|

Chemical Brook enters the Sudbury River,

Ashland, Massachusetts.

1991

Accommodating Nature

The Photographs of Frank Gohlke

via

_______________________

A Conversation with B. K. Fischer

The Offending Adam

(....)I try the best I can to write evocatively, and to find and publish evocative writing, and what that means is a moving target. I’m not afraid of difficulty, and I’m also not afraid of clarity. Each poem, each project, each occasion for poems or book of poems, demands mystery and accessibility in different measure. I have a perhaps old-fashioned faith in process, in craft. But it’s a sustaining faith in the work itself. We’re all going to die soon. Who cares if we establish sufficient avant-garde street cred? Believe me, I’ve got post-postmodern messes to make with language, confrontations and collaborations and appropriations to enact and refract, but I’ve also got stories to tell, suffering to relate, characters to envoice. I always go back to Adrienne Rich’s lines: “This is the oppressor’s language, / yet I need it to talk to you.”

...(more)

B. K. Fischervia

_______________________

Custodians of Ancestral Lore

1992

Kenojuak’s Birds

50 Watts

Kenojuak Ashevak

1927 - 2013

_______________________

“Idle No More”: First Nations Resistance Movement across Canada

Global Research News Hour - Episode 10

(59:29)

_______________________

Pathos:

Lars Iyer interviewed

... we needn’t follow Cioran’s brand of nihilism. The philosopher Levinas often quotes Pascal: ‘”That is my place in the sun”: that’s how the usurpation of the world began’. We are usurpers, Levinas claims, because the place we occupy, the life we enjoy, is lived at the expense of others. We do not have to subscribe to the details of Levinas’s philosophy to grant him this point. Before Nietzsche’s would-be tragic suffering, before Larkin’s less-than-tragic suffering, there is the suffering of others, of those whose place you’ve usurped. Doesn’t any account of the ‘truth of one’s condition’ have to include these others?

For me, Weil’s practice of writing is exemplary when it comes to truth-telling. For a writer like Weil, the days of ruin and devastation are always at hand. Our time is always apocalyptic, and we are each responsible for the apocalypse. The literary task lies in marking this ‘end of times’ in our work. I think of something Gillian Rose quoted in her writings: ‘Keep your mind in hell and despair not’....(more)

Full StopReviews. Interviews. Marginalia.

_______________________

Miquel Llonch

via

_______________________

In Transit - a Sonnet Square

Martin Johnston

2. Biography

About love and hate and boredom they were equally

barracudas, took an arm or leg quick as winking,

their totem Monkey Aware-of-Vacuity.

Empedocles added to the four elements

Love and Strife to set them spinning, Aeschylus

invented tragedy by adding the second actor.

Back past the sold houses in the lost domains

down in the midden-humus

glows the rotting trelliswork of “family”,

odd slug-coloured tubers wince at the touch

with feigned unanthropomorphic shyness,

naked pink tendrils explore holes. It is all

tentative, and these days the Island supports

a “Jungian sandlot therapist”.

Martin Johnston (1947 – 1990)Jacket special

Martin Johnston at the Australian Poetry Library

_______________________

January thaw

photo - mw

Dryhope Tower from Ward Law

Walter Baxter

wikimedia commons

_______________________

you can’t have the story without the language.

There is no story without the language.

Without the language we’d have only dreams and nightmares, monsters and wars.

TensionsRobert Kelly on New Gilgamesh & Beowulf Translations posted by Pierre Joris

(....)What’s missing in almost all translations of the old stuff (the classics, the canon, that fleet of inscrutable foreign vessels lined up, sailing in against our ignorance) is tension. Tension means stretching, pulling the fabric taut, making the hearer (reader) hold the breath.

Scholars are mostly not good at holding anybody’s breath. (I think of a few exceptions—Magoun’s Kalevala, Tedlock’s Popol Vuh, Arrowsmith’s Petronius) but they are indeed exceptions.

But here come two grand triumphs of poetry bringing old instances of itself to new life. Simply said, a good translation of a poem must be itself a good poem.

(....)

These are primal narrations, and need careful enactment in our stale new languages. To feel their energies, to cherish their differences.

A translation has to make love with the text. But not to it — the translator is not a suave lothario, touching every text with the same practiced strokes. No, the translator must meet each text humble to its difference. Humble, but horny.

...(more)

_______________________

Ancestral Lines

David Ferry

It’s as when following the others’ lines,

Which are the tracks of somebody gone before,

Leaving me mischievous clues, telling me who

They were and who it was they weren’t,

And who it is I am because of them,

Or, just for the moment, reading them, I am,

Although the next moment I’m back in myself, and lost.

My father at the piano saying to me,

“Listen to this, he called the piece Warum?”

And the nearest my father could come to saying what

He made of that was lamely to say he didn’t,

Schumann didn’t, my father didn’t, know why.

“What’s in a dog’s heart”? I once asked in a poem,

And Christopher Ricks when he read it said, “Search me.”

He wasn’t just being funny, he was right.

You can’t tell anything much about who you are

By exercising on the Romantic bars.

What are the wild waves saying? I don’t know.

And Shelley didn’t know, and knew he didn’t.

In his great poem, “Ode to the West Wind,” he

Said that the leaves of his pages were blowing away,

Dead leaves, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing.

Poetry (January 2012).

David Ferry at the Poetry Foundation

David Ferry’s Beautiful Thefts

Dan Chiasson

(....)

David Ferry, who, at the age of eighty-eight, has just won the National Book Award for poetry, is a special kind of thief. He carries us to places we can’t possibly visit, from the Mesopotamia of Gilgamesh to Horace and Virgil’s Rome. No American poet has translated better the greatest classical authors; Ferry’s translations of Horace are among the predominant texts in contemporary American poetry, teaching American poets (I’m one of them) the Horatian tones—the modesty, civility, and gossip; the swift, fly-by urbanity—that went missing from much of the best American poetry of the seventies and eighties. How strange to have the American vernacular put back in our mouths by this roundabout method. I can remember reading these lines of Horace—of Ferry’s Horace—with amazement at their simple, unprepossessing ecstasy:

Because the muses favor me and love me,

As far as I’m concerned let the wild winds carry

All sadness and trepidation far away. (Odes, I.26)

Ferry’s translations of Virgil are astonishing, and the best of them are Virgil’s Georgics, “the best poem by the best poet,” in Dryden’s estimation. How can anyone achieve such majesty when talking about bees and husbandry? He is now at work on the Aeneid, actuarial tables be damned.

Because Ferry has translated the works of others so well and so prolifically, and because he works comparatively slowly, his original poems risk being overlooked. ...(more)

_______________________

My castle

Poemas del rio Wang

_______________________

An everyday afterlife: Knausgaard revisited

Stephen Mitchelmore

This Space

(....)

We can say Kafka’s work has more in common with Knausgaard’s in terms of style, that is, in its comparative disconnect from style. In both we are drawn more to the specific events described, their curious and horrific banality, rather than to immersion in aesthetic bliss, while at the same time we feel compelled to draw back and seek an organising principle, to imagine such events as part of a containable world view, and then to resubmerge in a newly configured aesthetic bliss. However, Kafka’s is the prime example of a body of work that is never quite enough, a lack into which it is impossible to submerge. The deluge of secondary texts does this for us. Maurice Blanchot asks what needs to done to rescue Kafka from this fate, one to which Kafka himself contributed, and his answer is to recommend regarding his work as Kafka had wanted: in its absence. He observes that, with the publication of the Diaries, Kafka the writer was placed in the foreground and he is the one we look for in the work. He wonders if Kafka foresaw such a disaster and that is why he wanted his work destroyed. The opposite is true of My Struggle: knowledge of Knausgaard life saturates the page and the interviews and reports of the scandalised response in Norway offer no room to move away in relief: there is nowhere else to look but the work. But what then is the work?

...(more)

_______________________

four poems

John Latta

Scuff

‘The musickracket / of all ownership’

is how Olson puts it,

the scuff and connivance of

things, big endless rehearsals of

object-counting to no account.

Put cup in the cupboard.

Knife in drawer. The exterior

smear captured through the draperies,

out in the mestizo tempo

and slurry of the uncodified

night. Out where the conjecturalist’s

need to say something apt

bottoms out in random off-

gradient stitchery, and the unsedimented

refuse of daily rhythm grinds

its own plenary stochastic truck.

...(more)

Blackbox Manifold 9

_______________________

Idle No More: A chance to repair a sad legacy

Jim Coyle

The truth about stories, says the author and son of a Cherokee Thomas King, is “that that’s all we are.”

It’s a notion at least as old as the Psalms. “We spend our years as a tale that is told.” And in our lifetimes, we’re shaped and guided by the stories we hear about who we are, where we come from, what we might be.

But stories can also be dangerous, King said in his Massey Lectures of 10 years ago. “So you have to be careful with the stories you tell. And you have to watch out for the stories you are told.”

As much as anything, Idle No More — born of a rally organized in Saskatoon in November by four aboriginal women — seems to be an attempt by Canada’s First Nations to insist that their story be reclaimed and heard, to galvanize their people and the wider public into addressing a long-standing national disgrace.

To get lost in the diet particulars of one hunger-striking chief in Ottawa, or the accounting idiosyncracies of one reserve’s band council, or a decision in Attawapiskat by a people grown wary of media to ban a TV crew, is to miss the larger and legitimate point of Idle No More and the opportunity it presents for essential change....(more)

The Toronto Star's Idle No More collected posts Idle No More: Songs for Life Vol. 1

_______________________

The Power of Positive Publishing

How self-help ate America.

Boris Kachka

(....)

This plague of usefulness has burrowed its way into the types of books that were traditionally meant to enlighten, or entertain, or influence policy, but not exactly to build better selves. It’s generally led to better self-help, more grounded in the facts and narratives that drive the other genres, but also to a nonfiction landscape in which every goal is subjugated to the self-improvement imperative.

This new kind of self-help could never thrive in a vacuum. Or rather, it thrives in a particular vacuum—the one left behind by the disappearance of certain public values that once fulfilled our lives. Strains of self-help culture—entrepreneurship, pragmatism, fierce self-reliance, gauzy spirituality—have been embedded in the national DNA since Poor Richard’s Almanack. But in the past there was always a countervailing force, an American stew of shame and pride and citizenship that kept these impulses walled off, sublimating private anxiety to the demands of an optimistic meritocracy. That force has gradually been weakened by the erosion of all sorts of structures, from the corporate career track to the extended family and the social safety net. Instead of regulation, we have that new buzzword, self-regulation; instead of an ambivalence over “selling out,” we have the millennial drive to “monetize”; and instead of seeking to build better institutions, we mine them in order to build better selves. Universities now devote faculty to fields (positive psychology, motivation science) that function as research arms of the self-help industry, while journalists schooled in a sense of public mission turn their skills to fulfilling our emotional needs. But since self-help trails with it that old shameful stigma, the smartest writers and publishers shun the obvious terminology. And the savviest readers enjoy the masquerade, knowing full well what’s behind the costume: self-help with none of the baggage....(more)

_______________________

footpath near Darnick

Walter Baxter

_______________________

Raw Nerve

a series of pieces on getting better at life.

Aaron Swartz

(November 8, 1986 – January 11, 2013)

#J11: Idle No More

global day of action this Friday Idle No More

Idle No More: A profound social movement that is already succeeding

Judy Rebick

#Idle No More and Settler Colonialism: We Are All Treaty People

Lisa N Guenther

The cultural importance of Idle No More

Duncan McCue

cbc

... for those struggling to understand this movement on a more cultural level, it may be helpful to remember that traditionally, amongst many aboriginal people, the cold days and long nights of winter were a time for storytelling.

And, putting aside the politics and the posturing, storytelling is at the heart of Idle No More, at least as many of those on the inside of this movement see it.

In this case, the storytellers have been mostly young indigenous people — increasingly educated and urban-based — using social media and other digital tools to spread messages of cultural survival and self-determination....(more)

Voices of the Idle No More movementcbc_______________________

Kenojuak Ashevak

(October 3, 1927 – January 8, 2013)

Rainforest defender Rebecca Tarbotton leaves inspiring legacy

David Suzuki

_______________________

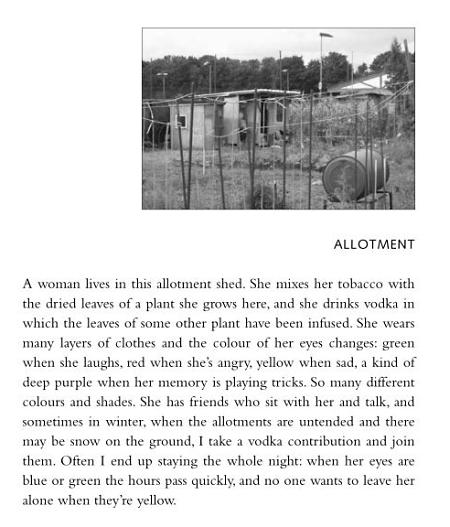

Days and Nights in W12 [pdf]

Jack Robinson

CB editions

_______________________

the psychoanalysis of ruins

Dylan Trigg

3am

Time Out of Joint

How does a ruin — be it the remains of an industrial factory or the relic of an ancient civilization — fit into the landscape of a city? Beyond its warped mass of broken materiality, a ruin is also a disordering of time. It maligns time, dissolving boundaries between past and present. The question is not where the ruin is located, but when? Not in the present, but neither in the past. Time out of joint, to invoke the spectre of Hamlet.

More than this, the ruin undercuts our attachment to places. If there is sometimes a tendency to become overly attached to our little corner in the world, then where that corner is a ruin, such attachment is overrun by constant change. Becoming overly attached to one’s favourite ruin is likely to result in heartbreak. Impossible, after all, to become nostalgic about something that resists a fixed identity. No matter how much we want the ruin to testify to a past of our own — to be one’s own ruin — in the glance of an eye, it assumes a different past, and wholly disconnected to the one we may have incorporated as our own.

Ruins return. This is one of the great surprises that the ruin presents to us: its persistence in time alongside its disordering of time. Far from the waste matter of culture, the ruin always resists repression, finding ways to fend off the very decay that constitutes the ruin in the first instance.

No wonder, then, given this complex structure that Freud elected the ruin to the principle metaphor not only for the practice of psychoanalysis but also for the mind itself. In the archaeological excavation of the ruin, Freud found the means to articulate a set of themes central to his thinking as a whole, not least the very preservation of the past in the mind.

Why the image of the ruin? What can it tell us about psychoanalysis — and equally, what can psychoanalysis tell us about ruins? ...(more)

_______________________

if you disappear

Peter Ciccariello

invisible notes

notes from the inbetween

Christian Rohlfs

d. Jan. 8, 1938

_______________________

Foreign Laughter, Foreign Music

George Szirtes

I did not read Lįszló Krasznahorkai’s Az ellenįllįs melankóliįja (The Melancholy of Resistance) through before starting the translation. I glanced at it. My internal translation engine seems to work best through a kind of visual scratch and sniff method.

(....)

The book rolled slowly over and through me for four years. Four years was two and a half years longer than it should have been. They were four years of frustration, exhaustion and cursing. I cursed the endless sentences, the lack of landmarks that paragraphs might have offered, and, as it sometimes seemed to me, the wilful manner and cosmic ambition of the author. At times the book seemed to be a particularly terrifying example of the kind of elephantiasis that afflicts Hungarian fiction. The smaller the country, I quipped to myself, the greater the ambition. You make up for the lack of language territory by offering sheer verbiage as compensation. Hungary was a small country locked into its isolated language: the prolific energy and ironic earnestness of its authors was their way of battering down the doors to the outside world.

Though little reviewed in England (that is to say it was reviewed briefly albeit with intense pleasure) Susan Sontag and W.G. Sebald put their imprimatura on The Melancholy of Resistance and the critical response in America was henceforth considerably more powerful. The worst that reviewers could find to say about Melancholy was that it was a marvellous book but that it took a little determination to discover that fact. Personally I was enormously relieved to be rid of it, but I found it grew in my head as time went by. It lost its wilfulness, its association with headaches, exhaustion and fury, and while I needed considerable persuasion to set out on a second book by Krasznahorkai I was certain that the pain would be worth it. That book was War and War....(more)

almostisland

_______________________

In Search of a Personal History

Stef Renard

via

(....)

"... The fact that I almost haven't had any contact with my family during the last years makes that even these pictures feel as if they have a distance to me. A lot of people on the pictures remain strangers to me. To fill the void in my personal history I started to take pictures of my surroundings. Not only places that are seen in the pictures I had found but also places that resonate my feelings about our universal history, family life and my personal history."

_______________________

metameat

(....)

Young poets, and poets who refuse to grow up, insist on a principle of possibility or unreality out of fear of pressing on the lever of the real world. Not because they think the lever won’t move. The fear is that it will move just barely, opening the narrowest of cracks. They would then be forced to claim that crack—it’s what you’ve made, the best that was in you—and slide their narrow hearts inside, to beat sideways the rest of their days.

...(more)

_______________________

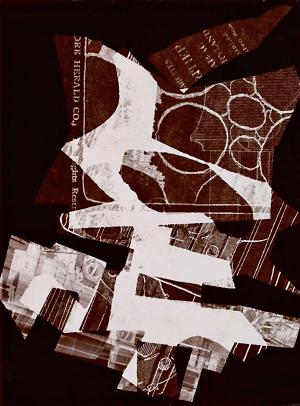

Das Baumerbild

1920

Kurt Schwitters

d. Jan. 8, 1848

_______________________

Late Stage Capitalism and the Shame Haunted Life

You Can't Kill Trauma With A Gun.

Phil Rockstroh

_______________________

MP3: The Meaning of a Format

Jonathan Stern

google books

Although it is a ubiquitous and banal technology, the MP3 offers an inviting point of entry into the interconnected histories of sound and communication in the twentieth century. To access the format's historical meaning, we need to construct a new genealogy for contemporary digital media culture. Many of the changes that critics mark as particularly salient aspects of contemporary digital or “new” media happened in audio before they surfaced in visual media. As Frances Dyson writes, digital media encapsulate “an accumulation of the auditive technologies of the past.” The historical resonance of audio can be extended across thevarious registers of new media, from their sensual dimensions in both the auditory and visual domains, to their treatment of subjects, to their technical structure and industrial form.“

pdf avaiable at Monoskop

_______________________

photo - mw_______________________

Bibliomancy

Miriam Bird Greenberg

42opus

(....)

They are studying bones. They are drawing lots.

They are observing patterns in the

flight of birds.

They are rereading their diaries,

and the diaries of their wives and children. They are reading

last year's newspapers not yet used

as kindling.

Each is carrying a pail,

scooping sleeping water up from the reedy shallows,

shining a light into the bottom of the

bucket

to watch the movement of minnows,

alert for any darting, sudden letters traced in the water,

their fish scales iridescent

in the day's last light.

At dawn they will gather by the well house to interpret

their findings.

...(more)

Lee Friedlander

1 2 3

_______________________

I am unable to stabilize my subject; it staggers confusedly along with a natural drunkenness. I grasp it as it is now, at this moment when I am lingering over it. I am not portraying being but becoming: not the passage from one age to another . . . but from day to day, from minute to minute. I must adapt this account of myself to the passing hour. I shall perhaps change soon, not accidentally but intentionally. This is a register of varied and changing occurrences, of ideas which are unresolved and, when needs be, contradictory, either because I myself have become different or because I grasp hold of different attributes or aspects of my subjects. . . . If my soul could only find a footing I would not assaying myself but resolving myself. Montaigne, Of Repentance, Montaigne's Essays

first published in 1580

_______________________

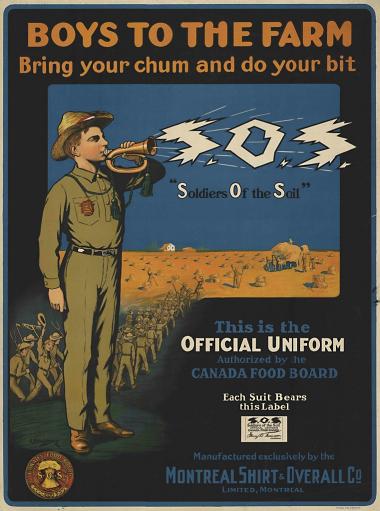

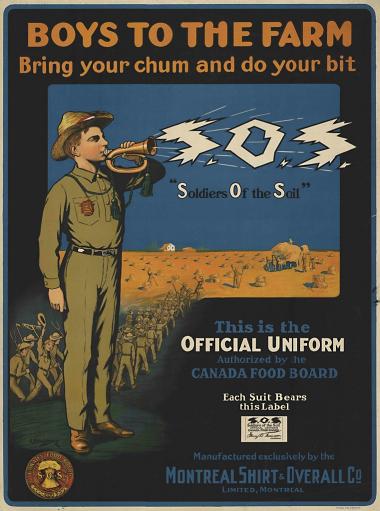

World War One Posters

bibliodyssey

_______________________

“There is contingent being independent of us, and this contingent being has no reason to be of a subjective nature”

Interview with Quentin Meillassoux

(....)Concerning Foucault I will simply answer as follows. His investigation focuses on past dispositives of knowledge-power, and eventually on dispositives that are contemporary to him. He can bring us nothing in regards to the disqualification of strong correlationism, because the disqualification is situated at a level that his research does not address, but rather presupposes. Indeed, I examine how correlationism, from its point of departure in the Cogito, has come to dominate all of modern thought, including the most resolutely anti-Cartesian: the “great confinement” was not that of the fools in the asylum, but that of the philosophers in the Correlate—and this also applies to Foucault. Indeed, Foucault does not say anything that would embarrass a correlationist, as all his comments can easily be considered as a discourse-correlated-to-the-point-of-view-of-our-time, and rigorously dependent on it. This is a typical thesis of some correlationist relativism: we are trapped in our time, not in Hegelian terms, but rather in a Heideggerian fashion—that is to say in the modality of knowledge-power that always already dominates us. His thesis on the “disappearance of man” is about man understood as an object of “human sciences,” not about the correlate as I conceive it....(more)

Meillassoux in English (Bibliography)Paul J. Ennis

_______________________

The Problems Of Philosophy

Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

3quarksdaily

An existentialist, a modal realist, and an eliminative materialist walk into a bar; the bartender looks up at them and says, “Is this a joke?” ...(more)

_______________________

Shadow play

circa 1919

Harold Cazneaux

1878 - 1953

_______________________

Spoiling Old Stonework

A Glasgow Story

Alasdair Gray

Until the 1960’s a big wasteland lay between Sighthill Cemetery and the Monkland Canal, east of Port Dundas and west of Springburn Road. The earth was polluted by waste from a factory on Springburn Road originally owned by Tennents, then by Imperial Chemicals Ltd. This interesting district also held railway sidings, a slaughter house, a scummy green lake called the Stinky Ocean by local children because it exuded sulphurous fumes, and a steep slagbing they called Jack’s Mountain. On the summit of a natural hill by the canal was a fence of vertical railway sleepers surrounding a squat brick circular tower. This was about ten feet high and sometimes sent up puffs of smoke. The tower was hollow and shielded a vent from a railway tunnel under the hill. The smoke was from steam engines pulling trains from Buchanan Street station to Oban, Edinburgh or Dundee.

...(more)

_______________________

The Image

My tongue fills my mouth with mud a last resource takes it in and turns the mud around in the mouth question if swallowed would it nourish and opening up of vistas without having to swallow often they are not bad moments to spend everything there rosy in the mud the tongue lolls out again and what are the hands at all this one time one must always try and see what the hands are at well the left as we have seen still clutches the sack and the right well the right after a moment at the end of its arem full stretch in the axis of the clavicute as it might be said or rather opening and closing in the mud opening and closing it's another of my resources this little movement helps me I don't know why I have little tricks like that which are a good resource even following the wall under the changing sky .....

As The Story Was Told - Uncollected and Late Prose

Samuel Beckett

pdf available at aaaaarg (free reg. req.)

_______________________

First as Tragedy, Then as Farce

RSA Animate

photo - mw

_______________________

Anthropoetics XVIII, no. 1

Journal of Generative Anthropology

Fall 2012

A linguistic source for the myth of the Summum Bonum, and how it should be played

Edmond Wright

(....)

Plato and Aristotle differ as regards the path to this highest good. For Plato, as for Socrates, the guide to it, implied in the assumption of godlike omniscience, is knowledge, knowledge of the rational and its systematic order. For Aristotle, mere knowledge as such was insufficient—it had to be braced with action, virtuous action in accordance with our engagement with ethical challenges in practice. But both projected knowledge and virtue are seen as aiming at a finally achievable Good for both citizen and city. Thomas Aquinas identified the final Good with God in whom every soul’s desires would find the happiness of satisfaction. Immanuel Kant interlocked the belief in God with a moral order that issued in a summum bonum. The Utilitarians identified it with the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Some modern economists view it as the putative goal of happiness for the Rational Individual.

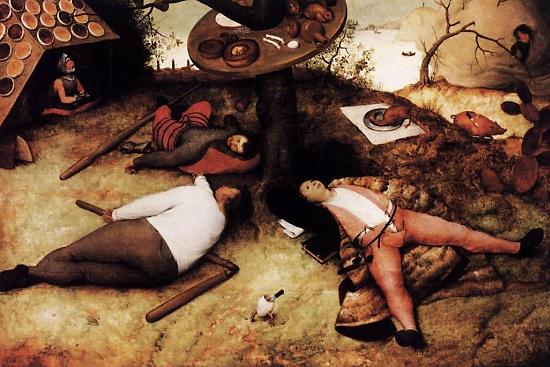

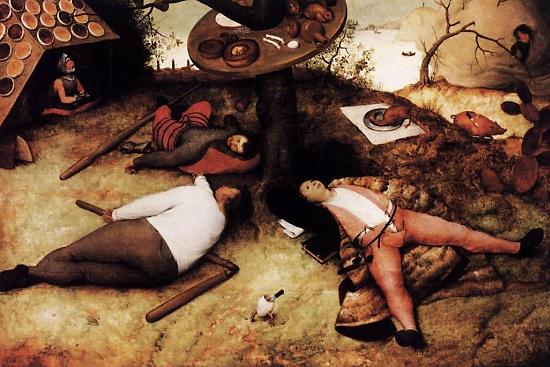

Then there are political forms of it. Take the utopianism of the vulgar Marxists, or more degenerate forms such as evidenced by the stupor of the drunkards in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s satirical painting "The Land of Cockaigne," or the extreme right-wing in Greece at the moment, calling their party "Golden Dawn," or worse, Anders Breivik’s myth of a future Norway, racially pure.

What can such ethical analyses have to do with language? Does it not seem blasphemous to trace the holiest of aims to a feature of human communication? It seems to some as just another covert attempt at a reduction of the sacred by means of rational explanation, an Enlightenment ploy typical of the aggressive atheism that has emerged over the past decade? Worse, it looks as if such a claim lays itself open to the accusations of relativism and solipsism, and so can be summarily dismissed as covertly importing the anarchy of "postmodernism."...(more)

_______________________

The Land of Cockaigne

Brueghel, Pieter the Elder

1567

_______________________

David Graeber: On the Creation and Maintenance of Hopelessness

"The last 30 years have seen the construction of a vast bureaucratic apparatus for the creation and maintenance of hopelessness, a giant machine designed first and foremost to destroy any sense of possible alternative futures. At its root is a veritable obsession on the part of the rulers of the world - in response to the upheavals of the 60's and 70's - with ensuring that social movements cannot be seen to grow, flourish or propose alternatives. That those who challenge existing power arrangements can never under any circumstances can never be seen to win. Maintaining this illusion requires armies, prisons, police and private security firms to create a pervasive climate of fear, jingoistic conformity and despair. All these guns, surveillance cameras and propaganda engines are extraordinarily expensive and produce nothing — they're economic deadweights that are dragging the entire capitalist system down."

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

David Graeber

via

_______________________

Poems by Heiner Mueller [pdf]

Translation: Dennis Redmond

Pictures

Pictures signify everything in the beginning. Are keepable. Roomy.

But the dreams congeal, become form and disillusionment.

Already the sky holds no more pictures. The clouds, seen from an

airplane: steam which takes away the view. The crane only a bird.

Even Communism, the final picture, which is always refreshed

Because washed with blood again and again, the everyday

Pays it out with small coins, unshiny, blind with sweat

Ruins, the great poems, like bodies, long loved and

No longer needed now, on the way to the much-used final species.

Between the lines a wailing

on bones the stone-bearer happy

For the Beautiful signifies the possible end of Horror.

_______________________

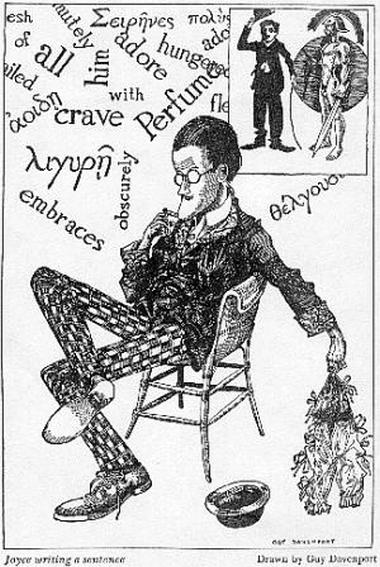

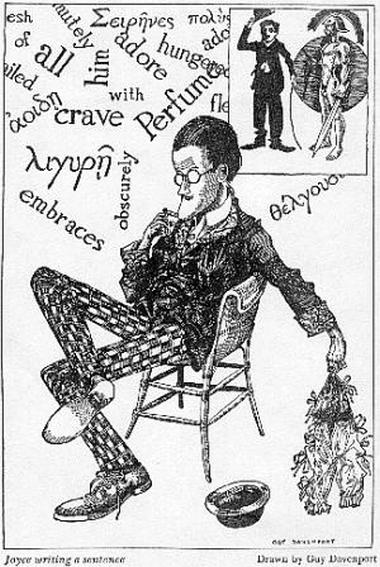

Guy Davenport

d. Jan. 4, 2005

Wittgenstein did not argue; he merely thought himself into subtler and deeper problems The record which three of his students have made of his lectures and conversations at Cambridge discloses a man tragically honest and wonderfully, astoundingly absurd. In every memoir of him we meet a man we are hungry to know more about, for even if his every sentence remains opaque to us, it is clear that the archaic transparency of his thought is like nothing that philosophy has seen for thousands of years. It is also clear that he was trying to be wise and to make others wise. He lived in the world, and for the world. He came to believe that a normal, honest human being could not be a professor. It is the academy that gave him his reputation of impenetrable abstruseness; never has a man deserved a reputation less. Disciples who came to him expecting to find a man of incredibly deep learning found a man who saw mankind held together by suffering alone, and he invariably advised them to be as kind as possible to others. He read, like all inquisitive men, to multiply his experiences. He read Tolstoy (always getting bogged down) and the Gospels and bales of detective stories. He shook his head over Freud. When he died, he was reading Black Beauty. His last words were: "Tell them I've had a wonderful life."

—

Guy Davenport, The Geography of the Imagination

Guy Davenport on Wittgenstein

Guy Davenport: the writer as cartoonistJeet Heer

Davenport drawing

from Hugh Kenner’s The Counterfeiters

The Counterfeiters: An Historical Comedy

Hugh Kenner, Guy Davenport

The Geography of the Imagination: Forty Essays

Guy Davenport

“The Renaissance of 1910”:

Reflections on Guy Davenport’s Poetics

Marjorie Perloff

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

The Luckless Angel

Heiner Mueller

Translation: Dennis Redmond

Behind him swims the past, shaking thunder from wing and shoulder, with a noise like buried drums, while before him the future jams up, his eyes pressed in, the eyeballs explode like a star, the word wound up into a vibrating mouthgag, strangling him with his breath. For a long time one still sees his wings beating, hears in the roaring the hail of stones fall down before over behind him, the louder the more violent the movement in vain, scattered, when they become slower. Then the moment closes over him: on the quickly rubble-filled standing place the luckless angel comes to rest, waiting for History in the petrification of flight breath glance. Till the renewed roaring of mighty wing-beats reproduces itself in waves through the stone and indicates his flight.

thanks Robert

Sur la trace du renard

Louis Perreault

_______________________

Ben Lerner and the administration of fear

Mark Thwaite

ReadySteadyBook

Paul Virilio says the title of his book The Administration of Fear "sprang to mind right away as a direct echo of the title of Graham Greene's well-known book, The Ministry of Fear... I use the expression "administration of fear" to refer to two things. First, that fear is now an environment, a surrounding, a world. It occupies and preoccupies us... [it] also means that States are tempted to create policies for the orchestration and management of fear... When I read Graham Greene's book, I found the expression "ministry of fear" to be particularly well chosen because it carries the administrative aspect of fear and describes it like a State."

Fear, then, is a product of the State, part of the modern mood; something the State contributes to, sustains and extends through its activities - and often especially through the activities it pursues to counter fear's epiphenomena. The administration of fear, then, is the administration of fear that the State causes and makes perpetual by its actions. The administration of fear pace Graham Greene is a Catch-22 situation.

Asked by his interlocutor Bertrand Richard "isn't it inappropriate to use the same expression for both the tragic historical events of the Second World War and what we Westerners are experiencing today," Virilio replies that he does not think so. A brief discussion of Hannah Arendt and an overview of his dromology, his politics of speed, is followed by a fascinating thought: when "Henri Bergson, the theorist of duration, and Albert Einstein, the inventor of relativity" met in Paris (in April 1922) they were not able to understand one another - a unique rendez vous, a moment of fate, happened but did not take place. Science became part of the "military industrial complex" and philosophy failed to think a political economy of speed....(more)

_______________________

Work, Learning and Freedom

Noam Chomsky and Michael Kasenbacher

(....)How do you think it is possible in our society, not just in education, for people to counteract all this structuring, this tendency for us to be driven into situations where people don't know what it is they want to do?

I think it's the opposite: the social system is taking on a form in which finding out what you want to do is less and less of an option because your life is too structured, organised, controlled and disciplined. The US had the first real mass education (much ahead of Europe in that respect) but if you look back at the system in the late 19th century it was largely designed to turn independent farmers into disciplined factory workers, and a good deal of education maintains that form. And sometimes it's quite explicit - so if you've never read it you might want to have a look at a book called The Crisis of Democracy - a publication of the trilateral commission, who were essentially liberal internationalists from Europe, Japan and the United States, the liberal wing of the intellectual elite. That's where Jimmy Carter's whole government came from. The book was expressing the concern of liberal intellectuals over what happened in the 60s. Well what happened in the 60s is that it was too democratic, there was a lot of popular activism, young people trying things out, experimentation - it's called 'the time of troubles'. The 'troubles' are that it civilised the country: that's where you get civil rights, the women's movement, environmental concerns, opposition to aggression. And it's a much more civilised country as a result but that caused a lot of concern because people were getting out of control. People are supposed to be passive and apathetic and doing what they're told by the responsible people who are in control. That's elite ideology across the political spectrum - from liberals to Leninists, it's essentially the same ideology: people are too stupid and ignorant to do things by themselves so for their own benefit we have to control them. And that very dominant ideology was breaking down in the 60s. And this commission that put together this book was concerned with trying to induce what they called 'more moderation in democracy' - turn people back to passivity and obedience so they don't put so many constraints on state power and so on. In particular they were worried about young people. They were concerned about the institutions responsible for the indoctrination of the young (that's their phrase), meaning schools, universities, church and so on - they're not doing their job, [the young are] not being sufficiently indoctrinated. They're too free to pursue their own initiatives and concerns and you've got to control them better.

If you look back at what happens since that time there have been a lot of measures introduced to impose discipline. Take something as simple as raising tuition fees - it's much more true in the US than elsewhere, but in the US tuition is now sky high - in part it selects things on a class basis but more than that, it imposes a debt burden. So if you come out of college with a big debt you're not going to be free to do what you want to do. You may have wanted to be a public interest lawyer but you're going to have to go to a corporate law firm. That's quite a serious fact and there are many other things like it. In fact the drug war was started mainly for that reason, the drug war is a disciplinary system, it's a way of ensuring that people are kept under control and it was almost consciously designed that way... The idea of freedom is very frightening for those who have some degree of privilege and power and I think that shows up in the education system too. And in the workplace... for example, there's a very good study by a faculty member here, who was denied tenure unfortunately, who studied very carefully the development of computer controlled machine tools - first developed in the 1950s under the military where almost everything is done......(more)

_______________________

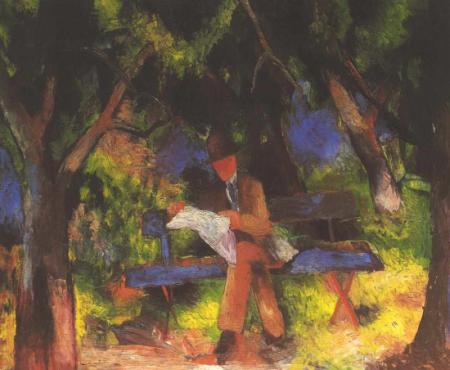

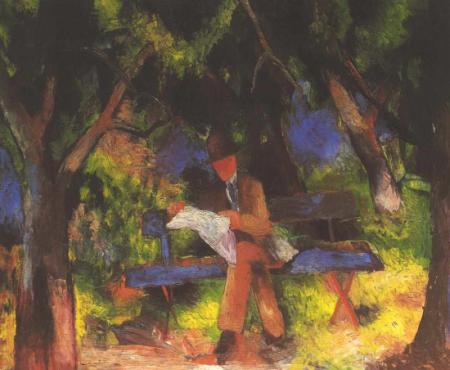

August Macke

b. Jan. 3, 1887

_______________________

The Soul of Student Debt

Chris Maisano

jacobin

(....)

The leading intellectual lights of the Occupy movement have seized on the issue of debt as their leitmotif, organizing their analysis of the economy around what they’ve taken to calling the “debt system.” For them, the explosion in personal and public indebtedness that has occurred over the last three decades represents a break in the logic of capitalism and marks the revival of older forms of exploitation associated with feudalism. At an Occupy conference held shortly after the clearing of Zuccotti Park, David Graeber made the case succinctly:

I think there’s a fundamental shift in the nature of capitalism, where some people are still using a very old-fashioned moral logic, but more and more people are recognizing what’s really going on. They just don’t know the extent of it. It’s not even clear that this is capitalism anymore. Back when I went to college, they taught me that the difference between capitalism and feudalism. In feudalism they take the money directly, through legal means, and they just shake you down, pull it out of your income, and in capitalism they take it through the wage, in these subtle ways. It seems like it’s shifting more toward the former thing. The government is letting these guys bribe the government to make laws where they can pick your pocket, and that’s pretty much it.

Graeber is certainly correct to point out the ways in which debt and finance can be nakedly exploitative. Marxists have traditionally characterized capitalist exploitation as an abstract social process that takes place behind the backs of those it exploits. But there’s nothing indirect about a credit card or student loan bill. All of those seemingly extraneous charges and fees are right in front of you on your bill, chipping away at your income and your standard of living month after month for years on end.

Still, that’s not “pretty much it.” The critique of debt as neo-feudalism advanced by Graeber, the organizers of the Strike Debt campaign, and others fails to capture how debt and finance works under contemporary capitalism. It also echoes the misguided populist discourse that casts the financial sector as a parasitical growth on the productive, “real” economy. In the case of student debt, the neo-feudal argument also prevents us from properly understanding one of the main functions of debt and finance within neoliberal capitalism: the shaping of our economic souls. The social function of student debt is not to make us into serfs or indentured servants. It’s to teach us how to be investors and risk-takers, entrepreneurs who have taken on debt to finance our climb up the ladder of bourgeois success. The soul of student debt is not feudal, but capitalist through and through....(more)

_______________________

Café Figaro

Jack Levine

b. Jan. 3, 1915

_______________________

Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy, No. 13:

Special Issue on Affect

(2011)

available at Monoskop

from the editors’ introduction

(....)

Taking the “turn” as narrowly defined, the “affective turn” is a phenomenon located outside the ongoing traditions of philosophy even as it draws from them. This conclusion is implied by the “turn” itself: the list of vectors which orient the “turn” note several identifiable traditions of philosophy which feed into the “turn” both from a place outside (i.e. separate traditions of philosophy) and before (i.e. traditions which predate the “turn’s” beginning in the mid-1990s). Philosophy has long been interested in affect and has been affected in turn: since ancient times philosophers explored wonder, love, desire, anger, lust, joy, melancholy, hate, sadness, and later anxiety, shame, anguish and many others. The essays in this issue take this detailed discussion of the affects as well as their theorisation further.

This collection of essays speaks to the theme of affect and will do so from within the broad and inclusive array of contemporary Continental Philosophy. In this sense these essays are part of, and celebrate, the “affective turn,” broadly defined. But the essays also speak to the “affective turn” and in doing so adopt a critical distance from it.

(....) _______________________

No Art

Ben Lerner

Tonight I can't remember why

everything is permitted or,

what amounts to the same thing,

forbidden. No art is total, even

theirs, even though it raises

towers or kills from the air,

there's too much piety in despair,

as if the silver leaves behind

the glass were politics

and the wind they move in

and the chance of scattered

storms. Those are still

my ways of making ......(more)

_______________________

Postcolonial Text

Vol 7, No 3

Bewildered

Bruce Oakman

Indigenous Art, Ian Potter Centre, National Gallery of Victoria,

Federation Square, Melbourne.

I abandon the hunt for answers, yield

to an absence of horizons,

geometric perspectives,

am hypnotised by unfamiliar patterns,

dots, not-to scale traceries of tracks

of mythical creatures, and

bewildered

I think of the ancestors

who encountered strangers with muskets,

clocks, voracious beasts, white papers

stained by black ink, before

the dreaming was fractured,

the women and waterholes sullied,

the eternal songlines strained with wire.

_______________________

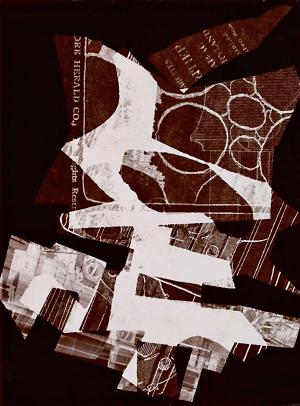

Schadograph

Christian Schad

1918

Inventing Abstraction

1910-1925

MoMA

via

_______________________

Ten activist success stories from 2012

and some tools to recreate them

rabble

Helsinki

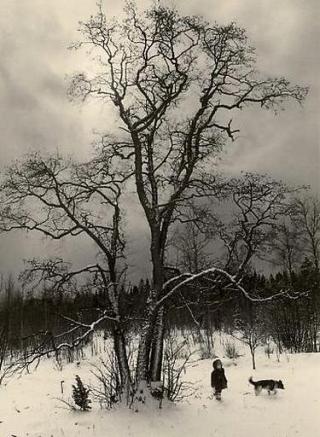

Pentti Sammallahti

2002

1 2 3 4 5 6

_______________________

Journal of Social Inclusion

Vol 3, No 2 (2012)

_______________________

'I've Got Nothing to Hide' and Other Misunderstandings of Privacy

Daniel J. Solove

social science research network

Abstract:

In this short essay, written for a symposium in the San Diego Law Review, Professor Daniel Solove examines the nothing to hide argument. When asked about government surveillance and data mining, many people respond by declaring: "I've got nothing to hide." According to the nothing to hide argument, there is no threat to privacy unless the government uncovers unlawful activity, in which case a person has no legitimate justification to claim that it remain private. The nothing to hide argument and its variants are quite prevalent, and thus are worth addressing. In this essay, Solove critiques the nothing to hide argument and exposes its faulty underpinnings.

_______________________

old Moscow

Ilya Ilf

1920s

Poemas del rķo Wang

_______________________

Mass:

raw poetry from the commonwealth of Massachusetts

edited by

Jim Dunn and Kevin Gallagher

jacket2

_______________________

Talking about New Orleans

Jayne Cortez

(May 10, 1936 - December 28, 2012)

About deforestation & the flood of vodun paraphernalia

the Congo line losing its Congo

the funeral bands losing their funding

the killer winds humming intertribal warfare hums into

two storm-surges

touching down tonguing the ground

three thousand times in a circle of grief

four thousand times on a levee of lips

five thousand times between a fema of fangs

everything fiendish, fetid, funky, swollen, overheated

and splashed with blood & guts & drops of urinated gin

in syncopation with me

riding through on a refrigerator covered with

asphalt chips with pieces of ragtime music charts

torn photo mug shots & pulverized turtle shells from Biloxi

me bumping against a million-dollar oil rig

me in a ghost town floating on a river on top of a river

me with a hundred ton of crab legs

and no evacuation plan

me in a battered tree barking & howling with abandoned dogs

my cheeks stained with dried suicide kisses

my isolation rising with a rainbow of human corpse &

fecal rat bones

where is that fire chief in his big hat

where are the fucking pumps

the rescue boats

& the famous coalition of bullhorns calling out names

hey I want my red life jacket now

& I need some sacred sandbags

some fix-the-levee-powder

some blood-pressure-support-juice

some get-it-together-dust

some lucky-rooftop-charms &

some magic-helicopter-blades

...(more)

_______________________

January 2013: Writing from Haiti

Words without Borders

Under the Rubble

Guy-Gerald Ménard

Translated from Haitian Creole by Chantal Kenol

(....)

Clocks are unwinding

under life’s rubble

our voices engraved on text messages

a colony of ants bring us news

daredevils armed with shovel

and pickax

scrape gravel with fingernails

faithfully, block after block

hope pursues a hunchbacked miracle

at the end of a tunnel

...(more)

_______________________

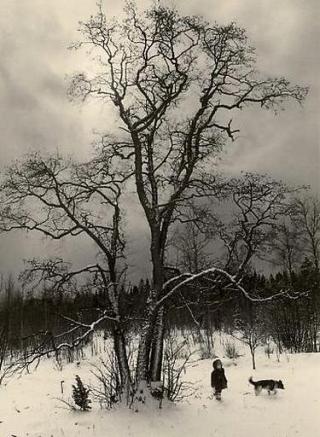

Finström, Finland

Pentti Sammallahti

1981

_______________________

Summa contra juxta Gentiles

Ray Davis

(....)

... honest attention to sensibility finds social context inseparable from sensation. Words have heft; the color we see is a color we think. And art(-in-the-most-general-sense-possible) wins special interest as a sensible experience which is (more or less) bounded, shared, repeatable, and pre-swaddled in discourse.

Pluralism is mandated by that special interest. Any number of functions might be mapped into one chunk of multidimensional space. Integer arithmetic and calculus don't wage tribal war; nor do salt and sweet. We may not be able to describe them simultaneously; one may feel more germane to our circumstances than another; on each return to the artifact, the experience differs. But insofar as we label the experiential series by the artifact, all apply; as Tuesday Weld proved, "Everything applies!" And as Anna Schmidt argued, "A person doesn't change because you find out more." We've merely added flesh to our perception, and there is no rule of excluded middle in flesh.

Like other churches, this one doesn't guarantee good fellowship, and much of the last decade's "aesthetic turn" struck me as dumbed-down reactionism. But The New Aestheticism was on the whole a pleasant surprise....(more)

|