|

Matin

1900

John Duncan Fergusson

d. January 30, 1961

_______________________

Wislawa Szymborska: Utopia

translated by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh

presented by Tom Clark

Island where it all becomes clear

solid ground beneath your feet

.. the only roads are those that offer access

bushes bend beneath the weight of proofs

the tree of valid supposition grows here

with branches disentangled since time immemorial

.. the tree of understanding, dazzlingly straight and simple

.. sprouts by the spring called now I get it

the thicker the woods, the vaster the vista

the valley of obviously

...(more)

_______________________

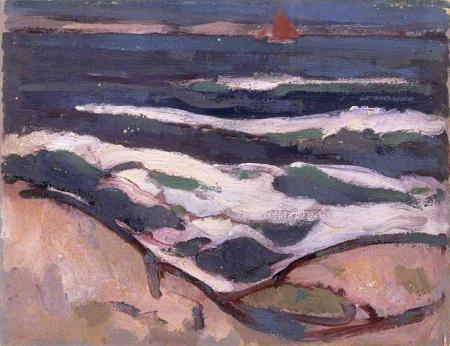

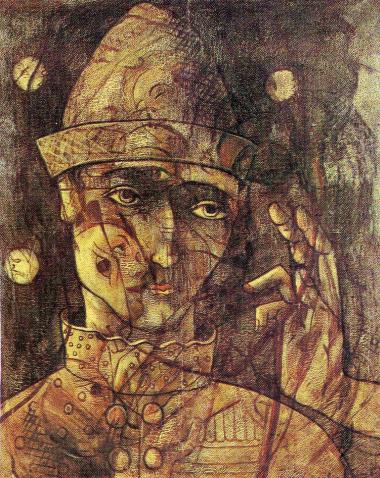

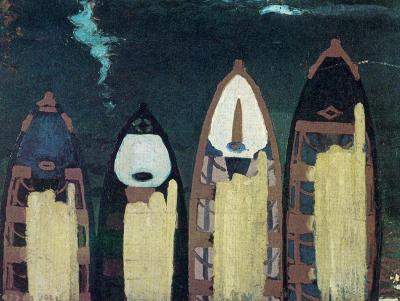

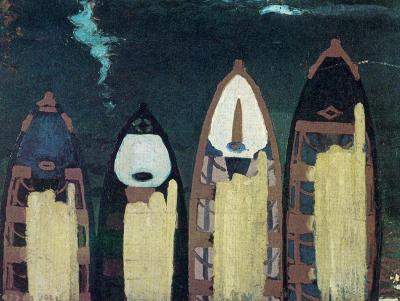

Dark Sea and Red Sail

John Duncan Fergusson

1909

_______________________

As all children know, truth

Dan Disney

as all children know, truth is a snake eating its own tail

while householders whinny ethics across dining rooms of thought

and this might be the last thing that can be said

for any generalissimo inside a Behavior Army

critical-eyed amid the jaunty peasant societies (little shops, storytelling, pigs,

perhaps a bench)

and as all children know, truth is self-polishing, a bust of bronze

shining a slew of reality across ancestral paths

where the dead pick turnips, shake-boned to narratives arriving by cartload

and this might be the last thing that can be said

...(more)

Southword Issue 27

_______________________

Walter Benjamin’s Voice

David Beer reviews Radio Benjamin, by Walter Benjamin, edited by Lecia Rosenthal

berfois

Writing at sometime around 1930 or 1931, Walter Benjamin suggested that the voice on the radio is a like a visitor in the home, as such it is “assessed just as quickly and sharply” as any other houseguest. Unfortunately, as far as we are aware, there are no existing audio tapes with which to assess our sympathies for Walter Benjamin’s radio voice. Yet the newly translated collection of the scripts from his various radio broadcasts, gathered in the recently published volume Radio Benjamin, provides us with some insights into what he might have sounded like.

There is an undoubtable audio texture to these printed passages, the grain of his voice and the style of his speech find their way into the prose. But this selection of his radio outputs does more than simply allow us to listen to his imagined voice; these pieces also reveal something of his writing, his working practices and the emergence and formation of some of his key ideas. Far from being an unwelcome and maybe even annoying distraction from his work, as Benjamin himself would have us believe, it would seem, that these broadcasts became an important part of the development of his thinking and writing (as has been briefly suggested by Gilloch, 2002: 170 and Brodersen, 1996: 193).

These radio pieces, which are beautiful in their imagery and telling in their scope, simply attest too much care and attention for them to be considered insignificant or disposable. ...(more)

_______________________

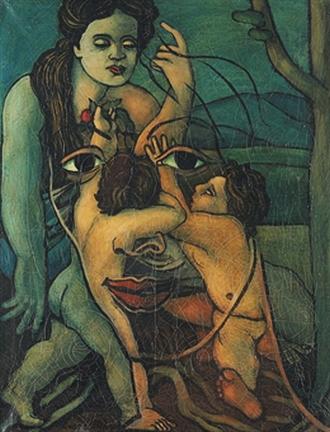

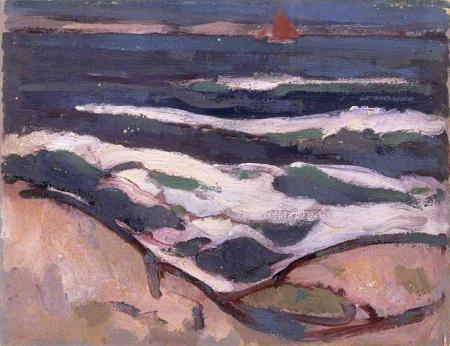

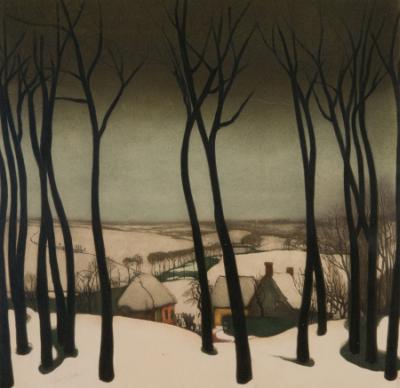

Soir

John Duncan Fergusson

1900

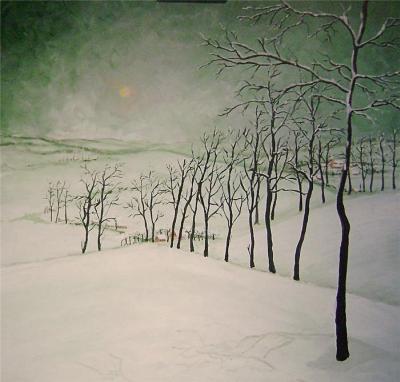

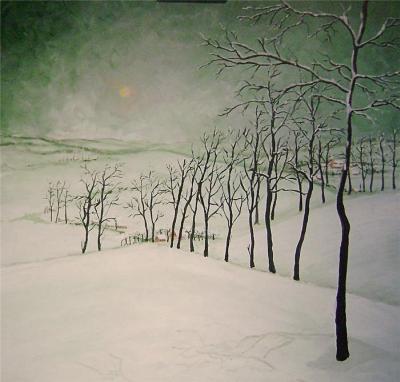

Cold

Chen Jiagang

_______________________

Schrödinger's Cat

Ursula K. Le Guin

As things appear to be coming to some sort of climax, I have withdrawn to this place. It is cooler here, and nothing moves fast.

On the way here I met a married couple who were coming apart. She had pretty well gone to pieces, but he seemed, at first glance, quite hearty. While he was telling me that he had no hormones of any kind, she pulled herself together and, by supporting her head in the crook of her right knee and hopping on the toes of her right foot, approached us shouting, "Well what's wrong with a person trying to express themselves?" The left leg, the arms, and the trunk, which had remained lying in the heap, twitched and jerked in sympathy. "Great legs," the husband pointed out, looking at the slim ankle. "My wife had great legs."

A cat has arrived interrupting my narrative. It is a striped yellow tom with white chest and paws. He has long whiskers and yellow eyes. I never noticed before that cats had whiskers above their eyes; is that normal? There is no way to tell. As he has gone to sleep on my knee, I shall proceed.

Where?

Nowhere, evidently. Yet the impulse to narrate remains. ...(more)

via Biblioklept

_______________________

Language, Media and Politics

Giorgio Agamben

2011

European Graduate School Video Lectures

_______________________

european marks

Kirill Kobrin

Translated from Russian by Katya Luc

3am

We were driving from Kirkenes to the museum of Skolt Sami, which is situated near the Finnish border. There were three of us in the car, Andreas (German) was driving, I was sitting next to him in the passenger seat, and in the back sat Jasmina (Serbian). Andreas is the art director of the group of the curators “Pikene på Broen” and Jasmina is in charge of contemporary culture in the administration of the northern Norwegian town Tromsø . For me this was the third time I have come to Kirkenes in the last two years to try to understand the essence of this place, as it is situated between two borders, and in many ways becomes a border in itself. What a “border” constitutes is exactly what will be discussed here.

...(more)

_______________________

Searching

Chen Jiagang

_______________________

Why translate?

Herbert Lomas

books from Finland

(....)

To translate is to put on a mask and to find a self you did not know you might have. It’s generally a pleasurable experience. You have the pleasure of writing without the agony of primary invention. It’s like reading, only more so. It’s like writing, only less so.

I first began to translate in a purely amateur way, for pleasure. I was intuitively reaching for the experiences I’ve just been describing – wanting to find my own Finnish personality, wanting to see what the Finnish author would be like if he were an Englishman or woman. Well – up to a point: what kind of a personality emerges in this exercise? Actually something quite new something that would otherwise not exist. In these solitary theatricals one actually does become creative: it’s not merely a job of transposition. It’s a job of invention: in each poem you have to invent a new personality.

(....)

What I’m suggesting is that people read to experience themselves imaginatively: they want a new perspective on their own lives. People do not read translations to encourage minor literatures but to rediscover themselves in new imaginative adventures and revealing extensions of experience. If books from other cultures are to succeed in translation, it will not so much be because of their local colour, but because the problems and anxieties that the readers are experiencing in their own lives are illuminatingly developed in these translations too.

...(more)

_______________________

Chen Jiagang

_______________________

Antonio Gamoneda and the ontology of disappearance

A review of 'Description of the Lie' and 'Gravestones'

Jose-Luis Moctezuma

jacket2

Rust is the color of disappearance, the deintensification of metallic solidity. Seen in a different slant of light, rust produces a reintensification of color in the meeting of iron and oxygen, the proliferation of autumn in a congeries of breath, moisture, and steel. On the tongue rust acquires a taste: the bitterness of a disappearance, an evaporation that leaves behind the strange piquancy of material erosion. In Antonio Gamoneda’s Description of the Lie, rust invokes the beginning of a precipitous, painful knowledge, a forgetting that paradoxically initiates a splintering of presence into prismatic refractions that call attention to time’s invisible phenomena:

Rust alighted on my tongue with the taste of a disappearance.

Forgetting penetrated my tongue and I had no recourse but to forget,

and I accepted no value other than impossibility.

Rust in this sense leaves a taste of forgetting, or the sight of “a calcified boat in a country from which the sea has receded,” leaving only the impossibility of a sea, a lost remembrance contained in the sight of cuttlefish bones and striated canyon walls, a place evidenced by an illegibility of ruins. To paraphrase a Deleuzian maxim, the pursuit of the impossible occasions a new set of possibles, new forms of description. Yet taste and sight do not predominate in Description of the Lie so much as does aurality. Absence, after all, is articulated by the optical “lack of many a thing … sought,” a remembrance of things past which, in Shakespeare’s original formulation, “drowns an eye” (in tears, but also in a cognitive blindness) and becomes absorbed in sonic traces at the “expense of many a vanished sight.” Gamoneda does not see (he cannot see what is no longer there), but he listens:

I listened to the surrendering of my bones being deposited in rest,

I listened to the flight of insects and the retraction of the shadow

on entering what was left of me;

I listened until truth ceased to exist in the space or in my spirit,

and I was unable to resist the perfection of silence. ...(more)

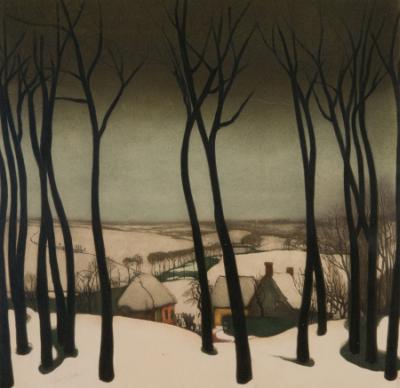

Valerius de Saedeleer

(1867 - 1941)

_______________________

From Ravenna Diagram

Henry Gould

Blackbox Manifold

UP NORTH

A fleet of ragged little cedars

harbored on a rugged

point of land (fog-

bound, sometimes – til it clears).

Wind skims burning through their

microscopic needle-

calipers. Draws cheerful

tears – ski-trails thatching frozen air.

Mnemosyne Point, on Lake

Vermilion (up north).

Time’s wooden (4th

grade) ruler. Not to break.

The placeness of quiet places.

Watercolor (frail, subdued).

No wide-lens tin-pan mood

music. Glinting silver traces

plowlines, old broken ground.

Maybe a shimmer of poplar

at the road’s end... where

sea-muck molds copper marshland.

One saturnine pedestrian paces out

the strand. His word

mutters a round solitude –

heartbroken yoke. Ultimate weight.

Lifted; torn from the soil toward

his own snowbound wedding band

(galactic, Galilean). Sand

underfoot. The stream’s bright ford.

...(more)

Three Poems from Ravenna Diagramthe Battersea Review

Henry Gould

_______________________

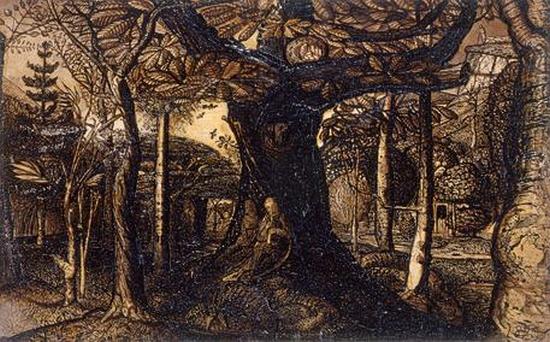

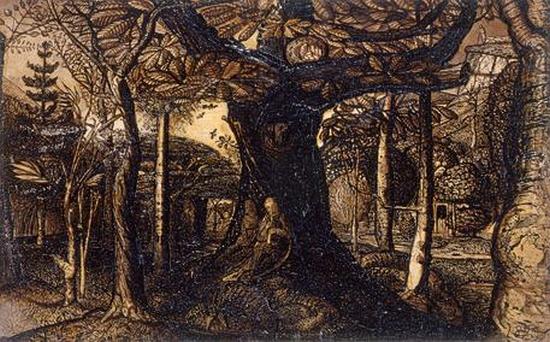

The Skirts of a Wood

1825

Samuel Palmer

b. Jan. 27, 1805

_______________________

For Non-Ideal Philosophy

Justin Erik Halldór Smith

A great many of the features of human existence --the fact that we are haunted by dead ancestors; that the soil is made up of the rotting bodies of living creatures like and including ourselves; that there is not just a question of whether we are bodies, souls, or body-soul compounds, but also of how different parts or regions of our bodies represent different dimensions of what we take to be ourselves; that we live through cycles of night and day and different things seem possible at different moments of these cycles-- are habitually left out of the accounts of human existence offered by philosophy. The great victory of philosophy, in fact, is often held to be that we have got down to the very most basic structure or framework of human existence, from the perspective of which our earth-boundness, or our bipedality, or our diurnality, come to appear contingent.* We take space and time as such to be categories of the understanding, but not the past of the ancestors or the heavenly realm of the angels.

For much of the history of philosophy, the basic orientating points of reference that gave life and sense to human thought were considered alongside the very most abstract frameworks that, one hoped, made this life and sense possible: not just the moral law within, but also the starry heavens above. Aristotle and Kant both, who gave us the most influential categorial schemes, also considered it an integral part of their projects to describe the rich diversity of things given in experience to which these categories apply. Leibniz's entire philosophical project, in turn, might be described as an attempt to show, once the austere metaphysical scaffold has been established, how we get the rich variety of bodily, world-bound experience we do.

But something has gone wrong along the way. ...(more)

_______________________

Valerius de Saedeleer

_______________________

Monologue

Novalis

presented by spurious

There is really something quite mad about speaking and writing: the proper conversation is a mere play on words. One can only be amazed at the ridiculous mistake that people make when they believe that they are speaking about things. Nobody knows the greatest hallmark of language: that it is concerned only with itself. That is why it is such a wonderful and prolific secret: that when one simply speaks for the sake of speaking, one expresses the most splendid and original truths. But if one wishes to speak of something particular, the capriciousness of language lets one say the most ridiculous and perverted things.

It is from out of this that a hatred of language grows in some serious people. They notice its playfulness, but they do not notice that contemptible chatter is the infinitely serious side of language. ...(more)

_______________________

Philosophy is one way in which ordinary language– which is one form power takes –is made to stutter. Like the poet, but a poet that has a taste for mathematical demonstration and formalism, good philosophy strives to be tectonic with respect to the plates that compose ordinary language.

Larval Subjects, Philosophical Language

_______________________

History set into motion again

Zoltán Boldizsár Simon

Abstract

It is believed to be common knowledge that history (in the sense of things done, in the sense of a collective singular) is suspended, that history is doomed to remain motionless. What's more, we all - or at least many of us - tend to believe that this precisely is how it should be: history, if such thing exists at all, has to stand still. It is against this backdrop that I wish to point out that there is a cultural phenomenon we should not leave unnoticed, namely, that a new quasi-substantive philosophy of history - operating with the notions of commemoration, trauma, and the sublime - sets history into motion again. It sets history into motion by reclaiming the monstrosities of the world, that is, by compensating for the rather one-sided attention paid to language in the last decades; and it sets history into motion despite the respect it seriously pays to the primary suspension of history.

the Open MIND Projectedited by Thomas Metzinger

The papers being offered look severely cool. As you all know, I think it's pretty much a no-brainer that these are the issues of our day. Even if you hate the stuff, think my worst case scenario is flat out preposterous, these remain the issues of our day. Everywhere traditional philosophy turns it will be asked why its endless controversies enjoy any immunity from the mountains of data coming out of cognitive science. Billions are being spent on uncovering the facts of our nature, and the degree to which those facts are scientific is the degree to which we ourselves have become technology, something that can be manipulated in breathtaking ways. And what does the tradition provide then? Simple momentum? A garrotte? A messiah?

R. Scott Bakker

Three Pound Brain

_______________________

Valerius de Saedeleer

_______________________

Entropy’s Top 93 Poetry Books in Translation of 2014

Ulysses

1947

Robert Motherwell

b. January 24, 1915

_______________________

Mirror, Mirror

Jericho Parms

drunken boat

Flying—or, not yet in the air but staring impatiently through the keyhole of the Boeing window while the attendant closes the overhead bins during crosscheck—it comes to me: a line from an old diary. The first in a series of entries addressed to Leonardo da Vinci when I was seven, or perhaps eight, when I would have called it a journal—somehow older-sounding, a little more mature:

It’s true; it’s all backwards to them anyhow.

Except that when I wrote the words, I began from the right side of the page. With my left hand, I reversed each letter’s form, aligning them neatly atop the page's faint lines. I moved swiftly towards the center binding—the people’s margin—that place where we learn when we are small to begin.

But it didn’t have to be that way. Da Vinci knew this. His notebooks, now vaulted in climate-controlled libraries, were scrawled in mirror-image cursive. His works bear inscriptions like primitive forms of cipher, Islamic calligraphy, or Samaritan script. The kind of imprints found on ancient tablets and gilded parchment—the Torah, the Koran, the Book of Kells. Maybe this is where my obsession with holy books began, why I thought I might like to write one someday, its pages all beginnings and endings, footnotes and failures, about a girl who played in sprinklers while loving Heraclitus. (Or, rather, rinsed off in hydrants while lusting after da Vinci). ...(more)

_______________________

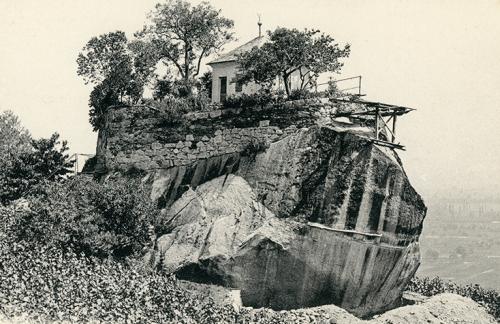

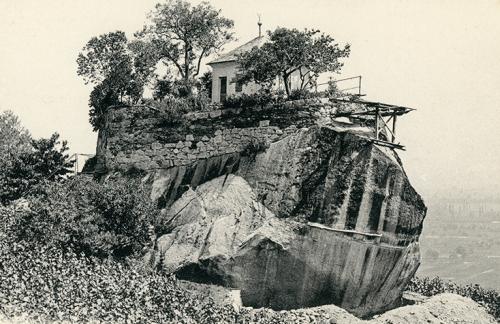

Pierre des Marmettes

1905

collection of Vincent Franzen

Erratic Imaginaries: Thinking Landscape as Evidence

Jane Hutton

(....)

Scientific and lay observations of erratic boulders have served as critical, distributed evidence for the development of the theory of glaciation; by implication, ideas of geologic time and the location of humans within it are also entangled in such a theory. Erratics attracted a wealth of curiosity through their alien lithology and their unexpected patterns of distribution, both of which were crucial aspects of the evidence needed to reconstruct an Ice Age. Still, long after they played a role in establishing modern geohistory, individual boulders persist as cultural artefacts for provoking and inscribing ideas about time. Certain erratics maintain a dual status as physical fragments of deep time and contemporary cultural objects that relay more recent histories. They are curious things—in size, shape, and position. They are visible and climbable relics of glacial processes too vast to otherwise experience. They are prone to being used as markers of human events and spaces, yet are also markers of deep time, having travelled long distances in nearly unimaginable environments. It is through this conflation of vastly different timescales that erratics bridge a seemingly unbridgeable divide between geological time and human action.

...(more)

Architecture in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Design, Deep Time, Science and Philosophy

edited by Etienne Turpin open humanities press

Introduction: Who Does the Earth Think It Is, Now?

Etienne Turpin

(....)

If the Anthropocene can be understood as a chronotope specific to the moment when the human species begins to recognize its impact not only on spaces of settlement and habitation, but also on the scale of geological time, then we might conclude these introductory remarks by speculating on how the strategies of problematisation used to approach the Anthropocene thesis can generate collaborations among philosophy, politics, science, and architecture. In his essay “On the Earth-Object,” Paulo Tavares remarks: “‘Global nature’ is therefore and above all a space defined by a new socio-geological order in which the divisions that separated humanity and the environment, culture and nature, the anthropological and the geological have been blurred.” The problematisation made possible by this blurred reality is one that undoes the givenness of our inherited assumptions about the earth as an object of knowledge; that is, the confusion created by the act of de-ontologizing the separation between humans and nature allows contemporary theorists, activists and designers to develop problem-formations adequate to the politics of hypercomplexity that accompany our postnatural inhabitations of the earth. In nearly every book he wrote, including those he co-authored with Félix Guattari and Claire Parnet, Gilles Deleuze managed, in one way or another, to integrate his favored refrain: problems get the solutions they deserve according to the terms by which they are created as problems. The varied repetition of this notion is certainly not meant as a slogan; for Deleuze, the work of producing problems, that is, of problem-formation, is a fundamental task of philosophy. With the provocation of the Anthropocene thesis, philosophy can produce new constructions that transform trajectories of thought; by developing affinities and collaborations through multi-disciplinary, multi-scalar, and multi-centered approaches, architecture too can discover its unique capacity to transform the present and future condition of the Earth System. In the Anthropocene, designers, activists, and philosophers will all have the earth they deserve; we hope this collection contributes to the conversation about how it might be constructed.

...(more)

Open Humanities Press

_______________________

Manuel Hernández Mompó

d. Jan. 25, 1992

_______________________

Modern Poetry in Translation

No.3 2014 - The Singing of the Scythe

Edited by Sasha Dugdale

'The Singing of the Scythe' is a selection of WW1 poetry like no other. From Paul van Ostaijen’s long Dadaist poem ‘Occupied City’ to the Japanese poet general Nogi to Punjabi folksongs, this issue creates a place for lesser-heard voices of the war and presents a polyphonic response to the conflict.

Where the Earth's outstretched

Eugene Dubnov

translated from the Russian by Alison Brackenbury

Where earth’s outstretched, the chest heaves with pain,

to wake

with a heart-jolt,

having gone to the close of the final lane

to come

through birth again.

Where the branch twists, where the green’s strokes

are uneven,

where waves are blue in sun,

to turn the mortal face and the hand’s shiver

to a rondeau’s circling

tune.

This autumn in the great towns

as bridges rise

gives space.

A boy sweeps leaves in the early morning

from the fountain

base.

_______________________

Study in Automatism

Robert Motherwell

1976–77

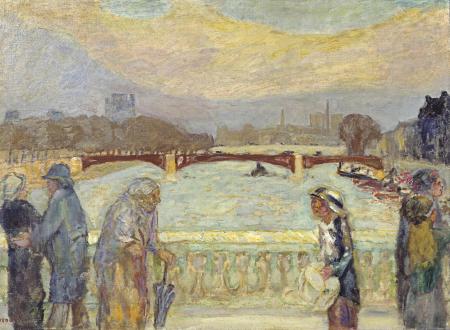

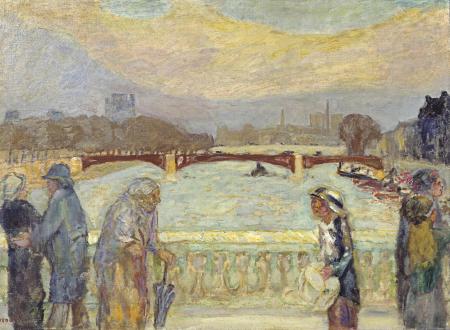

Pont de la Concorde

1913-5

Pierre Bonnard

d. January 23, 1947

_______________________

HEART THREAD 163 & 164

Robert Kelly

163.

Hard to read the numbers in this light

go by the feel of the machine road through water

voices in the street fear of believing

whatever they say must be wrong way round

nobody out there speaks our language

urgent children touching in the dark

who are those who move around inside me

she walks by with a woodpecker on her back

to prove that language is a function of the skin

because language is all boundary

a walled garden and a maze at the middle

and a mirror globe at the center with roses all round it.

currently unfolding at Robert Kelly's MILL OF PARTICULARS

_______________________

Folkdance Melancholia

1989

Georg Baselitz

b. January 23, 1938

_______________________

Madhur Anand: Two Poems

Lemon Hound

If I Can Make It There

It’s January and in the news, white fluff, cherry

trees flowering in Brooklyn. What to make of the changed

phenology? A closet of cuttings: Pale yellow

pages. Lignin destabilized where lines are preserved.

I’ll follow greenhouse seeds, edit second editions

but need more breathing room, more literature review.

And better intentions. I must try to recycle

last year’s unread New Yorkers. I must learn all the facts.

How in the nineteenth century Croatian cherries

were bleached with sulphur dioxide, dyed a candy red,

and soaked in sugar. I must attempt a Manhattan.

Sweet vermouth, bitters, that pitless heart at the bottom.

...(more)

Madhur Anand at the University of Guelph

_______________________

necessity, immensity, and crisis (many edges/seeing things)

Fred Moten

There’s a more than critical criticism that’s like seeing things—a gift of having been given to love things and how things look and how and what things see. It’s not that you don’t see crisis—cell blocks made out of the general meadow, and all the luxurious destitution and ge(n)ocidal meanness, the theft of beauty and water, the policing of everyday people and their everyday chances. It’s just that all this always seems so small and contingent against the inescapable backdrop of constant escape—which is the other crisis, that is before the first crisis, calling it into being and question. The ones who stay in that running away study and celebrate its violently ludic authenticity, the historicity that sends us into the old-new division and collection of words and sets, passing on and through, as incessant staging and preparation. This necessity and immensity of the alternative surrounds and aerates the contained, contingent fixity of the standard.

(....)

The notion that crisis lies in the ever more brutal interdiction of our capacity to represent or be represented by the normal is as seductive, in its way, as the notion that such interdiction is the necessary response to our incapacity for such representation. Their joint power is held in the fact that whether abnormality is a function of external imposition or of internal malady it can only be understood as pathological. Such power is put in its accidental place, however, by the ones who see, who imaginatively misunderstand, the crisis as our constant disruption of the normal, whose honor is given in and protected by its representations, with the ante-representational generativity that it spurns and craves. This is the crisis that is always with us; this is the crisis that must be policed not just by the lethal physical brutality of the state and capital but also by the equally deadly production of a discourse that serially asserts that the crisis that has befallen us must overwhelm the crisis that we are; that crisis follows rather than prompts our incorporative exclusion.

...(more)

FloorA Journal of Aesthetic Experiments Synthetic_zero

_______________________

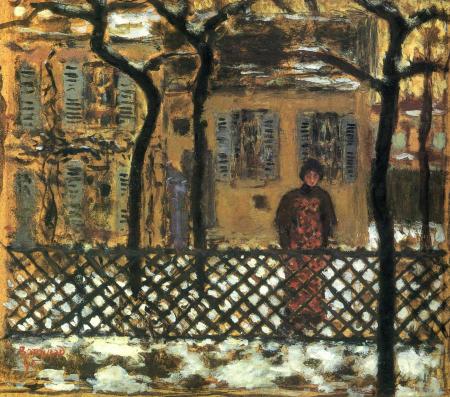

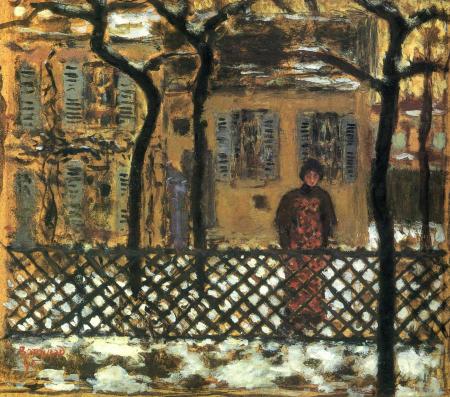

At the Fence

Pierre Bonnard

1895

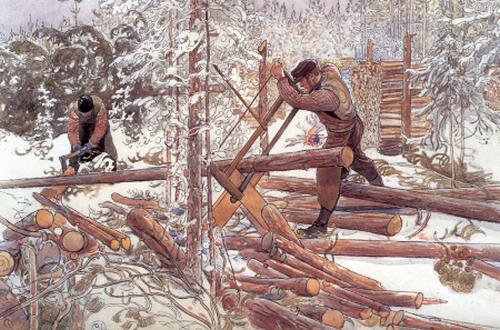

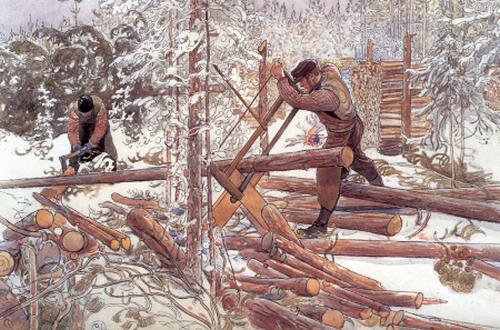

Woodcutters in the forest

1906

Carl Larsson

(28 May 1853 – 22 January 1919)

_______________________

Faceless Book

Lauren Berlant

berfrois

(....)

I sense that Facebook is about calibrating the difficulty of knowing the importance of the ordinary event. People are trying there to eventalize the mood, the inclination, the thing that just happened–the episodic nature of existence.So and so is in a mood right now.So and so likes this kind of thing right now; and just went here and there. This is how they felt about it. It’s not in the idiom of the great encounter or the great passion, it’s the lightness and play of the poke. There’s always a potential but not a demand for more.

Here is how so and so has shown up to life. Can you show up too, for a sec?

How can the “episodic now” become an event? Little mediated worlds produced by kinetic reciprocity enable accretion to become event without the drama of a disturbance. The disturbance is the exception. And that’s what makes stranger intimacy a relief from the other kind, which tips you over.

...(more)

_______________________

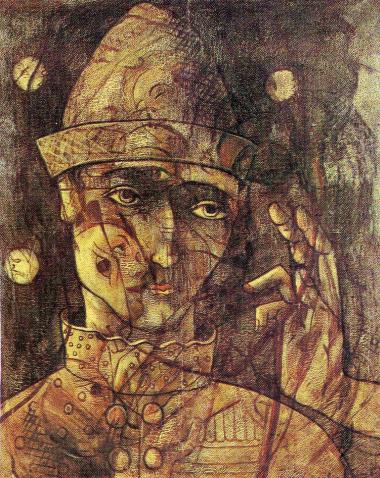

Transparence

Francis Picabia

b. January 22, 1879

_______________________

Clayton Eshleman: 'Wound Interrogation'

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

(....)

The frailty of being holed & rampant with closure.

Blake’s angels feast on my neck

as strapped to this fuselage of honking verbs I watch Hades:

a zyzzogeton munching on alfalfa alpha.

For that matter, what is deliverance?

To find oneself present at Pluto’s cornucopian spread & grasp

that one must not pluck a single grape?

The first Persephone, Laussel, pumped time out of her held-aloft bison horn,

& with that image phantom she impregnated herself!

Between the cracks in the time board,

to write from a double periphery, in swerve with the labrys…

“Not to subject the change,” Hades quipped,

“but what bugs you the most about America today?”

...(more)

_______________________

Geminis

Francis Picabia

1936

_______________________

balzac’s physiology of the employee

P.T. Smith

3am

In the war against the specific sufferings induced by office life, Herman Melville’s Bartleby is revered as saint and martyr. In the sacred literature of the office genre, his death is the office worker’s call to arms. But it’s a mistake to think that before his sacrifice, the literary universe wasn’t waging such a war against office ennui. Bartleby’s sacrifice is still honored and “I would prefer not to” remains our great rallying cry, but the more his followers understand the history of their war, even if it means recognizing how little ground has been gained, the more allies they find, the better suited they are to continue the fight. Honoré de Balzac’s The Physiology of the Employee (1841) is a guidebook, and it is not outdated. In its relevancy yet seeming strangeness, it fits with the rest of Wakefield Press’s catalog. His description of the climate in which he wrote sounds little different from the economic recession of recent years, and the lack of change since: “Personal expenses were examined with a fine-tooth comb. Benefits were chipped away at.” In its careful organization and laying out of office principles, The Physiology of the Employee serves as a work that grounds the spirit of Bartleby.

(....)

Bartleby is the fallen saint, and Balzac keeps the troops in the culture war self-aware and loose. He can open the eyes of the undecided and loosen the tensed shoulders of the partisans. The office is torturous, but also pathetic, something to be laughed at. Balzac’s description of the office is of a stifling place, then when it an office is moved, pulled down the street in carts, it’s absurd. The flying bits of the office may be frightening, but that is overwhelmed by the entertainment in its strangeness. Balzac is able to imagine, as I often find myself doing, that the whole of daily work is an experiment on the employee by some unnamed being. He calms us by reminding us though we are refused motivation, we get take by wasting half our work day, now time wasted on gchat, fantasy football, or editing a review.

The perfect escape, the way to truly fight against the system, to avoid simply “prefer[ring] not to” or to do so with humor, and side by side, instead of despairingly alone, may lie in Balzac’s belief that “the most beautiful things that France has accomplished were achieved before the advent of reports, when decisions were made spontaneously.” So, in protest, be spontaneous, confound the cretins, never become one, band together with those who do the same. Maybe something can be created from our oppressive office environments and our downward spiral to becoming a cretin—just don’t be delusional, don’t hold your breath....(more)

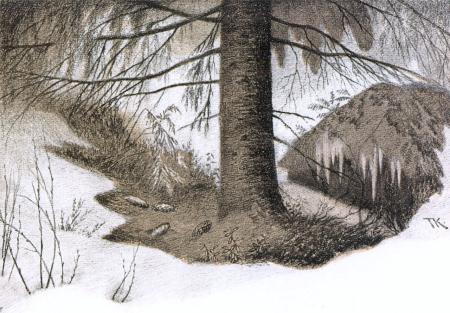

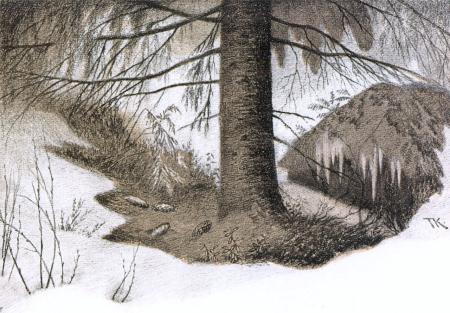

Forest's Wintergarden

1901

Theodor Kittelsen

d. January 21, 1914

_______________________

from The Black Flower and Other Zapotec Poems

Natalia Toledo

translated from the Isthmus Zapotec and the Spanish by Natalia Toledo and Clare Sullivan

Flower that Drops Its Petals

I will not die from absence.

A hummingbird pinched the eye of my flower

and my heart mourns and shivers,

does not breathe.

My wings tremble like the long-billed curlew

when he foretells the sun and the rain.

I will not die from absence, I tell myself.

A melody bows down upon the throne of my sadness,

an ocean springs from my stone of origin.

I write in Zapotec to ignore the syntax of pain,

ask the sky and its fire

to give me back my happiness.

Paper butterfly that sustains me:

why did you turn your back upon the star

that knotted your navel?

...(more)

From Ahtna to Zapotec: Celebrating Four Years of Literature from Rare Languages

Assistant Editor Daniel Goulden on rare languages in translation and Asymptote

(....)

My experience has shown me that translators overall are a friendly, collaborative bunch. Over the course of my research I’ve had conversations with writers and translators from places as geographically dispersed and dissimilar as Afghanistan and South Africa, almost always finding people more than happy to submit work or introduce us to translators who could. Unlike the cliché about the dog-eat-dog world of New York agents, translators are in service not just to themselves but also to their languages, and are usually delighted to find a platform where they can share their work and bring more attention to those languages.

So far, we have published great works of literature from more than 25 rare or underrepresented languages, and we hope to uncover much more in 2015 and beyond. ...(more)

Song for the Return of the Sun

At midwinter, an old man from Slana River burst out singing.

He kept singing a song for the sun to return.

After three days, the sun rose and shone brightly on the land.

That evening, his face burned, the old man wrung sunlight from his clothes.

Three Poems

translated from the Ahtna by John Smelcer

asymptote

_______________________

Theodor Kittelsen

_______________________

Me and My Shadow

Alanna Schubach on The Babadook

full stop

The poet Robert Bly, in his A Little Book on the Shadow, wrote about “the long bag we drag behind us.” Throughout our lives, Bly said, we excise parts of ourselves as if they were tumors, shoving them into this bag, hidden from view: perhaps, as children, a noisy ebullience that irritated our parents; or an inquisitiveness that a teacher shut down; or a sensitivity that made us targets in the cutthroat world of adolescent politics. By the time we reach adulthood, Bly wrote, the bag is stuffed, and if we attempt to peek inside, we find that all the things we secreted away have, in their long tenure in the darkness, turned sinister: “they are not only primitive in mood, they are hostile to the person who opens the bag.”

(....)

To have within oneself a rampaging monster is alarming; for a mother with children in her care, it is unacceptable. Certainly, from Medea to Mommie Dearest, we have examples in the canon of mothers who fall tragically short of being the ideal, beatific nurturers, but seldom is there a middle ground depicted between parental bliss and villainy — which makes the Australian indie The Babadook a rarity. It poses as a horror flick, but in fact is a psychological drama that chronicles one woman’s confrontation with her shadow. ...(more)

_______________________

December

Theodor Kittelsen

1890

_______________________

Pages from My Knapsack:

A Journal from My Time in the Swiss Army, 1939

Max Frisch

translated by Linda Frazee Baker

conjunctions

We had just come out of the woods that morning, a gardener’s boy and I, where we had been cutting down young ash trees. To be made into graceful little stilts under a dovecote for the municipal park. This was my first real job, newly begun, the first blueprint of mine that would become reality. Not just paper any more, not just mere lines, words, images. These slight little tree trunks were entirely real, you could touch them, half a wagon full. We were going straight to the carpenter’s shop—

And then the bells rang.

Today, on the eve of the military call-up, all the train stations and bridges are already guarded by brightly shining bayonets. Soldiers in field gray swarm everywhere as if shot out of the earth. One squats next to me in the train corridor so that we have to get up at every station and move our knapsacks. He didn’t know there were so many Swiss, he says with half a smile.

We ride through the night. The windows are all black now, as if we were riding through an endless tunnel. No one here seems really surprised. Only a certain seriousness, a certain bitterness that it has really happened, just as we thought it might. Some pretend to sleep so they can close their eyes. What a hurried leave-taking it has been. Some just sit there, elbows on their knees, and stare at their shoes. Thankfully, there is no singing, and no platitudes either.

After all, what can anyone say?

Only a young woman traveling with us loses her nerve while an old soldier takes her child on his knee. On and on she babbles about her husband, who will be in the auxiliary service. She seems to think we soldiers should melt in sympathy.

...(more)

One Day

1976

Esteban Vicente

b. January 20, 1903

_______________________

“Ontogenesis and the Ethics of Becoming”

An interview with Elizabeth Grosz

by Kathryn Yusoff

(....)

I hope to show that terms that we consider opposites – mind and body, self and other, reason and passion, male and female, ideality and materiality – cannot be considered as opposed. There are no oppositions in the real but only differences, productive differences to the extent that difference is not assimilated into an oppositional form itself (as, say, identity). I wanted to show that this is not an original idea at all but that it has marked the history of Western thought intermittently, from the time of the earliest origins of Greek philosophy, in the Presocratics through to the present. What this tradition has established is a new place for philosophy, or thought more generally, not in the creation of truth but in rethinking the (internal) relations of thought to things. Thought is not a mirror of the real, but its own processes of living. There is something of thought that lives beyond the expanse of materiality, something that the Stoics, Spinoza and even Nietzsche understood as touching eternity. I want to give a secular understanding to this divine (or for Nietzsche, demonic) impulse to aspire to the eternal, to think the eternal and to act in accordance with it. This has a decidedly old fashioned tinge, but I believe that in fact the contemporary emphasis on materiality has missed this element of the eternity of thought and will.

...(more)

Society and Space

_______________________

Esteban Vicente

_______________________

Poems by Ilya Krieger

Translated by Alex Cigale

A house is not a house unless it is inhabited.

K. Marx

In forests, in deep blue forests,

In the house, assembled out of pine trunks,

In the house, assembled out of forest shadows,

In the house, assembled out of the night's silence,

In the house darkening and dozing,

Where whispers remain, where whispers stroll on the ceiling,

Where there are clipped wings, where there is honey and milk,

Where there are hushed sobs, where ivy covers the ceiling beams,

Where time stands still, where motion is outside only, not here,

In the house made of rain and fog,

In the house that stands over trampled stars,

In the house, assembled out of trunks of pines,

In the house, assembled from the forest's gloaming,

In the house, assembled from night's silence,

In the house, assembled out of viscous dreams,

In the house, where a part of me has securely settled,

For that house - is the end-all and be-all,

He who spends a night in the house, which I, fortuitously, vacated,

He will not continue on his path unaltered,

He will die and be reborn, his friends will not recognize him,

A part of him will remain there, within the walls of the house,

In the forests, in deep blue forests,

In the house, assembled from trunks of pines,

In the house, assembled out of the forest's dimness,

In the house, assembled out of the night's silence.

...(more)

Twenty-first Century Russian Poetry

Edited by Larissa Shmailo big bridge

_______________________

Esteban Vicente

_______________________

Foreign Bodies: Gottfried Benn, Patrizia Cavalli, and the Situation of Translation

David Rivard

Numero Cinq

(....)

In Another Republic, Strand and Simic brought together a much wider range of poets in translation than had been previously available, with generous selections by seventeen poets. More ethnically and aesthetically diverse (though, inexplicably, all men), the poets in Another Republic were largely the inheritors and adapters of High Modernism—sometimes combining modernist techniques with the more fabular and allegorical impulses found in folklore traditions; sometimes focusing literary cubism on the apparently banal and everyday, endowing ordinary people and places with strangeness and mystery; almost always deploying a self in the poem that was both mordantly comic and humanly vulnerable.

Paul Celan, Yehuda Amichai, Julio Cortazar, Carlos Drummond De Andrade, Zbigniew Herbert, Fernando Pessoa, Czeslaw Milosz, Yannis Ritsos, Jean Follain, and the others were largely unknown to American readers at the time. Many, if not all, had experienced exile and/or the violence of mid-century history. They often wrote with far more nuanced consciousness of the political than Americans were used to in their poetry. They were also highly tuned to the absurdities that historical fate has increasingly had in store for all of us. The variety of their approaches to writing a poem was stunning. For those in two generations of American poets who have read Another Republic, the influence has been profound I suspect.

That the book is no longer as well known as it should be, and that the poets included in it have mostly passed into the oblivion of the canonical, speaks volumes about contemporary American poetry. Solipsistic, driven by social media and the marketing campaigns of publishing companies and academic trade groups like AWP, ensconced in print and digital affiliations that function like gated-communities, monetized by the promotional efforts of well-meaning institutions such as the Academy of American Poets and bien-pensant congregations like The Dodge Festival, American poetry no longer seems as open to the influence of work in translation, despite the fact that more of it is being published than ever.

(....)

... Translated poetry seems like just another marketing niche, easy enough to avoid if one is intent on maintaining ignorance and preserving one’s assumptions.

Inattention or indifference or distraction, whatever the case, some recently published books by major figures, books bringing world-class writers into English in a comprehensive way for the first time, have been largely ignored. Two in particular, both issued in 2013—by the long-dead German Expressionist, Gottfried Benn, and the very-much alive Italian poet Patrizia Cavalli—slipped almost totally under the radar. Oddly enough, both were published in handsome editions by Farrar Strauss Giroux—a house whose reputation and promotional reach would, in another time, have guaranteed a thoughtful, widespread reception. Neither seems to have found the notice and readership it deserves.

...(more)

_______________________

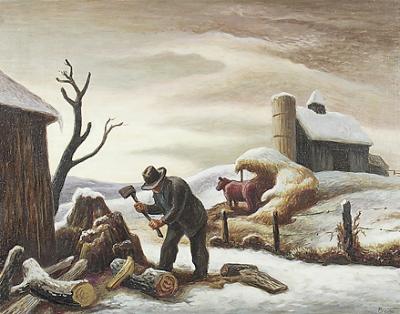

Esteban Vicente

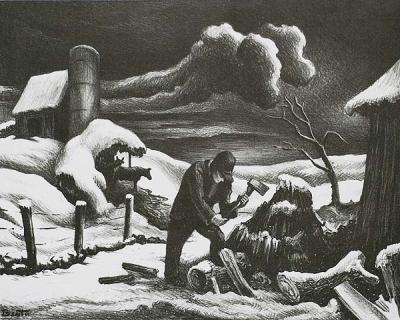

The Woodpile

1939

Thomas Hart Benton

(April 15, 1889 – January 19, 1975)

_______________________

Gabriel Josipovici: Hotel Andromeda

reviewed by John Self

(....)

Cornell himself struggled, as Helena struggles – as every artist ever has struggled – to achieve the alchemy that transforms life into art. “How,” Helena writes as she quotes from his notebooks, “to hold on to ‘the ceaseless flow and interlacing of original experience’? How to hold on to it and not kill it in the process?” Josipovici himself appears to have managed it, making a fluid, playful and serious book full of delights, from the “demented silence” of a Hans Namuth portrait of Cornell, through Wallace Stevens’ poetry (“Those that are left are the unaccomplished, / The finally human, / Natives of a dwindled sphere”), to Wittgenstein’s reported final, ambiguous words (“Please tell them I’ve had a wonderful life”). It’s all evidence of a mind full of both life and art, and a book that “preaches no sermon, yet, like music, it resonates within us, setting free a whole range of possibilities.”

...(more)

_______________________

“Cascando”

Samuel Beckett

scroll down

1

why not merely the despaired of

occasion of

wordshed

is it not better abort than be barren

the hours after you are gone are so leaden

they will always start dragging too soon

the grapples clawing blindly the bed of want

bringing up the bones the old loves

sockets filled once with eyes like yours

all always is it better too soon than never

the black want splashing their faces

saying again nine days never floated the loved

nor nine months

nor nine lives

2

saying again

if you do not teach me I shall not learn

saying again there is a last

even of last times

last times of begging

last times of loving

of knowing not knowing pretending

a last even of last times of saying

if you do not love me I shall not be loved

if I do not love you I shall not love

the churn of stale words in the heart again

love love love thud of the old plunger

pestling the unalterable

whey of words

...(more)

“Always Is It Better Too Soon Than Never”

A modern love poem in conflict with both love and poetry.

Robert Pinsky

(....)

The poem’s erratic, doubling progress follows those conflicted energies as it oscillates, I think frantically, between the two magnetic attractions of abundance and of silence. The traditional lover’s uncertainty or agony has, in this poem, a rhetorical counterpart in the struggle between embracing traditional eloquence and rejecting it. For instance, “the grapples clawing blindly the bed of want” is a line of iambic pentameter as regular as anything in Shakespeare. The reckless, hyperbolic eloquence of the images—those eye-sockets and the “black want splashing their faces”—collides with the flatly corrosive, meaning-dispersing, adverbial “all always is it better too soon than never.”

For me, that hovering, back-and-forth movement between passion and reservations, need and doubt, images and disavowals, creates a strong emotion. The feeling gathers force from the poem’s argument with itself.

...(more)

_______________________

Jean Delville

b. January 19, 1867

_______________________

Ian Craib, The Importance of Disappointment

reviewed by Mark Carrigan

(....)

Disappointment has its roots in the social world and this is why dilemmas are ubiquitous in society. Craib’s argument is that “there is much about our modern world that increases disappointment and at the same time encourages us to hide from it: to act as if what is good in life does not entail the bad – for example, that we can love and be loved by another person without having to give up other aspects of our lives”. Disappointment is irrevocably bound up with ambivalence because “nothing is ever simply ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and most things are at the same time good and bad”. This entails a perpetual remainder, uncomfortable left overs to our decisions which run contrary to what we expected and hoped for. Craib’s point is two-fold. Firstly, disappointment is unavoidable in this sense regardless of the social context. Secondly, there are peculiar features of our social context which encourage problematic tendencies in how we react to disappointment.

He brings this point to life in his discussion of relationships and intimacy, drawing on the use Giddens makes of self-help books in his work on late modernity to develop a critique of ‘the powerful self and its illusions’. He takes issue with a tendency to see ‘emotional satisfaction’ as the central basis for intimate relationships, arguing that with this “our primitive fantasies of complete satisfaction are brought into play”:

The simple question ‘Is everyone OK?’ carries a whole impossible world of satisfactions, one loaded with so much feeling that the thought that things might not be OK is enough for the speaker to consider flying from the relationship. The demand for the impossible is at the centre of this type of intimacy; the tragedy is that it prevents us from seeing or learning from its impossibility. If everything is not OK, we do not learn but seek out another relationship in which it might be OK. If we fall in love, then the decline of being in love, whether slow or fast, is felt as a failure rather than a deepening of our understanding of the world and the reality of the other person. The speaker’s sense of ‘never being satisfied’ is an accurate perception of internal and external reality, but it is experienced not as knowledge and understanding but as failure and deficiency.

...(more)

_______________________

on the tragedy of life

Ken Gemes interviewed by Richard Marshall

3am

Ken Gemes never stops brooding on what the postmoderns got right about Nietzsche, about the lack of seriously considered theories in Nietzsche, about why his naturalism isn’t of interest, about the stark nihilist fact at the heart of Nietzsche’s philosophical outlook, about the role of the genius, about being strangers to ourselves, ressentiment, Nietzschean localism, about Freud and Nietzsche’s relationship, about the ascetic ideal, about the canonical virtue of scientific empirical testability, about the need for fine grained logical content, about the value of his different philosophical interests and why what Nietzsche says may well be literally true. All in all, this one walks into the essential territory like its griot time…

...(more)

_______________________

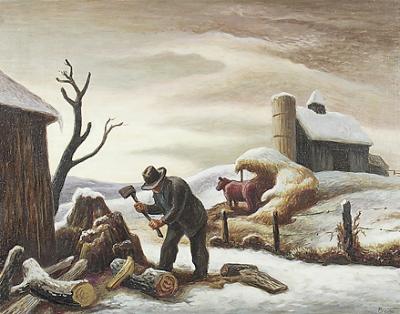

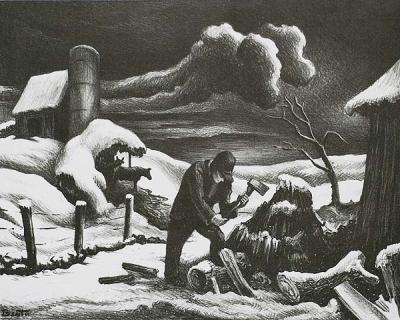

Woodchopper

Thomas Hart Benton

1936

_______________________

Drunken Boat translation special

Anna Rosenwong's introduction

(....)

How exciting, then, to enlarge this corpus with new translations, adaptations, and reimaginings of just three stanzas of Rimbaud’s famous poem ( "Le bateau ivre"). Where critical comparison work can be constrained by formality, and personal artistic vision sets Moore and Bergvall’s pieces apart, this flotilla means to be generative, aggressively plurivocal, to make drunken mischief and to go beyond interrogating translation as appropriation to embracing translation as mutation. Here you’ll find Oulipean mutinies, gentle unmoorings, and an associative translator’s note as translation itself.

...(more)

Charlotte Mandell translating Arthur Rimbaud

Who kept running, spangled with electric lunes,

Crazy plank, with escort of black seahorses,

When all the Julys with their cudgels have crushed

Ultramarine skies into burning craters;

I who trembled, and could feel the moans a hundred miles away

Of rutting behemoths and sluggish maelstroms,

Eternal spinner of blue immobilities,

I miss the Europe of ancient parapets!

I have seen sidereal archipelagos! and islands

Whose delirious skies open up for a drifter:

— Is it in these bottomless nights you sleep in exile,

You million golden birds, o Power yet to come? —

Drunken Boat 20

Returning home

1887

Arnold Böcklin

d. January 16, 1901

_______________________

The Blank Screen Will Not Save You

The desire to refresh, recharge, and reinvent ourselves is natural, even healthy-but resolutions tied to objects and tools tend to disappoint us.

Navneet Alang

hazlitt

(....)

So much of digitality convinces you this is actually possible. Notebook software such as OneNote or Evernote comes with the guarantee to sort out your life and mind; the fitness tracking craze and quantified self movements promise that data and beeping reminders can get us or our minds in shape (“self knowledge through numbers” is the slogan of one such system); and each hot new buzzed-about social service comes with the pitch that it will finally manifest the dreams that surge under our lives. So we charge ahead, convinced that each new blank screen will, finally, be filled with the realization of our best intentions.

(....)

What contemporary digital culture often seems to do best is prey upon and channel desire. Freud might say that the fantasy of a new self is the longing for a lost object—except that the missing thing in this case is the self that we weresupposed to become. My computer purchases, those magazine covers, and the rise of tracking apps seem borne of this very feeling.

Yet, I’d argue that Freud’s student Lacan had a more interesting take: He believed we don’t actually want the lost object, but instead want to endlessly circumnavigate and circumlocute it. We want to always avoid the horror of the Real, never admitting that, in truth, we will never cut down on our drinking, truly face our fears, or ever turn over a new leaf. What we want is the pleasure of spiraling around the dream, toying with the idea of a new self, admiring the view as it keeps slipping behind an ever-receding horizon. There’s a certain comfort in the fantasy of never confronting ourselves.

...(more)

_______________________

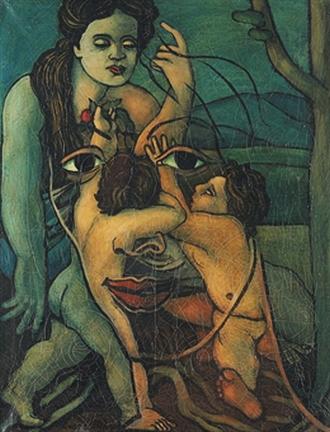

Francisco Cossio

d. January 16, 1970

_______________________

A War. A Fear. A Scar. An Ear.

Richard Hoffman

(....)

*

A fear sat in the moonlight,

sad and confused: “I am a fear

of what?” he asked himself.

“Don’t I have to be a fear of

something?” He worried he had

never grown up, that he was

only pretending to be an adult

fear. All the other fears seemed

defined, themselves, real.

In the moonlight he remembered

nothing of his origin. “Maybe

if I knew where I came from….”

Men? Women? Fire? Flood?

The dark? The cold? Spiders? Blood?

Who were my mother and father?

He feared the moonlit answer.

*

Back when the scar was becoming,

back when the cut, back when

no one can remember, then

(we’ve been assured by countless

generations) a perfection was.

You may believe it, may even

know a story of the hand and blade,

and whose, and music with it,

but the scar cannot afford such.

The scar prefers to travel light,

sometimes disguised as pleasure,

or even a special kind of gesture.

Its favorite ride is the exquisitely

designed nerve to the tongue,

which carries it, pollen, across

old understandings, pages, images

and rhymes, from time to time

gathering itself in silence,

refreshing itself with opened flesh.

*

...(more)

_______________________

Odysseus by the sea

Arnold Böcklin

1869

_______________________

melancholy, the contemplation of the movement of misfortune, has nothing in common with the wish to die. It is a form of resistance. And this is emphatically so at the level of art, where it is anything but reactive or reactionary. When, with rigid gaze, [melancholy] goes over again just how things could have happened, it becomes clear that the dynamic of inconsolability and that of knowledge are identical in their execution. The description of misfortune includes within itself the possibility of its own overcoming.

Sebald, untranslated foreword to a volume of his own essays

reposted from Spurious

_______________________

Francisco Cossio

_______________________

Too Fast, Too Furious

In search of time gained

the editors

n+1

(....)

The key is that a society undergoing acceleration gets caught in a feedback loop it cannot escape, whereby acceleration in production, circulation, and distribution (in Rosa’s terms, “technical acceleration”) drives social change. The institutions of society no longer guarantee stable life paths. If in classical modernity people could imagine their lives in intergenerational terms — say, the same firm passing down through a bourgeois family — in late capitalism, turnover is so accelerated that it becomes hard to imagine one’s life course even within a few years, let alone a few generations. This in turn drives a sense of the acceleration of the “pace of life,” the psychological feeling of always being out of breath — which in turn drives the desire for more labor-saving technology, and technical change. There have been world-historical short-circuits in this loop — the 1930s, which spelled forced leisure for thousands, and the 1970s, when advances in technical change and the rate of profitability they promised seemed to meet a historic limit — but overall the pressure hasn’t slackened. For Rosa, modernity is defined by a continual sense of the present contracting—a feeling that what one is able to do within a given time frame is shrinking. The feeling comes about because the variety of social experiences available is ceaselessly proliferating: the number of things you might be able to do becomes impossibly large, and expands every day with implacable speed.

...(more)

|