|

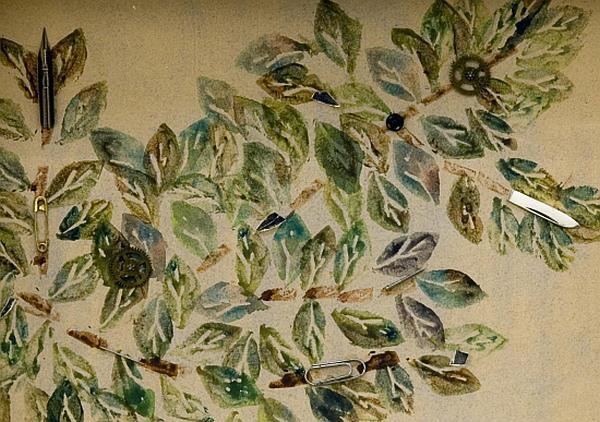

The Skirts of a Wood

1825

Samuel Palmer

b. January 27, 1805

_______________________

Doubts and a Hesitation

Garous Abdolmalekian

translated from the Persian by Ahmad Nadalizadeh and Idra Novey

Even your name

I have doubts about

and about the trees

about their branches, if perhaps

they are roots

and we have been living

all these years underground.

(....)

I am

a captive man’s conjectures

about the seasons behind the wall.

...(more)

Guernica

_______________________

Rilke's Russian Poems

translated by Philip Nikolayev

"On returning from his first trip to Russia, full of deep impressions and planning to move there permanently (a dream that never came true), Rilke suddenly found himself writing poems in Russian. As he noted in his diary, the first of them “unexpectedly occurred” to him in the Schmargendorf forest near Berlin in late November 1900. By early December he had written six Russian poems. He dedicated them to Salomé, who found them “grammatically off” yet poetic. He revised those and added another two in April 1901. In the fall of 1900 Rilke met his future wife, Clara Westhoff, and his life changed. He never returned to Russia but retained his love of it and his ties with Russian poetry, namely, with Marina Tsvetaeva and Boris Pasternak.

My translations of Rilke’s Russian poems are intended as an experiment in bringing to light their substance, form and implied tone as faithfully as I could manage, while stripping away the infelicities of the originals."

—Philip Nikolayev

[Two Poems of April 1901]

I’m so tired of trials by morbid days.

An empty night, windless across the fields,

lies plain above the silence of my eyes.

My heart began like a nightingale begins,

but could not finish the telling of its words,

and all I hear now is its very silence

swelling up in the dark like a nightmare

and darkening like the last gasp of air

by an unlamented child past all remembrance.

*

I’m so alone: nobody understands

the silence that is the voice of my long days,

there being out there no such wind as opens

wide the ample heavens of my eyes.

Outside my window an enormous day stands

on the city’s strange edge, a large man lies,

awaiting. Is this I, I ask myself,

awaiting what? And where’s my soul?

...(more)

The Battersea Review

_______________________

Blue Poles

1952

Jackson Pollock

b. January 28, 1912

_______________________

The Mind of the Modern: An Interview with Gabriel Josipovici

Victoria Best

Numéro Cinq

(....)

VB: Looking over your collected works and the experience I’ve had reading them, I’m reminded of Barthes and his comment that some of his best reading occurs with the book face down on his lap, staring into the middle distance. There is something so potent that happens when your writing comes into contact with my imagination. There’s a concept you may have heard of – the ‘unthought known’ – created by psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas. It refers to the immense store of knowledge that we own unwittingly, having never put it into words because we became aware of it in a wordless fashion. Bollas says: ‘There is in each of us a fundamental split between what we think we know and what we know but may never be able to think.’ Some of it will never be articulated and so, he says it’s important to ‘form a relationship to the mysterious unavailablity of much of our knowledge.’ And somehow, this is how I feel reading you. You take me towards the unthought places without ever speaking them yourself. It’s the spirit of the Between, if you like, who has his own chapter in Goldberg. Does that make any sense to you?

GJ: Yes, it makes a lot of sense. It’s what I look for in my writing, what I want to read and can’t find in the writing of others. I’ve never read Bollas, but what he says makes perfect sense to me. I wouldn’t even call it a ‘fundamental split’ – I think rather that our bodies know more than we do and that the task of art is to find forms and words that will allow the body to speak.

...(more)

_______________________

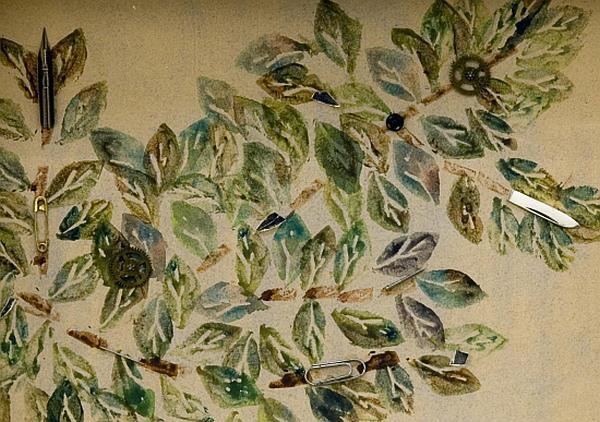

Waiting

detail

Marcel Mariën

1945

_______________________

Marcel Mariën

(1920-1993)

McKenzie Wark

Marcel Mariën (1920-1993) is not the best known of the surrealists – it doesn’t help that he was Belgian. But he has a few claims on our attention. For one, he invented his own version of what is now called object oriented ontology in 1944. For another, he had a theory of the society of the spectacle that pre-dates Debord’s by nearly a decade. And for a third, he was a fine aphorist in the style of Lautréamont.

(....)

he Belgian surrealism of Magritte and the more hard-core Belgian poet Paul Nougé, was a poetics of producing disturbing encounters. The Belgians were opposed to André Breton’s surrealism of automatic writing and contemplation of the marvelous. They were closer to Paul Eluard’s maxim that “the poet is one who inspires far more than he is inspired.” Mariën took from Nougé a poetics of producing disturbing encounters in the moment of reception.

Mariën’s ‘Nonscientific Treatise on the Fourth Dimension’ of 1944 has recently been translated for the Surrealism Reader (Tate 2015). It begins: “Every object, thing and body has four dimensions. A pear, a house or a woman have their height, width, depth and image (or surface). There fore the eye always perceives only the fourth, the image-dimension, which is also mind, thought, dream, memory and that of which we speak… Touch cannot reach the true depth of objects any better than the eye can. The universe is hermetic to them both.” Perhaps we could think of object oriented ontology, of which this might pass as a basic statement, as a late version of surrealism.

...(more)

_______________________

beech and oak

Samuel Palmer

_______________________

Three

Darin Ciccotelli

conjunctions

Honeysuckle

Our lives no longer feel

attared. The grand pronouncements

feel fine, like how discs of blood

disperse themselves throughout

the body, like how the bloodworm

swells to move. I accept the life.

I accept belatedness.

Then rain comes on without trajectory.

It is simply crowds. On the car, silver enamel.

In one sentence, the automobile festoons

toward certain

death and is freed from it, the miss,

the child’s backseat fright,

happenstance.

That night, absently flossing one’s teeth close

to the mirror, this mouth all skull.

Temple, bungalow, the merchandise

of ships beside trees—

most confusing still are the

conditions for attraction.

I don’t know if I want it, the sun

lice-infested. The lime in her burgeoning thought.

...(more)

_______________________

Replicant Futures: Nick Land and Alien Capitalism

S.C. Hickman

“I have not once had the least idea who or what I am,” says the Gray Bard of America. The nihilist undertones ringing out in that last dark hinterland of “ironical laughter” of the unknown “real Me” who outside our thinking, our intentional directedness stands in the unconscious libidinal matrix of the impossible Real, the indelible stamp of the withdrawn and “mocking me with mock-congratulatory signs and bows,” pointing in silence to old Walt’s “songs, and then to the sand beneath”. A dark vision indeed. Most think of Walt as the happy camper, the wild and free poet of optimism, democracy, and sunshine. But under it all is this moody and terrible being of pessimism and nihilistic despair who believed that all his vein striving, all the metaphoric display, the grand gesture of the Leaves of Grass were but the spume and spray of rolling sand flecks on the edge of the Mother, the Ocean. Necessity, Ananke, Fate: the triune power of the ebb and flow of life bound within the circular motion of the death drives that move among the impersonal and indifferent stars and galaxies like a blind god, mindless and alone. But there is no mind in the universe of death, only the endless entropic madness of the Real.

Nick Land in his essay Machinic Desire remarks “In the near future the replicants — having escaped from the off-planet exile of private madness – emerge from their camouflage to overthrow the human security system. Deadly orphans from beyond reproduction, they are intelligent weaponry of machinic desire virally infiltrated into the final-phase organic order; invaders from an artificial death.”

...(more)

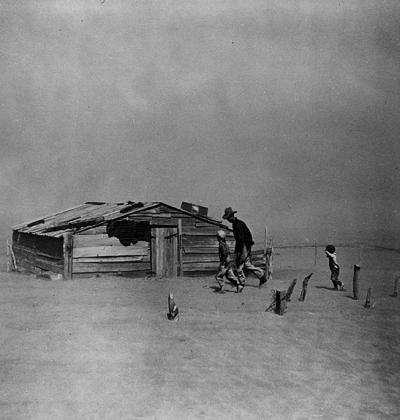

“Dust Breeding”

Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray

1920

a Handful of Dust: a conversation with David Campany

The Great Leap Sideways

(....)

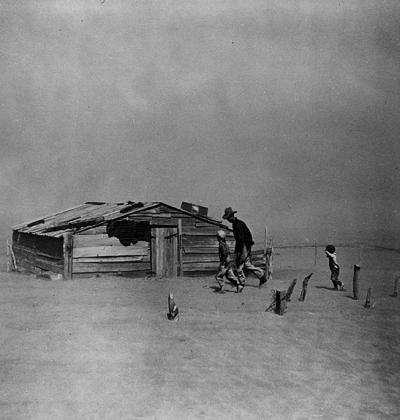

DC: In his 1963 memoir Man Ray describes how the dust photograph came about. He had been asked to document works in the collection of Katherine S. Dreier, who was then setting up the Société Anonyme and needed images for press and publicity. He recalls: “The thought of photographing the work of others was repugnant to be, beneath my dignity as an artist”. I’m fascinated by the idea of copy work being the basis, or even baseness of photography, and that a photographer with artistic ambition might be made anxious by it. That idea really haunts all of photography, but it energizes it too. Whatever the artistic ambitions, there remains a degree of plain, automated copying in all photography. I wanted to trace the arc of that anxiety and possibility. I also wanted to trace the arc of plain subject matter in photographic art, and you can’t get much plainer, less desirable than dust. Moreover, I think automated copying and dust are linked in photography. Dust is usually what you get as a side effect, both in modern life and in photography. There’s an unlikely kinship there. I can formulate it quite clearly now, but for a long while I was intuiting this and following my nose to a whole range of photographic practices and works from across the last century. These then got reconsidered much more soberly, and over time they were whittled down to a group or lineage that made some kind of sense to me. It included everything from postcards and press photos of dust storms, to avant-garde journal articles, conceptual art works, surrealist photography and documentary photography. Selecting and sequencing images. Over the years this has become my approach to writing. Images first, then words. In fact with my publisher MACK, we found a way to articulate this. The ‘image track’ of the book presents all the works one to a page, around 150 of them, arranged to articulate a chronology and various affinities. Then there’s an insert with my long essay, plus the works reproduced as small thumbnail illustrations. A viewer/reader can approach it image-to-image, or more ‘theoretically’ through my writing. Hopefully they’ll do both, feeling the differences and similarities.

...(more)

A Handful of DustDavid Campany Mack Books, 2015

“The curator David Campany’s new book accompanies an exhibition of the same name, and proceeds in a free-associative manner. This “speculative history” obsessively considers things that look similar, work in similar ways, are made of the same substance or are linked to one another by faint but undeniable threads. Its starting point is Man Ray’s 1920 photograph of about a year’s worth of dust gathered on the surface of Marcel Duchamp’s sculpture “The Large Glass.” But the book somehow wends its way to aerial reconnaissance photography, abstract landscapes, forensics, American dust storms, artists’ videos and the Iraq War. The cumulative effect is brilliant, almost novelistic, and the book comes with a removable insert featuring an equally brilliant essay by Campany.”

Teju Cole, The New York Times

David Campany

_______________________

Arthur Rothstein

_______________________

This might be how writing fulfils itself

Being in Lieu

a fine review of Stephen Mitchelmore's This Space of Writing

(....)

As I read through the collection of pieces in This Space of Writing, many of which are, but not confined to, reviews of works by Naipaul, Knausgaard, Josipovici, Munro, Bernhard, Kafka, Ford, Beckett, Lin (since they are also extensive meditations -- long trajectories of thought -- that hold all of these works in their widely crossed netting and transparency), I could see that, above all, Mitchelmore is particularly attuned to the form, the feel and the voice of a piece of writing -- the form/feel of its voice -- and that the sum of all these encounters makes his own writing here as tremulously alive and clear as so many of the works he writes about. After all, as Mitchelmore admits, 'sentences affect my experience of the world'. Instead of fumbling around for the feather and bolt contents in the plastic box of a book, whose clear sides we might all take for granted, Mitchelmore takes the whole box in hand and, like Nabokov, relies on the surer sense of his spine to know what it is he is holding.

...(more)

_______________________

Death of the PostHuman: Essays on Extinction, Vol. 1

Claire Colebrook

Open Humanities Press

Death of the PostHuman undertakes a series of critical encounters with the legacy of what had come to be known as ‘theory,’ and its contemporary supposedly post-human aftermath. There can be no redemptive post-human future in which the myopia and anthropocentrism of the species finds an exit and manages to emerge with ecology and life. At the same time, what has come to be known as the human - despite its normative intensity - can provide neither foundation nor critical lever in the Anthropocene epoch. Death of the PostHuman argues for a twenty-first century deconstruction of ecological and seemingly post-human futures.

Introduction: Framing the End of the Species: Images Without Bodies

(....)

When today—with horror—we look at young minds, we ask how they have become nothing more than cameras or computational devices. The young brains of today are not affected or world-oriented; they manipulate Facebook numbers with ruthless algorithmic force, and ingest images without digestion or rumination. We watch, with horror, as the human brain reverts to being not so much a reader of Proust as akin to a squid, or mere life. This tendency to be nothing more than a screen for images is observed as at once the brain's horrific tendency towards self-extinction (an internal and ever-present threat) and as accidental or extrinsic (something that has assaulted us from without, by way of technology and modernity).

(....)

Our very narration of the brain and its emergence as the properly synthesizing milieu from which all other imaging milieus need to be considered, shelters us from the thought of the inhuman images that confront us at the limits of the embodied eye. We can recall, here, Deleuze's criticism of Bergson, which is technical and counter-vital. Bergson, like so many other early modernists mourned the living and dynamic eye that had been sacrificed to technological expediency. For Bergson the intellect cuts up the world in order to achieve managerial efficiency and then subjects itself to that same technical calculus. The mind starts to operate with an image of itself as some type of viewing machine. Redemption, for Bergson, lies in retracing the path, regaining a vitality that would no longer be that of the bounded organism. Intuition would pass beyond its enclosed self-interests to arrive at the perception of life’s duration or élan vital. For Deleuze, by contrast, the problem is that the eye remains too close to the lived. (So, today, when we demand ‘reality’ of television and cinema, or if we criticize cultural production for being too irrelevant or divorced from everyday life, we do so because we think there is such a thing as life and reality to which vision ought to be subordinate.) Rather than asking the eye to become organic once more, and to re-find its place in life, Deleuze asks for an inhuman perception: can we imagine the world without us, not as our environment or climate? Drawing on Bergsonism, rather than Bergson’s concrete example of the fallen nature of cinematic perception, Deleuze calls on philosophy to ‘open us up to the inhuman and the superhuman durations (durations which are inferior or superior to our own), to go beyond the human condition’. It is the cutting power of the eye that needs to be thought: the eye would be approached as a form of synthesizer, but as an analog rather than digital synthesizer. That is: the eye does not need to free itself from imposed distinctions to return to the flow of life, but should pursue ever finer cuts and distinctions, beyond its organic thresholds.

...(more)

Open Humanities Press

via Synthetic_zero

_______________________

Arthur Rothstein

1936

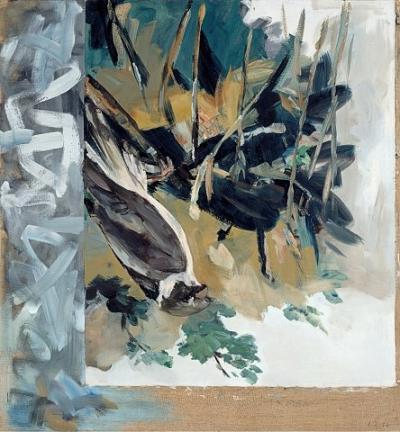

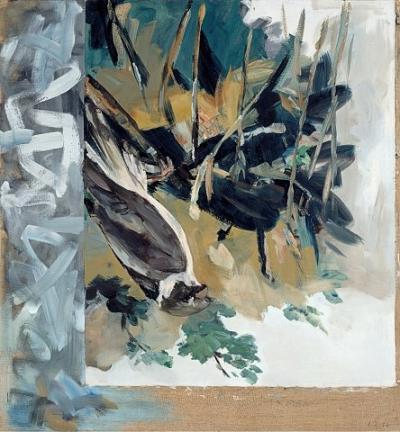

Ekely

Georg Baselitz

2004

_______________________

While leaf scatters across the path, the body

already braced for snow, in the head still

remains of summer: that evening we sat

at a table outside talking and addressed

the fleshpots, the owls

made the night a spectacle.

We could not see them but heard their

calls cross through the dark to

no one in particular. Airy response

came from far and seemingly higher.

We imitated them, would have liked

for a moment to be invisible too, waiting

for an answer that surely should come. But we

sat much lower, almost lightheartedly laughed and drank

our shard- and bottle-bliss together.

Hester Knibbe

translated by Jacquelyn Pope

On Translating Hester Knibbe

Jacquelyn Pope

(....)

Knibbe’s reticence is contemplative rather than stubborn; actions are observed rather than explained. Repetition of the quotidian often features in her poems, as if a story is being repeated to be made to come true, or as if events are being retraced to be undone. Time is always slipping past, and change is both constant and inescapable. It is the threat of change, the moment of change, the consequences of change that Hester Knibbe tries to grasp and shape in her poetry. Additionally, there is an identification with things that are ruined or damaged or misunderstood—whether a mute statue or the human wrack left after the Flood. The bewilderment that is expressed in many of Hester Knibbe’s poems allows both the poet and the reader a chance to stall, to hover at the borderline between life and death, which are two sides, two halves—two illusions, perhaps.

...(more)

Hester Knibbe at Poetry International and the Poetry Foundation_______________________

Adler

1977

Georg Baselitz

b. Jan 23, 1938

_______________________

"This lush background mythology of gene-selfishness supplies the teleological jam that is always needed to make a thin scientific story go down. And the confident certainty of finding evolutionary functions for everything provides it with a plausible background. In fact, as many people have pointed out, if you try to sling out Nature – or indeed the whole idea of Nature – through the door, she always comes quietly back down the chimney. And this may leave you worse off than you were before."

The Mythology of Selfishness

Mary Midgley

(....)

The trouble is that theorists who think natural selection can only work by cut-throat competition between individuals pursue that pattern obsessively, without glancing at the social phenomena they are supposed to be explaining. ... Though these scholars presumably know, like the rest of us, that a direct wish for particular kinds of deal with other people constantly determines our social activities, they still believe that, behind this screen, there lie hidden the real causes, elements of evolutionary advantage which affect ourselves alone. However hard that advantage may be to find – however little evidence there may be that could possibly reveal it – it is still the real McCoy.

This preference for supposed hidden causes over obvious ones is surely not a parsimonious way of thinking and neither, as it happens, is it Darwinian.(....)

Of course it is never easy to accept the role that the thoughts and feelings of our own parents – and indeed of everybody else’s – on similar occasions have played in making things be as they are now. Yet we know that these thoughts and feelings, not only then but throughout their lives, have indeed had this sort of importance. Our own thoughts and feelings – the constant flow of inner activity by which we respond to the life around us – also affect the world as well as our outward actions. This thought is so frightening that scholars will often go to any lengths to avoid it, which is why that ludicrous doctrine epiphenomenalism still has supporters, and why people spend so much more of their time on sociological statistics, neurological details and speculation about evolutionary function than on studying motive.

Thus the picture of natural selection which was shaped around Darwin’s main proposals used only two sombre colours – black for death and white for survival. Nature appeared in it only as an obsessive accountant, spectacles on nose and ledger in hand, testing every action in those terms and destroying the failures. Any trait still appearing in the world was deemed to have passed her audit in some distinct, discoverable way which constituted its evolutionary function.

This figure of Nature is, of course, quite unlike the sort of nature that we actually find at work in the animal and vegetable world, where it is notoriously a cornucopia, a wildly lavish scatterer of endless seeds and young, a generous, profuse, imprudent source of new life. And when we consider our own motives, we see that this vegetatious figure is a far better likeness of the kind of nature that animates us inwardly. Life for us is not just the absence of death. Life consists of endless crowded wishes, fears and activities, all primed by their own immediate aims and interests, not by long-term prudence. Like other conscious creatures we usually take action because we want to, and if our nature did not provide us with many vigorous wants we could not act at all.

...(more)

_______________________

The Hawk

Georg Baselitz

1971

_______________________

The library is where the cursed children hid.

Nietzsche And The Burbs>

The library is where the cursed children hid. The library is where the mutant children fled, every morning break, every lunch-time. Children changed into something monstrous. Children betrayed by their own bodies. Children watching themselves transformed, day by day…

Children of strange gods. There was a veritable freak-show in the library. A cabinet of human curiosities. Obscure ailments. Deformations unknown to science. Like some remote inbred tribe …

What mad scientist was let loose here? Evolutionary experiments. Wild deformations. Mutations almost glorious. As though designed by some drunk god. By some King-Ludwig-of-Bavaria God …

...(more)

_______________________

45.3 The League of the Homeland-evicted. The League of the World-evicted remains to be called into existence.

Celan the Aphorist

Pierre Joris jacket2

(....)

Except for two essays and one prose piece (Conversation in the Mountain), Celan did not publish anything beyond his poems and translations. But he did leave a rich trove of aphorisms, paradoxes, sketches, and short narrative & topical fragments (often returning, sometimes openly, sometimes in more veiled terms, to questions of Jewishness, of politics, of the mistreatment that befell him via the Goll affair). All these are fascinating as they are not only a pleasure to read qua writing, but also because they help throw light on a complex, profoundly private & and often secretive man. Be that as it may, for me maybe the most useful of this work is a range of reflections, just as short & pithy, on poetry & poetics.

...(more)

_______________________

The Archaeologist

Hester Knibbe

Translated by Jacquelyn Pope

In one who doesn’t speak the story petrifies,

gets stumbled over, causes hurt. Then,

says the man who should know about the past, then

is a word you need to learn now. Then

lived lives had has

a name a body, sacrificial hands

so god might help us. Feel with your hands and feet

back along these countless steps and hear

the incessant bloodrush, its dark red

presence. That was what the man insisted,

in so many words, pointing to the ornate

temple corridor, an altar

conjured at its vanishing point.

_______________________

Folkdance Melancholia

Georg Baselitz

1989

_______________________

Schrödinger's Cat

Ursula K. Le Guin

(....)

A cat has arrived interrupting my narrative. It is a striped yellow tom with white chest and paws. He has long whiskers and yellow eyes. I never noticed before that cats had whiskers above their eyes; is that normal? There is no way to tell. As he has gone to sleep on my knee, I shall proceed.

Where?

Nowhere, evidently. Yet the impulse to narrate remains. Many things are not worth doing, but almost anything is worth telling. In any case, I have a severe congenital case of Ethica laboris puritanica,1 or Adam's Disease. It is incurable except by total decapitation. I even like to dream when asleep, and to try and recall my dreams: it assures me that I haven't wasted seven or eight hours just lying there. Now here I am, lying, here. Hard at it.

(....)

The yellow cat, who may have belonged to the couple that broke up, is dreaming. His paws twitch now and then, and once he makes a small, suppressed remark with his mouth shut. I wonder what cats dream of, and to whom he was speaking just then. Cats seldom waste words. They are quiet beasts. They keep their counsel, they reflect. They reflect all day, and at night their eyes reflect. Overbred Siamese cats may be as noisy as little dogs, and then people say, "They're talking," but the noise is farther from speech than is the deep silence of the hound or tabby. All this cat can say is meow, but maybe in his silences he will suggest to me what it is that I have lost, what I am grieving for. I have a feeling that he knows. That's why he came here. Cats look out for Number One.

...(more)

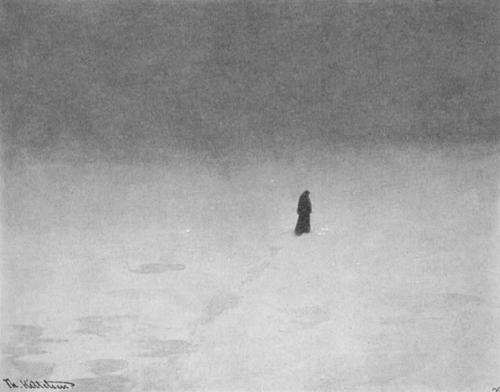

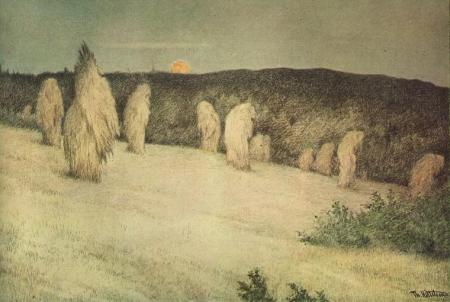

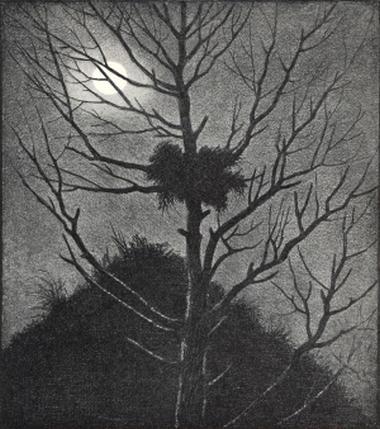

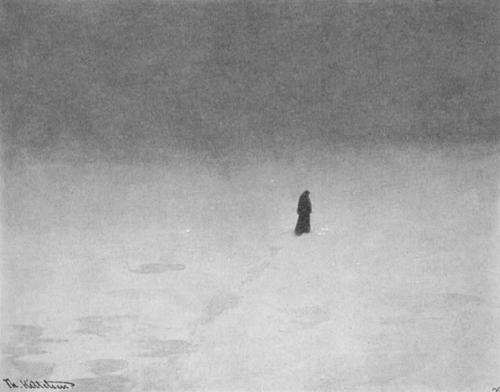

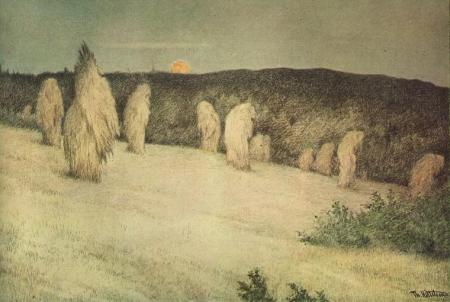

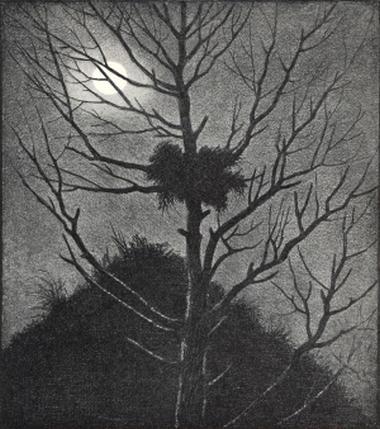

Theodor Kittelsen

d. Jan 21, 1914

_______________________

Antonio Gamoneda and the ontology of disappearance

A review of 'Description of the Lie' and 'Gravestones'

Jose-Luis Moctezuma

jacket2

Rust is the color of disappearance, the deintensification of metallic solidity. Seen in a different slant of light, rust produces a reintensification of color in the meeting of iron and oxygen, the proliferation of autumn in a congeries of breath, moisture, and steel. On the tongue rust acquires a taste: the bitterness of a disappearance, an evaporation that leaves behind the strange piquancy of material erosion. In Antonio Gamoneda’s Description of the Lie, rust invokes the beginning of a precipitous, painful knowledge, a forgetting that paradoxically initiates a splintering of presence into prismatic refractions that call attention to time’s invisible phenomena:

Rust alighted on my tongue with the taste of a disappearance.

Forgetting penetrated my tongue and I had no recourse but to forget,

and I accepted no value other than impossibility.

Rust in this sense leaves a taste of forgetting, or the sight of “a calcified boat in a country from which the sea has receded,” leaving only the impossibility of a sea, a lost remembrance contained in the sight of cuttlefish bones and striated canyon walls, a place evidenced by an illegibility of ruins. To paraphrase a Deleuzian maxim, the pursuit of the impossible occasions a new set of possibles, new forms of description. Yet taste and sight do not predominate in Description of the Lie so much as does aurality. Absence, after all, is articulated by the optical “lack of many a thing … sought,” a remembrance of things past which, in Shakespeare’s original formulation, “drowns an eye” (in tears, but also in a cognitive blindness) and becomes absorbed in sonic traces at the “expense of many a vanished sight.” Gamoneda does not see (he cannot see what is no longer there), but he listens:

I listened to the surrendering of my bones being deposited in rest,

I listened to the flight of insects and the retraction of the shadow

on entering what was left of me;

I listened until truth ceased to exist in the space or in my spirit,

and I was unable to resist the perfection of silence. ...(more)

_______________________

Theodor Kittelsen

_______________________

Faceless Book

Lauren Berlant

Today I introduced Facebook to someone older than me and had a long conversation about what the point of networking amongst “friends” is. The person was so skeptical because to her stranger and distance-shaped intimacies are diminished forms of real intimacy. To her, real intimacy is a relation that requires the fortitude and porousness of a serious, emotionally-laden, accretion of mutual experience. Her intimacies are spaces of permission not only for recognition but for the right to be seriously inconvenient, to demand, and to need. It presumes face to faceness, but even more profoundly, flesh to fleshness. But on Facebook one can always skim, or not log in.

My version of this distinction is different of course, and sees more overlap than difference among types of attachment. The stretched-out intimacies are important and really matter, but they are more shaped by the phantasmatic dimension of recognition and reciprocity–it is easier to hide inattention, disagreement, disparity, aversion. On the other hand it’s easier to focus on what’s great in that genre of intimacy and to let the other stuff not matter. There’s less likely collateral damage in mediated or stranger intimacies. While the more conventional kinds of intimacy foreground the immediate and the demanding, are more atmospheric and singular, enable others’ memories to have the ethical density of knowledge about one that is truer than what one carries around, and involve many more opportunities for losing one’s bearings. The latter takes off from a Cavellian thought about love–love as returning to the scene of coordinating lives, synchronizing being–but synchrony can be spread more capaciously and meaningfully amongst a variety of attachments. Still, I think all kinds of emotional dependency and sustenance can flourish amongst people who only meet each other at one or a few points on the grid of the field of their life.

(....)

I sense that Facebook is about calibrating the difficulty of knowing the importance of the ordinary event. People are trying there to eventalize the mood, the inclination, the thing that just happened–the episodic nature of existence.So and so is in a mood right now.So and so likes this kind of thing right now; and just went here and there. This is how they felt about it. It’s not in the idiom of the great encounter or the great passion, it’s the lightness and play of the poke. There’s always a potential but not a demand for more.

Here is how so and so has shown up to life. Can you show up too, for a sec?

...(more)

_______________________

Theodor Kittelsen

_______________________

Un-Hearing

Michael Kinnucan

hypocrite reader

(....)

4.

To be irritable is to be attuned to the way any effort of attention relies on a thousand inattentions: the space cleared for contemplation is cleared by forgetting and ignoring every other thing. It’s insane what a person can not-hear: I was once told that they have to change the ambulance siren sounds in big cities every four or five years, because people get used to them and stop hearing them. In some sense the ability to understand speech entails un-hearing what it sounds like: rhythms and patterns clearly recognizable in a language you don’t know disappear as you learn the language and begin to hear “past” the sound into its meaning. They come as a surprise when poetry awakens them again.

Irritability is the incapacity for a necessary form of inattention; noise is its proper object, since noise is simply the sound you’re not listening for, the sound you’re trying not to hear.

5.

The need for not-hearing reminds me of Nietzsche’s encomium to another sort of negative capability: forgetting. In a beautiful passage in On the Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche shows how necessary such negative capability is: the “breeding of a creature who can make promises,” he observes, is all the more remarkable because, while to promise is to (promise to) remember, humans can be present, to themselves and to the world, only through forgetting. If the mind is, in the old Platonic metaphor, a wax tablet, forgetting is the heat that melts it smooth, preparing the way for new inscriptions. Anything, even dead matter, can take a mark: you can engrave a record of the past into cold stone. What makes a mind is its capacity for constant erasure. Memory comes later, and only on the basis of forgetting.

For Nietzsche, the inability to forget was the formula for madness: the man who enters the marketplace carrying a lamp to announce that “God is dead, and we have killed him” is a madman because he doesn’t know another sun has risen, because he hasn’t yet forgotten the night of the world. This formula for madness was prescient, or influential: for Freud, too, madness would be unforgetting. And what else is the “trauma” that obsesses our own culture than a pathological memorization?

Irritability is a related kind of madness: the inability, not to forget, but to ignore.

...(more)

_______________________

Francis Picabia

b/ Jan 22, 1879

_______________________

In the Tumult of Translation

Tim Parks

(....)

We should say at the outset that while Levi liked to describe himself as a writer with a determinedly plain style, the truth is rather different. Often a direct, speaking voice shifts between the colloquial and the literary, the ironically highfalutin and the grittily scientific. It’s true that there are rarely serious problems of comprehension, but the exact nature of the register, which is to say the manner in which the author addresses us, the relationship into which he draws us, is a complex and highly mobile animal. It is here that the translator is put to the test.

...(more)

_______________________

Theodor Kittelsen

photo - mw

_______________________

Blue Poles (after Jackson Pollock)

Caitríona O’Reilly

From Geis by Caitríona O’Reilly

Freedom is a prison for the representative savant

addled on bath-tub gin and with retinas inflamed

from too long staring into the Arizona sun

or into red dirt which acknowledges no master

but the attrition of desert winds and melt-water.

Is that why you cast such desperate lariats

across space, repeatedly anticipating the fall

into disillusion, the sine wave skewered

by the oscilloscope, the mirror’s hairline fracture?

The West was won and there was nowhere left to go

so you vanished into a dream of perpetual motion

knowing that once to touch the surface

was to break the spell, but that while the colours hung

on the air an instant, there was no such thing

as the pushy midwife, the veiled mother in the photograph,

the rich woman’s bleated blandishments.

Tracing the drunken white line at midnight on the highway,

you were too far gone to contemplate return,

like Crowhurst aboard the Electron; not meaning

to go to sea, but drawing about you

such a field of force that there was nothing left to do

but plant blue poles among the spindrift and iron filings

and step, clutching your brass chronometer,

clean off the deck and into the sky

where a lens rose to meet you like a terrifying eye.

Caitríona O'Reilly on "Blue Poles"

It would be nice if poetry wrote itself. Occasionally, when I was younger, I had the feeling that it did: poems were likely to be written quickly, in a flush of enthusiasm it pleased (flattered) me to call inspiration. Sometimes so quickly that in some kind of weird hippocampal storm I had the feeling I was remembering something and copying it down rather than making it up as I went along. Those were the best times. As one gets older the realisation dawns that the hotline to Parnassus was little more than the excited firing of youthful synapses and that the process happened quickly because one’s brain was younger. Idleness was also a factor. Now it feels more like hanging onto a rising balloon, or chasing after a snatch of melody just on the edge of earshot. I’m referring to the initial draft only here: the spit-and-polish stage can take anything from days to months to years.

I had got it into my head, after reading a biography of the American painter Jackson Pollock, that there were uncanny similarities between his ‘predicament’ and that of the English yachtsman Donald Crowhurst. If I had stopped to think about how irrational this comparison was I would never have attempted to write a poem about it, but the initial enthusiasm for a poem can feel a bit like an ill-advised infatuation: in your heart of hearts you know it’s a questionable idea, but you can’t help hoping it might all turn out for the best anyway.

...(more)

“It felt like a breaking of some taboo I’d placed myself under”: Caitríona O’Reilly on writing GeisWake: Up to Poetry

Airborne

Lucy Collins reviews Geis, by Caitríona O'Reilly dublin review of books

Geis is a collection concerned with the spaces between – between people, between words. The awareness of emptiness, evoked in so many of the poems, prompts contemplation: here meaning is created, not merely represented, as we sense the poet resuming a process of reflection after a lengthy absence. Past and future are held in a delicate balance throughout the volume.

...(more)

via the page

Geis

Caitríona O'Reilly

bloodaxe books

Caitríona O'Reilly at the Poetry Foundation

_______________________

Jean Delville

b. January 19, 1867

_______________________

a transformed inwardness of time

Maurice Blanchot -- The Experience of Proust

quoted at flowerville

We see that what is given to him at that instant is not only the assurance of his calling, the affirmation of his gifts, but also the very essence of literature-he has touched it, experienced it in its pure state, by experiencing the transformation of time into an imaginary space (the space unique to images), in that moving absence, without events to hide it, without presence to obstruct it, in this emptiness always in the process of becoming: that remoteness and distance that make up the milieu and the principle of metamorphoses and of what Proust calls metaphors. ...(more)

_______________________

A General Theory of Oblivion by Jose Eduardo Agualusa

Review by Dustin Illingworth

quarterly conversation

Early on in Jose Eduardo Agualusa’s A General Theory of Oblivion, the narrator offers this bit of difficult wisdom: “Any one of us, over the course of our lives, can know many different existences. . . . Not many, however, are given the opportunity to wear a different skin.” It’s an implied celebration of literature, one that weaves itself into the fabric of Oblivion. Locked as we are within a given body, temperament, and time, literature can transport us, can transmute textual experience into an expansion of inwardness, an amplification of consciousness. The best books—which Agualusa’s charmingly melancholic novel approaches—haunt us and, indeed, cover us like “a different skin.” Here, however, writing is even more than that: for Ludo, the agoraphobic and mysteriously damaged protagonist, writing is a matter of life and death, a story she scrawls on the walls of her home with charcoal. Fragmented and densely layered, Oblivion unfolds within the possibility—and the tension—inherent between writing and identity, text and meaning, story and life.

...(more)

_______________________

Fenced in Child

Vrederdorp

1967

Peter Magubane

b. January 18, 1932

_______________________

Larval Terror and the Digital Darkside

Nandita Biswas Mellamphy

(....)

... Larval terror’ is the feeling of ontological and epistemological insecurity that results when we are confronted with the infinite recursivity of the larval condition. When viewed within the context of globe-girdling and ubiquitous digital information-networks, what is terrifying about this reality of advancing ever-masked (especially in digitally mediated societies such as our own) is the ease by which its banality and ubiquity—its ongoing and widespread everydayness—can be weaponized. Even more terrifying than the realization that every mask hides another mask is the weaponization of insecurity that results from this larval feeling of terror. A passage from Philip K Dick’s classic Scanner Darkly (1977) is telling in this regard:

One of the most effective forms of industrial or military sabotage limits itself to damage that can never be thoroughly proven—or even proven at all— to be anything deliberate. It is like an invisible political movement; perhaps it isn’t there at all. If a bomb is wired to a car’s ignition, then obviously there is an enemy; if a public building or a political headquarters is blown up, then there is a political enemy. But if an accident, or a series of accidents, occurs, if equipment merely fails to function, if it appears faulty, especially in a slow fashion, over a period of natural time, with numerous small failures and misfirings—then the victim, whether a person or a party or a country, can never marshal itself to defend itself.

Larval terrorism weaponizes the larval capacity to use and switch masks, to play upon the play of dissimulation (while advancing upon the ‘stage of the world’) in order to go undetected—mismasked, mis- /un-named, hence ultimately unidentified—by one’s opponents. This is the second important point I want to highlight: one of the main contributions to larval terror today has been from governments (in collusion with supporting commercial enterprises) that, in the name of fighting the larval or ‘asymmetric enemy’, are entirely invested in the politics of fear and in heightening popular paranoia for the purposes of actualizing so-called ‘counter-terrorist’ measures that include large-scale, indiscriminate, covert and illegal surveillance of individuals and populations. The ‘asymmetric enemy,’ an enemy that cannot be readily or easily distinguished from ‘friend,’ is not just camouflaged, but is said to take on many forms. The ‘asymmetric enemy’ as ‘larval terrorist’ is not an ‘individual’ at all, but is best understood as a network of larval forces that is able to utilize and thus weaponize its transitory, polymorphous, and emergent attributes. The concept of ‘asymmetric enemy’ thus becomes a weaponization of the larval and polymorphous nature of identity itself, and has been used by insurgents, governments and corporations to justify their own, often covert, interests.

...(more)

E-International Relations

via Deterritorial Investigations Unit

_______________________

Welcoming the étrangère

Marci Vogel

jacket2

Wise navigator of translation, Paul Ricoeur identifies the experience of crossing over languages as both challenge and source of happiness. Equipoise and equanimity arrive via linguistic hospitality, that sheltered inlet "where the pleasure of dwelling in the other's language is balanced by the pleasure of receiving the foreign word at home, in one's own welcoming house." We set anchor there. Low tide, walk through shallow waters to shore. We arrive someplace entirely new — and also strangely familiar.

Or maybe we are the ones to hear the knock on the door.

The étrangère is both (and possibly at once) the not-from-here and the one inside the house. She is both (and possibly at once) someone else and the one glimpsed in the glass. She is Stranger, Foreigner, Other. And all of the above, in turn.

...(more)

_______________________

In Conversation with Fuat Sevimay, Turkish translator of Finnegans Wake

Aymptote

(....)

When you attempt to translate—or interpret—Finnegans Wake, you have to be aware that, inevitably, you will lose some points at the source and you have to gain some others in your target language. But you don’t have a choice and cannot miss the motifs since they are the cues for an extremely complex novel. The reader—if careful enough, determined and willing—can follow a protagonist or a repeated event through motifs. Readers could feel free to pay or not to pay enough attention, but as a translator, I must and do pay my utmost attention to motifs.

DP & SJ: What did you find to be the most difficult aspect to grapple with in your translation of the Wake?

FS: Most probably the Joycean words. Let’s think about it. He, the master builder, says something in so-called English but the same word indicates something else if you read half of it in Gaelic and the rest in Latin. You have to correspond all three of them and if, in a way you succeed—bad news—that’s not enough. Your word has to get the right syntax within the sentence and—worse news—it still may not be enough. You also have to catch the phonetic. Oh, I’m tired. But Finnegans Wake deserves it all.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Thoughts on Osip Mandelstam's Birthday

Pierre Joris

jacket2

A birthday that happened 125 years ago today... & still I can't find an English translation that satisfies me completely. Most of them feel more or less flat, with Mandelstam turned into a most salon-fähig lyrical poet of medium to low intensity. (Oddly enough this is true especially of those translations extolled by Joseph Brodsky, someone who should have know, as he was a native Russian who wound up writing in English, but I guess my judgment here may be tainted as I find Brodsky's English work très fade...) Clarence Brown's versions may still be the least problematic, but I can't wait for John High's complete Mandelstam (his collaborative versions with Matvei Yankelevich are lovely indeed) — John, we need these! I have not yet been able to get Andrew Davis' just published versions of the Voronezh Notebooks, out earlier this month from NYRB Poets. Way back when — late sixties — my Bard College co-student Bruce McClelland published a translation of Tristia, which I found useful and quite readable back then. I wish he had continued to work on Mandelstam, but unhappily his interests wandered elsewhere.

What I have come to realize over the years is that the translation of truly major poets (of which Mandelstam is one) cannot be approached as an occasional occupation, i.e. as either a quick way to learn the tricks of a master (translating is the closest reading you can give a poem, so indeed the most useful activity in learning to write, as I have been telling my students for many years) or as a way to locate possibilities of publication by associating one's (as yet unknown) name with that of a well-known poet (though that too can be useful for a serious young poet). Looking at such multiple scatter-shot translations, in magazines, chapbooks or single volumes of major poets by numerous translators, gives me at times the impression of a haphazard gaggle of young (or not so young) poet-translators cutting their teeth by feeding on the giant corpse of a dead beached whale. At the same time, I'd like to add, having several translations of a great poem can also be of good comparative use.

...(more)

Andrew Wyeth

d. Jan. 16, 2009

_______________________

from

Draft 74: Wanderer

Rachel Blau DuPlessis

Book I

This the place where hopes had left

their traces, stark in storm,

stoked in “astonishing nights, foreigners among humans,”

whose eye thirl, window whorl they Open Wide

seeking wordth and depth,

if ever, given

ques and querl, this wordth and depth could be,

and want to speak to sight, to sigh and

rage, not for that hour, nor for that place

yet nowhere

unembellished by some trace,

documentary (that and more), witnessing (that

many more) and witless, hurtful, “jesting air”—en-

joined, frozen in mo ti on but not to crumble, rather

stand. This has to stand, inside, longside as

It; and yet is split, is double split, in impulse, turn, and goal.

Still somehow moves (un-

sanctioned? leaden?) fated, stripped,

by road or pathway or through trackless field,

Up hill or down.

What hope then for the wanderer?

Yet and Yet and Yet in place.

Aura of words in a storm face.

There are plenty of reasons to wonder.

.....................................................

'The page is slowly turning black'

Rachel Blau DuPlessis’s 'Torques: Drafts 58–76'

Harriet Tarlo

jacket2

I am always one volume behind in Rachel DuPlessis’s Drafts. Yet, I have been a loyal reader and realize to my surprise that she has been writing them/I have been reading them for the best part of twenty-five years now. We, author and reader, have been “strained companions” in the creation of this work. Often, throughout this essay, I refer to the “writer/reader” of the work to demonstrate the shared enterprise that is an intrinsic part of being in Drafts. Drafts will not yield to you without attention, not just to the individual piece, but to a kind of active, physical juggling, the moving of the finger along the lines of the grid of poems, the reading back and forth within the folds of at least three books. Drafts are a pleasure and a weighty pain as they roll on remorselessly, demanding that you keep up, keep faith and care, that you follow through, follow back and forth, forth and back, reading notes, seeking intertexts, being in the process. We are as battered and elated as DuPlessis herself must be, by the end of each Draft, each volume, each enfolded reading. The poet is aware of this as she challenges, berates and encourages us in the journey. “Are you Ready? are you composed? / Can you go a third Vertiginous road?” she asks with a mocking rather jaunty half-rhyme at the beginning of “Draft 73: Vertigo” (and of course the capitalization of “Ready” makes us see “read,” asks if we are read-worthy of the journey). The whole project is vertiginous in its refusal to cease or fix. I think that my surprise at how long it has all been going on is due not just to the natural human amazement at how time passes, but also to how these pieces still feel so fresh and innovative, so contemporaneous, in their individuality and their structure as a long, ever-changing poem.

...(more)

Rachel Blau DuPlessis at EPC and the Poetry Foundation

_______________________

White, over Red and Black

(circa 1964)

Tony Tuckson

b. January 18, 1921

_______________________

On the discrepancy between objects and things. An ecological approach.

Fernando Domínguez Rubio

Journal of Material Culture (Forthcoming)

Abstract

The aim of this article is to develop a different approach to the study of the material world, one that takes seriously the seemingly banal fact that things are constantly falling out of place. Taking this fact seriously, the article argues, requires us to think about the material world not in terms of "objects", but ecologically, that is, in terms of the processes and conditions under which certain "things" come to be differentiated and identified as particular kinds of "objects" endowed with particular forms of meaning, value and power. The article demonstrates the purchase of this ecological approach through the example of the Mona Lisa. It does so by exploring the rather extraordinary processes of containment and maintenance that are required to keep the Mona Lisa legible as an art object over time.

(....)What I want to propose in this article is an approach that takes all these processes into account. In other words, an approach that takes seriously the seemingly banal fact that things are constantly falling out of place. Taking this fact seriously, I argue, opens up an entirely different approach, one that takes temporality, fragility and change as the starting points of our enquiry. This, I argue, requires us to think ecologically , that is, not in terms of objects, but in terms of the discursive and material conditions and practices — what I will call the oikos —, under which certain things can be rendered possible, effective and reproducible as objects endowed with particular kinds of value, meaning, and power. To start making this argument, let me return for a moment to Gell, and specifically to one of the objects he wrote about: the prow-boards that Trobrianders place in their Kula canoes.

(....)

_______________________

Imatra in Winter

1893

Akseli Gallen-Kallela

1865 - 1931

_______________________

The Aesthetics of Nostalgia: Ashbery's Cornell-like Poems

Andrew Michael Field

Joseph Cornell and John Ashbery are united by an aesthetics of nostalgia. Each artist is enchanted and disturbed by the past, and they consequently invest their poems with a longing which can only be called nostalgic. They are nostalgic because time is passing, like a ribbon one is chasing that constantly eludes one’s grip or grasp; and because time is passing, ultimately leading to death, Cornell and Ashbery are possessed by a homesickness, a nostalgia, an ironic (because the past is out of reach, and therefore inescapably remote) sentimentality (because the past is out of reach, and therefore a springboard for subjective fantasy and reverie about the past). It is nostalgia – the awareness, the longing – that brings into being Ashbery’s wondrously funny and profound constructions – as if through their ceaselessly imaginative imagery they might blot out the homesickness at the heart of their issuing. (And it is nostalgia that propels Cornell through the book stalls of Manhattan, looking for objects that will hypnotize with their lyrical evocativeness.)

Reading Ashbery, like the experience of living, is constantly analogous to this notion of a game being played, although with rules we are not intended to wholly understand. And this experience breeds not only frustration, but also, in a way, a new strategy of and for reading. For in reading an Ashbery poem, like looking at a Cornell box, the goal is not mastery. The goal is, rather, enchantment and absorption. And enchantment or absorption do not work in a linear or logical way, but instead catch us unawares, compelling us to open our eyes to moments we’d never dreamed possible. I experience this personally when I read Ashbery’s “The Wave,” full of instances that continue to shock me with their novelty and originality. Ashbery writes,

One idea is enough to organize a life and project it

Into unusual but viable forms, but many ideas merely

Lead one thither into a morass of their own good intentions.

Think how many the average person has during the course of a day, or night,

So that they become a luminous backdrop to ever-repeated

Gestures, having no life of their own, but only echoing

The suspicions of their possessor. It’s fun to scratch around

And maybe come up with something. But for the tender blur

Of the setting to mean something, words must be ejected bodily,

A certain crispness be avoided in favor of a density

Of strutted opinion doomed to wilt in oblivion: not too linear

Nor yet too puffed and remote. Then the advantage of

Sinking in oneself, crashing through the skylight of one’s own

Received opinions redirects the maze, setting up significant

Erections of its own at chosen corners, like gibbets,

And through this the mesmerizing plan of the landscape becomes,

At last, apparent.

...(more)

_______________________

"Chocholy"

1898

Stanislaw Wyspianski

1869 - 1907

_______________________

“Once the object has beneath the brooding look of Melancholy become allegorical, once life has flowed out of it, the object itself remains behind, dead, yet preserved for all eternity; it lies before the allegorist, given over to him utterly, for good or ill. In other words, the object itself is henceforth incapable of projecting any meaning on its own; it can only take on that meaning which the allegorist wishes to lend it. He instills it with his own meaning, himself descends to inhabit it: and this must be understood not psychologically but in an ontological sense. In his hands the thing in question becomes something else, speaks of something else, becomes for him the key to some real of hidden knowledge, as whose emblem he honors it. This is what constitutes the nature of allegory as script.”

— Walter Benjamin quoted in Fredric Jameson “Walter Benjamin, or Nostalgia” (1970)

via The Great Leap Sideways

|