|

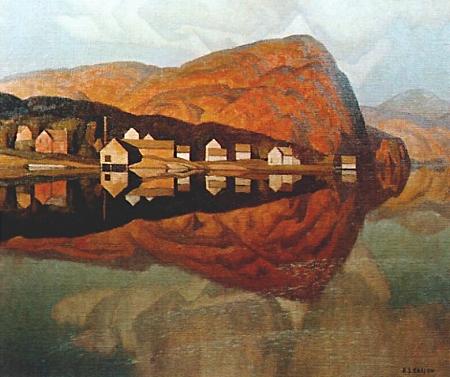

Spring

1933

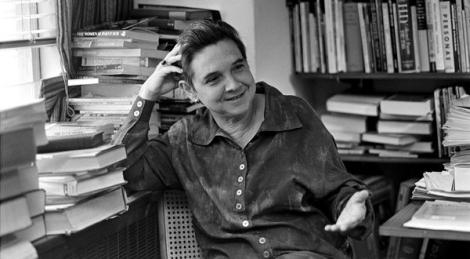

Mikhail Vasilyevich Nesterov

b. May 21, 1862

_______________________

Looking Across the Fields and Watching the Birds Fly

Wallace Stevens

Among the more irritating minor ideas

Of Mr. Homburg during his visits home

To Concord, at the edge of things, was this:

To think away the grass, the trees, the clouds,

Not to transform them into other things,

Is only what the sun does every day,

Until we say to ourselves that there may be

A pensive nature, a mechanical

And slightly detestable operandum, free

From man's ghost, larger and yet a little like,

Without his literature and without his gods . . .

No doubt we live beyond ourselves in air,

In an element that does not do for us,

so well, that which we do for ourselves, too big,

A thing not planned for imagery or belief,

Not one of the masculine myths we used to make,

A transparency through which the swallow weaves,

Without any form or any sense of form,

What we know in what we see, what we feel in what

We hear, what we are, beyond mystic disputation,

In the tumult of integrations out of the sky,

And what we think, a breathing like the wind,

A moving part of a motion, a discovery

Part of a discovery, a change part of a change,

A sharing of color and being part of it.

The afternoon is visibly a source,

Too wide, too irised, to be more than calm,

Too much like thinking to be less than thought,

Obscurest parent, obscurest patriarch,

A daily majesty of meditation,

That comes and goes in silences of its own.

We think, then as the sun shines or does not.

We think as wind skitters on a pond in a field

Or we put mantles on our words because

The same wind, rising and rising, makes a sound

Like the last muting of winter as it ends.

A new scholar replacing an older one reflects

A moment on this fantasia. He seeks

For a human that can be accounted for.

The spirit comes from the body of the world,

Or so Mr. Homburg thought: the body of a world

Whose blunt laws make an affectation of mind,

The mannerism of nature caught in a glass

And there become a spirit's mannerism,

A glass aswarm with things going as far as they can.

_______________________

(Accouche! Accouchez!

Will you rot your own fruit in yourself there?

Will you squat and stifle there?)

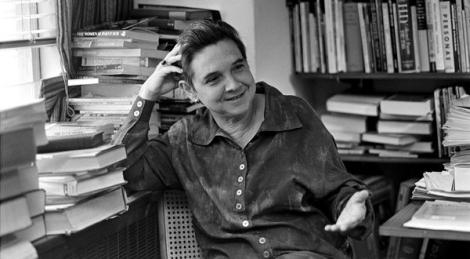

Walt Whitman

May 31, 1819 - March 26, 1892

photo - Thomas Eakins

1891

Carol of Words

Walt Whitman

EARTH, round, rolling, compact—suns, moons,

animals—all these are words to be said;

Watery, vegetable, sauroid advances—beings,

premonitions, lispings of the future,

Behold! these are vast words to be said.

Were you thinking that those were the

words—those upright lines? those curves, angles,

dots?

No, those are not the words—the substantial

words are in the ground and sea,

They are in the air—they are in you.

Were you thinking that those were the

words—those delicious sounds out of your friends’

mouths?

No, the real words are more delicious than they.

Human bodies are words, myriads of words;

In the best poems re-appears the body, man’s or

woman’s, well-shaped, natural, gay,

Every part able, active, receptive, without shame or

the need of shame.

...(more)

Leaves of Grass

Walt Whitman

_______________________

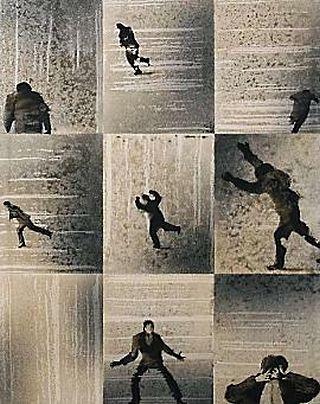

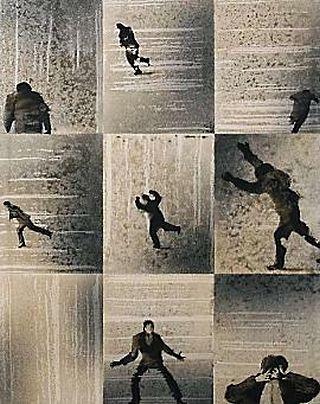

Madeja

2010

Juan Genovés

b. May 31, 1930

_______________________

No Words Can Describe It

Mark Strand

How those fires burned that are no longer, how the weather worsened, how the shadow of the seagull vanished without a trace. Was it the end of a season, the end of a life? Was it so long ago it seems it might never have been? What is it in us that lives in the past and longs for the future, or lives in the future and longs for the past? And what does it matter when light enters the room where a child sleeps and the waking mother, opening her eyes, wishes more than anything to be unwakened by what she cannot name?

Mark Strand at the Poetry Foundation

via

_______________________

Hombre Solo

Juan Genovés

1967

_______________________

No one can tell

Poems from Ahava (WSOY, 1998)

Lauri Otonkoski

Translated by Herbert Lomas

And life went on, went on as a kind of weird fugue,

a forked path that drops across your eyes,

rejecting simple questions.

Which summer was that,

I ask in December,

in a high room, with a tiled stove, a bricked up

nostalgic sentence about the warmth of other times,

a crossing where all the world's words

discover the the comparative degree of silence,

the one with meaning.

Should I peep across a couple of cloudy stanzas to get a better view,

but again my eye conjures up a medieval constricted soul.

All that's left is a thirst of all the senses, a frigid study of sentences,

of bones.

Yes, even if speech

is like trying to master a hundred-string guitar with ten fingers.

Even if stories

masked in words are no longer enough

for a time drowned in virtual dreams.

Even though, day and night,

the same perpetual dusk drifts a continent of ice over the city.

Nevertheless

I do think of something, with clenched hands,

when I come to the edge of the park.

That park is just a slice of the city,

humming nostalgia for the forest.

...(more)

Books from Finland archive_______________________

Tom Waits: A Day in Vienna

Tom Waits Sings and Tells Stories

a half-hour Austrian TV film shot on April 19, 1979

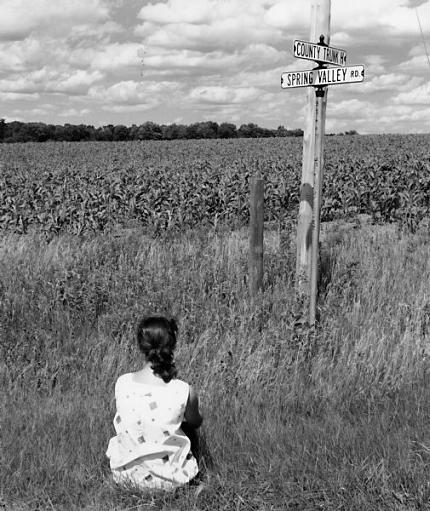

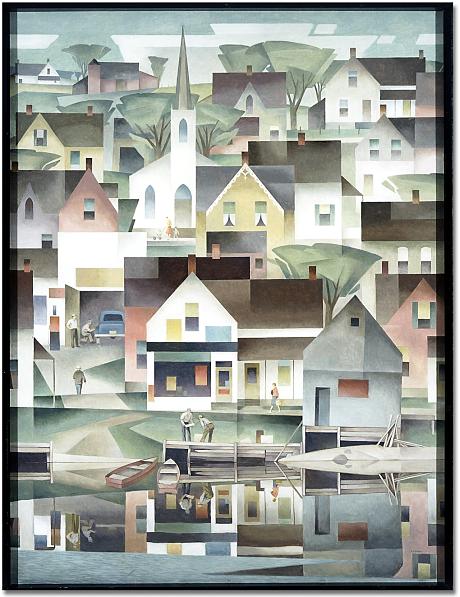

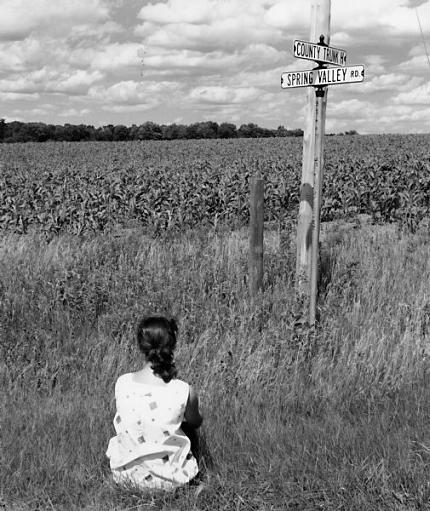

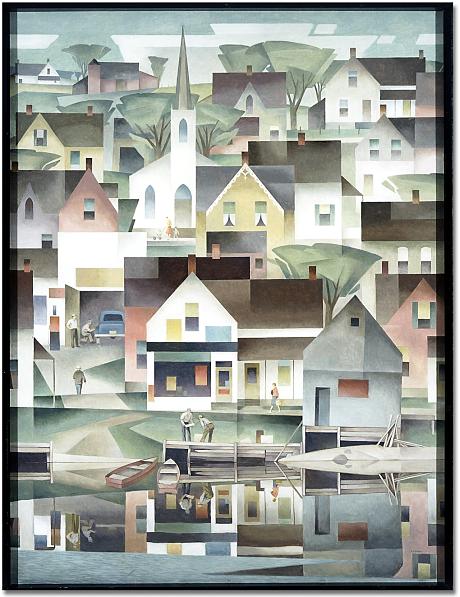

Spring Valley Road

1959

Spirit of Rural Wisconsin

Jim Widmer

via

_______________________

The Essayification of Everything

Christy Wampole

(....)

It seems that, even in the proliferation of new forms of writing and communication before us, the essay has become a talisman of our times. What is behind our attraction to it? Is it the essay’s therapeutic properties? Because it brings miniature joys to its writer and its reader? Because it is small enough to fit in our pocket, portable like our own experiences?

I believe that the essay owes its longevity today mainly to this fact: the genre and its spirit provide an alternative to the dogmatic thinking that dominates much of social and political life in contemporary America. In fact, I would advocate a conscious and more reflective deployment of the essay’s spirit in all aspects of life as a resistance against the zealous closed-endedness of the rigid mind. I’ll call this deployment “the essayification of everything.”

(....)

What is perhaps most interesting about the essay is what happens when it cannot be contained by its generic borders, leaking outside the short prose form into other formats such as the essayistic novel, the essay-film, the photo-essay, and life itself. In his unfinished novel “The Man Without Qualities,” the early 20th-century Austrian writer Robert Musil coined a term for this leakage. He called it “essayism” (Essayismus in German) and he called those who live by it “possibilitarians” (Möglichkeitsmenschen). This mode is defined by contingency and trying things out digressively, following this or that forking path, feeling around life without a specific ambition: not for discovery’s sake, not for conquest’s sake, not for proof’s sake, but simply for the sake of trying.

(....)

Essayism, as an expressive mode and as a way of life, accommodates our insecurities, our self-absorption, our simple pleasures, our unnerving questions and the need to compare and share our experiences with other humans. I would argue that the weakest component in today’s nontextual essayism is its meditative deficiency. Without the meditative aspect, essayism tends toward empty egotism and an unwillingness or incapacity to commit, a timid deferral of the moment of choice. Our often unreflective quickness means that little time is spent interrogating things we’ve touched upon. The experiences are simply had and then abandoned. The true essayist prefers a more cumulative approach; nothing is ever really left behind, only put aside temporarily until her digressive mind summons it up again, turning it this way and that in a different light, seeing what sense it makes. She offers a model of humanism that isn’t about profit or progress and does not propose a solution to life but rather puts endless questions to it.

...(more)

_______________________

Black Coffee

PBS

The Irresistible Bean

Gold in Your Cup

The Perfect Cup

.....................................................

Coffee Cantata

JS Bach

1732 - 1735

Libretto by Christian Friedrich Henrici

Be quiet, stop chattering,

and pay attention to what's taking place:

(....)

Lieschen Father, don't be so severe!

If I can't drink

my bowl of coffee three times daily,

then in my torment I will shrivel up

like a piece of roast goat.

Aria Lieschen

Mm! how sweet the coffee tastes,

more delicious than a thousand kisses,

mellower than muscatel wine.

Coffee, coffee I must have,

and if someone wishes to give me a treat,

ah, then pour me out some coffee!

...(more)

.....................................................

The Lincoln Coffee Lounge

photographed by Brian Bird

1948-1951

State Library of New South Wales

_______________________

from The Story of My Accident is Ours

Rachel Levitsky

presented at lemon hound

(....)

The trajectories set forth by such constraints, of suffering and the bloated plots to do away with suffering, for indecipherable, multiply gendered bodies, does not differ structurally from that which has been set for colonized bodies brought into The State originally from afar. The only difference is the one which is most articulated and most silenced—that occasionally a star possessing brilliance enough to be able to operate all the cultural and class systems at once does come along and this star has the force to cause the whole thing (on its very own terms) to rumble, at least quiver. Such a rattling has at times produced an amnesty in which doors open and a few others of us are able to rush in, or out, but for most of us, there is an ever denser charge—an injunction to buy our way out of our predicament by signing onto an ideology the best of us oppose vehemently and toward which the worst of us are ambivalent. We are led to believe and we convince ourselves this point of purchase is some minor detail, that if we know we don’t mean what we say then it will not materialize although here we fidget more restlessly even than our usual, we shuffle where we stand, nervous, suspecting, nearly knowing what we already do—that speech and knowledge are convolutes and cannot be any other way, that words, spoken or written, make it matter—each one having some sort of impact if not ‘meaning’ so to speak, despite ambiguity, complexity, politesse, magic tricks, good humor and the weather. Black, White and Left, Right can each mean many things so we are warned to not define these things narrowly or generally, to be particularly conscious when using these apparently basic even banal words for wouldn’t we all agree, black is a word that means dark and white was a word that means light and that dark is understood to be under, feared like a basement or as a place to hide, like in a thick forest or a blanket, and light is received as a place of hope and exposure, levity and wisp.

...(more)

_______________________

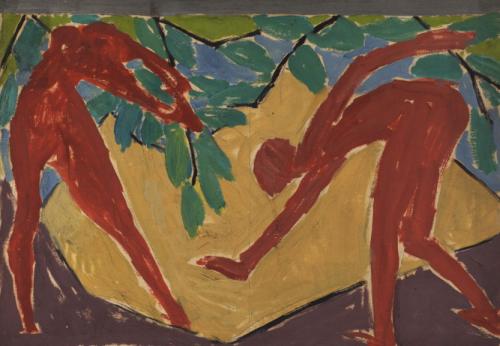

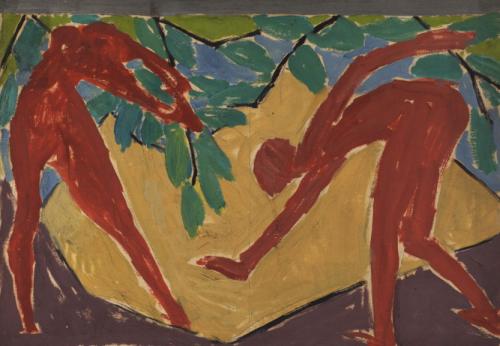

Adam and Eve

1913-1914

Vanessa Bell

b. May 30, 1879

_______________________

Towards a Poetics of the Phatic (Part 1)

K. Silem Mohammad

(....)

Although poetry has been exploring the resources of the phatic now for decades, there has been relatively little coherent and expansive development of a critical tradition informed by its principles. Most criticism of contemporary poetry (even experimental poetry) still works squarely within the parameters of the mimetic, pragmatic, objective, and even expressive orientations identified by Abrams (or at the metalingual and paracritical level of bibliographical and definitional scholarship). At times the anachronism of this situation is palpable, especially when styles of close reading lifted whole from New Critical practice are applied to texts that clearly resist the logic of organic unity and formalist autonomy inherent in such approaches. Similarly, much criticism tends to assume a mimetic aesthetic in work that wields such effects, if at all, in ironic or otherwise negational modes, or to assume emotive priority in cases where such priority is demonstrably qualified by phatic maneuvers. The pragmatic critical tradition perhaps retains a higher degree of applicability to contemporary poetic practice, as it is arguable that one goal of the phatic is the establishment of a strong bond with given readerly communities who recognize its codes, but here as well there persists an investment in naļve and outdated models of poetry’s “relevance” to social and political themes.

What would a phatic-oriented critical tradition look like? What texts would be most amenable to being viewed through the lens of the phatic, and how, in turn, would theory synthesize the sum of these viewings into a coherent poetics? What would be its incentive, its purpose, its relevance? In my next post, I’ll examine these questions further.

...(more)

(Part 2)

_______________________

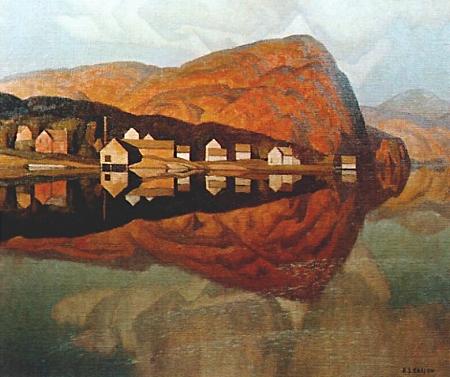

Pier on the Rock River

Jim Widmer

1947

_______________________

Hopkins’s Wound

Sean Sheehan

(....)

No one today could refute the fact that people have been wounded by the Catholic Church - the consequences of the hurt done to Hopkins palls in the light of recent revelations about abuse by priests – but there is also the question whether people can be hurt by the belief system of Roman Catholicism: an issue of theology rather than of an institution. The griefwork of Hopkins’s final sonnets is not the result of an editor’s former discouragement, and the strain of too scrupulously teaching at University College Dublin and marking hundreds of examination papers for the Royal University of Ireland can be only be a contributing factor in Hopkins’s despair. Nor can one fall back on casual racism, as Norman MacKenzie does in Excursions in Hopkins (2008): “a sensitive Englishman trying to deal with immature Irish classes and a hostile political climate”. A poem like “Spelt from Sybil’s Leaves”, begun in 1884 when the Jesuits moved Hopkins to Dublin but not finished until two years later when he returned to the poem, reveals a mind tormented by thoughts of the day of judgement:

Now her áll in twó flocks, twó folds—black, white; / right,

wrong: reckon but, reck but, mind

But these two; ware of a world where but these / twó tell, each

off the other; of a rack

Where, selfwrung, selfstrung, sheathe- and shelterless, / thoughts

agaínst thoughts ín groans grínd

The marks for stress and pauses are Hopkins’s, serving to drum home the self-lacerating pain of someone who, feeling that earth’s “being has unbound; her dapple is at end”, lays anguished at the thought that all that was varied and plural is summarily reduced to a binary and bleak opposition. This is Catholic fundamentalism of a Taliban kind, heard in the relentless repletion of “two” and “but” and the frightening finality that comes close to outlawing words of more than one syllable.

...(more)

_______________________

Bandlow's Woods

Jim Widmer

1949

wind farm

photo - mw

_______________________

e-flux #45 May 2013

Language and Internet

Editorial

Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood, Anton Vidokle

(....)

As the role of the state in ensuring the value of currency has grown weaker over the past few decades, markets have increasingly assumed the qualities of language, of a “system of signs in which the only essential thing is the union of meanings” (Saussure). The other language economy is of course the internet, where it was thought that the immaterial qualities of language would evade limits in supply and demand. But now for some reason, this promise reverses. As language becomes more free, everything else becomes incredibly expensive. This has made language, and the internet with it, a class battleground now more than ever, because it represents access to both knowledge and capital simultaneously.

Market collapses have only made it more clear that the money system follows a recursive structure where value is not absolutely backed but mutually reinforced. And for those whose livelihoods depend on the integrity of the financial system, or even the state for that matter, this has produced a deep existential crisis. How can we be governed by recursive logics and swells of belief and disbelief, by speech acts and depressive episodes? Could my fortunes be pegged to nothing more than just this? Artists will tell you: of course. Because that is how the art system has always functioned. It has always been pegged to language.

...(more)

After the Social Media Hype: Dealing with Information OverloadGeert Lovink

_______________________

The Fibreculture Journal 20

Networked Utopias and Speculative Futures.

_______________________

Gilbert Simondon: Being and Technology

Edited by Arne De Boever, Alex Murray,

Jon Roffe and Ashley Woodward

google books

Gilbert Simondon: Being and Technology is the first book in English dedicated entirely to the work of this French philosopher. Although the importance of Simondon’s thought for twentieth- and twenty- first-century continental philosophy is clear – his work is foundational for Gilles Deleuze and Bernard Stiegler, and resonates in the writings of other prominent thinkers, such as Jean Baudrillard, Paolo Virno, Giorgio Agamben and Roberto Esposito – relatively little attention has been paid to Simondon in the English-speaking academy. The few scholars writing about Simondon in English who have contributed to this collection – Brian Massumi, Elizabeth Grosz and Miguel de Beistegui, amongst others – are, next to some philosophers not included here (Alberto Toscano, Bruno Latour and Isabelle Stengers for example), the exceptions that confirm the rule.

pdf available at Monoskop

_______________________

Telegraph wire going up

for No Man's Land

John Warwick Brooke

National Library of Scotland

_______________________

The Future of the Commons - Beyond Market Failure and Government Regulation

Elinor Ostrom, Christina Chang, Mark Pennington, and Vlad Tarko

_______________________

‘Thought as Practice’

second of a two part interview with Colin Wright, author of Badiou in Jamaica: The Politics of Conflict

(....)

I don’t think there is a single, simple ‘Badiou’ who can be, let alone needs to be, defended. As you can tell from the way I have explained my book, it emerged from a complex sense that there are some very good and important things in Badiou’s work, but also some problems and limitations. I think this is bound to be true of any theory or philosophy, dream as we might of a simple, unchanging solution for all our ills. Nonetheless, I don’t find concepts like the ‘subject’, the ‘event’ or ‘ideas’ fantastical at all, and I am certainly not pompous enough to suggest that he is not justified in developing them.

Badiou’s work certainly comes out of a particular context that shapes it. This would include his involvement in French Maoism, May ’68, the post-Maoist group organisation politique, and the backdrop of the ups and downs of parliamentary politics in France. If we are looking for ‘justification’, I think that personal history of political activism counts for something. There is also the intimately connected intellectual history that he has lived through: first Sartre’s then Althusser’s version of Marxism, Lacanian psychoanalysis and the Cahiers pour analyse project, so-called ‘deconstruction’, the rise of the ‘new philosophers’ in France and so on. He is therefore also ‘justified’ by his participation, but also singular path through, those intellectual movements. In a way that I find very admirable, Badiou held fast to his militancy even in what he calls the ‘desert years’ of the 1980s, when his work was deeply, deeply unfashionable. More than mere stubbornness though, Badiou has genuinely managed to shift the co-ordinates of philosophical and theoretical debates today to bring them into much greater proximity with activism.

(....)

I don’t necessarily believe that people involved in radical politics must read Badiou, as if what he offers is some kind of straightforward manual for activism. It’s not that simple. An implication of his own theory of the subject is that such a subject by no means waits on some kind of recognized ‘theoretical’ justification for what they do. An event does not need to be called an ‘event’ by some kind of philosophical commentator to get underway. However, having some understanding of the generic logic of events does enable one, I would argue, both to recognize when one might be underway - and thus all the myriad strategies by means of which the state, broadly conceived, attempts to erase it and its potential consequences - and just as crucially, to recognize when pseudo-events are being constructed by a state in order to justify reactionary forms of politics.

...(more)

part 1, ‘Another World is Possible’.

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Richard Seymour on the rise of a new left in Europe

... we hear that however weak we are, the ruling class is also weak. In some respects they are. Ideologically, the traditional parliamentary parties are weak, and the traditional sources of authority are diminishing. The dominant conservative and social-democratic forces are degenerating. But the ruling class's control over markets, its colonisation of all the major state apparatuses, its command of the dominant institutions, the dominant media, the academic and ideological mainstream, and so on, stands in stark contrast to the left's paucity of infrastructure, its lack of institutional advantage, its disarray, its dumbfounded attempts at analysis, the disorganised state of the working class underpinning it, the morbid symptoms arising from the secular decline of social democracy and the trade unions.

There's a tendency to enthuse about various substitutions -- social media will make up for our lack of an infrastructure, forgetting that its "individuating", commodifying tendencies pose as many problems as are solved by the creative autonomy facilitated by social media; or, we suppose that a new class of degraded subjects, the urban poor in the US, the graduates with no future in the Middle East and Europe, or relatedly the "precariat", will make up for the degeneration of the organised working class; or, as mentioned above, the weakness of our opponents will make up for our weakness and give us a more level playing field. I think all of this is dangerously complacent and delusional.

I don't think the answer to this crisis is simply to bet on more "resistance" "kicking off". It isn't kicking off everywhere There's a real problem here. We should expect as materialists that a crisis of capitalism would also be a crisis of the left. Insofar as we have built up our patterns of self-reproduction in the existing spaces of capitalism -- say in student politics, the public sector, manufacturing workers, etc. -- a crisis necessarily threatens to erode the bases for our ongoing existence.

We have to find a new way to develop if we are even to continue to exist. Eventually, this crisis is going to be resolved in some way -- probably to the massive disadvantage of workers and the left. The pieces of the kaleidoscope will fall into place, as it were. What is then left is quite plausibly what we will have to work with for a generation or so.

So what we do now, counts for a lot. And we have found ourselves torn between inertia and hyperactivism, the latter often covering up for the former, while basically getting nowhere. This is not to say that none of what we have done is worthwhile -- it is to say that we have been impeded by old catechisms and fetishes that prevent us from seeing what is new.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

George Quasha: from “Speaking Animate” (preverbs)

with a note on the poetics of preverbs

Jerome Rothenberg

1 words under pressure bleed original sense

The trouble with paradise is you never want to be away from home.

I make what calls me out.

All gone before you know it.

Words may drop passing color yet seeing you here now are born again, and again.

Closing a word in the mouth feels the sound until the tongue can’t stay still.

To unmask is to go silent.

Language makes no promise to communicate.

An articulated sound has it own dream in the ear.

Her presence in the room gives aroma to the syllables I voice.

Now she’s ready to draw eros from foreign bodies.

It starts by focusing on the sounds beyond hearing, still felt.

By she I mean who speaking animate configures.

This is the time of alternative obscurities to see through.

Through thoroughly, as a word weighs.

...(more)

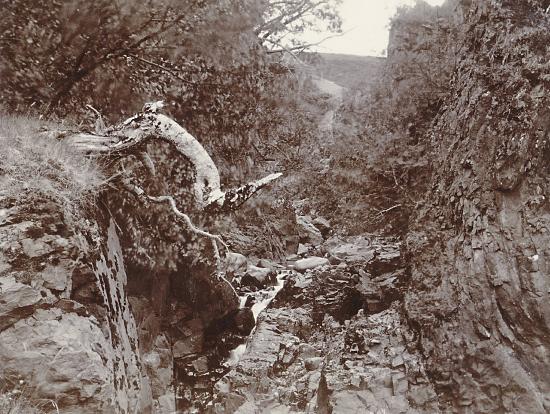

Woods

west of Öręfajökull, near Svķnafell

Frederick W.W. Howell

ca. 1900

Cornell University Library

_______________________

Sjón, Björk, and the Furry Trout

David Bukszpan

Paris Review

When Icelanders talk to Americans about Iceland, sooner or later talk is going to turn to fairies, or hidden people, or elves. And while it seems many Icelanders do truly believe in those things, often you’ll get a response like the novelist Sjón gave Leonard Lopate the other day: “If you actually lean on an Icelander, most of us will confess to believing that nature has the power to manifest itself in a form understandable to humans. So the hidden people, you know, we would say, ‘Well of course I don’t believe that there are actually cities inside our mountains, but it’s possible that nature has a way of manifesting itself in a human form to, you know, have an interaction with the humans.’”

Similarly, when Americans talk about Iceland, sooner or later (probably sooner) we’re going to start talking about one specific fairy, or hidden person, or elf. And despite my not having any photos or videos to back it up, you’ll have to believe me that last week at Scandinavia House, the sprite-like Reykjaviker you’re thinking of did indeed manifest herself in a striking, stiff, white-and-purple dress for a ten-minute interaction with book-reading humans on behalf of her longtime friend and collaborator Sjón.

...(more)

Sjonorama

_______________________

Three poems

Sjón

the stone collector’s song

translation by David McDuff

(....)

here it is you said comfortingly

your stone collection

it isn’t

lost

in the shelves behind the bar

waits the iceland spar

all my

stones

brimstone – pyrite – opal

and jasper – dear friends!

none of you have i

forgotten

and up there on the ceiling hang

the obsidian sacks

heavy with

anxiety

...(more)

Words without Borders — October 2011: Writing from Iceland

_______________________

Sjón, From the Mouth of the Whale

Justin E H Smith reviews Rökkurbzsnir or 'Marvels of Twilight'

This novel is an important contribution to Icelandic literature. It channels the past millennium's experience of nature and history in that peculiar place, but does not aspire to mere peculiarity. For this reason, it is a great shame that the book has been packaged for foreigners as a sort of offshoot of Björkian quirkiness.

_______________________

Iceland 1

Pascal Fellonneau

_______________________

Cadence, Country, Silence: Writing In Colonial Space

Dennis Lee

(....)

What does cadence feel like?

Imagine you're sitting indoors. Down in the basement, a group with a heavily amplified bass is rehearsing. Nothing is audible, but the pulsating of the bass starts to make the girders and beams vibrate. And eventually the vibration makes its way into your body. You feel yourself being flexed by a tremor which you're bound to acknowledge, whether or not you know what it is.

That sensation is disorienting, because it collapses our familiar categories of inner and outer, subject and object. You don't perceive a vibration; you vibrate. Your muscular system has become both the recording instrument and the thing recorded. And the pulse you feel is neither subjective nor objective. Rather, it is your immediate portion of the kinaesthetic space in which you exist.

During my twenties, I became aware of something comparable. It was not my body that was being flexed, or not primarily. It was my — what do I say? My imagination? my psyche? my spirit? I don't know the right term, but the experience was unmistakable. I was imbedded, as plainly as I was in the earth's atmosphere, in a space which was alive and volatile, and whose flexions governed the tension and pulse of my system. If I sat quietly, I would regularly become aware of this preverbal field of force.

That didn't jibe with anything I knew, but eventually it was too immediate to deny. The term I seized on for the insistent tremor was "cadence." And cadence — the direct experience of that energy, not my ideas about it — has shaped my writing since shortly after my first book appeared.

It had no specific content, or none to begin with. It was its own content, a rich symphony of clench and swooping pulsation. Nor could I get any conceptual distance on it; the resources with which I might have analyzed it were already being tweaked and yo-yoed themselves. Often I went for weeks with no apprehension of the process, which nonetheless felt as if it continued its delicate judder and carom and chug without me. And my writing vocation was given. A poem was meant to enact what cadence had been doing all along. Not by describing it, but by reliving its muscular trajectories in words.

...(more)

_______________________

The Curious Persistence of Blasphemy: Canada and Beyond

Jeremy Patrick

Abstract:

The purpose of this dissertation is to examine the history and future of the crime of blasphemy. In the introduction, several key questions are examined: (1) What is blasphemy? (2) Why do people blaspheme? and (3) What are the real or perceived harms of blasphemy? Subsequently, Part I examines the history of blasphemy and blasphemy-like laws in six jurisdictions around the globe: England, Ireland, Australia, Pakistan, the United Nations, and the United States. The jurisdictions chosen illuminate the fact that blasphemy is a complex concept which can be regulated in a wide variety of ways. These six provide an excellent picture of the varied and diverse ways the concept of blasphemy has operated and an understanding as to why it remains relevant today. Part II of this dissertation turns away from a global, comparative examination of blasphemy and instead provides a comprehensive, in-depth study of a single jurisdiction: Canada. This sustained history of blasphemy in Canada, the first ever published, allows for a valuable snapshot of the evolution of the crime into its modern form. Part III synthesizes the research and analysis in Parts I and II to answer the fundamental questions: what is the future of the crime of blasphemy in Canada and beyond?

...(more)

_______________________

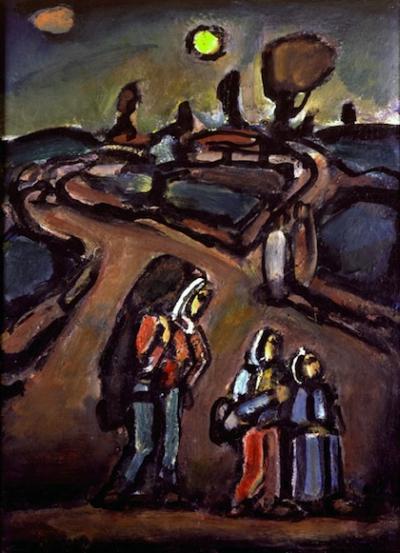

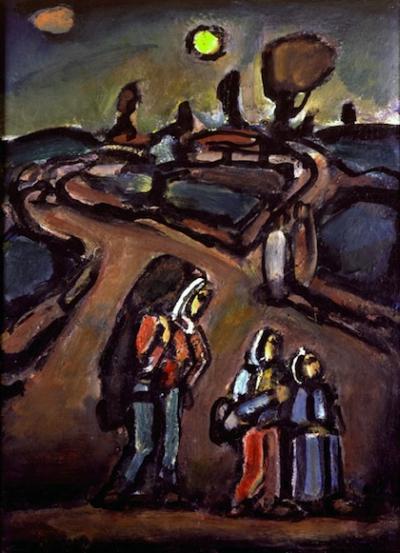

Georges Rouault

b. May 27, 1871

_______________________

Does writing have a future?

Mark Kingwell

(....)

McLuhan himself could be bold, sometimes wacky on the subject of reading. “As an extension of man,” he said in a 1969 interview with Playboy magazine, the typeset codex-style book “was directly responsible for the rise of such disparate phenomena as nationalism, the Reformation, the assembly line and its offspring, the Industrial Revolution, the whole concept of causality, Cartesian and Newtonian concepts of the universe, perspective in art, narrative chronology in literature, and a psychological mode of introspection or inner direction that greatly intensified the tendencies toward individualism and specialization.”

That is all good fun, after its fashion — though it does raise the awkward question of which features of the modern world were not spawned by movable type. Hoop skirts? Wigs for gentlemen? Monster truck rallies? Ambient techno?

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger analyzes the question concerning technology with both more wisdom and more prescience. The task is not to understand the function of this or that tool, he argues, but rather to examine the way technology comes to dominate every aspect of existence. This enframing, as Heidegger calls it, which places everything within the ambit of possible use and disposal, is the real meaning of technology.

You could not hope to find a clearer example of this than the current debate about the future of reading. The first task, then, is to recognize how we ourselves are enframed. As long as we continue to think about reading in the context of technology, we will fail to see any deeper meanings, including the possible effects of our own self-imprisonment.

...(more)

_______________________

Persimmons Cockatoos

Jessie Arms Botke

b. May 27, 1883

_______________________

Click

John Barth

b. May 27, 1930

The Atlantic Monthly, December 1997

CLICK?" So (sans question mark) reads the computer monitor when, in time, "Fred" and "Irma" haul themselves out of bed, wash up a bit, slip back into their undies, and -- still nuzzling, patting, chuckling, sighing -- go to check their E-mail on Fred's already booted-up machine. Just that single uppercase imperative verb or sound-noun floating midscreen, where normally the desktop would appear, with its icons of their several files: HERS, HIS, SYSTEM, APPLICATIONS, FINANCES, HOUSE STUFF, INTERNET, and ETC (their catchall file). Surprised Irma, having pressed a key to disperse the screen-saver program and repeated aloud the word that oddly then appeared, calls Fred over to check it out, but the house cybercoach is as puzzled thereby as she. Since the thing's onscreen, however, and framed in a bordered box, they take it to be a command or an invitation -- anyhow an option button, like SAVE or CANCEL, not merely the name of the sound that their computer mouse makes when ... well, when clicked.

(...)

The Marquise Went Out at Five (La Marquise sortit ą cinq heures) is the title of a 1961 novel by the French writer Claude Mauriac and a refrain in the Chilean novelist José Donoso's 1984 opus Casa de Campo (A House in the Country). The line comes from the French poet and critic Paul Valéry, who remarked in effect that he could never write a novel because of the arbitrariness, the vertiginous contingency, of such a "prosaic" but inescapable opening line as, say, "The Marquise went out at five" -- for the rigorous M. Valéry, a paralyzing toe-dip into what might be called the hypertextuality of everyday life.

(...)

Not too fast there, Mark. Not too slow there, Val. That's got it, guys; that's got it ... (so "CNG" [= I/you/eachandallofus] encourages them from the hyperspatial wings, until agile Valerie lifts one [long] [lithe] [cinnamon-tan] leg up and with her [left] [great] toe gives the Mac's master switch a .............(more)

_______________________

The grave of Strokkur

(Haukadalur)

Frederick W.W. Howell

ca. 1900

Cornell University Library

_______________________

The Social Media Contradiction: Data Mining and Digital Death

Tama Leaver

Introduction

Many social media tools and services are free to use. This fact often leads users to the mistaken presumption that the associated data generated whilst utilising these tools and services is without value. Users often focus on the social and presumed ephemeral nature of communication – imagining something that happens but then has no further record or value, akin to a telephone call – while corporations behind these tools tend to focus on the media side, the lasting value of these traces which can be combined, mined and analysed for new insight and revenue generation. This paper seeks to explore this social media contradiction in two ways. Firstly, a cursory examination of Google and Facebook will demonstrate how data mining and analysis are core practices for these corporate giants, central to their functioning, development and expansion. Yet the public rhetoric of these companies is not about the exchange of personal information for services, but rather the more utopian notions of organising the world’s information, or bringing everyone together through sharing.

The second section of this paper examines some of the core ramifications of death in terms of social media, asking what happens when a user suddenly exists only as recorded media fragments, at least in digital terms. Death, at first glance, renders users (or post-users) without agency or, implicitly, value to companies which data-mine ongoing social practices. Yet the emergence of digital legacy management highlights the value of the data generated using social media, a value which persists even after death. The question of a digital estate thus illustrates the cumulative value of social media as media, even on an individual level. The ways Facebook and Google approach digital death are examined, demonstrating policies which enshrine the agency and rights of living users, but become far less coherent posthumously. Finally, along with digital legacy management, I will examine the potential for posthumous digital legacies which may, in some macabre ways, actually reanimate some aspects of a deceased user’s presence, such as the Lives On service which touts the slogan “when your heart stops beating, you'll keep tweeting”. Cumulatively, mapping digital legacy management by large online corporations, and the affordances of more focussed services dealing with digital death, illustrates the value of data generated by social media users, and the continued importance of the data even beyond the grave.

...(more)

M/C Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2013) - 'mining'

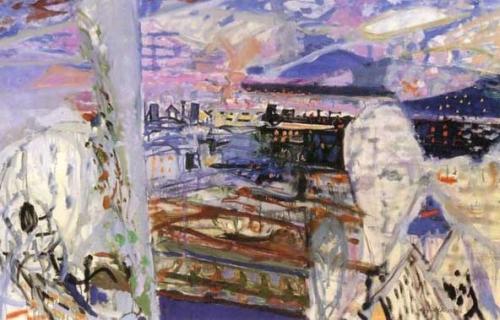

Roof Ridge Of Frederiksborg Castle

Christen Kųbke

The 10 best... skies in art

_______________________

Like many others who turned into writers, I disappeared into books when I was very young, disappeared into them like someone running into the woods. What surprised and still surprises me is that there was another side to the forest of stories and the solitude, that I came out that other side and met people there. Writers are solitaries by vocation and necessity. I sometimes think the test is not so much talent, which is not as rare as people think, but purpose or vocation, which manifests in part as the ability to endure a lot of solitude and keep working. Before writers are writers they are readers, living in books, through books, in the lives of others that are also the heads of others, in that act that is so intimate and yet so alone.

The Faraway Nearby

Rebecca Solnit guernica

(....)

Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me, my mother liked to recite, though words hurt her all the time, and behind the words the stories about how things should be and where she fell short, told by my father, by society, by the church, by the happy flawless women of advertisements. We all live in that world of images and stories, and most of us are damaged by some version of it, and if we’re lucky find others or make better ones that embrace and bless us.

As I wrote this, my friend Annie sent me a note from Easter Island, where she was working on a radio story. She wrote me of “sweeping grasslands, dormant volcanoes, sheer black volcanic cliffs dropping into the sea and those magnificent, stern moai”—the great stone heads—“scattered all over the island. I can’t stop wondering what possessed the Rapa nui to build them and then after that was over to conceive of the birdman cult.” Hundreds of years after the cultural near-extinction of their makers, the heads were still provoking thought; they were still in our heads; Annie wrote to me and put the birdman cult in mine.

(....)

The birdman cult might be just an extreme case of the stories we weave all the time that make a small item a trophy, a sign of spiritual or social status, a token that changes your life. Only the unfamiliarity of the birdman cult makes us remark on its arbitrariness, since in our own world people die in the attempt to climb mountains for no practical reason, kill because of words that insult them or their gods, and revere those who have won a prize handed over by a whimsical jury or because a combination of factors sent a ball into or over a net.

We live in dreams; we go into the shark-filled sea to carry them out; they make one egg of the sooty tern, also known as the wideawake, into something you can organize a whole society around. The tern’s egg is small, speckled, and nondescript. The god who presided over all this was named MakeMake. “The things we dream up…” wrote Annie. To become a maker is to make the world for others, not only the material world but the world of ideas that rules over the material world, the dreams we dream and inhabit together.

...(more) _______________________

In this remote island I perceived a place where I might fall asleep and dream, in imitation of the philosophers in this branch of literature. For Cicero crossed over into Africa when he was getting ready to dream. Moreover, in the same western ocean Plato fashioned Atlantis, whence he summoned imaginary aids to military valor.

— Kepler

Why Is Iceland a Portal to the Moon?

Justin E. H. Smith

There is a trite and obvious thing to say about Iceland, and that is that it looks like the moon. Descending into the Keflavik lava fields the other day, on an Icelandair flight from Paris, I was permitted to feel annoyed and a bit superior when I overheard the virgin French tourists behind me exclaiming as they gawked at the land below: Mais il n’y a rien lą! By ‘nothing’ I thought perhaps they had meant ‘no Michelin stars’, but then one of them added, as if on cue: C’est comme la lune! Yet if there is an association between the earth’s only satellite and this basalt outcropping of the mid-Atlantic range that is too obvious to mention, there is another that remains to this day far too occult, and that is as deserving of notice as the other is of suppression.

...(more)

berfroisIntellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters

_______________________

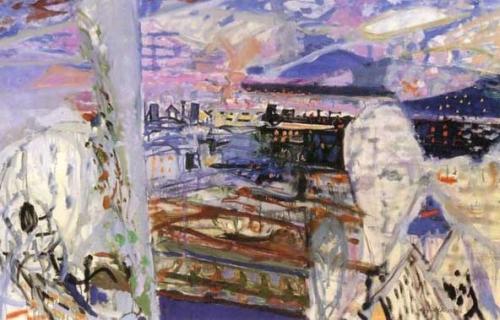

Night Landscape

1954

Max Gubler

b. May 26, 1898

_______________________

An 'Epidemical Distemper'

Conversion and Disorder, then and now

Marion Rust

On March 11, 2012, the New York Times Sunday Magazine ran a cover story about a small town in western New York where eighteen female high school students had recently begun twitching uncontrollably. One bruised her face with her own cell phone; others uttered involuntary cries in the school halls which teachers tried bravely to ignore. Fears of toxic contamination from an old train wreck brought social activist Erin Brockovich to the scene, while psychologists made the more widely persuasive diagnosis of conversion disorder, or—since multiple individuals were involved—mass psychogenic illness. Environmentally induced malady or psychosomatic pathology? In this debate, perhaps even more than the girls' behaviors alone, the contorted bodies of Le Roy, New York, powerfully suggest another group of twitching girls from almost two centuries before. There too, leading intellectuals used the events of a town few had heard of—Northampton, Massachusetts—to justify conflicting worldviews by making exemplary subjects of young women undergoing a shared affliction. Characterized by "outcries, faintings, convulsions and such like," their behavior was described in eerily similar terms to that of the Le Roy girls with their "facial tics, body twitches, vocal outbursts, seizures." Spastic girls, writhing girls, girls in pain, girls out of control. All made for good reading, in 1737 as again in 2012.

Both events share key features: from the use of the term "conversion," to the attention brought to bear on an otherwise unremarkable location, to public figures' use of the phenomenon for self-promotion, to the predominance of women in their exposition. In all these arenas, we will see that the struggle to interpret these behaviors correctly was also a struggle about social order. The crisis in Le Roy—a town of less than 10,000 in New York's rust belt, between Rochester and Buffalo—began with one person, a seventeen-year-old high school cheerleader who woke up from a nap in the fall of 2011 experiencing facial spasms. Within a couple of months, three other girls, two of them cheerleaders, had similar symptoms, including stuttering and uncontrollable tics. Eventually, at least eighteen members of the high school were afflicted, all teenage girls except for two. The seemingly inexplicable nature of this contagion made for widespread media coverage (including local TV news, live appearances on "Dr. Drew," online reporting by well-established sites such as The Daily Beast, and profiles in some of the nation's most august print outlets). As public attention has diminished (and with it the strange combination of stress and sudden fame that may have fueled the symptoms in the first place), many individuals have recovered. Slightly less than a year after that fateful nap, one local station reported that the girls' physical condition had improved significantly, with many living "symptom-free." As for the conditions that contributed to the malady—which could range from widespread economic decline, to the absence of fathers in most sufferers' lives, to the sometimes brutal social hierarchies of high school—they are perhaps even more mysterious, and more recalcitrant, than the tics themselves.

...(more)

Common-place Spring 2013

_______________________

The Path up from Marina Piccola

c.1838

Christen Kųbke

b. May 26, 1810

Succulents

Point Lobos 1921

Imogen Cunningham

1883 - 1976

_______________________

The Far Field

Theodore Roethke

(....)

I learned not to fear infinity,

The far field, the windy cliffs of forever,

The dying of time in the white light of tomorrow,

The wheel turning away from itself,

The sprawl of the wave,

The on-coming water.

(....)

IV

The lost self changes,

Turning toward the sea,

A sea-shape turning around, --

An old man with his feet before the fire,

In robes of green, in garments of adieu.

A man faced with his own immensity

Wakes all the waves, all their loose wandering fire.

The murmur of the absolute, the why

Of being born falls on his naked ears.

His spirit moves like monumental wind

That gentles on a sunny blue plateau.

He is the end of things, the final man.

All finite things reveal infinitude:

The mountain with its singular bright shade

Like the blue shine on freshly frozen snow,

The after-light upon ice-burdened pines;

Odor of basswood on a mountain-slope,

A scent beloved of bees;

Silence of water above a sunken tree :

The pure serene of memory in one man, --

A ripple widening from a single stone

Winding around the waters of the world.

...(more)

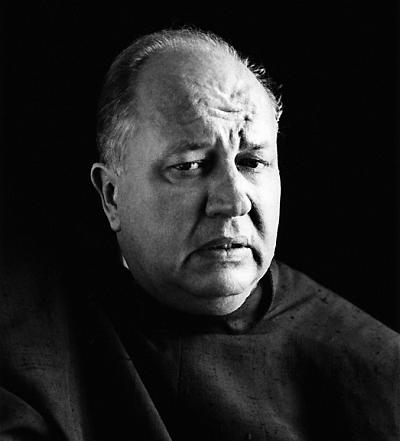

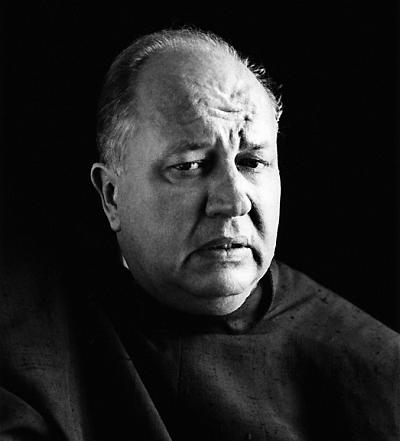

Theodore Roethke

May 25, 1908 – August 1, 1963

Photograph by Imogen Cunningham, 1959

Stanley Kunitz on Theodore Roethke

_______________________

The Waking

Theodore Roethke

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

We think by feeling. What is there to know?

I hear my being dance from ear to ear.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Of those so close beside me, which are you?

God bless the Ground! I shall walk softly there,

And learn by going where I have to go.

Light takes the Tree; but who can tell us how?

The lowly worm climbs up a winding stair;

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Great Nature has another thing to do

To you and me, so take the lively air,

And, lovely, learn by going where to go.

This shaking keeps me steady. I should know.

What falls away is always. And is near.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I learn by going where I have to go.

_______________________

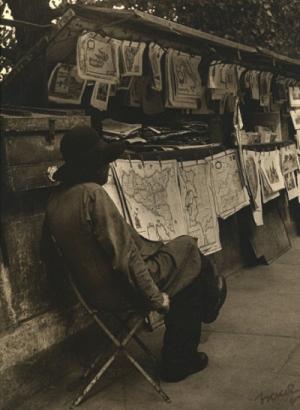

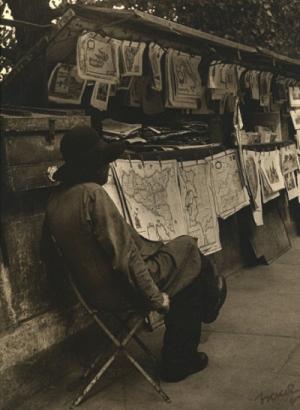

Map Merchant

Paris, 1949

Vilem Kriz, An American Surrealist

Scott Nichols Gallery

via

_______________________

Word Choice

Five Poems

Sommer Browning

bomb

From Friend

(....)

Sommer, I’m dying. I get this message on my phone in line at Rite-Aid. Sommer, I’m dying, you scream in my ear at the rock show. Sommer, I’m dying, you write in closing on a postcard from San Francisco. Sommer, I’m dying, it’s my heart, Sommer I’m dying, can you feel this? Is it normal? as we stomp through the snow to get cigarettes. Jesus woke up, but who muscled the boulder away? Some prince kissed the beauty, but who wrote it all down? Let’s go to the mummy exhibition, let’s read aloud Fear and Trembling, let’s slow the flow through our carotid. Sommer, I’m dying. Present tense. Subject. Verb. The thinning blood vessel, the soft pulsating stone, retina shriveled and rattling around in the skull. I can hear it when I jump. Then don’t jump, I say.

...(more)

_______________________

At Point Lobos

Imogen Cunningham

1921

_______________________

You might want to ask—if there is such a simple argument for physicalism, how come everybody hasn’t always been a physicalist? That’s a good question, and there is a good answer. The ‘causal completeness of physics’ wasn’t widely accepted until recently. A century ago mainstream science was still quite happy to countenance vital and mental powers which had a ‘downwards’ causal influence on the physical realm in a straightforwardly interactionist way. It was only in the middle of the last century that science finally concluded that there are no such non-physical forces. At which point a whole pile of smart philosophers (Feigl, Smart, Putnam, Davidson, Lewis) quickly pointed out that mental, biological and social phenomena must themselves be physical, in order to produce the physical effects that they do.

David Papineau interviewed by Richard Marshall

3:am

_______________________

“There are no proprietary philosophical questions that are worth answering, nor is there any productive philosophical method that does not engage the sciences. But there are lots of deeply important (and fascinating and frustrating) questions about minds, morals, language, culture and more. To make progress on them we need to use anything that science can tell us, and any method that works.”

— Steve Stich

without concepts

Edouard Machery interviewed by Richard Marshall 3:am

(....)

Your book ‘Doing Without Concepts’ elaborates this idea. You argue that we should do away with talk about concepts, which is really very radical. Some might say you’re throwing out the baby with the bathwater and the bath as well! Can you explain your idea?

EM: It IS a fairly radical idea! And not one everybody is happy with!

In any case, psychologists and philosophers of psychology often assume that concepts share many scientifically important properties, and that the goal of a theory of concepts is to identify these properties. In philosophical jargon, concepts are supposed to form “a natural kind.” So, psychologists and philosophers of psychology have developed various theories of concepts, and have defended their pet theories by undermining the competing theories. The take-home message of Doing without Concepts is that this “natural kind” assumption is fundamentally misguided, and that as a result many debates between psychologists and philosophers about what the right theory of concepts is are empty.

One of the things psychology has taught me is that we are sometimes poor at predicting how we would behave, and I often express skepticism at my friends’ and acquaintances’ assured predictions about how they would behave in such and such situations. When I predict my behavior, I tend to assume that I would behave like most people, and I often try to determine what psychological research predicts about the relevant type of behavior. This sometimes leads me to predict that I will behave in particular way, while I feel, with great confidence, that *I*, in contrast to other people, will behave differently. Weird mind split.

...(more)

_______________________

The Renewal

Theodore Roethke

1

What glories would we? Motions of the soul?

The centaur and the sibyl romp and sing

Within the reach of my imagining:

Such affirmations are perpetual.

I teach my sighs to lengthen into songs,

Yet, like a tree, endure the shift of things.

(....)

4

Dry bones! Dry bones! I find my loving heart,

Illumination brought to such a pitch

I see the rubblestones begin to stretch

As if reality had split apart

And the whole motion of the soul lay bare:

I find that love, and I am everywhere.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Dolor

Theodore Roethke

I have known the inexorable sadness of pencils,

Neat in their boxes, dolor of pad and paper weight,

All the misery of manilla folders and mucilage,

Desolation in immaculate public places,

Lonely reception room, lavatory, switchboard,

The unalterable pathos of basin and pitcher,

Ritual of multigraph, paper-clip, comma,

Endless duplicaton of lives and objects.

And I have seen dust from the walls of institutions,

Finer than flour, alive, more dangerous than silica,

Sift, almost invisible, through long afternoons of tedium,

Dropping a fine film on nails and delicate eyebrows,

Glazing the pale hair, the duplicate grey standard faces.

photo - mw

_______________________

Nothing Funnier Than Unhappiness:

A Necessarily Ill-Informed Argument for Flann O’Brien’s The Poor Mouth as the Funniest Book Ever Written

Mark O'connell

The Millions

I would dearly love to be able to start this piece by saying that

The Poor Mouth is the funniest book ever written. It’d be a real lapel-grabber, for one thing, an opening gambit the casual Millions reader would find it hard to walk away from. And for all I know, it might well be true to say such a thing. Because here’s how funny it is: It’s funnier than A Confederacy of Dunces. It’s funnier than Money or Lucky Jim. It’s funnier than any of the product that any of your modern literary LOL-traffickers (your Lipsytes, your Shteyngarts) have put on the street. It beats Shalom Auslander to a bloody, chuckling pulp with his own funny-bone. And it is, let me tell you, immeasurably funnier than however funny you insist on finding Fifty Shades of Grey. The reason I can’t confidently say that it’s the funniest book ever written is that I haven’t read every book ever written. What I can confidently say is that The Poor Mouth is the funniest book by Flann O’Brien (or Myles na gCopaleen, or any other joker in the shuffling deck of pseudonyms Brian O’Nolan wrote under). And if this makes it, by default, the funniest book ever written, then all well and good; but it is certainly the funniest book I’ve ever read.

(....)

... There’s something about the improbable combination of sober causality and delirious wretchedness (“As a result of the never-ending flailing of misfortune”; “a case of going from bad to worse”) that comes on like an outright petition for heartless juvenile ridicule. “Nothing is funnier than unhappiness,” as Nell puts it in Beckett’s Endgame. We should take this point seriously, coming as it does from an old woman who has no legs and lives in a dustbin.

Beckett’s contemporary Flann O’Brien understood this, too: unhappiness is the comic goldmine from which he extracts The Poor Mouth’s raw material. He is parodying Irish language books like Peig and, in particular, Tomįs Ó Criomhthain’s memoir An t-Oileįnach (The Islander); but in a broader sense, he’s ridiculing the forces of cultural nationalism that promoted these books as exemplars of an idealized and essentialized form of Irishness: rural, uneducated, poor, priest-fearing, and truly, superbly Gaelic.

O’Brien’s narrator, Bonaparte O’Coonassa, is not so much a person as a humanoid suffering-receptacle, a cruel reductio ad absurdium of the “noble savage” ideal of rural Irishness promoted by Yeats and the largely Anglo-Irish and Dublin-based literary revival movement. A lot of the book’s funniness comes from its absurdly stiff language (which reflects an equally stiff original Irish), but that language is a perfect means of conveying a drastically overdetermined determinism – a sort of hysterical stoicism which seems characteristically and paradoxically Irish. The book’s comedic logic is roughly as follows: to be Irish is to be poor and miserable, and so anything but the most extreme poverty and misery falls short of authentic Irish experience. The hardship into which Bonaparte is born, out on the desperate western edge of Europe, is seen as neither more nor less than the regrettable but unavoidable condition of Irishness, an accepted fate of boiled potatoes and perpetual rainfall. “It has,” as he puts it, “always been the destiny of the true Gaels (if the books be credible) to live in a small, lime-white house in the corner of the glen as you go eastwards along the road and that must be the explanation that when I reached this life there was no good habitation for me but the reverse in all truth.”

...(more)

_______________________

Egg

Ness

Judith Crispin

via

_______________________

The Moral Status of Rocks

Justin E. H. Smith

A student in rural Iceland, of sheep-farming stock, had her guard down, or didn't yet have a guard. She didn't know how to talk to foreigners, or perhaps felt there was something she had to get across to foreigners, or to this foreigner, who showed an interest in her country. She said, in the hope of conveying to me the whole ethical-spiritual outlook of her country in a single concrete example: In Iceland we are taught not to smash rocks.

...(more)

_______________________

ctrl-z.net.au

#2 (December 2012)

The Exorcism of Exorcism

—The Enchantment of Materiality in Derrida and Marx

Nicole Pepperell

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

"Four Preliminary Notes" & "A Stray Note" from Underlight

Aaron McCollough

presented by Jerome Rothenberg

A Quintessence

Fear of getting stuck makes the soul aware, forlorn.

The messenger, he ran; he took on need and got hanged. Sticking

is constant.

Her look says no amount of permission can overcome the law’s

resistance.

The window bounds everything, and all threats are announced.

Measured in a friend and jackal, our evenings narrow, but friends

pass.

Permit these stops as the reed still quavers higher. Observe small

minutes. Even if this means more defilement, unlatch the top

again and put your face in the steam.

Not a failure of the tongue; what the mouth cannot encompass

with every organ and orifice.

We are trying to make do with this dross, this sweat of the sun.

The tree branch a warbler. The incisor that’s plugged in the hide.

...(more)

Aaron McCollough

Underlight, Ugly Duckling Press, 2012

_______________________

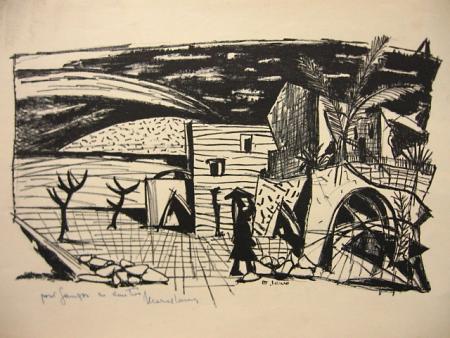

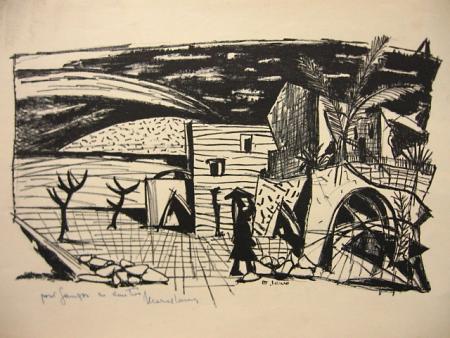

Marcel Janco

May 24, 1895 – April 21, 1984

_______________________

Two prose poems

Aaron McCollough

jacket

Elegy

Probably wishing this on you once as it happened. This chocolate bar. This passing dilemma. As it may not happen again — our own vexatious downer; as we cannot speak and only glare in the Tennessee heat and only pass in a memory of animus, I’m sorry.

Morning glories in the chain-link fence, winding out. Mission of Burma. Beneath the ball diamond, through there the yellow cloud of white cloud honey suckle, kettle and cat bones.

That you would die. Only one death for you and me and one more for me and who? The hand has pushed your death along as a hand pushes a crease to the corner of a bed. In lots more dangerous places. All the time zones and planets.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

notes on the novel, genre, woolwich

ads without products

(....)

Genre is also another name for myth. While it sometimes postures as science, it has far more in common with superstition. Throw salt over your shoulder, and lucky will occur. One character says something, the other, naturally, touches wood. We now, in our pharmacologically-lexiconed period, are far more likely to call superstitious practices the symptoms of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. One has to check, and check again, that the water’s not running in the bathroom before one leaves the flat. Push hard three times on the front door to make sure it’s locked… or else another storyline will ensue, the one that has an evening return to a gaping door, the laptop gone, the bedroom drawers dumped. This is literally it – some sort of chemical depletion or superfluity occurs, some traumatic event takes place, and then an almost mystical belief in certain irrational storylines takes over. To disobey the mandates of genre is to open oneself to an unhappy ending.

(....)

The novel makes us stupid in one sense, solipsistic, tends to make us look for our angle on things, what does this mean to us? What were the attackers yesterday, in both his words and deeds, and deeds both during and after the attack, trying to say to me? Or at least us? There is a counter-instinct, for those disciplined a certain way, to try to climb up the ladder of transcendent wisdom, to disavow the inwrought narcissism of our conditioned response. To gasp and yell when the news commentators reduce a global to a local question, an a serious question to a matter of insanity or unanchored spite. They might think what they want, but they have no right to act it out here. To force us into these stringent attempts to adjust the genre back to something we’re comfortable with.

But the attempt to climb out of the fray of self-interest, however complex, however Wallace-ianly convoluted and self-reflexive, is of course a trope in yet another sort of story, another sort of myth, one that – we need to remind ourselves – has the deepest affinities with an imperial mindset, one that takes the world panoptically, one for whom impersonality is a transferable skill.

...(more)

Composition with taches

ca. 1875Victor Hugo

26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885

Art of Victor Hugo:

an overview of his drawings

_______________________

Control And Freedom: Power And Paranoia In The Age Of Fiber Optics

Wendy Hui-Kyong Chun

google books

In this book, I do not condemn the Internet—if anything, I hold it dear. Liking it or hating it, as such, is as pointless as being ‘‘optimistic’’ or ‘‘pessimistic’’ about its future. Rather, what we need is a serious en- gagement with the ways in which the Internet enables communications between humans and machines, enables—and stems from—a freedom that cannot be controlled. Because freedom is a fact we all share, we have decisions to make: freedom is not the result of our decisions, but rather, as Friedrich Schelling and Jean Luc Nancy have argued, what makes our decisions possible. This freedom is not inherently good, but entails a decision for ‘‘good’’—habitation and limitation—or for ‘‘evil’’— destruction. The gaps within technological control, the differences between technological control and its rhetorical counterpart, and technol- ogy’s constant failures mean that our control systems can never entirely make these decisions for us.

Fiber-optic networks, this book argues, enable communications that physically instantiate and thus shatter enlightenment; they also link to- gether disparate locations that only sometimes communicate. We must take seriously the vulnerability that comes with communications—not so that we simply condemn or accept all vulnerability without question but so that we might work together to create vulnerable systems with which we can live.

pdf available at monoskop

_______________________

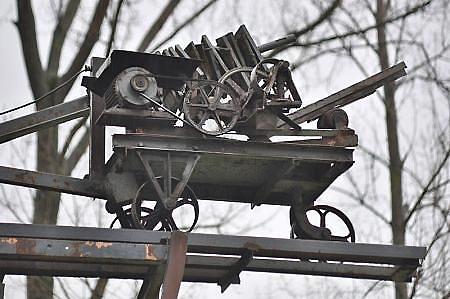

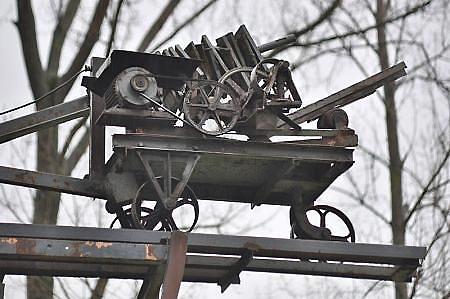

Heureka

detail

Jean Tinguely

(22 May 1925 – 30 August 1991)

_______________________

Creation Stories: Myths About the Origins of Money

Christine A. Desan

_______________________

Jean Tinguely

Jean Tinguely: “A Magic Stronger Than Death”

Jean Tinguely Art Machines, 1959

_______________________

The Challenge of Theoterrorism

Paul Cliteur

new english review

(....)

The politico-religious ideologies that target free speech go under a number of different names. “Fundamentalism,” “extremism,” “radicalism” – and these are only a few of the epithets that are used in the scholarly literature and political discourse on the subject. The most popular label is “extremism.” Although this term is current, I am reluctant to use it because it is too vague to be useful (there are many kinds of extremist behavior after all). A better term is “terrorism” perhaps, because this is used in legislation and scholarly literature. But even “terrorism” has many forms. The most remarkable development of the last decades is the resurgence of religious terrorism, or what one may also call “theoterrorism.”

Theoterrorism is the type of terrorism that legitimizes violence by referring to “God.” The theoterrorist thinks and claims that the violence he exerts on the nation-state is done “in the name of God.”

Arguably, the theoterrorist may be wrong in thinking he is a divinely appointed angel of vengeance. But it is perfectly possible not to enter into a discussion with theoterrorists or religious believers on whether or not the terrorist is right in his convictions. This would require an excursion into the philosophy of religion and theology that is unnecessary for someone interested in the social significance of theoterrorism. For an understanding of our contemporary world it may be more fruitful not to approach religion from a believer’s perspective, but from the angle of the social scientist who simply analyzes what other people think. In this case: what the religious terrorist thinks. What one may do is try to understand how his worldview is constructed.

Many people are reluctant to engage in this kind of research. They are concerned with something quite different: protecting religious minorities from discrimination and the “stereotyping of their religion.” Or they have the ambition to explain why the essence of Judaism, Christianity or Islam is averse to violence.7 I fully recognize the importance of that type of commentary from a believers perspective. But it is not the kind of approach that makes it possible to understand the theoterrorist challenge. I fear these well-meaning people are dangerously mistaken. The greatest contribution you can make to the peaceful coexistence of people of good will is to make a fair assessment of the role religion plays in contemporary terrorism, and not to suppress or censor people who dare to address this issue.

...(more)

_______________________

"Le Gai Chāteau"

Flandres

ca.1847

Victor Hugo

_______________________

Blogging Toward The Kingdom

Booze, rage and justice in the participation age

Joe Bageant

(1946–2011)

... it is the straight sober world and its truths that are hard. Alienation. Inner rage. Many of my essays were born in an attempt to communicate working class alienation, separation and rage -- which is the same as middle class rage, but self-described and expressed differently). Most of the liberal thinkers I know still do not grasp that the anxiety working people have, even the Tea Partiers, are rooted in the same things as their own. Yes, the right is definitely cruel. And yes, it can by now be called fascist. However, to deal with what has happened, one must come to grips with what produced the internal distrust upon which fascist empires are built.

The brutal way Americans were forced to internalize the values of a gangster capitalist class continues to elude nearly all Americans. Most foreigners too. This is to say nothing of how our system replaced our humanity with ideology, our liberty with money, and fostered fascist nationalism through profound degeneration of the people's mind and spirit. It's not as if one can ever escape that sort of thing, either by going to a place like Mexico, getting drunk or whatever. We are made in Americas' image, whether we admit it or not, and America's image is the face on a ten dollar bill.

(....)

It is now clear to me that the people's rage is a tool in the hands of the new electronic and digital corporate state. Its various channels, eddies and pools, regardless of type, can be directed toward all sorts of mischief and profit. Left or right, the angry throngs on both sides can be managed and directed. They can be sent chasing various injustices, denouncing evil characters on Wall Street, Times Square bombers, BP executives, or whatever, worked up into slobbering outrage over Sarah Palin, and thus kept divided and working against each other for the benefit of last gasp capitalism.

Once outside the furious drek of American political and economic life, and having finished the last book I will ever write, I found myself asking: "Why did the good in the American people not triumph? How can it be that so many progressive, justice-loving citizens failed? Their positions were well reasoned. The facts were indisputably on their side. Obviously, there was, and is, more going on than merely losing battles to demagoguery and meanness. Why do we lose the important fights so consistently? What has kept us from establishing a more just kingdom? Something is missing.

(....)

The blinking reptilian elites now own our entire material needs hierarchy chain, top to bottom. You eat, shit, work, fuck and die at the pleasure of their Great Machine. The presence of six billion others, most of whom are in the same situation, all but guarantees this as our material destiny on a finite and increasingly poisoned planet, before the big hasta la vista.

...(more)

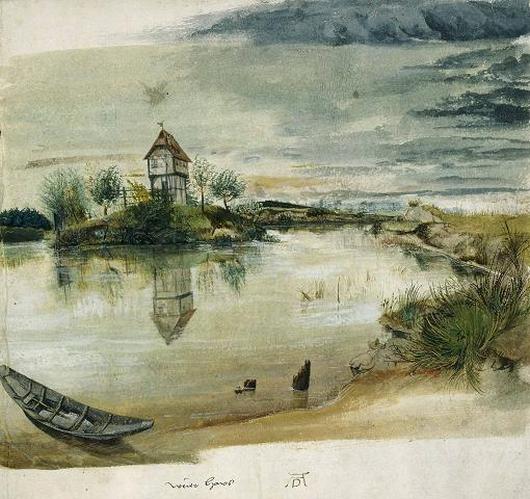

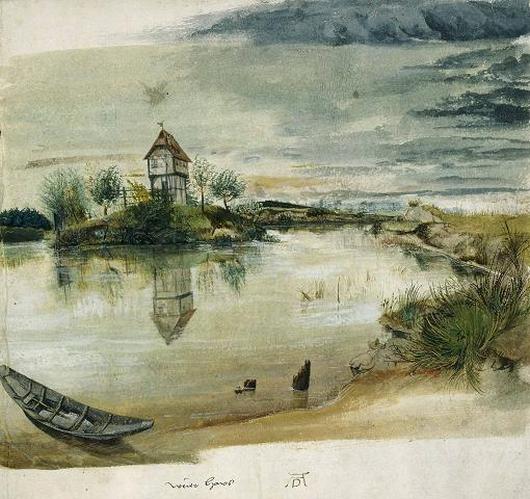

Fisherman's House on a Lake

near Nuremberg

C.1496

Albrecht Dürer

21 May 1471 - 6 April 1528

_______________________

Argument with Myself

Mike Jay reviews

Permanent Present Tense: The Man with No Memory, and What He Taught the World by Suzanne Corkin

Memory creates our identity, but it also exposes the illusion of a coherent self: a memory is not a thing but an act that alters and rearranges even as it retrieves. Although some of its operations can be trained to an astonishing pitch, most take place autonomously, beyond the reach of the conscious mind. As we age, it distorts and foreshortens: present experience becomes harder to impress on the mind, and the long-forgotten past seems to draw closer; University Challenge gets easier, remembering what you came downstairs for gets harder. Yet if we were somehow to freeze our memory at the youthful peak of its powers, around our late twenties, we would not create a polished version of ourselves analogous to a youthful body, but an early, scrappy draft composed of childhood memories and school-learning, barely recognisable to our older selves.

Something like this happened to the most famous case of amnesia in 20th-century science, a man known only as ‘H.M.’ until his death in 2008. When he was 27, a disastrous brain operation destroyed his ability to form new memories, and he lived for the next 55 years in a rolling thirty-second loop of awareness, a ‘permanent present tense’.

(....)

For the long remainder of his life Henry was blandly unaware of his own story. He would readily volunteer that he had ‘a lot of trouble remembering things’; if pressed, he might speculate that ‘I have possibly had an operation or something.’ His short span of consciousness led to repetitive behaviour – making the same observation repeatedly, or mechanically eating two lunches in a row – but his conversation was characterised by a gentle wit and quizzical, punning exchanges that seemed to test every statement for possible meanings. (When Corkin commented on Henry’s love of crosswords by dubbing him ‘the puzzle king’, he responded: ‘I’m puzzling!’) He had occasional episodes of frustration, anger or panic, but was usually good-natured and accepting of the scene around him. In many respects he displayed the serenity and detachment promised by the Buddhist ideal of living in the now, freed from regrets about the past or anxieties for the future. He was certainly more content than his most extreme opposite, Solomon Shereshevsky, the subject of A.R. Luria’s The Mind of a Mnemonist. Shereshevsky’s inability to forget became a life-destroying torment. ‘The trail of memory can feel like a heavy chain,’ Corkin observes, ‘keeping us locked into the identities we have created for ourselves.’ Henry was, by contrast, ‘free from the moorings that keep us anchored in time’, though Corkin also wonders whether his lack of anxiety and emotional churn might have been related to the partial loss of his amygdala.

...(more)

_______________________

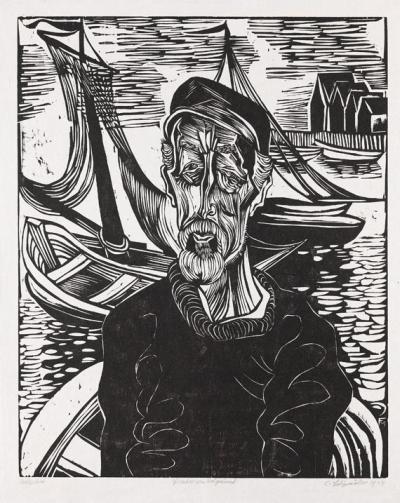

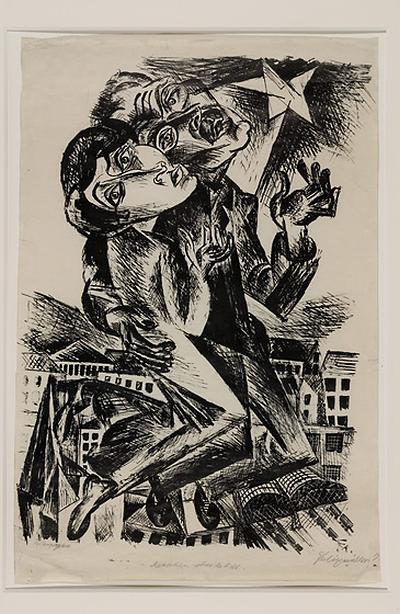

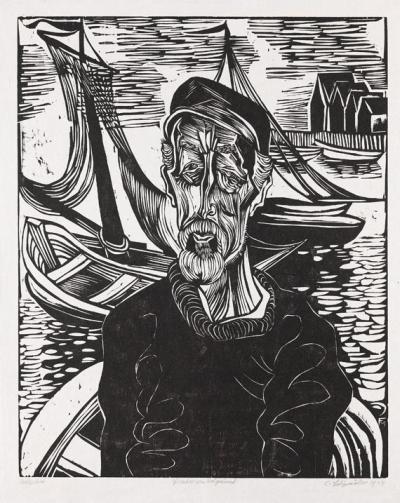

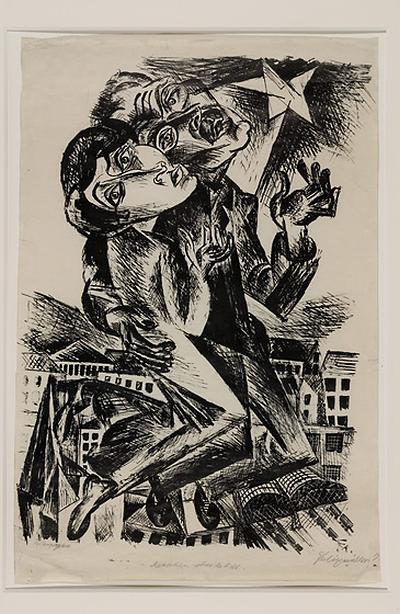

Conrad Felixmüller

_______________________

The U.S. as a party-state

Adam Kotsko

An und für sich

... Interpreting the party-state phenomenon through liberal democratic norms, the “totalitarian” analysis decides that since something like civil society or the private sphere no longer has the desired autonomy, we can only conclude that the state, as the only other available center of power, is over-dominant. This is a profound misreading of the situation, however, as Foucault points out in Birth of Biopolitics. The problem in party-states is not that the formal state structures are too strong, but that they’re too weak to restrain the party-movement that instrumentalizes them....(more)

_______________________

Corruption Study

Study of Changing Societies

Volume 1'6

_______________________

Men above the World

(Epitaph for Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht)

1919

Conrad Felixmüller

(21 May 1897 - 24 March 1977)

_______________________

Singing

Primo Levi

Translation by Marco Sonzogni, Harry Thomas

…But when we began to sing

Our songs, senseless and good,

It seemed that everything

Stood as it once had stood.

The days were merely days.

Seven made a week.

Killing we thought was wicked.

Of dying we didn’t speak.

The months sped by so fast,

With too many to come for complaints!

Again we were only young:

Not martyrs, the shamed, or saints.

We had these thoughts and others

As long as we could sing.

But it’s all hard to explain,

Being a cloudlike thing.

3 January 1946

MPT (Modern Poetry in Translation)

Poetry and the State, Series 3 No.15

Edited by David Constantine, Helen Constantine

_______________________

Carnival Evening

1886

Henri Rousseau

May 21, 1844 – September 2, 1910

_______________________

Husserl’s Theoretical Horizon, or a Ghost Is a House You Live in

C. Dylan Bassett

1.

Ghosts do not happen alone. Ghosts are made

from rooms and glass and cherry trees. They lie down and become

horizons. You see by them.

You remember.

2.

Some ghosts want to undo you, to take you apart.

They crawl in cupboards and bang against the wood.

They rearrange furniture and hide

your good shoe. You cannot fight them, you do

not know their names. Other ghosts want

to hold you together, to bake your favorite lemon cookies

in the middle of the night and climb in bed with you

and comb your hair with their glassy fingers.

You hate these ghosts most of all.

You know their names exactly.

...(more)

Memorious 19

news stand

New York City

1963

Street Exposure: The Photographs of Ronald Reis

289 photographs and contact sheets

made between 1957 and 1973

primarily in London and New York City

Duke University Libraries Digital Collections

via

_______________________

Digging Up Bones Or, The Labyrinths Beneath Our Feet

Tom Jacobs

(....)

***

I told this story late at night the other day while I was making cocktails for friends, and I didn't think much about what it was about or what it meant or where it was headed. I just told it. But I can now see some kind of pattern, some kind of meaning in the bare fabric of the thing. A warped reflection of what's been passing through my mind lately. There's something there about what happens when we excavate and examine the past. It can as easily induce insanity as it can generate revelation. To some extent it's about how we regard it, about how we comport ourselves in the presence of history. We can choose to hold it close or to cast it away. It can engulf us or it can reignite something that's been lost or forgotten. Either way, the excavation will lead us to seeing and maybe even understanding something new and strange.