|

Scrittore a macchina

1918

Ottone Rosai

b. April 28, 1895

_______________________

We ought perhaps to admire a book deliberately deprived of all resources, one that accepts beginning at that point where no continuation is possible, obstinately clings to it, without trickery, without subterfuge, and conveys the same discontinuous movement, the progress of what never goes forward. But that is still the point of view of the detached reader, who calmly considers what seems to him an amazing feat. There is nothing admirable in an ordeal from which one cannot extricate oneself, nothing that deserves admiration in the fact of being trapped and turning in circles in a space that one can't leave, even by death, since to be in this space in the first place, one had precisely to have fallen outside of life. Aesthetic feelings are no longer appropriate here. We may be in the presence not of a book but rather something much more than a book: the pure approach of the impulse from which all books come, of that original point where the work is lost, which always ruins the work, which restores the endless pointlessness in it, but with which it must also maintain a relationship that is always beginning again, under the risk of being nothing.

Blanchot on Beckett's The Unnameable, from The Book to Come

posted at Spurious

_______________________

Translating André Breton: Robert Duncan & David Antin

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

Dreams

translated by Robert Duncan

But the light returns

the pleasure of smoking

The spider-fairy of the cinders in points of blue and red

is never content with her mansions of Mozart.

The wound heals everything uses its ingenuity to make itself

recognized I speak and beneath your face the cone of shadow

turns which from the depths of the sea has calld the pearls

the eyelids, the lips, inhale the day

the arena empties itself

one of the birds in flying away

did not think to forget the straw and the thread

hardly has a crowd thought it fit to stir

when the arrow flies

a star nothing but a star lost in the fur of the night

...(more)

_______________________

Ottone Rosai

_______________________

Precarious Existence and Capitalism: A Permanent State of Exception

Tayyab Mahmud

Abstract:

The contemporary neoliberal era is marked by an exponential expansion of contingent and precarious labor markets. In this context, the construct of precarity emerged to signify labor conditions of permanent insecurity and precariousness. Coming at the heels of the era of Keynesian welfare, precarity is mostly seen as an exception to the normal trajectory of capitalist formations. The basic argument of this paper is that under capitalism, for the working classes precarious existence is the norm rather than the exception. Precarity is the outcome not only of insecurities of labor markets but also of capital’s capture and colonization of life within and beyond the workplace. Commodification, the primary logic of capitalism, unavoidably engenders destruction, disruption, dislocation, insecurity, vulnerability, susceptibility to injury and exploitation. For non-capital-owning classes, precarious existence, both as condition of labor and as ontological experience, is the natural and enduring result. Precarity, like capitalism, unfolds on different spatial, temporal and embodied registers differentially. Consequently, the scope and quantum of precarity engendered by capitalism varies across space and time. This differential and variation result from differing levels of commodification, exploitation and colonization of life by capital. While precarity is an unavoidable historical and structural feature of capitalism, neoliberalism has expanded and deepened it. Along the scale of precarity in the era of neoliberal globalization, undocumented immigrant labor represents the condition of hyper-precarity.

_______________________

Badiou on Speculative Realism

(....)

... The idea of Quentin Meillassoux is practically that all philosophical tradition is in the space of Kant, the sense that correlationism is the only clear answer to the question of Hume. The idea of Quentin Meillassoux is that there is another possibility. We are not committed to the choice between Kant and Hume.

My project is different in that it investigates different forms of knowing and action outside empirical and transcendental norms. My vision, however, is also that we must escape two correlationisms and it is a question of the destiny of philosophy itself. In the last century we had two ends of philosophy the analytic (focusing on logic, sense and science) as a kind of new positivism. The other end was phenomenological with Heidegger. There is a strange alliance between the two in France particularly in terms of religious phenomenology (Marion, Ricour, Henry) and cognitivist analytics. They join together against French Philosophy since, as they say, the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Against this the fundamental affirmation of SR is an ambitious point of view, a new possibility for philosophy. A new vision. Philosophy can continue. In this sense I am happy that it is not merely a continuation of classical metaphysics nor an end of it. In this sense I am in agreement with the word realism. We are beyond the end of metaphysics and classical metaphysics with the term realism. The question of realism as opposed to materialism is not a crucial question today. What is important is that it is not correlationist or idealist. It is a new space for philosophy, one with many internal differences but this is a positive symptom.

...(more)

via Agent Swarm

_______________________

Ottone Rosai

_______________________

The Miniaturist

(Paris, 1871)

Anthony Cirilo

1

Enclosed is my winter my hurt my cloud they would have no more of me

if the rebels win and the fighting is pitched in the streets horrific this morning

I saw a woman pull a cannon like a mule les communards are melting

silverware for bullets I think this war will be fought fork over knife and the hungry

will have to eat the sky I forget myself enclosed is a house for Emile you said

he has outgrown your arms he takes no mind to tennis or piano no sport in shooting

game let him have this then I’ve had no paper or ink so I stay awake

a long while remembering the house last spring and my body betrays me its noises

...(more)

Drunken Boat 21

_______________________

Émile Bernard

b. April 28,1868

Alan Reynolds

b. April 27, 1926

_______________________

The Moon Upoon The Waters

Tom Raworth

for Gordon Brotherston

the green of days : the chimneys

alone : the green of days and the women

the whistle : the green of days : the feel of my nails

the whistle of me entering the poem through the chimneys

plural : i flow from the (each) fireplaces

the green of days : i barely reach the sill

the women’s flecked nails : the definite article

i remove i and a colon from two lines above

the green of days barely reach the sill

i remove es from ices keep another i put the c here

the green of days barely reaches the sill

the beachball : dreaming ‘the’ dream

the dreamball we dance on the beach

As When: A Selection by Tom Raworth

published this month by Carcanet

_______________________

Alan Reynolds

_______________________

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s ‘My Struggle: Book 4’

Jeffrey Eugenides

(....)

Knausgaard doesn’t reveal the identity of the American writer he had lunch with. But I will: It was me. I may be the first reviewer of Knausgaard’s autobiographical works who has appeared in one of them. Therefore, I’m in a perfect position to judge how he uses the stuff of his life to fashion his stories. Ever since Knausgaard turned me into a minor character, I have an inside track on what he’s doing.

(....)

The reason these books feel so much like life is that there’s only one main character. For all of his gifts, Knausgaard never leaves an indelible impression of other people. I have only a limited sense of his father and mother despite having read hundreds of pages about them, and the figures Knausgaard meets in Hafjord, his teaching colleagues, the girls he falls for and his students, tend to merge. You never get inside these people. It’s impossible to be inside them without altering the focus of Knausgaard’s solipsism. This wouldn’t work with most writers. They wouldn’t be interesting enough, tormented enough, smart, noble, pitiless or self-critical enough. With Knausgaard the trade-off is more than worth it. His is such an interesting brain to inhabit that you never wish to relinquish the perspective any more than, in your own life, you wish to stop being yourself. One of the paradoxes of Knausgaard’s work is that in dwelling so intensely on his own memories he restores — and I would almost say blesses — the reader’s own.

...(more)

_______________________

Alan Reynolds

_______________________

from Where the words end and my body begins

Amber Dawn

lemon hound

(....)

Depression, the word, is useless. There’s no music

no romance, no reclaiming it. Neither word nor illness

can be made into bedroom play. Comedy, maybe?

“So a guy walks into a bar…I mean the ER,

no I mean a bar … no I mean ER.” Same difference.

Divorced from the root

depression divvies, clinically scores me

into that and this and this and this.

But sadness is bigger than my last relapse.

This sadness is bigger than B vitamins,

is bigger than the SAD lamp that brightens my desk.

Bigger than ten milligrams twice a day.

Sadness holds more than all the second-

hand coffee mugs at an AL-ANON meeting

takes more time than the self-help

workbook my poetics professor gifted me

longer than the long-distance collect call

my mother refused to accept.

Too urgent to be wait-listed, it

is not interested in working around a schedule, or

another referral from the Red Book.

...(more)

_______________________

Alan Reynolds

_______________________

Potentiality or Capacity? Agamben's Missing Subjects

Nina Power

(....)Just as it is altogether too quick to see the "material affirmation of liberation" in the exploitation

of basic human capacities in work, it is altogether too slow to see in the obstinacy of a Bartleby

the only response to sovereign domination. Agamben plays a central role in this recent

"minimizing" turn, turning to an older Aristotelian concept of "potentiality" to explore, albeit

paradoxically, the primacy of inactivity. In his discussion of Bartleby, he notes: "Our ethical

tradition has often sought to avoid the problem of potentiality by reducing it to the terms of will and

necessity… Bartleby is capable only without wanting." Agamben shares Heidegger's distaste for

'activity' and "will," deeming such concepts insuperably metaphysical. He thus demeans,

unintentionally perhaps, the real forces at work in labor; Hardt and Negri, on the other hand, see

all too clearly the politically productive elements of labor but miss crucial steps and antagonisms

in the relation between production and emancipation. In the case of Hardt and Negri, this is

perhaps a consequence of their affirmative ontology which sees potential everywhere. Agamben's

paradoxical treatments of potentiality, on the other hand, seem to leave room only for reduced or

promissory subjects. "The messianic concept of the remnant" may well permit "more than one

analogy to be made with the Marxian proletariat" but only as "the unredeemable that makes

salvation possible," the part "with all due respect to those who govern us" that "never allows us to

be reduced to a majority or a minority." There are other, far less deferential ways of conceiving of

political opposition - do we need to say that all activity is necessarily metaphysical? Agamben's

Aristotelian conception of potentiality entails, in the highest instance, "that potentiality

constitutively be the potentiality not to (do or be)," which suggests that even if potential is realized,

it is realized only by its lack of activity. Agamben may see parallels between this lack of activity

and the class that exhibits the "total loss of humanity," but the "redemption" that Marx and

Agamben see must be understood quite differently. "Redemption" for the early Marx is the

simultaneous supersession of private property coupled with the recovery of humanity; it is not the

paradox of being saved "in being unsavable" as Agamben concludes his discussion of man and

animal in The Open. (....)

Academia.edu

.....................................................

"The Spectacle Looks Back into You: The Situationists and the Aporias of the Left"

John Clark

Imre Kinszki

1901 - 1945

_______________________

"New distance permits new questions. What was Canadian literature? How did it work? What did it mean? And what does it continue to mean for those of us who are Canadian and who write?"

What Was Canadian Literature?Stephen Marche on the Decline and Fall of a National Experiment partisan

2014 was a year of deaths and victories for Canadian literature. Alice Munro accepted the Nobel Prize for literature and promptly retired. Mavis Gallant left her Canadian body in Montparnasse cemetery, triumphantly empty of stories. A seventy-fifth birthday party for Margaret Atwood at the Four Seasons came complete with a guard of forty authors to toast her. In 2014 as well, the Canada Council hosted a National Forum on the Literary Arts, intended to address the future of literature in Canada, which broke down into “a 250-person choir in simultaneous competition to be the lone soloist” and “nothing short of a total goddamn clusterfuck,” in the memorable phrasing of Pasha Malla. It was a year with a sense of an ending, at least for Canadian literature.

Writing in Canada meanwhile continued its blessed existence. Anyone who whines about being a writer in Canada today needs a history lesson and a long vacation. It’s not just the peace and prosperity which we take so utterly for granted. Before the 1960s, Northrop Frye could describe the entire literary production of the country in a few pages in annual reports for the University of Toronto magazine, and sometimes his conclusions were as terse as “this is clearly not a banner year for Canadian poetry.”

(....)

There is no question that we are living in a great time to be a Canadian writer, perhaps the best ever. But at the same time the sense of writing as a national project is stuttering to its final end.

There is no question that we are living in a great time to be a Canadian writer, perhaps the best ever. But at the same time the sense of writing as a national project is stuttering to its final end. There is one major Canadian-owned publisher still standing, Anansi; even McClelland and Stewart belongs to the Germans. The CBC, the handmaiden to Canadian literature, is being dissolved in front of our eyes. And the academic study of Canadian literature, like all the humanities, continues its steady decline into underfunded gerontocracy. The question of “national identity” is an antique one; literary nationalism is something your grandparents did, like macramé. American Psycho or American Pastoral brandish their connection to their home country; here, any such connection is best avoided—and not just because you limit your market. Canadian writers are happy to say they’re from Canada; they just don’t want to write about what it might mean. Canadian literature, in the sense of a literature shaped by the Canadian nation and shaping the nation, is over.

...(more)

_______________________

Emi Anrakuji

Untitled [#11225]

from the series O Mapa, 2013.

Emi Anrakuji: Mapping Embodiment

Jonathan Lee

The Space In Between

(....)

What we see here is a striking confirmation of Jerry Thompson’s recent claim that the importance of photography has much to do with epistemology, with its revelation of how we know the world. Elaborating a point made by the 19th-century photographer, William Henry Fox Talbot, Thompson emphasizes that photography gives us “nothing less than a way of knowing the world that transcends our educations, our opinions, our intentions, hopes, and desires—in a word, our subjectivity. Anrakuji’s work reveals a world that includes subjectivity but is neither shaped by nor defined by the human subject.

In this respect, at least, Anrakuji is effectively in dialogue with Takuma Nakahira, who argued as early as 1973 that contemporary history has shown human beings to have no special place in the world, so that “our means of expression at this point in time should discard ‘the image,’ and address the world as it is, and rightly position the thing as the thing and myself as myself in this world. To do so, all humanizing or emotionalizing of the world according to the self must be rejected.” In a later essay, “Self-Change in the Act of Shooting,” Nakahira would insist that “when I encounter afresh the world of reality, my own self-consciousness is dismantled; the act of rebuilding the consciousness has been imposed on me endlessly. That, in a way, has been my fate as a photographer.” This fate of rebuilding a dismantled subjectivity, I now want to suggest, also governs the work of Emi Anrakuji.

...(more)

_______________________

Emi Anrakuji

_______________________

Are Animals People?

Michael LaBossiere

Talking Philosophy

(....)

There are at least three type of personhood: legal personhood, metaphysical personhood and moral personhood. Legal personhood is the easiest of the three. While it would seem reasonable to expect some sort of rational foundation for claims of legal personhood, it is really just a matter of how the relevant laws define “personhood.” For example, in the United States corporations are people while animals and fetuses are not. There have been numerous attempts by opponents of abortion to give fetuses the status of legal persons. There have even been some attempts to make animals into legal persons.

Since corporations are legal persons, it hardly seems absurd to make animals into legal people. After all, higher animals are certainly closer to human persons than are corporate persons. These animals can think, feel and suffer—things that actual people do but corporate people cannot. So, if it is not absurd for Hobby Lobby to be a legal person, it is not absurd for my husky to be a legal person. Or perhaps I should just incorporate my husky and thus create a person.

It could be countered that although animals do have qualities that make them worthy of legal protection, there is no need to make them into legal persons. After all, this would create numerous problems. For example, if animals were legal people, they could no longer be owned, bought or sold. Because, with the inconsistent exception of corporate people, people cannot be legally bought, sold or owned.

Since I am a philosopher rather than a lawyer, my own view is that legal personhood should rest on moral or metaphysical personhood. I will leave the legal bickering to the lawyers, since that is what they are paid to do.

...(more)

via Leon Niemoczynski

_______________________

Sin título

1957

Mark Tobey

d. April 24, 1976

_______________________

Death and Self in the Incomprehensible Zhuangzi

Eric Schwitzgebel

in draft

The ancient Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi defies interpretation. This is an inextricable part of the beauty and power of his work. The text – by which I mean the “Inner Chapters” of the text traditionally attributed to him, the authentic core of the book – is incomprehensible as a whole. It consists of shards, in a distinctive voice – a voice distinctive enough that its absence is plain in most or all of the “Outer” and “Miscellaneous” Chapters, and which I will treat as the voice of a single author. Despite repeating imagery, ideas, style, and tone, these shards cannot be pieced together into a self-consistent philosophy. This lack of self-consistency is a positive feature of Zhuangzi. It is part of what makes him the great and unusual philosopher he is, defying reduction and summary.

(....)

One idea that seems to shine through the Inner Chapters, especially Chapter 2, is the inadequacy of philosophical theorizing. Words, Zhuangzi suggests, lack fixed meanings, distinctions fail, and well-intentioned philosophical efforts end up collapsing into logical paradoxes and the conflicting rights and wrongs of the Confucians and the Mohists (esp. p. 11-12).

If Zhuangzi does indeed think that philosophical theorizing is always inadequate to capture the complexity of the world, or at least always inadequate in our small human hands, then he might not wish to put together a text that advances a single philosophical theory. He might choose, instead, to philosophize in a fragmented, shard-like way, expressing a variety of different, conflicting perspectives on the world – perspectives that need not fit together as a coherent whole. He might wish to frustrate, rather than encourage, our attempts to make neat sense of him, inviting us to mature as philosophers not by discovering the proper set of right and wrong views, but rather by offering us his hand as he takes his smiling plunge into wonder and doubt.

That delightfully inconsistent Zhuangzi is the one I love – the Zhuangzi who openly shares his shifting ideas and confusions, rather than the Zhuangzi that most others seem to see, who has some stable, consistent theory underneath that for some reason he chooses not to display in plain language on the surface of the text.

...(more)

_______________________

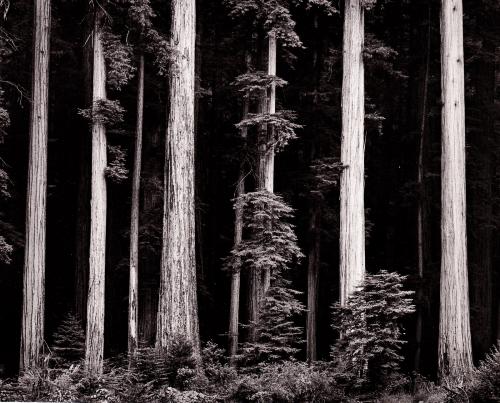

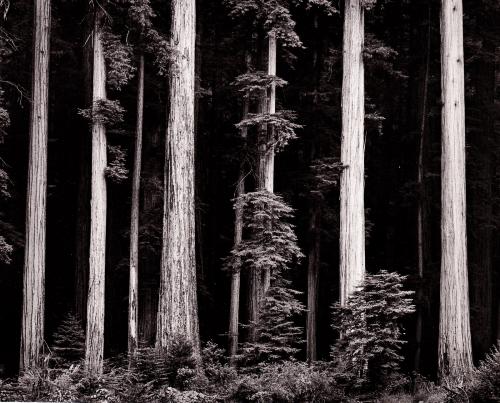

Imre Kinszki

Redwoods

Ansel Adams

d. April 22, 1984

_______________________

from From The Poplars

Cecily Nicholson

lemon hound

_____

endowed by forces of nature, forces such as forest fire

darkened save the plumed out stack

bowed-out steam

system

evaporation microanatomy

adhesion, stumps

of cell walls end-to-end fibre forms

under the niddle of machine

streaming silver-blue roofs

trains below trains above

upper tacking texture lines

cracked floor of a dry river tracks

trace along side

nation majorities

idyllic sense of security

minorities

pauseless

respect

picking berries on the side f the road; an assertion of sovereignty

_____

dead tree standing sunned and whipped dry

firewood lichen curls kindle

tree taken downtown

dragged carcass

across forest floor to blackened pit

dredge spoils

battle, an extreme form of dialogue

pain embraced by a loud river

ideality acts public out of order

wrested, returns

the mill turns around of its own free will

_____

From the Poplars

Cecily Nicholson Talon Books

Review of Cecily Nicholson’s From The Poplars

rob mclennan Small Press Book Review

_______________________

Leaves, Frost, Stump

Ansel Adams

_______________________

'Active solidarity with directly impacted communities'

A conversation with Cecily Nicholson

jacket2

(....)

For the text to be grounded it necessarily contains my everyday life, including paid work and organizing. I prefer poetry that documents, witnesses, reveals structure, talks back and raises questions in ways that are not closed or irrelevant to my friends, family, allies. I’ve learned to reference cultural production with a specific interest in its process and public, and not simply the object/outcome. I relate best to work being produced under hard conditions and in active solidarity with directly impacted communities. If my poetry is relevant to the work of organizing then that’s a fortunate convergence.

Poetry is necessary work for me – I don’t wish for it to be easily absorbed. The use of the cultural front in furthering causes of capital, colonialism and ultimately violence and poverty is difficult to get out from under. This was evident in the olympic moment. The poetry collective I work with are all organizers in different areas. We formed in anticipation of the olympics and choose to publish work that was anonymous and felt free to be moderately (and justly) seditious. In support of various actions we performed individually and collectively. At that time the deliberate influx of capital into arts production was glossing civic and national identity – this happening prior to a period of wider retrenchment of arts funding – the backdrop being long decades of dismantling and disregarding social supports. These issues are at play in the processes of gentrification that continue to be resisted in the downtown eastside of Vancouver and elsewhere.

Relative to the downtown eastside I have a lot of privilege, most significantly as a paid worker, over the years. Now the area is being dominantly constructed as an arts district, so the problematic of cultural capital and producing work from this location is even more fraught. Acknowledging this, Triage is my best attempt so far to speak alongside a community of women in struggle – who are politically astute, resilient organizers and active cultural producers in ways that refuse to be co-opted. My work at DEWC enters into Triage as a jumbled series of narratives and samplings. I wrestle with the language of bureaucracy. In “SERVICE” I consider migration into the core and the daily grind of the service industry in a place that also cares for movements and uprising.

...(more)

_______________________

Roots

1948

Ansel Adams

_______________________

Pale/ontology: The Dinosaurian Critique of Philosophy

Sam Kriss

full stop

(....)

The thing about the repressed is that it always does come back. It’s in a different form, but no number of asteroid impacts can blot out the central law of the psyche. The primal analytic scene is this: a patient, squirming on a couch, saying this and that thing about the problems in her life, trying to avoid the central issue in a constant swerving series of linguistic loops, unavoidably centripetal — suddenly she seizes up. A cough. One hand darts into the air, seized, contorted; already the polished and manicured nails are looking somehow claw-like. When she tries to speak again her mouth opens into a long slit running to the corners of her jaw, revealing the rows of tiny sharp teeth behind. Her face lengthens to a snouty point, her hair frills into soft downy feathers, her ankle travels halfway up her leg. There’s a dinosaur on the couch. Then it speaks — something ultimately quite banal about its parents or its childhood; the point is that it’s something ancestral and inhuman, from the old dark wordless prehistory of the mind. Memory is everywhere a form of bioengineering; the bringing back of a dinosaur.

Faulkner understood it: The past is never dead. It’s not even past. Reintroducing the dinosaurs isn’t a matter of temporal but spatial rearrangement. ...

(....)

Philosophers don’t want to consider dinosaurs because in any epistemology or ontology that follows Kant in featuring a distinction between human experience and the non-human world, dinosaurs represent the ultimate point of the non-human world’s unknowability. God is an indeterminate quantity; the real Absolute Other is twenty-three meters from end to end, with broad flat teeth for slicing up vegetable matter and a long tapering tail that draws lazy circles in the heavy Tithonian air. Levinas and Derrida speak of the unfathomable void of an animal’s eyes, and in a way they’re right; there’s sometimes something briefly terrifying in there. But it’s only a punctum, a sudden pin-prick: we know animals, we see them in the park, we grew up with them in fables and nursery stories. It’s a wound that quickly heals.

Dinosaurs are too big to fit in any of our conceptual categories. If we’re to conceive of a noumenon, a real world as it really is, outside our experience, the previous existence of dinosaurs on the earth is the most important single fact about that world. They stand for the sheer unimportance of human subjectivity: reality was around for millions of years before we arrived to ponder its nature, and it did fine; even without a human subject to give meaning to its objectivity it was still full of life and danger. In this light, the strange refusal to talk about dinosaurs is so pervasive and so consistent that it can only be read as a neurotic symptom. If we don’t discuss them, maybe they won’t come back to claw our fragile distinction from the world of objects into shreds. It’s not just our finely wrought society that the dinosaurs threaten; it’s the idea that human subjectivities and the world beyond them can face each other as two equal halves, evenly matched. It’s the fantasy of an inert world, one without gargantuan teeth. It’s the idea that humans are subjects, always subjects, and always humans.

...(more)

_______________________

Rushing Water, Merced River

Ansel Adams

Irma Haselberger

Irma Haselberger's Photostream

_______________________

Precariousness, Literature, and the Humanities Today

Simon During

.....................................................

A Garden of Wandering: A Response to Simon During

Eileen A. Joy

(....)

Of necessity, ‘academic freedom’ requires peripatetic practices—we can’t be bound any longer to this or that (institutional) place and its increasingly top--down protocols, in terms of developing certain knowledge practices, especially at a time when institutions of higher learning are becoming more and more inhospitable, for faculty and students alike. For many, you just can’t live here any more (perhaps you’ve already been shut out in advance, with graduate degree in hand, massive amounts of debt, and no job), and it’s time to depart, taking this valuable work with us like so many contraband diamonds, while insisting that we will now be ‘rooted in the absence of place’ . It may thus be time to decentralize the Humanities through various para--academic practices, such as has already been accomplished via the Open Access (OA) movement, for example. Here, I take to heart During’s advice to the Humanities to attune and adapt itself to ‘an emergent global social order whose conditions are not under our control’ and to the ‘social and metaphysical precariousness’ that emerges therefrom, but not through literary--historical analysis of that situation only. Rather, I would urge us to actually inhabit that precariousness more fully—to get Outside, stand in the rain, and see what can be done there. I myself resigned a tenured professorship in 2013 in order to run punctum books and the BABEL Working Group full--time—both of these entities exist to work on new modes for knowledge creation, exchange, and dissemination, as well as to ‘build shelters for intellectual vagabonds,’ both within and beyond the University proper. It’s about those of us within the Humanities perhaps attending to things on more structural levels and devoting more of our time to developing new spaces within which the Humanities might flourish in unexpected (and non--traditional) ways, which is different than continuing to either defend or reboot what we do in here.

(....)

So, power has left the streets and buildings and become nomadic (and maybe even post--human), and we—the critics? the interpreters?—may also need to depart, to disappear into the ether, while also squatting in the abandoned real estate (such as the University ), in order to engage in tactical maneuvers that would not amount to critique as much as to creative intervention, even creative scrambling, of the sort discussed by Rita Raley in her book Tactical Media. Here, criticism would become (or morph into) tactical disruptions of ‘dominant semiotic regimes’ as well as ‘the temporary creation of a situation in which signs, messages, and narratives are set into play and critical thinking becomes possible’—especially important in a post-- industrial era where the ‘field of the symbolic’ has become a ‘primary site of power’ (Raley 6).

(....)

Personally, I work on behalf of Derrida’s ‘university without condition,’ which Derrida believed would ‘remain an ultimate place of critical resistance—and more than critical—to all the powers of dogmatic and unjust appropriation,’ and which has special safekeeping by way of the Humanities, entailing the ‘principal right to say everything, whether it be under the heading of fiction and the experimentation of knowledge, and the right to say it publicly, to publish it’. As the University has become more and more inhospitable to the sorts of non-- calculable events of learning ‘without condition,’ we must make our way elsewhere, cultivating alternative and radicant Gardens of Thought.

(....) _______________________

Spring Time in the Dust Bowl

Robert Hariman

BAGnewsNotes

(....)

Both roadway and the lone individual are directed toward the vanishing point of the photograph: a place in this image of pure obliteration. Sight, distinction, every separate thing is consumed by the storm, converted into total meaninglessness like a last, uniform expanse of cosmic dust at the far end of time. Against the hubris that comes with building beautiful structures and complex civilizations, we see instead a trajectory toward a common dissolution.

This photograph doesn’t tell us anything important that we don’t know, but it does provide the means to think about what we would rather ignore. When it comes to living on this planet, just who are we kidding, and what do we think will save us? There have been dust storms for a very long time, and they have buried more than one civilization, but now the stakes are higher still. Human beings are able to alter the climate, but not control it. What had been local problems or long term patterns can be tipped into catastrophic changes. And if hope springs eternal, then there will be reason to believe that one day we’ll all be there, walking along a beautifully engineered roadway into oblivion.

...(more)

_______________________

Rockaway Beach with Pier

1901

Alfred Henry Maurer

b. April 21, 1868

_______________________

Pound’s Metro

A deeper look into In a Station of the Metro

William Logan

(....)

The minor vogue and rapid extinction of Imagism, a movement whose influence we still feel, has been hashed over by literary critics for a century. Its rehearsal here is merely to bring the poem into focus within the slow progress toward the densities of language, the images like copperplate engraving, that made Pound Pound.

(....)

“In a Station of the Metro” is the rare instance of a poem whose drafts, had they survived, might retain the fossil traces of a complete change of manner, from gaslit poeticism to the world of electric lighting and underground rail. “Contemporania” showed Pound’s first acquaintance with the modern age, with the deft gliding of registers, the slither between centuries of diction, that made virtue of vice: “Dawn enters with little feet/ like a gilded Pavlova,” “Like a skein of loose silk blown against a wall/ She walks by the railing of a path in Kensington Gardens,” “Go to the bourgeoise who is dying of her ennuis,/ Go to the women in suburbs.” (In American poetry, it has never hurt to knock the suburbs.) His embrace of the modern is not a rupture with the past (there is antiquarian fussiness enough), but an acknowledgment that the past underlies the present, that present and past live in sharp and troubled relation. “In a Station of the Metro” is the final poem of the group.

...(more)

_______________________

anenomes in a Cornish window

Christopher Wood

_______________________

Vernacularists!

Joe Milutis

Bright arrogance #6

Of the “three grades of evil . . . in the queer world of verbal transmigration,” Nabokov places vernacularism at the lowest circle of Hell. “The third, and worst, degree of turpitude is reached when a masterpiece is planished and patted into such a shape, vilely beautified in such a fashion as to conform to the notions and prejudices of a given public.” In another place, he says that “A schoolboy’s boner mocks the ancient masterpiece less” than work that attempts to create a more “readable” version than the original. Since this column explores, and indeed celebrates versions that are wildly discrepant from the original, we should perhaps forget Nabokov’s contempt, and embrace the vernacularist translator—even espousing the No Fear Shakespeare series and its ilk as a harbinger of fearless literary experimentation to come, in its promise to translate the works of Shakespeare into “the kind of English people actually speak today.”

We need not, however, perhaps go that far. "How many poetic works, reduced to prose, that is, to their simple meaning, become literally nonexistent! They are anatomical specimens, dead birds!" Paul Valéry's plaint echoes the concerns of Joan Retallack; if the popularity of her (much mistranslated) “poethics” is any indication, many are still invested, as was Benjamin, in keeping the poetic “uncommunicative,” or at least formally and syntactically difficult, eluding easy definition. And this would imply a kind constant work of translation at the very core of any poetic project. “In times of rampant fundamentalism complex thought is a political act. . . . the necessarily inefficient, methodically haphazard inquiry characteristic of actually living with ideas.” In other words, egghead shaming and hippy punching get you easy points amongst literary conservatives and presumed populists alike, but that doesn’t make it right (although it does make it kind of right-wing).

However, we could say that there is a brand of translator who takes on the intralingual warping of complexities into “plain speaking,” or navigates the complexity of the plain, as a kind of conceptual challenge. ...(more)

The Ghosts

Disparate number 18

Between 1815 and 1823

Francisco de Goya

_______________________

The Before Unapprehended

Gabriel Blackwell

conjunctions

Somehow, though, this seems awfully familiar.

—

No, I’m not less bothered by his absence than you, brother. How could I be? We were eleven and now we are ten, and yet there is no body, none of us can name the one who’s missing, and what must all of that mean? This silence worries us equally. Or, no, not quite equally: I think we all now agree my verses were next. If anyone should want this lonesome rest to break, it’s me; I mean, if I can’t claim a deeper anguish at brother’s disappearance, I can add to it the anxiety of not knowing what to say. The bodies of our departed brothers will only get heavier the more steps we take, and though we all share that burden, how many steps we all take under it—at least for the moment—is up to me. Glass houses, brother.

—

(....)

I agree: We probably ought to go back to the beginning. At least then we would know where we were. But the first verses escape me. I think I have them right in my mind, but when I try to speak them out loud, my throat dries up and then my mind looses them from their tether. Every time! Let someone else speak them. No? Surely someone still remembers the beginning? I mean the very first verse? Not even the brother who recited it back when we started out this season? No? No one. Then, please, let me speak a while. If, somewhere along the way, any of you remembers that verse, let him recite it, but until then, bear with me. At worst, we’ll keep climbing until someone remembers the words, and then we’ll end up where we end up every season, at the opening, on the plain. A little worse for wear, true, a little more exhausted, but such is life. At best, we’ll follow the one who’s missing to some other place.

—

...(more)

Gabriel Blackwell

_______________________

Once set down on paper, each fragment of memory . . . becomes, in fact, inaccessible to me. This probably doesn’t mean that the record of memory, located under my skull, in the neurons, has disappeared, but everything happens as if a transference had occurred, something in the nature of a translation, with the result that ever since, the words composing the black lines of my transcription interpose themselves between the record of memory and myself, and in the long run completely supplant it.

Simultaneously, my recollections grow dull. To conceptualize this fact, I use the image of evaporation, of ink drying; or else water on a pebble from the sea, the sun leaving behind its dulling mark, the salt film. The recollection’s emotion has disappeared. Occasionally, if what I have written in explanation satisfies me (later, on rereading), a second induced emotion, whose origin is the lines themselves in their minute, black succession, their visible thinness, procures for me a semblance of a simulacrum of the original emotion, now grown remote, unapproachable. But this emotion does not recur, even in lesser form.

Jacques Roubaud, The Great Fire of London

quoted in from madeleine e.

Gabriel Blackwell

3am

_______________________

Die Alaunstraße in Dresden

1914

Ludwig Meidner

b. April 18, 1884

_______________________

Blackwell's larger point, it seems, is that, at a structural level, all narrative is a kind of paranoia.

Gabriel Blackwell and the Legacy of Metafiction

Joe Milazzo reads Gabriel Blackwell's Critique of Pure Reasonentropy

(....)

... surely Blackwell, who is much more meticulous in his playfulness, knows that the post-modern moment has passed? Post-modernism is now just another commodity in the nostalgia market; it has depreciated into an image that cycles through countless Tumblr feeds for its quaintness value. Post-modernism is now nothing more or less than decor, a reference to a collective memory of the falsity of collective experience nooked and crannied into our so-called intellectual life like the Stratocasters and “Run Forrest Run” bumper stickers and velvet paintings and dazzlingly crappy Americana hodge-podged on the walls of a TGIFridays.

So why care about the post-modern triumphs of metafiction, and why revive it? These questions, as well as the question of what Critique of Pure Reason does differently with the tropes of metafiction, cannot be separated from the question of why we take our entertainment so seriously, and why we declare—and not without some Gollum-like voracity; witness the live-Tweet apocalypse that was the minutes following Game of Thrones‘ infamous “Red Wedding” episode—ownership of what can never be our exclusive property. In its day, metafiction was viewed as an elitist enterprise, one that required a certain class of reader, and, in all fairness, it was and it did. Metafiction was elitist in the way that the generation that came of age in the late 60s and early 70s remains elite: by means of a supremely confident, consistent and inflexible exercise of their narcissism. The metafictions produced by DeLillo, Pynchon, Gass (who coined the term) et al. aimed to separate the dross and shibboleths of a previous generation’s definitions of orderly life from new ideas of lasting value via stories that were Baroque with a hipped-up self-awareness. Metafiction’s vogue was as much an expression of that Boomer pursuit of higher consciousness as it was of reflective of the opening up of the American novel to Continental influences. Metafiction was also therapeutic, in its own way, its mechanics serving as an exorcism of that Conspiracy that through multiple assassinations and Vietnam and Watergate had posited itself as the Maxwell’s Demon of recent history. Readers of metafiction could indulge in a double appreciation. First, readers could entertain and be entertained by an articulation of their own doubts about the reliability of any reality whose apparency was confirmed via mediation. Secondly, by outlasting the convolutions of metafiction and assuming a position from which they could substitute one’s own convolutions within the story, readers could, in effect, narrate to themselves, “Now I see what I am not to believe, and how.” Not without reason was some of the best metafiction written during its period of ascendance overtly political.

(....)

Like the other persons we encounter in this book’s pages, and whether we belong there in those pages or not, we exist in a realm suspended between fiction and reality. Yet neither is home for us. It doesn’t really matter, either, if the domains of fiction and reality overlap or dissolve into each other or create a million new Big Bangs every time their proximities cross their streams. Their between-ness and ours is never annulled, only sustained by its weirdly boundless singularity. Far from debunking metafiction by aping it, Critique of Pure Reason seeks to turn the engine of its perspicacities on that sense of exception it cultivated, then allowed to grow out-of-control. The volume’s final words come from, or are attributed to, Pauline Kael’s review of a pre-Blue Velvet Dino De Laurentis’ 1976 instant-punchline remake of King Kong—as mythic a movie as has ever been made. “It’s a joke that can make you cry.” The same can be said for what metafiction, at one time, could have been. Happily, rather than lament, this Critique of Pure Reason goes about its work, and its possibilities are still possible.

...(more)

_______________________

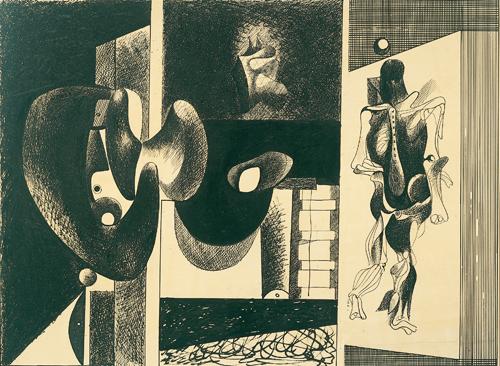

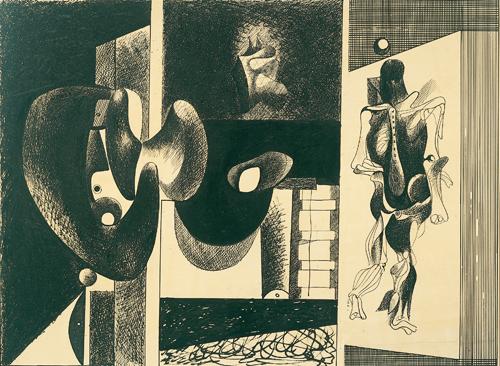

Nighttime, Enigma and Nostalgia

Arshile Gorky

b. April 15, 1904

_______________________

Childhood Triptych

Karen Solie

partisan

i.

Whether I’d seen them with, so to speak, my own eyes,

was not the point. I may have filed some false reports,

but I’d seen plenty. Many nights they summoned me

in their fraudulent Rapture, discriminating not between

creatures and objects lifted equally into unbelonging

and returned with forms, that is, spirits,

broken. Before the world destroys us, it confirms

our suspicions. And so I kept my incredulity at the irreparable

local disdain for storm cellars to myself, investing instead

in quasi-religious superstition and my firstborn birthright

of being consistently wrong. As atmospheric hydraulics

once more engaged and the home acre prepared to revolve

like a sickening restaurant, as the grain’s hairs stood

on end and rope ladders descended from the gospels’

green windows, my mother, in the manner of someone

who believes wholeheartedly in God’s love and its profound

uselessness, said we’d take our chances in the basement.

...(more)

.....................................................

For decades, John Ashbery has shown us how to be non-heroic (which hasn’t stopped us from pedestalizing him…). There is something both Ashberian and non-Ashberian about Solie. Like him, she writes sentences in motley registers that accrete into poems with unpredictable logopoieic shapes. Their sentences are similarly centrifugal, though hers are never taken to the dissociative extremes his are. He sounds like a radio on scan; she sounds like she’s talking and driving ...

Ange Mlinko

The Road In Is Not the Same Road Out

Karen Solie anansi

_______________________

Pierre Gain en élève studieux

au balcon

circa 1909

Gustave Gain

(1876-1945)

Les Autochromes

via Nag on the Lake

_______________________

ALL THAT IS CERTAIN IS NIGHT LASTS LONGER THAN THE DAY

Karen Solie

Look at your past, how it’s grown.

You’ve known it since it was yea high. Still, you,

as you stand now, have never been there. Parts worn out,

renewed, replaced. Though you may bear the same name.

You’re like the joke about the axe.

In time you’ve learned that to behave badly isn’t

necessarily to behave out of character. To thine own self

be true. In script above the nation’s chalkboards,

the nation’s talkshows. And not a great idea,

depending. It’s too much for you, I know.

One day your life will be a lake in the high country

no one will ever see, and it will also be the animals

of that place. Its figures indistinguishable from ground.

All of time will flow into it.

Leave the child you were alone. The wish to comfort her

is a desire to be comforted. Would you have

her recognize herself buried alive

in the memories of a stranger? Avoideth the backroads,

doublewides of friends, and friends of friends. . . .

Some of what you would warn against

has not yet entered her vernacular.

She travels unerringly toward you, as if you are the North.

Between you, a valley has opened.

In this valley a river,

on this river an obscuring mist.

A mist not unlike it walks the morning streets, comments on

the distinction of Ottawa from Hull, Buda

from Pest, what used to be Estuary from what used to be

Empress and the ferry that once ran between them.

Karen Solie at Poetry International

_______________________

The Poetic World of Karen Solie

Jon Eben Field

(....)

Solie knows that language is not adequate to experience and perception. This lack between experience and articulation creates a “mourning in the use of language.” Although this mourning can emphasize the inadequacy of words, for her, this gap is fruitful as a source of inspiration. Using this inspiration grounds her poems in the precision of naming; naming the complexity and intensity of experience creates a generative power. For Solie, “there's a poetry to the names that people give things” largely because “we are metaphorical creatures.”

Solie uses her words to point out the representational crisis at the limit of language. She is acutely aware of language's fey shadow, that unnameable space where the poet exists with and without words. Poetry reviews, revitalizes and recreates the world. We can learn to see the world differently, time and time again through poems. She understands that poetry “allows us to notice things and to think about their complications and their implications.”

Solie is fascinated with the intersections of probability, determinism and fate. She sculpts the waves of determined reactions that arise from action and choice into poetic friezes. She is intuitively, spiritually and mathematically engaged with the “old split, which is sort of artificial to [her] mind, between free will and determinism.” We are both drawn to and thrown into this poetic world. We are free to explore our lives and thrown like flotsam and jetsam into the vast ocean of life's consequences.

(....)

Solie's uses language to point out what is passed over, forgotten and lost. And in that gesture we become aware of the abundance that is and is not on the page. Reading poetry requires a type of double-vision. If we are lucky, the words of the poem open up a space for us to inhabit a verbal texture. But this interior world of the poem only makes sense when understood next to the world within which we live, breathe, eat, sleep, drink, speak and write. But how can she accomplish this? In her words, the gesture is completed by “throwing one's mind outside the page.”

Poetry matters. There are songs I've always believed poets could hear above, below, beyond or, perhaps more accurately, within the din of ordinary life. In that belief, I've looked for poetry that hears and responds to what would otherwise lie hidden in the world. Karen Solie's poetry matters because it sings an eloquent version of this song about life, landscape and language.

...(more)

_______________________

Gustave Gain

|