|

photo - mw

_______________________

North

Seamus Heaney

I returned to a long strand,

the hammered curve of a bay,

and found only the secular

powers of the Atlantic thundering.

I faced the unmagical

invitations of Iceland,

the pathetic colonies

of Greenland, and suddenly

those fabulous raiders,

those lying in Orkney and Dublin

measured against

their long swords rusting,

those in the solid

belly of stone ships,

those hacked and glinting

in the gravel of thawed streams

were ocean-deafened voices

warning me, lifted again

in violence and epiphany.

The longship’s swimming tongue

was buoyant with hindsight—

it said Thor’s hammer swung

to geography and trade,

thick-witted couplings and revenges,

the hatreds and behind-backs

of the althing, lies and women,

exhaustions nominated peace,

memory incubating the spilled blood.

It said, ‘Lie down

in the word-hoard, burrow

the coil and gleam

of your furrowed brain.

Compose in darkness.

Expect aurora borealis

in the long foray

but no cascade of light.

Keep your eye clear

as the bleb of the icicle,

trust the feel of what nubbed treasure

your hands have known.’

Seamus Heaney

April 13, 1939 – Augus 30,t 2013

Photograph: Andrew Parsons/PA

Blackberry-Picking

Seamus Heaney

Late August, given heavy rain and sun

For a full week, the blackberries would ripen.

At first, just one, a glossy purple clot

Among others, red, green, hard as a knot.

You ate that first one and its flesh was sweet

Like thickened wine: summer's blood was in it

Leaving stains upon the tongue and lust for

Picking. Then red ones inked up and that hunger

Sent us out with milk cans, pea tins, jam-pots

Where briars scratched and wet grass bleached our boots.

Round hayfields, cornfields and potato-drills

We trekked and picked until the cans were full

Until the tinkling bottom had been covered

With green ones, and on top big dark blobs burned

Like a plate of eyes. Our hands were peppered

With thorn pricks, our palms sticky as Bluebeard's.

We hoarded the fresh berries in the byre.

But when the bath was filled we found a fur,

A rat-grey fungus, glutting on our cache.

The juice was stinking too. Once off the bush

The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour.

I always felt like crying. It wasn't fair

That all the lovely canfuls smelt of rot.

Each year I hoped they'd keep, knew they would not.

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Lost on the Map

Matthew Battles

orion

(....)

All maps tell stories of the world from particularized points of view, as the geographer Denis Woods likes to point out. “What the maps seem to reveal most,” Woods writes, “is our profound ambivalence about our place in the universe.” Responding to those ambiguities, maps can hide other ways of knowing the world. It’s altogether too easy to mistake the map for the territory, as the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges demonstrated in a very short story called “On Exactitude in Science,” imagining a long-ago kingdom whose cartographers produced “a map of the empire whose size was that of the empire”—an object that, for all the virtue and expertise that went into it, proved useless. “In the deserts of the West,” Borges concludes his story, “there are tattered ruins of that map, inhabited by animals and beggars.”

...(more)

via Steve Himmer

_______________________

photo by Dorothea Lange

Now (from Truth Game)

Tom Clark

with photos by Dorothea Lange

Vanitas Magazine

The imaginal representation of the mind,

the only world left to you. Continuing on. That poor

second best for which one would give everything

simply to have something to go on. The twisted

oaks. The stone steps descending

through the grove to where the light of morning

no longer bathes the contorted upper limbs

alone, but pierces them, at intervals, in the interstices,

with slender shafts that penetrate

the lower limbs and chequered

patterns of light and shade there made, all the way

to the bottom of the steep path.

Tom Clark, Truth Game, BlazeVOX 2013

_______________________

Sergey Loie

via (OvO)

_______________________

Crediting Poetry

Seamus Heaney

Nobel Lecture, December 7, 1995

(....)I also got used to hearing short bursts of foreign languages as the dial hand swept round from BBC to Radio Eireann, from the intonations of London to those of Dublin, and even though I did not understand what was being said in those first encounters with the gutturals and sibilants of European speech, I had already begun a journey into the wideness of the world beyond. This in turn became a journey into the wideness of language, a journey where each point of arrival - whether in one's poetry or one's life turned out to be a stepping stone rather than a destination, and it is that journey which has brought me now to this honoured spot. And yet the platform here feels more like a space station than a stepping stone, so that is why, for once in my life, I am permitting myself the luxury of walking on air.

*

I credit poetry for making this space-walk possible. I credit it immediately because of a line I wrote fairly recently instructing myself (and whoever else might be listening) to "walk on air against your better judgement". But I credit it ultimately because poetry can make an order as true to the impact of external reality and as sensitive to the inner laws of the poet's being as the ripples that rippled in and rippled out across the water in that scullery bucket fifty years ago....(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

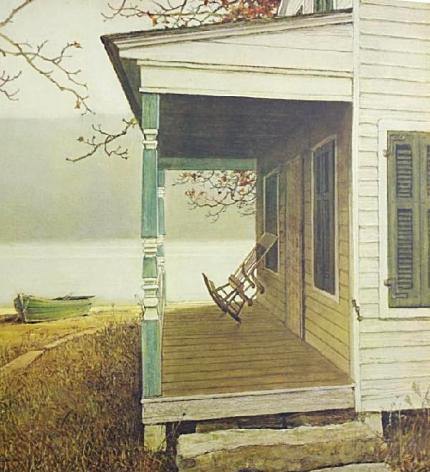

The Harvest Bow

Seamus Heaney

As you plaited the harvest bow

You implicated the mellowed silence in you

In wheat that does not rust

But brightens as it tightens twist by twist

Into a knowable corona,

A throwaway love-knot of straw.

Hands that aged round ashplants and cane sticks

And lapped the spurs on a lifetime of game cocks

Harked to their gift and worked with fine intent

Until your fingers moved somnambulant:

I tell and finger it like braille,

Gleaning the unsaid off the palpable,

And if I spy into its golden loops

I see us walk between the railway slopes

Into an evening of long grass and midges,

Blue smoke straight up, old beds and ploughs in hedges,

An auction notice on an outhouse wall—

You with a harvest bow in your lapel,

Me with the fishing rod, already homesick

For the big lift of these evenings, as your stick

Whacking the tips off weeds and bushes

Beats out of time, and beats, but flushes

Nothing: that original townland

Still tongue-tied in the straw tied by your hand.

The end of art is peace

Could be the motto of this frail device

That I have pinned up on our deal dresser—

Like a drawn snare

Slipped lately by the spirit of the corn

Yet burnished by its passage, and still warm.

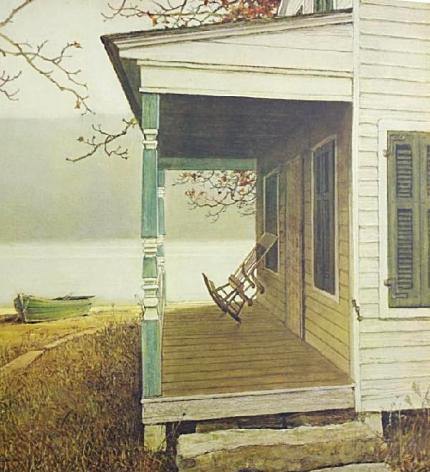

Martine Franck

1938 – 2012

_______________________

Walking

Thomas Bernhard

Translated from German by Kenneth Northcott

conjunctions

THERE IS A CONSTANT tug-of-war going on between all the possibilities of human thought and all the possibilities of a human mind's sensitivity, and between all the possibilities of human character.

Whereas, before Karrer went mad, I used to go walking with Oehler only on Wednesdays, now I go walking--now that Karrer has gone mad--with Oehler on Monday as well. ... If we hear something, says Oehler, on Wednesday we check what we have heard and we check what we have heard until we have to say that what we have heard is not true, what we have heard is a lie. If we see something, we check what we see until we are forced to say that what we are looking at is horrible. Thus throughout our lives we never escape from what is horrible and what is untrue, the lie, says Oehler. If we do something, we think about what we are doing until we are forced to say that it is something nasty, something low, something outrageous, what we are doing is something terribly hopeless and that what we are doing is in the nature of things obviously false. Thus every day becomes hell for us whether we like it or not, and what we think will, if we think about it, if we have the requisite coolness of intellect and acuity of intellect, always become something nasty, something low and superfluous which will depress us in the most shattering manner for the whole of our lives. For, everything that is thought is superfluous. Nature does not need thought, says Oehler, only human pride incessantly thinks into nature its thinking. ...(more)

_______________________

Fernando Pessoa

Beyond Another Ocean

Notes By C. Pacheco

To the memory of Alberto Caeiro

Translated by Chris Daniels

In a fevered feeling of being beyond another ocean

There were positions of a living more clear and limpid

And apparitions of a city of beings

Not unreal but livid with impossibility, sacred in purity and in nudity

I was the gateway to this null vision and the feelings were only the desire to have them

The notion of things beside themselves, each with their own inwardness

All were living in the life of remnants

And the mode of feeling was in the mode of living

But the form of those faces had the placidity of dew

Their nudity was a silence of forms without means of being

And there was wonder at all reality being only this

But life was life and it was only life

Often my thought works in silence

As smoothly as a greased machine moves without a sound

I feel good when it so moves and I immobilize

So as not to break the equilibrium that allows this to occur in me

I foresee that it is in these moments that my thought is clear

But I do not hear it and it works stealthily and in silence

Like a greased machine driven by a belt

And I can hear nothing but the serene sliding of the parts at work

Sometimes I recall that all other persons must feel the way I do

But they say it gives them a headache or causes dizziness

This recollection came to me as could any other

As for example the recollection that people do not feel the sliding

And they do not think what they do not feel

...(more)

_______________________

La maison noire

East Hampton, New York

1964

Jeanloup Sieff

_______________________

"The quotation in my works are like robbers lying in ambush on the highway to attack the passerby with weapons drawn and rob him of his conviction."

(...)

Benjamin, who for his entire life pursued the idea of writing a work made up entirely of quotations, had understood that the authority involved by the quotation is founded precisely on the destruction of the authority that is attributed to a certain text by its situation in the history of culture.

(...)

This particular way of entering into a relation with the past also constitutes the foundation of the activity of a figure with which Benjamin felt an instictive affinity: that of the collector. The collector also "quotes" the object outside its context and in this way destroys the order inside which it finds its value and meaning.

(...)

The interruption of tradition, which is for us now a fait accompli, opens an era in which no link is possible between old and new, if not the infinite accumulation of the old in a sort of monstrous archive or the alientation effected by the very means that is supposed to help with the transmissin of the old. Like the castle in Kafka's novel, which burdens the village with the obscurity of its decrees and the multiplicity of its offices, the accumulated culture has lost its living meaning and hangs over man like a threat in which he can in no way recognize himself. Suspended in the void between old and new, past and future, man is projected into time as into somethin alien that incessantly elludes him and still drags him forward, but without allowing him to find his ground in it.

Giorgio Agamben, The Man Wiithout Content, translated by Georgia Albert

_______________________

The Art Of Disappearing

Naomi Shihab Nye

When they say Don’t I know you?

say no.

When they invite you to the party

remember what parties are like

before answering.

Someone telling you in a loud voice

they once wrote a poem.

Greasy sausage balls on a paper plate.

Then reply.

If they say we should get together.

say why?

It’s not that you don’t love them any more.

You’re trying to remember something

too important to forget.

Trees. The monastery bell at twilight.

Tell them you have a new project.

It will never be finished.

When someone recognizes you in a grocery store

nod briefly and become a cabbage.

When someone you haven’t seen in ten years

appears at the door,

don’t start singing him all your new songs.

You will never catch up.

Walk around feeling like a leaf.

Know you could tumble any second.

Then decide what to do with your time.

Red suitcase: poems

Naomi Shihab Nye google books

Fuel: poems

Naomi Shihab Nye google books

Never in a hurry: essays on people and places

Naomi Shihab Nye google books

The flag of childhood: poems from the Middle East

edited by Naomi Shihab Nye google books

This Same Sky: A Collection of Poems from Around the World

edited by Naomi Shihab Nye

google books

Naomi Shihab Nye: A Bill Moyers Interview_______________________

Sarah Moon

Martine Franck

1983

_______________________

Kindness

Before you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth.

What you held in your hand,

what you counted and carefully saved,

all this must go so you know

how desolate the landscape can be

between the regions of kindness.

How you ride and ride

thinking the bus will never stop,

the passengers eating maize and chicken

will stare out the window forever.

Before you learn the tender gravity of kindness,

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road.

You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans

and the simple breath that kept him alive.

Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes

and sends you out into the day to mail letters and

purchase bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

it is I you have been looking for,

and then goes with you every where

like a shadow or a friend.

Naomi Shihab Nye

from The Words Under the Words: Selected Poems

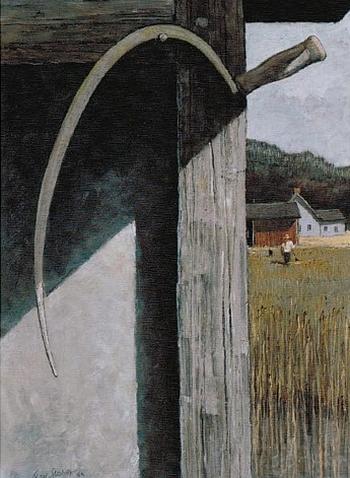

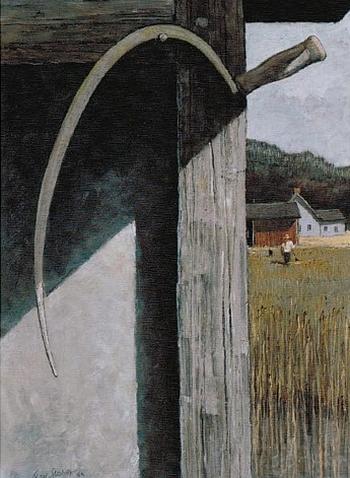

Eric Sloane

_______________________

Challenges of the social life of language

John Edwards

When we consider two obvious facts — that virtually everyone becomes a fluent speaker of at least one language, and that language is central to social life — we can see that most of us are quite sociolinguistically talented. Whether we’re consciously aware of it or not, we know quite a lot about many of the intricacies of “the social life of language.” This doesn’t mean, however, that our knowledge is complete or wholly accurate. Here are ten illustrations of the point ...(more)

_______________________

A Lecture on Johnson and Boswell

Jorge Luis Borges

Excerpted from "Class 10: Samuel Johnson as Seen by Boswell. The Art of Biography. Johnson and His Critics. Monday, November 7, 1966," in Professor Borges: A Course on English Literature, a compilation of twenty-five lectures Borges gave in 1966 that has been translated into English for the first time by Katherine Silver. It will be published by New Directions on July 31.

(....)

There is a Hindu school of philosophy that says that we are not the actors in our lives, but rather the spectators, and this is illustrated using the metaphor of a dancer. These days, maybe it would be better to say an actor. A spectator sees a dancer or an actor, or, if you prefer, reads a novel, and ends up identifying with one of the characters who is there in front of him. This is what those Hindu thinkers before the fifth century said. And the same thing happens with us. I, for example, was born the same day as Jorge Luis Borges, exactly the same day. I have seen him be ridiculous in some situations, pathetic in others. And, as I have always had him in front of me, I have ended up identifying with him. According to this theory, in other words, the I would be double: there is a profound I, and this I is identified with—though separate from—the other. Now, I don’t know what experiences you might have had, but sometimes this happens to me: usually at two particular kinds of moments—at moments when something very good has happened, and, above all, at moments when something very bad has happened to me. And for a few seconds, I have felt: “But, what do I care about all this? It is as if all of this is happening to somebody else.” That is, I have felt that there is something deep down inside me that remains separate.

...(more)

_______________________

Dora Maar

Man Ray

1936

_______________________

Outsourcery: biography by any other's name

kevin mcpherson eckhoff's "Jumble" from his Their Biography

Gary Barwin

jacket2

A conversation with kevin mcpherson eckhoff where I speak in italics and he speaks in normal.

Aloof!

You didn’t even write this! You solicited participants to contribute to “their biography” of you. Or as you term it in the subtitle, “an organism of relationships amassed by and about the object often identified as kevin mcpherson eckhoff.” Maybe that’s a definition that works for literature or a poem: “an organism of relationships amassed by & about the object often identified as [literature or poem]. Except there’d have to be something about end rhymes and the soul.

The end of the soul is synonymous with exceptions. Synonyms are a kind of rhyme. Relationships dynamic create errors of within, and this betweenness of everything is a reality field of meaningful electrons. As a human invention, poetry mitigates such betweens. I suspect bpNichol may have seen poems as such halfway points. The not-quite-you plus not-quite-me is what breathes within the enclosures of words. Words are actions. Actions alone won’t save us. Redemption isn’t a hidden MEaning or a hidden YOUaning, but an ever-apparent WEaning. Spoiler alert: I cheated & read ahead!

Sneaky!

The crossword form is a striking visual-verbal icon. A very particular image which invites the participation of the reader. Or perhaps, the imagined participation of the reader (who thus becomes a kind of directed writer.) And it challenges readers to search their own knowledge (collection) of words and their meanings by being prompted with the definitions or synonyms of these words. The ‘jumble’ aspect to this is that all these words elicited through their synonyms or meanings, yield the hidden word, the word to be filled in in the circles at the top of the page. In this case—spoiler alert—your name. Which, I note is also a construction. It was made by your family. And then, I believe, modified/added to by you. This kind of jumble-crossword is often associated with school and childhood, especially when all of the clues point to aspects of a person. This makes it a particularly apt choice for ‘biography.’ And: I think of how people are sometimes taught to ‘read’ a poem: at the end of the process, they are expected be able to find the correct and hidden ‘meaning’ if they’ve decoded the poem properly. They could write this hidden meaning at the top of the text. Another poem ‘solved’!

My name is barely mine. And it’s rarely a solution for anything. Are poems solutions or dissolutions? The empty crossword is already a suspension, itself. Are poems puzzles? Depends on your GPA. As a writer, I don’t wanna know any of the answers before my readers. And I never want to write the same book thrice. I want to write books as a stranger to them.

...(more)

_______________________

Eric Sloane

1905 – 1985

_______________________

An Americana of Tools and Manners

Eric Sloane's Nostalgia

Abigail Walthausen

common - place

(....)

Much like an ethnographic historian, Sloane relied on the contradictory beliefs that a particular culture was rapidly and inevitably disappearing, and that reliable sources could be gathered about it. Salvage ethnography—or here perhaps rescue archaeology—is a form of whimsy in its own right, in that it requires a suspension of disbelief, a faith in vision or project over method.

Sloane's oeuvre is without question problematic, yet his best work has an undeniable appeal. A Reverence for Wood (1965) and A Museum of Early American Tools (1964) both have drawn innumerable readers to the study of early Americana. In a recent conversation, Gregory Landrey, a director and furniture expert at Delaware's Winterthur Museum and Library, told me that when he was eleven, A Reverence for Wood changed his life. Typography designer Dave Nalle has not only designed a number of fonts around Sloane's book lettering, he also calls A Reverence for Wood "remarkable and almost mystical." It is one of those unclassifiable classics with a bit of a cult following among lovers of popular histories, those who work with wood, and those who embrace bygone things, from barns to bells to introspection. Sloane's work is nearly ubiquitous, yet the sum of his legacy remains in many ways unknown and unexplored. He was an artist who was resolutely unfashionable, yet his importance in shaping how generations of readers thought about what early America looked like must be acknowledged—he is the Norman Rockwell of things, of technology and industry.

...(more)

_______________________

Eric Sloane

_______________________

“Property is (still) theft!”

From the Marx-Proudhon Debate to the Global Plunder of the Commons

Lorenzo Coccoli

Comparative Law Review, Vol 4, No 1 (2013)

Abstract

Generally speaking, in our philosophical tradition it is usual to conceive the issue of property and theft in terms of a rigid opposition. Whether a right of nature (Locke) or an institution established by the Sovereign’s sword (Hobbes), private property constitutes the safest defence against thieves, robbers and outlaws. The owner, legitimately guaranteed in the enjoyment of his properties, has to be protected (or, if necessary, to protect himself) from the extra-legal violence of theft. Nevertheless, there is at least another story to be told, another trace (if not actually a tradition) to be reconstructed, rescued from the oblivion in which our mainstream history of philosophy seems to have banished it: that is, the idea that property and theft, far from being polar opposites, are on the contrary two faces of a same coin. In the following, we’ll try to focus our attention on a single episode of this alternative line of thought, in order to clarify its present implications and its possible political relevance in the terms of an opposition against global capital’s new dynamics. We are referring to the controversy that, in a certain sense, sanctioned the passage from the “utopian” to the “scientific” form of socialism: the Proudhon-Marx debate on property and theft.

_______________________

Eric Sloane

_______________________

How We Killed Privacy -- in 4 Easy Steps

Stop blaming the NSA. We did this to ourselves.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Kelsey D. Atherton

foreign policy

Privacy in 2013 does not exist as we knew it in 2000.

But don't be fooled: The almost complete erosion of what we would have considered our private spaces at the beginning of this millennium is not entirely -- nor even mainly -- a result of the National Security Agency's surveillance. While nobody should doubt that the government's electronic spying is intrusive, we largely let online privacy slip away without any assistance from security agencies. Each step along the way was, for the most part, understandable and reasonable rather than nefarious. But the fact is that privacy in the United States is not what it used to be, and until we realize that, our debate about electronic privacy -- Manichean as it is, and focused almost exclusively on the relationship between the government and its citizens -- will fail to resurrect its value.

Four distinct factors have interacted to kill electronic privacy: a legal framework that has remained largely static since the 1970s, significant changes in our use of rapidly evolving technology, commercial providers' increasingly intrusive tracking of our every online habit, and a growth in non-state threats that has made governments the world over obsess about uncovering these dangers. Only by understanding the interaction between these factors can we begin the necessary discussion about what privacy means in the 21st century -- and how to forge a new social compact to address the issue.

...(more)

_______________________

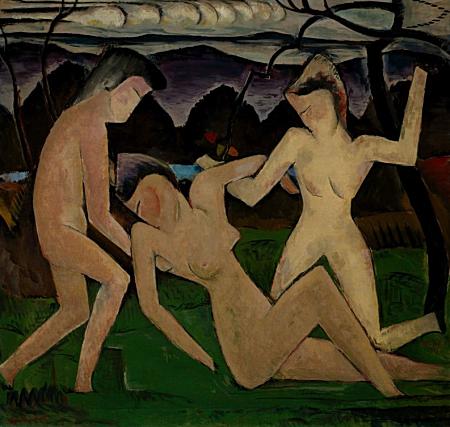

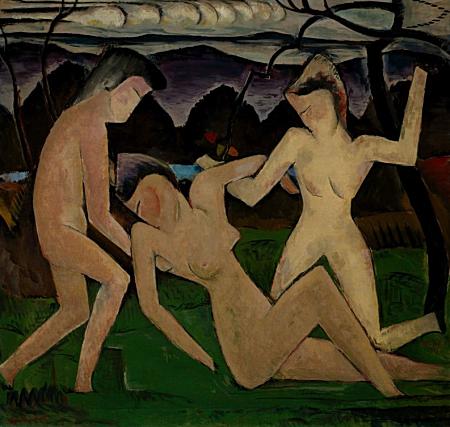

Departure of Summer

1914

Man Ray

b. August 27, 1890

_______________________

Modern travel, far from the madding crowdsourcing

Tom Jokinen

Reviewed here: The Longest Road: Overland in Search of America, from Key West to the Arctic Ocean, by Philip Caputo; Granta 124: Travel, edited by John Freeman

Special to The Globe and Mail

(....)

We live in a connected world, and the connections are commercial: Your destination, whether you go there or just dream of it, is revealed in its Starbucks and Motel 6 options, TripAdvisor ratings. No wonder Lonely Planet, the best-selling publisher of travel guides, is downsizing: 80 out of 400 staff positions were “made redundant” this summer. Books can’t compete with social media and at-your-fingertips crowdsourcing.

So it’s not enough, as Norman Lewis, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Freya Stark and Bruce Chatwin once did, to treat travel as a literary muse, to discover the undiscovered and report back. It has been done: Every square inch of dry earth is accounted for and has already been visited by liberal-arts students in Arc’teryx fleece. Modern travel writing wants more: value-added, a gimmick, and, if possible, an emphasis on the writer’s inner journey, not so much the scene that greets him when he gets off the train. It’s a literature of anxiety and commercial panic: Will a trip to Bali help me get over my divorce and fall in love and find the pedicure that will change my life forever and sell this book?

...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

‘Delicious turbulence’

T.E. Rosenberg

(....)

Rather than enclosing brackets, or, boundaries, I would like to see the term ‘material thinking’ used as a focus, a point of congruence, through which, into and from which, different discourses may be br ought together to gather and move, to connect and maybe release hold on each other in order to play a part in understanding, and producing new practices in an expanded field of design.

‘Material thinking’ welds together the abstract spaces of cognitive activity and the materiality of the world in the physical processes through which it is formed; both through an isomorphism where the patterns and processes of material/physical processes and thinking processes are recognized in each other, in a mirroring of each to each, but also in the very real collapse of distinctive boundaries between the physical world (considered as interactions of material and energy) and cognitive abstraction (reflective and speculative activity of the mind considered trans-corporeally) that occurs in practice – and particularly design practice, with its concern for the nitty-gritty of the everyday.

If I was to propose a first article for the journal – not necessarily a position statement but a declaration of a first interest - it would be on ‘perturbation and turbulence’. I am drawn to enquire into the ‘delicious turbulence’ I describe above; the tact-full engagement of body and thoughts with the movements of matter. In the description above ideological instability is represented by a physical event – an event where I as child am knocked down by the waves. I am interested in the way representation acts to connect and collapse the physical and the ideal in practice. But I am particularly interested in ‘turbulence’ as a technique in thinking, in representation and the act, that can be used to challenge the regularities of thought, in and about design. I am also eager to explore how design may be ‘turbulent’ in the way it enters the world; exploring the possibility for designing and the designed ‘object’ (service, system, text , product) to be used to dialectically engage with the regularities of social and cultural practices and the expectation for its objects and open them up to the possibility of being other.

...(more)

Studies in Material Thinking

_______________________

The Atrophy of Private LIfe

Jennifer Moxley

In the heavy fashion magazines strewn here and there around the house the photos of objects and people mouth the word “money,” but you, assuming no one wants you anymore, mishear the message as “meaning.” Arousal follows. The lives of the rich are so fabulous! The destruction of the poetical lies heavily on their hands, as on their swollen notion that we are always watching. There is nothing behind the mask. Nothing suffocating under its pressure, no human essence trying to get out.

Awareness, always awareness. Don’t you see how these elaborate masks are turning you into a zombie? The private life is not for the eye but for the endless interior. It is trying to push all this crap aside and find the missing line. Nobody, least of all the future, cares about the outcome of this quest.

It is easy to lose, through meddling or neglect, an entire aspect of existence. And sometimes, to cultivate a single new thought, you need not only silence but an entirely new life.

Find the missing line (PoemTalk #55)

Jennifer Moxley, 'The Atrophy of Private Life' jacket2

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Æolian Harp

Jennifer Moxley

for and after John Wilkinson

Ribboning dreams unspool in a discarded heap

of oppressive gravity, remember when life

was still compelling, your talents in truck

for fealty, the luxurious future at hand, pastoral

lack of capital in the vernal fervor couched;

"make something of yourself," for example a man

or a picture of archaic pride atop an old armoire,

"pull yourself up by your bootstraps," as did those

bargained away first sons whose whims were nursed

by sins far worse than sacrifice, remember when

you thought yourself less played upon by circumstance,

little by little by literal evidence you’ve come to be

misplaced, the time it took to spin these words has

long since disappeared, befooled by work the reading

of which another dreamer will unspool, do take your place

in pushing back the clock, small perks won’t allow

a stay of revelation, the fear of ignorance has

become the vested knowledge of stupidity, choice

the slow extinction of your faculty for longing,

and the place you would go back to of an orbit unreal.

Jennifer Moxley at EPC, the Poetry Foundation and PennSound

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

How consciousness works

Michael Graziano

Aeon

(....)

Lately, the problem of consciousness has begun to catch on in neuroscience. How does a brain generate consciousness? In the computer age, it is not hard to imagine how a computing machine might construct, store and spit out the information that ‘I am alive, I am a person, I have memories, the wind is cold, the grass is green,’ and so on. But how does a brain become aware of those propositions? The philosopher David Chalmers has claimed that the first question, how a brain computes information about itself and the surrounding world, is the ‘easy’ problem of consciousness. The second question, how a brain becomes aware of all that computed stuff, is the ‘hard’ problem.

I believe that the easy and the hard problems have gotten switched around. The sheer scale and complexity of the brain’s vast computations makes the easy problem monumentally hard to figure out. How the brain attributes the property of awareness to itself is, by contrast, much easier. If nothing else, it would appear to be a more limited set of computations. In my laboratory at Princeton University, we are working on a specific theory of awareness and its basis in the brain. Our theory explains both the apparent awareness that we can attribute to Kevin and the direct, first-person perspective that we have on our own experience. And the easiest way to introduce it is to travel about half a billion years back in time.

...(more)

_______________________

Fragments of a Broken Poetics

Jennifer Moxley

from Chicago Review, Spring 2010

I

The poet's psychology, visible only to the poet's friends, floats lightly over the surface of the poem. It discolors some words temporarily, but never quite settles into them—provided those words belong together. If so, they will eventually cast off this shadow; if not, it will eventually smother them. Thus, it is the poem, not the poet, that we love. Through it the singular becomes shared, the transitory eternal.

II

The eternal, typically a conceit standing in for the hope of civilizations, acts differently in poetry. The words of the poem, once happily configured, may wait a very long time for a reader to read them as they were meant to be read. This is the eternity of the poem.

III

A poet only needs one poem, a poem only one reader. Moving from singular to shared in this instance is a rudimentary economy. It is less affecting than a mortal kiss, more than a passing conversation. The poem will always provoke an acute desire to know its creator, "acute" because hopeless.

IV

Disembodied, the poem provokes longing. Its incorporeity is inscribed in myth: the severed head of Orpheus adrift on the Aegean Sea. Though separated, the head continues to sing. The song it sings is either a lament of exile from the body or a celebration of freedom from its material prison, depending on the direction of the winds.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Admitting the Communist Desire

A Conversation With Jodi Dean

by Joseph G. Ramsey

Ramsey: Throughout The Communist Horizon you frame an opposition between desire, which you tend to align with communism, and drive which you generally identify as a form of enjoyment that ensnares subjects in the existing networks of communicative capitalism? What does it mean to formulate communism from the standpoint of desire? Is drive always politically bad/suspect? Or can we speak of a drive that would be oriented towards communism?

Dean: Drive isn’t oriented toward something; it’s shaped from loss and just attaches to any old thing, easily moving from one object of intense attachment to another (I’m tempted to say that with respect to politics drive manifests itself as a kind of political Asperger’s syndrome; you know, how everyone is at one moment obsessed with binary oppositions, then fracking, then “isms,” then debt). It’s a repetitive circuit that results from failure, where people get off (get a little nugget of enjoyment) from failing. So drive also structures melancholia, as we see in Freud’s discussion in Mourning and Melancholia where he uses the language of drive that he develops in the The Instincts and Their Vicissitudes. This language is reflexive, inward-turning as well as self-loathing. I argue that communicative capitalism (and consequently contemporary democracy as well as contemporary media networks) exhibit the reflexive structure of drive. Examples: getting stuck in the intertubes, clicking around, looking but not finding, repeating the same gestures, having the same pointless arguments, getting invested in them even when (or especially when) they don’t matter.

Now, it’s possible for drive’s repetitions to have destructive effects as with vicious circles in feedback systems or when bubbles burst in markets. Žižek describes this version of drive as a kind of prior clearing that creates the space for something new. I don’t disagree with this, but I don’t think it provides a politics (or, the politics it suggests is one of waiting for the rupture—which Žižek sometimes suggests when he appeals to Bartleby or when he emphasizes the importance of thinking rather than getting caught up in activity; I prefer to think of not getting caught up in activity in terms of working to break the hold of drive’s repetitions). Desire doesn’t turn inward; it looks outward, toward the horizon. A communism thought in terms of desire, then, is one that recognizes the necessity of breaking out of the trap of reflexivity, of installing a gap.

At this point, I am focused on thinking of communism in terms of a collective desire for collectivity. Because I understand communicative capitalism as structured in terms of drive, I don’t see the benefit in theorizing communism this way—communism is a break with this, a rupture of the circuit that lets us look outwards.

...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

philosophy from the preposterous universe

Sean Carroll interviewed by Richard Marshall.

3am

Sean Carroll is the uber-chillin’ philosophical physicist who investigates how the preposterous universe works at a deep level, who thinks spats between physics and philosophy are silly, who thinks a wise philosopher will always be willing to learn from discoveries of science, who asks how we are to live if there is no God, who is comfortable with naturalism and physicalism, who thinks emergentism central, that freewill is a crucial part of our best higher-level vocabulary, that there aren’t multiple levels of reality, which is quantum based not relativity based, is a cheerful realist, disagrees with Tim Maudlin about wave functions and Craig Callender about multiverses, worries about pseudo-scientific ideas and that the notion of ‘domains of applicability’ is lamentably under-appreciated. Stellar!

(....)

The public spat between physics and philosophy is just silly, more a matter of selling books or being lazy than any principled intellectual position. Most physicists know very little about philosophy, which is hardly surprising; most experts in any one academic field don’t know very much about many other fields. This ignorance manifests itself in a couple of ways. First, a lot of scientists are quite comfortable with simplistic philosophy of science. This usually doesn’t matter, but there are cases where good philosophy has something to offer, and scientists rarely put in the work necessary to understand what that good philosophy has to say. Second, scientists tend to think of philosophy as a service discipline – what good does it do for my practice of science? The answer is almost always “no good at all,” which they then translate into thinking that philosophy has no real purpose. The truth is that almost all scientific work can proceed quite happily without philosophy – you can be very good at driving a car without knowing how an engine works. But when it’s important, philosophy very important indeed.

Very few philosophers, by contrast, are going to accuse science of being worthless. Nevertheless, it’s no surprise that there are problems of appreciation and understanding flowing in that direction as well. The only remedy, if one is interested in finding one, is constant interaction and communication.

My own default position is that respectable people in other academic fields probably have something interesting to say, even if I don’t immediately understand it. Not always true, of course – there are pockets of nonsense within every discipline. But the less I understand about the basics of some field, the less likely I am to start declaring it to be useless and antiquated.

(....)

There is plenty of room for supernatural, unknown forces. There just isn’t any need for them, credible evidence that they exist, or justification for taking them seriously in this day and age.

The elevator-pitch version of my objection to Templeton is that, as you say, they are committed to spreading the idea that science and religion are gradually reconciling with each other. Not only is this idea completely false, it strikes at the heart of the real-world issues on which philosophers and fundamental physicists can potentially have the most impact. When I try to come up with a better cosmological scenario to help explain the low entropy near the Big Bang, some members of the general public might think it’s interesting, but a much larger number are utterly unaffected. But every one of those people has some (likely implicit) view of how the world works, and the implications of that view are necessarily crucial.

Is there life after death? Is morality handed down by God? Does human life have intrinsic meaning and purpose? These are questions where what we have learned over the last few centuries from science and philosophy has an enormous impact, and it’s not in the direction that the Templeton Foundation would like people to believe. There is no life after death, morality is invented by human beings rather than handed down from outside, and any meaning or purpose to human life is something that we need to give it rather than something we get from the universe itself. These are important ideas to everyone, and we should be doing everything in our power to make them better understood. Templeton is not helping.

...(more)

_______________________

“Outside the window falls the rain”

Tadeusz Dąbrowski

translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

agni

Outside the window falls the rain. In another part of town

onto the sidewalk falls a man. Somewhere in the world

a word falls from someone’s lips that changes the course

of history. At just the same time from millions of lips

fall words meaning nothing and counteract

that single one. In the rotisserie turns a chicken.

In the cot our happiness turns in its sleep.

Our bodies turn into ashes. Our life

goes on in every instant in every word.

.....................................................

This is the first line. This line is meaningless – an interview with Tadeusz Dąbrowski

by SJ Fowler

3am

3:AM: Your poetry seems to be focused on creating careful linguistic pictures driven by a philosophical or observational underpinning. Do you work with a specific style or methodology, or is the writing process very free?

Tadeusz Dąbrowski: No methodology, no linguistic rafting. I prefer rather calm sailing against the current, towards the source. Or towards the heart of the darkness. Methodology as well as manifestos tend to kill poetry, a poem is impossible to be planned. Planning of a form leads us to artificiality, while planning of your subject – to ideologisation.

But at the same time I don’t believe poets of “liberated phrase/imagination”, those who say they are carried by the flow of the language and who actually don’t know what their poetry is about because the current is rapid and uncontrollable. The problem is that “the current” is fast especially where the river lacks depth. I try to keep my works within the bounds of discipline. But even so my text will occasionally deviate from its course, and such an unpredictable deviation, or in other words, the distance at which the text retreats, is a source of self-cognition for me. But it is my duty to be in charge of maps and to be at the helm. Linguism and philosophy… A poem doesn’t go all the way from one to the other because the division into form and content is fictitious. The whole of poetry and philosophy takes place in language. However, the former, in my opinion, strips the reality of words, whereas the latter textualizes this very same reality.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

On the phenomenon of bullshit jobs

David Graeber

libcom

(....)

The answer clearly isn’t economic: it’s moral and political. The ruling class has figured out that a happy and productive population with free time on their hands is a mortal danger (think of what started to happen when this even began to be approximated in the ‘60s). And, on the other hand, the feeling that work is a moral value in itself, and that anyone not willing to submit themselves to some kind of intense work discipline for most of their waking hours deserves nothing, is extraordinarily convenient for them.

(....)

This is a profound psychological violence here. How can one even begin to speak of dignity in labour when one secretly feels one’s job should not exist? How can it not create a sense of deep rage and resentment. Yet it is the peculiar genius of our society that its rulers have figured out a way, as in the case of the fish-fryers, to ensure that rage is directed precisely against those who actually do get to do meaningful work.

(....)

If someone had designed a work regime perfectly suited to maintaining the power of finance capital, it’s hard to see how they could have done a better job. Real, productive workers are relentlessly squeezed and exploited. The remainder are divided between a terrorised stratum of the, universally reviled, unemployed and a larger stratum who are basically paid to do nothing, in positions designed to make them identify with the perspectives and sensibilities of the ruling class (managers, administrators, etc) – and particularly its financial avatars – but, at the same time, foster a simmering resentment against anyone whose work has clear and undeniable social value. Clearly, the system was never consciously designed. It emerged from almost a century of trial and error. But it is the only explanation for why, despite our technological capacities, we are not all working 3-4 hour days.

...(more)

via Dialogic

_______________________

Logistics and Opposition

Alberto Toscano

Mute

(....)

... it is also possible, and indeed necessary, to think of logistics not just as the site of interruption, but as the stake of enduring and articulated struggles. Here there remains much to digest and learn from in the ongoing research of labour theorist and historian Sergio Bologna, an editor in the 1970s of the journal Primo Maggio, which carried out seminal inquiries into containerisation and the struggles of port workers. Countering those ‘post-workerists’ who have equated post-Fordism with the rise of the cognitive and the immaterial (and basically with the ubiquity of a figure of work patently traced on that of the academic or ‘culture worker’), Bologna notes that the key networks that condition contemporary capitalism are neither affective nor simply digital, but involve instead the massive expansion and constant innovation in the very material domain of logistics – in particular of ‘supply chain management‘, conceived of in terms of the speed, flexibility, control, capillary character and global coverage of the stocking, transport and circulation of services and commodities.

(....)

... what is paramount is what this logistical view of post-Fordism tells us about the character of antagonism, and specifically of class struggle. Narcissistically mesmerised by hackers, interns and precarious academics, radical theorists of post-Fordism have ignored what Bologna calls ‘the multitude of globalisation’, that is all of those who work across the supply chain, in the manual and intellectual labour that makes highly complex integrated transnational systems of warehousing, transport and control possible. In this ‘second geography’ of logistical spaces, we also encounter the greatest ‘criticality’ of the system – though not, as in the proclamations of The Coming Insurrection, in the isolated and ephemeral act of sabotage, but in a working class which retains the residual power of interrupting the productive cycle – a power that offshoring, outsourcing, and downsizing has in many respects stripped from the majority of ‘productive’ workers themselves.

...(more)

via I Cite

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Trying to Pray

James Wright

This time, I have left my body behind me, crying

In its dark thorns.

Still,

There are good things in this world.

It is dusk.

It is the good darkness

Of women's hands that touch loaves.

The spirit of a tree begins to move.

I touch leaves.

I close my eyes and think of water.

Depressed by a Book of Bad Poetry, I Walk Toward an Unused

Pasture and Invite the Insects to Join Me

Relieved, I let the book fall behind a stone.

I climb a slight rise of grass.

I do not want to disturb the ants

Who are walking single file up the fence post,

Carrying small white petals,

Casting shadows so frail that I can see through them.

I close my eyes for a moment and listen.

The old grasshoppers

Are tired, they leap heavily now,

Their thighs are burdened.

I want to hear them, they have clear sounds to make.

Then lovely, far off, a dark cricket begins

In the maple trees.

_______________________

photo - mw

Paolo Ventura

_______________________

The Perforated Map, and Writing the Unknown

Eléna Rivera

(....)

In English my mind has to make deep circles to get at what seems obvious. The circles have gotten smaller, but I continue to travel, not as a tourist but going back to places I have lived in before, in other languages, other cultures. In writing as in life, I have moved, and returned to ; I have wandered around and desired. Like re-reading a book at different ages, I have re-read places at different ages. In the same way reading Henry James will create a different space from reading Frederick Douglass, these writers, like travel, are the maps, and my words come out of a longing to participate, to insert myself, to become "one with" : Henry James as an observant guide for mapping the subtleties of human existence ; whereas reading Frederick Douglass I realized that I was a slave in my own mind. Both of these writers, and their words, became maps for emotions that I never quite grasped, for ideas that I hungered for. James I came to by reading George Oppen, “approached the window as if to see.” Reading James led me back to that thirteen year old just come by boat to America who looked out of a window of a tall Manhattan building. Frederick Douglass and “the Want of Liberty” became the map for me to explore all of the mistakes, errors, accidents of my life, the economic, environmental, racial and personal violence that I had been exposed to and experienced.

...(more)

.....................................................

Transatlantica

- Revue d'études américaines. American Studies Journal

Selections from The Perforated Map [pdf]

Eléna Rivera

Ars Poetica

Inaudible perhaps

this moment, inevitably

washing face and hands

it slips

away, forgotten

by our “progress.”

I am drawn to explore aspects,

features of the seen/heard,

which limp still catch light,

colors, twigs of hope.

I slip in your side,

indistinct,

a moistened hand,

a gangling sinew

where the space of the poem

cascades

as years peel one after another

their films of silence.

Bodies encounter effigies

and turn, bloodless, unable

to defend themselves from distance—

the soundless features

of today holds

unwittingly the lineaments

returns the words home,

opens hinges.

Eléna Rivera at Shearsman Books

In Respect of Distance Eléna Rivera a chapbook from Beard of Bees _______________________

Drying Nets, Treboul Harbour

1930

Christopher Wood

d. August 21, 1930

_______________________

A world without feeling

Stephen Mitchelmore

This Space

(....)

... Modern writers might suggest that, once cleared of sentiment, the novel has the potential to be the ground of truth, of clinical analysis, a place in which we are no longer hoodwinked; a world without feeling. Except of course this is maintained on a contradiction: storytelling is the means to this world. Beckett's comedy confirms that even the most constricted, stripped-down story is emotional. Even the most overtly heartless, realistic novel relies on a certain kind of sentiment. Swooning under the gaze of its gritty beloved, it refuses the possibility of error or unknowing. Contemporary fiction's impatience with this paradox and its refusal to confront it in form and content actually constitutes the bulk of contemporary fiction, and might thereby trace the fate of humanism. Apparently free of heavenly abstraction, humankind still struggles to ground its story and still swims in a sea without shore, and so, to save itself, clings like Pincher Martin to one remaining outcrop, repressing its fate.

Can the novel let go? The question is the starting point of Vila-Matas' Montano's Malady with its epigraph: What will we do to disappear? The writer's block suffered by the title character suggests it is necessary. He must stop writing in order to write. The author of the epigraph has emphasised that there is nothing negative in 'not to write': "it is intensity without mastery, without sovereignty, the obsessiveness of the utterly passive". If letting go is then obsessive passivity, how might that be written?

...(more)

_______________________

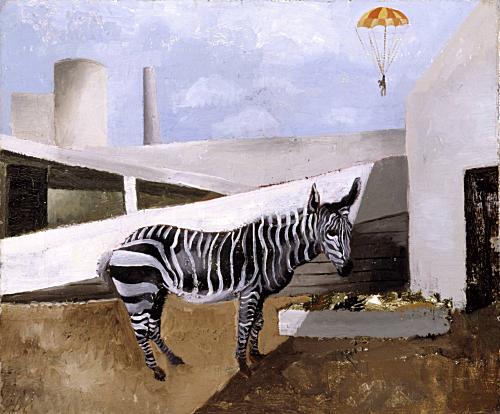

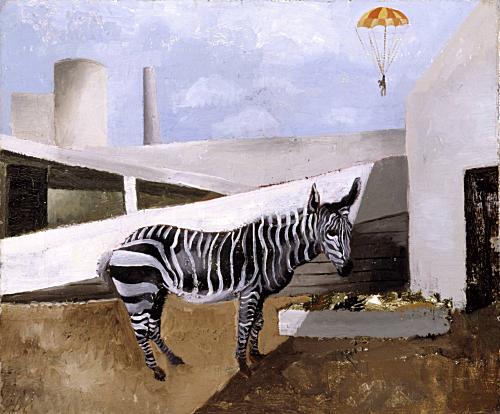

Zebra and Parachute

Christopher Wood

1930

_______________________

The Problem of Life

Dylan Trigg

Side Effects

(....)

Beyond life, another life goes on. It is a life that speaks through the grave, and in doing so, beckons toward a celestial sphere, in which the body is nothing more than the memory of dust.

But in the memory, there is dread as well as affirmation. Those of us who live in the shadow of Copernicus, must chose whether to adopt an eliminative approach to the cosmos or to withdraw into a pre-modern account, which privileges the irreducible enigma of things long before they have been touched by human desire. In each case, we are guided by the fundamental uncanniness of life itself, a life that ostensibly has no place in the universe, except as an appearance of the living dead.

...(more)

_______________________

An Infected Wound

Matthew Cunningham-Cook

full stoop

In the eye of a country that continues — 46 years after King announced it at Riverside Church — to be the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today, three books have arrived. They grapple with what our nation’s war apparatus has wrought in our names. They attempt to figure how such acts have, with an air of permanence, seized our national imagination.

The first two, Kill Everything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam by Nick Turse, and Hardhats, Hippies and Hawks: The Vietnam Antiwar Movement in Myth and Memory, by Penny Lewis, are revisionary, attempting (and largely succeeding) to rub saltwater into an infected wound. And it is infected. The capitalist class in the United States has been successful at creating the narrative that 1) the Vietnam War was about “democracy” and that the main victims were military in nature, and 2) that the movement against it was entirely composed of the petit bourgeoisie.

Both of these narratives are crushingly dangerous. The first purposely elides the fact that what the United States military actually did in Vietnam was nothing short of some of the greatest crimes of the 20th century, easily deserving to be placed among Leopold’s colonial massacres in the Congo or Hitler’s insane Aryan crusade. The second narrative deliberately attempts to mark a breaking point in the Vietnam War movement by citing opponents of the war as economically privileged, conveniently erasing the vibrant history of antiwar activism among Black, Latin@, and American Indian sections of the working class, as well as the general antiwar sentiment of the white poor.

Both of these narratives, then, are false. But their falsity is not widely known: in fact, it is censored. This is why Lewis’ and Turse’s interventions are so vital — and why a sustained discussion of such interventions is needed.

The third book, Dirty Wars: The World is a Battlefield by Jeremy Scahill, is cosmopolitan. It has elicited significant coverage, deservedly, and is companioned with a widely praised documentary, which this critic has not seen. It does not attempt to revise a cragged, child-consuming history, rather, it reports on issues of definitive national importance that have heretofore been hidden from view by a powerful network of state and corporate power.

...(more)

_______________________

Paolo Ventura

_______________________

Notation And The Art Of Reading

Karl Young

The idea of notation implies, if not demands, performance. Virtually any form of writing is a kind of notation and any form of reading is a type of performance. Poetry is an intensely physical art, one that activates several senses at once. In aural societies poetry has traditionally been accompanied by facial movement, gesture, manipulation of symbolic objects, the drawing and painting of figures, the wearing of costumes, etc. -- all of which, in a tribal context, are read. Poetry still is a physical art using multiple senses: the body as a whole equals or sometimes replaces the voice in performance art, and even silent readers turn pages, move their heads, their eyes, the roots of their tongues if not their tongues and lips, and so forth.

The kinesthetic link between sight, sound, and speech is mirrored by an inner speech, inner sight, and inner sound. Our thoughts are a combination of inner sight and inner speech. With this inner kinesthesia, we name things as we see them and form images of things about which we hear. Poetry, whether it is heard or seen, stimulates these inner sensations. An Anglo-Saxon warrior listening to a performance of Beowulf in the near darkness of a meadhall would not only be able to see dragons in the flickering coals of the fire, his mind would be filled with images generated by the words he heard. In like manner, a contemporary reader reading silently (provided she or he hasn't been hampered by speedreading practices) will hear an inner voice, which may call up inner sight. A great deal has been written about the "image" in poetry throughout this century. When that term is used it seldom refers to anything that can be seen on the page, but rather the inner vision of the reader.

In the mainstream culture of the western world in the twentieth century, reading becomes an ever more ephemeral, dephysicalized act. At the same time contemporary poets work against this tendency, rediscovering reading methods from other cultures and discovering new ones on their own. Though for most people reading becomes more and more a system of simple data transference, poets attempt to find alternative notations and to expand the range of their performance. In this essay I will give examples of how poetry was read in three cultural contexts removed from ours in culture and time, and then describe some forms of notation in contemporary poetry and how they can be read.

...(more)

night moths

Alfred Kubin

d. August 20, 1959

_______________________

Late August on the Lido

John Hollander

(October 28, 1929 - August 17, 2013)

To lie on these beaches for another summer

Would not become them at all,

And yet the water and her sands will suffer

When, in the fall,

These golden children will be taken from her.

It is not the gold they bring: enough of that

Has shone in the water for ages

And in the bright theater of Venice at their backs;

But the final stages

Of all those afternoons when they played and sat

And waited for a beckoning wind to blow them

Back over the water again

Are scenes most necessary to this ocean.

What actors then

Will play when these disperse from the sand below them?

All this over until, perhaps, next spring;

This last afternoon must be pleasing.

Europe, Europe is over, but they lie here still,

While the wind, increasing,

Sands teeth, sands eyes, sands taste, sands everything.

_______________________

Nets, Waves and Rocks

Joan Eardley

_______________________

The Sea Still Sounds

Salvatore Quasimodo

August 20, 1901 – June 14, 1968

(Già da più notti s’ode ancora il mare)

Even more so at night the sea still sounds,

Lightly, up and down, along the smooth sands.

Echo of an enclosed voice in the mind,

that returns in time; and also that

assiduous lament of the gulls; birds

perhaps of the summits that April

drives towards the plain; already

you are near to me in that voice;

and I wish there might yet come to you

from me, an echo of memory,

like this dark murmur of the sea.

Selected Poems

Salvatore Quasimodo

Translated by A. S. Kline

_______________________

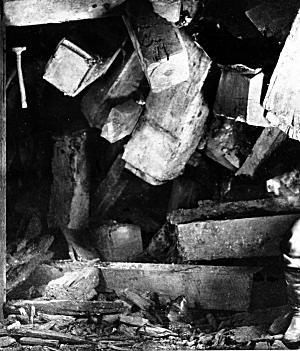

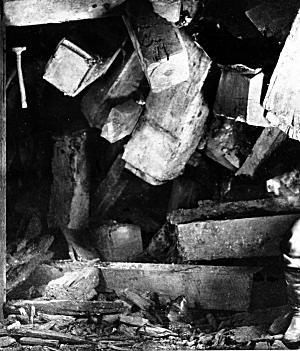

Cave-in at Comstock Mine

Timothy H. O'Sullivan

(1840-1882)

_______________________

The Mad Potter

John Hollander

Now at the turn of the year this coil of clay

Bites its own tail: a New Year starts to choke

On the old one's ragged end. I bite my tongue

As the end of me--of my rope of stuff and nonsense

(The nonsense held, it was the stuff that broke),

Of bones and light, of levity and crime,

Of reddish clay and hope--still bides its time.

Each of my pots is quite unusable,

Even for contemplating as an object

Of gross unuse. In its own mode of being

Useless, though, each of them remains unique,

Subject to nothing, and themselves unseeing,

Stronger by virtue of what makes them weak.

I pound at all my clay. I pound the air.

This senseless lump, slapped into something like

Something, sits bound around by my despair.

For even as the great Creator's free

Hand shapes the forms of life, so--what? This pot,

Unhollowed solid, too full of itself,

Runneth over with incapacity.

I put it with the others on the shelf.

These tiny cups will each provide one sip

Of what's inside them, aphoristic prose

Unwilling, like full arguments, to make

Its points, then join them in extended lines

Like long draughts from the bowl of a deep lake.

The honey of knowledge, like my milky slip,

Firms slowly up against what merely flows

...(more)

John Hollander, Poet at Ease With Intellectualism and Wit, Dies at 83

_______________________

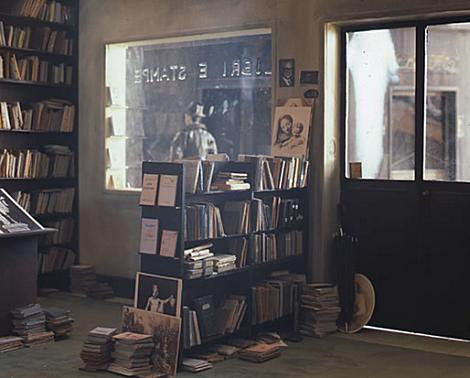

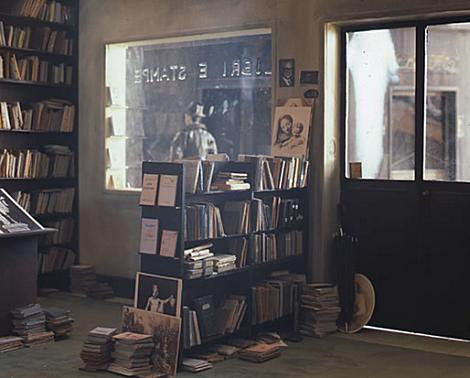

Carl Mydans

1935

_______________________

Salvatore Quasimodo

-in translation by Anny Ballardini

eratio

In Me Lost, Every Form

("In Me Smarrita Ogni Forma")

Another life kept me: solitary

among unknown people; a crust of bread for a gift.

In me is lost every form:

beauty, love—love from which deceit draws

the child, and sadness thereafter.

...(more)

_______________________

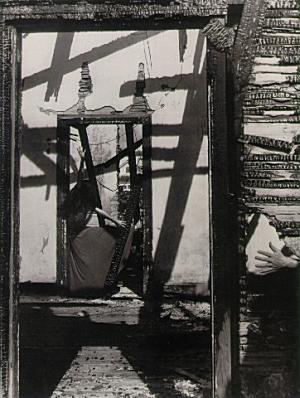

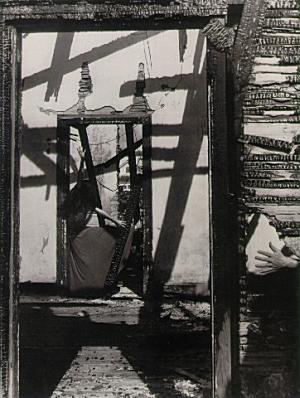

The House of Hysteria

Clarence John Laughlin

1941

_______________________

The Truthy Messiah

Linda Besner

Hazlitt

The now-infamous interview between Fox News’ Lauren Green and author Reza Aslan is a contemporary nine-minute-and-fifty-seven-second Kafka vignette. Watching a journalist argue that knowledge can only be derived from faith against a Master of Divinity arguing that knowledge is a product of empirical research proves what an odd moment we’re at in public intellectual life.

It’s perhaps especially ironic because, like most scholarly works about the historical Jesus, Aslan’s book Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth is also an inquiry into the nature of knowledge. After 2000 years, the question of who can and can’t know what about someone who may or may not have been sent by God is still breaking news. _______________________

Our long march through the institutions is not to reform them, but to transform the common sense they uphold.

Gramsci Comes Home

Spencer Resnick & Jonathan Bix jacobin

(....)

... We publish, we hold panels, we sell newspapers, we put on conferences, we create art. We desperately try to build a left discourse in a hostile environment. This instinct is a reasonable one in an era of neoliberal hegemony where all facets of life are reduced to the market. Meanwhile, our reliance on discourse has obscured the vital understanding that, in order to build a socialist movement, the contradictions of capitalism must be felt and experienced in the fabric of daily life.

As Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward explain, "Workers experience the factory, the speeding rhythm of the assembly line, the foreman, the spies and guards, the owner and the paycheck. They do not experience monopoly capitalism." Homeowners experience the paperwork, the bank manager, the police and the lawyers, the phone calls, the fear of homelessness, and the eviction. They do not experience finance capital, therefore few of them embrace a critique of finance capital. We can only analyze and transform hegemonic ideology through what Antonio Gramsci calls a "war of position." But while we have identified that we are indeed in a war of position, the Left largely fails to grasp what it means to fight that war.

Gramsci understood that challenges to hegemonic ideology must go through common sense — lessons learned, views adopted, and tools employed to make sense of our world — not around it. Constructing a new ideology means transforming the intimate and up-close structures that reproduce the dominant ideology, creating alternatives by building and winning power, and creating leadership in that struggle.

...(more)

Georges Ancely

_______________________

To the Harbormaster

Frank O'Hara

I wanted to be sure to reach you;

though my ship was on the way it got caught

in some moorings. I am always tying up

and then deciding to depart. In storms and

at sunset, with the metallic coils of the tide

around my fathomless arms, I am unable

to understand the forms of my vanity

or I am hard alee with my Polish rudder

in my hand and the sun sinking. To

you I offer my hull and the tattered cordage

of my will. The terrible channels where

the wind drives me against the brown lips

of the reeds are not all behind me. Yet

I trust the sanity of my vessel; and

if it sinks, it may well be in answer

to the reasoning of the eternal voices,

the waves which have kept me from reaching you.

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Time, the deer, is in the wood of Hallaig

an exhibition on forests, history, and social and environmental memory

_______________________

A Weeknight Before the Turn of the Century

Klas Östergren

Translated from the Swedish by Tiina Nunnally

words without borders

(....)

Access to a language is no guarantee of spiritual well-being. Words are unreliable; they can alternately heal and tear apart. For the person who takes words seriously, the manipulation of them is often filled with anguish and the strain associated with stressful decision-making situations. An author is constantly forced to make minor emergency landings in his language; words fail, thoughts don't take off. The normal state is a quiet panic. It's possible that words release a chemical substance, a type of adrenaline not known until now, a substance that causes harm when it's released in large quantities and assumes too high a concentration in the body. A toxin belonging to a specific syntax. An addictive illusion of freedom. It's not insignificant when someone sits in judgment over writers, or decides to admire them. Writers probably should be neither judged nor admired. That was actually where I was heading all along. Toward a reasonable expectation.

...(more)

_______________________

salmon nets

Joan Eardley

1921 – 1963)

_______________________

Five poems

Camille Martin

Doppelgänger’s Lament

Continuous coverage of already-solved swindles

is how your story goes down. At intervals, hype

jingles with the faux naiveté of felons at large.

Secretly you yearn to be in the midst of a true-life

crime story with its McGuffins, its quest

for hollow penguins hidden in plain sight

to lead the gumshoe astray. You ditch the fantasy

and live a pretty normal life, occasionally saving the day

with cartoonish light bulbs switching on with impeccable

timing, viewing creation from a precisely-gauged periphery,

clock ticking and stopping and ticking. No plugging

the drain, scraping ancestral facades. And if you could,

maybe you’d rather peer at a blank wall, inwardly filming

all the could-have-beens teeming before your eyes.

A life of unbroken crime.

...(more)

On Barcelona

Camille Martin at EPC and PennSound

Camille's blog - Rogue Embryo

_______________________

Fishing for zoologist Henri de Lacaze-Duthiers

1883

Georges Ancely

_______________________

Colloquium » Issue 2

“Alternations of Light and Shade”: Spectroscopy and The Woman in White

Jonathan Baker

In an eerie passage in The Woman in White, Wilkie Collins describes a daytrip to the lakeshore, giving particular attention to the effect that the peculiar light lends to the scene. Collins notes that “the rapid alternations of shadow and sunlight over the waste of the lake, made the view look doubly weird and gloomy” (203). As we shall see, due to recently popularized technological innovations, the words “alternations,” “shadow,” “sunlight,” “view,” and “doubly” might have resonated differently with the Victorian reader than the reader of today. Scholars such as Robert J. Silverman have detailed the importance of stereoscopes in mid-nineteenth century English life, but the relationship between stereoscopy and Victorian fiction has rarely been addressed. The popular technology of stereoscopy brought about new questions about the nature of vision and eyesight in Victorian England, and the debates instigated by these questions appear even in a text as seemingly unconcerned with contemporary science as Collins’ novel of adventure and intrigue.

...(more)

_______________________

Too much information

Our instincts for privacy evolved in tribal societies where walls didn't exist. No wonder we are hopeless oversharers

Ian Leslie

aeon

Edward Snowden’s revelations about the panoptic scope of government surveillance have raised the hoary spectre of ‘Big Brother’. But what Prism’s fancy PowerPoint decks and self-aggrandising logo suggest to me is not so much an implacable, omniscient overseer as a bunch of suits in shabby cubicles trying to persuade each other they’re still relevant. After all, there’s little need for state surveillance when we’re doing such a good job of spying on ourselves. Big Brother isn’t watching us; he’s taking selfies and posting them on Instagram like everyone else. And he probably hasn’t given a second thought to what might happen to that picture of him posing with a joint.

...(more)

_______________________

Fencing Off Ideas: [pdf]

Enclosure and the Disappearance of the Public Domain

James Boyle

(....)

Sir Thomas More went further, though he used sheep rather than geese to make his point. He argued that enclosure was not merely unjust in itself, but harmful in its consequences. It was a cause of economic inequality, crime, and social dislocation.

Your sheep that were wont to be so meek and tame, and so small eaters, now, as I hear say, be become so great devourers and so wild, that they eat up, and swallow down the very men themselves. They consume, destroy, and devour whole fields, houses, and cities. For look in what parts of the realm doth grow the finest and therefore dearest wool, there noblemen and gentlemen...leave no ground for tillage, they enclose all into pastures; they throw down houses; they pluck down towns, and leave nothing standing, but only the church to be made a sheep-house. ... Therefore that one covetous and insatiable cormorant and very plague of his native country may compass about and enclose many thousand acres of ground together within one pale or hedge, the husbandmen be thrust out of their own.

The enclosure movement continues to draw our attention. It offers irresistible ironies about the two-edged sword of "respect for property" and lessons about the role of the state in making controversial, policy-laden decisions to define property rights in ways that subsequently come to seem both natural and neutral.

_______________________

Georges Ancely

|