|

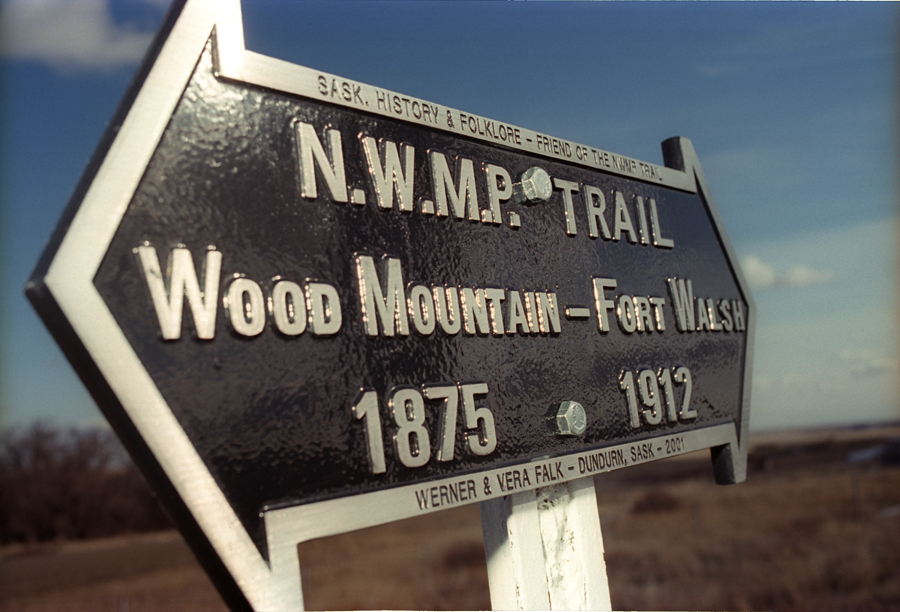

(f/e) CHIMNEY COULEE go to a quick history - click here With diary entries from Moise Vallée, the winter of 1887, Edmonton. "Sixty or so Métis families in the 1870s. You ever wonder what happened to us Métis. We scattered. Buffalo ran thin, looked scrawny in that last hunt. The buffalo, deer, elk, grizzlies, antelope, lots liked the area in the winter. Protected. Chimney Coulee was our winter home for a time, a refuge especially after the NWMP came to post there. They watched us like hawks - we French - and we had good influence with the Indians. We advised them on their treaties. The English knew that. In the summer we, most anyway, traveled to Qu'Appelle, across the prairie before the grass grew up to your knee, just as the water was running in trickles and the buffalo moved in to graze; unpredictable herds. The carts could get stuck in the snow left over. The NWMP posted there used the name East End, meaning I suppose the east end of les Montagnes des Cyprès, the Cypress Hills to the English. Or, it was an ironic and loving (maybe) reference to the east end of London, which at the time was pure poverty - poor and immigrant people. Our first winter was 1871 with the HBCs Isaac Cowie, in what some named Hunter's settlement, in the coulee, what came to be known as the Chimney Coulee, I had a new wife back in Qu'appelle, her name was LaReine Davis, and she was good to me. She graced me with her long loving arms, all that stuff, and her demanding thoughtful nature. I was lucky. We had children. One, a daughter born in Maple Creek, died at two days old. Maybe she was lucky too. Around 1879, we were trading for the HBC as usual, don't remember exactly but it was after the deep winter when the snow was so thick the animals were perishing and so were we, some of us rode into Montana after some of the last buffalo and we found other places; we never came back to Chimney Coulee. After that we hunted and traded in the Hills west of there. Tensions were pretty high. Some disappeared into Medicine Hat, Pincher Creek, Maple Creek, or headed up to the North Saskatchewan. A lot of us took scrip from Treaty Four and Seven. But that did not last long; speculators, and opportunists. Besides there was more work to be had dealing with Fort Edmonton and other posts and the people who came through them. Back in the 50s Palliser, even then, he predicted that settlers were coming and that our way of life was limited. But not him or Hind or Butler in those times thought the Cypress Hills or most parts of Palliser's Triangle, would support settlement." From the 1840s or so, the area in and around Chimney Coulee was a hunters' and traders' refuge. It is still well protected. It was a kind of neutral territory in Indian country back then. Neutral only in that no particular group could claim it as their land. Cowie (1913:432) says, " ... the hostile tribes (the Blackfoot, the Cree, Assiniboin, Saulteaux, etc.) of the surrounding area feared to enter (the Cypré Hills) for hunting purposes." That was a dangerous and tough time. Cowie said, "Only wary and watchful war parties of any tribe ever visited the Hills..." So, if a grizzly bear did not kill you with one swipe to your head, another war party might with a buffalo hammer (like the one below), a more grizzly implement with likely less instant results when used on a human.

|

@ Chimney Coulee images and text © D. Wall (except where otherwise noted)

Isaac Cowie, when he was a young employee of the Hudson's Bay Company learning the ropes, and others travelled to the coulee from Qu'Appelle specifically to operate a HBC trading post during the winter of 1871/72. Robert Jackson was one of Cowie's first choices because he was said to have skills as a Blackfoot translator. However, Robert, Cowie said, turned out not to be quite as advertised. Even so, Cowie traded with the Cree, Blackfoot, Assiniboines until it got too dangerous in the spring. They took thousands of furs, grizzly, elk, buffalo with them. Their carts were so laden with goods that they got stuck in the snow drifts often on the long drive back to Qu'Appelle. The HBC never came back to the Coulee, opting instead to have the Métis trade for them and return the goods to various forts: Carlton, Pitt, Edmonton, Qu'Appelle, Walsh and so on. The Métis were a powerful force in the 1870s. Governor Morris noted that they refused to recognize the North West Council because they felt there was no law, let alone enforcement, especially around events like the massacre of 26 Assiniboines in May of 1873 at the Cypress Hills by American whiskey traders and the dirty liquor trade. Their response was to begin setting up their own Council west of Qu'Appelle. Morris, McKay says, wrote June 4, 1873 to the Métis leadership insisting there was law in the land. In 1874 the North West Mounted Police did march to the Cypress Hills. Thomas (p.6) says, "The police soon established themselves in the opinion of the Indians as their protectors." Later still in the Cypress Hills, in the 1890s, Macleod and other Canadian administrators and the Churches had taken authority over most aspects of life in the area. Besides ranchers and settlers were moving in to the area quickly then. Macleod was an efficient judge. He and the Supreme Court could pass a sentence of five years for illegally selling whisky - just like that - and you'd be on the train to Medicine Hat before you could blink. A job well done he would muse and, then, go back to Fort Macleod, Medicine Hat or Calgary and have whisky himself with his fellow Supreme Court justices big Judge Wetmore, McGuire, or the Chief Justice, the steady Rouleau, or wiry Richardson, even with Lougheed or the Bishop, Cyprian Pinkham. He might just be back in time to have dinner with Haultain. He was a rich and influential man with lots of visitors and friends, but no wife on hand. No legal wife at least.

"Lougheed

(later Senator Sir

James Lougheed) was one of the first

lawyers to practise in southern Alberta. He was practising in

Medicine Hat in 1883 and then moved to Calgary. ...

The first two Stipendiary

Magistrates in the North-West Territories were appointed in 1875. One was Colonel James F. Macleod.

Born in 1836, ... . (a) member of the Upper Canada Bar from 1860,

Colonel Macleod joined the NWMP instead of practicing law. He was Commissioner of the NWMP from 1876 to 1880

and as such had the powers of a Stipendiary Magistrate and tried many cases in what is now southern Alberta.

After serving as Commissioner, Macleod continued as a Stipendiary Magistrate until 1887

when he became a judge of the Supreme Court of the North-West Territories." (p.2/3)

(Macleod's father was a British army officer;

the Supreme Court of the NWT was formed in 1886)

Bryant, Marian E., "The Early Days: How did Alberta's Legal Profession Get Started?"

www.lawnow.org

Frenchman River Valley, Eastend PFRA Irrigation Project and the Butala or Morvik cattle being moved, 8km S of Chimney Coulee

images and text © D. Wall (except where otherwise noted) With thanks for residence and research assistance to Eastend Arts Council and Stegner House

|