|

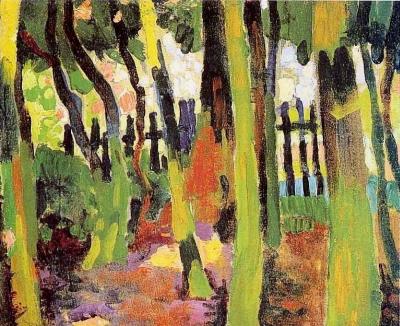

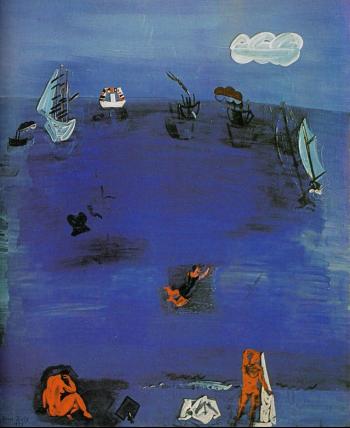

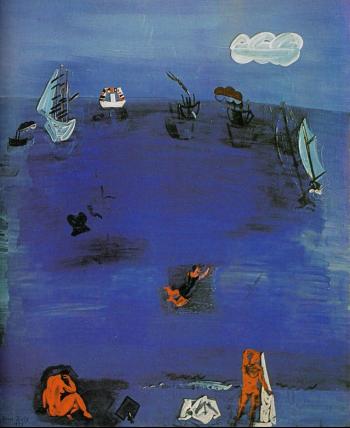

André Derain

1880 – 1954

_______________________

Loneliness In Linden

Charles Bernstein

—After Wallace Stevens

The fear and the hum are one.

Monuments of show gumming the works

Until the weather grows tired of the people

And the people grow tired of the dance.

Jamais, jamais, jamais, again.

The measure of the town against a dampening sky

Cobbling together six million tunes

Into more than the tones tattoo

Or their scrambled mosaic forecloses.

And if the fume and the hope

Are one? My monkey, from ’49

Steps as silent as those songs

Along the cratered dark

Where Jews do Jewish things

No one pretends to understand

Or are they pilgrims on this night

When the fear and the hum are one?

Three Poems

Charles Bernstein

_______________________

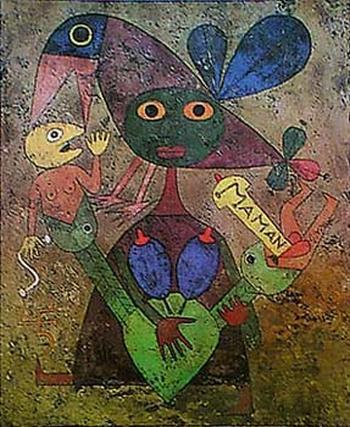

Televentre

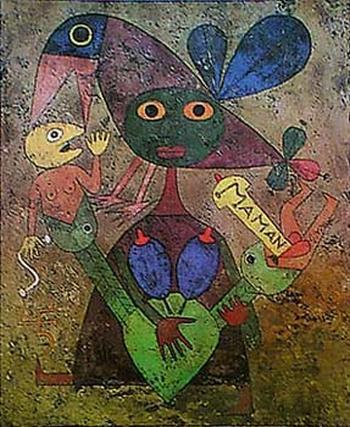

Victor Brauner

b. June 15, 1903

_______________________

Boundary Conditions

Adrienne Rich’s collected poems

Dan Chiasson

(....)

Rich’s refusal to be an archetype of femininity made her an archetype of feminism, a courageous trade but one that confronted her with aesthetic challenges virtually unprecedented in American poetry. Perhaps no American poet who started in the mode of accommodation so abruptly broke ranks, inventing for herself a new kind of discipline whose ethical rigors demanded fresh forms. The challenge was to make poems that crystallized her political commitments—especially to women’s consciousness and power—but did not blunt their own artistic force. Many poets of the time, influenced by Rich, decided that the idea of art was a mere bourgeois confection. Rich never did. It was too late; she had learned its uses. There was always, inside her, the fifties formalist, brought up, as she put it, “within the circumference of white language and metaphor.” Her models were Anne Bradstreet and Emily Dickinson, brilliant women with domineering fathers, who wrote poems that acted necessarily as both expression and concealment, and whose achievement was timed to detonate in the future, when the world had prepared for them a fit audience.

Rich’s “Collected Poems: 1950-2012” (Norton) confronts us everywhere with what she called “the war / poetry wages against itself.” She grew as a poet by self-repudiation, redefining motherhood and disowning, with real pain, her delegated roles as wife, mother, straight woman, and privileged white American. Her stands against various forms of oppression were also stands against roles so deeply ingrained as to seem, to her, essential. She never affirmed anything without first condemning its opposite, and although she saw life in these polar terms, she located the antipodes within herself. “Between extremities / Man runs his course,” wrote Yeats, whose politically inclined lyricism substantially influenced Rich’s work. The key to Rich’s genius, in fact, is Yeats’s famous aphorism, maybe the best thing anybody ever said about the art: “We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.”

...(more)

_______________________

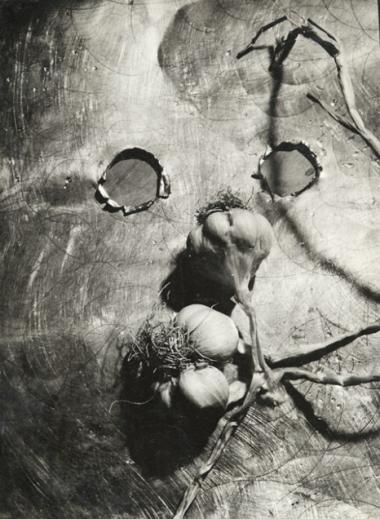

photo - mw

_______________________

John Ashbery: “The Skaters”

[from Rivers and Mountains, 1966]

– a critical and genetic digital edition –

(....)

Subtracted from our collections, though, these go on a little while, collecting aimlessly. We still support them.

But so little energy they have! And up the swollen sands

Staggers the darkness fiend, with the storm fiend close behind him!

True, melodious tolling does go on in that awful pandemonium,

Certain resonances are not utterly displeasing to the terrified eardrum.

Some paroxysms are dinning of tambourine, others suggest piano room or organ loft

For the most dissonant night charms us, even after death. This, after all, may be happiness: tuba notes awash on the great flood, ruptures of xylophone, violins, limpets, grace-notes, the musical instrument called serpent, viola da gambas, aeolian harps, clavicles, pinball machines, electric drills, que sais-je encore!

The performance has rapidly reached your ear; silent and tear-stained, in the post-mortem shock, you stand listening, awash

With memories of hair in particular, part of the welling that is you,

The gurgling of harp, cymbal, glockenspiel, triangle, temple block, English horn and metronome! And still no presentiment, no feeling of pain before or after.

The passage sustains, does not give. And you have come far indeed.

Yet to go from “not interesting” to “old and uninteresting,”

To be surrounded by friends, though late in life,

To hear the wings of the spirit, though far. . . .

Why do I hurriedly undrown myself to cut you down?

“I am yesterday,” and my fault is eternal.

I do not expect constant attendance, knowing myself insufficient for your present demands

And I have a dim intuition that I am that other “I” with which we began.

My cheeks as blank walls to your tears and eagerness

Fondling that other, as though you had let him get away forever.

The evidence of the visual henceforth replaced

By the great shadow of trees falling over life.

A child’s devotion

To this normal, shapeless entity. . . . ...(more)

text/works

— A Modern Poetry Library

Robin Seguy, editor

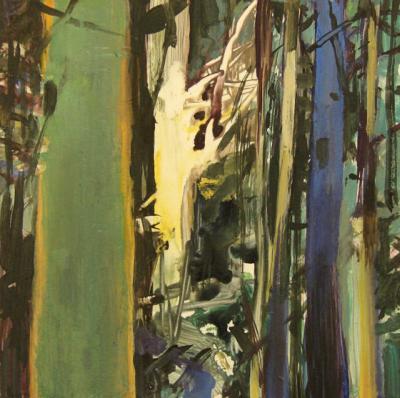

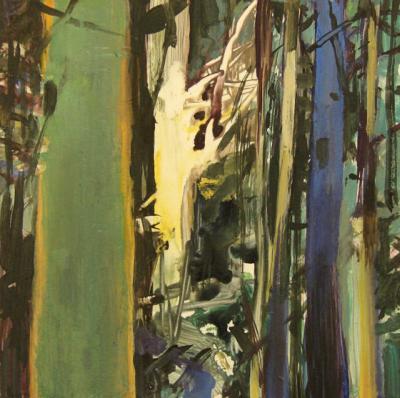

light in the forest

Joseph Stella

b, Jun 13, 1877

_______________________

From Ferrements, “Tombeau de Paul Eluard”

Aimé Césaire

Translation from French by A. James Arnold and Clayton Eshleman

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

Blazon of blows on the shattered body of dreams

first snowy morning

today

very amorphous when all lights out

the landscapes collapse

onto the most distant sandbanks

the sirens of lightships have been sounding two nights

Paul ELUARD has died

you who were the lay of innocence

who returned science to its origins

standard of the fragile seed stronger

than chance in the struggle of the wind

ELUARD

neither can you lie in

nor have access to earth purer

than these eyelids

than these simple people

than these tears

in which pushing aside the finest grass of the fog

you stroll quite clear

joining hands

connecting paths

challenging the purple word of the shipwreckers of dawn

perched on the sun

...(more)

_______________________

Ernst Wilhelm Nay

b. Jun 11, 1902

_______________________

In the Space between Words Begin

Laura Mullen

In the space between words begin

Attempt

In the space

At dawn the newly risen dead uncomfortable

In their restored bodies

Situation: from ‘wandering’ to rest

Loneliness to solitude. Believing

Is seeing, experience

An accrual of images

The newly risen dead find their bodies

Uncooperative, awkward, ugly

as in any

Horror flick

I wandered lonely as a van full of hippies

In the space between words

roots

“what shall I talk about”

Situation: a man at his desk pages through

Another’s writing closes his eyes seeks rhymes

For the following: daffodils, thought . . .

I fear I can no longer think

I fear I am no longer that which thinks

Or that a certain kind of thinking’s lost

Light, light, light, light. Let there be a place

From which a way seems clear or clearer

Out of the house into the golden

And never

Laura Mullen -- Dark Archive

reposted from flowerville

Laura Mullen poems in Bomb 1 2 3

Laura Mullen at the Poetry Foundation

_______________________

How Poems Think

The power of lyric poetry lies in negation, not self-assertion.

Ange Mlinko reviews Reginald Gibbons's How Poems Think

(....)

I look at what I see as the necessary and productive self-alienation of the poet, who must work in words so closely, and with such openness to language, that only by coming to see the words on the page, and to hear them in the ear, as belonging as much to themselves and to the language as to the poet who composes them, can the poet discover how to think with them and through them, beyond the artistic limits of the ingrained individual habits of language and poetic thinking, and beyond the limits imposed by the poet’s self-positioning within culture.

As Gibbons knows, and tries to say with nuance, this is a contrarian viewpoint in our present moment, when self-positioning—mainly through the finer cross-sections of identity politics—is the cicada’s pitch for advancement. What if the full power of lyric utterance lies in its apophatic tendencies: the discovery of what must be said through negation rather than self-assertion, through surprise rather than certainty?

...(more)

_______________________

The Self Seers

(Death And Man)

1911

Egon Schiele

b. June 12, 1890

_______________________

Blue Ruin: Totality and Acceleration

Mckenzie Wark

rhizome

(....)

This is one sense in which one can think about art as "modern." Art was a space, not for retreat from abstraction but for playing out its possibilities in an experimental fashion. Whatever manifestos the artists signed, and no matter what readings we may put on – say – a Turner painting of a locomotive, the practice of making the art was caught up in experimenting with the technical possibilities of abstraction.

What I think changes is that we now know how all this ends. The capacities of abstraction seize hold of the materiality all around it, opening up its potentials. Modernity was a great liberation front. Only it wasn't about liberating a people, or a class, or a gender. What modernity liberated was carbon. Modernity liberated fossilized carbon in the form of oil and coal and natural gas. Modernity fired it great engines on these fossils. (Think of Marinetti crashing his Bugatti and writing the "Futurist Manifesto" about it.) Modernity released enough carbon dioxide into the atmosphere to change the climate of the whole planet, forever.

Climate change is the modern fully realized, the modern as tending towards undoing its own conditions of existence. Mitigating its effects is going to take all the ingenuity – technical, aesthetic, not to mention social and political – that we can muster. Mitigating climate change is not just a technical problem. Nor will the economy just "naturally" adjust. And there's no hiding from it in romantic "back to nature" fantasies. If we refuse to deal with abstraction, then like Martin Heidegger the best we can do is throw up our hands and say "only the Gods can save us."

(....)

There is a certain popular delight in imagining the modern world in ruins. It's a theme Walter Benjamin identified early in the 20th century. In the shadow of the bomb, the Beats and their contemporaries occasionally gave it an incendiary cast. But what if we push beyond the picture of atomized cities to imagine not what passes but what is created at the end of human time? Our permanent legacy will not be architectural, but chemical. After the last dam bursts, after the concrete monoliths crumble into the lone and level sands, modernity will leave behind a chemical signature, in everything from radioactive waste to atmospheric carbon. This work will be abstract, not figurative.

...(more)

via Deterritorial Investigations Unit

Strandszene (Shore line)

Michael Peter Ancher

(June 9, 1849 - September 19, 1927)

_______________________

Dream

Timothy Morton

(....)

What is this nasty noise telling us? I suggest it is saying that to no extent have we actually started to live the data. To live the data, you need not only to be able to act and to think, but also to hesitate, contemplate, muse, puzzle, scribble, doodle, read. To dream. We need to start dreaming. This all sounds very counterintuitive in an age of ecological emergency. But it might be exactly right, even politically expedient, in an era of neoliberal shock doctrines in which the injunction to get off our backsides and work now penetrates all areas of our lives from primary school to Candy Crush. And this doctrine is just version 7.0 of the agricultural logistics that has been running in the background for over twelve thousand years. A logistics that has, by now, successfully wiped out fifty percent of actually existing animals and is doing a fantastic job of making Earth uninhabitable for currently existing lifeforms—making Earth uninhabitable in the name of survival.

...(more)

Lexicon for an Anthropocene Yet Unseen

edited by Cymene Howe and Anand Pandian via Monoskop/log

_______________________

Migration Series

Jacob Lawrence

1917 - 2000

_______________________

What the Performative Can’t Perform

McKenzie Wark on Judith Butler‘s Notes Towards a Performative Theory of Assembly

(....)

There is at least the beginning of an inkling of media theory in Butler, which I supposed is to be welcomed, given how much political theory still thinks it is in the Greek polis, and indeed thinks the Greek polis is more than a myth. Butler: “Of course, we have to study those occasions in which the official frame is dismantled by rival images, or where a single set of images sets off an implacable division in society, or where the numbers of people gathering in resistance overwhelms the frame…” But which are those occasions? Perhaps what is crucial here is the capacity to interrupt the temporality and narrative coherence of virtual geography.

Mediated narratives precede events. The functions of news is to fit events into the template of a handful of simple stories, as Benjamin already knew. The event that frustrates the narrative framing held open for it in advance is the one most likely to receive inconsistent presence in the media and be most open, at least for a time, to queer acts of performativity. This of course need not always be a good thing. The first twenty-four hours of after the planes flew into the world trade center are a signal instance of a dismantled frame. After that, the frame was put back in place and insisted upon relentlessly.

(....)

In this sense, despite some gestures towards Haraway and Stengers, I don’t think Butler has really heard them, or through them, the unbidden demand impinging on us, beyond ethics and even politics, of that which has no face. An ethical obligation to non-life doesn’t really seem thinkable within Butler at all. Infrastructure supports the body, but the body owes it nothing. Faceless things don’t call for any care. They simply are. Having remaindered labor as a category of what bodies are and do, infrastructure can’t appear as part of the body itself, as what the laboring body has made, as dead labor.

What we’re left with then is not a logo-centrism but a corporeo-centrism. It isn’t reason or speech or the individual human body that is the alpha and omega, but it is still the human body. Its an inclusive liberalism, of differences but not antagonism. It wants to eschews any claim to universality, but still takes the Greek polis as the model for political thought, and political thought to be a generalizable category. It stresses the vulnerability of the body rather than its capacity for labor. As such, it can only think the inhuman as the support of the body. As such, this is an exemplary set of essays on how far one can extend political theory, one one still limited by the partial category of the polis itself.

...(more)

_______________________

Politics and Animals

inaugural issue

Editors' Introduction

If the suppression of nonhuman animals as subjects of political inquiry has distorted political thought, then concerted attention to politics and animals promises a deep revaluation of its essential concepts and categories. As the articles collected in our inaugural volume demonstrate vividly, the question of interspecies justice unsettles received interpretations of political thinkers both ancient and contemporary, challenging and advancing foundational political concepts including membership, representation, freedom, and equality. Providing a cross-section of leading scholarship on interspecies politics, our contributors showcase the full scope of Politics and Animals as a forum for research and debate spanning the vistas of political theory and political science.

...(more)

_______________________

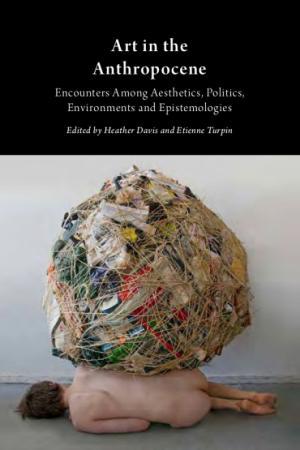

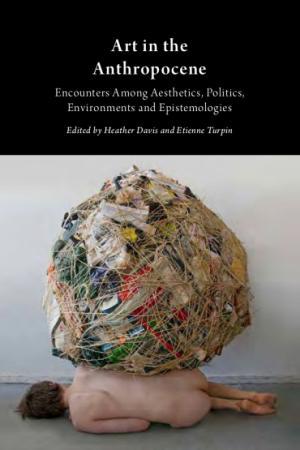

Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies

Heather Davis, Etienne Turpin (eds.)

Critical Climate Change series

Open Humanities Press

(

Contributors include Amy Balkin, Ursula Biemann, Amanda Boetzkes, Lindsay Bremner, Joshua Clover & Juliana Spahr, Heather Davis, Sara Dean, Elizabeth Ellsworth & Jamie Kruse (smudge studio), Irmgard Emmelhainz, Anselm Franke, Peter Galison, Fabien Giraud & Ida Soulard, Laurent Gutierrez & Valérie Portefaix (MAP Office), Terike Haapoja & Laura Gustafsson, Laura Hall, Ilana Halperin, Donna Haraway & Martha Kenney, Ho Tzu Nyen, Bruno Latour, Jeffrey Malecki, Mary Mattingly, Mixrice (Cho Jieun & Yang Chulmo), Natasha Myers, Jean-Luc Nancy & John Paul Ricco, Vincent Normand, Richard Pell & Emily Kutil, Tomás Saraceno, Sasha Engelmann & Bronislaw Szerszynski, Ada Smailbegovic, Karolina Sobecka, Zoe Todd, Richard Streitmatter-Tran & Vi Le, Anna-Sophie Springer, Sylvère Lotringer, Peter Sloterdijk, Etienne Turpin, Pinar Yoldas, and Una Chaudhuri, Fritz Ertl, Oliver Kellhammer & Marina Zurkow.

_______________________

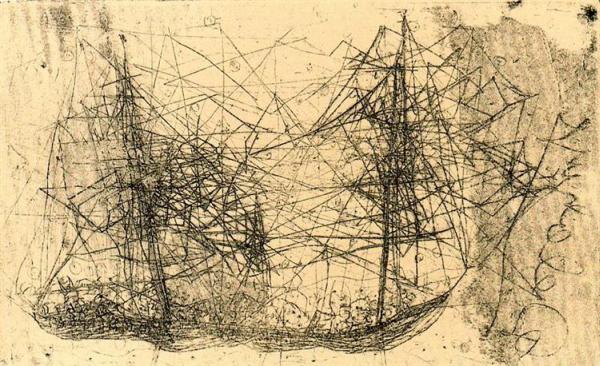

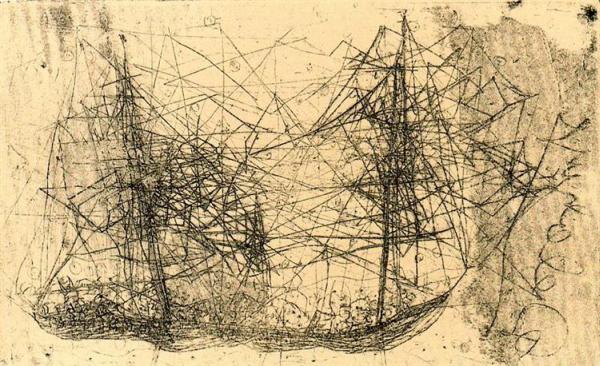

Jacques Villon

d. Jun 9, 1963

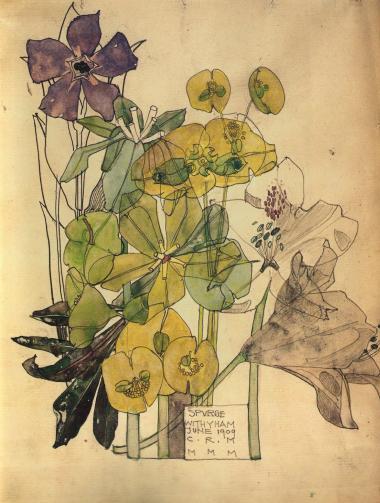

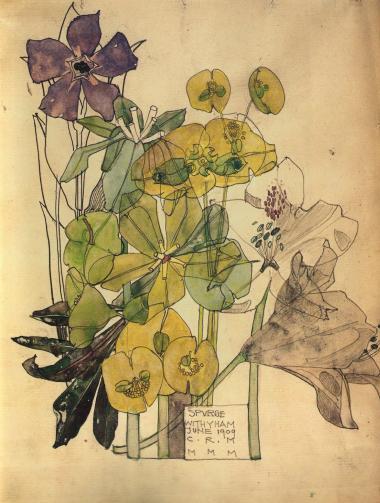

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

b.June 7, 1868

_______________________

These Molten Flowers: on Lola Ridge, radical poet and activist

Zara Raab

The Critical Flame

(....)

Few today have heard of Ridge, but her impact on America society cannot be denied. She was that rarest of creature: a poet whose work brought real, tangible change. Ridge’s poem about Sacco and Vanzetti, for instance, was duplicated by the thousands, passed hand-to-hand among activists, and would help free the labor activist Tom Mooney from unjust incarceration.

(....)

Ridge worked tirelessly as associate editor of Others; later she became the American editor of the transcontinental magazine Broom. In 1920, Huebsch published Ridge’s second book, Sun-up a(n)d Other Poems, again to rave reviews in The New York Times, Marianne Moore’s The Dial, and The Nation. Her third book, Firehead—often compared to Robinson Jeffers’s Dear Judas—was another success, and her poems appeared beside those by Eliot, cummings, Moore, and Williams, in the anthology Prize Poems 1913-1929. It’s remarkable that Ridge would find herself praised by, and compared to, such a broad diversity of her contemporary peers. Her work, charged with political urgency, stands apart from her modernist contemporaries. Her independence, of course, lies at the core of her identity as both an artist and activist:

All violence is but the agony

Of caged things fighting blindly for the right

To be and breathe and burn their little hour.

...(more)

Lola Ridge: The Radical Modernist We Won't Forget Twice

Terese Svoboda

Lola Ridge (1873 - 1941) at the Poetry Foundation

_______________________

Electricity

Raoul Dufy

1937

_______________________

Speed and Information: Cyberspace Alarm!

Paul Virilio

Translated by Patrice Riemens

originally published by CTheory on August 27, 1995

(....)

The big event looming upon the 21st century in connection with this absolute speed, is the invention of a perspective of real time, that will supersede the perspective of real space, which in its turn was invented by Italian artists in the Quattrocento. It has still not been emphasized enough how profoundly the city, the politics, the war, and the economy of the medieval world were revolutionized by the invention of perspective.

Cyberspace is a new form of perspective. It does not coincide with the audio-visual perspective which we already know. It is a fully new perspective, free of any previous reference: it is a tactile perspective. To see at a distance, to hear at a distance: that was the essence of the audio-visual perspective of old. But to reach at a distance, to feel at a distance, that amounts to shifting the perspective towards a domain it did not yet encompass: that of contact, of contact-at-a-distance: tele-contact.

(....)

There is something else of great importance here: no information exists without dis-information. And now a new type of dis-information is raising its head, and it is totally different than voluntary censorship. It has to do with some kind of choking of the senses, a loss of control over reason of sorts. Here lies a new and major risk for humanity stemming from multimedia and computers.

Albert Einstein, in fact, had already prophesized as much in the 1950s, when talking about “the second bomb”. The electronic bomb, after the atomic one. A bomb whereby real-time interaction would be to information what radioactivity is to energy. The disintegration then will not merely affect the particles of matter, but also the very people of which our societies consist. This is precisely what can be seen at work with mass unemployment, wired jobs, and the rash of delocalizations of enterprises.

...(more)

_______________________

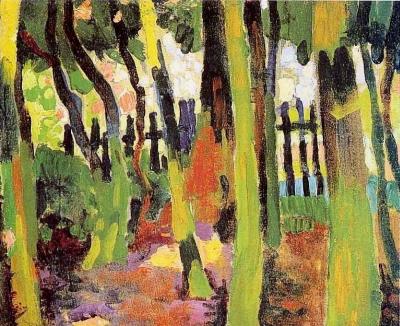

At the Edge of the Wood

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

1913

_______________________

The General

Bernadette Mayer

Later in secret

Later in secret the general

Bends to remove something

To lean against a fresco.

The rules which run

Around the walls

The walls of court

Determine a course,

Declare if he had not:

Sulphur and pitch, sulphur and lead, sulphur and

gum mastic, sulphur and varnish, mixed with the

husks of pine-kernels, sawdust, isinglass, shells

of snails, husks of beans, and seed of myrtle.

From here any direction is shown.

The woods must be razed — resumption of growth

The market growing, profusion, the question

To hold — to hold

Parts or acts in the act of disintegrating wholly.

A sign over the hull — the evening

In a complex of other evenings

Behind the intervening ledge, the general.

Thirteen poems by Bernadette Mayer

Edited by Michael RubySam Truitt

from Bernadette Mayer's long-unpublished early book, The Old Style Is Finding out Something about a Whole New Set of Possibilities

_______________________

Let Them Drown

The Violence of Othering in a Warming World

Naomi Klein

(....)

The most important lesson to take from all this is that there is no way to confront the climate crisis as a technocratic problem, in isolation. It must be seen in the context of austerity and privatisation, of colonialism and militarism, and of the various systems of othering needed to sustain them all. The connections and intersections between them are glaring, and yet so often resistance to them is highly compartmentalised. The anti-austerity people rarely talk about climate change, the climate change people rarely talk about war or occupation. We rarely make the connection between the guns that take black lives on the streets of US cities and in police custody and the much larger forces that annihilate so many black lives on arid land and in precarious boats around the world.

Overcoming these disconnections – strengthening the threads tying together our various issues and movements – is, I would argue, the most pressing task of anyone concerned with social and economic justice. It is the only way to build a counterpower sufficiently robust to win against the forces protecting the highly profitable but increasingly untenable status quo. Climate change acts as an accelerant to many of our social ills – inequality, wars, racism – but it can also be an accelerant for the opposite, for the forces working for economic and social justice and against militarism. Indeed the climate crisis – by presenting our species with an existential threat and putting us on a firm and unyielding science-based deadline – might just be the catalyst we need to knit together a great many powerful movements, bound together by a belief in the inherent worth and value of all people and united by a rejection of the sacrifice zone mentality, whether it applies to peoples or places. We face so many overlapping and intersecting crises that we can’t afford to fix them one at a time. We need integrated solutions, solutions that radically bring down emissions, while creating huge numbers of good, unionised jobs and delivering meaningful justice to those who have been most abused and excluded under the current extractive economy.

...(more) _______________________

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

_______________________

erkenntnis, undings and the grape

or, A Parabolic Translation of Paracelsus, as lifted from the introduction to Die Kunst des Liebens.

Lital Khaikin

3am

(....)

To give things over to song that is led astray from its origin. This is a way of learning to speak, and a way to begin again—

With the testing movement of lips, these words take on unusual forms, all new—taken from another mouth. The idea of their sounds guides my tongue over unfamiliar space, stumbling against small silences. It begins with weiß. Where light is. White is the release of everything that may be contained. It indicates presence, and the permission to look. Everything that appears is a way to write a when around an encounter.

Already too slow, is light, our seeing. Our seeing understood as such only after its happening—versteht wegen ehemalig Anwesenheit—feindlich auf Entfernung. Such a way to know, relying on the having-lost—for every word we give to one another is a cenotaph, and everything that formed its need is obsolete by the time its proof arrives. This is our language. Weggang befindlicht in die Quelle—also the Departure, a way to trace each other back to something vital, leading to the dim beginning of things—the old adage of light as knowledge—empty, empty, containing nothing—

But what space it fills.

After all these things.

Slowness must be necessary, to reconcile with that deceptive quality, which is at once—Aussicht auf der Schatten—that inverse of reflection, which is the habit of making the interior visible.

(more)

Raoul Dufy

1877 - 1953

_______________________

Beckett on Proust and involuntary memory

presented by Tom Clark

The most trivial experience -- he says in effect -- is encrusted with elements that logically are not related to it and have consequently been rejected by our intelligence: it is imprisoned in a vase filled with a certain perfume and a certain colour and raised to a certain temperature. These vases are suspended along the height of our years, and, not being accessible to our intelligent memory, are in a sense immune, the purity of their climatic content is guaranteed by forgetfulness, each one is kept at its distance, at its date. So that when the imprisoned microcosm is besieged in the manner described, we are flooded by a new air and a new perfume (new precisely because already experienced), and we breathe the true air of Paradise, of the only Paradise that is not the dream of a madman, the Paradise that has been lost.

...(more)

_______________________

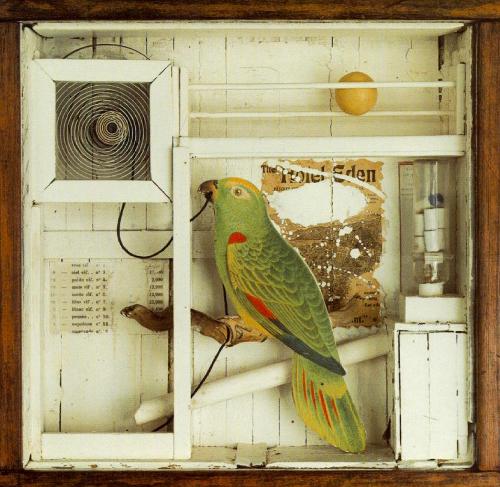

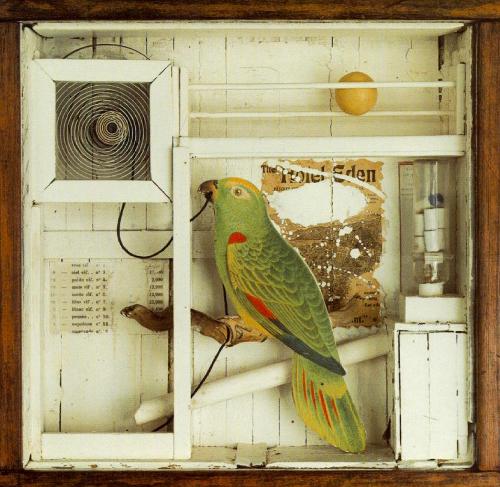

Untitled (The Hotel Eden)

Joseph Cornell

c. 1945

_______________________

'This World, or the Man of the Boxes'

dedicated to Joseph Cornell

Takahashi Mutsuo

Translation from Japanese by Jeffrey Angles

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

(....)

Then

what about these boxes?

The objects captured inside

the princesses

The ballerinas

the rabbit princes

The parrots

the honeybees

the butterflies

Does this man

lodge inside them

Borrowing the forms of these ephemeral creatures?

Like the garden and basement

these boxes are also

Cheap hotel rooms inhabited briefly

by this man’s shadow

It swings upon the roost

pours some sand

Creates nimble cracks across the panes of glass

And then vanishes

The destination for his shadow is the real world

These wistfully nostalgic boxes before us are

The frames around the well through which

We peer into that world and are drawn in

...(more)

_______________________

Untitled (Celestial Navigation)

1958

Joseph Cornell

1903 - 1972

_______________________

Rise Of The Void Towards The Periphery

Jean Baudrillard

ctheory

(....)

One gets the impression that events are hurled headlong in isolation, all on their own as they abruptly and unforeseen get diverted to the point of their flight, i.e., to the peripheral void of the media. Just like physicists are no longer in the possession of the particle except for a vision of its trajectory on a screen, neither are we any longer in possession of pulsating events, except for a cardiogram, nor of representation or memory, except for an (unimaginative) encephalogram, nor of desire or jouissance, except for psychodrama and a cathodic vision.

This is somewhat like procreation in vitro: the embryo of a real event is transported into the artificial uterus of information where many orphan, fatherless and motherless, foetuses are delivered. The event is entitled to the same procreative practices as birth, to the same euthanasic practices as death.

We are unquestionably indebted to this physically pleasing sensation: the sentiment that collective or individual events are plunged into a hole of memory. This debility, no doubt, is due to a movement in reverse, to this parabolic curve interjected into the space of history. For the past cannot represent itself, it cannot be reflected upon unless it prods us in another sense, i.e., with respect to some sort of future or other. Retrospective is solidary with prospective that allows for something to be depicted as surpassed, as stolen and therefore as having taken place. If, by way of a strange revolution, we set out on the course of inverted meaning and get involuted in this dimension of the past, we will no longer be able to represent ourselves. The extension of memory would curve or bend and make a black hole out of every event. We live through this subjectively in the sudden loss of our memories, through the rupture in the continuity of names, faces and familiar forms. With respect to this kind of catastrophe of memory, we are not talking about natural forgetting nor of unconscious repression. Focus is on an inversion of this field of temporal gravitation which no longer allows signs of the past to be bearers of a specific mass, of a nuclear mass necessary for their retention, nor of a mirror of the present in which they could be reflected. The holes in memory are a bit like what has become of the ozone layer, where our protective screen breaks down or disintegrates. Or maybe they are simply not big enough to be engulfed in a way that it could start swirling to unfetter the light particles from the heavy ones, enlarging and deepening the black hole from where dead bodies would release or free up their aerial substance as in the case of Dante and Giordano Bruno. It is in an absolute void that the absolute event takes place. The void therefore can only be relative in view of the fact that death has remained virtual.

...(more)

_______________________

“Persist in Folly”:

Review of Mark Greif, The Age of the Crisis of Man: Thought and Fiction in America, 1933-1973.

John Bruni

electronic book review

(....)

In retrospect, it seems rather hard to miss the influence of the crisis of man discourse on post-WW II literary works—the titles, alone, are a giveaway: Dangling Man (Saul Bellow), Invisible Man (Ralph Ellison), and A Good Man Is Hard to Find (Flannery O’Connor). Before Pynchon and Foucault, Bellow was already addressing “the essential emptiness that has already been a feature of the existence of any abstract Man or human being—the Man who is the subject of the Rights of Man, the person who mattered for intellectuals of the era”. Ellison further upped the ante, reminding readers that who was observing the crisis played a crucial role in gauging the political dissent voiced by those who could not be seen, who remained figuratively underground. And the way back to Adler’s ideological conservatism can easily be glimpsed in O’Connor, namely in her dismissal of Dewey, her use of complex faith-based scenarios to derail liberal humanism, and her various rationales for maintaining the status quo against the pressures of social change.

While Greif treats all of these writers fairly—and Pynchon is rightly acknowledged as the prime agitator in the ranks—he cannot resist coming up with a provocative finale, starting from “outside the guise of scholar” with the proviso: “Anytime your inquiries lead you to say, ‘At this moment we must ask and decide who we fundamentally are, our solution and salvation must lie in a new picture of ourselves and humanity, this is our profound responsibility and a new opportunity’—just stop” (328). An irresistible pull-quote, to be sure, that appears to critics such as Wieseltier as the final word on the matter, an admission of defeat. In the very next paragraph, however, Greif makes a 180 degree turn:

Speaking as a scholar and historian … I can say nothing of this sort, and am embarrassed to have revealed the contemporary person’s outraged instinct. How could I tell anyone to desist? How can the dispassionate analyst ever discourage even what seems to him to be folly? Persist in folly! Without folly, how would we have history?

A good question, indeed. We might look at how history is made, lived, and not let the subject of the human subject obscure too greatly our critical thinking about the historical time we call modernity, and how it instills crucial differences between subjects and objects.

...(more)

_______________________

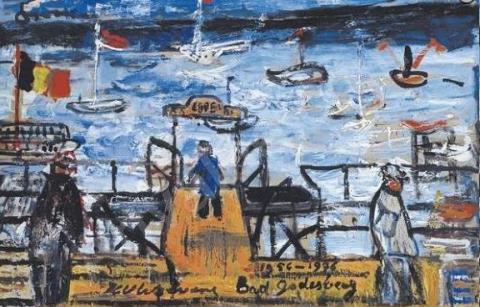

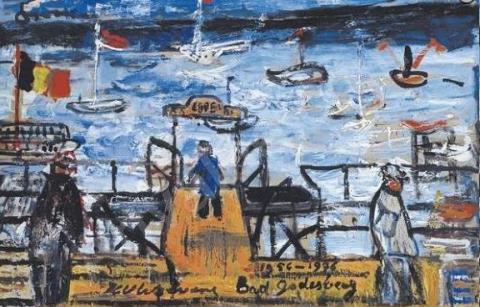

Bad Godesberg

Henri-Victor Wolvens

1896 - 1977

_______________________

Could Be Verse

Ben Lerner finds hope in the dislike of poetry

Meghan O'rourke

bookforum

(....)

What does Lerner mean, though, by the hatred of poetry? He begins by invoking Marianne Moore’s “Poetry,” which—in the version he quotes—reads in full:

I, too, dislike it.

Reading it, however, with a perfect

contempt for it, one discovers in

it, after all, a place for the genuine.

Lerner is fascinated by the question of why people dislike poetry—and most important, why poets dislike potery. A wry, highly self-conscious guide, he lures us in by sharing with the reader that, at events, when he or another poet is introduced, the words I, too, dislike it run through his head. When he is teaching or discussing poetry, the phrase sometimes takes on “the feel of negative rumination and sometimes a kind of manic, mantric affirmation, as close as I get to unceasing prayer.” It’s sort of crazy, he acknowledges—yet interesting: “What kind of art assumes the dislike of its audience and what kind of artist aligns herself with that dislike, even encourages it? An art hated from without and within.”

Lerner does talk in this book about the dislike ordinary readers have for poetry, which he attributes to an identification of poetry with one’s inner selfhood (not entirely jokingly, he cites the childhood rhyme “You’re a poet / and you don’t even know it”). Later, alienated from this source of value, adults denounce poetry in what he sees as an elaborate “reaction formation.” Lerner could more satisfyingly say much more here than he does—about the role of American anti-intellectualism, for instance, or about the historical specificity of current readers’ dislike, having to do with the rise of modernism and the “difficulty” of some contemporary poetry—but the book’s real focus is on why poets hate poetry.

...(more)

Ben Lerner, The Hatred of Poetry

via the page

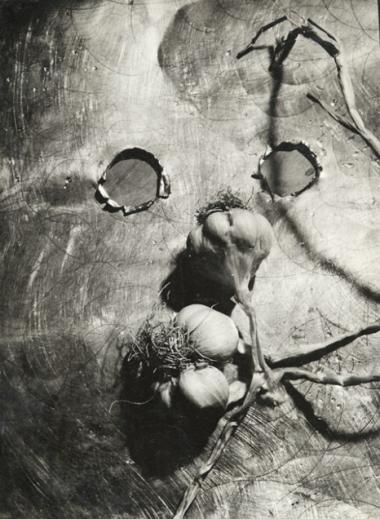

Wols

Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze

1913 -1951

_______________________

from

The Pact of Spring

Edmond Jabès

translated by Keith Waldrop

Words have worked their

way into mineshafts but have

lost my voice Silence capsized

inkwell The pen is the derelict

My two suns full-formed rivers

The sea is above the trees

Memory of leaves the hours

fête their flowers Sleep is

transparent fruit Night is

culled from the branches Tomorrow

has no shadow Our legend is

secret So wastes away

the dawn when canceled words

speak to those who never spoke

elect nothingness a bloodstain

Crumpled page pallid hand

clenched Leavetaking is limitless

The universe lives off oblivion stages

of stars Man and nature

share in kind and in kin

Thirst is of the earth Soft sheltering

flesh the very stones are

dreams To a hundred other evidences

the crystalline support of springs stolen

faces We no longer know where

we are to where we radiate

(....)

From the Book to the Book: An Edmond Jabès Reader

Translated by Rosmarie Waldrop google books

_______________________

Wols

_______________________

How philosophy came to disdain the wisdom of oral cultures

Justin E H Smith

aeon

... For the vast majority of the time that human beings have been on Earth, words have had no worldly reality other than the sound made when they are spoken.

(....)

The Italian philosopher of history Giambattista Vico wrote in his Scienza Nuova (1725): ‘the order of ideas must follow the order of institutions’. This order was, namely: ‘First the woods, then cultivated fields and huts, next little houses and villages, thence cities, finally academies and philosophers.’ It is implicit for Vico that the philosophers in these academies are not illiterate. The order of ideas is the order of the emergence of the technology of writing.

Within academic philosophy today, there is significant concern arising from how to make philosophy more ‘inclusive’, but no interest at all in questioning Vico’s order, in going back and recuperating what forms of thought might have been left behind in the woods and fields.

...(more)

_______________________

Wols

_______________________

Christophe Lamiot Enos: Postface to “Un Champ sur Mars / A Field on Mars”

(just published)

Jerome Rothenberg

(....)

Besides what may be drawn from years upon years of poetry writing, i.e. attentiveness to poetry and beyond it, toward what constitutes poetry and acts it out, I want to stress Rothenberg’s A Field On Mars as a proposition in elation. To Rothenberg, poetry is elation. It enthuses us. It is our heritage. It is a heritage in elation. Beyond what may be drawn from years upon years of poetry writing, there are at least two good reasons for elation in poetry, for elation as poetry writing. The first reason is to be able to still write more—write beyond what has already been achieved, rename once more time what has already been named. Writing as never-ending. Writing without an end to writing. Writing from generation to generation. Writing as a process forward. Writing as a way to circumvent death. As it is the meaning of one’s inheritance. As it is comprised already within the heritage. Within poetry as heritage. The second reason for being elated by and reaching elation through poetry, has to do with a special letting go of etiquette and conventions. Beyond attentiveness to poetry, Rothenberg’s A Field On Mars is a proposition in poetry as elation, as humor brings us elation. Poetry is our heritage. Not a thing here, nor a thing there. Not just a fish from out of waters. But the desire and care for making things, not this one or that one—but many, many things, a whole procession of things. Not just a fish out of waters, but the ways in which fish may be landed, i.e. ways to fish and enthusiasm for what has to be done for one’s sustenance. Enthusiasm for the way there is more than one fish in the sea. One fish, two fish. Red fish, blue fish. And another. And yet another. There is something of a classic in kid’s literature in Rothenberg’s. There is also a letting go of conventions. Here comes to mind again the very special way in which endings of certain lines go along with possible substitutes in Rothenberg’s A Field On Mars. You would think that a given line wants a specific ending. You would think that it matters that such or such a line ends with this particular ending—not any other. Well, Rothenberg makes you reconsider this assumption. A Field On Mars makes you reconsider it so much, that to a certain extent words become interchangeable. Which is a way of underlining what matters most in words: Their being with us, whatever they are, their being used and re-used, again and again. Words in our hands, words as gestures. As a result of this reconsidering of words, precise lexical meanings as collected in dictionaries fade in importance, as compared to the presence of words in our activities, in our daily routines and actions. Isn’t it elation for us?

A field on Mars: an expanse of grass, from the most improbable of places; soil to be tilled, on a planet that does not look like very welcoming to man, or to life in general. “A field on Mars” sounds pretty idealistic. Seems to be very far-fetched, indeed. Could poetry be a field on Mars? Could it finally be that, after years and years of practice and thought, exposition to poetry and striving toward it, poetry equal some expanse of grass from the most improbable of places? What wisdom is there to be derived from such an equation?

Reader, if you’ve not read the work itself, yet, you may at first sight have construed its title as stressing the ever-growing rarity of poetry within our world, or in our societies—how man decides to organize this world, or most men, apparently. Within such a context, poetry does appear as a rarity. Yet, such an interpretation does not give credit to the full range of Rothenberg’s meaning. A field on Mars, OK. Poetry as a field on Mars: OK. Yet the meaning of poetry as elation in Rothenberg’s A Field on Mars is that an expanse of grass may grow from it on the barest, most inhospitable of planets. Poetry as elation: despite dire circumstances, there is still hope, through heritage, through poetry, through the enthusiasm that poetry’s task is to convey. Rothenberg does not think about poetry as anything else but a heritage. A poem: a heritage. To write a poem: to inherit. To deal in harvesting: To deal in inheriting. To deal in tradition. To deal in forwarding. What is it that we want to forward our children? This or that? No. What we want to hand over is this handing over, precisely. This is the significance of poetry. This is one of the main teachings of ethnopoetics. With Shaking the Pumpkin, Rothenberg states or re-states the following: We want to forward dynamics, we want to bestow energies, enthusiasm and elation. Poetry as elation.

...(more)

_______________________

Wols

_______________________

cold morning

Nietzsche And The Burbs

This is it, the cold morning, the hangover of history. Yes, this is how things are. We can see clearly at last. We’re without illusions. We know what the world is.

We reduced the world to our measure. To that in which we could believe – which is to say, nothing. To the measure of our belief – which is to say, nothing.

(....)

This is our world. The cold morning. The hangover of history. This is our world. It’s disenchanted. It isn’t full of ghosts and ghoulies. This is our world. Grey dawn. Calm and clear. We understand it all. We’ve watched the documentaries. We follow the news. We listen to Radio 4. This is our world. We know what life’s all about. We know we must get on with our lives. We know that life’s what you make it. We know that life’s not always fair, but that life must go on.

...(more)

Heinrich Nauen

b. June 1, 1880

_______________________

Looking Across the Fields and Watching the Birds Fly

Wallace Stevens

Among the more irritating minor ideas

Of Mr. Homburg during his visits home

To Concord, at the edge of things, was this:

To think away the grass, the trees, the clouds,

Not to transform them into other things,

Is only what the sun does every day,

Until we say to ourselves that there may be

A pensive nature, a mechanical

And slightly detestable operandum, free

From man's ghost, larger and yet a little like,

Without his literature and without his gods . . .

No doubt we live beyond ourselves in air,

In an element that does not do for us,

so well, that which we do for ourselves, too big,

A thing not planned for imagery or belief,

Not one of the masculine myths we used to make,

A transparency through which the swallow weaves,

Without any form or any sense of form,

What we know in what we see, what we feel in what

We hear, what we are, beyond mystic disputation,

In the tumult of integrations out of the sky,

And what we think, a breathing like the wind,

A moving part of a motion, a discovery

Part of a discovery, a change part of a change,

A sharing of color and being part of it.

The afternoon is visibly a source,

Too wide, too irised, to be more than calm,

Too much like thinking to be less than thought,

Obscurest parent, obscurest patriarch,

A daily majesty of meditation,

That comes and goes in silences of its own.

We think, then as the sun shines or does not.

We think as wind skitters on a pond in a field

Or we put mantles on our words because

The same wind, rising and rising, makes a sound

Like the last muting of winter as it ends.

A new scholar replacing an older one reflects

A moment on this fantasia. He seeks

For a human that can be accounted for.

The spirit comes from the body of the world,

Or so Mr. Homburg thought: the body of a world

Whose blunt laws make an affectation of mind,

The mannerism of nature caught in a glass

And there become a spirit's mannerism,

A glass aswarm with things going as far as they can.

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Wittgenstein’s Handles

Christopher Benfey

(....)

To details like the door-handles, in particular, Wittgenstein accorded what Monk calls “an almost fanatical exactitude,” driving locksmiths and engineers to tears as they sought to meet his seemingly impossible standards. The unpainted tubular door-handle that Wittgenstein designed for Gretl’s house remains the prototype for all such door-handles, still popular in the twenty-first century. (Thomas Bernhard was surely evoking his idol, Wittgenstein, when he told a friend that the only way to find an exact replacement for a broken window-handle would be to find another, identical broken window-handle.)

Monk argues, more than once, that this design project brought Wittgenstein “back” to philosophy. Viennese society is central for Monk, who reproduces Klimt’s portrait of Gretl, and notes that she introduced her brother to an influential professor of philosophy at the University of Vienna. “Through working for Gretl,” he writes, “Wittgenstein was brought back into Viennese society and, eventually, back into philosophy.”

But I doubt that the return to philosophy was prompted by social connections, which were always a mixed bag for the antisocial Wittgenstein. I prefer to believe that the prompt was in the handle. For when Wittgenstein returned to philosophy, the idea that drove him beyond all others was that the nature of language had been misunderstood by philosophers, “including,” he noted winningly, “the author of the Tractatus.” Words did not, he had come to believe, primarily provide a picture of life (the word “snake” representing, or sounding like, an actual snake); they were better conceived of as a part of the activity of life. As such, they were more like tools. (We do things with words, as J. L. Austin famously argued, things like, from a list of Wittgenstein’s, “thanking, cursing, greeting, praying.”) “Think of the tools in a tool-box,” Wittgenstein wrote in his epochal Philosophical Investigations (1953). “There is a hammer, pliers, a saw, a screw-driver, a rule, a glue-pot, glue, nails and screws.—The functions of words are as diverse as the functions of these objects.” Words may look similar, especially when we see them in print. “Especially when we are doing philosophy!”

The analogy Wittgenstein drew was precisely with handles.

It is like looking into the cabin of a locomotive. We see handles all looking more or less alike. (Naturally, since they are all supposed to be handled.) But one is the handle of a crank which can be moved continuously (it regulates the opening of a valve); another is the handle of a switch, which has only two effective positions, it is either off or on; a third is the handle of a brake-lever, the harder one pulls on it, the harder it brakes; a fourth, the handle of a pump: it has an effect only so long as it is moved to and fro.

It is the utility of handles that Wittgenstein insists on here. The pump don’t work ’cause the vandals took the handles.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Zahavi, Dennett, and the End of Being

r s bakker

by rsbakker

(....)

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that phenomenology is religious, only that it shares this dialectical feature with religious discourses. The phenomenological attitude, like the evangelical attitude, requires what might be called a ‘buy in moment.’ The only way to truly ‘get it’ is to believe. The only way to believe is to open your heart to Husserl, or Heidegger, or in this case, Zahavi. “Killing the straw man” is jam packed with such inducements, elegant thumbnail recapitulations of various phenomenological interpretations made by various phenomenological giants over the years. All of these recapitulations beg the question against Dennett, obviously so, but they’re not dialectically toothless or merely rhetorical for it. By giving us examples of phenomenological understanding, Zahavi is demonstrating possibilities belonging to a different way of looking at the world, laying bare the very structure that organizes phenomenology into genuinely critical, consensus driven discourse.

The structure that phenomenology best explains. For anyone who has spent long rainy afternoons pouring through the phenomenological canon, alternately amused and amazed by this or that interpretation of lived life, the notion that phenomenology is ‘mere bunk’ can only sound like ignorance. If the structures revealed by the phenomenological attitude aren’t ontological, then what else could they be?

This is what I propose to show: a radically different way of conceiving the ‘structures’ that motivate phenomenology. I happen to be the global eliminativist that Zahavi mistakenly accuses Dennett of being, and I also happen to have a fairly intimate understanding of the phenomenological attitude. I came by my eliminativism in the course of discovering an entirely new way to describe the structures revealed by the phenomenological attitude. The Transcendental Interpretation is no longer the only game in town.

(....)

My advice? Jump ship before the real neuroinformatic deluge comes. We live in a society morphing faster and more profoundly every year. There is much more pressing work to be done, especially when it comes to theorizing our everydayness in more epistemically humble and empirically responsive manner. We lack names for what we are, in part because we have been wasting breath on terms that merely name our confusion.

...(more)

_______________________

Bridging Distances: Three Hispanic Canadian Authors

María José Giménez

(....)

According to critic, writer, and translator Hugh Hazelton,[1] Hispanic Canadian literature has occupied a significant position within this landscape for many decades, with a marked increase since the turn of the millennium. It is the subject of growing interest from readers, academics, critics, and publishers, as well as increased translation and publishing funding opportunities and awards for works translated from other languages into English and French—rather limited compared to what’s available for works translated between the official languages. Literary exchanges and collaborations with Mexico and other Spanish-speaking countries are on the rise, especially when it comes to the diffusion of Canadian literature and theater abroad.

Yet writing by authors of Latin American descent living in Canada is seldom read, taught, or reviewed beyond the country’s borders. Mention “Hispanic Canadian literature” or “Latino-Canadian literature” in the United States and you will likely, at best, pique your interlocutors’ interest; at worst, you may receive puzzled or even blank looks. ...(more)

_______________________

Words without Borders June 2016

.....................................................

The Flowers of War

Alejandro Saravia

Translated from Spanish by María José Giménez

the flowers of war

open at night

on boulevard Saint-Laurent

a line from Lorca

a word from Castellanos

a body unharmed by the siege of Sarajevo

a bomb that didn’t explode in Hanoi or Baghdad

and the sweet lips of women in winter

are enough to make dawn bear fruit

on this corner on boulevard Saint-Laurent

best if you don’t know who you are

best if you don’t know where you’re from

best if you don’t know where you’re going

the boulevard’s flowers in the night

will give you all the faces

all the gestures

to read every absence

to be every wound and every miracle

_______________________

late light

lilac and honeysuckle

photo - mw

_______________________

The Prescriptivist's Progress

Ryan Ruby

3quarks daily

"With a prescriptivist for a white knight, meaning hardly needs a dragon."

|