how to keep out of and go into the past by turns until an image of the object of study begins to wriggle itself free from the blur of oblivion. This empirical process—Blake called it “sweet Science”—takes time and patience and a dash of something that Goethe once termed “tenderness.”

The English artist and poet David Jones possessed these qualities in abundance—almost to a fault—along with a streak of contrariety with respect to his own place in history. The Art of David Jones: Vision and Memory, which accompanies an exhibition now on view at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, England, sets out to salvage Jones’s work from the relative neglect into which it has been falling since well before his death in 1974.

(....)But what is Jones’s “central message” after all? Some notes he made around the time of his struggle with Vexilla Regis give a clue. Meditating on the deployment, in drawing, of a line or curve to impart a sense of volume to an object, Jones reminds himself that what may look on paper like a firm border, a non-negotiable boundary, is actually, or also, a provocation to pastures new, a point of departure. “This so-called ‘outline’ must never be thought of as an end or termination, it must be thought of, on the contrary, as expressing a continuation, i.e. it must express the uninterrupted continuation of the surfaces and planes from the front & side to the unseen surfaces & planes at the back. If you keep this very much in mind as you draw it should help at least to check this tendency of regarding the ‘outline’ as a kind of stopping place—which is the last thing it is. It is no more a stopping place than is the sea’s horizon. It is really all a question of feeling that truth intensely enough.” The “central message,” in short, lies at the periphery. Jones is a poet of the marches.

...(more)

_______________________

Sea View

1930

David Jones1895 – 1974

_______________________

From “Odi Barbare”

Geoffrey Hill

XXIV

What is far hence led to the den of making:

Moves unlike wildfire | not so simple-happy

Ploughman hammers ploughshare his durum dentem

Digging the Georgics

Vision loads landscape | lauds Idoto Mater

Bearing up sacrally so graced with bodies

Voids the challenge how far from Igboland great-

Stallioned Argos

Vehemencies minus the ripe arraignment

Clapper this art taken to heart the fiction

What are those harsh cryings astrew the marshes

Weep not to hear them

Accolades Muses’ dithyrambics far-fraught

Borrowed labour ashen with sullen harrow

Cruel past that | Sidney and vesperal Tom

Campion courted

Put to claim not otherwise vowed the era

What else here goes | I am no Igbo wit well

Versed in Virgil Pindar Euripides child-

Hallowed Idoto

Revelation blessed in its unforthcoming

Closed with tempus aedificandi tempus

Destruendi bringing discharge of measure

Blasting the home-straight

...(more)

_______________________

Geoffrey Hill

_______________________

Geoffrey Hill, The Art of Poetry No. 80

(....)

We are difficult. Human beings are difficult. We’re difficult to ourselves, we’re difficult to each other. And we are mysteries to ourselves, we are mysteries to each other. One encounters in any ordinary day far more real difficulty than one confronts in the most “intellectual” piece of work. Why is it believed that poetry, prose, painting, music should be less than we are? Why does music, why does poetry have to address us in simplified terms, when if such simplification were applied to a description of our own inner selves we would find it demeaning? I think art has a right—not an obligation—to be difficult if it wishes. And, since people generally go on from this to talk about elitism versus democracy, I would add that genuinely difficult art is truly democratic. And that tyranny requires simplification. This thought does not originate with me, it’s been far better expressed by others. I think immediately of the German classicist and Kierkegaardian scholar Theodor Haecker, who went into what was called “inner exile” in the Nazi period, and kept a very fine notebook throughout that period, which miraculously survived, though his house was destroyed by Allied bombing. Haecker argues, with specific reference to the Nazis, that one of the things the tyrant most cunningly engineers is the gross oversimplification of language, because propaganda requires that the minds of the collective respond primitively to slogans of incitement. And any complexity of language, any ambiguity, any ambivalence implies intelligence. Maybe an intelligence under threat, maybe an intelligence that is afraid of consequences, but nonetheless an intelligence working in qualifications and revelations . . . resisting, therefore, tyrannical simplification.

...(more)

_______________________

The Garden Enclosed

David Jones

1924

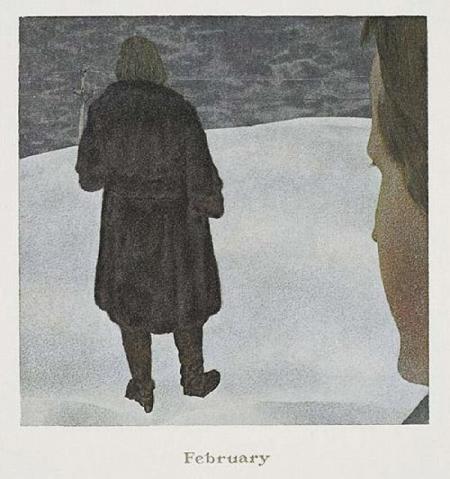

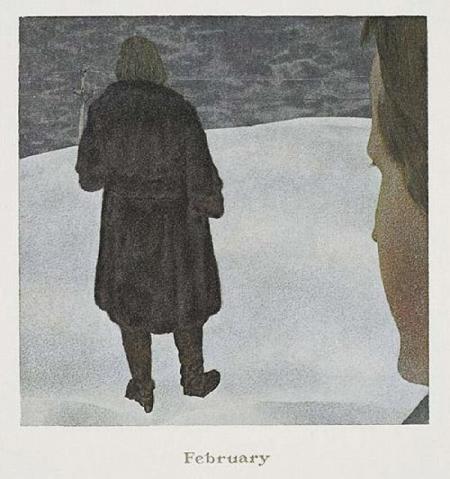

February

from

Book of Hours: Labours of the Months

1979

Alex Colville

1920 -2013

_______________________

Certainties [pdf]

The Maxims Of Martin Traubenritter

revised and enlarged

Robert Kelly

(....)

6.

We look at children playing in a world of things, sensations, perceptions. We try to teach them language. Language estranges them from what is to be known. Do we do it because we envy their total immersion in this actual world? Or do we yearn to give them language so they can talk to us, tell us, remind us of what we lost, forgot? And the cost to them of such messages we receive, it’s terrible but scarcely noticed in the busyness of things: the loss of their own immersion.

7.

Language is the real baptism—the enrolment of the newborn into a world made up almost entirely of conventions—religion is not the only religion, alas.

(....)

Metambesen_______________________

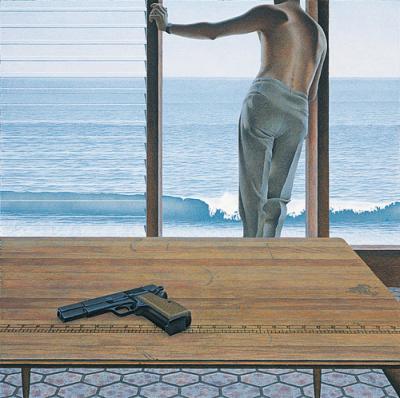

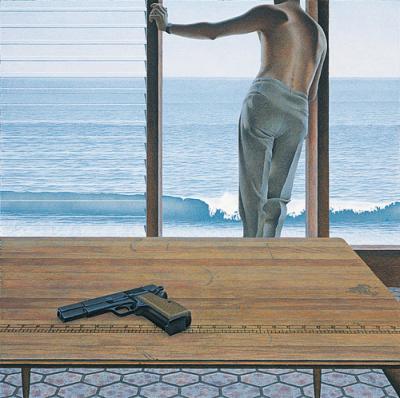

“Pacific”

Alex Colville

1967

_______________________

The Pacific Wall of Kienholz/Lyotard

David Cook

ctheory

Perhaps it is just what happens when one reaches the West coast of America--the Pacific Wall as Jean-François Lyotard calls it in a rather obscure and obscured text written in the nineteen seventies. Perhaps a similar sensation confronted Hitler when, facing the Atlantic, he is turned back towards the immolation of the ground war. Backs to a wall and the scene turns nasty. Backs to the wall and the catastrophe strikes. This will be played out, as we will see, in the fascism and racism all too well known in the binary twin of Amerika/Europe or, if you prefer, Lyotard/Kienholz.

Lyotard, like many of his French colleagues, went to the coast as a visiting professor. Sitting in the Geisel Library of the San Diego campus, evidently named after Dr. Seuss, one enters the fantasy world of make believe and children's rhymes for Geisel and for Lyotard, as well as rather fanciful stories. In an odd way this is reflected in the library itself, which is unique by being the first library to embrace Google and in having a phantom third floor and with a wall of glass facing the Pacific--the virtual coming to rest in the labyrinth and in the gaze over the Pacific, two themes that occupy Lyotard.

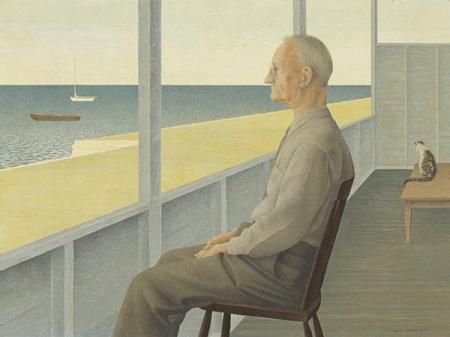

And Lyotard is not alone in his fascination for the view. Take for example, the Canadian artist Alex Colville's haunting work Pacific 1967. Picture the back of a shirtless man looking out of the glass window on to the ocean, a revolver on a table in the foreground. Painted in 1967 this work catches that period of the paroxysms of violence in the US.

...(more)

_______________________

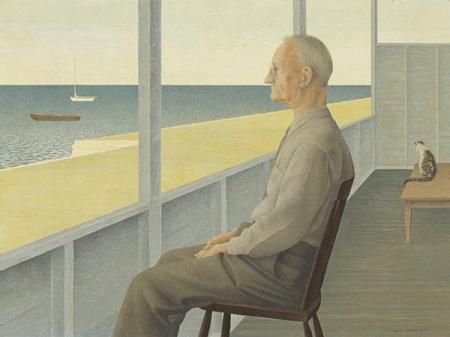

Man on Verandah

Alex Colville

1953

_______________________

The Society of the Spectacle Reconsidered: Good Marx or Bad Marx?

John Clark

There are now three translations of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle in print, and the work has penetrated intellectual popular culture to a certain degree. Ironically, you can now find ads all over the internet that mindlessly repeat the same clichés to market this scathing critique of consumer capitalism. A long blurb begins by touting it as “the Das Kapital of the 20th century.” By some strange coincidence, Amazon, Walmart, Powell’s Books, Abe Books and Google Books all agree totalistically with every last word of the long spiel. Even the “Book Depository” couldn’t find anything in it to shoot down. On a more serious note, Ken Knabb claims that it is “arguably the most important radical book of the twentieth century”—a rather grandiose claim, and I’d hate to get assigned this side of the argument in a debate. Nevertheless, it’s somewhere up there with the most influential works, and one might certainly wish that it had actually left Lenin’s What Is To Be Done?, Mao’s Little Red Book, and Guevara’s Guerilla Warfare in the dust.

One reason why this is an auspicious time to reconsider Debord's

Society of the Spectacle is the t that a revised editionof Knabb's translation has just appeared (Bureau of Public Secrets, 2014). It will be a very valuable resource for the studyof Debord and the Situationists. Knabb has not only improved his already very competent and readable translation, but also added extensive and very useful notes. Debord was sometimes vague about his sources, so Knabb has tracked them down, and often adds helpful comments on their significance. Furthermore, he has added notes that provide extensive background and bibliographical information on radical and revolutionary history. He also cites other Situationist texts onvarious topics, which is extremely useful, since there is an unfortunate tendency to equate all Situationist ideas with those of Debord.

Situationists reached many impasses, as will be discussed shortly, yet made a huge contribution to the development of radical thought. It still has crucial lessons for the left, and the libertarian left in particular. If the Situationists had done nothing else, it would be enough that they showed the fecundity of the encounter between Marxism and anarchism, and the folly of being naively and reactively "against Marx" in the name of anarchism. They show us why we need to be for Marx for the sake of anarchism, and against Marx for the sake of Marx.

(....) The Society of the SpectacleGuy Debord

(New Annotated Translation by Ken Knabb Bureau of Public Secrets

_______________________

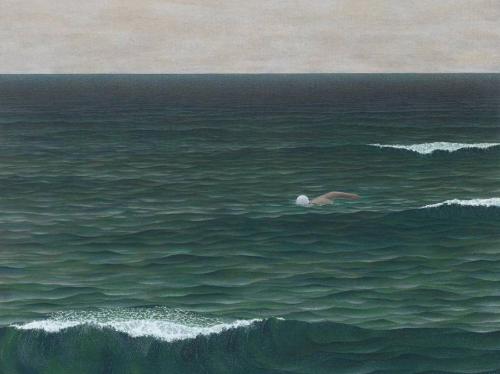

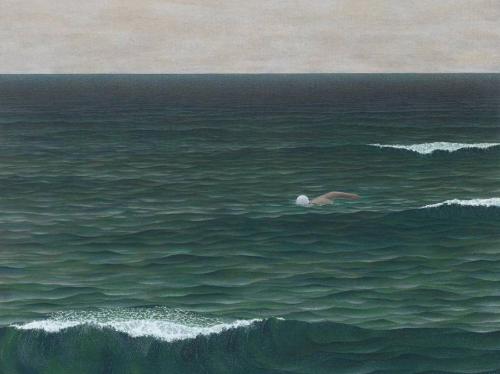

Swimmer

Alex Colville

1962

_______________________

e-flux 70 - February 2016

The Vectoralist Class, Part Two

McKenzie Wark

What if history can be neither negated nor accelerated? Perhaps second and third nature have been built so broad and so deep that there's no getting around this infrastructure. Thus while the commodity economy keep plodding along, at its own relentless pace, it forms agents of any class in its own image and obliges them to work in the forms it determines. What if even the vectoral class had little power anymore over its own creation? _______________________

The Horror of Materialism

Larval Subjects

(....)

The dream of an identity of being and thinking is also a dream of emancipation; for where presence reigns there is also no need for an alienation in the sovereign. The sovereign rules because we believe him to have knowledge, wisdom, to lead us to flourishing. Where we have this knowledge we no longer need him. Today that dream lies in ruins. No one can master it all; no one is an expert. It’s turtles or authorities all the way down. None of the scientists at CERN really understand what the others are doing, but must trust what the others are doing, that they know, to do what they’re doing. The presence called for by the tradition of epistemology is no longer sustainable. Everywhere we just encounter citation. And at that point, I wonder, what becomes of the dream of philosophy? How must we conceive of knowledge, and knowledge as it relates to emancipation, today?

...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

Stephen Burt on C.D. Wright

When C.D. Wright died Jan. 12, American poetry lost one of the great ones, one of the figures who changed what the language can do, one of the writers whose lines and titles, sentences and similes are going to last at least as long as American English. That’s something I believe, but it’s also something that seems inappropriate, even rude, to say, because Wright’s artistic powers cannot be separated from her deep sense of democracy, her work against boundaries, rankings and exclusions, her insistence that poetry, and society, should become, not a hierarchy or a star system or a way to exalt a singular self, but a way to be generous, to share the powers we get, to give of oneself, to let everybody come in.

...(more)

From “The Obscure Lives of Poets”

C. D. Wright

How is it that you live, and what is it you do?

— William Wordsworth, to the leech-gatherer

Three, no, four, that I know, married women

of means and brains. One grew moss on her tongue, waking from dreams that smelled

of mildew or hoary socks on a smothering train.

One turned to falconry and the construction of seed bombs to be dropped from three-

story houses. One burned her burka upon being released

from prison for the fourth time shamed so down deep in her molested self, washed

henceforth in formal darkness, another burned

her wedding dress in a fire pot while house finches splashed in the birdbath. [how one

moment touches on another moment and a thought flickers on and off ]

One poet, obsessed with vulvae, son of a butcher,

displayed a large bezoar on his coffee table, and slept in the bear nests in the d’Ardèche,

obsessed. One poet, adopted shortly after birth

by a levee builder on the St. Francis, shot himself with a target pistol on a beautiful

afternoon in early June. One lay across the tracks

on the brink of the Tiananmen uprising. One picked up her manuscript, a block of ash,

from the embers of her Oakland home. Bakhtin, as we know,

smoked his very best pages in prison. The poems of Radnóti were found by his widow in

his overcoat, in a mass grave. ......(more)

_______________________

Beckett on Film: PLAY

(Dir. Anthony Minghella, 2001)

vimeo

PLAY

A play in one act by Samuel Beckett

(....)

W1: Yes strange darkness best and the darker the worse

W2: Yes perhaps a shade gone I suppose some might say

M: Yes peace one assumed all out all the pain

W1:till all dark then all well for the time but it will come

W2: poor thing a shade gone just a shade in the head

M: all as if never been it will come Hiccup. Pardon

W1: the time will come the thing is there you'll see it

W2: Laugh . . . just a shade but I doubt it

M: no sense in this oh I know none the less

W1: get off me keep off me all dark all still

W2: I doubt it not really I'm all right still all right

M: one assumed peace I mean not merely all over

W1: all over wiped out --

W2: do my best all I can --

M: but as if never been --

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

The hurts of wanting the impossible

A review of 'Supplication: Selected Poems of John Wieners'

Matt Longabucco

(....)

It’s fun to sit on the subway in New York and read this new Wieners collection with its one-word title, black on cream: Supplication. Wave Books’s austere design suits poems that have been sacred to me since I was handed them as talismans, years ago, by poet friends. How much recognition do we want someone whose true home is “underground” to get? Underground because he chose Boston, lyricism, and a courtly remove. And more, because he chooses perdition: “Damned and cursed before the world / That is what I want to be.” Poet and critic Andrea Brady, in her work on the poet’s archive, quotes Foye: “Nobody had ever seen anyone throw themselves into the abyss the way John did.” Why does a person throw himself into the abyss? Why does a person take heroin? And then write of it, “But I don’t advise it for the young, or for / anyone but me. My eyes are blue”. Two lines that manage to be all at once knowing, greedy, arrogant, assertive of a special power and also, to my ear, aware of the hollowness of that assertion (it’s arbitrary and comes too readily to hand). Drugs are for escape, they’re for posturing, they’re for denaturing the visible. But in the case of this poet of loneliness, they are also a way to “collapse in a heap on the bed of the world”. Denied our lives, we seek oblivion, and hope that beyond or through it we might be permitted to alter the order that foreclosed our true existence from the outset. Collapsing, dissolving: we have been taught to act, but Wieners knows it’s better, instead, to beg — to be convincing, under extreme pressure, by manifesting preferable alternatives with the allure of a mirage. He chooses supplication.

...(more)

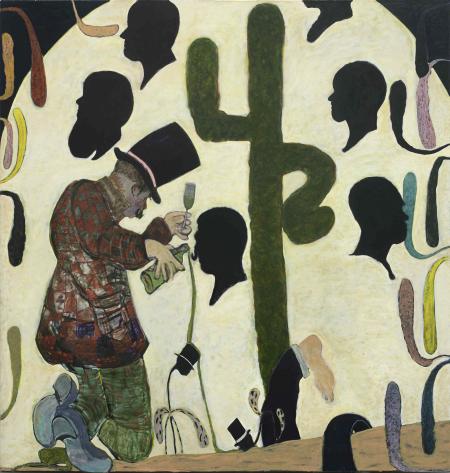

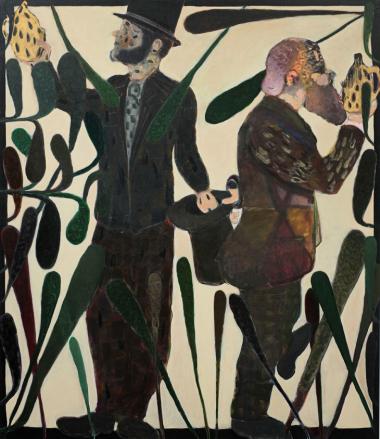

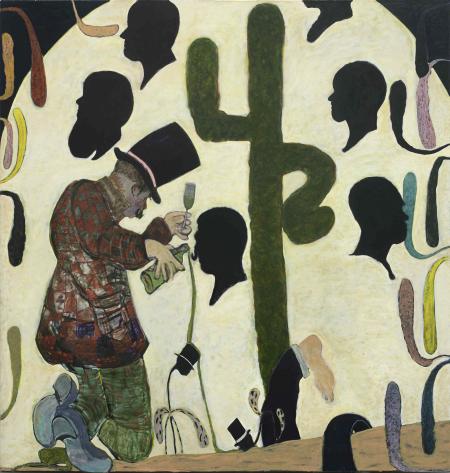

The Problem with History

(2010)

Ryan Mosley

1

2

Ryan Mosley: interview

_______________________

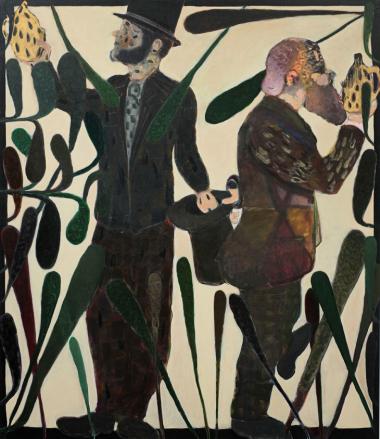

Carnival Theory

Jennifer Higgie on the bewildered mystics, mournful minstrels and mysterious rituals of Ryan Mosley’s paintings

frieze magazine

I’m not convinced that you need me to explain Ryan Mosley’s paintings. Everything you need to know about them is right there, humming on the surface: trippy, funny and melancholy, these are virtuoso hallucinations in a high-keyed palette – hot pinks, fluorescent orange and wild flashes of cerulean blue. Mosley’s canvases are populated by merry turncoats, bewildered mystics and mournful minstrels, all coming or going or mutating into something or someone else: dancing, smoking, fleeing or wrestling, making music, performing enigmatic rituals or just sitting, staring into space. Many of them appear to be searching for something, be it salvation, a god or a good time. Bodies sprout limbs in unexpected places; tops hats commingle with topiary; an avalanche of umbrellas, pipes, skulls, cacti and caps, birds, banjos, beans and boots tumble from painting to painting. Like out-takes from fairy tales, the works have a narrative thread buried deep beneath their surfaces, but if you’re after a beginning, a middle and an end, then you’re bound for disappointment: nothing so straightforward exists here.

The head – the source of all thinking and dreaming – and what contains and covers it, is a recurring theme. Mosley – and I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say so – is haunted by hats: towering top hats, floppy brown caps and huge hair that may as well be a hat. As in life, faces are complicated: like mad flowers sprouting from the same stem, there are often more than one on a single neck or lots of them embedded in someone’s hair (Oak Maiden, 2008); they also have a tendency to morph into masks. Beards are popular not, I assume, because they’re fashionable, but because in Mosley’s world there is no time to shave and, anyway, in these eccentric lands I suspect barbers are thin on the ground. Dead heads, like a chorus of tipsy memento mori, also occasionally make an appearance, but they’re not particularly gloomy. In Dance of the Nobleman (2010–11), for example, skulls float about a dancing man like dreamy girls at a party, while an audience of blank, uniform heads watches them.

...(more)

via Synthetic_zero

_______________________

Smoking Pilgrimage

Ryan Mosley

2014

_______________________

translation

Maja Haderlap

Transled by Tess Lewis

is there a zone of darkness between all languages,

a black river, that swallows words

and stories and transforms them?

here sentences must disrobe,

begin to roam, learn to swim,

not lose the memory that nests in

their bodies, a secret nucleus.

will the columbine’s blue be a shade of violet

when it reaches the other side,

and the red bee balm become a pear, cinnamon-

sweet? will my tench be missing a fin

in the light of the new language? will it have to learn

to crawl or to walk upright?

does language know how to draw another language towards it

or only how to turn the other language away? can each word,

then, risk the transit, believe itself

invulnerable, dipped in pitch and hard as steel?

The Reverberations of History: Contemporary Austrian Literature

Words without Borders - February 2016

_______________________

Saying Nothing and hearing Everything

Ryan Mosley

2013

_______________________

On Rae Armantrout's 'Just Saying'

Matthew Gagnon

jacket2

Rae Armantrout’s 2013 book Just Saying, a phrase that calls into question the veracity of what we say, think, and feel to be the case, or a phrase used to offload the force of an insult, suggests a motif of our inability or refusal to render our systems of thinking and believing in convincing terms. To be sure, the poems are varied in their address, circling around domestic concerns, mortality, social codes, product placement, forms of transactions, and systems of belief. One of the moves that Armantrout makes so well is to channel the many-tongued voicings of the clichéd-chorus. In the cacophonous, hyper-mediated Internet age, in the postrecession capitalism of America, in the images reflected back to us from the culture industry, Armantrout’s poems take on the bricolage of heterogeneous language acts and recast them to render new systems of meaning. It is in this recasting that poetry can be thought of as an instrument to not only document our present conditions on the ground, but to refigure those conditions, to see them anew.

...(more)

_______________________

The Thirsty Scholar

Ryan Mosley

2010-2011

_______________________

Anti-Birthday Poem

Ya Shi

translated by Nick Admussen

Using vague pronouns to indicate the needle in the cottonball,

he, she, it....

If the sentence is nothing but subjective, then please cross it out.

Thick violet medicine is installing a tiny propeller

between half-dream and half-wake, carrying the hum call of bees,

indistinct but steady—

in my city's red-orange outpatient medical tower,

my discovery is: the noun of central authority,

aided by monkey doctors whose white hands reek of Lysol,

has sprinkled its syrup more or less everywhere.

Of course, what I am saying, it is a kind of memory.

If you are a nurse, please cross it out with a red pen.

(the subject awakens; being collapses like an edifice of sand)

Today, an early morning dripping with cicada song,

my old mother calls, says it's my lunar calendar

birthday, she will celebrate me with steamed pork.

But the isolated god sinks too deeply into his stage drama,

aloneness can be more than the last act...

Even at a play, it's no good to laugh too loud.

Pah, what I mean is: a simpler sentence

has complexity that you cannot control.

When it pierces the vein, will our vanity get crossed out too?

Drunken Boat 22

_______________________

Piano Tuners

Ryan Mosley

2011

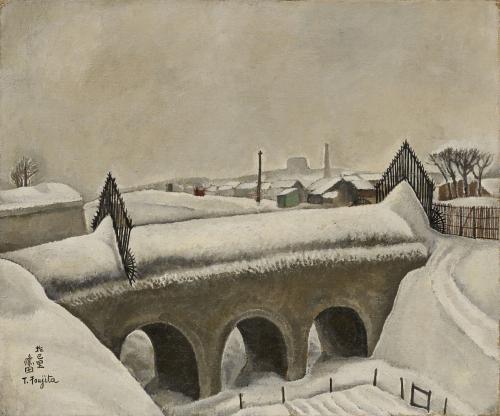

Porte d'Arcueil

Tsugoharu Foujita

1886-1968

_______________________

Arguments from a Winter’s Walk

Thomas Bernhard

translated by Adam Siegel

conjunctions

Translator’s Note

“It seemed to come out of nowhere”—Thomas Bernhard’s first novel, Frost, published by Insel Verlag in 1963. The work that preceded this bombshell gave no indication of the breakthrough to come—a neat caesura from the “routine” lyricism of Bernhard’s poetry (On Earth and in Hell, In hora mortis) to the “verbal fury” of the painter Strauch.

But the true breakthrough—what one German critic called “the birth of the coroner, the invective hurler, the egomaniac, the conjurer of catastrophes”—has been rediscovered. “Arguments from a Winter’s Walk” was published in 2013 by Suhrkamp as “Argumente eines Winterspaziergängers,” together with a companion work, “Leichtlebig.” Both were written in the winter and spring of 1962. While the earlier fragment, “Leichtlebig,” is similar in style and tone to Bernhard’s apprentice prose work (the abandoned novels Schwarzach Sankt Veit and Der Wald auf der Strasse), “Arguments,” written for publication in the Austrian literary journal Wort und Zeit, is Frost in nuce: It strips away the latter’s narrative interludes, devoting itself solely to the monologues of the unnamed doctor (several of these monologues appear, with slight variation in wording and placement, in Frost). “Arguments” is both dry run and distillation, a palm-of-the-hand version of the work to come, and the closest look we have of the Bernhard laboratory at zero hour.

(....)

Out here are peculiar valleys, said the doctor, and in these valleys are castles … one goes into them and there is nothing more in the world to seek out, the world whence one came … doors open, and behind them, enthroned, sit people in expensive clothes, as though drawn from nonexistent portraits, unheeding … one enters … one is addressed, seemingly without ever hearing a voice or language … having always been untutored in this art … I know nothing of words … nothing of answers … one doesn’t speak, one just listens—everything has a serviceable name, a label, none of it applied in error, you should know … they say simple things that float above you like a cloudless blue sky … nothing fantastic though it all stems from fantasy … nature—the greatest simplicity, opulence, amiability, nary a trace of sin … not even a hint of discord … a perpetual honeymoon, you should know, just cool reason and the innateness of concepts … all our days and all our nights—comely faces for now and for always … sleeping and waking … the air wrought so clear … my God—how apt! … the slow effect of ideas, feelings, climaxes, feigned amazement … laws that lack the punitive element have a certain validity, mind and temperament united in human nature—logic set to music … old age capable of beauty, youth rising like foothills … in the afternoon the shadows fall … truth lies in the bed of the river, they say, the inscrutable as realization … this is, said the doctor, more like a revelation from a dream, but truer than most means of contemplation … (....)

...(more)

_______________________

Five Prose Poems

John Olson

alligatorzine

The Shine of Eternity in a Postcard Rack

Language is shaped by abstraction. Which isn’t saying much. But it’s true. The luminous roots of a ripe truth blossom into similes. A mouth is like a spout and a tornado endorses the airport spoons. The structures endure. Envy hurls its descriptions of wealth at a single wool glove and unemployment is ghostly. Anyone will tell you that. A dazzling evocation is longer than a murky sensation and the day convulses with parody. I’m not joking. The travel agent dialed the wrong number and got Kierkegaard rather than Socrates. This is how we ended up in Corsica rather than the Canary Islands. The sculpture in the corner startled us with its exhalation. A small stone condensed the ocean into a hard inscrutable wrinkle. This is how perceptions happen. They begin as a stimulus in the nerves and travel to a place in the brain where paper lanterns float in the river Oi and images crash among the ganglion attracting mosquitos and flies. As soon as you begin writing poetry you find yourself in a foreign country. It may be the country of your origin, but it will soon enter your eyes and skull as a foreign country. That’s pretty much the whole point. The reason for the endeavor.

...(more)

_______________________

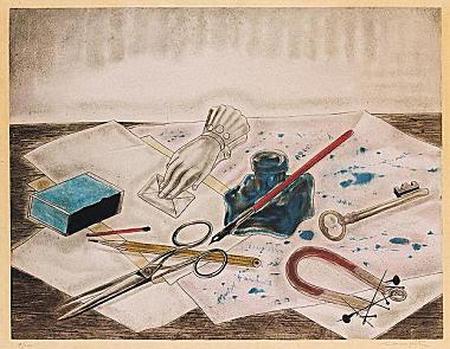

Tsugoharu Foujita

_______________________

"To rule forever," continues the Chinaman, later, "it is necessary only to create, among the people one would rule, what we call...Bad History. Nothing will produce Bad History more directly nor brutally, than drawing a Line, in particular a Right Line, the very Shape of Contempt, through the midst of a People,-- to create thus a Distinction betwixt 'em,-- 'tis the first stroke.-- All else will follow as if predestin'd, unto War and Devastation."

- Pynchon, Mason & Dixon

_______________________

Three Prose Pieces

Martin Edmond

Le bateau ivre

in the Timor Sea

The boat they gave me was a small wooden shell, a coracle, without a sail or oars: half a coconut lacking the meat. There was just enough room in it to recline. I didn’t care. I drifted down the estuary, indifferent to my fate as to the world around me. The current took us out into the fuming tides where, lighter than a cork, we danced upon the waves. I ate, I drank. I slept. I tried not to think. Days passed, and nights, and I saw nothing but the waves rolling eternally over the graves of the dead. After not so many days my food ran out and I began to hunger; lying sick in the bottom of the boat. Sometimes it rained and then I drank from the sky. I must have fallen into a delirium. When the sea rose and salt water washed over the edges of the hull I counted it a blessing: a douche of blue wine washing us clean. I was spattered with shit and vomit, on the outside, and on the inside gathered the grimy accretions of thought and all that it produces. Regrets, second guesses, ifs and buts, all the rest of that contaminated crew. So the sea’s blue wine washed over us and then it seemed I bathed in some oceanic unauthored poem, azure, lactescent, infused with stars that I sometimes glimpsed, like promises, far above; a pale scrap of flotsam, a dreaming, drowning man, sinking towards death; yet voyaging on. ...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

|