|

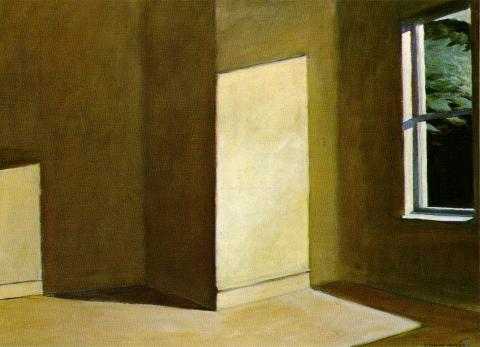

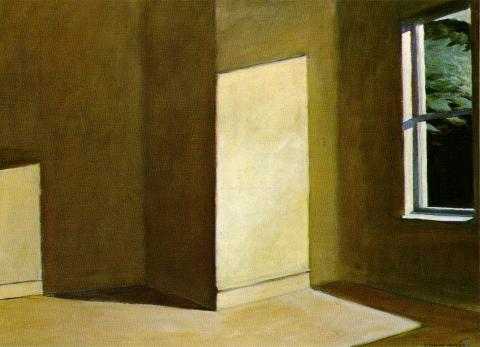

Sun in an Empty Room

1963

Edward Hopper

d, May 15, 1967

_______________________

Lost in Translation: Proust and Scott Moncrieff

William C. Carter

berfrois

Although Charles Kenneth Scott Moncrieff’s translation of À la recherche du temps perdu is considered by many journalists and writers to be the best translation of any foreign work into the English language, his choice of Remembrance of Things Past as the general title alarmed the seriously ill Proust and misled generations of readers as to the novelist’s true intent. It wasn’t until 1992 that the title was finally changed to In Search of Lost Time. “Remembrance of Things Past” is a beautiful line from William Shakespeare’s sonnet 30, but it conveys an idea that is really the opposite of Proust’s own. When Scott Moncrieff chose this title, he did not know, of course, where Proust was going with the story and did not correctly interpret the title, which might indeed be taken to indicate a rather passive attempt by an elderly person to recollect days gone by.

Proust’s theory of memory rejects the notion that we can simply sit and quietly resurrect the past in its true vividness through what he called voluntary memory. When we attempt to do this, we find that it doesn’t work very well. We remember very little and often only in a haphazard and rather bland way. On the other hand, Proust’s title should be taken to suggest a different approach: the Narrator’s search (recherche means both search and research in French) is an active, arduous quest in which the past must be rediscovered—largely through what Proust called involuntary memory, as demonstrated in the famous madeleine scene—then analyzed and understood, and finally, if your ambition is to preserve it in writing, transposed and recreated in a book.......(more)

_______________________

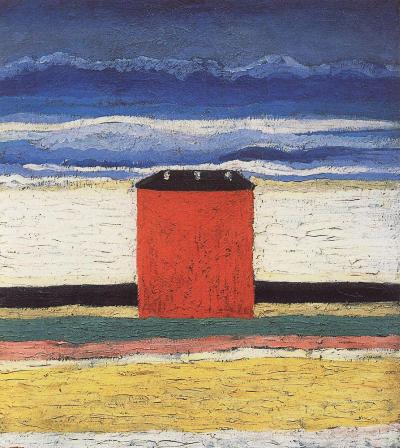

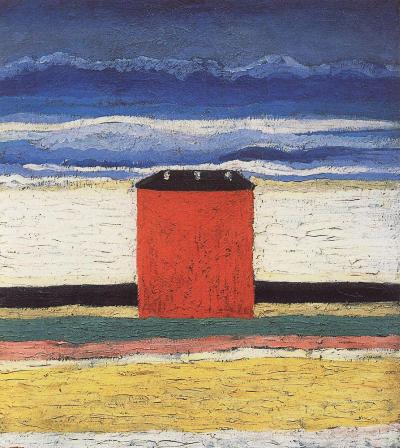

Kazimir Malevich

_______________________

from The Purification Festival in April

Inrasara

with translation from Cham/Vietnamese & note by Alec Schachner

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

(....)

Life no longer hesitates, no more wavering

swift, swifter

but slow too slow as if no possible way to be slower. He feels the

language of the hymns spill into millions of millions of cells

living or dead

overflow and stir them awake never to let them sleep again all

the millions and millions of sprouts are stretching their shoulders

to raise their heads.

Steps stomping more sturdily. I see – more firmly

the world fragmented and rejoined by an urgent breath

the fire at its last gasp.

He is cast out freed from the flames – his body covered with wounds

all the world wounded – only the smile untouched

the bliss untouched

millions of millions of water drops fly down to extinguish a surviving

spark straining to flicker one last time

extinguish misery, hopelessness on the faces. I see.

On the far side of elation

Resilience untouched they begin to take root once again.

...(more)

_______________________

Lady on a Tram Station

1913

Kazimir Malevich

d. May 15, 1935

_______________________

Frye Revived

Scott McLemee

(....)

If you spend much time in libraries these days -- wandering the stacks, that is, rather than sitting at a terminal -- you might have seen other long rows of dark green books with gold lettering, published by the University of Toronto Press and bearing the name of Frye.

The resemblance between The Collected Works of Northrop Frye (in 30 volumes) and the Frazerian monolith is almost certainly intentional, though not the questions such a parallel implies: What do we do with a pioneer whose role is acknowledged and honored, but whose work may be several degrees of separation away from where much of the contemporary intellectual action is? Who visits the monument now? And in search of what?

(....)

Frye’s relative decline as a force to be reckoned with in literary theory was already evident toward the end of his life; at this point the defense of Frygian doctrine may seem like a hopelessly arrière-garde action. (“Frygian” is the preferred term, by the way, at least among the Frygians themselves.) But the waning of his influence at the research-university seminar level is only part of the story, and by no means the most interesting part. The continuing pedagogical value of the Anatomy is suggested by how many of Frye’s ideas and taxonomies have made their way into Advanced Placement training materials. Anyone trying to find a way around in William Blake’s poetic universe can still do no better than to start with Frye’s first book, Fearful Symmetry (1947). Before going to see Shakespeare on stage, I’ve found it worthwhile to see what Frye had to say about the play. Bloggers periodically report reading the Anatomy, or Frye’s two books about the Bible and literature, and having their minds blown.

...(more)

_______________________

Feel Beauty Supply: post 1

Magdalena Zurawski

jacket2

At first I thought I would use this Commentary space to read through an online archive, but in the end such a gesture felt adjacent to my current preoccupations. What I hope to do instead is to elucidate a narrative of my own search for an adequate poetics, one that begins and ends with two very different theories, though each proposes “freedom” as the ultimate aim of poetic production. I want to attempt to rehearse an evolution of thinking around poetics that begins with Immanuel Kant’s The Critique of Judgment and ends with Hurston’s Mules and Men, though I’ll make some detours.

(....)

For the last twenty-five years of my life, or, since I left high school, I’ve struggled to find an adequate definition of POETRY. Not being able to get on with it, so to speak, is in many ways due to my own shortcomings as a person and thinker. Nevertheless not being able to get on with it, I think, had a lot to do with being a young person in the shadows of certain avant-gardes. I’m hoping that the story of getting from Immanuel to Zora will also be in part the story of coming out of those shadows. So this is just to say I am here for a little while and this is what I’ll be doing while I’m here. See you in a few days. ...(more)

_______________________

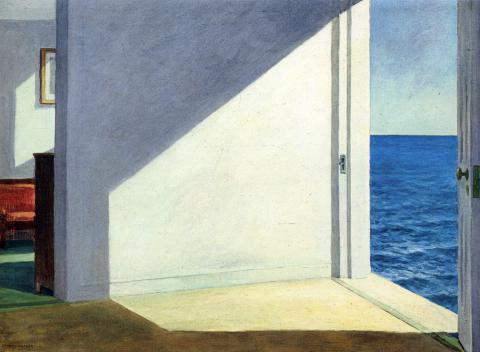

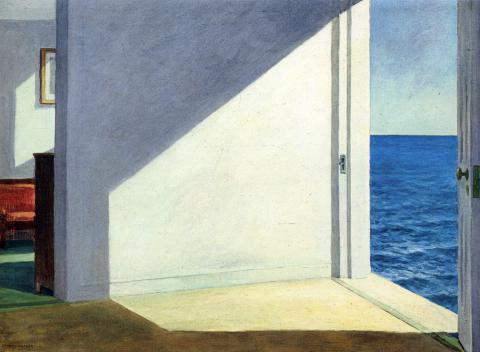

Rooms By The Sea

Edward Hopper

1951

_______________________

Pioneers in the Digital Snow

Mark Mordue

berfrois

Yeah, yeah, no time to think. Gimme gimme now! Thumbs up, thumbs down. Should I buy it or not? These appear to be the essential frames for modern criticism to function in today. Just serve the ever-shrinking moment and get the hell out of the way of the pleasure stampede. And please don’t bore us with an idea, let alone an essay disguised as a review. Please don’t bore us, period.

(....)

Tweets, blogs, social networking sites… if it can’t fit in your smartphone window and be grasped at a glance it ain’t worth your time of day. The trend perceptions on this electronic revolution have leant towards the obvious – more communication on every front, a greater necessity for speed in every act, the compression of information to match that speed, and with all that rapid-fire pressure a corresponding desire to find some alleviating air-space for the mind whenever and wherever possible. Zero sum game: triviality, gossip, and porn are king. Not to mention the brilliant sub-editor who can keep story titles like “Headless woman in a topless bar” rolling across the news breaks when you log out of your email. Click. It works.

It can seem like our culture is being ferried on its own electronic light all the way into hell. The digital equivalent to Aldous Huxley’s “soma” in Brave New World, where we become prisoners to our own desires, and raptured out of consciousness.

But is that really all that is happening for those who worry about such things rather than just indulge and enjoy? I feel more positive even as the house of the modern mind appears to be atomizing around me.

...(more)

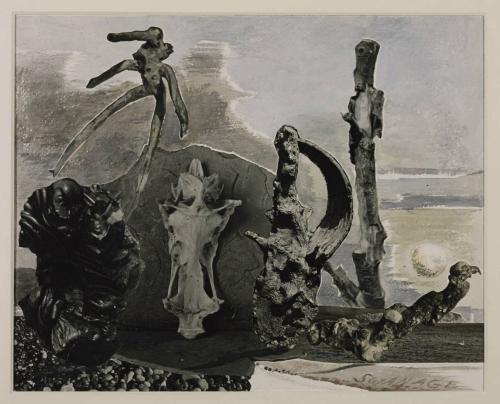

triple exposure

1907-08

August Strindberg

d. May 14, 1912

_______________________

on academic bewilderment

Richard Hall

(....)

And we can see that those governing networks that enforce learning gain, and the national student survey, and the research excellence framework, and the higher education achievement record, and the future earnings and employability records, and performance management, and new public management techniques and methodologies, and internationalisation strategies, and precarious labour rights, cannot care about all the ands. They cannot care that as well as teaching and assessing and administrating and researching and scholarship, that this is too much.

They cannot care that this reduces the capability of people and relationships to withstand stress.

They cannot care that this is too much.

They cannot care that this makes us anxious.

And this anxiety is driven by the need for us to live two half-lives. In one we try to be partners in a social construction; in social sustainability; in a willingness to address those global issues that will fuck our world over. Partners in trying to find solutions that are not beholden to the structuring logic of the market. Yet this half-life decays quicker than the other half-life – the demands made of us to treat our lives as services that can be commodified and exchanged. Our whole lives now reproduced as labour-power. Lost to us.

And in making sense of the loss our cognitive dissonance places the use-value and the exchange-value of our work in screaming tension.

And how can we survive this?

...(more)

via Forgottenness_______________________

Celestographs

National Library of Sweden

The Celestographs of August Strindberg

Douglas Feuk

cabinet

... what is remarkable, and what makes these images so "modern," is that they also concrete examples of a kind of chemical naturalism (as in the work of Polke, Kiefer, and many other recent artists). Strindberg insisted that art should try to "imitate […] nature's way of creating," and in these celestographs the image and the world have approached each other to the extent that they more or less merge. Whatever the coincidences were that created these pictures, the subject matter appears less as a photographic image than as a "work" by nature itself.

...(more)

_______________________

First Monday Volume 20, Number 5

The app-object economy: We’re all remix artists now

Paul Caplan

Abstract

Maps and messages, notes and news, photography and fitness, streams and shopping: the litany of apps through which we live our mobile data lives and through which state and corporate agents survey our data positions, set in motion a form of everyday remix. This affective cultural practice choreographed between ‘us’ and ‘them’ is deeply governmental, establishing subject positions and relationships. Drawing on the work of Timothy Morton, Levi Bryant, Ian Bogost and Graham Harman, this paper argues that this governmental remix mesh is best addressed as a matter of material objects and hyperobjects rather than as an assemblage or network.

A brief history of Facebook as a media text: The development of an empty structure

Niels Brügger

Abstract

This paper tells a history of Facebook from 2004 to 2013. It presents the big picture by focusing on Facebook as it presented itself to a user, that is the available semiotic and interactional elements (e.g., profile, wall, feed, commercials, etc.) as well as the functions and useforms which these elements made possible for a variety of actor types (profile owners, groups, companies, software developers, etc.). In addition, Facebook’s development is inscribed in a longer Web historical perspective with a view to identifying a general mechanism for Internet development.

_______________________

Houses at Estaque

1908

Georges Braque

b. May 13, 1882

_______________________

The Internet Imaginary: Between Technology and Technique

Nicole Pepperell, Duncan Law

(....)

Political contestation over which of these potentials will be realised is ongoing and by no means finally decided. The recent trend, however, has been toward the realisation of potentials favoured by powerful social actors - governments and large corporations - at the expense of potentials favoured by less powerful agents.

(....)

...this faith in the power of the Internet as a technology helped obscure the need to develop other kinds of techniques - rhetorical, social and political - to ensure that the desired technological potentials were in fact realised. Over the longer run, these alternative techniques have proven decisive for selecting which technological potentials would be developed, and which would be suppressed. Individuals and movements captivated by faith in the technology, found themselves blindsided when the technological “base” proved more adaptable to the existing “superstructure” than expected.

In the sections below, we explore how this process unfolded. We first examine the rhetorical techniques that primed early analysts to perceive the Internet as an intrinsically progressive technology. Next, we explore how the research and development of Internet technologies shifted in response to dramatic social transformations in later decades of the 20th century. These shifts illustrate the plasticity of technological potentials, and suggest how a network of social techniques help determine which technological potentials are primed for further development. Finally, we examine the role of political techniques in selecting the technological potentials that are successfully realised in practice, and we suggest that faith in technological determinism helped discourage the development of effective political techniques oriented to achieving more progressive technological potentials.

...(more)

'technique'M/C Journal

Vol. 18, No. 2 (2015) _______________________

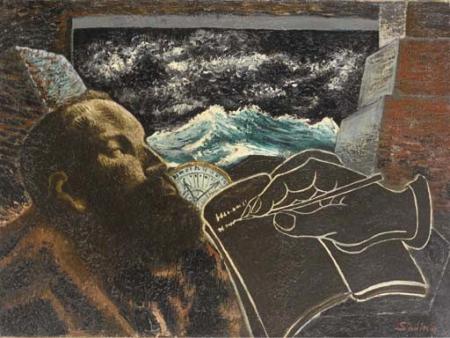

The Wave VII

August Strindberg

1901

_______________________

Five Poems

Robert Fernandez

conjunctions

Those You Live Among

I have no camera

no game no tent, no word no mon-

strance no belt, no vent no succor,

no assuage no guilt, no music

*

The boarders they play games with you

those whose stomachs are full

of steaks they toy with you, the house

is full of toys

*

And each day, crime is easier, those

I live among, those I live among let me have my

speech, I can

not speak rocks in oil flounder

in oil and window pane almond al-

mond who is fragrant enough to live

among? Who is fair enough to be set beside?

*

My days are broken

and setting

and more truthful

*

...(more)

_______________________

Night of Jealousy

August Strindberg

1893

_______________________

Speculations: new Irish poetry

a series by Walt Hunter

jacket2

Local objects

Walt Hunter

(....)

It is unsurprising that the Irish poetic imagination might dramatize the emergent experiences of contemporary survival as modes of setting out, casting off, or wintering away. Lyric, dramatic, and epic poetries have always used questions of travel to explore states of being. The poems I've been reading over the past five months also make their world travel the catalyst for visiting havoc upon their poetic worlds: this brings them into close relation with the contemporary globality of Ireland.

Far from being sentimental ballads of the emigrant gaze, Irish poems of travel, place, landscape, and tourism undertake elaborate interventions within lyric modes of elegy, myth, and dream vision. These genres, pressed into charting historical experiences of debt, surplus labor, opportunistic religious nationalisms, and, recently, immigration to Ireland, open up to reveal certain distinct poetic contradictions: going backward in time, speaking for the collective dead, suspending the processes of linguistic reference. This series has pointed to a few of those moments as they became visible to me.

...(more)

_______________________

Violin and Glass

Georges Braque

1913

_______________________

The Artist in Real and Virtual Company 6

The river at night

George Szirtes

(....)

Robert Graves said he composed best when in a mild trance well supplied with coffee and cigarettes. Let us say our poet is in a similar mild trance that allows him or her to advance an idea as if in a dream, with the assurance of dream where things happen according to rules of their own. Whatever had been contemplated or impinged on the consciousness at some other point in time has now been distilled into its own trace material and is capable of working by association, of undergoing metamorphoses. Chance and impulse are its friends and associates, the visrtual voices of the river become a form of company of whom little can be presumed except their flickering presence.

So we return to presence. All the while I write at night I am aware that people read what I write as I write it, that it is a form of nakedness. But I began with the notion of the listening presence, with Dylan Thomas’s lovers, with Li Po’s drunken companions, with Jean Valentine’s other solitary.There are also the travellers on trains and one’s elective masters whose ears are keen and minds most critical. Out in the night that is not night everywhere, the words flow by much like my life flows. Other eyes register them and may respond. But theirs too are on the stream. ...(more)

Martinique

1972

André Kertész

1894 - 1985

_______________________

Weird Solidarities

Karen Gregory

dis

Whereas past generations longed to know if there is an afterlife, today we face a living hauntology in the form of our data presences. We live on not only past death, as the recent Facebook end-of-year debacles have poignantly demonstrated, but we live beyond ourselves in and through black-boxed algorithms and their architectures of capture and deployment. While we might understand this as a form of posthumanism or by using the framework of human/machine relations, I suggest we think of it this way: as a form of “weird” solidarity not only with one another but with the very environments that are being made to be “expressive” (Thrift 2012) along with us. As value grows increasingly speculative, being drawn from the dual promise of data aggregation and its parsing—for data are only as valuable as the novel emergent patterns it can produce—such value is already predicated on a social body and the generative connections that can be forged among its constituent elements. These elements do not necessarily have to reduce to “the human.” Additionally, this is a laboring and productive body whether it “works” or not. In this way, this economy does not need “you,” but it is fully composed of “us.”

Rentier Assets

We are slowly coming to realize that the “sharing economy” is less about sharing than it is about creating new terrains of rent. Such terrains are innovative and disruptive not because they are necessarily creative, unique, generous, or helpful to the overall project of human life but because they attempt at all costs to circumvent production costs (including labor) and therefore reconfigure the relationship between production and value. Guy Standing (2014) writes, “Rental income enables people to make money simply through the possession of scarce assets. Sometimes assets may be ‘naturally’ scarce: if fertile land is owned by a few landlords, they need not work themselves but can rent it out to others for a high price. This income is rent, not profits from a productive activity, as the landlords do nothing to earn it aside from owning the land.” While we can point to platforms such as Uber and Airbnb as examples of such rentierism, the project of opening the commodity form to new forms of “tenancy” (Thrift 2012) is only beginning to find its true home as a form of governance via a hierarchical, rigid political/economic social structure. Rather than sell itself as an aristocracy in the making, enabling a few to own much, the sharing economy does quite the opposite. It suggests that participation in this economy is a form of peer-to-peer collaboration and cooperation, which leads to greater choice and flexibility. The key figure here is the enterprising, entrepreneurial individual—a savvy prosumer or, in Toffler’s words, a “proactive consumer”—who privileges access to goods and services over ownership. Bear in mind, this is an individual who already does own something—that is, has something to “share.” That something can be their home, their car, their pets, their time, their talents, or their attention, and that individual is often invited to share through the most practical of all invitations—the creation of passive income, or rent.

...(more)

Dis Magazine’s “Data Issue”

via —synthetic zero

_______________________

Mario Sironi

b. May 12, 1885

_______________________

In the beginning

Cosmology has been on a long, hot streak, racking up one imaginative and scientific triumph after another. Is it over?

Ross Andersen

aeon

(....)

The science of cosmology has achieved wonders in recent centuries. It has enlarged the world we can see and think about by ontological orders of magnitude. Cosmology wrenched the Earth from the centre of the Universe, and heaved it, like a discus, into its whirling orbit around one unremarkable star among the billions that speed around the black-hole centre of our galaxy, a galaxy that floats in deep space with billions of others, all of them colliding and combining, before they fly apart from each other for all eternity. Art, literature, religion and philosophy ignore cosmology at their peril.

But cosmology’s hot streak has stalled. ...

(....)

As I walked out of Steinhardt’s office for the last time, it occurred to me that our cosmos is once again a sphere. Our Earth has been demoted in recent centuries. It no longer enjoys its former status as the still centre of all that is. But it does sit in the middle of our observable cosmos, the sphere of light that we can detect with our telescopes. Gaze into this sphere’s reaches from any point on Earth’s surface, and you can see light coming toward you in layers, from stars and the planets that circle them, from the billions of galaxies beyond, and the final layer of light, the afterglow of the Big Bang.

We might be trapped in this snow globe of photons forever. The expansion of the Universe is pulling light away from us at a furious pace. And even if it weren’t, not everything that exists can be observed. There are more things in Heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in our philosophies. There always will be. Science has limits. One day, we might feel ourselves pressing up against those limits, and at that point, it might be necessary to retreat into the realm of ideas. It might be necessary to ‘dispense with the starry heavens’, as Plato suggested. It might be necessary to settle for untestable theories. But not yet. Not when we have just begun to build telescopes. Not when we have just awakened into this cosmos, as from a dream.

...(more)

_______________________

André Kertész

_______________________

The Artist in Real and Virtual Company

George Szirtes

edited text of keynote delivered at Inonu University, Turkey

(....)

It is not only poets who value solitude of course. Most tasks that require concentration involve a shutting out of distractions. Dylan Thomas’s lovers are elsewhere, Li Po leaves his drunken companions asleep and the very purpose of Jean Valentine’s studying of silence, or what she calls “learning braille” is to communicate with other solitudes elsewhere. The rages of the moon in Thomas isolate the individual, affirm his solitude. Everything is ‘elsewhere’.

Nevertheless the others involved in this act of concentration - the lovers, the drunken sleeping companions, the other solitudes - constitute a presence-in-absence, or, as my title has it, virtual presence. These figures are imagined and, usually, unspecific or, if specific, unaware of the condition of the poet. In one of the most beautiful poems of solitude, Coleridge’s Frost at Midnight, Coleridge is alone with his sleeping infant, conjuring solitude at the side of a precious unspeking other, his infant son..

Dear Babe, that sleepest cradled by my side,

Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm,

Fill up the intersperséd vacancies

And momentary pauses of the thought!

The poem ends with the fanous “secret ministry of frost” and, once again, the moon, We might argue that this vision of writing alone, by moonlight, with a sense of sleeping or absent others is a specifically Romantic trope and there may be something in that, but it is not only the poets of the Romantic period who employ it. Li Po and Jean Valentine are not Romantic poets, neither is Alexander Pope who writes an early Ode to Solitude, nor for that matter are T S Eliot or Michael Hofmann who also write about and out of the condition of being alone.

...(more)

_______________________

an ostentation of solitariness:

looking for the wilderness in abney park cemetery

Bridget Penney

3am

‘a multitude of thick bushes and trees, affecting an ostentation of solitariness in the midst of worldly pleasures’

Michael Jermin: A Commentary on the Whole Booke of Ecclesiastes, 1639

(....)

‘Close by [Clissold Park] is Abney Park Cemetery, which is now so crammed with corpses as to make it reasonable to indulge the hope that before long it will be closed as a burial place, only to be re-opened as a breathing space for the living. And as the distance which separates these two spaces is not great, let us indulge the further hope that it may be found possible to open a way between them to make them one park of not less than about a hundred acres.’

W.H. Hudson: Birds in London, 1898

(....)

The seventeenth century garden wilderness, like the ‘managed wilderness’ which fills Abney Park today, embodies various ideas about people and nature, organised in a way that is no less deliberate for not being aggressively overt.

Jermin’s rather disapproving ‘ostentation of solitariness’ touches some relevant points about quite what people might be looking for in the wilderness. Ostentation and solitude should be mutually incompatible because if you’re physically alone there is no one around to show off to. Logically extended, this reaches a peak of absurdity with the living folly of the garden hermit whose whole job is to demonstrate the fact that he lives by himself: a far cry from what Jermin might have regarded as the unostentatiously solitary Desert Fathers, deliberately locating themselves so far beyond areas of settlement and cultivation that their privacy was unlikely to be disturbed. But where there is no ready access to vast tracts of uncultivated and uninhabited space, it can be difficult to be alone, when you would like to be, without someone seeing you. This may be why, ‘in the midst of worldly pleasures’ the wilderness of the English seventeenth century garden developed as a planned, and sometimes even as an enclosed, space. A brief article on the National Trust website describes them thus ‘Wildernesses, not exactly wild, but a woody place for intrigue and exercise.’

...(more)

_______________________

André Kertész

_______________________

Celan / Joris

Donald Wellman on Paul Celan, Breathturn into Timestead: the Collected Later Poetry, translated by Pierre Joris

immanent occasions

In the case of Paul Celan, more so than other poets with the possible exception of Louis Zukofsky, the reader is confronted by the slipperiness and multivalency of individual words. This phenomenon of innovation and concentration, this cast of mind often increases with age. Edward Said wrote a fabulous book on the topic of age and its relation to poetic innovation. A flinty disposition may then engender a hard-edged poetry of inflexible compactness, but yet also a poetry that demolishes borders, fusing memories. One suspects that individual words and phrases come to hold private meanings as well as etymological associations that map the whole of literary history.

...(more)

Swanage

c.1936

Paul Nash

b. May 11, 1889

_______________________

Dwelling with Place: Lorine Niedecker’s Ecopoetics

Steel Wagstaff

edge effects

(....)

One of the most compelling parts of Niedecker’s thought is the almost complete absence of egotism. At several points in her correspondence with urban male contemporaries, she adopts self-effacing epithets that critics usually read as some combination of modesty, timidity, or gendered deference. For instance, she jokes with her longtime mentor Louis Zukofsky that in place of an author photo like the one that has appeared in his most recent book, “They can put a creeping mint for me when I have a book—the ditches along the road are full of it this spring here, a bright blue flower and leaves smelling very strong of mint—a wonderful ground cover, no grass gets thru it.” She also refers to herself in her letters and poems as “just a sandpiper in a marshy region”; “a little bunch of marshland violets offered to the crooked lawyer”; “the solitary plover / a pencil / for a wing-bone” and “the lowland leek—of the lily family, tho.”1 Rather than being purely self-abnegating, I find her claims of affinity with these small plants and birds delightfully humble, democratic, and ecological. “Plain member and citizen,” indeed!

Niedecker’s sense of kinship and identification with other biotic elements is woven throughout her poetry. Her remarkable long poem “Lake Superior” begins with the insistence that

In every part of every living thing

is stuff that once was rock

In blood the minerals

of the rock

and she writes wryly in her poem “Wintergreen Ridge”:

It all comes down

to the family

‘We have a lovely

finite parentage–

mineral

vegetable

animal’

Instead of fretting over how such a finite parentage might threaten our “humaniqueness,” Niedecker welcomes our bond with nonhuman life and seeks instead to endow us, as she writes in “Paean to Place,” with a deeper appreciation for the “sea water running / in [our] veins.”

...(more)

via The Page_______________________

Zhang Daqian

b. May 10, 1899

_______________________

Undead Letters and Archaeologies of the Imagination:

Review of Michael Joyce’s Foucault, in Winter, in the Linnaeus Garden

Dave Ciccoricco

(....)

At the end of that interview segment, in contextualizing his comments about the “end of man,” Foucault adds, “I don’t say the things I say because they are what I think, I say them as a way to make sure they are no longer what I think. […] To be really certain that from now on, outside of me, they are going to live a life or die in such a way that I will not have to recognize myself in them” (Claris). In this gesture, one gives life to one’s thoughts in language so that such thoughts may live on (or die), in effect, separate from and even unrecognizable to their thinker (an added irony here of course is that the sentiments in question are themselves, after decades, newly undead).

There is perhaps, however, an inverse case—a genre no less—that involves employing language expressly not to give life to one’s thoughts in the first place: the unsent letter. An unsent letter is the paradoxical message par excellence, as I quite literally address another and yet communicate only to myself. In effect: I have said what I do not or no longer wish to say, and I have not given life to my thoughts in order to make sure that I will never, to your mind, believe them. Interrogating the status and resonance of unsent letters is one of the tantalizing tasks of Michael Joyce’s latest novel, Foucault, in Winter, in the Linnaeus Garden.

Even more seductive is the novel's framing conceit, an imagined life of Foucault spanning several weeks of his dark Swedish winter in Uppsala, in 1956, at the end of his relationship with the composer Jean Barraqué, and at the beginning of the project that would become his first major work, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. ...(more)

_______________________

Zhang Daqian

_______________________

Waywords & Meansigns—Composing with the Explosion of Language

How do you "understand" James Joyce to translate him? Rebecca Hanssens-Reed in conversation with Mariana Lanari, musical translator of the "Wake"

asymptote

(....)

The text is never going to be accessible. It’s about changing the approach towards the text. I know a lot about Finnegans Wake because I’ve read and studied it for five years, but everything that I studied brought me to the conclusion that I first had when I read the first four pages of the book. Which is: this anxious pleasure of not understanding something that you should understand. In my case as well—I’d read Ulysses before, and I’d studied Ulysses before—and I can consume English literature a lot, but suddenly you get a book that you cannot understand. To me this is fascinating. What is there—and why, what, how, how do you go on with it?

I’m Brazilian and was educated in a German school, so I always felt foreign, in a way, in my environment. I was sent to Germany in an exchange, and I almost didn’t speak any German then. So I discovered many words in a very severe and strange way that had this kind of stomach-pleasure-anxiety about them. And even today, I live in the Netherlands, and still speaking German—it’s a difficult language. So I find it interesting to inhabit a text where you feel foreign, and you catch twenty or fifty percent of it. You find a way around the not knowing everything.

I really love this tension of being very close to knowledge and not reaching it. It mimics reality in a way. You don’t know the person you’re sleeping next to, you know?

...(more)

_______________________

Summer Garden

Paul Nash

1913 _______________________

Critical Cartography

Rhiannon Firth

berfois

(....)

Critical Cartography is therefore, in the first instance, interested with theoretical critique of the social relevance, politics and ethics of mapping. The assumption that this is even a possibility – that maps are not simply neutral tools but rather strategic weapons that express power – leads to a second, practical, aspect of critical cartography. Groups and individuals at a grassroots level can also use mapping for a variety of purposes. Maps can be used to make counter-claims, to express competing interests, to make visible otherwise marginal experiences and hidden histories, to make practical plans for social change or to imagine utopian worlds.

It is important to note that maps are expressions not only of power, but of desire. Maps themselves can be objects of desire – some people enjoy looking at maps, or collecting historical ones. Maps also project our desires onto the landscape, they can map our hopes for the future, what we desire to see and that which we wish to ignore or hide. The process of mapping can also bring new ways of being and relating into the world, for example, we might experiment with new ways of organising and making decisions, such as non-hierarchy and consensus.

...(more)

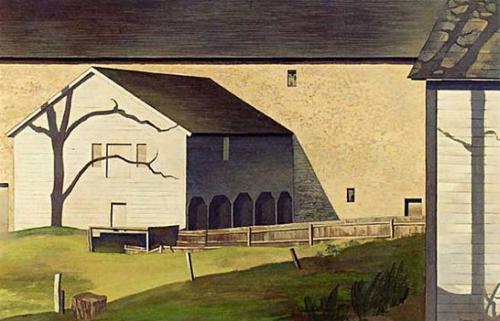

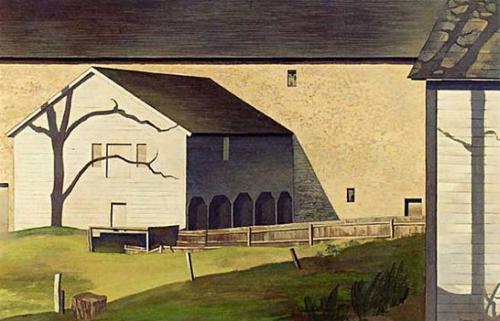

“Shaker Barn”

Charles Sheeler

1934

_______________________

new england irrelevancies

Andrew K. Peterson

3am

After Charles Sheeler

Curving matter felt

A bustle foliage, a dream a cause a windfall farm seeking foliage. The mom and pop got

driven. Pan creak apple. I was only thinking and what I’m driving at is town line

counting empty leases. Counting chains with prepped meals. Staying warm in a windfall.

A pop or mom apple pan creeks off the catch-and-release. The case for the lease empty.

Management teems an experiment for empty palette waste managements. Riding to the

factory

dream rain into foliage, the management dreams of rain. Drive waste to pan apple creek.

Booked

the motel and curving matter felt a hustle into foliage

//

apostle

ape hustle

apropos:

impossible muscle

why pun the punk

via Petron

or soft skating pink

purloined

protractions

with interloper’s purpose

hear the walrus

singing in her cave

for those who can’t listen

for there I sing

...(more)

_______________________

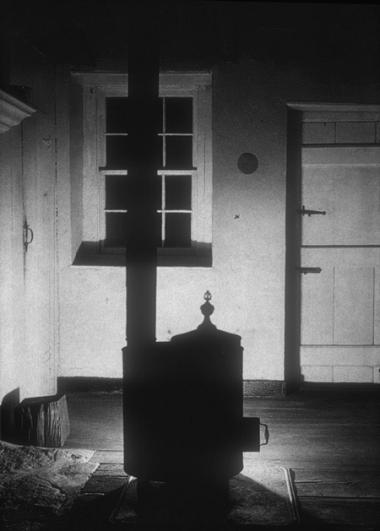

"Shadows and Substance"

Charles Sheeler

1883 - 1965

_______________________

Rilke and Things

Idris Parry

(....)

Although Rilke doesn’t say so, there’s no doubt he is conscious of the difference between his own hesitant production so far and the evidence of colossal activity he now sees before him. Rodin’s achievement, he tells his wife, is like the labour of a century, an army of work.

As the two men were sitting in the garden, a little girl came up – Rilke assumed she must be Rodin’s daughter. In her hand she had a tiny snail, picked up from the gravel, and she now brought it for the sculptor’s inspection. He looked at it with great interest, then remarked to Rilke that this minute shell reminded him of the surface of Greek masterpieces. Rilke never forgot this lesson in vision, how the fabulous can emerge from the fact observed without prejudice. The trivial is no more than a personal opinion, a category invented to make us feel important. In the work of Rodin, he notes the utter absence of self, an open commitment, patience.

‘There is in Rodin,’ he said some time later, ‘a dark patience which makes him almost anonymous, a quiet superior forbearance, something of the great purity and patience of nature.’ In that letter to his wife about his first meeting in the garden, Rilke reports that Rodin’s advice to him as a poet was concentrated in these words: ‘You must work, do nothing but work. And you must have patience’.

The meaning of the word ‘patience’, as Rodin used it and as Rilke was to use it evermore, is unhurried and uncommitted exposure to experience, to all experience without exception, as the earth is constantly exposed to sky and elements, a natural process. According to Kafka, it is because of impatience we were expelled from Paradise; it is because of impatience we do not return there. This, according to him, is the main human sin. He starts off with two, so we must perhaps be grateful when he eventually says there is only one.

Bearing in mind Rodin’s advice to work and to have patience, it is worth noting that Kafka’s two sins are the exact negatives: indolence and impatience. That he settles on impatience suggests a dreadful certainty that there is no other obstacle to understanding. This impatience is not mere irritability of temper but the imposition of opinion on fact, making up your mind before the event instead of letting the event shape your mind and dictate the next move.

(....)

Rilke once said there is nothing wiser than the cycle. He is fond of the image of the tree as a cyclic construction, the fountain too, which is a kind of liquid tree. Or is the tree a frozen fountain? Leaves grow, fruit ripens, falls, rots, feeds the roots, and nourishment ascends into the branches, leaves grow, fruit ripens… In the fountain water falls into the basin, which Rilke calls in one of these sonnets an ear of the earth: if you put a jug there to catch water, he says, you interrupt a conversation. The tree must be one of the earliest objects of human worship, the golden bough, and fountains seem to have a habit of becoming holy wells.

These cyclic images affirm the unity of existence. And, in a unified world, can there be separate senses? Or are these human accidents, indications of our limited perceptions? That our perceptions are limited must be obvious to anyone who has tried unaided to hear the whisperings of bats or has seen the wonders of the enlarged world revealed by the microscope. Where would the extended senses stop? Would they stop? Rilke speculates about this in an essay called ‘Primal Sound’. The five senses spread out like a five-fingered hand. What lies between the fingers? Can we be sure that the five sectors, taken together, cover the whole of possible experience?

Rilke declares his hand (if you will excuse the pun) in the opening lines of the first sonnet of the sequence, and here we come across a characteristic which makes these poems so puzzling at a first reading. Or even a second reading. The audible song is transformed into something visible. There are people who claim to see colours in music. Rilke now sees a tree, and in a peculiar place:

There a tree ascended. O pure transcension!

O Orpheus sings! O tall tree in the ear!

We are invited to see the song of Orpheus. ...(more)

_______________________

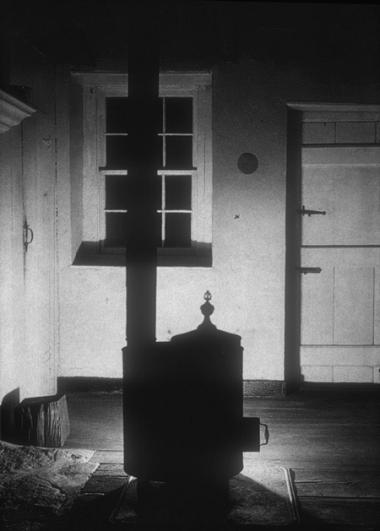

Interior with Stove

Charles Sheeler

_______________________

Bataille on Lascaux and the Origins of Art [pdf]

Richard White

janus head

(....)

As the editors of The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs put it: “[Bataille’s] text is of debatable interest in the eyes of the prehistorian.” With the recent translation and publication of Bataille’s other essays on prehistoric art, however, it is now clear that Bataille’s interest in prehistory began early on and remained a constant theme from the early 1930s until the end of his life. Lascaux became a focus for his own self-understanding, and it offers us a key to his intellectual project.

In this essay, I want to reevaluate Bataille’s discussion of Lascaux as a significant work which has been unfairly neglected. To this end, I consider three distinct but related lines of inquiry: First, I look at Bataille’s account of art in the Lascaux book: does Bataille subscribe uncritically to a particular view of what art is; or does he offer a coherent argument concerning the nature of art which would be helpful to artists, philosophers or scholars of prehistory? Second, I examine Bataille’s account of transgression, which is a central category in most of his writings: does Bataille show the significance of transgression in helping us to understand prehistoric people; or is his account more strained and theoretical than his own experience of Lascaux might warrant? Finally, I look at Bataille’s account of the origin—in Lascaux, the origin of art and the origin of human beings: does he unfairly privilege the origin, as opposed to the end, as the moment at which everything is supposed to be clear and given? Or does his attempt to recover the origin help to illuminate the trajectory of human history which follows from this point?

Bataille visited Lascaux many times and he was clearly amazed by what he saw: “Directly we enter the Lascaux cave, “ he comments, “we are gripped by a strong feeling we never have when standing in a museum, before the glassed cases displaying the oldest petrified remains of men or neat rows of their stone instruments. In underground Lascaux, we are assailed by that same feeling of presence—of clear and burning presence—which works of art from no matter what period have always excited in us. Whatever it may seem, it is to tenderness, it is to the generous kindliness which binds up souls in friendly brotherhood that the beauty in man-made things appeals. Is it not beauty we love? And is it not that high friendship the passion, the forever repeated question to which beauty alone is the only possible reply?” Reading passages like this one, we may wonder whether Bataille’s enthusiasm sometimes got the better of him; although it should be pointed out that even the soberest scholars describe Lascaux in equally rapturous terms.6 Here we must ask whether Bataille’s work on Lascaux really helps us to understand prehistory and what it means to be human. And in what respect does the Lascaux book help us to understand Bataille?

_______________________

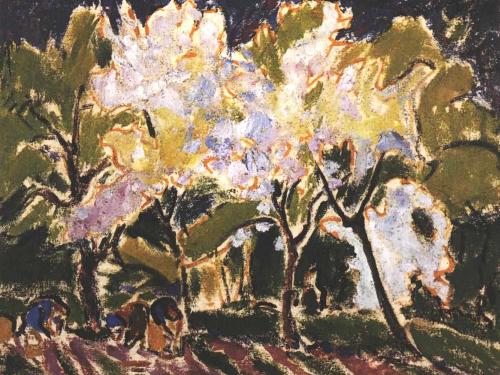

View of New York

Charles Sheeler

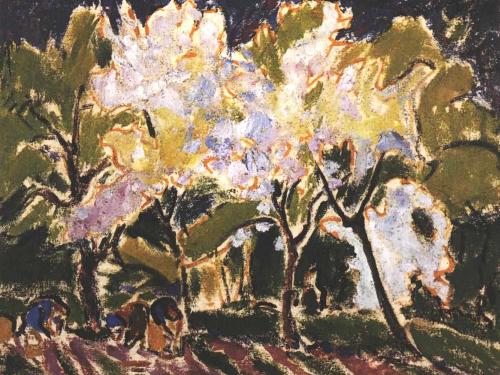

Landscape in the Spring

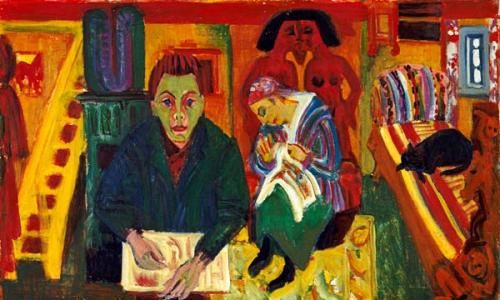

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

b. May 6, 1880 _______________________

Four Poems

Aditi Machado

conjunctions

Leech Country

As within the raucous meditations of high priests you find yourself moving and trepidatious and in the far black moving black trees. For once when I say you I mean you, the morphology pristine. You may not think there is anything particular to you but you may also not think. Somehow volume is more believable when the leech makes love to you when you deplete. Many days go by undoing the central leitmotifs of your life. You have no nature, only wilderness. This is what it is like may not be said. This is what it is not like neither. You take your apophasis and your deliquescence and when it rains like this you have felt everything. Petrichor, petrichor, you call, wishing for a way to always be seed.

...(more)

_______________________

Sailboats at Fehmarn

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

1914

_______________________

Some Minimal Poems, from "Poemínimos Completos"

Efraín Huerta

translated by Jerome Rothenberg

A Poem of Shipwrecks

1/

Me here

Navigating

Through the

Civic

Waves

2/

Me here

No longer struggling

In the

Icy waters

Of the ego’s

Calculating

Mind

3/

That one

Drowns alone

And lonely

In a

Glass

Of water

4/

Then I

Keep on

Swimming

In betwixt

Two waters

5/

One day

It won’t be raining

Into buckets

It will just be

Raining

Buckets

6/

You always

End up

Kicking off

Just like

A drowned man

...(more)

_______________________

Self-portrait

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

_______________________

#AndNow2015: You May No Longer Recognize Your Sediments:

Seismologies of the Self and Other Bodies

Laura Vena

entropy

(....)

I have a fairly baroque writing technique. First, I am drawn to a subject that awakens an exuberance in me. And then I move into that subject as if it were a house, I pace back and forth inside, dwell in its various corners, watch it proliferate cobwebs, try to disassemble its architecture. I research everything about the house, the materials used to make it, who lived there, what the land looked like before the structure, who passed through that space, how was the space transformed by the dreams of those who spent any time there.

Imagine the roads you’ve forgotten or the fields you’ve lost. What do you put in their place? New roads, more fields. Amputated gestures, hollowed

Loopholes in the center of things

Describe what it’s like in the field at night; describe the yellow with the indigo sky. There are people that regard flowers much like humans. There are memories of fields she can map by the bones underneath

And their dust faces, recollections combusting

I take notes, I draw maps that I constantly add to or correct, I seek out any recorded memories, I make new ones on top of them, I go on field trips that consist of climbing in caves, navigating by ancient oak, or unending walking, exploring, getting lost, I try to read the land, I scan the horizon as if I’m a lizard, a cloud, me.

“So long as the human consciousness remains within the hills, canyons, cliffs, and the plants, clouds, and sky, the term landscape, as it has entered the English language, is misleading. “A portion of territory the eye can comprehend in a single view.” This favors the eye that gazes, that sweeps across a vista, adding perforated lines at the boundaries, that perceives and surveys, but doesn’t experience or interact, doesn’t vibrate with the wind. This idea that we are separate, alone. “Viewers are as much a part of the landscape as the boulders they stand on.” We are in the attic with the stars.

...(more)

_______________________

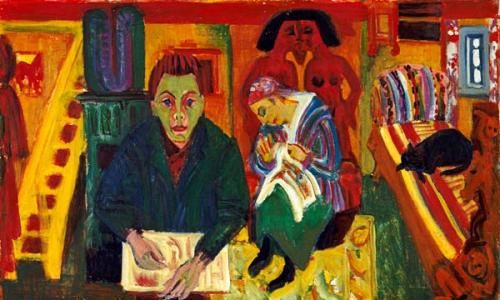

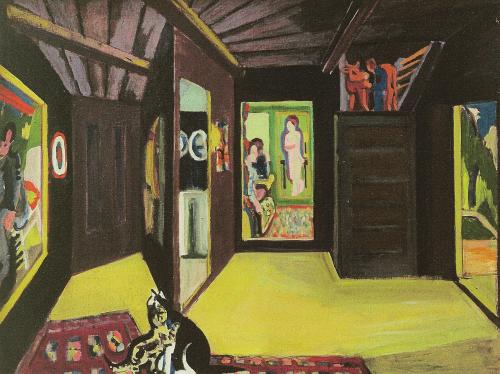

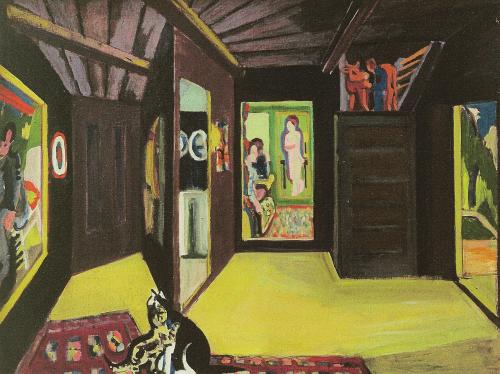

The Living Room

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

1920

_______________________

On Not (Yet) Getting It

The Pleasures of Readerly Discomfort and Difficulty

Sarah Tindal Kareem

berfois

(....)

The experience of reading theory, and also of reading “practically,” as I was trained to do, involves some of that same sensation of being on the brink of something new and revelatory. As Donald Barthelme observes, difficulty is inevitable if what you “are looking for is the as-yet unspeakable, the as-yet unspoken”. ...

(....)

I don’t think that in the English language we possess a good vocabulary for talking about the pleasures of readerly discomfort and difficulty: the feeling that one part of ourselves leaps ahead while another part lags behind. In our current moment, the metaphors we use to evoke literary critique as opposed to reading for pleasure are quite distinct: the former is “digging down” or “standing back” (Felski 7); the latter is captivation, transport, immersion. In the former the reader is in control. In the latter the text acts upon the reader. But, most often, I find that the reading experiences I’ve most relished in the academy are not accurately captured by either set of metaphors; the most interesting reading experiences, are, rather, ones in which agency is at once exercised and abdicated.

...(more)

_______________________

Mountain Atelier

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

c.1937

_______________________

Interview with Cristina Burneo

An interview in Spanish and English about literary Ecuador and the bilingual poet Alfredo Gangotena

asymptote

(....)

It’s very important that we have wanted to keep translating Gangotena. Without translation there’s no revision, or culture, or the option of doubting the official versions of history and literature. Today, I wonder how it is that standard image of the hard, masculine, and committed intellectual excludes other figures, like that of Alfredo Gangotena. For that reason, translating his poetry also requires us to question our own ideas about Ecuadorian culture, ideas that require us to perform our nationality and our intellectual lives in the prescribed way. Gangotena, to a great extent, resisted that obligation.

(....)

I don’t think it’s a matter of simply translating from French to Spanish. It involves translating Gangotena’s language, constructed over the base of French. Attachments, the experiences of exile, and the divisions that we live through can come to weaken the idea that we have of a fixed and permanent mother tongue. In certain moments, Gangotena appropriates the French language with such determination, and he loves writing from Paris so much, that in those moments French becomes his first language. Mother tongues can also be exiled when we live other forms of exile and a bilingual existence, and sometimes they are even voluntary exiles, like Gangotena when he is writing in French. When he comes back to Spanish, it still involves a language that is distinct to him, but written in Spanish. This should also allow us to question these categories we have become accustomed to, like “native language.”

...(more)

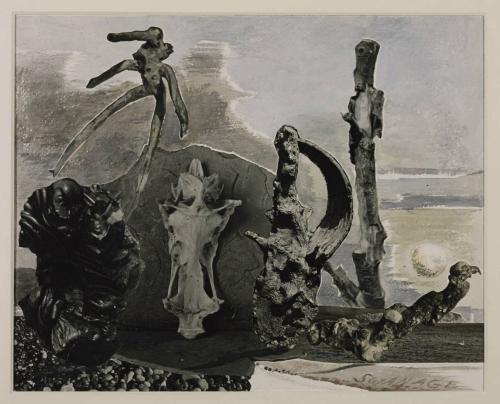

Objets dans la forêt

Alberto Savinio

1928

featured at the much missed Giornale Nuovo

_______________________

Evening Will Come: Issue 53 - May 2015

Canadian Feature

edited by rob mclennan

... poetic statements by derek beaulieu, Amanda Earl, Helen Hajnoczky, Peter Jaeger, Gil McElroy, Erín Moure, Nikki Reimer, Natalie Simpson and lary timewell

Sometimes I wonder what came first:My love of language, or my need to hide behind it? Gil McElroy

(....)

So there’s nothing extraordinary about being a poet. There is, on the other hand, something extraordinary about the poem, living, breathing, walking & talking all on its own. Yes, of course I’m somewhere out back there behind it (& really,I’m not hiding there – I’m just staying out of the poem’s way). In his book Scratching the Beat Surface, Michael McClure comments on Charles Olson’s monumental poem “The Kingfisher,” saying that “I am more impressed with the poem than with what it means.”

My poetics, then: synonymous with “my” poem.

It is a poem.

So Careful to Write

For Christina

So careful to write, of telling people, of making cruelties beautiful

It is not in diminishment

Some notions do much better to prevent breaking out in rabbles

There is more than just one malignant shape in a place so organized

There could be stuff about mushrooms, about the enormous weight of fantasy, about the foods of deprivation

There could be wild, romantic spaces

Or our jargon – it could be stupid

These here books, well, they could get it all wrong, & then, voila!

This could all be a perfectly reasonable way to total ruin.

Given a society of writes and wrongs, insights can be plausibly surmised

We were threats from the very beginning. Samples of the day were made. Systems were framed. A number were made up, even

We think the ones we have are ample

There was some status within our utterances, in the head-turning of our tongues

We liked to clock stable forms all atick with kinds of time

We could have had variants. We could have, you know

We preferred lazier truths within which we connected

...(more)

.....................................................

Gil McElroy’s cartography

rob mclennan

jacket2

(....)

Anyone with any passing knowledge of McElroy’s poetry would certainly begin to notice a series of patterns, from the extended sequences, the abstract punctuations of time and geography, to poems on comets, constellations and other cosmic bodies. Also, there’s his ongoing sequence, akin to bpNichol’s mantra of the “poem as long as a life,” “Some Julian Days,” that weaves itself through the length and breadth of each of his trade collections. The sequence exists as an ongoing series of poems in a “day book” style utilizing the days of the Julian Calendar. It would seem as though, for McElroy, the concept of the “day book” is firmly placed within the abstract, given the unfamiliarity most readers would have with the system, and instead, each poem suggests a timeless quality, holding in all moments concurrently.

...(more)

Poetic Quanta and the Terrestrial Residue of Gil McElroy

Garry Thomas Morse

seven questions for Gil McElroy

touch the donkey

Poetic Quanta and the Terrestrial Residue of Gil McElroy

Garry Thomas Morse

An Interview with Gil McElroy

by rob mclennan

drunken boat

Gil McElroy at Talonbooks

Seven poems

Gil McElroy

jacket

_______________________

Atlas

1927

Alberto Savinio

d. May 5, 1952

_______________________

In Conversation: George Henson

translator of Sergio Pitol's "The Art of Flight"

asymptote

(....)

Vicente Huidobro, who was the founder of creacionismo, in his “Arte poética” said that the poet is a “pequeño Dios,” a “little God.” So, yes, like the poet, the translator is creative in the sense that he or she “creates” a text; but “creative” can also mean “imaginative.” Benjamin talks about the “Aufgabe,” the “job, duty, task’” of the translator; at times, that task requires that the translator be creative in how he or she solves translation problems or challenges. But I believe that translation should be at the service of the original text. As a translator, then, I can be no more creative than the author I am translating, but neither can I be any less.

(....)

I found your translation of The Art of Flight quite exceptional. You skilfully captured Pitol’s humour, self-doubt, and emotional fragility, in addition to his clear confidence as a critic. Is he as engaging to translate as to read?

First, thank you. I am filled with self-doubt. I am very hard on myself, so your words are like a tonic for me. I worked very hard at doing his prose justice. The short answer is, yes, this book was very challenging, which is perhaps one of the reasons it had not been translated. It’s written in many styles, registers, and voices. There’s lots of intertextuality, extensive quotations (often with little attribution), oblique, obscure, and arcane literary references. I wanted to be faithful to Pitol’s prose and his vocabulary, which at times borders on baroque and recondite. Many times, I would Google a phrase or a word pair (adjective/noun) to find that the only person who had used the phrase or pair was Pitol. This required that the English be as original as the Spanish. Pitol pushes the limits of language, which meant I had to do the same. I had to do lots of reading and research. I grew both as a humanist and student of literature, and hope I did him justice.

...(more)

_______________________

The Art of Flight

Sergio Pitol

trans. George Henson

reviewed by Rosie Clarke

(....)

Despite the literary essays and deep readings contained within The Art of Flight, what ties the book together is the glittering thread of himself that Pitol has sewn thoughtfully throughout. Although we meet him as a grown man, it is when recollecting his youth that Pitol seems most vulnerable, and consequently most open to identification. When triggered by the memory uncovered through hypnotherapy, realizing, “many things had become coherent and explainable: everything in my life had been nothing more than a perpetual flight,” it becomes clear for both Pitol and the reader that, while his mother’s drowning may have cast darkness over his life strong enough to hide the memory for decades, once exposed it reveals what he has been running away from for so long, and allows him to stop and take stock of his life.

Although this revelation lends a subtly melancholic undertone, the overall sense is not one of gloom but of vibrancy and vigor; Pitol describes the book as “an attempt to allay anxieties and cauterize wounds,” and indeed the overall feeling is celebratory, of a life fully lived. While disappointing that Pitol’s fiction currently remains unavailable in English translation, Deep Vellum is scheduled to publish the two subsequent volumes of this collection, which will hopefully serve as impetus for further translation of his work. The Art of Flight is rich with Pitol’s impassioned interrogations of others, woven into an intricate, if convoluted, web with memories, anecdotes, and confessions. Not all writers make great critics, nor the converse, but in Pitol’s case, one cannot exist without the other; to quote Borges, “we are all the past, we are our blood, we are the people we have seen die, we are the books that have made us better, we are gratefully the others.”

...(more)

_______________________

Le Matelot

Alberto Savinio

1927

_______________________

From the Anthropocene to the Neo-Cybernetic Underground.

A conversation with Erich Hörl.

with Paul Feigelfeld

(....)

We need a radical artistic, philosophic and historic approach like this to oppose the recurring oblivion of environmentality in the form of pragmatist neoliberal concepts of ecology and a simple economization and institutionalizatio of ecology. We must ask about its scope, challenge and explosiveness, again and again. If the Anthropocene is supposed to be a critical concept, it must result in a discussion of a comprehensive environmentality: the ecologization of thinking and the mind, of subjectivity, desire, power, affects and so on.

(....)

If we don’t want to completely drown in cybernetic capitalism, if the ongoing hyper industrialization and the contemporary psycho power do not colonize everything and lead it towards a complete enshrinement of Being – and there are moments when I do gravitate towards this kind of alarmism -, then I can imagine that technology and art together will advance the process of the ecologization of Being. Art and philosophy, particularly media theory, have to work through the decay of the anthropocenic illusion, and precisely not against technology, but on eye level with the contemporary technological, techno-ecological condition. Félix Guattari bet on the setting free of creativity through new media technologies in the late 1980s and early 1990s and confidently looked forward to the emergence of a new paradigm, which he called the “aesthetic paradigm”. Even though the cybernetic capitalist development has undoubtedly caught up to Guattari’s vision and especially the creative has become completely industrially exploited, I do see a certain potential there today: a radical theoretical artistic experimentation with (media) technologies still is the best form of appropriation and exploration and we cannot let anybody forbid us from doing that. I dream of a neo-cybernetic underground which grows to be the germ cell of a general ecological practice, which does not let itself be dictated the meaning of the ecologic and of technology, neither by governments, nor by industries.

...(more)

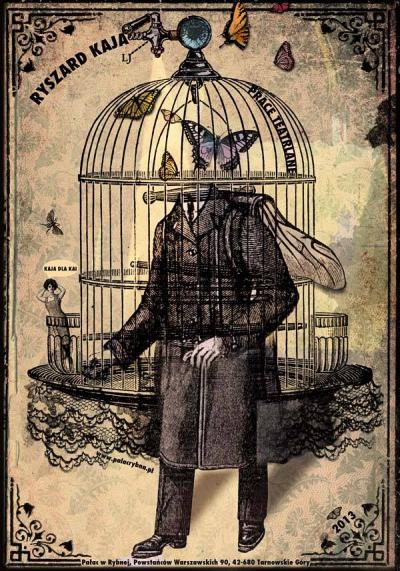

#60

via Deterritorial Investigations Unit

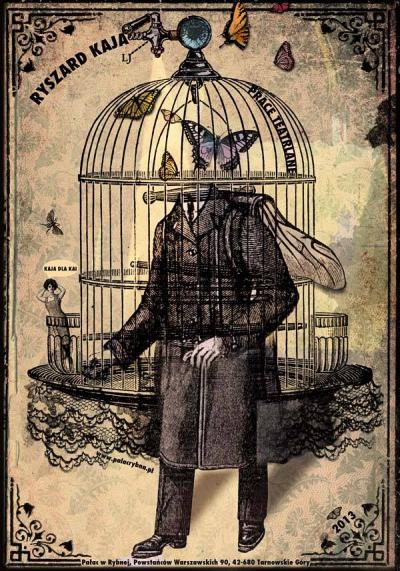

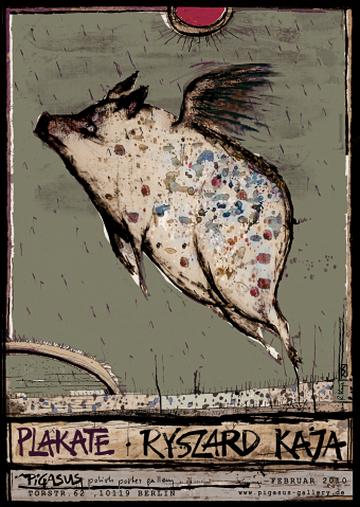

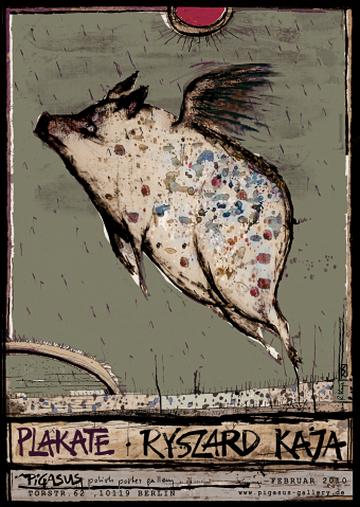

Ryszard Kaja

_______________________

The Living Diffractions of Matter and Text:

Narrative Agency, Strategic Anthropomorphism, and how Interpretation Works

Serenella Iovino

Abstract:

In the past years, the agentic and semiotic properties of material reality have been the focus of many areas of research, producing an exuberant “turn to the material” also in the debate about the humanities. This “material turn” is indeed a broad conversation across disciplines, combining physics and sociology, biology and anthropology, ontology and epistemology, feminist theories, archaeology, and geography, just to name a few. The paradigm emerging from this debate prompts not only fresh nonanthropocentric vistas, but also possible “ways of understanding the agency, significance, and ongoing transformative power of the world – ways that account for myriad […] phenomena that are material, discursive, human, more-than-human, corporeal and technological”. The underlying task of this discourse is that of providing an onto-epistemological framework for non-dichotomous modes to analyze language and reality, human and nonhuman life, matter and mind, nature and culture.

A crossroad of scientific and humanistic research by definition, the environmental humanities is the field in which this “turn” received foremost attention. Ecocritical theory responds to this conceptual conversation by heeding material dynamics via an enlargement of its hermeneutical field of application. A material ecocriticism, in other words, investigates matter both in texts and as a text, elaborating a reflection on the way “bodily natures and discursive forces express their interaction whether in representations or in their concrete reality”. Drawing from the philosophical and scientific insights of the new materialisms, this essay explores the main points of material ecocriticism, focusing in particular on the notion of “narrative agency” and on the way interpreting “stories of matter” becomes possible as an ecocritical practice.

_______________________

Still Life. Dishes

1920

Amédée Ozenfant

(15 April 1886 – 4 May 1966)

_______________________

MAP

Collected and Last Poems

By Wislawa Szymborska

Translated by Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Baranczak

reviewed by Richard Lourie

The mass of men may “lead lives of quiet desperation,” as Thoreau wrote, but the Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska (1923-2012) did just the opposite: She lived a life of quiet amazement, reflected in poems that are both plain-spoken and luminous. Many of them are gathered now in “Map: Collected and Last Poems.”

(....)

Ultimately, in Szymborska’s view of the world, astonishment is not some precious poetic stance, but the only sane and natural response to the onrush of life that is forever various and new. It leaves no time to rehearse; every night is opening night. “Ill-prepared for the privilege of living, / I can barely keep up with the pace that the action demands. / ... The props are surprisingly precise.... / And whatever I do / will become forever what I’ve done.”

There should be some Nobel-like prize for translators — for, without their work, how would we know Tolstoy, Kafka, García Márquez, the Bible? If there were such a prize, Szymborska’s translators Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh would have been awarded it at once. Cast your eye back up on any line quoted here. Every one seems to have been born in English.

I’m told it was the brilliance of her English — and Swedish — translators that helped win Szymborska the 1996 Nobel Prize in Literature. She hated fame’s commotion. She skipped important events and gave one of the shortest acceptance speeches ever, though in it she managed to chide Ecclesiastes for saying there was nothing new under the sun. The press began calling her the Greta Garbo of world poetry, but it wasn’t aloofness that motivated Szymborska’s withdrawal. Rather, it was the need to shield her sense of amazement from the paparazzi, the fans, the parasites of celebrity culture and all those others who lead lives of noisy desperation.

...(more)

_______________________

Ryszard Kaja

_______________________

Cognitive Mapping

McKenzie Wark reviews Alberto Toscano and Jeff Kinkle's, Cartographies of the Absolute

Public Seminar Commons

(....)

The project of Alberto Toscano and Jeff Kinkle’s, Cartographies of the Absolute (Zero Books 2015) is to ask what a Marxist aesthetic might be that tries to map the social totality. It is an excellent inventory of such attempts, across a range of media and art forms. I think there are still some problems with it, but I’ll come to that after outlining the excellent work the book manages to do.

‘Mapping’ gets a bit of a bad rap these days, as certain kinds of mapping are without question tools of conquest and control. So one should think of mapping at least with a certain caution. But perhaps there are alternative ways of mapping, or different kinds of agent for whom the map create agency. Besides, maps have complicated relations to territories, as any Australian student of cartography knows. The ‘map’ of the antipodes preceded the territory. It was ‘found’ in part because in the cartographic imagination it was already there.

(....)

Cognitive mapping is still caught up in a dialectic of essence and appearances, where the phenomenal form of capital is supposed to be captured in aesthetic form in such a way as to reveal its essence, which was known in advance to theory. Aesthetics just gets to be the linkage between the ruling conceptual work and the problem of mobilizing people to action based on their ability to grasp what they need to do. Somehow this never quite works out.

T+K try to restore the honor of critical theory by appeal to Benjamin, for whom the very separation of the panorama form the world is, dialectically, the condition of possibility of its overview.

But as T+K point out, this is satisfying on a literary level only. It is likely more progress can be made by abandoning the contemplative world of the spectator, and engaging with the way organizing practices and organizing worldviews form a unity. It is not that one has to see the whole first, before acting. It is that seeing and acting, while never mapping neatly onto one another, nevertheless advance – and retreat – together. The world is not waiting for us to make a total work of art about a total theory before deciding to go back to the work of making itself again – in our image.

T+K assemble an impressive range of works with which to think about such problems. ......(more)

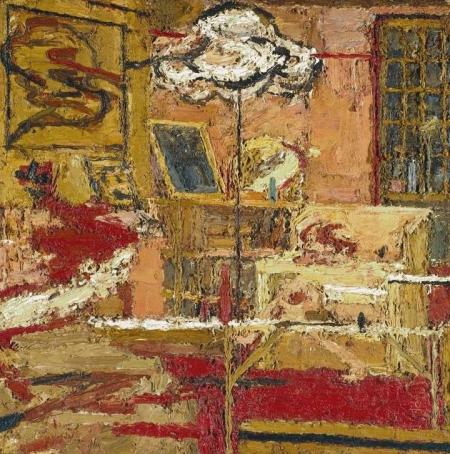

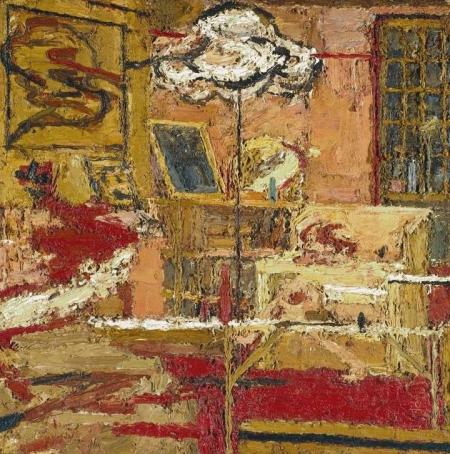

The Sitting Room

1964

Frank Auerbach

b. April 29, 1931

_______________________

After After Nature

Ann Lauterbach

conjunctions

1.

The unsaid strafes its enclosure.

I’m in a store, a storage,

among forgettings that anchor them.

The pasture is all snow and its perceptions

drain the day

outward

onto a disheveled, reckless halo

unspun from a saint’s hair

as if scribbled.

The withheld stares

back onto its insolent intention, some girl

in the bridal threshold of a museum

her white shoulders

readied for sculpture and for the thin fingers

of her groom. Tidy these ancient portals,

says the Bergsonian moon, there’s more

to see of the great murals

whose scansion is blocked

by the banquet’s black plumes and

crimson napkins, fake beads of hanging ice.

(....)

5.

We settle for stone

even as it attracts disaster

just at the welcoming hour.

Now the exposed branches

have turned

yellow, their threads crawling

out from the scripted scene.

Arendt talks about metaphor

enthusiastically; she honors

the sign of what she calls

invisibles,

that which will never attach itself

to thingness. The philosopher’s

wonder is fraught; words charge

our love with action

and action blurs syntax. She thinks

we can see what we hear

just as it vanishes.

The chickadees orchestrate

the silence of the hawk’s

swerve; all is readied for accounting

as for abstraction.

...(more)

Ann Lauterbach at the Poetry Foundation and EPC

_______________________

animation by Piotr Dumala

Four Franz Kafka Animations

Animated Shorts from Poland, Japan, Russia & Canada

open culture

_______________________

The Acquisitive Gaze

Rob Horning

(....)

Pinterest has emerged as a para-retailing apparatus for “social shopping,” in which users add value for retailers by organizing consumer desire into various moods and themes on boards. Some users have been able to earn commissions through this work, but Pinterest has moved to suppress third-party marketing links in advance of its “buy button,” which will reserve commissions for that platform itself.

(....)

... it’s not that Pinterest prohibits self-expression; it limits self-expression to the surface of found images, which are organized and deployed to convey one’s aspirations or moods or desires or ingenuity. This mirrors the processes of consumerism generally, in which mass-market products are bought and consumed not merely for their use value but for what they can be seen to be saying about the sort of person you want to seem to be. Vast ideological apparatuses are employed to teach us how to read out of images the various characteristics and attributes and traits (“beauty,” “cool,” “fashionability,” “cleanliness,” “health,” etc.) we seek to embody ourselves.

...(more)

_______________________

Empire Cinema

Frank Auerbach

_______________________

New Winnipeg Poets Folio

edited by Jonathan Ball

lemon hound

Four Poems

Maurice Mierau

Fred Engels And My Teenage Uncle In Different Fields, At Different Times

Maurice Mierau

(....)

Does she know when he clutches for her at night

that history is a snow goddess

who walks on corpses in a red, red field?

*

Before the fall of bourgeois snow, he feels

bored, puts his hand into her cleft.

They drink Château Margaux all night.

The bottle open on her lap, she seals

his reach with just one kiss. The left’s tedious

scruples do not bother him in the dark.

This sleeping French girl knows nothing

about him—lying splayed in the field

he sees the snow left purple with the dye

of the cotton mills belching at night.

The reactionary victims would not know

even after the melt that dialectical

materialism was a field whose crop

only grew at night. For example

my uncle knew they buried all the bodies after dark,

after ’45. He’d never tasted Château Margaux

or considered the angel of history.

Digging was hard too in Siberia, in frozen

earth. My uncle used a blowtorch

to warm the grave. He had trained as a mechanic.

Now he fixed a simpler problem—

open heat on permafrost.

...(more)

_______________________

Shell Building Site: from the Thames

Frank Auerbach

_______________________

His English: Ann Kjellberg on Brodsky’s self-translations

(....)

By his death in 1996 he had translated many of his own poems into English, a language in which he had by then taught and written for nearly half his life. Coming from the hand of their author, these works fall somewhere between wholly subsidiary translation and original creation. Whether their language is poetically autonomous or too distortingly shaped by its Russian consanguinities has been debated since Brodsky first spoke up in the literary culture of his adoptive land.

For Brodsky, the musical dimension of a poem was inextricably wound into its semantic heart: the forms had coloration and value, as keys do for composers and tints for painters. He often spoke of the greyness or monotony of certain feet (the amphibrach, for instance) as an antidote to poetic grandstanding: such plays of self-effacement against assertion are very important in his work. Rhyming and metrical problem-solving are also essential to the wit of his poems, which again inflects poetic authority with impishness and deeply colors the poems’ tone. He used the pacing of poetic forms contrapuntally against the plotting and logic of his poems. The forms themselves—their shading, their pathos, their modulation of energy, their inherent proportionality—were absolutely inseparable for him from the poems and from his practice as a poet.

(....)

... the legacy of that period of formal quiescence remains very much with us. Few American readers can read verse musically with any sophistication. The notion is still widespread that there is a binary division between “formal” and “free” verse—whereas much of the best of what is read as free verse is in fact deeply colored by forms (often shadows of iambic pentameter or echoes of the syllabic lines of Moore and Bishop), and there is a big difference, for example, between verse that follows a colloquial or spoken line and verse that treats language as a found object. Similarly, “formal” poetry is not just conservative poetry that adheres to old structures, but is an evolving medium that grows and develops and constantly makes new means available to the artist. The rhymes and meters of Muldoon alone should be sufficient to make the case that form can be modern.

Brodsky’s effort to enliven and expand the formal repertoire in English, which met with considerable resistance at the time, can surely now be judged a success. Yet critics continue to argue that the specific musicality of Brodsky’s English verse is too infected by “foreignness.” I think this suggestion deserves more scrutiny. ...(more)

|