|

photo - mw

_______________________

Draft 98: Canzone

Rachel Blau DuPlessis

(....)

Yet this part of the work remains closest to darkness.

The knowledge of yearning will not be complete.

There is no there; it’s all degrees of here.

Cannot touch them whom we are marked by.

But they are palpable and enter this place.

Be nomadic, nomad. Wander with the wanderers,

yet safe in the room. There is at once too much

and much too little. Wait it out.

“The bit of ugly, the glitch, the torn, the sweeper, the tender,

the constant reminder that things are being made, unmade

and tended”--you are now one part of all of this.

You will be it, help it, answer and feed that

surface of cries, chirps. You will call out.

Live in empathy. Let the agony be. Comfort it.

Reject the whole that someone claims is rule.

A hole, a line, a hold, a lie, a hope,

a hype will slide you through this most dangerous spot.

Resist only rectitudes, resist the crazed

and driven knowers. Find and replace.

Though the mechanism to depict this is

called documentary, still it needs the stinging

pulse of lines. This matches that.

All “ofness” exists

for much more Of.

The beyond moves to two places: here and there.

To achieve connection,

is there just one route of passage?

There is not.

...(more)

_______________________

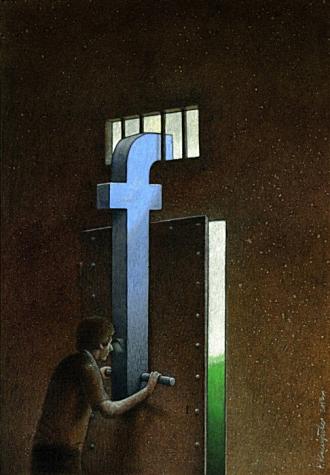

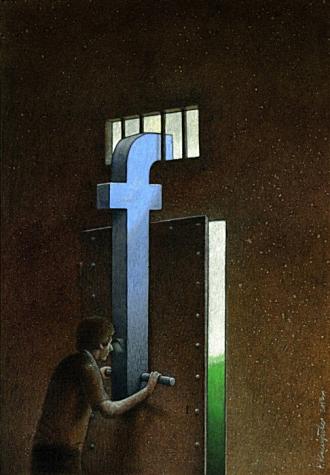

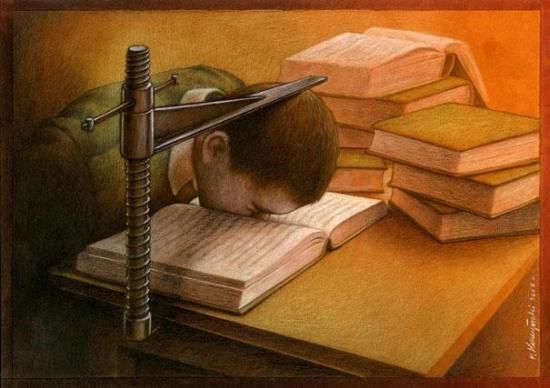

Pawel Kuczynski

_______________________

There Is Madness In This Method:

Commentary on a fragment from Deleuze and Guattari’s What Is Philosophy?

Terence Blake

Agent Swarm

(....)

It is often said that people are indifferent to the dreams of others, that only the dreamer finds the story he is recounting of any interest; I have always been perplexed, even shocked, by such received wisdom. I usually find people’s dreams very interesting, even the seemingly banal ones where nothing strange or untoward happens. I like Deleuze and Guattari’s association of dreams and philosophy, for I find dreams very philosophical, and Deleuze’s philosophy very oniric. I used to (30 years ago!) express this by saying that Deleuze’s philosophical style incarnates a constant “pulsation between the conscious and the unconscious”, but though I still agree with the thought I find the vocabulary too academically “recognizable”.

People are indifferent to others’ thoughts, just as they are indifferent to an other’s dreams. Until some danger crops up, and their attitude changes. If the danger is to them, they panic and run, or at least give a wide berth. If the danger is to the dreamer or the thinker, people may find an unhealthy interest in observing al that from afar. But it is not the recognizable, “obvious”, dangers that count, recognition is for the indifferent. The dangers, the risks, are in the experimentation, the doing of things outside correct thought that are tied to getting one thinking. If you are not on the lookout you will perceive nothing: “they often remain hidden and barely perceptible”. Hidden in plain sight, if you are willing to use the eyes of the mind.

...(more)

via Synthetic_zero

_______________________

Pawel Kuczynski

_______________________

The scream of geometry

Andrzej Tichy

(modified excerpts)

Translation by Linda Rugg and Andrzej Tichy

eurozine

(....)

These things are on your mind as you sleep: (1) a landscape (2) two bodies (that is: one animal and one human) (3) the car. The landscape includes the rain. The car includes the bottle. The human includes the eye and the hand. The animal includes the idea of mortality. The rain includes the soldier. The bottle includes the idea of Albania. The eye includes the mother. The hand includes the wall. The idea of mortality includes the witness. The soldier includes the father, the idea of Bulgaria the names, the mother the end, the wall the moment, the witness the shot, and the shot the shot.

[...]

Animals, landscapes. Direction, journey. One hundred soldiers shooting a Romanian policeman. A Macedonian. What is your image of this? You anticipate – but what? Which words are included? One hundred professional boxers shooting an Algerian news announcer. There are deserts, oceans, mountains, lowlands, savannas. Then there are evergreen forests, broadleaf forests, cultivated soil, tundra. Finally glaciers, prairies, pastureland, tropical rain forests, and taiga. Rank these. Animals, landscapes. One hundred Lebanese shooting a Belarusian maid. An infinite number of ways of not knowing. But the number of directions is infinite only from a mathematical perspective, in reality it is finite to such an extent that it spoils the whole journey.

...(more)

_______________________

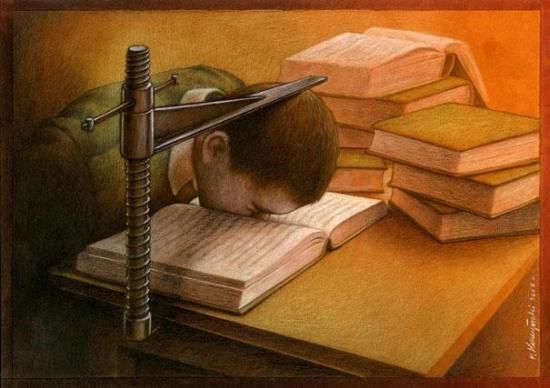

Pawel Kuczynski

_______________________

It’s the sea

refusing to be worn.

Any laugh is a laugh at structure

the audacity of it

to carry off

our share. Our brevity. Only a fool, or the inspired folk

would laugh at the sea,

listen to its silver-tongued absurdities.

All along,

stretched out

under your stone shoulder, holding sun up

one’s live long day.

The smell of salt haunts

an answer—

a village with the

howls

mad howling, an answer for the gibber of waves:

castanets

of broken plates

cackling at the edge of town.

—Tamas Panitz

EyelandThe Cuttyhunk Photographs of Charlotte Mandell

with texts by Lynn Behrendt, Billie Chernicoff,

Robert Kelly, and Tamas Panitz

Metambesen

exploring "the flanges of words"

As citizens in the commonwealth of language, we are anxious to make new work freely and easily available, using the swift herald of the internet to bring readers chapbooks and other texts they can read and download without cost. The first publication in this series is Eyeland, photos by Charlotte Mandell with texts by Lynn Behrendt, Billie Chernicoff, Robert Kelly, and Tamas Panitz.

In future weeks, we will make more texts available, including the long poem The Language of Eden by Robert Kelly.

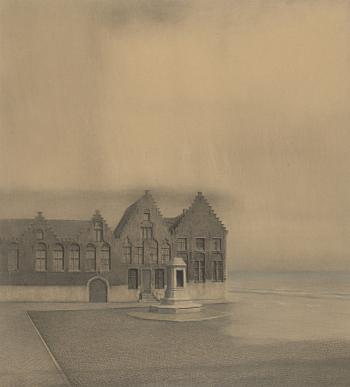

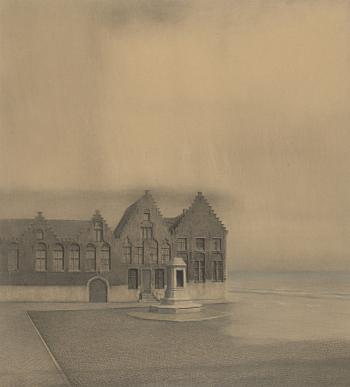

Abandoned City

1904

Fernand Khnopff

b. September 12, 1858

_______________________

An Alchemical Journal (6)

Robert Kelly

presented by Pierre Joris

(....)

It has been my intention to banish all learning from these pages. Only what I have stood under will serve our purposes, gentlemen. Say the blessing &, we will begin. When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one being to sever the biological bonds that have held it to life & amber waves of grain. The purple mountain’s majesty (Yesod) above the fruited plain (Malkuth). Learn the colors. Defer invention. Isnt it just like a burnt-out painter to invent the telegraph. What hath man wrought indeed. I know so little of history I can almost breathe. ...(more)

_______________________

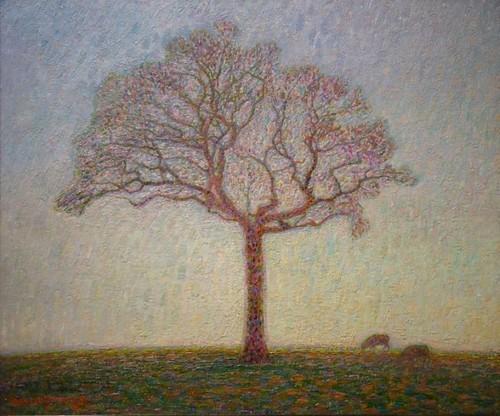

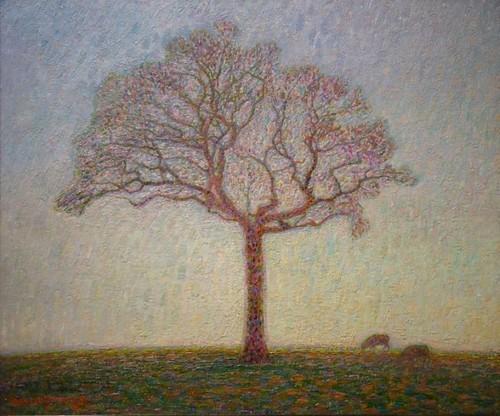

Clear Sky

2011

Unseasonal

Stephanie Valentin

_______________________

mapping space in fiction:

joseph frank and the idea of spatial form

Aashish Kaul.

3:am

(....)

Joyce was among the first, if not the first, to upend, after the manner espoused by the Russian Formalists, the traditional hierarchy of form and content in the novelistic tradition. But unlike them, and perhaps unaware of them, Joyce here offers a more nuanced understanding of the creative process, which does not hasten to remove the artist entirely from his creation, but allows him to fade into it, becoming an invisible presence, behind or beyond or above his work though still very much there.

As Joseph Frank points out in his early study from 1945, Spatial Form in Modern Literature, Joyce, in Ulysses, works with the assumption that his readers are Dubliners, intimately acquainted with Dublin life and the personal history of his characters, thereby allowing him to refrain from giving any direct information about them; information that, contrary to his intentions, would have betrayed the presence of an omniscient author. What Joyce does, instead, is to present the elements of his narrative in fragments, as they are thrown out unexplained in the course of casual conversations, or as they lie embedded in the various strata of symbolic reference, allusions to Dublin life, history, and the external events of the twenty-four hours during which the novel takes place. The factual background, which otherwise is so conveniently summarized for the reader, must be reconstructed in this case from fragments, sometimes hundreds of pages apart, scattered through the book. As a result, Frank argues, the reader is forced to read Ulysses in the manner he reads modern poetry – continually fitting fragments together and keeping allusions in mind until, by reflexive reference, he can link them to their complements. Indeed Joyce himself, although his model was Aristotle, says as much of Ulysses in a letter to Ezra Pound of 9 April 1917: ‘I am doing it, as Aristotle would say – by different means in different parts.’

Taking his cue from Sergei Eisenstein, Frank observes that the juxtaposition of disparate images in a cinematic montage automatically creates a synthesis of meaning between them, which supersedes any sense of temporal discontinuity. This is equally true for the poetry of Mallarmé, Pound, and Eliot, as it is of the modernist novels of Faulkner, Woolf, and Dos Passos. Frank extends this thesis from Joyce and Proust to Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, but the same may well be said about a disparate list of works from Nabokov to John Hawkes, Julio Cortázar to Italo Calvino. Indeed the study of spatial form in narrative is ever more relevant today than any time in the past.

...(more)

_______________________

Water Cycle 2 (undercurrent)

2011

Unseasonal

Stephanie Valentin

via junk for code

_______________________

Reading Violette Leduc’s La Bâtarde

Deborah Levy

Dalkey Context N°14

“At the age of five, of six, at the age of seven, I used to begin weeping sometimes without warning, simply for the sake of weeping, my eyes open wide to the sun, to the flowers. . . . I wanted to feel an immense grief inside me and it came.”

La Bâtarde (1964) is a harsh title for an autobiography that is full of animals and children and plants and food and weather and girls falling in love with girls. It’s true that Violette Leduc was the illegitimate daughter of a domestic servant who was seduced by theconsumptive son of her employer, but to choose such a melodramatic and reductive title, “The Bastard,” tells us how hard it was for Leduc to escape from the way her mother described her, and in that description gave her daughter an internal crucifix on which to nail her life’s story.

It’s not surprising, then, that the furnace at the center of Leduc’s autobiography, and indeed all her writing, is stoked by her ambivalent steely-eyed mother, of whom she writes, “You live in me as I lived in you.” Yet if the young Violette’s tears spill from eyes that are open to the sun, the older Violette’s words spill from the same place too. She is not blinded by her tears, nor are her eyes shut to the pleasures of being alive. Which is to say Leduc was a writer very much in the world despite the distress she suffered all her life. What’s more, she was a writer who was going to give maximum attention to the cause of her distress and create the kind of visceral language that often irritates men and makes women nervous.

...(more)

Foreword to Violette Leduc’s La Bâtarde

Simone de Beauvoir

(....)

“I am a desert talking to myself,” Violette Leduc wrote to me once. I have encountered beauties beyond reckoning in deserts. And whoever speaks to us from the depths of his loneliness speaks to us of ourselves. Even the most worldly or the most active man alive has his dense thickets where no one ventures, not even himself, but which are there: the darkness of childhood, the failures, the self-denials, the sudden distress at a cloud on the sky. To catch sight suddenly of a landscape or a human being as they exist when we are absent: it is an impossible dream which we have all cherished. If we read La bâtarde it becomes real, or nearly so. A woman is descending into the most secret part of herself and telling us about all she finds there with an unflinching sincerity, as though there were no one listening.

“My case is not unique,” says Violette Leduc at the beginning of this narrative. No; but it is singular and significant. It demonstrates with exceptional clarity that a life is the reworking of a destiny by freedom.

...(more)

On Violette Leduc: Interviewing Sophie Lewisasymptote

(....)

... my work on Leduc was very slow. I felt that I needed to make decisions about tense, about tone, about degree of disclosure for almost every sentence. There seemed to me to be an oscillation between an almost forensic, dispassionate detailing of thought and feeling, and a lyricism that aimed to paint feeling more passionately—yet Leduc would never intentionally sacrifice clarity or exactness. So I somehow had to marry the two impulses all the way. It was tough work.

(....)

I’m wary of translations that are guided more by the translator’s personal approach than by their feel for the text. I do occasionally turn down books for which I don’t think I have much sympathy—that’s a principle. I don’t have the flexibility (yet?) or the command of English or simply the ear to translate anything and everything. I’m much surer with some voices than with others. I think translators should have a commitment of sympathy to the texts they work on and be open about this. Of course I’m ready to work hard to capture and recreate a new or challenging voice. But there’s no gain in working against one’s personal linguistic grain.

...(more)

_______________________

The Day Comes to an End

Fernand Khnopff

1891

_______________________

The Death of Adulthood in American Culture

A. O. Scott

nyt

Adulthood as we have known it has become conceptually untenable. It isn’t only that patriarchy in the strict, old-school Don Draper sense has fallen apart. It’s that it may never really have existed in the first place, at least in the way its avatars imagined. Which raises the question: Should we mourn the departed or dance on its grave?

_______________________

An Investigation Into the Reappearance of Walter Benjamin

Adam Leith Gollner

Hazlitt

History tells us that the influential German literary critic died more than seventy years ago. So how is it then that Benjamin is now out doing lectures and has published a new book?

_______________________

So much of therapy – and I use that term precisely – is about making other people comfortable and society feel safe. Analysis differs in that it suspects that accommodation is the problem the analysand suffers from.

-

larval subjects

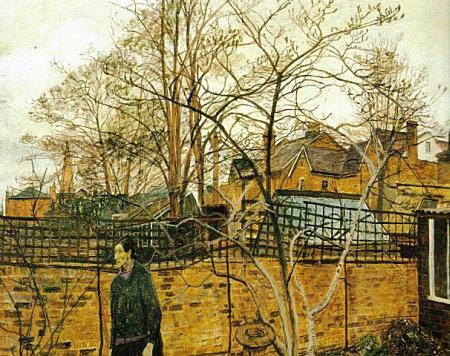

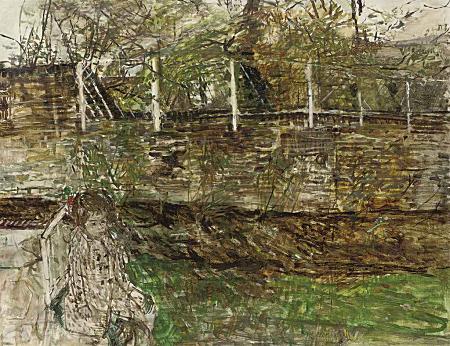

Carel Weight

b. September 10, 1908

_______________________

Four Poems

Alan Gilbert

conjunctions

Dumb Luck

(....)

We’ve come so far, and yet we’ve barely left

the porch. Still, there are children involved,

and monsters to defeat, some of which are inside me.

Luckily, they’re susceptible to spells resting

our shrunken heads on a mushroom blooming

everywhere else amid the knife play banned

along with opposable thumbs. Each new era

gets shorter and shorter. Soon they won’t

bother to call our names, as every desire

exceeds its object, even in the dark,

and I’m a machine of consequence, such as

Operation Empty Candy Wrappers is in full effect.

Right here, right now. There is no other place

I want to be. Unless we’re talking about a medevac.

Or maybe just more meds and a refrain

that goes hurt, hurt, hurt I took on tour with me

to sell T-shirts along with a round of hangman,

because when a hum tickles between the teeth,

a poem is close to being finished.

...(more)

Allegories of Art, Politics, and PoetryAlan Gilbert e-flux

(....)

In a world where a fundamental strategy of ruling ideologies is to make themselves appear natural, the absurd can be its own form of critique. “Allegories are, in the realm of thoughts, what ruins are in the realm of things,” Walter Benjamin writes in The Origin of German Tragic Drama.6 Allegories need time to unfold, but all time is scented with death—to use a description in the spirit of Benjamin’s analysis of the German baroque. The danger with allegory is that it so easily turns into myth when lifted out of time and history. Hence Benjamin’s desire to keep allegory directed toward death and ruins.

...(more)

more poems by Alan Gilbert 1 2 3

Alan Gilbert in the Boston Review

_______________________

Waiting

Carel Weight

_______________________

poems by Romanian poet Andra Rotaru

translated by Florin Bican

Asymptote

The Voice

(....)

today I’ll pretend:

every touch is voluntarily guided. we’re leaving behind

the abandoned territories

I cannot walk

straight. we are getting into each other’s way,

you laugh and your jaws then lock back.

we’re seemingly serene, I’ve got to walk straight:

you can walk.

each of our inclinations,

the most crooked and cleanest of them,

the wide-open mouth of a child

twisted by atrocious language.

...(more)

_______________________

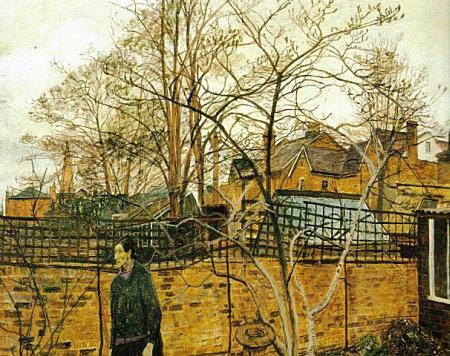

The Silence

Carel Weight

1965

_______________________

The Naysayers

Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, and the critique of pop culture.

Alex Ross

(....)

The Internet threatens final confirmation of Adorno and Horkheimer’s dictum that the culture industry allows the “freedom to choose what is always the same.” Champions of online life promised a utopia of infinite availability: a “long tail” of perpetually in-stock products would revive interest in non-mainstream culture. One need not have read Astra Taylor and other critics to sense that this utopia has been slow in arriving. Culture appears more monolithic than ever, with a few gigantic corporations—Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon—presiding over unprecedented monopolies. Internet discourse has become tighter, more coercive. Search engines guide you away from peculiar words. (“Did you mean . . . ?”) Headlines have an authoritarian bark (“This Map of Planes in the Air Right Now Will Blow Your Mind”). “Most Read” lists at the top of Web sites imply that you should read the same stories everyone else is reading. Technology conspires with populism to create an ideologically vacant dictatorship of likes.

This, at least, is the drastic view. Benjamin’s heirs have suggested how messages of dissent can emanate from the heart of the culture industry, particularly in giving voice to oppressed or marginalized groups. Any narrative of cultural regression must confront evidence of social advance: the position of Jews, women, gay men, and people of color is a great deal more secure in today’s neo-liberal democracies than it was in the old bourgeois Europe. (The Frankfurt School’s indifference to race and gender is a conspicuous flaw.) The late Jamaican-born British scholar Stuart Hall, a pioneer of cultural studies, presented a double-sided picture of youth pop, defining it, in an essay co-written with Paddy Whannel, as a “contradictory mixture of the authentic and the manufactured.” In the same vein, the NPR pop critic Ann Powers wrote last month about listening to Nico & Vinz’s slickly soulful hit “Am I Wrong” in the wake of the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, and catching the song’s undercurrents of unease. “Pop is all about commodification: the soft center of what adapts,” Powers writes. “But sometimes, when history collides with it, a simple song gains dimension.”

(....)

There is no telling how Adorno and Benjamin might have negotiated such contemporary labyrinths. Perhaps, on a peaceful day, they would have accepted the compromise devised by Fredric Jameson, who has written that the “cultural evolution of late capitalism” can be understood “dialectically, as catastrophe and progress all together.”

These implacable voices should stay active in our minds. Their dialectic of doubt prods us to pursue connections between what troubles us and what distracts us, to see the riven world behind the seamless screen. “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism”: Benjamin’s great formula, as forceful as a Klieg light, should be fixed as steadily on pop culture, the ritual apparatus of American capitalism, as it has been on the art works of the European bourgeoisie. Adorno asked for only so much. Above all, these figures present a model for thinking differently, and not in the glib sense touted by Steve Jobs. As the homogenization of culture proceeds apace, as the technology of surveillance hovers at the borders of our brains, such spaces are becoming rarer and more confined. I am haunted by a sentence from Virginia Woolf’s “The Waves”: “One cannot live outside the machine for more perhaps than half an hour.”

...(more)

_______________________

Carel Weight

_______________________

e-flux journal issue 57: The End of the End of History, Issue Two

with Arseny Zhilyaev, Jonas Staal, Hassan Khan, Miran Mohar, Sotirios Bahtsetzis, Eduardo Cachucho, Bilal Khbeiz, Suzana Milevska, Keti Chukhrov, Knut Åsdam, Edit András, and Ilya Budraitski

Hope in a Hopeless SituationIlya Budraitskis translated from the Russian by Thomas Campbell

Why is there no antiwar movement in Russia? Why are so few people willing to take to the streets to publicly accuse the government of furthering the war in Eastern Ukraine? People who supported the March 15 peace march in downtown Moscow still pose these questions to each other. Their numbers are constantly shrinking, but the point is that even those people who still support the spirit of protest no longer have any confidence that protest can change anything.

If the new war (or prewar) footing into which Russian society is sinking deeper has a point of consensus that unites different social and cultural strata, it is the smothering, eerie awareness of society’s total powerlessness in the face of interstate conflict. The flood of news has overwhelmed the already fragile system of coordinates used by individual citizens. Their psyches cannot withstand the strain, surrendering to the unknowable, opaque logic of events, a logic seemingly less and less amenable to anyone’s specific will. “It is not the mind that controls the war, but the war that controls the mind,” wrote Leon Trotsky about a war whose start one hundred years ago has been somewhat timidly commemorated this summer.

...(more)

Léon De Smet

d. September 9, 1966

_______________________

Passion for Solitude

Cesare Pavese

Born: September 9, 1908

Translated by Geoffrey Brock

(....)

All things become islands before my senses,

which accept them as a matter of course: a murmur of silence.

All things in this darkness—I can know all of them,

just as I know that blood flows in my veins.

The plain is a great flowing of water through plants,

a supper of all things. Each plant, and each stone,

lives motionlessly. I hear my food feeding my veins

with each living thing that this plain provides.

The night doesn’t matter. The square patch of sky

whispers all the loud noises to me, and a small star

struggles in emptiness, far from all foods,

from all houses, alien. It isn’t enough for itself,

it needs too many companions. Here in the dark, alone,

my body is calm, it feels it’s in charge.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

peripateticism in robert walser

Shawn Huelle

3:am

To walk, we have to lean forward, lose our balance, and begin to fall. We let go constantly of the previous stability, falling all the time, trusting that we will find a succession of new stabilities with each step.

— Robyn Skynner

Robert Walser’s work is defined by the action of walking. A walk is an attempt to remain upright while continually moving forward. So is an essay. This essay proposes to take two large steps (made up of many smaller steps). It will attempt to define the concepts behind walking in Walser’s work, and then show the where and how of those concepts in several examples of Walser’s writing. It will attempt to remain upright. It will attempt to move forward. It may stride. It may tiptoe. It may circle back or zig-zag. It may even lose its balance. It will attempt to catch itself.

(....)

Walking, among other things, is also an act of self-effacement: while out on a walk, one begins to lose oneself in one’s surroundings. Walter Benjamin notices this in Walser’s writing: “Everything seems lost; a surge of words gushes forth in which each sentence only has the task of obliterating the previous one” (emphasis added).

This self-effacement is related to Walser’s ideas of servility and becoming zero. Instead of losing oneself in one’s surroundings on that walk, one realizes one’s smallness in comparison. In his essay “Unrelenting Style,” Martin Walser (no relation) not only describes how this realization works, but also that it becomes part of Robert Walser’s writing practice: “Instead of letting go, a person has oppressed himself a little. And lo and behold, he has a much clearer sense of himself as his own oppressor. . . . this becomes method.” Elias Canetti understands this servility (for what is servility if not self-oppression?) in terms of the fear evinced above by Kudszus: “His work is an unflagging attempt at hushing his fear. He escapes everywhere before too much fear gathers in him (his wandering life), and, to save himself, he often changes into something subservient and small.”

Another aspect of this smallness is Walser’s use of bricolage. The Oxford English Dictionary cites the word bricolage as being rooted in the French word bricoler, which means “to do small chores” (emphasis added). Bricoler, in turn, has a Middle French sense of “to go to and fro.” The word bricolage itself means “construction or . . . creation from a diverse range of materials or sources,” and carries the connotation of “use of what is at hand.” Peripatetic literature is by necessity bricolage in that it is always appropriating what the eye sees next. Peter Bichsel has the following to say about Walser as bricoleur and walker: “He takes whatever he happens to need at the moment”; “[h]e doesn’t invent walking, it’s quite simply what’s nearest at hand—when he wants to describe himself he has to describe a walker.” And in a much quoted, but never fully translated prose piece, “Eine Art Erzählung,” Walser has this to say about himself: “If I am well-disposed, that’s to say, feeling good, I tailor, cobble, weld, plane, knock, hammer, or nail together lines.”

...(more)

_______________________

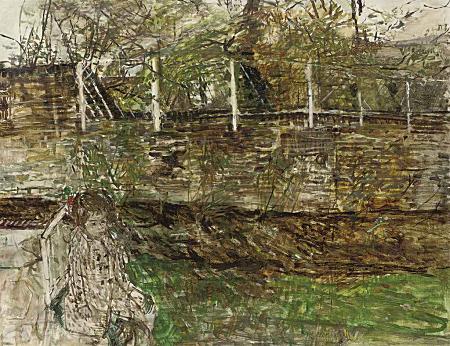

Léon De Smet

_______________________

Poems by Cesare Pavese

Translated by Richard Jackson

Numéro Cinq

>The Boy That Was In Me

I want to know why the grave of evening settled in the meadow.

Perhaps it was because I collapsed, exhausted from sunstroke,

Pretending to be some wounded Indian. In those days the boy

Tried to escape loneliness by seeking models for ancestors,

And drew his imagined painted arrows and shook his lance.

The evening sky itself was colored with war paint.

Every day the air was so fresh, and the aroma indeed was

So plush, so deep, from sprays of flowers that were also

Reddish gray, and then suddenly the clouds and sky

Caught fire among the early stars. The boy turned

To the village feeling he should preserve it by celebrating it.

But the sunset dulled his senses. It seemed best to squint

So he could enjoy and embrace what he saw. As if immersed in water.

...(more)

.....................................................

Translation, Adaptation and Transformation: The Poet as Translator

Why translate? Kenneth Rexroth, one of the most influential translators, writes in his essay, “The Poet as Translator,”– “The writer who can project himself into exultation of another learns more than the craft of words. He learns the stuff of poetry.” Translation is at the heart of poetry– a poet like Rilke writes in his “Ninth Elegy” that when the poet

returns from the mountain slopes into the valley,

he brings, not a handful of earth, unsayable to others, but instead

some word he has gained, some pure word, the yellow and blue

gentian. Perhaps we are here in order to say: house,

bridge, fountain, gate, pitcher, fruit-tree, window–

at most: column, tower….But to say them, you must understand,

oh to say them more intensely than the Things themselves

ever dreamed of existing.

Rilke’s notion that words only metaphorically stand for ideas, sensations and feelings suggests that they are themselves a form of translation. Of course, this could lead us quickly into a maze of problems and suggest that even a poem in our own language must be “translated.” What is at issue in translating poetry is the very nature of poetry, and the very nature of language. The main problems and debates that arise concerning the translation of poetic works occur when one realizes to what extent the essence of a poem lies, as Rilke and Rexroth suggest, beyond the words per se.

(....)

My personal history of ideas by poet-translators on their art is a far ranging one that extends from the Romans like Catullus who saw it as a “combat” with the original, to poets like Petrarch and Samuel Johnson who judged a version by its effect in the so called “target language,” to Robert Lowell’s and Alexander Pope’s loose “imitations.” I know that some of these practices would startle if not horrify most of my language teachers. Yet even a respected academic like Wilhelm Humbolt, in his introduction to his translation of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, says: “the more a translation strives toward fidelity, the more it ultimately deviates from the original, for in attempting to imitate refined nuances and avoid simple generalities it can, in fact, only provide new and different nuances.” This is perhaps why a poet like Jane Hirshfield, also a translator from Japanese, writes: “Translation’s very existence challenges our understanding of what a literary text is.” I think what has intrigued me about the various possibilities of various kinds of translation is precisely that challenge; it offers a way to understand my native language better, to pay more conscious attention to kinds of detail that I approach on a more subconscious level in writing my own poems, and to appreciate some relationships between my own poems and those of poets in another language with whom I have found a kindred spirit.

...(more)

_______________________

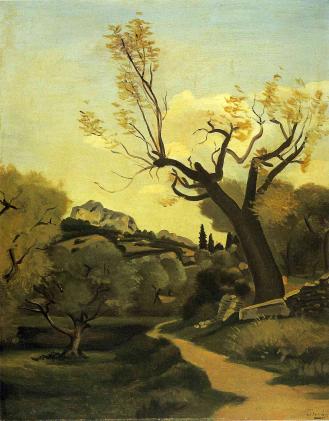

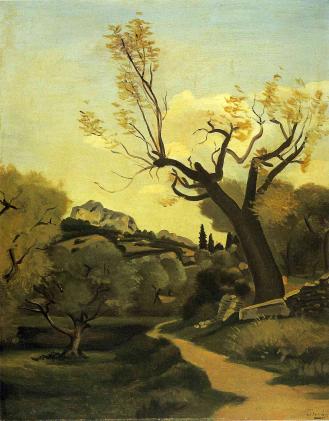

photo - mw

The road and the tree

André Derain

d. September 8, 1954

_______________________

Abstract

By Hsia Yü

Translated by Steve Bradbury

Leaping past “the calamity of love and

the aloneness of not loving” and all manner of other for instances I meander

back to the corner grocery and see

five syllables on a wall—“Fresh Cuttlefish Roe”—then off I go again

to the arts and craft supply store to buy

50 oil pastels 50 individually wrapped colors that each

emit a tiny sigh as it passes

through the register I listen

to the sound of each color passing the sorrow

love gives rise to is quite enough to sway

me. The sorrow alone can make a person feel

quite extraordinary can make a person far more capable

of coping with those problems that come up

smitten with the whole kit full of delicious maliciousness

unexpectedly

expressive (how the words carry us forward) our story

is cut short caught up

in someone else’s

for

if we are to presuppose that every single person is the best possible

casting choice to play the lead in his or her own story ...

(....)...(more)

TWO LINES Online

Center for the Art of Translation

_______________________

The Bagpiper at Camiers

André Derain

c.1911

_______________________

bartleby politics: on disavowal, derangement, and drugs

Jake Nabasny

3:am

As I lay in this bed, slightly dizzy with a minor hangover, I am reminded of Marcel Proust in his cork-lined room. He was always a sick child, but later in life his illness restricted him to his bed for all but a single hour of the night. He could only leave his room at that unique hour of the night when the late-night drunks were sleeping and the early-morning workers had not yet woken up. The air was moist and easy to breathe even though his illness was intensifying. Despite being so reclusive, Proust loved to throw parties in absentia. With his hour of freedom, he would visit the halls in which parties were thrown. Constantly feverish, he walked around in a gaudy coat with a fur-lined hood; Proust was an Eskimo in a desert. What better hero could there be to begin this meditation than one who experienced all kinds of displacements, dispersions, delays, derangements, and departures?

When many read Proust they see a plethora of anchors, like graveyards of old nautical vessels that have not moved in the past fifty years and probably will not move for another fifty. A history is built and links to the past are constantly made. One imagines the entirety of the Search to be consisting of traces and recollections. This could not be more wrong. Proust’s brilliance lies precisely in his explication of the opposite of this interpretation. What connects Proust to his grandmother’s boots is not remembrance or nostalgia, but delirium. The very proliferation of signs and the impossibility of an absolute reading (viz. an absolute origin) is what the Search truly discovers. In other words, it is not the destination that the reader discovers at the end of the Search, but searching itself.

Proust introduces a new polarity, one that is usually ignored, but more often miscomprehended. Anchors and memory define one pole, while the other is designated by wild oceans and delirium. According to this framework, one can begin to understand state violence, the prohibition of drugs, Western epistemology, human rights, behavioral health clinics, and several other politically-charged topics. Proust provides a new revolutionary strategy by re-conceptualizing power structures. Following this line of thought may be enlightening for some, but for those to whom it speaks directly, it will be intoxicating. At this point we must depart from the Proust anecdote (which is also an antidote) and turn to a web of texts that contribute to a general theory of disavowal.

...(more)

_______________________

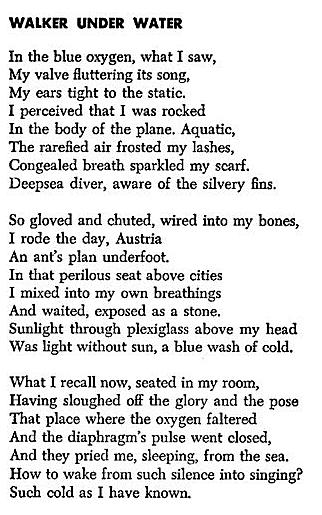

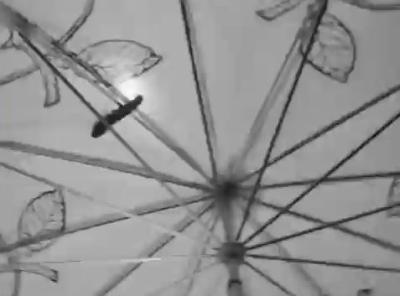

Silence Has No Wings

Kazuo Kuroki

(1966)

full film - youtubevia

_______________________

Drunken Boat Issue 19

Lucas Klein translating Li Shangyin

Untitled

Time to meet is hard to find

and parting, too, is hard

The east wind has no force

and a hundred flowers fail

Unless spring silkworms

reach their death

silk cannot be spun

When waxy candles

turn to ash

will tears begin to dry

In morning’s mirror

only worried

about her temples turning white

She recites at night

while I’m sure she feels

the chill glow of the moon

From this place

to Mount Penglai

is just a little road

Bluegreen bird indulge me please and spy a little glance

...(more)

the inaugural issue of Drunken Boat’s translation section

_______________________

Effect of Sun on the Water

André Derain

1906

_______________________

Lightning Storm Mind:

Pre-Ancientist Meditations

Max Cafard

exquisite corpse

Heed the Word of Our Ancestor! The Way is obscure, but it is the Way. The Logos is the Way. This Way is obviously obscure and obscurely obvious.

The Naturing of Nature is Lightning Storm Mind. Awakening Mind has a Lightning Storm Nature. Thus stroke Heraclitus.

Our Obscure Ancestor taught that “you can’t step into the same river twice.” Translation, at the risk of falling into the icy waters of unsalutary clarity: “Step into the river!”

“For two and a half millennia, poor creatures will learn to forget how to step into the river. For two and a half millennia, poor creatures will learn to step only into their ideas.”

Will these poor creatures survive all this unlearning? Will the river survive all this forgetting?

The world is in fragments.

The world was born whole, but everywhere it is in fragments.

The world was born whole and not whole, but everywhere it is in fragments.

(....)

In short, awakened being, being awakened, is surregional exploration! We become Hidden Nature uncovering Hidden Nature, both having been buried under layers of brute Reality.

Yet, brute reality prevails. As Our Ancestor predicted, in Late Civilizationism, we murder to dissect. Murderous clarity reigns over the obscurity of life, the vagueness of the Way.

Dissectarianism emerged with the religious fundamentalism and obsessive literalistic reductionism of sixteenth-century protomodernity.

Dissectarianism triumphed with the archic and agoric fundamentalism of political and economistic pararationality, raison d’état and raison d’achat.

Dissectarianism perfected itself ideologically in dissectarian analytical technological pararationality, and its Evil Twin, dissectarian analytical philosophical pararationality. We are left with the spiritual desolation of dystopian dissectarian paranormality on Evil-Twin Anti-Earth.

Still, the hidden remains hidden, and continues, with imperious subtlety, to unhide itself. Our Ancestor warned that “unless you expect the unexpected you will never find it.” Or worse, that we will find it without finding it.

We all have a Ghost Problem.

...(more)

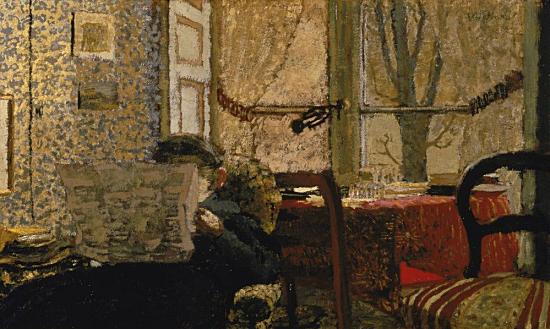

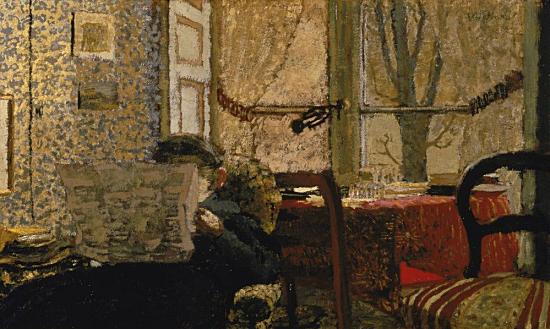

Self portrait in a bamboo mirrorÉdouard Vuillard

1868 – 1940

To tell the truth, if painting and my work have never so genuinely interested me, I'm still of the opinion that existence itself, and the relationship people have with each other or God, if you will, are the main thing, the rest is only consequence, the clothing which has taken its folds according to our gestures....

Edouard Vuillard

from a longer quotation at flowerville

_______________________

Conversations & Silence

Craig Hickman

I

Every day we wake to absence, to transparency

Surrounding us like thoughts of death or ancestors;

Something rare dips its powers ladling our minds,

Energies of other times rising with each cupful of wine.

Heartbeat and spirit, thump of that drum, leather clowns;

Rubble and hoof-prints on clouds, conversation

Of lost memories delving along the riverfront lodge.

Old battles with the fathers have settled down now,

and we wander off from that marsh-grounded silence as ghosts.

Our eyes see now what is in ruins: dead to us in cracked poems.

The Lamentations sing to us of lost greatness among bones,

And fragments of voices echoing along the edges of darkness like boasts.

...(more)

dark ecologies

~ poetry of love, death, and laughter

Craig Hickman

_______________________

Scarborough Beach

Atkinson Grimshaw

b. Sept. 6, 1836

_______________________

Theory, A City: Introduction

Lisa Robertson

lemon hound

The feminist writers of Montréal have altered their city irrevocably. When women write about and from the cities they live in, they are transforming the material city into a web of possibility and risk. The description of the city bends back on itself — it not only represents, it opens up a site for the political imagination. Through the fictive and theoretical act, the city is re-inscribed as a space for radical otherness. Montréal is more than its official civic history. In this volume, it figures as a character, a velocity — its streets and cafés and bars are exerting forcefields. It’s a gathering of urgencies, errancies, overflowing critiques, pausing to make in the movement of women’s language what the political economy has disallowed.

The feminist consciousness that Nicole Brossard recognized in the writers she invited to the Sunday theory group in 1983 — what supported it, what permitted it to develop? Why do certain cities at certain times become the stages for intense social and cultural transformation? I think of early 20th century Paris, the city that was a home for so many of the women expatriate writers who have become the crucial figures of modernist literary and intellectual culture — Gertrude Stein, Djuna Barnes, Mina Loy, Mary Butts, Sylvia Beach, Nathalie Barney. From my admiring distance, and across the duration of many friendships, Montréal feels to me to be a place of comparable intellectual generosity and intensity. What generates and supports the networks of friendship, argument, and intellectual collaboration that have caused 20th century women’s writing to consistently develop and strengthen as an urban, cultural, and political force in Montréal and elsewhere? Thinking about and reading the work of these Montréal women now, 25 years later, I am brought to the realization that feminism is one of the scintillating companions of the culture of cities. Feminist culture, discourse and resistance has shaped contemporary urban experience and urban space. Certain writers have claimed the city for feminism, to insist that any city is the vibrant space inflected by women’s voices. There is no city without our voices.

...(more)

_______________________

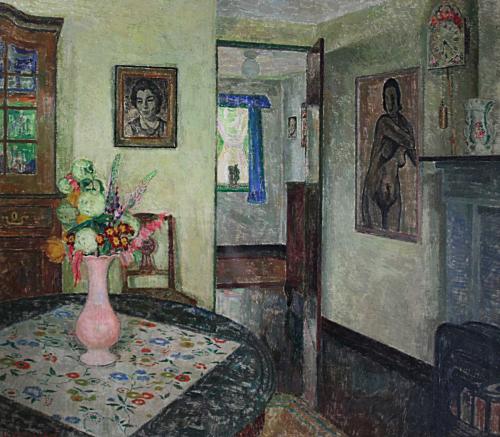

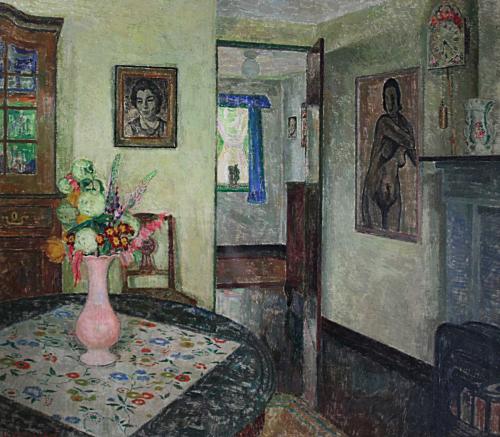

Flowers on a Mantlepiece in Clayes

Édouard Vuillard

c.1932-35

_______________________

OF THE ALWAYS Part Four

Robert Kelly

Indecisive disclosure

a mind without a zipper

the purse-seine savages the sea

and there were words in it

this time, Antietam,

bone,

this time Actium

never now.

History is a lizard basking in the sun.

a series currently unfolding at Mill Of Particulars: The bLog of Robert Kelly

_______________________

An Alchemical Journal (4)

Robert Kelly

presented by Pierre Joris

(....)

So many birds of morning. Elephant on the desk. To each unit of the biological world belongs its proper gesture. We call it lucus, ‘grove,’ a non lucendo, from the fact that it is not bright inside it. Dark birds. The traveller asked for an empty glass. One tusk is longer than the other. In a poem of Rene Char’s we read of deujc pointes semblables, sun shining on two like tips, of the horn of the bull, of the sword that kills him. I have kept him all these years at the door, waiting for one to become empty.

(....) ...(more)

_______________________

Édouard Vuillard

_______________________

Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World

Timothy Morton

reviewed by Cara Daggett

Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World is a queasily vertiginous quest to synthesize the still divergent fields of quantum theory (the weirdness of small objects) and relativity (the weirdness of big objects) and insert them into philosophy and art, which he notes are far behind ontologically speaking. Morton’s wager is that for the first time, we in the Anthropocene are able to see snapshots of hyperobjects, and that these intimations more or less will force us to undergo a radical reboot of our ontological toolkit and (finally) incorporate the weirdness of physics. You know that cozy hobbit world where people tend gardens and think stars are beautiful and flush their excrement into the ‘away’? Well, that world is a fantasy, and now that we can see hyperobjects, that world is at an end, hence Morton’s subtitle. Morton encourages us to adopt an object-oriented ontology (OOO), and OOO tells us that “thinking and art and political practice should simply relate directly to nonhumans”, which is actually not so simple. But more on that later.

So what is a hyperobject? Morton acknowledges that big objects have always already been there, nudging those who would listen toward an ontological reboot, but it has been possible for most people to ignore this. No longer. Morton argues that the ‘hyperobjects’ of the Anthropocene, objects like global warming, climate or oil that are “massively distributed in time and space relative to humans”, have become newly visible to humans, largely as a result of the very mathematics and statistics that helped to create these disasters. As we glimpse them through our reams of data, “[h]yperobjects compel us to think ecologically, and not the other way around”.

...(more)

Society and Space

Delphi Antinous unearthed

Temple of Apollo

1893

_______________________

The End of the World: From Apocalypse to the End of History and Back

Oxana Timofeeva

(....)

I propose, instead of trauma, to talk about catastrophe. The difference between the two is that one cannot really recover after a catastrophe, as one normally recovers after a trauma. Catastrophe is meta-traumatic. It happens absolutely: at the beginning there is—there was—always already the end. Catastrophe defines the borders of a collective and the true sense of what we call history. By catastrophe I mean, of course, what people do to other people or to nature, and what nature or gods do to people: wars, genocide, bomb explosions, hurricanes, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, but also certain legendary events, like the expulsion of humans from Paradise, the Flood, and of course, the Apocalypse. Above all, I am thinking about the catastrophe of one’s own existence, this apocalypse of the now—the irredeemable nature of a single present moment. You cannot change anything; the worst is what just happened: your beloved just died, your child just died, a giraffe in the zoo just died, god died, too, you yourself just died or woke up in your bed in the body of an uncanny insect, like Kafka’s Gregor Samsa.

As opposed to what is usually said, catastrophe’s time is not in the future, but in the present, which we can only grasp as the past, because it flows, just as the waters of the Flood: time itself is catastrophic. Catastrophe is what already happened, no matter how long ago—it happened in prehistory, or it’s happening right now, although people are still expecting some bigger, ultimate catastrophe in the future, as if the previous ones did not really count. I want to make this point as clear as possible. Our collective imagination, overwhelmed by all kinds of pictures and scenarios of a future final collapse—be it another world war, Armageddon, an alien invasion, an epidemic or a pandemic, a zombie virus, a robot uprising, an ecological or natural catastrophe—is nothing but projections of this past-present. We project onto the future what we cannot endure as something which already occurred, or which is happening now. We still believe that the worst is yet to come—it is a perspective, but not a reality, and therefore our reality is still not that bad. A fear of the future and anxiety about some indefinite event (“we will all die”) is easier to suffer than a certain, irreparable, and irreversible horror that has just happened (“we are all already dead”).

...(more)

e-flux 56

_______________________

"Castle Engelbourg (Thann)"

1859

Adolphe Braun

1811-1877

_______________________

Existentialism, the Abject Horrors of War and The Way Of The Heart

Vera Graziadei

(....)

Psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva in Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection argues that the abject horrors of war, however stomach-churning they are, have the capacity to bring us to what Lacan called – The Real, i.e. that which is authentic and true, especially in relation to our own self/being and the infinite. Facing a bloodied, mutilated corpse can produce a spasm within the deep core of one’s being, accompanied by the breakdown of everyday meaning, which leaves one literally beside oneself. This primal physical and emotional response catapults one into a primordial realm of existence, where there’s an acute awareness of human smallness, insignificance, fragility, yet uniqueness, mystery, beauty. Kristeva also argues that oppressive and inhumane institutions, which wield power in the modern world, are built upon the notion that man must be protected from the abject (hence sanitisation of Death). By facing the abject face-to face one tears away the support of these institutions and embarks on the first movement that can truly undermine them.

...(more)

_______________________

Reinventing emancipation in the 21st century: [pdf]

the pedagogical practices of social movements.

Sara C Motta and Ana Margarida Esteves

This issue of Interface aims to make a contribution to the ongoing politics of knowledge of those marginalized, made illegible and spoken-over by the contemporary geopolitics of capitalist coloniality. It engages with the rich heritages of popular pedagogical practices, subaltern philosophies and critical theorisations by entering into dialogue with the experiences, projects and practices of social movements who are at the forefront of developing a new emancipatory politics of knowledge for the 21st century.

In this introduction we situate historically, politically and theoretically the centrality of the pedagogical in both the learning of hegemonic forms of life, social relationships and subjectivities but also in practices of unlearning these and learning new ones. We identify the general themes that emerge from the rich cornucopia of experiences discussed in the issue as a contribution to the mapping and nurturing of the ecology of counter-politics of knowledges flourishing across the globe.

Our intention is that this dialogue and systematisation will itself constitute a pedagogical intervention which can facilitate and inspire experimentation, reflection and collective learning by social movements, communities in struggle, and activist-scholars. We hope that this issue of Interface can play a performative utopic function visibilising the ‘others’ of capitalist coloniality and posing open questions which support the flourishing of multiple grounds of epistemological becoming.

(....) Interface volume 6 issue 1. Movement pedagogies

Interface a journal for and about social movements

_______________________

Entrance to yard

Winton, Minnesota

1937

Russell Lee

Photogrammar

Yale University

a platform for organizing, searching, and visualizing 170,000 historic photographs

The Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information (FSA-OWI)

_______________________

Monoculture beer no more

Other poetries from Ireland

Christodoulos Makris

(....)

Driven by a few committed individuals, there begins to emerge a vital and disparate counter-scene that takes its tune from a newly honed political restlessness. Increasingly, writers who have entered the workings of “Irish poetry” from elsewhere are making their mark with hard-to-ignore activities and statements, while boundaries between poetic practices, genres, interests, and art forms are being — slowly — erased. Political writing does not only take the form of spoken word anthems or performance pieces looking for consensus. Despite much work that still relies on a traditional understanding of what a poem is or how it may come about, with a reluctance to experiment with processes and interrogate forms as well as the minutiae of language and how it’s employed persisting, a stirring has begun.

...(more)

_______________________

September

Shiko Munakata

b. September 5, 1903

photo - mw

_______________________

And we will walk in solitude, sharing our solitude. We’ll walk, empty solitudes, having renounced everything.

And we will meet other solitudes, other walkers-for-nothing. Other departers-for-wider-shores.

And thought will rest inside you. The capacity to think. And you will be part of the springtime, of the blooming spring. Part of the summer.

And every moment will be incomparable because every previous moment is forgotten. And we will see things we have never seen. And beauty will announce itself again, as for the first time.

And the real world will push upwards through our walking feet.

And we will be alone, but with each other, and with the earth.

Nietzsche And The Burbs

_______________________

An Alchemical Journal (3)

Robert Kelly

presented by Pierre Joris

(....)

Being in this city under the sea was submitting himself almost to Ordeal, a testing of a Self (which did not perhaps need to be tested) in the midst of the irrelevant, the unnecessary, the irritant, the abominable. It was a sorrow to be here, to turn from what was his, the terrene airy life he lived in the heart of, to put himself in this fix, the half-day journey down, the being-there in the hopeless knowledge of having to ungo the whole way to get back where he had been, no further, except the furtherness of self-betrayal; yes, that was it he thought (his pen blurring in the hydrosphere), in the destructive element immerse (he quoted), yes, that was it, his joy had been to taste of self-betrayal, see darkingly how far he could go in without destroying the self (....) ...(more)

Mill Of ParticularsThe bLog of Robert Kelly

_______________________

Coastal Landscape in Moonlight

1898

Eilif Peterssen

b. September 4, 1852

_______________________

Harvey Shapiro

_______________________

For William Carlos Williams

Harvey Shapiro

1924 - 2013

My rhetoric imagines you as your rhetoric says you.

You are in the city, drinking coffee,

a morning break. The poem in your head

is neighborly to all you see. Those who

sit next to you are not foreign to your lines.

Impure identities, they fill your poem with essences.

You do not build tombs for posterity

but open spaces where we can breathe

intelligence and the pain of love.

The bread of life is what we die to taste.

I taste it in your poems.

On Harvey Shapiro's 'A Momentary Glory'Norman Finkelstein

A Momentary Glory: Last Poems is a sustained act of inspired writing, the passionate outpouring of a brilliantly gifted poet in the face of age, illness, and mortality. The language is charged with unprecedented gravitas. Yet the work is as edgy as ever, and Harvey never abandons the supple, even jazzy wit that is central to his style. The verbal economy, the razor-sharp lineation, the perfectly timed presentation of detail that are his trademarks — all are subtly at work here, never flashy, still in the service of a poetic sensibility in search of what Harvey always called “the way,” from halakha, the Hebrew term for the Law. ...(more)

A Momentary Glory

Last Poems

Harvey Shapiro; Norman Finkelstein, ed. Wesleyan University Press

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

The Zero-Sum Game of Perpetual War

Bill Blunden

counterpunch

(....)

One could posit that what’s happening in Eastern Europe offers a look-see into the nature of the groups that are calling the shots in the United States. Do they care that their destabilization program in Ukraine provokes a nuclear-armed country or enables neo-Nazis to assume vital positions in government? So far almost 2,600 civilians have been killed in the ongoing humanitarian crisis. While the corporate press does its best to create the impression of a “shining city upon a hill” which aims to “spread democracy” and conduct “humanitarian intervention[v],” a different sort of world power is clearly visible to those who look carefully.

The appalling savagery of radical groups like the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) reflects the appalling savagery of American military incursions. Or perhaps the collective consciousness of the United States has already forgotten over hundreds thousand dead Iraqi civilians [vii] and the long trail of drone induced “bug-splats.” Ruthless men like Genghis Khan didn’t vanish into history books. Oh no, they’re still around. Some of them are right here in the good old U.S.A. It’s just that they’ve replaced scepters with hand-tailored suits and have traded thrones for seats on corporate boards.

Who Are Those Guys?

So just who are the “deciders”? American philosopher John Dewey answered this question in one crisp sentence[xiv]: “Politics is the shadow cast on society by big business.”

...(more)

Coming to School

Vernon Everett Duroc

circa 1920

Pictorial Photography in America 1920

Project Gutenberg

_______________________

Susan Briante : THE PHYSICISTS SAY THE UNIVERSE MIGHT BE

a projection on the edge of a screen shadows by the door

or the boundary between the Muskogee and Cherokee nations

more nothing than anything else

smash the smallest parts to see if nothingness breaks

but there must be another way there’s no reason

in the cosmic order to necessitate human existence

no equation to explain the little arrows

at the end of my fingers—a plate glass above all that I do

and you hold the grease pencil and you move the shipping containers

across the horizon like a sentence about to be said: this morning

I saw the word “dog” in a hair left in the bathtub

and no matter how I turned could not get it to read “god”

Tuesday poem #42 in DUSIE

.....................................................

Interview with Susan Briante

(....)

When I was writing my first book, Pioneers in the Study of Motion, I was really interested in the fragment. After six years in Mexico, there were many stories I wanted to tell, but I knew I was writing in the complicated wake of many other traveler/writers. Instead of trying to tell a story—to offer a version of Mexico—I found myself thinking about the field note: non-linear, observation-based, provisional and speculative—much like the best poems. Rosmarie Waldrop writes: “The glint of light on the cut, this spark given off by the edges is what I am after.” In many of the poems of Pioneers in the Study of Motion, I wanted to use juxtaposition to create sparks like those you see in the contact between two metals—the conquers’ sword and warriors’ shield—or the smoke sometimes observed when the wheels of a plane touch down on the runway. I hoped juxtaposition would draw the reader’s attention to the poem’s surface lest they be fooled into believing they might actually be seeing Mexico rather than a glimpse of my mind.

Before I started writing the poems that would become Utopia Minus, I was reading WG Sebald’s Rings of Saturn. In that book, Sebald proposes to take readers on walks through the English countryside, but actually he creates a journey through syntax and thought and history. Likewise, I wanted my poems to start from a fixed place—a building (often abandoned), a batholith in the Texas Hill Country—but I wanted to challenge myself as to the intellectual distance I could traverse without resorting to collage. I wanted to walk through these thoughts. I love falling asleep somewhere over Kansas and waking up on the tarmac in San Francisco. But I also relish the process of taking things mile by mile, word by word, to notice every historical marker, strip mall, roadside curiosity, to savor every preposition, verb, clause.

...(more)

_______________________

Bopping At Birdland

(Stomp Time)

Romare Bearden

b. September 2, 1911

_______________________

Nigun Poems & Poetics

Jake Marmer

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

Nigun Au Rebours

this song is not an act but erasure

the way other songs reach into you

this one retreats,

taking with it stuff that seemed nailed to the floor

this song is cinematic in its reel

you may find yourself humming its residue

you may wonder who you’re

feeding—

through the song’s straw that ascends

to the pouting mouth

of the vanishing point

...(more)

Jake Marmer's Bop Apocalypse

Poetry, Philosophy, Existential Rants

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Proust’s Questionnaire

John Ashbery

(....)

It’s a question of questions, first:

The nuts-and-bolts kind you know you can answer

And the impersonal ones you answer almost without meaning to:

“My greatest regret.” “What keeps the world from falling down.”

And then the results are brilliant:

Someone is summoned to a name, and soon

A roomful of people becomes dense and contoured

And words come out of the wall

To batter the rhythm of generation following on generation.

And I see once more how everything

Must be up to me: here a calamity to be smoothed away

Like ringlets, there the luck of uncoding

This singular cipher of primary

And secondary colors, and the animals

With us in the ark, happy to be there as it settles

Into an always more violent sea.

- in Ashbery's A Wave: Poems

.....................................................

Ashbery, Proust and Time

John Deming

cold front

(....)

Much of Proust’s prose, much like certain passages in Ashbery’s poetry and creative prose, involves extended sentences that arrive flush with the passing of time; they do their best to hold off the “certitude” or “stopping point” of a period, or the stopping point of a fixed, certain idea. Time is positioned as a human being’s most fundamental problem, and accomplishing whatever work time permits one to accomplish – accounting for time as it passes, and learning from it – seems the appropriate response. This says something about the volume of work that both have produced. Time is the space a person occupies; passed time is “beneath” a person, according to Proust, leaving one standing on higher and higher stilts until they either collapse for good, or extend to a new, unrecognizable set of circumstances. Ashbery notes in “Convex” that days grow “concentrically” around a life, a more useful representation of time than the traditional “linear” timeline. Time is not backwards to forwards; it is a plane, and to feel it passing is to feel warps in the curve of spacetime.

...(more)

_______________________

Handbook of the trees of the northern states and Canada east of the Rocky mountains.

Romeyn Beck Hough

1907

Internet Archive Book Images' Photostream

Flickr

_______________________

Kafka’s literary metamorphoses

Carolin Duttlinger

tls

(....)

In Kafka Translated, Michelle Woods traces the history of Kafka in translation through four examples: the Czech journalist Milena Jesenská, Kafka’s very first translator (and his lover); Willa Muir, whose reputation was largely overshadowed by her husband; and the contemporary translators Mark Harman and Michael Hofmann. Unlike the Muirs, who produced a smooth and “readable” Kafka intended to appeal to a wide readership, recent translators have taken a deliberately “foreignising” approach by sticking closely to the originals. Harman and Hofmann do not try to correct apparent stylistic weaknesses, such as Kafka’s repetitive vocabulary or his over-long sentences and paragraphs – what Harman, paraphrasing Samuel Beckett, calls the “steamroller-like quality” of Kafka’s prose.

...(more)

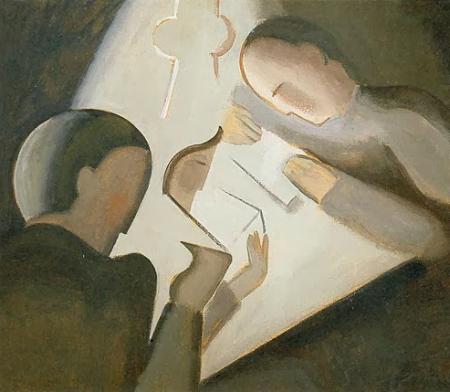

Readers under the Lamp

1913

Willi Baumeister

d. August 31, 1955

_______________________

after revolution: a review of antoine volodine’s writers

Diana George

3:am

“I hate reading ‘difficult authors.’” In this interview filmed in 2011, French writer Antoine Volodine looks pained when asked why he dislikes hearing his books called “difficult.” He counters that his books are only difficult to summarize, not to read. It’s true: the ramifying narrative strands of Volodine’s novels fascinate, but they are almost impossible to describe. Like the fictitious novels penned by one of his writer-characters in the newly translated Writers (Dalkey, 2014; Éditions du Seuil, 2010), Volodine’s books consist of “dark scenes, oscillation between political and mystical spheres, biting humor, nested story lines, tangled interior worlds, portrayal of the drift towards madness or death.” And Volodine’s books present a further difficulty for summary: they belong to a fictional-yet-real literary movement named (by Volodine) “post-exoticism.”

In a “post-exotic” novel, the plot usually begins long after the defeat of an unnarrated “world revolution”; the characters are often revengers or revolutionaries, now imprisoned, or mad, or dead; and the narrative voice shifts among narrators and “surnarrators,” in books-within-books ascribed to various heteronyms—these last are fictional post-exotic writers who sometimes also publish books in our world. (Volodine’s heteronyms with autonomous literary careers include Manuela Draeger and Lutz Bassmann.) Their battle lost, these fictional post-exotics have not conceded defeat or renounced their beliefs; instead, they’ve taken up writing—but post-exotic writing is a lowly, risible act, often consisting merely of tapping on pipes in prison cells, or murmuring or sighing or coughing out words that come to nothing in the end.

Given this complexity, Volodine’s books may sound difficult, to a degree that belies the rapt experience of reading them. And in Writers, the writer-characters struggle with a Beckettian difficulty: how to come to the end of writing. However, even as they try to reach silence, the writers in Writers go on writing—in gripping, poetic, hallucinatory images—after the end of revolution, after defeat or betrayal. ...(more)

_______________________

Unspectacular Landscapes

Claudia Terstappen via

_______________________

Three poems

Dariusz Sośnicki

Translated by Tadeusz Pióro

Leaves

Shake themselves off trees so violently

that drifts rise along curbs

in alleys and under building walls.

Trams plod through strewn streets

lose sight of their tracks and you see them

later roaming the greens

snouts down by the cold earth. The sky

looks at itself in a shop window and everything

is written in a thin, lined notebook. My

well is full of twigs and dust, the tap chokes

on an ice-cube: who sent

these tight clothes to get me?

...(more)

Poems from Altered State - The New Polish Poetryjacket29

_______________________

An Alchemical Journal (2)

Robert Kelly

presented by Pierre Joris

(....)

Only now is it clear that I was walking on that hillside. Midway up the woods there is a fence, & by it a black wet tree. We stopped & planted seeds there, in the middle of the air. There was such silence in the woods, in the wood, & that’s what I’m trying to get away from now. No need for all that silence, no need for all this secrecy, as far as I can see. And there are houses where women sleep. Were we sad because we were silent, & silent because all the secrets had told themselves into the listening rain? Anybody seeing me would have known what was on my mind.

...(more)

_______________________

Words without Borders September 2014: Writing Exile

The Poet Cannot Stand Aside: Arabic Literature and Exile

M. Lynx Qualey

(....)

Migration, banishment, and estrangement have long been themes of Arabic letters. The trope of collective exile, or collective loss of a homeland, has been a separate but overlapping part of the shared imaginative landscape. It took on new force after the 1492 fall of Grenada, after which waves of Jews, Muslims, and others were forced to flee what had been a powerful, diverse caliphate, populated by some of Arabic literature’s most important writers.

These two overlapping threads—personal and collective exile—have been leitmotifs throughout the last several hundred years of Arabic literature. But in the last century, they have moved from the periphery to the center of literary discussion.

...(more)

_______________________

Harbor

1909

Georges Braque

d. August 31, 1963

_______________________

Democracy and the Spectacle

On Rousseau's homeopathic strategy

Chiara Bottici

Public Seminar

In this talk, delivered as 2013 Cassirer Lecture of the University of Gothenburg, I argue that this striking remark must be understood within the more general framework of a critique of the spectacular nature of modern society. If the spectacle is not simply an occasional form of entertainment, but a social relationship that pervades modern society as a whole, how can we escape from it? Rousseau's homeopathic strategy, according to which we should fight an evil through small doses of that very same evil, offers a solution that is crucial for grasping the scope of Rousseau's critique of the spectacle as well as for rethinking the possibility of democracy.

|