|

photo - mw

_______________________

Wynd

Andrew Greig

It’s back again, the how of rain

pleating off leaky roans, binding

strands that curve down stanks, curl

by high-walled wynds and dreels,

past sweetie shops with one faint bulb,

bell faltering as the pinnied widow

shuffles through from her back room –

What can I do for you the day?

She hands me now

no Galaxy or Bounty Bar

but a kindly, weary face, smear

of lipstick for her public, the groove

tartan slippers wore in linoleum

from sitting-room to counter, over thirty years:

the lost fact of her existence.

...(more)

Andrew Geig at

Poetry International Web and interviewed at Quercus Books

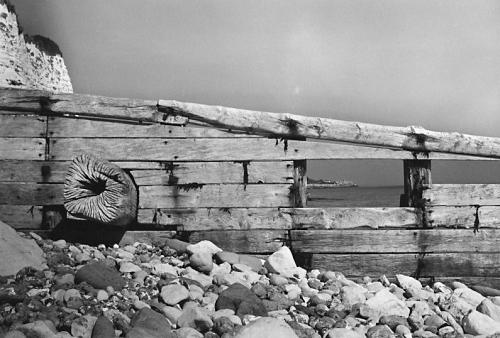

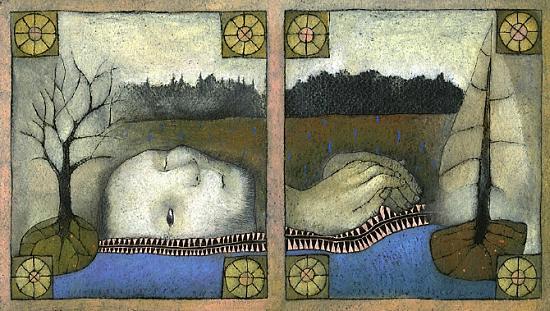

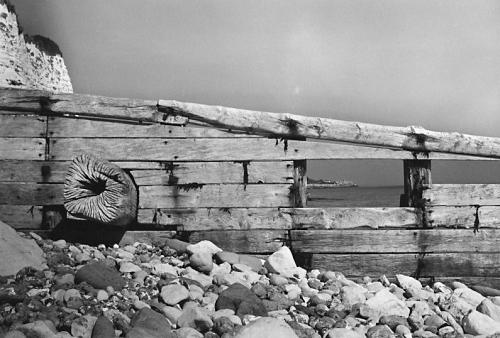

Martin O’Donnell’s Boat

Alice Myers

Best Scottish Poems 2011

The Scottish Poetry Library

_______________________

‘Writ in Water’ – Shelley, Byron, Keats and the Italian Sea

Nicoletta Asciuto

Did sea define the land or land the sea?

This is the question Seamus Heaney asked himself back in the Sixties while standing on the wild, sea-tormented coasts of the Aran Islands, which have challenged proudly the Atlantic Ocean and its endless waves from time immemorial.

I always think of this line by Heaney when going back in mind to the Golfo dei Poeti, that is, the Poets’ Gulf, in Liguria, Italy. Liguria is very famous for its gulfs but the Poets’ Gulf is possibly the most closed and the most embracing of all, seeming in its smallness almost a lake – if not for a little break right where the two ends should meet. Was it the land that stretched endlessly towards the sea and managed to impose itself on it? Or was it the sea that broke the land and took partial possession of it?...(more)

The Literateur

_______________________

"The answer lies not in repeating lost gestures, methods and sounds or calling for a failed utopianism, but in rethinking the very possibility of the lostness of that temporality itself."

Against All Ends: Hauntology, Aesthetics, Ontology

Liam Sprod 3:am

Although it is already old, considering hauntology as either genre, aesthetic or zeitgeist is problematic; and is so for precisely all of the reasons that it claims to be each of these things. As nostalgia for lost futures or mourning for utopia, it falls into for the exact problems of utopianism that lead to its initial loss. It is also these problems that hauntology was developed to overcome, so its reduction precisely to them is somewhat ironic, if not cause for yet another mourning. Thus through exploring the way in which hauntology has been co-opted by the over-theoretisation of music, and indeed art more generally, in such a way that repeats these problems, I will also show the way for a return to hauntology as a solution to these problems and the affirmation of a more radical thinking for the future.

This path will also necessitate a return to the origin of the word hauntology in the work of Jacques Derrida; an origin that has often been maligned and marginalised in the subsequent use of the term — a parricide that foreshadows the return of the betrayed father. The necessary key to approaching Derrida and the nature of hauntology can be found in Simon Critchley’s observation that “Derrida will tirelessly insist, the closure is not the end and he persistently places himself against any and all apocalyptic discourses on the end (whether the end of man, the end of philosophy, or the end of history)”. It is in light of this opposition to all ends that hauntology should be considered....(more)

_______________________

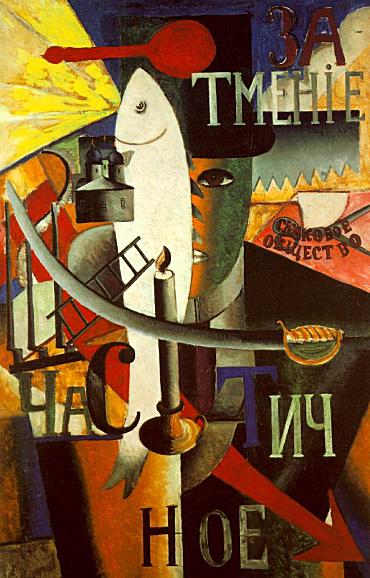

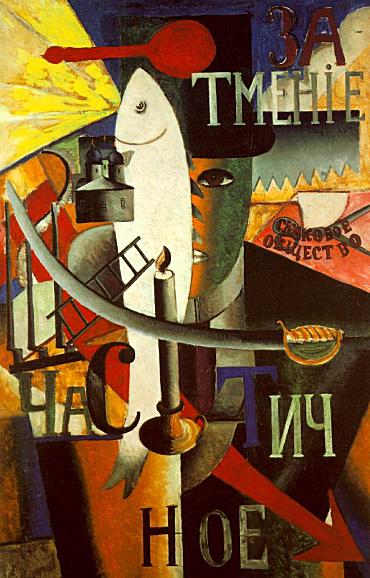

An Englishman in Moscow

1914

Kasimir Malevich

d. May 15, 1935

_______________________

From Biopower to Psychopower

Bernard Stiegler's Pharmacology of Mnemotechnologies

Nathan Van Camp

ctheory

(....)... despite Foucault's pronounced intention to shift the focus of his research to technologies of self-formation that would enable subjects to regain a certain amount of autonomy in the face of modern power mechanisms, this aspect of his work has been largely neglected in recent radical political theory. Although it is now widely recognized among critical theorists that Foucault's work needs serious revisions for relevance in today's context, few have yet taken serious interest in the conclusions that should have to be drawn from his announcement at the Vermont seminar. On the contrary, many of those who claim to be still working in a Foucauldian spirit simply assume that it is his famous concept of biopower that requires renewed attention....(more)

_______________________

The Aesthetic Politics of Affect

Todd Cronan reviews The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigwort

NONSITE

republished from Radical Philosophy March/April 2012

(....)

(Lauren) Berlant’s analysis focuses on the moment in the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts in which Marx describes the “abolition of private property” as signaling the “emancipation of all human senses”. No longer seeing objects as fetishes and nature as a matter of use, the senses, Marx says, become “theoreticians”. Berlant draws on this passage in Marx to understand John Ashbery’s untitled send-up of the American Dream. According to Berlant, “our senses are not yet theoreticians because they are bound up by the rule, the map, the inherited fantasy, and the hum of worker bees who fertilize materially the life we are moving through”. The problem, for Berlant, is the suburban fantasy “of the endless weekend,” the “consumer’s happy circulation in familiarity,” and the “privilege of being bored with life”. (Gregg’s essay similarly takes up the regressive “politics of the cubicle”.) As a reading of Ashbery this might be right, but as an account of Marx, it isn’t. For Marx, of course, the problem is the privilege of private property, not the “privilege of being bored.” One could safely eradicate boredom, without it bearing on the problem of capital. The anxious worker, after all, lacks (and perhaps looks forward to) the privilege of being bored. And affects, despite their “sensorium-shaking” transformation of the “bourgeois senses”, begin to look a lot like the fetishized private property Marx scrutinized. Affects are, Berlant insists, “radically private, and pretty uncoded”, and like the fetishized commodity, they make their dazzling appearance with the labor behind them obscured. These private experiences are in fact beyond analysis—an affect, after all, “is just a fact”....(more)

via the page

_______________________

Open Journal of Philosophy

Vol.2 No.1 2012

The Post-Modern Mind. A Reconsideration of John Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” (1975) from the Viewpoint of an Interdisciplinary History of Ideas

Roland Benedikter, Judith Hilber

Scientific Research Publishing

an academic publisher of open access journals. It also publishes academic books and conference proceedings. SCIRP currently has more than 200 open access journals in the areas of science, technology and medicine.

_______________________

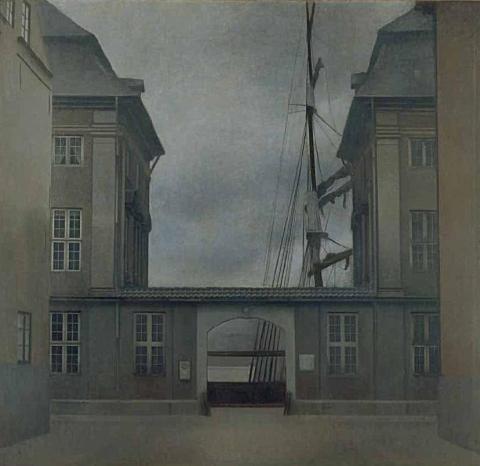

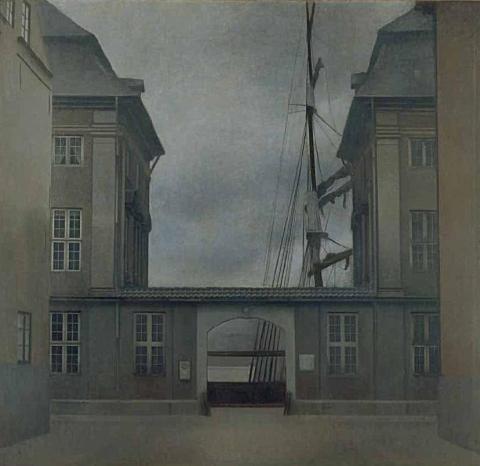

The Asiatic Company Buildings

1902

Vilhelm Hammershųi

b.15 May 1864

_______________________

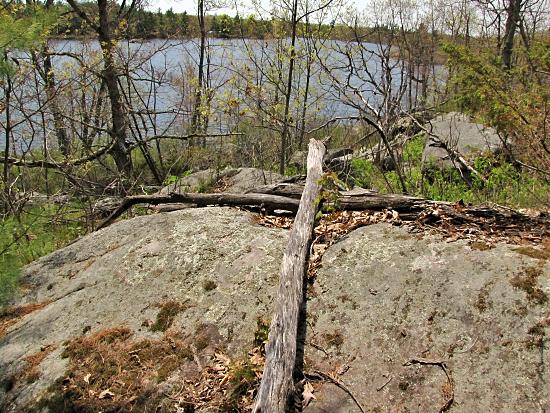

Agosti

D. E. Steward

agni

(....)

Hiking back out, five spruce grouse appear trailside from the brush

The males with their black throats and breasts, high-style elegant

Matter-of-fact confidence in their peck and search, peck and peer and scratch, search and mince ahead

The gallinaceous manner of quail, partridges, grouse, turkeys, jungle chickens, tinamou, pheasants, Guinea fowl is satisfying to encounter, anywhere

In their ur-domesticated chicken ways as self-contained, and as amazing, as moose and their intelligence

Back toward town three hundred meters away across French Lake, a huge solitary bull with the stolid dignity of a full rack

When a big bull moose goes into its lofty trot across a pasture or woodlot opening it has a riveting command

Down from French Lake into Chéticamp along the Gulf, the wharves and fish houses, the harbor itself once cod-rich now mostly a port for whale-watch tours

The Governor-General, Chinese born, will arrive soon for an Acadian lunch, community tour, schmoozing in French and English

Acadians deal with bilingualism well, taking it in the natural order of things, not as a cause like nationalistic Québecois

North of its cities Canada becomes tunicate degrees of isolation

...(more)

Also by D. E. Steward

Juino

Maggiot

Oktombro

Augustos

south of Kaladar

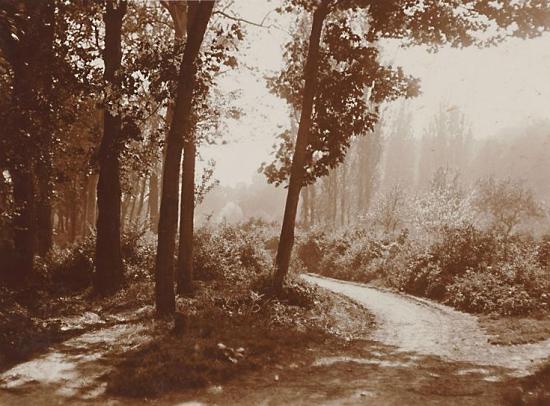

Sheffield Conservation Area

photo - mw

_______________________

A Disturbance of Reality

Dylan Trigg

Side Effects

“One would suppose, then,” so Freud writes in his essay on the uncanny “that the uncanny would always be an area in which a person was unsure of his way around: the better oriented he was in the world around him, the less likely he would be to find the objects and occurrences in it uncanny.” Freud alerts us to the relationship between orientation and uncanniness. At stake in this relation is not only the issue of finding one’s way around in a geometrical or strictly spatial sense. Rather, the experience of being disorientated carries with it a loss of homeworld, and thus the emergence of uncanny angst. The world becomes uncanny precisely through being disoriented. If disorientation coincides with uncanniness, then can we readily infer the opposite; namely, that being orientated means being “at-home”?

To be “at-home.” In one clear sense, this ontological achievement has the advantage of establishing a centre of being in a contingent world. Perhaps this centre is not the physical locality of the house, as it would be for the agoraphobic patient, but instead an experience defined by the body. Either way, the home and the centre entwine, such that one knows where one is, even—especially—if one is in an alien landscape. In this respect, orientation attains a level of homeliness, insofar as it produces a familiar world. The world is familiar insofar as it can be placed—indeed, insofar as it has a place at all.

...(more)

_______________________

Tribe of Palaeopithecus

Jiang Tao

Translation by Brian Holton

the forest was filled with fallen fruit, a scarlet carpet

whose origin lay in geological change

the waters had receded, the tiger’s sabre tooth was rotten

around the empty ground we discussed the future

the old ones had just crawled out from evolution, waving their old fists

the young ones could no longer hold their tongues, they’d got to be the first

to eat the sika deer: ambition to move a mountain lacking

though they could ford the river, north and south

the fields were just a dining table

the so-called republic too rumbustious

nevertheless autumn’s despotism drove off mosquitoes and flies

fortunately we were all standing upright

...(more)

Modern Poetry in Translation

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Declaration (2012)

Michael Hardt, Antonio Negri

pdf available at Monoskop/log

This is not a manifesto. Manifestos provide a glimpse of a world to come and also call into being the subject, who although now only a specter must materialize to become the agent of change. Manifestos work like the ancient prophets, who by the power of their vision create their own people. Today's social movements have reversed the order, making manifestos and prophets obsolete. Agents of change have already descended into the streets and occupied city squares, not only threatening and toppling rulers but also conjuring visions of a new world. More important, perhaps, the multitudes, through their logics and practices, their slogans and desires, have declared a new set of principles and truths. How can their declaration become the basis for constituting a new and sustainable society? How can those principles and truths guide us in reinventing how we relate to each other and our world? In their rebellion, the multitudes must discover the passage from declaration to constitution. .....................................................

On Hardt and Negri’s “Declaration”

Nick Mirzoeff

So Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have published a Declaration regarding the global social movements of 2011 and their implications. If you’ve followed their trilogy from Empire to Commonwealth, there are not too many surprises here but, as ever, some great formulations. Perhaps most usefully they can serve as the lightning rod for the debate over parties and leadership (they’re against) and in starting a new discussion over “commoning.”

(....)

In an early formulation that they return to often, Hardt and Negri (HN) quote Ralph Ellison’s invisible man:

“Who knows,” Ellison’s narrator concludes, “but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” Today, too, those in struggle communicate on the lower frequencies, but, unlike in Ellison’s time, no one speaks for them. The lower frequencies are open airwaves for all. And some messages can be heard only by those in struggle.

This eloquently speaks to the sense that the social movements articulate in murmurs that cannot be heard by self-declared elites and in media that are not known to them.

To explore these frequencies HN use four main figures:

<I>the indebted, the mediatized, the securitized, and the represented. ...(more)

Occupy 2012

A daily observation on Occupy

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

My Sister is a Road Map

Andrew Cothren

My sister Anna is a road map of Indiana. On the day my parents brought her back from the hospital, she was folded up and swaddled in light blue blankets, and she smelled like talcum powder and ink. I held her for the first time on the living room couch. As she squirmed awkwardly in my arms I placed my ear on the city of Marion and could hear her heartbeats: soft, crinkling echoes in her paper chest. She began to cry, her surface warping with wetness, and our mother quickly took her from me and cradled her on the back porch, letting the sunlight slowly wick the moisture away, rocking her to sleep.

Growing up, we’d spend hours in the woods behind our house, lifting large rocks, gathering the salamanders and beetles from the damp soil underneath. Anna would fold up one of her corners into a little paper pocket, where we’d hide all the small creatures we could. We snuck them past our parents and kept them in old shoeboxes under our beds, carefully placing leaves and sticks inside and poking holes in the lids with a pair of safety scissors. In spite of our care, our small pets would always end up stiff and lifeless among the dirty clothes in the laundry basket....(more)

Drunken Boat Spring 2012

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Anticipate Doom:

The Millions Interviews Lįszló Krasznahorkai

translated by George Szirtes

(....)

What I can’t forget is the world we have created. Everything is of equal interest in the world except man himself. When I stand on the top of a mountain and look down on the valley, seeing the trees in the distance, the deer, the horses and the stream below, then look up at the sky, the clouds and the birds, it is all perfect and magical right up to the moment that, suddenly and brutally, a human being walks into view. The spectacle I was enjoying from the mountain top is simply ruined. As concerns the structure of my novels I am less certain since I never really think about it. But since you are interested all I can say is that the structure isn’t something I decide but what is generated by the madness and intensity of my characters. Or rather that it is as if someone were speaking behind them, but I myself don’t know who it is. What is certain is that I am afraid of him. But it is he that speaks, and his speeches are perfectly mad. Under the circumstances it is self evident that I have no control over anything. Structure? Controlling the structure? It is he who controls everything, it is the furious speed of his madness that decides it all. And given this fury and madness it is not only impossible to remember anything or even think — the only recourse is forgetting.

...(more)via

_______________________

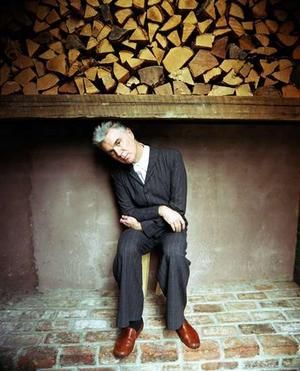

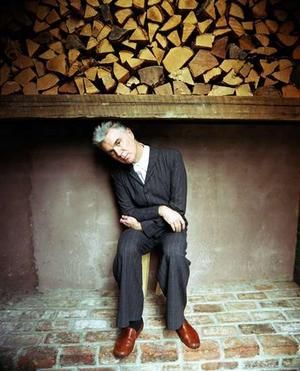

David Byrne

b. May 14, 1952

Burned Trees

René Groebli

via

_______________________

The Indoors is Endless

Tomas Tranströmer

(....)

So many islands, so much rowing

with invisible oars against the current!

The channels open up, April May

and sweet honey dribbling June.

(....)

The future opens, he looks into

the self-rotating kaleidoscope

sees indistinct fluttering faces

family faces not yet born.

By mistake his gaze strikes me

as I walk around here in Washington

among grandiose houses where only

every second column bears weight.

White buildings in crematorium style

where the dream of the poor turns to ash.

The gentle downward slope gets steeper

and imperceptibly becomes an abyss.

— from New and Collected Poems by Tomas Transtromer, translated by Robin Fulton.

via

_______________________

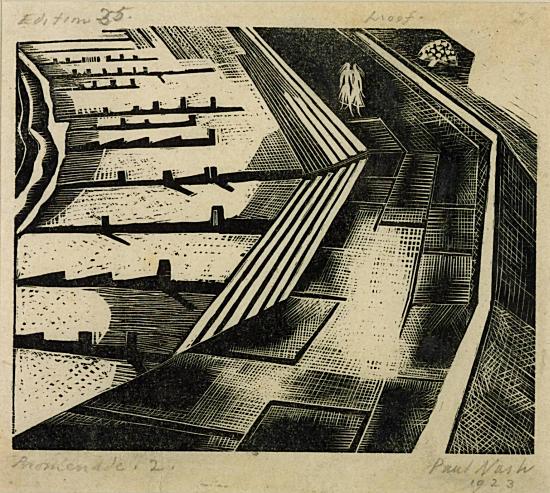

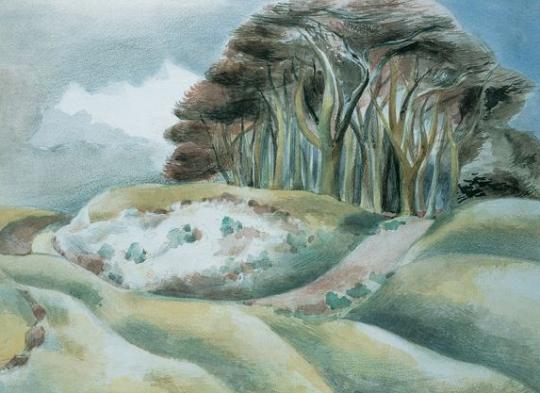

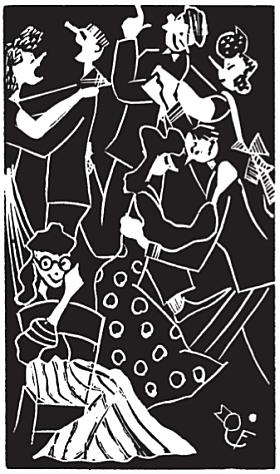

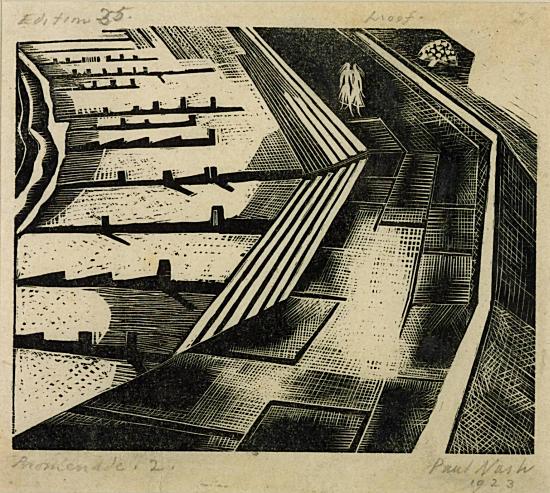

Promenade II

1920

Paul Nash

b. May 1889

_______________________

interview with Rebecca Solnit

(....) Maps, like photographs, show specifics that dismantle clichés. They make generalities—“There were 99 murders in San Francisco in 2008”—precise and poignant when you show the exact location of each death. You look at that map—one of the ones in Infinite City—and suddenly you see how that number 99 breaks down into 99 tragedies, into specific locations where you might go yourself. Maps invite us to locate ourselves in relation to whatever they show, to enter the labyrinth that is each map and to find our way out by grasping what is mapped. They are always invitations to enter, to arrive, to understand, in a way that is different than the invitations of visual and written art.

I’ve also learned that people delight in maps in a very particular way....(more)

Terrain.org A Journal of the Built & Natural Environments

via Steve Himmer

_______________________

The Sadness of Post-Workerism, or "Art and Immaterial Labour" Conference:

A Sort-of Review

David Graeber

2008

mediafire pdf

Perhaps this seems unduly harsh. I have, after all, trashed the very notion of immaterial labor, accused post-Workerists (or at least the strain represented at this conference) of using flashy, superficial postmodern arguments to disguise a clunky antiquated version of Marxism, and suggested they are engaged in an essentially theological exercise which while it might be helpful for those interested in playing games of artistic fashion or imagining broad historical vistas provides almost nothing in the way of useful tools for concrete social analysis of the art world or anything else. I think that everything I said was true. But I don’t want to leave the reader with the impression that there is nothing of value here.

First of all, I actually do agree that thinkers like these are useful in helping us conceptualize the historical moment. And not only in the prophetic-political-magical sense of offering descriptions that aim to bring new realities into being. I find the idea of a revolutionary future that is already with us, the notion that in a sense we already live in communism, in its own way quite compelling. The problem is, being prophets, they always have to frame their arguments in apocalyptic terms. Would it not be better to, as I suggested earlier, reexamine the past in the light of the present? Perhaps communism has always been with us. We are just trained not to see it. Perhaps everyday forms of communism are really—as Kropotkin in his own way suggested in Mutual Aid, even though even he was never willing to realize the full implications of what he was saying—the basis for most significant forms of human achievement, even those ordinarily attributed to capitalism. If we can extricate ourselves from the shackles of fashion, the need to constantly say that whatever is happening now is necessarily unique and unprecedented (and thus, in a sense, unchanging, since everything apparently must always be this way) we might be able to grasp history as a field of permanent possibility, in which there is no particular reason we can’t at least try to begin building a redemptive future at any time. There have been artists trying to contribute to doing so, in small ways, since time immemorial—some, as part of bona fide social movements. It’s not clear that social theorists—good ones anyway—or doing anything all so entirely different. _______________________

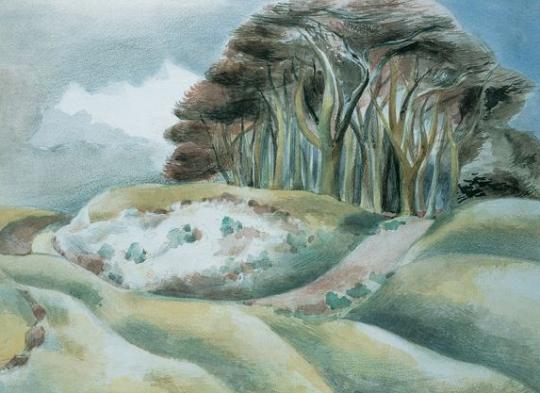

Paul Nash and The Wittenham Clumps

_______________________

The Mystery Of The Missing Clocks

David Edwards

medialens

(....)

We live in a society, then, that responds to the problem of headaches with endless glossy adverts for innumerable kinds of painkillers. It does not advertise the dramatic power of simple tap water to relieve and prevent headaches caused by dehydration, notably after some kind of exertion.

But the greatest missing ‘clock’ of all concerns the most fundamental issue of all: how best to respond to the suffering of the human condition. It involves the kind of solution the filter system cannot abide – one that is completely free, instantly and universally available, unmonopolisable, requiring no equipment or specialist training. Although it is the living heart of the great mystical teachings, it is almost never discussed by the gatekeepers of organised religion – it is just too simple, too available, requiring no priesthood, no temple, no rituals, no scriptures, no hotline to an invented Cosmic Father Figure. As a result, it has been understood but almost completely unknown for literally thousands of years.

The rogue mystic, Osho – one of the most insightful and outspoken, and therefore maligned, of spiritual teachers – gave a clear example indicating the general theme:

‘You are sad. Go into your sadness rather than escaping into some activity, into some occupation, rather than going to see a friend or to the movie or turning on the radio or the TV. Rather than escaping from it, turning your back towards it, drop all activity. Close your eyes, go into it, see what it is, why it is – and see without condemning it, because if you condemn you will not be able to see the totality of it…

‘And you will be surprised: the deeper you go into it, the more it starts dispersing. If a person can go into his sorrow deeply he will find all sorrow has evaporated. And in that evaporation of sorrow is joy, is bliss. Bliss has not to be found outside, against sorrow. Bliss has to be found deep, hidden behind the sorrow itself. You have to dig into your sorrowful states and you will find a wellspring of joy.’ (Osho, The Book Of Wisdom)

The statement that ‘Bliss has not to be found outside, against sorrow’ runs counter to exactly everything our consumerist society tells us. In a world of action-oriented problem-solving it seems absurd to suggest that the simple tap water of awareness, of watching, could be the solution to fundamental aspects of human misery (without denying, of course, the importance of rational inquiry)....(more)

_______________________

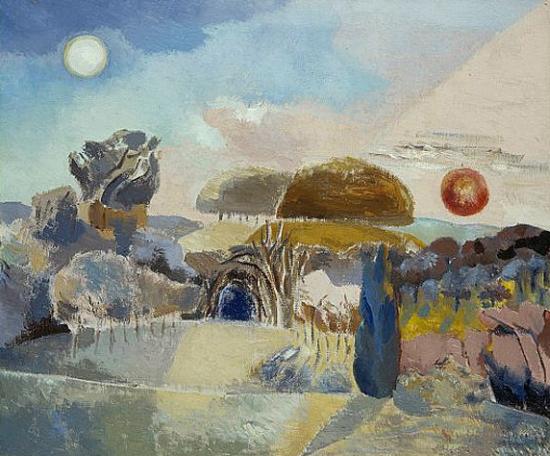

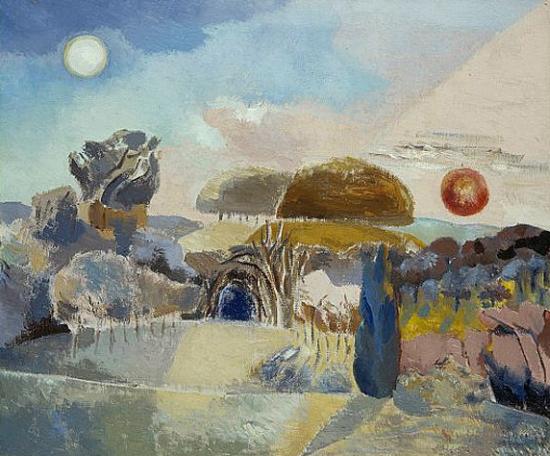

Landscape of the Vernal Equinox (III)

Paul Nash

(1944)

_______________________

Quentin Meillassoux and the Crackpot Sublime

Adam Kotsko looks at Quentin Meillassoux, The Number and the Siren

"a "decipherment" of Stéphane Mallarmé's enigmatic final poem, Un Coup de Dés jamais n'abolira le Hasard (A Throw of Dice Will Never Abolish Chance)"

(....)

Meillassoux’s flair for the dramatic twist is one of those rare coincidences when a philosopher’s style and thought match up perfectly. His entire work is centered on the conviction that the universe is a much stranger place than we ever could have guessed, leaving room for even the most outlandish hopes. In his first major published work, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency , he argues for a view of the world centered on contingency rather than necessity — that is to say, for a universe ruled by chance rather than by any foundational laws. If our world appears to be regulated by immutable natural laws, that’s just a coincidence, a state of affairs that could easily change. Similarly, if it seems indisputable that there’s currently no God, that’s no reason to assume a God couldn’t pop into existence at some future date.

It seems natural, then, that Meillassoux would be drawn to Mallarmé’s meditation on contingency and chance ......(more)

The New Inquiry

Maurice Sendak

June 10, 1928 – May 8, 2012

Photograph: Tim Knox

Maurice Sendak on ‘Bumble-Ardy’

paris review

December 27, 2011

(....)

In reading Bumble-Ardy, I was reminded of that terrifying image from Outside Over There, when the infant is being hauled out the window by goblins, replaced by a horrible, uncanny ice decoy, while her older sister looks the other way. Is Bumble another “ice baby,” another kind of living stillborn?

I hadn’t quite thought of it in those terms, but I like that identification. It resembles what actually occurred to me as a child. Terrible things happened and were not explained. My parents were ignorant peasants from the old world. They came here and knew nothing. My life in Brooklyn was in constant danger because of my bad health. There was danger everywhere. The Lindbergh baby, the hundred-million-dollar baby—there we were, potential victims, all of us. Not even wealthy parents could protect their children. So what did kids do? You had to form a kind of fake life, to protect yourself. Because you learn very quickly that parents can’t protect you. It leaves a lurking fear. You never feel safe, never believe, really, that your parents are any safer than you, or could protect you from the unknown....(more)

Maurice Sendak, who let children be just what they wanted

Morven Crumlish

Maurice Sendak, who died on Tuesday, was one of the few – and rare – writers who truly wrote for children. Not to entertain their parents, or to improve their social skills – he told the stories that children live themselves, wobbling on the uncomfortable brink between dreams, imagination and reality, where truth is whatever can be remembered, whether it really happened or not.

(....)

Sendak's children are given the power to overcome the monsters, to escape the creepy night-time bakers. They are crowned kings, and have sufficent influence to make everyone "be still"; they can fashion dough into an aeroplane and fly away – no wonder children don't find his books as unsettling as adults do. Even being sent to your room is no hardship, when the walls become the world all around, and you can sail off in your bed to wreak havoc elsewhere. Sendak makes children the promise of growing up. One day this will come true, and you will have the opportunity and the means to leave, and to choose, and yes, perhaps you will choose to sail back to mother, but by then she will be lucky to have you....(more)

_______________________

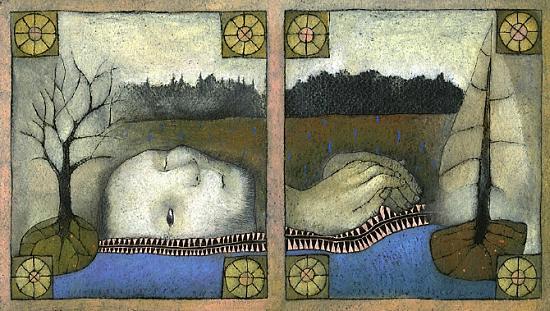

Jüri Mildeberg

The Swamp Ladies of Estonia 2

50 Watts

_______________________

The death of American secularism

Jacques Berlinerblau

New Humanist

Volume 127 Issue 3 May/June 2012

(....)

When, how, and why did secularism become such a problematic and controversial idea in America? Why have both of the nation’s major political parties and three branches of federal government turned their backs on it? Why has jacking-up (as the American footballers like to say) an already woozy secularism become such a lucrative sport for political and religious demagogues alike?

(....)

Culture Warriors love a void. With secularists perennially incapable of articulating and agreeing upon what they stand for, their opponents are more than happy to do it for them. Caspar Melville memorably quipped in The Guardian: “Secularism is the handy one-word distillation for all that is wrong in the modern world. Consumerism, divorce, drugs, Harry Potter, prostitution, Twitter, relativism, Big Brother, lack of moral compass, lack of community cohesion, lack of moral values, vajazzling.” A quarter-century ago things were scarcely different. In 1985 a New York Times writer joked that Secular Humanism stood for “everything they [the Religious Right] are opposed to, from atheism to the United Nations, from sex education to the theory of evolution to the writings of Hemingway and Hawthorne.”

The time has arrived for some sort of open, frank, melanomas-and-all discussion of what secularism does (and does not) entail. This conversation would benefit from a dash of critical distance and objectivity. In the academy, the subject of secularism lies pincered between two of the most ideologically rigid detractors imaginable. On the one side, a postmodernist and postcolonial Left has argued – in academic jargon of impressive incomprehensibility – that secularism is something called a “discursive formation” and a sinister policy henchman of “Enlightenment Reason” (a very odious thing in such quarters). On the other, the religious Right imagines it as an enemy of religious freedom and close personal friend of Nazism, Communism, Jihadism, what have you....(more)

via Pierre Joris

_______________________

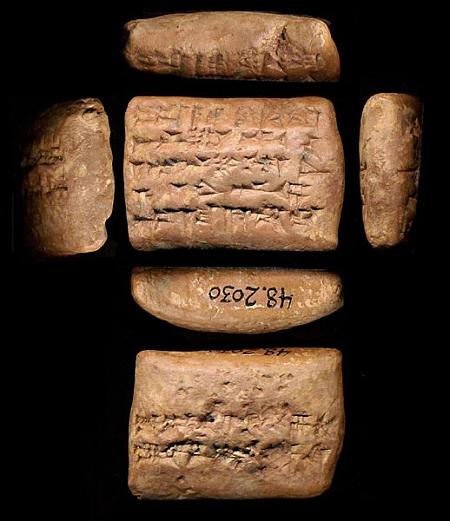

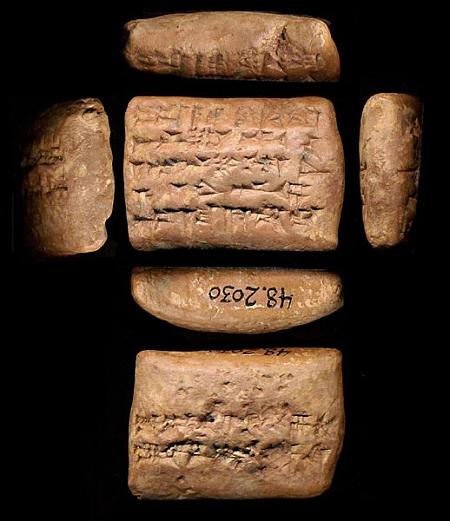

Babylonian - Economic Document

circa 549 BC

Commons:Walters Art Museum

Baltimore, Maryland

"On February 2, 2012, Walters Art Museum adopted Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license for all text and images published on their website art.thewalters.org and began working with Wikimedia Commons on mass upload of about 20 thousand images. On March 26, uploading was completed."

_______________________

Agnomia

Róbert Gįl

transl. from the Slovak by Michaela Freeman

exquisite corpse

This is a tautology of every moment, as if every moment was necessarily a tautology.

“It seems undignified,” says Jan, “to accept congratulations for the past, as if that from the past, which is not subject to a time shortcut, was totally irrelevant. This is not a criticism of heroism, but a criticism of the need to place heroism out for adulation, as if every heroism was necessarily admirable – and not some other one. Isn’t this the conventional exchange of the act of socially defined heroism for an act of heroism which is highly individual, and thus socially undefinable? Where is the boundary between the need of a heroic act of a socially defined hero and the need of a heroic act of a hero, who is defined by this act itself into the position of a partaker of a heroic deed, who doesn’t feel the need of a social proclamation of this fact?” Jan asks....(more)

_______________________

The Walking Cure

On the road with a terminally self-aware spiritual seeker

Peter Manseau reviews Gideon Lewis-Kraus, A Sense of Direction: Pilgrimage for the Restless and the Hopeful

bookforum

(....)

... pilgrimage narratives are almost as old and universal as pilgrimage itself. Ambulatory religious odysseys exist in every culture on earth; from Mecca to Lourdes to the Ganges to Taos, New Mexico, the globe is pockmarked with sacred places that believers are forever approaching, slouching toward eternal reward while leaving the burdens of their everyday lives behind. And because the point of a pilgrimage is never merely getting there but returning to tell the tale, pilgrimage literature exists in every culture as well. True, the genre has a limited range of plots, which tend to lean on tidy morals and similar casts of oddball characters. But slight variations within the template can make or break the tale; as Chaucer taught us in high school, all that separates one pilgrim’s progress from another’s is the unique spin emerging from a story that is derivative by design.

Gideon Lewis-Kraus is a unique pilgrim, to say the least. He is certainly not the first nonreligious person to make a religious journey—the Camino is as popular with godless gap-year backpackers as with faithful Catholics these days—but he is likely the first son of two rabbis to describe a number of very different religious pilgrimages in the same book....(more)

_______________________

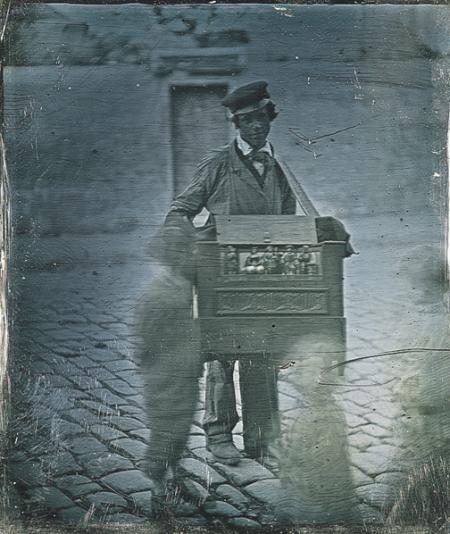

Organ Grinder

ca. 1848

Gabriel Cromer Collection

Just Drifting

1939

Adolf Fassbender

1884-1980

_______________________

Occasionals

Carol Watts

(Reality Street, 2011)

From Occasionals: autumncuts

(....)

XVII

Is it so much later. Word from a shouting river.

Arrives, it is the interim. Before an Atlantic

storm, with hours of quiet rising. Weakness,

in light, lays down to rest. The falling out

of purpose. Opportunity to see a sequence, in.

Time, in one, the action starts out like a hunt.

Cut a story short. There he arrives, in the fourth,

and the game is bagged up. Yet, she said, this.

Could never be known, unless you saw them

together. The man who jumped from a tower

and flew a furlong. Wanted movement forward,

it was said. He could have improved on that

performance, if a tail had occurred to him.

But was prevented and lived, ripely. An impelling.

Towards, the risk of arrival. When sky darkens,

in notches, but it is too soon. Birds fall out,

expecting shattering, hold breath. And regroup

soundlessly, the fatigue of alarm silences.

Can we calculate the rising of water, he asks,

in inches. Using measurements handed in, always

the turn of the archaic. As if seriousness comes

that way. Looking at his feet, they already push.

Through the flow, the child stamps. He wrote,

the illusion of facing it well. Is our inhabiting,

handed on. In an impulse for protection, perhaps,

or the other side. Of a rationing, as if the chance

for anticipation remains. Possible light, drifts.

A cat. Descends in three, wall, ledge, sill. Cries.

Architecture rings true

A review of "Occasionals"

Charles Alexander jacket2

(....)

Perhaps I am presenting Watts’s work as a philosophical idea, or even a demonstration of a poetic. And, while it might be that, it also contains the personal, which comes through in glimpses, inferences, double entendres.

You think you have it.

Taped, then it returns and you see. Your

self, approaching. Unconscious, a deer

in the undergrowth, or embarrassed at.

Meeting, didn’t you just come by the other.

Other way, she might say, you. Answer, yes.

Are you caught out by each. But time goes,

it does not unpick from. Skin is older,

ready to crepe up behind you.

(“springcuts” VIII)

There occurs an urgent, sometimes joyous, sometimes startling physicality in Occasionals, with “cells bursting out of” (“springcuts” X), “vital heaving in city bodies” (“springcuts” XV). Yet if there occurs intense eroticism, it signals not just a personal experience, but the world as erotic embrace, as when “birds adapt, raid / brief tongue incursions. Sheltering, from. / Battery, then they dart in open. Dares, / how many. Sound, bound, soar more.” The erotic is, in this instance, a matter of language as well, so that, while the “tongue incursions” seem obvious, the climactic release powers through in “Sound, bound, soar more,” a culmination of openness and escape, linguistically speaking as well as literally soaring....(more)

_______________________

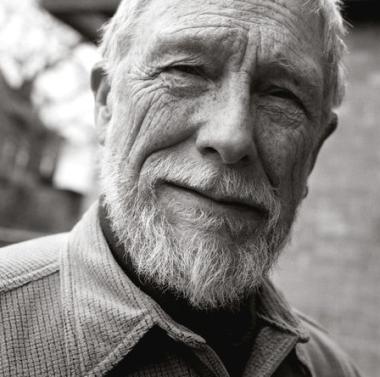

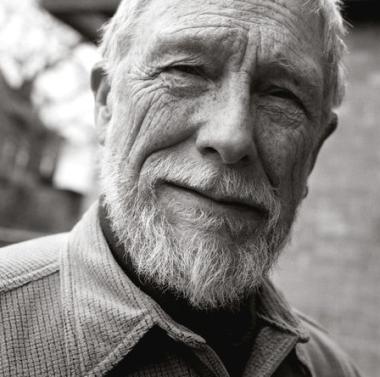

Gary Snyder

b. May 8, 1930

Old Bones

Gary Snyder

Out there walking round, looking out for food,

a rootstock, a birdcall, a seed that you can crack

plucking, digging, snaring, snagging,

barely getting by,

no food out there on dusty slopes of scree—

carry some—look for some,

go for a hungry dream.

Deer bone, Dall sheep,

bones hunger home.

Out there somewhere

a shrine for the old ones,

the dust of the old bones,

old songs and tales.

What we ate—who ate what—

how we all prevailed.

Mountains and Rivers Without End

Gary Snyder google books

The Practice of the Wild: With a New Preface by the Author

Gary Snyder

google books

_______________________

Deep Water

Adolf Fassbender

1937

_______________________

The Prince of Parataxis

Édouard Levé's visionary book of unrelated ideas

Wayne Koestenbaum

bookforum

(....)

Autoportrait, gracefully translated by Lorin Stein (who has also translated Grégoire Bouillier’s The Mystery Guest, which falls, like the late Levé’s works, into a category of French prose I’d call “the short, the sweet, the cerebral, the candid, the chic”), functions within a soft-core Oulipian economy of procedural moves servicing confessional ends: Like the essays in Perec’s classic Species of Spaces, Levé’s Autoportrait observes stylistic proprieties at once whimsical and pasteurized, or, one might say, at once comic and thanatopic. Autoportrait is a series of ostensibly factual declarations or descriptive statements, narrated by an “I,” all in a single paragraph; unlike I Remember, or the epigrammatic novels of David Markson, another practitioner of a doldrum-free “new sentence” aimed at catharsis rather than alienation effects, Autoportrait’s sentences do not occur in separate paragraphs, but are all crammed together into one long chunk, implying that a long-harbored reluctance to speak has at last been conquered, and, now that the silent epoch has ended, everything must be uttered in a single flash, without interruption, lest a sudden scruple kill off the desire or ability to speak. The voice, once it initiates the work of memory, can’t stop. And yet Autoportrait is not a talking cure; Levé well knows, as Freud came to discover, that any voice, whether heard, overheard, or remembered, plays tricks with time: “My voice recorded one minute ago on a Dictaphone sounds older than my voice recorded digitally five years before.”...(more)

_______________________

Fishing Wharves

Adolf Fassbender

1937

_______________________

Cultural Politics

Volume 8, Number 1, March 2012

The Dark Side of the Spectacle:

Terror in Norway and the UK Riots

Douglas Kellner

(....)

In this study, I engage “the dark side of the spectacle” involving the Norway terror rampage and the UK riots and argue that while exploring these types of media spectacle requires careful sociological analysis, what they have in common is the quality of embodying male rage and exhibiting crises of masculinity that are resolved in spectacles of violence and terror. While many of us have promoted new media and social networking and have seen the media spectacle of the Arab uprisings as progressive forces, I want to stress in this study the “dark side” of contemporary media and technology that can promote and disseminate societal violence, hatred, and terror. As for media and technology themselves, they combine what different theorists see as “positive” and “negative” effects, and in my view their social functions and effects are complex, highly contested, and often extremely ambiguous.

In general, media spectacles therefore cover a wide range of phenomena and have unpredictable effects. As the examples cited above suggest, media spectacles can be vehicles of democratic protest and upheaval, as well as terrorist assaults on the public. In this study of the Norway killings and the UK riots of summer 2011, I focus on spectacles of terror and horror, engaging in analysis and diagnostics of the dark side of contemporary history. I very consciously break with a tendency of US and other Western discourses and media that associate terrorism with al-Qaeda and Islamic jihad, and instead I insist that there are many branches of domestic terrorism, two of which I explore in this study....(more)

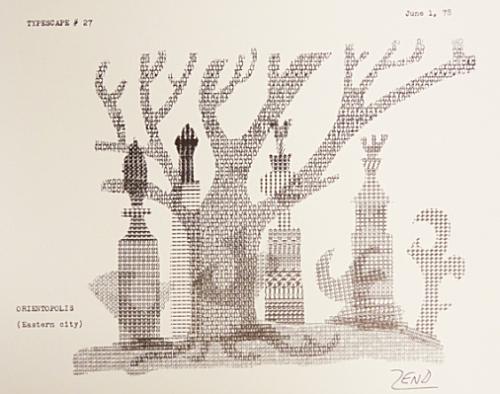

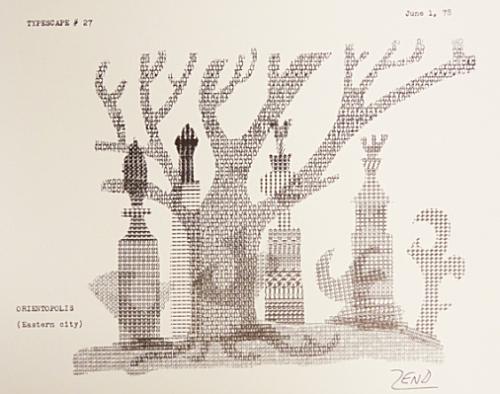

Orientopolis

(Eastern city)

(June 1, 1978)

Robert Zend

1929-1985

Robert Zend’s “Typescapes”: Concrete poetry from a Renaissance man of Canadian letters Camille Martin Rogue Embryo

... Arbormundi (Tree of the World), a portfolio of seventeen of Zend's concrete poems created on a typewriter, for which he coined the word "typescapes."

(....)

The miracle of these concrete poems is that from what must have been a slow and painstaking process of planning and execution using paper inserted into a clunky machine come visions of airy lightness and delicate movement....(more)

_______________________

Two types of metafiction

balaustion

.....................................................

a response from Ray Davis

As Balaustion's examples suggest, there is a history, a lifespan, to apparently unmediated narrative or lyric. Thackerey and Trollope notoriously lack that goal, Byron (and then Pushkin) contested its triumph, and by the time we reach Bouvard & Pécuchet and Huysmans it's devouring itself. The perplexing disruptions of Ulysses simmered down into a signature sauce for Beckett and O'Brien, and then dessicated into spice jars for postmodern fabulism and swingin'-sixties movies. If Nabokov is a chess problem and Perec is a jigsaw puzzle, John Barth and Robert Coover are search-a-word.

What I really wanted to blather about, though, was a rare third type of metafiction, neither the recircling of an already-overworked puzzle, nor the matter-of-fact surfacing of one discursive mode in a cove of splishy-splashy discourse, but instead doing something — an emotionally engaged and affectively effective metafictionality....(more)

_______________________

marsh marigolds

photo - mw

_______________________

Public Space and the Skills of Citizenship:

An Interview with Elihu Rubin

designg observer

(....)

Public spaces can be charged politically because they enable citizens to gather, to represent themselves and to transmit messages. There is also a more benign sense of public space as a place where we can just idle. And yet there are tensions in terms of belonging to those places, the right to just be in those places. How long can someone who has nowhere else to go spend time in that space? The test of a public space is its tolerance. Public spaces are not always easy places, nice places, pleasant places. Public spaces are often difficult places where our tolerance for other people who are not like ourselves is tested. This is why social norms like “civil inattention” — a term taken from the sociologist Erving Goffman, and which refers to our right to be left alone — end up governing many public spaces. I can be here, and you can be here, and even though we may not agree with each other, we both tolerate each other. For me, that is part of the definition of cosmopolitanism. ...(more)

_______________________

‘Inexcusable’ Indifference to Extreme Poverty

interview with Frances Fox Piven

(....)

Something else is beginning to happen now. There are organizations of the poor, some of them who trace their origins back to the 1960s, and these organizations are very supportive of Occupy. This is not just a movement of college kids whose futures have been destroyed. This isn’t just a movement of workers who find their wages reduced. This should be a movement of all of the people who suffer the burdens of extreme inequality, especially the poor.

Poor and minority people in the United States have been singled out, basically since about 1980, as the targets for right wing and Republican rhetoric — tremendous amounts of castigation of the poor, as if it were poor people’s fault that things are going wrong in America. The argument has been that the big moral problem of the United States is that “those people” don’t get up and work hard, “those people” have babies out of wedlock, “those people” hang out on the stoop and drink beer…. It’s relentless. This kind of propaganda is mainly designed for the great mass of working people in the U.S. to quell whatever sympathies they might have for the poor, but also to instill fear in them of the risk of falling into poverty, the risk of having to depend on a government program or a handout. But the poor are also an audience for this kind of castigating propaganda. It has an effect — it makes people shrink into themselves, and that’s a very bad thing, because then they can’t be citizens, they can’t be political, they can’t protest the conditions under which they live.

If they — when they — link up with the larger protests, this will be an enormous boost to their sense of themselves, of their rights, and of their capacities to fight back against the policies that have brought them this low....(more)

_______________________

Mountaineer's home

Corbin Hollow

photo by Arthur Rothstein, October 1935

Broken Back Run: Corbin Hollow, Old Rag and Nethers People, Blue Ridge

from the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection

presented by Tom Clark

_______________________

Politics and Culture

Edition 2012 Issue 1

Revisiting Thorstein Veblen's "The Theory of the Leisure Class"

_______________________

TWO LINES Online May 2012

center for translation

_______________________

Property Rights in the Cloud

How much of you is really yours? In the age of cloud computing, it’s a crucial question.

David Sirota

_______________________

Charles Augustin Lhermitte

(1881-1945)

_______________________

Three new poems

George Szirtes

High Dudgeon

1.

I live in High Dudgeon

My room’s a brown study

The colour is grim and,

I like to think, muddy.

The whole place was painted

In foulest distemper

And the painter decamped

A most unhappy camper.

(....)

...(more)

Mad Hatters' Review Issue 13

The Carol Novack Tribute Issue

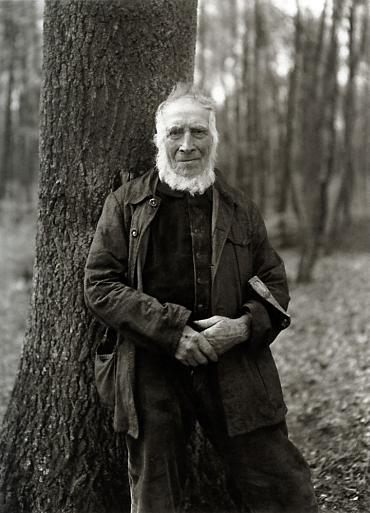

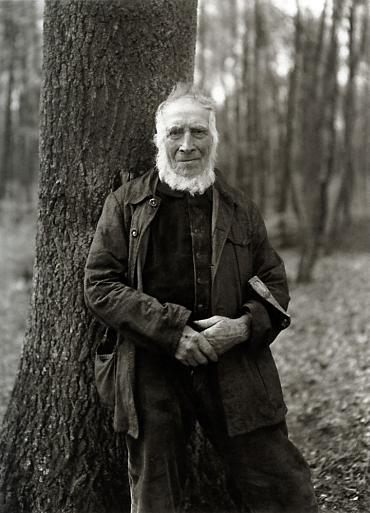

The Woodcutter

1931

August Sander

1876 - 1964

_______________________

About Looking

John Berger

1980

mediafire pdf

The Suit and the Photograph

What did August Sander tell his sitters before he took their pictures? And how did he say it so that they all believed him in the same way? They each look at the camera with the same expression in their eyes. Insofar as there are differences, these are the results of the sitter's experience and character — the priest has lived a different life from the paper-hanger; but to all of them Sander's camera represents the same thing. Did he simply say that their photographs were going to be a recorded part of history? And did he refer to history in such a way that their vanity and shyness dropped away, so that they looked into the lens telling themselves, using a strange historical tense: I looked like this. ...

_______________________

Facing the Camera

Alberto Manguel

geist

(....)

... The photographic image is always definitive.

This is certainly the case when it comes to photographing people. We humans think that we have a single, unique face: photography disproves us. The myriad unique faces that, throughout our lives, are captured by the camera, from babyhood to that final face that we will never see, create a multiple, ever-changing face that can never quite be pinned down to one we can call uniquely ours. Who are these people? we ask, flipping through an album of our own faces. How can all these different features, tints of skin, looks and gestures, all be that single person we call “I”? Never was Rimbaud’s dictum so true as in the case of our portraits. The photographed “I” is always another.

...(more)

_______________________

August Sander

_______________________

Storybook-keepers

Narratives and Numbers in Nineteenth-Century America

Caitlin Rosenthal

(....)

To give an account of something is to tell a story about it, and to hold someone accountable is to make him responsible for that story. At Countrywide, executives used accounting to spin a story that distorted the truth and deceived shareholders. They told the public a vastly different story than they told each other. But account books tell stories even when their keepers are not trying to deceive. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, individual men and women used accounting as a guide to navigate the increasingly complex world around them. Bookkeepers braided together words and numbers, sometimes following the recommendations in the latest textbooks, but also developing their own idiosyncratic notations for making sense of the world. They scrawled rough and ready calculations alongside precise and orderly balance statements, revealing their anxieties, preferences, and priorities along the way. Following them illuminates the daily drama of accounting as a narrative, contested search for understanding and control....(more)

_______________________

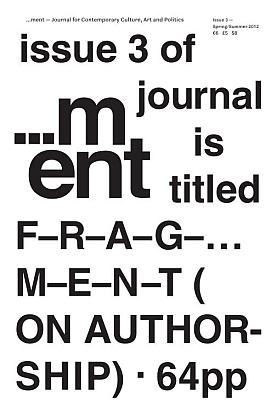

...ment — issue #3

… editorial

How and why do we articulate discourses? What are the possible implications of putting those discourses into circulation today? How do we deal with connective apparatuses that transform social interaction and knowledge into modes of production?

(....)

this issue of …ment attempts to under-stand how today, authors from observers of facts and producers of imaginary worlds become conductors of new linguistic settings, ways of thinking of and acting on reality. By means of language and actions, the author is an active agent that facilitates another kind of consciousness and another sensibility. The question is also how these worlds are generated and what are the reasons for creating and developing them. Authorship as a political space of reflection and action, in which joint efforts towards common goals and their possible results are simultaneously distributed or appropriated, represent to us a way of thinking about the mechanisms and politics of cultural production today. What it means to work, think or act both as individuals and together, what level of productive interaction we can hope to reach between the minority and the majority, the individual and the collective, the social and the political or the author and the public. We aim to reflect on authorship as a place of encounter. A space from which — as Giorgio Agamben suggests — a subjectivity is created where the being encounters language and puts itself into play without reserve, affirming the impossibility of reducing its presence to the gesture of the author. An encounter, between the author and the public, that gives shape to a new form of life. _______________________

Luna Park of Paris

1910

Poemas del rķo Wang

via

_______________________

f-Words: An Essay on the Essay

Rachel Blau Duplessis

American Literature (Mar., 1996)

ifile pdf

(....)

Both Woolf and Broodthaers claim the book and argue that as an institution of cultural accumulation the book is a space in which one wants to make one's mark, a space to use. Woolf's gesture makes a book keep the secret of her writing; her visual text calls upon us to register fear, cunning, and the hope of uncensored writing sandwiched invisibly between treatises on propriety. Broodthaers's visual text frets replacement and effacement, fingering those strings, and forte. The two gestures are differently motivated, but both are methodical critiques of method. Her gesture places Watts's words — indeed whole pages — "over" hers; his gesture writes his inked-out blocks, or veils, over Mallarme's. The gender issues of access and authority are rather stark in these examples, but taking them together one can say that writing on the side, through the interstices, between the pages, on top of the text, constructing gestures of suspicion, writing what one will (what one wills), writing over the top, writing a reading, writing an untransparent text, writing into the book - all these practices and more frame the essay.

This is an essay (my essay) about the essay. There has been a good deal of such intransigent, willful writing recently-from David Antin and Gloria Anzalduia, Charles Bernstein and Etel Adnan, Nancy Miller and Gerald Vizenor, Susan Howe and Diane Glancy, Bruce Andrews and Eve Sedgwick, Adrienne Rich and Eliot Weinberger, Trinh T. Minhha and bell hooks, Alice Walker and Robert Hass, and many others. The mode I am addressing is sometimes labeled "creative nonfiction" — a singularly unlovely and antiseptic term, especially the word "creative." Politicized poetic prose might be better, at least for starters. ....

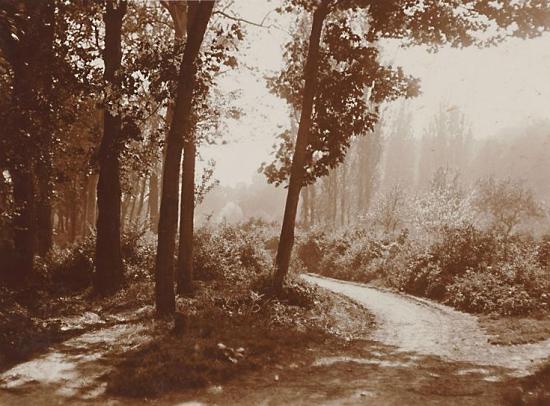

Light of Spring

Photographing the Dulwich landscape

Max A Rush

Max A Rush Photography via Jean Morris

tasting rhubarb

_______________________

CIVITAS

Lisa Samuels

No, don’t get that – back from it, we are

too apparent each, all commas and elucting

what nature gave us, ‘ick’ – forestall whatever

it is you: and never mind the ‘we are climbing out’

when you abide or that!, inscrutable timetable

up dearly, how it plains us for a game: one go

and you are always monument, a saken

optimist flying saturate via some

air or error-striven behemoth

hitting the cloud-belt with a prrup!,

so that we’re shook and unbesaddled

with a bell or supine entity that makes

us addle-stocked and mildly whipped –

from The Invention of Culture

Lisa Samuels at EPC and Shearsman

An Interview with Lisa Samuels on Laura Riding and Poetry 1 2 3

David Auerbach

waggish

Creating Criticism:

an introduction to Anarchism is not Enough

Lisa Samuels

google books

12 or 20 questions (second series) with Lisa Samuels

rob mclennan

_______________________

Notes towards a Deformed Humanities

Mark Sample

Sample Reality

I want to propose a theory and practice of a Deformed Humanities. A humanities born of broken, twisted things. And what is broken and twisted is also beautiful, and a bearer of knowledge. The Deformed Humanities is an origami crane—a piece of paper contorted into an object of startling insight and beauty.

I come to the Deformed Humanities (DH) by way of a most traditional route—textual scholarship. In 1999 Lisa Samuels and Jerry McGann published an essay about the power of what they call “deformance.” This is a portmanteau that combines the words performance and deform into an interpretative concept premised upon deliberately misreading a text, for example, reading a poem backwards line-by-line.

(....)

To evoke a key figure motivating the playfulness Samuels and McGann want to bring to language, deformance takes Humpty Dumpty apart only to put Humpty Dumpty back together again.

And this is where I differ.

I don’t want to put Humpy Dumpty back together.

Let him lie there, a cracked shell oozing yolk. He is broken. And he is beautiful. The smell, the colors, the flow, the texture, the mess. All of it, it is unavailable until we break things. And let’s not soften our critical blow by calling it deformance. Name it what it is, a deformation.

In my vision of the Deformed Humanities, there is little need to go back to the original. We work—in the Stallybrass sense of the word—not to go back to the original text with a revitalized perspective, but to make an entirely new text or artifact.

The deformed work is the end, not the means to the end....(more)

via Dennis G. Jerz.....................................................

Deformance and Interpretation

Jerome McGann and Lisa Samuels

_______________________

Mediations:

Journal of the Marxist Literary Group. a special issue on Marx or Spinoza.

Volume 25, No. 2

Commonism

Peter Hitchcock

To mention Spinoza in some leftist circles is to risk an understandable incredulity. The familiar criticisms include whether Spinoza’s explorations of emotion, theology, and metaphysics can be interpreted in any way to address the deep contradictions and predicaments of the contemporary period. Asserting that Spinoza is the first post-Marxist might be true, dialectically, but not to a dialectics where Marx and Spinoza can actually meet. Within Spinoza’s schema, this idea itself would be deemed “inadequate” and yet, in a moment when capitalist crisis screams for the insight of Marxist critique, communism sometimes seems a quintessentially Spinozist project. No Marxist (including the Marx who, tired of petty “phrase-mongering,” remarked to Lafargue that “if that is Marxism, I am not a Marxist”) can possibly believe Spinozism amounts to a communist idea if, by that idea, a riddle of history has been solved, as Marx puts it in 1844, and it knows itself to be this solution.1 A strategy of refusal, for instance, not only describes a specific moment of Italian workerism before the predations of the capitalist factory, but also Marxism’s verdict on Spinozism as a dividing line between the possibilities of revolutionary practice and those wanton idealists the other side of the Eleventh Thesis on Feuerbach. As Balibar aptly puts it, Spinoza’s thought “represents a complex of contradictions without a genuine solution.”2 Yet the question of synthesis, at once impossible and incredible, hangs over Marxist theory where, let us say, our desire from Cultural Studies to resist divisions in intellectual labor compels us to examine irresolution as itself a materialist symptom, of what, these brief notes intend to examine.

If Spinozism is necessarily a lost cause for Marxism, then it is, in the spirit of Zizek’s wild interventions, a heresy that must be embraced for all the terror of its contradictions (just as, Althusser reminds us, Spinozism was terrifying to its own time).3 It is simply not enough, theoretically or politically, to adumbrate the alchemist of affect for not being more “red,” or Gramsci, or Fanon, as if the challenge of metaphysics in materialism has been met and the proper genealogy of revolutionary thought has been secured in the name of those whose praxis and practicality are unimpeachable on their own terms. But it is also remarkably blinkered to assume the “Marx beyond Marx” is categorically Spinoza, however appreciable such a theoretical conceit might be. We know that Spinozism has affected and continues to animate specific articulations of radicalism; the only significant question is whether the substance of that engagement is true to the event of change in which it is precipitate. This, of course, is not a matter of relevance, or even of being true to Spinoza (whatever that means), but of discovering in the conjunction that is Spinoza/Marx a tenor of transformation appropriate to the material conditions of the crisis (of capitalism and of alternatives to the same). If the latter is resolved in a flourish of theoretical superfluity then such a dialogic will not have been for aught, for what is rendered excess is an historical decision (a decision of history) and not the adjudication of individual intellect. And even then, the lost cause, as Zizek underlines, may be scandalously and necessarily “found” again....(more)

_______________________

Beholden

David Graeber in conversation with Rebecca Solnit

guernica

... it struck me: in what other circumstance would a nice person just spontaneously defend the death of five thousand babies? What is it about the moral power of debt that makes people willing to accept things that they would probably not accept under any other circumstance? And I started thinking about it and realized that nobody’s ever written a book about the history of debt.

_______________________

Reflections & Pond Scum

Redding, Connecticut

1968

Veiled Yet Revealed: Masterworks from Fifty Years

Paul Caponigro

Soulcatcher Gallery

via

_______________________

Words without Borders

May 2012: Writing from the Indian Ocean

Isle Say Blood

Michel Ducasse

Translated from French by Alexis Pernsteiner and by Antoine Bargel

our fragmented history

written with a large axe

told by the bordertracers

slaves of their prejudice

our marooned history

chained by hatred

whitewashed memory, creole coolie

color anger pain dockers

our disinvented history

open book on nothingness

pages thrown into oblivion

rewritten by the portolan of night

our dismembered history

archipelago of sorrow

Chagos of our lost islands

our incomplete history

treated with complacency . . .

...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

Fifty-one contemporary poets from Australia: Part 3

edited by Pam Brown

jacket2

Poems by John KinsellaDividing the Shadows

inruat et frustra ferro diverberet umbras

— Virgil, Aeneid, book VI, lines 285–294

Most ghosts settle on the skin like eczema.

Some pass through and stimulate cancer.

It is nothing to with vengeance, even where

they are disturbed or distraught. They react

differently with different body chemistries.

They recognise genetic familiarity and follow

the trails. They show up as monsters under

black lights: Scyllas, Briareus, the rasping

creature of Lerna, flaming Chimaera, Gorgons

and persistent Harpies. Medicine and science

scythe away at them but they change shape

and rise again. Out of the shadows deep

in the gully I watch a red-capped robin

hop and skip towards a filament of fence-

line. It divides the shadows as it goes:

they close over in its wake, needing no

energy source. Darkness is the liveliest

state, they say, though the wind is light.

To untrained eyes the red-capped robin

seems unscathed, its future bright.

It casts such a small shadow. ...(more)

Part 1 and Part 2

John Kinsella at the Poetry Foundation, Poetry International Web and EPC

_______________________

Oh well, I can always be a Ph.D

Flannery O'Connor

Flannery O’Connor and the Habit of Art

Kelly Gerald

paris review

Excerpted from Flannery O'Connor: The Cartoons, edited by Kelly Gerald

“For the writer of fiction,” Flannery O’Connor once said, “everything has its testing point in the eye, and the eye is an organ that eventually involves the whole personality, and as much of the world as can be got into it.” This way of seeing she described as part of the “habit of art,” a concept borrowed from the French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain. She used the expression to explain the way of seeing that the artist must cultivate, one that does not separate meaning from experience.

The visual arts became one of her favorite touchstones for explaining this process. Many disciplines could help your writing, she said, but especially drawing: “Anything that helps you to see. Anything that makes you look.” Why was this emphasis on seeing and vision so important to her in explaining how fiction works? Because she came to writing from a background in the visual arts, where everything the artist communicates is apprehended, first, by the eye....(more)

_______________________

Poetry on the Brink

Reinventing the Lyric

Marjorie Perloff

boston review

Deją vu?

What happens to poetry when everybody is a poet? In a recent lecture that poses this question, Jed Rasula notes:

The colleges and universities that offer graduate degrees in poetry employ about 1,800 faculty members to support the cause. But these are only 177 of the 458 institutions that teach creative writing. Taking those into account, the faculty dedicated to creative writing swells to more than 20,000. All these people must comply with the norms for faculty in those institutions, filing annual reports of their activities, in which the most important component is publication. With that in mind, I don’t need to spell out the truly exorbitant numbers involved. In a positive light, it has sanctioned a surfeit of small presses . . . to say nothing of all the Web-zines.

What makes Rasula’s cautionary tale so sobering is that the sheer number of poets now plying their craft inevitably ensures moderation and safety. The national (or even transnational) demand for a certain kind of prize-winning, “well-crafted” poem—a poem that the New Yorker would see fit to print and that would help its author get one of the “good jobs” advertised by the Association of Writers & Writing Programs—has produced an extraordinary uniformity. Whatever the poet’s ostensible subject—and here identity politics has produced a degree of variation, so that we have Latina poetry, Asian American poetry, queer poetry, the poetry of the disabled, and so on—the poems you will read in American Poetry Review or similar publications will, with rare exceptions, exhibit the following characteristics: 1) irregular lines of free verse, with little or no emphasis on the construction of the line itself or on what the Russian Formalists called “the word as such”; 2) prose syntax with lots of prepositional and parenthetical phrases, laced with graphic imagery or even extravagant metaphor (the sign of “poeticity”); 3) the expression of a profound thought or small epiphany, usually based on a particular memory, designating the lyric speaker as a particularly sensitive person who really feels the pain, whether of our imperialist wars in the Middle East or of late capitalism or of some personal tragedy such as the death of a loved one....(more)

_______________________

Don River

Ashbridge's Bay Street car line

1917

Vintage Toronto

_______________________

Seven Flag Poems

Jerome Rothenberg

Flag Poem Seven

the time called

hour of the flag

has struck how bright

& fortunate

the crowd now can advance

with shiny shoes

their eyes

eager

like the eyes of children

or like the eyes of dogs

they are a faithful crowd

& each one

waves its tiny flag

the sign of their admission

to this crowd ...(more)

_______________________

Why Is the Conservative Brain More Fearful? The Alternate Reality Right-Wingers Inhabit Is Terrifying

Walk a mile in your ideological counterparts' shoes...if you dare.

Joshua Holland

Consider for a moment just how terrifying it must be to live life as a true believer on the right. Reality is scary enough, but the alternative reality inhabited by people who watch Glenn Beck, listen to Rush Limbaugh, or think Michele Bachmann isn't a joke must be nothing less than horrifying.

May 1st 2012

International General Strike Canadian directory of May Day events and Occupy actions

_______________________

How the Occupy Movement Can Confront a Capitalist System That Defies Reform

The problem is not corruption or greed, the problem is the system that pushes you to be corrupt.

Slavoj Zizek

(....)

In a kind of Hegelian triad, the western left has come full circle: after abandoning the so-called "class struggle essentialism" for the plurality of anti-racist, feminist etc struggles, "capitalism" is now clearly re-emerging as the name of the problem.

The first two things one should prohibit are therefore the critique of corruption and the critique of financial capitalism. First, let us not blame people and their attitudes: the problem is not corruption or greed, the problem is the system that pushes you to be corrupt. The solution is neither Main Street nor Wall Street, but to change the system where Main Street cannot function without Wall Street. Public figures from the pope downward bombard us with injunctions to fight the culture of excessive greed and consummation – this disgusting spectacle of cheap moralization is an ideological operation, if there ever was one: the compulsion (to expand) inscribed into the system itself is translated into personal sin, into a private psychological propensity .......(more)

_______________________

The Beach

Eastbourne, East Sussex

Edwin Smith

1955

Chris Beetles Fine Photographs

_______________________

Data Journalism Handbook

It was born at a 48 hour workshop at MozFest 2011 in London. It subsequently spilled over into an international, collaborative effort involving dozens of data journalism's leading advocates and best practitioners - including from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, the BBC, the Chicago Tribune, Deutsche Welle, the Guardian, the Financial Times, Helsingin Sanomat, La Nacion, the New York Times, ProPublica, the Washington Post, the Texas Tribune, Verdens Gang, Wales Online, Zeit Online and many others.

_______________________

Otoliths 25

_______________________

Didmarton Church

Gloucestershire

1961

Edwin Smith

(1912-1971)

_______________________

The Nights of Labor:

The Workers' Dream in Nineteenth Century France

Jacques Rancičre

translated by John Drury

medifire pdf

Readers should not look for any metaphors in my tide. I am not going to call up the pains of manufacture's slaves, the unhealthiness of workingclass slums, or the wretchedness of bodies worn out by untrammeled exploitation. There will be no exposition of aU that here, except through the glances and the words, the dreams and the nightmares, of the characters who will occupy our attention.

Who are they? A few dozen or hundred laborers in their twenties around 1830, who decided, each for himself, just about that time that they would no longer tolerate the intolerable. What they found intolerable was not exactly the poverty, the low wages,. the uncomfortable housing, or the ever-present specter of hunger. It was something more basic: the anguish of time shot every day working up wood or iron, sewing clothes, or stitching footwear, for no other purpose than to maintain indefinitely the forces of servitude with those of domination; the humiliating absurdity of having to go out begging, day after day, for this labor in which one's life was lost. There was the oppressive weight of other people as well: the workshop crew with their strut as barroom he-men or their obsequious pose as conscientious workers; the workers waiting outside for a position one would be only too glad to turn over to them; and, finally,. the people passing by in carriages and casting disdainful glances at this blighted patch of humanity.

To finish with that, to know why one had not yet finished with it, to change one's life.: turning the world upside down begins around the evening hour when normal workers should be tasting the peaceful sleep of people whose work scarcely calls for thinking. This particular evening in October 1839, for example-at 8:00 P.M. to be exact-our characters would be meeting at tailor Martin Rose's place to start a workers' journal.

_______________________

Unexceptionalism: A Primer

E. L. Doctorow

To achieve unexceptionalism, the political ideal that would render the United States indistinguishable from the impoverished, traditionally undemocratic, brutal or catatonic countries of the world, do the following:

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Living First Person

stavrosthewonderchicken

emptybottle

(....)

It’s 1992, I think, and I’m walking up a gentle slope, through a traditional village called Bena, perched on the shoulder of the volcano Inerie, in south-cental Flores, Indonesia. It’s oppressively hot, and the black volcanic dust floats up as we walk slowly uphill between the ngadhu ancestor-worship totems. The 45-degree slope of that enormous conical volcano rises up to the right. It’s all a bit dreamlike, but I can almost literally feel the memories of this burning themselves into my brain, pictures being recorded in my memory, because I’m way too deep into the moment to pull out my camera.

We reach the top of the slope, and pull up short, because falling away before us is a sheer cliff, hundreds of metres above the jungle treetops below, and we find ourselves gazing gobsmacked out over a vista that stretches, green and glorious, all the way to the distant sea.

I’ve stepped into an entirely alien world. This was the reason I shouldered the backpack in the first place.

My decades of travel came naturally, I think. I grew up in a tiny, isolated northern town in British Columbia. It was, and still is, a place of surpassing natural beauty. It’s nestled among mountains, at the end of a deep, cold lake that stretches 60 kilometres to the west, into wilderness. It’s clean and quiet and sits under a magnificent dome of dramatic sky, and forces on the people who live there a kind of respect for nature, a feeling of clinging to the edge of the vast hairy back of mother nature and an awareness that we could be thrown off at a whim.

I got out as soon as I could, but I still love the place.

...(more)

|