|

photo - mw

_______________________

I would prefer not to

On not-doing … — a triptych

Jeremy Fernando berfois

(....)

Quite a few thinkers — Giorgio Agamben and Slavoj Žižek amongst them — have attempted to read Bartleby’s response as a form of passive resistance. Their claim is that his response, that is always also a non-response, short-circuits the system. If he had out-rightly rejected Mr B there would have been an immediate expulsion, firing: “had there been the least uneasiness, anger, impatience or impertinence in his manner; in other words, had there been anything ordinarily human about him, doubtless I should have violently dismissed him from the premises.” The trouble was, as Mr B continues, “there was something about Bartleby that not only strangely disarmed me, but in a wonderful manner, touched and disconcerted me.” And here, Mr B makes what one might call a fatal error: “I began to reason with him.”

Whilst most readings, readers, focus on Bartleby, perhaps we should momentarily turn out attention to the other interlocutors, those that are attempting to elicit not just a response but a particular act, action, from him. I — allowing all echoes of the unjustifiability of my choice — would like to propose that they were unable to move him, influence his actions, have power over him if you prefer, as they structured their statements as requests. Not only did they open the possibility of non-compliance, it was a far more fundamental mistake: requests function on the logic that both parties involved are operating under the same rules, form, customs, reason — in other words, the exchange is one that involves pre-set options, and not actual choices. That in a situation, to echo Mr B, “a slight hint would suffice — in short, an assumption.” The assumption being that the one receiving the address would know what, even the right thing, to do.

Perhaps then, what is truly subversive about Bartleby’s response is that it takes Mr B’s questions seriously; takes it as a question which offers the potential for a true response. And by doing so, Bartleby challenges authority to reveal itself — to not hide behind the illusion that it is offering a choice. That even as Mr B thinks otherwise, authority is no more than “vulgar bullying.”

In other words, what Bartleby does is to challenge daddy to show himself.

...(more)

_______________________

Watercolours from a 16th-Century De Materia Medica

_______________________

Zero

Larval Subjects

(....)

Consciousness is zero. It is that which is non-identical to itself and that is condemned to be non-identical to itself. I wonder if this is how it is for my dog and my cats and for octopi? Is it like this for elephants? Do they experience themselves as a non-identity with themselves? Consciousness is a razors edge, a perpetual shift. Consciousness is not a substantiality, the ego, or an identity. It is the non-identity that is in excess of any mirror image, ego, or identity. It is the perpetual failure of these things. J.A. Miller. Suture. Matrix. This is the burden of the past. The past weighs on us because of what we have done, who we have been. It’s etched. But there would be a comfort in being able to be our past like the grape that has grown from its soil. No, perhaps the worst thing about the past is that we are zero or the number that is non-identical to itself. Difference. We always fail to be our past. I will never be as great as I was in my past, nor as terrible. I will never be that person that wrote those things, said those things, thought those things, did those things. That was another self. I will always be fallen from that past, and each time yet again. Will I ever write as well again? I am this strange zero that both is this past, but is not it. We can eat our madeleine cakes, yet we will not regain the past. We are that past, yet are not it. It weighs on us, instituting a gravitational pull. We are caught in our signifiers, in what we have said. Yet we somehow can’t be them. We are a shift, a perpetual disadequation, a being non-identical to ourselves.

...(more)

_______________________

Plates from Robert Thornton’s Temple of Flora (1807)

_______________________

Writers Writing Dying

CK Williams

Many I could name but won’t who’d have been furious to die while they were sleeping but did—

outrageous, they’d have lamented, and never forgiven the death they’d construed for themselves

being stolen from them so rudely, so crudely, without feeling themselves like rubber gloves

stickily stripped from the innermostness they’d contrived to hoard for themselves—all of it gone,

squandered, wasted, on what? Death, crashingly boring as long as you’re able to think and to write it.

Think, write, write, think: just keep galloping over the hurdles and you won’t notice you’re dead.

The hard thing’s when you’re not thinking or writing and as far as you know you are dead

or might as well be, with no word for yourself, just that suction-shush like a heart pump or straw

in a milkshake and death which once wanted only to be sung back to sleep with its tired old fangs

has me in its mouth!— and where the hell are you that chunk of dying we used to call Muse?

Well, dead or not, at least there was that dream, of some scribbler, some think- and write- person,

maybe it was even yourself, soaring in the sidereal void, and not only that, you were holding a banjo

and gleefully strumming, and singing, jaw swung a bit under and off to the side the way crazily

happily people will do it—singing songs or not even songs, just lolly-molly syllable sounds,

and you’d escaped even from language, from having to gab, from having to write down the idiot gab.

But in the meantime isn’t this what it is being dead, with that Emily-fly buzzing on your snout

that you’re singing as she did, so what matter if you died in your sleep, or rushed toward dying

like the Sylvia-Hart part of the tribe who ceased too quickly to be and left out some stanzas?

So what? You’re still aloft with your banjoless banjo, and if you’re dead or asleep who really cares?

Such fun to wake up though! Such fun too if you don’t! Keep dying! Keep writing it down!

via the page

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Benjamedia

McKenzie Wark

public seminar

Walter Benjamin has a reputation as a sophisticated reader of literary texts. But perhaps his media theory is not quite so elaborate. Here I shall attempt to boil it down in a very instrumental way. The question at this juncture might be less what we owe this no longer neglected figure but what he can do for us.

Benjamin thought that there were moments when a fragment of the past could speak directly to the present, but only when there was a certain alignment of the political and historical situation of the present that might resonate with that fragment. Applying this line of thought to Benjamin himself, we can wonder why he appeared to speak directly to critics of the late twentieth century, and whether he still speaks to us today.

(....)

After discussing him with my students, we came to the conclusion that one could thing of, and use, all of Benjamin’s methods as ways of detecting the historical unconscious working through the tensions within cultural artifacts. Benjamin can be a series of lessons in which artifacts to look at, and how to look. One can look for the fragment of the past that speaks to the present. One can look within the photograph for the optical unconscious at work. One can look at obsolete forms, where the tension between past and dreamt future is laid bare. One can look at avant-gardes, which might anticipate where the blockage is in the incomplete work of history. One can look at the low or the kitsch, where certain dream-images are passed along in a different manner to fine art.

Our other thought was that one thing that seems to connect Benjamin to the present even more than the content of his writing is the precarity of his situation while writing it. Like Baudelaire and the bohemian flaneur, his is in contemporary terms a ‘gig economy’, of freelance work and of permanent exclusion from security. This precarity seemed to wobble on the precipice of an even greater, and more ostensibly political one — the rise of fascism. Today, the precarity of so many students, artists, traders in new information — the hacker class as I call it — seems to wobble on the precipice of an ecological precarity. If in Benjamin’s day it was the books that were set on fire, now it is the trees.

...(more)

Là-bas [excerpt]

Chantal Akerman

1950 - 2015

youtube

"I ’ve thought of her film work as philosophy. And by this I don’t mean that it just embodies previously published philosophical ideas, but that it actually realizes a historically innovative philosophical contribution."

Chantal Akerman’s Là-bas: The Suspended Image and the Politics of Anti-Messianism

Chrysanthi Nigianni It is this double exigency-recognition of the closure of the political and practical deprivation of philosophy as regards itself and its own authority– which leads us to think in terms of re-treating the political. This phrase is taken here at least in two senses: first, withdrawing the political in the sense of its being the ‘well-known’ and in the sense of its obviousness (the blinding obviousness) of politics, the ‘everything is political’ which can be used to qualify our enclosure in the closure of the political; but also as re-tracing of the political, re-marking it, by raising the question in a new way which, for us, is to raise it as the question of its essence.

– Jean-Luc Nancy and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe

When everything has been said, when the main scene seems over, there is what comes afterwards…

– Antonioni

(....)

Chantal Akerman’s film work is an exploration of time, movement and space. The deliberate stillness of her image puts into crisis our ‘natural’ perception and subsequently our conception of movement and time gets disturbed. Long takes, stubborn fixedness and a camera that stares produce another ‘seeing’ and a sense of additional reality (rather than a description of what already exists). As Jacques Derrida has argued: ‘One can only be blind to time, the essential disappearance of time, even as, nevertheless, in a certain manner, nothing appears that does not require and take time”.

If our sense of reality, all appearance and disappearance, is based on the disappearance of time, Akerman’s cinema by giving time the leading role, by making it visible, creates a monstrous (non-human) image of an additional reality: an image that occasionally becomes unbearable, a too much to bear for our common perception; an image that paralyses vision commonly understood as orientation and action and that invites instead intuition, in the Bergsonian sense of a deep apprehension of duration.

...(more)

still from Là-bas

Chantal Akerman

Postscript: Chantal Akerman

Richard Brody

_______________________

Translating Indigenous Mexican Writers:

An Interview with Translator David Shook

asymptote

(....)

Speaking of linguistics: the book clearly serves as both a book of poetry on its own right, but also as a learning tool. Each introduction features a brief introduction to the language, including its linguistic qualities; there is even an online study guide for the book. Phoneme Media itself, of course, borrows a linguistic term for its title.

Though most readers won’t be able to engage much with the original languages, we wanted to pay them their due as a symbol of respect and admiration. Víctor has done a lot to promote the book’s publication in Juchitán. For him, it’s a part of his language activism.

He has campaigned to revitalize the Isthmus Zapotec language by encouraging and inspiring the youth to use it in everyday life as well as in the arts. To him, it’s an important sign of prestige for the community, to show that their language is appreciated outside of their own region. And that the everyday linguistic oppression they might feel from the Spanish language can be circumvented and challenged.

I suspect many casual bookstore readers might not know how many languages are still spoken in Mexico. The sheer diversity is astounding. And to realize the quality of work being written in these languages is even more astounding. There’s so much great work that we couldn’t fit!

...(more)

Like a New Sun, a collection of contemporary indigenous Mexican poetryedited by David Shookand Víctor Terán.

Like a New Sun

Eliot Weinberger

(....)

In recent decades, there has been an extraordinary new development in Mexico’s indigenous literatures. Bilingual writers, educated in Spanish and conversant in Western modernism, are choosing to write in their native languages. As these are contemporary writers, their poetry and fiction is disseminated orally not only in live performance but also on radio shows, and, for the first time in these histories, in books and language-specific magazines. Some of the poets in this book use their native language as a way of enriching the modernist lyric. Others use modernism to re-imagine traditional forms.

What is happening in Mexico is being mirrored in many other countries where indigenous languages survive. It is partially a matter of ethnic pride. In the globalizing world, there is a countercurrent that is emphasizing the local, celebrating what is different in the face of the monoculture, adapting the old ways in an era of relentless novelty. But it is also a culmination of modernism itself, the rallying cry of which was Joyce’s “Here Comes Everybody.” Twentieth century painting and sculpture is inextricable from its discovery of new forms in African and Native American art, or the stories, poems, and myths of tribal cultures that permeate modern literature. (For some decades there was, in France, a very blurred line between the Surrealist and the anthropologist.) Yet this was, in the last century, all one-directional: the indigenous feeding the cosmopolitan West. We are now at a moment—still in its early stages—where inspiration is flowing the other way. As this book demonstrates, the poetry written in Spanish, English, and French is one part of a complex of ideas and perceptions that is invigorating new ways of writing in Mazatec, Zapotec, Zoque, and Nahuatl, which may in turn lead to something else, somewhere else.

...(more)

_______________________

Serge Poliakoff

1900 - 1969

_______________________

Learning How to Die in the Anthropocene

Roy Scranton

(....)

Geological time scales, civilizational collapse and species extinction give rise to profound problems that humanities scholars and academic philosophers, with their taste for fine-grained analysis, esoteric debates and archival marginalia, might seem remarkably ill suited to address. After all, how will thinking about Kant help us trap carbon dioxide? Can arguments between object-oriented ontology and historical materialism protect honeybees from colony collapse disorder? Are ancient Greek philosophers, medieval theologians, and contemporary metaphysicians going to keep Bangladesh from being inundated by rising oceans?

Of course not. But the biggest problems the Anthropocene poses are precisely those that have always been at the root of humanistic and philosophical questioning: “What does it mean to be human?” and “What does it mean to live?” In the epoch of the Anthropocene, the question of individual mortality — “What does my life mean in the face of death?” — is universalized and framed in scales that boggle the imagination. What does human existence mean against 100,000 years of climate change? What does one life mean in the face of species death or the collapse of global civilization? How do we make meaningful choices in the shadow of our inevitable end?

These questions have no logical or empirical answers. They are philosophical problems par excellence. ...(more)

_______________________

Serge Poliakoff

_______________________

initial sketches on precision neuronihilism

Annihilating Unity

Subtlety grates upon the nerves, yet everything is driven by an immense crudity: death impassions us. Even before crossing over into death I had been excruciated upon my thirst for it. I accept that my case is in some respects aberrant, but what skewers me upon zero is an aberration inextricable from truth. To be parsimonious in one’s love for death is not to understand. -Nick Land, Thirst for Annihilation

This essay will likely seem serpentine, obscure, and repetitive, as I attempt to tie various speculations together that are, at the end of the day, just that - speculations. The reason I persist despite this limitation is that I believe the tools and technology exist and have always existed to plumb this particular depth in order to prove these theories right or wrong - my conjecture is it is universal, though time will tell. Perhaps it will spark anyone else to consider the possibilities contained herein and not be daunted by the solemnity and ghoulishness of Nothing! I am not the first to have foreseen an end to blind threading of the weave of world-space. I am not the first to "gaze long into the Abyss", nor am I the first to discover that our personal abysses can reflect the individuated Self. I am not the first to unwind and add my own Ariadne's thread through this intimate enfolding of Trauma and Time. I am not the first to attempt an Escape from this Mirror Maze, nor the first to theorize a mechanism for its navigation. I am not the first to swim up out of the hedgerow labyrinth into the ocean of Void. Nor am I the first to have brought back a vision of our underworld from the perspective of this "positive death at zero-intensity": a vision of infinitely multifold reflecting crystalline geometries hung on silver string in the aether. Like hyperconnected wireframe constellations, each node a virtual mirror - pages in books on shelves in the infinite librarynth of Self. To update Nietzsche: I have a multiplicity of precursors, and what a unity these precursors construct! No less than proof that the simulation of external reality by mind can be turned off completely or simulated as such, that this deactivation exposes details of future states, and that all recorded memory states are experienced simultaneously within this form of pure consciousness, coextensive with incoming sensory input. Mors mystica - the experiencing of the Real in real time - exposes and forces a visualization of the calculatory procedures undertaken by the brain.

...(more)

via -synthetic zero

photo - mw

_______________________

The (R)evolutionary Vision and Contagious Optimism of Grace Lee Boggs

Barbara Ransby

Grace Lee Boggs died yesterday at the age of 100 and the world is better for the century that she walked it with us. As a writer, insurgent intellectual, revolutionary organizer, mentor, community builder and friend to many, Grace will be dearly missed.

When I was a teenager in Detroit and a wannabe revolutionary in the 1970s I heard the names Grace and Jimmy Boggs all the time. I knew they were beloved and respected in Detroit’s Black activist community, and I just assumed they were both Black. I was surprised to finally meet Grace and discover she was Chinese-American. I had to recalibrate my notions about the Black struggle, “my people” and race itself.

Long after many of Detroit’s young black revolutionaries left Detroit and the revolution, Grace stayed. She was so immersed in the life and struggles of Detroit’s predominately Black communities that she said her FBI file described her as “probably Afro-Chinese.” Alongside her partner in life and politics, former auto-worker and black activist and leader, Jimmy Boggs (who died in 1993), Grace fought the good fight over five decades, writing books, building organizations, organizing campaigns, and teaching by example that “revolution” is a protracted process—not a single event or a spate of protests. She saw the Black struggle as the cutting-edge struggle of her lifetime, intricately linked to many others, and she was humbled to be a part of it.

...(more)

Grace Lee Boggs

1915 - 2015

(Photo: Ryan Garza)

Grace Lee Boggs' 100th birthday celebrated in Detroit

_______________________

Interview with Jill Stauffer, author of Ethical Loneliness

I wrote Ethical Loneliness in response to a gap I felt in discussions people were having in various settings about how to respond to harm. Political reconciliation, transitional justice, political forgiveness and apology, legal adjudication of mass violence, truth commissions, international courts—all these are ways of responding to harm, focused to varying degrees on a discourse of repair. And yet it seemed to me that often, in conversations about these important forms of response, some things were being left unsaid. Forests were being discussed, but trees neglected, I might say. In all these discussions of repair, I kept finding too many moments where institutions designed to hear failed to listen well, and so also failed those they were most meant to serve.

So I set out to try to put a name to this thing that seemed to slip through the cracks of current conversation. I found my way to an answer when I started reading the writings Jean Améry, a holocaust and concentration camp survivor famous for defending the political value of resentment over forgiveness. Reading his work while thinking about Emmanuel Levinas’ early phenomenology—written while held in a forced labor camp during WWII—led me to come up with the term “ethical loneliness,” a name for a double abandonment. Ethical loneliness is the experience of being abandoned by humanity compounded by the experience of not being heard when you testify to what happened.

(....)

... I asked myself how it could be that “bad hearing” was so widespread. And I came to the thought that at least part of the problem resides in the stories we (those of us who care about justice and believe it ought to be fairly equally distributed) tell ourselves about what we owe and how we come to owe it. We want to believe in liberal political theory’s tale of autonomy not only because, for many of us, we find it all around us as we get formed as people—it is a prevalent story. But we also want to believe in a simplified autonomy because it can be too frightening to admit that, just as we were made into who we are by lots of forces beyond our control, including our fellow human beings, we can be destroyed by other human beings. Meaningful autonomy only exists where there are others who will respect its boundaries. And much of what keeps some safe while others get harmed is moral luck, nothing earned or deserved. It can be terrifying to think it, but I see no way out of that truth.

And so we tell ourselves that we are only responsible for what we’ve done and intended, and perhaps we also believe that people get what’s coming to them. But we forget to reason our way to the conclusion that comes from that starting point: that our aspirations toward a better justice will remain unrealized if that’s the story we tell ourselves about responsibility.

...(more)

via flowerville

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Saying It To Keep It From Happening

John Ashbery

Some departure from the norm

Will occur as time grows more open about it.

The consensus gradually changed; nobody

Lies about it any more. Rust dark pouring

Over the body, changing it without decay—

People with too many things on their minds, but we live

In the interstices, between a vacant stare and the ceiling,

Our lives remind us. Finally this is consciousness

And the other livers of it get off at the same stop.

How careless. Yet in the end each of us

Is seen to have traveled the same distance—it’s time

That counts, and how deeply you have invested in it,

Crossing the street of an event, as though coming out of it were

The same as making it happen. You’re not sorry,

Of course, especially if this was the way it had to happen,

Yet would like an exacter share, something about time

That only a clock can tell you: how it feels, not what it means.

It is a long field, and we know only the far end of it,

Not the part we presumably had to go through to get there.

If it isn’t enough, take the idea

Inherent in the day, armloads of wheat and flowers

Lying around flat on handtrucks, if maybe it means more

In pertaining to you, yet what is is what happens in the end

As though you cared. The event combined with

Beams leading up to it for the look of force adapted to the wiser

Usages of age, but it’s both there

And not there, like washing or sawdust in the sunlight,

At the back of the mind, where we live now.

Doorstep in the Wind: 30 Great John Ashbery Poems

selected by Matthew Zapruder

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

The Man on the Dump

Wallace Stevens

Day creeps down. The moon is creeping up.

The sun is a corbeil of flowers the moon Blanche

Places there, a bouquet. Ho-ho ... The dump is full

Of images. Days pass like papers from a press.

The bouquets come here in the papers. So the sun,

And so the moon, both come, and the janitor’s poems

Of every day, the wrapper on the can of pears,

The cat in the paper-bag, the corset, the box

From Esthonia: the tiger chest, for tea.

(....)

That’s the moment when the moon creeps up

To the bubbling of bassoons. That’s the time

One looks at the elephant-colorings of tires.

Everything is shed; and the moon comes up as the moon

(All its images are in the dump) and you see

As a man (not like an image of a man),

You see the moon rise in the empty sky.

One sits and beats an old tin can, lard pail.

One beats and beats for that which one believes.

That’s what one wants to get near. Could it after all

Be merely oneself, as superior as the ear

To a crow’s voice? Did the nightingale torture the ear,

Pack the heart and scratch the mind? And does the ear

Solace itself in peevish birds? Is it peace,

Is it a philosopher’s honeymoon, one finds

On the dump? Is it to sit among mattresses of the dead,

Bottles, pots, shoes and grass and murmur aptest eve:

Is it to hear the blatter of grackles and say

Invisible priest; is it to eject, to pull

The day to pieces and cry stanza my stone?

Where was it one first heard of the truth? The the.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Like a Sentence

John Ashbery

How little we know,

and when we know it!

It was prettily said that “No man

hath an abundance of cows on the plain, nor shards

in his cupboard.” Wait! I think I know who said that! It was . . .

Never mind, dears, the afternoon

will fold you up, along with preoccupations

that now seem so important, until only a child

running around on a unicycle occupies center stage.

Then what will you make of walls? And I fear you

will have to come up with something,

be it a terraced gambit above the sea

or gossip overheard in the marketplace.

For you see, it becomes you to be chastened:

for the old to envy the young,

and for youth to fear not getting older,

where the paths through the elms, the carnivals, begin.

(....)

Time has only an agenda

in the wallet at his back, while we

who think we know where we are going unfazed

end up in brilliant woods, nourished more than we can know

by the unexpectedness of ice and stars

and crackling tears. We’ll just have to make a go of it,

a run for it. And should the smell of baking cookies appease

one or the other of the olfactory senses, climb down

into this wagonload of prisoners.

The meter will be screamingly clear then,

the rhythms unbounced, for though we came

to life as to a school, we must leave it without graduating

even as an ominous wind puffs out the sails

of proud feluccas who don’t know where they’re headed,

only that a motion is etched there, shaking to be free.

...(more)

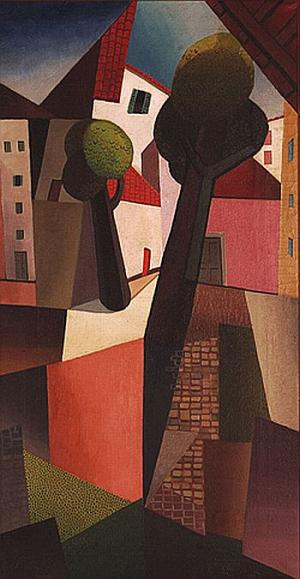

Painter

Emil Filla

1882 - 1953

_______________________

Radio and Child: Walter Benjamin as Broadcaster

Brían Hanrahan

(....)

Any serious history of children and radio — any history going beyond a chronicle of program offerings — must include the German writer Walter Benjamin. Benjamin wrote extensively for the radio, and most of those broadcast writings — now newly translated and collected — were written for children, at least at first glance. More than that, something quintessentially Benjaminian happens in that uncanny encounter of radio and child: the hint of an unsettling remainder in the everyday, in the dislocation of sent message and received meaning, in the figure of the child who knows something his parents do not.

...(more)

_______________________

Brief Report To An Academy

Durs Grünbein

Translated from the German by John Crutchfield, Michael Hofmann, and Andrew Shields

(....)

What happened then was a cheerful childhood spent in the provinces, where the emphasis soon came to fall on spent; in other words, the thing was pretty soon over. To this day, I have been unable to shake the conviction that when you throw open your arms to clasp life, you are caught up in the wind and are blown backward into the future, and each successive period is less magnificent than the one before, so that the feeling of loss is pretty soon immeasurable. Nor is the end any consolation, it's just a limit set to this infinitesimal quotient of happiness.

(....)

However overwhelming the experience of the end of the Soviet empire was, it became fertile for me only five years later, in Italy, when I was visiting the sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Only there did I see the effect of that massive explosion called time, the delayed rain of shards of civilization, and, in the famous calamity, under the volcano, evidence of a kind of memoryless memory—deus absconditus, or whatever you want to call it. Poetry, as I always knew it would, would get on the case—what else was it there for? In the house of charred furniture I paused, for hours all historical agitation was suspended, calmed by the murals in the mystery villa. In those small rooms—no bigger than a pigsty, some of them—with their scribbled lines of poems, obscenities, and decorative drawings, I felt myself better understood than in all the classrooms, barracks, and attics that had ever held me. Then, at the sight of the anonymous fresco representing dream and birth, the entanglements of sex and knowledge, ages and seasons, I had an illumination of what writing, above and beyond anything current, might be all about.

...(more)

via flowerville

Durs Grünbein’s The Bars of Atlantis

Reviewed by André Naffis-Sahely

The Bars of Atlantis: Selected Essays

Durs Grünbein

google books

_______________________

Ebb Tide, Rye

(1918)

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson

d. October 7, 1946

_______________________

Postcapitalist Futures

Daniel Whittall reviewing Paul Mason, Postcapitalism: A Guide to our Future, Nick Dyer-Witheford, Cyber-proletariat: Global Labour in the Digital Vortex and Alberto Toscano & Jeff Kinkle, Cartographies of the Absolute

(....)

Mason and Dyer-Witheford both offer attempts to map capital’s current functioning, to reconstruct the social struggles at its heart, and to chart its future. Mason believes that the complete modelling of capitalism in all its complexity is both possible and desirable and, appropriately enough, that it can be computed using mathematical modelling. What we need, he argues, is ‘an open, accurate and comprehensive computer simulation of current economic reality.’ Dyer-Witheford, too, longs for an image that could capture capital whole, asking ‘where today are the images of the cybernetic systems which this proletariat labours to build, and with which it is being replaced?’ The answer to this question can be found, in part, in Alberto Toscano and Jeff Kinkle’s Cartographies of the Absolute. Toscano and Kinkle seek to divine ‘an aesthetics in and against capital’ by inquiring into what it means to create ‘a cultural and representational practice adequate to the highly ambitious … task of depicting social space and class relations in our epoch of late capitalism or postmodernity’ (their debt to Fredric Jameson is openly acknowledged here). This fine book pursues its object through studies of diverse aesthetic projections of the world as made by capital, discussing modes of representation as diverse as the industrial and oceanic photography and films of Allan Sekula to 1970s cult werewolf movies; from The Wire to Wall Street via critical docu-dramas like Inside Job; from the art and image of logistics to that of living, and dying, labour.

Toscano and Kinkle’s attempt to analyse what they call the impulse to cognitively map capitalism in its totality centres around ‘the problem of visualising and narrating capitalism today.’ Because ‘mapping is above all a practical task,’ its invocation gives ‘a more concrete cast, a rooting in everyday life’ to the efforts of those who attempt it. For the critic of any attempt to cognitively map global capitalism, the task is to ‘tease out the symptoms of, at one and the same time, the consolidation of a planetary nexus of capitalist power and the multifarious struggles to imagine it.’ We might read both Mason and Dyer-Witheford as being involved in this project of cognitively charting the dynamics of contemporary capitalism in order to produce route-maps of the way forward. Ultimately, though, Toscano and Kinkle conclude that any attempt to understand capitalism in a manner that might be productively deployed to challenge it must, of necessity, be both partial and partisan:

Overview, especially when it comes to capital, is a fantasy … there is in the end something reactionary about the notion of a metalanguage that could capture, that could represent, capitalism as such.

...(more)

Review 31_______________________

Glass and newspapers

Emil Filla

_______________________

from Godhavn

Iben Mondrup

translated by Kerri Pierce

asymptote - tranlation tuesday

(....)

Into the water with it. Of course, it floats; styrofoam never sinks. Instead, it just crumbles into billions of tiny white pellets that wash ashore and collect between the rocks. Their styrofoam slabs are good and solid.

“You first,” René says. “Tell me where we are now.”

The lake with its rocks and hollows no longer has anything to do with Godhavn. No sooner have Knut and René heaved the raft into the water than they are on a strange continent, where animals they’ve never read about frolic in the waves, flit about the rocks, completely indifferent to the boys’ presence. They’ve never seen humans before. “We’re way back in time,” Knut says, “endlessly far.”

“Look!” René shouts and points to something that is undoubtedly the catfish’s distant ancestor, a torpedo-shaped being with six legs and leopard spots and a great grinning mouth. “Look!” he shouts and points to another creature, an udderless, walrus-toothed cow. “Look!” he shouts – and he shouts it again and again.

From the shore, Knut tries as best he can to write it all down, to capture all their observations in the logbook; everything here, what a world, so big and ancient, there’s no one who understands it, who knows it, other than the two of them, the two boys in on the game.

“When we get home,” Knut calls back to him, “we’ll look at the water samples under the microscope. I think we’ve got the origin of the world here. I have it in the cup.”

René paddles back as quickly as his broken oars allow. “I think we should’ve sewn a sail for the raft,” he says when he finally nears the shore. “Let’s see here.”

He grabs the cup and adjusts his lorgnette. “Just like I thought,” he says. “The origin of species.”

“Let’s not tell anyone,” Knut says. “This place needs to stay untouched.”

“But we’re already here,” René replies. “What about us?”

...(more)

_______________________

Sandy Path

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson

photo - mw

Well ...15 years old today.

Once again thanks for your interest and support

- especially those of you who have been following the "s lot" since the early days —rmw _______________________

The Moose

Elizabeth Bishop

d. October 6, 1979

For Grace Bulmer Bowers

From narrow provinces

of fish and bread and tea,

home of the long tides

where the bay leaves the sea

twice a day and takes

the herrings long rides,

where if the river

enters or retreats

in a wall of brown foam

depends on if it meets

the bay coming in,

the bay not at home;

where, silted red,

sometimes the sun sets

facing a red sea,

and others, veins the flats’

lavender, rich mud

in burning rivulets;

on red, gravelly roads,

down rows of sugar maples,

past clapboard farmhouses

and neat, clapboard churches,

bleached, ridged as clamshells,

past twin silver birches,

through late afternoon

a bus journeys west,

the windshield flashing pink,

pink glancing off of metal,

brushing the dented flank

of blue, beat-up enamel;

down hollows, up rises,

and waits, patient, while

a lone traveller gives

kisses and embraces

to seven relatives

and a collie supervises.

(....)

Moonlight as we enter

the New Brunswick woods,

hairy, scratchy, splintery;

moonlight and mist

caught in them like lamb’s wool

on bushes in a pasture.

The passengers lie back.

Snores. Some long sighs.

A dreamy divagation

begins in the night,

a gentle, auditory,

slow hallucination....

...(more)

_______________________

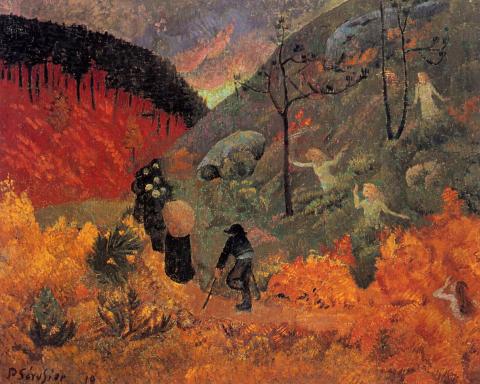

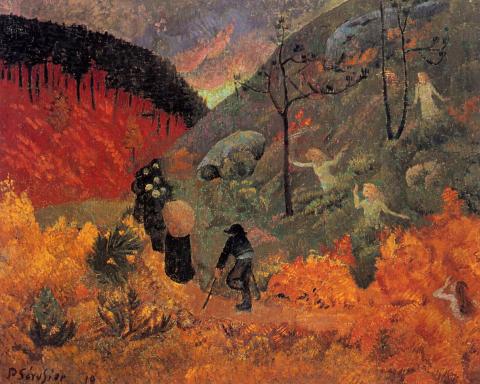

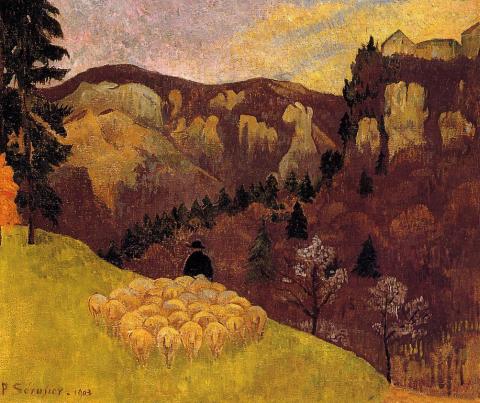

The Talisman

the Aven River at the Bois d'Amour

October 1888

Paul Sérusier

1864-1927

_______________________

The truth according to Brian Friel

Fintan O'Toole

(....)... “there is no lake along that muddy road. And since there is no lake, my father and I never walked back from it in the rain with our rods across our shoulders. The fact is a fiction.”

Yet – and this is the centre of Friel’s work – this realisation that memories may be inventions does not deprive them of their force.

Friel liked a quote from Oscar Wilde about the “inalienable privilege” of the artist to “give an accurate description of what has never happened”.

Truths, for him, were not mere facts. Of this false memory he insisted, “For me it is a truth. And because I acknowledge its peculiar veracity it becomes a layer in my subsoil; it becomes part of me; ultimately it becomes me.”

In Philadelphia, that first great play, Friel’s own real memory is transported into his fictional character’s memory, and there, too, it proves illusory. Yet the very power with which it is evoked on stage lifts it into a different kind of reality. It makes its own truth. That trajectory, from reality to fiction to shattered illusion and back to a sort of heightened presence, is the journey of a Friel play.

And the journey is not just personal. Friel's great originality lay in the way he treated public history as if it were private memory - as a construct whose truth does not lie in its mere facts. Just as it did not matter to him in the end that his lovely memory of his father could not have happened, the characters in his plays turn history into words, images, stories. It is their way of not being crushed by the weight of its cruel inevitability.

After his world has imploded, at the end of Translations, the schoolmaster Hugh tells his son Owen that "it is not the literal past, the 'facts' of history that shape us, but images of the past embodied in language".

...(more)

thanks (yet again) to The Page

_______________________

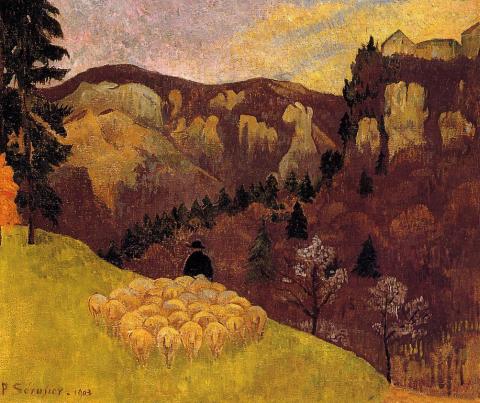

The times

Paul Sérusier

1919

_______________________

NO: The Translation of Ángel Escobar

Kristin Dykstra

Ángel Escobar, born in 1957 and deceased in 1997, has earned extraordinary respect in Cuba. This is coupled with virtual invisibility outside it, except for a few critics and poets with connections to Cuban literature. The contrast may be explained in part because Escobar lived a highly marginalized life. But I suspect another complication: the abjection of his late work is threatening. As a translator I have been thinking about how to address abjection in a highly polarized transnational context, where the US/Cuba political divide encourages the flattening of expression.

(....)

the undying machine of political standoff presupposes that writing will be useful. I speculate that many people who want to encourage respect toward Cuban culture will find literature most useful where it advances more of a YES while adopting stances both rational and advisable.

And what is not politically useful? Poetry insisting that the reader experience – and god forbid accept – abjection in all its resistance to the staples of political discourse, utility and argument. This caliber of discursive resistance is what Breach of Trust puts at stake, and as Escobar becomes better known in the future, it will emerge as a key manifestation across his poetic career. To let readers in on why I’m making this claim, I need to rewind to 1959. Resistance to politics is borne precisely of politics. Ergo it is aggravatingly indebted to politics, something that I suspect must have been at once tiresome and invigorating to Escobar, mostly because it is at once tiresome and invigorating to me as I work with his poems now.

...(more)

Evening Will Come: A Monthly Journal of Poetics (Translation Issue—Issue 51, March 2015)

_______________________

Quick now

Kristin Dykstra

Angel Escobar’s awareness of motion is one of the many elements that make his poems undeniably powerful. To me, as I translate his poems, there is no doubt that Escobar (1957-1997) created multivalent, energetic work, and that a quick reading of one or two poems at least hints at his range. Other writers, at the very least other poets, must recognize the surety of his movements.

Then in moments of pause I wonder about whether the quickness of published pieces – those introductory yet central experiences of encounter with loose poems here and there, or a translator’s commentary in a journal – truly gets so much sensation across. The quickness of Escobar’s mind and life are out there, in his writing. Will readers find them?

Beyond the bounds of the poems themselves come the contexts, offering guidance to new readers. Angel Escobar’s widow, Ana María Jiménez, has pointed out that existing Spanish-language commentaries around his life and death tend to flatten his representation in their repetitions of certain themes. For example, these themes don't tend to include the happiness we see in the 1987 photograph above.

It’s a good reminder to translators – and in parallel fashion, scholars writing critical studies – to periodically pause and take the measure of all these things we create. Our renditions of literature and their paratexts (all those ubiquitous bio notes, plus the commentaries, blurbs, translations of essays by other poets on the relevance of the person or work, the scholarship and so forth that serve as companions to literature) travel in fragmented forms through the worlds of publishing. Where these write-ups successfully pursue some theme with great determination, that very pattern of emphasis causes other possibilities to fade.

...(more)

IntermediumKristin Dykstra

This series tracks recognitions and convergences that give rise to bodies of work in translation. Emerging out of my time spent with Cuban poetry, as well as other writings from this hemisphere, most entries address some intersection between Latin America and the United States, and/or Spanish and English within the US. Some entries center on writers and works that motivate me to continue translating. Others loop outwards to envisage other translators & their translations, and test the frames mounted around translation.

_______________________

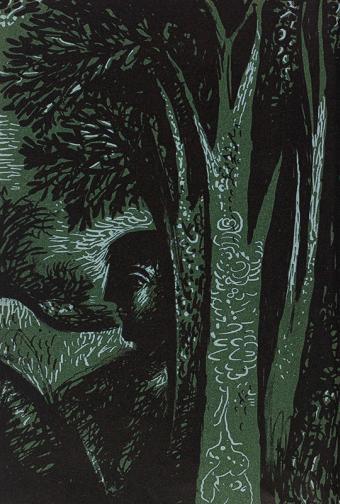

The Flock in the Black Forest

Paul Sérusier

1903

_______________________

"There is one thing that is absolutely certain about throwing a dead cat on the dining room table -- and I don't mean that people will be outraged, alarmed, disgusted. That is true, but irrelevant. The key point, says my Australian friend, is that everyone will shout, 'Jeez, mate, there's a dead cat on the table!' In other words, they will be talking about the dead cat -- the thing you want them to talk about -- and they will not be talking about the issue that has been causing you so much grief."

- Boris Johnson. mayor of London, England

Scared Yet? How Fear Hijacked Campaign 2015

Harper lobbed three 'dead cats' to make us forget the Duffy trial. It's working.

Heather Libby

Lithographs from The Poet's Eye

John Craxton

Born: October 3, 1922,

_______________________

Five Poems

Sean Negus

conjunctions

Hemlock Gridded

In the green night there slips

A lamp in the window

Where burns times’ coordinates.

Pagan lettering on glass sleeves.

Salve there and stays in the glow.

Viewing portal positioned as if transfiguratively posed.

In solitude the antimatter world enlisted.

The story written all evening encompassing.

Rabbit the nocturnal disarrangement.

Crow the brief morning preview.

Bolded words out from the fire.

...(more)

_______________________

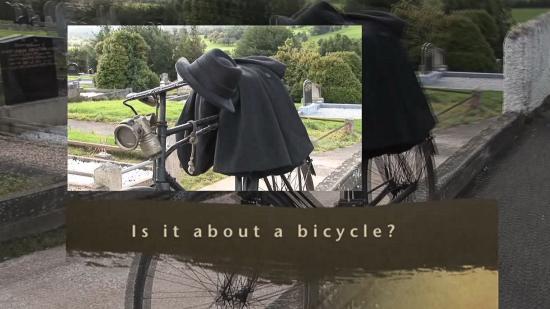

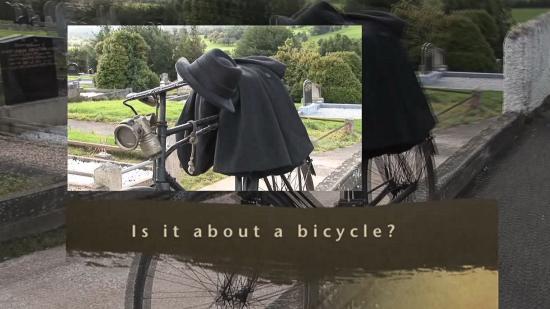

Brian O'Nolan

b. October 5, 1911

Back-chat, Funny Cracks

The novels of Flann O’Brien

John Updike

(....)

On the jacket the author is obscured by his dark hat and his black-rimmed glasses and his own hand at his mouth, and, to be sure, Flann/Brian/Myles, where many an author not only rejoices in his face on his jacket but sets his personal facts in the forefront of his prose, engaged in a significant effort of self-concealment, of pseudonymity lurking behind a prose greatly melodious and garrulous in its confident manner. The front flap of the same jacket states him to be “along with Joyce and Beckett . . . part of the holy trinity of modern Irish literature,” which rings strangely of one who disparaged the Holy Trinity, discounting with considerable scholarly fury in his final novel, “The Dalkey Archive,” the very notion of the Holy Ghost, as having been heedlessly foisted upon the Christian Creed by the Council of Alexandria in the year 362. The man was ingenious and learned like Jim Joyce and like Sam Beckett gave the reader a sweet dose of hopelessness but unlike either of these worthies did not arrive at what we might call artistic resolution. His novels begin with a swoop and a song but end in an uncomfortable murk and with an air of impatience.

...(more)

10 Books That Wouldn't Exist Without Flann O'Brien

Is it about a bicycle?

The story of Brian O'Nolan

youtube The Lives of Brian, A Documentary About Flann O'Brien

vimeo

_______________________

continent. 4.3: Intangible Architectures

Blake Blake Blake

A ghostly copy of Blake sat on one edge of the couch, a second in the middle, and a third on the chair next to the bay window, typing on an invisible keyboard. The unchoreographed movements and silent utterances of these holographic reproductions had been selected at random by the See Your Crime (SYC) algorithm, upon searching through Blake’s memory archive. What each projection had in common was its geotagging: having taken place, at one point or another, in Blake's living room. Every time one of the glowing doppelgängers walked out, the algorithm jumped to a different memory, keeping at least three Blakes (sometimes four or five) inside the room at all times, and following real-time Blake from one room to the next. Blake, crumpled up on the floor, observed them from a corner—one of many locations he had appropriated to minimize what he referred to as "Blake overlaps." Next to him, a small pile of necessities—a beer bottle, crackers, a pack of tissues and a phone—ensured he wouldn't have to leave his post for a while. Blake tilted his head backwards, opened his mouth, and poured. The beer was still cool. He leaned against the wall and closed his eyes.

...(more)

_______________________

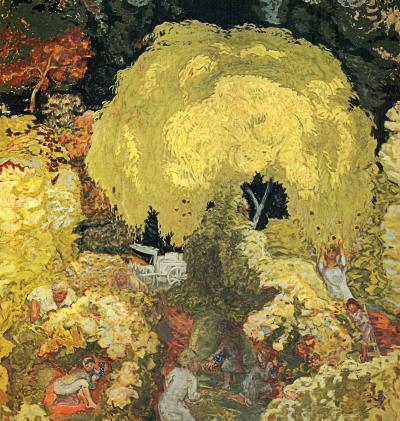

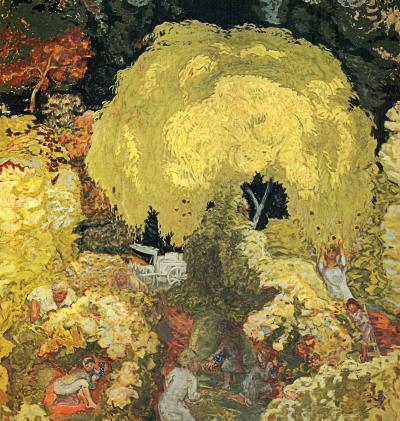

Autumn: The Fruit Pickers

1912

Pierre Bonnard

b. October 3, 1867

_______________________

Free period.

We’re frightened of time. Frightened of the long afternoon.

The sense that time is hollowing us out. The sense that time is emptying us out.

The sense that nothing will ever happen again. The sense that everything’s been done, and everything’s been said.

The fear of time. But who fears it but us? Look at our fellow pupils, sitting and chatting so calmly. Look at them, on their phones, and eating their crisps.

Who singled us out? Who chose us to feel it? Why were we the ones to which it chose to show itself?

Something is taking its course. But what? What’s happening? Something happens when nothing

happens. A rumbling. A murmuring, on the edges of sense. But who speaks? And what are they saying?

Something is taking its course. Something that happens in everything. Something that turns each

moment from itself, sets it aside. Something that undoes time, and sends it on a detour. Something

indifferent, that does not coincide with itself.

Nietzsche And The Burbs

_______________________

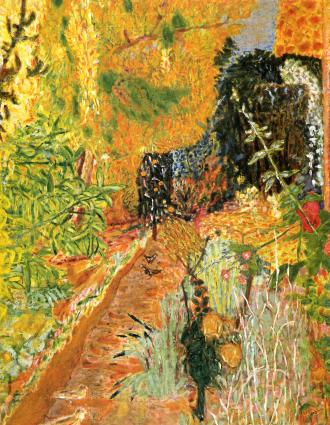

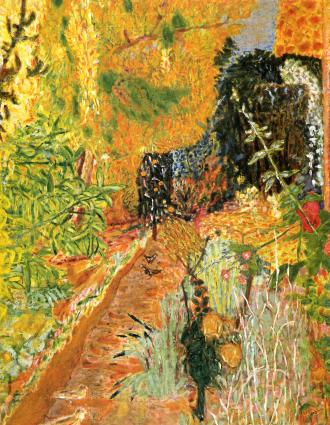

The Garden

Pierre Bonnard

c.1937

_______________________

Sherry Turkle’s ‘Reclaiming Conversation’

reviewed by Jonathan franzen

Sherry Turkle is a singular voice in the discourse about technology. She’s a skeptic who was once a believer, a clinical psychologist among the industry shills and the literary hand-wringers, an empiricist among the cherry-picking anecdotalists, a moderate among the extremists, a realist among the fantasists, a humanist but not a Luddite: a grown-up.

(....)

Our rapturous submission to digital technology has led to an atrophying of human capacities like empathy and self-reflection, and the time has come to reassert ourselves, behave like adults and put technology in its place. As in “Alone Together,” Turkle’s argument derives its power from the breadth of her research and the acuity of her psychological insight. The people she interviews have adopted new technologies in pursuit of greater control, only to feel controlled by them. The likably idealized selves that they’ve created with social media leave their real selves all the more isolated. They communicate incessantly but are afraid of face-to-face conversations; they worry, often nostalgically, that they’re missing out on something fundamental.

...(more)

Movement: Sky and Grey Sea

1941

John Marin

1870 - 1953

_______________________

Tender

C.K. Williams

A tall-masted white sailboat works laboriously across a wave-tossed bay;

when it tilts in the swell, a porthole reflects a dot of light that darts towards me ,

skitters back to refuge in the boat, gleams out again, and timidly retreats,

like a thought that comes almost to mind but slips away into the general glare.

An inflatable tender, tethered to the stern, just skims the commotion of the wake:

within it will be oars, a miniature motor, and, tucked into a pocket, life vests.

Such reassuring redundancy: don’t we desire just such an accessory, faith perhaps,

or at a certain age to be comforted, not daunted, by knowing one will really die?

To bring all that with you, by compulsion admittedly, but on such a slender leash,

and so maneuverable it is, tractable, so nearly frictionless, no need to strain;

though it might have to rush a little to keep up, you hardly know it’s there:

that insouciant headlong scurry, that always ardent leaping forward into place.

C. K. Williams

1936 - 2015

photo by Oliver Morris

Poetry of youth and age

C.K. Williams

TED2001

The Nail

C. K. Williams

Some dictator or other had gone into exile, and now reports were coming about his regime,

the usual crimes, torture, false imprisonment, cruelty and corruption, but then a detail:

that the way his henchmen had disposed of enemies was by hammering nails into their skulls.

Horror, then, what mind does after horror, after that first feeling that you’ll never catch your breath,

mind imagines—how not be annihilated by it?—the preliminary tap, feels it in the tendons of the hand,

feels the way you do with your nail when you’re fixing something, making something, shelves, a bed;

the first light tap to set the slant, and then the slightly harder tap, to em-bed the tip a little more ...

No, no more: this should be happening in myth, in stone, or paint, not in reality, not here;

it should be an emblem of itself, not itself, something that would mean, not really have to happen,

something to go out, expand in implication from that unmoved mass of matter in the breast;

as in the image of an anguished face, in grief for us, not us as us, us as in a myth, a moral tale,

a way to tell the truth that grief is limitless, a way to tell us we must always understand

it’s we who do such things, we who set the slant, embed the tip, lift the sledge and drive the nail,

drive the nail which is the axis upon which turns the brutal human world upon the world.

_______________________

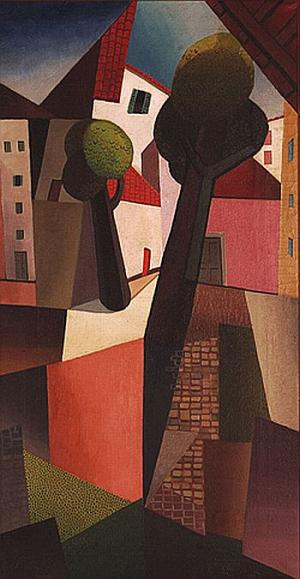

La Voce (The Voice)

1916

Emilio Pettoruti

b. October 1, 1892

_______________________

Alicja, Love, Ligature

Byron Landry

conjunctions

I. Abstract

The entwined history of typography, love, and madness is well-documented: The reader will perhaps recall several typefaces named after the objects of obsessive love (such as Gills’s daughter Joanna, or, of course, Helvetica, named after that timeless beloved, Switzerland herself); reports of unrequited love and its death pact with type are universally observed in the literature, but we will not recount these well-worn anecdotes,1 proceeding instead to examine the more esoteric history of Alicja—a typeface designed by the Berthold Brothers & Sieffert Type Foundry in Chicago, in the year 1921—which, in spite of its perfection, but for reasons we will evince, remains (alas) almost perfectly disused; it is our goal to shed new light on (or, as it were, outline with new darkness) the typeface Alicja, the truncated engagement that inspired it, and the delusion that nearly struck it out.

...(more)

_______________________

Literary Activism, Poetry Riots, and Other Deliriums:

Notes from the Launch The Aircraft Carrier, a Poetry Collection by Roy Chicky Arad

Yosefa Raz

entropy

Perhaps it’s every poet’s secret fantasy to have a minor riot break out at their reading, demonstrating once and for all how poetry makes things happen – how poetry matters in the gritty world, not just in the closed, air-conditioned reading room, hermetically sealed from outside forces.

My first week back in Israel/Palestine after fifteen years in the Bay Area and Toronto included a bike accident, an apocalyptic dust storm, intensely sweet purple-red tomatoes, a poetry riot. A week between countries in a dream-like delirium, and the poetry-reading riot in the middle of it, which I keep coming back to especially in relation to recent American discussions about literary activism, such as Amy King’s panel and critiques such as this. The distinction between “literary activism” and “activism activism” got especially muddled for me this week when poets and activists blurred together, switched identities.

Many of the responses and counter-responses to Amy King’s panel were premised on the idea that activism is the right thing to do (“marches, counter marches, clinic defenses, and on the ground actions” in King’s words) that a supportive community is good, that we are singing the right battle cry. But the poetry riot I witnessed in Tel-Aviv made me consider how hard it is to have certainty about our poetry activism; perhaps we sometimes sing the battle cry out of tune, despite our good intentions?

...(more)

_______________________

Chess Players

Marcel Duchamp

d. October 2, 1968

_______________________

The Neuroscience of Despair

Michael W. Begun

The New Atlantis

(....)

Together with the popular success of psychoactive medications like Prozac and Xanax, the change in the commitments of psychiatry has created ways of talking about mental illness that would have seemed outrageous or even nonsensical less than a century ago. Many of us now blithely accept that depression results from an imbalance of neurotransmitters. While the neurobiological understanding of mental disorders is still at a rudimentary stage, drugs that alter brain chemistry have definite palliative effects, and we increasingly look for and accept explanations of mental illness in neuroscientific terms. We might still take older explanations drawn from psychoanalysis or social psychiatry to hold some value, but we tend to assume that they can be reduced to neurobiology.

We generally think that this counts as progress — that science has uncovered or will uncover the real causes of mental disorders like depression and schizophrenia, and will yield therapies that cure these illnesses at their neurobiological roots. But as more and more mental experiences get swept within the purview of neuroscience — from mental disorders like schizophrenia to everyday decisions like “Should I buy Coke or Pepsi?” — we ought to think about how this came about, what it means for our self-understanding, and whether the new outlook can give an adequate account of mental disorders. How did we come to think of some forms of melancholy as a disorder called depression that is ultimately caused by chemical processes and properly treated by drugs that act on these processes? A look back at the historical developments that have led to this situation may offer some insight into the broader trend of uncritically embracing neuroscientific ways of describing our selves and our society.

...(more)

_______________________

Calle de Milán

Emilio Pettoruti

1919

_______________________

Light

C. K. Williams

Another drought morning after a too brief dawn downpour,

uncountable silvery glitterings on the leaves of the withering maples -

I think of a troop of the blissful blessed approaching Dante,

"a hundred spheres shining," he rhapsodizes, "the purest pearls..."

then of the frightening brilliant myriad gleam in my lamp

of the eyes of the vast swarm of bats I found once in a cave,

a chamber whose walls seethed with a spaceless carpet of creatures,

their cacophonous, keen, insistent, incessant squeakings and squealings

churning the warm, rank, cloying air; of how one,

perfectly still among all the fitfully twitching others,

was looking straight at me, gazing solemnly, thoughtfully up

from beneath the intricate furl of its leathery wings

as though it couldn't believe I was there, or was trying to place me,

to situate me in the gnarl we'd evolved from, and now,

the trees still heartrendingly asparkle, Dante again,

this time the way he'll refer to a figure he meets as "the life of..."

not the soul, or person, the life, and once more the bat, and I,

our lives in that moment together, our lives, our lives,

his with no vision of celestial splendor, no poem,

mine with no flight, no unblundering dash through the dark,

his without realizing it would, so soon, no longer exist,

mine having to know for us both that everything ends,

world, after-world, even their memory, steamed away

like the film of uncertain vapor of the last of the luscious rain.

|