|

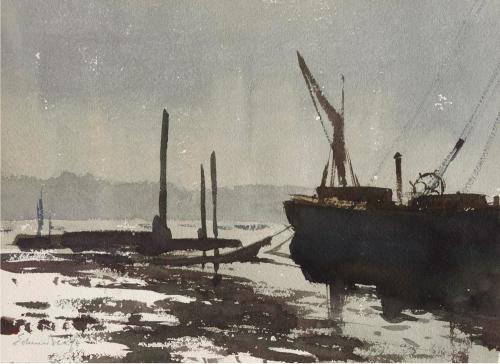

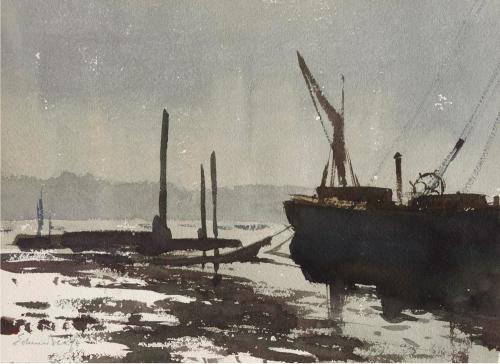

Edward Seago

b. March 31, 1910

_______________________

from ‘Due North’

Peter Riley

fortnightly review

(....)

Silence folded against the flank as the sky is folded

tight behind the morning fogs and closed shops

and there is no refuge to be had across the great

housing estates, sleeping citizens of eternity.

The long awaited silence, light through paper

dissolving the shadows filling the absences and

every step taken is an act of wish every

thought a prize, hovering names of loved ones.

Gentle pulsing of tremolo technique in a pavan

for viol, by Daniel Farrant (†1651) a blood-flow sense,

smoothing the furrows of habit and picking up

roadside attachments, emerging families of the far plains.

A failure, a silence, close to the heart,

a writing on the silence saying “too late”

as if we had a nation with us, as if we could speak!

Poets of the closed cupboard, this is my Rubaiyat.

(....)

Bronze heads wrapped in red textiles, buried in dry earth.

Walk on. Speak to yourself. Walk through a war if you can,

everything you remember lost and broken behind you, humming

a simple tune you can’t stop repeating, immortal invincible.

Bronze head, lips slightly parted, staring straight ahead

a soundless singing. This is where we stop, in the ancestral chapel

the parental double grave. Be quiet, say nothing, follow the argument

of the music, monothematic, drawing together, “a marriage of true minds”.

(....)

Singing across all the anxieties that return during the night,

between dark and light, sleep and waking, truth and invention

bearing the infant in mind, the bronze heads breathing song:

pastoral song panic song choral preludes measures of fate.

...(more)

Peter Riley at Shearsman Books and Poetry International

_______________________

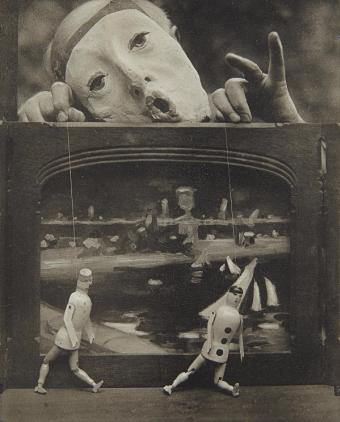

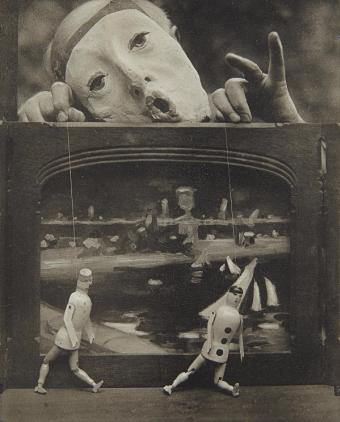

The Play of Life (Self-portrait)

circa 1930

Pierre Dubreuil

1872 - 1944

Pierre Dubreuil

A complete set of the artist's known diapositives,

1901-1930

_______________________

Cory Doctorow, Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free

reviewed by McKenzie Wark

la review of books

(....)

Doctorow’s creative credentials are in order, then, and in his new nonfiction book Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free he has produced an essential primer for artists seeking to navigate the shark-infested waters of today’s media. It contains a good deal of very good advice for creators about how to figure out what is in their best interests. But Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free is more than a how-to book, or a Creators’ Rights for Dummies: it also provides the elements for a class-based theory of creative production in the 21st century. (....)

Doctorow is no techno-utopian, but he does have a political or ethical lodestar that orients his work: “Anything that minimizes the drag on our collective efforts should be celebrated.” There are tools out there now, he tells us, that can support our common life. As he puts it: “Information doesn’t want to be free, people do.”

If you are inclined to think, as I am, that we are all cyborgs — perplexing mixes of flesh and tech — it might not be possible to divide “information” and “people” so cleanly. Once information started to be produced as something relatively autonomous from the material substrate that sustained it, it really does appear to have some agency. It seems to “want” to be shared like a gift. As I put it in a different riff on the same meme: information wants to be free but is everywhere in chains. It keeps getting stuffed back into the narrow confines of rather old-fashioned models of absolute private property.

...(more)

_______________________

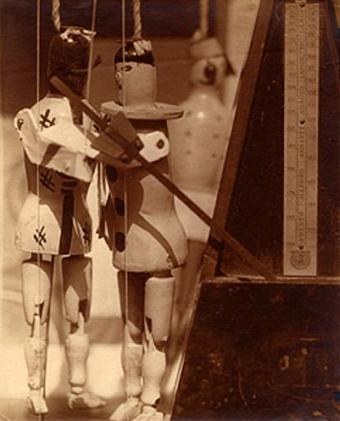

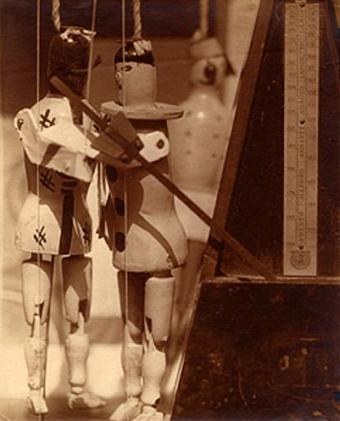

Le Metronome

Pierre Dubreuil

c. 1920

_______________________

Excerpts from Due North

Peter Riley

Intercapillary Space

from Part IV

(....)

Smoke standing over the houses in the valley below

we tempered ourselves into an ecstasy of forgetting

and farmed ourselves into the next generation

and rolled down the hillsides to the town

to set up shops, and ache with servility when the man

calls in to take away the profit. Consolation starts to slide

into counsel, tragedy into accident.

And where there was a local consolidation is now

a subsidised circus. Our old romances return

freshly laundered on the backs of migrant workers

from former colonies and recent war zones.

(....)

from Part V

So the final descent into madness and death

is down a Pennine hillside, leaping small streams hung

with elder and hawthorn chest pain image pain stumbling

over tufted meadows down cinder tracks, vetch,

ragged robin, cow-parsley, dandelion, speeding

between hedgerows into the edges of the town the

garden fences the meeting places the towers, then

to slow and stagger panting and fall silently

across the threshold of the public library in all the gladness and relief

of total incomprehension.

...(more)

_______________________

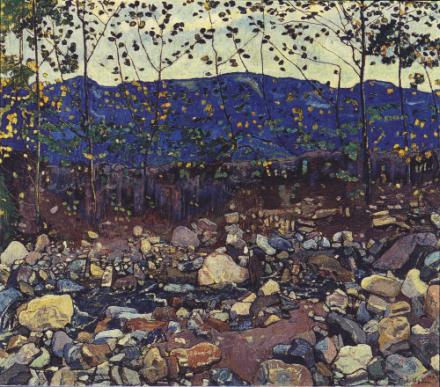

Edward Seago

Landscape at Kyleakin

c. 1958 - 1960

Anne Redpath

(1895–1965)

_______________________

Strange Objects

Graham Harman

posted at rediposture

(....)

“Whereas real objects taunt us with endless withdrawal, intentional objects (Husserl) are always already present. If the real tree is never present enough, the intentional tree is always excessively present, its essence accompanied by the noisy peripheral detail that eidetic variation needs to strip away; intentional objects are merely weighed down with trains of sycophantic qualities, covering them like cosmetics and jewels. Though Husserl brackets the world in order to focus on an immanent eld of consciousness, the ego is not entirely master in this immanent realm. Cats and lampposts resist our first approach, demanding patient labors if their essence is to be gradually approached. It is the very principle of phenomenological description, whose eidetic reductions never quite grasp the essence of the thing, which differs from Lovecraft only in its usual avoidance of the theme of existential threat. In both cases, the known link between objects and their properties partially dissolves.”

...(more)

_______________________

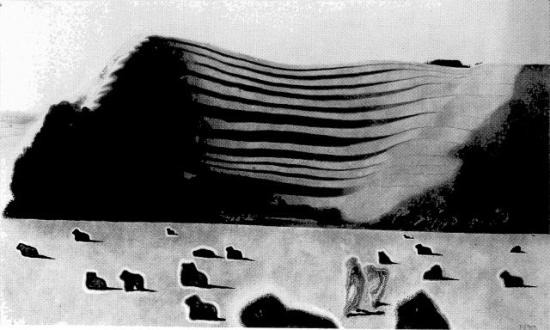

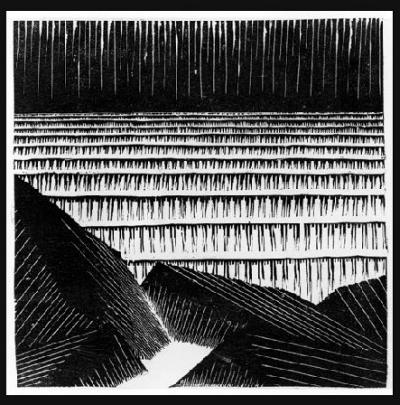

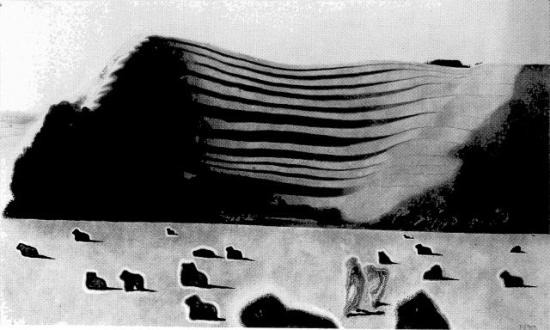

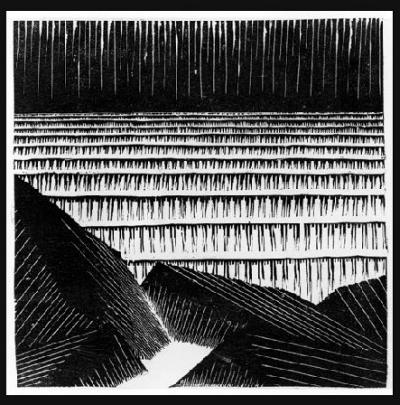

Valley and River

Northumberland

1972

Edward Burra

b. March 29, 1905

_______________________

César Vallejo on Art and the Social Sphere, Charlie Chaplin . . .

translated by Joseph Mulligan

lana turner

The Work of Art and the Social Sphere

Let’s look at a few examples. Nietzsche was a physically weak, sickly man. Is one to deduce from this that The Birth of Tragedy is the wincing of a wasted loser? Tolstoy never had financial burdens. He didn’t know what it means to put bread on the table by working. He lived the life of a petite bourgeois man or, rather, a feudal lord. Is one to deduce from this that Resurrection is a feudalizing work? Mallarmé lived in perpetual political abstention, neural to the ebb and flow of parliaments, absent at elections, assemblies, and political party gatherings. Is one to deduce from this that The Afternoon of the Faun is devoid of political spirit and social meaning? Of course not. Such conclusions are reached only by run-of-the-mill, empirical critics. Akin to a poor photographer who seeks in photography the formal reproduction and external imitation of the original, the poor critic scours the work of art to find the literal reproduction and reflection of repetition in the artist’s life. When he does not find that reflection—which, let us add, occurs precisely with the great artists—he concludes by saying that there is no synchronism in the life of the author and his work. This is how people proceed who believe that concordance exists in some but not all artistic objects.

To find truly profound aesthetic synchronism, one must bear in mind that the phenomenon of artistic production, as Millet says, is an authentic operation of alchemy, in the scientific sense of the word—a transmutation. The artist absorbs and concatenates the social unrest of the environment as well as his own individual unrest, not to return it exactly as he absorbed it (which is what the poor critic would want and what occurs with inferior artists), but rather to transform it within his spirit into other essences, distinct in form and identical at the core, into the raw materials as absorbed. At first sight, as we said, one might not recognize the vital raw material as absorbed in the structure and emotional movement of the work, just as at a glance one might not recognize in a tree the nutritional chemical bodies extracted from the soil. However, if one analyzes the work in depth, one will necessarily discover—in its innermost viscera and through the personal peripeteia of the artist’s life—not only the circulating currents of socioeconomic character, but the mental and religious currents of its epoch. An alchemical analysis of a vegetal substance would likewise establish a similar biological phenomenon in the tree.

The correlation between the individual and social life of the artist and his work is therefore constant. It operates consciously or subconsciously, whether the artist wants it to or not, no matter if he accepts or denies it, and even if he tries to escape it. The challenge for the critic—we repeat—is knowing how to discover it.

...(more)

_______________________

Under The Hill

Edward Burra

1964-5

_______________________

3 Poems from Trilce

César Vallejo

(translated by Joseph Mulligan,

courtesy of Wesleyan University Press)

lana turner

XVIII

Oh the four walls of the cell.

Ah the four whitening walls

that irrefutably face the same number.

Breading ground of nerves, evil breach,

through its four corners how it snaps

apart daily shackled extremities.

Loving keeper of innumerable keys,

if you were here, if you could see

unto what hour these walls are four.

Against them we’d be with you, just the two,

more two than ever. And you wouldn’t even cry,

speak, liberator!

Ah the four walls of the cell.

Meanwhile as for those that hurt me, most

the two lengthy ones that tonight

have something of mothers who now

deceased each lead through bromined slides,

a child by the hand.

And only will I keep my hold,

with my right hand, that makes do for both,

upraised, in search of a tertiary arm

that must pupilate, between my where and when,

this stunted adulthood of man. ...(more)

_______________________

Cliffside, Portugal

Anne Redpath

_______________________

Highlighting Western Victims While Ignoring Victims of Western Violence

Glenn Greenwald

(....)

You’ll almost never hear any of those victims’ names on CNN, NPR, or most other large U.S. media outlets. No famous American TV correspondents will be sent to the places where those people have their lives ended by the bombs of the U.S. and its allies. At most, you’ll hear small, clinical news stories briefly and coldly describing what happened — usually accompanied by a justifying claim from U.S. officials, uncritically conveyed, about why the bombing was noble — but, even in those rare cases where such attacks are covered at all, everything will be avoided that would cause you to have any visceral or emotional connection to the victims. You’ll never know anything about them — not even their names, let alone hear about their extinguished life aspirations or hear from their grieving survivors — and will therefore have no ability to feel anything for them. As a result, their existence will barely register.

That’s by design. It’s because U.S. media outlets love to dramatize and endlessly highlight Western victims of violence, while rendering almost completely invisible the victims of their own side’s violence.

(....)

... whatever else is true, if we are constantly bombarded with images and stories and dramatic narratives highlighting our own side’s victims, while the victims of our side’s violence are rendered invisible, it’s only natural that large numbers of us will conclude that only They, but not We, are committing civilian-killing violence. That’s a really pleasing thing to believe, no matter how false it is. Having media outlets perpetrate self-pleasing and tribal-affirming — but utterly false — narratives is the very definition of propaganda. And that’s what largely drives Western media coverage of these terrorist attacks every time they occur in the West.

...(more)

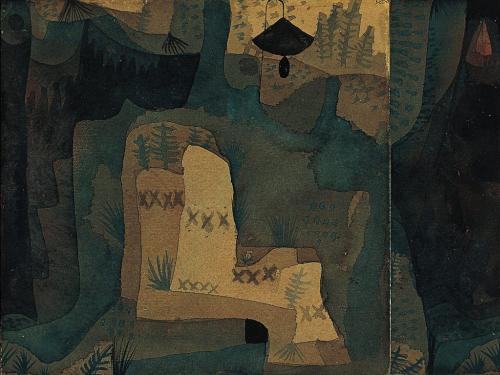

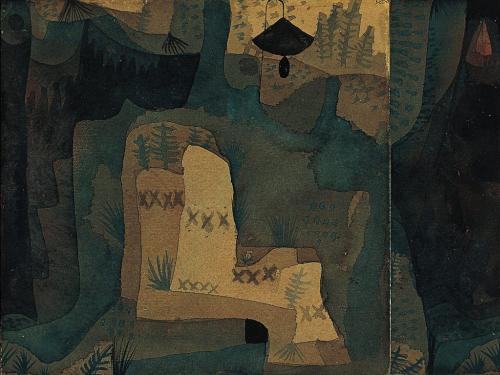

Black Bell in the Forest

Paul Klee

1923

via Arsvitaest

_______________________

A Translation of "Ebene," a Short Story or Fragment by Thomas Bernhard

Translation by Douglas Robertson

Lowlands

If we had ever been informed of and thereby enlightened in a tremendous fashion about the fact that our life-process is in truth nothing but a process of illness—we say to ourselves and ask ourselves, what, or rather, who has not informed us of it and not enlightened us about it to any extent whatsoever, time and again and specifically with the same allegations against our parents as well as against our entire environment, in which we, as we now see, were compelled to exist for decades without ever actually seeing and hence for decades without ever actually thinking; above all, we ask ourselves why our parents never informed us and therefore enlightened us, when it was after all their duty, as we now believe, as we are well within our rights to do, to inform us and enlighten us and, as we know full well, above all regarding the fact that our life-process is nothing but a process of illness and consequently has always been nothing but a process of illness, a fact that is immediately recognizable as a fact of nature—we would in those informed and enlightened circumstances have relinquished everything and abandoned everything much earlier and in point of fact would have left behind everything for ever; many decades ago we would have been gone—and gone under—and also have let ourselves go—we would have gone under and would have relinquished and abandoned and left behind and extinguished everything. ...(more)

_______________________

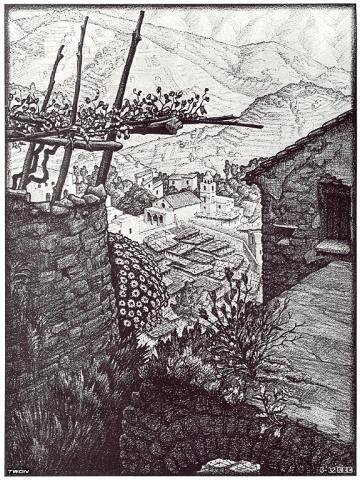

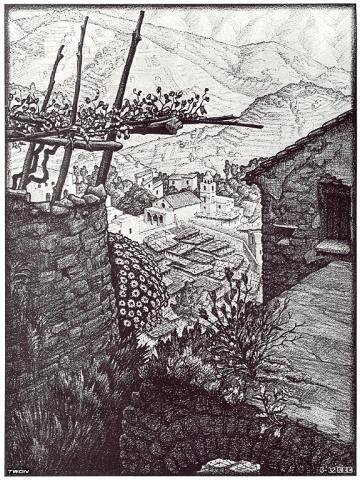

Turello

1932

M. C. Escher

d. March 27, 1972

_______________________

An American Suite – Pierre Joris

review by Connor Stratton

full-stop

(....)

When at its best, the collection’s calendar frame is not just a gimmick to let Joris’ other formal moves run wild. It is meaningful, too, and the elephant in the book, “Metasemiologies,” proves revealing. This piece — structured more as a numbered set of philosophical claims — is a working-through of various structuralist and poststructuralist voices. It begins: “1. The object of semiology is the study of the life of signs at the heart of the social life.” And the ‘day’ is an important sign to Joris. A day is central to the “heart of social life”: it signifies and organizes a unit of time that humans have decided is important. A ‘date,’ furthermore, systemizes the ‘day’ into a unit of time that then fits within a conception of history. Today’s date, then, can be mapped on the same calendar as a date 4,000 years ago, or yesterday, or whenever.

Perhaps, then, Joris asks, “What’s on a day?” And, in doing so, he destabilizes our claims for both “dating” time and for poetry’s timelessness. In “Metasemiologies,” he concludes that, “Language… belongs to a description that is neither transcendental nor anthropological.” Time escapes calendar’s straightjacket; poetry escapes too, but cannot escape time. Still, An American Suite is a bold attempt to think of some “way out / of these calendric / interstices.”

...(more)

_______________________

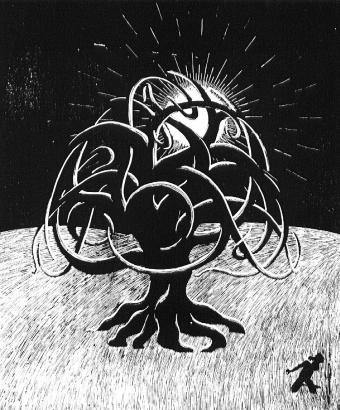

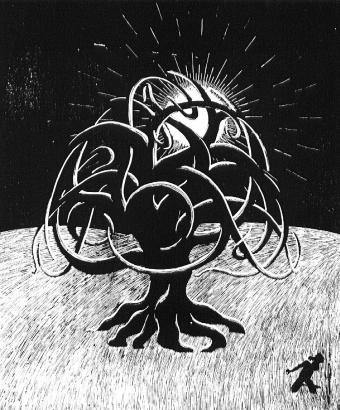

Twon Tree

M. C. Escher

1919

_______________________

Theses On The Philosophy Of The FKA-Anthropocene, Feat. Shia LaBeouf, Part II

Jonty Tiplady

public seminar

(....)

XI

In Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, Hélène Cixous writes, because the word “truth” exists, we may as well use it. One could say the same of the term “anthropocene.” It brackets itself, spawning its own toxicity rates and think-piece industrial complexes, timed out ahead of time, and yet like “god” or “truth” or “love,” it is now impossible to imagine language without it. In fact, where god, truth, and love are relatively constant as principles, the anthropocene, despite peak memeification and preemptive FKA-ing, can only intensify and be singularly historical as time goes on. It has to be on the anti-wane, because that is what it is. Aesthetic counter-formations develop against it, necessarily and dubiously, and yet a second-order counter-ploy is also possible: transform it through use or even over-use. Confront it. Poeticize it. Face it. Just do it. Just be it. Anything else might be a semiotic bypass, in the long run.

(....)

Following Benjamin, McKenzie Wark has consistently argued that there are worse things now than capitalism and that hyper-finance may simply be a symptom. The same could be said of social identity politics, whose own breakdown is in motion via the Internet as a new world order of self-feeding stasis. That Marx’s late more ecological writings have just been discovered pretty much equals Treppenwitz der Weltgeschichte (the staircase joke of world history). There is heat in the signscape now, more than a bout of mad symbolic pressure. Something is happening, and right at and not beyond individual accounting, it is happening to us, to all of us. It becomes less and more possible to know about whom or what one is speaking when there are some who seem to venture to exploit what is happening against others and for ends that are not always clear, while others try to protect themselves by pretending to be able to protect others against what is happening, which, since nobody necessarily knows what it is, may be counterproductive. Facebook timeline hypomnemata ally theatre comedy as old as the sun.

...(more)

Part I

_______________________

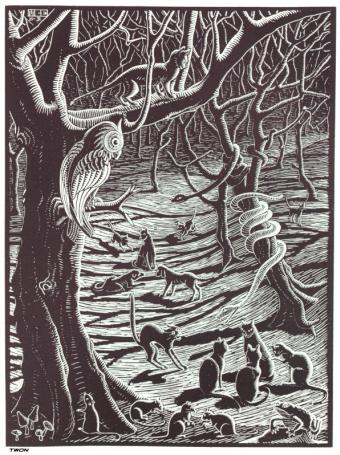

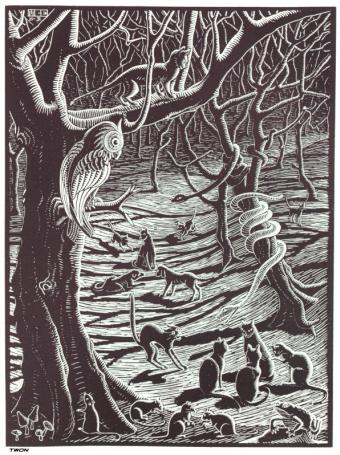

Scholastica

M. C. Escher

1931

_______________________

Can Ideas Withstand Shifts in Language?

The Future of Language: Considering the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis for translation, emoji, and pop culture

Elisa Gabbert

guernica

(....)

Everything is translatable, but nothing is perfectly translatable: tidy words become gangly phrases, the “Kafkaesque” becomes fantastical, innuendos appear or disappear, polysemy and rhyme seem to teleport to a new location in the poem. Meaning dissipates in the processing, decays over time, but it’s remarkable how much is retained, the way it’s remarkable how good the Lascaux cave paintings are (always I am struck: such good horses!). Problems in translation are not an argument against translation. The work can remain what it is while also being transposed, twisted, given new significance, like a band of paper taped into a Mobius strip, a glove turned inside out. ...(more)

_______________________

Blocks of Basalt along the Sea

M. C. Escher

1919

_______________________

The End Of Emo-Politics

Mark Fisher

(....)

The problem with what I would like to call here the therapeutic imaginary is not that it posits subjects as vulnerable, haunted by events in their past lives, and lacking in confidence. Most subjects in capitalism – including those in the ruling class – fit that description. The problem with the therapeutic imaginary – and this is a problem that goes back to Freud and the origins of psychoanalysis – is its claim that these issues can be solved by the individual subject working on him- or herself, with only the therapist to assist them.

(....)

As is well known, far from ignoring emotions, or assuming they could be bypassed in some way, Spinoza’s philosophy makes the management of emotions central to its project. It aims not to subdue emotions, but to engineer joy – a task that only be achieved when reason is not simply opposed to feelings, but brought to bear on them. According to Spinoza’s logic, ignoring emotions only mystifies them, putting them beyond the purview of rational enquiry. All of which makes Spinoza an eminently modern philosopher, but also a thinker whose work is an indispensable resource for any progressive project. This is especially so now, in an era in which more and more areas of life and the psyche dominated by agencies which engage in libidinal and emotional engineering – most of which is undertaken, knowingly or unknowingly, in the interests of capital.

(....)

... what we confront here is a kind of antinomy of the therapeutic imaginary: the idea that the proliferation of therapeutic orthodoxies simultaneously produces “softened” subjects – subjects who identify as lacking, if not actually damaged – and subjects that are “hardened” – subjects who pride themselves on a claimed invulnerability.

(....)

To break out of this impasse, we need to abandon the belief in the autonomous individual that has been at the heart, not only of neo-liberalism, but of the whole liberal tradition. In a successful attempt to break with social democratic and socialist collectivism, neoliberalism invested massive ideological effort into reflating this conception of the individual, with its supporting dramaturgy of choice and responsibility.

...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

Theses On The Philosophy Of The FKA-Anthropocene, Feat. Shia LaBeouf, Part I

Jonty Tiplady

Public Seminar

Walter Benjamin’s strategy in the Theses on the Philosophy of History was to focus on a non-human moment in human time and to present this instance on blast in his prose style. What I mean by “blast” here is the fact that the message had to be pirated past ideological hangers-on and historical barriers, past both Marxist and theotropic renditions, and also past the Nazi episode that might have been his more obvious target in 1940. His prose is clear but depth-charged, resonates at another frequency, still as if exploded past the imaginary proscriptions of Theodor Adorno, who was already in situ in New York as Benjamin tried to flee Paris. I try to rearbitrate this tab here, replicating violences of style and abbreviation. I run together logics and act as if Benjamin’s wavelength were not yet an infinitely weak signal.

(....)

What Benjamin calls “natural history” — our becoming-geological, marked now by the word “anthropocene” — is the central trans-historical judder here, a type of spread of stone, occlusive mnemonic instances, peak toxicity, white-slavery aporias, limited computation, comedown, group icons, global poison containers, all within a canopy that takes in the next drone war front in Somalia, and so on. Tom Cohen, the ideal receiver and completer of Benjamin’s text for my money, has mock-cajoled with deadly seriousness that Benjamin was perhaps choosing death “over the company of Adorno in New York” in 1940. Benjamin’s slightly crypted style, which then reveals itself in the open, acted not just to oppose Marxism and historicism, but also to close them out, to autocide them. I would argue that Benjamin’s essay also closed out in advance all current forms of leftist denialism around climate change, social identity politics as a form of forever legitimate anthropo-denialism, and hyper-evolved aesthetics as more of the same tropic defense arabesques.

This essay was gathered especially for Public Seminar, as a kind of experiment in hors-garde journalism. I follow McKenzie Wark in wanting to accelerate and reformulate the public debate around extinction logics and how they impact aesthetics, but also fail to predetermine what or who the public and private now might be. As Wark writes, with shattering simplicity, “one has to keep stating and restating certain bullet points even if in terms of how people think and feel they are besides the point.” One has to risk, I would echo, a type of monomania that won’t always aid online presence and profile, and yet which must go public and clear.

...(more)

_______________________

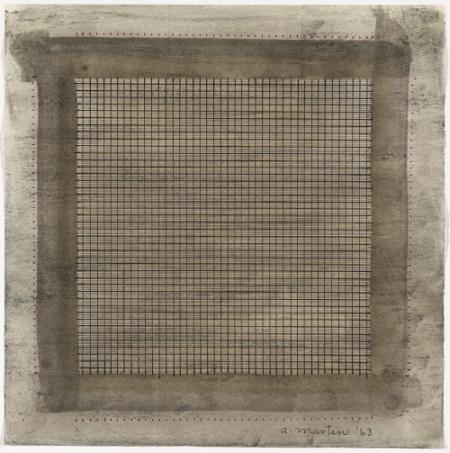

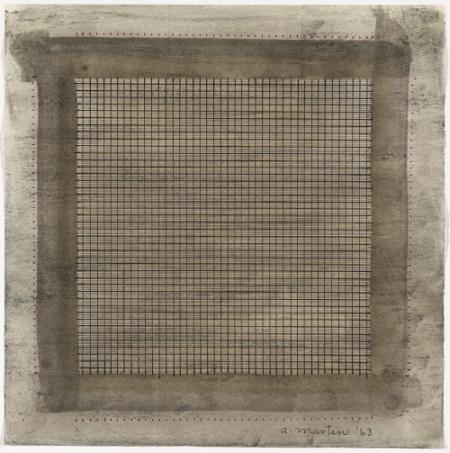

Agnes Martin

b. March 22, 1912

_______________________

The Impossibility of Innocence: On Architecture’s Intrinsic Exclusionary Violence

Léopold Lambert

the funamulist

(....)

To simplify this demonstration and to show that architecture does not need to be complex to become both applicable and operative, let’s return to where we started, with the example of a simple roof. Such an architectural organization of space is particularly effective to accommodate a ‘first come, first serve’ protocol, however architecture can become more complex to accommodate more drastic protocols of selection, like the ones mentioned above. As material assemblages, walls are largely constructed in such a way that their structural integrity cannot be affected by bodies without proper tools that are themselves subject to the protocol of private property, acceptability and access. Hence why an imprisoned body will not succeed in evading the walls that surround it, yet the buildings experienced by our bodies on a daily basis are not essentially different; one cannot simply cross walls to transgress the way space has been designed and bodies separated. The difference between our homes and prison cells can be found in the ability for a body to directly intervene into the walls’ porosity through architectural devices, such as doors and windows, to which the protocol of admission has been materialized in a small object called the key. Who owns the key is a body included as acceptable in the protocol of admission defined by both a legal regime (private property for instance), and a material one (the wall and its porosity regulator, the door).

In French, homeless bodies are called shelter-less (sans-abri). They are the bodies not included in any selective protocol that grants access to a shelter; they are key-less, and all walls are reminders of the outdoor prison from which they cannot escape. This notion of the ‘outdoor prison’ may sound exaggerated; after all, the exterior milieu of the shelter-less is what remains in the world after we have withdrawn the totality of the sheltered spaces from it. However, I would like to insist on the fact that this ‘remaining world’ does not constitute an untouched condition in which bodies would have the same status as one in which shelters had never been erected. In other words, shelter (and, by extension, architecture) does not only create the status of the selected and protected body; it also actively constructs the excluded and shelter-less one. There are two sides to each wall, regardless of which one may be covered by a roof and which one may not.

...(more)

_______________________

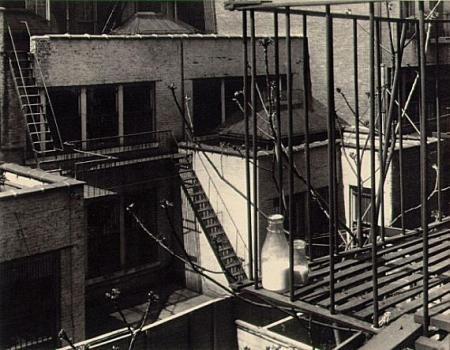

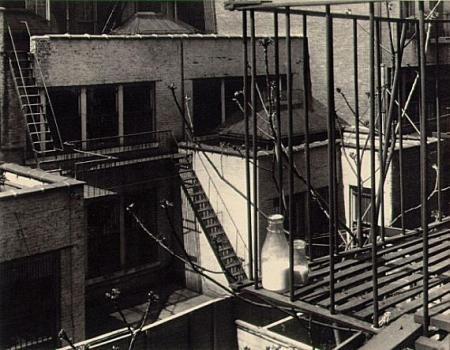

Milk Bottles

Spring New York

Edward Steichen

1915

_______________________

Kristeva, Stoicism, and the “True Life of Interpretations”

Kurt Lampe

substance

The repertory of theories, practices, and stories associated with Greek and Roman Stoicism fills a significant compartment in the Western philosophical archive, the meaning and value of which are ceaselessly reconfigured by each generation’s archivists. In the recent decades, it is not only specialists who have browsed, rearranged, and relabeled these shelves; following Foucault’s Hermeneutics of the Subject as well as a powerful synergy between Anglophone scholars and cognitive-behavioral therapists, there is now a wave of enthusiasm, inquiry, and experimentation. Into these vigorous currents I propose that we release yet another stream, namely the numerous commentaries on Stoicism in the psychoanalytic, literary, and broadly cultural criticism of Julia Kristeva.

My first objective in this article is to explain the scattered, elliptical,

but insightful and coherent remarks Kristeva threads throughout her

oeuvre. These remarks are difficult to understand, both because they

require familiarity with the audacious scholarship of Émile Bréhier and

Victor Goldschmidt, and because Kristeva eschews dispassionate clarity

in favor of affective involvement with the topics and situations on which

she writes. In other words, she performs her ethics of interpretation. “Interpretation” for Kristeva designates an ethico-epistemic attitude, and the “true life of interpretations” designates a personally and politically healthy form of this attitude. Working through these scholarly and methodological challenges is a good way to appreciate how the theme of “interpretation” can tie together her reflections on language, ethics, politics, theology, and metaphysics, all of which emerge in response to the Stoics’ renowned systematicity.

My second objective is to sketch a critical response to Kristeva’s presentation. The point is certainly not to praise or condemn her accuracy, but rather to develop a new perspective on the “existential option” that the Stoic life is, or—following Kristeva’s intervention—could be today. This perspective is an important complement to those on offer from Foucault and the mainstream Anglophone tradition.

...(more)

_______________________

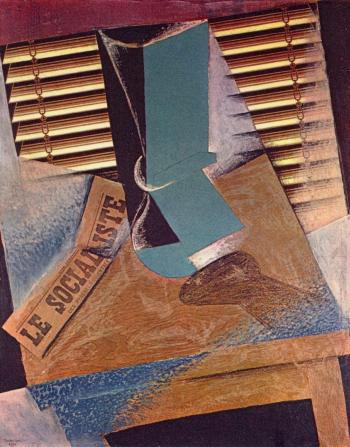

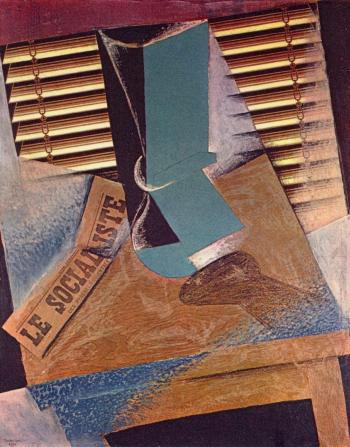

The Sunblind

1914

Juan Gris

b. March 23, 1887

_______________________

Paranoid Android

Matt Miles

dark mountain

(....)

What I take away from all this though, is not that machines are replacing human beings at doing work — this has been happening for a long time now — but rather that machines are replacing human beings at doing ‘human’ work, and maybe just replacing human beings entirely.

Even as machines are becoming more human, humans are becoming more scarily machine-like, in insidious ways. Were I to write this piece by hand today, I doubt that I or anyone else could read my handwriting, though, like riding a bike, I would at least remember how to form letters. But I wonder how long before children are no longer taught to write by hand in school.

Similarly, we can no longer remember phone numbers, conduct research at a physical library, or use a paper map, because it’s no longer required of us by our technologies. We are literally unable to find our way in the world any longer. A whole generation is reaching maturity for whom life without digital technologies would be unimaginable, because it’s the only one they’ve ever known.

As our consciousness is increasingly colonised by our technologies, our humanity — our human ways of being in the world and relating to other humans and animals alike — is one of the first things to suffer. As David Graeber has noted, the biggest medical breakthroughs of recent times are not cures for deadly threats like cancer, but rather anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications that make the increasingly inhuman demands of our technological society bearable to us.

...(more)

_______________________

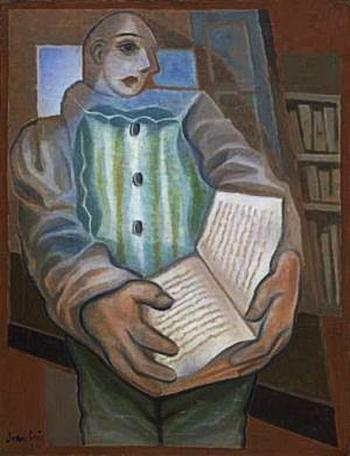

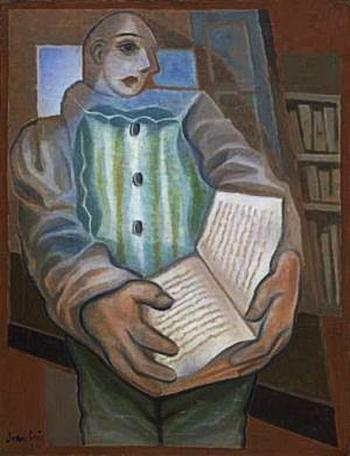

Pierrot with Book

Juan Gris

1924

Legends of Distant Past Days

1965

Hans Hofmann

b. March 21, 1880

_______________________

Erasing history

On Jordan Abel's 'The Place of Scraps'

Stan Mir

jaket2

When Jordan Abel began thinking about the book that became The Place of Scraps, published in 2013 by Vancouver-based Talonbooks, he thought he would write historical fiction. He wanted to find a way to work with the history of his Nisga’a Nation ancestors. The Nisga’a live in Western Canada and are known in part for displaying ancestral totem poles on their lands. Growing up, Abel felt that his ancestors’ stories weren’t available to him; he wasn’t even sure the stories had been preserved in any form until he came across Marius Barbeau’s Totem Poles in the University of Alberta library, where Abel was an undergraduate. But Abel didn’t end up writing historical fiction with the material he had gathered from Barbeau’s work; nor did he write in the two other genres, nonfiction or lyric poetry, that he also considered. He ended up writing a book of poetry, using erasure as the main mode of composition. His book is structured by sections that begin with images of totem poles, as well as passages from either Barbeau’s work or entries from Abel’s journal. Abel then erases portions of these excerpts for the duration of each section.

(....)

Given that erasure as a poetic technique has become more popular, it’s important to ask who is doing the erasing and why. Tom Phillips’s A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel seems to have had two main goals. One was to create an artwork, using painting, collage, and cut-up technique, out of a forgotten Victorian novel. He also wanted to create an oracle, in the tradition of the I-Ching. Although Phillips considers A Humument “an altered book,” a form of mixed-media artwork, it is often cited as a foundational erasure text. Ronald Johnson’s aim, in excising the first four books of John Milton’s Paradise Lost to produce the book Radi Os, was to “omit most of the text to create a Blakeian visual page and a new Orphic text of [his] own.” It’s worth noting that white men did two of the most famous books of erasure, one of a canonical book by a white author. Neither of those books erases works by authors of color. Their acts suggest a level of comfort with the boldness of erasure and with the canon. Abel’s erasure of Barbeau suggests a pronounced discomfort with the ways interpretations of indigenous cultures have been shaped by white viewpoints.

(....)

The Place of Scraps goes beyond discomfort. Its impetus involves anger, disappointment, and, importantly, an interest in reframing the discourses around First Nations culture. Abel has erased Barbeau’s text because he wants to understand who he is and who he comes from, including not just his ancestors, but also Barbeau and the myriad white settlers who have shaped his heritage. The mistake that some Conceptualists have made is thinking that any text can be erased by anyone and that sociopolitical concerns are outside the act of appropriation — and outside the text. Yet when an artist chooses a text to appropriate, whether through erasure or collage, there is more at stake. Abel’s work digs into and dismantles the problems his texts are meant to invoke.

...(more)

_______________________

The Third Hand

Hans Hofmann

1947

_______________________

Bowl Cut

SmirkPretty

It is all okay, just the way they say it is. By every measure, it is fine.

Rise weary. Shower off the animal, dress in unremarkable cloth. Speak in operation manual dialect. Meet only the eyes of the bus driver and snap straight the helicoid moment as you stride to claim your seat.

Write like a man, the librarian says. She scrubs her emails now. Each is an écorché peeled free of padding. Each correspondence a naked, muscled machine, its purpose laid bare.

Maybe we danced before.

Maybe we pretend we haven’t forgotten the petronella turn.

We collect pennies as paperless assurance. We eat, we mimic love. We wish we could un-know what keeps pressing in on the periphery, even when we lock tight the frame: that ice cream and sex and even the names we whisper in the dark are all bound by the law of diminishing returns.

For vague yet persistent unease, a prescription is available.

This is all there is. By every measure it is fine. This is complete. This is plenty. Our dissatisfaction with this is obstinance.

Another name for resistance.

...(more)

via Synthetic_zero_______________________

Profound Longing

Hans Hofmann

1965

_______________________

"How to live a life “unsponsored” by a deity, in which we are responsible for inventing our own meanings, was the great subject of Stevens’s poetry from beginning to end."

The Patron Saint of Inner Lives

Adam Kirsch atlantic

(....)

... His first book, Harmonium, published in 1923, established Stevens as the patron saint of the inner life held captive by the outer life—a peculiarly American condition. His daily existence offered no scope for self-expression, but on his walks to and from work, in the evenings up in his study, he was confronting the ultimate questions of art and life. How can humanity live without God? Can religion be replaced with another kind of myth? How does art reflect and transcend reality? And he was answering in a language at once voluptuous and intellectual, elegant and eccentric—a language such as no one had spoken before:

Chieftan Iffucan of Azcan in caftan

Of tan with henna hackles, halt!

Damned universal cock, as if the sun

Was blackamoor to bear your blazing tail.

Fat! Fat! Fat! I am the personal.

Your world is you. I am my world.

These lines, from “Bantams in Pine-Woods,” represent Stevens at his most antic—the faux-exotic names and nonsense syllables, the fine excess of assonance in the opening lines. This is the poet who fills his verses with sound effects like Tum-ti-tum and hoo-hoo-hoo, who revels in recherché words like silentious and pendentives. His is a ponderous kind of humor—exactly the kind of self-delighting language that would be invented by a man who had no one to talk to but himself. The critic Randall Jarrell was right to compare Stevens to “that rational, magnanimous, voluminous animal, the elephant.” But he is a dancing elephant.

At the same time, even in “Bantams,” it’s possible to see that Stevens’s language is not surreal or free-associative, but rather the embroidered garment of a serious theme. The poem’s rooster, which Stevens compares to a proud chieftain, comes to represent the sovereign ego. The interdependence of the world and the self, and the way the self creates the world it experiences, were matters that Stevens never tired of revolving in his work. A product of the Harvard of the late 1890s, where philosophical debates about idealism and realism were inexhaustible, Stevens carried into the 20th century some of the spiritual burdens of the 19th.

Above all, for him the death of God was not an abstraction or a truism, but a perpetual challenge, whose implications for art and ethics he never ceased to think about. ...(more)

_______________________

In the Vastness of Sorrowful Thoughts

Hans Hofmann

1963

_______________________

Object-Oriented Ontology’s Endless Ethics.

A review of Ian Bogost, Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing

Cristin Ellis

postmodern culture

It is reported that, while out on a stroll with friends one day, the Transcendentalist Elizabeth Peabody walked into a tree limb. Picking herself up, she explained to her concerned companions, “I saw it, but I did not realize it.” This story’s appeal lies in its succinct, slapstick debunking of Transcendentalist claims to omniscience: whilst enjoying the view as a “transparent eye-ball,” Peabody got poked in her real one. For scholars in the small but energized field of Object-Oriented Ontology, however, Peabody’s myopia could more broadly be said to exemplify, albeit in cartoon form, a kind of object-blindness that in fact plagues the entire tradition of post-Kantian philosophy.

Spearheaded by the work of philosopher Graham Harman, Object-Oriented Ontology (“OOO”) takes issue with Kant’s conclusion that, since the object-in-itself is beyond human perception, the question of object ontology lies outside of philosophy’s purview. It argues that, by exiling object-being from the field of inquiry, Kant’s Copernican Revolution sentenced philosophy to a narrow anthropocentrism, sponsoring a tradition that unjustly privileges human perception as the only available gauge of reality. OOO proposes to remedy this error by framing a new metaphysics that would restore unmediated object-being to the sphere of philosophical speculation. This is not to say that OOO proposes to solve the problem of human finitude—and here is one of many ways OOO diverges from other metaphysics associated with Speculative Realism, the philosophical movement of which OOO is a branch. On the contrary, OOO freely concedes Kant’s point that the ontology of objects is inaccessible—being, in Harman’s words, infinitely “withdraws from human view into a dark subterranean reality” (Harman, Prince of Networks 1). Instead of overturning Kant, OOO universalizes the problem of finitude, arguing that all instances of relation—human and nonhuman, animate and inanimate—are subject to the conditions of mediation. On this view, a billiard ball’s encounter with a felt bumper is no less mediated than Peabody’s encounter with a tree limb. OOO would argue that both Peabody and the billiard ball “prehend” (in Whitehead’s term) their worlds according to rules particular to their constitution. Thus OOO strives to combat philosophical anthropocentrism by insisting that human experience is only one of billions of modes of perceiving the world. That it happens to be our mode does not justify the decision to preclude philosophical speculation about others.

In Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing, Ian Bogost’s enticingly slim and conversational new contribution to OOO, Bogost contends that media studies are uniquely suited to take up this challenge of imagining object “perception.” Since Alien Phenomenology is therefore not a book of object-oriented philosophy per se, but rather a book about object-oriented methodology, it will likely be of more use to those already familiar with OOO than to those seeking an introduction to object-oriented philosophy. Wondering if “scholarly productivity [must] take written form,” Alien Phenomenology envisions an alternative philosophy that would involve fewer precarious sentences and more instructive objects. In this applied practice, objects would serve as “philosophical lab equipment” for exploring and exemplifying theory.

...(more)

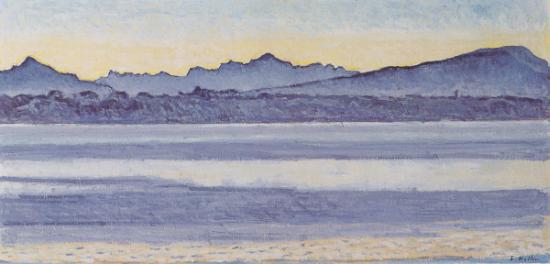

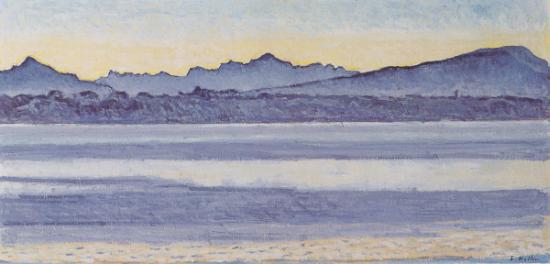

Lake Geneva with Mont Blanc in the morning light

1918

Ferdinand Hodler

d. 19 May 1918

_______________________

St. Patrick and the Druid

an episode from Finnegans Wake (with explication from Joseph Campbell)

presented by Biblioklept

Tunc. Bymeby, bullocky vampas tappany bobs topside joss pidgin fella Balkelly, archdruid of islish chinchinjoss in the his heptachromatic sevenhued septicoloured roranyellgreenlindigan mantle finish he show along the his mister guest Patholic with alb belongahim the whose throat hum with of sametime all the his cassock groaner fellas of greysfriaryfamily he fast all time what time all him monkafellas with Same Patholic, quoniam, speeching, yeh not speeching noh man liberty is, he drink up words, scilicet, tomorrow till recover will not, all too many much illusiones through photoprismic velamina of hueful panepiphanal world spectacurum of Lord Joss, the of which zoantholitic furniture, from mineral through vegetal to animal, not appear to full up to-gether fallen man than under but one photoreflection of the several iridals gradationes of solar light, that one which that part of it (furnit of heupanepi world) had shown itself (part of fur of huepanwor) unable to absorbere, whereas for numpa one pura —— duxed seer in seventh degree of wisdom of Entis–Onton he savvy inside true inwardness of reality, the Ding hvad in idself id est, all objects (of panepiwor) allside showed themselves in trues coloribus resplendent with sextuple gloria of light actually re-tained, untisintus, inside them (obs of epiwo). Rumnant Patholic, stareotypopticus, no catch all that preachybook, utpiam, tomorrow recover thing even is not, bymeby vampsybobsy tap — panasbullocks topside joss pidginfella Bilkilly–Belkelly say pat — fella, ontesantes, twotime hemhaltshealing, with other words verbigratiagrading from murmurulentous till stridulocelerious in a hunghoranghoangoly tsinglontseng while his comprehen-durient, with diminishing claractinism, augumentationed himself in caloripeia to vision so throughsighty, you anxioust melan-cholic, High Thats Hight Uberking Leary his fiery grassbelong- head all show colour of sorrelwood herbgreen, again, nigger- blonker, of the his essixcoloured holmgrewnworsteds costume the his fellow saffron pettikilt look same hue of boiled spinasses,other thing, voluntary mutismuser, he not compyhandy the his golden twobreasttorc look justsamelike curlicabbis, moreafter, to pace negativisticists, verdant readyrainroof belongahim Exuber High Ober King Leary very dead, what he wish to say, spit of superexuberabundancy plenty laurel leaves, after that com-mander bulopent eyes of Most Highest Ardreetsar King same thing like thyme choppy upon parsley, alongsidethat, if please-sir, nos displace tauttung, sowlofabishospastored, enamel Indian gem in maledictive fingerfondler of High High Siresultan Em-peror all same like one fellow olive lentil, onthelongsidethat, by undesendas, kirikirikiring, violaceous warwon contusiones of facebuts of Highup Big Cockywocky Sublissimime Autocrat, for that with pure hueglut intensely saturated one, tinged uniformly, allaroundside upinandoutdown, very like you seecut chowchow of plentymuch sennacassia Hump cumps Ebblybally! Sukkot?

...(more)

_______________________

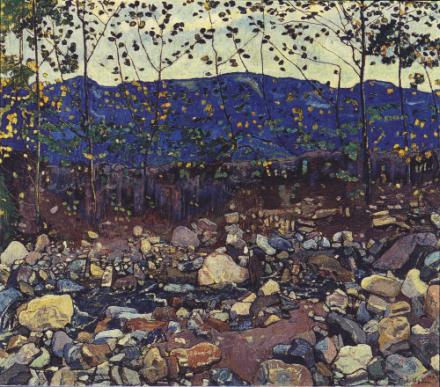

Wooded Landscape

c.1948

Ceri Richards

1903–1971

Romanticism in the Welsh Landscape

Peter Wakelin

_______________________

The Translation Paradox

Tim Parks

Glory, for the translator, is borrowed glory. There is no way around this. Translators are celebrated when they translate celebrated books. The best translations from the Italian I have seen in recent years are Geoffrey Brock’s rendering of Pavese’s collected poems, Disaffections, and Frederika Randall’s enormous achievement in bringing Ippolito Nievo’s great novel Confessions of an Italian into English. Brock, who has also given us an excellent version of Pinocchio, finds an entirely convincing English voice for the troubled Pavese. Randall turns Nievo’s lively, idiosyncratic pre-Risorgimento prose into something sparklingly credible in English. However, neither of these fine books became the talk of the town and their translators remain in the shadows.

The Complete Works of Primo Levi, which contained the work of ten different translators, offered an example of the general situation in microcosm. ...

(....)

Translation matters for those who want to be brought as close as possible to the original inspiration of books that matter (a group that does not necessarily include publishers’ accountants). The choice of translator is crucial when a text is of such a nature that a very special affinity and expertise is required. The problem is that it is hard for the wider public or even the critics really to know whether they have been given a good translation, and not easy even for the editors who have the duty of choosing the translator, fewer and fewer of whom have appropriate second-language skills. So the inclination is to consign the book to a translator who has some reputation, deserved or not, and be done with it. In particular, there is a tendency to privilege those who gravitate around the literary world, as if this were some kind of guarantee of linguistic competence. It is not.

...(more)

_______________________

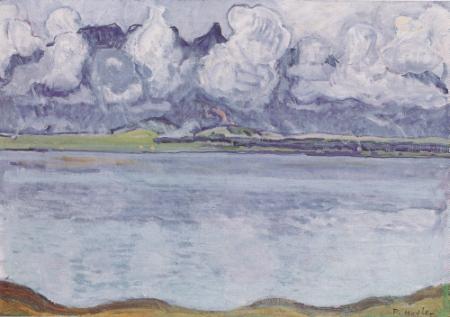

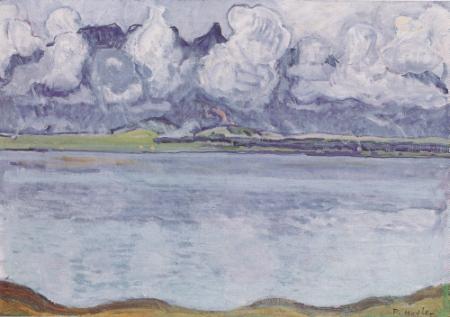

Ferdinand Hodler

_______________________

'Between appearance and character'

Patrick James Dunagan

On Vallejo's 'Selected Writings', ed. Joseph Mulligan

jacket2

(....)

It is readily apparent that Mulligan’s contention is accurate: “Few times in the history of Western Literature has the representation of such a multifaceted figure been so one-dimensional.” ....

(....)

Vallejo’s interior struggle to balance the competing and antithetical impulses he feels towards art and revolution lead him closer to merging them together. He argues a revolutionary writer’s work is meant to “shatter the secular barrier between intelligence and the people, between spirit and matter.” But to do so in such a manner clearly understanding that it is “not for the spirit to go to matter, as any writer of the ruling class would say, but for matter to draw near the spirit of intelligence, horizontally not vertically, man to man.” Vallejo is adamant that true revolutionary writing must witness the arbitrariness of any strict divisions between class and social structures.

The revolutionary writer erroneously thinks that there’s a need for proletarian art, considering that the worker is a pure worker, which is untrue, because the worker also has something of a bourgeois in him. The worker breathes bourgeois air and is more imbued with bourgeois spirit than we would suspect. This is very important in order to conceive of proletarian art or art of the masses.

As an artist Vallejo is wary of overly compulsive impulses within Marxist thought which tend toward uncritical acceptance among leaders and followers alike. He describes how for “hardline Marxists, fanatical Marxists, grammatical artists, who pursue the realization of Marxism to the letter” the result is that “life ends up being at the service of doctrine, instead of the latter at the service of the former”. Vallejo draws historical parallels, pointing out that the problems inherent in Marxist ideology are nothing new: “These are the doctors of the school, the scribes of Marxism, the ones who oversee and, with the jealousy of amanuenses, guard the form and letter of the new spirit, just like all the scribes of all the gospels throughout the course of history”.

...(more)

_______________________

Forest Brook at Leissingen

Ferdinand Hodler

1904

_______________________

Félix Guattari

Thought, Friendship and Visionary

Cartography [pdf]

Franco Berardi (Bifo)

Translated and edited by Giuseppina Mecchia and Charles J. Stivale

(....)

The ‘Félix machine’ is situated at the point of maximum expansion in the blossoming of a nomadic, provisional community. It also accompanies its dissolution.

It doesn’t work in a linear fashion, and therefore it cannot be considered a volition-driven, mono-planar machine. If we want to see it in action, we also have to remember the people, the encounters, the conferences, and then we have to remember the images; we even have to repeat Félix’s gestures, the movement of his hands and eyes. We have to find a hypertextual, translinguistic mechanism that would resemble his way of treating linguistic and emotional matters. We should think back to the mornings and evenings of times past, to the meetings that we hadn’t found the time to attend. And then we have to understand how all these things could have disappeared.

*****

We have never elaborated philosophically the experience of depression. In fact, we have foreclosed it and made it shameful, as if it were something that cannot be addressed in public.

What a happy, felix hypocrisy.

In Félix’s work, depression appears under the rubric the winter years. But we cannot reduce it to the winter years, for it’s not the winter’s fault. Desire is cruel, and so are autonomy, beauty and the irresponsibility of dancing

.Depression presents us with the bill.

The Subject can’t refuse to pay the bill, nor can the singularity.

Depression is the bill.

*****

What is depression?

Depression has something to do with the problem of sense. Sense is

the production of desire. Desire is dissipation.

I am not talking about the subject here, but of the singularity as a

living, conscious and sexual organism, as an organism whose existence

is condemned to dissipation.

Depression is the fallout of the megalomania implicit in the construction

of sense. The enunciation that confers sense to the world,

and not simply limited to function in its economy or to answer already

established questions – this enunciation is a struggle to raise new questions

that happens on a cliff overlooking the abyss of depression.

The lightness of existence is a scandal: the word is born of words and

suspends all relations, the organism, society, sexuality, love, the others.

Even time is suspended. But how long can such a dance last?

This is a difficult dance, in which you may fall. *****

.

Nicolas de Staël

d. Mar 16, 1955

_______________________

The Fashion By Germán Sierra

Translated by Adrian Nathan West

the Quarterly Conversation

(....)

... it is precisely these specialists, aware of this monstrous stylistic asymmetry, who begin to intuit that what is taking place before their eyes may be, not a publicity reel or a scene from a reality show, but an actually unforeseen occurrence; that the pistol, in other words, might be real. And they begin to feel panic or fascination, to make a hollow amid those who are filming and gawking, to slither off (or come closer in order to witness to what was presumably a historic event: a few blocks up, on the other side of Central Park, is where John Lennon had been shot), making way with their bags from Barney’s, Bergdorf Goodman, Gucci, Chanel, Tiffany, and ?, turning their backs on the scene playing out beneath the reflections of Steve Jobs’s orthogonal bubble, meeting eyes with the officers from the NYPD who head into the center of the whirlwind, trying to warn them that something horrible is going to happen, while the identical but divergently dressed women seemed to hypnotize one another like to venomous beasts conscious of their capacity to annihilate (and it seems irrelevant that only one of them is actually armed). And then, a second before the police can act, the one bearing the weapon lets it fall to the ground and the other approaches and embraces her as if nothing had happened at all, as if running into her mirror image on Fifth Avenue were something completely natural, as if appearing between the sights of a gun lacked the least importance, or had even been necessary, essential in order to insert an asymmetrical element into the composition, s a sign of respect for the original on behalf of the copy.

One might say that the possibility of producing and of being reproduced reveals to us the fundamental poverty of being: that something could be repeated means that this power seems to propose a lack in being, and that being is lacking in a richness that would not allow it to be repeated, Maurice Blanchot writes in Museum Sickness

...(more)

Adrian Nathan West on Germán Sierra

A good portion of my paying work involves slogging through reams of contemporary Spanish fiction and writing reader’s reports, sample translations, and press dossiers. In general, the picture isn’t pretty. It’s true that, in any country, literary quality figures fairly low on the scale of what makes a book salable: that both publishers and agents tend to stress tried-and-true themes (World War II, a couple’s struggles with infertility, a crime that reveals hypocrisy in a small town, etc.), risible comparisons (the Lithuanian Sebald, the Maltese Virginia Woolf, a mix of Bolaño and Jeffrey Eugenides), and even grimmer things like a writer’s physical attractiveness. In Spain there are added problems with deep roots in the country’s history: a class structure that often favors the well-connected and mediocre; cultural politics that funnels funds and prizes to writers who express the correct views; and the heritage of the dictatorship, when little information flowed in and creators, confined largely to a national market, missed out on the major aesthetic currents of the twentieth century. Much has changed, but much hasn’t: the best-seller lists remain crowded with books lacking in appeal to foreign markets, and higher-brow writers are praised for pastiches so transparent as to merit pillory.

Germán Sierra’s work is a rare exception. A respected neuroscientist at the University of Santiago de Compostela, he is one of a small group of writers to have considered in earnest the challenges contemporary science presents to the narrative model that has come down to us from the nineteenth century, with its emphasis on the sovereign role of individual psychology as an engine of plot. He brings to mind Philip K. Dick, but less speculative, more uncanny, and tinged with a hard-edged griminess reminiscent of Darby Crash–era Los Angeles. ...(more)

_______________________

Nicolas de Staël

_______________________

Viktor Shklovsky and the horror behind ostranenie

Alexandra Berlina

(....)

In English, ostranenie is known as “defamiliarization”, “e(n)strangement”, “making strange” or “foregrounding”, all of which have the potential to confuse. Being estranged from, say, one’s wife is the emotional opposite of the reconnection through wonder that is ostranenie. One might also think of Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt; though he was probably inspired by the Russian theorist, the German playwright believed in restraining feelings in order to promote critical thought. Shklovsky, on the other hand, saw thought as inseparable from emotion. (As it happens, contemporary cognitive science agrees.) To avoid such confusions, I will stick to the original term. Not that it is correct: it should have been ostrannenie, from the Russian strannyi, strange. But orthography was not one of Shklovsky’s fortes, and, as he put it decades later, the neologism “went off with one ‘n,’ to roam the world like a dog with an ear cut off”. The word is strange to Russian speakers, too – which is arguably a good thing, considering what it means.

But what does it mean? Shklovsky’s seventy years as a scholar and his penchant for self-contradiction (it was his method of thinking, his Socratic monologue) conspire against a clear-cut and complete definition. He used ostranenie to describe devices as well as their effects, the text as well as the mind. Sticking with the latter, we can define ostranenie as a cognitive-emotional state, the renewed awareness produced when the habitual is depicted in an unusual way. What is habitual differs from reader to reader, from spectator to spectator. The intended effect can fail to manifest itself; conversely, one can experience ostranenie where it was not intended: say, reading a description of one’s country written by an astonished foreigner. There are a great many ways of making things strange – for instance, adopting the perspectives of aliens and animals; naming directly what is usually couched in euphemisms; or describing in minute detail what is usually summed up in a single word.

...(more)

via the page

_______________________

Nicolas de Staël

|