|

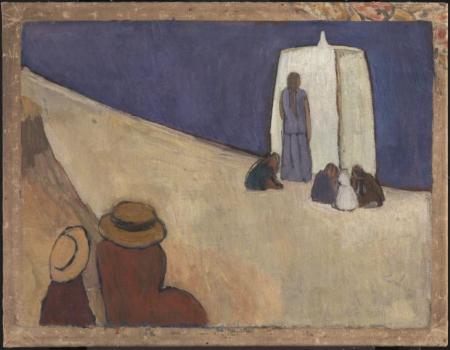

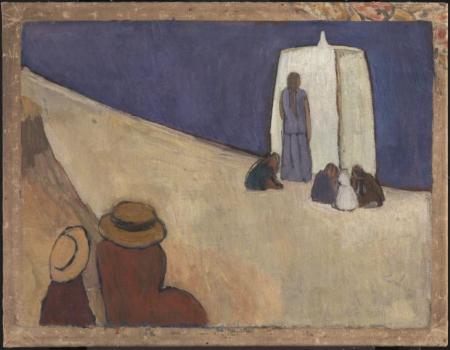

Studland Beach

c.1912

Vanessa Bell

b. May 30, 1879

_______________________

Effigy

Russell Brakefield

When the end has come, as is

fashionable to imagine these days,

and the land is covered with black

fog or retreating birds, their shadows

dwindled to bare and patchy masses,

the statues will inherit the earth.

The founding fathers will lurch

against the sky and finally take

their place as great distinctions—

white granite against a fiery lake.

In the yards of our childhood

homes, stone sparrows and frogs crafted

from a long gone mother’s hands

will suddenly see themselves, alive

in their brackish wading pools. ...

...(more)

The Collagist Issue Fifty-Eight

May 2014

_______________________

Ferryboat, early morning

1908

Harold Cazneaux

1878 - 1953

_______________________

Chopin’s Piano

Cyprian Norwid

Translation from Polish by Jerome Rothenberg & Arie Galles

La musique est une chose étrange! -- Byron

L'art? ... c'est l'art - et puis, Voilà tout. -- Béranger

1

Bound to your place those penultimate days

Whose plot was impenetrable –

– Myth-full,

Dawn-pallid …

– Life’s end a whisper summons its start:

“I will not render you – no! I will raise you! …”

2

Bound to your place, those days so penultimate

Once when you mirrored – each moment, each moment –

That lyre that Orpheus lent us,

Whose force like a missile struggles with song,

And its four strings commune with

Each, striking each other,

By twos – and by twos –

A murmur slipping toward silence:

“Did he begin

To pound out a note? …

Of what sound was he Maestro! whose playing’s repelling? …”

...(more)

_______________________

Bush fire haze

Mount Talbingo, New South Wales

Harold Cazneaux

1932

_______________________

The Specter of Authoritarianism and the Future of the Left

An Interview with Henry Giroux on Democracy in Crisis

(....)... Not only has democracy been undermined and transformed into a form of authoritarianism unique to the twenty-first century, but there is also an existential crisis that is evident in the despair, depoliticization, and crisis of subjectivity that has overtaken much of the population, particularly since 9/11 and the economic crisis of 2007. The economic crisis is not matched by a crisis of ideas and many people have surrendered to a neoliberal ideology that limits their sense of agency by defining them primarily as consumers, subjects them to a pervasive culture of fear, blames them for problems that are not of their doing, and leads them to believe that violence is the only mediating force available to them, just the pleasure quotient is colonized and leads people to assume that the Henry Girouxspectacle of violence is the only way in which they can feel any type of emotion and pleasure. How else to interpret polls that show that a majority of Americans support the death penalty, government surveillance, drone warfare, the prison-industrial complex, and zero tolerance policies that punish children. Trust, honor, intimacy, compassion, and caring for others are now viewed as liabilities, just as self-interest has become more important than the general interest and common good. Selfishness, self-interest, and an unchecked celebration of individualism have become, as Joseph E. Stiglitz has argued, “the ultimate form of selflessness.” What we are witnessing is an extensial crisis rooted in the destruction of meaningful solidarities, supportive collective provisions, and the eradication of all public spheres that open up spaces for critical and compassionate public connections. One consequence of neoliberalism is that it makes a virtue of producing a collective existential crisis, a crisis of agency and subjectivity, one that saps democracy of its vitality. There is nothing about this crisis that suggests it is unrelated to the internal working of casino capitalism. The economic crisis intensified its worse dimensions, but the source of the crisis lies in the roots of neoliberalism, particularly since its inception since the 1970s when social democracy proved unable to curb the crisis of capitalism and economics became the driving force of politics.

...(more)

_______________________

Escalinata (Staircase)

2008

Juan Genovés

b. May 31, 1930

_______________________

The forgotten roots of World War I

Kenan Malik

(....)

Without understanding the background of nineteenth-century imperialism, it is difficult to make sense either of German militarism or World War I itself. Equally, understanding this background shows why there is little sense in treating the war in black and white terms of "good" and "bad" participants, or as a war against militarism or aggression. As historian Christopher Clark put it at the end of Sleepwalkers, his outstanding study of How Europe Went to War, "The outbreak of war in 1914 is not an Agatha Christie drama at the end of which we will discover the culprit standing over a corpse in the conservatory with a smoking pistol. There is no smoking gun in this story; or, rather, there is one in the hands of every major character."

(....)

Traditionally historians have divided between those who regarded World War I as the inevitable outcome of long-term structural factors, such as imperialist rivalries, the growth of nationalism and the ossified system of alliances, and those who viewed it as the result of immediate or contingent causes, and of individual mendacity or foolishness. More recently, there has been a recognition that both long-term and contingent factors played a role in fomenting war.

But however we understand the causes of the war, the fact remains that aggressive militarism was not confined to one side. Certainly, Germany had expansionist aims and a toxically racist culture. Britain, however, was not much different. We can only rewrite the conflict as a just war against German militarism by airbrushing out the reality of nineteenth and early-twentieth century imperialism.

...(more)

_______________________

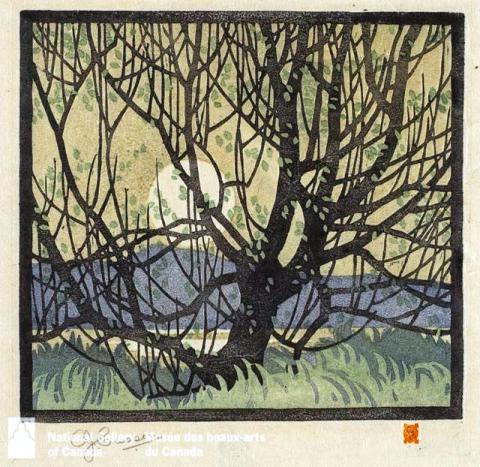

View of the Pond at Charleston

East Sussex

c.1919

Vanessa Bell

_______________________

Coffee Cantata

JS Bach

1732 - 1735

Libretto by Christian Friedrich Henrici

Recitative Narrator

Be quiet, stop chattering,

and pay attention to what's taking place:

(....)

Lieschen

Father, don't be so severe!

If I can't drink

my bowl of coffee three times daily,

then in my torment I will shrivel up

like a piece of roast goat.

Aria Lieschen

Mm! how sweet the coffee tastes,

more delicious than a thousand kisses,

mellower than muscatel wine.

Coffee, coffee I must have,

and if someone wishes to give me a treat,

ah, then pour me out some coffee!

...(more)

The Old Man and the New Trees

1883

Carl Larsson

b. May 28, 1853

_______________________

Just Walking Around

John Ashbery

(....)It gets to be kind of lonely

But at the same time off-putting,

Counterproductive, as you realize once again

That the longest way is the most efficient way,

The one that looped among islands, and

You always seemed to be traveling in a circle.

And now that the end is near

The segments of the trip swing open like an orange.

There is light in there, and mystery and food.

Come see it. Come not for me but it.

But if I am still there, grant that we may see each other.

...(more)

45-minute collaborative close reading of Ashbery's "Just Walking Around" (video)jacket2

_______________________

In Order To Breathe

An interview with the writer and philosopher Lars Iyer

Darran Anderson

The Honest Ulsterman

.

(....)

There is a politics and a philosophy of friendship in so many of the groups W. and Lars admire: the Rue Saint-Benoît group, comprising Mascolo, Duras and associates, the Operaismo movement of Tronti and others, Debord and the Situationists… In each case, it is a matter of a dream, a utopia. As Blanchot writes of one of his own communal experiments: it failed, but it did so utopianly. These utopias are necessary! So much of what I’ve tried to write is an attempt to pay tribute to these utopias, and to imagine new ones.

Friendship and the modern world: my friends are busy with their work, with their lives. It has been painful to see intellectual friends losing hope in their own projects because of long working hours, or the crushing role of bureaucracy, or – and this is widespread – a psychic malaise, a general feeling that nothing is worthwhile. How difficult it is to believe in what you can do! This is why I admire ‘outsider’ artists like Jandek. He’s been able to maintain his belief, to go on writing and releasing music, in the face of indifference and hostility. Hope, again. An ethos of affirmation. We need to be reminded of hope, if this word is allowed to name a positive disorientation, a productive lost confidence and uncertainty…

...(more)

The Honest Ulsterman

_______________________

Alexandre Calame

b. May 28, 1810

_______________________

Myth Is a Theorem About the Nature of Reality

Matthew Spellberg interviews Robert Bringhurst

The scholar of Native American literature on the vivid tradition of Haida poetry.

(....)

In those days, the 1970s, Canadian poets talked non-stop about place. Place was the sacred subject of poetry. The Haida poets, by contrast, never talked about place, but they lived and breathed it. Their work was immersed in the nonhuman world: the sea and the mountains, sea mammals and sea birds, beach rocks and beach weed and forest. What I needed to know in order to understand those poets was exactly what I wanted to know. It was what I needed to know in order to be where I was.

(....)

Haida is one of fifteen or twenty really fortunate Native North American oral literatures—one of those in which a first-class ethnolinguist got together with some first-class oral poets before it was too late to hear an older tradition in action. Something similar happened with Cree, Chipewyan, and Eyak in the North and with Hupa, Kato, and Maidu in California, with Zuni, Kawaiko, and Navajo in the Southwest, Pawnee in the Midwest, and with Kathlamet, Kwakwala, and Tlingit here on the Northwest Coast. These literatures are all very different from one another, but yes, they do have things in common. There are shared themes, a common passionate interest in fundamental relations between humans and nonhumans, and some fascinating common principles of literary structure.

Can it still happen? Sure, but it’s getting rarer. And it is surely going to get rarer still over the next little while. One of the great northern Athabaskan literary figures, Catherine Attla, a speaker of Koyukon, died in 2012. She was eighty-four. She had thousands of admirers but no apparent successor.

In the longer run, however, there are powerful forces on the side of oral literature. Industrial capitalism looks more and more like an Ozymandias nearing the end of his arrogant reign. As the high-tech systems break down, I think the low-tech systems will rebuild themselves. If our species survives, oral literature will too. It’s the written record that may go.

(....)

There’s an enormous and rich body of Native American oral literature, transcribed between the 1880s and the 1980s. Nothing of this depth or breadth could be gathered now, even if you had the world’s largest research grant and half a million well-trained, diligent researchers. What could be done now is to put that big body of transcribed literature to use. It could be edited and re-edited, published and republished, read and reread. If it were internalized by a generation of readers, North American society would be fundamentally changed. A culture based around the factory, the parking lot, and the supermarket, astoundingly disrespectful and inconsiderate of the land in which it lives, might be changed into a culture that felt a real and articulate kinship with the ground beneath its feet. The USA and Canada and Mexico could outgrow the colonial mindset at last. Where but in the universities is that work going to begin?

...(more)

guernica

_______________________

The “Close-Embrace” System

Monster Capitalism and the Complicit State

Norman Pollack

The phrase “close-embrace” to describe the incestuous relationship between business and government in advanced capitalism is by Masao Maryuma, a Japanese political scientist to describe corporate concentration under the blessing and encouragement of government. This is, along with the centrality of war and market expansion, among the most salient integral features of capitalist development in its progression to monopolism, hierarchical class structure, and establishing a full-blown partnership with government: the Corporate and National-Security States merging, with national security concerned as much with protecting the market share and freedom from adverse regulation of the dominant firms in the industrial and financial sectors, as with putatively repelling a foreign foe and protecting the “homeland”. The upshot, fascism without, necessarily, the concentration camp—fascism predicated on the internalized repression of the populace, conditioned to look to the business system as the genius of the nation, its arbiter of taste, its salvation. The trickle-down paradigm follows, as does the moral superiority of those at the top AND the enterprises they lead—conversely, justified class-stratification where the lazy and/or subversive (i.e., those maladapted to the incentives offered by capitalism) fall deservedly into an underclass.

...(more)

_______________________

"The Goat"

Buster Keaton

(1921)

youtube

_______________________

The Tantrum of Masculinity:

Rebecca Solnit on Mansplaining, Power, and Her Book ‘Men Explain Things to Me’

Flavorwire

(....)

One of the things I find really exciting about this era is that young women on college campuses, for example, are doing very powerful, meaningful organizing around campus rape and assault. In the last couple of years since Steubenville and New Delhi, the sites of the two rapes I write about in the second essay, we’ve really redefined what the problem is, and we have had the term rape culture come into circulation. Mansplaining allows us to identify something deeply problematic we didn’t really have language for. Now we’re taking away all the excuses, the “what was she wearing” kinds of ridiculousness that have justified rape. And the young women on campuses have taken away the “it’s her responsibility to prevent rape” rather than “it’s his responsibility to, well, not rape.”

We’re also getting over the widespread sense that feminism was this historical phenomenon in the ‘70s and ‘80s and we won and everything’s beautiful and we can all shut the fuck up. Or it lost and we should all still shut the fuck up. There are so many theories about it that involve us all shutting up. But one of the things that’s interesting is how change on this front moves forward in what the the geologist Clarence King would have called punctuated equilibrium, in sudden jolts after long pauses. We have these periodic adjustments where we move forward again.

I have been looking at the Anita Hill case again for something I’m trying to write. Looking at how in 1991 there was basically no understanding of sexual harassment in the workplace and why women didn’t have a lot of choices about putting up with it, and also there was no language for it. What were you supposed to do about your boss’s inappropriate comments and the demands behind them? We’re in another one of these great upheavals around, internationally, rape and violence against women. Things that would have been treated as separate phenomena people see in connection now, harrassment and belittlement as the narrow end of the wedge; at the other end are rape and murder. We used to talk about domestic violence and rape and harrassment totally separately, but it’s significant to identify what they have in common and that these are all forms in which gendered power is misused, misdistributed, and sometimes lethal.

...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

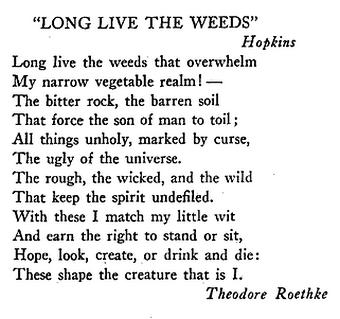

Root Cellar

Theodore Roethke

b. May 25, 1908

Nothing would sleep in that cellar, dank as a ditch,

Bulbs broke out of boxes hunting for chinks in the dark,

Shoots dangled and drooped,

Lolling obscenely from mildewed crates,

Hung down long yellow evil necks, like tropical snakes.

And what a congress of stinks!—

Roots ripe as old bait,

Pulpy stems, rank, silo-rich,

Leaf-mold, manure, lime, piled against slippery planks.

Nothing would give up life:

Even the dirt kept breathing a small breath.

_______________________

Between Weedpatch and Lamont

Kern County, California

1940

Dorothea Lange

b. May 26, 1895

_______________________

_______________________

Ben Marcus: Leaving the Sea

Review by John Self

(....)

Leaving the Sea is one of the most interesting books I’ve read this year, not just for its content but also for what it tells us about the author’s body of work and his progress as a writer. The stories are grouped, and the first four are traditional narratives – well, fairly. They have a New Yorker-ish air to them – three were published there - and to me recalled the likes of Lorrie Moore and George Saunders. They have Moore’s self-analytical protagonists, and Saunders’s passive-aggressive dialogue and men unhappy in their own skin. Paul in ‘What Have You Done?’ has “a belly that spilled around to his lower back. A second belly in the rear, which might be why he ate so much. Two mouths to feed.” Fleming in ‘I Can Say Many Nice Things’ has a similar problem. “Even in private, he had cut down on the nudity. These days the shame had followed him indoors.” In ‘The Dark Arts’, Julian, wasted with terminal illness, has the opposite problem. “You’d need more than clothing to hide a body like his. You’d need a shovel, a tarp.” Their physical failings reflect, or represent, something deeper. This is a past guilt, something sexual and unsavoury, for Paul in ‘What Have You Done?’ (the title resounds in our head as we look at Paul). He measures all women, even his mother, by their appearance. The story is set at a family reunion where Paul is trying to rehabilitate himself, but finds himself unable to talk to his family about his new life, about his wife and child. (“These people would have to die for Paul to be free. Which was bullshit, he knew. It was Paul who would have to die.”) This rings true: as children we develop and nurture the parts of our lives that cannot be seen by our families, the people who until then have known us best. (From the other side, parents first experience this when their child comes home from school and swears they can’t remember anything about their day.) Paul’s family knows him best and worst, and the story is not disrupted or spoiled by never finding out what it is that he did, just as in ‘The Dark Arts’ we don’t need to know precisely what is wrong with Julian. This coyness is a deliberate policy on Marcus’s part. In a recent interview, he spoke of how he had

written versions of all of these stories with a little more information. A little more background. And I often think, ‘OK, this answers a question,’ but in answering that question, some kind of potency is lost. When I give information, I feel like I’m killing a story. I worry about the inertia you can feel if you explain. ...(more)

_______________________

Gustave Adolphe Mossa

d. May 25, 1971

_______________________

The Minimal

Theodore Roethke

I study the lives on a leaf: the little

Sleepers, numb nudgers in cold dimensions,

Beetles in caves, newts, stone-deaf fishes,

Lice tethered to long limp subterranean weeds,

Squirmers in bogs,

And bacterial creepers

Wriggling through wounds

Like elvers in ponds,

Their wan mouths kissing the warm sutures,

Cleaning and caressing,

Creeping and healing.

_______________________

Dorothea Lange

_______________________

The Spectral Void

The Dialectics of the Void with Slavoj Žižek, Jaques Lacan, and G.W.F. Hegel

a new blog by Craig Hickman (Noir Realism)

... His fondness of Lacan and Hegel is both his glory and his horizon. One can fault him with logical errors and strange twisting’s of theory and practice, but one cannot doubt that there is under the wordy dialectical constructions an actual message. A lot of people disagree with him, but one ignores him at one’s own peril. For if we have one indispensable philosopher in our age it is Slavoj Žižek.

_______________________

"The Magnanimous Cuckold"

stage design

Liubov Popova

d. May 25, 1924

_______________________

Autumn Journal and the form of poetic conscience

Aaron Smith on MacNeice's Autumn Journal

If there were a league table for the re-reading of poems in the Heaney centre, Autumn Journal, in spite of its length, would rank consistently in the top third. Such is MacNeice’s influence in Ulster: the place where, according to Derek Mahon (author of ‘In Carrowdore Churchyard’) MacNeice’s reputation ‘finally come[s] to rest’, that those of us who have come to recognise his ‘familiar voice whispering in [our] ear’ would find the harshness of its first reviews vaguely insulting: the critic Julian Symons – not Mr Continuity, UTV (different spelling) – labelled the poem ‘The Bourgeois’ Progress’, while Virginia Woolf dismissed it as ‘weak’, taking the opportunity in her essay The Leaning Tower to highlight the failures of thirties’ poetry generally:

These then, briefly and from a certain angle, are some of the tendencies of the modern writer who is seated upon a leaning tower. No other generation has been exposed to them. It may be that none has had such an appallingly difficult task. Who can wonder if they have been incapable of giving us great poems, great plays, great novels? They had nothing settled to look at; nothing peaceful to remember; nothing certain to come.

In portraying the negative aspects of uncertainty, Woolf disregards, or fails to notice, any of its complementary features; her opinion reveals the radical bias of High Modernism against tradition, regarding the thirties’ poets as reactionary, Woolf and other High Modernists were blind to how traditional form could provide the means for navigating uncertainty. Thirties’ poets accepted the ruins of The Waste Land as their backdrop, yet found in form the common ground necessary for communication beyond its rubble, along with the potential for a system justly responsive to inner and outer pressures. His background in an infamously recalcitrant culture convinced MacNeice of the need for fluidity in spite of what Mahon calls ‘the rigor mortis of archaic postures’, the paradox of unstoppable force and immovable object equivalent to Christianity’s giving up of one’s life to save it; of ‘traditionalism’ as the death of a ‘living tradition’ subject to change:

Virtue going out of us always; the eyes grow weary

With vision but it is vision builds the eye;

And in a sense the children kill their parents

But do the parents die?

...(more)

The Lifeboat_______________________

The Dance

Theodore Roethke

Is that dance slowing in the mind of man

That made him think the universe could hum?

The great wheel turns its axle when it can;

I need a place to sing, and dancing-room,

And I have made a promise to my ears

I'll sing and whistle romping with the bears.

For the are all my friends: I saw one slide

Down a steep hillside on a cake of ice, —

Or was that in a book? I think with pride:

A caged bear rarely does the same thing twice

In the same way: O watch his body sway! mdash;

This animal remembering to be gay.

I tried to fling my shadow at the moon,

The while my blood leaped with a wordless song.

Though dancing needs a master, I had none

To teach my toes to listen to my tongue.

But what I learned there, dancing all alone,

Was not the joyless motion of a stone.

I take this cadence from a man named Yeats;

I take it, and I give it back again:

For other tunes and other wanton beats

Have tossed my heart and fiddled through my brain.

Yes, I was dancing-mad, and how

That came to be the bears and Yeats would know.

René Daniëls

b. May 23, 1950

_______________________

In the Middle of Life

Tadeusz Rózewicz

(9 October 1921 – 24 April 2014)

translated by Czeslaw Milosz

After the end of the world

after my death

I found myself in the middle of life

I created myself

constructed life

people animals landscapes

(....)

this water I was saying

I was stroking the waves with my hand

and conversing with the river

water I said

good water

this is I

the man talked to the water

talked to the moon

to the flowers to the rain

he talked to the earth

to the birds

to the sky

the sky was silent

the earth was silent

if he heard a voice

which flowed

from the earth from the water from the sky

it was the voice of another man

...(more)

Tadeusz Rózewicz - Poems

Tadeusz Rózewicz: poet of a decimated generation

George Szirtes

_______________________

Orange Outline

1955

Franz Kline

b. May 23, 1910

_______________________

Wobbly Rock

Lew Welch

d. May 23(?), 1971

for Gary Snyder

“I think I’ll be the Buddha of this place”

and sat himself

down

1.

It’s a real rock

(believe this first)

Resting on actual sand at the surf’s edge:

Muir Beach, California

(like everything else I have

somebody showed it to me and I found it by myself)

Hard common stone

Size of the largest haystack

It moves when hit by waves

Actually shudders

(even a good gust of wind will do it

if you sit real still and keep your mouth shut)

Notched to certain center it

Yields and then comes back to it:

Wobbly tons

...(more)

_______________________

René Daniëls

_______________________

Out Looking For Lew: [pdf]

Bioregional Poetics & The Legacy Of Lew Welch

Jerry Martien

big bridge

“The question is no longer: where are you, Lew?

The question is: where are we?”

—S. Fox

A poet goes to the mountain—the desert, the underworld, a river in the west—and returns to us with the news: Here’s where it’s at. Here’s where we are. The poet brings us to that ground, lets its voice resound in our hearts, and then—if the poem is successful—disappears. Almost like being a bird.

It was Lew Welch’s extraordinary gift to sing this poem of place for us, so we might more deeply inhabit the territory in which we find ourselves.

And it is his difficult legacy that he then really disappeared.

(....)

One winter night during my failed hermit experiment I got another of its unexpected lessons, more helpful than what I usually brought home from the bar. A San Francisco troupe was performing animal/human plays, comic pieces drawn from Native California stories and 1970’s rural life, something they called reinhabitory theater. I had met most of the company, knew they’d been part of the Mime Troupe and then the Diggers, the revelatory communitarians whose circle sometimes included Lew Welch. One of the night’s players, Peter Coyote, has described Welch’s visits to the Digger commune in Marin, where a vital (and voluptuous) connection was made between the elder Beat poets and a new generation of cultural visionaries. In the evening’s blend of ecology and theater I was witnessing some of Lew Welch’s legacy to the bioregional movement.

But another member of the cast, his former partner Lenore Kandel, had a more immediate lesson. I was an admirer of her poetry and awed by her toughness and spirit—a motorcycle crash had made theater painfully difficult—but I hadn’t anticipated her gift for comedy. She played an uproariously funny chicken in a skit about hippy homesteaders. After the show I was standing at the bar, probably raving about my recent discovery of Lew Welch’s life and writing, and as she walked behind me she yanked on my long braid. The gesture was playful, but it snapped my head back. When she had my full attention, she said: Don’t romanticize him.

Then she laughed, full and generous, but I knew her injunction was drawn from hard experience and deep regard. I hear Lenore’s laughter when I ask myself what I’m doing here.

When the sun finally comes over the eastern ridge I’m sitting on the lizard rock sipping coffee and regarding the river. Below a bend of white water, above the spot where I almost crossed, there’s a deep pool and a sand bar where I’ll spend the morning. I’m not going to look for Rat Flat. The best way to acknowledge Lew Welch’s time here is to stay where I am—today, tomorrow, the day after—to put away the books and maps and get back in touch with whatever told me thirty years ago, against all probability, to write about the beautiful damaged place I live. Maybe I’ll get out the poems I dragged along, which a few days ago seemed hopeless.

(....)

_______________________

Number 2

Franz Kline

1954

_______________________

The Basic Con

Lew Welch

Those who can't find anything to live for,

always invent something to die for.

Then they want the rest of us to

die for it, too.

These, and an elite army of thousands,

who do nobody any good at all, but do

great harm to some,

have always collected vast sums from all.

Finally, all this machinery

tries to kill us,

because we won't die for it, too.

_______________________

New Dutch Herring

René Daniëls

1982

_______________________

The Secret History of Life-Hacking

How the cult of self-optimization was born on the factory floor-with a manager's stopwatch in hand.

Nikil Saval

Pacific Standard: The Science of Society

via I cite

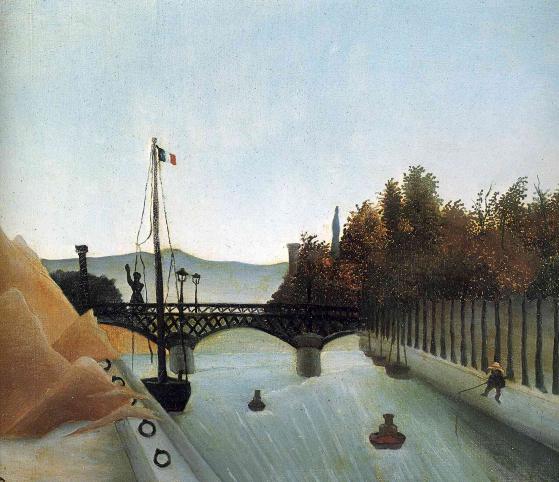

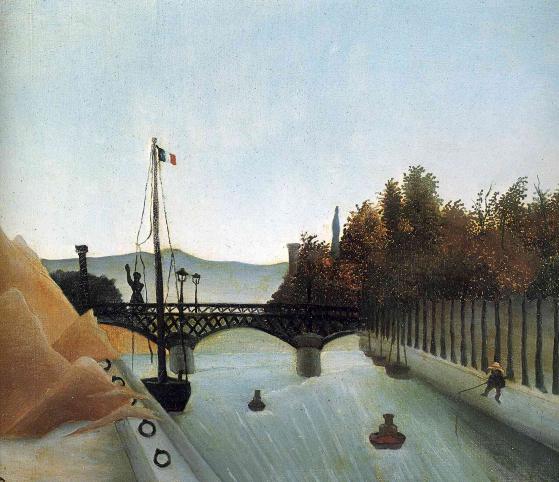

Footbridge at Passy

Henri Rousseau

1895

_______________________

Two Poems by Ingeborg Bachmann

Translated by Peter Filkins

berfrois

The Bridges

(....)

Lonely are all bridges,

and fame is as dangerous for them

as it is for us, yet we presume

to feel the tread of stars

upon our shoulders.

Still, over the slope of transience

no dream arches us.

It’s better to follow the riverbanks,

crossing from one to another,

and all day keep an eye out

for the official to cut the ribbon.

For when he does, he’ll seize the sun’s scissors

within the fog, and if the sun blinds him,

he’ll be swallowed by fog when he falls.

...(more)

via Forgottenness

.....................................................

Reading Ingeborg Bachmann

John Taylor

Context N°13

(....)

... This principal, most significant activity of the narrator’s life cannot be observed; the novel can only attempt to help us see what cannot be seen. In her acceptance speech for the Anton-Wildgans-Preis, received in 1972, Bachmann pointedly commented: “I exist only when I am writing. I am nothing when I am not writing. I am fully a stranger to myself, when I am not writing. Yet when I am writing, you cannot see me. No one can see me. You can watch a director directing, a singer singing, an actor acting, but no one can see what writing is.” In this sense, the narrator and perhaps also Malina are “nothing,” “no one,” in the novel. At best, they are apparitions or strangers. They exist authentically only in what is unstated, in what cannot be told. Bachmann leaves us with the redoubtable task of grasping their essence “behind the novel,” as vital sources that can be intuited yet not named.

Heading toward language thereby implies pushing words to their limits, nearing them to the ineffable; analogously, of driving the self to its frontiers and perhaps beyond. And in this regard, the ominous pronouncements (“the boundaries of my language mean the boundaries of my world”; “of that which one cannot speak, one must remain silent”) of another salient Viennese personality likewise underlie the very conception and narrative processes of Malina. In her essay on Wittgenstein, Bachmann notably praises the philosopher’s “despairing pains with the inexpressible (das Unaussprechliche), [pains] which charge the Tractatus with tension.” This same tantalizing tension characterizes Malina from beginning to end.

...(more)

_______________________

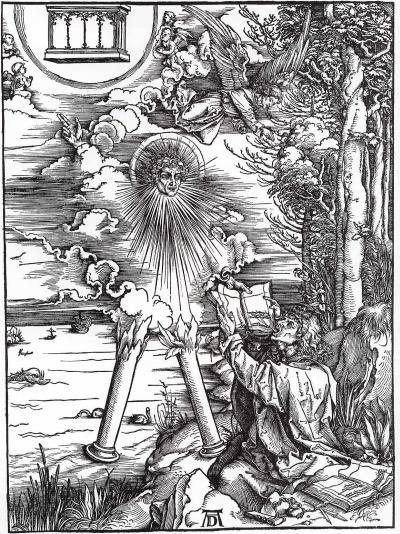

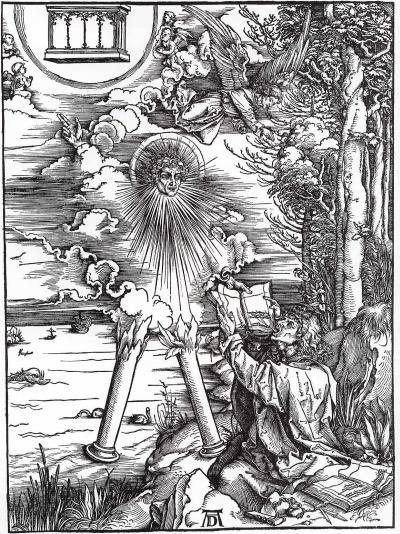

St. John Devouring the Book from the 'Apocalypse'

Albrecht Dürer

b. May 21, 1471

_______________________

Completely Without Dignity: An Interview with Karl Ove Knausgaard

paris review

Life develops, changes, is in motion. The forms of literature are not. So if you want the writing to be as close to life as possible—I do not mean this in any way as an apology for realism—but if you want to write close to life, you have to break the forms you’ve used, which means that you constantly have the feeling of writing the first novel, for the first time, which means that you do not know how to write. All good writers have that in common, they do not know how to write.

_______________________

Oral Authority: If Twitter is Dying, What Comes Next?

Navneet Alang

hazlitt

Social media is like a cultural oscilloscope. Use something like Twitter, and it’s like reading in real-time the pulse of a crowd as it ebbs, flows, and surges. It is, in many ways, akin to scholar Walter Ong’s description of oral cultures: immediate, more communal, and prone to what Ong calls “agonism”—a kind of deliberate contentiousness to stand out in memory.

Twitter, composed as it is of typed words, isn’t actually oral, of course. But thinking of the service as oral-like helps explain a great deal about it—not least of which is why it is, at the same time, both “dying” and more vibrant than ever.

(....)An exodus from Twitter would be terrible: a space where we are all forced to confront the vastness and complexity of life around the world is a remarkable challenge to the controlled narratives of “old media.” All the same, as Twitter’s limits for certain kinds of discourse begin to show, maybe something new to run alongside Twitter would be a way to round out social media—slow it down, make it a bit quieter, so that, at least in small doses, the readings we get from the oscilloscope aren’t quite so overwhelming.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Weed

photo essay

Paula's House of Toast

(....)

Photography, usually, is about the thing-in-itself. Not the category weed, even the sub category dandelion, but this particular creature at this moment of its life, in this particular bit of sun or shadow, viewed by a particular set of eyes behind which seethe masses of contingent preference and point-of-view, all of which is moving through transience and toward demise, or, if you will, transformation.

I am the Dorothea Lange of meadow and swamp. I have borrowed the biblical judge not and applied it to the field-of-no-lilies.

(....)

Oh, to be sure, the weeds talk, too, but you have to know how to listen, and what you hear you may not like. For who likes to hear semblable, soeur from a non-celebrity mouth ? Who likes to be told they are nothing special, hardly the Universe's eye-apple, hardly the beloved child of something that might be called "God." But listen. Stay with it, breathe, wait, wait, wait, until suddenly everything explodes into a shimmering aurora of sublime and overwhelming indifference, so ghastly and beautiful that the very weeds bow down in the field. And you beside them.

...(more)

_______________________

The M Word

Sina Queyras

lemon hound

What We Won’t Talk About When We Talk About Mothering

When I first saw a Tweet announcing the impending publication of The M Word I Tweeted in response that if the book makes me laugh more than sigh, I would love it. The Tweet was half provocation, half earnest, but as I waded into the text I realized the Tweet was more serious than I thought. As a professor, writer, editor, and mother of two-and-a-half-year-old twins, I’m probably the target market for such a book, or at least, “a target.” And in truth it’s a good bet: I am hungry for such publications. I am hungry to hear how other people—though perhaps not only other women—are coping with parenting.

Still, I approached this text with trepidation. I have quickly learned to be wary of discussions about parenting, and of discussions with mothers. This is loaded terrain. It’s incredibly easy to offend or piss someone off, including myself apparently. The cover itself, with the M setting itself off in a sea of white (a comment on the list of contributors?) with a small round baby head set to mute sends a strong message about the kind of reader interested and I don’t feel it at all represents me. And right away one has to ask, does the style of motherhood really matter that much? What do I want from such a book that the way in which the information is offered can so easily offend? What am I expecting? And how am I expecting it?

...(more)

_______________________

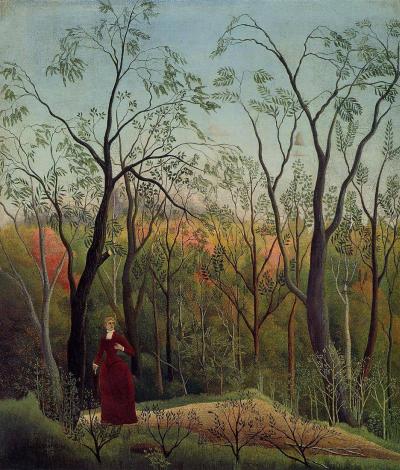

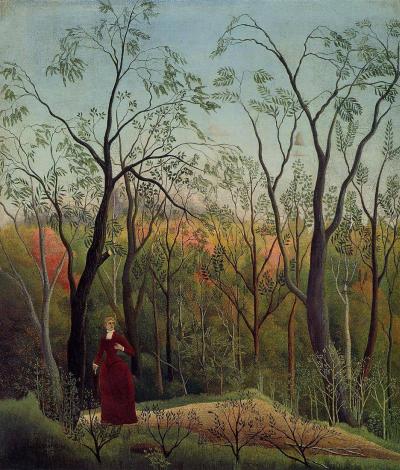

Promenade in the Forest

c. 1886

Henri Rousseau

b. May 21, 1844

_______________________

Aura, Artifact and Apparatus: Towards a Theory of Tourist Photography

Dennis Schep

depth of field

Abstract

While both tourism research and photography research have grown into substantial academic disciplines, little has been written about their point of intersection: tourist photography. In this paper, I argue that a number of philosophically oriented theories of photography may offer useful perspectives on tourist photography. In my readings of Benjamin, Flusser and Barthes, I highlight those aspects of their theoretical work that offer insight into tourist photographic behavior, while pointing out where their theories need to be revised before they can be extrapolated to this domain. In particular, drawing on Barthes, I highlight the photograph's function as a material testimony constituting an implicit autobiographical narrative; drawing on Flusser, I foreground the camera's productive capacities, opposing these to a widespread perception of the camera as a passive recording device; and, drawing on Benjamin, I analyze the photograph's capacity to endow sites with an elusive aura that cannot be reproduced in any actual pictures of the site. While these authors have provided the theoretical framework for my analysis of tourist photographic practices, all of them need to be assessed critically, as their theories require significant alterations before they allow us to grasp the specificity of the tourist situation.

marsh marigolds in a mill stream

photo - mw

_______________________

Mushrooms

Charles Tomlinson

for Jon and Jill

Eyeing the grass for mushrooms, you will find

A stone or stain, a dandelion puff

Deceive your eyes—their colour is enough

To plump the image out to mushroom size

And lead you through illusion to a rind

That's true—flint, fleck or feather. With no haste

Scent-out the earthy musk, the firm moist white,

And, played-with rather than deluded, waste

None of the sleights of seeing: taste the sight

You gaze unsure of—a resemblance, too,

Is real and all its likes and links stay true

To the weft of seeing. You, to begin with,

May be taken in, taken beyond, that is,

This place of chiaroscuro that seemed clear,

For realer than a myth of clarities

Are the meanings that you read and are not there:

Soon, in the twilight coolness, you will come

To the circle that you seek and, one by one,

Stooping into their fragrance, break and gather,

Your way a winding where the rest lead on

Like stepping stones across a grass of water.

Charles Tomlinson, The Art of Poetry No. 78

Interviewed by Willard Spiegelman paris review

Addressing one's peers

The letters of Charles Tomlinson and George Oppen, 1963–1981

jacket2

Charles Tomlinson at PennSound

_______________________

Stillness After Rain

A. J. Casson

(May 17, 1898 – February 20, 1992)

_______________________

Heimrad Bäcker: Documentary poetry (an essay)

Afterword by Sabine Zelger: A past charged with now-time

Translated by Jacquelyn Deal and Patrick Greaney

jacket2

(....)

Language from history’s cellars, the language of “top secret matters of the Reich,” is laden with relics from the historical canon of good conduct, with concepts of versatile goodness. My brother’s keeper becomes Heinrich Himmler, a man who “remains decent” as he has murder carried out on a grand scale. Language conventions, which even the lower ranks were made to follow, allow murder to become a “glorious chapter in German history.” The idealist style, inherited from the idealist-humanistic arsenal, coerces into speech acts of substitution. Concepts remain intact as their reach is increased ad infinitum, while what can only be described using terms like unbelievable and unimaginable takes place in the caverns of the Third Reich.

The type of text known as a “document” becomes literature when a correspondence emerges among chosen parts of a text. In his essay on collage, Franz Mon refers to a peculiar relation that is also at work here: that which appeared to be the furthest apart is actually what most belongs together, or, as Max Ernst puts it, “the juxtaposition of two (or more) seemingly distant realities” ignites “the most powerful poetic spark.” Applied to our example: my book transcript brings together in its “system of relations” (Friedrich Achleitner) these realities that are essentially foreign to one another: the statistics in an insurance yearbook—with their fixed formulas of unadjusted values, the numbers of observed dead, the numbers of statistically dead, the adjusted and unadjusted mortality probabilities—and that which cannot be estimated for any average experience, murder on a scale beyond every mortality probability. Concepts can no longer conceive of this, or if they can, then only within this textual system of absurd “poetic sparks.”

transcript and the radio play Gehen wir wirklich in den Tod? (Are we really going to our deaths?) could be called collage agglomerates. Unlike other collage forms, these texts quote continuously, without interruption. The method is not new (except for the fact that it takes on an extreme form). Berlin Alexanderplatz and Danton’s Death come to mind: one fifth of Büchner’s work consists of passages from court files or history books about the French Revolution. The historical-critical edition compares the source and Büchner’s text; they are almost identical; the straightforwardness of the diction is due to the quotations—a closer proximity is unimaginable.

What took place cannot be captured with the literary forms developed on this side of the terror. And yet a method must be found (one doesn’t have a choice) that is adequate to its negative monumentality.

...(more)

_______________________

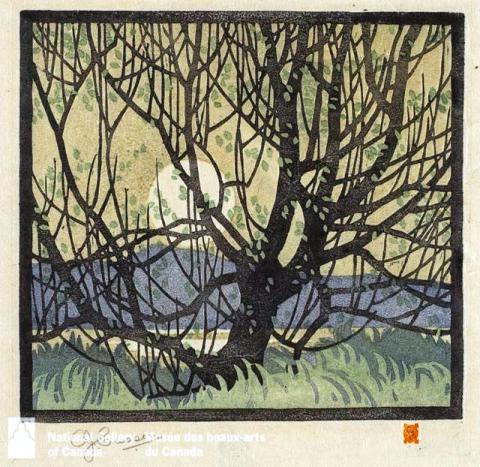

The Old Willow

A. J. Casson

c. 1919-1920

_______________________

Renee Gladman and the New Narrative

Virginia Konchan

jacket2

(....)

The most well-known interpolation of a reader in nineteenth-century literature is “Reader, I married him,” from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Roland Barthes’s The Lover’s Discourse (1978) and The Pleasure of the Text (1973), Toril Moi’s Sexual/Textual Politics (1988), and other essays by Julia Kristeva, Hélène Cixous, and Luce Irigaray constitute a few cornerstones in the textual hermeneutics, instantiated by Roland Barthes, of both écriture (writing about writing) and écriture feminine (the inscription of the female body and female difference in language and text), as well as theories of the lyric, narrative, personhood, and body politics. Choosing between the assembly and gleeful dismemberment of a purely citational, web-derived textual “body” (Flarf) or a version of Homeric mimesis (e.g., Kenneth Goldsmith’s Day, wherein he transcribes mass media’s ideology rather than poetic tradition) takes the questions of agency, intentionality, and framing (for writer or reader) and turns them into questions of proprietorship (intellectual property and copyright or droit moral): a swift divagation from the epistemological and ontological questions that haunted the modernists, from Sartre’s “What Is Literature?” to the question of whether a “poem” is defined or judged by its constitutive elements (its material body as expressed in syntax and line, meter and rhythm), its function (how it “works”), or its telos (was it “intended,” and if so, for whom). Writing to one’s audience is a doubled-edged sword. While pandering to the masses can be a means of survival at the cost of authenticity, limiting one’s projected readership to those schooled in academic jargon or in the parlance of an elitist (pop or hipster) coterie can also be forms of false consciousness.

New Narrative writers mark the gulf between readerly intimacy and direct interpolation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and today’s habitus of authorial onanism as a symptom of capitalist alienation, and also as its source. One New Narrative writer is Renee Gladman, a professor at Brown University (school of experimental aesthetics). The author of A Picture-Feeling (2005) and several works of fiction, including Event Factory (2010), The Activist (2003), Juice (2000), and Arlem (1994), Gladman tests the potential of the sentence with the cartographic precision and curiosity endemic to the New Narrativists, whose work is framed in spatial rather than stylistic terms. Gladman’s work, and the work of other New Narrativists (Kathy Acker, Camille Roy, Michelle Tea, Eileen Myles, Laurie Weeks), borrows more from new performance theories than from narrative theories (Walter Benjamin, Louis Althusser), most of which insist on separating art from aesthetics, or operating within a performative frame rather than conflating form with content. A productive, Brechtian sense of the alienation effect is different from the totalized spectacle: the formal and real subsumption of aesthetics under capitalism and performance, anesthetizing emotion and the participatory real. In the words of Walter Benjamin: “We will arrive at a moment of sufficient self-alienation where we can contemplate our own destruction [as a species] as in a static spectacle.”

...(more)

_______________________

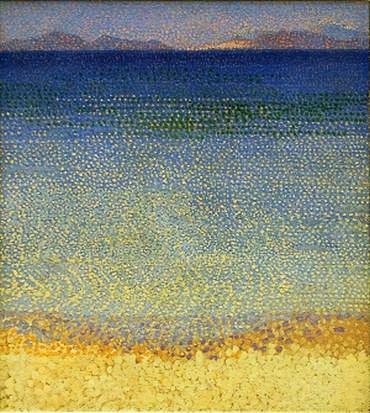

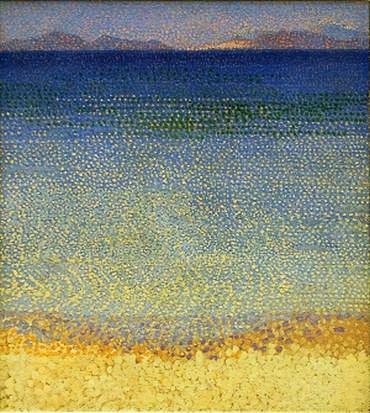

The Iles d'Or

1892

Henri-Edmond Cross

d. May 16, 1910

_______________________

If it Weren’t for the Mouth of the St. Lawrence

Antony Di Nardo

lemon hound

I’ve got a message for you, he said,

But saying it would take all the time in the world

So instead I wrote it on the face of the river,

A place Banksy hasn’t yet found.

I’ve got a message for you, but it’s deep in the bottle

I’ve set out to sea and certainly it’s deep

Down in the bowels of the sea by now

And it’s made of nothing but air I’ve set free

From this room, this mouth, this episode

I have on my mind, gaps between words.

And Purdy says Layton and Layton says Wallace,

What a world to witness with words say the records.

...(more)

Lynn Geesaman

1 2 3 4

.

via Arsvitaest

_______________________

Pain and Parentheses

Christopher Benfey

new york review of books

I began thinking about pain and parentheses when I was reading (I’m tempted to say rereading, but it always feels like the first time) Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, and came across the following question: “What does this act of meaning (the pain, or the piano-tuning) consist in?” The passage refers back to an earlier one: “Imagine that you were in pain and were simultaneously hearing a nearby piano being tuned. You say ‘It’ll soon stop.’ It certainly makes quite a difference whether you mean the pain or the piano-tuning!”

What tugged at my attention wasn’t the argument itself, to the extent that I could follow it, but rather the arresting parenthesis “(the pain, or the piano-tuning),” which immediately reminded me of another example of bracketed pain—“the most famous parenthesis in postwar literature,” according to Geoff Dyer—namely, Humbert Humbert’s laconic précis, in Lolita, of the death of his mother:

My very photogenic mother died in a freak accident (picnic, lightning) when I was three, and, save for a pocket of warmth in the darkest past, nothing of her subsists within the hollows and dells of memory.

I found myself wondering how many other parentheses like this there were: windows in a wall of verse or prose that suddenly opened on an expanse of personal pain. Masquerading as mere asides, they might hold more punch than parentheses are usually expected to hold, more even than the surrounding sentences, and have all the more impact for their disguise as throwaways. Were such parentheses common, I wondered, and if so, why?

...(more)

_______________________

An Interview with Raymond de Borja

transit

(....)

Paraphrasing Badiou rather simplistically, but which I hope suffices given the limited discussion space of our dialogue, the new is something that the existing language cannot yet name. With the risk of sounding tautological, the new in poetry, is exterior to the ‘situation’ of poetry. So this brings me to invention – in so much of what is offered as ‘new writing,’ invention and innovation seem to figure high-up the value ladder. I would like to re-think the potency of invention and innovation as values, specifically as values set in the arts. Invention, in current use, pertains specifically to the creation/production of something useful, with usefulness mostly equated, in the context of market economy, to measurable in terms of monetary value. Innovation means to introduce something as or as if something is new, which in the end can simply mean to market, or to re-package. I do not mean to say that we should think of art outside the socio-economic factors that go with its production but I am also beginning to doubt the efficacy of such framework for critique. Badiou says, and I paraphrase, of the analytic and the postmodern, that they reflect the physiognomy of the world too far, that they are too compatible with the world to sustain the rupture that thought requires.

But I realize now, that with this much reference to philosophy, I may have inadvertently expressed that the role of the arts is subservient to philosophy, that philosophy is where the truth, the new are produced – this is especially not the case in Badiou, where the role of philosophy is to think the compossibility/consistency of truth in the four domains where truths are produced – science, love, politics and art.

Going back to invention, archaically, invention also means ‘to find, to discover,’ and innovation means ‘to effect a change’. I think in lyric poetry we need to salvage invention and innovation from its current use, and make it again a ‘discovery’ while being altogether informed of the limitation of the epiphanic lyric, where discovery is calculated, and presented ‘as if’ new. What I think we should aspire for is a finding, a discovery of forms for the in-form the in-form being that which is outside form, outside the situation of poetry, ‘the void’ of poetry (?)).

(....)

I remember sitting-in on one of Marc Gaba’s class where he says that “the poem is a level of attention.” That made quite an impression on me, and I remember hanging on to that thought even though the class was on to another idea. I had attention in mind as I worked through they day daze and “Selected Days.” Attention – duration – perception – these are interests I hold in my recent projects. On a grander scale, I am thinking of Simone Weil’s “attention” and also of the value of attentiveness when so much happens so fast. I think of these not out of a nostalgia for slowness, but out of sincerity. I think we need a ‘slowness’ to be able to work sincerely. I’m working on a series of essays on sincerity to try to think about this idea more. My interest in sincerity is prompted by the wonderful sentence “I am writing the truth,” but also as it relates to a kind of attentiveness, this one prompted by my dissatisfaction with a poetics of irony, how irony has figured in as a kind of automatic critique. While I think irony is useful as an immediate practical response, I doubt its efficacy as an ongoing trope and critique, and so I think about the possibility of sincerity but outside the romantic and simplistic notions of I, am, writing and truth. So there, initially talking about attention, I find my way digressing (!) to sincerity.

Visual and textual collages are part of my process. In they day daze, collage figures in as a try to think about perceiving, along with reading text. In “Selected Days,” I think about music, the musical line, and the possible sutures between image and sound. There’s this beautiful line by Keith Waldrop, whose poems and collages I deeply admire, that goes “I have tried to keep/ context from claiming you” – a line which distills so much of the hopes and defeats one goes through when thinking about persons in time, looking.

...(more)

via The Page

Raymond de Borja on Sincerity

lemon hound

_______________________

Versailles, France

Lynn Geesaman

_______________________

Ante Matter

Brian Laidlaw

Drunken Boat 18

Pretty good work if you can get it, making paradises in abandoned banks

Stony exterior, marble interior,

The registers like a failed carillon (toneless) striking all hours at all hours.

Every noon the ghost attendants ghost-walk up to the kiosk,

Throw down nobody’s money

(The two days you are proud of a boat are the day you buy it and the day you sell it)

Trading in the heart for the farm, buying the farm,

Selling the bucket to kick

The can, selling the farm when you kick the bucket.

It doesn’t make sense to dream of a time after the apocalypse because

That’s a time of permanent wakefulness anyway: high-level emissions,

Grainy disturbances. Until then

Remember the language of contracts: you can bank on love

& When that bank collapses, your worries are the least of your worries.

more poems by Brian Laidlaw1 2 3 4

Introduction to Debt Folio

Michelle Chan Brown

Drunken Boat 18

(....)

When Drunken Boat placed the call for poems that examine “the friction between desire and limits, the intersection of ownership and obligation,” I could not anticipate that I would, months after the call, commute through a ghost-town Pennsylvania Avenue, and be self-consciously typing “John Boehner understanding the default” into my browser. As this particular narrative transitions from pathos to bathos and back, however, the process of reading the extraordinary submissions for this folio have clarified one of my suspicions about debt, at least with regard to poetry. Writing and reading are joyous enactments of debt: reader and writer are, like new lovers, perpetually locked into a cycle of captivity and yearning, and it is the very refusal of settlement that reinforces process as pleasure. Reader needs writer needs…the owing, and the refusal of ownership, will not cease. Nor should it.

Rather than present a catalogue of teaser lines from the exceptional poets in this folio, I invite you to enter the process of mutual submission from some of the most exciting voices in poetry: Cynthia Cruz, Sandra Lim, Wesley Rothman, Matthew Lippman, Anna Marie Hong and Kara Candito, to name just a few. The range of subject and formal approach is testament to how profoundly debt threads through our sense of our selves in the world, even before the Federal farrago. I feel privileged to have been reader of these poems, and of the many excellent submissions that could not be included. And, ultimately, I can’t resist ending with Sandra Lim, from “Vous Et Nul Autre”:

Before he goes and she helps

herself with plans, prior to the seamed

self saying, let them, let them wreck in me—

They are so sorry for each other’s anger.

Nevertheless, they rummage inside

themselves for their tiny knives of feeling

/

and all they want now is relief,

not from feeling but from the anticipation

of an answer, for all the formal difference in between.

...(more)

_______________________

Lynn Geesaman

_______________________

“Statement 1968” from A Voice Full of Cities

Robert Kelly

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

[The following will appear later this year in A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly (Contra Mundum Press), edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh. Originally published by John Martin's Black Sparrow Press in 1968.]

(....)

primitive, natives of our own hungers, needs. (& Levertov, putting some or all of us down, or was it only me, said This is a poetry of desire, not of need. A very subtle thing to say, but the distinction was hers, not there in the world, where hunger is unquenchable & Eros & Vision, & need a philanthropist’s cold way of seeing the statistics of it. Wd she speak ill of Eros? Yet she found something, calling it wrongly, that was wrong there, in the air of that time of work, a voulu insistence on the distant & the Strange, often to the loss of kitchen & subway & bed, the works of dailiness in a city

but they were men in a trap, who mistook the sunlight itself for their cage, & the ripeness of flesh around them for archontic evil & (so persuaded) thus needed a magic out of the trap, a language, an alchemy of the Tour St. Jacques or obsidian self-torture of the Aztec priest, so they, or we, were not pastoral

detected no order,

made

order when we could,

a syntax of objects, an Ernst, a

Spoerri table

but talked too much. O how we talked too

much, primitive & deep image & duende, blithering

slogans & all the gimcrack foolishness of the articulate

young.

(Sd Rothenberg to me: we’ll be sorry if we

give ’em a slogan! & so we were)

but there was a

splendor, light reflected back upon us from those

words we used, tried to stand under & be worthy of,

&

the words were worth, held us to what we’d promised, bound us to our premises, measured us, indicted us (Rothenberg & me, who’d done most of the talking, at least what got to print; Economou reluctant and thoughtful reserved, Rochelle Owens laughing at the clumsy words we’d prosed around what we & she cd so much better sing, Wakoski slyly at the sidelines, poking fun, Mac Low scoffing openly, alert.)

& now may be seen those words float back in the casual dissertations of gents who have not troubled to read further than the slogans

(Lorca, forgive us your duende. Nightmare of our nights, forgive us the word we thought to hold you at bay with)

...(more)

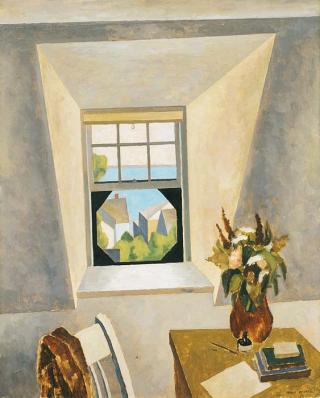

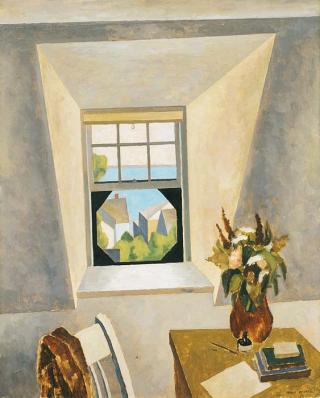

The Dormer Window

1927

Niles Spencer

b. May 16, 1893:

_______________________

In This World Previous to Ours

Marcella Durand

conjunctions

(....)

Land fades from us. Transitions are into water

and with water, wave. Wave, change and indication.

Clouds gather in a sort of communication.

Today was at first sunny. Now? Now, birds touch edge

of weather and turn again, away from us, as

fast as they can fly. As fast as we can catch up

with them, in our flying machine with wings that fall

to rocket position, so aerodynamic.

...(more)

Marcella Durand at PennSoundpoems 1 2 3

_______________________

Bouquet

Jean Fautrier

1928

_______________________

What is more natural: thinking space and poetry

Sina Queyras interviews Marcella Durand

(....)

SQ: Do you think that poetry can be part of a reactive matrix dealing with our perceptions and relationship to environmental social and cultural issues around climate change?

MD: Absolutely yes. I like your term matrix, and I’d also argue that poetry can be an active matrix, especially when it resets, so to speak, words’ relations to systems and objects. Where poetry reworks how things are articulated, in that space where the exterior occurs, we perceive it, and then articulate it. I’m very interested in Ponge, Thoreau, Mayer, in how they got close to both thing and mind and even closer in language. So while writing poetry concerned with ecology may not have immediate, measurable, political effect, it is the unseen space, maybe often a private space, where language is questioned, where an incredible stream of data is translated into new ways of phrasing, seeing, investigating.

...(more)

_______________________

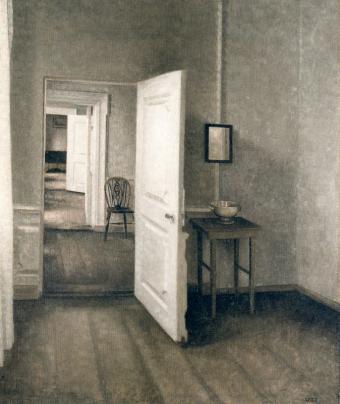

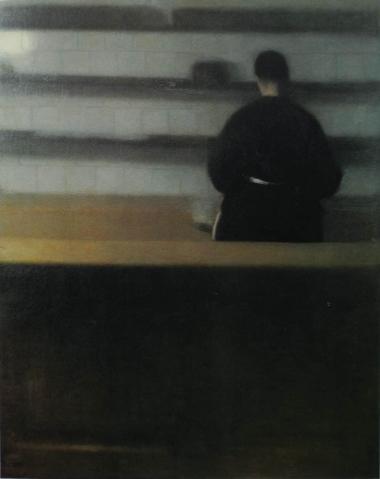

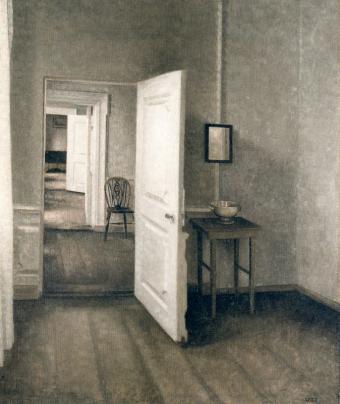

Vilhelm Hammershøi

_______________________

Wait

Adrienne Rich

Born: May 16, 1929

In paradise every

the desert wind is rising

third thought

in hell there are no thoughts

is of earth

sand screams against your government

issued tent hell's noise

in your nostrils crawl

into your ear-shell

wrap yourself in no-thought

wait no place for the little lyric

wedding-ring glint the reason why

on earth

they never told you

No place for little lyric (PoemTalk #2)

Adrienne Rich, 'Wait'

_______________________

Otage

1943

Jean Fautrier

b. May 16, 1898

_______________________

While consciousness brought us out of our coma in the antural, we still like to think that, however aloof we are from other living things, we are not in essence wholly alienated from them. We do try and fit in with the rest of creation, living and breeding like any other animal or vegetable. It is no fault of ours that we were made as we were made - experiments in a parallel being. This was not our choice. We did not volunteer to be as we are.

[...]

No other life forms know they are alive, and neither do they know they will die. This is our curse alone. Without this hex upon our heads, we would never have withdrawn as far as we have from the natural [...] Everywhere around us are natural habitats, but within us is the shiver of startling and dreadful things. Simply put: We are not from here. If we vanished tomorrow, no organism on this planet would miss us. Nothing in nature needs us.

[...]

We are aberrations - beings born undead, neither one thing nor another, or two things at once ... uncanny things that poison the world by sowing our madness everywhere we go, glutting daylight and darkness with incorporeal obscenities. From across an immeasurable divide, we brought the supernatural into all that is manifest. Like a faint haze it floats around us. We keep company with ghosts.

from Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race

via spurious

_______________________

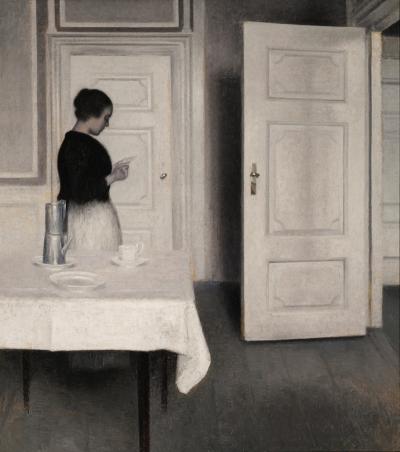

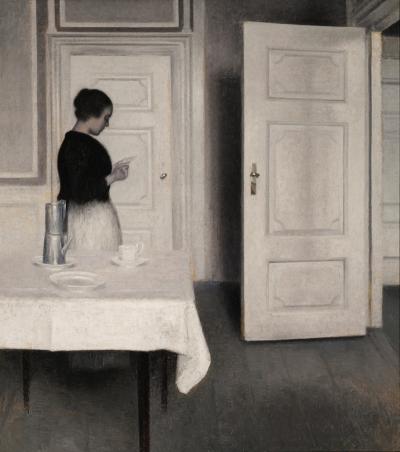

Ida Reading a Letter

Vilhelm Hammershøi

b. May 15, 1864

_______________________

Three Poems

Adrienne Rich

southern cross review

Diving Into The Wreck

Adrienne Rich

(....)

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

I stroke the beam of my lamp

slowly along the flank

of something more permanent

than fish or weed

the thing I came for:

the wreck and not the story of the wreck

the thing itself and not the myth

the drowned face always staring

toward the sun

the evidence of damage

worn by salt and sway into this threadbare beauty

the ribs of the disaster

curving their assertion

among the tentative haunters.

This is the place.

And I am here, the mermaid whose dark hair

streams black, the merman in his armored body

We circle silently

about the wreck

We dive into the hold.

I am she: I am he

whose drowned face sleeps with open eyes

whose breasts still bear the stress

whose silver, copper, vermeil cargo lies

obscurely inside barrels

half-wedged and left to rot

we are the half-destroyed instruments

that once held to a course

the water-eaten log

the fouled compass

...(more)

Credo of a Passionate Skeptic

Essay & Poems in Remembrance of Adrienne Rich monthly review

_______________________

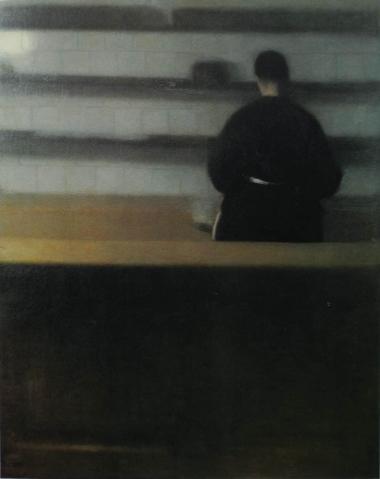

baker's shop

Vilhelm Hammershøi

_______________________

from In This World of 12 Months

Marcella Durand

Your voice carries easily through liquid; bridge is

halved by fog, as your tongue is divided in mist.

The fog of machinery augmented by steam.

Powered and then not powered, below a line, dark.

Cold, the weather has turned and out there, turbines still.

Water has divided, soft things and diverse: what

seemed one broke. Two cities and more. Lines reappear.

Across there is a wall also a door or steam

turns into fog. The bridge is two; light is taken.

People enjoy themselves, looking at glittering

potential floods. It is so nice to have a view.

|