|

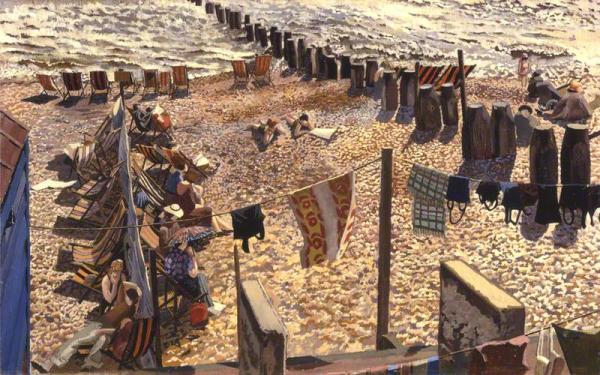

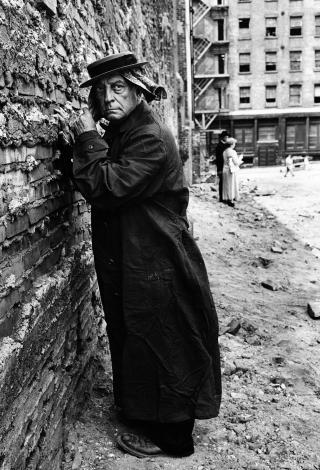

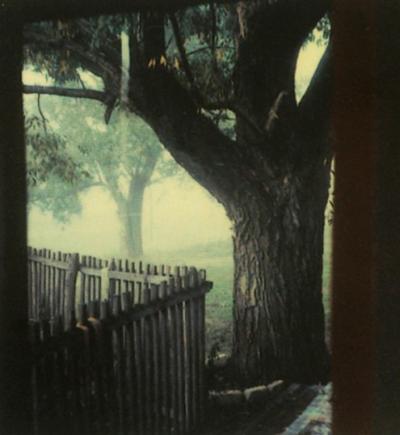

Southwold, Sussex

1937

Stanley Spencer

b. June 30, 1891

_______________________

Kelp chorus

Endi Bogue Hartigan

They are all throat in the night–they say the word spirit with ease

They are the drifting, violet gowns of the throat

They are all night in the throat–they are all ease in the all

They say the words blue and baleen and sailing and seas

Perhaps they have the relationship of the throat determined and so are all it

Or, they have the slick violet gown of the throat and they are the luster of

the gown slipping over the fragile, wet word of the spirit

Or, perhaps the word spirit with ease is the same as the throat

Or, the naked “they” is the same as “they say”

Then we want it divulged, what they have, or had, or seem to have in ease,

a sea of violet gowns washed up in small pathetic heaps,

they are all heaped in the white, coughed up on salt-encrusted sand,

iridescent froth sticking or popping against them

At the touch of the bubble, an acid hurt

Then we are all them, and not without ease from

Pool [5 choruses]

Endi Bogue Hartigan

omnidawn

Iterations and interstices

Endi Bogue Hartigan on fields and crowds and more jacket2

(....) If you’ve been to the Oregon coast — or really almost any coastline — you’ve probably seen tangled heaps of kelp, those drying, gelatinous, fly-ridden, stinky, wonderful heaps. I often end up reading “kelp chorus” when I give readings from this book, partly because of the sound, and sometimes I ask people to imagine these kelp mountains as an embodiment of voice, but multitudinous voices, tangled. I am pretty sure when I wrote this poem that the kelp and the chorus were a clustered entity from the start, so it is hard to see one as reflection of the other, exactly. I always liked how the chorus in classical literature could exist both inside and outside the narrative of the theater at the same time, so in the context of this poem, I imagined this kelp mixture at the shore edge in that similarly paradoxical space, where voices may or may not touch, and there is sting in both distance from and closeness to this tangle.

The entry point is different with each poem that touches on natural forms of course, whether they are lilies, or other forms, but I’m definitely drawn to poetry that has physicality to it — whether through music, thought, or imagery. I’ve been fortunate to live in pretty amazing places (I have spent most of my life in the Pacific Northwest and Hawaii), so it’s easy to use language drawn from this environment as a kind of material paint. But it is more than just paint; it is not secondary but intrinsic. The kelps and lilies and shorelines of the natural world are a nuanced place to explore complex, public subjects like crowds and violence. It is also a way to say that “confusion and injury” inevitably occur in the context of this lushness, that they are simultaneously the material.

...(more)

_______________________

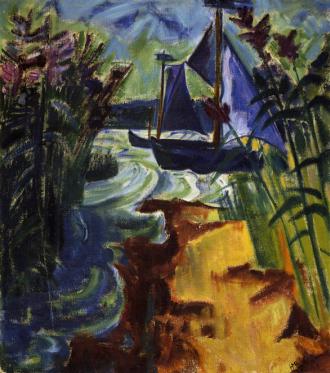

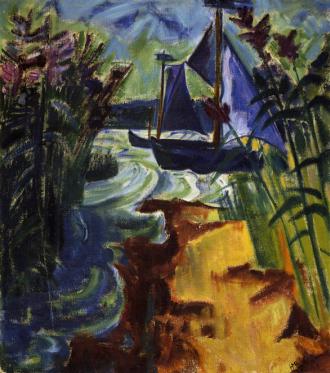

Max Pechstein

(1881-1955)

_______________________

Both together: Migrations by Gabriel Josipovici

Stephen Mitchelmore

this space

(....)

The scenes never stop to clarify a traditional back story, nor even to insert narrative conjunctions, so that the café scene in one paragraph moves straight into another in which the man is pacing to and fro in his bedroom. A scene from adulthood moves then without pause to a scene from childhood, yet not as in stream of consciousness but something less secure, less comforting, not contained within a mind but as if the meaning of each lived moment is sought in repetition and in order to resist the constant migration of mind and self. The apparent distress of the protagonist in this quest is described with a mixture of clinical distance and romantic metaphor and simile.

The bulb hangs down in the middle of the room. It is lit, making the curtainless window appear like a black mirror in which only the blub itself is reflected. But the light is poor and seems to have difficulty reaching the walls of the big room. Even the washbasin and the bed are in shadow.

Silence flows away from him in dark rivers.

Falling backwards, in a wide arc, he stretches out his hand to grip the lamppost and encounters only air. The black sky presses on his face like a blanket.

Everything flows away from him. It flows outwards and away in dark rivers.

The rhythms of repetitions and returns build an uncommon presence, as if the words have been typed directly onto the page, indenting the paper with the urgency and confusion of a writer trying to catch up with the world and himself. So, soon after 10pm, I had started reading Migrations and before midnight I had read 50 pages. And this is why I read: the gifts of chance rediscovery, of being returned to real needs, which is also why I remember Thomas Bernhard, aged 19 and on the edge of death, reading Dostoevsky's The Demons: "Never in my whole life had I read such an engrossing and elemental work ... it had shown me a path that I could follow and told me that I was on the right one, the one that led out".

The elemental in literature is often misdiagnosed as outré subject matter or writing described as raw and unmediated, yet in Migrations the elemental appears as the subjection of form and content to the logic of its title: constant becoming in constant undoing; constant undoing in constant becoming; the logic of birth and death. So the man is unnamed not in order to protect identity but to loosen the binds of identity, for time to colonise the means by which the identified resists time and self erasure. ...

...(more)

_______________________

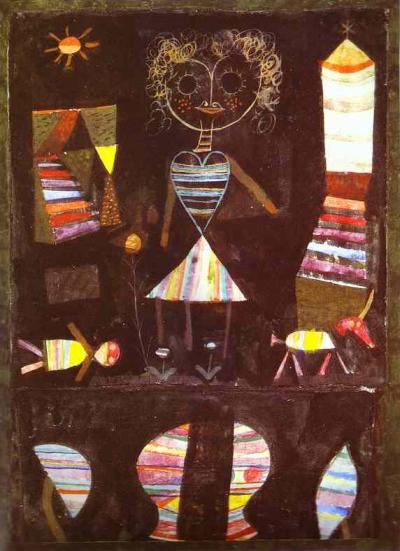

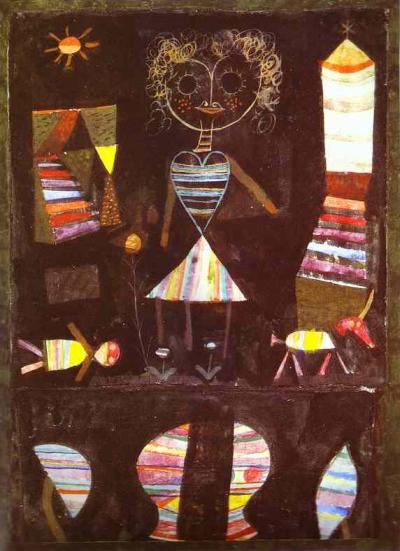

Struck from the List

1933

Paul Klee

d. June 29, 1940

_______________________

The Predator Class: Social Exclusion and Savage Capitalism

S.C. Hickman

(....)

This sense of expulsion, eviction, exile: the twilight-zone effect that one no longer belongs to one’s roots, one’s country and place of origin; and, yet, does not belong anywhere else, either: that one is a permanent exile from the earth, caught in a stasis and void in-between the living and the dead, a ghost inhabiting two worlds. He says this is happening to us all now. Visibly in the actual refugee camps, and invisibly in all countries where one is excluded from the fantasy worlds of the predatory elite who act as overseers from their gated communities and securitized enclaves. Maybe we are all exiles now, those of us on the left who exist in-between the lost object of utopia, and the actual dystopian futures that exist around us in the realms of oppression. Not belonging, a non-belongingness – a discordant inharmonic dissonance of the dissident.

...(more)

_______________________

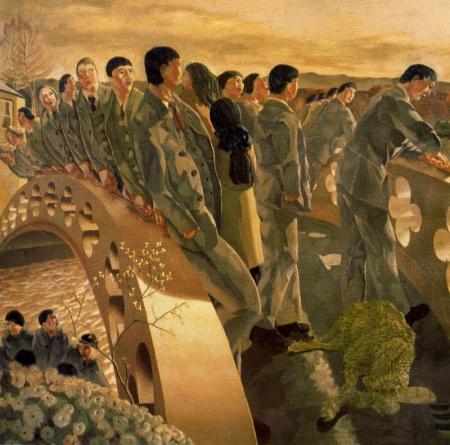

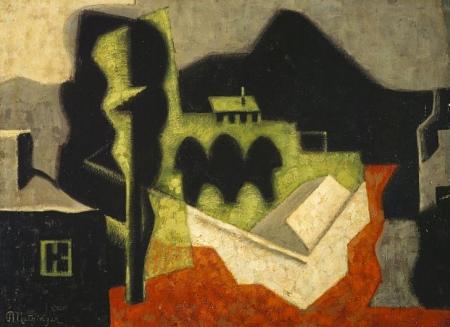

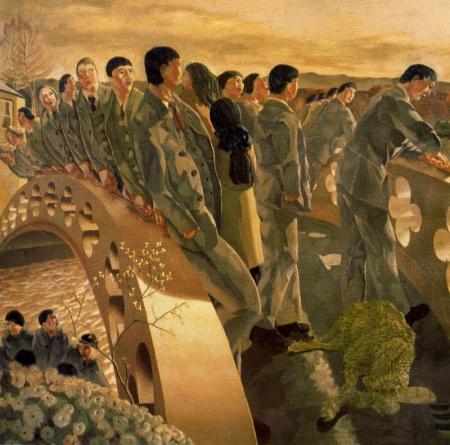

The bridge

Stanley Spencer

_______________________

It is interesting that many of the claims that, back in the mid-1970s, made Feyerabend a radical maverick are, nowadays, rather commonplace. Consider the general picture of science sketched in Against Method, of ‘science’ as pluralistic and disunified, socially situated, unavoidably value-laden, complexly bound up with sociopolitical concerns, whose social and epistemic authority is disputed and, to a degree, fragile.

- Ian James Kidd

Remembering Feyerabend: On the Fortieth Anniversary of Against MethodTerence Blake Agent Swarm

This year is the 40th anniversary of the publication of the first edition of Feyerabend’s AGAINST METHOD. It seems an appropriate time to revisit the book, and Feyerabend’s thought more generally, to see what contribution it can make to our current intellectual and existential concerns. Feyerabend did not separate philosophy from the general culture, and he constantly considered abstract intellectual pursuits in relation to concrete life. This privileging of life over abstract motivations is the well-spring of Feyerabend’s repeated claim that he is not a philosopher. Paradoxically, this insistence is part of what makes him a great philosopher, one who breaks the rules not out of “provocation” but because he has not the slightest interest in allowing his conduct and thought to be governed by the abstract stipulations of lifeless thinkers.

...(more)

_______________________

Puppet theater

Paul Klee

1923

_______________________

Toward a politics of information

A conversation with Luciano Floridi

eurozine

(....)

At this stage of human history, we conceptualize, we understand the world, we model the world in informational terms – and that's a good thing; it makes a lot of sense. Instead of having a Newtonian conception of a human being, like something made of mass, in terms of physics, chemistry and biology, we describe human beings in terms of networks, informational properties, privacy, and so on.

This means that, when I suggest that we are informational entities, what I'm talking about is an epistemological way of doing metaphysics, pretty much in the Kantian tradition; we understand the world today in informational terms, and therefore we look at each other as informational entities in a network, and that's why some of the issues that were not there in the past, because we didn't focus on them, are now very evident, such as the importance of privacy, online security, or education as a way of shaping the informational self. Not that they were entirely absent in the past, but now they are much more salient issues.

...(more)

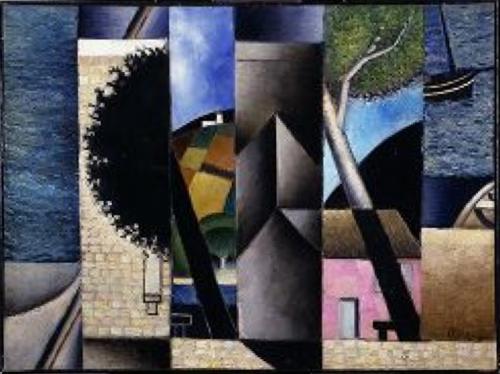

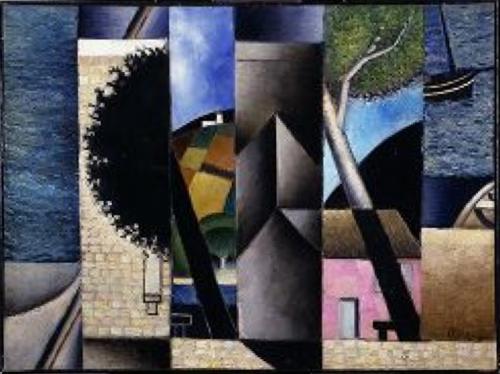

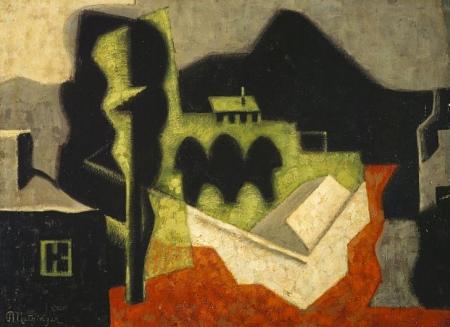

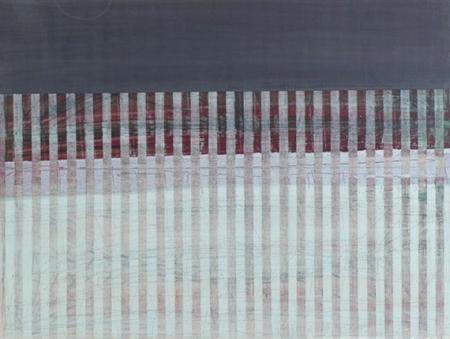

Marine, Composition

1912

Jean Metzinger

1883 - 1956

_______________________

Metonymy as an Approach to a Real World

William Bronk

Whether what we sense of this world

is the what of this world only, or the what

of which of several possible worlds

--which what?--something of what we sense

may be true, may be the world, what it is, what we sense.

For the rest, a truce is possible, the tolerance

of travelers, eating foreign foods, trying words

that twist the tongue, to feel that time and place,

not thinking that this is the real world.

Conceded, that all the clocks tell local time;

conceded, that "here" is anywhere we bound

and fill a space; conceded, we make a world:

is something caught there, contained there,

something real, something which we can sense?

Once in a city blocked and filled, I saw

the light lie in the deep chasm of a street,

palpable and blue, as though it had drifted in

from say, the sea, a purity of space.

_______________________

William Bronk’s Path Among the Forms

Thomas Lisk

jacket 29

(....)

The World in Time and Space, a poem from The World, The Worldless, the period between the two I’ve been discussing, provides another anchor for an explanation of the underlying conceptions of time and space that ground Bronk’s prosody. Also not quite a sonnet, the sixteen-line poem is divided spatially on the page into two unrhymed septets and an unrhymed couplet, a symmetrical and orderly form that is nonetheless a more ‘open’ alternative to a sonnet.

If there is a shape to the world in terms of time

and space — our own or, by concessions to shapes

of others, received — if there is such a shape

— in part there is — note that the words we use

referring to time, as temporary for one

or temporal, admit our diffidence

toward any shape we give the world by time.

The shapes of space share less of this distrust,

we acknowledge chaotic recalcitrance

in space, its endlessness both ways, the great,

and small, and yet respect the finite shape

of bounded places, as much as to say they are true.

Some absolute of shape is stated there

which satisfies the need that makes this shape.

How strange that after all it is rarely space

but time we cling to, unwilling to let it go.

Ezra Pound said, ‘Rhythm is a form cut into TIME, as a design is determined SPACE’ . Robert Frost’s poetry relies on a prosody of mechanical time, registered by metrics, while Olson’s prosody sets up a prosody of space, registered as the open field of the white page, and organic time based on breath. In this poem, the first stanza begins and ends with the word ‘time,’ the second ends with the word ‘shape,’ and the closing couplet ends the poem on the word ‘go,’ as orderly an arrangement as that of a strict sonnet. Three words ending three stanzas sum up Bronk’s poem neatly, as he moves toward an increasing compression of form that is, perhaps, paradoxically also more open. We cling to ‘time,’ we don’t cling to ‘shape,’ yet we must let both go.

...(more)

_______________________

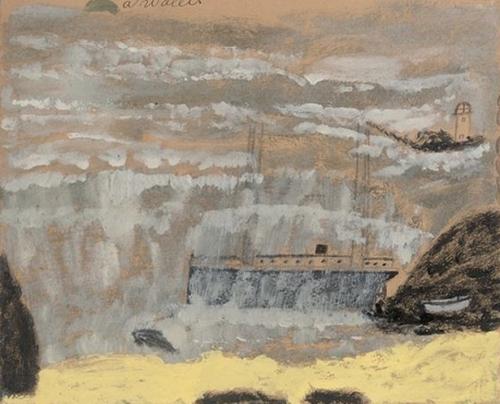

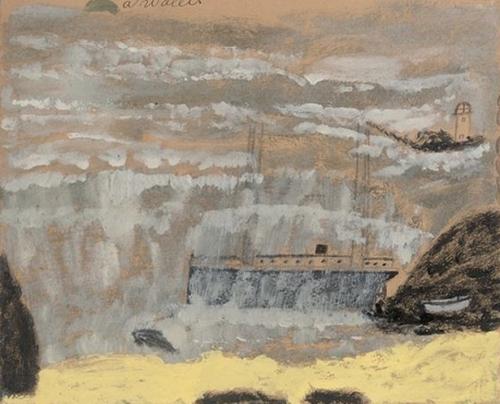

Sinking ship and lifeboat

Alfred Wallis

1855 - 1942

_______________________

from Água Viva

Clarice Lispector

translated by Stefan Tobler

presented by Tom Clark

Not having been born an animal is a secret nostalgia of mine. They sometimes clamor for many generations from afar and I can't respond except by growing restless. It's the call.

This free air, this wind that strikes me in the soul of the face leaving it troubled in an imitation of an anguished ever-new ecstasy, anew and always, every time the plunge into a bottomless thing from which I fall always ceaselessly falling until I die and achieve at last silence. Oh sirocco wind, I do not forgive thee for death, thou who bringest me a damaged memory of things lived that, alas for me, always repeat themselves, even in other and different forms. The living thing scares me as the future scares me. That, like things that have passed, is intangible, mere supposition.

I am at this instant in a white void awaiting the next instant. Measuring time is just a working hypothesis. But whatever exists is perishable and this forces us to measure immutable and permanent time. It never began and will never end. Never.

...(more)

_______________________

Ben Nicholson

1894 - 1982

_______________________

Landscape and Space

Larval Subjects

Landscape is neither in space, nor is it of space. Indeed, landscape had to be evacuated and erased in order for space to come into being. In this regard, space is a historical fiction that is all too real in its consequences. Space was formed as conceptual space through a historical process that involved the invention of writing, the development of mathematics, and the rise of capitalism and colonialism. Before that there was only landscape. However, while a certain form of humanity is a necessary condition for the emergence of space, landscape is in no way dependent on the human nor any other living being. Where space is a epistemic category, a cultural category, landscape was there well before any humans or any other living beings existed and will be there long after the demise of all these beings. Landscape is in no way dependent on the gaze of the artist nor those that dwell within it.

...(more)

_______________________

Jean Metzinger

1912

_______________________

What We Are

William Bronk

1918–1999

What we are? We say we want to become

what we are or what we have an intent to be.

We read the possibilities, or try.

We get to some. We think we know how to read.

We recognize a word, here and there,

a syllable: male, it says perhaps,

or female, talent -- look what you could do --

or love, it says, love is what we mean.

Being at any cost: in the end, the cost

is terrible but so is the lure to us.

We see it move and shine and swallow it.

We say we are and this is what we are

as to say we should be and this is what to be

and this is how. But, oh, it isn’t so.

_______________________

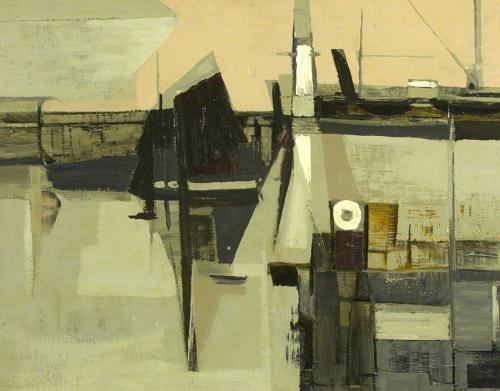

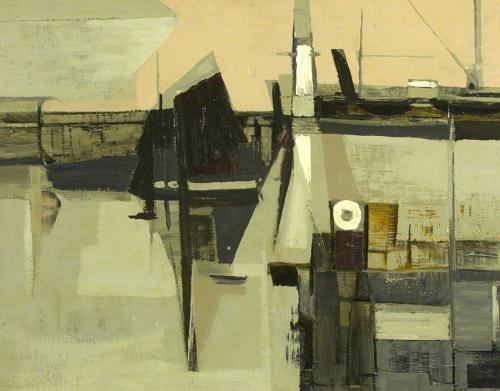

harbour

Bryan Wynter

1915 - 1975

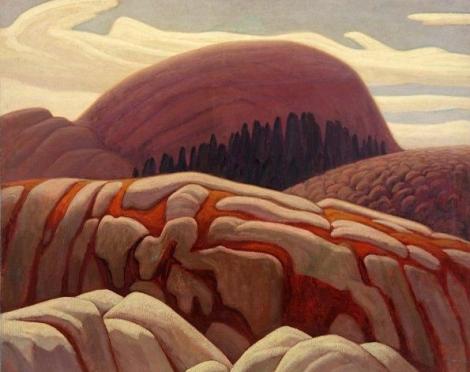

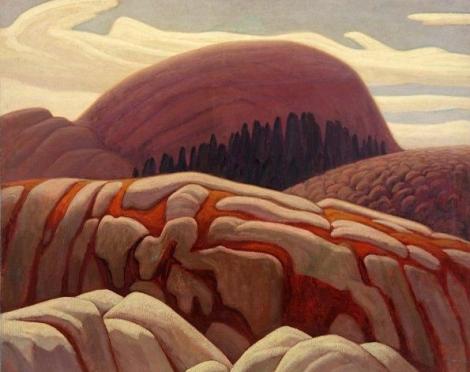

Lake Superior Hill

Lawren Harris

ca.1925

_______________________

"Geologic Time from Now On!": Lorine Niedecker's Lake Superior

Heather Houser

Lake Superior, a 2013 collection of Lorine Niedecker’s writings from Wave Books, is unlike most posthumous volumes. The compilation opens with the title poem, “Lake Superior,” and then charts a journey through archival materials by Niedecker and the historical texts that inspired her piece. As polyvocal as the poem that launches it, Lake Superior orchestrates voices that have portrayed the Great Lakes since white missionaries arrived in the 16th century.

(....)

“Lake Superior” invites an experience of interconnectedness by excavating a specific place, but it begins with the general thesis Niedecker arrives at in her journal:

In every part of every living thing

is stuff that once was rock

In blood the minerals

of the rock

*

Iron the common element of earth

Without an “I,” the perspective is removed and this creates a greater intimacy between the reader and the earth. Before the speaker announces herself in the 12th of the poem’s 13 sections, we enter an ecosystem composed not only of “every living thing” but also of the earth’s elements. In lieu of summoning a fraternity of animals and plants (a conventional approach to depicting place) Niedecker’s sharp eye and deep wonder grant her access to geological time. The poem and her journal rediscover early 19th-century geologists’ awareness that the earth is ancient and dynamic.

(....)

Lake Superior is successful in respecting the fragmentary, interrogative nature of Niedecker’s writing while also helping readers recognize the poet’s investment in identifying affinities between kinds of matter and moments in time. The historical and archival sources throughout the book emphasize that the kind of immersion in place that Niedecker practices is not provincializing or parochial. Rather than shut her off from global, historical, environmental, and social phenomena, her sense of place opens out onto them, broadening her perspective. Perhaps most importantly, engagements with place generate a peculiar sense of time, which the Wave editors respect and replicate. The book takes a cue from its title poem and carefully marbles geologic time, historical time, and experiential time by leaping between texts from the 20th, 17th, and 19th centuries before reaching Niedecker’s own notes charting the geologic time scale, beginning with the formation of the earth “3000 to 5000 million yrs. ago.”

Compiled in this way, the book underscores the timelessness of Niedecker’s poetry and its relevance to the current moment of planetary endangerment. To my mind, these crossings of time are Lake Superior’s greatest achievement and contribution to environmental writing. Environmental art today faces the stiff task of figuring out how to carry audiences across time scales. It strives to give a sense of how a receding past has led to a precarious present, and what we might do to avert or adapt to a threatened future. This time travel is necessary if we’re to treat climate change, mass extinction, and other crises as social, cultural, and experiential challenges and not just as problems for quantitative scientists and engineers.

...(more)

_______________________

Rhetoric of the everyday

Lorine Niedecker’s ‘Lake Superior’

Dale Smith

jacket2

(....)

I want to discuss this poem because I’m interested in how mood and emotion so often inform or prepare judgments, offering stances toward the world. The language game of Niedecker’s poetry, to borrow Ludwig Wittgenstein’s term for the uses of language in ordinary contexts, takes the experience of the everyday as ground for attention. The Objectivist tradition of writing inspired by William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, and others, along with contemporary authors like Lyn Hejinian and Joanne Kyger, continues this use of poetry as a “language of inquiry” into the everyday experiences that compose society. The mundane and our many moods in it sustain frameworks of attention in rhetorical encounters that underlie values, or that challenge us to amend certain attitudes or worldviews. Rhetoric, far from being a mere use of figures and tropes as it is often assumed, shapes inquiry and determines modes of truth seeking. By truth I mean the dynamic actions that make the world known. Poetry, similarly, in this Objectivist mode, and in Niedecker’s exemplary “Lake Superior,” shows how individual values and beliefs can be contained within the larger criteria of history and natural science.

Niedecker delivers an enthusiastic concentration of language on objects of everyday experience. Her work suggests not only the temporal and spatial scales that defined the geographic regions of her investigation; it also shows how attitudes, enthusiasms, values, beliefs, and worldviews can be conveyed in everyday language. So much of our communication is informed by phatic utterances, gestures, confirmations or denials of feeling, and occasions to disclose worldviews by way of specific attitudes. Poetry, as Walter Jost argues, “makes evident a way of life.” And a way of life often can be messy, unstable, careless, even as in some of the best poetry we find evidence of persuasion, challenge, and acknowledgement of new positions toward the world. A kind of critical flexibility is required to purchase a hold on any given poem. An author like Niedecker challenges us to measure our personal interests and concerns within what Douglas Crase calls the “evolutional sublime,” a temporal scale that is vast, and in which the meaning of our beliefs and values remains to be discovered.

...(more)

Lake Superior

Lorine Niedecker google books

_______________________

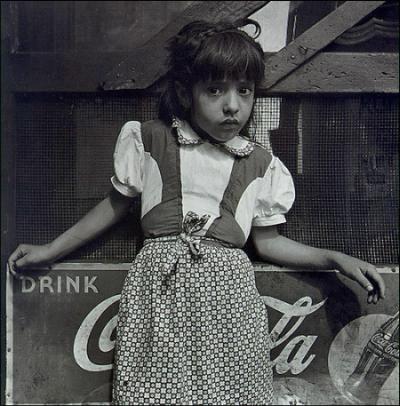

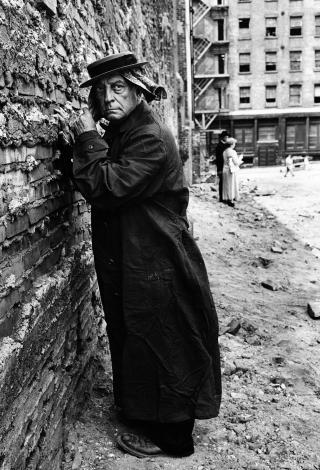

still from "Time Capsule"

Louis Faurer

The Streets, Frozen in Neon

Carol Kino

_______________________

The History Manifesto

Jo Guldi and David Armitage

Cambridge University Press open-access monograph

Introduction: The bonfire of the humanities?

A spectre is haunting our time: the spectre of the short term.

We live in a moment of accelerating crisis that is characterised by the shortage of long-term thinking. Even as rising sea-levels threaten low-lying communities and coastal regions, the world’s cities stockpile waste, and human actions poison the oceans, earth, and groundwater for future generations. We face rising economic inequality within nations even as inequalities between countries abate while international hierarchies revert to conditions not seen since the late eighteenth century, when China last dominated the global economy. Where, we might ask, is safety, where is freedom? What place will our children call home? There is no public office of the long term that you can call for answers about who, if anyone, is preparing to respond to these epochal changes. Instead, almost every aspect of human life is plotted and judged, packaged and paid for, on time-scales of a few months or years. There are few opportunities to shake those projects loose from their short-term moorings. It can hardly seem worth while to raise questions of the long term at all.

(....)

Thinking about the past in order to see the future is not actually so difficult. Most of us become aware of change first in the family, as we regard the omnipresent tensions between one generation and the next. In even these familial exchanges, we look backwards in order to see the future. Nimble people, whether activists or entrepreneurs, likewise depend on an instinctual sense of change from past to present to future as they navigate through their day-to-day activities. Noticing a major shift in the economy before one’s contemporaries may result in the building of fortunes, as is the case for the real estate speculator who notices rich people moving to a former ghetto before other developers. Noticing a shift in politics, an amassing of unprecedented power by corporations and the repeal of earlier legislation, is what precipitated a movement like Occupy Wall Street. Regardless of age or security of income, we are all in the business of making sense of a changing world. In all cases, understanding the nexus of past and future is crucial to acting upon what comes next.

But who writes about these changes as long-term developments? Who nourishes those looking for brighter futures with the material from our collective past? Centuries and epochs are often mysteries too deep and wide for journalists to concern themselves with. Only in rare conversations does anyone notice that there are continuities that are relevant and possible to see. Who is trained to wait steadily upon these vibrations of deeper time and then translate them for others?

...(more)

_______________________

Louis Faurer

1916 - 2001

_______________________

The Nightwalker and the Nocturnal Picaresque

Matthew Beaumont

berfois

At the end of the seventeenth century a new literary genre or subgenre emerged in England, one that might be characterized as the nocturnal picaresque. Its authors, who were moralists or satirists or social tourists, or all of these at the same time, and who were almost invariably male, purported to recount their episodic adventures as pedestrians patrolling the streets of the metropolis at night.

These narratives, which often provided detailed portraits of particular places, especially ones with corrupt reputations, also paid close attention to the precise times when more or less nefarious activities unfolded in the streets. As distinct from diaries, they were noctuaries (in his Dictionary of the English Language [1755], Samuel Johnson defined a “noctuary” simply as “an account of what passes at night”). These apparently unmediated, more or less diaristic accounts of what happened during the course of the night on the street embodied either a tragic or a comic parable of the city, depending on whether their authors intended to celebrate its nightlife or condemn it as satanic.

The nocturnal picaresque, composed more often in prose than verse, was a distinctively modern, metropolitan form that, like several other literary genres that emerged in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, comprised a response to the dramatic social and architectural transformations of the metropolis after the Great Fire of 1666.

...(more)

_______________________

Clyfford Still

d. June 23, 1980

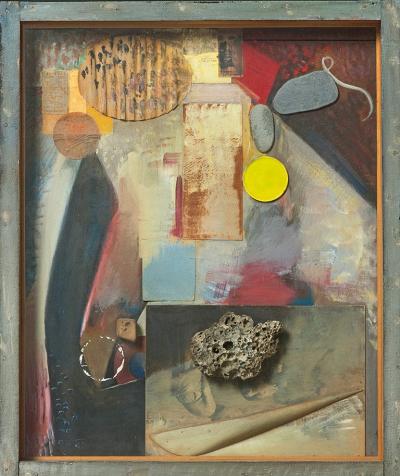

Pine Trees

1946-47

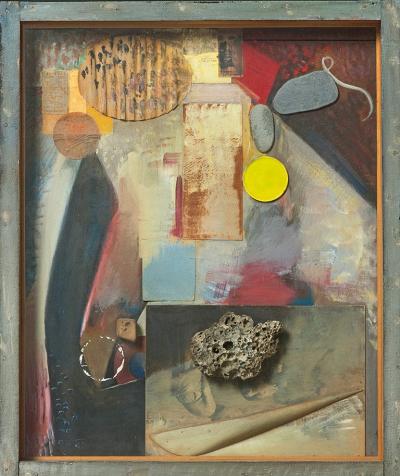

Kurt Schwitters

b. June 20, 1887

_______________________

Three Poems

Chris Andrews

The Manchester Review

Bright Edge

(....)

With a child on the cusp of babble

and a parent falling back on “thing,”

why would he wonder when he last thought,

But if I went round speaking frankly

I’d be out of a job pretty soon.

A wattlebird startled by the whoop

shakes a brace of droplets down on him.

Thin shocks of casuarina needles

and a bright edge of cloud overhead.

...(more)

Three Poems

Chris Andrews Contrappasso Magazine

_______________________

between saying and doing

Robert Brandom interviewed by Richard Marshall

3am

"Robert Brandom is the pittsburghegelianasaurus big beast pragmatist lurking in the philosophical jungle. He’s always thinking about the importance of language when thinking about humans, about discursive understanding, about American and Wittgensteinian pragmatism, about analytic pragmatism, about Sellars, about compositionality, about semantic holism, about the Kant-Sellars thesis, inferentialism, AI, German Idealism, Hegel as pragmatist, intentionality, Wittgenstein,expressivism, about why understanding is part of the core of the philosophic enterprise and why he thinks its an exciting time to be working in philosophy. This one’s leaving deep tracks…" _______________________

Kurt Schwitters

_______________________

Eight Questions for Chris Andrews on his translation of César Aira's The Musical Brain

Books by Roberto Bolaño and César Aira translated by Chris Andrews

new directions publishing

The Chris Andrews Interview

by Scott Bryan Wilson

(....)

SBW: What do you mean by the translator getting in the way too much?

CA: I mean producing a translation that is unduly distracting, which I guess can happen if it isn’t quite complete, so that the syntactic patterns of the source language creep into the target language a bit too much and make the translation more syntactically odd than the original, or if the translation goes over the top and becomes showy. But I don’t much like pronouncing on this sort of thing because I’m no doubt guilty of under- and over-translating myself, and the whole business of translation studies can be a distraction from the works themselves, which are way more interesting in the end.

...(more)

Chris Andrews interview

by Will Heyward bomb

(....)

... it’s not just a question of reading the language, or speaking it, or feeling comfortable with it. You develop a set of strategies for overcoming the challenges presented by translating between two particular languages, and then there are strategies particular to the kind of text you’re working on. You sort of train yourself over again every time, as you go, in a quite focused way. I imagine that for people who are switching between source languages—and between languages that are further apart than Spanish and French—it probably takes a little while to get their translation mechanisms operating smoothly again.

WH You used the word, training, and I thought of a remark I heard Eliot Weinberger—another translator from Spanish to English—make, in which he said that translation is the greatest education on how to write. Is this the case for you?

CA That’s an interesting one, and I think Eliot Weinberger comes at it from a slightly different angle, I think he’s coming at it from a Poundian angle. And he is seeing translation as a way of collecting a kind of armoury of language resources that can be deployed in writing essays and poems. I would say that I have learned a lot through translation, but I couldn’t honestly say that I’ve noticed it improving my writing. It’s true that it obliges you to spend a long time looking for alternative phrases or synonyms. So you spend a long time consulting thesauruses, which is a pleasurable activity in itself, looking at different ways things can be said, and hopefully enlarging and loosening up your active vocabulary. So perhaps this breaks down some of your tics and habits.

...(more)

_______________________

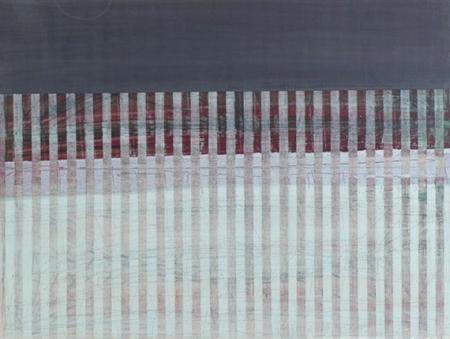

Moshe Kupferman

d. June 20, 2003

_______________________

Poems by Chris Andrews

Strange Perfecter

Who was that strange perfecter occasionally

stepping in to give my life a sideways nudge?

Or was it just a series of accidents?

Despite the multiplying data there’s not

necessarily anyone on your case

in a world where biometric differences

can cover up the gulf that is fixed between

darlings of Morpheus and insomniacs

strapped into the home theatre of their thought,

or between people who feel that the real life

is intimated by bare, windswept uplands

and those who want to live where rhinoplasty

is already as normal as filling teeth.

I was the perfect stranger continually

stumbling by chance back into my life to find

it was getting on pretty well without me

in a world where what people wear correlates

poorly with what they’re capable of doing

to someone who’ll never be useful to them,

where some can sing an ache to sleep and others

are quite sure they know what intelligence is.

...(more)

Fifty-one contemporary poets from Australia: Part 5

Edited by Pam Brown jacket2_______________________

Kurt Schwitters

_______________________

Human Waste: Slums, Exclusion and the End of Capitalism

S.C. Hickman

(....)

... The marginal, the disaffected, the excluded are the Lacanian lost object in the world today, the link that capital cannot include within its dynamic logic of excess value being recaptured. Instead it merely makes this exclusion invisible within its spectacle, displaces it from the arena of its enslavement to jouissance. It allows it to fester at the margins like a jungle beast biding its time. This sense of the inclusion-exclusion dynamic and dialectic drives Žižek’s central critique of capitalism as have more priority than the other three combined.

As Mike Davis will record in his Planet of Slums of the military-industrial global complex: its best minds have dared to venture where most United Nations, World Bank or Department of State types fear to go: down the road that logically follows from the abdication of urban reform. As in the past, this is a “street without joy,” and, indeed, the unemployed teenage fighters of the ‘Mahdi Army’ in Baghdad’s Sadr City – one of the world’s largest slums – taunt American occupiers with the promise that their main boulevard is “Vietnam Street.” But the war planners don’t blench. With coldblooded lucidity, they now assert that the “feral, failed cities” of the Third World – especially their slum outskirts – will be the distinctive battlespace of the twenty-first century. Global governance doctrine is being reshaped accordingly to support a low-intensity world war of unlimited duration against criminalized segments of the urban poor. This is the true “clash of civilizations.”

...(more)

_______________________

Moshe Kupferman

_______________________

Decapitalism, Left Scarcity, and the State

Nina Power

(....)

The free-floating spaceship as the speculative horizon of a non-earth-bound post-capitalist accelerationism can be read as a fantasy, albeit a cool one, but also a desire for a lack of dependency, whether it be upon finite terrestrial resources or the labour of others. Celestial fetishism and its self-spinning heavenly machines can also be read as a desire for a perpetual-motion machine in place of, or rather comprising, a permanent revolution, a kind of resistanceless infinite burst of invention. I want to place in opposition to this smooth accelerated image of technology in post-capitalist, post-terrestrial space an idea of “decapitalism” rather than “anti-capitalism,” the latter too tainted by Srnicek and Williams’s dismissive critique of “the folk politics of localism, direct action and relentless horizontalism.” What I am proposing as “decapitalism” is linguistically and conceptually like Illich’s idea of “deschooling,” but also similar to “decolonization”: the point is to take back what is left, along with the technologies that have contributed to despoliation and exploitation, and turn it back against this same destruction. This does not depend upon a “going through” capitalism to get to the other side, but rather involves cutting off the heads of those who control technology—decapitating capitalism, as it were. This proposed redistribution of an already highly advanced series of technologies (industrial, communicative, medical) does not imply some kind of neo-Luddism, but rather a recognition of what resources already exist and a mapping of production, consumption, and the amount of time it would take, say, to clean polluted waters or to distribute food adequately. This project of decapitalism is not, then, a call for slowing down, a call as open to recapture as acceleration itself (and I appreciate Srnicek and Williams’s attempt to detach acceleration from speed in this respect), but rather a beginning with a recognition of the damage and depletion that has been done and continues to be done, without lapsing into fatalist despair or a desire to fuse with machines, capitalism, and technology and somehow come out the other side (as what?). The version of decapitalism I’m describing starts by recognizing that which is often hidden in plain sight but without which systems, both capitalist and communist, would fall apart.

...(more)

Fillip Spring 2015

via —synthetic zero

photo - mw

_______________________

The Idea of Onto-Cartography

Larval Subjects

(....)

There is no action we engage in that is not supported by the things or beings of the earth. In this respect, all action is distributed. Action does not arise solely from you or I, but is a collaboration of many entities in tandem with one another. Often we don’t notice this because we are so accustomed to the environments within which we act. It takes a special sort of eye, a counter-factual eye, to discern the distributed nature of action.

(....)

There is no less a gravity of language, of signifiers, than there is of things. Signifiers influence our action not only at the level of our cognition and communication with others, but also at the level of our placement within the social field. We can always, of course, adopt our own attitudes towards signifiers, but others have their ideas. The illegal immigrant is caught in the gravity of a signifier: illegal immigrant. At the bio-spiritual level she is no different than anyone else. She has the same intelligence as anyone, she has skills, she’s a perfectly fine person that anyone would be lucky to count as a friend, she speaks the English language fluently and without accent, she is a hard worker, and she has deep and rich friendships with her neighbors. Nonetheless, regardless of what her neighbors and co-workers might think of her, she is caught within the gravity of signifiers pertaining to the law, creating paths along which she must move, services and opportunities available to her, the ever-present possibility of being deported, and so on. The signifier exercises its own gravity, exercising its own power, creating paths along which we move.

(....)

Onto-cartography is not a geographical mapping– though that too –but is a mapping of ecologies of things, of how they function as media for one another creating gravitational relations or relations of human and non-human behavior that afford and constrain what beings are capable of doing. The aim of such a cartography is to achieve escape velocity.

...(more)

Onto-Cartography: An Ontology of Machines and Media

Levi R. Bryant

The Gravity of Things: An Introduction

To Onto-Cartography [pdf]

Levi R. Bryant _______________________

Buster Keaton

returning from France

1934 _______________________

Buster Keaton's Cure

Charlie Fox

cabinet

(....)

That bewildering joke, which suggests that Buster can only speak after laboriously readying his body, plays on the strange fate of silent film stars in our imagination: silence is a symptom of their magical condition. The more of them you watch, the more difficult it becomes to think of them as possessing voices at all. (Would Theda Bara be mute in public, too?) What breeds in silence is, naturally, a sort of excitable noise: heightened fascination, fantastical lore, and outlandish forms of erotic gossip, all of which conspire to hide the dumbstruck star. The uproarious arrival of sound often led these delicate figures into the long and lonely twilight of their careers. The silence that reigned in the cinema twenty years before seemed unspeakably distant and, like the others, Buster had transformed into a relic, an object suitable for gawking audiences and inducing occasionally lyrical fits of nostalgic reflection. But he was able to stage a return when many had retreated into memory or private darkness. The year of his appearance on The Ed Wynn Show, Clara Bow, the actress who had slinked through the world’s erotic dreamscape for much of the 1920s, had been admitted to a mental hospital with a mistaken diagnosis of schizophrenia, then subjected to aggressive electroshock treatment. Ravaged upon release, she abandoned her family and moved into a bungalow near Los Angeles that she seldom left until her death in 1965. Buster was ruined by a slow fall into alcoholism but returned, and yet his rehabilitation and—let’s go for the hysterical mood of melodrama—resurrection conjure up more ghosts. His alcoholism was seemingly cured by a manic, spuriously medical process, and he didn’t quite vanish in the obscure years before its success. There’s plenty of intoxicating material to be found by studying Buster if you dodge the lustrous peaks of his career in favor of going deep into its gloom and supposed dead ends.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Approach of the Horizon

Louise Glück

threepenny review

(....)

So we begin. There is a sense

of gaiety in the air,

as though birds were singing.

Through the open window come gusts of sweet scented air.

My birthday (I remember) is fast approaching.

Perhaps the two great moments will collide

and I will see my selves meet, coming and going—

Of course, much of my original self

is already dead, so a ghost would be forced

to embrace a mutilation.

The sky, alas, is still far away,

not really visible from the bed.

It exists now as a remote hypothesis,

a place of freedom utterly unconstrained by reality.

I find myself imagining the triumphs of old age,

immaculate, visionary drawings

made with my left hand—

“left,” also, as “remaining.”

The window is closed. Silence again, multiplied.

And in my right arm, all feeling departed.

As when the stewardess announces the conclusion

of the audio portion of one’s in-flight service.

Feeling has departed—it occurs to me

this would make a fine headstone.

But I was wrong to suggest

this has occurred before.

In fact, I have been hounded by feeling;

it is the gift of expression

that has so often failed me.

Failed me, tormented me, virtually all my life.

...(more)

_______________________

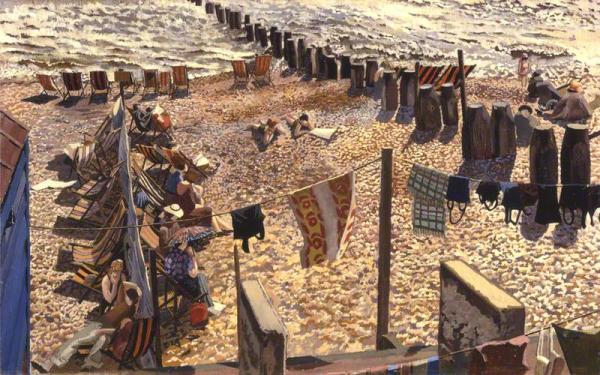

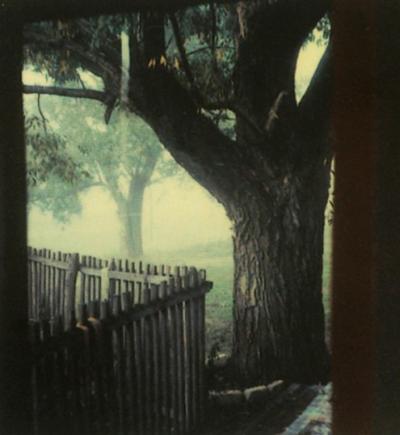

photo by Steve Schapiro

The Polaroids of Andrei Tarkovsky : The Mystery of Everyday Life

1979 to 1984

_______________________

The aesthetics of crisis

Art in arrested democracies

Brian Holmes

eurozine

(....)

... to speak of aesthetics is to speak of art. Yet what I'm looking for can't be reduced to the art object. Instead, I'll refer to what Raymond Williams called "structures of feeling". By that phrase he meant an emergent set of attitudes, of likes and dislikes, enthusiasms and hesitations, insights and constitutive blindnesses that allow people to recognize each other as participating in a shared present, as being on the cusp of something that only they can fully grasp and bring into being. Williams writes: "We are talking about characteristic elements of impulse, restraint, and tone; specifically affective elements of consciousness and relationships: not feeling against thought, but thought as felt and feeling as thought: practical consciousness of a present kind, in a living and inter-relating continuity."

What he's talking about is something so subtle and uncertain that one can well imagine it takes an artwork to even point to such things, and to conjure them up in forms tangible enough to discuss. The aesthetics of crisis is therefore about the forms through which an emergent process of social change becomes perceptible and sensible. By knitting together a certain atmosphere, a range of images, a sequence of rhythms, a set of situations, presuppositions, conflicts and hopes, an artwork can evoke an incipient structure of feeling for a particular group at a particular moment, or for a whole generation.

(....)

So we're talking about aesthetics as a structure of feeling, for a group and especially for a generation. But I'm going to throw in a twist. I'm going to ask about the moments when structures of feeling break down, so that what we sense is not their presence but their absence, their emptiness, their futility. What's more, I want to suggest that there is a structure of the breakdown itself. This broken structure must somehow be given by the dysfunction or collapse of society's most overarching law. In the case of the capitalist democracies, that law is economic.

...(more)

_______________________

Our current system of credit-based capitalism entails not only the material, but the social, moral, and affective estrangement of its subjects. Is there a way out?

All That Is Solid Melts into Air (Again)

David Palumbo-Liu

(....)

... one of the most powerful arguments against debt relief or forgiveness is that those who incur debt are irresponsible spendthrifts who are only too willing to renege on their obligation to “honor” their debts. Debtors get hit with a double-fault: they should have had stronger moral fiber before getting into debt in the first place (and this would be manifested in a strong work ethic coupled with a sense of deferred gratification, so the characterization goes) and after incurring the debt (they should have promptly discharged their obligation to repay). Given this double-fault, debtors should be the recipients of scorn. What is more, their sin is amplified—their behavior threatens to contaminate others, breeding even more debtors. Even worse, they become a drag on the state. Such moralizing impedes any serious understanding of what the debt incurred during and after the 2008 meltdown is actually all about. Here I offer an argument for a countermorality in order to suggest that a different sense of community and a different sense of justice might be in order as correctives to popular conceptions of debt and morality. To do so, it is crucial to first identify a collective harm.

...(more)

Debt

Occasion Volume 7 _______________________

Andrei Tarkovsky

_______________________

the scandal of reality: a response to on wing by róbert gál

Jared Daniel Fagen

3am

How does one describe a work of art which replaces narrative arc and dramatic structure with inquisitiveness and intuition? Art that is uncontrolled, willingly wasting away before it can be contained, that has no purpose or point of departure, and evades definition? Composed in encryptions, aphorisms, recollections, philosophical auspices, and esoteric—almost Delphic—fragments, Róbert Gál’s On Wing is a book of elaborate suffering, withdrawal and extreme impoverishment—an absence of life’s deceits. Gál’s art is both hysteria and euphoria; the world serving only as an instrument of pain, decorating each wound involuntarily resurfaced. For Gál the art, and act itself, of writing is an exercise in dismantling the world about us, a world which operates as a distraction from our fundamental actuality: spiritual flux, the entropy of the soul.

Before that which is unreal unto that which is real, yet elude we must.

Not to see reality in oneself reflects the need to be real.

And when reality stops being a possibility, falling for a possibility, as if it was reality.

To begin with, On Wing requires the senseless reader. It would, therefore, be unavailing to expound similarities to Bernhard, Goethe, Michaux, or Kierkegaard or to compare On Wing to the likes of La Rochefoucauld’s Maxims, the ascetic qualities of Pascal’s posthumous Pensées, or even Schopenhauer’s defense of solitude in Parerga and Paralipomena (or his reflections on women, a proposition that, although interesting to survey, we will not explore for obvious intentions). What must follow, then, can only be a discussion of experiences, of aimless juxtapositions: an intrinsic study—not an excavation. While in itself full of inquiry, On Wing demands a celibate student: someone who lacks a thirst for a didactic, pedagogical knowledge but craves reassurance of his/her own torments.

...(more)

Róbert Gál, On Wing, translated by Mark Kanak (Dalkey Archive, 2015)

_______________________

Andrei Tarkovsky

_______________________

from “Waxing”

by Róbert Gál

Translated from the Slovak by Michaela Freeman

(....)

The past that repeats is proof we did not yet grow enough for what is to come.

It is not a word game but a new way of narativeness.

A lifemotif.

I seek slowness and find only slowing. The world, despite all retouching. The art of infertility.

To know how to write or to know how to structure a sentence?

A self-propelled despair.

Who hasn’t settled yet has nothing to export. When we settle, we can also import.

Incomplete children left behind.

To what degree can others leave us even in that which is “our personal”?

Empathizing in isolation.

A solid structure of the expressed leads to the point in which one truth can predict another.

A story re-told into the logic of tautology.

The fragility of the real, the unbreakability of an expression. The unbreakability of the real, the fragility of an expression.

An aphorism is the author’s form of training in taciturnity.

...(more)

_______________________

Andrei Tarkovsky

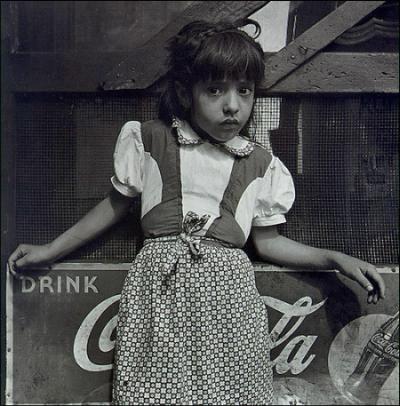

Jerome Liebling

1924 - 2011

_______________________

The Far North of Experience

In Praise of Darkness (and Light)

Rebecca Solni

(....)

Sometimes during that summer when the sky was often gray but never black, I would think that a task had to be done before darkness and then realize that there would be no more darkness while I was there, and it didn’t matter so much when I rose, when I slept, when I traveled. For me day and night were time itself, and I missed the rhythm and structure they provide. I missed stars. Darkness no longer shut me in: I shut light out to sleep. It was as though I had entered a landscape that itself never slept, never dreamed, that never let up the rational alertness of daytime, the light of interrogation and analysis.

The sensuality of night had never been so clear to me, darkness descending like velvet to wrap around you and enclose you in its black cocoon, to take you to your other self and others. In darkness dreams awaken and dreamers merge, which might be how passion becomes love and how making love begets progeny of all natures and forms. Merging is dangerous, at least to the boundaries and definition of the self. Darkness is generative, and generation, biological and artistic both, requires this amorous engagement with the unknown, this entry into the realm where you do not quite know what you are doing and what will happen next.

(....)

When you spend time in the desert, you come to love shadow, shade, and darkness, the respite they give to the menacing blaze of day that burns you out and dries you up. Heat is the desert as predator, just as cold is the Arctic’s biggest animal. Desert light is fierce, and at midday it flattens everything into a harsh solid, but early and late in the day, light is golden and every crevice and fold and protrusion of the landscape is thrown into the high relief of light and shadow. At those times day and night intertwine like dancers, like lovers, and shadows are as powerful a presence as the things that cast them, or more so, growing and growing until the sun disappears below the horizon and darkness spreads like water on the land.

...(more)

_______________________

Morning in Monessen Pennsylvania

Jerome Liebling

1983

Interview with Jerome Liebling

_______________________

After the Flood

Arthur Rimbaud

translated by John Ashbery

No sooner had the notion of the Flood regained its composure,

Than a hare paused amid the gorse and trembling bellflowers and said its prayer to the rainbow through the spider’s web.

Oh the precious stones that were hiding,—the flowers that were already peeking out.

Stalls were erected in the dirty main street, and boats were towed toward the sea, which rose in layers above as in old engravings.

Blood flowed in Bluebeard’s house,—in the slaughterhouses,—in the amphitheaters, where God’s seal turned the windows livid. Blood and milk flowed.

The beavers built. Tumblers of coffee steamed in the public houses.

In the vast, still-streaming house of windows, children in mourning looked at marvelous pictures.

A door slammed, and on the village square, the child waved his arms, understood by vanes and weathercocks everywhere, in the dazzling shower.

Madame xxx established a piano in the Alps. Mass and first communions were celebrated at the cathedral’s hundred thousand altars.

The caravans left. And the Splendide Hotel was built amid the tangled heap of ice floes and the polar night.

Since then the Moon has heard jackals cheeping in thyme deserts,—and eclogues in wooden shoes grumbling in the orchard. Then, in the budding purple forest, Eucharis told me that spring had come.

—Well up, pond,—Foam, roll on the bridge and above the woods;—black cloths and organs,—lightning and thunder,—rise and roll;—Waters and sorrows, rise and revive the Floods.

For since they subsided,—oh the precious stones shoveled under, and the full-blown flowers!—so boring! and the Queen, the Witch who lights her coals in the clay pot, will never want to tell us what she knows, and which we do not know.

_______________________

Men's Hat Shop, Jerusalem

Jerome Liebling

1983

_______________________

Linguistic Anxiety and the Deconstruction of the Self in the Realm of the Ridiculous

J.J. Phillips

exquisite corpse

(....)

Again, when I tried to explain, he insisted that I made no sense. When in frustration I said “Lacan, you know, Jacques Lacan,” he impatiently claimed that he couldn’t understand me and had no idea what or whom I was referring to. Since I’d studied French (though long ago), had read Écrits and some of Lacan’s other writings, and had engaged in a number of conversations about Lacan with various people over the years, among them an acquaintance, a Francophone MFCC, who’d never drawn a blank when I spoke the name, it couldn’t have been my pronunciation unless I’d suddenly lost control of my faculty of speech and didn’t know it. When in desperation I took a pen and paper and wrote down the name “Jacques Lacan,” the doctor grew even more annoyed and again professed ignorance. No matter what efforts I made, he resolutely refused to acknowledge this name and kept dismissively insisting that I wasn’t making any sense and was revealing my pathetic ignorance, not only of French but of English. My continued impertinence was more than he could bear. He had no more time to waste on the likes of me. As he turned on his heel, the corners of his white coat flapped. He left me standing there stunned and mute – to pay my bill for being professionally vilified and go home.

Even if I didn’t know how to spell or use the English word “laconic,” staging this elaborate fit of pique to ridicule me in this manner, and within earshot of his staff, wasn’t ‘just’ a gratuitously cruel and outrageous way to treat anyone, especially someone in a vulnerable psychological state, who’d come to him seeking help. His petulant refusal even to attempt to understand what I was getting at (not to mention refusing to understand me when I was making sense) and casually degrading me as he did, was completely discombobulating and deeply destructive psychologically and neurobiologically. And he got off on it. I wasn’t in training to be an analyst – where I get the impression that such practices are frequently de rigueur, part of the rites of passage; though I also learn that for some, sadistic degradation and mind-fucking patients is a clinical style, which could perhaps be termed Zilboorgian, after Gregory Zilboorg, George Gershwin’s analyst.

The lodestone of my internal compass instantaneously demagnetized. The fear that I might not be making sense, and that even if I was, my words could summarily be declared gibberish at any time without examination, at the whim of any jerk with an engorged but brittle ego and a sadistic streak, stoked my already considerable anxiety regarding my basic linguistic and cognitive competency, and profoundly destabilized my sense of self to the degree that I was stupefied. When I left his office, I hardly knew which direction to take and my otoliths were so rattled that I couldn’t make my way down the street in a straight line or walk without stumbling. It’s a wonder I found my way home without being hit by a car. This was much more than an attack on my psyche and a semi-public humiliation: he was fucking with some critical areas of my brain, and it was a calculated attack. I couldn’t have been made to feel more stupid and worthless, and he knew it. He set me up and sucker-punched me, and I walked out of his office disoriented and reeling just as sure as if he’d actually slammed me in the solar plexus with his fist.

...(more)

|