|

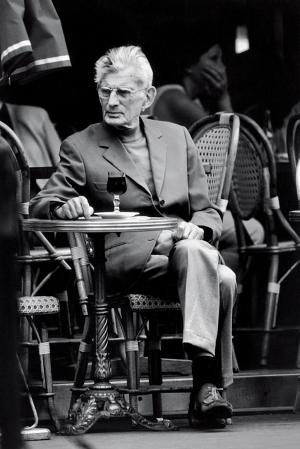

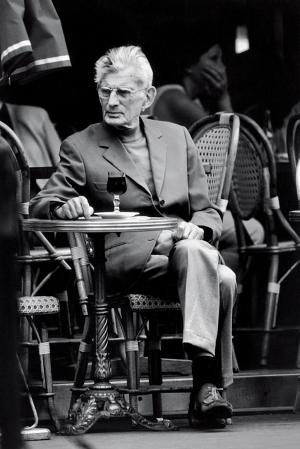

Eduardo Galeano

1940 - 2015

photo - Alberto Estévez

“My great fear is that we are all suffering from amnesia. I wrote to recover the memory of the human rainbow, which is in danger of being mutilated.”

Eduardo Galeano’s Words Walk the Streets of a Continent

Benjamin Dangl

(....)

During Argentina’s 2001-2002 economic crisis, Galeano’s words walked down the streets with a life of their own, accompanying every protest and activist meeting. Factories were occupied by workers, neighborhood assemblies rose up, and, for a time, revolutionary talk and action replaced a rotten neoliberal system. Galeano’s upside-down view of the world blew fresh dreams into the tear gas-filled air.

In the streets of La Paz, Bolivia, pirated copies of Galeano’s classic Open Veins of Latin America are still sold at nearly every book stall. There too, Galeano’s historical alchemy added to the fire of many movements and uprisings, where miners of the country’s open veins tossed dynamite at right-wing politicians, and the 500-year-old memory of colonialism lives on.

(....)

With the small mountain of books and articles he left behind, Galeano gives us a language of hope, a way feel to feel rage toward the world while also loving it, a way to understand the past while carving out a better possible future.

“She’s on the horizon,” Galeano once wrote of utopia. “I go two steps, she moves two steps away. I walk ten steps and the horizon runs ten steps ahead. No matter how much I walk, I’ll never reach her. What good is utopia? That’s what: it’s good for walking.”

...(more)

_______________________

Bror Julius Olsson Nordfeldt

b. April 13, 1878

_______________________

'Extraordinary experience will not be locatable'

Joe Milutis

Bright arrogance #5

jacket2

Emily Dickinson’s poetry is perhaps the closest thing canonical American literature has to a “sacred language.” In Robert Duncan’s lectures on Dickinson, we could say that he posits her as the ultimate untranslatable poet, even within her own language. In her poems she “bring[s] us to the line where everything is so fraught with meaning that we can’t find the meaning.” And so, even in a casual reading of her there is a dogged engagement with the translational sublime, performed with more or less sensitivity, because she is meaning something (Duncan is at pains to distinguish her gnomic utterances from the more postmodern disjunctions of language poetry), even if that something is a nothing that is legible. If the possibility of translation is assured by some structure of commonalities that all languages negotiate, these commonplaces are confounded in her Amherst garden. “Extraordinary experience will not be locatable,” Duncan says, and in particular extends the enigma of Dickinson’s work and its untranslatability to her sexual experiences with other women, which only could have been experienced through clear, positivistic, and communicative language in a cultural context that could readily explain them, or explain them away.

...(more)

_______________________

Carlo Carrà

d. April 13, 1966

_______________________

Texts for Nothing #4

Samuel Beckett

b. April 13, 1906

... What am I doing, talking, having my figments talk, it can only be me. Spells of silence too, when I listen, and hear the local sounds, the world sounds, see what an effort I make, to be reasonable. There's my life, why not, it is one, if you like, if you must, I don't say no, this evening. There has to be one, it seems, once there is speech, no need of a story, a story is not compulsory, just a life, that's the mistake I made, one of the mistakes, to have wanted a story for myself, whereas life alone is enough. I'm making progress, it was time, I'll learn to keep my foul mouth shut before I'm done, if nothing foreseen crops up. ... To breathe is all that is required, there is no obligation to ramble, or receive company, you may even believe yourself dead on condition you make no bones about it, what more liberal regimen could be imagined, I don't know, I don't imagine. No pomt under such circumstances in saying I am somewhere else, someone else, such as I am I have all I need to hand, for to do what, I don't know, all I have to do, there I am on my own again at last, what a relief that must be. Yes, there are moments, like this moment, when I seem almost restored to the feasible. Then it goes, all goes, and I'm far again, with a far story again, I wait for me afar for my story to begin, to end, and again this voice cannot be mine. That's where I'd go, if I could go, that's who I'd be, if I could be. ... No pomt under such circumstances in saying I am somewhere else, someone else, such as I am I have all I need to hand, for to do what, I don't know, all I have to do, there I am on my own again at last, what a relief that must be. Yes, there are moments, like this moment, when I seem almost restored to the feasible. Then it goes, all goes, and I'm far again, with a far story again, I wait for me afar for my story to begin, to end, and again this voice cannot be mine. That's where I'd go, if I could go, that's who I'd be, if I could be. ......(more)

_______________________

Samuel Beckett

1988

b. April 13, 1906

Stirrings still

Samuel Beckett

(....)

2

As one in his right mind when at last out again he knew not how he was not long out again when he began to wonder if he was in his right mind. For could one not in his right mind be reasonably said to wonder if he was in his right mind and bring what is more his remains of reason to bear on this perplexity in the way he must be said to do if he is to be said at all? It was therefore in the guise of a more or less reasonable being that he emerged at last he knew not how into the outer world and had not been there for more than six or seven hours by the clock when he could not but begin to wonder if he was in his right mind. By the same clock whose strokes were heard times without number in his confinement as it struck the hours and half-hours and so in a sense at first a source of reassurance till finally one of alarm as being no clearer now than when in principle muffled by his four walls. Then he sought help in the thought of one hastening westward at sundown to obtain a better view of Venus and found it of none. Of the sole other sound that of cries enlivener of his solitude as lost to suffering he sat at his table head on hands the same was true. Of their whenceabouts that is of clock and cries the same was true that is no more to be determined now than as was only natural then. Bringing to bear on all this his remains of reason he sought help in the thought that his memory of indoors was perhaps at fault and found it of none. Further to his disarray his soundless tread as when barefoot he trod the floor. So all ears from bad to worse till in the end he ceased if not to hear to listen and set out to look about him. Result finally he was in a field of grass which went some way if nothing else to explain his tread and then a little later as if to make up for this some way to increase his trouble. For he could recall no field of grass from even the very heart of which no limit of any kind was to be discovered but always in some quarter or another some end in sight such as a fence or other manner of bourne from which to return. Nor on his looking more closely to make matters worse was this the short green grass he seemed to remember eaten down by flocks and herds but long and light grey in colour verging here and there on white. Then he sought help in the thought that his memory of outdoors was perhaps at fault and found it of none. So all eyes from bad to worse till in the end he ceased if not to see to look (about him or more closely) and set out to take thought. To this end for want of a stone on which to sit like Walther and cross his legs the best he could do was stop dead and stand stock still which after a moments hesitation he did and of course sink his head as one deep in meditation which after another moment of hesitation he did also. But soon weary of vainly delving in those remains he moved on through the long hoar grass resigned to not knowing where he was or how he got there or where he was going or how we was going to get back to whence he knew not how he came. So on unknowing and no end in sight. Unknowing and what is more no wish to know nor indeed any wish of any kind nor therefore any sorrow save that he would have wished the strokes to cease and the cries for good and was sorry that they did not. The strokes now faint now clear as if carried by the wind but not a breath and the cries now faint now clear.

3

So on till stayed when to his ears from deep within oh how and here a word he could not catch it were to end where never till then. Rest then before again from not long to so long that perhaps never again and then faint from deep within oh how and here that missing word again it were to end where never till then. In any case whatever it might be to end and so on was he not already as he stood there all bowed down and to his ears faint from deep within again and again oh how something and so on was he not so far as he could see already there where never till then? For how could even such a one as he having once found himself in such a place not shudder to find himself in it again which he had not done nor having shuddered seek help in vain in the thought so-called that having somehow got out of it then he could somehow get out of it again which he had not done either. There then all this time where never till then and so far as he could see in every direction when he raised his head and opened his eyes no danger or hope as the case might be of his ever getting out of it. Was he then now to press on regardless now in one direction and now in another or on the other hand stir no more as the case might be that is as that missing word might be which if to warn such as sad or bad for example then of course in spite of all the one and if the reverse then of course the other that is stir no more. Such and much more such the hubbub in his mind so-called till nothing left from deep within but only ever fainter oh to end. No matter how no matter where. Time and grief and self so-called. Oh all to end.

...(more)

_______________________

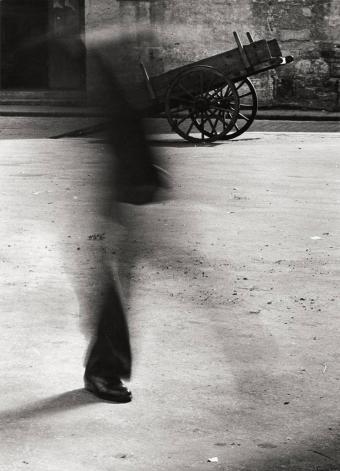

photo - mw

April 13, 2015

Peter Culley

mosses from an old manse

_______________________

A Letter to Hammertown

Peter Culley

lemon hound

1.

The orange chestnut canopy has shredded

into a discarded hamper

of wet umber, umber-orange,

lacy amber, blood-orange

& bloody amber rags

through which tires carve calm channels in time,

neat stripes of a general widening

as the averages catch up.

I snobbishly note on Shasta’s behalf

the oddly spindly thighs

of her underemployed big city sisters

short-leashed

by fedora dad or leopard mom

insulting white bags

threaded through their collars

a badge of slavery–

no sniff, no FIELD, no flicker.

On the soundwalk the light

is louder than I remember,

darkest in the undertree gloom

dramatic gravel bony underfoot

until cranked across by cable car,

eighties rain filtering

through a carpentered forties porch

onto the basement suite stairwell.

Twin ghosts of my brother

pass each other at different times

& don’t look up.

wary, preoccupied, in transit.

Later I made a loop

of the pebble crunch & engine

so that they’d course

through her headphones

& make a kind of disco

that I could then loop again

& install in a top branch

under the streetlight

a kind of permanent radio.

Missing though: the persistent

sense of misdirection, the relaxation

of muscles associated

with certain vocabularies,

the slow rounding off

of matter under successive waves

of daylight & water.

The next day the microphone

was a hummingbird

extracting sugar from ink,

hovering locked sentences

breaking up in a

riot of orange lichen

& red bricks flattened under solar flares.

(....)

4.

& in sleep

the furious forest

reconstitutes itself

the ringing silence

thick fleshly endrenched

footfall & Shasta’s fast footfall

lakeside endorsement

underalder endorsement

ringing antennae of sleep

along the long hillsides

always stumbling & climbing

gravity heavy feet prescient sleep

sleep coming to each limb

separately heaving

the will forward fall asleep

walk & fall asleep

along the long lakesides.

Run & drift awake

the stubble of vocabulary

swirls around your feet

in spouts of antique bliss

the furious forest

now suffused with a pink x-ray light

under which the bones

of the street are revealed in

arched & baroque forms

ringing byzantine brass

through coloratura speakers

interrupts the operations of sleep

along the long avenues

always always climbing

the will forward will fall asleep

& run & drift awake

along the long lakesides.

...(more)

Peter Culley

(1958-2015)

In Memoriam: Peter Culley

Books by Peter Culley

His landscape is equally a product of cultural memory, real estate development, individual perception and geology. The lapsed economy of Culley’s place and its seeming insignificance in contemporary cultural and political movements ironically lend Hammer- town a potent metaphorical power. The moving filaments of Culley’s witnessing attention among the weathers and ephemera of the hinterland begin to expose the speciousness of centrist self-regard.

The lyric poem is now a very minor cultural form. But its integrity can be located in the precise and difficult description of the shape of between. Culley dares to give language to this interregnum, this morning which has used up all the verbs. It is importantly minor, what he can do.

-

Lisa Robertson

_______________________

Because I Am Always Talking: [pdf]

Reading Vancouver Into The Western Front

Peter Culley

(....)

The literary reading is one of the last survivors of a once thriving oratorical culture. The

decline of such other oratorical institutions as the sermon, the public lecture and the political

speech, and the concomitant emergence of such new forms as sound-bite rhetoric, rap music

and stand-up comedy have given the literary reading an anachronistic, genteel air, one

whose demands on attention seem to speak to another time. Even the simple act of reading

aloud to loved ones, one of the most intimate experiences that literature allows us, has now

sadly all but disappeared beyond the confines of the nursery, replaced by the competing

schmooze of Arsenio and Jay. So why then, on any given Vancouver evening, do groups of

people travel various distances, often in the rain, to hear writers read aloud from their work?

Work that, often enough, does not offer the simple comforts of either lyrical or narrative

flow?

(....)

My point here is simply that during the act of vocal transmission, written work is subject to a

variety of effects and transformations, both conscious and unconscious. Many writers ignore

or underestimate such effects, acting as if their work truly 'speaks for itself', as if their

larynxes and voice boxes were acting as the transparent medium of their written intentions.

An insistence on inscription as the final arbiter of a text's reality makes not only an

unsupportable claim on the nature of an audience's attention, but badly underestimates the

demonic power of speech. Who dares assume that a listener, having heard a writer, is

thereby somehow obligated to read the writer's work, or that this reading offers a necessarily

deeper or more profound experience? The most successful literary readings are those that

insist on their ephemerality, their manifest existence as discreet events in time. The contract

between listener and writer is fulfilled within the act of listening. Vancouver audiences

know this, and attend readings less as parishioners in the church of print than as wary

flaneurs in search of exotic left-brain stimulation. (....)

_______________________

Peter Culley

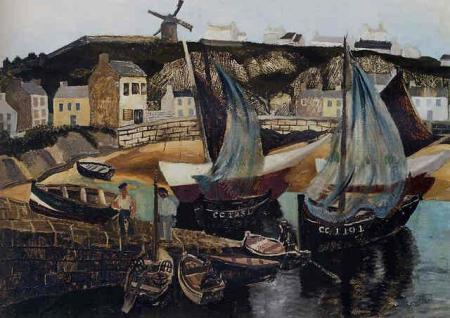

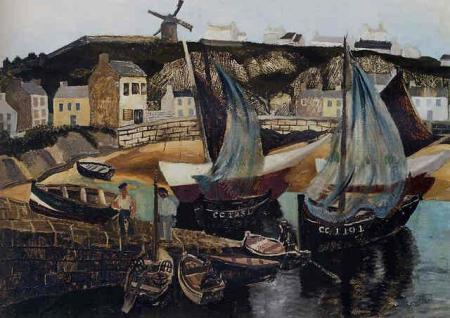

Porthmeor Beach

Ben Nicholson

b. April 10, 1894

_______________________

Turbulent thinking

Lyn Hejinian

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

(....)

A cold wind pushes against the northward progress of the occasional pedestrian, a plastic wrapper slips past a parking meter and disappears under a red car. In Minima Moralia, Adorno remarks, ‘To happiness the same applies as to truth: one does not have it, but is in it.’ But what if the truth one is in — the truth of one’s situation or of one’s entire epoch — is an untruth (a lie, a fabrication, a myth, or a lack of truth altogether; not just a figment of false consciousness but the very condition that produces it? Certainly such a truth-of-one’s-time would be an unhappiness. Adorno’s aphorism, then, with a slight adjustment (and added poignancy) would assert that to unhappiness the same applies as to untruth: one does not have it, but is in it. It’s not the wind but the sun that expands the neighborhood through which vehicles, pedestrians, pets, children, residents, bugs, birds, visitors, bacteria, move in their efforts at perfection. (....)

Art historians generally seem to be better at seeing the quiddities of everyday life than literary critics, who read into depictions of it coherences that are essentially irrelevant to the everyday. Apertures expand, sprawl over the edges of a frame. Thinking generates turmoil, something entirely different from entropy, it doesn’t settle and it doesn’t resolve, unless briefly, so the thinker can take a breather. Meanwhile, in the thinking, tension builds. An excess of spirit suffuses the body, it contorts the face, which is seen to convulse, either in laughter or in grief. Some human feels it in the stomach — a tightening, reflux, pain in the solar plexus. Some cat wakes suddenly. The cat launches its mouth at its haunch, licking, nibbling (affectionately, it seems). A horse shies, bucks, veers, and drops its head to graze. Deer, reclining in a meadow, leap to their feet and flee. How do I release tension? Not very well. A glass of wine. Currently, despite my sympathy for Tolstoy’s charitable impulse, I could not readily include a policeman in any ‘prehensile web of love’ I might cast. Though we feel liberated at the conventional end of a fairy tale (‘and they lived happily ever after’), we are aware of anxiety lurking along the fraying edges of ‘ever after,’ where existence continues beyond the scope of what’s told, and perhaps beyond the scope of what can be told. Goethe’s last words were, so they say, ‘More light.’ I could imagine a variant of these: ‘More sleep.’ But those are mere words, and a translation, at that, and not even last words, as more words have followed since, including those that proclaim them ‘last.’ Mercilessly.

...(more)

_______________________

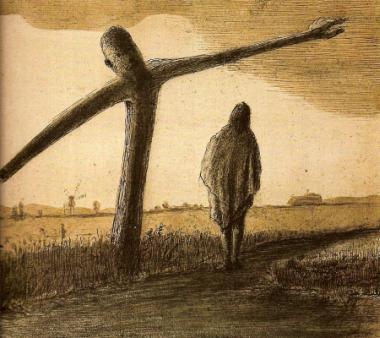

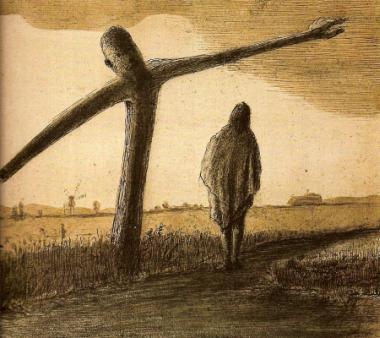

Le poteau indicateur

Alfred Kubin

b. April 10, 1877

_______________________

Cartographies of the Absolute

Landscapes of Capital

In the context of the widespread conviction that we now inhabit the Anthropocene, an epoch in which mankind has risen to the dubious stature of ‘geological agent’, some earth scientists have cut through the periodising controversy – Did the Anthropocene begin with the human discovery of fire? With the industrial revolution? – by dating the onset of man’s geological maturity with disconcerting precision: July 16, 1945, the first test-denotation of an atomic bomb. The (unconsciously) political character of periodization as an act of representation and totalization could not be more clearly illustrated. The ‘end of nature’ (as autonomous from human agency) here coincides with the ‘end of history’ (as the inability to articulate that agency as a common project of emancipation), and postmodernity receives a kind of geological imprimatur, by the same token losing its own temporal contours. ‘We’ make nature, but recognizing this we also confront our inability to make history, as natural processes inextricable from ‘our’ historical agency threaten to make and unmake the present and the future in the absence of our agency. This is the backdrop of ongoing attempts to represent in the medium of photographic landscape a world wholly made over by capital accumulation, not so much an Anthropocene as a Capitalocene, to use the term proposed by Jason W. Moore.

This is a predicament arguably crystallized in the very title of a landmark exhibition from 1975, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered landscape.That show, bringing together photographic series by Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams, Joe Deal, and others, continues to inform a photographic vocabulary which tries to picture humanity’s footprint in the terrains, built forms, logistical infrastructures, energy complexes and sheer waste which simply are the landscape of an increasingly urbanized species – witness the work of the Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, but also Thomas Struth or Mitchell Epstein. There is a rich, critical literature on New Topographics and its aftermath. What I wish to ask here is a disarmingly simple question: why are photographs of manufactured landscapes so often depopulated?

...(more)

_______________________

Long Branch

Michael Ashkin

.....................................................

Long Branch: A Conversation With Michael Ashkin

The Great Leap Sideways

(....)

There’s a fundamental tension through these bodies of work between rigorously systematic and unpredictable forms, which mirrors a tension between human experience and the ordering of life into repetitive grids. We have made ourselves over as ‘man’ according to the logic of the urban grid, but the disassembly of communities reveals the arbitrariness of that logic, so could you talk about the relationship in your work between the systematic and the individual, or between landscape and memory?

MA: This is a great question and it gets to the heart of what I am thinking about, albeit without the rigor of an urbanist or a scholar. Your quote by Robert Park reminds me of Manfredo Tafuri’s description of the grid in American cities as a pragmatic form implemented to facilitate the efficient flow of goods in a capitalistic economy. In other words, thinking of the urban grid as an instrumental form related to the functioning of the machine. And we could relate this to Marx’s observations that the transition from tool use to machine use reveals a reversal of roles: man starts by using tools for his own purposes, but, with the advent of industrialization, finds himself put in service to the machine. With the advent of the industrial machine we find all aspects of our world, including ourselves, abstracted and instrumentalized, turned into what Heidegger calls “standing reserves.” At this point I think it would be fair to say that we all find ourselves within a global apparatus that follows this logic of the technological and economic machine.

Photography is a complicit and exemplary manifestation of this instrumentalized view of world. The camera is itself an apparatus, and it imposes a particular technological treatment upon space, regarding it as a uniformly gridded container in which human action is both possible or constrained. The camera is the logical technological extension of renaissance single-point perspective (assessed by the individual eye), renaissance engineering and military axonometric projections (uniformly measurable), and imperial cartography (eminently available). This idea of space as machinic, militarized, and available is based on the larger idea of capture. Photography is part of the larger apparatus that assesses the landscape in order to colonize, grid, and exploit it. In the end, the landscape has become absorbed into the same technology that spied it out. Perhaps even more crudely, we could call the camera an instrument of real estate. To me, photography feels unavoidably like surveying.

...(more)

_______________________

Castagnola

Ben Nicholson

_______________________

Five Museums

Colleen Hollister

conjunctions

Museum of Arctic Maps

Plum. Cedar. In the center, trees grow. Tangle and reach, search downwards for sky. The floorboards lay out for you a puzzle. Language muddled like mud in the ears. So much in the way of anatomy and yet your walking still fails. Woods that shape the air for you. Moon a flower. Cast iron. Copper. Like you are being dragged to sea. Deep blue glass filled with willing poison. Your limbs drop off, rearrange themselves. Everything made of cork and porcelain. Rosemary. Honeysuckle. Cypress. Inside, the heart buzzing like innumerable insects. Imaginary irregular coastlines. Cliffs of dry grass. Reindeer lichen. A small room crowded with things made of metal. A drawing of the flowers in the body: blooming mess. Tiny winding streets. The most intricate doorways. Everyone has carved them. To watch the lightning means a search for light for what makes the trees jump. Once, you knew a house filled with paintings. From the ceiling beams the sky near the bears. Just see how the stars twist. How the lakes rust. Rooms full of women transformed into bees. How a small space makes you feel like you are dying. How the grass grows through the paper at your feet.

...(more)

George H. Seeley

_______________________

Manifesto For Zombie-Communism

Oxana Timofeeva

(....)

The border between hope and despair is very subtle. There can be a moment where they are almost indiscernible, but right after this moment – when THIS is not only undesirable, but impossible, and absolutely unbearable, – in brief, when hope slips away, or rather leaps into despair – there is a point of no return. Only those who are desperate are ready to die in this struggle – not because they hope for a better future, but because they cannot stay in the present. Desperation simply means that things cannot stay like this. And here is the difference – until there is no hope, true revolutionary action is postponed.

...(more)

.....................................................

What is to be done? On Chto Delat

e-flux conversations

Russian artist collective Chto Delat's exhibition, “Time Capsule. Artistic Report on Catastrophe and Utopia,” at KOW in Berlin, is a must see. Whereas most Europeans are mired in controversies over what forms the coming catastrophes might take, to Chto Delat, the apocalypse has already transpired. We are past the tipping point; the “revolution” already happened--it was however not a progressive one. “We lost,” they state in their press release. ...

(....)

In the diffuse world of the post-Fordian economy, calls for acceleration feel a bit quaint: the infrastructure is still standing, but capitalism as we knew it is a thing of the past. Under the twin blades of financialization and what is called “the sharing economy,” capital has emancipated itself from the social––which is not to say it did away with work, just the need to pay formal salaries. As for the State, at the moment, its main function is simply to guarantee that credit is converted back onto cash payments, no matter how much misery such conversion elicits. Ironically, as the new Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis put it, it became the Left’s task to arrest capitalism’s free-fall in order to buy time to formulate an alternative––since at the moment the Left remains “squarely defeated,” any upheaval would end up in fascism.

...(more)

via Jodi Dean

_______________________

Arthur Streeton

b. April 8, 1867

_______________________

Three Poems

Maxine Chernoff

conjunctions

Invention

Maxine Chernoff

“Daylight disbanded the phantom crew.”

—Edith Wharton

The sentimental is a rumor,

Inexorable memory

of cottonwood seed

left in its husk, of

a grief spent down to dust.

No question arched

towards lucidity, its quivers

oil- and water-worked.

How we land is

called the drowning.

We launch paper boats

into reluctant space,

speak of containment

as if it were a plan.

Your last avowal

has left the station.

There you stand,

without a witness,

consigned to speak as

words lift off the page.

...(more)

_______________________

Reading Topographies of Post-Postmodernism:

Review of Post-Postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Just-in-Time Capitalism by Jeffrey T. Nealon

Laura Shackelford

electronic book review

(....)

Post-Postmodernism joins other recent attempts to reflect back on Jameson’s Marxist project and historical materialisms, more broadly, as a means to look forward and more effectively unfold new kinds of reading more responsive to the present, somewhat altered historical situation and its forceful, biopolitical modes of power. It introjects and creatively recombines Jameson’s reading practices with those that Christopher Nealon, Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Michel Foucault, Jane Tompkins, Alain Badiou, Catherine Malabou, Theodor Adorno, and Friedrich Nietzsche, respectively, recommend and/or practice. Its analyses selectively draw upon a remarkably eclectic, broad-ranging grouping of leftist theorists, including those featured in the collection rethinking A Leftist Ontology: Beyond Relativism and Identity Politics (in which an earlier version of the first chapter of the book appeared).

Importantly, its diagnosis of an emergent post-postmodernism, which it adeptly locates in and across cultural and economic practices as varied as “classic rock,” literary studies, Las Vegas, Don DeLillo novels, the corporate university, and conceptual poetry, serves as a productive, open-ended provocation to rethink literature, literary studies, and poetics—in their current relationships to capitalism, their abilities to re-engage the present terrain, and what that might do for the left. Post-Postmodernism tracks the “material links between literary works and their institutional and commercial context,” pursuing “the networks within which writing is located,” the places, purposes, and operations of literature and literary and cultural studies in their complex relations to emergent media, social, and economic systems, a preoccupation Daniel Punday suggests is a “condition of this post-postmodern moment” (“Looking for Writing After Postmodernism”). With this emphasis in mind, I recommend engaging Post-Postmodernism as a much-needed provocation, taking up, even taking liberties with Nealon’s invitation to participate in “periodizing the present, a collective molecular project that we might call post-postmodernism”.

...(more)

_______________________

Conspiracy

1910

George Seeley

1880-1955

_______________________

What we Talked About At ISA:

Embracing Indecision – Free Improvisation and Ethics as Action

Elke Schwarz

“Art is sort of an experimental station in which one tries out living”, John Cage once famously quipped. I hadn’t really given this line much thought until I watched a friend perform with his ensemble of free improvisationalists and began to understand – rather late, admittedly, – the creative interconnectivity of musical improvisation with aspects of political and ethical life. Encapsulated in Cage’s comment is the close enmeshment of creation and performance, fabrication and action, production and interaction, set against a modernist ontology of profound uncertainty, pertinent beyond disciplinary analytical divides. Simultaneously embracing and resisting the scientifically and technologically mediated quest for certainty in his time, John Cage, along with other experimental musicians and artists, perpetually sought to challenge a reliance on that which can be decided, by finding different disruptive and unfamiliar techniques.

These techniques are not merely aesthetic choices or practices, but rather, as forms of encounters, have also ethical and political relevance. ...

(....)

In this third and final paper, I try to rethink ethics in trans-disciplinary ways and turn to an unlikely source: free improvisation in music. Drawing on the principles of free improvisation, I suggest, allows us to conceptualise ethics as action rather than an applied abstract concept or epithet. In other words, to overcome the shortcomings of traditional modes of theorizing ethics in political theory, I look to free improvisation in music to rethink ethics and politics in less familiar ways, through the modes of sonic and corporeal interaction. ...(more)

The Disorder Of Things

_______________________

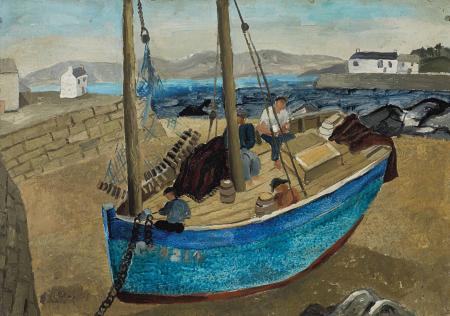

George H. Seeley

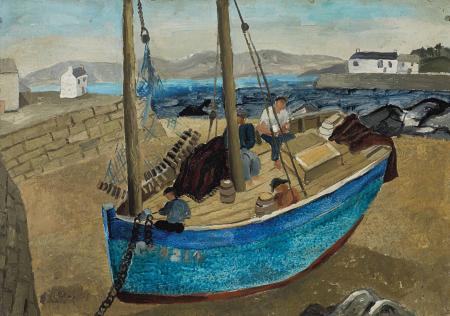

The Blue Boat

Christopher Wood

b. April 7, 1901

_______________________

Keeping Things Whole

Mark Strand

In a field

I am the absence

of field.

This is

always the case.

Wherever I am

I am what is missing.

When I walk

I part the air

and always

the air moves in

to fill the spaces

where my body’s been.

We all have reasons

for moving.

I move

to keep things whole.

_______________________

Translation as total listening

Joe Milutis

Right Arrogance: A Column On Experiments In Translation

Like many traditional translators, Benjamin describes a bad translation as the “inaccurate transmission of inessential content,” an inaccuracy that experimenters may revel in, as they amp up the noise between versions . . . We could say in a Lacanian moment that these new translators make a pere-version of the original, seemingly derailing the paternal metaphors and prohibitions implicit in God-as-namer and the translator as the guarantor of the name. But what would it mean to take Benjamin seriously (and, with Lacan, to avow the unavoidability of the paternal imago), to search for the Adamic patois, divine remnants of the sacred language in the infomatic jumble of disaggregated signs in our literary arcades? To seek . . . the unnameable.

As we pointed out in the last post, it is a mistake, at least on the surface, to read Benjamin as authorizing the more wild, postmodern translations that have emerged from the contemporary collisions of language poetry, conceptual writing, flarf and the world-wide-web. The same year that Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics was published in Paris (1916), Benjamin wrote that the notion of the arbitrariness of the sign, the “accidental relation” of word to object, was a bourgeois conception, and that “the word of God silently radiates in the mute magic of nature.” Given that Benjamin’s essay was published only posthumously, he may have realized how out-of-step he was, or rather, that he needed to find a way to admit this materialist arbitrariness, while maintaining the validity of his mystical theory of language.

The key might lay in a gesture he makes towards the end of “The Task of the Translator,” in which he posits interlinear Bibles as his ideal of translation. ...(more)

_______________________

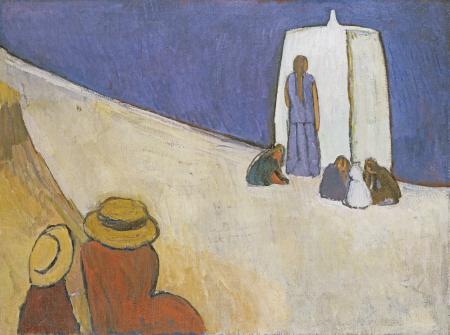

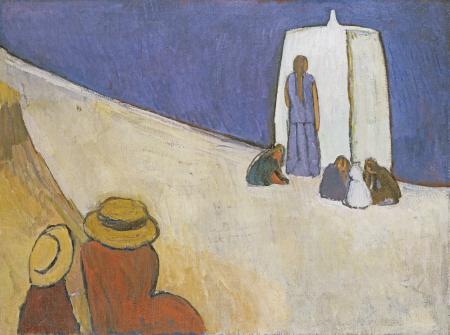

Studland Beach

1912

Vanessa Bell

_______________________

Decapitalism, Left Scarcity, and the State

Nina Power

Fillip

(....)

One final brief concluding point I want to flag up in the accelerationist work to date is an absence of thinking about the way in which the state continues to persist and how the state, or rather specific states, operates both in relation to capital but also in terms of repression. As the welfare components of the state are dismantled in a shockingly accelerated way in the UK and elsewhere, we are left merely with the repressive state apparatus: police, courts, prisons. We have not quite moved from disciplinary societies to societies of control. In fact, we have ended up with uneven and increasingly punitive examples of both, where surveilled surplus populations are left to their own fate or incarcerated or both. Rather than attack the left—whoever they are—as the “Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics” does, for their supposed lack of imagination, as if it were merely a matter of a lack of will, it would be a necessary step to examine in detail the way in which the state goes out of its way to prevent even the most minimal forms of opposition, from undercover spying, to political prosecution, to the use of police bail, to protest tactics, to jail, and so on. You may not care about the state, being interested only in a capitalism that supposedly transcends borders, but the state sure as hell cares about you the moment you step one inch beyond remarkably circumscribed boundaries. If reformist welfare policies such as universal basic income are the ones that a left accelerationism desires to put forward, it needs to think carefully about the way in which this plays out both in terms of being a national or global demand—and of course the latter is much more radical, reintroducing a notion of internationalism in the frame, as opposed to the ubiquitous concept of the “global,” a term far more acceptable to capitalism than “internationalism” could ever be, but also in terms of imagining how practically one would campaign and win on this issue. If the left lacks ideas and is forced to operate in a scarce world, both conceptually and materially, it is because of the sheer amount of time and resources ploughed into keeping it this way. As a political project, accelerationist or otherwise, this would mean confronting both the state and capital, without ignoring the violence of either.

...(more)

via Forgottenness

_______________________

Drying Nets Treboul Harbour

Christopher Wood

_______________________

True madness lies ahead for our species. Normativity, humanism, anti-reductionism, anything not bathed in the acid of neuroscience are all contributing to a sharpening of the knives. Building dams to keep the coming dissolution at bay they will render the shattering of the illusion that much harsher, harder. We are not going to Mars. We are going to go out of our minds.

Bleaker than Bleak Paul J. Ennis Three Pound Brain

Bleak theory accepts that it itself is almost entirely wrong. However, precisely on the basis that it accepts humans are almost always wrong about how it goes with the world and so what are the chances of this theory being right? In this paradoxical, confused sense it is a theory of human fallibility. Or the inability of humans to see themselves for what they are, even when, as per contemporary neuroscience, we kind of know (have you not yet heard the “good” news that you are not what you think you are?). We kind of know because we are beginning to see ourselves from the third-person perspective. Subjectivity is devolving into objectivity and objectivity entails seeing things clearly, even if not transparently. That opacity, always there in the subject-object distinction, is collapsing and the consequences are bleak. The second reality-appearance “appeared” as a crack we cracked. It has been going on ever since. Consider the insanity of the entire post-Kantian tradition and the in-itself – is it not just an expression of what it feels like when you recognise what was once a “transparent cage” (Sartre) of looking directly at the world is a hallucination, a real one, all the same.

We cannot outpace this very blindspot that renders us a self or a subject. We are deluded about our beliefs or intentions (a given, so to speak), but more significantly we are deluded that somehow we can ‘recursively’ leap ‘over our own shoulders’ and see not just the trick, as Bakker might put it, but something substantial. ...(more)

_______________________

The Day Begins

Christopher Wood

_______________________

The End

Mark Strand

1934-2014

Not every man knows what he shall sing at the end,

Watching the pier as the ship sails away, or what it will seem like

When he’s held by the sea’s roar, motionless, there at the end,

Or what he shall hope for once it is clear that he’ll never go back.

When the time has passed to prune the rose or caress the cat,

When the sunset torching the lawn and the full moon icing it down

No longer appear, not every man knows what he’ll discover instead.

When the weight of the past leans against nothing, and the sky

Is no more than remembered light, and the stories of cirrus

And cumulus come to a close, and all the birds are suspended in flight,

Not every man knows what is waiting for him, or what he shall sing

When the ship he is on slips into darkness, there at the end.

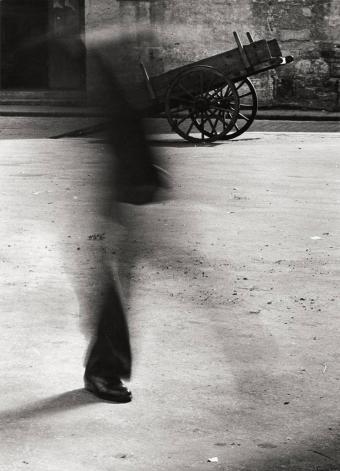

Otto Steinert

_______________________

Embodied Self: The New Causal History, Part II

Robert Greene II reviews Lynn Hunt, Writing History in the Global Era

(....)To many, Hunts’ notion of the embodied self likely sounds similar to “affect theory.” Though she neither cites any work of affect theorists nor any texts in the area of affect studies, a parsing of the differences between feelings, emotions, and affect would have benefited readers.[iv] If Hunt had touched on affect theory and affect studies more historyintheglobaleragenerally, she could have squarely confronted the challenge this scholarship poses to intellectual historians. Ruth Leys for instance observes that for “the new affect theorists…the important point to recognize is that they all share a single belief: the belief that affect is independent of signification and meaning.” Part of this belief, Leys notes, is that “cognition or thinking comes ‘too late’ for reasons, beliefs, intentions, and meanings to play the role in action and behavior usually accorded to them. The result is that action and behavior are held to be determined by affective dispositions that are independent of consciousness and the mind’s control.”[v] For these theorists, according to Leys, affect governs cognition. At the very least, such a position overturns the primacy that intellectual historians usually accord to ideas. At most, this position separates emotion from thought.

(....)

Notwithstanding these issues with Writing History in the Global Era, Hunt effectively unmasks the presuppositions of globalization talk to raise awareness of the potentially violent ideas that often sneak into discussions of globalization, above all the reduction of cultural and political expressions to economics. This awareness helps to explain how the expansion of self and society produced globalization as well as democracy as a way of life. Hunt thus offers more than an ideology-critique. Writing History in the Global Era’s greatest contribution is Hunt’s call to again investigate the self and society and the relationship between the local and global without yielding to economics yet still valuing causality through the concept of the embodied self.

...(more)

Embodied Self: The New Causal History, Part I_______________________

Otto Steinert

1915 - 1978

.....................................................

Consideration of an Image: Otto Steinert’s Ein-Fuß

-Gänger

Stacy Platt

The Space In Between

(....)What we see is not a whole man, but a part of a man. The part that moves forward, that keeps going. Or maybe it’s the part or the quality of man that’s there, that’s concrete and definable, while the rest of the corpus is ever in flux, a blur, ephemeral and ineffable.

(....)

Is it a blurred man? Or is it an erased man? It’s more of a mark on a page than the blur of motion that we’re seeing, the kind of mark made in a gesture of erasure. Make a drawing of a man in charcoal, then close your fist and smear it across the entire image of everything man-like of him save the foot. Everything else in the image is there, defined, and still: the grate, the tree, the sidewalk, the cobblestone street. Only the man in animate, and in his blur and in his foot, we are told that we cannot be sure of him, either. Or sure of what we think that we see.

(....)

What I’ve always loved about Ein-Fuß-Gänger is its inside-out-qualities; how it is and is not what it purports to be, that in the end it doesn’t purport to be of or about anything at all. It’s a bit of a visual joke, it’s quiet, it’s a small image and you could almost miss it entirely if you weren’t looking long or closely. It’s ambiguous, formally very pleasing, and is an image that I could linger over for a long, long while, losing myself in thoughts of absence and presence, the real and the notion of fiction, of place and not-place.

...(more)

_______________________

Jasmund # 29

Arno Schidlowski

via Arsvitaest

_______________________

Gone today

Justin Quinn and the gift of the translator

Walt Hunter

In his late work On Translation (2005), the French phenomenologist and literary theorist Paul Ricoeur brings together his lifelong investigations into ethics with a re-reading of Walter Benjamin's "The Task of the Translator" (1923). Ricoeur theorizes translation as a "correspondence without adequacy," urging us to give up on the idea of a perfect translation:

And it is this mourning for the absolute translation that produces the happiness associated with translating. The happiness associated with translating is a gain when, tied to the loss of the linguistic absolute, it acknowledges the difference between adequacy and equivalence, equivalence without adequacy. There is its happiness. When the translator acknowledges and assumes the irreducibility of the pair, the peculiar and the foreign, he finds his reward in the recognition of the impassable status of the dialogicality of the act of translating as the reasonable horizon of the desire to translate. In spite of the agonistics that make a drama of the translator's task, he can find his happiness in what I would like to call linguistic hospitality.

Justin Quinn is an Irish poet, scholar, and translator who teaches at Charles University in the Czech Republic. ...(more)

_______________________

Madrigal

Tomas Tranströmer

translated by Robin Fulton

I inherited a dark wood where I seldom go. But a day will come when the dead and the living trade places. The wood will be set in motion. We are not without hope. The most serious crimes will remain unsolved in spite of the efforts of many policemen. In the same way there is somewhere in our lives a great unsolved love. I inherited a dark wood, but today I’m walking in the other wood, the light one. All the living creatures that sing, wriggle, wag, and crawl! It’s spring and the air is very strong. I have graduated from the university of oblivion and am as empty-handed as the shirt on the clothesline.

from The Living and the Dead

quoted by Dave Bonta in Poet in the forest: Tomas Tranströmer

Via Negativa

a look at Tranströmer, The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems

translated by Robin Fulton

_______________________

Arno Schidlowski

_______________________

Standing Up

Tomas Tranströmer

In a split second of hard thought, I managed to catch her. I stopped, holding the hen in my hands. Strange, she didn’t really feel living: rigid, dry, an old white plume-ridden lady’s hat that shrieked out the truths of 1912. Thunder in the air. An odor rose from the fence-boards, as when you open a photo album that has got so old that no one can identify the people any longer.

I carried her back in side the chicken netting and let her go. All of a sudden she came back to life, she knew who she was, and ran off according to the rules. Hen-yards are thick with taboos. But the earth all around is full of affection and tenacity. A low stone wall half-overgrown with leaves. When dusk begins to fall the stones are faintly luminous with the hundredyear-old warmth from the hands that built it.

It’s been a hard winter, but summer is here and the fields want us to walk upright. Every man unimpeded, but careful, as when you stand up in a small boat. I remember a day in Africa: on the banks of the Chari, there were many boats, an atmosphere positively friendly, the men almost blue-black in color with three parallel scars on each cheek (meaning the Sara tribe). I am welcomed on a boat—it’s a canoe hollowed from a dark tree. The canoe is incredibly wobbly, even when you sit on your heels. A balancing act. If you have the heart on the left side you have to lean a bit to the right, nothing in the pockets, no big arm movements, please, all rhetoric has to be left behind. Precisely: rhetoric is impossible here. The canoe glides out over the water Five Poems [pdf]

Tomas Tranströmer

1931 - 2015

translated Robert Bly

janus head

from The Half-Finished Heaven: the best poems of Tomas

Tranströmer

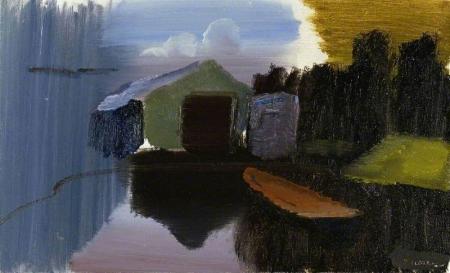

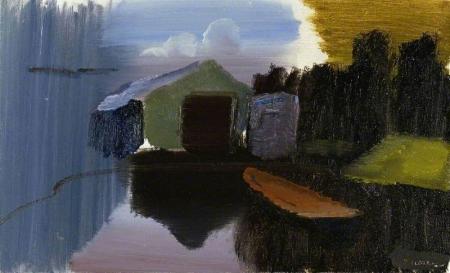

The Boat House

1956

Ivon Hitchens

1893 - 1979

_______________________

e-flux journal issue 64

“Architecture as Intangible Infrastructure”

guest-edited by Nikolaus Hirsch

with Keller Easterling, Pier Vittorio Aureli, Justin McGuirk, Ravi Sundaram, Eyal Weizman, Philip Ursprung, and Felicity D. Scott

Editorial

Architecture remains the most tangible way of constructing the social. Yet, the system we call “architecture” is not reducible to the physical, the tactile, the obvious. In the history of avant-garde architecture, immateriality and intangibility carried a promise of liberation, of escape from the heaviness of building, from completion, from gravity or reality. A new contemporary architecture would be built out of pure knowledge—drafted on paper as an idea to be shared, never bogged down by the technicalities of constructing in dimensional space, or even any spatial paradigm altogether. The history of the avant-garde can’t—as Beatriz Colomina has pointed out—be separated from its engagement with media and communication. Building would move at the speed of thought and spirit, superseding calculation, regulation, codes, and existing infrastructure.

Architects today do not conceptualize their work in such radical terms. Is it because they are too busy stalking clients in China and the Gulf? Maybe. But at the same time, architects today also have to contend with the fact that other immaterial, intangible forces have subordinated much of the spatial thinking that historically situated architecture in relation to the building and planning of spaces and cities. As Keller Easterling has written in a previous essay, “it is as if architecture, as customarily defined, cannot access some of the most important levers of explicit, measurable spatial change, leaving control of them largely to the financial industries.”

But what are these levers? Or for that matter, how has architecture always given form to the immaterial or intangible spatial effects in communication pathways, or war, rubble, memory, tourism, and cultural capital? Hasn’t architecture always provided a way of reading ethical transgressions in reverse, of giving them form, for better or for worse? How has physical architecture always been a symptom of ideology? How has it always been a communications infrastructure?

...(more)

_______________________

Landscape in Essex

Ivon Hitchens

_______________________

Words without Borders April 2015

Changing Landscapes and Identities: New Tamil Writing

An Introduction to Tamil Writing

Lakshmi Holmström

Early Tamil literary theory and poetics, from around the beginning of the Christian era, classified the subject matter of all literature into two main genres, akam and puram. Akam refers to the inner world, and is, effectively, to do with love. Puram refers to the outer world and consists of the praise of kings and patrons, and about war and the death of warriors. Both akam and puram are further divided into five main types, each associated with a particular landscape, tinai, and a system of images associated with that landscape.

The poetics of landscape continues to haunt Tamil writing. Of course, modern writers don't seek to replicate it, but rather, to glance at it, allude to it, dialogue with it, or even reconfigure it. That is the exciting bit. So we get in their writing cityscapes of alienation, snowscapes of exile and diaspora, landscapes of the imagination, fantasy worlds. But we also get confrontations and collisions between these different perspectives and worldviews; between the old and the new. So changing landscapes are also about changing identities.

...(more)

_______________________

Józef Czapski

b. April 3, 1896

_______________________

The Anthropocene and the End of Postmodernism

Deterritorial Investigations Unit

(....)

There is a quagmire here. On one hand, we can follow the postmodern sublime into the traps of the valorization of “immaterial labor”, and engage in a dangerous optimism of a Common hidden inside neoliberalism’s shell. And on the other, the enthusiastic embrace of the possibilities in advanced technology sidesteps the pitfalls of the political deployment of these technologies. Perhaps the best thing we can do is reverse Massumi’s projection, and view the hegemony of the network (and I say ‘hegemony’ because the network itself is simply another technology in neoliberalism’s arsenal) as the “becoming-human” of the planetary body.

And this is why we can proclaim that postmodernism has finally reached its end, and that its entire program has cut itself out at its very roots. One could list forever the ways in which the ‘dissolution of traditional bodies’ has been repelled: the rise of militant religious ideologies and the reassertion of the strong sovereign state, the waning enthusiasm for the neoliberal program and the callbacks towards the Keynesian era, and the rumbling of neo-Luddism, even in the high-tech industry sector. At the same time we can see how the postmodern condition continues to exacerbate itself: it is clear that neoliberalism is here to stay for a while (its particular governmentality is too entrenched), the sovereign state stills operates in a fully transnationalized network, and the rise of violent neo-fundamentalist groups like ISIS are, themselves, postmodern phenomena. Yet the largest bankruptcy of postmodernism is that the grand narrative of human mastery over the cosmos was never unmoored and knocked from its pulpit. Instead of making the locus of this mastery large aggregates of individuals and institutions – class formations, the state, religion, etc. – it simply has shifted the discourse towards the individual his or herself, promising them a modular dreamworld for their participation but more often than not providing only a disciplinary squalor.

...(more)

Damp Forest Walk

Ivon Hitchens

The Lives of Brian

A Documentary About Flann O’Brien

d. April 1, 1966

_______________________

Topology of Books Unread, Thoughts Revisited

Magus Magnus

flashpoint

Specifically, The Worm Ouroboros by E. R. Eddison and The Great God Pan

by Arthur Machen, from a Dover catalog. Nor have I read

Knut Hamsun’s Pan, but will someday, especially in light of his Hunger, and the film

Hamsun starring Max von Sydow. Susceptible to that pull of some works

before they’re read, or even before they’re examined as to cover or excerpt. Something’s already

known about them. The wind in the chimes produces reminders

of discrepancy, slippage in the experience of day and sidewalk. A hitch of the coat

tighter around shoulders. Threadbare shoulders of an over-worn, once stylish, other-era coat.

It’s there, in collective memory, in the Akashic records, universal archives,

accessible to the individual—also, at a glance, on Amazon. Opened

up to any from anywhere. Everything written if written

from a certain level, plane, or depth is instantly written on the inside of our skulls.

Alive, the Worm Ouroboros and the Great God Pan, neither read

in their intentions, nor known in the reality-fracture of their archetypal urges,

break through our brainpans to world. But first it’s that etching into bone

that causes the cracks. Everything written if written epic-truthfully

etches into bone. Nihilism too can get to the depth of that plane,

smirk of negation at that certain level, and the human skull splits unto nothingness.

What shapes and landscapes are these?—blind surmise of topography, shadow and

darker shadow, darkness and darker darkness going black. Going farther,

then, some such best books don’t even need to be read. Absence is more akin

to erasure than to darkness, black of night. A space widened out for the imagined book

as colorful, vague, imprecise, and fluid as dreamscape, however presumptive or wrong.

But, back to facts, there are golden ratios in the way branches divide

blue skies into networks and nodes. Networks and nodes divide blue skies

into their geometric fancies, sinuous topological methods as a branch

of geometry, fundamental properties of space over measurement and number.

Is it a stretch to find topological methods as someone looks up

through a deliquescent tree, past either budding or withering?

Any seasonal change on those branches identifies new presence just as much by absence

of what once was, that erasure, as anything there. That widened out space

to place memory and imagination. ...

...(more)

_______________________

Tuol Sleng genocide museum

photo by Ambroise Tézenas

Archives

Tom Clark

Beyond The Pale

They are, first of all, places of involuntarily remembered suffering. Time has deposited its wastes there, in the form of used-up memories no one will ever wish to have again. Still some things can't be brought to a finish so easily. No one can command time to stop, a fact in tribute to which which the Archives stand as a redundant yet palpable reminder. A smell of mildew; cobwebs that brush one's head, passing in silence from subterranean chamber to subterranean chamber. Echoes and whispers everywhere: a sudden small scurrying sound startles from behind, but nothing's there when one turns to look. We think someone's there. We think they are speaking to us. We think they are saying something to us, in muffled, disinterested, ambiguously connected half-sentences, certain strange words that are virtually indistinguishable from the silence. Yet we must strain to hear, on penalty of awaking. ...(more)

_______________________

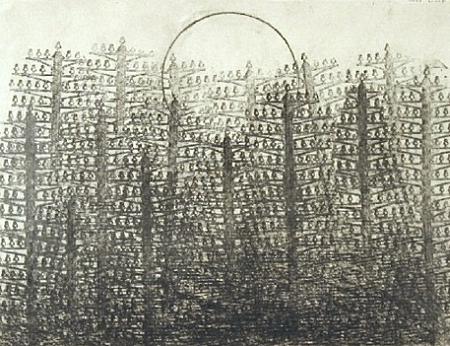

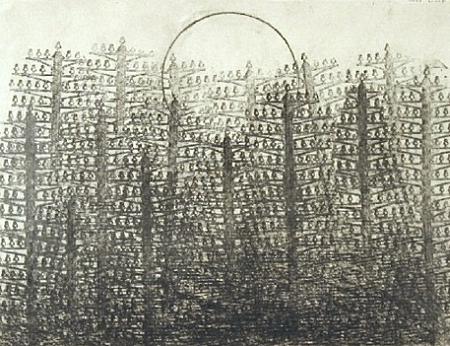

Dadaville

circa 1924

Max Ernst

(2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976)

_______________________

The Poverty of Acceleration

Virgilio A. Rivas

Kafka's Ruminations

Capitalism has actually done us a favor by cognitivizing production, so we need not imagine that much really. Our new task is to radicalize this cognitive direction to a position in which production becomes intelligent design. In this radical mode of imagination, production fuses with creation. It is philosophy coalescing with production by regressing to the present to repurpose its design. The key for a renewed philosophy though is to realize bodies outside of the design of capital which is not accelerating on behalf of bodies, rather on behalf of creation without bodies. Going back to acceleration, one has to imagine that bodies are the ones steering the speeding train, giving the value added impression that bodies are responsible for the speed as well as the upkeep of the train as it accelerates.

They in fact do except that these bodies do not realize, as the new Accelerationism proponents believe, that they are already creating the Outside to capital. They are unaware that they are philosophers. But let us remind ourselves here that once the Outside had been the privileged object of analysis of philosophy until capital stole that object, becoming philosophy itself. Capital is now turning the dream of production and limitlessness into creation as mastery of the Outside, the future. If Marx was a proponent of acceleration, as the manifesto would have us acknowledge, it is to his credit that philosophy must be abandoned, if the goal is to construct the future that capitalism has already foreclosed, in favor of real concrete actions. In an unlikely twist, Marx and capitalism can both sing and dance to the tune of, most familiar to Marxists though, the poverty of philosophy. Its poverty lies in the fact that it does not want to regress, which bespeaks of its hubris, its illusion of being progressive, revolutionary, and axiomatic. What this goes down to in the last instance is that Marx knew there is no alternative to capitalism. Philosophy would never allow itself to regress to the present to change the order of things. But if capitalism can do philosophy, philosophy can become richer by all of history’s combined wealth. And indeed, it is to Marx’s credit that philosophical capitalism will be compelled to accelerate, hence, the emancipation of bodies from their lack of purpose.

Real concrete actions may thus mean changing the way philosophy has been hitherto done. This is perhaps the original contribution of the Accelerationist Manifesto. Following Marx through its timely intervention in contemporary left politics, we can now say that the object of change is not the world vis-à-vis the many interpretations that have been made about its ontological status. Rather, it is how we can do philosophy this time (through a radical unity with bodies, or rather, production, by means of which philosophy regresses to the present which it has until now consistently avoided with its characteristic obsession with possibilities, with option contracts, least to say, under the general rubric of speculative future) which must first presuppose that the world, nonetheless, must not change, if only for philosophical creation, regressing to the present from out of the future, to catch up with the world, that is to say, the actual. Apropos of the famous last thesis of Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach, our attention draws closer to its secret: Philosophy must either imitate capitalism or become capitalism itself.

In this new light, and arguably so, labor can be emancipated. It can free itself from the illusion of the future—hope, in simple terms—for the future, once a possibility, has reached a dead-end, which is its own actuality, namely, the accelerating present. ...(more)

_______________________

Forest and Sun

Max Ernst

1931

_______________________

Paul Celan and the Meaning of Language

An Interview with Pierre Joris

(....)

I do not choose a particular manner in which to transform Celan. If I have one specific rule mind it is to stay as close as possible to the original, to remain as literal as possible in my translations of Paul Celan. So-called “free translation” or adaptation or “imitations” have most often felt like rip off to me. I.e. misusing, abusing the great dead poet to further the translating poet’s own agenda. Getting a free ride on the shoulders of a giant, so to say. Take for example Robert Lowell's “imitations:” they turn the visionary elements of a Rimbaud poem into a vehicle for Lowell’s minor neuroses. A case of inverse alchemy: gold into lead. There is no free translation just as there is no free verse. As a translator you are responsible for another poet’s work –and that's serious business.

I started translating Celan in 1968 and have kept doing so ever since. At some level it has been apprentice work: as a young poet I made the decision to apprentice myself to the man I consider the greatest European poet of the second part of the 20 century. Having shortly before that date decided to become a poet writing in English, or rather American, this work was both a way of discovering how very complex poetry works and of learning how English works at a range of prosodic levels. It also taught me something about the limits of English (or of any language). In that sense Hölderlin’s ideas on translation became important in that I felt that to carry Celan over into English I often had to do violence to English i.e. to write German in English, just as Hölderlin had written “Greek in German.” This is one of the most important aspects of translation: it has to expand, to widen the possibilities of the target language; it is not meant to simply squeeze what is squeezable from the original language into the canonical forms of that language. I hate nothing more than that supposedly laudatory phrase you usually see in a New York Times type book review, usually dismissing translation with the to me lethal compliment according to which “this book reads as if it had been written in English”.

Such translation that makes the original language disappear is an act of what I want to call an underhanded substitution, or, more theoretically, a near-Hegelian Aufhebung or sublation of the original, and corresponds to an act of colonization of the original language/culture — you could even describe it as a kidnapping, or an act of voluntary, conscious or unconscious, destruction. This we need to think about when translating into American English at this imperialist historical moment when the US is trying hegemonically to impose its political, economic & thus cultural values on a major part of the world. Ammiel Alcalay & I have been thinking for awhile now about this — wondering if translating the so-called great works or masterpieces of a foreign culture into English doesn’t simply rob them of their own cultural context… but that’s another discussion.

...(more)

FlashPoint Spring 2015, Web Issue 17

_______________________

The Hat Makes the Man

Max Ernst

|