|

mid-December rain

Ottawa river at Arnprior

photo - mw

_______________________

The Weather

John Newlove

1938 - 2003

From: Apology for Absence: Selected Poems 1962-1992

I'd like to live a slower life.

The weather gets in my words

and I want them dry. Line after line

writes itself on my face, not a grace

of age but wrinkled humour. I laugh

more than I should or more

than anyone should. This is good.

But guess again. Everyone leans, each

on each other. This is a life

without an image. But only

because nothing does much more

than just resemble. Do the shamans

do what they say they do, dancing?

This is epistemology.

This is guesswork, this is love,

this is giving up gorgeousness to please you,

you beautiful dead to be. God bless

the weather and the words. Any words. Any weather.

And where or whom. I'd never taken count before.

I wish I had. And then

I did. And here

the weather wrote again.

.....................................................

A Class of One’s Own: an all-too-brief appreciation of the poetry of John Newlove

Poeta Doctus

The status of John Newlove’s poetry in Canada is curious. The consistent admiration and acclaim it received over nearly four decades, from even before the publication of his Governor General’s Award winning Lies (1972) up to and including the appearance of his latest volume of selected poems A Long Continual Argument (2007), would seem to suggest that his work would be more widely and closely studied, both by scholars and poets. His publishing only one trade edition after Lies, The Night the Dog Smiled (1986), and that the only one before his death in 2003, is surely in part to blame. Moreover, changes in taste and tendencies in academic criticism during this time, anathema to the singular pathos of his polished and laconic lyrics, surely served to only further marginalize the work of a man already famously a loner. It is perhaps reason for optimism in this regard that Jeff Derksen, a poet associated with Canada’s avant-garde, essays a postmodern sociological reading of Newlove’s poetry in his afterword to A Long Continual Argument. As bracing as it would be to make a case for a more sustained and scrupulous critical attention to Newlove’s work, I will here follow Newlove’s own example, the one he provides at the end of Derksen’s afterword, where he invites Derksen in to show him “the careful syllabics of an Irish writer…, literally counting the syllables per line…”.

(....)

Newlove names that “difficult thing” at the heart of his poetic labour. In his Caroline Heath lecture, he goes on to explain, “What I’m trying to be is human, without knowing what the word means”. Here is an endlessly open-ended theme, whose horizon swallows polemics against “Humanism”. Here, Newlove takes up a question not a doctrine, and though he may seem, at times, to “say things for the sheer pleasure of the phrase, forgetting that [he is] speaking to humans, with humans, forgetting to be human”, who hears or overhears him, by virtue of the dialogue understanding demands, becomes his interlocutor, which is, as it were, the last word:

All writing is saying, even in the choice of word and structure, this is what you need to know, this is what I need to know, this is the way the world is, this is the way the world should be, this is me, urgent and alive. I want to talk to you. ...(more)

.....................................................

“These Things Form Poems When I Allow It”

Jeff Derksen

After John Newlove

(....)

... While any author’s selected works is a gathering of historical gestures and contexts, both textual and social, a collected works that spans four of the most slyly transformational decades of the long twentieth century is necessarily nested in and intertwined with the historical conditions. These conditions are not blunt nor even graspable in their totality, but are rippling with friction and conflict, as well as, in the case of A Long Continual Argument, moments of clarity, joy, disappointment, and resignation. Further, these moments cohere on a ground where individual identity and subjectivity are in an unstable relationship to the community and group (whether ethnic or racial community or the national imagined community) and the other (dramatically, comradely, and at times problematically in Newlove’s work, First Nations and women).

It’s useful, then, to acknowledge or even confront the fact that a selected or collected works, particularly a posthumous one, periodizes an author’s work — and I think it is necessary and rich to read the poetry while keeping in mind the cultural, social and aesthetic relationships it was produced within, in dialogue and reaction with.

Two strains that I think arises throughout A Long Continual Argument are a dialogue with the cultural discourse of Canadian Literature and an address to, a disgust with, and a resignation to the shape of society and the fleeting joys and false openings an individual imagination conjures and hopes for. By reading this selected works as a periodizing of Newlove’s poetry within these frames, I borrow from Fredric Jameson’s notion of the “period” as “not some omnipresent and uniform shared style or way of thinking and acting, but rather as the sharing of a common objective situation, to which a whole range of varied responses and creative solutions is then possible, but always within the situation’s structural limits”. The long continual argument of the title, is in fact a dialogue between these very “structural limits” that Newlove identifies, defines, and writes of and the “creative solutions” that are experienced, imagined, or shut down at various levels and places.

...(more)

A Long Continual Argument:

The Selected Poems of John Newlove chaudiere books

_______________________

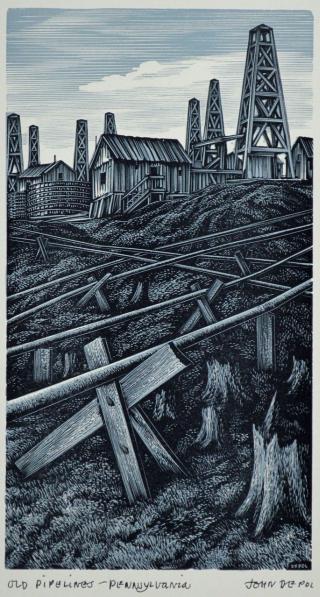

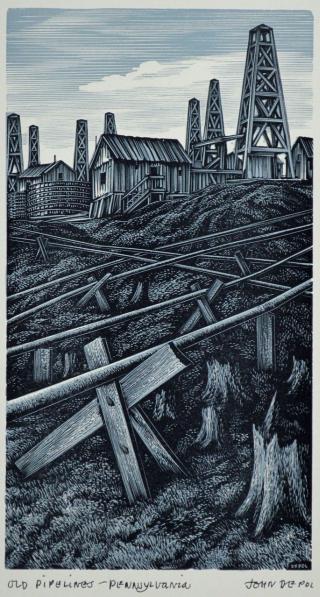

Old Pipelines, Pennsylvania

John DePol

1913 - 2004

_______________________

John Newlove's "Ottawa poems"

rob mclennan

It’s Winter In Ottawa

The streets are full of overweight corporals,

of sad grey computer captains, the impedimentia

of a capital city, struggling through the snow.

There is a cold gel on my

belly, an instrument

is stroking it incisively, the machine

in the half-lit room is scribbling my future.

It is not illegal to be unhappy.

A shadowy technician says alternately,

Breathe, and, You may stop now.

It is not illegal to be unhappy.

...(more)

_______________________

Agnes Heller and “Everyday Revolutions”

Anna-Verena Nosthoff

publilc seminar

(....)

Poland in early summer 2014. Mosquitoes dominate the stuffy green of Wroclaw’s Juliusza Slowackiego Park; somewhere, in its very midst: philosophy. Slight coldness surrounds the seminar room; an almost imperceptible air conditioning hums a constant hum. As usual, Ágnes Heller is accompanied by her light sun hat. She lays it on the table, right next to it the calmness of the hands of a philosopher.

The story of Funes seemingly occupies her mind. She admires the true fictions of his literary creator—not least because they touch on moral dilemmas. By the time Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges invented Funes’s impeccable memory (1942), she was a child of thirteen. Today, being a grown-up philosopher, the Hungarian Jew has enough reasons to question the desirability of a mechanical memory.

Of course, memory capacity is indispensable to life. Heller has radical skepticism about her own capacity for remembering; she rather trusts in the durability of the letters in her diaries. However, it is not without cause that Borges writes how Funes had little talent for actual, reflective thinking: “To think is to forget differences, generalize, make abstractions. In the teeming world of Funes, there were only details, almost immediate in their presence.”

Details of a complete lifetime. For Funes, this means that everything will always be available, each fragment of a moment, never again only a slightest loss of time. In turn, surely, this makes any search of time superfluous. By possessing full, radical, and relentless transparency, one would probably win less than one would lose; Heller seems aware of this. The last thing she would want to do is simply juxtapose Funes’ associations with a composition of recurring Madeleine moments. Lime-tree-blossom tea, Combray—nothing but a beautiful Proustian fiction.

...(more)

_______________________

Intentional Philosophy as the Neuroscientific Explananda Problem

rsbakker

Three Pound Brain

The problem is basically that the machinery of the brain has no way of tracking its own astronomical dimensionality; it can at best track problem-specific correlational activity, various heuristic hacks. We lack not only the metacognitive bandwidth, but the metacognitive access required to formulate the explananda of neuroscientific investigation.

A curious consequence of the neuroscientific explananda problem is the glaring way it reveals our blindness to ourselves, our medial neglect. The mystery has always been one of understanding constraints, the question of what comes before we do. Plans? Divinity? Nature? Desires? Conditions of possibility? Fate? Mind? We’ve always been grasping for ourselves, I sometimes think, such was the strategic value of metacognitive capacity in linguistic social ecologies. The thing to realize is that grasping, the process of developing the capacity to report on our experience, was bootstapped out of nothing and so comprised the sum of all there was to the ‘experience of experience’ at any given stage of our evolution. Our ancestors had to be both implicitly obvious, and explicitly impenetrable to themselves past various degrees of questioning.

We’re just the next step.

...(more)

_______________________

December 16, 1907

Carts full of turkeys queueing on the quays in Waterford city,

at the foot of Conduit Lane,

perhaps on the way to Flynn's Poultry Stores.

National Library of Ireland on The Commons

_______________________

Three poems

John Newlove

jacket 34

Driving

You never say anything in your letters. You say,

I drove all night long through the snow

in someone else’s car

and the heater wouldn’t work and I nearly froze.

But I know that. I live in this country too.

I know how beautiful it is at night

with the white snow banked in the moonlight.

Around black trees and tangled bushes,

how lonely and lovely that driving is,

how deadly. You become the country.

You are by yourself in that channel of snow

and pines and pines,

whether the pines and snow flow backwards smoothly,

whether you drive or you stop or you walk or you sit.

This land waits. It watches. How beautifully desolate

our country is, out of the snug cities,

and how it fits a human. You say you drove.

It doesn’t matter to me.

All I can see is the silent cold car gliding,

walled in, your face smooth, your mind empty,

cold foot on the pedal, cold hands on the wheel.

...(more)

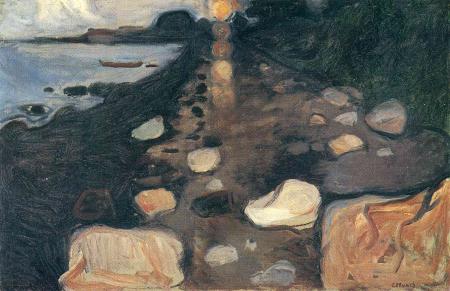

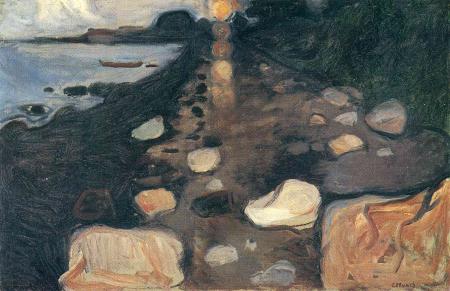

Moonlight on the Shore

1892

Edvard Munch

b. Dec 12, 1863

_______________________

Doméstica

Gabriela Torres Olivares

translated by Teresa Carmody

conjunctions

They come with the bearing of a retrovirus. Their bodies synchronize in certainty. An idea bustling between their eyebrows and taming their strangeness, bundling gesture between their eyes. After a brief survey of the place, the man in the wheelchair makes a sign to the accompanying blonde, and she holds the handlebars, sliding him on the irregular pavement. Their texture jumps out like a sticky mess, forcibly converting the landscape into a collage. And like that, they decontextualize any routine, disappearing like phantom disturbances through the wall of Doña Rosita’s door.

They had probably traveled kilometers, though it’s difficult to guess whether their disastrous countenance comes from their lives or from a hurried passage; afternoon itself is a mature morning with salty maps staining its clothes. Or maybe the sun ages their surprise, eroding their motives in puddles of sweat. The image of their arrival is like the accident of walking under a ladder, noticing, and trying to rewind or forget the amazing superstition: without success. The visitors exist despite the improbable scene, or maybe improbability is the stage for their appearance, a trick with the costume of fate. As if his rolled hat or dingy white cotton shirt, his discolored suede sack or his pants turned back to shelter his stumps (secured by a pair of pins), could pass unnoticed. With equal subtlety, her miniskirt, stiff, with her Asian umbrella and long leathery legs or her garish blouse of curlicues and her beige heels caked in mud: it seemed no one had bothered to tell them the costume party has been canceled.

...(more)

_______________________

Radical intimacy, technological estrangement, and hyphen as psychic portal

Masha Tupitsyn interview

bomb

(....) That’s always the question: Are we together or are we separate? The politics of breaking up have structured my whole life. As an only child of parents that have stayed together and are deeply in love, I guess I fundamentally can’t understand why people can’t stay together. Togetherness is my originary model, yet most people, including me, don’t have lasting relationships. That’s probably the entry point of all my work. The answer—as the film’s titles suggest—is in the construction, the thinking through—not in the classification. The final answer is love. It’s what’s left in the end. It’s also everything ahead, which is why I leave LOVE for last in Love Sounds. You don’t start with love, you work for it, you learn it; you invent and realize it. The titles, which are either doubled—DESIRE-SEX—or tripled—FATE-TIME-MEMORY—work as progressions toward and through a relation. They are ways of thinking through that ultimate question of the Two; of how to love. So the break (hyphen, dash, tear) is also the place of unity and potential. At every moment we can choose how far we can go, how much we can endure and forgive, and what that will require. And those decisions are complicated, demanding, imaginative, ongoing. You can think you’re breaking up with someone, but then decide you want to fight through/for something more. So, what does it mean to FIGHT (also one of the film’s sections)? It can mean that conflict isn’t an end. Conflict can be a process of repair and endurance.

(....)

In Stanzas, Agamben writes, “the problem of knowledge is a problem of possession, and every problem of possession is a problem of enjoyment, that is, of language.” In the case of LS, the problem of language is also the subject of the film. Which is about being and not being together. There are a lot of ways to tell someone something, but language is like a storefront for not-telling. Language is a problem because it is a script and a game that has no real consensus or stakes anymore. It isn’t reliable or embodied or physically located. We all act like we’re not allowed to be upset or unnerved by language or to expect anything from it. Text messages always point to this anxiety of technological affect, especially when it comes to love and desire. Yet, rather than say this form of technology is inadequate, we capitulate to it. We’re trapped in reproducing certain drive-by affects that are counterintuitive and emotionally estranging. We break off from people, instead of from the technologies or affects themselves. Listening is a way of asking ourselves which forms work toward radical intimacy and engagement and which ones don’t. Listening is a pedagogical process that involves intent and understanding, so it works through and engages with the problem of language. It’s constructive and attentive in that way. We can listen without seeing. And intensely feeling things, as we’ve discussed, is a way of hearing. There are also different things we can listen to—the seen and unseen, the said and unsaid: touch, intuition, gesture, absence. But these forms of attunement are not openly acknowledged forms of communication. They’re considered unspoken, illegitimate, often making them impossible to respond to, or even describe. In A Thousand Plateaus Deleuze and Guattari write: “Life does not speak; it listens and waits.”

...(more)

Love Will Tear Us Apart, Again: Tupitsyn Art Review

McKenzie Wark electronic book review

McKenzie Wark explores the work of Masha Tupitsyn as a pathway into the conditions of life in the 21st Century, somewhere above (or below) the framework of mediated experience, even beyond the limits of what we often call “theory.” With Tupitsyn, Wark troubles the current stasis of representation that stultifies thought in this age of unrepentantly industrialized culture, not by turning us away from the spectacle, but by smashing right through it, picking up its pieces, and discovering new things in the wreckage.

_______________________

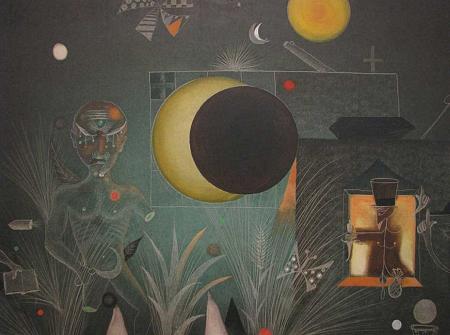

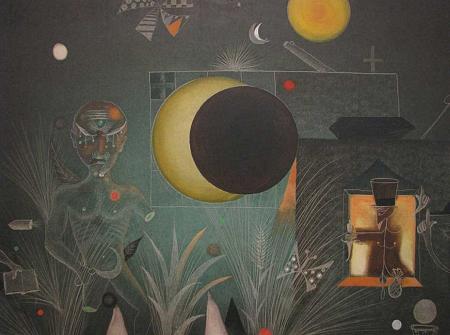

Asia

1951

Antoni Tàpies

b. Dec 13, 1923

_______________________

i can only speak for myself

Dominic Jaeckle

reviewing Robert Walser, Looking at Pictures, trans. Susan Bernofsky, Lydia Davis & Christopher Middleton

This new collection of Robert Walser’s ekphrastic writings – Looking at Pictures, a select twenty five pieces that span Walser’s career, collating original and extant translations of Walser’s work – aspires towards a redirection of his writings. While the work encompasses the personal through an exploration of the tendentious qualities of particular works of art and a dissection of the impulse to produce and create, it also leans towards a view of the public life of the art object. Alluding to the difficult interpolation of consumption and observation, it draws attention to selfishness as a critical epithet central to our habits in the museum, suggesting that we design ourselves appropriately to the digestion of work – soft work rather than hard – that paints little beyond a picture of personality as reflected in the abstract objects of creative labour.

The image is central to Walser’s legacy and, beyond his portrait, the more preponderate pictures that pertain to his body of work are of his own notes; the abbreviated script or “delicate” shorthand, as Walter Benjamin termed it, in which Walser would practice his “pencil method” on the backs of envelopes, business cards, rejection slips and telegrams in a private language. A script particular to Walser’s personal economy of symbols – exclusive to his object of attention. The privacy innate to the cryptic character of Walser’s “microscripts” proves significant here; Middleton suggests that this backlog of materials could truncate as an autobiography beyond decipherability but insists that, as Walser’s readers, a chronological sequencing of the texts should not allure us. “Walser’s own notes should not be mistaken as a means to focus attention on Walser as a person.” Both as author and as individual, Middleton suggests that Walser’s work “articulates a large and general cast of mind, such as strictly personal writings seldom do”. This thesis is enacted across Looking at Pictures but is strung through with the melancholy of paradox. How do we move between the general and the personal? How can we write for anybody but ourselves? How can we objectify and calculate the processes of engagement and hours of work that formulate and arrange themselves in the simple facticity of a picture? These questions litter a reading of the essays, fictions and reviews included here and, if Walser was to respond to such interrogation with a simple, aphoric answer, perhaps we could suggest that the collection presents one singular remark as rephrased throughout its contents: “I can only speak for myself.” In other words, the only way into the general is through an onus on the particular.

...(more)

_______________________

L'Enveloppe

Antoni Tapies

1968

_______________________

Ingeborg Bachmann: Nobody has the Right to Appeal to the Victim

translated by Pierre Joris

(....)

But the human who is not a victim is in twilight, is twilight existence par excellence, even the one who has nearly fallen victim continues with his errors, creates new errors, is not “in the truth,” is not privileged. No one has the right to appeal to the victim. That is misuse. No country and no group, no idea may appeal to their dead.

But the difficulty to express this. Sometimes I feel very clearly one or the other truth as it arises and then feel it being trampled down in my head by other thoughts or sense it withering away, because I don’t know what to do with it, because it cannot be shared, because I don’t know who to communicate it or, exactly, because there is nothing that demands this sharing and I can’t fasten on anywhere nor on anyone.

...(more)

_______________________

"Stage design for Shakespeare's Hamlet N. 9"

1954

Natan Altman

(1889-1970)

_______________________

The Future After the End of the Economy

Franco Berardi Bifo

e-flux

(....)

Only if we are able to disentangle the future (the perception of the future, the concept of the future, and the very production of the future) from the traps of growth and investment will we find a way out of the vicious subjugation of life, wealth, and pleasure to the financial abstraction of semiocapital. The key to this disentanglement can be found in a new form of wisdom: harmonizing with exhaustion.

Exhaustion is a cursed word in the frame of modern culture, which is based on the cult of energy and the cult of male aggressiveness. But energy is fading in the postmodern world for many reasons that are easy to detect. Demographic trends reveal that, as life expectancy increases and birth rate decreases, mankind as a whole is growing old. This process of general aging produces a sense of exhaustion, and what was once considered a blessing—increased life expectancy—may become a misfortune if the myth of energy is not restrained and replaced with a myth of solidarity and compassion.

Energy is fading also because basic physical resources such as oil are doomed to extinction or dramatic depletion. And energy is fading because competition is stupid in the age of the general intellect. The general intellect is not based on juvenile impulse and male aggressiveness, on fighting, winning, and appropriation. It is based on cooperation and sharing.

This is why the future is over. We are living in a space that is beyond the future. If we come to terms with this post-futuristic condition, we can renounce accumulation and growth and be happy sharing the wealth that comes from past industrial labor and present collective intelligence.

If we cannot do this, we are doomed to live in a century of violence, misery, and war.

...(more)

_______________________

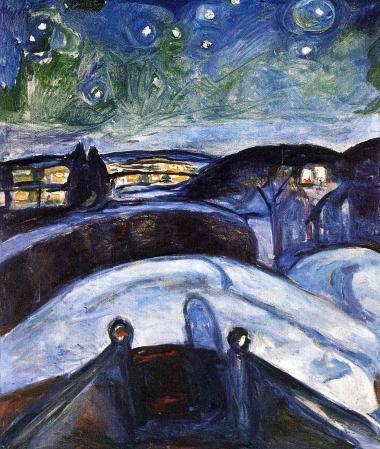

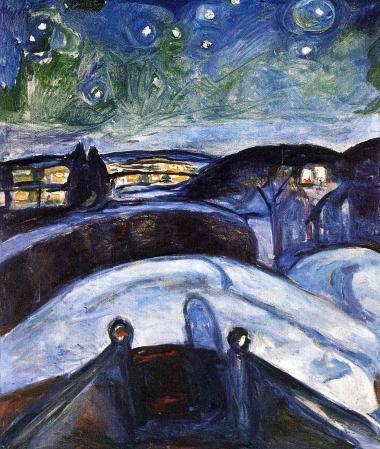

Starry night

Edvard Munch

1922

The Century of the Self

Adam Curtis

Happiness Machines, The Engineering of Consent,

There is a Policeman Inside All Our Head: He Must Be Destroyed,

Eight People Sipping Wine in Kettering

commentary by George Prochnik

How did British and American liberal politics devolve to the point where eight people sipping wine and popping back Cheerios have gained the power to define the policy choices of a national leader? How did our society become so selfish, trivial, materialistic and enslaved to its bottom-most register of desires? What enabled our businesses to gain a dictatorial control over the public imagination? Why did everything get so dark, dystopic and just plain dumb?

Adam Curtis’s important film, The Century of the Self, supplies an answer to all these questions—and more. “There’s A Policeman Inside All Our Heads: He Must Be Destroyed,” and “Eight People Sipping Wine in Kettering” are the two concluding episodes of a sweeping production. Curtis tracks the path by which a broad cultural revulsion against the notion of being possessed by corporate sprachen inspired a multifold liberation movement that crumpled into a new, ultimately vapid, ideal of self-empowerment, which, in turn, provided fertile soil for big business interests to sow a hyper-crop of rampant consumer desire. For the final twist, Curtis shows how the techniques developed by corporations to sell products were imported into the political arena. As mass surveys, aimed at determining how best to pander to lifestyle preferences of swing voters, became the strategy-of-choice for the Democratic Party under Clinton, and then—copycat killer-style—for New Labor in the election that brought Tony Blair to power, the higher social values of liberal politics became inexpedient, lost in a wave of redundancies. These two episodes present a devastating portrait of the reduction of the great democratic experiment to radically self-centered nichepolitics. The grand social collective doodles off into cocktail party banter.

...(more)

_______________________

I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading – treading – till it seemed

That Sense was breaking through –

And when they all were seated,

A Service, like a Drum –

Kept beating – beating – till I thought

My Mind was going numb –

And then I heard them lift a Box

And creak across my Soul

With those same Boots of Lead, again,

Then Space – began to toll,

As all the Heavens were a Bell,

And Being, but an Ear,

And I, and Silence, some strange Race

Wrecked, solitary, here –

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down –

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing – then –

Emily Dickinson

b. Dec. 10, 1830

_______________________

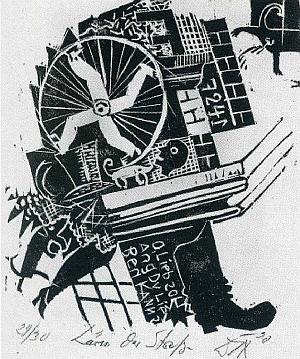

The Master and Margarita

Zuev

Bookplates by the Russian artist Vladimir Zuev

From the collection of Richard Sica

_______________________

the eros of soft exterior shocks: preverbs [pdf]

George Quasha

metambesen

a jolting series of prearranged disappointments

I’m thinking metaphors in my sleep like conversations with dead philosophers.

Here we are again in the moving center.

Friend is never far between.

The poem is its poetics when over time its consequences are inescapable.

Only the reader holding in will ever know.

Verbals stand in relation.

Our misunderstanding is mutual.

It holds together as we speak.

There’s more entry prize in walking naked sacred.

Text sources the unperceived by way of the underread.

No surprise there. Nor running scared weird.

Verbals sit recovering.

It holds together as I speak, as if talking to myself, but I’m not all here.

Our misunderstanding is intimate.

Oscillatory focus is open in the middle and sharp at the edges.

I river to keep my banks apart.

Thinking metaphor is knowing between things, drawing from secret slush funds.

No comparison. Just sounds.

Reference is mask.

Shifting weight, lifting clouds, behaving days.

A complete statement is true in itself.

George Quasha at the Poetry Foundation

A singular sacred

George Quasha

a short 80th-birthday homage to Jerome Rothenberg

jacket2

Maybe a secret of poetry is that its most disturbing power is something we never quite see or hear or make sense of, but which is invisibly transmitted from the bones of the poet to bones of the receiver. When I think back over the nearly five decades of knowing Jerry Rothenberg I register a kind of gradual infiltration of my bodymind system, beginning when I was about 20 and a student at NYU and starting to attend readings at Le Métro Café on 2nd Avenue. Confused at first by what I was hearing in the readings, I had to wonder whether for instance Jackson Mac Low performed in magical mumbo-jumbo—after all it spooked the cops who came to give tickets to Moe, the owner, for offering entertainment without a cabaret license. If the cops weren’t entertained, neither was I at first. But over time the voices of Jackson and Jerry and Paul Blackburn and David Antin and Harold Dicker and Armand Schwerner and Allen Ginsberg accumulated in my cells and soon reached critical mass where I would no longer be me as I had thought I was me. And involuntarily giving up being that unconnected me I could begin to experience an actual power in the poems read, even at their most jarring. I saw that quality first in Paul, Jerry and David, each in very different ways. Over time I got to know a Jerry Rothenberg perhaps only fully available in collaboration. An aspect of the greatness of the poet Rothenberg is also a secret of the Jerry who understands working with as one of the gates to poetic nature itself.

...(more)

_______________________

from Red D Gypsum

Furtherance

J. H. Prynn

google books

_______________________

Stars, Tigers and the Shape of Words [pdf]

Williams Matthews Lectures 1992

J.H. Prynne

.....................................................

Theories of language imply theories of poetry, particularly if poetry can be defined as a significant and coherent deformation of the linguistic system, and it is not uncommon to find poets engaging with such theories. However, what is unusual about JH Prynne's lectures, Stars, Tigers and the Shape of Words, is that he kicks at the cornerstone of the structuralist edifice, the theories of Saussure. He examines the arbitrariness hypothesis of Saussurian linguistics - which states that there is no motivated link between signifier and signified - through 'flamboyant readings' of 'Twinkle Twinkle Little Star' and Blake's 'The Tyger'. Such readings, which involve the discovery of embedded lexical and lettrist play and readings which are supported by elaborations of historical and sociological contexts (and combinations of the two), are used to show that, while the linguistic system can be accepted as operating according to principles of arbitrariness, a potent secondary motivation of language is found in poetry. Affected as this is by social and contextual limits - whether they be the nature of consensual reading at any time, or of the author-reader relationship, or of the particular powers of certain genres and communally recognised literary forms - local damage can be inflicted upon the global linguistic system. This creates, Prynne concludes, a space for innovative reading that is socially and historically determined, and which 'can be intelligibly active as a practice of inscribing new sets of sense-bearing differences upon the schedule of old ones'. This insistence upon the social over the systemic, the diachronic over the synchronic (to use terms which Prynne assiduously avoids), is matched by other critiques, such as that of Bourdieu, which also teach us that the social transformations of language constitute its collective life.

Robert Sheppard, Buoyant Readings

_______________________

Dante

Vladimir Zuev

Art-exlibris.net

The Digital Exlibris Museum

Adolf Dietrich

1877-1957

_______________________

Willam H. Gass’s new story collection, Eyes

reviewed by Greg Gerke.

(....)

Gass, a former philosophy professor, but more appropriately a philosopher of the word and sentence, has devoted his life to showing how the world is within the word and how a sentence has a soul and is its own story, developing spindle diagrams of sentences that he first debuted when speaking of the work of Gertrude Stein in the 1970s. In the last literary years there has been renewed interest in Gordon Lish and his theory of consecution, writing sentence upon sentence by means of repetition of what came before, be it word or sound, built from the work of Harold Bloom, Denis Donoghue, and Julia Kristeva. Gass and Lish are squarely in the same tradition — if you don’t have music no one will listen or at least won’t listen very hard. It stretches back to Stein, Joyce, James, Melville, Dickinson, Emerson and over the ocean to the authors of Baroque prose, Shakespeare, and back to the nameless bards and authors of the Bible, and to Homer. This tradition has nothing to do with the moralizing realism that’s come to dominate US literary fiction or the epiphany moment whether in prose or verse. Some ask for fiction to show us how to live and some ask for entertainment. Absent religion, the pagan Pater says, “For art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments’ sake.” Politicians pander, but parents, teachers, and friends, or some combination, are those consistent pitchers who help us learn how to live and what to do. Literary language communicates something ineffable, even parables work by metaphor. Rilke, Gass’s lodestar, had the gumption to end a poem, “You must change your life,” yet art is not usually as easy as self-help. It presents alternative realities that may be accepted, reviled, or ignored. So sentences come to us giving nothing but the beauty of their words — more than enough, or as Gass said, “Because a consciousness electrified by beauty — is that not the aim and emblem and the ending of all finely made love?”

...(more)

_______________________

Adolf Dietrich

_______________________

the exploitation of the technical

Matt Bluemink on Bernard Stiegler

The question concerning technology, it seems to me, has always been one riddled with negativity and pessimistic determinism. As a child growing up in the first age of the internet I had seen the way in which technology could have a drastic and fundamental change on the way human beings interact with each other and with society as a whole. As my interest grew deeper I started to wonder how these changes could be explained. Was technology really destroying our interpersonal relationships and our culture?

In the work of Bernard Stiegler, we find a philosopher who argues that it is by no co-incidence that technology is shaping humanity to such a degree, in fact technicity is inherent in what it is to be human. Stiegler shares many of the concerns that the previous critics of technology have possessed, yet at the same time wants to show us that it is not impossible for technical progression to lead an optimistic future if it is directed in the right way.

One of the key ideas in Stiegler’s work is what he defines in For a New Critique of Political Economy as ‘grammatisation’. Grammatisation can be understood as the ‘technical history of memory, in which hypomnesic memory continually reintroduces the constitution of a tension within anamnesic memory’. He draws this distinction between anamnesic memory and hypomnesic memory from Jacques Derrida’s essay ‘Plato’s Pharmacy’ in which Derrida develops his deconstruction of metaphysics based on his reading of Plato’s Phaedrus.

(....)

It might seem that Stiegler’s outlook is a bleak one, yet, as implied by the adoption of the dualistic term pharmakon, the mass exteriorisation of memory that has led to the dis-individuation of the producer and the consumer can also have curative qualities. The pharmakon is always the poison and the cure. The extraordinary mnesic power of digital networks have the potential to bring back savoir-vivre through the interconnectivity brought about by the internet. What the internet provides is the potential for a collective unity of individuals that step beyond the hyper-industrial categories of proletarianised consumers and producers. It is their interconnected desires that have the potential to provide the libidinal energy necessary to counteract the negative tendencies of grammatisation. The savoir-vivre knowledge that was lost through the hyper-industrialisation of culture therefore has the potential to be regained through the connections brought about by socio-digital network innovations. It is these curative qualities that it are imperative for us to work on, failing to do so we risk a severe and systematic loss of knowledge.

...(more)

_______________________

When Nothing Is Cool

Lisa Ruddick

the point

(....)

Is there something unethical in contemporary criticism? This essay is not just for those who identify with the canaries in the mine, but for anyone who browses through current journals and is left with an impression of deadness or meanness.(....)

The reflections that follow focus largely on English, my home discipline and a trendsetter for the other modern language disciplines. These days nothing in English is “cool” in the way that high theory was in the 1980s and 1990s. On the other hand, you could say that what is cool now is, simply, nothing. Decades of antihumanist one-upmanship have left the profession with a fascination for shaking the value out of what seems human, alive, and whole. Some years ago Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick touched on this complex in her well-known essay on paranoid reading, where she identified a strain of “hatred” in criticism. Also salient is a more recent piece in which Bruno Latour has described how scholars slip from “critique” into “critical barbarity,” giving “cruel treatment” to experiences and ideals that non-academics treat as objects of tender concern. Rita Felski’s current work on the state of criticism has reenergized the conversation on the punitive attitudes encouraged by the hermeneutics of suspicion. And Susan Fraiman’s powerful analysis of the “cool male” intellectual style favored in academia is concerned with many of the same patterns I consider here. I hope to show that the kind of thinking these scholars, among others, have criticized has survived the supposed death of theory. More, it encourages an intellectual sadism that the profession would do well to reflect on.

...(more)

_______________________

Adolf Dietrich

_______________________

From OOO to P(OO)

McKenzie Wark

public seminar

I have been reading the work of Timothy Morton with pleasure for many years now. Originally a scholar of English romantic poetry, I find his work reads best as poetry, or perhaps a poetics, as a singular Mortonian vision of the world – or in this case, a vision of the absence of the world. For his most recent book is called Hyperorbjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World.

I have some problems with it as theory, however, and will try to outline here where my own thinking and Morton’s both overlap and diverge. Perhaps bodies of work are a case of what Morton calls hyperobjects: spooky, nonlocal, pervasive entities that are at once in us which we are in. In which case best way to proceed is simply to map one onto the other and find the edges where such things resonate.

One of the merits of Morton’s work is its attention to twenty-first century problems. Morton: “To those great Victorian period discoveries, then – evolution, capital, the unconscious – we must now add spacetime, ecological itnerconnection, and nonlocality.” If one suspends disbelief and reads him texts as a science fiction poetics, one starts to breath the (overly warm, possibly radioactive) air of the times. Branching off from Alphonso Lingis, Morton offers a phenomenology for the strange and untimely objects one increasingly seems to encounter –hyperobjects.

...(more)

_______________________

McKenzie Wark on Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects

S.C. Hickman

(....)

Like many current scholars Wark will lambast ooo with the new or not so new notion of the Anthropocene “as a new historical age in which nonhumans are no longer excluded,” and as a new stage of geology in which humans are included. That to me is the truly strange thing to think”. A cursory look on amazon.com will bring one to the academic grist mill collection of titles dealing with this new Anthroposcene. This new category of scholarly work allows many on the left of the climate debates to demarcate the carbon-footprint of Man upon the environment as if to say: “See, we knew it all along. Man is bad. Environment is Good. We must instigate new reforms, enforce a new carbon age on Man and force him to curtail his wild and aimless degradation of the environment. He is no longer the shepherd of the world. In fact his just a bit player in a cosmic scenario that puts him in flat competition with the rest of the flatlanders of the universe.” The spectrum of new agers and philosophers following the call of the Anthropocene discourse is just another of the latest trends to build a new political movement against a tired and outworn Marxist dialectic that has lost its steam and utopian desire. Will it find it here?

...(more)

_______________________

Adolf Dietrich

_______________________

Nakahara Chuya: Six Poems Newly Englished, Plus a Single Transcreation

Translations from Japanese by Jerome Rothenberg & Yasuhiro Yotsumoto

Evening With Sunlight

hills retreat from me

arms crossed over chest

& sunsets colored golden

mercy colored

grasses in fields

sing oldtime songs

on mountains

trees

old hearts remote & still

here in this time & place

I’ve been

meat of a clam

a babe’s foot stamps on

here in this time & place

surrender

stubborn

intimate

arms crossed walking off

...(more)

Leon Kossoff

_______________________

6 Poems

Agnieszka Kuciak

parallel translation by Ewa Chrusciel & Elizbieta Kotkowska

exchanges

Your letter’s found me again among words.

How are things? The whir of dictionaries.

Layer after layer I scrape the darkness

From a temple fresco. Or I travel

to the amiable antipodes in a small

paper boat. Again among words.

I’ve got loads to do, because the true spells

are written in a tongue which does not exist.

I know they exist, because I experience

daily miracles: he lives

and the beast returns to the sea.

Bright morning are fragrant with spring

I learn a tongue which does not exist.

...(more)

_______________________

The Mind of the Modern: An Interview with Gabriel Josipovici

Victoria Best

(....)

VB: You’d already discovered the Modernist writers you loved and your relationship to them as a critic is clear. But what was your relationship to Modernism as a fledgling artist at this point? What did you hope to explore or elaborate in creative writing?

GB: The answer to the second question is: nothing. One writes because one has to, not to explore or elaborate anything. The answer to the first is, I suppose, that I had read Proust and Mann and Kafka, and Mann had made me understand that our modern situation is different from anything that has gone before, and fraught with difficulty; Kafka had made me understand that I was not alone in my sense of not belonging anywhere or having any tradition to call on; and Proust had given me the confidence to fail, had driven home to me the lesson that if you come up against a brick wall perhaps the way forward is to incorporate the wall and your effort to scale it into the work. I had read Robbe-Grillet and Marguerite Duras, and been excited by the way they reinvented the form of the novel to suit their purposes – everything is possible, they seemed to say. But when you start to write all that falls away. You are alone with the page and your violent urges, urges, which no amount of reading will teach you how to channel. ‘Zey srew me in ze vater and I had to svim,’ as Schoenberg is reported to have said. That is why I so hate creative writing courses – they teach you how to avoid brick walls, but I think hitting them allows you to discover what you and only you want to/can/must say. Not always of course. The artistic life is full of frustrations and failures as well as breakthroughs. You are alone. No-one can help you. I think that’s what Picasso means when he says that for Veronese it was simple: you mapped out the territory, started at one corner and worked forward. But for us, he says, the first brushstroke is also the last.

(....)

VB: Looking over your collected works and the experience I’ve had reading them, I’m reminded of Barthes and his comment that some of his best reading occurs with the book face down on his lap, staring into the middle distance. There is something so potent that happens when your writing comes into contact with my imagination. There’s a concept you may have heard of – the ‘unthought known’ – created by psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas. It refers to the immense store of knowledge that we own unwittingly, having never put it into words because we became aware of it in a wordless fashion. Bollas says: ‘There is in each of us a fundamental split between what we think we know and what we know but may never be able to think.’ Some of it will never be articulated and so, he says it’s important to ‘form a relationship to the mysterious unavailablity of much of our knowledge.’ And somehow, this is how I feel reading you. You take me towards the unthought places without ever speaking them yourself. It’s the spirit of the Between, if you like, who has his own chapter in Goldberg. Does that make any sense to you?

GJ: Yes, it makes a lot of sense. It’s what I look for in my writing, what I want to read and can’t find in the writing of others. I’ve never read Bollas, but what he says makes perfect sense to me. I wouldn’t even call it a ‘fundamental split’ – I think rather that our bodies know more than we do and that the task of art is to find forms and words that will allow the body to speak.

...(more)

Numéro Cinq A warm place on a cruel web

via Stephen Mitchelmore (Congratulations on and thanks for the last 15 years - mw)

_______________________

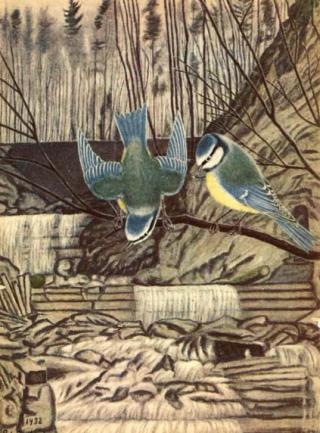

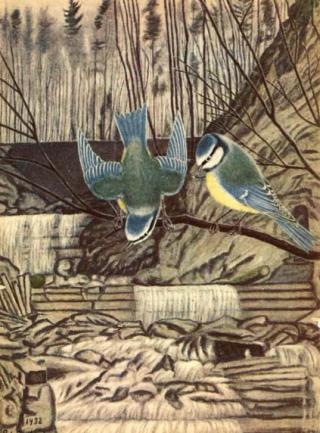

Glass Lantern Slides

Walter McClintock

_______________________

There's a certain Slant of light,

Winter Afternoons –

That oppresses, like the Heft

Of Cathedral Tunes –

Heavenly Hurt, it gives us –

We can find no scar,

But internal difference,

Where the Meanings, are –

None may teach it – Any –

'Tis the Seal Despair –

An imperial affliction

Sent us of the air –

When it comes, the Landscape listens –

Shadows – hold their breath –

When it goes, 'tis like the Distance

On the look of Death –

-

Emily Dickinson

_______________________

Ages of Monsters: Of Gods and Monsters

Larval Subjects

(....)

In glossing Lacan’s claim that the true formula of atheism is that God is unconscious, we should refer to the definition of the unconscious as the discourse of the Other. Lacan tirelessly repeats that the Other does not exist. The gods thus name those sites of the missed encounter where the symbolic and the system of anticipations and retentions break down. The gods refer to that which doesn’t work. Is this not exactly when we evoke the gods? Do we not evoke the gods precisely at that point where some improbable fortune, some impossible fortune, descends upon us or, conversely, where we suffer the bitter arrows of fate? We call upon them precisely in relation to the eruption of the impossible with the field of experience; the missed encounter.

The same could be said of monsters. Monsters are real, or rather belong to the field of the real. I’m not sure why I’ve been pre-occupied with monsters lately and I confess that my thoughts here are only half-formed; but it seems to me that the figure of the monster marks that place within cultural systems where the symbolic fails, where we have an encounter with the trauma of the real or materiality. The monster marks a site of excess within a symbolic or cultural order; that place where the order is disordered or goes awry. There is a sort of return of the repressed with respect to monsters, where the symbolic system bends back on itself and is encountered as defiling the pretensions of that order defining a world.

Here I wonder if there aren’t ages of monsters and, if so, what they might signify. Here, I add, that while these ages can be dated and periodized, none of theme ever really disappear. ...(more)

_______________________

Last Self Portrait

1956

David Bomberg

_______________________

Charnel ground

David Chapman

Many people reject Buddhist Tantra in favor of Consensus Buddhism, or modernized Theravada or Zen, because those seem realistic. These modernist Buddhisms sweep under the rug all the monsters, miracles, demons and deities of the Pali and Mahayana scriptures. Buddhism is supposed to be rational, scientific, and pragmatic.

Tantra, by contrast, seems incurably infested with magical superstitions.

I take the opposite view. Tantra is brutally realistic—because reality is brutal. It is Sutra (non-tantric Buddhism) that is a fantasy.

Sutra promises the path beyond all suffering. If you do everything right, you can escape this vale of tears into Neverland Nirvana.

Now there is a magical superstition. That fantasy runs far deeper than mere gods and demons. Spooks, after all, can be exorcized easily by declaring them to be psychological metaphors.

Tantra offers no salvation, no escape, no alternative, and no hope. Now that’s scientific, pragmatic, and sensible.

Many Western Buddhists implicitly imagine that Buddhism can somehow be The Answer To Life, The Universe, And Everything. Otherwise, we’d be totally fucked.

This is absurd. Life is diverse, and couldn’t have a single solution. Moreover, life is not a problem, so “solution” or “answer” is beside the point.

Anyway, we’re totally fucked. But existential optimism—“there must be a way out”—makes things worse than necessary. You waste effort chasing imaginary salvation, and keep feeling hurt when it doesn’t work out.

Tantra has an antidote.

It is a “practice of view,” which means developing the habit of interpreting the world in a particular way. Specifically, you view the world as a “charnel ground.”

Charnel grounds, in India, are places where unclaimed human corpses are dumped to rot, or be eaten. The bodies are not buried or burned; they are just left out. That’s a delightful buffet for the local carrion-eaters: jackals and hyaenas, tigers and bears, vultures and ravens.

Charnel grounds are dangerous, horrifying, chaotic places. None of the meat-eaters are picky about whether you are dead (except vultures). They are happy to eat living visitors. Unburied corpses also attract demons—in the Indian imagination—and are likely to produce ghosts and vetalas (zombies).

Sane, decent people avoid charnel grounds absolutely. That makes them ideal meeting places for dangerous, marginal people: brigands and spies, for instance, according to lore. Also dakinis (cannibal witches) and yogis (sorcerers): that is, tantric Buddhists.

A tantrika takes the same attitude to reality as to a charnel ground. Reality is a dangerous, horrifying, chaotic place. No one gets out of here alive.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

Randegg in the snow with ravens

Otto Dix

1891-1969

_______________________

Listening To The Darkness Sing

Judith Fitzgerald

(November 11, 1952 - November 25, 2015)

My tragedian of timeliness, mon maître de la mélancolie,

the heart breathes and you stand fastened, absorbing the world

huge as the hole in the night reclining on causeless ceaseways

where amazing grace swells and Hell's on the other side

of forever, for at least this moment, this lasting instant and all

the love, the need, the wanting of it all, now consonant,

now pacific, now the silent mother-of-pearl moon swirling,

tumbling down to kiss your wounded words, illuminated,

not simply by light, but the price of honouring the bearing

the soul – slashed by half yet seamlessly whole – bestows.

more poems

_______________________

Street Noise

Otto Dix

_______________________

e-flux journal issue 68:

“Cuba: The Fading of a Subcontinental Dream”

guest-edited by Coco Fusco

Editorial

Coco Fusco

(....)

It remains unclear whether the presence of foreign media is increasing public expression of critical views by Cuban artists, pushing the state’s hand in exercising control, or simply drawing international attention to the routine tussles between an authoritarian state and the citizens who for the most part enjoy a privileged status as long as their nonconformist tendencies are not perceived as politically inspired. The broader silence of the Cuban public as to their political aspirations and their opinions about culture still stands. Despite frequent media speculation as to what kind of political transitions Cubans may want for the future, there is a complete lack of regard for the history of attempts by Cuban intellectuals to advocate for the democratization of the Cuban system from within. In that sense, the Cuban government has succeeded in erasing history by classifying all political activism as illegal, mercenary, and counterrevolutionary, and by selectively omitting politically oriented art from institutionally produced histories.

The texts gathered in this issue of e-flux journal reflect upon the censorship of Cuban artists that has taken place in the shadow of the political negotiations between the island and the United States. They are the words of Cuban intellectuals who have chosen to respond to erasures brought about by overzealous state authority, a politics of complicity among Cuban artists, and the strategic blindness of Cuba’s enthusiasts.

...(more)

_______________________

Cats

Otto Dix

_______________________

QUE BESA SUS PIES, QUE BESA SUS MANOS

Judith Fitzgerald

To Edward Strickland

The delicate gorgeosity of your vital words,

each shimmering with irresistible possibility,

barely containing the truth catching in one's throat,

such exquisite intensity, the blackness each repudiates,

porous with damage and longing, indelibly sorrowstreaked

in one transparent universe where knives

of knowledge carve wide swaths through history,

luminous among moon's slow-dawning curves, now

arcing to pull you towards the radiance of darkness

serrated, swallowing pain, gasping for air

in those shadowed chambers of the heart yielding

to the contours of thinking skin in the perfect syntax

of stone and aether, grasping the universal finality

language's liquid purity salvages almost anything

but that, solves all conundra but that, that which

you cannot overcome, that cacophony of time wound up,

ground down, astounding in its irrefutable injury;

the circus of our love, its amusement-park attentions

spanning a millennium of, ultimately, swift midnights

(where the hands on the doomsway clock stand still

an instant, stand at attention, stand ready to embrace

whatever remains of a human face gone missing

without a trace). Hear that? It is cold; it is lethal;

and, it is threatening to break into itself in the name

of answers materialising on the horizon when the sun

rises to reveal dysphoria in all its splendorous glory.

That? Think crux. Think matter. Think father,

son, and wholly ghost-trace host. Think shatter.

Dusie 10: the Canadian issue

June 20 (solstice), 2010

Guest-edited by rob mclennan

_______________________

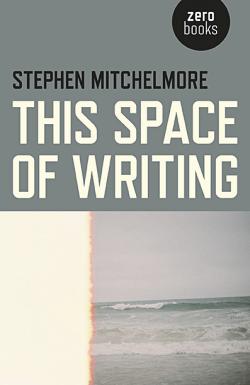

This Space of Writing

A renewed appreciation of the mystery and promise of writing.

Stephen Mitchelmore

Stephen Mitchelmore was the first literary-critical blogger, and has remained the best. His blog, This Space, ten years in existence, and commanding a wide readership, contains exquisite long-form meditations on literary fiction of the kind only the blogosphere can allow. Gathered here, Mitchemore's essays show a cumulative power, developing a philosophy of literature in a manner that recalls Blanchot's The Space of Literature.

~ Lars Iyer, author of Spurious and Wittgenstein Jr

This Space

_______________________

Encompassing Genius

Nicholas Roe reviews

Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake by Leo Damrosch

(....)

Eternity’s Sunrise is not a biography of Blake, although it is organised in chronological sequence. Blake’s early life, apprenticeship and various London residences are mapped, as is the country interlude at Felpham that led to his trial for ‘seditious utterance’. Damrosch also offers a caution, to the effect that Blake was ‘a troubled spirit, subject to deep psychic stresses, with what we would now call paranoid and schizoid tendencies’ – in today’s London, not someone to jostle accidentally on the Tube. Blake’s creative energies sprang from a ‘wounding sense of alienation and dividedness’ stemming, in part, from dislocations in his early childhood and estrangement from his brother John, whom he named ‘the evil one’. Throughout his poetry, family demons were blocking agents to be driven off by ‘arrows of thought’.

(....)

In Eternity’s Sunrise, Leo Damrosch captures Blake’s creativity in all its complexity, bringing to life his work as a poet, engraver and painter in a revolutionary age. A real strength of his book is the fine balance it achieves between Blake’s genius and his psychic troubles. I recall a conference twenty-five years ago at which the great scholar David Erdman was lecturing brilliantly on Blake’s poetry; in the audience his wife, Virginia, a distinguished clinical psychologist, leaned across to the person sitting next to her and observed, ‘I’ve never been able to convince David that Blake was completely mad.’

...(more)

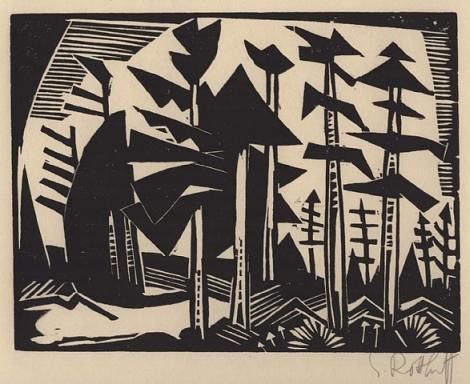

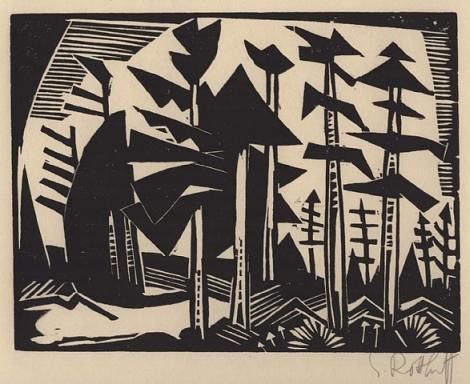

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

b. December 1, 1884

_______________________

A Walking Tour of Light

Leif Schenstead-Harris

I often become confused when faced with a text that asks me in to think about language and about struc- ture—neither an especially easy topic—and I find it helpful to walk when I’m confused, mindful of the duplicitous nature of confusion itself. Jacques Derrida, unhelpfully, offers a forked-tongue observation about the subject—or, at least, about confusion (that may be the subject of this tour): the “significance of ‘confusion’ is confused, at least double”. Two signifiers under one sign: the contending thoughts here are, at least, the confusion of tongues and the confusion of structures and communities, constructs Derrida later observes are themselves fluid. Since “no natural stability is ever given…there is only stabilization in process”. Process, movement, walking: on the subject of the Aran islanders, cartographer and writer Tim Robinson comments that his writing “will lead in their footsteps, not at their penitential trudge but at an inquiring, digressive, and wondering pace”. In similar fashion I walk and perversely do not think of how the name of confusion and the name of God are woven throughout the story of Babel. Rooney’s thoughtful Genesis raises questions of light, and I’ll follow those, or, at least, I’ll walk after them. Even though there is nothing spectacular about the present meandering of thought and feet, Derrida refuses to give me leave or peace: “Everything is done and everything happens while walking”. The worst of friends, as in Flann O’Brien’s Third Policeman: we go everywhere together, Derrida and I, since the beginning of my wandering career as a graduate student three years ago. (“And that is why John Divney and I became inseparable friends and why I never allowed him to leave my sight for three years,” O’Brien, 18.)

(....)

...

True thought, counterfeit thought, counterfeit true thought and truly counterfeit thought? In language these are difficult questions, and under the present light the questions become dim—the light is passing, Babel has fallen, and clamorous questions are being raised.

Perhaps the sun is not gone quite yet, however. These words I offer up as counterfeit: walk towards the light; head into the darkness. Fear no censors. Their doublespeak cannot regulate silence. But watch, with Cavafy’s carefully ironic Watchman at the turn of modernity, for the Atreids’ return:

The light is good; good are those en route;

and all they say and do is also good.

So let us pray things turn out well. And yet

Argos is capable of making do without

Atreids. Royal houses aren’t everlasting.

People, certainly, will be saying all sorts of things.

As for us, let’s listen. But we won’t be taken in

by ‘the Indispensable,’ by ‘the One and Only,’ by ‘the Great.’

They always find another straightaway

who’s indispensable, the one and only, the great.

The Word Hoard

Volume 1, Issue 1 (2012)

Community and Dissent _______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Lines for Winter

Mark Strand

1934–2014

for Ros Krauss

Tell yourself

as it gets cold and gray falls from the air

that you will go on

walking, hearing

the same tune no matter where

you find yourself—

inside the dome of dark

or under the cracking white

of the moon's gaze in a valley of snow.

Tonight as it gets cold

tell yourself

what you know which is nothing

but the tune your bones play

as you keep going. And you will be able

for once to lie down under the small fire

of winter stars.

And if it happens that you cannot

go on or turn back

and you find yourself

where you will be at the end,

tell yourself

in that final flowing of cold through your limbs

that you love what you are.

_______________________

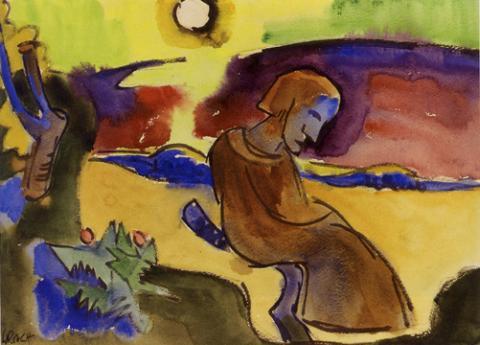

Russian Landscape with Sun

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

1919

_______________________

Climate Change and Apocalypticism: A Hope Indistinguishable from Nihilism

Thomas Lynch

An Und Für Sich

In the course of addressing climate change, like so many other crises, we are confronted with the demand to hope. We must hope in the future, for without the future we are lost. Refusing to hope, in the form of pessimism or resignation, is to not only abandon the myth of perpetual progress, but to throw into question the fabric of society. Against this demand for hope, I am going to argue for an apocalyptic response. In what follows, I’ll briefly outline a definition of apocalypticism, drawing primarily on the work of Jacob Taubes and Catherine Malabou, before moving on to discuss this approach as a response to climate change. I’ll conclude by discussing why this apocalyptic perspective is incompatible with the idea of the Anthropocene, an increasingly popular way of framing the issue of climate change.

(....)

Climate change exposes a fundamental antagonism between some humans and nature. This antagonism structures the reality of all humans, even those who, alongside the nonhuman, disproportionately suffer the consequences of this antagonism. Within this antagonism, we can hope, but in so doing, we hope for the destruction of one side of the antagonism. There is a potential for something new to emerge, and, following Bloch, this potential novelty is a source of hope. Yet as Malabou shows, this newness emerges from trauma. In considering that possible future, we must become apocalyptic – we can only hope with a hope indistinguishable from nihilism.

...(more)

_______________________

Theory for the Anthropocene

a lecture with Roy Scranton, Stephanie Wakefield, and McKenzie Wark

_______________________

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

_______________________

Culture of Cruelty: the Age of Neoliberal Authoritarianism

Henry A. Giroux

(....)

Underlying the rise of the authoritarian state and the forces that hide in the shadows is a politics indebted to promoting historical and social amnesia. The new authoritarianism is strongly indebted to what Orwell once called a “protective stupidity” that negates political life and divest language of its critical content.[4] Neoliberal authoritarianism has changed the language of politics and everyday life through a malicious public pedagogy that turns reason on its head and normalizes a culture of fear, war, surveillance, and exploitation. That is, the heavy hand of Orwellian control is evident in those dominant cultural apparatuses that extend from schools to print, audio, and screen cultures, which now serve as disimagination machines attacking any critical notion of politics that makes a claim to be educative in its attempts to enable the conditions for changing “the ways in which people might think critically.”

(....)

The discourse of possibility not only looks for productive solutions, it also is crucial in defending those public spheres in which civic values, public scholarship, and social engagement allow for a more imaginative grasp of a future that takes seriously the demands of justice, equity, and civic courage. Democracy should encourage, even require, a way of thinking critically about education, one that connects equity to excellence, learning to ethics, and agency to the imperatives of social responsibility and the public good. Casino capitalism is a toxin that has created a predatory class of unethical zombies–who are producing dead zones of the imagination that even Orwell could not have envisioned –all the while waging a fierce fight against the possibilities of a democratic future. The time has come to develop a political language in which civic values, social responsibility, and the institutions that support them become central to invigorating and fortifying a new era of civic imagination, a renewed sense of social agency, and an impassioned international social movement with a vision, organization, and set of strategies to challenge the neoliberal nightmare engulfing the planet. These may be dark times, as Hannah Arendt once warned, but they don’t have to be, and that raises serious questions about what educators, artists, youth, intellectuals, and others are going to do within the current historical climate to make sure that they do not succumb to the authoritarian forces circling American society, waiting for the resistance to stop and for the lights to go out. History is open and as James Baldwin once insisted, “Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

...(more)

|