|

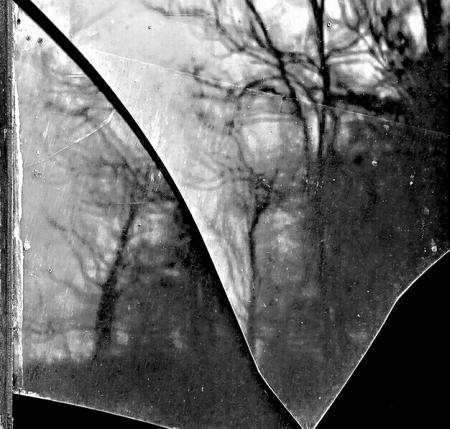

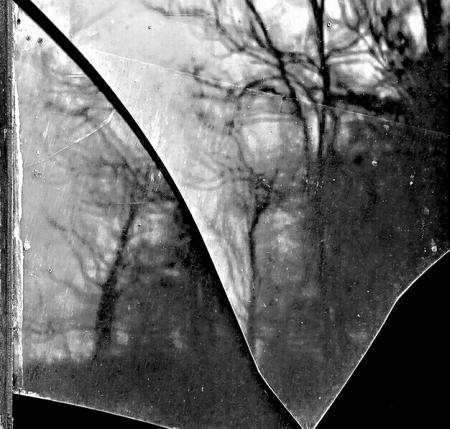

Harry Callahan

d. March 15, 1999

_______________________

Interview With Franco ‘bifo’ Berardi

(....)

You see, you and I are not rewired. We have been wired by our body relation with the mother, human beings speaking a language which is the language of ambiguity — the language of mutual understanding. This is not about us, it’s about the connected generation. I think that the connected generation is increasingly entering a dimension where the possibility of deep conjunctive understanding is over because the connective generation is affectively deprived, affectively depleted, because the presence of the mother is almost ‘dissolving’. Not only the physical presence of the mother but the mental presence of the mother, because the precarious worker, the cognitive worker and particularly the feminine precarious worker is totally absorbed. Twenty-four hours a day, even when sleeping, one is absorbed by the social investment of affective and intellectual energies. So the presence of the mother is sort of dissolving, disappearing, and is increasingly replaced by the presence of the screen, by the presence of the connective tools. Well, yes, I think that there is a philosophical problem in it, which is concerning the concept of post-human. Can we really speak of post-human? I am not sure because the concept of human is so impossible to define, that I cannot say beyond the human. It is human, everything is human. But it is post-conjunctive. Post in the sense of, a form of communication in which the human ambiguity is lost, and if you lose ambiguity you lose everything.

...(more)

_______________________

‘The child is father to the man.’

How can he be? The words are wild.

Suck any sense from that who can:

‘The child is father to the man.’

No; what the poet did write ran,

‘The man is father to the child.’

‘The child is father to the man!’

How can he be? The words are wild!

-

Gerard Manley Hopkins

_______________________

Growing Old

GJV Prasad

In English he became someone's old man early

It took time in his Indian languages

But as he grew older and more respected not in English

English kept him young and with it

His wisdom he gained in years not in English

Alzheimer's stared at him in English

Soon he realised

He was growing old and unwanted

In English

And not in English

Anthology of Contemporary Indian Poetry II

Edited by Menka Shivdasani Big Bridge 18

_______________________

Harry Callahan

_______________________

Recounting Signatures: A Review of James McFarland’s Constellation

Donald Cross

electronic book review

The task that James McFarland sets for himself in Constellation: Friedrich Nietzsche and Walter Benjamin in the Now-Time of History (Fordham, 2013) is, in short, impossible. This is not a critique. On the contrary, not only is McFarland aware of the difficulties involved in positing any congruence between the thought of Nietzsche and that of Benjamin; the book’s impossibility is its impetus and even makes it necessary. There are at least three general difficulties that, even if Nietzsche’s influence on Benjamin is often remarked, have led to a certain scarcity in scholarship on their relation.

The first difficulty is circumstantial. Appropriations of Nietzsche by National Socialism, largely facilitated by editorial decisions concerning Nietzsche’s archives (for which Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, McFarland is careful to point out, is less responsible than often thought), created an apparent antagonism between Nietzsche and Benjamin, a thinker of Jewish Messianism, and made a genuine encounter unlikely.

The second difficulty takes shape after the early abuses of Nietzsche begin to dissipate thanks to landmark commentaries in the sixties like Gilles Deleuze’s Nietzsche and Philosophy. If, however, the second difficulty is more substantial than the first, it is still essentially limited. Between, on the one hand, Nietzsche’s invectives against religion and politics in virtually every form and, on the other, Benjamin’s reflections on Messianism and apparently communist commitments, the only intersection possible between the two thinkers seems to be either critical or forced.

If the first two difficulties make an encounter between Nietzsche and Benjamin unlikely, the third makes it rigorously impossible. A relationship between Nietzsche and Benjamin cannot be founded upon Nietzsche’s philosophy because, above all, Nietzsche’s philosophy cannot be reduced to the unified content necessary for relating it to another in any traditional sense. From one perspective or another, Nietzsche’s notoriously unsystematic writings never praise without critiquing or critique without praising.

...(more)

_______________________

Harry Callahan

_______________________

The Hostile Situation of Hope

Essay by Jared Daniel Fagen

Some of the greatest innovations in modern literature have arisen in the aftermath of tumultuous occasions, awakening in us spiritual dilemmas that stir striking questions concerning our position within the world. Feeling abandoned, and unable to comprehend ourselves within traditional philosophical and historical frameworks, we reach instead toward more inward aspects—the irrational and incomprehensible.

Emil Cioran’s “organic man” is raised on these ruins. Faced with failing structures of knowledge and a human consciousness that has long been corrupted by order, ambition, and abstract constructs, Cioran returns us to a more primitive, fundamental mode of being; it stems from a “vital imbalance” rather than intelligence or reason. From this place of inner tension, he reveals a fragmented, anti-systematic expression of anguish: a result of thought’s own inability, and reluctance, to chart a direction toward its end, its completion. The circumstance of despair, therefore, replaces logic—or linear thought construction—as the state by which we launch investigations into ourselves. But while despair is a consequence of disorder, it also acts as a catalyst for the exploration of subjectivity and self-consciousness that reside outside of historical, cultural, and philosophical truths.

If Cioran seeks refuge in the cages of his own mind in order to sever thought from preconceived truth, Alain Robbe-Grillet endeavors to reinvent the novel in an attempt to disengage from what he terms the “sclerosis” of historical art forms. Considered the foremost theorist of the nouveau roman (“New Novel”), Robbe-Grillet argues that literature has no purpose other than to just exist. In rejecting the traditional novel, which assigns meaning to the world through schematic structures like the Freytag triangle, Robbe-Grillet positions the writer as a sort of “organic man” who, in his isolation and excavation of the self, forms no relationship with the world. Thus, the condition of despair in the works of Cioran, and the possibilities for a more meaningful expression of subjective experience outlined in Robbe-Grillet’s collection of essays, Pour un Nouveau Roman, both function as a means to distance the self from a consciousness that, while still endemic, has become tarnished.

...(more)

The Quarterly Conversation Issue 43 - Spring 2016

_______________________

Harry Callahan

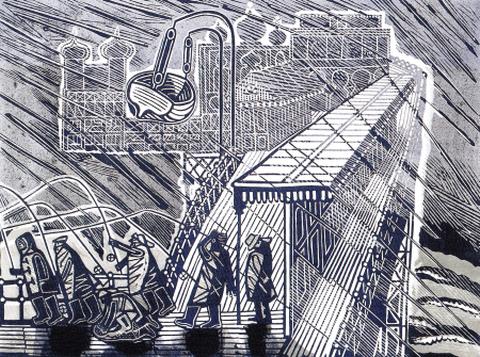

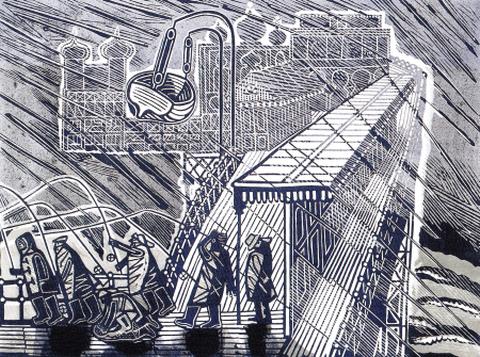

The Rookery

Edward Bawden

1903-1989

_______________________

Engaging Lyn Hejinian [an inter-chapter]

Donald Wellman

The vortex, as understood by Ezra Pound, is a figure of sustained energy, a form dependent on the concentration of the reader and transmitting immanent sources of coherence, a collective imagination embodied in gods and goddesses, figures for all that is sacred but whose effects escape ordinary language. Contiguous to the plane of immanence are multiplicities: presences remembered from a life lived with care and sincerity, as well as the luminous details associated in memory with those persons. Within the realm of such subjectivity as Pound’s there is no necessary correlation with social fact. His are authoritarian fantasies, a solipsism on a cosmic scale like that to which Ahab and his crew were victims. The correlation and assessment of social fact are central to language-based procedures of many contemporary poets, many of whom are indebted to Ezra Pound for his contributions to the invention of open form. Early in her career Lyn Hejinian wrote, “The text is anterior to the composition, though the composition is interior to the text.” That anterior text disclosed in postmodern or deconstructive philosophy is also signaled by the role of sacred books in pre-literate societies, where the printed word contains clues to wisdom and fate. Maria Sabina invoked her little people who taught her to read when she had entered a trance state, for instance. In Hejinian’s poetry the work occurs at the obscurely demarcated boundary between exterior or antecedent, interior and present conditions of life.

In the “The Rejection of Closure,” she wrote, “The impasse … that is both language’s creative condition and its problem can be described as the disjuncture between words and meaning, but at a particularly material level … Writing’s forms are not merely shapes but forces; formal questions are about dynamics—they ask how, where, and why the language moves , what are the types, directions, number and velocity of a work’s motion. The material aporia objectifies the poem in the context of ideas and of language itself”. The “open” text as opposed to the “closed,” she assert allows multiple readings. Her familiarity with Deleuzian and Spinozistic thought is evident from her word choice. Her own synopsis of the meaning of this fundamental essay appears on the Poetry Foundation website.

In “The Rejection of Closure,” I give no examples of a “closed” text, but I can offer several. The coercive, epiphanic mode in some contemporary lyric poetry can serve as a negative model, with its smug pretension to universality and its tendency to cast the poet as guardian to Truth. And detective fiction can serve as a positive model, presenting an ultimately stable, calm and calming (and fundamentally unepiphanic) vision of the world. In either case, however pleasurable its effects, closure is a fiction, one of the amenities that falsehood and fantasy provide.

...(more)

immanent occasions

_______________________

Alberto Burri

b. Mar 12, 1915

_______________________

The Future of Genius

Robert Archambeau

If one were to shout the question “who is a literary genius?” in the general direction of a gaggle of young men in Warby Parker glasses and Chuck Taylor sneakers, the air would likely resound with shouts of “David Foster Wallace!” much to the chagrin of Jonathan Franzen, should he skulk within earshot. But what is meant by the term genius? And how much longer will it be with us? The term, after all, sits more easily with the Romantic poet in his garret than with the writer of our moment, recycling found text on her Twitter account, and thinkers and artists from Walter Benjamin to Damien Hirst have sought to consign the term to the dustbin of critical history. Indeed, should you punch the word into Google’s ngram viewer, you’ll see a slow decline in frequency of usage since 1800, with a steepish drop between 1970 and 1980 before a more recent leveling off. One wonders, then: does genius have a future in our understanding of literature? Or is the genius to be taken to Roland Barthes’ graveyard and buried in state, next to his less-distinguished peer, the author?

...(more)

Bodyvia the page

_______________________

Alberto Burri

_______________________

As The Snow Melted

Ivan Wernisch

translated by Jonathan Bolton

They appeared as the snow melted

Those who had perished in the last days of March,

Then those from the February skirmishes, followed by the dead of January

In the end there were also several who had fallen in November

The fewest in number, because there were still burials back then

Everyone waited together in the matted, golden-brown grass

And finally here was the river

One morning steam rose from a ship at the small wooden pier

It had brought chickens in cages, live pigs

The road to the city was open

I began to think of escape The Czech Issue - Body

_______________________

‘Dying for Free’

Mahmoud Darwish

Translated by Naser Albreeky

presented by Pierre Joris

Autumn passing through my flesh as a funeral of oranges..

coppery moon crumpled by minerals and sand

children falling in my heart upon the souls of men

all the pain is my share..not everything is being told…

...(more)

_______________________

Edward Bawden

_______________________

Slow Thinking

An Unnatural Pursuit

Anna Badkhen

guernica

Fast-paced, on unmarked paths, my walks through the West African bush took four hours, maybe more. I never carried a watch. The point was to lose track of time, maybe even of the path that traced faintly through the pointillist savannah. Mostly, the point was to lose track of the cognitive rush that accompanied every arrival.

At the beginning of each walk lay a camp of nomadic Fulani cattle herders who lived and migrated in the crook of the Niger River’s bend, on land that was more than two billion years old. It was the quintessence of open space. You could picture mammoths on it. You could picture dinosaurs. Its antiquity seemed to magnify its size. So, too, did the sparseness of the campsites: a few reed mats, a hearth built with three large rocks, a small herd of Zebu cows sighing under a thorn tree, sometimes a grass-and-thatch hut, sometimes not, and immense, beveled horizons.

At the end of my walks lay Djenné, an 1,100-year-old town in central Mali. Its neo-Sudanic clay walls enclosed 33,000 residents, a busy market, a gendarmerie, a hospital, a jail, mosques, schools, pharmacies, motorcycles, donkey carts, cellphone dealerships, internet cafés, transistor radios, a horde of social obligations, and a myriad problems that required immediate resolution. It was a prototype of the world I often occupy, and so do you: a world so fractionated by pressing responsibilities that it minces the thought process into minute reactionary snippets—the kind of mental busyness the Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls “fast thinking.”

I had come to the Sahel to think slowly.

...(more)

"Andromeda"

2001

Anselm Kiefer

b. March 8, 1945

_______________________

Click.

Jeremy Fernando

berois

… one is photographable, ‘photogenic’,

and this is perhaps the catastrophe,

that one can be photographable,

that one can be captured

and caught in time …

— Hubertus von Amelunxen

… the tragedy of the photographic object, the object that is photographed: that in order to preserve its writing — the writing of light — the object has to be consigned into the shadows of time.

Perhaps then, the only hope for the one being captured is to be photographed without being photographable: not so much that one is not in the photograph (that would be too simple), nor that one is the photographer (too banal), nor even that one attempts to resist being objectified (for, this would be impossible); but that one remains within the photograph … as light.

Where one is nothing other than light writing itself.

Which is not to say that that just because it is light, it leaves no marks: for, no matter how light it might be, might try to be, there is always already weight, a trace. And, this perhaps is precisely why it is the unbearable lightness of being: not because one has to try hard to weigh it down, give it gravitas, meaning even, but that no matter how light it is, regardless of the very abgrund of being, it is always already too heavy, never light enough.

Unless, it is light writing light.

And what remains is not just nothing — in the sense of light writing over itself — but nothingness: pure shining.

...(more)

_______________________

Icarus: Sand of the Brandenberg March

Anselm Kiefer

1981

_______________________

The Spectacle of Disintegration

McKenzie Wark

(....)

And yet the spectacle remains, circling itself, bewildering itself. Everything is impregnated with tiny bits of its issue, yet the new world remains stillborn. The spectacle atomizes and diffuses itself throughout not only the social body but its sustaining landscape as well. As Debord’s former comrade T. J. Clark writes, this world is “not ‘capital accumulated to the point where it becomes image’ to quote the famous phrase from Guy Debord, but images dispersed and accelerated until they become the true and sufficient commodities.”

The spectacle speaks the language of command. The command of the concentrated spectacle was: OBEY! The command of the diffuse spectacle was: BUY! In the integrated spectacle the commands to OBEY! and BUY! became interchangeable. Now the command of the disintegrating spectacle is: RECYCLE! Like oceanic amoeba choking on granulated shopping bags, the spectacle can now only go forward by evolving the ability to eat its own shit.

The disintegrating spectacle can countenance the end of everything except the end of itself. It can contemplate with equanimity melting ice sheets, seas of junk, peak oil, but the spectacle itself lives on. It is immune to particular criticisms. Mustapha Khayati: “Fourier long ago exposed the methodological myopia of treating fundamental questions without relating them to modern society as a whole. The fetishism of facts masks the essential category, the mass of details obscures the totality.”

Even when it speaks of disintegration, the spectacle is all about particulars. The plastic Pacific, even if it is as big as Texas, is presented as a particular event. Particular criticisms hold the spectacle to account for falsifying this image or that story, but in the process thereby merely add legitimacy to the spectacle’s claim that it can in general be a vehicle for the true. A genuinely critical approach to the spectacle starts from the opposite premise: that it may present from time to time a true fragment, but it is necessarily false as a whole. Debord: “In a world that really has been turned on its head, the true is a moment of falsehood.”

This then is our task: a critique of the spectacle as a whole, a task that critical thought has for the most part abandoned. Stupefied by its own powerlessness, critical thought turned into that drunk who, having lost the car keys, searches for them under the street lamp. The drunk knows that the keys disappeared in that murky puddle, where it is dark, but finds it is easier to search for them under the lamp, where there is light – if not enlightenment.

...(more)

_______________________

Glaube, Hoffnung, Liebe

Anselm Kiefer

1984-1986

_______________________

In his element

A review of 'The Astonishment Tapes'

Rachel Blau Duplessis

jacket2The Astonishment Tapes: Talks on Poetry and Autobiography with Robin Blaser and Friends

Robin Blaser, ed. Miriam Nichols

Robin Blaser is in his element in these monologues in interview format — personable, pedagogic, and himself a “high-energy construct,” to not-quite-cite Charles Olson. By virtue of this book, the reader experiences Blaser as a unique force field of magnetic knowledge and charismatic charm. He is at home among the poets, themselves practitioners and friends, meeting in 1974 at someone’s house in Vancouver. The agenda is mixed: the taped sessions from which these talks are transcribed were apparently proposed by Warren Tallman to constitute or contribute to Blaser’s autobiographical memoir, and probably to dig into the complex nexus of a famous triad: Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, and Blaser. Their comradeship, quarrels, spites, and splits (among those involving other intimates) are one tale of the formation and impact of the “Berkeley” or “San Francisco Renaissance” in the New [North] American Poetry, a poetics and practice — with its accompanying lore — that energized these Canadian poets in distinctive ways.

As performer, talker, essayist, and poet, Blaser will not stay domesticated in literary history. The 1974 Vancouver tapes are therefore rangy, suggestive, allusive, and metamorphic. So the other part of the agenda for these meetings is both more buried and irruptive. Blaser is direct: “An autobiography is as much the intellectual loves as the personal loves.” As if he were running a high-level seminar in the humanities and poesis, Blaser immerses his audience in poetics and poetry from Dante to Shelley, Mallarmé to seriality, touching on such poets as Olson, Pound, and Levertov, but also encompassing Western poetic and philosophic traditions. Blaser wants, needs, and desires to talk broadly, taking the defining interests of Duncan, Spicer, and himself as exemplary of the problematic of Western civilization after “religion” loses its binding force: what can the human be ontologically and epistemologically in the post-humanist period? And what, therefore, are the tasks of poetry? Indeed, Blaser’s Dantean framework became quite clear to me in reading this book — not sure why this book particularly, but there it is. In fact, Blaser is one of the striking users of Dante among contemporary poets, but unlike John Kinsella’s or James Merrill’s, his Dante is somehow distributed into and saturated within “Image-Nation,” the serial poem pulsing at irregular intervals through his collected poems, The Holy Forest.

...(more)

_______________________

Anselm Kiefer

_______________________

The Primacy of the Object

Julius Greve reviews Martin Paul Eve's Pynchon and Philosophy: Wittgenstein, Foucault and Adorno

In his review of , Julius Greve situates this new book on Pynchon within the upheavals produced by speculative realism and contemporary discourses on materialism. In doing so, Greve reminds us of what was always already the case: the literary-philosophical relevance of Pynchon, which turns out to be all the more inescapable in contemporary political climates.

How to relate philosophical thought to literary practice? And, conversely, how to illuminate issues presented in narrative literature by having recourse to systems of philosophy? These are the two preeminent questions that Martin Paul Eve asks himself and answers impressively in his recent study Pynchon and Philosophy: Wittgenstein, Foucault and Adorno (2014). They are questions that have been posed often in American Studies and in Pynchon scholarship particularly, due to the notoriously difficult and multifaceted nature of Pynchon’s fiction. In a sense, the trajectory of Pynchon’s career as a novelist goes hand in hand, historically speaking, with the increasing frequency of those questions regarding the precise relationship between philosophy and literature, or theory and practice, being asked within literary studies as a whole and, above all, within the American context. Starting with highly complex and – at times – transnationally set novels like V. (1963), The Crying of Lot 49 (1966 ), or Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), Pynchon’s first major steps as a fiction writer fall into the period where the long reign of New Criticism within literary analysis faded and made room for French theory’s shaking, breaking, and re-assembling the foundations of what it was to read a text. Undoubtedly, this historical coincidence and Pynchon’s magisterially multiplicitous – if infamous and, at times, impenetrable – style of prose is one of the major reasons why his novels are often regarded as the blueprint of what is routinely termed American postmodern fiction.

Yet, it is precisely because Pynchon is so immersed, from the beginning of his career all the way to the most recent novel, Bleeding Edge (2013), in the philosophical discourses, scientific theories (above all the second law of thermodynamics, as evident in the eponymous short story, “Entropy” (1960)), and cultural-political contexts of his time and the many centuries that preceded it, that there is a certain resistance within his novels towards literary criticism’s establishment of the respective correlations or resonances with these contexts and discourses. ...(more)

_______________________

The Digital in the Humanities: An Interview with Franco Moretti

(....)

...I've never seen digital humanities as, so to speak, a total novelty as some of its practitioners do. For me it’s basically the form taken in the digital age by scientific, explanatory, empirical, rationalistic, call it what you want, approaches to the history of literature and culture.

(....)

Interdisciplinary work won't solve the problem. Interdisciplinary work is even harder than disciplinary work. It's even more chancy and random. You have to be lucky as hell because you move blindly. Now, are the digital humanities heading towards making the humanities as a whole, let's say literature in my case, relevant in terms of beautiful theories and high-order conceptualization? No. Not yet, at least. That's what I care about. I don't care if the humanities have bar graphs in every paper, like The Financial Times, which I think in a newspaper there should be, but not necessarily in literature. No, to make the humanities relevant you need something much bigger than the digital humanities. What the humanities need are large theories and bold concepts.

...(more)

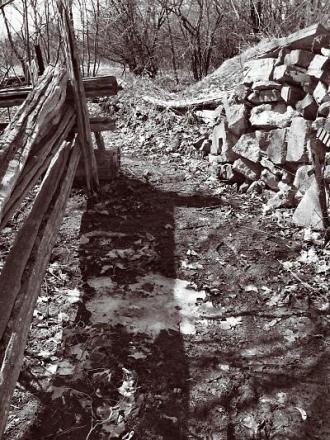

photo - mw

_______________________

On the Miniature

Kay Ryan

Threepenny Review, Spring 2016

“To be miniature is to be swallowed by a miniature whale.”

This is wisdom I gleaned from experience. And when I say gleaned I mean picked up off the ground after the commercial harvesters had come through. This is wisdom nobody much wanted; I surely didn’t. Of course, much wisdom is things we never wanted to know. (Itself an additional piece of wisdom, again demonstrating how discouraging wisdom is.)

But to return to the question of the miniature, we find imbedded in this prescient line the design flaw inherent in the impulse to miniaturize: all in the world you wind up doing is changing the scale of everything. If you manage to make yourself small (I was thinking about trying to have a very small life to escape the interest of, say, fate), you only excite a small whale to swallow you.

The stories of the miniature go down and down and down; small becomes the new large, over and over. In The Third Policeman, the great Flann O’Brien gets the last chest the policeman makes so infinitesimally small that it took him “three years to make and it took…another year to believe [he] had.” As with all processes, there is no end. The contemplation of the miniature is therefore destabilizing, dizzying, sickening. There isn’t any size that’s the “real size” after awhile. (O’Brien could have gone on.)

...(more)

via the page

_______________________

A Poem of Unrest

John Ashbery

Men duly understand the river of life,

misconstruing it, as it widens and its cities grow

dark and denser, always farther away.

****

And of course that remote denseness suits

us, as lambs and clover might have

if things had been built to order differently.

****

But since I don't understand myself, only segments

of myself that misunderstand each other, there's no

reason for you to want to, no way you could

****

even if we both wanted it. Do those towers even exist?

We must look at it that way, along those lines

so the thought can erect itself, like plywood battlements.

From "Can You Hear, Bird" by John Ashbery

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Notes Towards a Coming Backlash:

Mindfulne$$ as an opiate of the middle classes

Per Drougge

translated by Glenn Wallis and the author

Speculative Non-Buddhism

(....)

It is not that long ago since Western textbooks would describe Buddhism as a life-denying, pessimistic, or even nihilistic religion. While it is easy to dismiss such descriptions today, we should perhaps ask ourselves if the current popular image of Buddhism has not gone too far in the opposite direction. Even before the success of mindfulness, Buddhism was often presented as a kind of “happiness project,” symbolized by laughing monks rather than emaciated ascetics. This is a version of Buddhism which allows an affluent audience to enjoy its privileges while, at the same time, upholding a detached, cynical distance towards the vicissitudes of samsaric existence, which is why philosopher Slavoj Žižek (2001b) has described Western Buddhism as the “perfect ideological supplement” to capitalist dynamics. Hardly surprising, it is also this kind of Buddhism which has inspired today’s mindfulness.

Meditation, which in most Buddhist traditions was an activity engaged in by only a small elite of religious specialists and ascetics with the explicit purpose of cutting all ties with the world, is here presented as a method for improving our professional life and romantic relationships (not to mention golf swings!). (Robert H)Sharf reminds us that the orthodox, Theravada outlook can be described as rather dark: to be alive means that we are suffering; the only way out is liberation from sa?sara which demands that we abandon all hope of finding happiness in worldly existence. As a contrast to current, sanguine ideas of meditation, he goes on to quote a passage from Buddhaghosa’s classic Visuddhimagga with its descriptions of the fearful stages (so-called dukkha nana) advanced yogis traverse before attaining final liberation. Even though one should be careful not to take classical meditation manuals too literally (cf. Sharf 1995b), it is worth considering that the canonical literature often describe the Buddhist path as one filled with fear and loathing, and that the idea of Buddhist meditation as remedy for depression, chronic pain, substance abuse, personality disorders and whatnot, is an entirely new phenomenon.

Like many other critics of mindfulness, Sharf admits that it may have some therapeutic value, and he mentions the “substantial body of empirical (if contested) data, that suggest it does.” He adds, though, that many years’ contact with experienced meditators has made him skeptical; not only do they exhibit behaviors at odds with common notions of what constitutes mental health—even more important, perhaps, is that they likely “do not aspire to our model of mental health in the first place.” And this, Sharf concludes, is a real challenge when we want to understand the connection between Buddhist meditation and its desired outcome.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

e-flux journal #71

Editorial

The freeport method of art storage presents its critics with a problem. Is it something new? Or something old? What could be less surprising than an international aristocracy hiding treasures in a cave someplace? The CEO of the Geneva Freeport might have overcharged his Russian Oligarch, Dmitry Rybolovlev, by one billion dollars for thirty-five paintings, according to Sam Knight’s recent, riveting account. Rybolovlev had himself acquired a large slice of the collective ownership of the means of production in 1992, when he was twenty-nine, in the form of Uralkali, a mining company developed by the State Planning Committee of the USSR in 1926. He sold his stake for five billion dollars in 2010. These sums feel like numbers from a different era, when boys regularly played with liquid money made from melting down some residual kingdom.

It’s hard to know what to make of the transformation of so much Soviet capital into a Picasso or a Chagall. It feels like the end of a long sequence. It was said that Trotsky read Balzac in Central Committee meetings and that’s why people didn’t like him, and that it came back to haunt him, this antisocial love of high culture. And now all our masterpieces are locked in a box somewhere in the Alps while the world burns. But who among us has the courage to blame him?

Following Hito Steyerl, Stefan Heidenreich in “Freeportism as Style and Ideology” argues that although the freeport probably doesn’t amount to a new mode of production, it might be a new mode of representation, replacing the one that ruled from the end of the Bretton Woods era up until the Great Recession. Like other such modes, freeportism has a value-form, post-internet art, that is optimized for contemporary accumulation, and an ideology, speculative realism, that attempts to transform its novel configuration of forces and relations into a new metaphysics.

...(more)

mosaic

Afro Basaldella

b. March 4, 1912

_______________________

The Cloaca of Work and Friendship

Justin E. H. Smith

As Facebook increasingly becomes the site of work-related activity, alongside what's left in this degraded age of true amical interaction, I've come to think of it as a sort of cloaca, through which both the shit and the joyous stuff of life pass indiscriminately.

In an evolutionary sense the monotremes (the ‘one-holes’) are considered the most primitive of mammals, while those that have developed special organs for each function are held to be more advanced. We however have gone the other way. A generation ago one did not have to uphold one’s professional identity, one did not have to look busy, when shooting the breeze with friends late in the evening. Now, especially among academics, it is understood that we will carry over our career-minded uprightness, our eagerness to appear as good mentors, as positive role-models and eager organisers, into this same venue, practically the only venue that is left to many of us, in which we also pretend to express who we really are. But I am not a good mentor or role-model or organiser. I only do those things for a living. What I am, in reality, is a sceptical, hesitant, conflicted, confused human being, who nonetheless finds life worth living mostly because of the vast reserves of poetry, literature, art, and philosophy passed down to us from the ancestors. I am not my job, even if my job is the closest thing I could find in this degraded age, in this degraded world, to pure communion with the beautiful things that do not change. Or at least that is how I imagined the job would be, even if global economic pressures, craven administrators, and anti-intellectual politicians are doing everything they can to ensure that it not be that.

...(more)

_______________________

Afro Basaldella

_______________________

Bodies in Plural: Toward an Anarchafeminist Manifesto

Chiara Bottici

Does it still make sense to speak about feminism in a world where gender categories are constantly being reshuffled? What does it mean to be a woman? Can we say “woman” without falling into the charge of essentialism or, even worse, heteronormativity?

This lecture addresses such questions by proposing to combine an “anarchafeminist” research agenda with Spinoza’s ontology of the transindividual. The lecture was made possible by the generosity of the Danielle Dionne Guerin Memorial Fund in Women’s Studies at Muhlenberg College. The lecture served as the keynote address in the 2nd Annual “Thinking the Plural” Richard J. Bernstein Symposium, which focused on the theme of “Feminism and Pluralism.”

Nihilists with Good Imaginations

Lucas Ballestín

(....)

... myths are necessary to motivate political mobilization; yet we might wonder if there is some way to supplant old myths with new ones, old ways of knowing ourselves as political actors that are not so heavily ballasted with the weight of inherited authority. How can we conceive the possibility of deploying a myth well rooted enough to prove efficaciousness without reproducing the foundations of existing, polluted categories?

For Bottici, this is the task of the political imagination, that through which we reconstruct, redirect, and reinvent our conceptions of self. This is not an “abstract” invention; it is a re-working that is couched in the realities of social life. But the claim is there is something in us that is irreducible to our social life and identity, a creative core that is un-colonizable and — at least potentially — revolutionary. From this standpoint, we can conceive a radical re-framing of what we are and act accordingly. This imagination is not some flight of fancy, but a deeply subversive tool that can illuminate the concrete reality of oppression just as it imagines a world otherwise.

By making recourse to this way of imagining, we can take an important first step toward dismantling existing oppressions: bringing them into relief and recreating a new world within all pre-existing structures. For this reason, Bottici reaches for an odd neo-Spinozist metaphysics: transindividuality can fulfill the role that appears necessary for serious political mobilization while avoiding all the pernicious strictures of our inherited political myths. The political imagination can construct a new myth that can move us toward a new world, all the while basing itself not on reified and oppressive structures, but on subjects mutually implicated in a shared struggle to reshape what is.

...(more)

_______________________

Afro Basaldella

_______________________

A Translation of "Eine Zeugenaussage"

a 1963 Short Story by Thomas Bernhard

Translation by Douglas Robertson

A Witness’s Statement

I went from a first-class compartment into a second-class compartment and then back into a first-class compartment; like my father, I was constantly changing places; I was irritable; I am ill, I sought out a quite ordinary peaceful place in which I would be able to jot down my notes, those records that I told you about earlier, those short snatches of reminiscence; soon it will be winter; then it will no longer be possible for me to jot down these notes; the arduousness of my work as a clinician makes it impossible for me to write down even a single sentence, and so I sought out an auspicious place; for my purposes I need a place that I can obfuscate, obnubilate, as I see fit…but people have an aversion to darkness; for some inexplicable reason they dread darkness; even quite ordinary travelers dread it…all the while I was busy studying the various characters, the individualistic types and the mass types; I fairly found myself duty-bound to construct, to reconstruct, them day after day for my purposes; I step into human beings, into their vulgar, unprepossessing processes of decomposition; as one steps into cities, I step into human beings; I do not shrink back from this abjection; a colossal misunderstanding of all the sciences in the aggregate enables me to enter into human beings…until I suddenly stand aghast in the fantastic geometry of disagreements, in the queasiness of two millennia, where concepts like nightmares wantonly play tricks on the mind, until finally, all at once, triumphing over each and every acrobatic feint, I descry in my ruined brain the untruthfulness of my own truth…all this is of course very perplexing ......(more)

_______________________

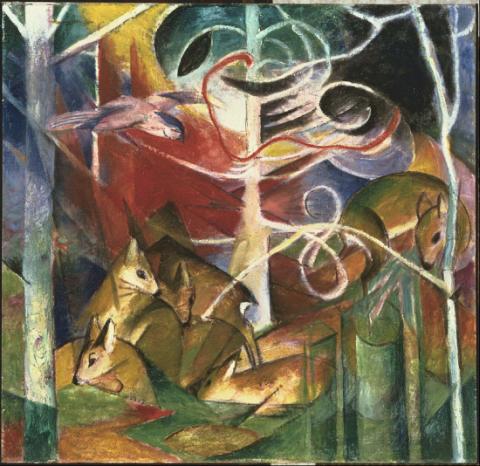

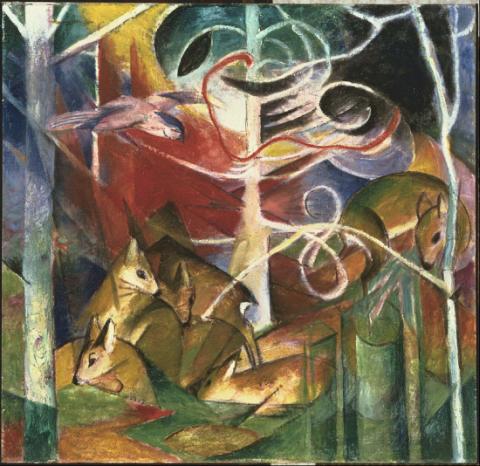

Franz Marc

d. March 4, 1916

_______________________

Two Poems

Richard Weaver

conjunctions

Missing Art as Dark Matter

No geography is older

than the wind declares,

the sea imagines or the earth

blindly acknowledges.

No pear grown in a bottle

rivals this riddle. An imagined death

is still a death. A grief postponed

will make a nest in the heart.

Mystery always manages mischief

(or so we are led to believe).

And so one day blue light will reveal

the harbored, unseen framed edges

and then streak across the gilded border

the event horizon that awakens

the prismatic eye.

Because it was stolen,

because it was burnt, or labeled

degenerate, because the wilderness

accepted it as one of its own,

because the mystery shines in relief

the image remains the thought unseen

the world erasing history.

...(more)

Ivon Hitchens

b. March 3, 1893

_______________________

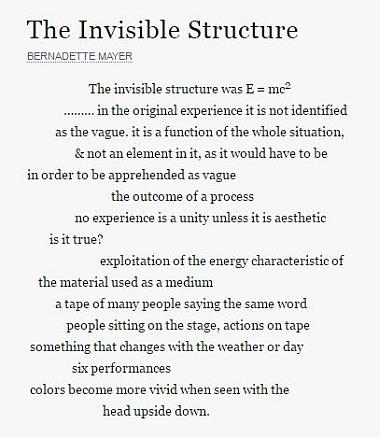

Thirteen poems by Bernadette Mayer

Edited by Michael RubySam Truitt

poems from Bernadette Mayer’s manuscript The Old Style Is Finding out Something about a Whole New Set of Possibilities, written between 1966 and 1970, along with a critical introduction to the work. This important early collection remained unpublished for forty-five years until its appearance in Eating the Colors of a Lineup of Words: The Early Books of Bernadette Mayer (Station Hill Press, 2015), also edited by Ruby and Truitt.

Bernadette Mayer at EPC and the Poety Foundation

_______________________

Study for Reaper with a Mushroom

John Craxton

(1922 - 2009)

_______________________

Agamben on the figure of “the assistant”:

from Profanations

presented at Ballerinas Dance With Machine Guns

(....)

But how can one recognize these helpers, these translators? If they hide among the faithful as foreigners, who will have the vision capable of distinguishing the visionaries?

An intermediate creature who exists between the wazir and Kafka’s assistants is the little hunchback that Benjamin evokes in his childhood memories. This "tenant of the distorted life” is not just the cipher of childish clumsiness, nor the trickster who steals the glass from someone who wants to drink and the prayer from someone who wants to pray. Rather, his appearance makes it so that whoever looks at him “can no longer pay attention” to himself or to the little man. The hunchback is, in fact, the representative of the forgotten; he presents himself in order to lay claim to the aspect of oblivion that resides in every thing. This share of oblivion has something to do with the end of time, just as carelessness is a precursor to redemption. Distortion, the hump, and clumsiness are the forms things take in oblivion. What we have always already forgotten is the Kingdom, we who live “as if we were not the Kingdom.” When the messiah comes, the distorted will be straightened, the obstacle will become easy, and the forgotten will be remembered of its own accord. For it is said, “for them and their kind, the incomplete and the inept, to them hope will be given."

The idea that the Kingdom is present in profane time in sinister and distorted forms, that the elements of the final state are hidden precisely in what today appears despicable and derisory, that shame, in sum, secretly has something to do with glory, is a profound messianic theme. ...(more)

_______________________

The Globalisation of Re-sentment: Failure, Denial and Violence in World Politics

Elisabetta Brighi

Let's kill him boldly, but not wrathfully;

Let's carve him as a dish fit for the gods,

Not hew him as a carcass fit for hounds:

And let our hearts, as subtle masters do,

Stir up their servants to an act of rage,

And after seem to chide 'em. This shall make

Our purpose necessary and not envious:

Which so appearing to the common eyes,

We shall be call'd purgers, not murderers.

W. Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, Act II, Scene I

It is commonplace for pop psychology today to invite their readers to embrace, rather than resist, failure. Invoking a supposedly timeless wisdom that stretches from Confucius to Sylvester Stallone, self-help websites such as ‘Psychology Today’ urge readers to cease looking at failure as one looks at an unappealing birthday present and start welcoming failure as a gift, disappointment as a growth opportunity, and defeat as a path leading to complete mastery of the resilient self. A good dose of denial, disavowal and effacement are arguably involved in the process. While the unresolved feelings or incongruent actions that may have precipitated failure are mostly left unscrutinised, the wider social, cultural and political context, conditions, and contradictions become conveniently elided or misrepresented. The focus turns obsessively to the self and its expected ability to reset and reconfigure towards personal success, achievement and happiness. Rather than a moment of appearance and truth, failure is thus denied and rendered barren.

(....)

In this paper I investigate how the globalisation of failure intersects the globalisation of resentment and the diffusion of individualised forms of political violence. I shall do so through the lenses of contemporary terrorism, and in particular the ‘fifth wave’, ‘micro-structural’ terrorism as evidenced in the 2015 double terror attacks in Paris. The first part of the paper charts the rise of global resentment in its interaction with changing forms of violence and against the background of the multiplication of failure and cascading grievances. The second and third parts examine the place of resentment in the affective and moral economy of the global age by unpacking this concept along two axes. The first axis maps the distinction between resentment and ressentiment and seeks to rescue the former from the relative hegemony of the latter. By contrasting the readings of Adam Smith, Joseph Butler, Friedrich Nietzsche, Max Scheler and their contemporary epigones, it fleshes out the distinction between resentment geared towards justice and that driven by envy. The second axis explores the gap between resentment and ressentiment from the point of view of the entanglements of identity and difference. By drawing on the writings of William Connolly, Wendy Brown and René Girard, it evaluates different configurations of the relation between self and other and assesses the strengths of the claim concerning an ever expanding diffusion of ressentiment in late modern times. The paper closes with a reading of the Paris terror attacks of 7 January and 13 November that seeks to disentangle the different forms of resentment mobilised in the acts. By raising the issue of the moral value of resentment, the paper ultimately seeks to address the question of how to cope with failure while holding on to emancipatory, counter-hegemonic and self-affirming political practices. ...(more)

_______________________

Ivon Hitchens

_______________________

An Integral

Ray Davis on Gypsy by Carter Scholz

Pseudopodium

(....)

By his own account, he was old-schooled. Like me, Scholz "grew up and was educated during the Cold War, when math and science education were priorities." There was a certain fogginess about utility then, before our rulers successfully separated education-for-maximal-exploitation from the chaff of pure-science truth and high-culture beauty — I think they call it "rationalization"? Those were the irrationally unexuberant years when, as mentioned on the fourth page of Gypsy, someone like Louis Zukofsky could find a stable day-job at Brooklyn Polytechnic.

Passing references to poets are themselves a bit old-school in fiction: Shakespeare or Eliot for titles; Dickinson or Blake for epigraphs; Villon or Rimbaud for stock characters. Louis Zukofsky is an unusual choice, though.

Zukofsky's poetry wasn't widely available until the late 1960s. Back in 1978, the year of his death and the year his long "poem of a life," "A", was published, niche readers like myself and (I suppose) Scholz still thought it likely Zukofksy's brand of difficulty would follow the Modernist course of things and become, if not widely known, then about as widely known as twentieth-century poetry gets. It never happened. His niche readership now is probably no larger than his niche readership in 1978. Rather than poetic heroism triumphant, Zukofsky exemplifies th'expense of spirit in a waste of craft, sloughed off by posterity as insufficiently instantaneously rewarding.

At any rate, Louis Zukofsky's name does not appear after the fourth page of Gypsy.

...(more)

Walter Elmer Schofield

1867 - 1944

_______________________

Chorus Of Furies

Basil Bunting

b. March 1, 1900

Guarda mi disse, le feroce Erine

Let us come upon him first as if in a dream,

anonymous triple presence,

memory made substance and tally of heart’s rot:

then in the waking Now be demonstrable, seem

sole aspect of being’s essence,

coffin to the living touch, self’s Iscariot.

Then he will loath the year’s recurrent long caress

without hope of divorce,

envying idiocy’s apathy or the stress

of definite remorse.

He will lapse into a halflife lest the taut force

of the mind’s eagerness

recall those fiends or new apparitions endorse

his excessive distress.

He will shrink, his manhood leave him, slough selfaware

the last skin of the flayed: despair.

He will nurse his terror carefully, uncertain

even of death’s solace,

impotent to outpace

dispersion of the soul, disruption of the brain.

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

From “Photograms”

Ahmed Bouanani

Translated from French by Emma Ramadan

(....)

I will be the old earth of Babylon

with its gods its satyrs and its legions

I will spread in your beds my pallid cyclones

and far very far in your shivering regions

I will paint my death on a canvas of autumn

It’s an old kingdom of wreckage

that can no longer laugh or dream

Does it remember the flower turned savage

and the poets no longer able to see?

Its minarets like a scar

its ageless soldiers dead on their feet

and our cries are only murmurs

since our god reigns on his knees

With sky and too much silence words like a fire of seed hence we choose for ourselves a different adolescence

It’s a primordial kingdom of gradual death Draped in days we sleep there full of the empty Full indeed?

(....)

The house of memory has left with the current

dead memory will dress me in cinders

tamed nights sad like a convent

nurture the empty smile of salamanders

My ancestors extinguished in a coat of fire

have grown tired of opening the doors to our dreams

and our dreams locked up in distant

cemeteries of a too-brief eternity

tear down to the blood their chests

we will have to burn the mountains of incense

to erase the sky at the root of our rage

and our lips sealed with mirages of a former age

will spit as they please on the bygone days

of a thousand louvered shutters with a wounded gaze

...(more)

Crossing Boundaries: Ten Moroccan Writers

I went to Morocco for a year in 2014 to translate a book of poetry by Ahmed Bouanani. I was originally introduced to Bouanani’s work in the summer of 2013 by Omar Berrada, the director of the library at the international arts residency Dar al-Ma’mûn, located just outside of Marrakech, where I would volunteer for the year. From my first day in Morocco, I tried to keep my eyes and ears open for more Moroccan writers whose work resonated with me, for writing that was doing new things with language or interesting things politically. I ended up reading and meeting many exciting authors, and I wanted to get other translators involved in bringing some of their words into English. Words Without Borders allowed me to do just that.

French is the language, and France is the country, with the highest percentage of books translated into English every year. However, very few francophone writers from countries other than France—such as Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Lebanon, Haiti, Madagascar, etc.—are finding their way to English-language readers. In 2015, 15% of books in translation were from the French, and just 8.8% of those 113 books were from outside of Europe and Canada. During my year in Marrakech, I started looking into which Moroccan writers had already been translated. I assumed the renowned Moroccan writers had all managed to find their way into English at some point. I would soon learn just how untrue this was. In the entire history of Moroccan writing, written in any language—be it French, Arabic, or any of the local dialects—I managed to find only roughly thirty Moroccan writers with full-length works translated into English. Of course, it’s possible that I missed some authors and there may be books that are out of print or not easily accessible. But how will English speakers who don’t have grants or other ways of spending meaningful time in Morocco be able to access what Moroccan writers have had to say if none of their stories are readily available in English?

...(more)

Crossing Boundaries: Morocco's Many VoicesWords without Borders March 2016

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Nihilism and the Deconstruction of Time: Notes Toward Infrapolitics. [pdf]

Jaime Rodríguez Matos

Transmodernity 5.1 (2015). 36-51

How do we stand with respect to nihilism? Perhaps Oliver Marchart’s book Post-

Foundational Political Thought (2007) is not a bad place to start when considering this question,

even if in a preliminary fashion. His book is, among other things, an attempt to separate

Leftist-Heideggerian theorists (including Jean-Luc Nancy, Alain Badiou, Claude Lefort and

Ernesto Laclau) from the charge of nihilism that is usually leveled at approaches that posit

the absence of a final or foundational ground, whether it is in terms of politics or

philosophy. He cites Laclau’s words to this effect:

there are no necessarily pessimistic or nihilistic conclusions to be drawn from

the dissolution of the foundationalist horizon . . . As Laclau underlines, the

“abandonment of the myth of foundations does not lead to nihilism . . .”

since the “dissolution of the myth of foundations . . . further radicalizes the

emancipatory possibilities offered by the Enlightenment and Marxism.”

What is odd about this particular defense against the accusation of nihilism is that the theory of post-foundationalism is predicated first and foremost on what Heidegger called the ontological difference. And in Heidegger’s own thought, we find that taking the ontological difference seriously would make it impossible to treat the problem of nihilism as a mere pitfall that can be avoided or as an obstacle that can be simply surpassed—for nihilism must instead be thought in its essence and thought must first learn how to gather itself in the nothing that it is (see “On the Question of Being” Heidegger 291-322). Marchart, on the contrary, states that nihilism, which for him is another name for anti-foundationalism, is the assumption of the absence of foundations, even if one thinks of foundations as a contingent and partial. And according to him, this “would result in complete meaninglessness”. Marchart’s project is geared toward avoiding such an abyss.

My aim here is not to delve into the intricacies of the theory of post-foundationalism as Marchart’s elaborates it, but his insistence on sidestepping the problem of nihilism does serve to illustrate one of the recurrent symptoms of the incursion into politics of the question of being. (....)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

My Newfoundland

The sensations of landing on the island long ago haunted a writer’s final memories

Paul West

1930 - 2015

My first teaching job carried me straight from the RAF and England to St. John’s, Newfoundland, when I was but 27. I still find my first impressions to be the overpowering ones: of fog or knocking sea. The town seemed nothing like the Oldest City in North America. It clutched and clung to the rocks like snails—perhaps the mist might have dissolved it or the sea gnawed it down. From the air it looked precarious; from the sea, as I sneaked in through the Narrows, as sheer a pair of nautical jaws as one could wish for a landfall, the effect was altogether different: still the shantytown with much rust and much gesticulating new paint, but also the settled center of a kind of commerce, silver oil tanks glittering in whatever sun there was. The harbor had the slack gape of a transatlantic Cardiff or Merseyside in miniature.

I was fortunate in my arrival because the rain was pouring. From the first I could catch a sight of the genius of the island, this place that has icebergs in June. It all looked Finnish, perfunctory, and sparse. Miles and miles of timber hemmed in smallish areas of shaggy rock. Settlements seemed few, roads fewer. After a swift ride through streets of sad houses, all wooden and flimsy, I was dropped off at Circular Road, where lodgings had been arranged for me. I did not know it, but I was on the threshold of a revelation—a symbol was to be vouchsafed for me. ...(more)

|