|

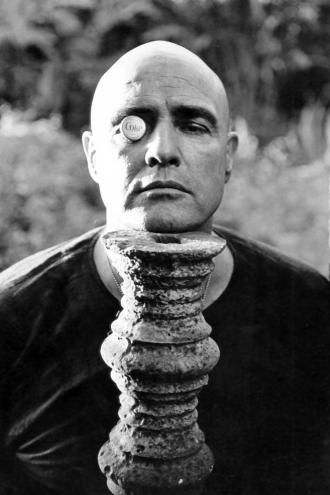

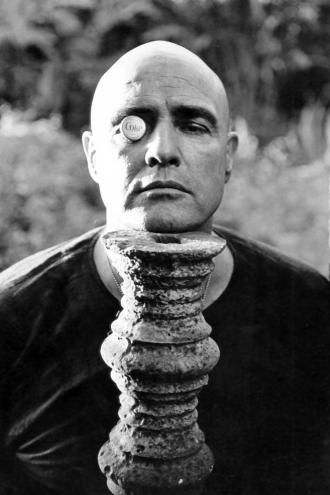

Izmir, Turkey

1965

Mary Ellen Mark

March 20, 1940 – May 25, 2015 Photographers, Writers and Friends Remember Mary Ellen Mark

_______________________

Poems by Boris Vian

Translated by Jeremy Page

asymptote translation tuesday

Red

To Edith

Mothers bleed when you’re made

And hold you all your life

By a flayed gash of flesh

You’re brought up in cages

You live by chewing morsels

Of bleeding, torn off breasts

Which you hook onto your cradle

You have blood all over you.

And as you don’t enjoy the sight of this

You make the blood of others flow

One day, there won’t be any left

And you’ll be free.

...(more)

_______________________

More Disney than Disney World: Semiotics as Theoretical Make-believe (II)

Scott Bakker

Three Pound Brain

(....)

The difficulty with qualifying a stage as a biological phenomenon, however, is that I included intentional artifacts such as narratives, paintings, and amusement parks as examples of stages above. The problem with this is that no one knows how to reconcile the biological with the intentional, how to fit meaning into the machinery of life.

And yet, as easy as it is to anthropomorphize the cuckoo’s ‘treachery’ or the trapdoor spider’s ‘cunning’—to infuse our biological examples with meaning—it seems equally easy to ‘zombify’ narrative or painting or Disney World. Hearing the Iliad, for instance, is a prodigious example of staging, insofar as it involves the serial cognition of alternate environments via auditory cues embedded in an actual, but largely neglected, environment. One can easily look at the famed cave paintings of Chauvet, say, as a manipulation of visual cues that automatically triggers the cognition of absent things, in this case, horses:

But if narrative and painting are stages so far as ‘cognizing alternate environments’ goes, the differences between things like the Iliad or Chauvet and things like trapdoor spiders and cuckoos are nothing less than astonishing. For one, the narrative and pictorial cuing of alternative environments is only partial; the ‘alternate environment’ is entertained as opposed to experienced. For another, the staging involved in the former is communicative, whereas the staging involved in the latter is not. Narratives and paintings mean things, they possess ‘symbolic significance,’ or ‘representational content,’ whereas the predatory and parasitic stages you find in the natural world do not. And since meaning resists biological explanation, this strongly suggests that communicative staging resists biological explanation.

But let’s press on, daring theorists that we are, and see how far our ‘zombie stage’ can take us. The fact is, the ‘manipulation space’ intrinsic to bounded cognition affords opportunities as well as threats. In the case of Chauvet, for instance, you can almost feel the wonder of those first artists discovering the relations between technique and visual effect, ways to trick the eye into seeing what was not there there. Various patterns of visual information cue cognitive machinery adapted to solve environments absent those environments. Flat surfaces become windows.

...(more)

More Disney than Disney World: Semiotics as Theoretical Make-believe (I)Scott Bakker

_______________________

Mary Ellen Mark

_______________________

Unthinking Modernity:

Historical-Sociological, Epistemologicaland Logical Pathways

Gennaro Ascione

Abstract

Modernity remains the privileged theoretical frame and narrative for long term processes at the global scale, notwithstanding the heterogeneously contested definition of its spatiotemporal coordinates, the irreconcilability of contradictions inherent to its alleged emancipatory power and the accusations of complicity with Eurocentrism. This article explores some logical, epistemological and historical-sociological contradictions inherent in the effort to produce non-euorcentric categories of social and historical analysis, and explains why such an effort is doomed to failure if modernity keeps on being accepted as the epistemic territory within which such an effort is located. Eurocentrism is thus defined as palingenetic, to the extent it constantly shifts its contextual meaning while reformulating European centrality in different and ever-changing modalities; such properties of Eurocentrism as a paradigm are conceptualized in terms of its ability to operate by means of consequential isomorphism. Evidences from recent debates in history of scientific modernity are considered, in order to articulate analytical tensions between connected histories and dialogical civilizational narratives of East and West relation at the global scale. The impossibility to explain the ‘why’ of modernity according to a coherent ‘how’ of modernity without falling into Eurocentric structures of thinking is assessed. Finally,theoretical project of “unthinking modernity” is introduced as a possible way to reframe the problem of Eurocentric limits in historical and social sciences.

_______________________

Mary Ellen Mark

_______________________

A Plea for Culinary Modernism

The obsession with eating natural and artisanal is ahistorical. We should demand more high-quality industrial food.

Rachel Laudan

jacobin

(....)

As an historian I cannot accept the account of the past implied by Culinary Luddism, a past sharply divided between good and bad, between the sunny rural days of yore and the gray industrial present. My enthusiasm for Luddite kitchen wisdom does not carry over to their history, any more than my response to a stirring political speech inclines me to accept the orator as scholar.

The Luddites’ fable of disaster, of a fall from grace, smacks more of wishful thinking than of digging through archives. It gains credence not from scholarship but from evocative dichotomies: fresh and natural versus processed and preserved; local versus global; slow versus fast: artisanal and traditional versus urban and industrial; healthful versus contaminated and fatty. History shows, I believe, that the Luddites have things back to front.

That food should be fresh and natural has become an article of faith. It comes as something of a shock to realize that this is a latter-day creed. For our ancestors, natural was something quite nasty. Natural often tasted bad.

(....)

For all, Culinary Modernism had provided what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, populations grew taller, stronger, had fewer diseases, and lived longer. Men had choices other than hard agricultural labor, women other than kneeling at the metate five hours a day.

So the sunlit past of the Culinary Luddites never existed. So their ethos is based not on history but on a fairy tale. So what? Perhaps we now need this culinary philosophy. Certainly no one would deny that an industrialized food supply has its own problems, problems we hear about every day. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, local, artisanal, slow food. Why not create a historical myth to further that end? The past is over and gone. Does it matter if the history is not quite right?

It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that the foods of Culinary Modernism — egalitarian, available more or less equally to all, without demanding the disproportionate amount of the resources of time or money that traditional foodstuffs did — allow unparalleled choices not just of diet but of what to do with our lives.

...(more)

_______________________

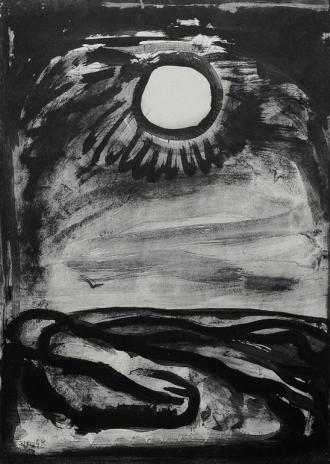

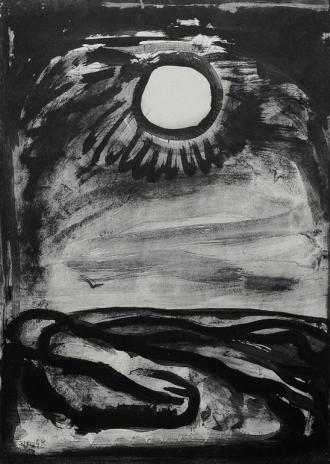

Chantez Matines, le jour renait

Georges Rouault

b. May 27, 1871

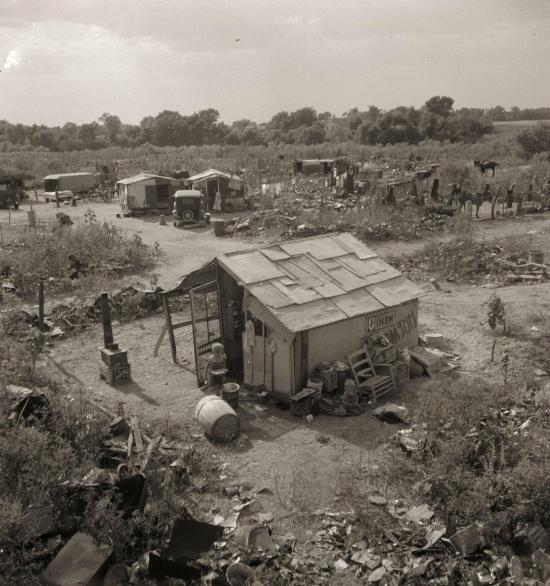

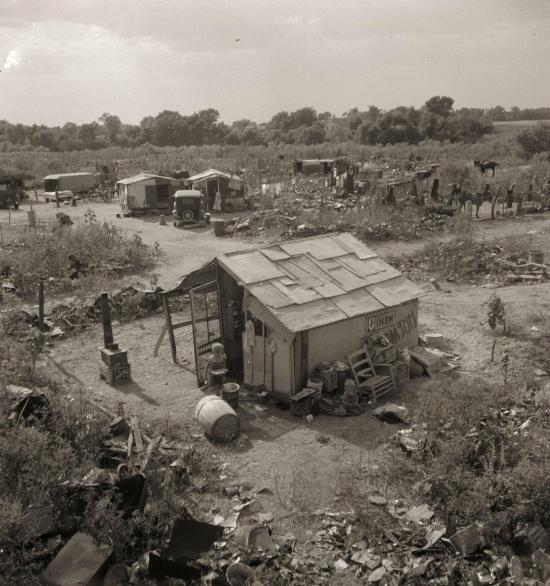

Dorothea Lange

b. May 26, 1895

_______________________

When the viewer vanishes

Leena Krohn

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Books from Finland

(....)

Civilisations are not based on the intellect and rational thought to nearly the extent we wish to believe. In fact, the opposite is the case. The human world is built up of strange connections, logically impossible constructions: conjoined facts and fancies, double helices of the concrete and the illusory.

I have sometimes used this idea to illustrate the concept of ‘tribar’. (This was originally the name given by the physicist Roger Penrose for a kind of triangle which can be drawn, although it cannot be constructed in three-dimensional reality.) For me, this ambivalence is one of the most important observations about the world: that our reality is never a matter of either–or, but always one of both–and.

Money is an excellent example of such a tribar. In Tribar (1993) I wrote: ‘The new electronic economy has made money into an increasingly spectral phenomenon. Exchange rates and share prices are no more than digital states that jump in time to imagined futures. But how concretely these poltergeists are able to rattle our lives.’

Decades have passed, and money has increasingly little to do with the real economy. Money, which does not really exist, turns the wheels of the global economy. Money borrowed from the future has already been spent. A temporary currency supported forcibly by means of immense sacrifice, the euro, has begun to be described with the absurd concept of ‘irreversible’.

In my youth I wasn’t in the least interested in financial matters or economic systems and I could not even imagine that such distant and incomprehensible things could ever influence my own work. I have subsequently been forced to abandon this ignorance, as I have so many others. Writers are not bystanders; they live as prisoners of the same delirious institutions as other citizens. They, too, live in the House of Usher.

...(more)

_______________________

Dorothea Lange

_______________________

Blame not my lute

Thomas Wyatt

Blame not my lute for he must sownd

Of thes or that as liketh me.

For lake of wytt the lutte is bownd

To gyve suche tunes as plesithe me.

5Tho my songes be sume what strange

And spekes such words as toche they change,

Blame not my lutte.

My lutte, alas, doth not ofend

Tho that perfors he must agre

To sownd such teunes as I entend

To sing to them that hereth me;

Then tho my songes be some what plain

And tocheth some that vse to fayn,

Blame not my lutte.

My lute and strynges may not deny

But as I strike they must obay;

Brake not them than soo wrongfully,

But wryeke thy selffe some wyser way;

And tho the songes whiche I endight

To qwytt thy chainge with Rightfull spight,

Blame not my lute.

...(more)

.....................................................

First reading of Basil Bunting's performance of Thomas Wyatt's 'Blame not my lute'

Andrea Brady

jacket2

Basil Bunting’s voice is so familiar – the Briggflatts intonation, half-Santa Claus, half-priest, that hieratic tone which makes Ezra Pound reach for his kettle drum; those luxurious rolling rs. He plays wonderfully with the bathos of the sounding of the word “lute,” not pressing too hard on it, but giving it a solid /oo/ rather than /yu/ sound. His modern Northumbrian accent is not Wyatt’s Kentish early modern one, of course, and I can also hear Bunting’s age in his voice, where I think of Wyatt’s poem as that of a much younger man. Bunting sounds like he is reading Wyatt’s poem off a paper, you can almost hear the pauses as he squints – e.g. after the fourth line; so that speaks to the transition from oral cultures to print ones, a transition which interested Bunting too. And to have a performance text he also had to settle on a version of the poem, which means glossing over the worries around manuscript variants which are particularly acute in the case of the Wyatt canon.

(....)

Knowing this poem well, I’m struck by the contrast between the delivery, which is lyrical and pleasant, and my own preconceptions (or my tendentious reading of the poem for my current project on Poetry and Bondage). I fasten on the vocabulary of being “bownde” and commanded: “perforus he must agre”; “as I strike they must obay,” a violence which enforces submission, rather than a delicacy of “touch”; wreaking, rightful spite (a tautology which justifies and then immediately undermines itself). To me this is a poem not of whimsical or flirtatious banter but of violent competition, bridled by social decorum — or at least arriving at it through the often sadistic pleasures and complaints of Wyatt’s poetry makes me read it that way.

...(more)

Basil Bunting's performance of Thomas Wyatt's 'Blame not my lute' [mp3]

_______________________

Hooverville

Elm Grove, Oklahoma

Dorothea Lange

1936

_______________________

On the Afternoon in the Aftermath of the Root Canal up in Lewiston

Robert Gibbons

The root of the matter is crucial.

Even in as simple thing as a tooth.

Or that of the World Tree, roots reaching

deep in the realm of the underground. Heart

of the matter of language with its dirt, & clean

stones. Cistern of language I felt today, when down

by the waterfront the wind in the waves was more like weave

of a text, knowing that underneath ocean life teemed: cormorant,

seal, crab, & fish, right down to the floor of seaweed. Stood a while

taking it all in, reading the vast World, when the tanker, Leopard Moon

out of Singapore cast added daytime light on pages turning stars in the harbor.

More poems by Robert Gibbons at Enduring Gloucester

photo - mw

_______________________

Journey into the Interior

Theodore Roethke

Born: May 25, 1908

In the long journey out of the self,

There are many detours, washed-out interrupted raw places

Where the shale slides dangerously

And the back wheels hang almost over the edge

At the sudden veering, the moment of turning.

Better to hug close, wary of rubble and falling stones.

The arroyo cracking the road, the wind-bitten buttes, the canyons,

Creeks swollen in midsummer from the flash-flood roaring into the narrow valley.

Reeds beaten flat by wind and rain,

Grey from the long winter, burnt at the base in late summer.

-- Or the path narrowing,

Winding upward toward the stream with its sharp stones,

The upland of alder and birchtrees,

Through the swamp alive with quicksand,

The way blocked at last by a fallen fir-tree,

The thickets darkening,

The ravines ugly.

_______________________

fishing on the Arno

Ronald Reis

_______________________

parrhesia :: a journal of critical philosophy issue 2

Anarchist All The Way Down: [pdf]

Walter Benjamin’s Subversion Of Authority In Text, Thought And Action

James R. Martel

In this paper, I will be describing how Walter Benjamin is “anarchist all the way down.” By this, I mean that Benjamin is not only an anarchist by political temperament but in just about every other way possible as well. Although Benjamin tended to refer to himself as a communist, as I will try to show, his version of communism is anarchist through and through. In this paper I am going to focus on three ways in which Benjamin is anarchist: theologically, politically and linguistically. My argument throughout will be that Benjamin offers us a profoundly anarchist approach (even an anarchist method, as oxymoronic as that may sound) which encompasses not only what he says but how he says it. Theologically, Benjamin offers us a vision of God whose essential function in terrestrial matters is to destroy false notions that human beings project onto the divine. Rather than serving as a basis for the false models of political and legal authority that leads to what he calls “mythic violence,” for Benjamin God manifests the failure of these projections to be true, leaving us radically and utterly on our own. Politically speaking, such a view enables us to act in ways that are not predetermined by myths, either of the divine or secular variety. When we fight the sense of an inevitable fate that comes along with mythic violence, for Benjamin, we become aware of the ways that human beings are capable of making their own decisions both as individuals and as members of a community. As I will argue further, this is a profoundly anarchist insight insofar as it both allows and invites the politicization of vast spheres of human life that are normally considered to be already, and invariably, determined. Finally, in terms of his linguistic practices, Benjamin’s own writings perpetuate the anarchism he describes and promotes in his texts. As a writer, Benjamin is concerned above all with suspending and subverting figures of authority. This includes his own authority in his texts. For Benjamin, if an author speaks of decentering authority but retains a central authority as a writer in order to do so, he or she undercuts the inherent anarchism of that message. Benjamin avoids this problem by turning to techniques such as allegory and montage in order to make his own textual authority radically unavailable. In this way he repeats for the reader the position of the subject of divine acts of violence. As with that subject, Benjamin’s reader too is left to her own devices, shorn of any hope for rescue or redemption by any authority figure. In this way, theologically, politically and linguistically, Benjamin offers something of a seamless web of anarchistic practices; hence he is anarchist all the way down.

_______________________

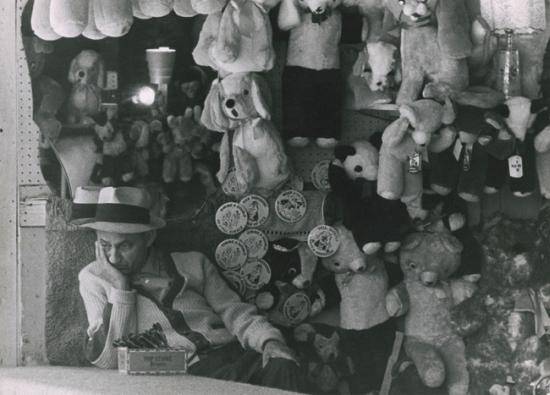

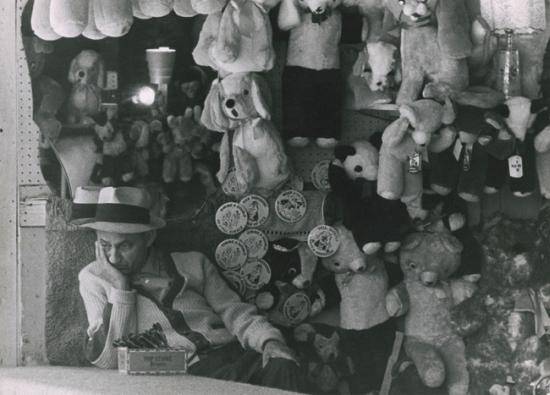

Savin Rock amusement park

West Haven, CT

Ronald Reis

_______________________

Knots: For an Interactivist Ontology [pdf]

Levi R. Bryant

A flower turns towards the moon and begins to bloom late in the night. A glass mug shifts between different shades of blue, going all the way to black, depending on whether it’s viewed under harsh fluorescent lights, natural sunlight, candlelight, or in a dark room. Our bodies swell in extreme heat and contract when it is bitter cold. A person’s helmet cracks and they scream in the unimaginably cold reaches of outer space, yet no sound is emitted for there is no air to carry the waves stirred by their vocal cords beings are beingwith, ecological, and interactive. Let us begin as if we were prisoners in Plato’s cave,; the world of common sense and ordinary language. In the cave, when we speak of objects, of things, we conceive them as discrete, individual entities composed of properties. A rock isn’t particularly interesting; at least to anyone other than the geologist or the builder. It is gray, irregularly shaped, and just sits there. We conceive of it as doing nothing until it is acted upon. Then it will move, but in a Newtonian fashion. Something else hits it and it goes flying. In this world, rock, the prisoner says, is inert. Unlike living things, it does nothing if not prompted by something else. This is generally what we signify by the term “object”; an inert clump that does nothing.

Yet cave walls and ordinary language should be no guide to ontology or questions about the being of beings. Our tendency is to conceive objects as collections of properties or qualities inhering in a substance. ...

(....)

... what if, instead of thinking beings in terms of their qualities and properties—striving to distinguish between the essential and the accidental –we instead treated beings as activities, doings, and powers? Ask not what a thing is, for that will lead you to a list of qualities or properties. Ask instead what entities do. Indeed, when discussing properties, don’t stop by simply enumerating the qualities that a substance, thing, or individual being possesses. Instead treat the quality as an event, a happening, an act, on the part of the substance. Here we wouldn’t say that the rock is grey, but rather that the rock greys. The greyness of the rock would be the result of a verb or an activity.

Certainly this is a strange way of talking about substances or entities in the world, but is there good reason for it? ... _______________________

Dolor

Theodore Roethke

I have known the inexorable sadness of pencils,

Neat in their boxes, dolor of pad and paper weight,

All the misery of manilla folders and mucilage,

Desolation in immaculate public places,

Lonely reception room, lavatory, switchboard,

The unalterable pathos of basin and pitcher,

Ritual of multigraph, paper-clip, comma,

Endless duplicaton of lives and objects.

And I have seen dust from the walls of institutions,

Finer than flour, alive, more dangerous than silica,

Sift, almost invisible, through long afternoons of tedium,

Dropping a fine film on nails and delicate eyebrows,

Glazing the pale hair, the duplicate grey standard faces.

_______________________

Franz Kline

b. 23 May 1910

_______________________

Demonstrating Precarity: Vulnerability, Embodiment, and Resistance

Arne De Boever interviews Judith Butler

(....)... It’s true that performativity broadly understood comes from a theory of language that talks about how language makes things happen, how certain categories can bring social realities into being, or produce certain kinds of effects. It’s a theory that in some way underscores the powerful effects of discourse, but there’s a question: how is it that we embody discourses, especially the discourses of gender? And what can we do, what kind of agency do we have in relationship to the categories that inhabit us, and that we in turn inhabit.

So for me, that meant thinking about what happens when we act in common, what happens when we act in concert. Hannah Arendt’s views have been important for me as I try to think about what performative action looks like, and demonstrations are of course a key way in which that happens. And when people are demonstrating about precarity, for instance, it’s not just that they get up and say, “We’re against precarity.” They are also embodied creatures in public space who are calling attention to the embodied character of their lives: this is a body that doesn’t have shelter, or this is a body that deserves shelter, or this is a body that ought not to be hungry, or this is a body that ought to have some sense of future, about its work or possibilities for flourishing. In other words, the body is not just a vehicle for the expression of a political view, but it’s the common corporeal predicament of those who need to be supported by proper infrastructure or social services, proper economic conditions and prospects. So that struck me as another way of making this point, and one that, I guess, for obvious reasons, is as important to me as it is to many other people at this point.

...(more)

_______________________

Ronald Reis Photographs - Duke Libraries

_______________________

The Far Field

Theodore Roethke

(....)

IV

The lost self changes,

Turning toward the sea,

A sea-shape turning around, --

An old man with his feet before the fire,

In robes of green, in garments of adieu.

A man faced with his own immensity

Wakes all the waves, all their loose wandering fire.

The murmur of the absolute, the why

Of being born falls on his naked ears.

His spirit moves like monumental wind

That gentles on a sunny blue plateau.

He is the end of things, the final man.

All finite things reveal infinitude:

The mountain with its singular bright shade

Like the blue shine on freshly frozen snow,

The after-light upon ice-burdened pines;

Odor of basswood on a mountain-slope,

A scent beloved of bees;

Silence of water above a sunken tree :

The pure serene of memory in one man, --

A ripple widening from a single stone

Winding around the waters of the world.

...(more)

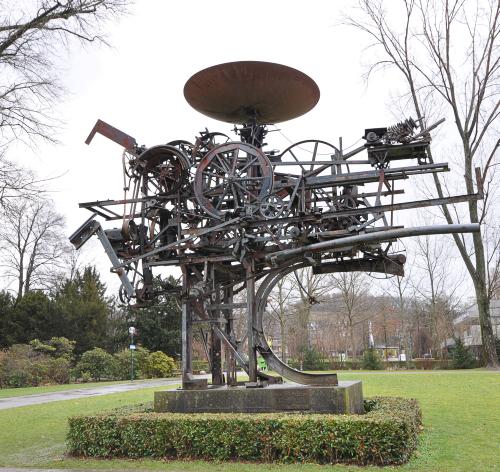

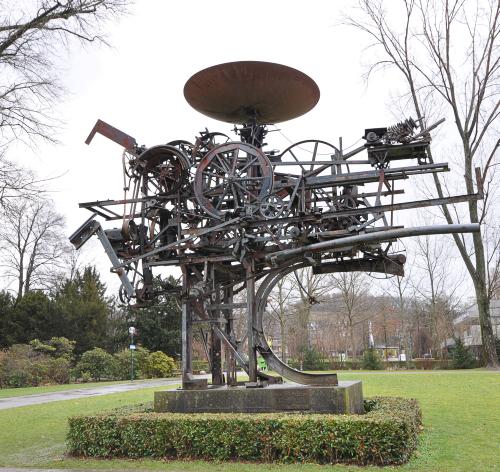

Heureka - Gesamtansicht

detail

Jean Tinguely

b. May 22, 1925

photo by Micha L. Rieser

_______________________

"Williams engages in the language of medicine in order to establish narratives of a nonnormative body that is crippled by the traumas of time but persists: mapping his body outward onto permanent or powerful objects and spaces."

'Maybe, it is only on Earth / that we lose the body?'

Williams and the decaying body

Samantha Carrick jacket2

The most compelling feature of William Carlos Williams’s poetry, for me, has perhaps always been the complex tango of virility and fragility that fight it out in his deeply autobiographical poetry. The idea that man could be both potent and capable of great frailty was a fact of his work that resonated with the vigorous and clumsy youth I was when I first encountered his work. Williams traces the deterioration and ultimate betrayals of his body in his poetry, reflecting on both the particularities of his condition and the universals of aging. Despite his best attempts, Williams’s body would always betray his impermanence, and developing medical technologies only seemed to solidify his sense of its precarity.

Williams was always a bodily poet — think of his famous celebration of “my arms, my face / my shoulders, flanks, buttocks” as he “dance[s] naked, grotesquely / before my mirror” in “Danse Russe” from Al Que Quiere! (1917). But late in his career, he very deliberately engaged with a poetics of the body and wrote through dozens of attempts that paralleled changes to his body that would eventually end his life.[1] In some work, he maps a body onto the landscape; later, he traces a poetic genealogy of successors including Allen Ginsberg. In other work, he explores his own deterioration through the metaphor of the A-bomb and through the disorienting effects of his mother’s senility.

As Williams aged, he attempted to redefine the bounds of his own skin through his poetry seemingly in order to reconcile himself to his own decay as well as to reflect on continued anxieties about poetic immortality. He enacted the anxieties inherent to creative types, hoping that as his body weakened around his still-sharp mind that he could somehow guarantee the gesture of immortality, even as he acknowledged the necessity of grounding himself in reality.

...(more)

via berfois

_______________________

Jason Nocito

The Wholeness Of Disparate Parts: A Conversation With Jason Nocito

The Great Leap Sideways

_______________________

"The Book as a Container of Consciousness" [pdf]

William H. Gass

Wilson Quarterly.

(....)

Last, as if we had asked Santa for nothing yet, the adequate sentence should be resonant with relations, raise itself like Lazarus though it lies still upon the page, as if - always "as if" - it rose from "frozen life and shallow banishment" to that place where Yeats's spade has put it "back in the human mind again."

How otherwise than action each is, for even if - always "even," always "if" -I preferred to pick the parsley from my potatoes with a knife, and eat my peas before all else, I should have to remember the right words must nevertheless be placed in their proper order: that is, parsley, potatoes, and peas . . . parsley, potatoes, and peas. . . parsley, potatoes, and peas.

That is to say, the consciousness contained in any text is not an actual functioning consciousness; it is a constructed one, improved, pared, paced, enriched by endless retrospection, irrelevancies removed, so that into the ideal awareness that I imagined for the poet, who possesses passion, perception, thought, imagination, and desire, and has them present in amounts appropriate to the circumstances - just as, in the lab, we need more observation than fervor, more imagination than lust there are introduced patterns of disclosure, hierarchies of value, chains of inference, orders of images, natures of things.

(....) via Biblioklept

_______________________

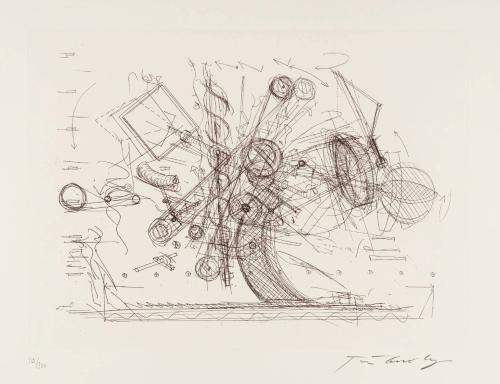

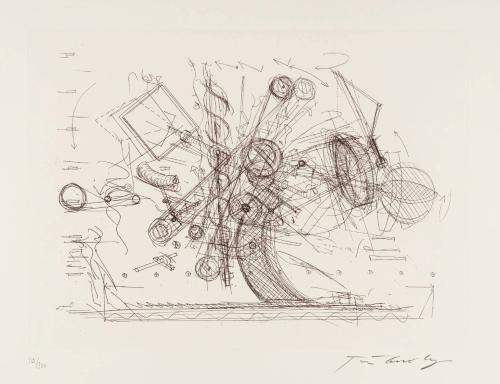

Chaos

Jean Tinguely

1972

_______________________

The Thunder of Sounding Whales

David Eggleton reviews Puna Wai Korero: An Anthology of Maori Poetry in English, edited by Reina Whaitiri and Robert Sullivan

Landfall Review

(....)

Poetry is ‘news that stays news’, wrote Ezra Pound, meaning that after the elapse of time burns away the circumstances that provide the impetus for a given poem, it endures and remains alive and kicking because of its own linguistic energies. Fossicking around in the archives of little magazines, Reina Whaitiri and Robert Sullivan have found a number of poems that remain alive, while the core of the book is made up of literary establishment poets: Hinemoana Baker, Rangi Faith, Keri Hulme, J.C. Sturm, Robert Sullivan, Apirana Taylor, and of course Hone Tuwhare, whose brilliantly burnished imagist verses would soar effortlessly into the heavens in any company:

On the skyline

a hawk

languidly typing

a hunting poem

with its wings.

(‘Bird of prayer’)

Beyond that, this anthology asserts the new Maori poets, a community of poets channelling ancestral voices for contemporary times – though some of them have been around for a while, better known for writing in other genres: Briar Grace-Smith, Witi Ihimaera, Paula Morris, Kelly Ana Morey, Ngahuia Te Awekotuku. In sum, the editors have assembled 78 poets of Maori heritage: the crew of a mighty waka rowing in unison, and mostly chanting rhythmically and in harmony – a polyphony of voices, as focused as any Maori delegation to the world.

This implies a certain amount of structuring and arranging since, as Robert Sullivan has pointed out, the notion of one united tribe of Aotearoa is a recent artificial construct. Formerly, this archipelago was made up of tribal lands controlled by a variety of autonomous iwi, often warring or competing with each other.

What unites the present cast is an implicit celebration of their inheritance of Maoritanga – once repressed and thought destined for museum-stuffing – and the effects of that on today’s notions of bicultural identity. These poets are by and large a stroppy bunch; not always loud or rowdy, indeed frequently they are subdued and subtle, but if gladness and self-affirmation are dominant motifs, so are iterations of historical and contemporary grievances – and a sense of previously suppressed voices busting out, bringing the news that stays news.

...(more)

via the page_______________________

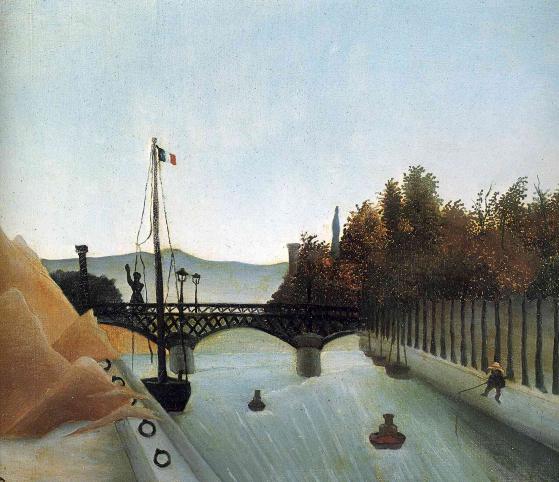

Heureka - Gesamtansicht

Jean Tinguely

photo by Micha L. Rieser

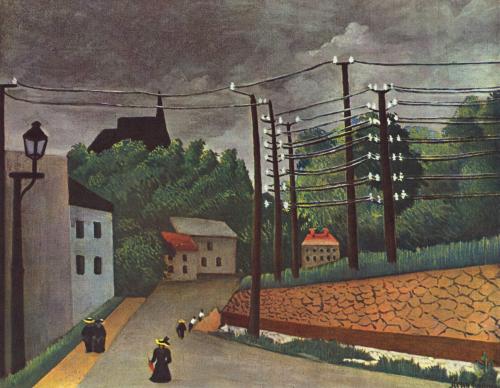

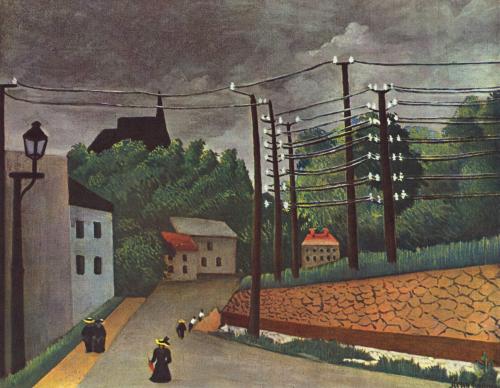

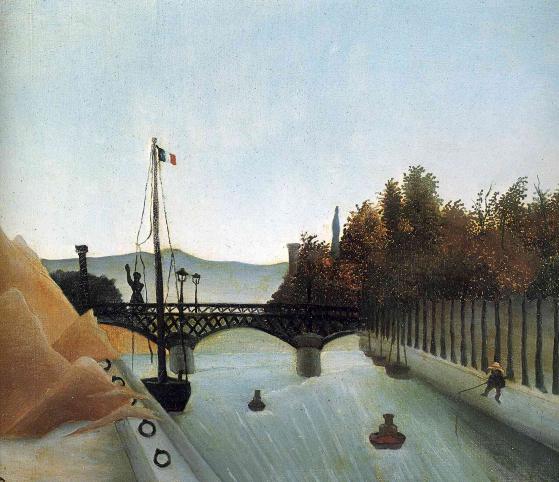

View of Malakoff Hauts de Seine

1903

Henri Rousseau

b. May 21, 1844

_______________________

Bach in Autumn

Jean-Paul de Dadelsen

translated by Marilyn Hacker

(....)

II

Once I knew days spent walking, the elms numbered toward evening

From milestone to milestone beneath a chromatic sky;

At night the inn where liver and fresh pork dumplings were steaming.

Once on free days I would walk all the way to Hamburg to hear the old master.

Handel had gone off in a post-chaise

To amuse the king of Hanover; Scarlatti wanders through Spanish feast-days.

They are happy.

But what use are the organ’s pedals, if not

To mark the indispensable way?

On this wooden path, worn like a staircase, daily, whether

Under the Easter trumpets or the paired Christmas oboes,

Under the rainbow of heaven’s and human voices

From milestone to milestone repeating my earthly voyage, I followed

The progression of the double bass.

Above the horizontal road that merchants take, not without risk,

To bargain in the shops of Cracow

For wigs, perfumes, pelts from the stalls of Novgorod,

A lark soars alone in the holy vertical.

Before the wingspread soul in its Sun’s wake

Can spring forth beyond the tomb, the rules, the law,

This earth must be learned in all its difficulty.

...(more)

_______________________

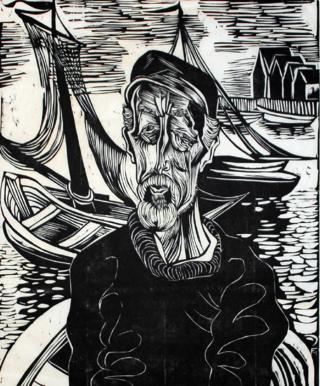

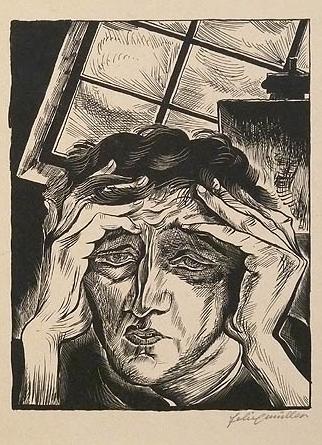

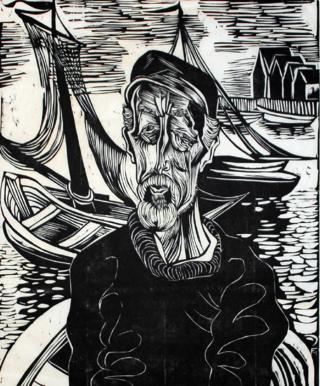

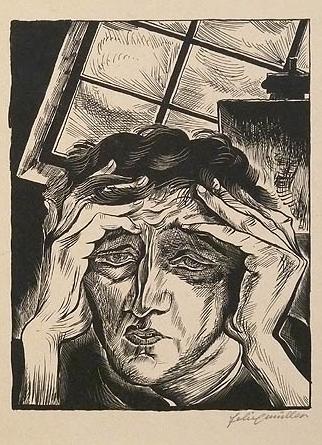

Conrad Felixmüller

b. May 21, 1897

_______________________

Taking a Measure of Happiness

David Beer reviews The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold us Well-Being, by William Davies

berfois

(....)

... Put simply, the question is whether happiness should be understood as being measurable, that is to say, that it can be captured in bodily responses and brain functions, or if we should think of it as something transcendent and intangible. For Davies, neither of these is likely to very gratifying – although, given the focus of the book, he understandably seems a little less concerned by the later. The important point for Davies is that both of these approaches simply ‘flip the same dualism’. His point is that in the case of the happiness industry – an industry built to promote our happiness, to limit our sadness, and to make us more profitable – the more subjective, mystic and ethereal accounts of happiness simply exists to ‘plug’ any ‘gaps’ left by more objective, scientific or neurological accounts. Some other approach is needed, he argues, one that is based on listening and a more political and sociological understanding of happiness and the conditions that facilitate or erode it. The case he makes is compelling. The book describes, in detail, an industry that has emerged that is designed to measure, manipulate and control our emotions. The examples roll from the pages, and the scale of the reach of this kind of economic behaviourism is startling. As Davies tellingly notes, ‘the current neuromarketing frontiers of behaviourism make John B. Watson look positively innocent by comparison’.

...(more)

another review, by Joanna Scutts

_______________________

Conrad Felixmüller

_______________________

The Empathetic Camera: Frank Norris and the Invention of Film Editing

Henry Giardina

The Public Domain Review

(....)

McTeague’s depiction of an early commercial film audience is a scene that fits queerly into the rest of the story, as a strange foreboding of things to come. In McTeague’s incredulity, his mother-in-law’s distrust of the film apparatus as a kind of trick, and his wife Trina’s enchantment at the device, the reader gets an encapsulated view of the different responses to one of the most violently modern events of the time: a trip to the cinema, to see a past reality unfold as if in real time before people who were slightly unable to believe in this reality. This is part of Norris’ grand project, throughout the small but thematically consistent body of work he produced from the age of twenty-nine to his death three years later at thirty-two: a depiction of the everyday shock of new media and industrialization, the concept of capturing time and presenting its fictional form as the truth, through the film apparatus. Even if the story of audience members fainting at the arrival of the train on-screen is, as many suspect, a fiction, the reason for its existence as lore stems from a very real disjuncture, part of the premise of the industrial age. How can the present reality hold a living document of the past? How can a unit of lost time make such a realistic reappearance in the present?

(....)

Norris grew up inside of the changing urban landscapes of Chicago and San Francisco, and made it his purpose, near the end of his life, to track these changes politically in his fiction. Yet his artistic development as a painter, a journalist, and finally a prose writer, was defined by his relationship to the visual world, and the changing ways of interpreting that world that were growing up around him during the time in which he lived.

(....)

In Norris’ 1897 essay, “Fiction is Selection”, he argues that writers are editors more than inventors. The job of “writer and mosaicist alike” is “to select and combine.” It is from the rough-hewn design in a writer’s brain that a story must be whittled, for nothing can be created that is not already, in some form, hidden in the folds of memory. “Imagination!” He writes. “There is no such thing; you can’t imagine anything that you have not already seen and observed.”

Film’s greatest strength was, from the start, its ability to emotionally manipulate viewers on a mass scale. It spoke to one as easily and as powerfully as it spoke to millions, controlling viewers seamlessly and guiding them toward a forgone conclusion that he believes he has come upon naturally, by an organic, empathetic process. Filmic storytelling was, in even its earliest manifestations, a way of transforming the frighteningly unpredictable human body into a predictable set of responses.

If, in the first quarter of the 20th century, the camera as mechanism stood for pure truth, editing was selection, manipulation, violence. If film as footage stood for impartiality, editing allowed for the presence of an author. Editing was the true artistic aspect of a mode of storytelling that was still too new to be considered an art form. Editing gave film what it desperately needed to become art in the eyes of its audience: a point of view.

...(more)

_______________________

Footbridge at Passy

Henri Rousseau

1895

Sarah Moon

_______________________

Ostashevsky and Timerman's Pirating-Parroting of Language

Joe Milutis

Bright arrogance #10, jacket2

(....)

Ostashevsky is himself an accomplished translator of Russian, but it is his original American poetry that seems ready-made to discuss the the multiple mutating filters of translation, or, to paraphrase Nabokov, the re-Englishing of Russian re-versions of an English re-telling of a Russian memory. His poetry’s battery of English sound effects—which generate surprise even from the most potentially cringe-inducing end rhymes—seem to retain with them a Russian bemusement at unnoted or ignored English assonances, while at the same time perhaps attempting to restore the “bad rhyme” principles of Alexander Vvedensky, a forgotten Russian poet who he’s translated. And the cross-cultural pollination extends to high and low culture, with signifiers of intellectual, philosophical, and mathematical erudition remolded into American vernacular idioms like rap, Dr. Seussisms, borscht-belt comedy and elephant jokes. Appropriately enough, the epigram that heads the collection Iterature, in his poem “Autobiography”—“structaque sunt nostris barbara verba modis”—is a plaint written by Ovid about his attempts (no longer extant) to write in Getic (the language of his place of exile, corresponding with present day Romania, but which may have more generalized affiliations with the “gothic”—a productive engine of translational oddities, as we’ll see in future posts.) The longer quote reads something like “What shame, that I write this little book in a Gothic tongue! What barbarous words have been built into our style!” Metamorphosis, exile, drift . . . the translational gothic creates not merely new texts, but also new beings in process, who are untranslatable, or at least untranslatable back to their origins.

...(more)

_______________________

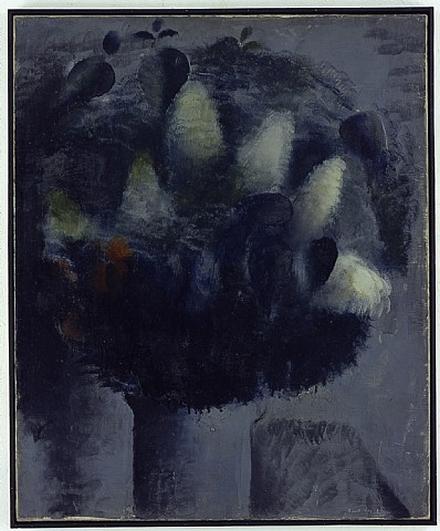

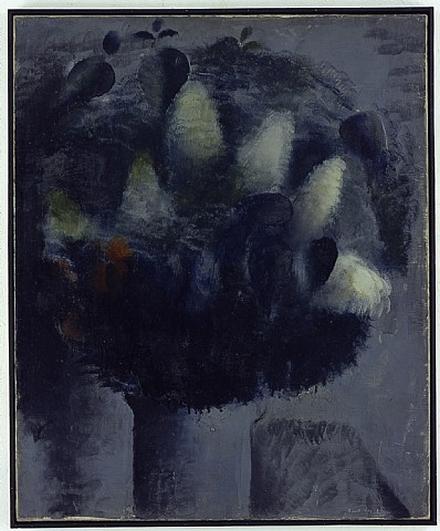

Le lilas blanc

Jean Fautrier

1927

_______________________

Slavoj Zizek: The Order of the Real

S.C. Hickman

Reading Zizek is like floating around in a vacuum of endless repetitions that seem to never find a resting place. I sometimes shift from Zizek to Wallace Stevens to remind myself that “the imperfect is our paradise” (from The Poems of our Climate):

(....)

III

There would still remain the never-resting mind,

So that one would want to escape, come back

To what had been so long composed.

The imperfect is our paradise.

Note that, in this bitterness, delight,

Since the imperfect is so hot in us,

Lies in flawed words and stubborn sounds.

The last stanza exemplifies the work of Slavoj Zizek who admits that words alone are uncertain good – not as in William Butler Yeats. When Zizek introduces his concept of the Gap we should understand that it is not what we might think it is: a Void between us (For-itself) and the proverbial Thing-in-itself. Which is the Idealist prognosis and Kant and his tradition as received in most academic scholarship of the last two hundred years. A move Quentin Meillassoux in his book After Finitude has marked by the appellation of correlationism, etc. No. For Zizek the Gap is the Real, the screen that distorts all our views onto reality.

…the Real is a gap in the order of Being (reality) and a gap in the symbolic order? The reason there is no contradiction is that “reality” is transcendentally constituted by the symbolic order, so that “the limits of my language are the limits of my world” (Wittgenstein). In the common transcendental view, there is some kind of Real-in-itself (like the Kantian Ding an sich) which is then formed or “constituted” into reality by the subject; due to the subject’s finitude, we cannot totalize reality, reality is irreducibly inconsistent, “antinomic,” and so forth— we cannot gain access to the Real, which remains transcendent. The gap or inconsistency thus concerns only our symbolically constituted reality, not the Real in itself.

So the gap concerns not the Real as it is in itself, but with our symbolic order of language that tries to constitute our universe of meaning we call reality. Yet, against any Idealist reading of this, of the notion of the subject’s performativity and creativity (““symbolic construction of reality”), Zizek will rather expose another truth of the ontological “collateral damage” of symbolic operations: the process of symbolization is inherently thwarted, doomed to fail, and the Real is this immanent failure of the symbolic.

...(more)

_______________________

Sarah Moon

_______________________

Someone is writing a poem. Words are being set down in a force field. It’s as if the words themselves have magnetic charges; they veer together or in polarity, they swerve against each other. Part of the force field, the charge, is the working history of the words themselves, how someone has known them, used them, doubted and relied on them in a life. Part of the movement among the words belongs to sound—the guttural, the liquid, the choppy, the drawn-out, the breathy, the visceral, the downlight. The theater of any poem is a collection of decisions about space and time—how are these words to lie on the page, with what pauses, what headlong motion, what phrasing, how can they meet the breath of the someone who comes along to read them? And in part the field is charged by the way images swim into the brain through written language: swan, kettle, icicle, ashes, scab, tamarack, tractor, veil, slime, teeth, freckle.

-

Adrienne Rich, Someone is Writing a Poem

_______________________

Trouble Songs

A musicological poetics

Jeff T. Johnson

jaket2

Trouble Songs: An invocation

Language is not only a means for saying, language is what we are saying. Record, we say, and we mean album, or we mean vinyl, or we mean history. Let the record show.[1] That we say record and not CD, tape, album, or document is integral to what we are saying. We place ourselves in history, and we place history in ourselves when we use particular language.

History exists as Trouble Song and is troubled by its[3] representation. Distinctions between Trouble Songs collapse into versions, iterations, variations, and interpretations. Just so, trouble is inescapable, and can be only partially elaborated. To speak the word “trouble” is to invoke trouble. The “Trouble Songs” project is such an invocation and elaboration. When we say “trouble,” we refer to the history of trouble whether or not we have it in mind. When we sing trouble, we sing (with) history. We sing history here; we summon trouble.

A Trouble Song is a complaint, a grievance, an aside, a come-on, a confession, an admission, a resignation, a plea. It’s an invitation — to sorrow, frustration, darkness. It’s part of a conversation, or it’s a soliloquy, and it’s often an apostrophe. The listener overhears the song, with sympathy. The song is meant for someone else, someone dead or gone. The singer doesn’t care who hears, and the song is a dare. Or it’s a false wager — to speak trouble is to summon trouble, but it’s already here.

Trouble is loss — or the threat of loss, which is the appearance of loss. A Trouble Song is impossible speech; it speaks about the inability to speak. Trouble is a lack of what once was possessed, a desire in absence, an absence in desire. Trouble is the presence of absence, a present of loss. It is impotence and despair, but a Trouble Song is not a negation or a denial. Its admission is its invitation. Trouble is spoken not only in resignation and exasperation, but also in defiance. Trouble is spoken as a challenge to death and defeat. In a Trouble Song, there is history, but there is no past — trouble is here and now. Which is to say, there is history, but it is not (the) past.

...(more)

_______________________

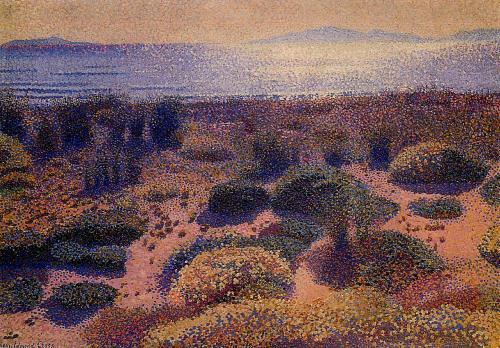

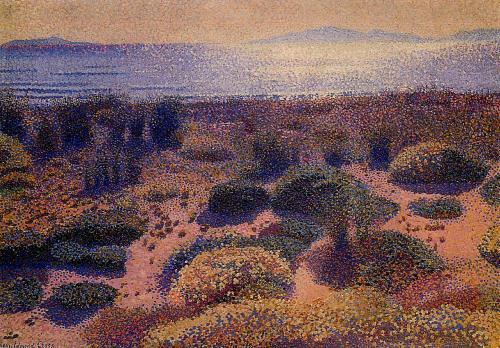

Plage de la Vignassa

1891

Henri-Edmond Cross

b. May 20, 1856

_______________________

Philosophical Percolations

All the philosophy that's not fit to print

Raison d’être

(....)

“Philosophy that’s not fit to print” denotes philosophical insights that do not fit easily into contemporary units of printed philosophy: the chapter, the article, the presentation. One of the exciting things about blogs is the way they add a new medium to the cocktail napkin, dinner conversation, and posted letter. The ideas expressed in good blog posts (as well as cocktail napkins, dinner conversation, and posted letters) sometimes do end up repackaged as chapters and journal articles. But their value doesn’t rest on that. You might have an interesting idea from teaching a class, reading a book, trying to make sense of something in popular culture, or from reading another blog, and it might not fit well with existing print dialectic for a variety of reasons. It may just concern topics that don’ t mesh well. It might not be weighty enough. Or it might shade into other discursive practices such as criticism (in the sense Noel Carroll describes), satire, raw appreciation, literary excursion, or a little pithy insight the defense of which would be short by the standards of Analysis. The insight might concern history, art, sports, music, food, leisure, trains, death, heartache, decline, enrichment, moral rot and recovery, the fact that nobody much uses the word “akimbo” any more, the sad fate of animals in various space programs, etc. etc. etc. etc. ...(more)

|