|

Tree of Life

1988

Zao Wou-Ki

b. February 13, 1921

_______________________

Three Ogham poems from Inchmarnock with a note on poetics & translation

Gerry Loose

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

1/ Having Reached The Holy Reward

Her body fades with her hair becomes invisible her skin is a salmon.

Singing eye sings her songs together kine alpine kine grazing.

Guarded life is guarded shielded ringed with soldiers.

South from our slit ribs bees swarm north.

Now is elsewhere jealousy did this.

Thieves clean her breasts.

A bower is constructed high in the thorn.

Three fires jealousy love and death maggot us.

Under no place there are no trees there is no place.

Pulse great throbbing blooded heart harts live in her irises.

...(more)

_______________________

The Reattempt

Iris Moulton

conjunctions

I have found the edge of this place, which is to say I know how to leave: Drive east until the air gets wet and the kids are chigger bit and stained with jam, or past them until you reach the ocean. There: The water will not be what you expect, will not be the clear glimmer of just-cracked sugar, but a churn of mud and rootless vines waiting to play shark. It is nothing like here. There: The salt in the air is a polite suggestion. There: Water and earth accommodate and grow big beasts. It is nothing like here. Or drive west, past glugs of neon and pills, until you reach the ocean. Elsewhere is nothing like here, much more so than with other places. I have found the edge of this place, which is to say I have left.

...(more)

_______________________

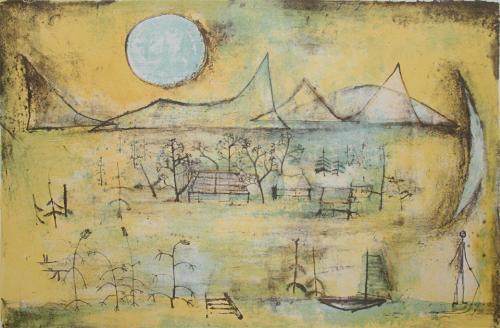

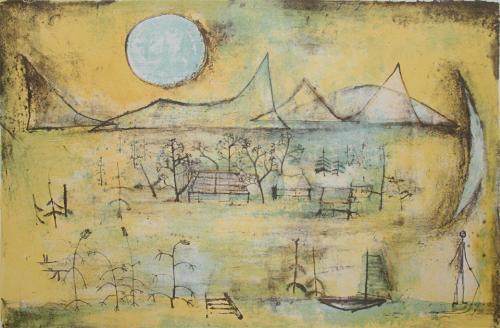

Montagnes et Soleil

Zao Wou-Ki

1951

_______________________

The Motion of Light: Celebrating Samuel R. Delany

Edited by Tracie Morris

jacket2

text versions of the presentations for “The Motion of Light: Celebrating Samuel R. Delany’s Performative Poetics”

held at University of Pennsylvania’s Kelly Writers House on April 11, 2014.

Delany on Close Listening, April 2014

(....)Bernstein: As poets we’re celebrating you here today and as was just mentioned in the toasts, you don’t write poetry — but I wonder if you could talk about the relation of genre to your work. (....)

Delany: Ah ha. “You know, you’re Black and you’re gay, do you think that working in a marginal genre makes it easier to write about those people?” To which the answer is, absolutely not. Genres don’t do the work for you. As Raymond Chandler says in one of his most popular essays in “The Simple Art of Murder,” at the beginning of his collection of the same name, “there are no vital art forms.” That is to say, there are no significant genres. There are different genres, yes. But they are not significant because they exist. He says there are no significant art forms, there’s only art, and precious little of that. And I think he was right. Which is to say, you get a good writer, or a writer who’s interested in dealing with marginal peoples and marginal situations working in whatever genre that he chooses, be it poetry, drama, science fiction, comic books — it doesn’t really matter — if they are decent workers, and they also are committed, and they have a vision that they want to put forward, then you will get good art about these things. And if they don’t have this, it doesn’t matter what the genre is, you’re going to come up with very ordinary stuff. And that’s the way I think it works.

...(more)

_______________________

Fragments for a radically negative anthropology

Toby Austin Locke

I

Anthropology must no longer determine what humanity is. It must no longer attribute qualities and characteristics to humanity. It must escape it obsession with positivity. This is the primary sense of a radically negative anthropology.

II

Anthropology must work harder to remove the mask of science(2), under the mask of Enlightenment. The very notion of a radically negative anthropology requires operating without masks, further without faciality; in the eternal return to chaos, a radically negative anthropology must operate not only without a mask but also without a face, not simply in iconoclasm, in an eternal twilight of the idols, but through processes and becomings which do not even enter into the question of idols, icons, masks or faces, processes which never become differentiated enough to not be considered undifferentiated (3).

3) Addition: it must be acknowledged that there are tendencies developing within anthropology that run along similar lines to the kind of radically negative anthropology first called for by Tiqqun. In particular we should note Eduardo Viverios de Castro’s work and his call for a “permanent decolonization of thought”; likewise Eduardo Kohn’s ‘anthropology beyond the human’ makes promising advances towards the kind of territory a radically negative anthropology might navigate. In addition, we should also point to Bruno Latour’s approach. There are of course others who are making significant contributions within and beyond the discipline itself but listing them here would be too lengthy a process. However, many of these approaches, particularly Latour’s, are not very well able to account for power and political economy. through europe

...a transeuropean and multilingual gallery of contemporary writers, a mosaic-platform of political, critical and philosophical essays, short fiction stories and art writing. _______________________

Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages

Meso-American Languages: [pdf]

An Investigation of Variety, Maintenance, and Implications for Linguistic Survival

Ransom Gladwin

The Arabic Language Fog of War: [pdf]

Exploring Iraq War Veterans’ Motivations to Study Arabic Language and Culture Post-Deployment

Dr. Jennifer Nichols

_______________________

Zao Wou-Ki

_______________________

The World of Our Grandchildren

Noam Chomsky discusses ISIS, Israel, climate change, and the kind of world future generations may inherit.

jacobin

Journey on the fish

Max Beckmann

1934

_______________________

Introduction: Maps?

Dee Morris & Stephen Voyce

jacket2

Writing has nothing to do with signifying. It has to do with surveying, mapping, even realms that are yet to come.

— Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus 4-5

The aesthetic, pedagogical, and political focus of this series of commentaries is a set of documents we call counter-maps. The term comes from critical cartographer Denis Wood, who provides a lineage that includes early twentieth-century map art, the mental maps movement of the 1960s, Indigenous and bioregional mapping, and the traditions of Parish Mapping. For Wood, “[I]t is counter-mapping that shows us where mapping is heading”.

Our contention here is that counter-maps also suggest a direction poetry may take in the digitally driven, multimedia information economy that pervades all aspects of 21st-century collective creative life. In this series of commentaries, our examples, both pre- and post-1995, come from a handful of subgenres—tactical, forensic, locative, cognitive, and ecological counter-mapping—that mix the graphic syntax of cartography, the rhythmic patterns of language, and an urgent interrogation of the processes and institutions of global capitalism.

If not always immediately identifiable as “poems,” the constructions we’ll examine are enough like poems to point to one among many futures for imaginative life. Like mainstream poems, each of these constructions brings together a specific site, a moment in time, and a motivated subjectivity; like innovative poems, they trouble the conventions of their medium to trigger new modes of thinking; and like avant-garde provocations of every kind, they are unabashedly pedagogical and political. In contrast to conventional poetic forms, however, the syntax of counter-maps—their logic, order, and arrangement—is predominantly spatial. As visual forms of knowledge production, they belong to the generative, diagrammatic, and dynamic practice Johanna Drucker calls graphesis.

...(more)

_______________________

Max Beckmann

_______________________

Jerome Rothenberg interview [pdf]

(....)

My breakthrough came in part—strangely, I think—from a poem by Gertrude

Stein, who certainly played down her jewishness (as much as any poet I

knew), but on rare occasions let it seep out. (David Antin had suggested

reading The Making of Americans as a shtetl or Jewish immigrant novel, but with the ethnic identity suppressed.) I was also immersed at the time in the

dark fiction of Isaac Bashevis Singer, whom I had met on a couple of

occasions, and the even darker poetry of Paul Celan, whom I met once and had

been the first to translate into English. And it was also a time when I was

finishing Technicians of the Sacred & immersing myself in a range of deep

cultures / deep poetries from throughout the world, to which I would add the

Jewish as another such culture for which I felt privileged to speak.

So I found myself thinking, among other things, of what a Jewish entry into

the world of experimental modernism might look like and finding it—

strangely, as I said before—in Stein. It was just a few short lines in a longer

serial poem, ‘Dates’ in Bee Time Vine, but when I read it, I thought of it

immediately as Getrude’s ‘jewish poem’:

Pass over

Pass over

Pass

Pass

Pass

Pass

to which I added a final line—‘pass water’—and then went back into the full

Stein poem and substituted a darker Jewish vocabulary from Singer’s Satan in

Goray by a kind of rhyming, word for word substitution, to make in the

process a ‘jewish poem’ of my own—the kind of multiphasic, irreverent and

knotty ‘jewish poem’ that I wanted and that really got me on the road to

Poland/1931 and, still more expansively, A Big Jewish Book, or more

narrowly, Khurbn and Gematria. It also led me to ally with others, both Jews

and non-Jews, who were also sharing in that exploration.

(....) The Wolf 31

December 2014

_______________________

Leaving the Theatre

1910

Carlo Carrà

b February 11, 1881

_______________________

Paradoxes of Materialism

larval subjects

(....)

... There is, for example, a radical difference between the lived body (the body of phenomenological experience) and the physiological (material) body. The physiological body can, of course, affect the lived body, yet the lived body is no reliable guide to the material or physiological body.

A man suffers from severe anxiety. His thought spins, exploring, in a Heideggerian fashion, the meaning of his existence, his relation to death, the being of being. He thinks these are the sources of his anxiety and goes to a psychoanalyst or an existential therapist. Yet perhaps his anxiety is merely a chemical imbalance. From within experience there’s no way to know, for his material being is exterior to all thought and experience. The relation of meaning to anxiety seems absolutely self-evident. He spends years in therapy. Yet the ground of his anxiety was, in this instance, never in the domain of matter. There’s a strange way in which the material body, that which is closest to us, is more exterior than the greatest exteriority– even the exteriority of the so-called Levinasian Other –such that while we are it it is nonetheless completely opaque.

...(more)

_______________________

Stil LIfe with Two Large Candles

1947

Max Beckmann

b. February 12, 1884

_______________________

What the Sharing Economy Takes

Uber and Airbnb monetize the desperation of people in the post-crisis economy while sounding generous—and evoke a fantasy of community in an atomized population.

Doug Henwood

_______________________

Uber’s Business Model Could Change Your Work

Farhad Manjoo

You may not be contemplating becoming an Uber driver any time soon, but the Uberization of work may soon be coming to your chosen profession.

Gustav Wentzel

(7 October 1859 - 10 February 1927)

_______________________

Didactic Elegy

Ben Lerner

lemon hound

Sense that sees itself is spirit.

—Novalis

1.

Intention draws a bold, black line across an otherwise white field.

Speculation establishes gradations of darkness

where there are none, allowing the critic to posit narrative time.

I posit the critic to distance myself from intention, a despicable affect.

Yet intention is necessary if the field is to be understood as an economy.

By ‘economy’ I mean that the field is apprehension in its idle form.

The eye constitutes any disturbance in the field as an object.

This is the grammatical function of the eye. To distinguish between objects,

the eye assigns value where there is none.

When there is only one object the eye is anxious.

Anxiety here is comic; it provokes amusement in the body.

The critic experiences amusement as a financial return.

It is easy to apply a continuous black mark to the surface of a primed canvas.

It is difficult to perceive the marks without assigning them value.

The critic argues that this difficulty itself is the subject of the drawing.

Perhaps, but to speak here of a subject is to risk affirming

intention where there is none.

It is no argument that the critic knows the artist personally.

Even if the artist is a known quantity, interpretation is an open struggle.

An artwork aware of this struggle is charged with negativity.

And yet naming negativity destroys it.

Can this process be made the subject of a poem?

No,

but it can be made the object of a poem.

Just as the violation of the line amplifies the whiteness of the field,

so a poem can seek out a figure of its own impossibility.

But when the meaning of such a figure becomes fixed, it is a mere positivity.

...(more)

_______________________

Schoolyard,

1926

Wilhelm Thöny

b. February 10, 1888

_______________________

Samuel Beckett, Letter 9 July 1937

presented at flowerville

(....)

Or is literature alone to be left behind on that old, foul road long ago abandoned by music and painting? Is there something paralysingly sacred contained within the unnature of the word that does not belong to the elements of the other arts? Is there any reason why that terrifyingly arbitrary materiality of the word surface should not be dissolved, as for example the sound surface of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony is devoured by huge black pauses, so that for pages on end we cannot perceive it as other than a dizzying path of sounds connecting unfathomable chasms of silence? An answer is requested.

I know there are people, sensitive and intelligent people, for whom there is no lack of silence. I cannot help but assume that they are hard of hearing. For in the forest of symbols that are no symbols, the birds of interpretation, that is no interpretation.

Of course, for the time being, one makes do with little. At first, it can only be a matter of somehow inventing a method of verbally demonstrating this scornful attitude vis-a-vis the word. In this dissonance of instrument and usage perhaps one will already be able to sense a whispering of the end-music, or of the silence underlying all.

...(more)

_______________________

Possession with Broken Wing

1989

Fritz Scholder

d. February 10, 2005

_______________________

Three Poems

Kiwao Nomura

translated from the Japanese by Kyoko Yoshida and Forrest Gander

alligatorzineEyeground Road

who are we,

although this sounds like a riddle,

whose work it is to trek all night,

around your eye-grounds,

on the roadside,

where afterimages of the stupid things you do by day,

are scanned and read on the soles of our feet,

such pleasure,

but in the depths of the eye-ground,

this may sound like a bad pun,

your agonies crystallize into pieces of agates that dot the road,

we pick them up and click them against each other,

to photograph the scattering sparks,

and send them to you in dreams,

what pleasure,

what a pleasure,

naturally,

when morning breaks at last,

we silently withdraw,

this may sound like a riddle,

but what are we,

for you,

...(more)

_______________________

Gustav Wentzel

_______________________

Five Histories of Western Philosophy

Daniel Grandbois

Bertrand Russell finds himself in purgatory, tumbling through literal representations of the worlds of ideas he examined in his classic text, A History of Western Philosophy, gulping much-needed air, for example, from Empedocles’ bucket. Mistaking his erection for a planted flag, he declares the place Platonopolis, attempts to calculate his Pythagorean number, kills God (though he later sees evidence of His resurrection), and, Rousseau-like, turns away from reason and civilization, favoring the noble savage, only to march back into the concrete jungle as one of Nietzsche’s savage nobles. In the end, however, he is all jumbled up and clucking like Einstein’s cuckoo clock, until he perceives philosophy as music, hears its arguments as a symphonic procession of the electrochemical pulses produced within three-pound lumps—lumps self-amalgamated from the vomitus of stars—and revises his History.

...(more)

Snow

1999

Photo Paintings

Gerhard Richter

b. February 9, 1932

_______________________

Selections from Nude Day (The Day Laid Bare)

Kiwao Nomura

(Translation by Eric Selland)

big bridge

Parade 6

Kiwao Nomura

(Translation by Eric Selland)

Look - it's happening again

Humans possessed

By actions

Oh merciful Buddha (The collarbone snaps)

One continues to practice self-restraint

I whisper to you, the winter of your skin exfoliates

Look -

Another parade. The Twenty-ninth Flesh comes into view. Its peculiar mode of

existence is like the hallucinations when some bad stuff kicks in. That's how much it

shakes its head as if it had been severed, twirling around in an absurd dance. If you ever

manage to capture it, you will notice a strong smell of citrus.

Shaking its head as if it had been severed

(Read the writing on the wall Japan)

The Thirtieth Flesh is a balloon swollen with the ashes of existence, or the carrier of

ardor's return. When desire is fulfilled it flattens, and then waits for more ashes. It will

wait years if necessary.

And at the far end of its ordeal

Yet again it sucks, sucks and absorbs

The Thirty-first Flesh unfolds its solitude like fins at rest. Radiating outward, with

delicacy; to pursue or be pursued; such concepts simply rain down like marine snow.

Before talking about The Thirty-second Flesh it's back down memory lane - the

movie Alien, nostalgiasville! My precious little alien, shuffling around the attic, carrying

off grandmother and the others, spinning them into cocoons...

Things have cleared up now, for us and the ground also

The egg and loneliness, an IV and a gag

See, it's all clear

The day laid bare

Because it is equal to the fate of the breast

...(more)

Big Bridge 17

_______________________

St. Moritz

Gerhard Richter

1993

_______________________

Diane Raffman is the deft philosophical flautist of vagueness. She thinks hard about vague words and their fuzziness, about supervaluationist approaches to the paradoxes, about judgemental hysteresis, about contextualism and why she changed her mind, about borderline cases, about not sacrificing bivalence, about why she thinks blue but not 'not blue' has borderline cases, about her multiple range theory, about changing the way philosophers have understood vagueness and about the epistemic theories of Williamson and Sorensen. This one you have to read before drawing a line…

unruly words

Interview Richard Marshall interviews Diane Raffman 3am

(....)

I decided that I couldn't plausibly incorporate the psychological aspects of my contextualist view in the semantics of vague words in the way I had originally envisioned. I now take those psychological aspects to be features of the competent use of vague words, as distinct from their semantics strictly speaking. In addition, I came to see that the distinctive variability of application of a vague expression does not result from any sensitivity to context. Although most if not all vague terms are context-sensitive, their context-sensitivity is not essential to their vagueness. Rather, what's essential is their possession of multiple equally permissible ways of being applied (multiple permissible "ranges of application"). So the multiple range theory is not a contextualist theory of vagueness.

...(more)

Unruly Words: A Study of Vague Language

Diana Raffman

_______________________

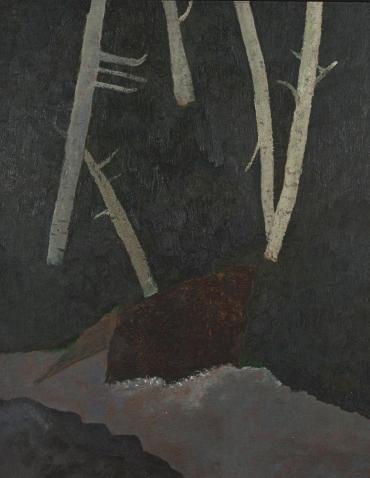

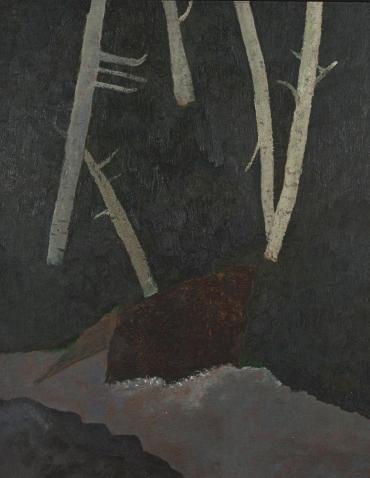

Waldstück

Forest Piece

Gerhard Richter

1965

_______________________

Threepenny Review

Issue 140, Winter 2015

Thirty-Fifth Anniversary Issue

Who Is It?

David Ferry

Here inside this fiction of myself,

Two voices I always hear, both of them mine,

I guess, one of them telling the truth, I guess.

I don’t know which one it is that’s telling the truth,

The voice that said what it was it had to say

And heard what it said when it said it, and didn’t know

Exactly what had become of the person who said

What it was he said, just now, to tell the truth.

...(more)

_______________________

Ghost River

Will Hunt

Paris Review

Not long ago, I read an article about archaeologists in Greenland who discovered that plants growing above an ancient Norse ruin possessed slightly different chemistry from plants growing nearby. I was taken with the idea that the energy of a forgotten structure, invisible and buried deep underground, may percolate upwards to leave subtle impressions on the surface. It was this that came to mind recently when I discovered Minetta Brook, a hidden stream that flows beneath the streets of Greenwich Village.

...(more)

via Forgottenness

_______________________

Vierwaldstätter See

Gerhard Richter

1969

_______________________

Site of Doppos’s Lodge, sections 6-9

Kiwao Nomura

Translated by Kyoko Yoshida; Forrest Gander

center for the art of tranlation

(....)

7 (molto contabile)

Infinitely there

to be traced by branching fingers

a throng of place-names

there/ infinitely

there.

As for instance a rockslide serpentines/ in the distance silently serpentines/ glimpse of brute geometry serpentines/ spilling its slough into a river/ spilling its slough into a river /the river narrowing the river dipping under/ the city’s edge and depth the green/ Midori enviously stretches out forever

Infinitely there, infinitely

there though surpassed

and infinitely inaccessible/ there

a throng of place-names

apprehension delineates

flocks of feathery footprints dancing

in flocks.

Or as if foam were stitched together

what reverberations/ what

but the sound of phantom snowdust

in the distance a rockslide serpentines

Midori enviously stretches out

along the curve of spine not willowy enough

to sidestep

there/ or there

to be given the slip.

And yet another flock of footprints

molto cantabile

furioso

or molto funebre.

...(more)

Spectacle & Pigsty Kiwao Nomura Kyoko Yoshida (Translator), Forrest Gander (Translator) amazon link

Hard to Be a God

Alexei German

full movie - youtube

_______________________

The Dark Master of Russian Film

Gabriel Winslow-Yost on Alexei German's Hard to Be a God

“The Renaissance didn’t happen here,” the voice-over declares, in the opening minutes of Alexei German’s Hard to Be a God. In this final film of his career—now receiving a belated American release at Anthology Film Archives in New York—the late Russian filmmaker immerses us, without respite, for nearly three hours, in his reimagined Middle Ages. I don’t think any film has ever depicted a world so awful with such conviction.

(....)

German works in crisp black and white with long, incredibly elaborate tracking shots—as hypnotic and as beautifully choreographed as anything in Tarkovsky or Bela Tarr, but chaotic, even antic in a way theirs never are. The camera peers around corners, through windows, down darkened hallways; people lurch in front, blocking its view or suddenly making eye contact with it, demanding to be seen. Spears threaten bare buttocks, corpses are looted, mocked, kicked aside, faces are smeared with unidentifiable muck, the rain pours down. The screen is alive with textures: of spoiling meat, dirty feet, sodden leather, the glaring white of a clean fur coat on a nobleman. At times we seem to be caught up in some madcap pageant of degradation that started long before the camera was turned on, and will continue long after the reel runs out. But then there will be a moment of quiet, or sudden beauty: in the midst of an especially elaborate indoor journey, Rumata opens a doorway and pauses before he steps into the darkness—and an owl flies out and lands on his shoulder.

...(more)

_______________________

Hard to Be a God

_______________________

On Snow

Stefany Anne Golberg

the smart set

(....)

Snow is a substance that seems to have no immediate purpose. Is it a symptom or a cause? Is it living or dead? Is it an element? A force? Winter, in the Northeast of America at least, is the season of absence. It is the Great Undoing. Poets who live with four seasons often like to use winter as a metaphor for death, as in Longfellow’s “Snow-flakes.”

But for anyone who has watched the tree outside the window being stripped of its clothes, watched the garden that took so many months to grow waste away for lack of sun, watched the wasps suddenly, one morning, leave, winter is no metaphor — everything smelling of life shrivels until the last green thing is dead, icicles shoot up from the ground, changing the meadow to crust.

We accept the winter only because we have accepted the idea that death has a purpose: to make way for new life on Earth. We’ve been told from the beginning that life requires death, feeds upon it, needs our names for its young. This is the thought that makes winter bearable. We will spend months in abeyance, living in a void, standing by powerless at the retreat of our green soldiers as the army of cold advances, simply for the promise of a hint of a message that, one day, our soldiers will return. “So we wait,” wrote Rita Dove, “breeding / mood, making music / of decline. We sit down / in the smell of the past … We ache in secret, / memorizing / a gloomy line / or two of German.”

...(more)

_______________________

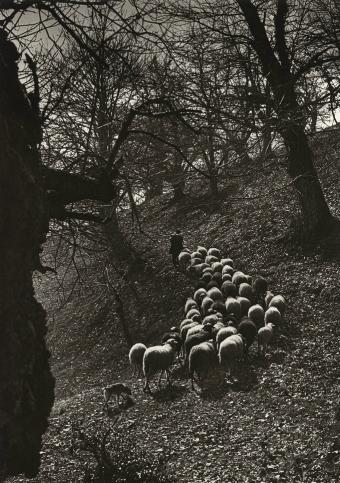

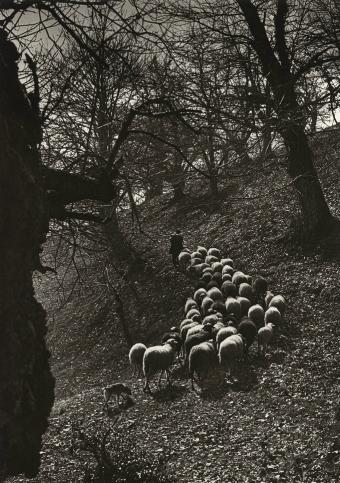

Le chapeau de mariage de mon père

1975

Jean Dieuzaide

1921 - 2003

_______________________

Déjà Vu and the End of History

Paolo Virno

(....)

The phenomenon of “false recognition” allows us to decipher critically the fundamental idea of every philosophy of history: the end, the exhaustion, or the implosion of history itself. Above all, it allows us to settle accounts with the contemporary—that is, “postmodern”—version of this idea, which descends from a noble lineage and complicated family tree. According to Baudrillard and his miniature disciples, history thins out to the point of vanishing when the millenarian aspiration to wipe out the duration of time (and, with this, any irritating delays) appears to have been satisfied by the instantaneousness of information, real-time communications, and by the desire to lay “hold of things almost before they have taken place.” And yet the affirmation of an eternal present, a centripetal and despotic actuality, is provoked by déjà vu, namely by the form of experience in which there prevails—as Bergson put it—“the feeling that the future is closed, that the situation is detached from everything although I am attached to it.” In capricious, rampant years of history, Karl Mannheim prophesied:

It is possible … that in the future, in a world in which there is never anything new, in which all is finished and each moment a repetition of the past, there can exist a condition in which thought is utterly devoid of all ideological and utopian elements.

A posthistorical situation, then; but also, at the same time, a condition marked by the mnestic pathology of which we have already spoken: “there is never anything new … each moment [is] a repetition of the past.”

Now, however, we need to interrupt this game of assonances and analogies. To understand the increasing fragility of historical experience and, at the same time, to refute the mediocre ideologies that set up camp on this terrain, it is necessary to observe more closely the actual texture of “false recognition.” What clay is a memory of the present made of? How is it formed? What does it reveal?

...(more)

e-flux journal issue 62

_______________________

Jean Dieuzaide

_______________________

A Decent Interval

Greg Siegel

cabinet

How long does a building stand before it falls?

How long does a contract last? How long will brothers share the inheritance before they quarrel?

How long does hatred, for that matter, last?

Time after time the river has risen and flooded.

The insect leaves the cocoon to live but a minute.

How long is the eye able to look at the sun?

From the very beginning nothing at all has lasted.

—Gilgamesh (....)

If the Leaning Tower of Pisa Experiment is indeed apocryphal, its legend nevertheless remains inextinguishable, its allure undeniable, its mythic resonance irrepressible. For, in the parable of the heretically empirical mathematician and his physically impossible spheres, modern science’s allegedly decisive break with Aristotelian dogma—a defining “epistemological rupture,” as Gaston Bachelard would have it—finds perhaps its most condensed and compelling expression, the perfect pregnant moment.

How curious, then, that this moment of supreme scientific rectitude, of manifest epistemic rightness and correctness, in which reason and nature finally came into proper alignment, should seem to have been destined to take place atop such a deviant structure, against such a crooked backdrop. What a strange accident of history or of mythology that the Tuscan city’s infamous engineering failure—its accidentally inclined bell tower, built on church grounds and so, presumably, under divine auspices (the eyes of holy infallibility)—served as the stage for this famous achievement of early experimental science, as the platform for this faultless performance of epoch-making truth.

Galileo may have succeeded, on that fateful day at the Pisan campanile, in forever closing a certain postulated interval. But the question concerning a different interval, one that likewise pertained to the nature of falling bodies as a function of time, remained disconcertingly open. When will the Leaning Tower collapse? No one in those days, no artist or architect, no physicist or philosopher, not even Galileo, knew with any degree of certainty how long the building could stand up, how long its tilted frame could withstand the planet’s tremendous, relentless pull. Longer than brotherly love lasts? Longer than the floodwaters linger? Longer than the silkworm lives? Longer than a man can look at the sun? No one knew exactly when the accident of gravity would come (the grave accident, the serious accident, the heavy accident, but also the gravid accident: another pregnant moment).

...(more)

_______________________

Jean Dieuzaide

Winter

1961

Norman Bluhm

d. February 3, 1999

_______________________

Poetry and Stuff: A Review of #!

Nick Montfort

reviewed by John Cayley

electronic book review

At long last, an electronic book for review! Its title—the beginning of a script—is shebang!—hashbang, pound-bang, hash-exclam, hash-pling! This conjunction of two special characters—ancient in the annals of computation—indicates the beginning of a more or less extended statement, a program, in an all but universal language of programmatology, in the special dialect of the command line. Scripts addressed to the Unix operating system begin with these two characters. They inform other programmers and they tell the system—to all human intents and purposes they tell our computational familiars and prosthetics—that what follows is also, if not primarily, addressed to a machine. If we, as human readers, happen to recognize this compound symbol of power in the universal language of Unix and if we are able to interpret the lines that follow it as code, then we may well be able to understand and anticipate what it is that the script or program promises to do and say. Nonetheless, what follows shebang is chiefly meant to be read by the system, as a program, as a list of commands that will generate a performance, an inscription, an output.

(....)

One answer might be to say that they are instances of electronic literature, electronic poetry. At long last, an electronic book for review! Well, the book is obviously not “electronic.” It’s a printed book. But, by contrast with the vast majority of work that is given the label “electronic literature,” the work in Montfort’s #! is, arguably, worthy of such a designation. Most of what currently comes under the dominion of electronic literature is (time-based) concrete poetry, (time-based) visual poetry and prose, affective audiovisuality constructed with unread or unreadable linguistic material, (more or less conventional) literature illustrated by computationally rendered audiovisual media, (more or less conventional) literature navigated by computational affordances, and so on. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list and there is no intention to denigrate these vital, new—and highly divergent—literary practices. I’m simply suggesting, as I have before, that it is difficult to understand the “electronic” of “electronic literature” and that it might be better to reserve the term for specific varieties of literary practices—like Montfort’s—in which the technical and computational is constitutive, rather than instrumental or decorative (Cayley, “Weapons”). My point relates to the sense that “electronic literature” was coined by analogy with “electronic music.” The latter is now established, solidly instituted—and we are comfortable with its usage in English. We bracket our understanding that, as an artistic medium, electronic music is not electronic: it’s organized sound: abstract, aestheticized aurality. “Electronic” renders the phrase metonymic by referring to technologies that, typically, are designed to produce “electronic music.” In the case of “electronic literature,” these technologies—unless we are to comprehend bespoke electronic voice synthesis, for example—are all, in fact, computational, programmable media. In #! the technologies appropriate to Montfort’s work are deliberately set aside, allowing both programs and samples of generated, virtual language to gain focus and subject themselves to human reading.

...(more)

_______________________

Mathematics

Norman Bluhm

1962

_______________________

the stuff of proof

Penelope Maddy interviewed by Richard Marshall

3am

(....)

The idea that mathematical decisions of the sort I’ve been talking about — evaluating axioms, for example — are really aesthetic judgments is a popular one, but I confess I find it unhelpful. First off, we don’t understand aesthetic judgments very well, so it wouldn’t be a clear gain even if it were true. But more importantly, it doesn’t seem to me that the mathematical judgments we’re considering are of the same sort, or of a sort analogous to, aesthetic judgments. Something makes the axiom of measurable cardinals a good candidate, but I don’t think it has much to do with what makes a Cezanne’s landscape a great painting, or Beckett’s ‘Happy days’ a great play, or Trollope’s Last Chronicle of Barset a great novel, or Cunningham’s ‘Points in Space’ a great dance. (For that matter, I’m not even sure how much there is in common between the painting, the play, the novel and the dance.)

So, for example, one of the extrinsic considerations in favor of measurable cardinals is that their existence implies the existence of a very special set of natural numbers called 0#, and this set of natural numbers helps us see in great detail how it is that Gödel’s minimal universe goes wrong. You might try to see this as something that could also apply to paintings and novels, but I’d wager than in doing so, you’d have to loosen it up so much that you’d lose the mathematical texture that gives this extrinsic justification its force. Wittgenstein once said that if you wrap tables, chairs, and cupboards in enough paper, they’ll all look spherical — the point being that you can make them all seem the same, but you lose what’s important about them in the process.

I think what’s happening here is that it’s so hard to understand what’s going on in mathematics that we grope around for an analogy: math is like science, math is like a game, math is like fiction, math is like art. One conviction I’ve developed over the years is that in the end, these analogies aren’t going to help: the only way to understand what’s going on in mathematics is to buckle down and look at the mathematics itself, at how it’s done and why.

...(more)

_______________________

Still Life

Norman Bluhm

1948

_______________________

Otoliths issue thirty-six

southern summer, 2015

Editor: Mark Young

Coney Island

1945

Theodoros Stamos

d. February 2, 1997

_______________________

Terrorists Speak in Strange Languages

Asef Hossaini

translated from the Persian Dari by Farzana Marie

guernica

Time burst and we emerged

to begin our lives,

we tied our shoes and ran away.

The street was full of worried eyes,

we

were full of the street—

our hands have been cobblestoned

and our heart valves opened

like cheap cabarets.

(....)

My darling,

the weather is cold

and many babies are being aborted

and we,

standing in a line

of one hundred and twenty thousand prophets

are still thirsty, still hungry…but we voted.

We cannot change the world,

sing songs, and be happy;

just let me squeeze the map

into the space of a cage

so that our lands will mate.

The police say: terrorists

speak in strange languages.

I lock my tongue

even though I’ve prayed

in Persian for a thousand years.

In solitary confinement

I continually confess

and at night

when I stretch out my bones in the corner

I pray your name

seventy two times and no more.

You sit in far-off longing

and all of my roads to your arms

are blocked today

—They say an explosion happened out your way—

Do you remember

Venice, where the Mediterranean came up

and pulled your ankle to the ocean?

I said: this is enough for the sea fairies

to find their lost way.

You laughed, what a pity

how quickly we have been lost.

My longing is so deep

that three hundred and sixty five miners

have died in it.

...(more)

_______________________

The Sacrifice

Theodoros Stamos

1946

_______________________

Clinical Psychology, Psychological Science, and Neo-liberal Times

Jeremy Safran

public seminar

(....)

... many of detrimental consequences of psychology’s identification with certain features of the natural sciences are subtler in nature. Building on Foucault’s writing on governmentality, British sociologist, Nikolas Rose has published a series of books outlining the way in which psychology and affiliated disciplines (referred to generically by Rose as the psy disciplines) have come to play a central organizing role in our culture by contributing toward the construction of a particular form of subjectivity — the psychological self. The contemporary psychological self organizes subjectivity in a way that internalizes the principles of a neo-liberal culture, so that we all engage in a form of self-governance that perpetuates an advanced capitalist consumer culture, and maintains a power structure that privileges the wealthy elite at the expense of a growing proportion of the population that is disadvantaged. Consistent with Foucault’s general analysis of the way power operates in society, this model does not posit the existence of an active conspiracy of the elite. Instead it involves a self-perpetuating intersection of cultural, sociological and psychological forces that lead to the shaping of a particular from of subjectivity through the implementation of what Foucault terms, technologies of the self — principles of self-regulation and self-construction derived from our psychological culture that lead to the production of ourselves as commodities in a consumer culture.

The contemporary self is autonomous, agentic, and capable of making and breaking emotional bonds easily (What Zygmunt Bauman refers to as liquid love). We are predisposed toward looking inward for the source of our problems and have learned to regulate emotional expression in order to get along with others in the workplace. Problems in living are understood as stemming from personal failures or chemical imbalances, rather than as reflecting social and cultural problems. People have become increasingly accustomed to viewing themselves as commodities in the social marketplace. Happiness and contentment become goals in and of themselves, rather than byproducts of a life that is well lived. Therapists, life coaches and self-help books offer a range of different prescriptions for achieving happiness, and if psychotherapy is viewed as too ambiguous or labor intensive, mood enhancing prescription medications are readily available. These psychotropic medications are marketed to the public on television, just like cereals, shampoo, deodorant and mouthwash. Both Prozac and personal hygiene products hold out the promise of transforming the self into a more marketable commodity.

...(more)

_______________________

Social Media Is Not Self-Expression

Rob Horning

1. Subjectivation is not a flowering of autonomy and freedom; it’s the end product of procedures that train an individual in compliance and docility. One accepts structuring codes in exchange for an internal psychic coherence. Becoming yourself is not a growth process but a surrender of possibilities that we learn to regard as egregious, unbecoming. “Being yourself” is inherently limiting. It is liberatory only in the sense of freeing one temporarily from existential doubts. (Not a small thing!) So the social order is protected not by preventing “self-expression” and identity formation but encouraging it as a way of forcing people to limit and discipline themselves — to take responsibility for building and cleaning their own cage. Thus, the dissemination of social-media platforms becomes a flexible tool for social control. The more that individuals express through these codified, networked, formatted means to construct a “personal brand” identity, the more they self-assimilate, adopting the incentive structures of capitalist social order as their own. (The machinations of Big Data make this more obvious. The more data you supply, the more the algorithms can determine your reality.) Expunge the seriality built into these platforms, embrace a more radical form of difference.

...(more)

_______________________

Ancient Land

Theodoros Stamos

1947

_______________________

Book of forgotten dreams

Stephen Mitchelmore on Georges Bataille's book La Peinture Préhistorique: Lascaux ou la naissance de l'art

(....)

"What transfixes us is the vision, present before our very eyes, of all that is most remote. Of our presence in the real world."

The paradox in the words of the caption that being close to ourselves in proximity to what is most remote is explained here as the "strong and intimate emotion" of religion or, better, "the sacred", to which the cave paintings are "more solidly attached to than it has ever been since". This is not religion as one more additional theory but as the catalyst of humankind, when the creature wandering the icy plains descended into the caves and, in the remove of darkness and solitude, set itself apart from the animal kingdom and discovered itself, codifying the cosmos with paint. As Richard White puts it, this is "not the sacred as the beyond, another realm of being that exists in opposition to this one—but the sacred as the deep reality of this life that we are typically alienated from". So we shouldn't include these moments perusing the book with the usual "Oh I like that" pleasures of the art gallery but as the kindling of the effects of art was it when born; that is, when we were born, perhaps the deeper feeling we have in galleries we have since been socialised to restrain. Whatever, the miracle is foundational.

Bataille says that in looking at the cave paintings in Lascaux "we are left painfully in suspense by this incomparable beauty and the sympathy it awakens in us", and something close to this is what I experience looking at the book, if this can be called an experience. One is not transported in awe towards fantastical otherness but toward a fog-bound interior, as comforting as it is alien. "It is as though paradoxically our essential self clung to the nostalgia of attaining what our reasoning self had judged unattainable, impossible." This is where I ask: what can be done with this suspense and sympathy if our reasoning self is how we measure experience?

...(more)

Bataille on Lascaux and the Origins of Art

Richard White janus head

_______________________

The Rock

Theodoros Stamos

1944

|