|

The Gypsy Fires Are Burning for Daylight's Past and Gone

James Guthrie

1859 -1930

_______________________

The Nothingness That Speaks French

McKenzie Wark

Public Seminar Commons

Quentin Meillassoux’s The Number and the Siren (published by Urbanomic and Sequence Press, and elegantly translated by Robin Mackay) is quite simply the most beautiful book by a philosopher that I have read for many years. It is a highly original reading of Stéphane Mallarmé’s Coup De Dés.

If the objective of Meillassoux’s other book, After Finitude, is to be done with the philosophy of consciousness, the objective of The Number and the Siren is to be done with the philosophy of language. This is the other well-worn approach to correlation, which re-inscribed the giveness of the object to the thinking subject as the line that there is nothing outside the text, or no outside-text.

Mallarmé’s Coup De Dés Jamais N’Abolira le Hassard aka A Throw of Dice Will Never Abolish Chance, is a key source for those playful, effervescent philosophical and literary-critical languages – Blanchot, Derrida, Kristeva, Ranciere – one suspects Meillassoux of wanting entirely to leave behind.

...(more)

.....................................................

Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard

(A throw of the dice will never abolish chance)

Stéphane Mallarmé

Translated by A. S. Kline

another translation by Jim Hanson

_______________________

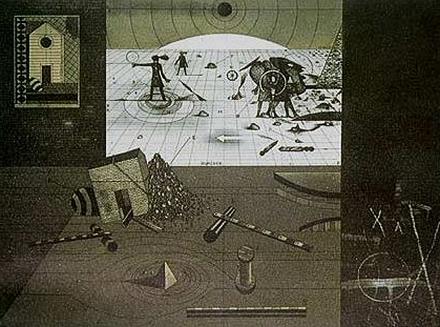

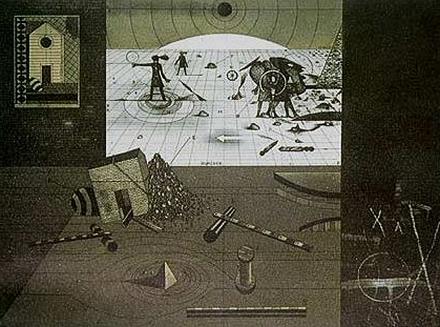

Business

Charles Demuth

1921

_______________________

Rainy Fascism Island

Nina Power

e-flux

How to characterize this period post-crash, or post-post-crash if we assume that the measures taken (austerity, the destruction of the welfare state) have largely been set in motion, if not completed?1 The deliberate shifting of blame that saw the public sector punished for the crimes of the private allowed various other modes of the dis- or rather misplacement of resentment to be mobilized. The targets are the same as they ever were—migrants, the un- or underemployed, those in need of help or support—but, given that the structures that enabled help and support had largely been dismantled even before “austerity” measures were imposed, there seems little left to attack. Those outraged by people receiving benefits, or those telling people to just get a job, must know that what meager benefits there are do not support a life, and that in many places there simply are no jobs to get. But nevertheless, resentment remains, or at least, somehow, a fantasy version of it can be mobilized such that resentment acts as a kind of looping device, self-nourishing and ever-expanding. What should we call this state of affairs? How best to identify it, in order to redirect or dismantle its energies?

(....)

There is nothing really new about much of this, apart from the rapidity with which the directed and stage-managed misplacement of resentment happens. Those who are the most privileged believe that they, above everyone else, are the true victims, suffering from a lack of sovereignty, a lack of enjoyment: the last people who should be begrudged are the first to be hated by those who have the most.

...(more)

_______________________

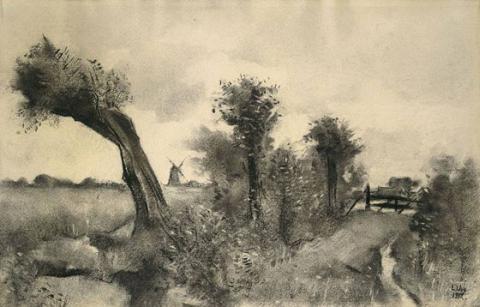

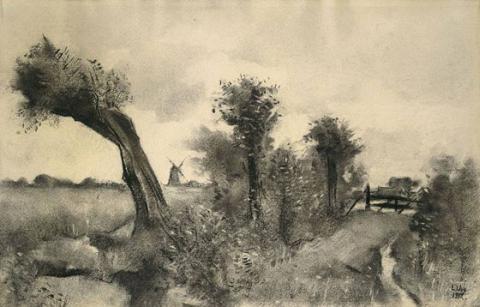

The Last Turning

James Paterson

1854 - 1932

via

_______________________

‘We’re All Surrealists Now’: An Interview with Will Self

By Mike Doherty

(....)

I don’t think that art is the mirror of life, and I think that there are real problems with naturalism as a concept. It seems self-defeating, and I’ve always understood that, and that’s why I’ve never written naturalism as commonly understood.

(....)

... the straightforward Swiftian thing remains implied in my writing. What you get in Gulliver is essentially an anthropologist’s perspective on humanity: it’s that great phrase Oliver Sachs used for his book, An Anthropologist on Mars. My authorial perspective in a lot of the texts has always been that of an anthropologist from another planet approaching Earth. If you view human behaviour as a subset of animal behaviour, then inevitably it appears grotesque. It only appears non-grotesque looked at from within self-censoring human perspectives, [including] books and artworks in which nobody shits.

(....)

... the way we think about our lives necessarily partakes of social and culturally sanctioned schemas, whether they’re as simple as the calendar or how much we weigh or what’s written on our cv. Our inclination to place ourselves in that common-sensical structure is always being undermined by our actual mental content. It’s Magritte, isn’t it? Or Freud: “In our dreams, we’re all surrealists, but in our lives, we’re bourgeois.” I think we’re all surrealists.

...(more)

_______________________

The Masque of the Red Death

Charles Demuth

c. 1918

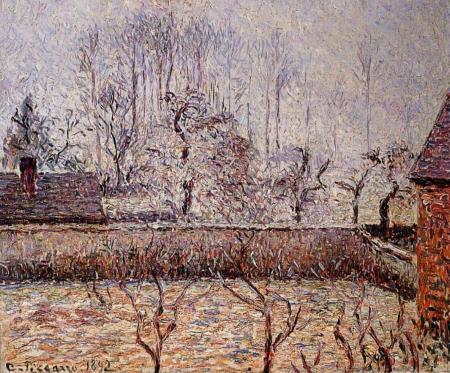

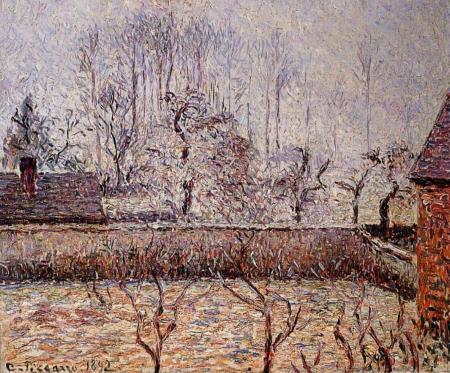

Frost and Fog, Eragny

1892

Camille Pissarro

d. November 13, 1903

_______________________

Now This is Now Happening Now is This Now: An Essay

Loie Merritt

lemon hound

Introduction: [Listen]

Between the wheels of a subway train and its tracks or off the crags of stones or even the space between your dog’s toes, between a curtain and its stage, or the air vibrating between two bodies, we may hope to find a world apart. Where time envelops space, shadowing it, scrambling it and then gluing it back together in a different scene, in quiet, anxiety-ridden hovels of pleasure lifted from pain. This is happening now. Unobjectionable inexpressibility is best formulated by overwhelming all of the senses. How do we attain sensorial overload? Where do we find such drastic heights or such terrifying depths? Lights go out, shadows fall, the players emerge, this is the avant-garde. Longinus’ stenographer can’t stamp out the rules any longer. Rhetoric fails in shadows. We are left naked in our own production, subject to sensual whims of the blissfully blasphemous sublime. [Stop the noise now]

...(more)

_______________________

from Against the Current

Tedi López Mills

translated from the Spanish by Wendy Burk

(....)

How always the cipher appears

under every avatar's line.

—César Vallejo (trans. Rebecca Seiferle)

Synthetic saint, my saint, my rat-and-plaster street, my alibi of imagined

mosaics among veins of a gold hardly to be recognized as such,

gold of an air that goes against gold, no one's gold, my habitual turn of phrase:

once more I don't know what I know, leafless trunk, hollow wood left over

when I construct myself, splinter of mine, not again, the bolt jumps out at me,

lacking the tools I postpone myself, pause of mine as I hear the structure,

the street itself where a sound is polished until it is as seditious as its idea,

undermining wary sight, look at the park, the park as process,

reality's onset, displacing the tree towards its archetype

when there is no story in reserve, no world inserted

with room to hold it, reticent brother, tugged by my refrain, the past

is only a duplicate of death, a worthless card, there's hallway enough for the long queue,

...(more)

Asymptote October 2014_______________________

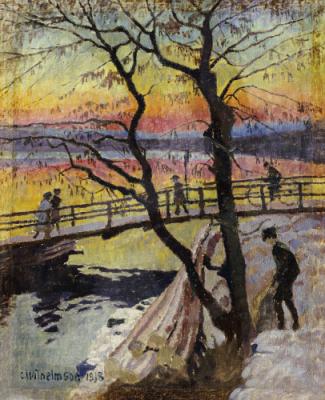

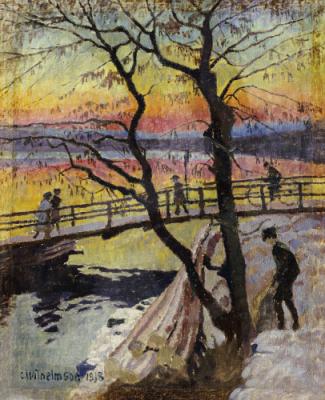

The Footbridge, Lidingobron

1918

Carl Wilhelm Wilhelmson

b. November 12, 1866

_______________________

Separating Flesh From Bone

Trip Starkey

full stop

Humans understand ourselves as the earth’s great dominion-bearing beings. We have used that dominion as an excuse to ransack our world, tearing limb from limb, until it became an unrecognizable web of asphalt and damaged landscapes. Mountains have been toppled in search of resources, while ocean and atmosphere have been plugged with our chemical waste. Living organisms are sacrificed daily in the name of human progress. We boast in these accomplishments, delight in converting verdant trees into verdant dollar bills.

In recent years, the figurative scales have shifted, and the very real threats of irreversible, life-altering damage have emerged at the forefront of world issues. Nature, if not from sheer frustration with the exploits of our race, has continued to act out in violence, warning us of its displeasure. Now, more than ever, there is a need for returning to the literature penned in nature’s defense. However, as we do this, we must be weary of blindly accepting the ideas of nature’s past prophets. We must avoid falling into the same old wooden elucidations, which obscure the notion that this world in which we live is fully alive. Instead, we must separate the dead bones of outdated thought from the lively flesh of our world. Literature overflows with perspectives on how we ought to carry ourselves as citizens of the natural world. It is up to us to wade through this ocean of thought, and emerge with more refined translations of the wild tongues that seek to save us from our own destruction.

...(more)

_______________________

footpath, Pontoise

Camille Pissarro

1874

_______________________

Fallen Angel

The tragic life and enduring influence of critic Walter Benjamin

Ian Penman

city journal

(....)

Some of the current vogue for Benjamin may stem from our nostalgia for the vanished dream of grand European culture to which he belonged. Photographs of Benjamin at work in elegant libraries, or strolling along tourist-free Mediterranean streets, provoke feelings of awed and envious benevolence. In today’s insipid, rigorously PC academy, Benjamin represents a burst of real flavor. He’s kind of sexy, by academic standards. As well as doing literary criticism (and conducting a pitiless interrogation of the status and value of same), he also wrote about window displays, travel, children’s books, drugs, food, and films. The gorgeous One-Way Street (1928) reads like a textual kaleidoscope: a glinting mix of views, shadows, memories, and jokes. His is a nomad thought: unmoored and unhurried, sometimes flinty, sometimes a bit vague and stoned. Benjamin works in starts and stops, to a strange fugue-like pulse. His sentences have a hesitant, leaning rhythm, not unlike the playing of Thelonious Monk: you’re never quite sure where the next emphasis is going to fall.

Benjamin was a stroller around the boundaries between serious thought and everyday pleasures, high culture and low tastes. His preferred place to think from was always a threshold. Sentences are constructed from memories of holiday walks, sundowner moods, and the rhythms of travel. There are deep sallies on baroque theater and the metaphysics of illusion—but also chatter about children’s-book illustration and how fish is prepared in Marseilles. When he produces what’s ostensibly a travel piece, it supplies the required “local color” about cooking smells and religious customs but also other, less wonted, observations: how porous Naples feels, a subtle commingling of private and public space so that you can no longer tell one from the other: buildings for which you don’t know if they’re still being built or slowly falling into vacancy.

(....)

Neither capitalism, nor fascism, nor the cruel whims of the marketplace finally extinguished Walter Benjamin. His own life killed him—a sudden overdose of time. He hobbled his own escape route with a prevaricator’s endless last-minute stalling: adjusting the sail and testing the wind. He had always had periods when he was unable to think, move, or see a way forward. Eiland and Jennings refer to intermittent periods of depression—but this is very much a postwar reading and not at all the same thing as melancholia, in the vital and many-edged sense that this word had for Benjamin. In The Anatomy of Melancholy, Robert Burton includes in the class of those most subject to saturnine humor: “such as are solitary by nature, great students, given to much contemplation, and lead a life out of action.”

...(more)

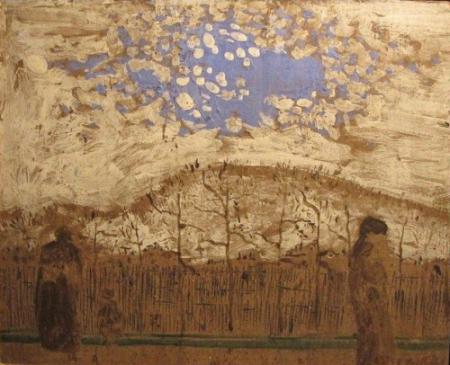

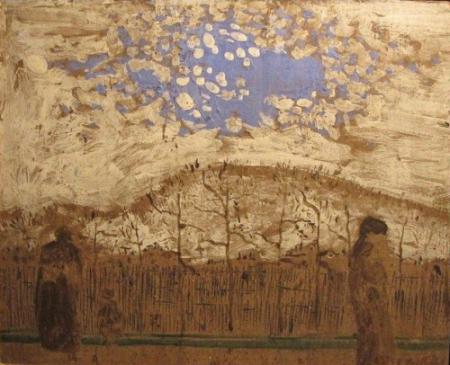

Suburb

c.1900

Édouard Vuillard

b. November 11, 1868

_______________________

Nietzsche and the Burbs

Lars Iyer

The sister-principle, he says. The suburban-principle.

Even if she lost her job, she knew she could find a new one. Even if she was passed over for promotion, she knew it was only a matter of time before she, too, was promoted. This world was hers.

To hear her talk about her work-world, the corporate world, was to know that he could not possibly succeed in that world. That he could in no way get on in her world. To listen to her hold forth on hirings and firings, of targets and headhunts, made it clear that, whatever else, he should follow a path entirely different from his sister. It was to accept that there was no place for him, or for people like him, in the suburbs. That he could not possibly thrive in the suburbs, as she could. That he could in no way advance into the suburbs, as she could. That he was set up for failure – for complete and utter failure – in the suburbs.

...(more)

_______________________

Crepuscule d'Hiver

Gustave Marissiaux

1908

_______________________

The dead speak kindly

Tua Forsström

Translated by David McDuff

books from Finland

(....)

The thing with sorrow is that one thought there

was a fire but it is starting to rain. The brushwood smokes

listlessly for a while, it is far too sparse or dense

and on the field remains a dark installation sprawling

to the sky. The smoke from the clear evenings in April has

stuck in the jacket in the hall. Far from the city’s lights

So many years have passed, but flakes detach at the slightest breath

and blow out across the lake and up toward the house where I lived

with my parents and my brother, in our family.

(....)

The next chapter is called: before we forget

The next chapter is called: the darkness

the rain the kindness

It is already October and blowing hard

I must drive firewood home

I must turn the key in the lock

And then I hear again that voice,

mysterious and clear

You are old now little child

don’t be afraid little hare

...(more)

_______________________

For it is not we who know, but rather a certain state of mind in us that knows.

Kleist -- On the Gradual Formulation of Thoughts while Speaking

excerpted at flowerville

Language is as such no shackle, no brake-shoe, as it were, on the wheel of the intellect, but rather a second, parallel wheel whirling on the same axle. It is something else altogether when the intellect is done thinking through a thought before bursting into speech. For then it is obliged to dwell on the mere expression of that thought, and far from stimulating the intellect, this has no other effect than to let the steam out of excitement. Therefore, if an idea is expressed in a muddled manner it does not at all necessarily follow that the thinking that engendered it was muddled; but it could rather well be that those ideas expressed in the most twisted fashion were thought through most clearly. ...(more)

_______________________

Cold Mountains and Withered Trees

1938

Kagaku Murakami

d. November 11, 1939

_______________________

The History of Men

Jack Gilbert

1925 - 2012

It thrashes in the oaks and soughs in the elms.

Catches on innocence and soon dismantles that.

Sends children bewildered into life. Childhood

ends and is not buried. The young men ride out

and fall off, the horses wandering away. They get

on boats, are carried downstream, discover maidens.

They marry them without meaning to, meaning no harm,

the language beyond them. So everything ends.

Divorce gets them nowhere. They drift away from

the ruined women without noticing. See birds

high up and follow."Out of earshot," they think,

puzzled by earshot. History driving them forward,

making a noise like the wind in maples, of women

in their dresses. It stings their hearts finally.

It wakes them up, baffled in the middle of their lives

on a small bare island, the sea blue and empty,

the days stretching all the way to the horizon.

_______________________

The Florist

Édouard Vuillard

_______________________

e-flux journal issue 59: Harun Farocki

An Archaeologist of the Present

Christa Blümlinger

Translated from German by Leon Dische Becker.

(....)

Farocki’s oeuvre bespeaks a consistent interest in forms of migration. He parsed the official depiction of migration in his video In-Formation—which he called “a silent movie”—and found myths of cultural difference, sedimented in language regimentation and pictograms. He himself was a passionate Berliner, always attached to his respective neighborhoods, but also a frequent and distant traveler, a “rocketeer,” as he liked to say. His interest in migration was related to a foible for the rootless—as described by philosopher Vilém Flusser, with whom he was in dialogue. No surprise then that the only actor Farocki ever dedicated an entire film to, was Peter Lorre, the lost one (Der Verlorene), whose “double face” he read as a palimpsest of transatlantic movements. Perhaps it was this interest in migration (also in the sense of translation) that inspired him—like Pasolini—to study gestures, one of his central projects.

...(more)

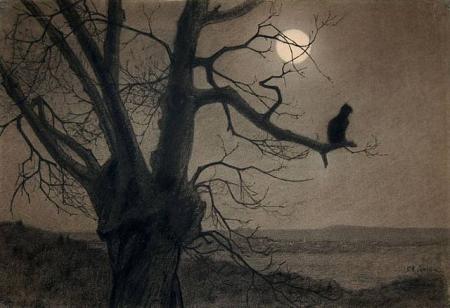

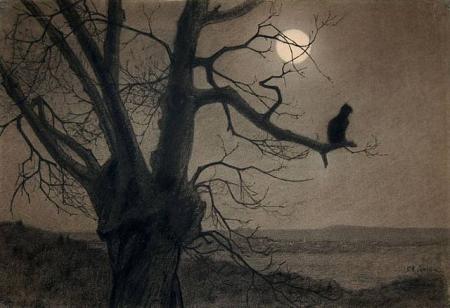

Chat au Clair de Lune

c. 1900

Théophile Steinlen

b. November 10, 1859

_______________________

Dear darkening ground,

you’ve endured so patiently the walls we’ve built,

perhaps you’ll give the cities one more hour

and grant the churches and cloisters two,

And those that labor—will you let their work

grip them another five hours, or seven

before you become forest again, and

widening wilderness

in that hour of inconceivable terror

when you take back your name

from all things.

Just give me a little more time!

I want to love the things

as no one has thought to love them,

until they’re worthy of you and real

.

I want only seven days, seven

on which no one has ever written himself –

seven pages of solitude.

Rilke's Book of Hours

Rainer Maria Rilke

translations by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows

google books

_______________________

Nature Morte Au Damier / Rhum / Bass

1912

Louis Marcoussis

1883 - 1941

_______________________

An Army Of Dead Girls: Art’s Avant-Garde

Joyelle McSweeney

lana turner

(....)

This avant-garde, this army of Dead Girls, shakes the sun from the sky and replaces it with ornament, “orfebrería,” Art’s insignia (“as Grecian goldsmiths make / Of hammered gold and gold enamelling”?), stretching its own skin painfully up to replace the sky in counterconquest. When Art’s army arrives, it immediately enacts a regime of Anachronism. With and/or logic, it insists both on a dream interval and a fatal interval: this is not going to stop until you wake up so give up. Art performs both massive and trivial transformations—the dead are reanimated (a massive change), while a series of lyric, decorative images are daisy chained to each other with a twist of Art’s, or syntax’s, hand: pájaros become nenas como flores. Thanks to Art’s friable power, every surface is touched, changed, made to host each other, to and/or. The odd word order of Jen Hofer’s translation of the final sentence conveys this denaturing of rank, privilege, order, even the separability of bodies. The uncertain doubling up of roles and agencies in the final sentence—“Someone placed on our mask your lip”—points to the forceful and/or of Art’s regime. In this violent remaking of the world, the Dead Girls are Art’s avant-garde:

Caminamos distantes y vacías antes de amenazar. Somos tus lobelias de piernas preferidas. Cada vez que agredimos es como darte un beso. Danos la presidencia o la dirección de los disparos. Somos los frutos frescos de la guerra.

We walk distant and empty before threatening. We are your lobelias with the legs you favor. Each time we attack it is like giving you a kiss. Give us the presidency or the direction of the gunshots. We are the fresh fruits of war. via the page_______________________

Louis Marcoussis

_______________________

1st March: Ain Kiniyya

by Yves Berger

translated by John Berger

Spring covers with a green

exiles never forget

the hills where wandering herds

graze the growing grass

Women stooped between olive trees

clasp in their motherly hands

sage wild thyme and zatar

herbs of an inherited tongue

Rain extracts from dust

its secret treasures

camomile poppy and cyclamen

a coloured carpet of cries

The blood of the red earth

bleeds on a bed of pebbles

whilst the wind blows away

the pines of the settlements

The folded strata of rock

trace the lines of a time

when oceans displaced

mountains before men

photo - mw

_______________________

“The Fair-haired Princess” and Serious Literature

Can Xue

Translated from Chinese by Karen Gernant and by Chen Zeping

(....)

I grew up with books as my companions. Ever since I was very young, I regarded some books as “serious works.” One couldn’t understand them immediately. I could access them only after I “grew up.” Father’s bookshelves held “serious works” on Western philosophy including books by Marx and Lenin. The most conspicuous were the blue-covered volumes of Capital and several sets of the history of Chinese classical literature. Father read from these books every day for years. He read most of them over and over again.

These books emitted a special smell that drew me into reverie. Whenever I was alone at home, I loved to place these books on the table one by one and pore over them carefully. I would smell them up close and touch them repeatedly. The bindings of all of these books were unadorned and exquisite, and the pages were filled with Father’s notes. At moments like this, the emotions in my young heart soared beyond admiration and rapture. At the time, I also began reading books, most of them light literature. I couldn’t classify them together with Father’s books. I hungered for books that could keep me enthralled temporarily. After I read them, I was finished with them. I had no desire to keep them. And I couldn’t have kept them, even if I’d wanted to, for most of the books were borrowed. In those days, who could afford to buy books?

Father’s books stood quietly on the bookshelves—always silently luring me toward them. Subconsciously, I sensed a very profound world in those books. It would cost a person a lifetime to enter that world in depth. Father read those books at night, every night, for years. His contemplative expression behind his spectacles was certainly not a pose. What reading stirred up in his mind was much different from what I felt when I read ordinary books. What was that? No one could tell me—not even Father himself. He said only, “In the future, you must read all of my books.” Did he mean that in the future I should do as he had done—sit in front of the same book for years, steeped in meditation? I didn’t understand.

...(more)

_______________________

Hans Thoma

d. November 7, 1924

_______________________

Packing My Library

George Prochnik

conjunctions

1.

Every day when I step out of my home to walk through the streets of my little Brooklyn neighborhood, I come upon boxes of books outside entranceways, on walls, and at the curb between garbage bags. Sometimes one box. Sometimes half a dozen. The houses with their stiff façades of brick and brownstone are steadily, inexorably disgorging their books. Coughing up volumes of D. H. Lawrence and Loire-region travel guides. Spewing Edith Wharton and Chinese cooking secrets. Vomiting old histories of Middle Eastern politics. The houses are terribly sick—bloated, congested, sclerotic—and they have undertaken a book cleanse. Some bright Sunday I expect to find the sidewalks buried in shiny paperbacks and tattered old hardcovers. Will I be able to wade through them? How deep will the book flood become?

Encountering a particularly huge regurgitation of literature, I glance up at the windows of the house from which it originated, wondering what happened inside to bring on this vast discharge. But the rooms are always still and dark. Always! Shouldn’t some great commotion signal that a crisis has come upon this residence? Shouldn’t, at the least, curtains be fluttering and cats be jumping for their lives? Are the inhabitants of these houses dead? Are the little unlit pyres of books before their doors announcements of mourning? How did I miss the moment when it was determined that the laying out of books before one’s house would indicate a corpse within?

...(more)

_______________________

Adam Kuehl

_______________________

Brief, Image, and Etymology: On Reading

Ryan Flaherty

conjunctions

To read is to be, for a time, text, but how? Say a text is allowed to enter the self and establish its distillment and pattern, why does this cause things to happen?

(....)

Discomfiting, perhaps, perhaps illuminating or predatory, but nevertheless the text shakes out its tent in the skull. Between self and text, energy is indisputably born. Out of nothing, a genesis, a will that is more the text’s than the author’s will, more the text’s than the self’s.

...(more)

_______________________

Lesser Ury

b. November 7, 1861

Everett Shinn

b. November 6, 1876

_______________________

Foucault once expressed his wish that he could write like Blanchot, on the precipice of genres, gazing into the void that lies just beyond their boundaries.

Maurice Blanchot and Fragmentary Writing

by Leslie Hill

Reviewed by Michael Krimper Make

(....)

By putting itself into jeopardy, fragmentary writing at once generates and thwarts itself. Language pours out of this gap that interrupts any definitive beginning or end, without itself coming to an end. A revealing passage from The Writing of Disaster, cited by Hill, helpfully illustrates this remarkable power of contestation. Blanchot declares that “fragmentary writing might well be the greatest risk. It does not refer to any theory, and does not give rise to any practice definable by interruption. Even when it is interrupted, it carries on. Putting itself in question, it does not take control of the question but suspends it (without maintaining it) as a non-response.” Blanchot’s texts are certainly destructive, but they simultaneously appeal to a principle of freedom at the origin of all literature—that is, a principle that lets us say and contest everything. And yet, in characteristically Blanchotian fashion, this freedom must call itself into question, for the fragmentary disrupts all claims to authority, including its own. It threatens to undermine any form of authorization that could be attributed to the subject, whether of the author, reader, or language.

Hill calls this questioning “sovereign disobedience,” and he helpfully links it to Blanchot’s crucial notion of the neuter (le neutre). The neuter refers to the grammar of the impersonal but more importantly evacuates language of subjectivity. Blanchot says that an altogether other voice than the “I” speaks in literature. Whether in the give and take of speech between multiple interlocutors, or the counterproductive movement of waiting, the impersonal language of the neuter suspends oppositional forces in the text without resolving them. Unlike dialectical thought, as elaborated by Hegel, the neuter neither affirms nor negates being. Literary language resides in a space of the excluded middle (neither something nor nothing). It retracts what it says while crossing out the steps of erasure. And through this movement, the neuter interrupts the mediating power of dialectics, which Blanchot and others in France at the time associated with the violence of totality and appropriation. Whereas the labor of the negative always reduces the other to the order of the same, the neuter welcomes the irreducibility of the other. It gradually undoes the work of literature whose organizing principle synthesizes contradictory positions into an integrated whole. Whereas dialectics gathers everything into unity (such as the state, national language, and a work of art), the neuter restlessly disperses identity and affirms in turn the multiplicity of difference.

...(more)

via ReadySteadyBook

_______________________

Fleishman's Bread Line

Everett Shinn

_______________________

People connect to each other here, is what I’m saying. They get to know each other and they treat each other well. If Twitter is people you don’t know at their wittiest, and Facebook is people you do know at their most mundane, then MetaFilter, I would say, is a family of strangers.

The Internet’s First FamilyStephen Thomas hazlitt

Founded in 1999 by Matt Haughey, a.k.a. mathowie, who worked on an early version of Blogger, one of the first-ever blogging platforms (which was eventually bought by Google), MetaFilter is a venerable institution in a context—the Internet—where the phrase “venerable institution” is only maybe just beginning to acquire a non-ironic usage.

(....)

Nominally, MetaFilter is a venue for people to talk about things other people have done, intelligently and with respect for each other (if not necessarily for the thing being discussed), and a small number of people are paid well to ensure this is what happens. All of this, it seems, adds up to a place with a premium on humility and other-centeredness. Of course, members’ opinions, perspectives, and anecdotes come out inevitably and regularly in the comments, and are in many ways the lifeblood of the site. But the fact remains that structurally, the users’ main input to the site—their comments—are secondary, appendageal, or, looked at another way: supportive.

...(more)

via Dangerousmeta!

_______________________

An Information Guerrilla Reader

assembled at Deterritorial Investigations Unit

_______________________

Brilliant impersonators

Kat McGowan

aeon

... Throughout human history, innovation – including the technological progress we cherish – has been fuelled and sustained by imitation. Copying is the mighty force that has allowed the human race to move from stone knives to remote-guided drones, from digging sticks to crops that manufacture their own pesticides. Plenty of animals can innovate, but no other species on earth can imitate with the skill and accuracy of a human being. We’re natural-born rip-off artists. To be human is to copy.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Diversifying Translation

Daniel Goulden

Asymptote Blog

(....)

The very act of translation heightens the vitality of the languages it connects. It broadens the array of people that the source language can speak to and transforms the function of the target language. The world that Goethe envisions is a world where literatures complement and complicate each other. When larger languages drown out smaller ones, World Literature loses the crucial elements that make it an endeavor worth pursuing.

The era of World Literature is perennially at hand. Just as World Literature has changed since Goethe first conceived it, we need to make the effort to change it from its current form. In order for World Literature to diversify, translators must first make the effort to diversify both in the regions they choose their work, and the languages they choose to translate. In doing so we can add to the vitality of global literature, while demonstrating that translation is not just an art form, but a way to build global equality and understanding.

...(more)

Hannah Maynard

1834-1918

.....................................................

Dark Room

Susan Rich

common-place

Tricks a Girl Can Do

Hannah Maynard (1834-1918) was a Canadian photographer who

created surreal images after the death of her daughter; she was a proto-surrealist.

I will hang myself in picture frames

in drawing rooms where grief

is not allowed a wicker chair

then grimace back at this facade

from umbrella eyes

under a cage of silver hair.

Look! I've learned to slice myself in three

to sit politely at the table

with ginger punch and teacake;

offer thin-lipped graves

of pleasantries.I develop myself

in the pharmacist's chemicals

three women I'm loathe to understand—

presences I sometimes cajole

into modern light and shadow;

we culminate in a gelatin scene—

a daughter birthed from a spiral shell,

a keyhole tall enough to strut through. ...(more)

_______________________

Feminism: The Men Arrive!

(Hooray! Uh-Oh!)

Rebecca Solnit

(....)

I care passionately about the inhabitability of our planet from an environmental perspective, but until it’s fully inhabitable by women who can walk freely down the street without the constant fear of trouble and danger, we will labor under practical and psychological burdens that impair our full powers. Which is why, as someone who thinks climate is the most important thing in the world right now, I’m still writing about feminism and women’s rights. And celebrating the men who have made changing the world slightly more possible or are now part of the great changes underway.

...(more)

_______________________

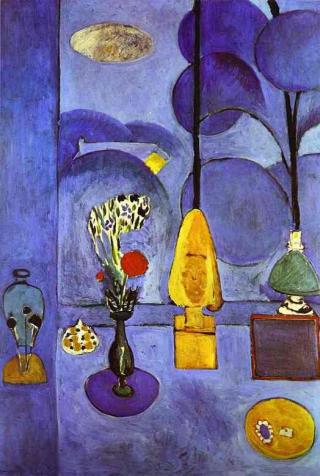

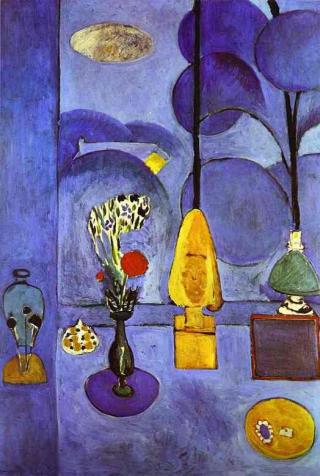

The Blue Window

1911

Henri Matisse

d. November 3, 1954

_______________________

Local Nomad - issue one

Fall 2014

Migration

Migrations forced or voluntary; swept up by the tide, sparked by desire, fear, tradition, labor, or exploration; earthly and/or otherworldly routes, walkabouts, or interior migrations; arrivals and departures, beginnings and ends, traces left along the way; lines connecting, disconnecting, or broken; lines drawn that you do, or do not cross.

In this issue: Tom Beckett, Michael Caylo-Baradi, Jack Crimmins, M. A. Fink, Peggy Heinrich, Márton Koppány,

Sheila E. Murphy, Barbara Jane Reyes, Margaret Rhee, Eileen R. Tabios, Maria Garcia Teutsch, Mark Young, and

J. Zimmerman.

Poems

Jack Crimmins

Poetics #2

the old cellist

comes to grieve

his mind is going

wild lilac

the Dry Mountains

in sight of the Inyo Mountains

language as the water

inlet

knife blade

dusk

one hundred miles from Alturas

double hummingbird and the early work

...(more)

_______________________

Tethered To The Fortunes Of Writing

Kimberly Nichols interviews Alain De Botton

3am

(....)

I'm familiar with the way that you can read a book and seem to agree with its conclusions, then ten days later, your life seems out of synch with everything you read and agreed with. That's why re-reading is important and also creating environments in which certain ideas you have sympathy with are given currency. The problem with much mass media is that it subtly forces us to abandon our thoughts in order to concentrate on things which we actually don't care that much about -- but are made to feel as if they were important. As for my ambitions with my writing, I'm just trying to make sense of the world for myself -- so as to reduce my levels of anxiety.

...(more)

_______________________

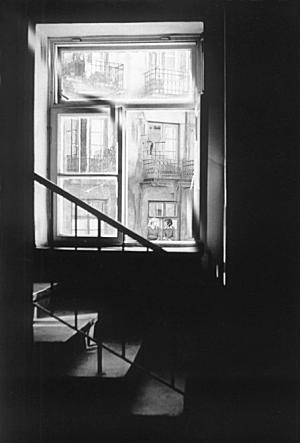

Lublin

1974

Michal Cala

_______________________

Maps, Thresholds and Beaten Tracks: A Photographer in the City

Text by Edward Welch. Photographs by John Perivolaris

berfrois

(....)

...the city’s beaten tracks are places where its libidinal, economic and symbolic energies are channelled and concentrated. They are locations of flow, communication and contact; but they can also be liminal places, constituting boundaries and thresholds, and producing moments of crossing, transition and change. For Benjamin, ‘nowhere, unless perhaps in dreams, can the phenomenon of the boundary be experienced in a more originary way than in cities’. If this is true for all cities, it seems especially to be the case of Paris, which in many ways is structured and defined by threshold locations: entrances to arcades and metro stations; boundaries between arrondissements; the ring road, or boulevard périphérique, which follows the line of the city’s nineteenth-century defensive wall, and divides it from the suburban sprawl beyond.

...(more)

_______________________

OTOLITHS issue thirty-five

_______________________

Installing (Social) Order

a blog on the sociology of infrastructure, exploring the sociotechnical nerves of contemporary society. Originally formed as an informal work group of researchers at Bielefeld University´s Department of Sociology, it is open for participation.

Martin Martinček

1913 - 2004

_______________________

Sitting Outside at the End of Autumn

Charles Wright

Three years ago, in the afternoons,

I used to sit back here and try

To answer the simple arithmetic of my life,

But never could figure it—

This object and that object

Never contained the landscape

nor all of its implications,

This tree and that shrub

Never completely satisfied the sum or quotient

I took from or carried to,

nor do they do so now,

Though I'm back here again, looking to calculate,

Looking to see what adds up.

Everything comes from something,

only something comes from nothing,

Lao Tzu says, more or less.

Eminently sensible, I say,

Rubbing this tiny snail shell between my thumb and two fingers.

Delicate as an earring,

it carries its emptiness like a child

It would be rid of.

I rub it clockwise and counterclockwise, hoping for anything

Resplendent in its vocabulary or disguise—

But one and one make nothing, he adds,

endless and everywhere,

The shadow that everything casts.

_______________________

Martin Martinček

_______________________

Words without Borders

November 2014: Contemporary Czech Prose

The Prodigal Father

Tomáš Zmeškal

Translated from Czech by Alex Zucker

A writer can rarely stop paying attention to the language people speak. A professional deformation, a sort of neurotic self-harm through words, since for an author, language is the most important thing. The most important conversations I had with my relatives about my coming to Congo always had a tone of importance to them. My coming there was important, and so it was spoken of in that way. Notice what register of language people are using with you, I used to tell my students at university. Is it ceremonial, familiar, official, frivolous?

But my family wasn’t the first African family I knew. Without realizing it, I had been studying Africans my whole life. That doesn’t mean I understood them, but my whole life I had been collecting knowledge and personal experience, which unconsciously had risen to the level of generalization in my mind. Every bit of information was engraved there, never to be forgotten. My father, I suspected, might be the same as them, so what were they actually like? It still surprises me what an extensive repository of information I carry around in my skull on the Africans I’ve met. That subconscious storing away of facts, of unsubstantial details, of absolute trivialities was consistent, whatever the occasion we met and in whatever country. Whenever I was introduced to anyone from Africa, a recording device started up, taking down everything meticulously. To a certain extent, of course, it was part of a phenomenon that every prose writer goes through. Namely, that phase of boundless observerdom which every beginner is condemned to initially, at least until he finds his own voice, his own themes, until he discovers what his writing is actually about. George Orwell wrote that true literature begins when the author breaks free of the first person and enters the third. This view might not entirely fit with contemporary literary theory, but it’s an incredibly powerful one for assessing an author’s attitude toward himself and his themes. For highlighting the psychological gap between narcissism and literary tradition, dating at least as far back as Balzac.

...(more)

_______________________

Martin Martinček

_______________________

Briefly Considered: Sub-Plots

Adam Weinstein

conjunctions

(....)4.

The history of gardens is a history of order. Consider the Persian chahar bagh, which is divided into four quadrangles to represent the four corners of the earth. Here the garden’s order is an analogue to pure, universal geometry. Or the Japanese kaiyu-shiki-teien, which uses miegakure to guide the visitor along a carefully chosen path. And finally the Victorian garden, whose special order is that of imperialism and conquest.

The garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection.

—Foucault

The sub-plot, on the other hand, refuses order. Once the space is constructed, it signs an impossible ontology. Thus the sub-plot is marked with the image of the obolus, which carries a double meaning. On the one hand, the obolus is the shell of a clam. Although the lines of the shell are drawn in radiating concentric circles, they end at the crustacean’s lip. Yet here begins the clam’s double, its second half, where the radiating turns back toward its source, from the largest circle to its most minute at the hinge—and again, and again. It is fitting, then, that the obol is also the coin given over to Charon. We cross the river Styx clutching empty space, a shape that mirrors itself in hollows of calcite. We return to the place from which we perpetually depart.

But obolus is also oubliette (in Latin, oblivisci): absolute interiority. Closed and locked, it is a room without language. One cannot speak of the sub-plot, but only its skin. Once it is covered with palm leaves, laid with fresh soil for seeding and planting, and then grown thick with vegetation, the sub-plot is dream, and the dream is always already obliterated the moment it is enacted—oblivisci, forgotten.

Instead, we may lie down in some garden and close our eyes and test the space by thunking upon it.

...(more)

_______________________

Martin Martinček

Imaginary bridge

Hannah Höch

b. November 1, 1889

_______________________

The dead speak kindly

Tua Forsström

Translated by David McDuff

books from Finland

(....)

The thing with sorrow is that one thought there

was a fire but it is starting to rain. The brushwood smokes

listlessly for a while, it is far too sparse or dense

and on the field remains a dark installation sprawling

to the sky. The smoke from the clear evenings in April has

stuck in the jacket in the hall. Far from the city’s lights

So many years have passed, but flakes detach at the slightest breath

and blow out across the lake and up toward the house where I lived

with my parents and my brother, in our family.

The next chapter is called: before we forget

The next chapter is called: the darkness

the rain the kindness

It is already October and blowing hard

I must drive firewood home

I must turn the key in the lock

And then I hear again that voice,

mysterious and clear

You are old now little child

don’t be afraid little hare

...(more)

_______________________

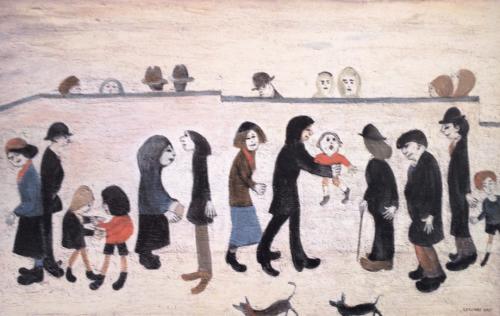

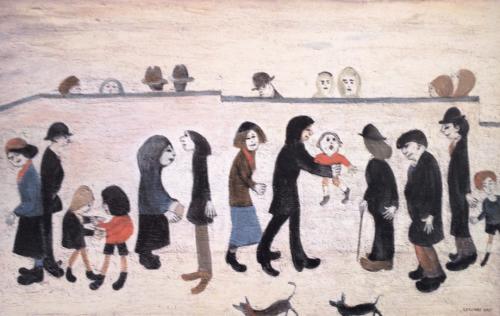

Laurence S. Lowry

b. Nov. 1, 1887

_______________________

From the Ruins

Arran James & Michael Pyska

occupied times

What comes after nihilism? This question might seem impertinent given the actual state and trajectory of things. Everywhere traditional, reactionary, and localising ideologies compete, conflict and continue colonising and recolonising the discursive terrains of our political and personal lives. This scattered and unevenly distributed field of actualisation has made it increasingly difficult to maintain semblances of coherence at all levels. How then can we claim to grasp what comes after nihilism while our cultural-subjective fields are still littered by the decaying corpses of quasi-religious, religious and secular-romantic narratives that had previously promised us much but are delivering very little? Have we even begun to evacuate the spaces of reasoning which have led our species to the brink of social disintegration and ecological collapse? How can we be beyond something not yet fully actualised?

...(more)

_______________________

La Librairie de la Lune

Brassaï

Paris, circa 1931-1943

via (OVO)

_______________________

Posthuman Economics: The Empire of Capital

S.C. Hickman

Maybe what haunts posthumanism is not technology but utopian capitalism, the dark silences long repressed, excluded, disavowed, and negated within the Empire of Capital. Franco Berardi’s The Uprising grabs the history of art and capital by the horns as the slow and methodical implementation of the Idealist program. By this he means the dereferentialization of reality – or what we term now the semioitization of reality: the total annihilation of any connection between signifier and signified, word and thing, mind and world. Instead we live in a world structured by fantasy that over time has dematerialized reality.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Fetishisms of Apocalypse

Larry Lohmann

occupied times

... isn’t the deeper problem with the appeal to apocalypse not that it is “apolitical”, but that it is all too political in a pernicious way? Not that it is “disempowering”, but that it is all too empowering of the technocratic and privileged classes?

Take climate apocalypse stories, which are currently reinforcing the old capitalist trick of splitting the world into discrete, undifferentiated monoliths called Society and Nature at precisely a time when cutting-edge work on the left – often taking its cue from indigenous peoples’, peasants’ and commoners’ movements – is moving to undermine this dualism. On the apocalyptic view, a fatally-unbalanced Nature is externalised into what Neil Smith called a “super-determinant of our social fate,” forcing a wholly separate Society to homogenise itself around elite managers and their technological and organisational fixes.

...(more)

|