|

Lyonel Feininger

1871 - 1956

_______________________

only the crossing counts

C. D. Wright

January 6, 1949–January 12, 2016

It's not how we leave one's life. How go off

the air. You never know do you. You think you're ready

for anything; then it happens, and you're not. You're really

not. The genesis of an ending, nothing

but a feeling, a slow movement, the dusting

of furniture with a remnant of the revenant's shirt.

Seeing the candles sink in their sockets; we turn

away, yet the music never quits. The fire kisses our face.

O phthsis, o lotharian dead eye, no longer

will you gaze on the baize of the billiard table. No more

shooting butter dishes out of the sky. Scattering light.

Between snatches of poetry and penitence you left

the brumal wood of men and women. Snow drove

the butterflies home. You must know

how it goes, known all along what to expect,

sooner or later … the faded cadence of anonymity.

Frankly, my dear, frankly, my dear, frankly

_______________________

Bird Cloud

Lyonel Feininger

1926

_______________________

C.D. Wright: The Obstacle Worth Engaging

The poet C.D. Wright discusses book-length works, the political in art, and more.

guernica

Poet C.D. Wright’s book Cooling Time: An American Poetry Vigil is just what its subtitle says it is: Wright keeps watch over a corner of literature that is enduring but under-bankrolled, even under-read. Stitching together epistle, memoir, essay, and verse—an approach emblematic of her recent work—she charts her own path to poetry and her evolution as a poet. She does the same for poets we wouldn’t likely know otherwise, scattering their often unassuming but attractive biographies among pithy musings from artists of all stripes—Thomas Merton, Gertrude Stein, and (more than once) Miles Davis. What results is an attempt not only to bear witness, but also to summon. Wright dubs one of Cooling Time’s epigraphs a “call to words,” and you could call the book the same: its author endeavors to make clear why one would choose a field as impractical as poetry; then she sells that choice hard.(....)

C.D. Wright: I have taught the long poem off and on for years. The more book-length poems I read and studied and taught the more interested I was in the possibilities in writing a poetry that applied formal and substantive options of narrative and non-narrative, lyric and non-lyric. I found many pleasures in this kind of writing. The long poem is as old as the art form.

I think a book-length poem stands about as good a chance as a collection of individual poems in reaching its field of ears. This does not mean I have not found some of them too daunting to read all the way through, but it would seem there ought to be some ambition on the writer’s part to create a work that would be “a read” all the way through. If not, all the pleasure belongs to the maker, and that in itself is something, an achievement.

...(more)

.....................................................

Looking for “one untranslatable song”:

C.D. Wright

on poetics, collaboration, American prisoners, and Frank Stanford

in conversation with Kent Johnson

(....)

As when learning a foreign language, the structure of your own becomes transparent; as Molière's character comes to understand he’s speaking prose — it hastened the development of my self-consciousness. I was forced to ask what was I doing, why was I doing it and what was I going to do about it. That Silliman sentence, “No one expects baseball players to comprehend the implications of their work.” It was time to re-examine, and still I lagged. My tempo has never been successfully urbanized.

Nevertheless, of all the Language Poets Silliman's express-line writing was and is the one that stuck to my ribs. It was so thingy, so specific, so formally radical, so hard-headed, yet witty, and now and then, in spite of itself, lyric. I liked his post-industrial music. I loved Ketjak and Tjanting and Paradise... And the reach — the compulsion to pull everything in. What attracted me most about the Language poets was their big-headed endeavor to overhaul the language. What most repelled me was, by my lights, their collective snobbishness, their utter absence of self-criticism and cock-suredness, which ran, I thought, directly contrary to their ambitions on behalf of the art itself.

...(more)

_______________________

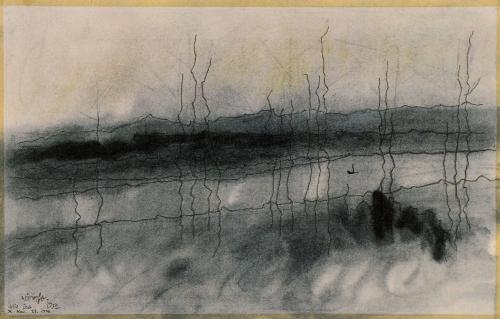

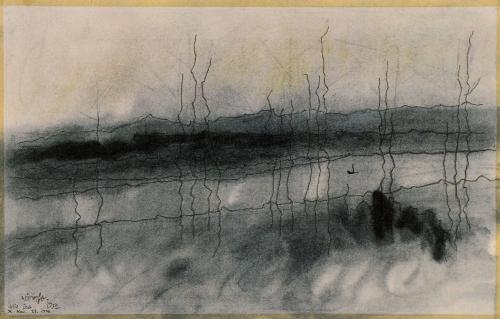

Mystic River

Lyonel Feininger

1951

_______________________

Floating Trees

C. D. Wright

a bed is left open to a mirror

a mirror gazes long and hard at a bed

light fingers the house with its own acoustics

one of them writes this down

one has paper

bed of swollen creeks and theories and coils

bed of eyes and leaky pens

much of the night the air touches arms

arms extend themselves to air

their torsos turning toward a roll

of sound: thunder

night of coon scat and vandalized headstones

night of deep kisses and catamenia

his face by this light: saurian

hers: ash like the tissue of a hornets’ nest

one scans the aisle of firs

the faint blue line of them

one looks out: sans serif

...(more)

_______________________

Windmill Near Usedom

Lyonel Feininger

1927

_______________________

All the girls said so

August Kleinzahler

london review of books

(....)

That ‘prosodic pattern’ would evolve into one of the significant poetic inventions of the 20th century; it was an eccentric, syncopated mash-up of traditional measures and contemporary vernacular energy, an American motley with Elizabethan genes. The Dream Song form – three six-line stanzas, with lines of varying length and no predictable rhyme scheme – is used by Berryman as a flexible variant on the sonnet. He needs this flexibility to accommodate the continually changing registers of voice, the sudden shifts of diction, and to allow him to keep so many balls in the air. He wrote a total of 385 Dream Songs over 13 years, beginning in 1955. It was a period in which his mental and physical condition deteriorated as a result of extreme alcohol abuse and the poems are nourished by that dissolution and the despair born of it, the best of them transmuting Berryman’s condition into something lambent and ludic. Their protagonist, Henry, a shape-shifting tragicomic clown, is Berryman himself behind a set of Poundian masks. What makes the sequence such a signal achievement is that it manages to be at once representative of the poetry of its time and a radical departure from it.

For what then seemed a lengthy spell, from the late 1950s well into the 1970s, the standard-bearers of American poetry were a group of manic depressive exhibitionists working largely, if not exclusively, in traditional metre and rhyme schemes, analysands all, and with self-inflating personae that always reminded me of those giant balloons of Mickey Mouse and Pluto associated with Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. They published and reviewed one another in journals like the Nation, Partisan Review, the Kenyon Review and Sewanee Review, with a good deal of auto-canonising. Robert Lowell, almost by default it seemed, was ceded pride of place, the ‘most important American poet now at work’. Lowell and Randall Jarrell, roommates at Kenyon College in the 1930s, and to a lesser extent Berryman too, were big on rating and ranking: the top three poets, the top three oyster houses or second-basemen, the three best Ibsen plays – they seemed especially to like the number three. How do they rate now? It all looks a bit different fifty years on - it always does - after all the theatrics and hyperventilating, the crack-ups, ECT, Pulitzers, heart attacks, suicides, obituaries, followed hard on by biographies, critical appraisals and reappraisals, canonisation and decanonisation.

...(more)

_______________________

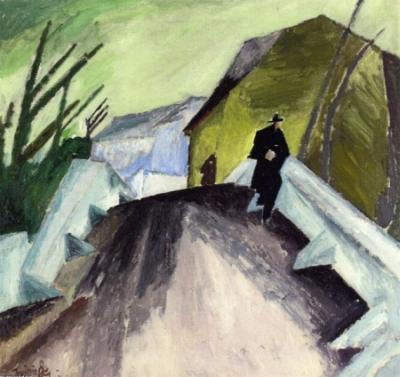

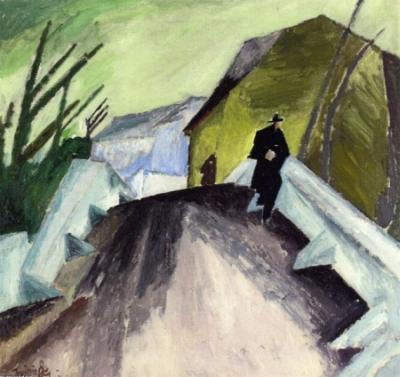

On the Bridge

(Ober-Weimar)

Lyonel Feininger

1913

_______________________

The Future After the End of the Economy

Franco Berardi Bifo

e-fllux (2011)

(....)

After the illusions of the new economy—spread by the wired neoliberal ideologists—and the deception of the dot-com crash, the beginning of the new century announced the coming collapse of the financial economy. Since September 2008 we know that, notwithstanding the financial virtualization of expansion, the end of capitalist growth is in sight. This will be a curse if social welfare is indeed dependent on the expansion of profits and if we are unable to redefine social needs and expectations. But it will be a blessing if we can distribute and share existing resources in an egalitarian way, and if we can shift our cultural expectations in a frugal direction, replacing the idea that pleasure depends on ever-growing consumption.

(....)

Only if we are able to disentangle the future (the perception of the future, the concept of the future, and the very production of the future) from the traps of growth and investment will we find a way out of the vicious subjugation of life, wealth, and pleasure to the financial abstraction of semiocapital. The key to this disentanglement can be found in a new form of wisdom: harmonizing with exhaustion.

Exhaustion is a cursed word in the frame of modern culture, which is based on the cult of energy and the cult of male aggressiveness. But energy is fading in the postmodern world for many reasons that are easy to detect. Demographic trends reveal that, as life expectancy increases and birth rate decreases, mankind as a whole is growing old. This process of general aging produces a sense of exhaustion, and what was once considered a blessing—increased life expectancy—may become a misfortune if the myth of energy is not restrained and replaced with a myth of solidarity and compassion.

Energy is fading also because basic physical resources such as oil are doomed to extinction or dramatic depletion. And energy is fading because competition is stupid in the age of the general intellect. The general intellect is not based on juvenile impulse and male aggressiveness, on fighting, winning, and appropriation. It is based on cooperation and sharing.

This is why the future is over. We are living in a space that is beyond the future. If we come to terms with this post-futuristic condition, we can renounce accumulation and growth and be happy sharing the wealth that comes from past industrial labor and present collective intelligence.

If we cannot do this, we are doomed to live in a century of violence, misery, and war.

...(more)

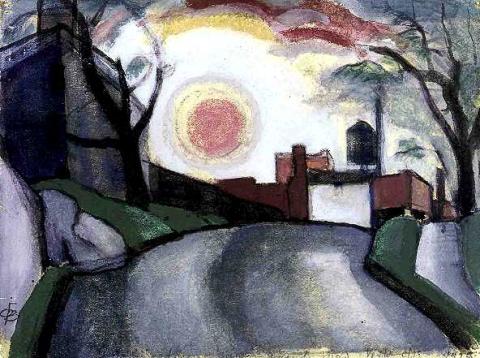

A Situation in Yellow

1933

Oscar Bluemner

1867 - 1938

_______________________

The Untranslatable: Triptych on a Sentence by Rey Chow

M. Munro

berfois

Strictly speaking, does not thought—or the act of thinking—always

have the capacity for operating like a foreign language?

Rey Chow

Philosophie dürfte man eigentlich nur dichten. Wittgenstein’s imperative translates, “very roughly,” “Philosophy ought really to be written only as poetry.” Yet how is one to approach that directive? How is one to read it—as poetry, or philosophy? If poetry, following Robert Frost, is, precisely, “what gets lost in translation,” how is one to place what’s proposed here? And where does that leave philosophy?

...(more)

_______________________

Philosophy Outside The Academy: a personal experience

Agent Swarm

(....)

... I have at times “left” philosophy, sometimes for many years, and when I come back to it, even in a not so inspiring academic lecture that I happen to sit in on, it is always with a feeling of coming home (even though I was trained in philosophy in Sydney Australia and I am now living in Nice France). Philosophy is my language.

As such, philosophy is an integral part of my sensibility, of my understanding of life, and of my life choices. My reading of Feyerabend helped me (and still helps me) understand my interactions with people and how to improve them. Due to reading Feyerabend I chose to move to France and to attend seminars by Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, Michel Serres, Jean-François Lyotard (al pluralists).

Deleuze and Serres have helped me understand my love-relations and live them better (joys and quarrels), my institutional positions, and my tastes in reading and writing. Foucault has helped me in understanding job-situations and other asymmetric encounters (as has Feyerabend). Reading Deleuze helped me choose my sporting activities (kung fu, tai chi) and to understand what is going on when I practice them and to approach them more deeply. Sometimes people ask me for advice, and I mix in fragments of Lyotard and Badiou. Philosophy for these thinkers is from the beginning, and at the deepest level, tied to processes of individuation and to creation or modulation of modes of life.

The thinkers I have named are part of my own “pocket pantheon”, and may not have the same impact others, but other pantheons probably produce similar experiences. They are only the tip of the iceberg. I could not have read them, and seen their relevance to my life, without having become familiar with a large amount of academic philosophy.

...(more)

_______________________

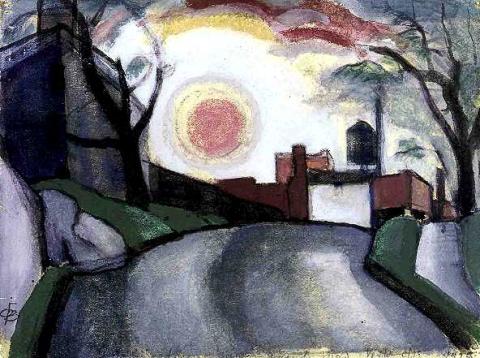

Hackensack River

Oscar Bluemner

ca. 1912

_______________________

Notes on Bowie

Brian Dillon

the dubllin review

1

I’m enthralled and embarrassed by him in ways that are probably possible only when you have loved too much and too soon. Not only am I mystified on discovering that some people my age or a little older are quite indifferent to David Bowie; I also feel much the same ache and anger when I hear him disparaged as I did thirty years ago. While I was taking notes for this essay a friend pointed to a newspaper article: a tedious columnist was claiming that, all brilliance and invention aside, Bowie has never written a song that truly moved anyone, still less consoled them in the wake, let’s say, of a bereavement. Surely this is true, said my friend. Really? You have no idea, I think – none.

And yet: the embarrassment. Not so much at the unengaging records that followed his decade or so of genius and are easily ignored, nor the silliness of this or that image or hubristic acting project. I’m embarrassed instead at a certain brittle grandiloquence, at the inflated thoughts he makes me think. Things like: in or around the summer of 1981, my consciousness changed for good. Or: David Bowie invented me, and he may well have invented you. And the questions he makes me ask, such as this: how much of who you are is still in thrall to images and ideas planted decades ago by someone who was not even sure who or what he wanted to be? Someone whose influence you shared with millions? Exaggerated, sentimental, adolescent questions. Middle-aged ones, too.

...(more)

_______________________

Sunrise

Oscar Bluemner

1925

_______________________

Franco Berardi: The Coming Civil War of the Planet

S.C. Hickman

(....)

The cognitariat is part of the problem, not its fix. Look at the state of the Left. All the books published, journals written, academics spreading their usual claptrap, students occupying little and less among the meaningless margins. Berardi seems to live pre 1968 as if the old 60’s Culture could be reignited in a new world of electronic hippiedom, flower children and communist propaganda alive and well in the broadcast lanes of our network marginal drift. Knowledge liberated or not is not going to change a thing. One could speak of change of consciousness all day, all night, but it is the same old tale that has yet to change anything. If raising consciousness could really effect change then one could stop writing tomorrow, for the best and greatest literature for that has already been written. Art, music, protest? All these old forms are defunct, passé, and have become parody or parodies in our age. In an age of Reality TV people support the fantasy of fantasies their parents only dreamed of. People no longer want Truth or truths, instead we live in the age of loss and forgetting. People want to forget the problems of the world, hide away in their virtual worlds of hyperplay, raves, travels…

Berardi speaks truth when he says “the future of Europe is held captive by the opposition between financial violence and national violence”. Ethnic, religious, political violence is and will remain an emerging aspect of the next centuries civil war for the planet’s resources. The empires battle for land, resources, and power while their people are kept in ignorance or ideological hell with mediatainment systems that promise freedom and give nothing but the complete degradation of fatalism.

As Berardi says in his closing statement: “Globalization has brought about the obliteration of modern universalism: capital flows freely everywhere and the labor market is globally unified, but this has not led to the free circulation of women and men, nor to the affirmation of universal reason in the world.” While the general intellect is absorbed into the “corporate kingdom of abstraction is depriving the living community of intelligence, understanding, and emotion”.

...(more)

The Coming Global Civil War: Is There Any Way Out?Franco Berardi e-flux

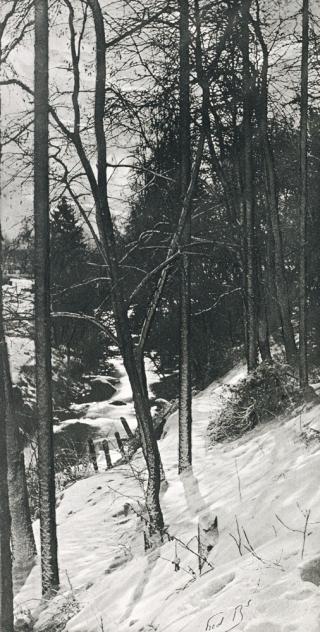

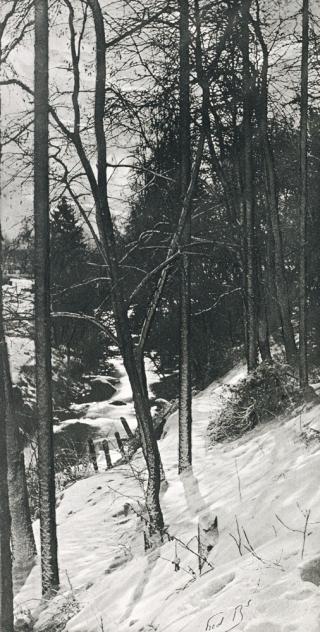

Nuit de janvier

Frederick Boissonnas

Quatrième Année Salon de Photographie - 1897

_______________________

Poems

Bohuslav Reynek

Translated by Justin Quinn

tower poetry

Sticks in a Fence

The fence’s sticks, like strings subdued,

forlorn, and tacked down in a row.

There’s much you know of solitude.

Of wings, what do you know?

The straws of wheat don’t miss the ears

that heard and were heard too.

You’re faceless. Unastonished. Fears –

this lattermath chilled through.

These lean, long years your bony shanks,

waiting, locked in leas.

Burls in palms, heels in mud-banks.

You don’t have any knees.

...(more)

_______________________

Esteban Vicente

d. Jan 10, 2001

_______________________

Gone today

Justin Quinn and the gift of the translator

Walt Hunter

jacket2

In his late work On Translation (2005), the French phenomenologist and literary theorist Paul Ricoeur brings together his lifelong investigations into ethics with a re-reading of Walter Benjamin's "The Task of the Translator" (1923). Ricoeur theorizes translation as a "correspondence without adequacy," urging us to give up on the idea of a perfect translation:

And it is this mourning for the absolute translation that produces the happiness associated with translating. The happiness associated with translating is a gain when, tied to the loss of the linguistic absolute, it acknowledges the difference between adequacy and equivalence, equivalence without adequacy. There is its happiness. When the translator acknowledges and assumes the irreducibility of the pair, the peculiar and the foreign, he finds his reward in the recognition of the impassable status of the dialogicality of the act of translating as the reasonable horizon of the desire to translate. In spite of the agonistics that make a drama of the translator's task, he can find his happiness in what I would like to call linguistic hospitality.

Justin Quinn is an Irish poet, scholar, and translator who teaches at Charles University in the Czech Republic. Most recently, his monograph Between Two Fires: Transnationalism and Cold War Poetry came out from Oxford University Press; a new poetry collection, Early House, will be out this spring from Gallery Press. He's also translated the work of contemporary Czech poet Petr Borkovec, whose reception had been primarily confined to European readers.

...(more)

_______________________

Wind comb

2009

Eduardo Chillida

b. January 10, 1924

_______________________

Letter, Including Bears

Justin Quinn

(....)

It’s Beroun. The pub is in a wrecker’s yard

with tanks and armoured cars parked in a line

for kids to clamber on, a rusted rear-guard

the Russians left behind in ’eighty-nine.

Not far away the long E50 sings.

I like to sit here and consider things.

While this inflated bear, the brewery’s logo,

considers me. Irish. Letter writer.

Living in Central Europe (where it’s no-go

for Emperor, Commissar and Gauleiter

these last few decades). Basically, driftwood.

So, Bear, is this OK? Are we all good?

III

The bear declines to say, but has a stein

of frothing beer in his soft plastic paws.

As well as that, he’s tied down with a guy line.

I think I’m good. I’ve given him no cause.

Now, where did we leave off? Russia . . . tanks . . .

(And since you’re here, I’ll have another. Thanks.)

...(more)

Justin Quinn at Poetry International

Justin Quinn at The Gallery Press

Justin Quinn's Articles at Contemporary Poetry Review Interview with Justin Quinn

Front Porch

Justin Quinn Interview

Mistake House

_______________________

Barbara Hepworth

b. January 10, 1903

_______________________

Altermodernity and Modes of Knowledge

Deterritorial Investigations Unit

When we speak of a multi-scaled, meshworked subject such as the Marxist proletariat or the post-Autonomist’s “multitude”, we instantly confront ourselves with a host of problems. The first of these is the distribution of these agents across a global geography: how can we conceive of a way to bind struggles and movements together in some sort of cohesive structure, to relate the actions of one to another, and make the differences between them move in a fluid manner towards what appears to be a common cause? Just as what we call the “working class” is imbedded in globalized flows that replicate patterns of uneven development across the face of the earth, the perception of difference between labor potentially develops into an antagonism that gives rise quite often to the most brutal of racist impulses. Capitalist exploitation, dispersed into global networks, has done more to erect boundaries between revolutionary agents than bring them together.

When confronted with such a scenario, what blossoms is not a revolutionary consciousness, but a parochial consciousness that seeks refuge in the structures of a largely mythical past. The family, the neighborhood association, the church and the club are stripped of any potential revolutionary function and become insular artifacts, things to be defended against the barbarians at the gates. It is a testament to capital’s powers of mystification that the subjugated turn against the subjugated, and not against the system that ensnares them in relations beyond their control. Instead of situating the regional in relationship to the global, wherein the global emerges through the relationships between different regional zones, the regional and the global become antagonists, arranged in a bitter dialectical opposition where the latter performs a corrosive effect on the latter.

...(more)

_______________________

What Next?

Ailbhe Darcy reviews Early House, by Justin Quinn

Dublin Review of Books

Early House is fascinated by the inevitability that rhyme suggests: as one rhyme suggests another rhyme, so we are born, produce other lives, and die. Generation follows generation in a process that has fascinated Quinn since he wrote of the birth of his children in Fuselage:

I love the way our bodies fold around

and into one another, seethe and rend,

then lastly, hurriedly, break out in all joy:

one tiny fleck from off first things, nostalgia

for the love gods have for human form

that generates a further likeness, firm

of limb and mind that wholly takes our love

and lives, before we have to take our leave –

the children echoing down the passages.

It is because rhyme is so absorbed in continuation, in echoing forwards and back, that it offers a fine spot from which to contemplate discontinuity. Early House is powerfully shot through with the anxiety that ordinary continuity is threatened by changes afoot in the wider world, to the global order and to the state of the planet. ...(more)

via the page

_______________________

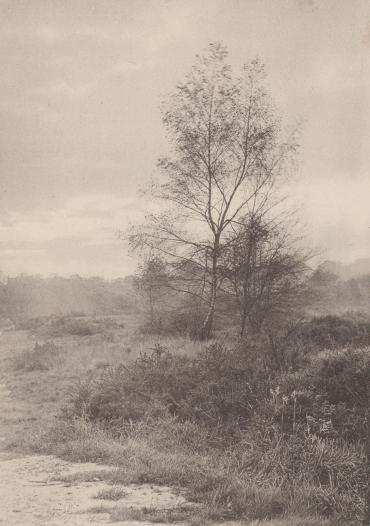

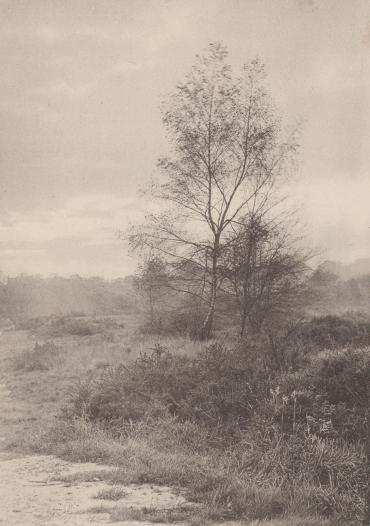

On Hampstead Heath

Karl Greger

1894

_______________________

Small-Time Thief

Petr Borkovec

Translated from Czech by Justin Quinn

body

They’re sawing through the plane trees near Place Sainte-Catherine. 5 a.m., darkness, drizzle and not a soul about (neither on the street nor at windows) – just a three-man team working through the tree-tops. Two surprised blackbirds observe this awful event slantwise from the pavement (they look like drenched sewer rats); a flock of exasperated pigeons jump about on their favourite architrave, and then drift down to the ledge above the laundrette, and from there up again to the roof of Lycée Maria, and round and round; a magpie tenderly peaks into a chimney. Three men in black hoods and orange vests, three weird Franciscans in water-proof overalls, at work (one on an extension ladder, the second on a platform, and the third – who knows how he got up there). The small chainsaws (also orange) melodically bite into the branches, and leave orange and ochre circles in their wake; an orange light rotates crazily on the platform, sweeping the walls and multiplying itself in the windows. The circles and stains on the trunks and the stronger branches mount up. The sawn branches fall down on the paving (one impact frightened off the rat couple), the wet bark peels off and reveals further shades of orange. From the streaked church of Sainte-Catherine can be heard the passionate airs of a bird – probably a thrush – but the darkness and the dim, soft rain doesn’t draw off, and tens of stains, lights and flares, flash off and on, bobbing about in the space of the square. A strange place, cordoned off. No-one’s allowed there in the morning. The thrush has gone silent.

...(more)

_______________________

Esteban Vicente

photo - mw

_______________________

e-flux #69—January 2016

- eight new essays by Reza Negarestani, Irmgard Emmelhainz, Jodi Dean, Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Benjamin H. Bratton, Alan Gilbert, Jonas Staal, and Sven Lütticken.

The Anamorphic Politics of Climate ChangeJodi Dean

The Coming Global Civil War: Is There Any Way Out?

Franco Berardi Bifo

_______________________

Above Dover Beach

Robin Fulton Macpherson

Behind convolvulus and seeding grass

we park.

We see not one scuff or rip on the Strait

to show

two thousand years and more of heavy use.

Southward

across close-to-hand glitter and far-off

mauve haze

the other side if we believe our eyes

is not

there, just as we if we believe our eyes

are here

in a universe with a homely sky

and no

looming non-universes to scare it.

Below,

Waves arrange the shingle, each with a crisp

cadence.

The tide coming in balances the tide

going out.

_______________________

Wall next to Weimar Cemetery

Christian Rohlfs

1892

_______________________

Report from the Gutenberg Galaxy (Blaker), 1-2 (2015) [English/Norwegian]

This Report from the Gutenberg Galaxy is the first in a series of publications to be released in connection with the exhibition project The Gutenberg Galaxy at Blaker (2013–2015). The report is based on the project’s pilot show z(oo)m + – books in motion (Blaker gml. meieri, June 1–16 2013).

The Gutenberg Galaxy at Blaker takes as its point of departure the so-called archive of the artist Guttorm Guttormsgaard, a collection of tens of thousands of objects he has collected with the intention of “documenting necessary impulses to keep one’s spirits up.” The archive is located in a former dairy in Blaker, a village 40 km northeast of Oslo. Coincidentally, Guttorm Guttormsgaard shares initials with the Gutenberg Galaxy, Marshall McLuhan’s designation for the era of print’s hegemony as a medium of storage and transmission. This is a remarkable coincidence because Guttormsgaard has referred to the printed book as a model for his own artistic practice, because he over a period of several decades has excelled as an original maker of books, and because his archive includes a very rich collection of printed matter and printing equipment.

The title The Gutenberg Galaxy at Blaker refers to these riches, while alluding to the fact that new media have displaced the Gutenberg technologies from their previous centrality in our culture (Blaker is a small village at a peripheral location). This development has, however, created new environments where books may function in new ways. Such an insight informs McLuhan’s own books, which he continued to produce despite his proclamation that the Gutenberg era was a closed chapter.

How can we reimagine the book today, its pasts and prospective futures?

_______________________

Digital Revision

Martin Paul Eve

electronic book review

Approaching the work of François Laruelle is a singularly disorientating experience. Billed in marketing blurbs and encyclopedia entries as a “philosopher,” Laruelle is difficult to place. Clearly indebted to the post-structuralist movement, with the verbal tics that run (through) his writing, but likewise also descended from (quasi-Althusserian) Marx, the most common characterization of his work is as “non-philosophy.” While this may summon images of Wittgenstein exhorting his readers to stop doing philosophy, Laruelle is of an entirely different breed, closer to Deleuze and his post-dialectical strain than any school of language philosophy, somehow clustered with Spinoza and the legacy of immanence, on the side of materialism but perhaps radically against empiricism.

(....)

In a new, somewhat sneakily-titled book, Alexander R. Galloway probes Laruelle’s esosteric thought in relation to “the digital.” Or at least, that is the outward proclamation. In reality, Laruelle Against the Digital presents a schematization of Western philosophy and its discontents in order to adequately characterize Laruelle’s thought. At the same time, the “digital” portion of the analysis is intended to critically defamiliarize the way in which we think about digital vs. analog so that a comparison to the history of dialectics can be made in this realm. Galloway’s “digital” is, in fact, only tangentially related to the digital to which we refer in everyday speech and is, rather, here presented as a mode of encoding and thinking predicated upon the breakdown of the singular into differentiated instruction sets. In this world, digitality is more a mindset of deconstruction (although not in its Derridean sense), of division and compartmentalization, than any specific computational phenomenon.

...(more)

_______________________

Song Bird

(Singvogel)

Christian Rohlfs

(c. 1912)

_______________________

Words without Borders - January 2016: Captivity

"As the Northern Hemisphere hunkers down into winter, we’re bunkering in with a variety of captivity narratives. Imprisonment both literal and figurative is in order here, as jailers and captives consider all sorts of confinements. Alain Blottière portrays a season in hell as Rimbaud runs guns and more on the African coast of the Red Sea. Ð? Bích Thúy’s deracinated daughter is drawn back into family bonds. Ivana Rogar’s isolated wife takes no prisoners, and Lina Wolff’s jaded young mistress is roped into revenge. Mohamed Nedali’s young Moroccan couple can’t escape the country’s byzantine corruption. In prison tales, Romania’s Matéi Visniec captures a freed inmate's disorientation, while the Basque writer Ramiro Pinilla voices the multiple ways in which Franco squelched free speech. We trust you’ll find the issue, well, arresting. And five years after the start of the Arab Spring, we feature a selection of writing from the region guest edited by Elisabeth Jaquette." _______________________

Lightning

1935

Christian Rohlfs

d. January 8, 1938 ,

_______________________

Fascism, from Fordism to Trumpism

Angela Mitropoulos

S0metim3s

(....)

Hitler called Henry Ford “My inspiration.” Not surprising, given passages in Mein Kampf were lifted from Ford’s steady stream of texts denouncing the Jewish conspiracy, most of them written before Hitler had become leader of the National Socialist party, many of them circulated in Europe, some of them on the ‘Jewish problem’ in Germany. Like Trump, Ford was a billionaire mogul. Like Trump, Ford had considered running for the US presidency. What there was of polling then put a prospective Ford presidency at around 35%, though no doubt the polling was undertaken as part of an effort to promote a possible run. I am unsure why Ford’s nomination never eventuated, but I leave that to the historians.

What interest me far more is what fascism means or would look like when it is not embedded within the seemingly paradoxical nexus of assembly-line efficiency and nationalist mysticism that shaped the ‘reactionary modernism’ of German National Socialism or Italian Fascism. What would the combination of nationalist myth and the affective labour processes of the entertainment industry mean for the politics and techniques of fascism. Here too I am unsure I have a ready answer, though I think we can begin to discern the shape of it.

Perhaps Trump’s fascist appeal is that he promises to make racist violence enjoyable and entertaining again. Perhaps this is where the shift between the assembly-line and the entertainment-hotel industry can be registered. I do not mean to diminish the importance of this point. The step between the labour camp and death camp was written in the language of an assembly-line efficiency ‘solution’ to a problem conjured up by productivist fantasies. I do mean to underline the importance of understanding the character and shape of fascist violence, including how it might change.

So rather than engage in protracted, faux-scholarly disputes over whether Trump is a fascist because fascism presumably (and ironically) has an unchanging essence (see note 5 below), this seems to me the more important question. And by ‘seemingly paradoxical’ I mean that the apparent contradictions between adherence to the foundational mysticism of a national essence (reproducible through sexuality and racialised properties) and the tenets of calculating reason are not a contradiction when understood as a dynamic of oikopolitics.

...(more)

wild turkeys

marching into the new year

photo - mw

_______________________

Lessons in Darkness

Peter Gizzi

(....)

There, the notes, the song,

the besidedness to live

on Saturday, to walk out,

wanted to, right out the frame.

The sadness, gas pumps,

sunshine on oil,

that crow overhead

destroys the picture.

Everything faking it so badly.

What's so wrong about the real,

so off with clarity,

dumbfuck, shirttail-hanging

scatter-brained word.

Shattered-pane world?

The whir of the camera inside pictures

but we want the voice to lift,

don't we, across the mini-plaza

to where? How about

pulling taffy for a living

or a rabbit from one ideal-ology

to another. That's the trick

isn't it, parallel lives?

...(more)

from In Defense of Nothing: Selected Poems, 1987-2011

Getting to know nothing

A review of Peter Gizzi's In Defense of Nothing: Selected Poems, 1987–2011

Chris Hosea jacket2

(....)

Here is a poetic that begins with a radical rebuilding of the modernist lyric and never loses its obsession with this undead tradition. Nevertheless, Gizzi’s work has moved toward a recuperation of the Romantic project, proffering a speaker as straw man and stylized avatar. This poet begins with formulae and witty critique, and develops into a master of powerful argument who makes music through play upon resonantly traditional themes. One’s sense of speaker and reader is never stable in these poems. Indeed, the poet’s troubling of these categories refreshes them in his recent poetry. If Gizzi would purport to defend “nothing,” as the title of this Selected suggests, it is perhaps the “nothing” that, in Auden’s formula, poetry makes happen.

Perhaps even more, this Selected is testament to an engagement with the “nothing” Socrates had in mind when he declared, “All I know is that I know nothing.” For Gizzi, a willingness to edge close to nothingness, nonsense, and awkwardness pays rich dividends in poems that resonate well beyond paraphrase. The product of immersion in arcane traditions of poetic making, this book contains beautifully pieced-together lyrics that are, at their best, endlessly beguiling. This well-edited Selected should give new readers an excellent chance to tune in.

...(more)

Peter Gizzi at the Poetry Foundation and PennSound

_______________________

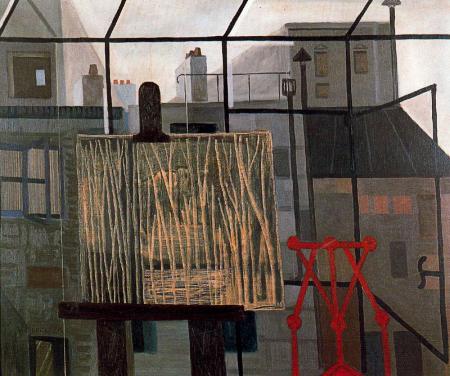

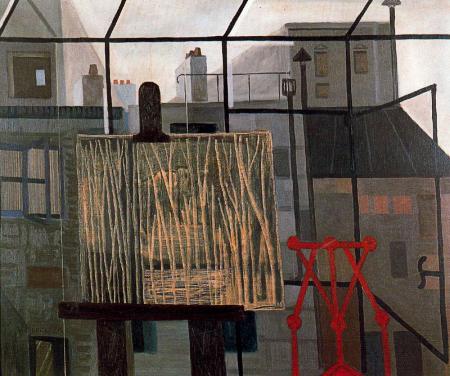

studio

Óscar Domínguez

b. Jan 7, 1906

_______________________

The Geography of the Imagination: Forty Essays

Guy Davenport

d. January 4, 2005

google books

Reflections on Guy Davenport’s Poetics

Marjorie Perloff

(....)

What does it mean to say “the century was over in its sixteenth year,” that after 1915, there was no more significant artistic innovation? True, Davenport clarifies things for us somewhat in the lead essay of The Georgraphy of the Imagination, “The Symbol of the Archaic,” which declares that the “renaissance of 1910” was “a renaissance of the archaic,”. Here and elsewhere, Davenport writes trenchantly of the discovery of the Lascaux and Dordogne caves, of the turn to Heracleitus and Sappho, both of whom he had translated, and of the red-stone Kouros that became Picasso’s touchstone even as the Hellenistic Laocoon had, in an earlier Renaissance, been Michelangelo’s. “What is most modern in our time,” writes Davenport, “frequently turns out to be the most archaic. The sculpture of Brancusi belongs to the art of the Cyclades in the ninth century B.C.,” and “there is nothing quite so modern as a page of any of the pre-Socratic physicists, where science and poetry are still the same thing and where the modern mind feels a kinship it no longer has with Aquinas or even Newton”. “The heart of the modern taste for the archaic,” Davenport quips, “is precisely the opposite of the Romantic feeling for ruins”. For whereas the Romantics longed for the survival of a still visible past, the Modernists were stimulated by a past that no one hitherto had known existed—like the cave drawings at Lascaux and Altamira—and that might thenceforth inhabit the same plane as Picasso’s cubist forms. As for poets, the great inventor of the archaic was, in Davenport’s view, Ezra Pound, whose “daedalian art” produces a “golden honeycomb,” in which the Homeric gods, the Eleusian mysteries, the earliest Chinese sages and poets, and Pound’s own friends and enemies inhabit one and the same cosmos.

But even when we have read Davenport’s fascinating discussion of the invention of the archaic as the central ethos of Modernism, it may not be quite clear to readers how the Great War destroyed that invention in one fell swoop. Here we must, I think, look to the Russian avant-garde, which Davenport was one of the first Anglo-American critics to recognize and understand. His remarkable recreation in one of his first stories, “Tatlin!” of the life of the brllliant sculptor, along with his fellow artists like Larionov, against the backdrop of the Russian revolution, sets the stage for Davenport’s understanding of this avant-garde ......(more)

_______________________

Red Earth

Joaquim Mir

b. January 6, 1873

_______________________

Reclaim Modernity: Beyond Markets Beyond Machines [pdf]

Mark Fisher and Jeremy Gilbert

Compass

"This new Compass publication, Reclaim Modernity, ignites a towering inferno of hope. It does so by calmly and clearly explaining that we are in a unique moment of history. The way the world is developing can be in tune with our values. We don’t have to fear modernity, or capitulate to it. It doesn’t have to be the acceleration of everything that’s bad about the present. It could actually be better. Reclaim Modernity helps us understand why the bureaucratic state always had it limits and the free market was never going to be the antidote.”

Compass books

via Deterritorial Investigations Unit

_______________________

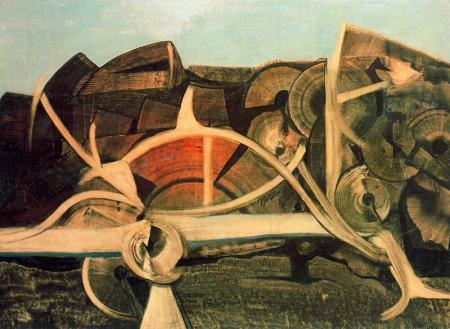

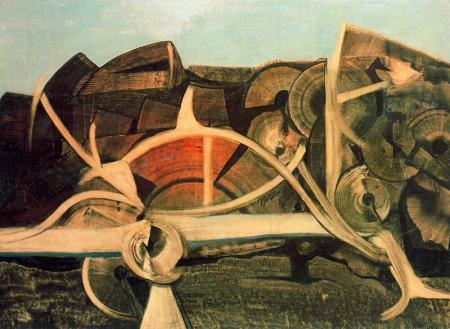

Óscar Domínguez

_______________________

A Translation of "Goethe schtirbt" by Thomas Bernhard

Douglas Robertson

On the morning of the twenty-second Riemer urged me to speak during my one thirty-scheduled visit to Goethe on the one hand softly, on the other hand not so softly to the man of whom it was only now being said that he was the greatest luminary of the nation and at the same time the very greatest of all Germans who had yet lived, for he now heard on the one hand at one moment with downright appalling clarity, at another almost no longer at all, and one did not know what he heard and what he did not hear and although it was the most difficult thing while interviewing the genius, who was lying there more or less motionless the whole time, on his deathbed, which faced the window, to arrive at a suitable volume in one’s own utterance, it was nonetheless possible, especially by way of a supreme sensory attentiveness, to discover in the course of this now merely melancholy-inducing interview precisely that middle way that accorded with his now universally evidently terminal mind. ...(more)

Landscape

1952

Nicholas de Stael

b. January 5, 1914

_______________________

Marianne Fritz & Ingeborg Bachmann

An introductory comparison of the intentions of Marianne Fritz and Ingeborg Bachmann

flowerville

Introduction

Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973) and Marianne Fritz (1948-2007) invite comparison, because they are both Austrian writers, both worked on novels with overarching themes (Bachmann: Todesartenprojekt; Fritz: Festungsprojekt) and both share similar concerns, such as the investigation of hidden crimes. While it is problematic to assume the intentions of any author in the case of Fritz and Bachmann, they actually wrote their intentions down. In Fritz’s case this involves her book Was soll man da machen, sometimes extensive glossaries to her books and, in Bachmann’s case, in letters to the publisher. Both documents exhibit similarities in that both writers decide to move away from writing official history and, in contrast, to turn inwards, which has consequences for their views on language. This notion of inwardness will be discussed with the help of Wendy Brown’s essay on silence 'In the ‘folds of our own discourse’: The Pleasures and Freedoms of Silence'. It will be concluded that, in order to do justice to those marginalised by history and language, one needs to avoid the equation of freedom and political/social power with voice and visibility and, instead, requires an understanding of the complex functions of silence for those without words. This means also to understand silence not just as a sociologial or political category but an inherent element in language. One needs to stop seeing speech and silence as oppositions but try to understand the various ways in which people use silence and speech in order to preserve their individuality and notions of potential happiness in the face of adversity.

...(more)

_______________________

The Furniture of Time

1939

Yves Tanguy

b. January 5, 1900

_______________________

Three Poems from “The Disasters of War” after Goya

Jerome Rothenberg

Sad presentiments

of what must come

to pass

a rage

of shredded clothes

the darkness

through which images

rain down

a ruined world

of bricks & walls

erased

or crumbled

shattered*

* splattered

on the broken ground

made present

by an unseen hand

like mine

the lines concealing

men & women

children

trees & gardens

grass gates gravestones

shrines & temples

class rooms

radios & books

old dresses

fifes & fiddles

heirlooms

bicycles

eyeglasses

sidewalks

monuments

engagements

marriages

employees

clocks & watches

street signs

works of art

...(more)

_______________________

Extinction of Useless Lights

Yves Tanguy

1927

_______________________

The Fibreculture Journal

issue 25 2015: apps and affect

(....)

Isn’t it paradoxical, we asked, that instead of becoming ‘transparent’ and ‘invisible’ – as envisioned by the thinkers of ubiquitous computing decades ago – the app-ecosystem manifests itself as permanent excess: excessive downloads, excessive connections, excessive proximity, excessive ‘friends’-qua-‘contacts’, excessive speeds and excessive amounts of information? How does the app as ‘technique’ (Tenner), indeed as ‘cultural technique’ (Siegert) and as ‘technics’ (Stiegler), channel our ways of maintaining relations with/in the media environment? Do the specific and circumscribed operations of individual applications foster or foreclose what media theorists call the transformative and transductive potential of collective technological individuation (Simondon)? How might we think about the social, political and technical implications of this movement away from open-ended networks like the internet towards specific, focused, and individualised modes of computing? Do apps represent ‘a new reticular condition of trans-individuation grammatising new forms of social relations’ (Stiegler) or do they signal instead the triumph of ‘regulatory’ networks over ‘generative’ ones (Zittrain)? If apps are micro-programs residing by the hundreds and thousands on cell-phones, mobile-devices and tablets, and affects are corporeal excitements (and depressions) running beneath and beyond cognition, what is the relation of apps to affects?

...(more)

via Synthetic_zero

_______________________

Gentilly

Nicholas de Stael

1952

_______________________

The Tyranny of Imagery

Anonymous

The present is bleak. We are frozen in static images of ourselves. Our ubiquitous digital presence hides a very real absence from our own lives, from relationships of intensity, from motion. The function of producing identities and categories is becoming more diffuse. We are hemmed in on all sides: by the categories of states and police, by the social networks that identify us, by our creation of identity in our profiles, by those activists who consolidate identity in order to seek recognition and power.

no new ideas press

_______________________

Two Poems by Kim Seung-Hee

translations by Brother Anthony of Taizé and Kim Seung-Hee

aymptoteAvantgardists

Usually avantgardists are shot and killed first,

probably because they have thousands of butterflies flying about inside them.

There are times when saying I’m alive feels obsequious.

It’s when a problem arises about eating and living.

Would it not be all right to live without eating?

Just as Kim Su-Young, having done some translations to earn pocket money,

went and sat down in a magazine publisher’s office,

where he was told by the editors, “We feel afraid when we see you working,”

and heard that kind of insult, ridicule, painful words,

so if avantgardists are shot and killed, that’s cool,

but if they live like actors changing lamps, that’s servile.

An actor can change lamps forwards and backwards.

Avantgardists have to be butterflies with their bodies, their whole bodies.

They have to be soapbubbles.

...(more)

_______________________

Storm

Nicholas de Stael

photo - mw

_______________________

There Is Ignorant Silence in the Center of Things

William Bronk

What am I saying? What have I got to say?

As though I knew. But I don’t. I look around

almost in a sort of despair for anything

I know. For anything. Some mislaid bit.

I must have had it somewhere, somewhere here.

Nothing. There is silence here. Were there people, once?

They must have all gone off. No, there are still

people, still a few. But the sound is off.

If we could talk, could hear each other speak

could we piece something, could we learn and teach,

could we know?

Hopeless. Off in the distance, busyness.

Something building or coming down. Cries.

Clamor. Fuss at the edges. What? Here,

at the center — it is the center? — only the sound

of silence, that mocking sound. Awful. Once,

before this, I stood in an actual ruin, a street

no longer a street, in a town no longer a town,

and felt the central, strong suck of it, not

understanding what I felt: the heart of things.

This nothing. This full silence. To not know.

_______________________

André Masson

B. Jan 4, 1896

_______________________

Isabelle Stengers: In Catastrophic Times

S.C. Hickman

(....)

As I began reading Stengers latest work tonight it reminded me of so many works of late that are almost prophetic in tone, bewailing the fate of ourselves, the earth, the zone of habitable life which so precariously seems drifting toward utter collapse and extinction. And we worry over the basics of day to day living, survival, terror, political corruption, austerity, sex slavery, racism, etc. etc. …. as if splitting all our problems off into various sinkholes of activism will keep the truth at bay. Even the sciences themselves have become so politicized that the Left and Right, Progressive and Reactionary, etc. all line up their various experts defending or castigating the models that speak of global warming and the Sixth Extinction. The World of data is seems bound to mathematical ontologies that our common sense folk psychologies can neither apprehend nor share in. The algorithms that chart in minute detail the various aspects of the climatological picture along with the extreme data of our ongoing Sixth Extinction seem like narratives out of some Sci-Fi novel. We are so busy just surviving the plight of our economic lives we want to put such Sci-Fi narratives on the backburner as if it were just another fictional piece of data for the analysts, the government, the scientists to worry over. As we say here in the USA – “It’s not my job to think!” So we turn the mind off, go home to our children, wives, husbands, girlfriends, etc. and forget the truth might be just over the horizon coming at us faster than we might ever believe.

(....)

The real barbarians are not the refugees in our midst, rather they are the men and women wandering Fifth Avenue, Wall Street, the grand and illusionary global cities of pleasure, fun and profit. The barbarians at the gate are those oligarchs and their sycophantic minions in government and business, traveling the world’s fast lanes, the archons of capital and finance, oil and diamonds, corporate and private Moghuls who squander the true human capital of our world without a thought about what debt must be paid for such excess. And it will be paid, one way or the other. Yet, most of all the real barbarian is us: we who look on complaining, but doing nothing to change things. We who get up everyday in the same cess-pool and convince ourselves this is life, that it will be alright; we have to think about our families, our children, they come first… etc. All lies, sweet lies to convince ourselves that the night of nights come at us out of the future is just another Sci-Fi horror film.

...(more)

dark ecologies — the literate edge of desire

_______________________

Colored composition

(Hommage to Johann Sebastian Bach)

1912

August Macke

b. January 3, 1887

_______________________

Special Issue on Walter Benjamin

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature, Vol. 11, Iss. 1 (1986)

Proust and Benjamin: the Invisible Image

Beryl Schlossman

Abstract

Benjamin's essay "Zum Bilde Prousts" questions the status of the image even as it leafs through the possibilities and variations that form it—as photograph, figure, representation, disappearing trace or promise of creation. As the image of Proust's novel, Benjamin's text takes up the elements of A la Recherche du temps perdu (poetic language, autobiography, critical commentary) in the terms of Benjamin's theory of allegory reflected through the Proustian strategy of reading and writing. "Zum Bilde Prousts" examines the traditional markers of "art" and "life," locating Proustian recherche—and Benjamin's image—in the deep waters beyond them. Through an interpretation of Benjamin's image of Proustian ecstasy (the descent of the mystic) and the images unfolded "Au Temps Perdu" (Benjamin's mystical station of nineteenth-century allegory), Benjamin's essay sollicits a new reading of time and eternity, memory and ecstasy. The final illumination of Proust's artful night indicates the decisive turn toward writing at the spot where "Niles of language" come together—the point of convergence of the image and its invisibility.

Aux veux du souvenir

At the conclusion of the Proustian itinerary, the closing sentence of A la Recherche du temps perdu, the reader circles back to the "petite phrase" at the beginning: "Longtemps je me suis couche de bonne heure." Although it has become a critical commonplace to link the narrator's conclusive vocation with the writing of Proust's novel, the gesture of circularity is encoded within Proust's fiction: it is an effect. Unlike the narrator, Proust himself is the author of the Recherche. At the very moment of circling back, the reader is confronted by the impossibility of his own gesture and the incommensurable gap separating the announcement of the narrator's scriptural vocation from the first sentence and its nightfall. Just as the arc cannot be closed and made into a circle, it is impossible to collapse narrator and author into a single identity. In this sense, the effect of the Proustian voyage toward the narrator's vocation is the revelation of vocation as mystery-as a mystical event. The "end" of Proust's novel opens the question of vocation rather than closing it. Beyond rational experience, the ecstasy that takes the narrator as its field reveals truth to him in the form of an inner book awaiting creation.

It is not by chance that at the end of Walter Benjamin's essay, "Zum Bilde Prousts" ("Toward the Image of Proust "),' the reader turns back to its first paragraph in search of a beginning-something that might have led to the final Proustian image of Proust himself. creating the Creation, suspended on a scaffold like Michelangelo. But Proust's scaffold is the sickbed, and death. In Benjamin's text as in Proust's final scene of the matinee chez la princesse de Guermantes, the image of creation is predicated on one of disappearance. The central Bild-figure, representation, photograph, and so on-is as much an open question, in Benjamin's interpretation, as the "ungezahlten Blatter- of the Proustian creation.

...(more)

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature

_______________________

Dear Blank Space: A Literacy Narrative

Jennifer S. Cheng

(....)

Dear Rest Note

By which I mean, if it is not yet clear, form as language. I mean: The shadowy white of the page. Measures of emptiness, an absence of sounds, as part of the vocabulary. Writers say form and language, as if they are distinct elements of consideration, but I am interested in tensions of space, pockets of text amidst silent tracts, as a kind of language in itself. It is true that we speak different languages, we learn different native tongues, and sometimes, in an unexpected arrangement of stars and space, we find a discourse for what we could never before say.

(....)

Dear Anechoic Chamber

Inside the silence: Your heartbeat. Your blood making its way through the body. A ghost is a ghost whether or not you have been waiting to hold its hand. When John Cage wrote 4’33’’ he knew that inside the vacuous interval would materialize all our transient noises, unnamed sounds. Silence moors us to the waves inside us and to the air surrounding our bodies. Stitches us into their texture. On the coastal forest where we make a tent in which to sleep ourselves, the night hours grow until they cocoon us. How once your eyes adjust, shapes can be made out swimming in the inky darkness: mountains, trees, seas. How you can detect unevenness in the sky, shadows of varying opacity, movements from darkness to lighter darkness.

*

Dear Mother Tongue

This, too: Children of immigrants, like poets, know that language is sometimes a textural thing instead of something linguistic. Lilt of a tone as something woven, like a nest or blanket or boat. They know that language is wind-blown terrain, an entanglement to make one’s way through, a process of raveling and unraveling and in that, love. A child in her house moves daily through myriad opacities: intimacies untold, histories unsaid, her loved ones at turns impenetrable, kaleidoscopic, porous. She learns to navigate by way of water mixing into water, a small sound that touches the earth that hinges the sky. Her language of intimacy even in adulthood: Child sounds. Warped and full of holes. So I have something invested in silences. In the roundness held there.

*

...(more)

Entropy

Jennifer S. Cheng

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Umbrella Poetics

Jennifer S. Cheng

drunken boat

(....)

4/

For many immigrants and children of immigrants in America, our belonging is a kind of longing. It is not as simple as saying that we belong nowhere or we belong everywhere but only that it is somehow precarious, that there is a quiet yearning for, an understanding of, some undefined space ever in the periphery of one’s eye. When I began travelling back to Hong Kong as an adult, I found I could still only know it as it belonged in my heart: deep green hills that cradled my body, moistened tile platforms and pedestrian walkways that rose and twined and ended at the ocean, passageways and alleys I could know and not know, bus rides up and down unkempt mountains, toward and away from the sea. What I mean is: I have never been able to know what Hong Kong means to other people, whether they are outsiders or my own father, and when I think of the city, I think of it as an aberration, a tiny crescent yearning in the midst of a large starry sky.

What I mean is: As much as home is an anchor in the body, a protected space no on else can ever know, we have always known how identity is yet also fluid, murky: how we have had to construct it and claim it with twigs we collected and terrains we named, here and there: how its boundaries shifted and burned with memories uncovered, histories relearned, linguistics transformed, distances and shadows narrowing and growing and looming.

...(more)

|