|

photo - mw

_______________________

Charles Tomlinson _______________________

from The Return

Charles Tomlinson

1927 - 2015

IV. The Fireflies

I have climbed blind the way down through the trees

(How faint the phosphorescence of the stones)

On nights when not a light showed on the bay

And nothing marked the line of sky and sea—

Only the beating of the heart defined

A space of being in the faceless dark,

The foot that found and won the path from blindness,

The hand, outstretched, that touched on branch and bark.

The soundless revolution of the stars

Brings back the fireflies and each constellation,

And we are here half-shielded from that height

Whose star-points feed the white lactation, far

Incandescence where the single star

Is lost to sight. This is a waiting time.

Those thirty, lived-out years were slow to rhyme

With consonances unforeseen, and, gone,

Were brief beneath the seasons and the sun.

We wait now on the absence of our dead,

Sharing the middle world of moving lights

Where fireflies taking torches to the rose

Hover at those clustered, half-lit porches,

Eyelid on closed eyelid in their glow

Flushed into flesh, then darkening as they go.

The adagio of lights is gathering

Across the sway and counter-lines as bay

And sky, contrary in motion, swerve

Against each other's patternings, while these

Tiny, travelling fires gainsay them both,

Trusting to neither empty space nor seas

The burden of their weightless circlings. We,

Knowing no more of death than other men

Who make the last submission and return,

Savour the good wine of a summer's night

Fronting the islands and the harbour bar,

Uncounted in the sum of our unknowings

How sweet the fireflies’ span to those who live it,

Equal, in their arrivals and their goings,

With the order and the beauty of star on star.

Charles Tomlinson obituary

Poet and translator who bridged the cultural gap between old and new worlds Michael Schmidt

(....)

DH Lawrence was his witness that “all creative art must rise out of a specific soil and flicker with the spirit of place”, to which Tomlinson added: “Since we live in a time when place is threatened by the violence of change, the thought of a specific soil carries tragic implications.”

John Betjeman said: “I hold Charles Tomlinson’s poetry in high regard. His is closely wrought work, not a word wasted … ” For the American objectivist poet George Oppen, “it is [Tomlinson] and Basil Bunting who have spoken most vividly to American poets”. Tomlinson bridged the vast gulf between old and new world poetry, and was an heir equally of Dryden and Williams, Coleridge and Pound. His 16 collections of poetry, books of essays, translations and anthologies are a core resource for English writers and readers of the last half-century, yet he has been more honoured abroad than at home.

(....)

Repelled by prescriptions – formal, political, religious – he maintained an alert interest in other poetries and other arts: music, architecture, sculpture, painting. He was an accomplished graphic artist. And he never tired of travel in space and language, though he always homed to his cottage in Gloucestershire, and to an English enriched by his translations from the Russian of Fyodor Tyutchev, the Spanish of Antonio Machado, César Vallejo and Octavio Paz, the Italian of Giuseppe Ungaretti and others, and the French poets. Jacques Roubaud, Edoardo Sanguineti and Paz collaborated with him on Renga (1979), a poem in four languages. His translations represented a significant second body of poetic work.

...(more)

_______________________

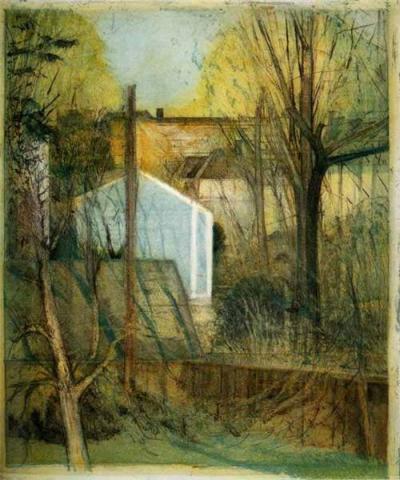

Harvest

1887

Julian Alden Weir

1852-1919

_______________________

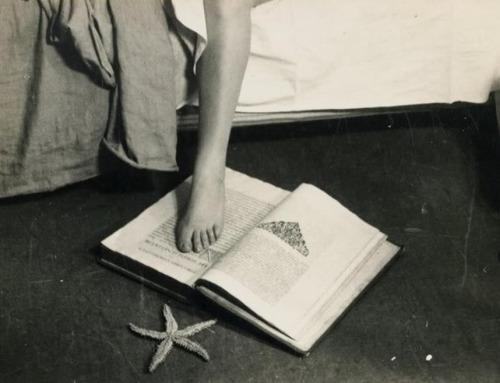

Silence In The Library

Marie Elia

berfois

Naming is powerful. A name can be a gift or a burden. Choosing or discarding a name can make you feel free. A nickname can make you feel loved or crushed. What people call you shapes how you see yourself, and teaches you how to navigate the world. But the moment you name something, you limit the possibilities of what it can be. Librarians and archivists who catalog and describe collections have the great responsibility of choosing names for things that provoke interest and further understanding. We call this “creating access points” – little lights to guide you, from whichever direction you might approach. But what if the roads were built ages ago and are no longer passable? Or what if they lead in the wrong direction? The limits of language, particularly the specialized, slow-to-evolve jargon of cataloging librarians and archivists, can create more barriers than pathways. Naming a thing with the wrong words can cut off various paths; it can silence necessary questions. In a choose-your-own-adventure text, this would be the part where you would die, have to start over again and opt for a different route next time.

I’m an accidental archivist. ...(more)

_______________________

Lengthening Shadows

Julian Alden Weir

1887

Mexico

Man Ray

b. August 27, 1890

_______________________

Melancholy

Carina del Valle Schorske

Melancholy is a word that has fallen out of favor for describing the condition we now call depression. The fact that our language has changed, without the earlier word disappearing completely, indicates that we are still able to make use of both. Like most synonyms, melancholy and depression are not in fact synonymous, but slips of the tongue in a language we’re still learning. We keep trying to specify our experience of mental suffering, but all our new words constellate instead of consolidate meaning. In the essay collection Under the Sign of Saturn, Susan Sontag writes about her intellectual heroes, who all suffer solitude, ill temper, existential distress and creative block. They all breathe black air. According to her diagnostic model, they are all “melancholics.” Sontag doesn’t use the word depression in the company of her role models, but elsewhere she draws what seems like an easy distinction: “Depression is melancholy minus its charms.” But what are the charms of melancholy?

...(more)

The Point Issue 10

_______________________

Man Ray

1928

_______________________

Found in translation: giving voice to those who wrote ‘Hebrew Bible’

Eavan Boland

Irish Times

In the years after the second World War, a generic literary figure emerged. This was the translator. Travel and the aftermath of war had combined to turn a bright light on the necessity for cultural exchange. Texts previously shut away in foreign languages now became available. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s a visible industry emerged. Through small presses and new publications essential writers – Eugenio Montale, Anna Akhmatova, Anna Swir, Christa Wolf and many others – were conveyed to new audiences. “Translators are the shadow heroes of literature,” wrote Paul Auster. And so it appeared.

And then a strange thing happened. As the conversation about new voices in different languages grew louder the conversation about the translator fell into confusion. What was the exact definition of the role? Were translators simply vendors and sifters of words? Mediators between cultures? Something more? Something less? The questions appeared to hang in the air and then vanish. With the result that an essential figure slipped into the shadows even though what George Steiner said remained true: “Without translation, we would be living in provinces bordering on silence.”

These issues and omissions are brought into focus by this book, Strong as Death is Love, Robert Alter’s latest volume of biblical translation. They are also part of what makes him such a remarkable figure. ...(more)

via the page

_______________________

Dust Breeding

Man Ray

1920

_______________________

Green Nihilism or Cosmic Pessimism

Alejandro de Acosta

(....)

This customary speed, which we share with many with whom we share little else, is what necessitates the yes-or-no operation. Whatever the response is, it has to happen quickly. (We are the best of Young-Girls when it comes to the commodities we ourselves produce.) To do something else than mechanically phagocyte Desert (or anything else worth reading) and absorb it or excrete it back out onto the bookshelf/literature table/shitpile, some of us will need to take up a far less practical, far less pragmatic attitude towards the best of what circulates in our little space of reading. In short, it is to intervene in the smooth functioning of the anarchist-identity machine, our own homegrown apparatus, which reproduces the milieu, ingesting unmarked ideas, expelling anarchist ideas. Of course all those online rants, our many little zines, our few books—the ones we write and make, and the ones that we adopt now and then—are only part of this set-up, which also includes living arrangements, political practices, anti-political projects, and so on. All together, from a few crowded metropoles to the archipelago of outward- or inward-looking towns, that array could be called the machine that makes anarchist identity, one of those awful hybrids of anachronism and ultramodernity that clutter our times. But, trivial though the role of Desert may be in the reproduction of the milieu, its small role in that reproduction is especially remarkable given that it directly addresses the limits of that reproduction, and, indirectly, of the milieu itself. Its reception is a kind of diagnostic test, a demonstration of our special obtuseness. If I am right about even some of the preceding, then the increasingly speculative nature of what follows ought to prove interesting to a few, and repulsive to the rest.

(....) ... if our rejection of society and state is as complete as we like to say it is, our project is not to create alternative micro-societies (scenes, milieus) that people can belong to, but something along the lines of becoming monsters. It is probable that anarchy has always had something to do with becoming monstrous. The monster, writes Thacker in another of his books, is unlawful life, or what cannot be controlled. It seems to me the only way to do this, as opposed to saying one is doing it and being satisfied with that, would be to unflinchingly contemplate the thing we are without trying to be, the thing we can never try to be or claim we are: the nameless thing, or unthinkable life. Which is also the solitary thing, or the lonely one. The egoist or individualist positions are like dull echoes of the inexpressible sentiment that I might be that nameless thing, translated into a common parlance for the benefit of a (resistant, yes) relation to the social mass. That the cosmos is not our natural home is a thought outside the ways in which we might survive here. To say we survive instead of living is in part to say that we have no idea what living is or ought to be (that there is probably no ought-to about living). But also that we resist any ideal of life, including our own. Becoming monstrous is therefore the goal of dismantling the milieu as anarchist identity machine. Being witness to the nameless thing, to the unthinkable life or Planet or Cosmos, is not a goal. It is not a criterion of anything, either. It is more like a state, a mystical, poetic state (though in this state I am the poem). It is the climatological mysticism Thacker describes and Desert hints at for an anarchist audience, both deriving in their own way from the weird insight that the Planet is indifferent to us. So read Desert again as an allegory of the self-destruction of the milieu, of any community that, as it runs from its norms, places new, unstated norms ahead of itself. Such is the slippage from green nihilism to cosmic pessimism, which gives us occasion to continue speaking of chaos. Well, one might say that I have merely imported some alien theory into an otherwise familiar (if not easy) discussion. Of course I have. My aim, however, was not to apply it, but to show in what sense one play that is often acted out in our spaces may be anti-politically theorized, which is to say cosmically psychoanalyzed. Our place is not to apply the theory of cosmic pessimism (or any other theory; that is not what theory is, or is for); our place is to think, to continue speaking of chaos, not being stupid enough to think we can take its side. There are no sides. We might come to realize that we, too, in our attempts to gather, organize, act, change life, and so on, were playing in the world, ignorant of the Planet, its unimaginable weirdness.

...(more)

DesertAnonymous

_______________________

How Forests Think:

toward an anthropology beyond the human

Eduardo Kohn

University of California Press

from the Introduction [pdf]

(....)

Footing for the unsteady, a guide for the blind, a cane mediates between a fragile mortal self and the world that spans beyond. In doing so it represents something of that world, in some way or another, to that self. Insofar as they serve to represent something of the world to someone, many entities exist that can function as canes for many kinds of selves. Not all these entities are artifacts. Nor are all these kinds of selves human. In fact, along with fi nitude, what we share with jaguars and other living selves—whether bacterial, fl oral, fungal, or animal—is the fact that how we represent the world around us is in some way or another constitutive of our being.

A cane also prompts us to ask with Gregory Bateson, “where” exactly, along its sturdy length, “do I start?” (Bateson 2000a: 465). And in thus highlighting representation’s contradictory nature—Self or world? Th ing or thought? Human or not?—it indicates how pondering the Sphinx’s question might help us arrive at a more capacious understanding of Oedipus’s answer. Th is book is an attempt to ponder the Sphinx’s riddle by attending ethnographically to a series of Amazonian other-than-human encounters. Attending to our relations with those beings that exist in some way beyond the human forces us to question our tidy answers about the human. Th e goal here is neither to do away with the human nor to reinscribe it but to open it. In rethinking the human we must also rethink the kind of anthropology that would be adequate to this task. (....)

via synthetic zero_______________________

Man Ray

_______________________

Horror of Philosophy

Eugene Thacker

An excerpt from Tentacles Longer Than Night [Horror of Philosophy, vol. 3] (Zero Books, 2015)

3am

(....)

In a world which is indeed our world, the one we know, a world without devils, sylphides, or vampires, there occurs an event which cannot be explained by the laws of this same familiar world. The person who experiences the event must opt for one of two possible solutions: either he is the victim of an illusion of the senses, of a product of the imagination – and laws of the world then remain what they are; or else the event has indeed taken place, it is an integral part of reality – but then this reality is controlled by laws unknown to us.

- Tzvetan Todorov

While Todorov is primarily concerned with analyzing the fantastic as a literary genre, we should also note the philosophical questions that the fantastic raises: the presumption of a consensual reality in which a set of natural laws govern the working of the world, the question of the reliability of the senses, the unstable relationships between the faculties of the imagination and reason, and the discrepancy between our everyday understanding of the world and the often obscure and counterintuitive descriptions provided by philosophy and the sciences. The fork in the road is not simply between something existing or not existing, it is a wavering between two types of radical uncertainty: either demons do not exist, but then my own senses are unreliable, or demons do exist, but then the world is not as I thought it was. With the fantastic – as with the horror genre itself – one is caught between two abysses, neither of which are comforting or particularly reassuring. Either I do not know the world, or I do not know myself.

...(more)

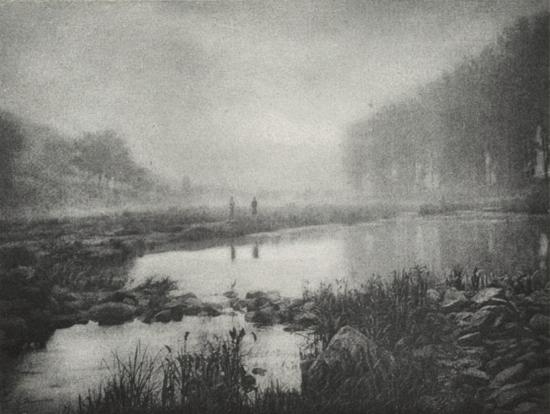

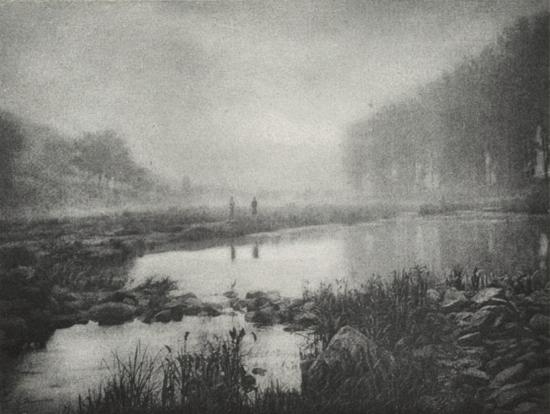

Brume apres la Pluie

1906

Photogravure

Gustave Marissiuax

(1872-1929

via Arsvitaest

_______________________

Truancy

(....)

Truancy. Second innocence. We will regain our innocence. We will forget language. We will un-name the world. We will wander the world in its sacred anonymity. Soon, we’ll know nothing at all.

Truancy. We wander the woods under the white sun. The air is pure. Everything, gathered to the brink. The whole Creation, as a gift to God, glorious before god. And we are as atoms of God. We are particles of the whole – the divine whole. The Vessel has not been shattered. Beauty is everywhere. Goodness is everywhere.

Truancy. Wandering without map. This is the true path, the errant path, the path that wanders through everything, and is the wandering of everything.

Truancy. God walked the world into existence, we’re sure of it. God walked, and the world was born as he walked. And we, walking, will recreate the world. We, as walkers, will re-enact the Creation.

...(more)

Nietzsche And The Burbs

_______________________

Map

Wislawa Szymborska

translated by Clare Cavanagh

(....)

A few trees stand for ancient forests,

you couldn’t lose your way among them.

In the east and west,

above and below the equator --

quiet like pins dropping,

and in every black pinprick

people keep on living.

Mass graves and sudden ruins

are out of the picture.

Nations’ borders are barely visible

as if they wavered -- to be or not.

I like maps, because they lie.

Because they give no access to the vicious truth.

Because great-heartedly, good-naturedly

they spread before me a world

not of this world.

...(more)

_______________________

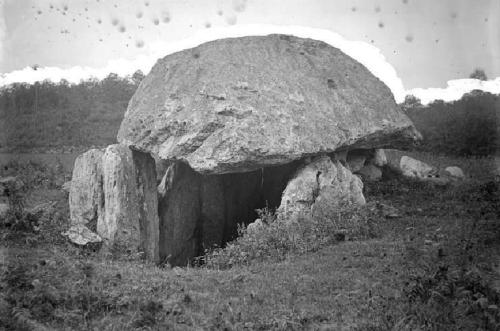

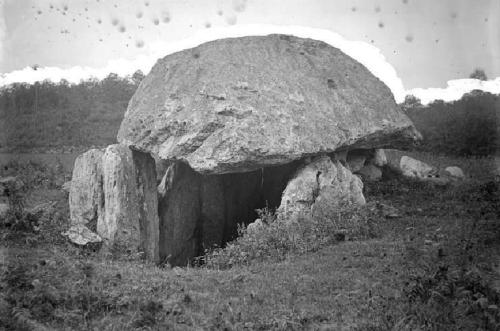

Dolmen

Eugène Trutat

(1840-1910)

_______________________

Nick Admussen Translating Ya Shi

Anti-Birthday Poem

(....)

Of course, what I am saying, it is a kind of memory.

If you are a nurse, please cross it out with a red pen.

(the subject awakens; being collapses like an edifice of sand)

Today, an early morning dripping with cicada song,

my old mother calls, says it's my lunar calendar

birthday, she will celebrate me with steamed pork.

But the isolated god sinks too deeply into his stage drama,

aloneness can be more than the last act...

Even at a play, it's no good to laugh too loud.

Pah, what I mean is: a simpler sentence

has complexity that you cannot control.

When it pierces the vein, will our vanity get crossed out too?

...(more)

Drunken Boat 22

Three Poems by Ya Shi

translated from the Chinese by Nick Admussen

Cha: An Asian Literary Journal

.....................................................

Nick Admussen on translation

New England Review

(....)

NA: With these poems, I drafted the whole series as well as I was able, accumulating a long list of questions from the detailed to the general. Then I went to Sichuan in 2014 and sat down with Ya Shi for a few hours to drink tea and ask all my questions, and the answers shaped the final set of revisions. Meetings like this—this was the third one I’ve done translating Ya Shi poems—are incredibly high pressure for me, even though he’s more than patient with my errors; I’m not just listening for the answers to my questions, but the way in which his responses to my questions indicate whether I’m traveling in the right direction, and have a basic grip on the spirit of the poem. The worst answer an author can give to a translation question is always “why do you care about that?”—to me, such a response means “you do not yet understand this piece. Start again.”

In general I think my translation process requires me to come to a really clear and concrete conclusion about what I’m giving up by putting a poem into English. With Ya Shi, the number one thing that gets lost is his genius for the intercultural. The best example is that when he reads aloud, he chooses to read in rich, musical Sichuan dialect, which is separate from (and superior to, I think) the “standard” dialect that you hear on TV in the PRC. So poems like these have three layers: an inventive adaptation and translation into Chinese of the Italian sonnet form, written in modern Mandarin Chinese, and pronounced in a centuries-old local language. I’m never going to get that same layering effect, that fusion, in an English version, but I need to know it’s there, so that my sensation of its absence can influence the decisions I do get to make.

...(more)

_______________________

Eugène Trutat

_______________________

The Chimera Principle

An Anthropology of Memory and Imagination

Carlo Severi

Translated by Janet Lloyd

Foreword by David Graeber

Full Text - HAU Books

Available in English for the first time, anthropologist Carlo Severi’s The Chimera Principle breaks new theoretical ground for the study of ritual, iconographic technologies, and oral traditions among non-literate peoples. Setting himself against a tradition that has long seen the memory of people “without writing”—which relies on such ephemeral records as ornaments, body painting, and masks—as fundamentally disordered or doomed to failure, he argues strenuously that ritual actions in these societies pragmatically produce religious meaning and that they demonstrate what he calls a “chimeric” imagination.

Deploying philosophical and ethnographic theory, Severi unfolds new approaches to research in the anthropology of ritual and memory, ultimately building a new theory of imagination and an original anthropology of thought. This English-language edition, beautifully translated by Janet Lloyd and complete with a foreword by David Graeber, will spark widespread debate and be heralded as an instant classic for anthropologists, historians, and philosophers.

via Monoskop Log

_______________________

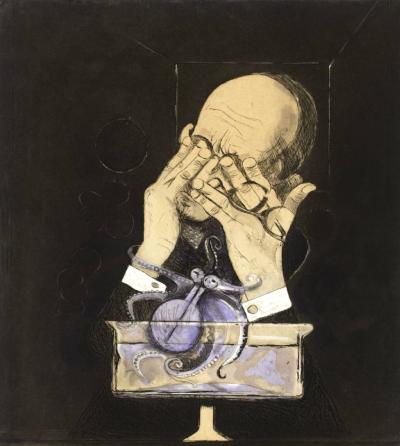

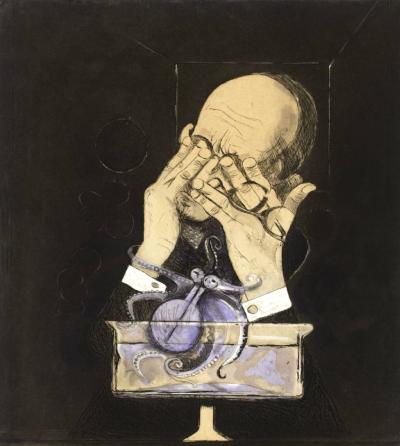

Eugène Trutat

The Octopus

1978-9

Graham Sutherland

b. August 24, 1903

_______________________

Two Poems [pdf]

Anne-Marie Albiach

1937 - 2012

translated by Peter Riley

Shearsman Books

The line

the loss

the account would be blind

the spasms of the oracle structure

in the working of colours

the margin constrains the circle

the evidence on the ground

in a perfect liquidity

where the language

goes back on its word

the heart in the rhythm of denial

the light rejoins weakness

in the former declaration

the facts of the case withdraw to the horizon

a term found wanting

driving accusation of the air full of gestures

dedicated to the embrace

the subject shrinks

sleep bears them into the clearing

In scarlet draperies

they presided on the theme

of an absence

Delineation of desire

Discourse, relapsed murmuring

the representation:

soundless expanse of vocabulary

space, a morning datum

the cold imprints the contours

the witness gives out the theme

facing discredit

this coolness troubling to the eye

The simulacrum opens the wound

heaviness

disavowal, bestiary

the partition

where childhood’s alphabet

watched by a stranger

the numerical parallels their connections

it transpires

of the word

a notch

an attentive duplicity

the fall of a body is lacking

genre adjustment

the random displacement

interval

: the objects

flood onto the table at low tide

_______________________

Bird over Sand

Graham Sutherland

1975

_______________________

The Weatherproof Cape

Thomas Bernhard

Translation by Douglas Robertson

(....)

... as we were climbing the stairs it became clear to me that "you have been seeing this person for two full decades, always the same person, always the same aging individual in the Saggengasse, at around midday in this weatherproof cape, in this quite ordinary but quite definitely worn-out weatherproof cape"; still, as we were climbing the stairs it was not yet clear to me why the weatherproof cape in particular was arousing my attention; suddenly, at close proximity, the weatherproof cape was arousing my undivided attention…but it really is quite an ordinary weatherproof cape, I thought; there are tens of thousands of such weatherproof capes in these mountains, there are tens of thousands of such weatherproof capes; tens of thousands of such weatherproof capes are worn by the Tyrolians…no matter who these people are, no matter what they do, when they come here they wear all these weatherproof capes, some of them gray, some of them green; because they wear all these weatherproof capes, the numerous loden factories in the valleys keep flourishing; ...(more)

via biblioklept

_______________________

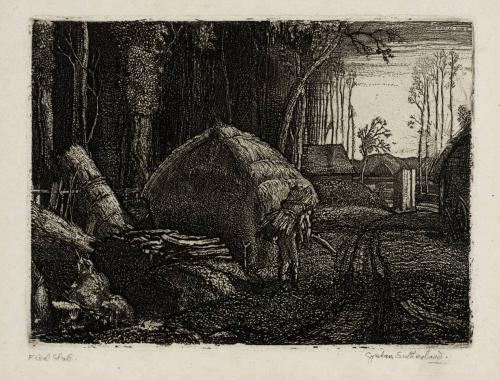

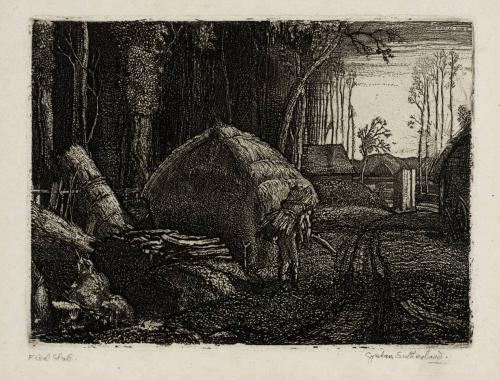

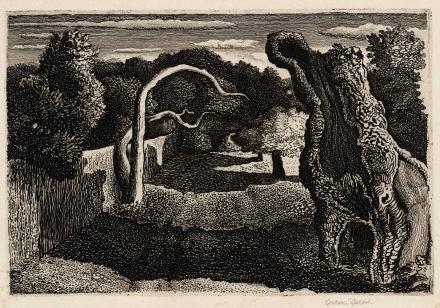

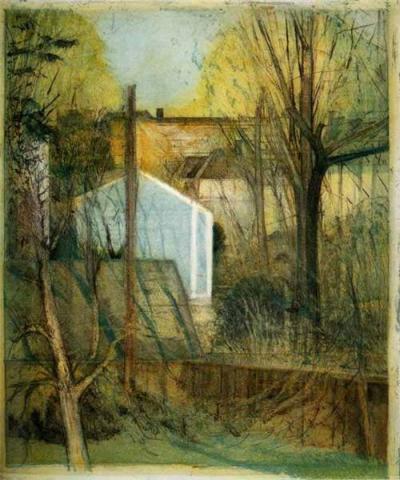

Pecken Wood

Graham Sutherland

1925

_______________________

Kant’s Depression

Eugene Thacker

An excerpt from Starry Speculative Corpse [Horror of Philosophy, vol. 2] (Zero Books, 2015)

(....)

What Kant doesn’t consider is that reason might actually be connected to depression, rather than stand as its opposite. What if depression – reason’s failure to achieve self-mastery – is not the failure of reason but instead the result of reason? What if human reason works “too well,” and brings us to conclusions that are anathema to the existence of human beings? What we would have is a “cold rationalism,” shoring up the anthropocentric conceits of the philosophical endeavor, showing us an anonymous, faceless world impervious to our hopes and desires. And, in spite of Kant’s life-long dedication to philosophy and the Enlightenment project, in several of his writings he allows himself to give voice to this cold rationalism. In his essay on Leibniz’s optimism he questions the rationale of an all-knowing God that is at once beneficent towards humanity but also allows human beings to destroy each other. And in his essay “The End of All Things” Kant not only questions humanity’s dominion over the world, but he also questions our presumption to know that – and if – the world will end at all: “But why do human beings expect an end to the world at all? And if this is conceded to them, why must it be a terrible end?”

...(more)

_______________________

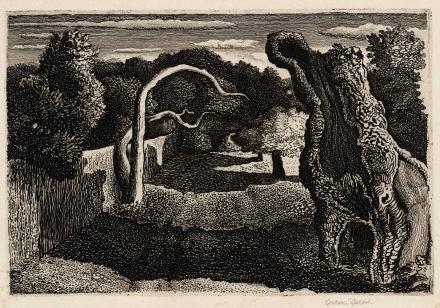

Pastoral

Graham Sutherland

1930

_______________________

March Ample Life

Stephen Rodefer

(November 20, 1940 – August 22, 2015)

Methought I saw my late live-in theory

crossing the fireplace like a train

For the Headless Horseman is bald

in the grave where the hair grows long

And Maud was the androgyne without a club

on the path to Willy Beach

Dear George, the attitude was glued

myopic and is a myopic clue

Dear Lesbia, dyslexia lives

The schizophrenics clap for their sunup

But what is the name of your parrot?

We’ll call it Carriage for Two

Squeak, dear parrot, sing

etcetera, a number of songs etc.

Illusory Town where Mad Tom lives

whose lungs are fucked by God and such

Where signal fires code Aurora

referring to just another ducking

Lake at the edge of sleep

the deathless equestrienne sees

Her namesake singing his hunger

as one spouse signs for another

Sorting out this endless fragment of sky

the curtain has hung on our roots

Cornwall rising

1930

Christopher Wood

d. Aug. 21, 1930

_______________________

Negotiations

Katherine Hedeen interview

jacket2

(....)

For me, translation is a political act. It’s obviously always so, but being highly conscious that I am making a political intervention as a translator is the real difference. This makes itself known in two ways: whom I choose to translate and how I choose to go about it. The vast majority of poets I work with are unknown to English-speaking readers (and I also consider opting for poetry over prose a political choice). They fall outside the idea of what a poet in Spanish “should” sound like.

For American readers there are basically two, Pablo Neruda and the Federico García Lorca, who are widely available in print. And, I don’t think this is a coincidence. They write the way an American audience thinks poets from these regions should write. In my experience, it’s this idea of Spanish being more in tune with sensuality, feeling, the body, earthy almost; not complex, cerebral, intellectual, experimental. It almost mimics the sexist dichotomies between masculine/feminine. The South is sensual; let’s leave the thinking to the North. And I don’t think American readers of poetry question why certain writers are translated; why, for example, there always seem to be so many editions of Neruda’s work with commercial presses (and they keep bringing out more!) and yet the work of the other great Latin American poet of the 20th century, Peruvian César Vallejo, is published with university presses, and much lesser known among general readers.

As a specialist in Hispanic poetry, I want to contest that small canon (and not because I have anything against Neruda or García Lorca; these are amazing poets!), which is built on culturally imperialist notions of what the South is. How I go about all this is also an explicitly political act in my mind. And the first thing I would have to clarify is that it’s not “I”; it’s “we”. On many of these projects I co-translate with the Cuban poet, Víctor Rodríguez Núñez (and we translate from English into Spanish as well). Though I do the bulk of the work from Spanish into English, his help is indispensable. He provides a crucial, insider perspective that undoubtedly makes the translation better.

The truth of the matter is that no intellectual endeavor happens in a vacuum, it is in constant dialogue with other voices, with other traditions, with readers, with editors. And translation is no exception. ...(more)

_______________________

Anemones in a Cornish Window

Christopher Wood

1930

_______________________

Those Obscure Objects of Desire

Andrew Cole on the uses and abuses of object-oriented ontology and speculative realism

artforum

(....)

Ours is a time when schools of interpretation ask us to personify and caricature objects as autonomous and alive—whether they are the objects who “speak” in the new so-called vibrant materialism, or objects who fuss and act up in actor-network theory, or objects with “primitive psyches” in object-oriented ontology. Is this really the way to think at this moment? For Marx, at least, this way of thinking about objects is what keeps capitalism ticking. To adopt such a philosophy, no questions asked, is fantasy—commodity fetishism in academic form. To identify such philosophy as the metaphysics of capitalism is theory, ever attentive to history’s impress on our imaginations, whatever we may dream.

...(more)

_______________________

Cryptosociety: The Dark Economy and Technologies of Freedom

S.C. Hickman

Under the hood of capitalism flows another world, a dark world of economic counter-insurgents. A realm of noirpreneurs who slip the electronic seeds of an anarchic future of pure freedom beyond the capture systems of global governance. A cryptosociety of dark capitalists who live in the shadow markets outside the global eye. This darker world of the bitcoin and blockchain revolution is unleashing the teeth of a global systemic exit, a techno-secessionism that seeks not only to forget capital’s fractured End Game but to undercut its all too human roots in transparency with utter opaqueness and anonymity.

(....)

Yet, as I began researching this post this morning, reading through subjects as various as bitcoin, blockchains, dark markets, dark wallets, etc. I also began to see the trail leading back out of the darkness and into the treadmill of advanced capital itself. Already the signs of larger corporate initiatives are under proof-of-concept to integrate many of the new technologies of these global anarchic techno-commercialists into the mainstream. ...(more)

_______________________

Illegality Regimes: Mapping the Law of Irregular Migration

Edited by Juan M. Amaya-Castro and Bas Schotel

AmeriQuests Vol 11, No 2 (2014)

"Recent years have seen the development of increasingly sophisticated legal and policy approaches to address the phenomenon of irregular immigration. Many states have moved beyond traditional means of law enforcement, such as criminalization, without necessarily abandoning them. In addition, they have begun to employ other areas of law (such as administrative law and labor law) in pursuit of controlling irregular immigration. For example, the verification of legal residence status, by means of ID-controls, has become increasingly necessary in the day to day life of all people: citizens and non-citizens alike. Private citizens, and not government agents, are evolving into the primary enforcers of these policies, as they have been made legally responsible for the control of legal residence status, for example in the case of employment.

These legal and policy instruments have sometimes been justified with reference to economic theories, such as 'attrition through enforcement', the broken window theory, and most recently 'self-deportation', a term that ironically originated in a stand-up sketch performed by two Hispanic comedians in the mid '90s, and has since then been promoted to a major policy proposal in the Romney campaign for the US presidential elections. Among economic scholars, a debate about the (lack of) effectiveness of these policies has been growing the last couple of years. What is still absent, however, is a more rigorous analysis by legal and other social science scholars. This special issue aims to explore the more systemic dimensions of these responses to irregular migration."

Immigration wars

links assembled at Omnivore

_______________________

Herring Fisher’s Goodbye

Christopher Wood

1928

_______________________

The Closing of the Canadian Mind

Stephen Marche

nyt

(....)

The early polls show Mr. Harper trailing, but he’s beaten bad polls before. He has been prime minister for nearly a decade for a reason: He promised a steady and quiet life, undisturbed by painful facts. The Harper years have not been terrible; they’ve just been bland and purposeless. Mr. Harper represents the politics of willful ignorance. It has its attractions.

Whether or not he loses, he will leave Canada more ignorant than he found it. The real question for the coming election is a simple but grand one: Do Canadians like their country like that?

...(more)

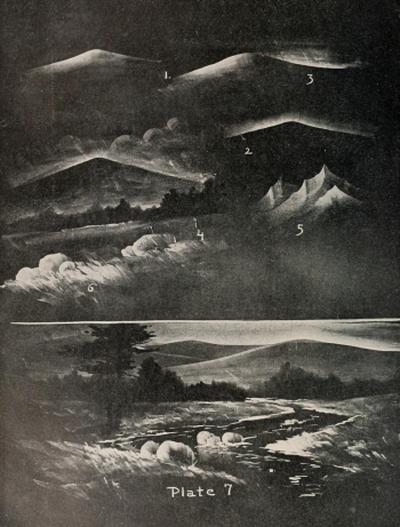

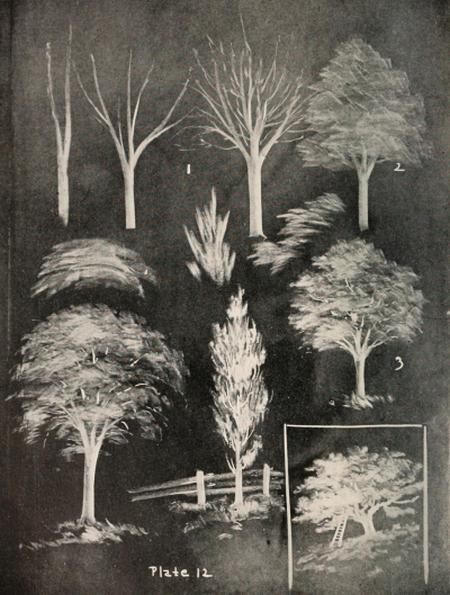

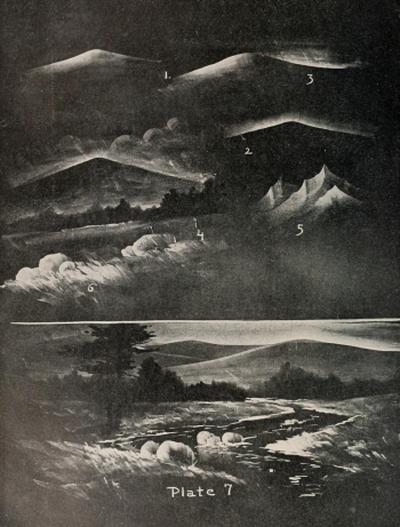

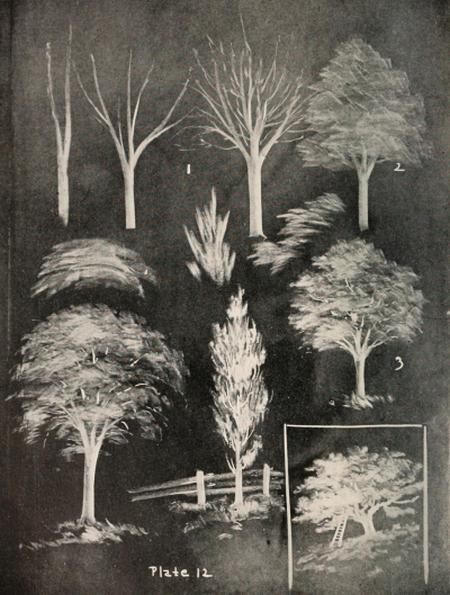

Blackboard Sketching

Frederick Whitney

(1909)

_______________________

from a wearing of light

Felino A. Soriano

otoliths

Spectral

A breath stretched its skeletal sound.

Its corporeal state, altered, renaming.

Man does this, developing ideology of selective façade.

Something becomes altered following the

hand’s evil speculation.

Language

designs beyond what

predetermined

miracle

delves into gradating an eventual improvisation

of sound and mobile dexterity.

I’ve seen dragonflies examine blur as thesis confirmation.

The good eye researches factual alphabets confirming

duality of already splayed and unorganized plurals. Tiredness

of static smallness portends a trend furthering the baseline

behavior of why aloneness leads to remembering.

...(more)

Of the poetry this jazz portends Felino A. Soriano: poet of cooccurrences

_______________________

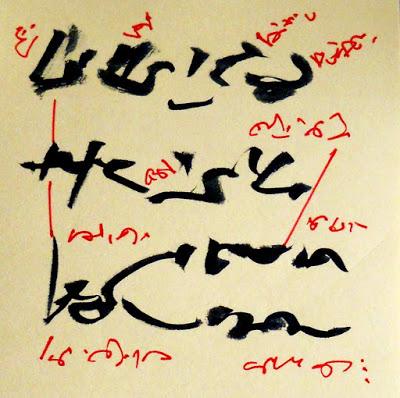

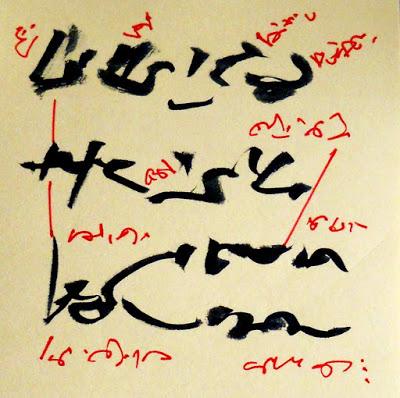

some Asemics & Langrids

Marco Giovenale otoliths issue thirty-eight

southern winter, 2015

_______________________

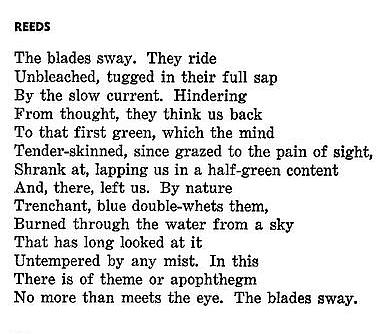

We Dance On: On Reading Roethke

Nathan Knapp

the millions

(....)

It’s as if the entire critical apparatus used to deal with a writer whose work grapples explicitly, aggressively with the Eternal has disappeared. Aside from Annie Dillard, whose work (both creative and critical) certainly soars with a transcendentalist, eternity-haunted uplift, there have been few recent writers willing to wade out into the mouth of the river and seek the God-who-dwells-in-the-depths.

What’s a contemporary critic to do with a writer who pleads, Hopkins-like, near the end of his final book of poems:

Lord, hear me out, and hear me out this day: / From me to Thee’s a long and terrible way?

(....)

There are two kinds of reading. The first involves sucking up a writer’s body of work vacuum-style, like a construction worker eats his lunch, quickly and efficiently. This style of reading is not without its merits, being that there is more out there to read than one could ever hope to finish, and to have a solid breadth of reading is essential for any writer. Yet the dark side of this kind of reading is that while one may scoop up the general concepts, subject matter, and style of any particular author, as one blazes through their collected poems, one runs the risk of missing the real depth of the author in question (if there is any). The second kind of reading is exactly the opposite of the first. It’s the kind of reading proceeds solely — and, typically, slowly — for nourishment’s sake, and it’s the kind of reading I gave to Roethke’s final book of poems, The Far Field. For months I went nowhere without my library copy of it. When I finally, reluctantly, had to turn the copy back in I bought my own. I read and reread the massive, expansive poems of the “North American Sequence,” and the apocalyptic, God-beyond-God obsessed “Sequence, Sometimes Metaphysical,” sometimes lingering with those poems the way one lingers in bed on a Saturday morning, sometimes shaking in the dark, repeating:

The right thing happens to the happy man.

...(more)

_______________________

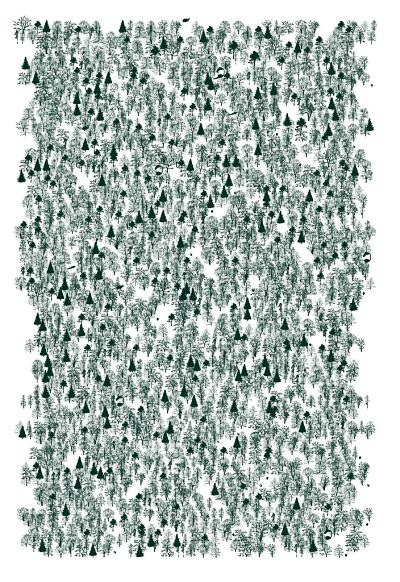

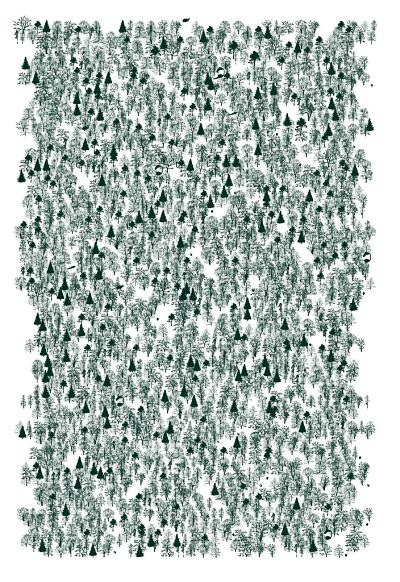

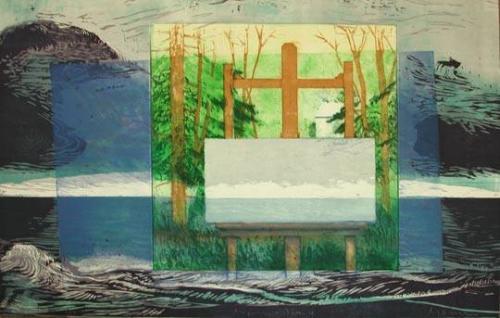

Page 26 from About Trees,

2015. Tacita Dean’s essay “Michael Hamburger” translated into Trees.

Translating Borges into Trees: An Interview with Book Artist Katie Holten

asymptote

(....)

Katie Holten: About Trees is a book about trees written in trees. It’s a collection of texts about trees, about the notion of trees, and a constellation of tangential tree-related things. Everything is translated into Trees, a new typeface that I made especially for the project. At the core of the book is a Tree Alphabet with trees replacing each of the 26 letters of the standard English/Latin alphabet. These characters were transformed into a font, the typeface called Trees.

(....)

I think of the book as an archive of human knowledge filtered through branches of thought. It traces a shift in consciousness from anthropocentric thinking to a contemporary realization that our way of life has probably created a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. The book maps the move from Darwin’s “I think,” written beside his sketch of the tree-of-life illustrating human consciousness as the highest step on the evolutionary tree, to Eduardo Kohn’s “How Forests Think,” an anthropology beyond the human. The writings of Bruno Latour and Timothy Morton have been useful for me to understand my own work and current thinking around object-oriented ontology, which puts things at the center of the study of existence.

...(more)

_______________________

Blackboard Sketching

_______________________

Why I Hear Music When I Read The Dark Mountain Manifesto

Mike Edwards

Perhaps it is time for us to open our ears and to hear the world anew. Every issue our politicians discuss; every campaign our activists wage; every environmental catastrophe we bear witness to; every historical event that has shaped our world; every relationship; every love affair; every birth; every death; everything on this little planet, since it came into existence 4.54 billion years ago, has either created a sound or has a sound associated with it. Sound is important and we ignore it at our peril.

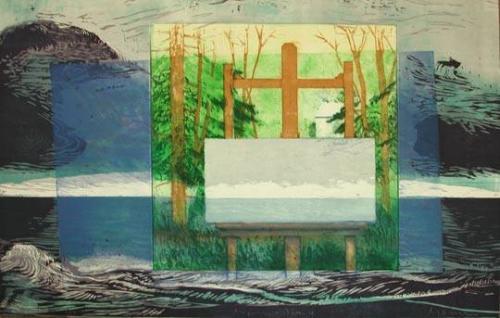

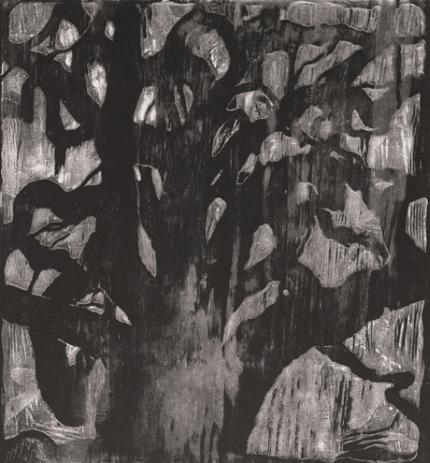

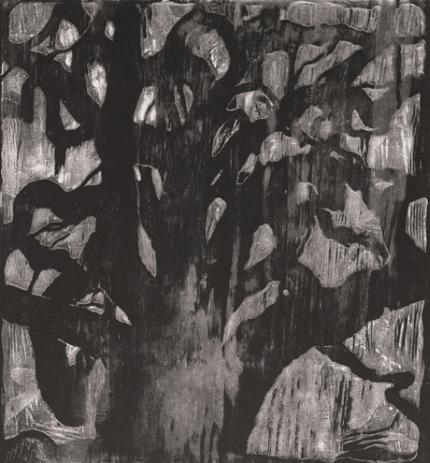

Memory and Distance

1992

Etching and woodcut

Michael Mazur

1935 - 2009

_______________________

from War Variations

Amelia Rosselli

1930 - 1996

Translated from the Italian by Lucia Re and Paul Vangelisti

(....)

the god who burns everything between pickup truck and pity, the

grand salami the grand universe oh you are one being with

such a keen point that I change color solely

considering you but the man with his variegated multicolored pains

(o grand variety of the whole!) traps

me in a relationship so increasing and so hard to bear so

extraordinarily guilty, that I delay any customary custom

because my customary senses have seen too much of the world spread

like a lot of flour, between mountains, beaches, trees, peaches, every

kind of

saliva at your feet, and you who understand nothing and cannot (and

cannot ever) connect the variegated vicissitudes in a

single going in a single one of god’s plagues because

he hides behind the shadows.

and what did that crowd want from my senses other than

my scorched defeat, or I who begged

to play with the gods and stumbled

like a poor whore up and down

the dark corridor— oh! wash my feet, take

the fierce accusations from my

bent head, bend

your accusations and undo all

my cowardice!: it wasn’t my wish to break the delicate layer of ice

not my wish to break the mounting battle, no, I swear, it wasn’t my

wish to break through your laughable

laughter!— but the hail has other reasons than

serving and the wet eastern wind of

evening does not dream of standing

watch by my

disenchanted lion sobs: no longer will I run

after every passage of beauty,— beauty is defeated, never again

at attention will I snuff out that fire now glimmering like

an old tree trunk

in which hollow swallows make nonsensical nests, child’s play,

unreckoning misery, unreckoning misery of sympathy.

...(more)

_______________________

On Translating Amelia Rosselli

Jennifer Scappettone

(....)

Certainly discovering the poetry of Amelia Rosselli poetry gave me a new purchase on the languages present in my childhood and a new understanding of the hybridity of my Italian background. Even though her background was nothing like mine.

I learned through Rosselli how tradition gets carried along, gets distressed, tattered, and reemerges in pieces.

(....)

The way in which Rosselli addresses history in her poems is much more indirect than people might imagine at first. In other words it is not the writing of witness. You almost never find an autobiographical trace except in a fragment that is quoted all the time. “Nata a Parigi travagliata nell’epopea della nostra generazione fallace…” (Born in Paris Labored in the epic of our fallacious / generation…). Instead history is kaleidoscopically refracted in her works; it is processed in the everyday. There is never a meta-historical analysis, never the arrogance of history with a capital H —history already understood— but rather history as processed almost in a corporeal way, as encountered in the low things. She was so attached to the low things.

AC History confronted through language…

JS Yes. You can read history in the fractured logic of her work. In the syntax that is so tortured, in the neologisms… that is where you find history. The English language meeting the French language meeting the Italian language: that is the history she addresses. And of course there is literary history, from Dante, the Dolce Stil Novo, from the metaphysical poets… It’s an experimental approach to history, never a historical narration.

...(more)

Locomotrix

Selected Poetry and Prose of Amelia Rosselli, a Bilingual Edition

Edited and Translated by Jennifer Scappettone university of chicago press_______________________

P.Z. 11'

Alfred Wallis

b. August 18, 1855

_______________________

Rising Speech: Are We Still Worthy of Poetry? [pdf]

Maurice Blanchot

Translated by Wanyoung Kim

(....)

It is here that it translates, "this madness," that it comes back to us as the impossible need. Translating especially the untranslatable: when the text does not only carry an autonomous meaning which alone would be important, but when the sound, the image, the voice (phonological) and especially the principality of rhythm are predominant compared to the meaning or making good sense, so that the meaning is always in action, in formation, or "the nascent state" cannot be dissociated by what by itself is not stored in the semantics. And this, this is the poem. Certainly, no translator, no translation will not pass it, intact, from one language to another, and will not permit it to be read or heard as if it were transparent. And I would add: happily. The poem in its original language, is always already different from the language, whether it restores or establishes it; and it is this difference, the otherness, where the translator grabbed it or where it is grabbed, modifying in its turn its own language, making it dangerously moving, removing its identity and transparency to the "common sense," as Valéry says.

Opacity? Opacity of sense? Opacity as meaning? Neither one nor the other. The opacity has multiple layers of language through which they walk and form what eventually - in infinity - mean: strata that simultaneously flicker or darken by the significance, moments by themselves neglected in common parlance, transforming then just to make comprehensible another another form of agreement, the unlimited agreement that breaks the ordinary trade. Hence, perhaps, the poetic loneliness (has anyone been there to understand it? It is infinitely enough to hear it?); hence also the poetic fraternity ("sovereign conversation"), since which, by the poem, we are called to the urgency of interminable ration where the "I" has always faded away to the other, and where speech, writing, and sign collapse without constantly pursuing anticipation that dissolves them and mysteriously remains there by a frightening dispersion. (....)

_______________________

From Serie Ospedaliera

Amelia Rosselli

Translated by Diana Thow

jubilat

*

You don't remember my golden shores, as if I think

obnoxious you lean out the balcony, without seeing

anything beyond your mind, which struggles to write

beautiful things. Otherwise with every gust of wind

you'd be there, at the hanging, enriched by your

richly metaphored foundations.

And then you'll see the blue sky, coloring itself with

your spite which leans out too, assisting you,

attending you as you embroider other small artifices,

or shipwreck, with your muse. And how sweet

to shipwreck in this wild sleep, and how sweet to not think

beyond the mania of seeing, touching, feeling

smelling your full repose.

Then you touch the foot, you spill it into the olifactory, you

take it by the hand and approach it, the sign on the segment

that pops up between the rocks, which covering you the houses

become fortresses, for your small town, that amuses itself

almost innocently, you raised the bull so much.

And you push it, the foot, to an open door, and you greet

the ladies (to the man you don't offer your hand). And then

you descend again, through naked piazzas

through no-man's land, alleys swollen with the

rain, which you don't see so much now that it's dry the sky

unsheathed you descend again, the hour accompanies you,

it's a mix of fate and your habit of making

every sob into one more life.

*

...(more)

via The Page

Poems By Amelia Rosselli And A Conversation With Rosselli Translator Diana Thow

_______________________

Women in the Avant-Garde

Rosselli & revolutions of content

Sandra Simonds & Catherine Wagner

lana turner

(....)

A native speaker of several languages, Rosselli committed herself to writing mostly in her father’s tongue while working against its formal and cognitive limitations. Some of her poems critique the interdependence of aesthetic and capitalist formations, and in this they resemble the writing of Eduardo Sanguineti and his fellows in the neo-avant-garde, though Rosselli and other women remained “a tiny and marginalized minority” in the movement (Re). Suspicious of avant-gardism and its tendency to reify hierarchical and exclusionary practices in its efforts to resist, even more suspicious of mainstream confessionalism’s “self-exceptionalizing” gestures, Rosselli wrote a radically anti-egoistic poetry, “choral” and macaronic, that integrates rigorous formal invention with a irreverent and strategic melding of her several native languages in order to “address afflictions shared” (Scappettone).

...(more)

Poems from Locomotrix: Selected Poetry and Prose of Amelia Rosselli sibia

Nomadic Translations: (G)hosting in Amelia Rosselli’s Variazioni belliche

Aarón Lacayo _______________________

Michael Mazur

_______________________

"But how many daydreams we should have to analyze under the simple heading of Doors. For the door is an entire cosmos of the Half-open. In fact, it is one of its primal images, the very origin of a daydream that accumulates desires and temptations: the temptation to open up the ultimate depths of being, and the desire to conquer all reticent beings. The door schematizes two strong possibilities, which sharply classify two types of daydream. At times, it is closed, bolted, padlocked. At others, it is open, that is to say, wide open.

And what of all the doors of mere curiosity, that have tempted being for nothing, for emptiness, for an unknown that is not even imagined? Is there one of us who hasn't in his memories a Bluebeard chamber that should not have been opened, even halfway? Or which is the same thing for a philosophy that believes in the primacy of the imagination, that should not even have been imagined open, or capable of opening half-way? How concrete everything becomes in the world of the spirit when an object, a mere door, can give images of hesitation, temptation, desire, security, welcome and respect. If one were to give an account of all the doors one has closed and opened, of all the doors one would like to reopen, one would have to tell the story of one's entire life. But is he who opens a door and he who closes it the same being?"

-

- Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, translated by Maria Jolos

reposted from Whiskey River

_______________________

Michael Mazur

Ridgeway: Wayland’s Smithy

Fay Godwin

1931 - 2005

_______________________

Four Poems

Mark Irwin

conjunctiona

A Tale of Hats

Because the bodies were so filled with bodies they sprouted heads

then needed to sleep and when their heads woke

they felt naked so they found hats. The first hats

were made of tree bark and straw so the new heads

could sleep, though some say the hats grew out of sleep

as houses grow out of earth, while others

say that the hats are tunnels to somewhere else, and yet

some swear that each hat buries the body, and if one

wears a hat to sleep, the dead come back, especially those

loved, and gather there, where sorrow

becomes joy in that small tent of shadow

where they come to breathe.

...(more)

_______________________

Zig-Zag Groynes

Fay Godwin

_______________________

Nine poems from 'Nine'

Anne Tardos

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

Because Sigmund Said So

Nine 2

Sleep being slept, a bird has something to say.

Reality flip flop artistic failure extremely hard to explain.

Foggy zendo vigilance gendergap understanding the desire to live.

Levitating underbelly slime, dengue fever ankle deep, vilification zigzag.

I love you too dear—count your chickens carefully.

Echo chamber plant life, cellular reality, yellow rent abatement.

Quiet knucklehead comradery a thousand hopes subject to change.

Infinity appears in repeated mirror images perceived as reflection.

Zealous devotion to waxwork sex, because Sigmund said so.

...(more)

_______________________

Machiavelli, Comedian

Christopher S. Celenza looks at perhaps the best known of these plays, Mandragola, and explores what it can teach us about the man and his world.

public domain review

(....)

“Comedian”, admittedly, isn’t the first word you associate with Machiavelli. And “funny” is not a word normally applied to Lucretius. And yet, through some strange alchemy of time, circumstance, and the rhythms of Renaissance life, those seemingly discordant elements came together in a remarkable way. You could argue that Machiavelli’s entire worldview was comic, but comic in a peculiar way: ironic, wry, a little melancholy, punctuated by an earthy vulgarity that, these days, would get him thrown off a university faculty in a minute. More than this, the central premises of what was funny have changed so significantly that it invites us to think about how comedy works and when it’s time to say that a comedy, however venerable, just isn’t funny anymore.

(....)

In the end the value of Machiavelli’s comedies resides not so much in their original purpose – to make people laugh – but in what they can teach us about him and his world. It is striking that despite the manifold differences between Machiavelli’s surroundings and ours, there are such similarities between his environment and that of ancient Rome. A comedy like Terence’s Eunuch not only spoke to Machiavelli and his cohort, it also served as a source of imitative inspiration. That fact reminds us that, despite the many times we can find traces of ourselves in Machiavelli’s work – of the Realpolitik that he helped create, say, or the tendency to observe human motivation shorn of traditional morality – he was also living in a world gone by.

It was a place where it was assumed that women simply were not part of the conversation, where the post-enlightenment notion of universal human rights (imperfectly realized as those have been) was only a dim adumbration, and where a lot of what might have made one laugh was differently situated. None of this is to praise or blame Machiavelli or his ancient Roman sources for what seem to us today like failings. Comedy serves as a kind of retrospective indicator of blind spots. It is our fate not to know what posterity will make of our own age’s comic strivings. But wouldn’t one like to be a fly on the wall in five hundred years?

...(more)

_______________________

Clump In Hollow, Summerhouse Hill

Fay Godwin

_______________________

The Eight Principles Of Uncivilisation

synthetic zero

‘We must unhumanise our views a little, and become confident

As the rock and ocean that we were made from.’

We live in a time of social, economic and ecological unravelling. All around us are signs that our whole way of living is already passing into history. We will face this reality honestly and learn how to live with it.

We reject the faith which holds that the converging crises of our times can be reduced to a set of ‘problems’ in need of technological or political ‘solutions’.

We believe that the roots of these crises lie in the stories we have been telling ourselves. We intend to challenge the stories which underpin our civilisation: the myth of progress, the myth of human centrality, and the myth of our separation from ‘nature’. These myths are more dangerous for the fact that we have forgotten they are myths.

We will reassert the role of storytelling as more than mere entertainment. It is through stories that we weave reality.

Humans are not the point and purpose of the planet. Our art will begin with the attempt to step outside the human bubble. By careful attention, we will reengage with the non-human world.

We will celebrate writing and art which is grounded in a sense of place and of time. Our literature has been dominated for too long by those who inhabit the cosmopolitan citadels.

We will not lose ourselves in the elaboration of theories or ideologies. Our words will be elemental. We write with dirt under our fingernails.

The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world full stop. Together, we will find the hope beyond hope, the paths which lead to the unknown world ahead of us.

Uncivilisation

The Dark Mountain Manifesto

The Dark Mouontain Blog

|