|

photo - mw

_______________________

Richard Dauenhauer: 22 Koyukon riddle-poems

Translated & arranged by Richard Dauenhauer after Father Julius Jetté, S.J.

presented byJerome Rothenberg

Like a spruce tree

lying on the ground:

the back-hand

of the bear.

.

I drag my shovel

on the trail:

a beaver.

.

Water dripping

from an ice-spear tip:

water dripping

from the beaver's nose.

.

Like bones

piled up in the stream bed:

sticks

the beaver gnaws.

...(more)

_______________________

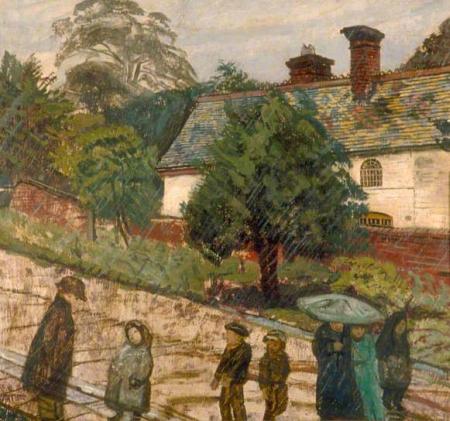

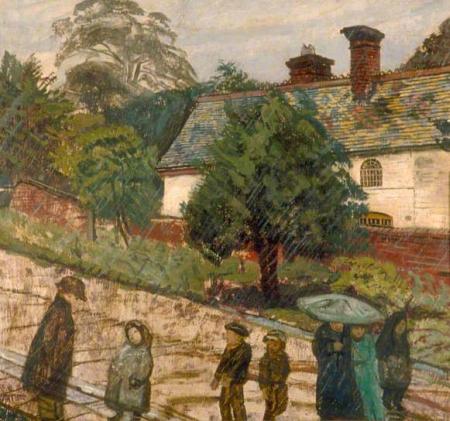

photo - mw

_______________________

Tumbling After

Craig Eklund

conjunctions

He said, “They say the truth always comes out in the end.”

She said, “But it was spelled out right from the start in big red letters posted square on the door: Inveterate Liars Anonymous. Anonymous? I mean, does a congregation of hardened incorrigible compulsive dissemblers need an invitation to not own up to who they are? Get past that tautology and you’ve still got to consider the paradox of the Inveterate Liar calling herself an Inveterate Liar and that will take you all the way back to the ancient Greek philosopher Epimenides, who said, Anyone who believes me when I tell them they’re not a cretin is a cretin. True story.”

“What they don’t say is that the end comes out of the truth. Here it is. In black and white. Written in your own hand. Don’t try to deny it. And don’t go and get indignant on me either. I wasn’t spying or snooping or whatever weasely little verb you’re going to try to turn against me. Meddling or prying or ferreting. Nothing of the sort. I dropped a grape, that’s all. I was home from work. I was slipping off my tie, on my way to the bedroom, munching on a handful of grapes. Red grapes. And just as I was walking past your studio, I dropped one. It fell and rebounded off my left knee at a horizontal and then ricocheted off the side of the end table at a forty-five degree angle. It slipped into the joint between the tiles and rolled over the grout until it disappeared behind the prints you have leaned up against the wall. I wasn’t poking about, wasn’t nosing around. I dropped a grape. So I tilted the prints aside and lo and behold what did I find lying there beside my dropped red grape? Your diary. The truth. The end. Are you even listening?”

...(more)

_______________________

A Challenge to Galen Strawson’s “I am Not a Story”

J. Edward Hackett

Philosophical Percolations

(....)

... keep in mind that thinkers like Gilbert Harman have also invoked psychology to argue that there are no such things as dispositions. While I am not claiming that there are no such things as dispositions for virtue theory is the same as saying there are dispositions for self-authoring, we can anticipate some lengthy discussion about how best to understand psychology’s relevance for theorizing about self, agency, responsibility, and intrapersonal relationships. Another point can be raised just as much if not more than the tensions about appeals to psychology.

The Analytic and the Continental traditions do not entertain questions of philosophical anthropology as much as they should. Important to our discussions here are claims about the structure of life and human beings, and how these structures are left open to possibility as much as sedimented possibilities by real and ideal factors in culture (Ideal and real factors are terms from Scheler’s sociology of knowledge and philosophy of culture, which I take to be implicit in this response, but wanted to make known explicitly).

Next, the appeal to literary cases of fragmented self is a cherry-picked example of the type of phenomenology he wants for the claims he is making about that dearth unity of self. This is really the type of problem that the application of phenomenological method could solve, and here’s where I want to return to two thoughts opened up by Strawson’s essays.

...(more)

Galen Strawson’s “I am Not a Story”_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

The Privatisation Of Stress

The numerous pathologies generated by neoliberalism can only be cured within a revivified public sphere.

Mark Fisher

(....)

... Jodi Dean has convincingly argued that digital communicative compulsion constitutes a capturing by (Freudian/Lacanian) drive: individuals are locked into repeating loops, aware that their activity is pointless, but nevertheless unable to desist. The ceaseless circulation of digital communication lies beyond the pleasure principle: the insatiable urge to check messages, email or Facebook is a compulsion, akin to scratching an itch which gets worse the more one scratches. Like all compulsions, this behaviour feeds on dissatisfaction. If there are no messages, you feel disappointed and check again very quickly. But if there are messages you also feel disappointed: no amount of messages is ever enough. Sherry Turkle has talked to people who are unable to resist the urge to send and receive texts on their mobile telephone, even when they are driving a car. At the risk of a laboured pun, this is a perfect example of death drive, which is defined not by the desire to die, but by being in the grip of a compulsion so powerful that it makes one indifferent to death. What’s remarkable here is the banal content of the drive. This isn’t the tragedy of something like The Red Shoes, in which the ballerina is killed by the sublime rapture of dance: these are people who are prepared to risk death so that they can open a 140 character message which they know perfectly well is likely to be inane.

The privatisation of stress is a perfect capture system, elegant in its brutal efficiency. Capital makes the worker ill, and then multinational pharmaceutical companies sell them drugs to make them better. The social and political causation of distress is neatly sidestepped at the same time as discontent is individualised and interiorised. Dan Hind has argued that the focus on serotonin deficiency as a supposed `cause’ of depression obfuscates some of the social roots of unhappiness, such as competitive individualism and income inequality. Though there is a large body of work that shows the links between individual happiness and political participation and extensive social ties (as well as broadly equal incomes), a public response to private distress is rarely considered as a first option. It is clearly easier to prescribe a drug than a wholesale change in the way society is organised. Meanwhile, as Hind argues, `there is a multitude of entrepreneurs offering happiness now, in just a few simple steps’. These are marketed by people `who are comfortable operating within the culture’s account of what it is to be happy and fulfilled’, and who both corroborate and are corroborated by `the vast ingenuity of commercial persuasion’.

Psychiatry’s pharmacological regime has been central to the privatisation of stress, but it is important that we don’t overlook the perhaps even more insidious role that the ostensibly more holistic practices of psychotherapy have also played in depoliticising distress. ...(more)

The Day Comes to an End

Fernand Khnopff

1858 - 1921

_______________________

13 poems

John Perreault

1937 - 2015

A Crazed Girl

In a world without brief music

there would be only shore

and not the crashing ocean itself,

and only tide wrack where

the festival steamship

has run aground. I thus declare

without a word there is no thing

but only shadow can be found.

If in the future this has occurred,

where we can smell the wound

our present triumph

will have stuck where it lay

and now would not be the sound

of the uprising at last of the sea. ...(more)

_______________________

parsing the master’s design: a close reading of theory-praxis polarity

Frank Smecker

3am

(....)

Is this not how things always begin?—first in a harrying mess before something unexpectedly intervenes, something which, in the end, manages to shore everything up into a neat and tidy consolidation. Let me simply say that this amounts to something comparable to what is elsewhere called history, or, to speak in the jargony parlance of theory, the reification of radical contingency… if I may put it like that.

A true atheist will understand what I am getting at here, namely that this intrusion-of-something exemplifies perfectly well what we ought to make of God and His story, this propping up of the world. Rather than calling Him into question, one could learn a great deal by recognizing in God the profound mark of a true and blue Master Signifier, the nascent form of which is the primordial empty signifier, which simply represents signifierness as such. Which not only intervenes in the form of the Word, inaugurating the contingent beginning of an errant life always-already in need of governance by God’s Holy Law or what have you, but that, moreover, like everything else touched by thought, this pure signifier, and each one similar to it, eventually gets everything around it neatly consolidated, condensed into something without which everything would consequently fall apart and be a mess again.

(....)

... We can, I believe, catch a glimmer of the real in this wide net of signification once we recognize that the authority of reference—the proverbial master whom, despite emerging in an unconscious and contingent manner, keeps our knot tightly, compactly, jointly together—effectively obfuscates the underlying dimensions of language that prop up this entire charade in all its divine glory, namely: the underlying matrices of signification which, as Paul de Man once astutely observed, consist in “a vast thematic and semiotic network” that structures our narratives and produces our subjectivities.

Now, if there is a definitive statement that can be made about the general situation we are in, at the broad level today, it is that things are awfully close to becoming such a wholesale mess. So close, in fact, that there are many who show not the slightest reluctance in claiming this mess to have already been made, and that the salient characteristic of contemporary life is thus the detritus of the past and present ages—their flotsam, their debris. The modern world, Le Corbusier once wrote, is “like a charnel house,” which “lies strewn with the detritus of dead epochs.” But this might not be such a terrible thing. Suffice it to recall what Lacan had told his audience during his tenth seminar: “What culture transports to us in the guise of the world is a stack, a shop crammed full of the flotsam and jetsam of worlds that have followed one after the other.” What we have before us, then, this debris, is none other than a manifold of sorts, which amounts to a combinatory that, in Lacan’s words, will eventually “join up with the structure of the brain,” a structure the shape of which is nonetheless yet to be determined. That is what is being put under consideration in this essay.

...(more)

_______________________

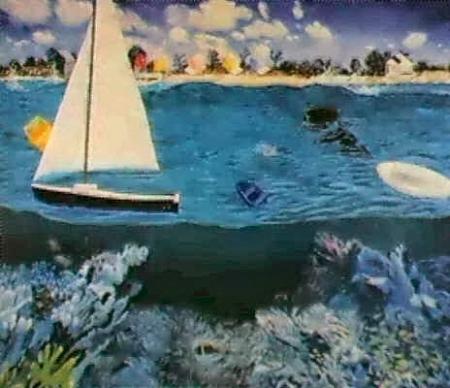

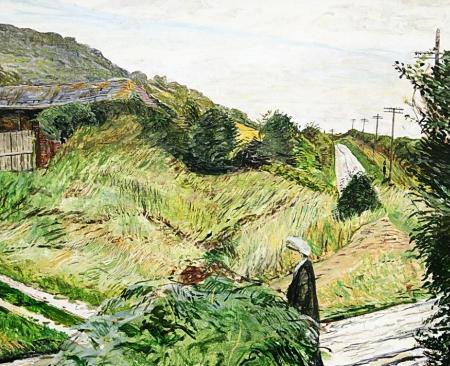

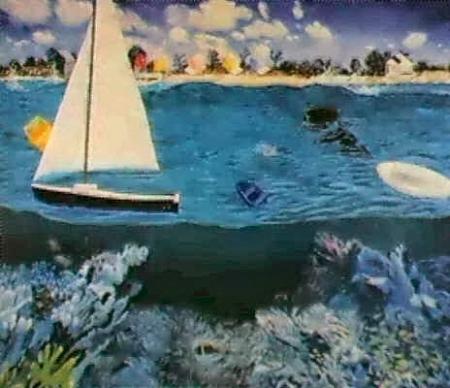

Frederick Judd Waugh

_______________________

Poetry and the fearful symmetry.

Daniel Bosch

fortnightly review

THE SETTING OF the sun has always been legible as a threshold to terror. The world we command in daylight we cede, at night, to danger, to death, and to the spirits of the departed. The sun also rises, yes, but at each day’s anticlimax we know darkness must prevail—for a time—and that we can do but little in the interval. For millennia, at nightfall, we have gathered around what little light we’ve had, while some few of us kept watch, however distractedly. These facts frame all our extended fictions.

The optical is the existential. The instant night falls, we see less well, and conversely—perversely—we “hear things.” Night estranges. The certainties of day-lit labor yield to doubt: What was that? At night our imaginations, less-constrained by the sharp edges of the visible, and, as in childhood, less-convinced by rationalization and counter-evidence, confirm and reconfirm: We are not safe in night. We do not belong to it. By ancient cookfires and hearths—the first footlights—we won dim globes from darkness in which learned to what we do belong. Closest to the firelight, lungs and lips wove sounds into patterns that would form the bases of all art. Auditors exhausted by the day’s labors ate, drank, listened, absorbed, objected, were indoctrinated, dozed, made more humans—became more human. At the barely-lit perimeter, from which the singer’s tales and the shaman’s spells and the songs and the laughter and the cries of parents and siblings and cousins were barely audible, expression took simpler but even more urgent form: “Who goes there?” Only rarely did the question receive a human reply.

“Men shut their doors against a setting sun,” as Shakespeare put it, but this is precisely why no one is more important to our songs and narratives than the one who has ventured into the proscribed darkness and returned to tell his tale of the night. In every known literary period and tradition speakers of such poems have staked their claims to our attention upon their authority as ambassadors from a darkness their audiences presumably know less-well. We clamor for their darkly articulate accounts of the liminal spaces they claim to have traversed. From relative safety, we listen to their soliloquies and we relish their trepidations, their extravagant beautifications and other idealizing tropes, even the ways they instrumentalize night. (Exceedingly rare is any vision of the heart of darkness). Narrative or lyric or dramatic, primeval, mediaeval, Romantic, modern, futuristic, or post-modern, night visions give character and form to rhythms of human experience which are ancient, epic, and—on this planet, at least—permanent.

...(more)

via The Page

_______________________

Shoe

John Perreault

A road can't be as sad as a shoe is sad

when a shoe can't read.

I can't read either.

And I have given away all my clothes

and gone away so far

that no one will even remember that I've gone

nor how far I went when I was here.

For a road can't be as crazy as a ranch is mad

when a ranch can't sing.

I cough. I spit. I jump up and down

and I run around like a headless rooster.

Me too. I am not lonesome. I am gregarious.

I make friends with the curbstone even.

But a shoe can't be as pretty as a wheel when it's turning

or a tunnel uncovered by chance.

And a shoe can't be a lobster.

I am as free as a belt or a bell or

a dog on a leash

gone crazy with the aroma of flagpoles.

_______________________

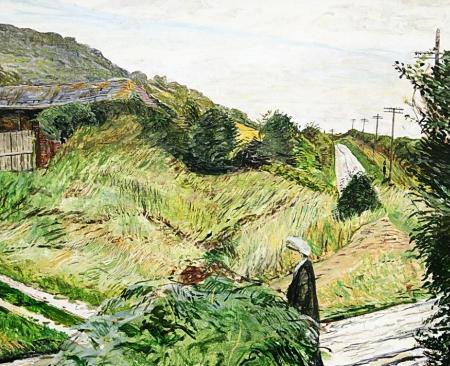

moonlit meadow

Frederick Judd Waugh

b. September 13, 1861

photo - mw

_______________________

Human and Non-human Agencies in the Anthropocene

Gabriele Dürbeck, Caroline Schaumann and Heather Sullivan

Abstract

The era of human impact throughout the Earth’s biosphere since the Industrial Revolution that

has recently been named the Anthropocene poses many challenges to the humanities, particularly in terms of human and non-human agency. Using diverse examples from literature, travel reflections, and science that document a wide range of agencies beyond the human including landscape, ice, weather, volcanic energy or gastropods, and insects, this essay seeks to formulate a broader sense of agency. All of our examples probe new kinds of relationships between humans and nature. By configuring a close interconnection and interdependence between these entities, the Anthropocene discourse defines such relationships anew. On the one hand, our examples highlight the negative effects of anthropocentric control and supremacy over nature, but on the other, they depict ambivalent positions ranging from surrender and ecstasy to menace and demise that go hand in hand with the acknowledgment of non-human agencies.

_______________________

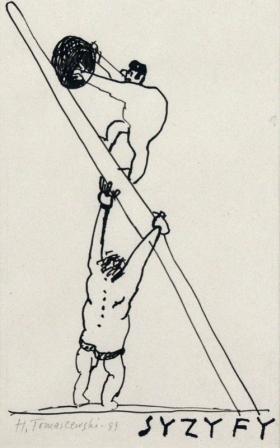

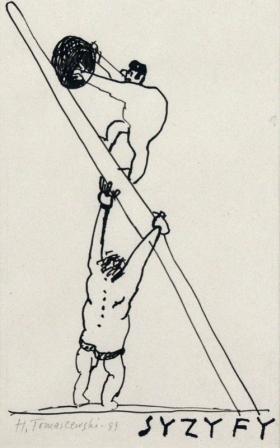

Sisyphus

1983

Henryk Tomaszewski

d. September 11, 2005

_______________________

Because We Love Bare Hills and Stunted Trees

Margaret Atwood

(....)

Everything once had a soul,

even this clam, this pebble.

Each had a secret name.

Everything listened.

Everything was real,

but didn’t always love you.

You needed to take care.

We long to go back there,

or so we like to feel

when it’s not too cold.

We long to pay that much attention.

But we’ve lost the knack;

also there’s other music.

All we hear in the wind’s plainsong

is the wind.

...(more)

via The Page

_______________________

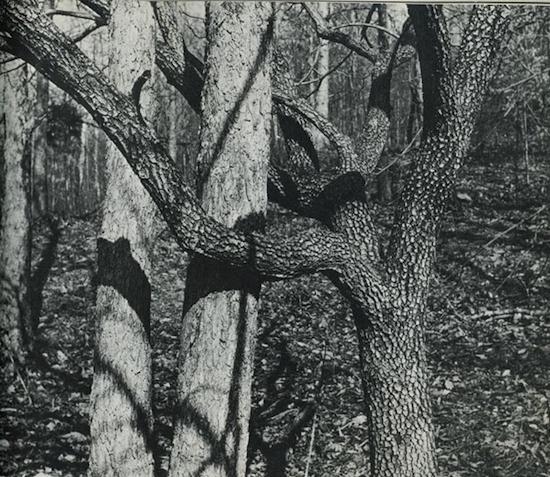

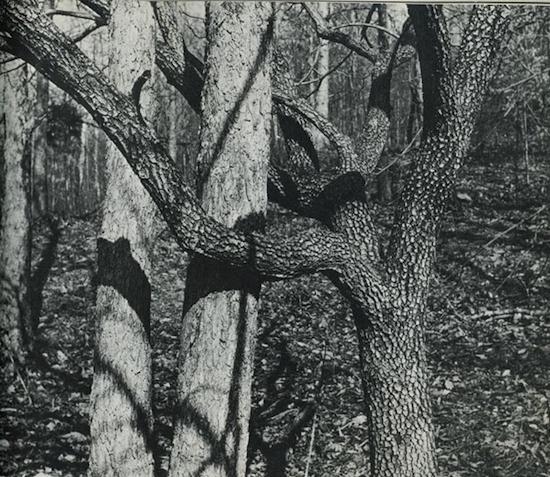

The Zen Photography of Thomas Merton

_______________________

COTA Revisited – From the Invisibility of Industry to the Industries of Invisibility (PART I)

Cartographies of the Absolute started out from a shared recognition that contemporary cinema, arts and letters were increasingly populated by projects and works that explicitly thematised the processes, relations and crises of capitalism. We took Fredric Jameson’s anticipatory and schematic pronouncements on ‘cognitive mapping’, first voiced in the mid-eighties, as a rather portable if philosophically-charged theoretical module through which to organise a cumulative, extremely partial and necessarily digressive survey of such works. The speculative hyperbole of the title should be taken with a pinch of irony, especially in view of the truncated, mystifying, regressive or anachronistic nature of many of our specimens and exhibits – but it should also ring with a certain earnestness, the assertion that, contra facile pleas for networked thought and multiplicity, or pious sermonising about the incommensurable and the unrepresentable, the aesthetic and political drive to totalise is a vital one, not least because of the way in which it makes multiplicity, incompleteness, alterity and the limits of representation determinate. In retrospect, as at least for me was brought home by the viewing of Isaac Julien’s installation Playtime, which came at the conclusion of the book’s composition, but which, likely quite illegitimately, I took as the terminus of a certain sequence of explicit thematisations (visual and narrative) of capital and crisis.

...(more)

(PART II)

The book

Cartographies of the Absolute

Alberto Toscano and Jeff Kinkle

zero books

The blog

Cartographies of the Absolute

_______________________

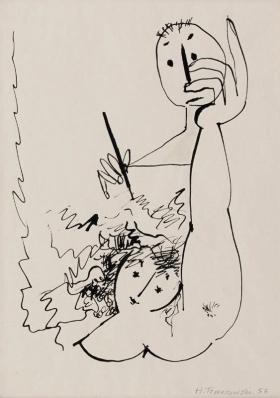

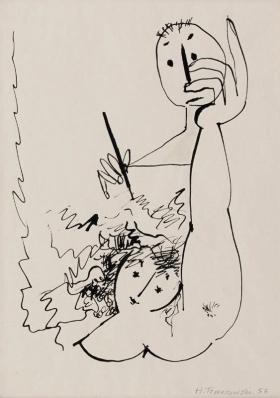

Henryk Tomaszewski

_______________________

At least it’s not 1876

Eran Zelnik

At times like these, when the prospect of a hopeful turn of events in local and world affairs seems dim, when fascism seems to lurk behind every corner, and bigotry and racism to fulminate from the mouths of so many, reading history provides a bit of well needed perspective. I recently found a nice piece of perspective in Richard Slotkin’s magisterial The Fatal Environment, which made 1876 seem far worse than today.

According to Slotkin, one decade after the Civil War, America found its redeemer in the figure of Col. George Custer. In a time of economic depression, in which corruption seemed to engulf the government and in which northern Americans grew tired of the plight of freed slaves, Custer’s “Last Stand” became a Christian parable of redemption through sacrifice. Custer died for America’s sins; not for the sin of embracing genocidal tendencies all too eagerly, but rather for its inability to be as great—and belligerent—as it should.

(....)

Are we in a similar place today? Are white resentful American men looking in vain for their own youthful Custer figure with golden locks? If so, how disappointing must it be that only Donald Trump and his curious looking hair loom on the horizon? If we are witnessing a new political realignment, as that of 1876, we can only hope for—and must fight for—a much better deal for non-white men than America received during that terrible year. ...(more)

_______________________

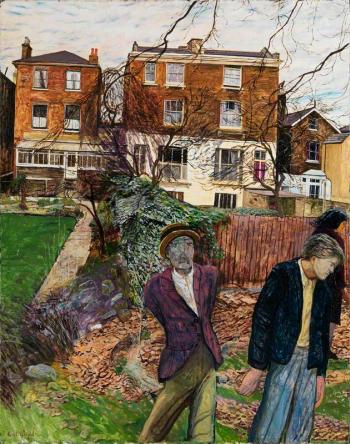

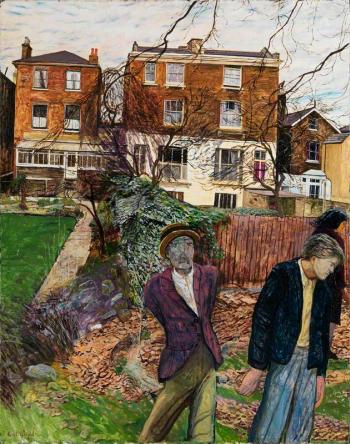

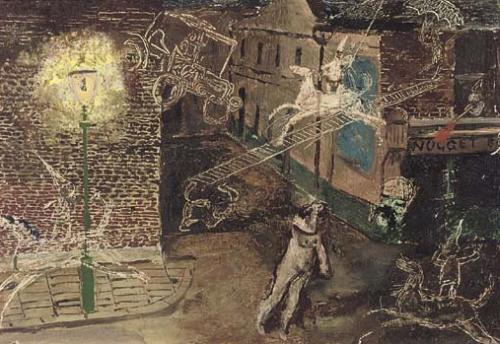

Thomas Merton

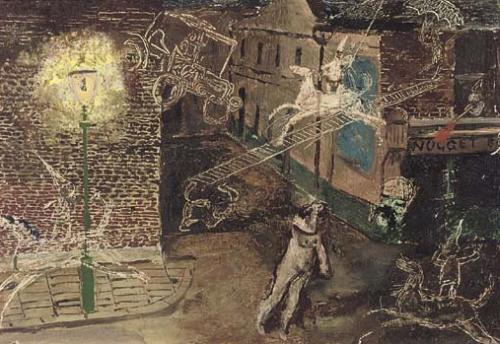

The World We Live In

Carel Weight

b. September 10, 1908

_______________________

The Grand Conversation

Paul Muldoon

She. My people came from Korelitz

where they grew yellow cucumbers

and studied the Talmud.

He. Mine pored over the mud

of mangold- and potato-pits

or flicked through kale plants from Comber

as bibliomancers of old

went a-flicking through deckle-mold.

...(more) .....................................................

Interview with Paul Muldoon [pdf]

David-Antoine Williams

(....)

D-AW: … dictionaries tend to anonymize those authors, and at the same time tend to claim all sorts of authority for themselves. And I wonder whether in reading the dictionaries—I suppose you’ve talked a little about this in the case of Irish etymologies—whether you have the sense of the human intelligence behind the thing, the hand of the lexicographer either making mistakes or not making mistakes, or whether that sort of disappears into the presentation.

PM: Well, I appeal to the OED as a source on which for the most part one may rely. Certainly in the particular edition that I use most of the time. Though I am using this Collins Dictionary a lot more, because a lot of the usages that I would be interested in, you’re only going to get them in a quite up- to-date dictionary. I’ve never really been into the OED Online. Maybe I should. I think I might even have a link to it. But I haven’t used it once. It’s the physicality of the book that I like. It’s a matter of pages I suppose. I like poking about through a dictionary. Having gone to look up a particular word, then I look at this other word, then I look at all these other words on the page and I think, ‘my God’, you know? I realize I know nothing whatsoever about the English language. Even though I know quite a bit about it, I suppose. Compared to many people I have probably quite a large vocabulary. A lot of it is obsolete and all the rest of it but … I just enjoy playing around in there. It’s one of my hobbies.

(....)

... despite what the OED would say, or is likely to say, if it were dealing with a proper name like Eglish, there’s a strong likelihood that an older version of the OED would say ‘Well, that can’t possibly have anything to do with the word ecclesia’. Just as they would be likely to refute that there’s any connection between the Irish word espoc and the word episcopus, or the Irish sacaire, which is the same as sacerdos. Those are interesting because one can divine why these connections are what they are, if only because of the influence of the Church in Ireland. So there’s some revelation to be had in an understanding of the connection between words and languages.

(....)

D-AW: There’s a line where etymology and translation converge, since etymologies at some point cross a threshold into another language, are as it were ‘translated’ into English.

PM: Yes that’s right. Don’t you think that most writers would tend to be interested in how words come to be used in the way that they are? I don’t know if one necessarily has to be, to be a writer. But I think that the more one knows in general I’d say the better. One doesn’t necessarily have to dwell upon it or muse upon it. One isn’t dwelling upon the etymology of every word one is using. On the other hand there may be something under the surface connecting this word and that word over there, in terms of the vertical aspect of language as much as the horizontal. I’m sure that it has to do with root systems and connections that are not necessarily obvious but allow things to flourish in the natural world. Because there are connections that are not necessarily visible. I was up here this morning where they’re working on the new Tube station. They’ve build a system sending cement out while they’re excavating so that it underpins the other buildings around the site, which might otherwise collapse. So there’s that kind of unseen connection between things, just as there’s an unseen structure that’s being set up in this building up the street here, that’s going to hold it up. And I think sometimes those connections may be in the language.

(....)

The Life of Words

Poetry, Lexicography, and Computing David-Antoine Williams

_______________________

Carel Weight

_______________________

Vallejo and The Trials of Translation:

The Erasure of Logopoeia

Jonathan Mayhew

Stupid Motivational Tricks / Bemsha Swing

What would happen if I approached César Vallejo in a way parallel to my treatment of Lorca in my 2009 book Apocryphal Lorca: Translation, Parody, Kitsch—using similar analytical and theoretical tools but adjusting them to the case at hand? That is the question I would like to pose in my talk today. Like Lorca, the Peruvian poet had a strong presence in US poetry in the 1960s and ‘70s, and has continued to be studied and translated by eminent poets and scholars in the years since. The boom for “Latin American surrealism,” often neither Latin American nor surrealist, made both poets famous (at least among readers of poetry) in the English-speaking world, along with a handful of others like Borges, Neruda, Machado, Jiménez, and Aleixandre. This boom in poetry translation begins in the late ‘50s, a few years before the “boom” in the Spanish American novel began to produce abundant translations of García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Cortázar, and others. The idea of Latin American surrealism, in fact, prefigures later understandings (or misunderstandings) of “magical realism,” which remains a prevalent cultural cliché in the reception of Latin American literature in the Anglosphere.

(....)Pound himself stated explicity that logopoeia was the hardest kind of poetry to translate, but instead of simply ignoring it he developed modes of translation specifically designed to address its inherent difficulties. To simplify greatly, his translation of Chinese poetry in Cathay is oriented toward phanopoeia, or visual imagery; his work on Troubador poetry is oriented toward melopoeia; an example of his interest in logopeia would be his Homage to Sextus Propertius. Lawrence Venuti argues that Pound’s translation practice is modernist, oriented toward making the translator visible again, unlike what Venuti takes to be the standard practice of translation in the English speaking world: the creation of a new text that reads smoothly and unproblematically in the target language.

...(more)

The plot thickensJonathan Mayhew

Prevalent translation practices have had a difficult time dealing with Vallejo's brand of modernism. At the same time, his poetry prods translators into taking into account these other aspects of the poetic art. Vallejo’s avant-garde poetry is heavily dependent on logopoeia, or to poetic effects that are purely verbal, rather than on phanopoeia, the evocation of visual images. These effects include punning and other forms of verbal or orthographical play, shifts in register, neologisms, scientific terms, the use of words for their etymology, the wrenching of words from their normal contexts of usage, linguistic patterning (for example, the accumulation of reflexive verbs in certain poems), the exploitation of enjambment for dramatic value, and the proliferation of rhetorical figures, including but not limited to antanaclasis, antithesis, metonymy, catachresis, and anaphora. Rhetoric itself might be a synonym for logopoeia, but I prefer the term logopoeia because it is more oriented toward a particularly modernist deployment of linguistic resources.

...(more)

_______________________

Carel Weight

_______________________

As

Paul Muldoon

As naught gives way to aught

and oxhide gives way to chain mail

and byrnie gives way to battle-ax

and Cavalier gives way to Roundhead

and Cromwell Road gives way to the Connaught

and I Am Curious (Yellow) gives way to I Am Curious (Blue)

and barrelhouse gives way to Frank’N’Stein

and a pint of Shelley plain to a pint of India Pale Ale

I give way to you.

(....)

As vent gives way to Ventry

and the King of the World gives way to Finn MacCool

and phone gives way to fax

and send gives way to sned

and Dagenham gives way to Coventry

and Covenanter gives way to caribou

and the caribou gives way to the carbine

and Boulud’s cackamamie to the cock-a-leekie of Boole

I give way to you.

As transhumance gives way to trance

and shaman gives way to Santa

and butcher’s string gives way to vacuum pack

and the ineffable gives way to the unsaid

and pyx gives way to monstrance

and treasure aisle gives way to need-blind pew

and Calvin gives way to Calvin Klein

and Town and Country Mice to Hanta

I give way to you.

...(more)

.....................................................

Interview with Paul Muldoon

Alice Whitwham

The White Review

(....)

The White Review — You’ve written music for lyrics before…

Paul Muldoon — Yes: you’re right. For The Handsome Family – who are absolutely brilliant. I wish what I’d done with them is better than it is. I love them. They’re wonderfully wacky, with skewed visions of the world, and that is something I’m interested in. The oblique way of thinking about things is almost inevitably more interesting, and that I suppose is what we talk about when we talk about being in touch with one’s own unconscious. One may cultivate that to some extent. One may keep an eye out for the odd expression, the odd image, the striking image, so in that sense one may educate oneself.

It is about being in the habit of ignorance. I love the descriptions – by some of the great poets – of this condition. Wordsworth calls it ‘wise passiveness’; you’re sort of lying there in a heap, but not a total heap, you know?

Great poems come from that area: ignorance. When I teach at Princeton, for example, I tell my students, ‘What we want to really work on now, is what you don’t know: the condition of not knowing.’ There are many people who write poems who’ve not got their heads around this idea, and who actually think that they know what they’re doing. I really believe that the minute one thinks one knows what one’s doing – actually, in any department of life – one’s probably making a terrible mistake. That’s the most difficult thing to teach and the most difficult thing to learn. It’s very tempting for us to think we know what we’re doing.

...(more)

_______________________

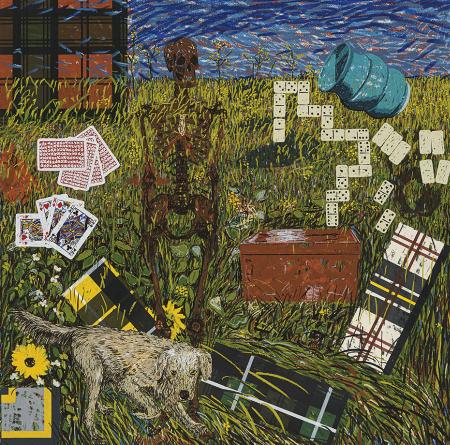

Hammersmith Nights

Carel Weight

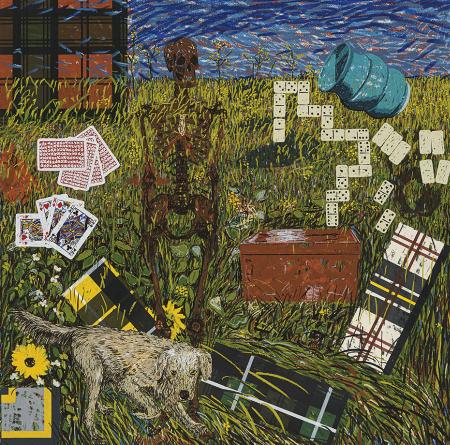

Autumn

Four Seasons, 1990-1993

Jennifer Bartlett

1941 - 1990

_______________________

Eight quotations on loneliness

Jacob Wren

A Radical Cut in the Texture of Reality

(....)

Loneliness is the deal. Loneliness is the last great taboo. If we don’t accept loneliness, then capitalism wins hands down. Because capitalism is all about trying to convince people that you can distract yourself, that you can make it better. And it ain’t true.

-Tilda Swinton

(....)

I have been trying, for some time now, to find dignity in my loneliness. I have been finding this hard to do. It is easier, of course, to find dignity in one’s solitude. Loneliness is solitude with a problem.

- Maggie Nelson

...(more)

via Forgottenness_______________________

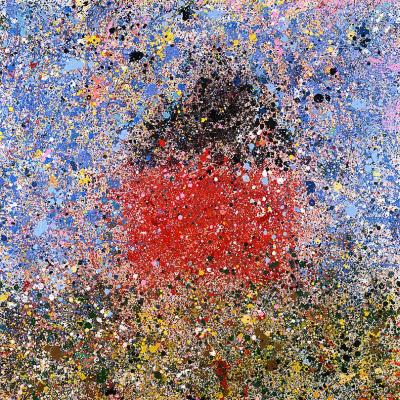

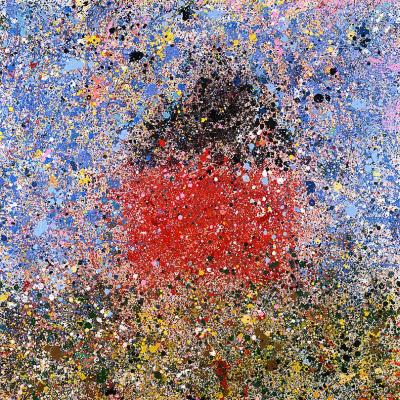

House: Spatter Painting

Jennifer Bartlett

1998

_______________________

Translation assists you in arriving at recognitions. As a translator, you feel your way through to some of the same recognitions that the poet originally had and that shaped the poem. For me, this sense of pursuing recognitions--of waiting for recognitions to arrive--is what poetry and translation are about.

So the process of translation has helped me immensely in that way: not as a question of language, but rather as a quest for recognitions.

The Translator as Geologist: W.S. Di Piero's "Quest for Recognitions"Center for Translation Studies

(....)

JR: Let me just pursue some issues of translation here: the relation between your translations and the critical positions on translation that you've developed in essays such as "On Translation: A Reply to Hans Magnus Enzensberger" [in Memory and Enthusiasm].You believe that Enzensberger's advocacy of an "international style" in translation is misconceived because a homogenous "world style" bleaches the poet of his cultural particularity. Could you elaborate on your position--and especially on how it is reflected in your own translations?

DP: If the poet is worth translating, it's because there's an idiosyncratic character to his or her language--not necessarily extreme, like [Gerard Manley] Hopkins or [Emily] Dickinson--but a place from which it comes:a local character, a sense of place or a region out of which the poetry issues. The feeling-tone of all that needs to be translated. And what bothers me about the positions of Enzensberger, and the position that Charles Simic and Mark Strand took in their introduction to an anthology of translation, is that they don't take sufficiently into account those feeling tones. That's my quarrel. They drain the poetry of those feeling-tones; they pay insufficient respect to the local culture and ideolect of the poem.

As far as my own translations are concerned, let me take Sinisgalli as an example. He writes in a relatively plain style, but there are surrealist tics in it, especially in the poems in which he deals with his childhood village in the south [in Lucania].When he writes about that place, there is a richer, quirkier texture of sound and feeling.And that requires a more inventive, expansive response from a translator. To get those same feelings of affection, celebration, and mourning into appropriate English is quite a task.And if you miss that by settling for a plainness of statement, you're losing so much. You may come up with something à la lettre, which may mirror the original, but it doesn't really work.

...(more)

_______________________

The Words

W. S. Di Piero

threepenn review

When they were young, tender-tough, exposed,

desiring experience but not knowing they desired,

words lived in small dense neighborhoods as sounds

without meaning, but street smarts shaped them

into a kind of plainsong that in time cried itself

into language, a pond-scum shape of sentences,

dragonflies, red dragonflies, and toads and reeds,

the longer the sentences, the more the words

wished for and wanted to claim, the more they felt

like stuff, like honeycomb and hair combs,

billyclubs, skinks, cardboard, silks, and concrete,

and soon became the things they said they were,

...(more)

W. S. Di Piero

_______________________

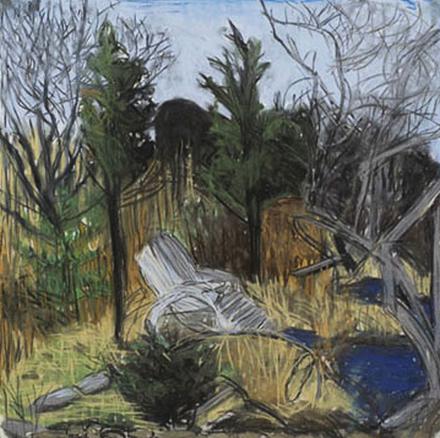

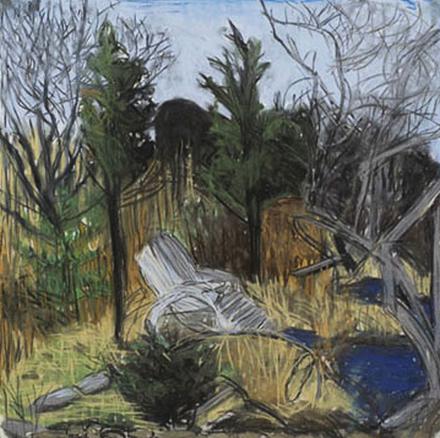

Amagansett Drawings

Jennifer Bartlett

_______________________

Introductory

Toward an Aotearoa Poetic?

Vaughan Rapatahana

jacket2

A few years ago I wrote a piece entitled Toward an Aotearoa Poetic: a few suggestions about constructing a specifically Aotearoa poetic as opposed to the – then extant – mono-cultural, monolingual, monocentric monotonous model of what poetry is and means to many Kiwis.

Down the track of time somewhat and now living right back bang in the centre of this skinny country, my essential points still remain valid, given that my many generalizations in that piece remain exactly that: the piece requires modification and further reflection. It was never meant to be an ‘academic’ item either.

More recently, I do wonder if there ever could be such an all-encompassing poetic across the wide strand of poetry scenes & scenarios thriving both through the midriff and along the lengthy limbs of Aotearoa – poetry slams, for example, are de rigeur here nowadays. Are there just too many discourses, audiences, markets, methods of publication, venues and ‘schools’ here, given that there is never ever sufficient funding for any of them anyway?

I will – in ensuing Commentaries – attempt to size up these several scenes, so to speak, more specifically, given however that nothing is that clear-cut. Take, for example, Kiri Piahana-Wong – she is not only a Kiwi-Asian poet, but also, of course, a Kiwi-Maori poet. More, she is the fulcrum of Anahera Press, a vibrant and viable small press. Doug Poole is a Kiwi-Samoan poet, runs the fine online poetry machine Blackmail Press, as well as is the kaiwhakahaere (boss) of the Poetry Slam at the thriving Going West Writers Festival every year. Nothing is black and white in Aotearoa poetry, given that white still dominates here.

...(more)

_______________________

At Sands Point #21

Jennifer Bartlett

1986

_______________________

On Cynicism and Comedy:

From Charles Baudelaire and Michel Houellebecq to Slajov Žižek and Barack Obama

Menachem Feuer

berfois

(....)

While the French writers have often done their utmost to deepen their commitment to cynicism by way of comedy, we have seen a different response to cynicism in the United States. And unlike France, this American response has traveled from the charmed world of literature to the public sphere. By way of comedians and even the President of the United States, cynicism has been amplified and addressed through film, television, and the media. But, unlike France, where cynicism holds sway, the literary and public response to cynicism in the USA is different. In many instances cynicism is deemed to be contrary to the American ethos. And perhaps that has to do with the fact that, as the famous Weimar film critic Sigfried Kracauer once argued, while many Europeans are locked into the harsh view which finds that fate and determinism rule over most of our lives, most Americans turn to chance, hope, and freedom as their wellspring of insight and wisdom.

Regardless of their differing views of cynicism, comedy is to be found in both the European and the American responses to cynicism. The question we need to ask is which kind of comedy is most befitting for us today and whether (and how) cynicism has left the annals of literature to the space of media culture. Should we comically address cynicism in such a way as to deepen our sense of the bitterness of the human condition? Or should we, using comedy, address it in such a way as to restore trust in the goodness of humanity and the falsity of cynicism?

These questions, to my mind, are of the most important for us today since the answers we arrive at will affect how we view ourselves, others, and the world.

...(more)

_______________________

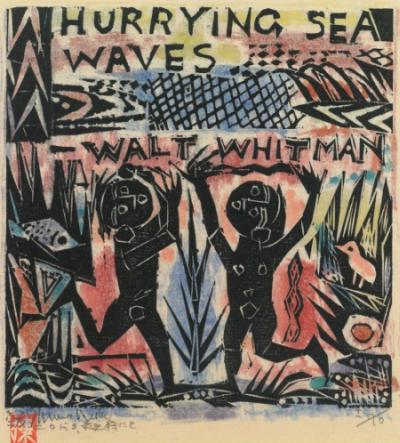

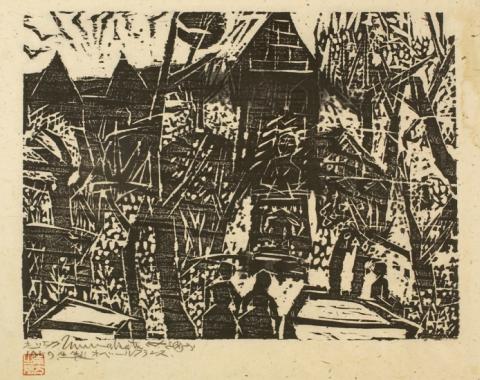

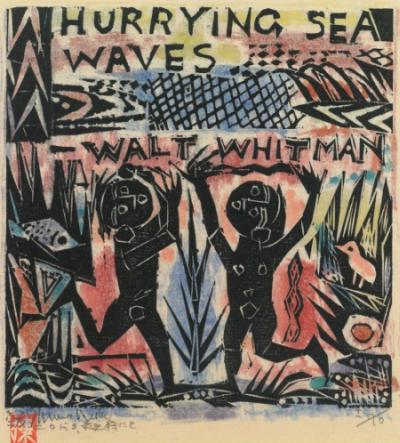

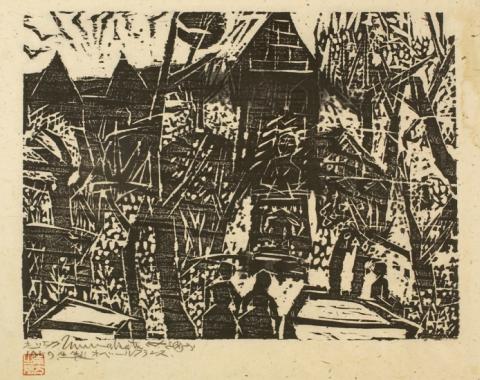

Island

Jennifer Bartlett

Shiko Munakata

b. September 5, 1903

_______________________

In Hell There are no Friends

Spurious

Temporary post. Conference paper delivered at the Society for European Philosophy/ Forum for European Philosophy annual conference at Dundee University.

(....)

So how are we to reflect on these carnivalesque, collective modes, which lie alongside ‘serious’ tasks and projects? What kind of philosophical or paraphilosophical framework is needed to understand or at least to witness the comic art of such interrelations? Here, I aim to follow a little distance the red thread of the concept of friendship, and in particular of intellectual friendship.

(....)

The cultivation of cynicism and opportunism does, Virno allows, generate a kind of free-floating anxiety. But we overcompensate for this through a third emotional tonality, sentimentality, which makes us cleave onto the most clichéd and saccharine glimpses of meaning such that when contemporary friendship is not about the furthering of reciprocal interests, it is the kind of haven that is presented to us in television programmes such as Friends – a retreat from the vicissitudes of adult life onto the sofa in Central Perk, a retreat that is not founded on any shared values and substantial sympathies, but on only the most surface, the most happenstance, the most mawkish of alliances. Such relationships offer mutual reassurance, but of the most contentless kind, such as we find on social media, whether we congratulate one another on our promotions, complain about administration, celebrate the last day of the teaching term, and so on.

But here, the similarity with what Blanchot called the limit-experience should be apparent, except that the impersonal murmuring that used to reveal itself only in weariness and rapture are now all around, even at work. In contemporary society, Virno argues, idle talk is the dominant mode, and the murmuring upon which it draws – the formless and inchoate chaos of words, which used to be the barely audible background of first person speech, has now drowned out the modes of the spoken constitution of subject experience. The heretofore background has come to the foreground of contemporary speech – it is that on which the flexibility of control society is founded. This is what accounts for the rise of the emotional tonalities Virno discusses, since there is no longer a straightforwardly secure and determinate relation between the referents of our speech and the speaking subject. And it is, strange to say, the condition for the superlatively uncreative forms of management-speak that flourish in our universities and everywhere else. Blanchot’s limit-murmuring is the soundtrack to our workplace.

...(more)

_______________________

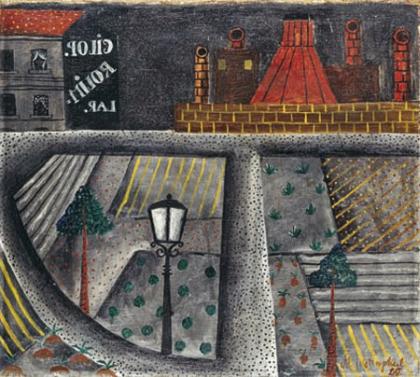

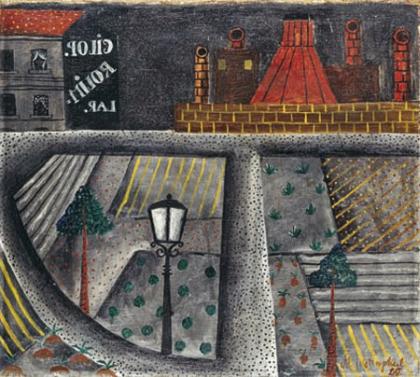

Sorrowful Landscape

André Derain

1946

_______________________

Place-relation ecopoetics: A collective glossary

A work in progress

Linda Russo

jacket2

If we define ‘ecopoetry’ as works that address ecological concerns, and more particularly, in our moment, attempt to account for human activities; and if we begin to list terms that serve as ecopoetic lenses through which to focus and configure the emerging relations and effects of the Anthropocene – activism, bioregionalism, consumerism, ecology, environment(al)(ism), extinction, habitat loss, industiralization, land use, localism, production, sustainability, urbanism, wilderness/wildlife, etc. – it becomes clear that ecopoetry describes a wide and rich and varied terrain, and that, taken together, the writing inscribed under this banner is (among other things) a monument to human responsiveness and invention. Indeed, over the past decade there’s been an ecopoetic blossoming in multiple print and on-line anthologies (or magazine features), new eco-literary magazines, conferences large and small, and myriad individual poetic works and collaborations from various points: North America, the Pacific Islands, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Iceland, to name a few.

...(more)

_______________________

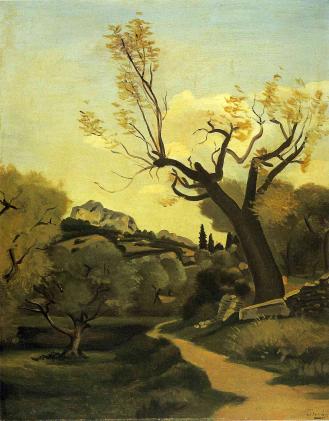

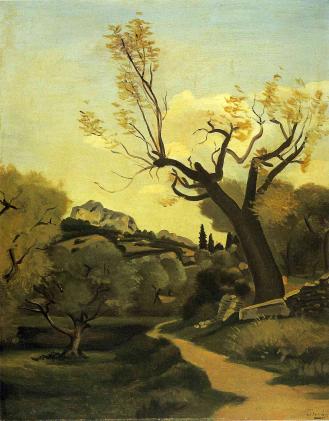

The road and the tree

André Derain

_______________________

Talking about the Spring

Sam Solnick reviews The Oxford Handbook of Ecocriticism, Greg Garrard, editor

(....)

The question form goes to the heart of ecocriticism because, as Richard Kerridge’s essay, “Ecocritical Approaches to Literary Form and Genre”, claims, it makes us think about “reading and evaluating” literature, about what literature does rather than what it is about, about how the art of ecology can be more than agit-prop or educational vehicle. Kerridge asks what we expect from books that engage directly with ecological issues, outlining what he sees as a tension between “urgency” and “depth”, where an “activist sense of urgent purpose co-exists with a more detached analytical approach that seeks to understand the cultural and material interactions at work”. His essay questions the sense that art should engender some sort of Damascene conversion to environmentalism.

Several approaches omitted by Kerridge appear in Adam Dickenson’s fascinating essay. Dickenson focuses on poetry that draws on avant-garde and experimental precursors such as Alfred Jarry and John Cage. Particularly striking is the section called “Transgenic Poetics”, looking at figures who manipulate proteins and DNA as part of their practice, such as the artist Eduardo Kac, who once famously created a luminous albino rabbit by splicing a jellyfish protein into its genetic material; or the poet Christian Bök, who worked with scientists to translate a poem into a genetic sequence that was then inserted into a bacterium’s genome. Bök’s poem, “as a set of genetic instructions, causes the organism to produce a protein which, according to the chemical code used in the experiment constitutes another legible poem”.

Such rewritings of a genetic “text” take the notion of “experimental poetry” to a new level, one that is challenging and troubling, but also scientifically and philosophically informed. Like much contemporary ecocriticism, these artworks speak to a growing awareness that phenomena like climate change, genetic engineering, environmental injustice and a host of other factors rupture our sense of what nature is, or will be – or never has been. In the face of these disorientating realizations, the artistic and scholarly communities have to find new ways of understanding their world, and also of changing with it. The Oxford Handbook of Ecocriticism shows how that process is already well under way in the humanities as well as the sciences.

...(more)

_______________________

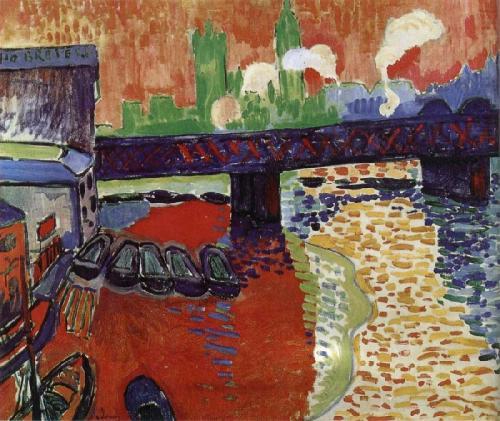

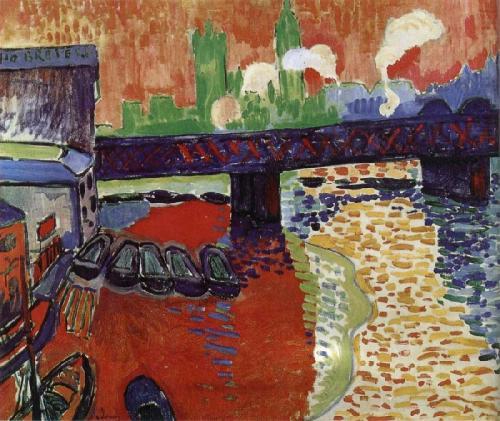

Charing Cross Bridge

1906

André Derain

d. September 8, 1954

_______________________

from &: A Serial Poem

Daryl Hine

(....)

&

Immured in a single-occupancy cell,

Each day indistinguishable from the next,

& nearly inextinguishable, perplexed

How all manner of things shall nevertheless be well,

Will a celibate selfish as a shellfish spell

Out a corrupt & uncorrected text

So that each deleted syllable counts?

Solitude is helpless to dispel

Questions as exceptionably vexed

As unaccountable love’s unaudited accounts.

&

To keep your cell the way you keep your soul,

Untidy-minded, neither soiled nor sold

For next to nothing, a treasury of old

Notions like the notes of a piano-roll

Which cannot improvise though it knows a whole

Repertoire, what ought one to withhold?

Idiosyncrasy is nobody else’s business.

Of all omens the soul provides the sole

Depository. How many oceans can it hold

In its infinite & unfathomable isness?

&

...(more)

.....................................................

Daryl Hine

1936–2012

.....................................................

What About Daryl Hine?

The poet the CBC and Partisan both missed

Brooke Clark

AS PART OF their celebration of Poetry Month, the CBC recently presented a list of “10 classic poetry collections every Canadian should read.” Partisan then responded with its own list of “11 Canadian poetry classics.” Both lists contained some fine poets—Peter Van Toorn and Alexandra Oliver stood out for me on Partisan’s list. But both also missed Daryl Hine, Canada’s most accomplished and least-known poet—a remarkable trick to pull off. Has there ever been another Canadian writer who rated an obituary in The New York Times but not in The Globe and Mail?

...(more)

A Neglected Master in Our Midst: Bill Coyle on Daryl Hine

John Barton in Conversation with Evan Jones about the Late Daryl Hine

malahat review

_______________________

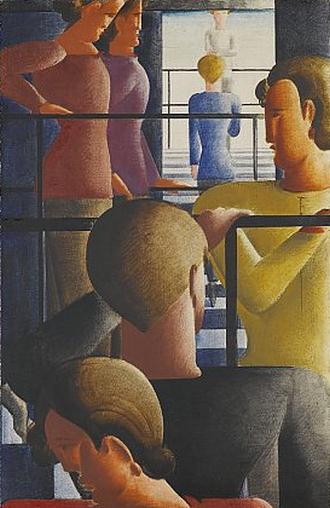

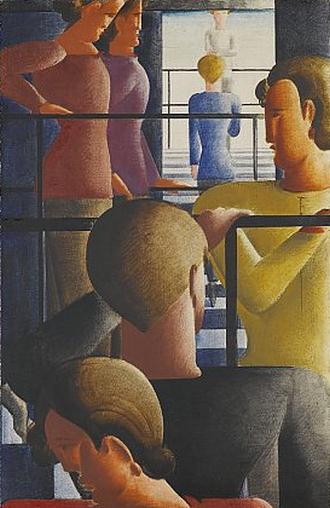

Figures and temple

1959

Shiko Munakata

Scene at Banister

Oskar Schlemmer

b. September 4, 1888

_______________________

STEPS [pdf]

Robert Kelly

the thirty-seventh in a series of texts and chapbooks published by Metambesen

STEPS 5: ALETHEIA

for Charlotte

You are what is not forgotten

the opening of the first door

you are what I have not forgotten

you are what I will remember

you will be the always and the next thing and the again

opening of the second door

sometimes people remember music

sometimes people remember

sometimes the pianist forgets the keys

forgets what white means

and what does black mean

and why are they so small

and far away, or she remembers them

but forgets what’s she’s supposed to say

what is music supposed to say

what does music say

the opening of the third door

sometimes she forgets her hands

sometimes the hunter

stands in the woods at dawn

wondering why he’s there

he forgets what his business is

and why he has a shotgun in his hands

an arrow in his fingers, why

does he study the vanishing darkness

for a hint of something moving

he forgets he is the only person in the woods

the only person in the world

opening of the fourth door

when you know you’re the only person in the world

it all depends on you

this is the moral universe

that penetrates our world like a sheet of light

(....)

_______________________

Oskar Schlemmer

_______________________

I am not a story

Galen Strawson

(....)

The tendency to attribute control to self is, as the American social psychologist Dan Wegner says, a personality trait, possessed by some and not others. There’s an experimentally well-attested distinction between human beings who have what he calls the ‘emotion of authorship’ with respect to their thoughts, and those who, like myself, have no such emotion, and feel that their thoughts are things that just happen. This could track the distinction between those who experience themselves as self-constituting and those who don’t but, whether it does or not, the experience of self-constituting self-authorship seems real enough. When it comes to the actual existence of self-authorship, however – the reality of some process of self-determination in or through life as life-writing – I’m skeptical.

In the past 20 years, the American philosopher Marya Schechtman has given increasingly sophisticated accounts of what it is to be Narrative and to ‘constitute one’s identity’ through self-narration. She now stresses the point that one’s self-narration can be very largely implicit and unconscious. That’s an important concession. According to her original view, one ‘must be in possession of a full and explicit narrative [of one’s life] to develop fully as a person’. The new version seems more defensible. And it puts her in a position to say that people like myself might be Narrative and just not know it or admit it.

In her most recent book, Staying Alive (2014), Schechtman maintains that ‘persons experience their lives as unified wholes’ in some way that goes far beyond their basic awareness of themselves as single finite biological individuals with a certain curriculum vitae. She still thinks that ‘we constitute ourselves as persons… by developing and operating with a (mostly implicit) autobiographical narrative which acts as the lens through which we experience the world’.

I still doubt that this is true. I doubt that it’s a universal human condition – universal among people who count as normal. I doubt this even after she writes that ‘“having an autobiographical narrative” doesn’t amount to consciously retelling one’s life story always (or ever) to oneself or to anyone else’. I don't think an ‘autobiographical narrative’ plays any significant role in how I experience the world, although I know that my present overall outlook and behaviour is deeply conditioned by my genetic inheritance and sociocultural place and time, including, in particular, my early upbringing. And I also know, on a smaller scale, that my experience of this bus journey is affected both by the talk I’ve been having with A in Notting Hill and the fact that I’m on my way to meet B in Kentish Town.

Like Schechtman, I am (to take John Locke’s definition of a person) a creature who can ‘consider itself as itself, the same thinking thing, in different times and places’. Like Schechtman, I know what it’s like when ‘anticipated trouble already tempers present joy’. In spite of my poor memory, I have a perfectly respectable degree of knowledge of many of the events of my life. I don’t live ecstatically ‘in the moment’ in any enlightened or pathological manner.

But I do, like the American novelist John Updike and many others, ‘have the persistent sensation, in my life…, that I am just beginning’. The Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa’s ‘heteronym’ Alberto Caeiro (one of 75 alter egos under which he wrote) is a strange man, but he captures an experience common to many when he says that: ‘Each moment I feel as if I’ve just been born/Into an endlessly new world.’ Some will immediately understand this. Others will be puzzled, and perhaps skeptical. The general lesson is of human difference.

...(more)

_______________________

Oskar Schlemmer

_______________________

The Fictions of Finance

Toral Gajarawala

This stuff is so esoteric that the only people who understand it are in the business. . . . Can you imagine the people on a march against finance? The guy on a megaphone shouting: What do we want? And everyone answering: Specific curbs on short selling in certain circumstances!

—In the Light of What We Know

What happens to culture in the age of finance capital? What happens to the fictions we create in an era when money—harnessed by a range of new, sophisticated, and increasingly abstruse financial instruments—begets money on a scale that Marx could scarcely have imagined? As the production of wealth is further and further removed from the production of things, billions of people’s lives are tied up in financial markets shrouded in a haze of mystery. It is no surprise, then, that culture in the age of finance capital is wrestling precisely with what we know but cannot always see.

Fiction has become accustomed to the question of money—to the everyday dealings of credits and debts, trinkets bought and sold, the price of milk. In Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, the drama circles around $9,000 (the beautiful Lily Bart’s gambling debts); in John Updike’s “A&P,” it is 49 cents (the cost of fancy herring in a can); in Saadat Hasan Manto’s aptly named story, it is “Ten Rupees” (the price of a young girl). Beyond dollars and cents, the novel, historically, has been in turn dazzled by, and critical of, the crush of capitalism, the rapid accumulation of wealth, and the exploitation of labor, all documented and turned over by writers ranging from Balzac and Zola to Dos Passos and Dreiser. But the scale now seems vaster—not dollars and cents but hidden millions, the millions that underwrote the sugar plantations (as Edward Said writes of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park) and that now circulate farther and faster than ever but are even more difficult to see.

...(more)

_______________________

Oskar Schlemmer

_______________________

Almost Lovable

Sheila Fitzpatrick reviews Landscapes of Communism: A History through Buildings by Owen Hatherley

(....)

I’ve noticed before the strange tendency of hateful buildings to become almost lovable after the passage of decades. Not all of them, of course. Some, like the 1960s highrise clones lining Moscow’s New Arbat (Kalinin Prospekt) become more annoying as they get shabbier. But the Moscow State University building on Lenin Hills, one of Moscow’s seven late-Stalinist wedding cakes, has definitely undergone a metamorphosis in my mind. When I lived there in the late 1960s, I regarded it as an anti-people monster, guarded by dragons who, if you had lost your pass, would throw you out to die in the snow. (According to Hatherley, they now use swipe cards to protect the building against invasion.) But I noticed a while back that I had started regarding the wedding cakes with something like affection; apparently the passage of time has naturalised them.

But Hatherley is young, and so are the Poles who like the Palace of Culture; their reassessment must come from somewhere else. Actually it seems to come from two different places. One is the Western pop/youth phenomenon that might be called Soviet ruin chic – a fascination with Soviet imperial ghosts or, as Hatherley puts it, ‘tourism of the counter-revolution’. Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker, with its memorable imagery of the Zone, is a reference point here, as is real-life Chernobyl, now a tourist destination for those with a ‘ruin chic’ sensibility. Hatherley distinguishes his own position from that of the admirers of Totally Awesome Ruined Soviet Architecture, and his ideological and personal baggage is definitely not counter-revolutionary. But there’s some family – or perhaps more accurately, generational – resemblance.

The other place this re-evaluation comes from is Eastern Europe, specifically young people who grew up in the Soviet bloc at the end of the communist era, and don’t share their parents’ bad memories. Hatherley travelled around the old Soviet empire with his Polish partner, Agata Pyzik, who in 2014 published her own take on East-West culture clashes, Poor but Sexy. Freelancers in their early thirties, they live with one foot in London and the other in Warsaw. Agata is the one with Russian and, as a reading of Poor but Sexy suggests, a penchant for film and cultural theory. Hatherley is the one with the eye, the architectural knowledge, and a childhood background in Militant Tendency. They make an entertainingly observant couple as they wander round Moscow, Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Budapest, Vilnius, Kiev, Riga, Tallinn, Bucharest, Sofia and the rest, on the look-out for good cheap meals as well as striking cityscapes and ‘weird’ (a favourite word, generally approving) buildings.

...(more)

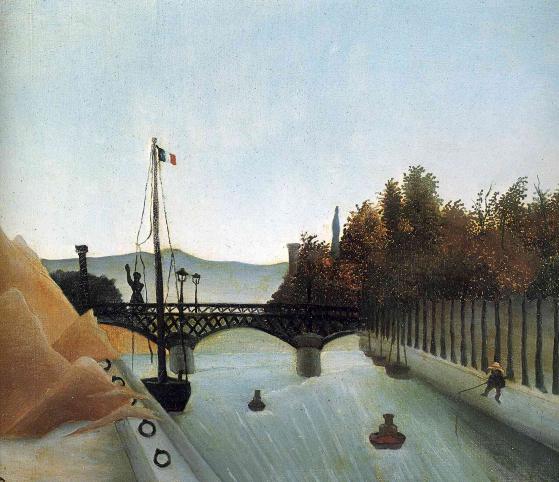

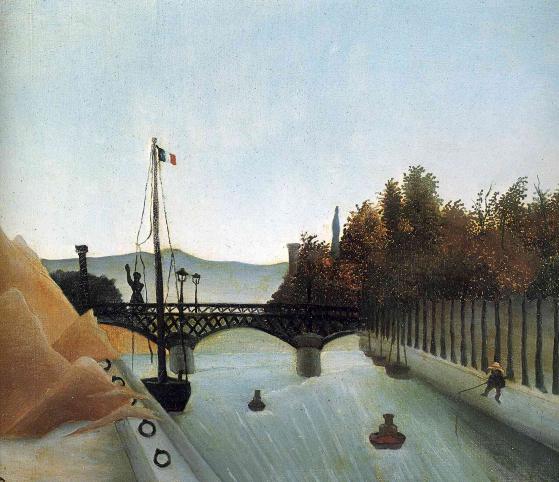

Footbridge at Passy

Henri Rousseau

d. 02 September 1910

_______________________

Poetry and the Memory of Fame

On accidental anonymity.

Thomas Mccarthy

(....)

This high companionship of self-indulgence is hugely underrated in modern teaching. It needs to be taught again. Poetry, the best poetry, the most purposeful poetry, arises out of the fullness of the self. It is not the result of a given program, an agenda, a canon. The dynamic noise of a poetry workshop, its communal imperative, does compel young poets to be clear rather than complex, to be social rather than desolate. But the best education in the poetic art must oscillate between the two — between the need to dream fiercely and the need to communicate. Our personal temperament is an essential part of our technical equipment as poets: it is the one part of our equipment that we cannot teach to others, though many of us yearn to do so as we grow older. Our temperament is the thing that will die with us, leaving traces only in the best work. Technically — I mean from the standpoint of writing new poems — all the historic suffering of the Irish nation has no more moral weight than the anonymous cadaver on the dissecting table of Gottfried Benn. The materials available to a new poet are that simple, that open, that personal. Have courage, I would say to any new poet; have courage while your poem invites you into itself. This fullness of being — the vain clarity before a poem begins — must have been what the twenty-five-year-old André Gide meant when he wrote in his Journals:

The most beautiful things are those that madness prompts and reason writes. Essential to remain between the two, close to madness when you dream and close to reason when you write.

In other words, the fullness of your self is available from the start: dig into it with your pen, exploit it. For poetry’s sake, keep dissecting the self until you find the infection that is interesting. Be open to technique, I advise younger poets; by all means, learn everything new that can be learned about a poetic effect, about what the phrases do when they are layered together on the page. Understand that a poetic tone shared and recognized across the English language is part of the Esperanto of our modern era — we search for a tone that reassures us of the author’s modernity. Far from avoiding new work from young writers, most editors yearn to find something new, yet something with an assured and seriously polished tone. But temperament, the personal atmosphere of your life as a poet; that is something the gods have given you at birth — throw a security cordon around it — it is yours for life, through all the fame and, more usually, the persistent absence of fame.

...(more)

via The Page

_______________________

Henri Rousseau

_______________________

Our Book of Failures

Lisa Donovan

We are in a middle land. In the middle land there’s no counting, no chanting. In the middle land there’s no scratching, no licking, no shuffling of feet. Here, in the middle, we talk about the breeze; this breeze, here. We are in the middle land and there’s no one here—not me, not you. Here in the middle land we change our figures out of this into sand. From sand we fall—we are falling. In the middle land we are without telling. In the middle land there are only questions. We question, here, in the middle land. In the land we are without speaking. What does it mean to speak? We are in the middle land. There’s no light. What is light? Are you in the middle land? You are in the middle land. You don’t know light, don’t know dark. You, in the middle land, don’t know speech—are without name. What name? No name. You are collapsing, no, collapsed in the question. What does it matter? In the middle land you are here. You have never arrived. You are. You are. You are. In the middle land you are sand. We can talk only of the breezes. Hush now, we haven’t yet slept, are now sleeping. That’s a lie.

...(more)

_______________________

Henri Rousseau

_______________________

Donald Trump, Countersubversive Demonologist

Kurt Newman

S-Usih.Org

(....)

In so many ways a book ahead of its time, Ronald Reagan: The Movie, And Other Episodes In Political Demonology (Michael Rogin) provides the contemporary scholar with all of the tools necessary to situate Trump as a Populist. Rogin’s focus is on a certain tendency in American political theology that he calls “countersubversive demonology.” Ronald Reagan––failed movie cowboy, enthusiastic Hollywood Red hunter, relentless fantasist of latter day Central American Plans San Diego––serves as the anchor of Rogin’s text. But Rogin deftly moves from the Iran-Contra hearings to Jacksonian bloodlust, from the Frost/Nixon interviews to the anti-Catholic and anti-Masonic manias of the nineteenth century: discovering extraordinary continuities among varied efforts to weed out threats to the body politic by developing detailed knowledge about demons, monsters, and ghouls.

Ronald Reagan: The Movie, And Other Episodes In Political Demonology is also a comparatively early example of a work of American historiography that takes seriously Ernst Kantorowicz’s research on the “King’s Two Bodies.” Implicit in Rogin’s discussion is the articulation of the idea of the “King’s Two Bodies” with contemporary theories of biopolitics (the various analytical projects that take their cue from Foucault’s insistence that in modern political formations, the human body tends to become the medium of state power). Countersubversive demonology feeds off of the oscillation between the two bodies with which sovereignty is concerned: the body politic and the given fleshly body of the subject. A threat to one is a threat to the other; porousness or vulnerability to pollution of my body becomes a crisis of the state’s abstract body; the unwalled border between the United States and Mexico becomes something like an anti-vaccination.

Not all countersubversive demonologies are Populist. And not all Populisms are countersubversive demonologies. But Populism and countersubversive demonology work very well with one another. The process is described elegantly in the writings of Claude Lefort and Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. If we begin with the idea of the “King’s two bodies,” taking that split between abstract sovereign being, on one hand, and the ordinary reality of people, on the other, as constitutive of the political form called the state, we can identify the “problem” that Populism seeks to fix. Many experience the gap between the “King’s two bodies” as traumatic: tremendous libidinal energies can be mobilized around the project of closing the split, making “America,” for example, exactly identical to America (the complex entity in which some of us live). The work of closing this gap between the two “Americas” requires an object around which intentions may be organized. We might say that the relative virtue of different strains of Populism follows from the character of the chosen object and the choices made by Populist politicians regarding its mobilization.

Countersubversive demonology is what happens when the Populist desire for a positive object-cause fails, when no suitable object can be found. The same intense will for suture, the same drive to erase all remainders, leftovers, or holes from the conflation of “America” and America are at work: but lacking the proper object, attention turns to the alien element that has settled in our midst, working in secret to frustrate the longed-for cohesion. As Rogin notes, this anxious search for the polluting or infecting agent is a will-to-knowledge (and the knowledge it produces tends to have a distinctive, repetitive, compulsive character), The countersubversive demonological imagination, Rogin further observes, is often drawn to mimesis: in order to know the enemy, one must think like the enemy. Thus the extraordinary staying power of reactionary drag in American political life. The strangest thing about this mimesis is that it yields no empathy.

...(more)

_______________________

Carnival Evening

Henri Rousseau

1885

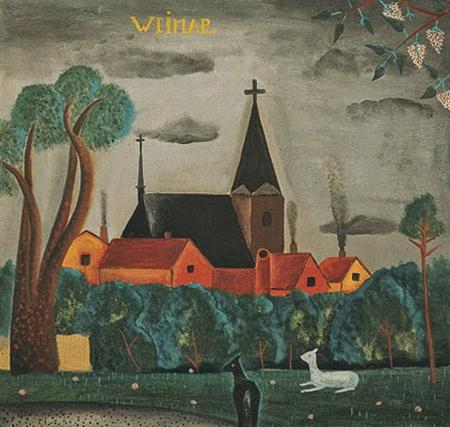

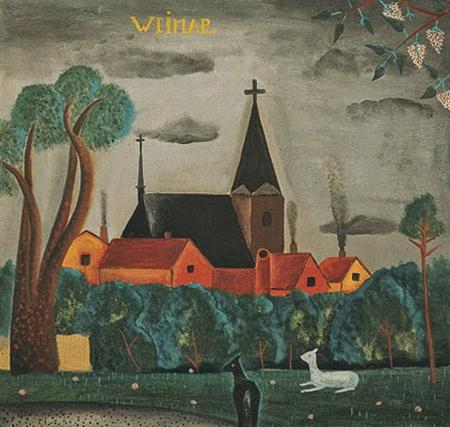

Max Peiffer Watenphul

1896 - 1976

_______________________

Fernando Pessoa: A Disputed Heteronym

Beyond Another Ocean

Notes by C. Pacheco

Translated by Chris Daniels

To the memory of Alberto Caeiro

In a fevered feeling of being beyond another ocean

There were positions of a living more clear and limpid

And apparitions of a city of beings

Not unreal but livid with impossibility, sacred in purity and in nudity

I was the gateway to this null vision and the feelings were only the desire to have them

The notion of things beside themselves, each with their own inwardness

All were living in the life of remnants

And the mode of feeling was in the mode of living

But the form of those faces had the placidity of dew

Their nudity was a silence of forms without means of being

And there was wonder at all reality being only this

But life was life and it was only life

Often my thought works in silence

As smoothly as a greased machine moves without a sound

I feel good when it so moves and I immobilize

So as not to break the equilibrium that allows this to occur in me

I foresee that it is in these moments that my thought is clear

But I do not hear it and it works stealthily and in silence

Like a greased machine driven by a belt

And I can hear nothing but the serene sliding of the parts at work

Sometimes I recall that all other persons must feel the way I do

But they say it gives them a headache or causes dizziness

This recollection came to me as could any other

As for example the recollection that people do not feel the sliding

And they do not think what they do not feel

(....)

Feeling poetry is the supposed way for one to live

I do not feel poetry not because I do not know what it is

But because I cannot live supposedly

And if I managed it I would have to follow another way of conditioning myself

The condition of poetry is not to know how it is one senses it

There are beautiful things that are beautiful in themselves

But the inner beauty of feelings mirrors itself in things

And if they are beautiful we do not feel them

In the sequence of steps I cannot see more than the sequence of steps

And they follow as if I saw them really following each other

By the fact of them being so equal to each other

And since there is no sequence of steps that is not

I see no need to illude ourselves about the clear meaning of things

Otherwise we would have to believe that an inanimate body feels and sees differently from us

And by being too admissible this notion would be uncomfortable and futile

If we are able to cease movement and speech when we think

Is it necessary to suppose that things do not think

If this manner of seeing them is incoherent and easy on the wit?

We ought to suppose and this is the true way

That we think by the fact of our being able to do so without moving or speaking

As do inanimate things

...(more)

My Motto Is: ‘Translation Fights Cultural Narcissism’

Chris Daniels in conversation with Kent Johnson jacket 29

(....)

My Pessoa translations are just as much a heap of scraps as the contents of the famous trunk. While I certainly will be leaving out things here and there, I refuse, in the texts I do translate, to make any sweeping editorial decisions, which always distort the true nature of Pessoa’s heteronymic poetry by normalizing, condensing and cutting; I’m insisting that it be published in all its fissured confusion. Reading Pessoa in a critical edition can be maddening. He’s even more a poet of variants than Emily Dickinson. His celebrated clarity and simplicity are interspersed with false starts, incoherent marginalia, and drunken scrawl that threaten to overwhelm everything... So I allow the uneven, fragmentary odes of Campos to be uneven and fragmentary, and the unfinished poems by Caeiro to be unfinished. It’s only fair that Anglophones be able to experience Pessoa in a way that at least approaches the Lusophone experience. Until this is possible, our understanding of Pessoa will be deeply flawed and his stature as one of the truly great modernist poets will be perceived imperfectly.

...(more)

_______________________

Max Peiffer Watenphul

_______________________

"Suffering is the sovereign common denominator":

Interview with Leon Niemoczynski, part 2

(....)

When it comes to the American pragmatists, for example, philosophical ecology, environmental aesthetics, theories of the body and sensation, theories concerning the environment, theories about habit and embodiment, are still undergoing transformation and change. A lot of what the American pragmatists (and process philosophers, and naturalists) were saying in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries helps to clarify those burgeoning contemporary areas of research happening today. Why not read, modify, and use them to new ends? I mean, just reading Peirce and then flipping to a book written by Deleuze or Meillassoux is a matter of translating the language, but a lot of the ideas and outlook are the same. What Peirce and Meillassoux cover with virtuality and contingency is nearly identical. Metaphysics in the American tradition has always been realist, naturalist, friendly to the rational and natural sciences, is process-oriented, and thus is a great lens certainly to help get clear on the issues of debate today. I would encourage anyone to just dig into some of these figures – especially Whitehead – and see what you find.

(....)

I think living with chronic pain has definitely allowed my thinking to encounter the "bleak" or darkest corners of existential – and even deeper than that, ontological – explanation about suffering itself. Well, there is no "explanation," just indifferent fact that in its own tones of address to humans, or to the living, is dark, within the realm of despair, suffering, agony, melancholy, depression, and bleakness. Just "depths" of agony and the lack of a universe answering back to an explanation for why, or how, suffering is the self-reinforcing motor for life.

(....)

I remember Hartshorne in an interview stating that unlike Schopenahauer he believed that "life in general is basically happy….[S]uffering is secondary and satisfaction primary in the lives of creatures." I disagree with this. This sort of talk, and I've heard this recently, says "Pain is good. It helps us remember we are alive." That's true but only partially true, and if you think that, then you haven't suffered severe pain. I think that this sort of thinking, what Hartshorne said, loses track of what is deeply tragic in the world. For me it directly links to the problem of evil. Pain and evil, suffering, are related.

...(more)

"‘Perceptual universes’ abounding all around of us" : Interview with Leon Niemoczynski, part 1 Speculum Criticum Traditionis

open letters on philosophical praxis

Leon Niemoczynski blogs at After Nature

_______________________

Max Peiffer Watenphul

_______________________

He speaks of myriapod thoughts. Of swarming thoughts, like a disturbed ant’s nest. He speaks of thoughts crawling on a thousand legs. He speaks of thoughts rushing through him like centipedes or millipedes.

He speaks of thoughts thought by chaos inside him. Of thoughts thought by madness inside him. He speaks of thoughts that shouldn’t be. Of thoughts in continuous SOS. He speaks of thoughts of agony that are the source of agony. Thoughts of pain that are themselves pain.

(....)

And what do they want, these thoughts? What do they ask for, these thoughts? What do they ask of him, from him? Are they what he must embrace if he wants to think like a philosopher? Are these philosophical thoughts that swarm inside him? Is it philosophy itself that crawls within him? -

Nietzsche And The Burbs

|