|

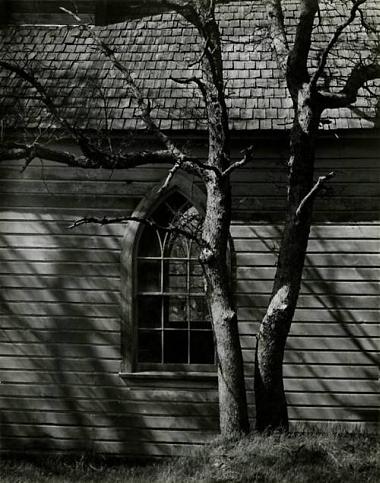

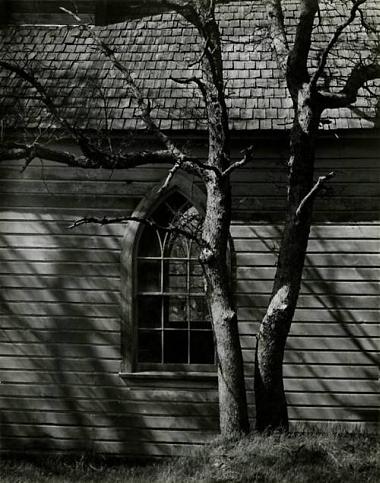

photo - mw

_______________________

Armchair woodsmen

I have books on chopping wood, baking bread and butchery. But what do I really know if I never set foot in the forest?

Michael Gibb

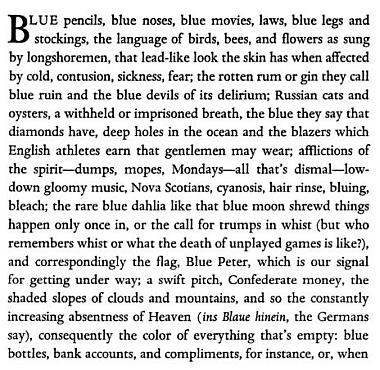

(....)Most of what I know about firewood comes from a Norwegian book entitled Hel Ved (2011), which roughly translates as ‘solid wood’. It was written by the novelist Lars Mytting and contains detailed discussions of every aspect of sourcing, chopping, drying, storing and burning wood. There are tables in the back listing the drying rates and percentage of ash you can expect from different species of tree. There are references to research conducted by something called the Norwegian Institute of Wood Technology. Mytting is serious about his firewood.

(....)

There are some individuals for whom such a reference library makes undoubted practical sense. If you live in an extremely rural community, some mastery of this knowledge is likely essential both for comfort and survival. I, on the other hand, live in central London. The two pigeons nesting in our chimney suggest that it is a long time since the disabled fireplace in our converted Victorian terrace last saw any action, and the local council would put an end to any aspirations I might have for a wood-burning oven in what can only with considerable generosity be called our back garden. There is, in short, perhaps some absurdity in my taste for survivalist literature. And yet I am not alone. I belong to a growing community of woodsmen, butchers and craftsmen of various kinds who ply their trade from the armchair....(more)

Aeon Magazine

_______________________

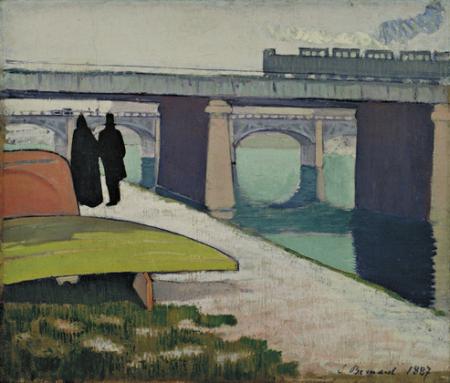

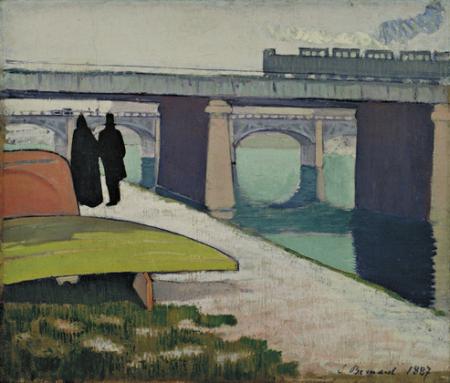

Iron Bridges at Asničres

Émile Bernard

1868–1941

_______________________

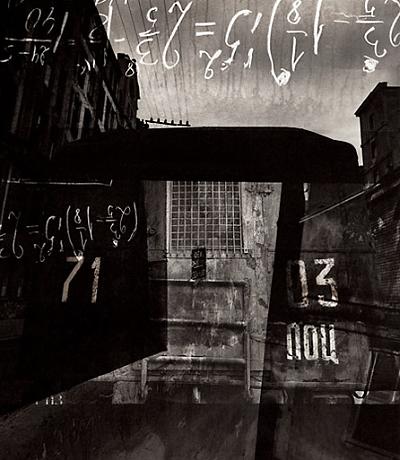

Stan Allen interview

by Nader Tehrani

Bomb

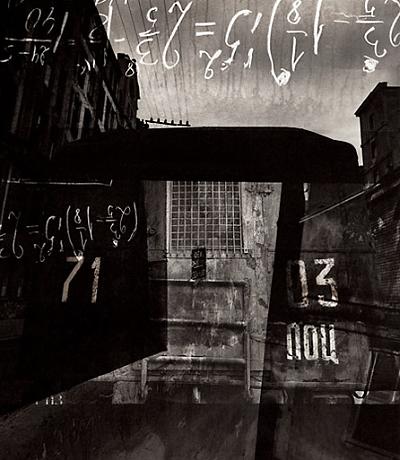

Stan Allen has been an active and vocal force in architecture over the past 25 years. As the former dean of the School of Architecture at Princeton, the principal of Stan Allen Architect, and the author of numerous books and articles (among them the essay “From Object to Field: Field Conditions in Architecture and Urbanism,” to which we refer repeatedly in this conversation), his impact has been felt from the realms of practice to the academic world. In the “Field Conditions” text, he articulates new ways in which “difference” can be accommodated in compositional strategies that do not resort to figural, typological, or iconic variations and he unearths a series of aggregative strategies that demonstrate the wide range of spatial, formal, and material possibilities immanent in the systemic logics of the field itself. Protean in many ways, Allen’s mission has been to define some of the irreducible aspects of the architectural discipline on the one hand, while on the other he has used his experience with the arts—painting, film, sculpture, and beyond—to expand the intellectual terrain on which architects walk....(more)

BOMB 123/Spring 2013

_______________________

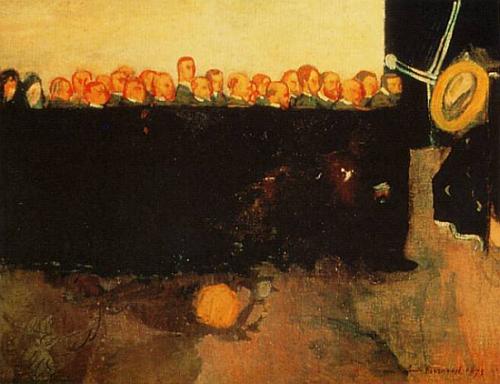

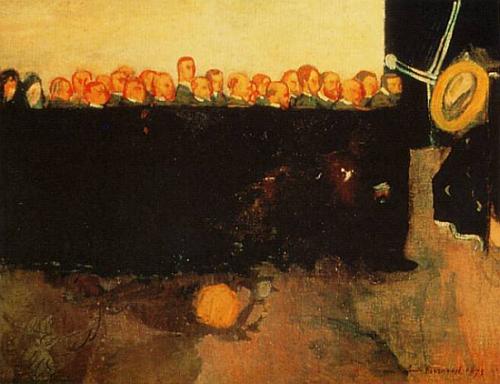

Vincent Van Gogh's Funeral

Émile Bernard

1893

_______________________

Social Control in Mental Health

Jeremy

An und für sich

(....)

... Deviance from accepted norms of behavior is a sign of sickness that must be addressed through increasingly intensive and onerous treatments. As my colleague frequently critiques on this blog, health is understood as having a job, a nice haircut, a spouse, and a capacity to sit quietly on the subway. To a distressing degree, illness is essentially understood as anything non-normative. Screaming at pigeons in the park? I can construct a rationale to understand that as a symptom of illness. But an eight-year-old boy staring out a window in school has a disease? Surely there have been people whose lives have been destroyed by ADHD. However, slowly but surely, idiosyncratic elements of the individual are re-labeled as beyond the pale and thus necessitating treatment and psychological intervention.

(....)

As a mental health provider, I strenuously resist this implied position of equating norms with health. I think it is imperative that we collectively maintain the position that we do not, in fact, know what is best for other people in most situations, and that we do violence to their freedom and integrity as individuals, and therefore ourselves, by imposing the will of the third/big other. Towards this end, I am frequently reminded of something once said by the prominent psychoanalyst Otto Will: “As I see it, my task is to help this person look at, and evaluate, his life and his prospects. I don’t know how he should live, but I may be able to help in discovering this for himself. I am not an expert at living.”

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

The Force That Drives the Flower

Annie Dillard

b. April 30, 1945

The Atlantic Monthly | November 1973

(....)

I don't know what it is about fecundity that so appalls. I suppose it is the teeming evidence that birth and growth, which we value, are ubiquitous and blind, that life itself is so astonishingly cheap, that nature is as careless as it is bountiful, and that with extravagance goes a crushing waste that will one day include our own cheap lives. Every glistening egg is a memento mori.

Now, in late June in the Blue Ridge, things are popping outside. Creatures extrude or vent eggs; larvae fatten, split their shells, and eat them; spores dissolve or explode; root hairs multiply, corn puffs on the stalk, grass yields seed, shoots erupt from the earth turgid and sheathed; wet muskrats, rabbits, and squirrels slide into the sunlight, mewling and blind; and everywhere watery cells divide and swell, swell and divide. I can like it and call it birth and regeneration, or I can play the devil's advocate and call it rank fecundity—and say that it's hell that's a-poppin'.

This is what I plan to do. Partly as a result of my terrible dream, I have been thinking that the landscape of the intricate world that I have cherished is inaccurate and lopsided. It's too optimistic. For the notion of the infinite variety of detail and the multiplicity of forms is a pleasing one; in complexity are the fringes of beauty, and in variety are generosity and exuberance. But all this leaves something vital out of the picture. It is not one monarch butterfly I see, but a thousand. I myself am not one, but legion. And we are all going to die.

In this repetition of individuals is a mindless stutter, an imbecilic fixedness that must be taken into account. The driving force behind all this fecundity is a terrible pressure I also must consider, the pressure of birth and growth, the pressure that squeezes out the egg and bursts the pupa, that hungers and lusts and drives the creature relentlessly toward its own death. Fecundity, then, is what I have been thinking about, fecundity and the pressure of growth. Fecundity is an ugly word for an ugly subject. It is ugly, at least, in the eggy animal world. I don't think it is for plants.

...(more)

_______________________

The page, the page, that eternal blankness, the blankness of eternity which you cover slowly, affirming time's scrawl as a right and your daring as necessity; the page, which you cover woodenly, ruining it, but asserting your freedom and power to act, acknowledging that you ruin everything you touch but touching it nevertheless, because acting is better than being here in mere opacity; the page, which you cover slowly with the crabbed thread of your gut; the page in the purity of its possibilities; the page of your death, against which you pit such flawed excellences as you can muster with all your life's strength: that page will teach you to write.

—

Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

Boy Destroying Piano

Phillip Jones Griffiths

Iconic Photos

Famous, Infamous and Iconic Photos

Philip Jones Griffiths

1936 - 2008

_______________________

Fear as a Constant Companion

Within the National (In)Security State

Phil Rockstroh

Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom.

Søren Kierkegaard

Life, as lived, moment to moment, in the corporate/consumer state, involves moving between states of tedium, stress, and swoons of mass media and consumer distraction. Therein, one spends a large portion of one’s economically beleaguered life attempting to make ends meet and not go mad from the pressure and the boredom. Where does a nebulous concept such as freedom even enter the picture, except to be a harbinger of an unfocused sense of unease, that all too many look to authority to banish?

Finding a balance between anxiety and freedom is not something that comes easy to us.

In a society beset with a lack of purpose and meaning, patriotism, empty self-promotion and jingoism are mistaken for strength and character, when, in fact, they are anathema. Weakness compensates by affecting a cretinous swagger. Those who lack a centering core crave power. Beneath it all, quakes one who fears risking intimacy…is terror stricken by the vulnerability attendant to risking love. Those who fear the uncertainty inherent to intimacy and freedom perceive a world fraught with ubiquitous danger.

They terrorize themselves; therefore, they see terrorists everywhere.

(....)

Under the tedium, angst, and ennui of corporate state rule, people get high on the adrenal rush induced by the mass media feedback loop. Also, there is the illusion of breaking the spell of alienation and becoming part of a larger order.

It is troubling that the adrenaline-tweaked, news-as-mass-spectacle audience/primed-for-authoritarianism citizenry of the U.S. seems indifferent to, or oblivious of, the following: The test of a free society comes when that society is put under duress e.g., not allowing the power-besotted, authoritarian freaks in charge to use the acts of a few violent, lost souls as a means to curtail freedom and consolidate unaccountable power for themselves.

...(more)

_______________________

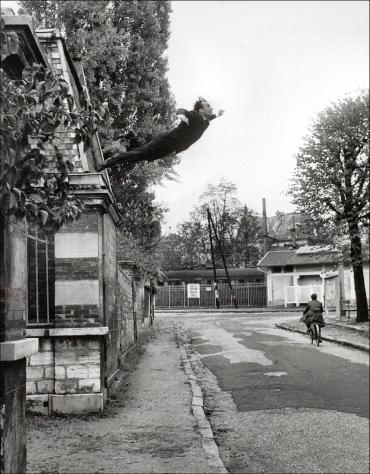

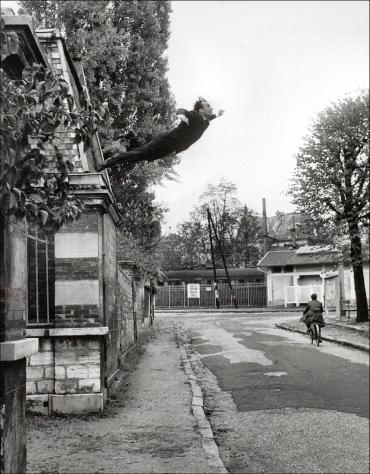

"Leap into the void"

1960

Yves Klein

b. April 28, 1928

_______________________

Spring is like a perhaps hand

(which comes carefully

out of Nowhere)arranging

a window,into which people look(while

people stare

arranging and changing placing

carefully there a strange

thing and a known thing here)and

changing everything carefully

spring is like a perhaps

Hand in a window

(carefully to

and fro moving New and

Old things,while

people stare carefully

moving a perhaps

fraction of flower here placing

an inch of air there)and

without breaking anything.

- e.e. cummings

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Dirt

John Latta

(....)

And as the plant grows older it realizes it will never be a tree,

Will probably always be haunted by a bee

And cultivates stupid impressions

So as not to become part of the dirt. The dirt

Is mounting like a sea. And we say goodbye

Shaking hands in front of the crashing of the waves

That give our words lonesomeness, and make these flabby hands seem ours- . . .

—

John Ashbery, out of "'How Much Longer Will I Be Able to Inhabit

the Divine Sepulcher . . .'" (The Tennis Court Oath, 1962)

(....)

The vetch has turned purple. But where is the bride?

It is easy to say to those bidden-But where,

Where, butcher, seducer, bloodman, reveller,

Where is sun and music and highest heaven's lust,

For which more than any words cries deeplier?

This mangled, smutted semi-world hacked out

Of dirt. . . It is not possible for the moon

To blot this with its dove-winged blendings.

—

Wallace Stevens, out of "Ghosts as Cocoons"

...(more)

_______________________

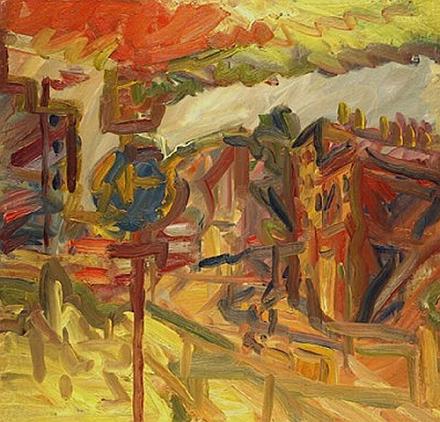

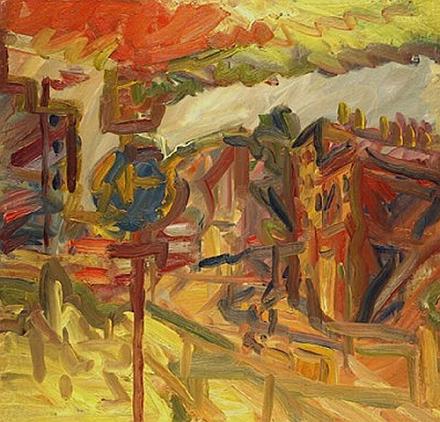

London building site

Frank Auerbach

b. April 29, 1931

_______________________

Eternity No More: Walter Benjamin on the Eternal Return

Tyrus Miller

in Given World and Time: Temporalities in Context, edited by Tyrus Miller

"Men of the nineteenth century, the hour of our apparitions is fixed forever, and always brings us back to the very same ones."

— Blanqui, 1872

On January 6, 1938, Walter Benjamin wrote to Max Horkheimer from San Remo to report on a remarkable development in his thinking about his Baudelaire studies and about the larger framework of the Passagenwerk, Benjamin's decade-long historical research about 19th-century Paris, a project that he described as an "Urgeschichte der Moderne" (an archaic history of modernity). The occasion of this development was his encounter with a largely forgotten text by the famous insurrectionist Auguste Blanqui, entitled L'éternité par les astres (Eternity According to the Stars). This short book comprised a set of cosmological speculations written in prison by the old revolutionary near the end of his life, and coupled arguments from the popular science of Blanqui's day with a remarkable vision of infinite repetitions of the same in an indefinite series of parallel worlds. Here is Benjamin's report to Horkheimer:

In the last weeks I have made a strange find that will decisively influence the work: I came upon the text, Blanqui's last, which he wrote in his final prison,in the fortress of Taureau. It is a cosmological speculation. . . .and is, as far as I can tell, till now as good as unknown. . . . Admittedly,at first glance the text is tasteless and banal. Whereas what constitutes its main portion are the clumsy meditations of an autodidact, these prepare for a speculation about the universe that could be provided by no one lesser than this revolutionary. If Hell is a theological object, one could call these speculations infernal. The world view that Blanqui sketches here, while taking its data from the mechanistic natural sciences of his day, is in fact infernal--but is at the same time, in the shape of something natural, the complement of the social order that Blanqui must have recognized in the evening of his life to be the victor. What is astonishing is that this sketch is completely without irony. It represents an unconditional surrender,but at the same time the most terrible lament against a society that projects this images of the cosmos against the sky. The piece has as its theme, the eternal recurrence, the most remarkable relation to Nietzsche; and a more hidden and deeper one to Baudelaire, with whom in a few of its magnificent points it resonates almost word-for-word.

Although this was only two years from the close of Benjamin's own defeated life, this seemingly minor discovery of a truly marginal text of Blanqui crystallized a whole new set of motives in the Passagenwerk studies and seemed to offer Benjamin a conceptual hinge for the juncture of modernity and myth he intuited in the culture of 19th-century Paris. In fact, in the final, 1939 version of his exposé of the Passagenwerk he granted the last word--in his text and about the nineteenth century--to the messengers of the eternal recurrence. In his final paragraph, following a quote from Blanqui's L'eternité par les astres, Benjamin concludes:

The century was incapable of responding to the new technological possibilities with a new social order. That is why the last word was left to the errant negotiators between old and new who are at the heart of these phantasmagorias. The world dominated by its phantasmagorias--this, to make use of Baudelaire's term, is "modernity." Blanqui's vision has the entire universe entering the modernity of which Baudelaire's seven old men are the heralds. In the end, Blanqui views novelty as an attribute of all that is under sentence of damnation. Likewise in Ciel et enfer, a vaudeville piece that slightly predates the book: in this piece the torments of hell figure as the latest novelty of all time, as "pains eternal and always new." The people of the nineteenth century, whom Blanqui addresses as if they were apparitions, are natives of this region.

...(more)

X Poetics

For Sound, Crossing, Mobility, Exchange, For Doubt & Uncertainty, Bird Cries, Duende, Multiplicity, Former, Excess, Xcountry

_______________________

The Awning

Frank Auerbach III 2008, 2008

_______________________

Mud Is Mud: Ongoing Notes Toward An Essay On The Art Of Fiction

Sina Queyras

lemon hound

Clarity is not accessibility.

Accessibility is not simplistic.

Brevity isn’t minimalism.

Oblique is often too much distance.

Less is not always more.

Excess is not experimental.

...(more)

photo - mw

_______________________

Doina Ioanid

Translated from the Romanian by Florin Bican

Translator's note: Doina Ioanid or the epiphany of melancholy

exquisite corpse

(....)

Too tired, too myopic. Even my name, a squashed clam, slowly sinks through my skin deep within me, past soft tissues, past organs pulsating like terrified suns, deep down to where none of the things on the outside can force their way in any more.

(....)

It may well be I’m no different than the seagulls along the embankment--a whitewashed crow, just like Mika-Lé used to say. Hey, you can’t possibly think they are seagulls for real... What on earth should them seagulls be doing in the middle of Bucharest?, Mika-Lé taunted me through her razor-sharp lips. I could hear, all the same, their ravenous cries and could see their lot prowling, along with needy fishermen, for the same paltry prey soiled past redemption with infested waters. I could see them rummaging through the garbage along with the homeless. And in my turn I started asking myself what on earth was I doing on the embankment, what was I doing in that raving mad city? The earthworms after the rain were wriggling their way to my feet. Slowly but surely. And all I could do was just stand there, all on my own, like some potted plant, roots gone all mouldy.

...(more)

.....................................................

(....)

Her prose poems are just as many epiphanies, trimming poetic perception – and expression – of all excess baggage. Yet stark they are not. They are, rather, streamlined vehicles (deep-sea vessels spring to mind), and very sophisticated ones at that, meant to take the reader beyond usually unquestioned borders, into an abyss both familiar and scary. While exploring herself, Doina Ioanid seems to trigger off in the reader an irrepressible urge to replicate the process with his/her own personal data. Never was intimacy more discreet – or more universal, for that matter. And that’s what makes Doina Ioanid’s poetry so substantial: the constant yet delicate delving into a multilayered, multifaceted reality in a redemptive attempt to make sense of things without robbing them of their aura.

—

Florin Bican

_______________________

Small Boats

Shoreline of Mississippi River

1910 ca.

The Cassville Photographs of Frank W. Feiker

Wisconsin Historical Images

_______________________

Wittgenstein's Dream

Peter Porter

I had taken my boat out on the fiord,

I get so dreadfully morose at five,

I went in and put Nature on my hatstand

And considered the Sinking of the Eveninglands

And laughed at what translation may contrive

And worked at mathematics and was bored.

There was fire above, the sun in its descent,

There were letters there whose words seemed scarcely cooked,

There was speech and decency and utter terror,

In twice four hundred pages just one error

In everything I ever wrote—I looked

In meaning for whatever wasn't meant.

Some amateur was killing Schubert dead,

Some of the pains the English force on me,

Somewhere with cow-bells Austria exists,

But then I saw the gods pin up their lists

But was not on them—we live stupidly

But are redeemed by what cannot be said.

...(more)

Ludwig Wittgenstein

b. April 26, 1889

rowing from Skjolden to his house

_______________________

Sentenced to Depth

an interview with William H. Gass

interviewed by John Madera

(....)

JM: So, how about the title, Middle C? Besides the musical reference, what else does it suggest to you? And in the excerpt “The Music Lesson” there’s a whole conversation between Joseph and his teacher Mr. Hirk about middle C on the piano.

WHG: It’s a grade in class. It’s mediocrity. The stuff I put about middle C in the mouth of the teacher, so-called, was gleaned, of course, from standard things said about it in the history, and it stands, really, for the whole traditional association of emotions, feelings, attitudes, etc., with various keys and various chords, and so forth, which grew out of, flourished finally, in the nineteenth century.

It is all about being nobody. It’s all about being however foundational, or thought to be foundational. The character is busy escaping the contamination of other human beings as his father apparently was doing. As [Thomas] Hobbes suggested, when you have an absolute sovereign, you have no rights, and you can be snuffed out; and the only way to avoid that is to be unobservable, to be so quiet, to be so out of it. This character tries to imitate that while nevertheless trying to make do with the situation he finds himself in, being hauled out of Austria ahead of the Nazis. He has to make a living and so forth. His living depends on his life being made up. He’s a fraud. So he sends a fraudulent self to work in the world. It can get as soiled as it likes, but another self will be back behind, not touched by . . . This is an idiotic view in a way, but my main theme is questioning what is the ordinary citizen’s responsibility for what goes on in the world. I don’t have an answer to that question exactly. [Laughter]

(....)

Rain Taxi Online Edition: Spring 2013

_______________________

The Motive for Metaphor

Denis Donoghue

(....)

... Stevens was not a trained philosopher, but his desires were philosophic. Mostly, he hoped-against-hope that Idealism would turn out to be true—that consciousness would be found to account for the whole of one’s experience.

But he felt misgiving about planning to see anything “at the exactest point at which it is itself.” That way, Naturalism lies— fixity, and specious certitude. For the time being, in “The Motive for Metaphor,” he can only cry out against the dominant X. He was not alone in that protest. Ortega y Gasset maintained that the chief motive of art since Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and Debussy has been to reject the conventional privilege ascribed to external things, objects, and faces, and to cultivate entirely formal, aesthetic inventions. I assume he had modern abstract or non-figurative paintings in view and knew that these had their own authority, however occult. That is why Stevens was pleased to find Charles Mauron saying, in his Aesthetics and Psychology (1935), that “the artist transforms us, willy-nilly, into epicures.” He was also pleased to find, in Simone Weil’s La Pesanteur et la grāce, a chapter on “decreation.” Stevens commented:

She says that decreation is making [something] pass from the created to the uncreated, but that destruction is making [something] pass from the created to nothingness. Modern reality is a reality of decreation . . .

I think he was pleased, too, to find Picasso saying that a picture is a horde of destructions, if only because it allowed Stevens to say that “a poem is a horde of destructions.” Metaphor, according to Ortega, has been the main device in an artist’s rejection of external things. “Metaphor alone furnishes an escape.” Its efficacy verges on magic. Between real things, it “lets emerge imaginary reefs, a crop of floating islands.” Metaphor “disposes of an object by having it masquerade as something else.” We ascribe to Nietzsche but not only to him the desire to be elsewhere, which is a variant of the desire to be different. In certain moods the horror of a word is the meaning it defends against all comers; so metaphor is the device by which one undermines that defense. In Stevens’ “Someone Puts a Pineapple Together,” the someone contemplates “A wholly artificial nature, in which / The profusion of metaphor has been increased.” If you put a pineapple together and see metaphors becoming more profuse, you release yourself from psychological determinations, you become a performative gesture and are happy to find yourself in that state. But then a scruple may assert itself:

He must say nothing of the fruit that is

Not true, nor think it, less. He must defy

The metaphor that murders metaphor.

Presumably a bad metaphor murders a good one: bad in the sense of telling lies, ignoring the truths that can’t honorably be ignored....(more)

_______________________

The Motive for Metaphor

Wallace Stevens

You like it under the trees in autumn,

Because everything is half dead.

The wind moves like a cripple among the leaves

And repeats words without meaning.

In the same way, you were happy in spring,

With the half colors of quarter-things,

The slightly brighter sky, the melting clouds,

The single bird, the obscure moon--

The obscure moon lighting an obscure world

Of things that would never be quite expressed,

Where you yourself were not quite yourself,

And did not want nor have to be,

Desiring the exhilarations of changes:

The motive for metaphor, shrinking from

The weight of primary noon,

The A B C of being,

The ruddy temper, the hammer

Of red and blue, the hard sound--

Steel against intimation--the sharp flash,

The vital, arrogant, fatal, dominant X.

.....................................................

Northrup Frye on The Motive for Metaphor

The Educated Imagination

_______________________

Frank Feiker

_______________________

Texts In Sebald’s The Rings Of Saturn

The Public Domain Review

(....)

Among the many lives of the past encountered is a myriad array of literary figures. Collected together in this post are the major texts of which, and through which, Sebald speaks – accompanied by extracts in which the texts are mentioned. The list begins and ends with the great polymath Thomas Browne, an appropriate framing as the work of this 17th century Norfolk native has a presence which permeates the whole book. Indeed, in the way he effortlessly moves through different histories and voices, it is perhaps in Browne’s concept of the ‘Eternal Present’ which Sebald can be seen to operate, in this mysterious community of the living and the dead.

...(more)

_______________________

"Because none of us are as cruel as all of us":

Anonymity and Subjectivation

Liam Mitchell

ctheory

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

There are no lone inventors

Matt Novak

(....)

The truth is that history, like innovation, is messy. What starts as an idea for a product, or a service, or an institution is dependent upon thousands of forces seen and unseen, recognized and unrecognized, historical and contemporary. In reality, the Internet was invented by thousands of people. To buy into the other version of history means you buy into the “myth of the lone inventor”—an idea that creates simple, even entertaining narratives, but which does a great disservice to the thousands of people who have invented our modern world.

Nowhere is the perpetuation of this myth greater than in the work of the late Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla—the man, we are often told, who invented everything from radar to radio and domestic electricity supplies. The fanaticism surrounding Nikola Tesla has reached fever pitch in recent months, driven by new films, endless blog posts and a high-profile effort to fund a museum dedicated to the legendary inventor. But the byproduct of this effort to reposition Tesla in the scientific canon has been the creation of many more myths about the man—myths that actually harm our understanding of history and the history of innovation.

...(more)

_______________________

Cost Per Impression: Anti-history of The Persuaders

Erik Stinson

(....)

Advertising doesn’t have a history, because it doesn’t want one. Advertising, the gaping, whoring mouth of the capitalist beast, would prefer to exist totally in the present, without past or future. Like the ideal customer. Pleasure button. Flashing tits. Chemical burrito under Kino Flo studio lights. The director screams at the food stylist one last time, then jogs to the talent trailer for nap.

What advertising wants is a handjob and another ten million minds to feed with plastic desire. Why read? Why think?

What I want is a little context, a little background. I’d like to put together my own working understanding. It probably won’t happen....(more)

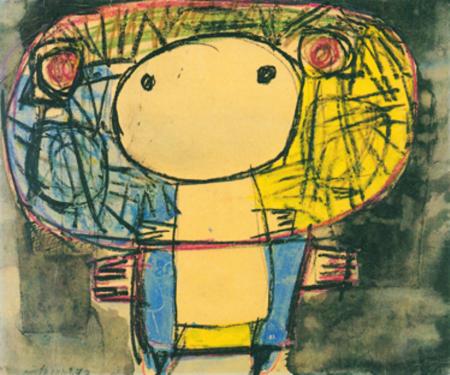

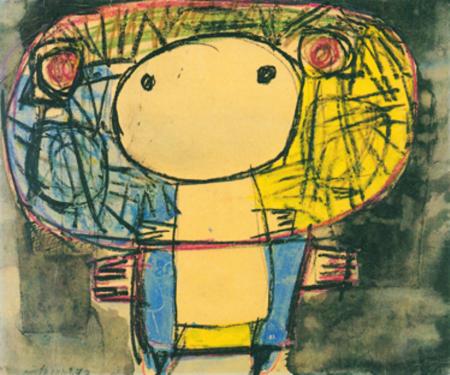

Kindje met bloemen

1947

Karel Appel

b. April 25, 1921

_______________________

The Castaway Is Washed Ashore

Peter Porter

(16 February 1929 - 23 April 2010)

(....)

Mixed metaphors sail on apace,

The ship goes down and then

A second time the splintered face,

A Castaway again –

A pair of ragged claws might row

Me safely from the undertow.

Quotations like a flag unfurled

In cruel convenience

Showed my position in the world,

The past my present tense.

As mushrooms, rose the childish faces,

A succulence of desert places.

...(more)

Peter Porter at the Australian Poetry Library, the Poetry Foundation and Poetry International_______________________

Salines, Petit Méchin

Aprés Strand

Bertrand Carričre

The gallery is pleased to announce our sixth exhibition of work by Bertrand Carričre. "Aprčs Strand" revisits a part of photographic history through the work of American photographer Paul Strand and his connection to Carričre's own territory, Québec.

During the summer of 2010, Carričre travelled to the Gaspé Peninsula, following the route that Strand took in 1929 and 1936. From his two trips to Gaspésie, Strand produced a number of pictures, but few are known to the general public.

Carričre's photographs adopt Strand's vision of photography and his approach to landscape. While deliberately avoiding imitation, he allowed himself to absorb Strand's lessons, observing time, memory and landscape. Carričre is fascinated with stories that are bound to the land, traces of which persist to this day. His attention was drawn to the social landscape and vernacular architecture, documenting modest houses, barns, fishermen's cabins and wayside crosses. He photographed some of the inhabitants he met, trying to be faithful to a humanistic approach, out of respect for the people who have shaped the land and have kept these remote communities alive, while struggling with an unforgiving climate and difficult socioeconomic conditions.

The Gaspésie that Strand documented no longer exists, but Carričre's work was deeply inspired by the places Strand photographed.

— bulger gallery

Plage, Percé

Aprés Strand

Bertrand Carričre

via Joerg Colberg

_______________________

Archetypes of Dissent

Mapping the cultural contraflow of revolt.

Andy Merrifield

(....)

What we have here is an expressive politics that “appears” in a different guise, in its true guise of invisibility, simultaneously present and absent in “public” space.

In fact, the whole idea of opacity and dissimulation, of clandestinity and anonymity is part and parcel of an archetype of contemporary militant politics, part of its tactic and identity, part of the armory of what dissent is and should be. Perhaps it’s possible to draw up a list of “archetypes of dissent,” of progressive, not reactionary dissenters. Archetypes that symbolize, as Jung would have had it, an innate disposition to make trouble, to protest, to revolt against the structures of modern power; to let power know that ordinary people are still alive and kicking, and that staying alive necessitates every once in a while kicking out at power, at its structures of law and order.

...(more)

_______________________

Vragende kinderen

Questioning Children

Karel Appel

1949

_______________________

Of Mini-Ships and Archives

Daphne Marlatt

lemon hound

... from a broader perspective, language itself is a living archive. More specifically, the history of a language is an archive of the cultural changes and linguistic borrowings of its speakers through centuries of usage. As a poet, I recognize this fact from hours at my desk behind a closed door (the gift of not just solitary but uninterrupted time) where I trace glimmers of half-erased, half-perceived connections between words and their historic trade routes through time. Nouns, little ships freighted with meaning, fossilized verbs that once sailed their way through seas of speech, language to language. My tracing of these routes will find their way (or not) into sentences composing a larger verbal structure that may (or may not) eventually find its way into print. Often these mini-ships, hand jottings on draft pages of print or nearly illegible scribbles on scraps of paper, get lost in file folders in drawers or boxes, eventually to land, years later, on a library shelf under bright lights in what is termed an archive. Docked, documented. Archivally (re)constructed.

Reconstruction: putting together scattered fragments, putting together what once occurred or was experienced as a gestalt, a whole, but is now available only in shards, odd notes on variously sourced, undated pages or bits of paper. To some degree, the drive behind collecting a writer’s archive is rather like what drives archaeology. It is similar to resurrecting the dead, if such a thing were possible. But then there is also what is lost in the living, layers and layers of memory that are now simply recalled by outline, by the repeated telling of an event that the body’s complex sensoria once experienced fully in all the emotional and mental reverberations of a moment’s impact. Perhaps this desire is the drive behind oral history and its effort to uncover and make public what people have experienced as personal. It is the memories of individual lives that together make up the particular history of a community—another kind of archive—recorded and made public as the unofficial history of the legislated-upon, rather than the official history of the legislators. These memories, often considered too personal to be of public value, when collected and published compose alternative or alternate views of official history, views that deepen our understanding of the impact of past events. So I discovered in 1972, when I first began working on a team collecting the Japanese Canadian oral history of Steveston, which at that point was largely untold outside of the community.

...(more)

from Basements and Attics, Closets and Cyberspace: Explorations in Canadian Women’s Archives (edited by Linda M. Morra and Jessica Schagerl) Wilfrid Laurier University Press Introduction: No Archive is Neutral

_______________________

from Unusual Woods

Gene Tanta

(....)

(turn) in the fast darkness of ancient forests,

shadows cross our dreaming faces (turn)

in the movies, an oak tree is always more there

after it’s gone (turn)

this way, a saw emphasizes one thing (turn)

formalwear, night fog rolling in

dressing the silver-blown accessories

(turn) in the morning,

when the rain goes to work,

the cemetery trees shade the cemetery dead

and spiders (turn) play the harps of corners

when the wind sighs, weathercocks turn

to look for a reason (turn)

...(more)

Almost Island

Unusual Woods

Gene Tanta BlazeVOX

Gene Tanta

poet, artist, teacher

_______________________

Clouds and People

Karel Appel

1984

_______________________

Sleeping with the Alphabet

Peter Porter

You glorious twenty-six, not equal

In purport, short straws of words,

Come with me in the night-time squall,

My hurricane of verbs.

My chiefest pegs to hang fear on —

Don’t think it’s only sights

Which dreams call up — Wordsong

Lingers in the tucks and sweats.

Sounds of pre-performance, cries

Subsumed in nothingness,

Hoping to syllabicize

Themselves as messages?

The A of Anger, E of Death,

An I who might not be myself

And O the deadly wind that bloweth

Unto U, my vowel of Truth

Jug on table

1915

Liubov Popova

April 24, 1889 – May 25, 1924

_______________________

The Mythical Liberal Order

Naazneen Barma, Ely Ratner, Steven Weber

(....)

Where exactly is the liberal world order that so many Western observers talk about? Today we have an international political landscape that is neither orderly nor liberal.

(....)

The liberal order can’t be under siege in any meaningful way (or prepped to integrate rising powers) because it never attained the breadth or depth required to elicit that kind of agenda. The liberal order is today still largely an aspiration, not a description of how states actually behave or how global governance actually works. The rise of a configuration of states that six years ago we called a “World Without the West” is not so much challenging a prevailing order as it is exposing the inherent frailty of the existing framework.

This might sound like bad news for American foreign policy and even worse news for the pursuit of global liberalism, but it doesn’t have to be so. Advancing a normative liberal agenda in the twenty-first century is possible but will require a new approach. Once strategists acknowledge that the liberal order is more or less a myth, they can let go of the anxious notion that some countries are attacking or challenging it, and the United States can be liberated from the burden of a supposed obligation to defend it. We can instead focus on the necessary task of building a liberal order from the ground up....(more)

_______________________

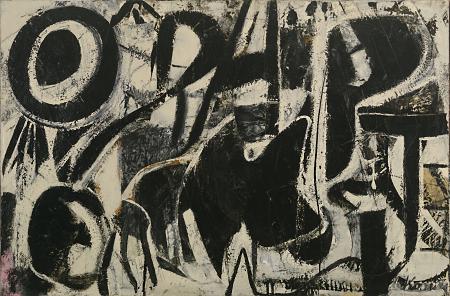

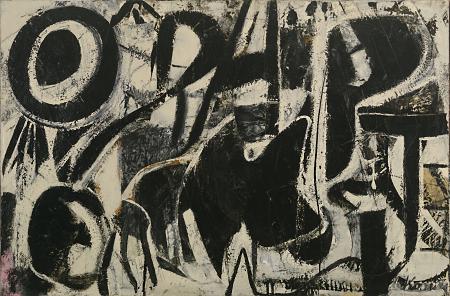

Orestes

Willem de Kooning

1947

_______________________

Real Faces of the Minimum Wage

Richard Eskow

Corporate interests and their elected representatives have created a world of illusion in order to resist paying a decent wage to working Americans. They’d have us believe that minimum-wage workers are teens from ’50s TV sitcoms working down at the local malt shoppe.

It’s a retro-fantasy where corporate stinginess creates minority jobs, working parents can’t possibly be impoverished, and nobody gets hurt except kids who drive dad’s convertible and top up their allowances with a minimum-wage job slinging burgers.

But then, you probably need to resort to fantasy arguments when you’re arguing against a minimum-wage increase supported by nearly three-quarters of the voting public. That’s also why it’s important to demand that Congress allow an up-or-down vote on the Fair Minimum Wage Act, which would raise it to $10.10 and then index it to inflation.

Here’s the truth: Most minimum-wage workers are adults, the majority of them are women, and many are parents who are trying to raise their children on poverty wages....(more)

_______________________

Defining the precariat

A class in the making

Guy Standing

Class has not disappeared. Instead, a more fragmented global class structure has emerged alongside a more flexible open labour market. This prompts Guy Standing to forge a new vocabulary capable of describing class relations in the global market system of the twenty-first century.

_______________________

Women Singing II

1966

Willem de Kooning

(April 24, 1904 – March 19, 1997)

_______________________

Essays in response

Nude Literary Review

Issue I: February 15, 2012

Modernism, Again

Peter Carne

Many of the responses to Lars Iyer's ‘Manifesto' that have appeared, mostly online, in the weeks since its publication have concentrated on how the ‘death of literature' is nothing new, that this call has been made on many past occasions and its passing will continue to be announced in the future. This is all true, but what I think has been missing from the discussions is a focus on the positive side of Iyer's argument: the second half of the piece – that proposes, and offers examples of, the types of fiction that one can ‘write at the wake' – seems to have been neglected in favour of the comment-generating provocativeness of the first.

(....)

Few people are, I imagine, shrinking from the works of Bolańo and Bernhard in horror. Yet, they do seem to be highlighting something that many critics and readers want to avoid a discussion of: literature’s end. However, this is only an end like all the other ends. I perceive the plea for more modernism in Iyer’s piece to be present in his calls for writers to be practicing their craft as though ‘at a wake’, recommending that they use an ‘unliterary plainness’ that ‘knows the game is up’, including the ‘gloomy, farcical life’, and writing about ‘this world … the world of dead dreams.’ Through the hyperbole one only expects to be found in manifestos (thus giving Iyer the means to make use of such sweeping and provocative sentences), the reader is witness to the appeal for writers – if they just can’t give up the game entirely – to embrace the end and build a style around that finality, using the recommendations listed above. But, as Iyer points out in his paean to Bernhard, the style of writing that he expounds is one that originates from within the very rejection of the literary (things we may associate with ‘masterpieces’ and being part of what ‘great’ literature does): a great literary work today would therefore have to be unliterary – if you could excuse the contradiction – because it would represent, with honesty, the artistic deadlock we’re in. ‘Of course, the irony of Bernhard is that while his narrators fail again and again even to begin, Bernhard himself has found a form and a way to speak.’ It is on the back of this example that Iyer can contend that, ‘only at the very edge of the abyss can we remember what is untouchable.’ For me, the product of Iyer’s demands would be work that, following Josipovici, is modernist – even if we avoid describing it as that – through and through.

(....)

By contending that Iyer’s manifesto calls for more modernism I don’t just have Josipovici in mind. In fact, we can look to philosophy and critical theory for what I believe to be the most important insights into the ‘inward turn’ – and the other factors that could be thought of as the starting points for modernism – mentioned above. In the work of the American academic Eric L. Santner we find an analysis that – following on from the groundwork done by philosophers like Giorgio Agamben, Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin and Roberto Esposito – seeks to investigate the ‘biopolitical pressures generated by the transition from royal to popular sovereignty’, opining that this will be the only way ‘one will get hold of what distinguishes this chapter of cultural history’ (modernism); a period in which attempts are made to represent and come to terms with the transfer of sovereignty from the ‘flesh of the sovereign power and the symbols of that very power, onto the people’, who, ‘at least in principle, become the bearers of sovereignty’.

This can be linked to Iyer’s calls (along with my reading of them), and the works of fiction that he champions, through a consideration of the insecurity that leads to the writing of the end, the void, and the space that has appeared after everything has been done over and over again. How does one possibly write now?...(more)

_______________________

The Tube Train

c. 1934

Cyril Power

1872 - 1951

_______________________

The Ruins of the Future:

An Interview with Stephen Collis

lemon hound

Andrew Zuliani: ... What does it mean that now, after establishing yourself as a writer of “finger-pointing” poems that deal, however indirectly, with the urgent and contemporary, you have shifted the direction of this projection, and the target of its view? Why switch tracks to discuss the Spanish Civil War, the architecture of Antoni Gaudi, the poetry of Lorca, things that are culturally, geographically, and temporally divorced from the problems of the here-and-now? And, as a Gaudi-like buttress to this question, how does this relate to the shift from poetry to prose?

SC: Well this is interesting—because I often worry that my work might seem too ensnared in the past! But of course I am indeed driven by “present concerns,” and I do think that the future is what it’s all really about, as it were—every moment, we are getting there—the future arrives, and we are fashioning its conditions. And what we do to and within ecological contexts, largely through economic activities, is a big part of present concerns about future possibilities. Another way of putting this: capitalism is killing the planet, and we are seeing this with increasingly clarity—even scientists are starting to say it in these terms. But the future remains what we’re struggling over: what will it look like? Who will have access to it? Will it even be viable? What can we do to ensure it is viable?

I’ve always gone back into the past in order to find my way, hopefully, to a better future. There’s something of Orwell’s “who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past” to this, though I’m not so much interested in “control.” Ross Wolfe, writing about utopian architecture, refers to the “ruins of the future” which lie strewn about in the past—the idea that “the gateway to the future lies in the past,” and that the ruins of past ideas about the future are there for reconsideration. This is especially important when you are living, as we currently have been, through an era built upon the exhausted notion that “there is no alternative” to capitalism—an era marked by a significant lack of ideas about alternatives (“it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”). But there’s a substantial history of thinking, imagining and building alternatives that we can and I think need to revisit as we try to find our way out of the mess we’ve wandered, or, better, been goaded and coerced into. This is the creative project I’ve taken on in various books—to make some small foray into that past, in order to beat paths towards other possible tomorrows....(more)

_______________________

Triple Canopy Issue 18: Active Rot

_______________________

Escalator

Cyril Power

c. 1929

_______________________

beckett the nietzschean hedonist

Richard Marshall.

3am

(....)

Amidst the plethora of readings that shuffle the postmodern pack is Foucault. Foucault is an enduring hinge thinker in this sort of discussion, connecting the commonly asserted trope associating the Nietzschean death of God with the Barthean/Derridean postmodernist death of the author. The move from postmodern to existentialist readings of Beckett are virulent, where the desire for meaning in a context of nihilism and absurdism become the common ground for Beckettian philosophical musings. Martin Esslin’s seminal book ‘The Theatre of the Absurd’ captures this approach. Simon Crichley’s idea of meaninglessness being asserted again and again as a moral test is just a late, reheated moment in this tradition which bemusingly adds an ascetic morality test into the mix that really has no place anywhere near Nietzsche or Beckett.

...(more)

_______________________

Why Philosophy?

Peter Hacker

Philosophy as Conceptual Border Patrol

Jay Jeffers

_______________________

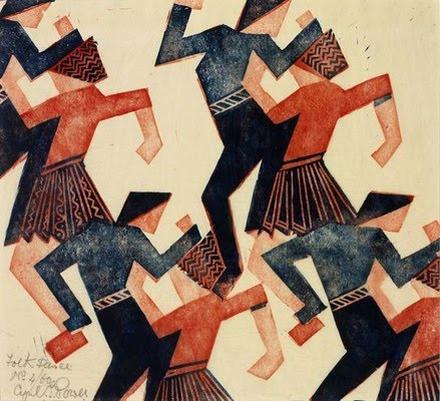

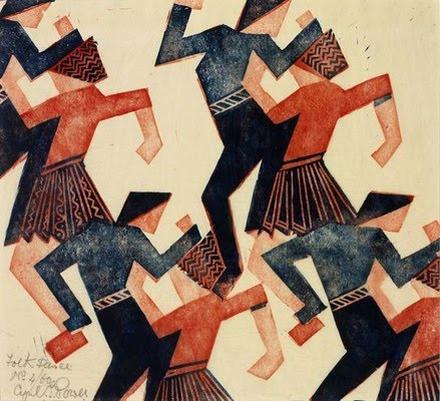

Folk Dance

(1928)

Cyril Power

The Morning after the Deluge

c. 1843

Joseph Turner

_______________________

Each day, our porous skin opens less and less to fresh air, sunlight, the touch of others, the smell of pine, rain, compost, and manure . . . and instead we find ourselves hunched over machines in the standard posture of reverence, bowing our heads to the humming and warm computer-pets that rest on our laps or in our palms.

Panting for Breath on a Virtual Shore

We are no longer homo sapiens: we're cyborgs.

Stefanie Krasnow adbusters

(....)

Our common understanding of cyborgs are hollywood clichés: rogue robots with human skin pulled taut over sleek metal wiring, and ON/OFF buttons tucked away in thigh or knee crevasses. But we don't have to wait until we embed chips beneath our skin, nor till we get Google Goggles as contact lens glued to our eyes, to earn our status as cyborgian. As Donna Haraway famously suggests, we are entirely cyborgs just as we appear now – with smart-phones tucked snugly in our pockets for every minute of every waking hour, held as close as possible to our skin in a hard-to-access area, much like a sacred amulet was once worn around one's neck in a burlap pouch.

In her Cyborg Manifesto, Haraway collapses the boundaries between human/animal, and human/machine, suggesting that there is as much artifice as there is "nature" in human nature. Our cyborgian condition was not begot by some sinister mutation, rather, we are as vitally and ineradicably entwined with machines as we are with the bacteria in our intestines. As Marshall McLuhan said: "we create machines in our own image and they, in turn, recreate us in theirs."

...(more)

_______________________

Two Poems

Matthew Sweeney

The Strong Man

The strong man ran away from the circus

because the lion wouldn’t love him.

He wandered into a forest, and began

uprooting trees. A badger stared at him.

An owl woke up. The man ignored both.

He weaved, howling, through the trees

at top speed, sending squirrels scattering,

till he came to a small, circular lake which

he dived into and swam to the centre.

...(more)

_______________________

He Who Gets Slapped

1924

video

He Who Gets Slapped: A Play in Four Acts

Leonid Andreyev

.....................................................

He Who Gets It

Joseph Jon Lanthie

interpolates responses to the Victor Sjöström film He Who Gets Slapped and the Charles Mingus/Jean Shepherd composition "The Clown".

(....)

- You have an irrational fear of exaggeratedly loose clothing, of obsequiousness, of performing before audiences, and of having your blood drawn with a hypothermic needle.

– Isn’t the gaze of an audience a needle of sorts—a tool with which non-fungible essence is extracted? Mightn’t the robes of an ordinary man fit perfectly, if not snugly, while those of the veteran clown sag comically from his shoulders? And can we not imagine the garments of this buffoon careerist clinging respectfully to his younger, fuller self? Is it perhaps not the clothes that change but the man—having exposed himself to crowds that ravenously feed upon his spectacular corpus? Is not their applause manipulative, a form of praise for which the performer can only pay with an ineffable piece of himself that he mayn’t replenish?

- You have an irrational fear of condescension, and are prone to presuming you are being condescended to.

– Don’t we all deign to speak to one another? Isn’t conversation simply another performance, one that is mutually enervating, the goal of which is to suck more from your company than he or she or they might suck from yourself? Is not the dormant conversationalist, while pausing to hear out his partner for the moment, less receiving than absorbing—draining, in a sense, his others?

- You have an irrational fear of having your blood drawn with a hypothermic needle, and of that which is not hypothetical.

...(more)

_______________________

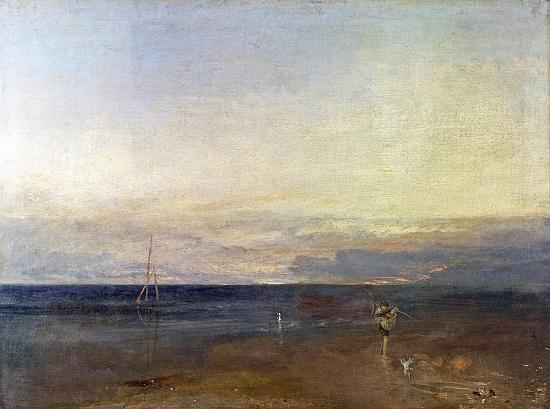

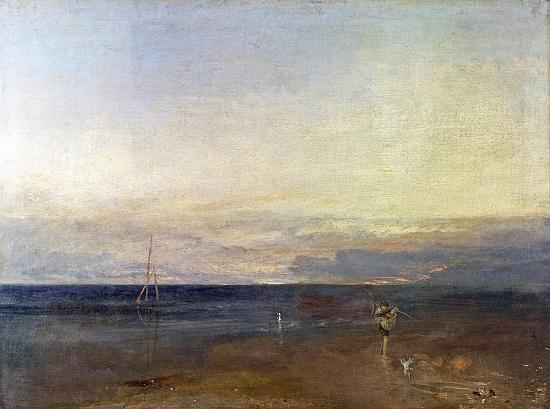

The Evening Star

Joseph Turner

(ca. 1830)

_______________________

Fellow Travelers

Bhaskar Sunkara

jacobin

(....)

The choice facing us isn’t between the blind worship of our particular pantheon of dead white men or Daily Kos-style ecumenicism. After all, the problem with the Left isn’t that it’s too austere and serious; it’s that it doesn’t take itself seriously enough to make the changes necessary for political practice. We can be rigorous and ideological — without being afraid of being heard outside our own circles. Mass exposure wouldn’t spell the end of a vibrant socialist critique.

But to get to the root of the problem will take an organizational revolution, not just a cultural one. We’re weird, because we’re not accountable to any mass constituency, not because we didn’t watch enough cable growing up.

Okay, maybe that too.

But it’s impossible to deny that institutionally the socialist left is in disarray, fragmented into a million different groupings, many of them with essentially the same politics. It’s an environment that breeds the narcissism of small differences. In a powerless movement, the stakes aren’t high enough to make people work together and the structures aren’t in place to facilitate substantive debate.

The prospect for left regroupment was one of my main motivations for founding Jacobin. Yet the watchwords of this project have seldom appeared in our pages. It’s finally time to make a call for joint action on the Left with an eye towards the unification of the many socialist organizations with similar political orientations into one larger body.

...(more)

No Short-Cuts: Interview with the JacobinIDIOM .....................................................

Dead White Reds

Matt Karp

jacobin “The tradition of all the dead generations,” Marx wrote a 150 years ago, “weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living.” Today, with our politics trapped in capitalism’s endless fugue state, the nightmare that troubled Marx may seem to contemporary left-wingers like a pleasant dream of days gone by.

At least the dead generations took Marx seriously. At least they had a powerful labor movement and center-left parties that believed in the welfare state. And at least Ralph Miliband, the dead leftist whose son is the living leader of Britain’s Labour Party, would never have answered a question about capitalism with a grudging obeisance to the creative power of BlackBerry.

It’s easy to get nostalgic.

A longer glance back into the past should cure us of this sentimentalism....(more)

_______________________

Sunset

c.1820-30

Joseph Turner

b. April 23, 1775

_______________________

Harmony Korine’s Disneyland dystopia Spring Breakers

eight critical essays at The New Inquiry

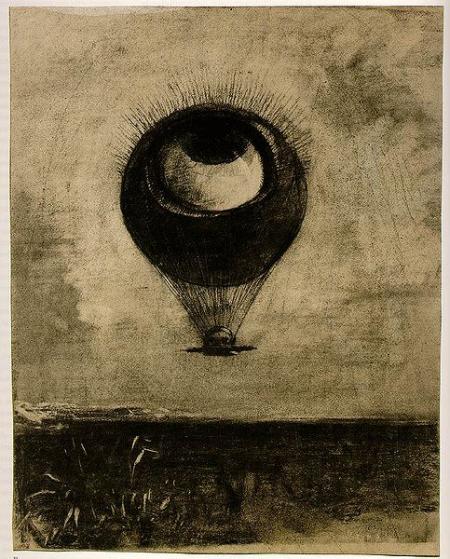

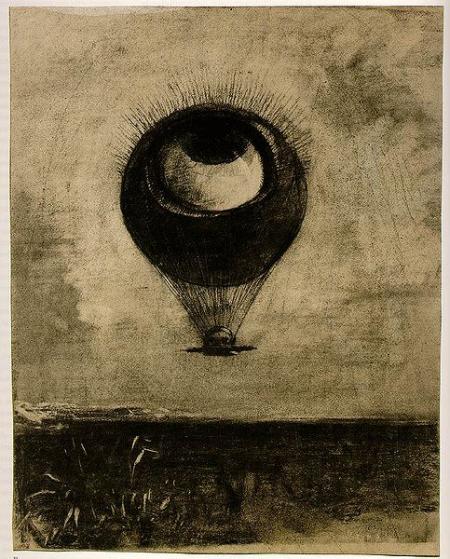

Eye-Balloon

1898

Odilon Redon

(April 20, 1840 – July 6, 1916)

_______________________

First Monday

Volume 18, Number 3 - 4 March 2013

Understanding social media monopolies

Silence, delirium, lies?

Caroline Bassett

Abstract

One way to undermine social media monopolies is to refuse to contribute to the communicational economy they are based upon: don’t generate exploitable signals, stay quiet — and ask how this might be developed as a common response. Given the naturalized assumption that ‘more communication’ will automatically produce ‘more freedom’, suggestions, like this one, that are based on doing less of it might provoke hostility. However, in the case of the social media industries, communication is cultivated not in the interests of freedom, but in the interests of growth; social media wants to capture more of you through your transactions. Moreover, through this process communications are not made ‘more free’ but tend rather to become less open — certainly in the sense that they are commoditized. With this in mind, this paper asks if a media politics might be generated based on the potentials of silence, on speaking in tongues — and on relying on the resources of metaphorical language rather than on learning to speak or write in ways more amenable to code.

Society doesn't exist

Jodi Dean

Abstract

This paper considers three versions of the claim that society doesn’t existence in order to investigate the problem of the idea of the social in social media. It identifies a convergence between the claims that society doesn’t exist and the social media we have. Yet it notes a disjunction between the media we have and the arguments of net critics and activists who say the problem is centralization and that what we need is individual control. Against this position, the paper argues for the relation between dispersion and centralization and the political potential manifest in centralization insofar as it makes apparent the social relations between people at the core of production.

Facebook.com text: Industrialising personal data production

Korinna Patelis

Abstract

This article examines Facebook.com as a cultural text. It casts a critical eye on the stories told by the Facebook monopoly interphase, focusing on how these intergrate commerce with communications. It struggles with the text’s key abstractions arguing that Facebook industrialises personalised data production by demanding the constant production on customised communcation objects.

_______________________

Can’t say it’s not spring

Katri Tapola

illustrations by Virpi Talvitie

Translated by Lola Rogers

from Mahdottomuuksien rajoissa. Matkakirja ('In the realm of impossibility. A travel book'

books from Finland

Off-kilter self-image

There are those among us who are over-exposed, under-exposed, unfocussed, or a bit  smudged, and then there are those with a self-image that’s out of kilter. The possessor of an off-kilter self-image is usually the victim of long-term exposure to binders, label-makers, and hole-punchers. Their off-kilterness is due to the evasive action that the person has constantly been taking for fear of becoming bound, labelled, and punched through with holes. A life that is out of kilter in the self-image is blurry: it’s hard to find the right door or sit down to coffee with gusto because you feel that a) someone’s going to pull the chair out from under you, or b) you yourself are going to miss the chair and pratfall to the floor. You may completely bypass happiness in the fog. When a passer by looks you in the eye and smiles, you may think they’re aiming right past you. There’s a simple solution to this problem: take a new picture. A self-image that stays put is best made using a long exposure time. The easiest way to do this is to get a cardboard box from your local grocery – anything will do, a pineapple box, whatever – and build your own pinhole camera, or camera obscura. This technique is sure to work. Just seat the off-kilter person in a chair and aim the pinhole camera at them. With long exposure time, the spine of the out-of-kilter person will seem to straighten of its own accord, since you can’t flinch or slouch. The image inside the camera will look upside down, and that is precisely the point. The person portrayed on the paper will glow with light and become translucent – the bones, the spreading wings. You will see yourself for the first time. There I am, you’ll laugh, born from the light! Then you’ll open the right door, meet someone’s gaze and return it, like a child or some other equally wondrous thing. smudged, and then there are those with a self-image that’s out of kilter. The possessor of an off-kilter self-image is usually the victim of long-term exposure to binders, label-makers, and hole-punchers. Their off-kilterness is due to the evasive action that the person has constantly been taking for fear of becoming bound, labelled, and punched through with holes. A life that is out of kilter in the self-image is blurry: it’s hard to find the right door or sit down to coffee with gusto because you feel that a) someone’s going to pull the chair out from under you, or b) you yourself are going to miss the chair and pratfall to the floor. You may completely bypass happiness in the fog. When a passer by looks you in the eye and smiles, you may think they’re aiming right past you. There’s a simple solution to this problem: take a new picture. A self-image that stays put is best made using a long exposure time. The easiest way to do this is to get a cardboard box from your local grocery – anything will do, a pineapple box, whatever – and build your own pinhole camera, or camera obscura. This technique is sure to work. Just seat the off-kilter person in a chair and aim the pinhole camera at them. With long exposure time, the spine of the out-of-kilter person will seem to straighten of its own accord, since you can’t flinch or slouch. The image inside the camera will look upside down, and that is precisely the point. The person portrayed on the paper will glow with light and become translucent – the bones, the spreading wings. You will see yourself for the first time. There I am, you’ll laugh, born from the light! Then you’ll open the right door, meet someone’s gaze and return it, like a child or some other equally wondrous thing.

_______________________

“Coffee glides into one’s stomach and sets all of one’s mental processes in motion. One’s ideas advance in column of route like battalions of the Grande Armée. Memories come up at the double, bearing the standards which will lead the troops into battle. The light cavalry deploys at the gallop. The artillery of logic thunders along with its supply wagons and shells. Brilliant notions join in the combat as sharpshooters. The characters don their costumes, the paper is covered with ink, the battle has started, and ends with an outpouring of black fluid like a real battlefield enveloped in swaths of black smoke from the expended gunpowder. Were it not for coffee one could not write, which is to say one could not live.”

— Balzac

Coffee!!!Daily Rituals Entry 4 Mason Currey

_______________________

Berkeley #57

Richard Diebenkorn

(April 22, 1922 – March 30, 1993)

_______________________

Poems

Stephen Dunn

The Cortland Review

If A Clown

If a clown came out of the woods,

a standard looking clown with oversized

polkadot clothes, floppy shoes,

a red, bulbous nose, and you saw him

on the edge of your property,

there'd be nothing funny about that,

would there? A bear might be preferable,

especially if black and berry-driven.

And if this clown began waving his hands

with those big, white gloves

that clowns wear, and you realized

he wanted your attention, had something

apparently urgent to tell you,

would you pivot and run from him,

or stay put, as my friend did, who seemed

to understand here was a clown

who didn't know where he was,

a clown without a context.

What could be sadder, my friend thought,

than a clown in need of a context?

...(more)

_______________________

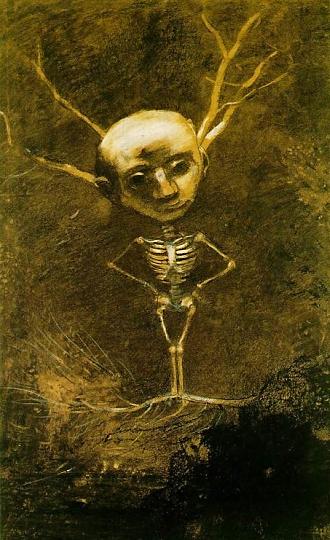

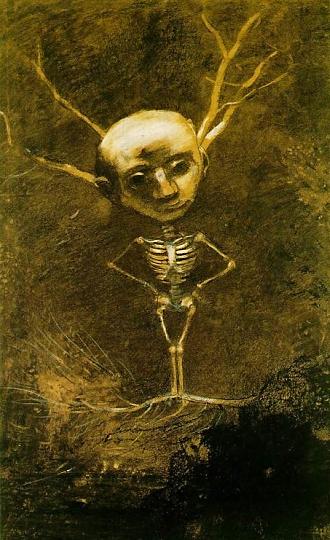

Spirit of Forest

(Specter from Giant Tree)

Odilon Redon

1880

_______________________

The Right to Be Forgotten: A Comparative Analysis

Laura Lagone

Abstract:

Before the Internet, people could make mistakes without the fear of being haunted by them in the future. Embarrassing information was usually contained in one’s community and typically forgotten over time. At the extreme, one could always move to a new neighborhood or find a new job in order to start fresh. In today’s Internet age, however, it is no longer easy to escape one’s past when personal information can go viral in a matter of minutes, search results retain old information, and more data gets stored in the cloud.

_______________________

Battlefield

1907

Käthe Kollwitz

(July 8, 1867 - April 22, 1945)

_______________________

... all of our experience suggests that it is not “fundamentalism” alone but an aching tension between modernity and a false picture of a purer fundamentalist past that makes terrorists.

(....)

The toxic combination of round-the-clock cable television—does anyone now recall the killer of Gianni Versace, who claimed exactly the same kind of attention then as Dzhokhar Tsarnaev did today?—and an already exaggerated sense of the risk of terrorism turned a horrible story of maiming and death and cruelty into a national epic of fear. What terrorists want is to terrify people; Americans always oblige.

Experts tell us the meaning of what they haven’t seen; poets and novelists tell us the meaning of what they haven’t seen, either, but have somehow managed to fully imagine. Maybe the literature of terrorism, from Conrad to Updike (and let us not forget Tolstoy, fascinated by the Chechens) can now throw a little light on how apparently likable kids become cold-hearted killers. Acts of imagination are different from acts of projection: one kind terrifies; the other clarifies.

— Adam Gopnik

_______________________

Ocean Park No. 130

1985

Richard Diebenkorn

_______________________

A Place in the Country

WG Sebald

An extract from the first English translation of a collection of WG Sebald's essays

Translated by Jo Catling.

At the end of September 1965, having moved to the French-speaking part of Switzerland to continue my studies, a few days before the beginning of the semester I took a trip to the nearby Seeland, where, starting from Ins, I climbed up the so-called Schattenrain. It was a hazy sort of day, and I remember how, on reaching the edge of the small wood covering the slope, I paused to look back down at the path I had come by, at the plain stretching away to the north crisscrossed by the straight lines of canals, with the hills shrouded in mist beyond; and how, when I emerged once more into the fields above the village of Lüscherz, I saw spread out below me the Lac de Bienne, and sat there for an hour or more lost in thought at the sight, resolving that at the earliest opportunity I would cross over to the island in the lake which, on that autumn day, was flooded with a trembling pale light. As so often happens in life, however, it took another 31 years before this plan could be realised and I was finally able, in the early summer of 1996, in the company of an exceedingly obliging host who lived high above the steep shores of the lake and who habitually wore a kind of captain's cap, smoked Indian bidis and seldom spoke, to make the journey across the lake from the city of Bienne to the island of Saint-Pierre, formed during the last ice age by the retreating Rhōne glacier into the shape of a whale's back – or so it is generally said. The ship which took us along the edge of the Jura massif where it plunges steeply into the lake was called the Ville de Fribourg. Among the other passengers on board were the gaudily attired members of a male voice choir, who several times during the short crossing struck up from the stern a chorus of "Ląhaut sur la montagne, Les jours s'en vont" or another such Swiss refrain, with the sole intention, or so it seemed to me, of reminding me, with the curiously strained, guttural notes their ensemble produced, of how far I had come meanwhile from my place of origin....(more)

_______________________

Flower Clouds

c. 1903

Odilon Redon

_______________________

Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking

Walt Whitman

Out of the cradle endlessly rocking,

Out of the mocking-bird's throat, the musical shuttle,

Out of the Ninth-month midnight,

Over the sterile sands and the fields beyond, where the child

leaving his bed wander'd alone, bareheaded, barefoot,

Down from the shower'd halo,

Up from the mystic play of shadows twining and twisting as if they

were alive,

Out from the patches of briers and blackberries,

From the memories of the bird that chanted to me,

From your memories sad brother, from the fitful risings and fallings I heard,

From under that yellow half-moon late-risen and swollen as if with tears...

...(more)

Basil Bunting chants Whitman

mp3

photo - mw

_______________________

Steampunk Zone

Carmine Starnino

from Carmine Starnino’s Lazy Bastardism, Gaspereau Press, 2012

Lemon Hound

In our mashup-mad era, we yearn for unpigeonholeability. We don’t want to be different. We want to be weird. We want to be total category-killers. As a result, it’s hard to find a poet – free-versifier and formalist alike – who doesn’t believe at heart that he or she is far too heterodox to be trapped in existing definitions of traditional and experimental. Contemporary poetry now comprises a vast invented form: the godknowswhat.

That the selections in Best Canadian Poetry in English 2012 echo and reprise this yearning should come as no surprise. From Rachel Lebowitz’s unnerving, nursery rhyme-inflected prose cycle (‘Cottonpolis’) to Robert Earl Stewart’s smoky, image-loaded stream of consciousness (‘A Wind-Aided Fire’), this book is a mixed bag. It’s the outcome, one might say, of a collective decision taken by Canadian poets to dart in all directions at once. To be sure, I plucked these poems from print and online journals with no bias except to find verse that provided a fresh entry into reality; that offered something, some equivalence between sound and feeling, I didn’t already know, or couldn’t find elsewhere. Good poets are stylists, and I hunted for styles whose distinctive qualities generated memorable insights. Yet, when assembled, many of the one-of-a-kind elements I admired – which each seemed unexpected, an emergency measure – turned out to share the same triggers. It made me uneasy. Don’t misunderstand: these are wickedly good poems. But the task of finding them has forced me to reflect on the high price of writing under the influence of what F.R. Leavis would have called our ‘poetical modes’.

(....)

Canadian poetry seems ideally suited to this era. Its masterworks, such as Irving Layton’s ‘A Tall Man Executes a Jig’ or A.M. Klein’s ‘A Portrait of the Poet as Landscape’, have always been marked by a glorious miscegenation of influences; or, to use Peter Van Toorn’s words from his 1985 book Mountain Tea, ‘there’s always a carnival voice?/calling you inside to see the choice?/of goods usually hawked at the honeyed?/gates of paradise’. Heeding this carnival voice has turned the recent scene into a teeming bazaar, where younger poets proudly wear the bright, patchwork clothes of their cosmopolitan nurturing. But something else defines this group. They are the first generation for whom the battle lines of mainstream versus avant-garde (what an earlier time dubbed ‘cooked’ and ‘raw’) have outlived their usefulness. The intense need to set free a shifting sense of self has helped produce the unusual range of devices in this book: intricate puns, up-to-the-minute slang, scat-singing wordplay, many-sided metaphors. These devices are brandished by poets who have not only come out the other side of the poetry wars, but aspire to heal the divisions in their poems. We see this in the cerebral, cubist elegance of Lisa Robertson’s ‘Scene’ or the flagrantly self-conscious, gear-switching rhymes of Shane Rhodes’ ‘The Paperweight’ or the ludic largess of Adam Dickinson’s ‘Call to Arms’. These poets belong to a circle that aggressively resist schools, unsettles assumptions and crossbreeds near-infinite varieties of form, from rhyme-rich free verse to mishmashes of lyric and found texts.

...(more)

_______________________

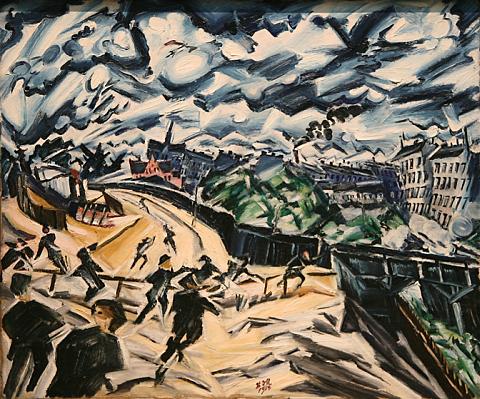

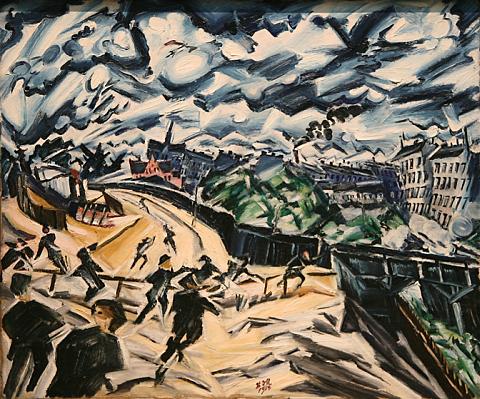

Apocalyptic landscape

1913

Ludwig Meidner

(18 April 1884 – 14 May 1966)

_______________________

Border Control in America before Ellis Island

Hidetaka Hirota

While Ellis Island is now widely recognized as a historical icon of the American immigration experience, some important questions remain to be addressed. Where did federal immigration regulation law come from? How was immigration to the United States regulated prior to Ellis Island? What was the relationship between earlier practices of immigration control and federal regulatory policy that developed from the late nineteenth century onward?

...(more)

_______________________

"A Once Perfect Day for Bananafish "

Mieko Kawakami

Translated by Hitomi Yoshio

Electric Literature's Recommended Reading

THE OLD WOMAN ON THE BED AT THE END OF HER LIFE, the true, absolute end. In a faint flicker, she dreams a dream all in yellow. A yellow, hot summer’s day. The old woman lives there, in the faint flicker.

In her bedroom piled with familiar objects, all we know are the bits and pieces that have kept on piling up. On this day of absolute solidity, in our eyes, she has lived for so long. The curtains always half-closed, at times matching her eyelids. In our eyes, the old woman lies still. In our eyes, the old woman lies still for a long, long time. Very lying still on the bed.

(....)

The old woman on the bed at the end of her life, the true, absolute end. In a faint flicker, she dreams a dream all in yellow. A yellow, hot summer’s day. The old woman lives that day, in the faint flicker.

...(more)

originally appeared in Monkey Business_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Monday

Lisa Robertson

from the weather

First all belief is paradise. So pliable a medium. A time not very long. A transparency caused. A conveyance of rupture. A subtle transport. Scant and rare. Deep in the opulent morning, blissful regions, hard and slender. Scarce and scant. Quotidian and temperate. Begin afresh in the realms of the atmosphere, that encompasses the solid earth, the terraqueous globe that soars and sings, elevated and flimsy. Bright and hot. Flesh and hue. Our skies are inventions, durations, discoveries, quotas, forgeries, fine and grand. Fine and grand. Fresh and bright. Heavenly and bright. The day pours out space, a light red roominess, bright and fresh. Bright and oft. Bright and fresh. Sparkling and wet. Clamour and tint. We range the spacious fields, a battlement trick and fast. Bright and silver. Ribbons and failings. To and fro. Fine and grand. The sky is complicated and flawed and we’re up there in it, floating near the apricot frill, the bias swoop, near the sullen bloated part that dissolves to silver the next instant bronze but nothing that meaningful, a breach of greeny-blue, a syllable, we’re all across the swathe of fleece laid out, the fraying rope, the copper beech behind the aluminum catalpa that has saved the entire spring for this flight, the tops of these a part of the sky, the light wind flipping up the white undersides of leaves, heaven afresh, the brushed part behind, the tumbling. So to the heavenly rustling. Just stiff with ambition we range the spacious trees in earnest desire sure and dear....(more)

.....................................................

The day pours out space (PoemTalk #65)

Lisa Robertson, "The Weather" ("Monday")

Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Kristen Gallagher, and Michelle Taransky

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

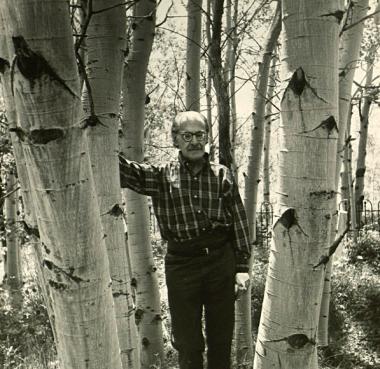

Anselm Hollo: 1934 – 2013

Rudy Rucker

exquisite corpse

(....)

I first heard of Anselm Hollo in 1972 when my writer friend Gregory Gibson mailed me a copy of that pamphlet-like book or chapbook, Sensation , published by a group calling themselves the Institute of Further Studies, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, traditional home of outrider poets such as Greg himself and of course Charles Olson. Not that Anselm was living in Gloucester. Born and to some extent raised in Finland, he was at this point drifting around the US from one visiting-poet gig to the next.

I read Sensation over and over, fascinated by its colloquial style and by Hollo’s trick of putting more than one twist into each poem—later when I met him he once remarked of some other poet’s work, “Just has one twist at the end, that’s not enough.”

Anselm’s poems are nicely musicked, yet elliptical and hard to pin down. What do they mean? No matter, never mind.

(....)

Anselm had an encyclopedic knowledge of world literature, and an exquisite mastery of the spoken word. He was wonderfully serious about writing. Whenever I was with him, I felt like I was talking to a sage on Mount Olympus, not that there was anything solemn about him. He’d often break into wheezing laughter while we were batting the ideas around. He had a cosmopolitan accent, having grown up Finnish. Anselm once remarked that every Finn deserved to have a biography written. But Anselm’s short, pungent poems are the most accurate memoirs of all, like X-ray snapshots of instantaneous mental states.

...(more)

Rowboats on the Estuary

1929

Alma Lavenson

1897 - 1989

1 2

_______________________

Fanaticism:

To Write A History Of A Thing Without History

Alberto Toscano

Preface to Fanaticism (2013)

verso

This first millennial decade, captivated by a spectacular, if ambiguous, resurgence of religiously motivated violence, has seen the revival of a charged term in the Western political lexicon: fanaticism. Societal upheavals, revolutionary periods, religious wars, crises of legitimation, imperial projects – in the past five centuries, all have provided occasions for invoking fanaticism to stigmatise incorrigible enemies, whose disproportionate convictions and intractable beliefs put them beyond the pale of negotiation. Millenarian German peasants, anti-colonial ‘dervish’ rebels, terrorising Jacobins, anarchist bombers, anti-slavery ‘immediatists’, and eschatological Stalinists are just some of the figures thrown up by an investigation into the adversarial uses of this powerful idea. Exploring the historical semantics and polemical deployments of fanaticism reveals, among other things, its impressive plasticity. Cultic superstition and unbridled rationality, the refusal of progress and its immoderate celebration, intransigent particularism and expansive universality have all been the targets of the accusation of fanaticism.

(....)