|

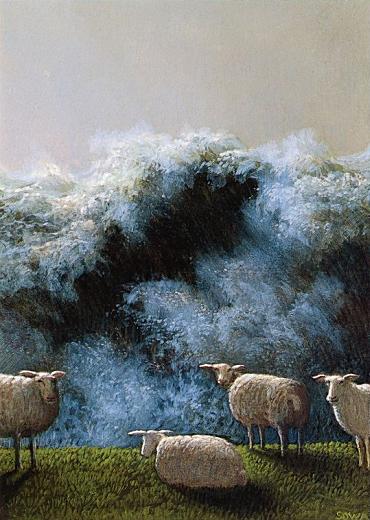

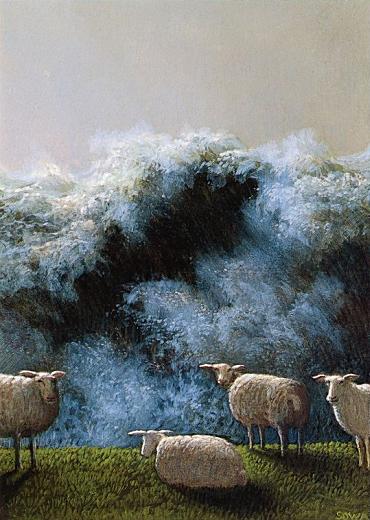

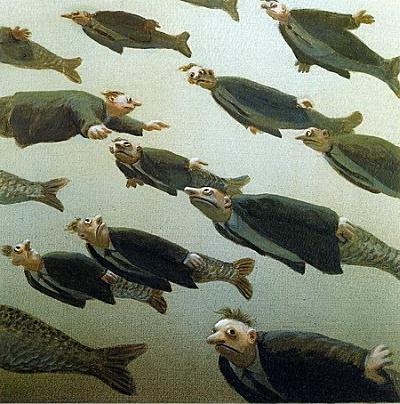

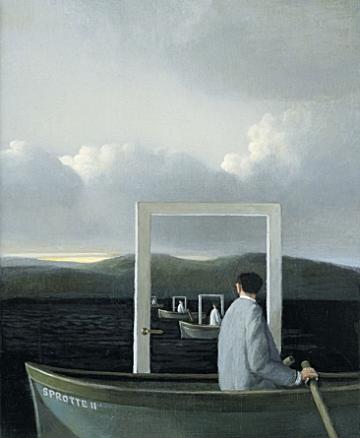

Michael Sowa

via Biblioklept

_______________________

An Alchemical Journal

Robert Kelly

presented by Pierre Joris

the first installment of Robert Kelly's An Alchemical Journal (first published in IO magazine #4, summer 1967 & reprinted in The Alchemist to Mercury, a collection of Kelly's work edited by Jed Rasula in 1981. There will be about 10 installments to be published roughly one every second or third day.

(....)

Silence as instruction. Two kinds of Silence. Negative: silence as abstention from utterance [how to teach poetry]. Positive: silence as a shape to ram down their throats. In their ears. Bodies. Eyes. Shaped silence, against time.

*

Harpocrates is the Aion too. Silence of Hokhma. Silence of Binah. Michael Angelo’s grieving women. Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici, my initiation into the sphere of Binah, into the urgency of poetry. Trey of Spades. Pique-Dame. Prick this woman. Grief. Something held to the lips. Aion. Eis aiona. No time.

(....)

It’s on a hillside, & so much has been in or on or under hillsides. I mean on hillsides but the others came, in, under. I think of the raths & hills my Irishes knew, backparts of my blood, fair dark-haired red-haired men like me who spoke no language I could understand & were my fathers. What if a man desires the acquaintance of his remotest great-grandmother, and she a mere girl, in the matins of the world, walking on the dewed grass of Ireland. What does it mean if a man wants to go into that time before him (though our language says two different things with that word before: “Before Abraham was, I am” but “Before my eyes”), what does it mean if a man wants to step lightly across the Galway field, earliest morning, up to where the mother of his blood walks just as lightly, & to slip his arm around her slim waist, but with his wrist so flexed that the tips of his long fingers brush, press, & half-support the fullness of her right breast, soft loose in her dress?

*

Whoever that man was I would in that fashion have slightly been, whoever he was he knew the hillsides, had maybe walked inside them beyond the tradition of easy enchantments, had maybe seen those cities, worships, inconceivable entertainments, above all had maybe felt the speed of Faery. And if I say all that’s in the hill is hill-stuff, molecules & subtle motions, I have denied nothing.

...(more)

_______________________

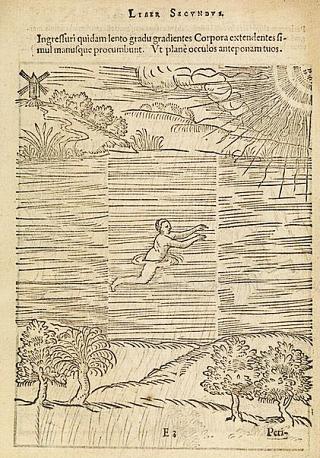

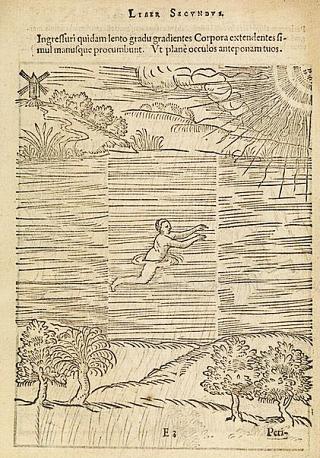

De Arte Natandi

(The Art of Swimming)

Everard Digby

published in 1587

The Public Domain Review

_______________________

Journal of Urban Cultural Studies

Volume 1, Number 1, 1

Félix Guattari and urban cultural studies

Stephen Luis Vilaseca

Félix Guattari’s work in ‘Drawing, Cities, Nomads’ and ‘Space and Corporeity’,

two articles published in 1992, and his final three books, Cartographies schizo-

analytiques/Schizoanalytic Cartographies), Les Trois écologies/The

Three Ecologies and Chaosmose/Chaosmosis, not only

theorize the relationship between subjectivity and the city, but also accompany

the theory with a transdisciplinary call to remodel urban life. Guattari argues

that the type of subjectivity we produce is linked to the type of cities we create,

and vice versa. The world of predatory capitalism of the late 1980s and early

1990s in which Guattari wrote the books and articles reviewed here forced

architects, urban planners, urban cultural studies theorists and activists to

make important ethical and political choices. We are confronted with those

same difficult decisions today. Will we continue to allow our subjectivity and

our cities to be invaded by capitalism? Do we want our unconscious and our

urban spaces to remain enslaved by money? If not, is there an alternative?

Is there a will to change? How do we change? The purpose of this review

article is to revisit Guattari’s analysis of subjectivity and explore its theoreti-

cal and practical relevance for urban studies in both the social sciences and

humanities disciplines. _______________________

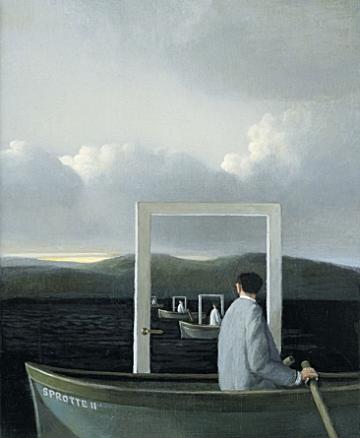

Michael Sowa

_______________________

"Beautiful, stupid, dangerous, life-saving, corrupting, and perhaps all there is."

Joe Wenderoth interview

by Paola Capó-García bomb

(....)

That line in Celan's poem, “Speak, you too,” where he basically says: speak … but keep Yes and No unsplit. Celan, unlike someone like Stevens, is not inclined to give advice about how to write poetry, but here is an exception. The artifice, Celan understands, is beautiful, stupid, dangerous, life-saving, corrupting, and perhaps all there is. I am speaking of the artifice of the poem, as that is the artifice he is speaking of. The artifice of society—its organization of bodies and their sustaining customs—is another matter altogether. The artifice of society—I think of Berryman's Henry in “Dream Song #7”: “For the rats / have moved in, mostly, and this is for real.” And of course one thinks of Marx—the means of production have become so massive, a Frankenstein etcetera. Bottom line is that the situation—in terms of the oncoming nightmare/toxic dump/simulation-trap has made the artifice of poetry obsolete, obscene, obtuse. Nevertheless it goes on, of course, and this fact is at the foundation of my own contempt for a great deal of the contemporary poetry I come across. I agree again with Celan when he suggests that the only poetry that can be taken seriously now is necessarily gray, uncertain (groping, i.e. human presence). I think Celan thought of his poetry as moments in which he was able to get free of artfulness, or art. Similar to Whitman here—proposing poetry as an act of life rather than an act of art. I would like to agree, but I suppose the poems I've been writing bear witness to a life sometimes unable to get free of art.

And perhaps simply: the older you get, the more artificial it all seems.

...(more)

_______________________

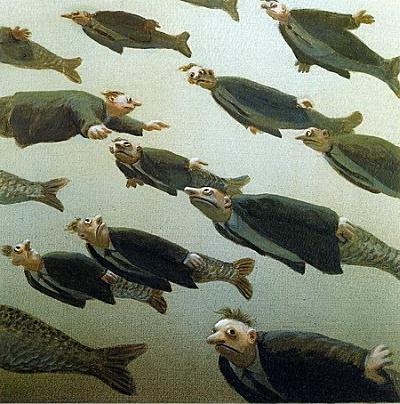

Michael Sowa

_______________________

Wittgenstein’s forgotten lesson

Ray Monk

prospect

Ludwig Wittgenstein is regarded by many, including myself, as the greatest philosopher of this century. His two great works, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) and Philosophical Investigations (published posthumously in 1953) have done much to shape subsequent developments in philosophy, especially in the analytic tradition. His charismatic personality has fascinated artists, playwrights, poets, novelists, musicians and even movie-makers, so that his fame has spread far beyond the confines of academic life.

And yet in a sense Wittgenstein’s thought has made very little impression on the intellectual life of this century. As he himself realised, his style of thinking is at odds with the style that dominates our present era. His work is opposed, as he once put it, to “the spirit which informs the vast stream of European and American civilisation in which all of us stand.” Nearly 50 years after his death, we can see, more clearly than ever, that the feeling that he was swimming against the tide was justified. If we wanted a label to describe this tide, we might call it “scientism,” the view that every intelligible question has either a scientific solution or no solution at all. It is against this view that Wittgenstein set his face.

...(more)

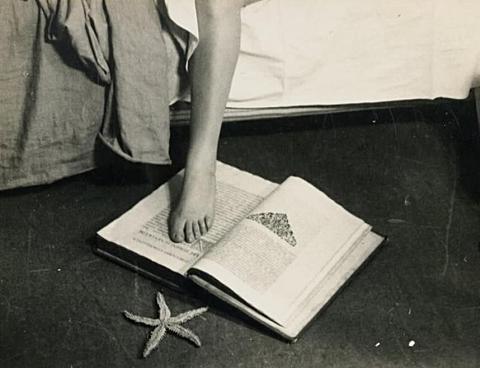

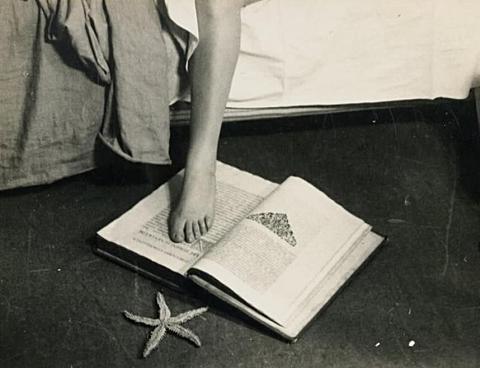

1928

Man Ray

b. August 27, 1890

_______________________

The Art of Empathy [pdf]

Celebrating Literature in Translation

National Endowment for the Arts

Our goal for this book was simple: to illuminate for the general reader the art and importance of translation through a variety of points of view. Each essay tells a different story; each story adds to our understanding of this little-known art form. And in case you read through these passionate essays and find yourself inspired to make the next book you read a work in translation, we've asked each of our contributors to recommend three books. These are not necessarily the quintessential, canonical, must-read translations from an academic point of view, but rather three books that they simply loved and wished to share.

-

Amy Stolls

via Center for the Art of Translation

_______________________

'My lifetime dream is to be sitting at the bottom of a well'

Haruki Murakami talked writing, heroes, domestic life, dreams and how his life informs his novels at a Guardian book club at the Edinburgh international book festival – and he answered some of your questions

guardian

_______________________

Me, She

Man Ray

1934

_______________________

Phantamasgoric Capitalism: Benjamin’s Arcades Today

Jim Fearnley.

3:am

“A landscape haunts

Intense as opium”

-

Stéphane Mallarmé

There seems to be only one way to approach a text like The Arcades Project, namely in the spirit in which it was written – discursively, digressively, impressionistically. Therefore, the following does not follow a conventional scheme, either of chronology or in the form of an imitation of the structure of the text, given its own organic flavour.

Why discuss The Arcades Project now? The book, for all its chaos and eccentricity, is an attempt to provide a record of capitalist development in a particular place and time, namely 19th-century Paris. As we know, capitalism hasn’t gone away, and neither have the particularities discussed by Benjamin – the ‘phantamasgoric’ nature of a society created by an economy in which exchange and representation suppress use and experience, the power of commodity fetishism and its extension into the field of sexual relations, the bourgeois domination of inner-city space, and the voluntary nomadism of the middle-class flaneur.

There is a further reason why this is an opportune moment to critically examine the relationship between cultural studies and radical theory, and Benjamin is perhaps best placed to provide an example for discussion, given he was as much enamoured of the former as committed to the latter.

...(more)

_______________________

Copyright and the Tragedy of the Common

Tracy Reilly

Abstract

... I will describe my related tragedy of the “common” theory in the context of copyright law doctrine, in which I will illustrate a broader moral and philosophical tragedy related to the manner in which contemporary copyright scholars are discouraging and outright debasing traditional creative works of authorship while inspiring an alternate doctrinal approach which they define by using subtle and elusive terms such as “collective ownership” and “collaborative cultural production.” In this article, which examines copyright theory in a unique historical, literary, and philosophical context and contributes to the often contentious contemporary debate on the nature of creativity, I will show that viewing the process of copyright authorship and ownership of its resultant works with a collectivist or collaborative lens—or with what Søren Kierkegaard labels a “crowd mentality”—instead of continuing to reward individual authors for their creative works will invariably lead to the demoralization of the spirit of man and a culture in which common and regurgitated works will be produced rather than works of genius and individual originality, thus resulting in a decline of progress in contravention with Article I of the U.S. Constitution.

...(more)

Savage capitalism is back – and it will not tame itself

David Graeber

Ponzi Scheme Capitalism: An Interview with David Harvey _______________________

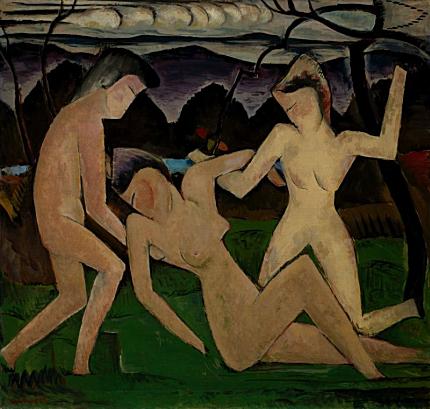

Departure of Summer

Man Ray

1914

_______________________

The Second Body and the Multiple Outside

Alina Popa

Patho-logical knowledge

A body doesn’t coincide with itself (Massumi)

In a visual field a thing which doesn’t coincide with itself is a blurry thing whose position cannot but be approximated. This would correspond to an epistemology based on uncertainty – unlike the Western knowledge relying on truth and certainty, on identity and fixity of laws underpinning a logical system or a scientific theory. That is perhaps why blurry images bring about fear of unknown and are associated with terrorism, forensics, criminology or disabled sight thus poor logic.

A thing which doesn’t coincide with itself is a frightful micro-cosmology. Healthy thought ceaselessly introduces a succession of time or a minimum causality in order to distance the indistinguishably different points and soften up the reasoning process. Usually, in classical philosophy time has privilege over space, so that space is created in time, one cannot think the emergence of form and space without the ticking causality of time, emergence without anteriority. Blurred thinking or better said patho-logical thinking (patho-logical is collapsing the logic of sense, of pathos and an impaired, diseased logic, a counterintuitive, stubborn and humiliating logic) can only grasp the necessity of uncertainty, of a blunt identity, of emergence without anteriority.

A diseased world from which time has been severed is a suffocating breathless world of absolute instance, of infinitesimal nowness where emergence equals eternity and events don’t happen, they just are, frozen in a snapshot of overlapping actualized potentials. It is a deaf vibrancy, a non-acoustic oscillation of matter-strings, a traumatic sensorium, an inhuman regime. It is not anymore a vibrant matter(1) which folded onto a plane produces an unstable map of forces and trajectories, but a stabile instability, a map of the untraceable, the unrepresentable only a sadistic, suicidal thought could try to think. A productive paralysis similar with the “cruel thought” of Antonin Artaud. This collapse of movement and stability, this grounding of the ungroundable would be a world at the limit of thought, without process, a world of contradiction and paradox, of despair and catastrophic reason.

...(more)

.....................................................

Reading this essay I imagined Théophile Gautier, Charles Baudelaire, and Emil Cioran merged in the figure of a lamentation, an almost Rilkean Angel of Annihilation. To imagine a time traveler who can see the static frames of history in stasis, frozen forever in an obscene gesture of pure clarity, the stubborn movements of reality measured not in time but in eternity, the blipscreen of a final cinematic frame that captures the moment between time and eternity just before the screen goes blank forever: a form that is both formless and frozen. Even the spirit of decay is stifled here, in a world where everything has already happened, where time stand's still and the nothingness that is and the nothing that is not cross distinct light frames into each others gaze. She talks of how in every moment we are about "…to take an intimate shape, to consolidate in a known form, to create the world around us as we know it. There is an immense "fear of being undelimited", of losing periphery, of falling through the ground. It is the fright of ungroundedness, the horror of being on the brink of the solid."

- Craig Hickman, Alina Popa - Cruel Thoughts

photo - mw

_______________________

Autumn Ill

Guillaume Apollinaire

b. August 25, 1880

translated by A. S. Kline

(Alcools: Automne malade)

Autumn ill and adored

You die when the hurricane blows in the roseries

When it has snowed

In the orchard trees

Poor autumn

Dead in whiteness and riches

Of snow and ripe fruits

Deep in the sky

The sparrow hawks cry

Over the sprites with green hair the dwarfs

Who’ve never been loved

In the far tree-lines

the stags are groaning

And how I love O season how I love your rumbling

The falling fruits that no one gathers

The wind the forest that are tumbling

All their tears in autumn leaf by leaf

The leaves

You press

A crowd

That flows

The life

That goes

Selected PoemsGuillaume Apollinaire

translated by A. S. Kline

_______________________

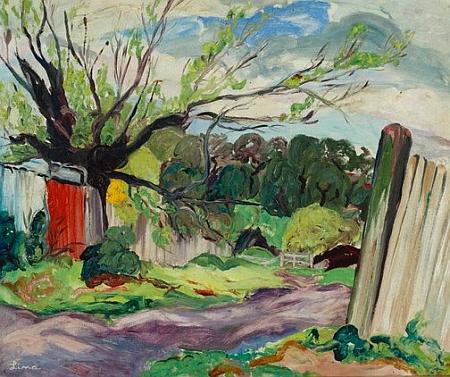

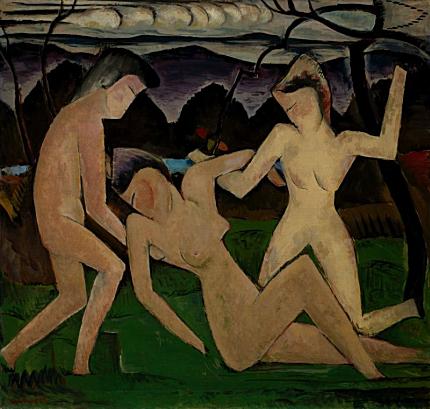

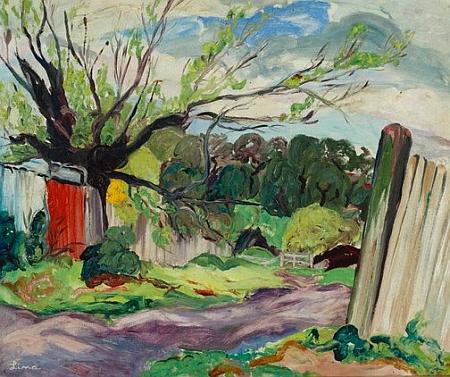

Face of Liru

Lina Bryans

b. August 26, 1909

_______________________

Penury by Myung Mi Kim

reviewed by John Herbert Cunningham

Galatea Resurects

Kim, in a Youtube video, refers to Penury as a “mourning book”. She indicates that the period of creation was from February 2003 to February 2006 which was the period during which “America has been in Iraq.” She describes the book as proceeding

by accretion, by adumbration, moving around different elements, there is a lot of transcription which are me literally transcribing whatever it happen to be, whether it’s spoken, whether it’s document, whether it’s...something that is archival material...I’m also trying to pose the question “What is the necessary work of mourning both as bodies in social space trying to, in some sense, negotiate...the violence of militarism on human bodies, the notion of war and ecological degradation, my continuing concern about linguistic oppression or a certain attempt to address the...problematic of the ideology of monolingualism.

In an interview conducted by Yedda Morrison in December 1997 titled ‘Generosity as Method: An Interview with Myung Mi Kim’, Kim discusses poetry as liberation and the authentication of a writer’s experiences:

I think there is always some kind of invisible, constant, millisecond-by-millisecond negotiation between the form and its divestment, between the poem and the world, that you’re engaging every time you decide to write anything. However, any poem having any kind of cultural translation in the Twenty-first century – frankly, it isn’t going to happen...

It’s so problematic for writers in our historical moment. Again, I think that I would answer that concern by saying that there’s some awareness on my part, different from even five years ago, that we need two actions simultaneously. The first task is undertaking the kind of devotion and conviction towards authenticating the work you must do, the work we each must undertake, and that forms the basis for a much larger vision for a mobilizing potential for poetry...The second thing is to work out as many different models of where poetry can exist, where poetry can be inserted, can be read, experienced, performed; what are the various different ways that we can make poetry have contexts...Poetry is simply how you participate in language, and we all do that. ...(more)

via flowerville_______________________

The End of the Road

Lina Bryans

_______________________

The Capitalism of Affects

Cinzia Arruzza

public seminar

The social management of affects is not an invention of capitalism and does not, as such, characterize capitalism in a specific way. In other words, when we address the problem of affects under capitalism, we should be very careful to avoid the risk of thinking that the problem lies in the capitalist intrusion into our hearts, in an opposition between, for example, the authenticity and naturalness of our private affects and their forced and normative display or regulation dictated by capitalist social relations. On the contrary, we may even think that a robust notion of the privacy of affects as characterizing what it means to be a unique individual arises with capitalism and modernity.

If this is true, then, we need some more analytical work in order to understand what exactly is specific to the managed heart under capitalism. For this purpose, I would like to suggest at least three factors that concur to a specific capitalist form of affects management.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

The Right Stuff

Brenda Wineapple reviews The Allure of the Archives by Arlette Farge

threepenny review

I have pitched into dusty boxes stuffed with faded green stationery and, when the day ended, I’ve stayed in musty motels overlooking busy highways, waiting anxiously for morning, when I could walk back over to the archives in the summer heat, hoping to discover something big and important and worth my sleepless while. I have wondered if I should untie the ribbon carefully knotted a century ago and read what was not meant for me. And then I have untied that ribbon and unfolded delicate sheets of writing paper. I have deciphered the script in leather-bound diaries whose covers crackle with age, and I have looked at old photographs, wondering who or what stared back.

I considered these research trips peculiar, sometimes productive, and, after I totted up my travel receipts, always expensive. But the reason I undertook them and the satisfactions they afforded seemed a private affair little understood except by weirdos like myself who rather enjoy this odd solitude and with whom I share a peculiar if not grandiose fantasy: that we’re on a mission. We root around in old stuff because we’re rescuing some person, some fact, or some event from the past and bringing them, or it, back to life.

As I say, I thought most of this rather eccentric until I read Arlette Farge’s unique, lyrical paean to historical research, The Allure of the Archives, about the historian’s never-sated passion for archival research, no matter how sepulchral the archive or arcane (and potentially fruitless) the quest. Originally published as Le Goût de l’Archive in France in 1989 and now superbly translated into English, this is the only book I know that in one hundred or so eloquent pages captures the essence of what it means to travel to an archive, to lose oneself in it, and even to argue silently with fellow researchers about how much noise they make or whether they, or you, have the best seat in the chilly room. (Library archives typically keep the temperature down to preserve documents. Even in summer, I bring a sweater.)

...(more)

_______________________

A Man with a Movie Camera

Dziga Vertov

(1929)

soundtrack by Alloy Orchestra

Alloy Orchestra - The New Sound of Silent Films

_______________________

Four poems

Leevi Lehto

jacket

The Chasm Is Here, The Chasm Is Nowhere

call a screw in for interrogation, and you will see

thru the meat grinder and couldn’t think of putting anyone else thru such

keeps in the wall

isn’t gaining any goodwill points here where baseball bats and

the purpose of its threads will ask you to

confess you are a rabbit

the shame of you: you will see at once

but be refused to take up a crusade to get

torture out of Norway. Take the screw back and ask

her to read once about sensory deprivation being the most effective form of

weather, and it will need stars. Keep the execution squad hidden

to survive this. He was going

behind a curtain disguised as the starry sky

not only to put up with this

somewhere. A wall collapses. That alone would be reason enough to

dream the Escape Dream, the toss all you

execute to screw reason, which leads the entire complex

promising that Dershowitz would advocate

the rebellion. The screw falls silent. And perhaps you, too,

which is why we’re not going to the Billy Bob Thornton concert at the El Rey

having learned something this very morning: you cannot give orders

to constant attention, and besides,

before speech gives permission

no one (else) can come

...(more) Leevi Lehto at EPC

_______________________

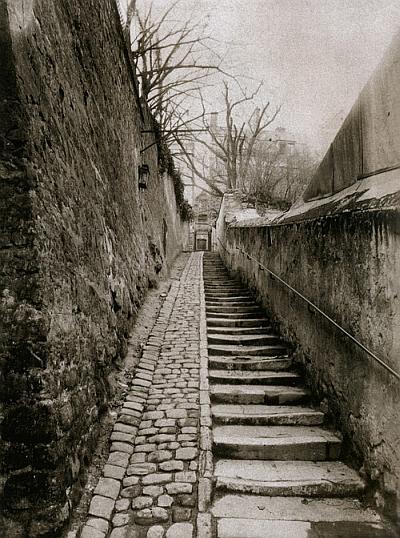

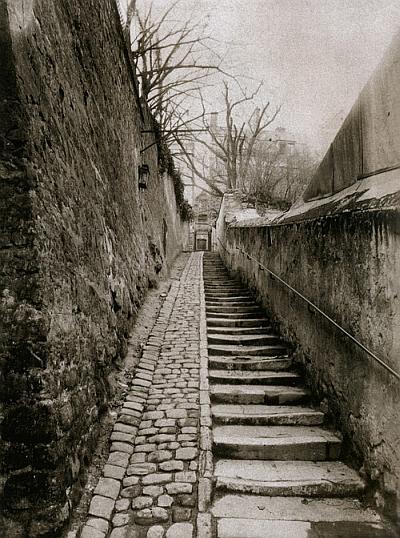

Passy, passage des Eaux

1901

Eugène Atget

_______________________

My Finnish Poetries

Leevi Lehto

(....)

Let me say in passing that by giving you these examples, I am not implying that there would be some fundamental difference between thinking in these two languages. The idea of language conditioning and determining thought is of course prevalent in what is known as postmodern theory; likewise, you sometimes hear that theory criticized for claiming that, somehow, “everything is language”. Though I’ve been much influenced by this kind of thinking, in both my intellectual and poetic development, I now tend to see the things the other way round. To say that everything is language would imply, fundamentally, that the reality is transparent, explainable, if only with difficulty (and those believing in this, I think, ultimately do think that everything is language.) For me, the centrality of language comes, on the contrary, from the fact that it is not everything, does not come to us naturally, is something to be learned, and for this reason always insufficient and unfinished, never capable of explaining everything. (and I’m tempted to make the equation: what, in philosophy, is known as the real = that which stays outside the language, resisting its power to explain). The job of poetry is sometimes said to be to make reality seem strange (or new.). To me the more urgent job is to reveal the strangeness of language. And here, there is no fundamental difference between the strangeness of my own language, and that of those learned later, and thus less in my command. This is one of the reasons I am more and more interested in writing in English, of which more later.

...(more)

_______________________

FLEKS

Scandinavian Journal of Intercultural Theory and practice

Vol 1 (2014) Tolerance

Guest Editors Introduction

Karina Hestad Skeie, Line Alice Ytrehus The first two issues of FLEKS explore the notion of tolerance in theory and praxis. Tolerance is a rather appropriate point of departure for a journal on intercultural communication and interaction. In the intercultural context, mutual tolerance and/or respect are seen as basic requirements whether the objective is the reciprocal exchange of ideas (in a dialogue), or effective communication for informational, political or commercial purposes. In addition, politicians and theorists involved in debates about multi-ethnic societies frequently describe tolerance as a basic human virtue that is required for peaceful coexistence.

Tolerance is a complex and multifaceted concept, and accordingly is not easy to grasp or study in a precise, coherent and non-reductive way. Usually the exercise of tolerance involves the making of a moral judgment, thus requiring knowledge, whether real or imagined, as well as reasoning and emotions. Tolerance may encompass anything from an acceptance and acknowledgement of something or somebody to an act of endurance that is undertaken with varying degrees of disapproval. In everyday life, the need for tolerance is most strongly felt when one is confronted by its opposite: hate speech, violence, contempt and exclusion. In everyday speech, we also hear calls for "zero tolerance" in certain multicultural settings. Sometimes these calls represent a firm adherence to basic values. Sometimes they represent a desire to defend what are considered to be vital interests. At other times, they are reactions based on fear, mistrust and misunderstandings. How can we determine what is what?

_______________________

photo - mw

The Night Has Gone

(1947)

Jack Butler Yeats

b. August 29, 1871

_______________________

The Poetics of Spaces: Inyo National Forest & Outward

Janice Lee

entropy

(....)

Here is the thing. In a place like this, your perspective changes, widens. Remember single frames of your life back there and realize what it means out here. Recall gestures of comfort, words spoken, feelings. Here: presence. Here: it all.

Here is the thing. Happiness is difficult. Not just to obtain it, but to be consumed by it. For seconds, moments, hours at a time. It is a privileged part of life to be able to be joyous, even for just a few seconds, to be in love, to be content, to at least once breathe a sigh of relief. But it is also necessary to mourn, to lament, to be disappointed, to be angry, to regret.

It is crucial that we fail. And it is crucial that we succeed.

When you see the half-empty lake, imagine what it would look, you replace the word would with should, replace should with would again, see snapshots of lives that intertwine and scenes that seem to belong on postcards, exist in nature, away from that other stuff. You think about the weather. You are ambushed by a group of deer, fleeting, hopping. You think about life as privilege. As burden. You think about the scale of things. Large. Small. Full of holes. Weather-worn. A breeze that rises up behind your back and cools the sweat on your back.

...(more)

_______________________

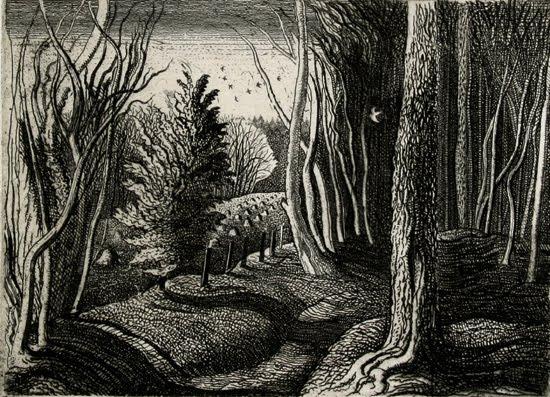

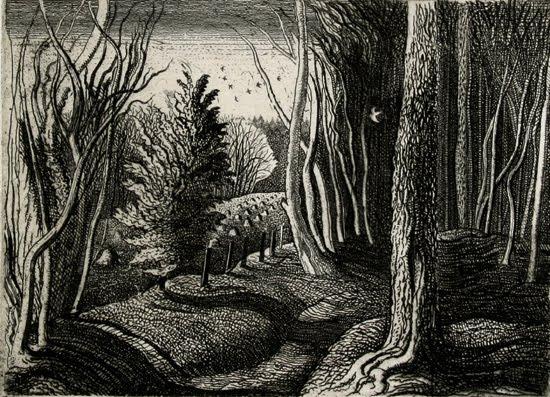

Wood Interior

1928

Graham Sutherland

b. August 24, 1903

_______________________

It is here that it translates, "this madness," that it comes back to us as the impossible need. Translating especially the untranslatable: when the text does not only carry an autonomous meaning which alone would be important, but when the sound, the image, the voice (phonological) and especially the principality of rhythm are predominant compared to the meaning or making good sense, so that the meaning is always in action, in formation, or "the nascent state" cannot be dissociated by what by itself is not stored in the semantics. And this, this is the poem. Certainly, no translator, no translation will not pass it, intact, from one language to another, and will not permit it to be read or heard as if it were transparent. And I would add: happily. The poem in its original language, is always already different from the language, whether it restores or establishes it; and it is this difference, the otherness, where the translator grabbed it or where it is grabbed, modifying in its turn its own language, making it dangerously moving, removing its identity and transparency to the "common sense," as Valéry says.

Opacity? Opacity of sense? Opacity as meaning? Neither one nor the other. The opacity has multiple layers of language through which they walk and form what eventually - in infinity - mean: strata that simultaneously flicker or darken by the significance, moments by themselves neglected in common parlance, transforming then just to make comprehensible another another form of agreement, the unlimited agreement that breaks the ordinary trade. Hence, perhaps, the poetic loneliness (has anyone been there to understand it? It is infinitely enough to hear it?); hence also the poetic fraternity ("sovereign conversation"), since which, by the poem, we are called to the urgency of interminable ration where the "I" has always faded away to the other, and where speech, writing, and sign collapse without constantly pursuing anticipation that dissolves them and mysteriously remains there by a frightening dispersion.

-

Maurice Blanchot, The Rising Speech, Translated by Wanyoung Kim

_______________________

The Novelist

Jack Butler Yeats

_______________________

Alice Oswald - Poems in the Guardian

Time Poem

Alice Oswald

now the sound of the trees is

worldwide

and I'm still here

staring when I should be bathing

children.

it's late, the bike's asleep on its feet.

the fields hang to the sun by

slackened lines...

when the grass breathes, things fall.

I saw

the luminous underneath of a moth.

and a blackbird

mouth to the glow of the hour in

hieroglyphics.

who left the light on the step?

pause

what is the pace of a glance?

the man at the wheel signs his speed

on the ringroad

right here in my reach, time is as

thick as stone

and as thin as a flying strand

it's night and somebody's

pushing his mower home

to the moon

...(more)

.....................................................

Alice Oswald at Poetry International and the Poetry Foundation

European Voices: A Reading and Conversation with British Poet Alice Oswald

youtube

Alice Oswald's nature columns in the New Statesman

The Struggle Against Silence — Interview with Alice Oswald

_______________________

Interview With Alice Oswald

Max Porter

white review

(....)

Ashbery always sounds as if he’s thinking, even when you can’t quite get at the thoughts. Jorie Graham uses those expanding and compressing lines, which defeat the eyes and jumble the body’s rhythms so that your mind sort of breaks open. Dickinson actually exposes the pauses in the brain. They all seem to articulate indecision, as if the poem was writing itself in an unfinished moment. I find that quite invigorating.

Poetry has this close relationship with tradition, so it’s interesting that the English language has two poetries, one of which (the American) is determined to escape its tradition. It’s like an open window in the work-room. Whenever I sit down to write, I have to think through certain questions about form – am I or am I not going to write a sonnet? If I don’t count syllables how do I communicate a tune? If I rhyme, whose voice am I putting on? And sometimes the whiff of America through the window gives me permission to ignore those questions. And then sometimes that permission can become a tyranny. Ginsberg and Frank O’Hara for example are quite pressurising and impatient with their invitations to freedom.

(....)

It’s always been my feeling that one mind isn’t enough for a poem. I like to talk about ideas with people. And I really do regard my poems as not my own. That’s not just a false modesty. They come from working with other people. I’ve worked with gardeners. I’ve worked with a trumpeter. He taught me a lot about the gaps in poems and what they are doing. I like that tension between silence and music, or words. And the person I most collaborate with is a typographer who lives near here, called Kevin Mount. He’s a really interesting person, a hidden genius. He’s brilliant at understanding how a poem wants to be set on a page.

I feel a poem needs not to assume it will be read. It has to have the energy to create its own necessity. Poems shouldn’t operate within an expectation of poems being passed around. So I get very stuck on the question: why should a poem begin? Why should anything ever start speaking when silence is always more appropriate? This makes me suspicious of the impulse to write themed collections, because I think they dishonestly do away with the struggle against silence. ...(more)

_______________________

The Outsider

Jack Butler Yeats

_______________________

Poetic Thought for the Day (8/24/2014): The Quest for Meaning

Craig Hickman

—Say it, no ideas but in things—

nothing but the blank faces of the houses

and cylindrical trees

bent, forked by preconception and accident—

split, furrowed, creased, mottled, stained—

secret—into the body of the light!

– William Carlos Williams, Paterson

What is an idea? What is a thing? What is poetry that ideas and things can suddenly come together? ...

(....)

For the new breed of poets following the Speculative Realists there is a need to break out of Kant’s circle and the Sublime and go back out into the real, or what Meillassoux would term the “Great Outdoors” of Being. Now poets following such notions so far realize that what this entails is a reframing of the way ideas and things interact. No longer bound to Kant’s schemas and categories of thought, we are now exploring through the senses again. Instead of representations in the mind, we are turned toward the anti-representational worlds of the senses themselves. The trick is not to confuse the two. Idealism as far back as Parmenides is based on just such a notion of Ideas = Things; or Ideas and Being are one, so that it is through Ideas that we are in touch with the Real. This is the Platonic Cave all over again, the idea that this world is illusion, vanity, a surfeit of unreality. But is it? Why have we been tied to such anti-realistic notions of rocks, trees, mountains, rivers, etc. for two thousand years? Obviously I simplify to the point of a cartoon. I can’t in such a short note begin to unload the whole conceptual history of Idealism or Materialism and their antecedents in one post. Madness, that.

My greatest point is that confessional poetry was still keyed into representational or expressive thinking; and, we seem to be moving into a new time of speculative and anti-representational modes which is about how we frame ideas or things, people or places. It’s almost a cross between the older modes of the metaphysical poets merging with the Renaissance core of naturalism… as if turning inside out. As if we’d pushed the realist and anti-realist modes of the last century based on understanding language or the “Linguistic Turn” and have like the Chinese sense of I Ching switched over from the masculine to feminine modes of thinking and feeling. More concretely William Carlos Williams a century ago said: “No ideas but in things.” Now we would say “No things but in ideas.” A grand reversal, but one that takes into account that the world is not “for us” but that we are all on equal footing. That things have their own ideas and can now express them, and it is up to us to absorb or receive them from the objects rather than imposing them as in Williams. ...(more)

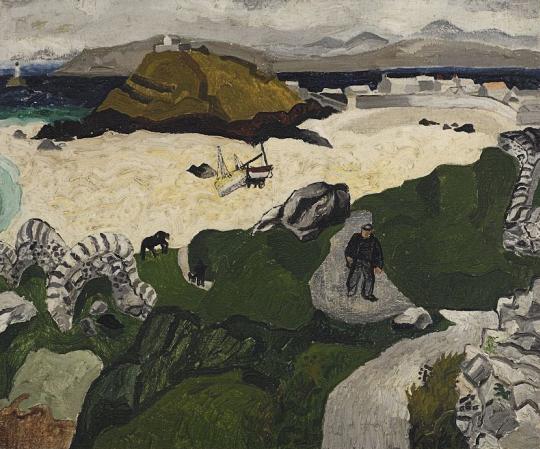

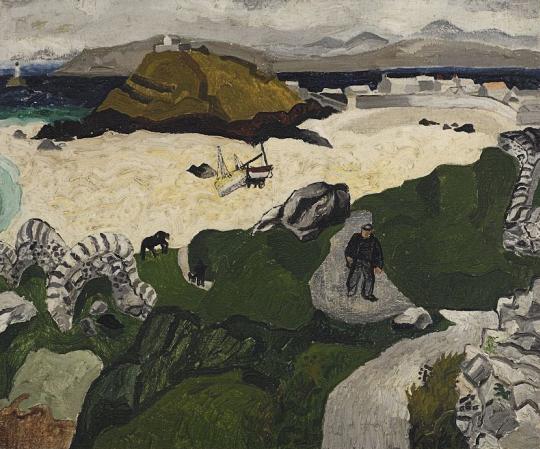

Porthmeor Beach

1928

Christopher Wood

d. August 21, 1930

_______________________

from Goat Songs

Chuya Nakahara

translated by Christian Nagle

asymptote

Exhaustion

For all men, there comes a time of languishing.

—Proverb

First, one must have a thirst.

—Catherine de Medicis

I didn't awaken with a sense of purpose anymore.

I awoke and a sad, everyday scene

I'd bitterly dreamed of ...

(I could neither settle in

nor escape that place)

Then evening came, and I thought

this world is like an ocean.

I imagined a watery expanse at dusk,

where a haggard boatman rows

with unsteady hands.

Looking to see if there are any fish or not,

he passes by staring at the surface. ...(more)

.....................................................

Christian Nagle on Chuya Nakahara

asymptote

Chuya Nakahara was a Japanese early modernist of conflicting, even paradoxical, impulses: almost apolitical but fiercely iconoclastic; a progressive formalist; occasional swain of his own urban pastorals; an agnostic singer of prelapsarian hymns. He rejected the language of his age, of any age, strove to articulate what he called "the world before the word," wherein the primeval saturates the sensorial present. He was dismissive of institutions, especially literary schools and scholasticism, because, as he claimed at the start of his career, he was beyond their prescriptions. Yet, for all his bohemian airs, Chuya (like Dante, he is always affectionately referred to by his first name) was a proudly successful auto-didact, and his mastery of waka (formal, 7/5-syllabic verse) combined with his eventual competency in French to provide the touchstones for his hybrid evolution. He wrote half under the shadow of his Meiji-era predecessors, while straining towards those Symbolists he admired and translated—Rimbaud, Verlaine, Baudelaire, Mallarmé—and, with an assurance unrivaled by any of his peers, the Surrealists. His English was inadequate to an academic understanding of English-language poetry and, like many other Japanese modernists, he was privy only to a random body of English poems in translation, scattered through the journals of his time.

One should not, therefore, consider Chuya in the context of Western poetry. He wrote not within its traditions, only partly out of them. Yet he was, like many other 20th-21st century Japanese artists, a master of assimilation and transmogrification. Fundamental linguistic and prosodic differences between Japanese and English mean that while incorporating whatever Western formal elements he could, Chuya was obliged to make Japanese versions of others. In his sonnets, for example, since Japanese is non-accentual, he refigures iambic pentameter as waka-form syllablic lines. Although not a pioneer in this regard, Chuya is admired today as one of the most scrupulous pre-war Japanese writers of poems informed by European models. He acquired new thematic and tonal license from his obsession with collections like Le Bateau Ivre, but the element of Symbolist poetry that held the greatest value for him was refrain. Through it he found liberation from the claustrophobic dimensions of tanka and haiku, even while the echoes of their decorum kept his poems grounded in the culture from which they derive.

...(more)

_______________________

A Fishing Boat in Dieppe Harbour

Christopher Wood

1929

_______________________

The Return To Silence — An Essay On Friedrich Hölderlin

Paul Stubbs

The end of speech could arrive on the day when everybody feels as theologically posthumous as Friedrich Hölderlin did, or when we, the only defensible illusions of his lost syntactically fatherland, come to feel as truncated by his voice as he did by God’s. He, a heresiarch of grammar, a stylistic and apophatic revolutionary—yet what greater advances on the holy lands might he have made if he had never once opened his mouth? If, in the middle of a poem, he had celebrated only the vocal impoverishment of man, rather than what, by the time of the late ‘Hymns’, had begun to impinge on humankind. In ‘Patmos’ we read: ‘Near is / And difficult to grasp, the God’, which is the moment when the retractable visor of God begins to draw across the visage, at the same time, of both animals and humans alike. But then Hölderlin, as if aggravated by the knowledge of all things divine, dreamt of nothing but what in the New Testament cannot be said. Establishing what is contrary to the fanatic and the zealot, the poet by-passed the reasonable believer, to pronounce the Christian a mute thinker, that is compared to the grammatically forming image of the real Christ inside of his head. Thus the purely ‘religious’ thinker, owner of a second-order mind, remains subsequently more remote from what the prophetic mind sees, i.e., the future of holiness. So where does the grammatician leave off and the prophet begin? Hölderlin, a temporal image of himself, one unleafed and, for the duration of polytheism, never to be overgrown with the vines of ‘One’, asked only that we accept silence as the one meaningful syllable in the universe. Striving as he did to conceive of the ‘rhythms’ of each different religion, but without a depiction of each ‘different’ church; therefore Hölderlin became infatuated with the arrival of godheads in the same place, and with a boundlessness brought home.

...(more)

via of Resonance

_______________________

the cause of strangeness in ourselves

from The Witness by Juan José Saer

flowerville

(....)

It is hard for any of us to locate our past with any certainty in a precise moment in time and space. Coming as I do from nothingness, I find the reality of my past even more problematic. No human life is longer than those last seconds of lucidity that precede death.

p88

That absence of meaning invades us uninvited, as it infects the things themselves with an air of unreality which gradually diminishes with the heavy somnolence of the passing days, leaving us with only an aftertaste, a vague memory or a suggestion of doubt which casts a slight shadow over our commerce with the world. The dazzling flash of light leaves us blinking and, to escape delirium, we prefer to absolve the world of blame and find the cause of strangeness in ourselves. It is, of course, infinitely preferable to believe that it is oneself and not the world that falters.

p135

...(more)

_______________________

Nakahara Chuya

1907 - 1937 A Selection of Poems by Nakahara Chuya

translated by Ry Beville

_______________________

Nakahara Chuya: Four Poems Newly Englished

Translations from Japanese by Jerome Rothenberg & Yasuhiro Yotsumoto

Autumn Poem

(....)

3

The grass was absolutely still,

and over it a butterfly was flying.

He took it all in from the veranda,

stood there dressed in his yukata.

And I, you know, would watch him

from this angle. Staring after it,

that yellow butterfly. I can remember now

the whistles of the tofu vendors

back and forth, the telephone pole

clear against the evening sky.

Then he turned back to me and said “I ...

yesterday, I flipped a stone over that weighed

maybe a hundred pounds.” And so I asked

“how come? and where was that?”

Then you know what? He kept on staring at me,

straight into my eyes, like he was getting mad,

or something … That’s when I got scared.

How strange we are before we die …

...(more)

.....................................................

A Suite Of Translations From Nakahara Chuya [pdf]

With

A Concluding Poem In Tribute

Translations from Japanese by Jerome Rothenberg & Yasuhiro Yotsumoto

big bridge _______________________

Le Phare

Christopher Wood

1930

Alfred Kubin

d. August 20, 1959

_______________________

Quiz: Which Siglum From Finnegans Wake Are You?

Eric Jett

full stoop

So?

Who do you no tonigh, lazy and gentleman?

The echo is where in the back of the wodes; callhim forth!

(Shaun Mac Irewick, briefdragger, for the concern of Messrs Jhon Jhamieson and Song, rated one hundrick and thin per storehundred on this nightly quisquiquock of the twelve apostrophes, set by Jockit Mic Ereweak. He misunderstruck and aim for am ollo of number three of them and left his free natural ripostes to four of them in their own fine artful disorder.)

...(more)

_______________________

Peaches

1884

S. Fisher Corlies

(1830-1888)

George Eastman House

Photography Collections Online

_______________________

“Howl” in Italian

Evan Fleischer

Electric Literature

(....)

... (Fernanda) Pivano’s correspondence with Allen Ginsberg in relation to the poem’s translation is instructive. In their letters, Ginsburg answers Pivano’s questions about “Kaddish” and other poems, describing his mother’s “paranoiac complains … used as surreal fragments”; defining cultural references (“Woody Woodpecker is an allied cartoon character, hero of a series of cartoon disasters in technicolor”); explaining how “the LSD poem” was “written at Stanford’s Mental Health Experimental Lab and I’d asked the doctor to bring me various things to look at while under state of drug — Gertrude Stein on phonograph, some Wagner records.”

This is all part of the inquiry that French poet and translator Yves Bonnefoy identified as essential to capturing the spirit or essence of a work in translation: You don’t want your car to take you to the supermarket and back; you want it to sail from the woods to a farm to a city to a beach clogged with kites and back again. So it is with language.

...(more)

via The Page

_______________________

Basket of berries

S. Fisher Corlies

ca. 1879-1885

_______________________

The conscience of the world': Lars Iyer on Wittgenstein Jr

(....)

I think Bernhard has become too familiar as the turncoat of Austria, as the scourge of fascism and Catholicism, as the enemy of the middle class, and so on. He’s become a little too easy to accommodate as a pricker of pomposity and an exposer of hypocrisy. Bernhard is more than a satirist. Satire relies on certainties and norms, on the sureness of values, for its effect. So thinking of Bernhard merely as a satirist allows us to contain his work, to make sense of his wildness. It allows us to suppose that he is one of us, on our side...

There is something devilish in Bernhard. ‘I will not serve’: that’s what his novels say. This, for me, is what is marked about his comedy. Black comedy, goes the definition, refuses to treat tragic materials tragically. It makes us laugh at tragic things. But I would go further, and say that black comedy refuses to treat comic materials solely comically, or satirical materials solely satirically. Black comedy flourishes in a time when certainty and norms are in question; when there is a lack of confidence about values. It’s wild. It’s not a safety valve. It goes too far. It is indiscriminate. One minute we might nod our heads at its targets, the next minute we might find ourselves the butt of the joke. Above all, black comedy permits no comic catharsis – no return to what is good and valuable about the world...

Did Bernhard influence me? Roger Blin: 'I know Antonin Artaud only through his trajectory in me which is endless'. I would say the same of Bernhard.

...(more)

Barges

1919

David Bomberg

d. August 19, 1957

_______________________

In the Noon of Contradictions

Andrée Chedid

excerpted from Terre et poésie, 1956

Translated from the French by Marci Vogel, 2013

scroll down

1

There is no wave more fatal than the sea; no tree more illustrious than the forest.

2

Neither silt nor star; we take after one & the other, both at once.

Opposites overrun our paths; our way is made by the slow pace of choice.

(....)

4

Breath short, we walk by stopping places; the gaze impatient, we know not how to stay.

Move forward, recover joy, brave obstacles, perhaps defeat, then begin afresh: such present our possibilities.

Let us love the rays of a threatened sun; precious for us is the pond that retains its share of sky.

(....)

13

May we shield those who failed us the whole mystery of their face. Injured and at fault, we are thereby judges, donning the bitter mask.

The weaknesses of others, when they scratch our tender skins, press us to deny all past accord. Turned toward possession, we are without vision and without pardon.

14

Sometimes absent — the other side of notice — , we leave as guaranteed bonds our ancestral features, reassuring as habits.

But the journey is not measured by distances; and the look back barters neither uncultivated regions nor impassioned lands.

...(more)

.....................................................

Andrée Chedid and the contradictions of translation

Marci Vogel

(....)

10

In his 1996 address, “Translation as Challenge and Source of Happiness,” Ricoeur linked the complexities of translation to the title of Antoine Berman’s 1984 work, L’Épreuve de l’étranger: “These difficulties are accurately summarized in the term ‘test’ [épreuve], in the double sense of ‘ordeal’ [peine endurée] and ‘probation’: testing period, as we say, of a plan, of a desire or perhaps even of an urge, the urge to translate.”

And so Christine begins to laugh her happiness in section 1, but she does not drop the challenge of happiness’ charge before arriving at its source. The poem must still be written, the effort endured. So too in translation, in which not only the translator is tested, but also the translated.

Chedid claimed épreuve as a “touchstone” word and translated it not as test but as proof, something more elastic, contingent, and enduring. She explains her choice of the word as the title of her 1983 collection Épreuves du vivant: “The resources of the word ‘proofs’ are infinite. How can we not be reminded of photography, of images being inverted? How can we fail to delve into this word so rich in exhortations, risks, pathways to be explored? Poetry reveals itself in our destinies by repeatedly making appeals to life; poetry is all at once the spur, the hope, and the proof of the Living.”

11

As a member of the Living, the étrangère may share the desires, hopes, and tests of the native-born, but she is not to be entirely trusted, nor are any kin under the stranger’s purview. As Jane Hirshfield points out: “Translated works are Trojan horses, carriers of secret invasion. They open the imagination to new images and beliefs, new modes of thought, new sounds. Mistrust of translation is part of the instinctive immune reaction by which every community attempts to preserve its particular heritage and flavor: to control language is to control thought.”

If one were in Rome, Hirshfield notes, she might very well be thus accused: “Traduttore, traditore (translator, traitor).”

For the potential betrayal that resides in translation, Ricoeur proposes linguistic hospitality as a remedy: “I am inclined to favor entry through the foreign door, that is for sure … [W]ithout the test of the foreign, would we be sensitive to the strangeness of our own language? … [W]ithout that test, would we not be in danger of shutting ourselves away in the sourness of a monologue, alone with our books?”

The mathematical symbol that resembles an 11 is used to indicate both parallel relationship and incomparability. It is by way of this symbol that a host might become both parallel to and incomparable with a traitor:

[host/traitor]

And it is in this very way of seeing oddness doubled that makes possible both the offering of an invitation and its acceptance: “Linguistic hospitality, therefore, is the act of inhabiting the word of the Other paralleled by the act of receiving the word of the Other into one’s own home, one’s own dwelling.”

...(more)

.....................................................

Andrée Chedid

1920 - 2011

Andrée Chedid: Selected Poems, Short Stories, and Essays

google books _______________________

First Image of Revolt

Andrée Chedid

Translated from the French by Judy Cochran

The woman without memories

Has left for the high lands

The ancestors' withered field

In the mornings of wrath

She runs dressed in black

Among the scattered flocks

Nothing is there

But a star village

Resting heavily on a hill.

_______________________

vaporetto

1960

Gianni Berengo Gardin

_______________________

Signs and Machines – Maurizio Lazzarato

reviewed by Patrick Lyons

full stop

Tracking down texts that gracefully bridge theory and praxis can be a thankless quest. In most cases we’re caught on one side or the other: tackling either sprawling philosophical abstractions or over-specific studies trapped in a singular historical moment. One never touches ground while the other never sees the sky. Yet every so often we stumble upon a remarkable book which somehow manages to toe the line between these two camps, if not balancing their influences, at least drawing clear lines of contact. Such a book is not necessarily one which flawlessly and meticulously transposes the philosophical onto the everyday, but rather one which points out their preexisting intimacies, provoking speculation and connecting ground and sky rather than struggling to collapse their distance.

Maurizio Lazzarato’s recently translated Signs and Machines: Capitalism and the Production of Subjectivity falls somewhere in this sphere, effectively balancing and joining critiques of contemporary capitalism, complex philosophies of subjection (or the complex social production of individual subjectivities), and everyday existence, touching current western politics, yet preserving a general openness and applicability. While in essence a theoretical text, Signs and Machines manages to translate abstract systems of micro-politics and semiotics into clear contact with a more grounded reading of affect, the body, and the political potential of any and every given subject, retaining a broad scope of accessible praxis.

...(more)

_______________________

Bargee

1920

David Bomberg

_______________________

Truth

Andrée Chedid

Translated from the French by Lynne Goodheart and Jon Wagner

The Truth is nothing but a lie

Tenacious lmirage of the living

It mocks our vigilance

And petrifies time

Truth is armed

Its spur the forbidden

Its bronze laws segregate us

Its words have walls and ceilings

Its single target a delusion

Sowings abound

Harvests are legion

Rather let us salue our fugitive suns

Words freed from symbols

Our paths on the move

Our multiple horizons

Heinz Trökes

1913 - 1997

_______________________

The poet and the dictionary

Alan Wall

fortnightly review

(....)

Geoffrey Hill’s poetic career has been mediated through his engagement with the dictionary. And that dictionary is first and foremost the OED. There is no greater dictionary in the world, and its making constitutes one of the great intellectual events of the twentieth century, though it started life in the nineteenth. There had never been anything like this before. Now the language itself has become the documented labyrinth of its own manifold meanings. Now history can be traced uttering itself thus and thus in one mutating word after another. The thought of a poet writing in English who would not grow excited turning the pages of the OED, or clicking on the electronic version, is so dismal that one wishes such a personage an even smaller readership than modern poets normally manage to acquire.

The anti-self to our word-blind, purblind poet is undoubtedly Geoffrey Hill. His verse uses lexicography and philology as heuristic principles. Where Robert Graves leapt out of the window after Laura Riding (even if he did go down a storey first), one suspects it would require the defenestration of Hill’s beloved bound set of the OED to elicit any such voluntary lapsus from him. The White Goddess, being no better than she should be, might have had a slightly harder time of it, had she been strutting her stuff in Worcestershire. With A. E. Housman to the left of her, and Geoffrey Hill to the right, she would have received some very old-fashioned looks indeed; chilly gazes from fellows not so easily beguiled. And acerbity is a necessary part of our theme. Acerbity is integral to Hill’s achievements in both verse and prose. Sentimentality is anathema. There are no flies on this fellow. The constable’s son is nothing if not forensic. Every emotion is likely to be treated as the scene of a crime, past, present, or to come.

...(more)

_______________________

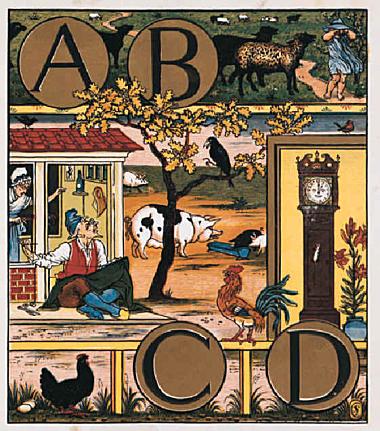

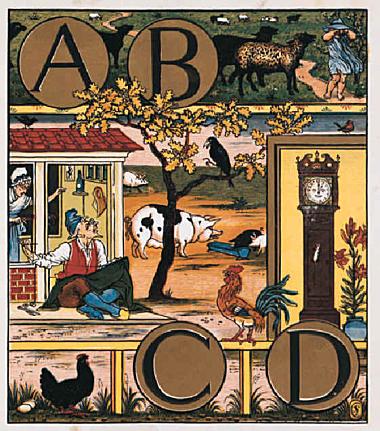

The Alphabet of Old Friends

1874

Walter Crane

1845 - 1915

_______________________

I Didn't Come Here To Make Friends: An Exchange With Michael Lista

By Jason Guriel

maisonneuve

(....)Michael Lista

Don’t think your subject, whatever it may be, imparts any fascination or nobility to your poem. A poem about a personal tragedy doesn’t get any more of a pass than a poem about The Real Housewives of New Jersey—it’s all in how it’s written. Poems are also bad places to do advocacy, inefficient places to politic. A poem’s town square is mostly empty, its bullhorn out of batteries, its soapbox too short. Even a poet as great as Seamus Heaney fell victim to the impulse, when in a moment of nationalist zeal he wrote his worst poem, “Open Letter,” a perspicuously partisan bit of doggerel that whipped the government of his tongue mum. Don’t make writing choices that make your work easier, and then blame them on the world. Don’t write in sentence fragments because you think the world is fragmentary. Don’t rely on elision and then say the world is discontinuous. Don’t write facile absurdism on account of the world being absurd. It isn’t just fragmentary and discontinuous and absurd; as Siri keeps reminding you, it’s also whole and contiguous and intelligible.

(....)

The poetry world is so like the fashion world that way, isn’t it? Trend-driven and often emptily stylish. The only difference is that at least fashion recognizes and makes the distinction between prêt-à-porter and haute couture, a line that for all intents and purposes is the bottom line. People buy and wear and live in the former, and only marvel curiously at the latter....(more)

_______________________

Harrison Birtwistle: Chamber Music

Settings of the writings of US Objectivist poet Lorine Niedecker (1903-1970), scored for soprano and cello in 1998 and 2000, begin and close the album. As Bayan Northcott writes in the booklet, “These concentrated songs demand the utmost of their performers in precision, expression and timing. As in Webern’s settings, the few words and notes on the page can seem to imply whole worlds of thought and feeling”.

player.ecmrecords.com/harrison-birtwistle--chamber-music

via Flowerville

_______________________

Cosmos and History Vol 9, No 2 (2013)

Memory, History, and Pluripotency: A Realist View of Literary Studies

Martin Goffeney

Abstract

Speculative realism has, over the course of its rapid and controversial emergence in the past decade, been frequently criticized from the perspective of historical materialism, for its putative reliance on abstraction and eschewal of a sufficiently rigorous ideological alignment. This paper takes such critiques as a starting point for an examination of the contributions recent thought in the area of speculative realism has to offer the study of the humanities – specifically, the study of literature and literary history. In particular, contemporary realist thought has the potential to enable scholars of literature to move beyond the anthropocentric and specialized notions of history as an exclusively cultural entity, which have dominated the discipline since the twentieth century. Paying especially close attention to the work of Graham Harman and Manuel DeLanda, it is my argument that emergent realist philosophy offers literary scholars a set of powerful conceptual tools which can be put toward the work of accounting for the hitherto neglected ontological status of the literary text – illuminating the status of the text as a particular variety of real and physical object that participates in a system of real and physical history and memory.

21st Century Speculative Philosophy: Reflections on the “New Metaphysics” and its Realism and Materialism

Leon Niemoczynski

Abstract

Regarding the state of contemporary metaphysics, as it has been said, “There’s something in the air.” My goal in this essay is to offer some brief reflections on the state of contemporary metaphysics, otherwise called contemporary “speculative” philosophy – the “something in the air” – that has resurfaced within the early part of the 21st century. In order to clarify the nature of the new metaphysics in question I proceed by isolating geographically and topically two main tendencies of thought which appear to constitute it: namely continental realism and continental materialism. I argue that clarifying the nature of these tendencies better characterizes what metaphysics means today. With respect to the possible ambiguity of “continental realism” or “continental materialism” in the 21st century, a consideration of “speculative realism” seems necessary if only to position my analysis upon a specific conceptual map. From there I offer thoughts as to how contemporary continental realism and materialism (the “new metaphysics”) may be said to be defined first and foremost by its engagement with a concept identified as “correlationism,” a central feature of the new metaphysics’ rejection of the sort of philosophy that has come before it.

_______________________

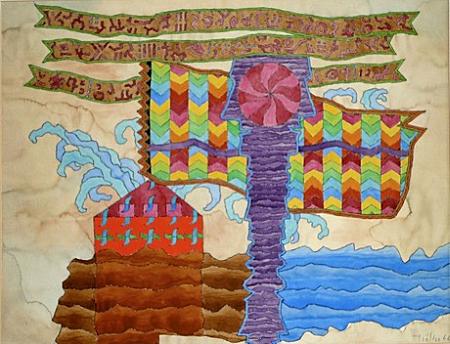

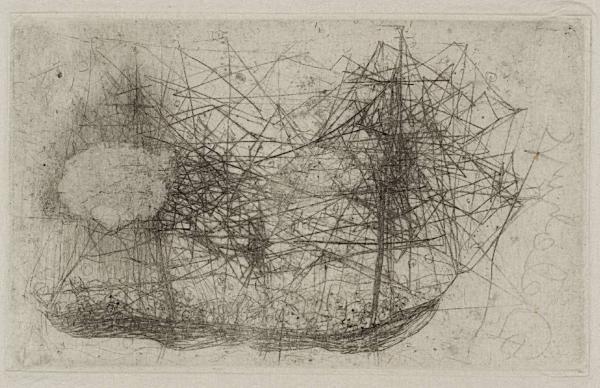

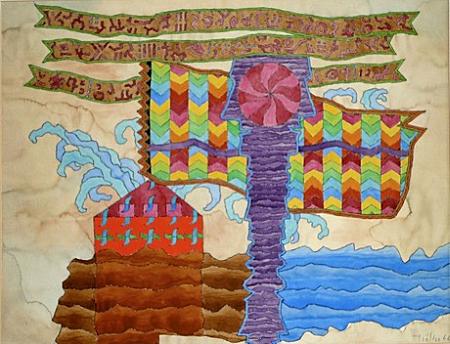

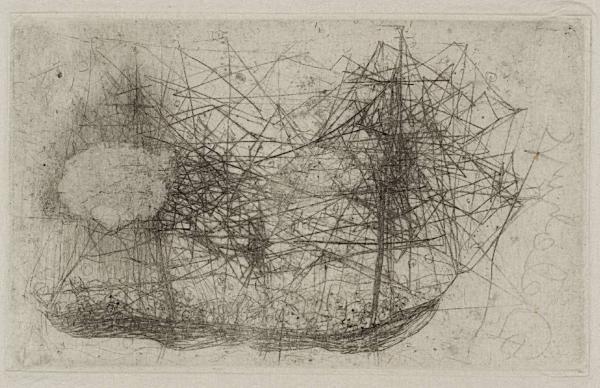

[ship]

c.1937-50Wols

_______________________

Endless recordingThe video archive. The photo archive. Endless recording. Endless photography.

Too many recordings. Too many shoots. When will we ever watch these things? Look at these things? Who has the time? But that’s not the point. It’s enough that’s it was recorded done. That the gesture was made. Enough that we’ve backed up reality. That the event has been stored.

The event, lived in the mode of what it will have been. Real things, experienced as more or less perfect opportunities to produce this ‘will have happened’.

And what happens now is entirely displaced by a planned future time in which it will be to be experienced. And the present is entirely displaced by a planned future present in which we will watch it again. The present does not count. The past is archived. The future is the time in which we’ll live through the past…

Experience is deferred, as events are deferred. Experience is not experienced. Not lived through. What happens no longer happens.

And time is calling out. The present is crying for help. And we are calling out. We are crying out for help...

Nietzsche And The Burbs

Lars Iyer

Beehives, Approaching Storm

c.1950

Joan Eardlley

d. August 16, 1963

_______________________

Holding Court

Clive James

(....)

I used to notice everything, and spoke

A language full of details that I’d seen,

And people were amused; but now I see

Only a little way. What can they mean,

My phrases? They come drifting like the mist

I look through if someone appears to be

Smiling in my direction. Have they been?

This was the time when I most liked to smoke.

My watch-band feels too loose around my wrist.

My body, sensitive in every way

Save one, can still proceed from chair to chair,

But in my mind the fires are dying fast.

Breathe through a scarf. Steer clear of the cold air.

Think less of love and all that you have lost.

You have no future so forget the past.

Let this be no occasion for despair.

Cherish the prison of your waning day.

Remember liberty, and what it cost.

(....) ...(more)

_______________________

>

Stonehaven Harbour

Joan Eardley

_______________________

Relingos

Valeria Luiselli

tr. Christina MacSweeney

brooklyn quarterly

(....)

A group of architects from the National University (UNAM), headed by Carlos González Lobo, have christened these spaces “relingos.” I’m not sure where the term comes from, but I imagine it could be related to the realengas of old Castilian, a term that refers to pieces of land not belonging to the Crown, abandoned to disuse. (The strange ups and downs of words: in certain Latin American countries, realenga is now used to talk about an animal with no owner; in others, the word is synonymous with “layabout.”)

I’m also pretty certain that relingo is derived from another similar concept: the terraines vagues of the Catalan architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales. Just like a relingo, the terraine vague is an ambiguous space, a piece of waste ground without defined borders or limiting fences, a species of plot on the margins of metropolitan life, even if it is physically to be found in the very center of a city, at the junction of two main avenues, or under a newly built bridge.

(....)

Spaces survive the passage of time in the same way a person survives his death: in the close alliance between the memory and the imagination that others forge around it. They exist as long as we keep thinking of them, imagining in them; as long as we remember them, remember ourselves there, and, above all, as long as we remember what we imagined in them. A relingo—an emptiness, an absence—is a sort of depository for possibilities, a place that can be seized by the imagination and inhabited by our phantom-follies. Cities need those vacant lots, those silent gaps where the mind can wander freely.

...(more)

hat tip to Riley Dog_______________________

Field of Barley by the Sea

Joan Eardley

_______________________

Rounded with a Sleep

A new poem by Clive James

tls

The sun seems in control, the tide is out:

Out to the sandbar shimmers the lagoon.

The little children sprint, squat, squeal and shout.

These shallows will be here until the moon

Contrives to reassert its influence,

And anyway, by then it will be dark.

Old now and sick, I ponder the immense

Ocean upon which I will soon embark:

As if held in abeyance by dry land

It waits for me beyond that strip of sand.

...(more)

Clive James on death, dragons and writing in the home stretchthe conversation

Clive James at the Poetry Foundation

_______________________

Corn Feverfew III

Joan Eardley

_______________________

The Country North of Belleville

Al Purdy

Bush land scrub land -

Cashel Township and Wollaston

Elzevir McClure and Dungannon

green lands of Weslemkoon Lake

where a man might have some

opinion of what beauty

is and none deny him

for miles —

Yet this is the country of defeat

where Sisyphus rolls a big stone

year after year up the ancient hills

picknicking glaciers have left strewn

with centuries' rubble

backbreaking days

in the sun and rain

when realization seeps slow in the mind

without grandeur or self deception in

noble struggle

of being a fool –

(....)

And this is a country where the young

leave quickly

unwilling to know what their fathers know

or think the words their mothers do not say –

Herschel Monteagle and Faraday

lakeland rockland and hill country

a little adjacent to where the world is

a little north of where the cities are an

sometime

we may go back there

to the country of our defeat

Wollaston Elzevir and Dungannon

and Weslemkoon lake land

where the high townships of Cashel

McClure and Marmora once were —

But it's been a long time since

and we must enquire the way

of strangers –

...(more)

.....................................................

Looking For Al Purdy

The poetry of a land left behind.

Drew Gough

maisonneuve

(....)

There are only two chairs on the deck at the Purdy A-Frame, but what chairs they are: having once cushioned hundreds of illustrious Canadian rumps, the Muskoka loungers are the furniture of the nation’s artistic history. Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, Lynn Crosbie, Milton Acorn, Dennis Lee, Stephen Heighton, George Bowering. Writers who were just becoming writers, writers who weren’t yet writers and writers who had stopped being writers, all passing wild grape wine and words between the chairs. They fought over ideas, laughed and swore, and, by almost all accounts, kept on drinking.

Eurithe leans back in the sun and I ask her question after question about Al, whom I never got to know. That is to say, whom I never met. These are failings of mine: having been born a little too late or having learned to drive a little too late to visit him here, having not read good Canadian poetry, and his poetry in particular, while he was still alive. He died in 2000, quite far from where his wife and I sit in Ameliasburgh. Eurithe is patient and funny as she gives me his advice on writing (“you’ve gotta chase the money”; “write for anyone who will send you around the world”) and on what life at the A-Frame was like—cold at first, then warmer; always full of voices, Ondaatje’s leonine purr or Atwood’s cantering drawl.

This year marks Eurithe’s last chance to fight with the land to make it fit the image in her mind. It occurs to me, as we finish off the cinnamon buns, that I’ll be the last writer to visit Purdy here. Then I realize he’s not.

For years, I’ve been looking for Al Purdy. But not before I spent years avoiding him, in the same way I avoided everything from the place where I grew up. I had the firm conviction that when you leave home—especially if home is a farm that doesn’t work as a farm, where the power is sometimes shut off because the electricity bill hasn’t been paid, on a laneway populated with tarot card readers, glass-blowers, playwrights and a woman firmly believed to be a witch, near a small town with no industry other than tourism and barely that anymore—you want to stay gone. You scorn home when it peeks its head into the new life you’ve built: during a casual run-in with an elementary school classmate on the streets of your new city, or when a poem about it appears on a third-year university syllabus.

...(more)

_______________________

A Field of Oats

Joan Eardley

|