| wood s lot march 1 - 15, 2008 | ||

Matt Harnett

Feed My Mind

Sources  Janus Head  Japanese photography |

... soundings on the ear gain salience when meanings have been consciously acquired. Also, when sound produces sense as if organically, as its own pith, then the gap between the live thing in the world and its name can be closed – or almost. As Beckett wrote about this elusive ideal, “Watt set to trying names for things, almost as a woman tries on hats”. In 1930, in one of her most free-associating essays, “On Being ill”, Virginia Woolf meditated on the relation between sounding and meaning:In illness words seem to possess a mystic quality. We grasp what is beyond their surface meaning, gather instinctively this, that, and the other – a sound, a colour, here a stress, there a pause – which the poet, knowing words to be meagre in comparison with ideas, has strewn about his page to evoke, when collected, a state of mind which neither words can express nor the reason explain . . . . In health meaning has encroached upon sound. Our intelligence domineers over our senses. But in illness, with the police off duty . . . words give out their scent and distil their flavour . . . . Foreigners, to whom the tongue is strange, have us at a disadvantage.Mallarmé and Beckett were “foreigners” in relation to English and French respectively, and they both used their advantage, but with this difference: Mallarmé’s English lessons exhibit a scrupulous, chaste fastidiousness with language that Beckett profoundly shares; a near-pedantry, the grammarian’s niceties. But Mallarmé’s writings in English sever language from subjectivity, and syntax from significance. They do not possess Beckettian poignancy, or his sense of personal hebetude.

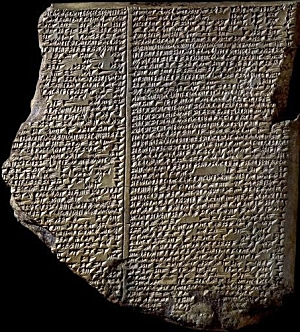

The Influence of the First Writing Poets in Sumer David Rosenberg The essay that follows looks past the earliest Hebraic strand of the Bible, c. 920 B.C.E., to the Sumerian poets who provided the sources for both the Epic of Gilgamesh and the life of Abraham. These Sumerian poems and their strategies of narrative and lament, dream and cosmic theater, are what the ancient biblical poets inherited and turned into characters. Recent poets as diverse as Charles Olson, bpNichol, and Alice Notley have used portions of the Sumerian poems but without digging into their actual authorship or influence on poetry in the West.

Income inequality — which began rising at the same time that modern conservatism began gaining political power — is now fully back to Gilded Age levels. What is often ignored by many theorists who analyze the rise of neoliberalism in the United States is that it is not only a system of economic power relations, but also a political project of governing and persuasion intent on producing new forms of subjectivity and particular modes of conduct. In addressing the absence of what can be termed the cultural politics and public pedagogy of neoliberalism, I want to begin with a theoretical insight provided by the British media theorist, Nick Couldry, who insists that “every system of cruelty requires its own theatre,” one that draws upon the rituals of everyday life in order to legitimate its norms, values, institutions, and social practices.3 Neoliberalism represents one such a system of cruelty, one that is reproduced daily through a regime of commonsense and a narrow notion of political rationality that “reaches from the soul of the citizen-subject to educational policy to practices of empire.”

What about restoring the dignity of atheism, one of Europe's greatest legacies and perhaps our only chance for peace?(...)

History's madmen are eerily similar in their sense of manifest destiny. They are the offspring of promiscuous copulation between religious zealots and crusading warmongers, and seem to arrive fullblown on the scene, bloated with Biblical bloodlust. And, did you notice that a destructive, all-powerful God personally chose each of them for a particular moment in history? Strange, isn't it, that each power-mad dictator's "moment" involves massive expansion - a Messianic struggle for world dominion - an insatiable thirst for the destruction of all who stand in his way.

Crooked Timber has been listed as one of the world’s fifty most powerful blogs by The Guardian.(...)  A Conversation with Jerry Spagnoli A fundamental reason I use photography in my work is to exploit its apparent simple transmission of facts, its objectivity. We all know that photographs lie, actually, to put it more accurately, photographs tell tales. In our daily life we take our experience of the world as objective, neutral, and trustworthy but of course everything we experience is heavily mediated by our training, past experiences and patterns of thought. We structure our lives by the stories we use to give meaning to what would otherwise be a chaos of information. It's this experience of the world as an endless matrix of individual narratives that I am trying to get at with my work. Using different photographic technologies allows me to approach it from different angles.

Increasingly I am coming to feel that Continental social and political theory- especially in its French inflection coming out of the Althusserian, Foucaultian, Lacanian, and structuralist schools -woefully simplifies the social and therefore is led to ask the wrong sorts of questions where questions of political change is concerned.(...)

In an era obsessed with “identity,” it’s useful to remember that identity is precisely that quality in a person, or group, that cannot be appropriated by others; in a world in which theme-park-like simulacra of other places and experiences are increasingly available to anyone with the price of a ticket, the line dividing the authentic from the ersatz needs to be stressed, rather than blurred. As, indeed, Ms. De Wael has so clearly blurred it, for reasons that she has suggested were pitiably psychological. “The story is mine,” she announced. “It is not actually reality, but my reality, my way of surviving.”(...)

These photographs of McClellan Street by David and Peter Turnley, taken in 1972-73, help us understand how America came to be the country that it is today.

An article in the New York Times by Morgan Stanley's Asia chairman, Stephen Roach, states that the country is not in a cyclical downturn, but post-bubble recession. There is a big difference. The Fed's interest rate cuts and Bush's “Stimulus Plan” are unlikely to stop housing prices from continuing to fall nor will they miraculously fix the problems in the credit markets. The massive expansion of credit in the last 6 years has created a $45 trillion derivatives balloon that could implode or just partially unwind. No one really knows. And no one really knows how much damage it will cause to the global financial system. Stay tuned. Roach notes that the recession of 2000 to 2001 was a collapse of business spending which only represented a 13% of GDP. Compare that to the current recession which “has been set off by the simultaneous bursting of property and credit bubbles.... Those two economic sectors collectively peaked at 78 percent of gross domestic product, or fully six times the share of the sector that pushed the country into recession seven years ago.”

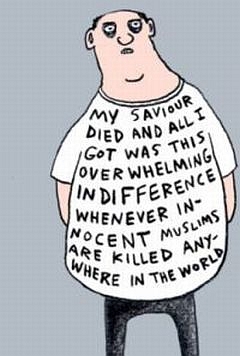

... avowedly antihumanist ideas have been increasingly breaking the surface of public discourse after 9/11--whether as the open advocacy of imperialism by Robert Kaplan or the "new racism" that justifies itself not on the basis of the "cultural" or "natural" superiority of the West but according to "unabashed economic egotism". Yet such appeals to brute, naked force and amoral national interest run counter to the value system of Christian morality (underscored by the title of Kaplan's book) that informs mainstream American society. It is instructive here to refer to Zizek's account of ideology, the function of which is to "combine a series of 'inconsistent' attitudes" inclusive of sentiments of both assent and critique, so that the "obscene unwritten rules" which sustain power may prevail over the public Law. Ideology is thus a way to "have one's cake and eat it," providing unity for heterogeneous and contradictory positions, such as believing in the existence of a Christian God and a moral universe while approving of tyrannies and massacres in developing countries as the necessary conditions for one's own peace, security, and economic well-being. Such antagonistic contents become unified through a "quilting point" (point de capiton), an "effectively [...] immanent, purely textual operation" that becomes comprehended as an "unfathomable, transcendent, stable point of reference concealed behind the flow of appearances and acting as its hidden cause".

Ronald Reagan's ability to get working men to vote for policies that were clearly not in their interests casts a long shadow over US politics post 9/11.

Joseph Mills

Five poemsA Ballad Of Drugs And 9/11 Peter Dale Scott

The Pleasure Garden

More than once, late at night when the chaplain has gone home, I have been asked by grieving parents to baptize their stillborn infant. I could leave it for the nurses but these are my patients. So I become a priest and honor the request. I enter the utility room again. I turn on the facet in the sink and wait for the water to warm. I don’t know why I do this, the baby is not alive, the baby doesn’t know, it can’t feel, it is dead. I do it anyway.(...)Hospital Drivea journal of reflective practice in word and image via new pages blog

Children are not, qua children, innocent. We have all been children and know—unless we prefer to forget—how little innocent we were, what determined efforts of indoctrination it took to make us into innocents, how often we tried to escape from the staging-camp of childhood and how implacably we were herded back. Nor do we inherently possess dignity. We are certainly born without dignity, and we spend enough time by ourselves, hidden from the eyes of others, doing the things that we do when we are by ourselves, to know how little of it we can honestly lay claim to. We also see enough of animals concerned for their dignity (cats, for instance) to know how comical pretensions to dignity can be.

Opening of meeting house The Eye of an Outsider

There are many kinds of looks, but a gaze is peculiar. It is a steady look. It is not a dirty look, though it may be “dirty” in some sense. (The man’s gaze made me feel dirty, among other complex sensations, but it was hardly a dirty look.) A gaze is never wild, though it may be mad. A gaze may not actually last long, but it is never a blink, neither hasty nor abrupt. It cannot be confused with a glance or a glimpse. There may be a battle of gazes. The gazer may “avert his gaze” under pressure or threat. I was afraid, and had no way to explore this option in Chicago. A gaze’s steadiness reflects thoughtfulness. It indicates a mind at work (somewhere, unknown and remote) thinking, drawing inferences, contemplating. It is the opposite of a stare. A stare shows dispassion, even an implacable lack of emotional connection. It is the look of an animal contemplating prey, or that of an android. (Tracking and identification data scroll down a head’s-up screen covering its field of vision.) A stare, heartless, without empathy, is the way you might expect a psychopath to consider you before making his kill. Men seem to understand the weight of intimidation that a stare can convey: in many sports, such as boxing, the initial stare-down is a ritual of domination. Even in make-believe, a stare displays an aggressive contempt and indifference: pitiful bug, I am going to destroy you. However brief, a gaze indicates thoughtfulness. The gazer seems to contemplate the person he gazes upon and even to invite connection.

Painter

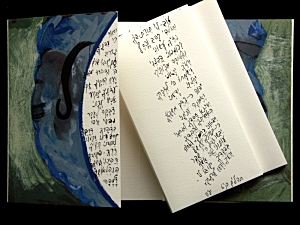

Not Simply a GatheringAnother reason I don't like to define the word "book," is that I've been to so many conferences where four days are spent debating, quibbling, and yelling in very emotional fashion about what is a book, which usually means, "What I make are books, what you make is something else." There are only twenty-five people in the whole world that care about this stuff, why are we fighting? What we should be doing is encouraging people who only watch videos, who only listen to music to see artists' books. But people want to draw little lines in the sand and say, "This is my territory, stay off it." I feel a library can be more neutral ground, where hopefully you don't take sides. That's very conscious on my part. I do not take sides. Nobody would have any clue whether I really, honestly, in my soul, love this book or hate it, because it is inappropriate for me to share that. A Conversation with Sandra Kroupa, University of Washington Book Arts and Rare Books Curator In this interview I asked her to take up the role of a book curator directly. The final product is a cooperative effort, excerpted and edited in May 2007 from a longer transcribed interview from March 2005. Here, we talk about how the collections began and her ongoing role as a simultaneous supporter of artists and academics; about questions of access and user control and how libraries compare to museums; and how, in terms of access, the artwork that is “the book” holds a unique place in our culture. At the intersection of our work in education, we discuss the relatively unacknowledged cultural power of choosing a collection of texts for others, whether for a library or for a course syllabus. Finally, Sandra speaks to how the job of curating feels from the inside. How does her sense of her work—The Collection—compare to what painters or writers might feel looking back on their creations? For, although Sandra herself might protest, an aesthetic collection developed under the oversight of one person for forty years is, itself, nothing less than a work of art.Invisible Culture Issue 11: Curator and Context

Rosée

thanks to David Mattison at The Ten Thousand Year Blog

My only home in Canada was Toronto and when I moved there in 1968 it felt harshly backward and repressive. But that quickly changed. Meeting bp Nichol in 1969 and forming the Four Horsemen in 1970 helped me contextualize my practice and learn about the scene. With the Vietnam War driving loads of American poets to Canada, Toronto felt something like a 1916 Zurich at the time of the birth of the Dada sound poem. Then, of course, there are the Montreal Automatistes in Quebec (banished by Bréton from mainstream Surrealism) who preceded the birth of the Horsemen. Sound poetry arose as collective sound poetry in Toronto. Curiously it never really happened in the States. Charles Amirkhanian was doing a bit of work and Bliem Kern, but nothing that was comparable to the Horsemen. Although in England there was Bob Cobbing’s work and sound poetry collectives in England, such as JgJgJgJ, and in Europe a tremendous amount of sound poetry, but it manifested predominantly as the practice of individual people rather than as collective, group performance. As to why, I can’t answer, maybe something in Toronto in the 1970s, but I can speak to coming from England in 1968 and feeling this terrible pressure as an artist to contribute to the dissemination of national identity. I welcomed bill bissett’s publishing ventures, and bp Nichol’s too, which were (like Eshleman’s) established on a loose editorial policy of national alongside international content. (Czech poets like Jiri Valoch were being published alongside my work and that was personally very liberating.) The enlarged cartography, and the fact that both sound and concrete poetry emerged as international phenomena, was what I found attractive.

There to celebrate Pohrt were guest authors Andrea Barrett and Gary Snyder, both of whom read on Thursday evening. On Friday, there were three panels: Literary Publishing, Writing in the Schools, and From Page to Screen. We were able to attend Literary Publishing with Sven Birkerts, Editor of Agni, Michale Wiegers, Executive Editor of Copper Canyon, and Rebecca Wolff, Editor and Publisher of Fence Magazine and Fence Books.

What It's NotKaren Kevorkian - Eight Poems

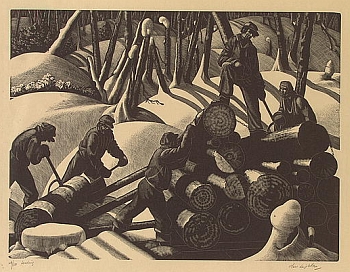

dug out

In this final season of David Simon’s The Wire, we see the dystopic contemporary Baltimore created by the class war from above. It’s a city ravaged by “quality management,” the same philosophy that administrations across the country have adopted in shunting the overwhelming majority of college faculty into contingent positions.How The University Works Marc Bousquet

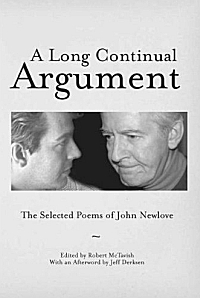

The Weather  John Newlove

Dance of Words: The poetry of John Newlove Paul Vermeersch on John Newlove Newlove never attempted to hide his disappointment with the world, at least not in his poetry. He often expressed an antipathy that many people feel but lack the nerve to express themselves. He was the pinch-hitter for our secret bitterness, the darker and more forthright part of our conscience. His raw material was the ugly truth; from it he forged poems that demonstrate the intrinsic beauty of all human emotions, not just the comfortable ones, and he understood, as Aristotle and Shakespeare did, that the grandest of them all, the most poetic, is our melancholy. Few have given voice to human sadness as eloquently as Newlove did, as he demonstrates in his poem She:She starts to grow tears, chemical beast

waiting

The Double-Headed SnakeThree poems

Premonition

While imbecilic reactionaries still hold forth on and against an aesthetic critique of all this, and believe themselves lucid and modern when they affect to marry their century by proclaiming that the super-highway and Sarcelles have their own beauty, which one must prefer to the discomfort of the "picturesque" old neighborhoods, or by gravely remarking that the entirety of the population eats better, despite those nostalgic for good food, the problem of the degradation of the totality of the natural and human environment already completely ceases to pose itself on the plane of so-called ancient quality, aesthetic or otherwise, and radically becomes the problem of the material possibility for existence of a world that pursues such a movement. This impossibility is in fact already perfectly demonstrated by all of separated scientific knowledge, which now only discusses the expiration [date] and the palliatives that, if one applies them diligently, can slightly delay it. Such a science can only accompany to destruction a world that has produced it and has it, but is forced to do so with open eyes. It thus shows, to a caricatural degree, the uselessness of knowledge without use.(...)  Clare Leighton

Dubai is certainly the inevitable place for the realization of Koolhaas’ ideas. It is by now the capital of an economic and political New World Order. A city-state without income taxes, labor laws, or elections, it is ruled by a corporate oligarchy of hereditary rulers, accountable only to themselves and their investors. Quite a model for the global future. Built up rapidly over the past few years on the wealth gotten from the world’s greed for oil—and more recently as an unregulated sanctuary for cash—it has no depth of history or indigenous culture, no complexity, no conflicts, no questions about itself, no doubts, in short, nothing to stand in the way of its being shaped into the ultimate neo-liberal Utopia.City on the Gulf: Koolhaas Lays Out a Grand Urban Experiment in Dubai

Fear and Money in Dubai [PDF]

L'Archive du Mal

via if:book

A materialist turn in the humanities and social sciences has revitalized work in feminism, science and technology studies, critical social theory and phenomenology. Nonetheless, we want to ask what’s at stake when ‘race’ is grasped from a materialist standpoint? Is the focus on materiality able to track and unravel the manifold neo-racisms of contemporary globalization? Does it supersede the limitations of social constructionist accounts of race? And could a materialist ontology of race transform and invigorate anti-racist praxis? We are living through an intensification of citizens’, and non-citizens’, visibility to capital. Database convergence, states of emergency and points-based immigration systems destroy the legal and informational grey zones in which the poor shelter and organise. As black economies and shadow sectors are exposed to the light of networked information in the interests of population management, border enforcement, welfare clamp-downs and, above all, profit, what are the risks and advantages of visibility? What do (political and artistic) representation and rights have to offer the illegal and ‘invisible’? Frontiers considers limits, edges, borders and margins of all kinds as the sites for declarations, occasions for conversation, arguments, debates, recounting and reflection. Our book suggests that you consider the frontier as the skin of our time and our world, and we invite you to get under the skin of contemporary experience in order to generate a series of crucial (and frequently unsettling) narrative and analytical possibilities.

Abendland

Noon rings out. A wasp, making an ominous sound, a sound akin to a klaxon or a tocsin, flits about. Augustus, who has had a bad night, sits up blinking and purblind. Oh what was that word (is his thought) that ran through my brain all night, that idiotic word that, hard as I'd try to pun it down, was always just an inch or two out of my grasp - fowl or foul or Vow or Voyal? - a word which, by association, brought into play an incongruous mass and magma of nouns, idioms, slogans and sayings, a confusing, amorphous outpouring which I sought in vain to control or turn off but which wound around my mind a whirlwind of a cord, a whiplash of a cord, a cord that would split again and again, would knit again and again, of words without communication or any possibility of combination, words without pronunciation, signification or transcription but out of which, notwithstanding, was brought forth a flux, a continuous, compact and lucid flow: an intuition, a vacillating frisson of illumination as if caught in a flash of lightning or in a mist abruptly rising to unshroud an obvious sign - but a sign, alas, that would last an instant only to vanish for good.excerpt from "A Void"  Georges Perec Warren Motte Georges Perec is perhaps best described as a literary experimentalist, one who was intrigued by the question of form. He produced a score of major works, each one quite different from the others. Although he is best known for his novels, he also wrote plays, poetry, essays, filmscripts, opera librettos, and many other texts which confound traditional generic categories. "My ambition as a writer," he explained to an interviewer in 1978, "would be to traverse all of contemporary literature, without ever feeling that I am retracing my own steps or returning to beaten ground, and to write everything that someone today can possibly write." He once suggested that his work was animated by four major concerns: a passion for the apparently trivial details of everyday life, an impulse toward confession and autobiography, a will toward formal innovation, and a desire to tell engaging, absorbing stories. Anyone wishing to read Perec today may consider those four concerns as paths that may be followed through his otherwise labyrinthine oeuvre--and indeed I shall walk them here, revisiting briefly certain texts that seem to me exemplary of Perec's literary vision. special issue and thread at the Electronic BookReview

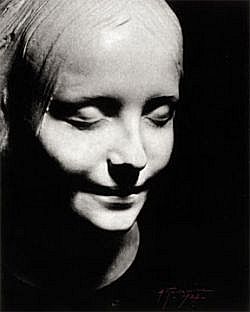

Influence and authenticity of l'Inconnue de la SeineA figure that disturbs me, since I have met her too, but during the day, diurnal and spectral. Messenger of Melancholy, so similar to the apparition evoked by Henry James in The Turn of the Screw, motionless like a woman conscious of her guilt, slighjtly turned away so that we can escape from the memory of our own guilt.A Voice from Elsewhere Anja Zeidler In the The Savage God. A Study of Suicide Al Alvarez writes: "I am told that a whole generation of German girls modelled their looks on her," to add in a note: "I owe this information to Hans Hesse of the University of Sussex. He suggested that the Inconnue became the erotic ideal of the period, as Bardot was for the 1950s. He thinks that German actresses like Elisabeth Bergner modeled themselves on her. She was finally displaced as a paradigm by Greta Garbo."

A new body appeared in Britain in the late eighteenth century, one marked by its susceptibility to hysteria and a host of related nervous conditions, variously called hypochondria, spleen, vapours, lowness of spirits, melancholia, bile, excess sensibility, or, simply, nerves. These complaints were not themselves new; they had previously been the exclusive province of the English aristocracy. But their appearance as an epidemic in the middle class of the late Georgian years reflected a new set of assumptions about the bodies of speculators, traders, and businessmen and their wives, daughters, and servants. As a consequence, nervous disorders such as hysteria became the leading category of illness, accounting for two-thirds of all disease, and the new middle-class nervous body was viewed with considerable alarm.(...)Part of eScholarship Editions

The Ecology of the Novel

Behemoth  Blankenberg

War Papers (2)Some Wars Are Silent Chris Mansell some wars are silent there are no bridges the mist falls to the ground and the songs of the missing have long died the country mimes its history the eucalypt the water the mountain stand alone there is no afternoon where flesh comes together where the stories of the ten thousand years comes where the clapstick sings out here history is silent and the wars are not acknowledged we are deprived of heroes fools and lessons our history settles on the grass like an old man sitting down some wars are silent and there are no bridges

A figure that disturbs me, since I have met her too, but during the day, diurnal and spectral. Messenger of Melancholy, so similar to the apparition evoked by Henry James in The Turn of the Screw, motionless like a woman conscious of her guilt, slighjtly turned away so that we can escape from the memory of our own guilt.Jean Baudrillard at ctheory

In the era of psychoanalysis, we all of course speak, and we can always go on speaking, about the "successful" work of mourning-or, inversely, as if it were precisely the contrary, about a "melancholia" that would signal the failure of such work. But if we are to follow Louis Marin, here comes a work without force, a work that would have to work at renouncing force, its own force, a work that would have to work at failure, and thus at mourning and getting over force, a work working at its own unproductivity, absolutely, working to absolve or to absolve itself of whatever might be absolute about "force," and thus of something like "force" itself: "a work of mourning of the absolute of 'force,"' says Louis Marin, keeping the word "force" between quotation marks that just won't let go. It is a question of the absolute renunciation of the absolute of force, of the absolute of force in its impossibility and unavoidability; both at once, as inaccessible as it is ineluctable.

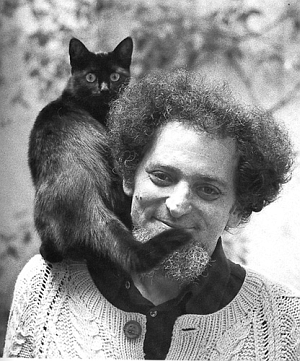

Some poems arrive as dreams. Others being from memories. Some start out of the middle of a conversation I’m involved in or words that I overhear other people speaking. An imagination of the life of some historical person may occur to me: I may suddenly suppose I understand what it felt like to be Johannes Brahms on a particular morning of his life. A landscape, a cat, a relative, a friend, a letter (or the act of answering a letter), walking, the unexpected receipt of a new poetry magazine full of work by new young writers, the arrival of a new book of poems by a friend or somebody I don’t know personally; re-reading Shakespeare or reading Emily Dickinson on the streetcar and suddenly moved to tears; shopping for vegetables, making love, looking at pictures, taking dope, sitting still and looking at whatever is happening in front of me, getting haircut, being afraid of everybody and everything, hating everybody, playing music, going to parties, visiting relatives, riding in trains, buses, taxis, steamboats, riding horses, getting drunk, dancing, praying, practicing mediation, singing, rolling on the floor, losing my temper, looking for agates, arguing, washing sox, teaching, sweeping the floor, operating this typewriter right now (bought in Berkeley 12 years ago and wrote ten books on it) which the cicadas and taxis all sing in ravening hot Japanese summer 1967 . . . all this is how to write, all this is where poems are to be found. Writing them is a delight.  Philip Whalen

On The Publication of Philip Whalen's Collected Poems

The Brain, within its Groove

One Week at War in Iraq and Afghanistan for $3.5 Billion

Better Than FreeEven a dog knows you can't erase something once it's flowed on the internet. Kevin Kelly The internet is a copy machine. At its most foundational level, it copies every action, every character, every thought we make while we ride upon it. In order to send a message from one corner of the internet to another, the protocols of communication demand that the whole message be copied along the way several times. IT companies make a lot of money selling equipment that facilitates this ceaseless copying. Every bit of data ever produced on any computer is copied somewhere. The digital economy is thus run on a river of copies. Unlike the mass-produced reproductions of the machine age, these copies are not just cheap, they are free.

via Crag Hill

In the Mountains

War CrimeNerves Anne Waldman Crime's the way you walk the way you talk crime's the way you get away with it not seeing arrogance, narcissism my god & all his prowess on my side. What mastermind of machinery to make sure suffering is not yet death, not enough to die without the torture chamber's cry. The crime is in the pudding in the picture, on any screen that will play. Drama of infrared music, you want to shout in the disco before you tumble, night after night you are not in control with your signal of error with your signals of terror with your action deferred with your faulty warning system. You are not in control with your pilot warning rhizome with your human bomb attuned to readings in philosophy. Nietzsche could still rule your mind not hope of loving a virgin not to be confused with the word raisin. In heaven: raisins. Raison d'etre, to be greeted by virgins who are like the raisins in heaven. Crotches, nipples of Sweet fruit? This is not a fine-tuned translation. But never going on your nerve underestimate the mind of a revolutionary man, a revolutionary one. Anarchy is sweet revenge and you get what you want, this act of "faith": war.(...)Civil Disobediences: Poetics and Politics in Action Anne Waldman, Lisa Birman

In the Room of Never Grieve: New and Selected Poems, 1985-2003

Colors in the Mechanism of Concealment 2004 Rachel Blau DuPlessis Anne Waldman’s work in poetry exists at the intersection of activist passion, gender critique and wariness, and long poem ambitions. She is at root inspired by an Olsonic ambition to speak the whole social fabric as an incantatory, analytic cantor in shamanic voice. She is someone who can inhabit her own culture and play among a multiple of global sites with Blakean transformative lust. She calls us to account whenever she takes the witness stand: “Will some future generation look upon the ravages of the planet and the perpetuation of suffering by the powerful over the weak as a Second Holocaust? And see that no one attempted to stop the madness?” Thus she stands corporeally in her time, in Ernst Bloch’s phrase. Many of her poetic works present illuminating political outrage about the continuing crisis of failed social justice across the world. She flays power with words, ignoring or disdaining voices that say such gestures are impossible.Anne Waldman feature in Jacket

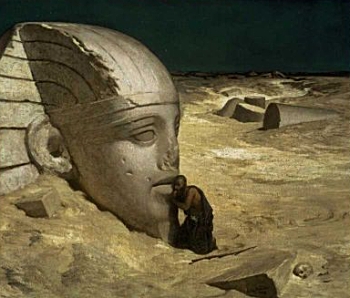

The Questioner of the Sphinx

The modern Questioner still asks, but Vedder's sphinx is blank and silent. For Leigh Eric Schmidt, in his fascinating new book, Hearing Things: Religion, Illusion, and the American Enlightenment, Vedder's stark vision of spiritual alienation is emblematic of "the oracular silences that had descended upon some modern listeners" (130). Enlightenment science and modern rationality re-tuned the ear, nullifying what were once considered to be the voices of oracles, angels, or God as trickery or madness. But that is only half of the story, for even in today's secular America millions still claim to hear divine voices and supernatural sounds. Schmidt's book traces the complex relationship of these two historical processes: how modern science disciplined aural perception, and how popular spiritual practices that place a premium on spiritual "hearing" persisted nonetheless.

Shmuel, the chronicler: Memory...everything is in memory. .....

After all the pretty contrast of life and death

Stones and Clouds

Poems Denise RileyThe Castalian Spring Denise Riley 11 Could I try on that song of my sociologised self? Its Long angry flounce, tuned to piping self-sorrow, flopped Lax in my gullet – ‘But we’re all bufo bufo’, I sobbed – Suddenly charmed by community – ‘all warty we are’. Low booms from the blackness welled up like dark liquid Of ‘wart’ Ich auf Dich.’ One Love was pulsed out from our Isolate throats, concertina’ed in common; ‘Du mit Mir’ was A comforting wheeze of old buffers, all coupled, one breed. 12 But then I heard others, odd pockets of sound; why wouldn’t these Claim me to chant in their choir? As I grew lonelier I got philosophical, Piped up this line: ‘Don’t fall for paradox, to lie choked in its coils While your years sidle by.’ Some hooted reproachfully out of the dawn ‘Don’t you stifle us with your egotist’s narrative or go soft on “sameness”, We’ll plait our own wildly elaborate patterns’ – they bristled like movies By Kurosawa. By then I’d reflated, abandoned my toadhood, had pulled on My usual skin like old nylons. I drifted to Delphi, I’d a temple to see. Denise Riley

The Words of Selves: Identification, Solidarity, Irony ... the sotto voce laments for regretted beauty I have outlined here are clichés of feeling. Their tone is formulaic, sentimental, complacent, swathed in the nostalgia emerging from the effort to envisage oneself as one once was, an effort driven by our will to be flattered. As descriptions of how their speakers actually were, their truth value is at best shaky. But these ordinary utterances are, above all, linguistic structures of feeling. As such, their effectiveness rests on their apparent weaknesses, their bagginess and their porosity; these allow them to be open to everyone. Through their looseness their usefulness can emerge: that imprecision and inelegance which actually “speak volumes” in fostering the ability of the merely implied to become the perfectly understood, and in admitting the deep intelligibility of the not-said.archive : s0metim3s has liberated some more quotes from Diacritics

From Odes: 15 [“Nothing”]  Basil Bunting

Complete Poems By Basil Bunting Chomei at Toyama and Villon by Basil Bunting Richard Caddel Read these poems aloud: Bunting's central statement on poetry, as significant today as it was when first published in 1966, is that "poetry, like music, is to be heard." As a statement, this has been picked over, carped at, qualified and explained away by critics ever since, so that it's worth restating it here, in its original, radical essence:"Buffalo 1963: Reading""Poetry, like music, is to be heard. It deals in sound - long sounds and short sounds, heavy beats and light beats, the tone relations of vowels, the relations of consonants to one another . . . Reading in silence is the source of half the misconceptions that have caused the public to distrust poetry."Such a conviction was deeply rooted in his upbringing and development, and was the product of a lifetime's practical experience. Basil Bunting Audio at the Slought Foundation

production via Jörg Colberg

An Anthology of Bay Area Women Writers fromPoems by Sharon Doubiago

Lang/scapes: Poetry, in many ways, and through its many minions, has refused to roll over and keep dreaming. It has bolted upright, and gotten out of bed—that is, off the page—and into other spaces where people don't usually expect to find it. In the conclusion to my book-length investigation of war resistance poetry, Behind the Lines: War Resistance Poetry on the American Homefront Since 1941, I returned to a persistent motif—a post-Gutenbergian call to see poetry breathe outside of the confines of the book, and for us to see poetry freed into the third dimension of public spaces: "war resistance poems thus ask for our redeployment in multiple sites, returning poetry to where it thrives—at the local and in local resistance [i.e. "behind the lines" and beyond the page and into the public square]—as graffiti, in pamphlets, as performances, as songs, and in the classroom" . This poetry invites usBehind the Lines: Poetry, War, & Peacemakingto pose further questions not only about the limits of the individualized poem, but also about the individualized poet, and propose ways that poets and activists might work to find ways of making poetry "active" again, and making activism a labor of making as much as a labor of protest and unmasking. Thus, the survival of war resistance poetry depends not just on the aesthetic value of the poems, but also on what these poems offer as cultural productions. War resistance poets attempt to address both the converted and unconverted, to praise the committed and also to hail the unconverted, inviting them to partake in this collective subjectivity of resistance.Though books clearly can be liberatory sites for poetry—as they have been for so many readers of poetry over the centuries—the culture of poetry, in our post-Gutenbergian age, remained mostly a culture of the book only, to the detriment of poetry's vital relationship to orality, to performance, to bodily instrumentation.

Call it another strategy for resisting forgetting or creating resistant counter-memory. Call it the forging of a public space under difficult circumstances! For those far from the academic milieu, believe me: it is not so easy to find a space to gather and talk openly in. This not only compounds but is directly linked to the exclusion of poor and disadvantaged folks from this space. My friends and I needed very badly to do our resistant thinking in a public and shared space, to carry what had been private, personalized, and thus almost necessarily sort of paranoid and alienated talking into a public space where it could be transformed in dialogue with others.

via Al FilreisThere Is Guillaume Apolinaire translated by Michael Benedikt .... There is this inkwell which I've made from a 150 mm shell I saved from shooting There is my calvary saddle left out in the rain There are all these rivers blasted off their courses which will never go back to their banks There is the god of Love who leads me on so sweetly There is this German prisoner carrying his machine-gun across his shoulders There are men on earth who've never fought in the war There are Hindus here who look with astonishment on the occidental style of campaign They meditate gravely upon those who've left this place wondering whether they'll ever see them again Knowing as they do what great progress we've made during this particular war in the art of invisibility

production

Green one-year anniversary issue

Roy Andrews

from Pierre Joris ...we ... are the inheritors of two opposed visions: on one hand, that of, say, Shelley and Whitman, Neruda and Ginsberg, for whom poetry was in some, and often in large, measure a means of protesting social injustice, and from whom we have inherited a believe in the possible efficacy of the poem to do just that – the poet as unacknowledged legislator, the poet as guide, as shamanic propagandist for a better world. On the other hand we are also the inheritors of Mallarmé – and his sense that “poetry makes nothing happen” as a sticker I was handed some time back proclaims. As Alain Badiou recently phrased it, Mallarmé gave the 20th century another figure, that of the “poet as secret, active exception, as the custodian of lost thought. The poet is the protector, in language, of a forgotten opening… the poet, ignored, stands guard against perdition.” Which often leads to an ahistorical or nostalgic aestheticism. But of course Mallarmé also gave us huge breakthroughs in poetic form and in that sense renewing and revitalizing poetry for the last century. So what we need for this new century is a poetry that combines the advances of those two figures, the poet as avant-gardista and the poet as custodian. A difficult dance, to be sure.

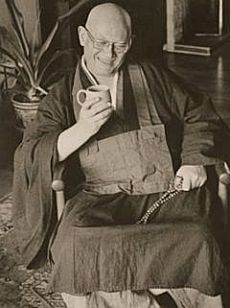

Gary Snyder on Ecology and Poetry

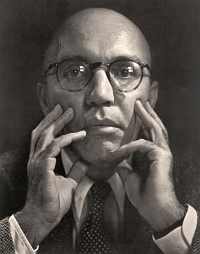

Kurt Julian Weill

Very Contemporary, Goya

The BBC reported these words with approval. It's nice to know that this is what is considered normal for a young man in the UK. I guess it is normal to send 23 year olds to join an illegal occupation army. It is normal to call in air strikes (this was Harry's job) to drop 1000-pound bombs on villages killing and destroying men, women, children, animals. It is normal to go on foot patrol in an occupied country and look down with contempt on the poor people of the country and it is normal to feel the hatred emanating from the people of the occupied country."It's very nice to be a sort of normal person for once, I think this is about as normal as I'm ever going to get."

Entr’acte

The state of global affairs has long passed the proverbial tipping point and is more likely flirting with the dreaded point of no return. Yet most folks, it seems, have confused the occasional weekend parade, I mean, protest with a full-blown movement.

The dichotomy between the civilized, uniformed, chivalrous combatant and the opportunistic, treacherous barbarian is a false one. Perhaps there is something in the argument that all people, fundamentally 'good' people included, are capable of doing bad or evil acts given certain circumstances. Just as 'bad' people are capable of random acts of kindness.

War is a church.

from "October 27, 2003"The Groves of Lebanon

Entr’acte Entr’acte

The 'guinea-pigging' of vast swathes of the population has, up till now, solved two problems: the 'time' problem (namely, how to avoid addressing the underlying reasons for mental health problems), and how to create new markets amidst the flourishing of generic drug production, particularly outside of the US and Europe. Clearly the interiorisation of unhappiness is far more profitable than the outward realisation that perhaps misery has nothing to do with you personally and everything to do with the world in which you live. Materialism of the Other Spurious on Levinas and Blanchot 'No human or interhuman relationship can be enacted outside of an economy; no face can be approached with empty hands and closed home'. The circulation which seems to be permitted by a domestic space (Levinas calls this economy) is broken by the relation to the Other. The space into which I am welcomed becomes immediately a space of hospitality. Note that hospitality bears upon what my dwelling has allowed me to make into a possession - it is a giving of what I have wrested from the element. Hospitality has a material content. As Blanchot writes in another context, reflecting, no doubt, upon his reading of Levinas:Great is HungeringMaterialism: 'my own' would perhaps be of little account, since it is appropriation or egoism; but the materialism of others - their hunger, their thirst, their desire - is the truth of materialism, its importance.I am never allowed to tend complacently to my own hunger, my own thirst; my desires are, from this point no longer my own, since they come from without. Although I may indeed decide to follow only those desires I take to be mine, this is a movement of reaction. Appropriation and egoism have already been challenged; the hunger of the Other - his thirst, his desire - has already laid claim to me in dwelling.

Lamentation over the

The Quay LembourOCTOPUSMAGAZINE#1O

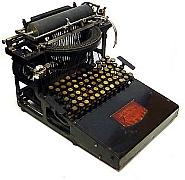

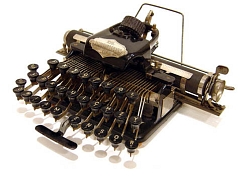

I ask you to try to reach the type, the eidos of a typewriter through imagination. ...(...)   Strange as it seems to us today, all the most successful machines up to 1900 were understrokes, or as their detractors called them, "blind writers." All these decisions had serious consequences for the nature of the activity of typing. Here we should not be misled by the fact that the final product produced on all these machines would look similar (though not identical). Even if the results are similar, the activities can be very different. Typing on a big understroke with a double keyboard, like the Caligraph, is not the same as typing on a portable with three rows of keys, like the Blickensderfer, which produces immediately visible writing and uses interchangeable typewheels.

The Collected Poems of Howard Nemerovfrom

The Selected Poems of Howard Nemerov

Children of Light

Landscapes of Presence

Epilogue Those blessèd structures, plot and rhyme-- why are they no help to me now I want to make something imagined, not recalled? I hear the noise of my own voice: The painter's vision is not a lens, it trembles to caress the light. But sometimes everything I write with the threadbare art of my eye seems a snapshot, lurid, rapid, garish, grouped, heightened from life, yet paralyzed by fact. All's misalliance. Yet why not say what happened? Pray for the grace of accuracy Vermeer gave to the sun's illumination stealing like the tide across a map to his girl solid with yearning. We are poor passing facts, warned by that to give each figure in the photograph his living name. Robert Lowell

lantern slide

| |