Janus Head Janus Head

11.1&2

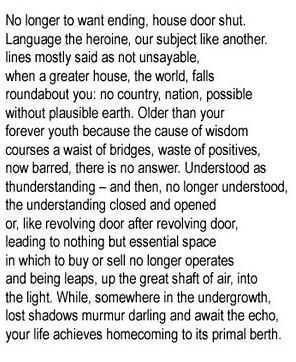

Travels Inside the Archive

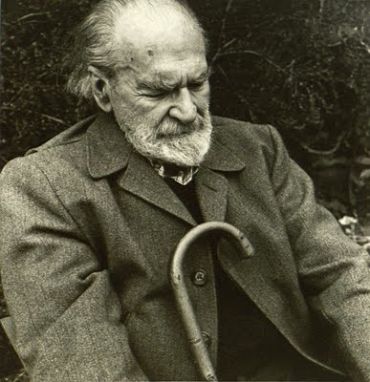

Robert Gibbons

Edge of Maine Editions

Beyond Time

New & Selected Work

1977 - 2007

Robert Gibbons

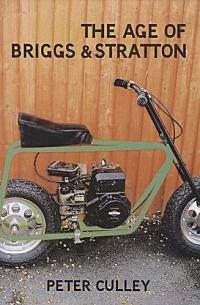

The Age of Briggs & Stratton The Age of Briggs & Stratton

Peter Culley

|

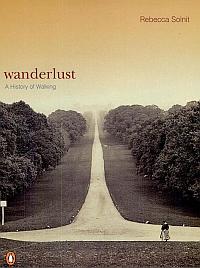

Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Rebecca Solnit

google books

Reviewed by Andrew O'Hehir

"Wanderlust" is a delightful, mind-expanding journey that strays from Søren Kierkegaard's Copenhagen and William Wordsworth's Lake District to the top of Everest and the New Mexico desert, from the first hominids to walk upright (whoever and wherever they were) to contemporary women who face the hazards of solitary walking. It's a journey led by a guide of tremendous erudition and just as much common sense, capable of slipping almost imperceptibly from the personal mode -- she describes several entirely non-metaphorical walks -- to the analytical and back again without appearing self-indulgent.(....)

The breadth alone of the material that Solnit has absorbed would have thwarted me; she's read obscure 19th century memoirs of walking tours, histories of mountaineering, feminist theory, studies of urban design, Victorian novels and Beat poetry. She knows more about the history of labyrinths and about the Renaissance mnemonic device called the memory palace than any normal person should. She's at her very best, I think, when her passion for history and landscape meets her progressive politics. (...)

In the end, the guiding spirit of "Wanderlust," the lonely traveler always in view on Solnit's horizon, is not Wordsworth or Rousseau but Walter Benjamin, whose rambles through the streets of Paris had the sense of wonder, the air of open-minded exploration and imminent discovery, of Solnit's own journey. Solnit observes the sexism and snobbery inherent in Benjamin's idea of the flaneur, the idle, solitary gentleman strolling through the crowds, but she can't quite resist it. In describing Benjamin's writing she seems to be half-consciously describing her own: "more or less scholarly in subject, but full of beautiful aphorisms and leaps of imagination, a scholarship of evocation rather than definition."...(more)

_______________________

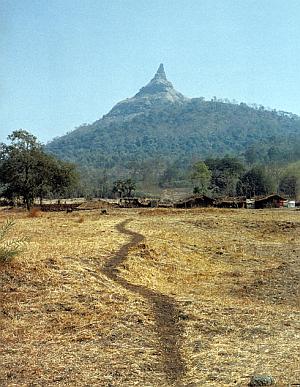

Art made by walking in landscapes

Richard Long

_______________________

Modernism and the Writing Hand

Steven Connor

1999

Beckett's texts also recoil away from this economy of the primally and permanently marked surface, this desire for what Lyotard has called `this first touch, which touched me when I was not there' [Jean-François Lyotard , `Prescription', L'Esprit créateur]. The self is not to be found either typographically fixed or organically ready-to-hand in its penmanship. Rather the self flares up in what Malone calls the `latitudes' of the hand, in the manifold self-touchings and contingencies of Beckett's text, including the touching-together of the economies of the pen and the keyboard. As in Ulysses, the hand, pen and keyboard mediate each other, creating a complex, self-organising phase-space of writing.

The hand haunts modernist writing: but not merely as a ghost of the bodily integrity or presence that have been lost in the age of type. The age of type forms a handiwork; the so-called abstraction is lived in the body. There is a cultural phenomenology of the typist body which is as complex, variable and lived as its predecessor. The soul of man does not slip out of his hands. (The pen falls, it is noted', we read in Texts for Nothing.) His hands are everywhere, because his hands are not things, his hands are contingencies, places of contact, commingling, mutual touching. Typing does not remove the hand of man from the world; it makes man ambidextrous.

My aim has been to show you that modernist writing never deserted the hand, though it may unavoidably have transformed it. My larger aim has been to discourage ephocal analysis and the deterministic cultural totalism it allows. I will conclude by suggesting that epochal analysis of the regimes of writing is in the grip of a particular, and inappropriate model of historical writing, a model in which one technological mode merely effaces and replaces another. The new technological determinism is tautological: it borrows the metaphors (of being stamped, imprinted, penetrated, forced into grooves) of the technology it aims to understand. But in fact technological determinism fails to recognise the transformations that it itself, and self-refutingly, effects. We have magical relations with machines. All machines are anachronistic; they have been invented long before they come about; they have begun to decay as soon as they do....(more)

_______________________

Storming the Gates of Paradise: Landscapes for Politics

Rebecca Solnit

google books _______________________

I continued to talk. As I say, I was lighted up. In my brain every thought was at home. Every thought, in its little cell, crouched ready-dressed at the door, like prisoners at midnight a jail-break. And every thought was a vision, bright-imaged, sharp- cut, unmistakable. My brain was illuminated by the clear, white light of alcohol. John Barleycorn was on a truth-telling rampage, giving away the choicest secrets on himself. And I was his spokesman. There moved the multitudes of memories of my past life, all orderly arranged like soldiers in some vast review. It was mine to pick and choose. I was a lord of thought, the master of my vocabulary and of the totality of my experience, unerringly capable of selecting my data and building my exposition. For so John Barleycorn tricks and lures, setting the maggots of intelligence gnawing, whispering his fatal intuitions of truth, flinging purple passages into the monotony of one's days.

-

Jack London, John Barleycorn

_______________________

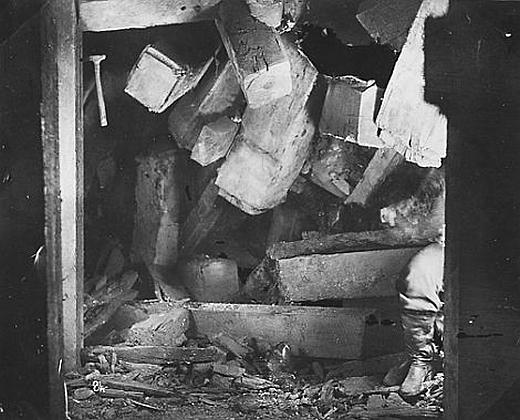

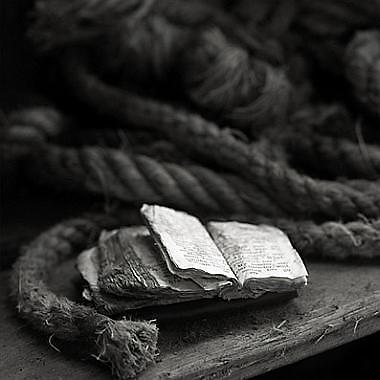

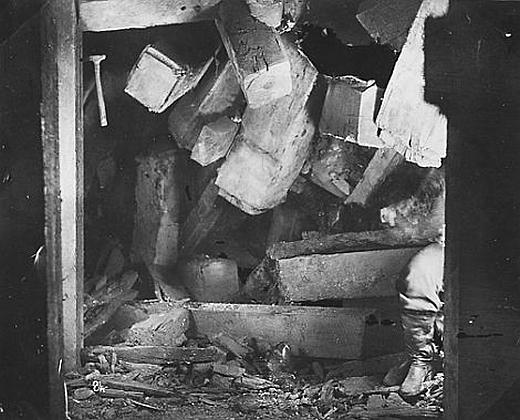

photo - mw

Crushed timbers

Gould and Curry Mine

1868

Timothy O’Sullivan

1840 - 1882

1 2

'Surrealistic and disturbing':

Timothy O'Sullivan as Seen by Ansel Adams in the 1930s

Britt Salvesen

Journal of Surrealism and the Americas, Vol 2, No 2 (2008)

Timothy O'Sullivan: Shadows of Subjectivity in the Photographer's Frame

Elizabeth Paul

_______________________

The Fiction of Memory

Luc Sante reviews David Shields' "Reality Hunger: A Manifesto"

... just because the novel is food for worms doesn’t mean that fiction has ceased. Only an artificial dualism would treat every non-novel as if it were reportage or court testimony, and only a fear of the slipperiness of life could perpetuate the cult of the back story. “Anything processed by memory is fiction,” as is any memory shaped into literature.

But we continue to crave reality, because we live in a time dominated by innumerable forms of extraliterary fiction: politics, advertising, the lives of celebrities, the apparatus surrounding professional sports — you could say without exaggeration that everything on TV is fiction whether it is packaged as such or not. So what constitutes reality, then, as it affects culture? It can be as simple as a glitch, an interruption, a dropped beat, a foreign object that suddenly intrudes. Hence the potency of sampling in popular music, which forces open the space between the vocal and instrumental components. It is also a form of collage, which edits, alters and reapportions cultural commodities according to need or desire. Reality is a landscape that includes unreal features; being true to reality involves a certain amount of wavering between real and unreal. Likewise originality, if there can ever be any such thing, will inevitably entail a quantity of borrowing, conscious and otherwise. The paradoxes pile up as thick as the debris of history — unsurprisingly, since that debris is our reality....(more)

_______________________

Cage

Savage Mine

Virginia City

1867

Timothy O’Sullivan

_______________________

From abuse to usufruct

Jean-Claude Monod

Translation by Mike Routledge

eurozine

... what is the point in recalling these ancient texts and economic dictates from a pre-capitalist, pre-industrial epoch? It is not, certainly, in the hope of finding in Aristotle principles of ethics for our modern-day economy, but rather to suggest that certain "essential" or fundamental perceptions, something resembling minimum principles of justice, underlie society's views of the abuse inherent in any relatively endless acquisition of wealth. Liberal theory, which claims that the unbridled pursuit of private interest "must" automatically and harmoniously combine with the common interest through the providential workings of the "laws of the market", has tended to efface from economic theory any basic notion of "abuse". The very basis of economics as a science is, we are told, the exclusion of any such ethical considerations.

Economic liberalism has thus managed to make its position impregnable: on the one hand, by means of a moral theory, determined by interest and a quasi-theology governing its own system of regulation; on the other, by claiming to be a science based on the exclusion of any morality not based on the premise that only private interest is rational. In fact, society's view of abuse resists being ideologically negated by pure market theory, and likewise rejects the morality of interest that surreptitiously underlies it. In his conclusion to what remains one of the fundamental works on economic anthropology, the Essai sur le don (The Gift), Marcel Mauss pointed this out: "Our moral code is not simply that of the shopkeeper [...] Nowadays ancient principles react against the rigours, abstractions and inhumanity of our codes [...] and such a reaction against Roman or Saxon lack of sensibility is perfectly natural and powerful."

"Roman or Saxon lack of sensibility" refers to the idea that social relationships are based solely on private interest, and that commercial exchange is the norm for any kind of contractual relationship. This kind of reduction or formalization, of which Roman law is a product, has served as a model for the most recent codes of civil law, especially when divorcing property rights from traditional or customary systems and from Christian economic ethics.

(....)

In the nineteenth century there appeared a variety of forms of resistance to what A.-M. Patault calls the "triumph of abusus" and of exclusivism, the assertion of an absolute right to use and to abuse property acquired, regardless of any concern for the common weal. The idea of usufruct, through broadening its semantic and practical horizons, could be placed in opposition to the assignment of absolute value to private interest alone. On the threshold of the twentieth century, a philosophical extension of this legal category was made by the solidarist thinker Léon Bourgeois in his book Solidarité:

It was for the benefit of all those called to life that those who have died created this capital of ideas, forces and aids. Consequently, it is for the sake of those who will come after us that we have inherited from our ancestors the responsibility for paying this debt [...] Each generation that follows can truly consider itself to be a usufructuary of this inheritance: it only has the right to hold on to it on condition that it preserves it and faithfully passes it on.

(....)

What do these various directions in political economics have in common? Restoring the bonds between the supplier of goods-as-services and their "users", in other words, going beyond the limited sales relationship and involving a two-way relationship. This would stem from a requirement for use that, rather than meaning unbridled exploitation of resources, is characterized by an awareness of the fragility of what one is using, and of the limits of what "possession" – always relative – allows one to do. Such policies on use are all focused on a certain attenuation of domination, both in the sense of domination over the planet and of social domination; of ecological abuse and the excessive rights that those in a dominant position seize for themselves when public systems for regulating economic inequities break down.

These brief notes and speculations about pathways that might be followed were intended to do nothing more than avoid the premature end to the political, ethical, and even spiritual approaches that the current crisis in financial capitalism and ecology might lead us to explore. They are aimed at revising our conception of "growth at any price", production for its own sake, and the acquisition of wealth as the yardstick for everything.

Regardless of any kind of political programme, it could be seen as an expression of concern (cosmopolitan in every sense of the term) for the way that the world is to be used; a concern to promote social and economic practices that can make use of the world without abusing it; a concern to find an answer to the sense of abuse that is so deeply rooted in us; a concern that responds to the twin spectacle of the breathtaking inequalities that divide our modern world, and the destruction of all that still makes it habitable, a place in which, in common, we may live and breathe....(more)

_______________________

East River Park

ca. 1902

William Glackens

(March 13, 1870 – May 22, 1938)

_______________________

The New Gilded Age and Neoliberalism’s Theater of Cruelty

Henry Giroux

One of the distinctive features of the modern American right has been nostalgia for the late 19th century, with its minimal taxation, absence of regulation and reliance on faith-based charity rather than government social programs. Conservatives from Milton Friedman to Grover Norquist have portrayed the Gilded Age as a golden age, dismissing talk of the era’s injustice and cruelty as a left-wing myth. Well, in at least one respect, everything old is new again. Income inequality — which began rising at the same time that modern conservatism began gaining political power — is now fully back to Gilded Age levels.

- Paul Krugman

What is often ignored by many theorists who analyze the rise of neoliberalism in the United States is that it is not only a system of economic power relations, but also a political project of governing and persuasion intent on producing new forms of subjectivity and particular modes of conduct. In addressing the absence of what can be termed the cultural politics and public pedagogy of neoliberalism, I want to begin with a theoretical insight provided by the British media theorist, Nick Couldry, who insists that “every system of cruelty requires its own theatre,” one that draws upon the rituals of everyday life in order to legitimate its norms, values, institutions, and social practices. Neoliberalism represents one such a system of cruelty, one that is reproduced daily through a regime of commonsense and a narrow notion of political rationality that “reaches from the soul of the citizen-subject to educational policy to practices of empire.”...(more)

_______________________

World’s billionaires grew 50 percent richer in 2009

Andre Damon

2009 will be remembered by millions of ordinary people as the year they lost their job, their house, or the prospect of an education. For the rich, however, it was a bonanza.

The world’s billionaires saw their wealth grow by 50 percent last year, and their ranks swell to 1,011, from 793, according to the latest Forbes list of billionaires....(more)

via I cite

_______________________

“The Spirit Level”

Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson

reviewed byJenna Russell

If you like to think of America as The Greatest Country on Earth, and you’d rather not examine its claim to that title too closely, “The Spirit Level” will not be your favorite new book. On nearly every one of its 250-plus pages, a stark, unflattering graph shows the USA topping the charts among developed countries for some social ailment: drug use, obesity, violence, mental illness, teenage pregnancy, illiteracy. But authors Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson, a pair of British social scientists, have another, more enlightening point to make. With striking consistency, they say, the severity of social decay in different countries reflects a key difference among them: not the number of poor people or the depth of their poverty, but the size of the gap between the poorest and the richest.(....)

PICKETT: Different societies achieve their levels of equality or inequality through different mechanisms, and it doesn’t seem to matter how you get there - the improved conditions seem to flow from more equality itself, not from particular policies. We’re not advocating any particular way....It’s important to realize how rapidly our inequality has grown, and how different our societies used to be. Inequality isn’t some entrenched characteristic. It’s become much worse since the 1970s. And we can shift things back.

via Follow Me Here...

_______________________

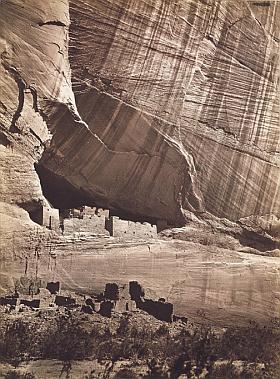

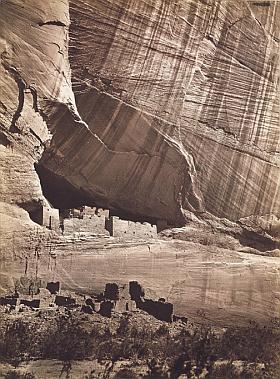

Canyon de Chelly

Timothy O’Sullivan

1873

_______________________

"new fiction starting. New characters."

A Shore Without A Sea

Spurious introduces 'the poet'

Of course, he's the last person I should call 'the poet', given that he's never written a line, and still thinks he's written too much. He has no, absolutely no, interest in writing poetry, he says.

The time of poetry is over, he says, and so is the time of those interested in or feel close to poetry. He, granted, is interested (to an extent) and feels close (in some ways) to poetry, but, in the end, has nothing to do with poetry. It has nothing to do with him!

Poetry's retracted, he says. It's withdrawn back into itself, The tide is out. Somewhere, far away, poetry is alive, lost in itself. Somewhere or other, there is poetry presing darkly into itself.

And he, who is he? A beachcomber? A tide-out walker? Not even that. For what does he understand of what has been left by poetry? How can he even read the signs of the former presence of poetry? ...(more)

_______________________

Camaret

Maximilien Luce

1894

_______________________

Eckhardt: 'Only the hand that erases can write the true thing'.

Lars (LarsSpurious) on Twitter

Beirut 1991

Gabriele Basilico

_______________________

Black Lips

Jazra Khaleed

Translation by Peter Constantine

Words Without Borders

Listen

You who chew on my solitude

with your televisions on

You who attend my funeral every morning

to light a candle

Listen

I will drive a verb into your eyes

I will plant a beat in your chests

I don’t have a cent in my heart

or smooth talk and epithets hidden in my pocket

I scatter my beauty on concrete streets

I dip my hands in poets’ blood

I write everything in 9 mm caliber

There’s no one for me to respect

A twenty-one-year-old Muslim punk

I bear no responsibility

I spit words at 120 B.P.M.

...(more)

_______________________

Canyonlands

Edward Abbey in the Great American Desert

Unknown Territories

Interactive Panoramic Environments and Cinemascapes

Roderick Coover

.....................................................

Roderick Coover, Larry McCaffery, Lance Newman and Hikmet Loe: A Conversation.

Following upon the release of his Unknown Territories project, an interactive documentary project about how writing and images shape interpretations of the Western landscape, Roderick Coover invited literary scholars Lance Newman and Larry McCaffery and art historian Hikmet Loe to explore the question of how desert ecologies are shaped through creative expression and actions. Their conversation goes on to consider how works Edward Abbey, Robert Smithson, William Vollmann, and the Center for Land Use Interpretation, among others, offers models for engaging ecological questions through writing and art.

Mccaffery: Most people probably think of the desert in terms of its emptiness, but my own sense of the desert is really quite the opposite. Part of this ecstatic sense that so many people talk about when describing their response to the desert has to do with the fact that when you remove trees, buildings, billboards, highways and all the other encumbrances from your line of vision, your consciousness becomes overwhelmed by the sheer abundancy of what you're encountering. Suddenly you look out and you're not seeing 10 yards ahead of you, or 100 yards, or even a mile, but maybe 20 miles or more. There's so much incoming data, but so little in the way of a framework that allows you to contextualize this data, that the mind short circuits. So, yes, on the one hand the desert is empty of civilization - it forms a kind of mental frontier where all the projects of civilization run into the ground, where all this excess of signification, of intention and pretension in culture is drained away. But that absence allows you to experience directly something far grander: the desert as this vast aesthetic spectacle. For me, anyway, this sensation is literally mind-expanding.

(....)

Newman: There's a great moment in Abbey's essay "The Great American Desert" where he's circumambulating Navajo Mountain on the north shore of Lake Powell. He's having one of those long walks that's interminably the same, the way you describe, Rod. He then makes a short climb, and, in the middle of nowhere, in a space where he thought there had never been another human being, he comes across an arrow sign that's made out of rocks in the dust that's been there for centuries. It's packed in sedimented dust. This conflicts with the conventional way of thinking about these deserts as inhuman spaces, as spaces empty of human inhabitants - the ultimate wildernesses in the way that wilderness is defined by the Wilderness Act of 1964. Really, that's an illusion. One of the things that you learn after years of walking in deserts is how to see the record of human inhabitation of those spaces. This segment in Abbey's work also expresses the idea that walking in the desert is a form of improvisation....(more)

_______________________

Fritz Fabert

1 2

_______________________

Apology in a Complex Mirror

I’m sorry to have to say it

that way. “Daily accumulation

of face” aging. What did I

not say. Relative depth

of waiting, angle of

having waited having said.

Of force. Roar of crowd at

particularly lucky shot.

So we wait beneath

our faces, sorry for

having to say what we

couldn’t not say, aging.

Apology in a Complex Mirror & other poems

David Hadbawnik

exquisite corpse

More poems by David Hadbawnik 1 2 3 4

_______________________

Gabriele Basilico

1 2 3 4

via Joerg Colberg _______________________

The System

Ron Padgett

I just wrote a rather bad poem,

but at least I’ve gotten it out of my system,

though I don’t know what system

that might be. My nervous system?

Is my system nervous? My aesthetic system?

Is beauty a system? My spirit’s system?

Surely spirit is beyond system. Why

do I say that? Maybe the spirit has a system

or is part of one. But what if that system

is an accident, a chance arrangement

as inchoate as chaos? It would be a system

anyway. System is a word we press up against

to make ourselves have life, a life-support system,

you might say. That is, without words we can’t stay alive.

So I’m glad I am writing this, glad

that I’ve gotten it into my system.

Poems

Ron Padgett

Drunken Boat | 9 | Winter 2007

Ron Padgett at PennSound

_______________________

Being Gazed Upon

G.L. Mind

There are many kinds of looks, but a gaze is peculiar. It is a steady look. It is not a dirty look, though it may be “dirty” in some sense. (The man’s gaze made me feel dirty, among other complex sensations, but it was hardly a dirty look.) A gaze is never wild, though it may be mad. A gaze may not actually last long, but it is never a blink, neither hasty nor abrupt. It cannot be confused with a glance or a glimpse. There may be a battle of gazes. The gazer may “avert his gaze” under pressure or threat. I was afraid, and had no way to explore this option in Chicago. A gaze’s steadiness reflects thoughtfulness. It indicates a mind at work (somewhere, unknown and remote) thinking, drawing inferences, contemplating. It is the opposite of a stare. A stare shows dispassion, even an implacable lack of emotional connection. It is the look of an animal contemplating prey, or that of an android. (Tracking and identification data scroll down a head’s-up screen covering its field of vision.) A stare, heartless, without empathy, is the way you might expect a psychopath to consider you before making his kill. Men seem to understand the weight of intimidation that a stare can convey: in many sports, such as boxing, the initial stare-down is a ritual of domination. Even in make-believe, a stare displays an aggressive contempt and indifference: pitiful bug, I am going to destroy you. However brief, a gaze indicates thoughtfulness. The gazer seems to contemplate the person he gazes upon and even to invite connection....(more)

Archipelago: Volume 9Among the Vanished and

Death Crab by G. L. Mind

word riot

_______________________

Valencia

Gabriele Basilico

_______________________

Kit Robinson’s “Return on Word”

a few good words (PoemTalk #29)

Rae Armantrout, Linh Dinh, Tom Devaney and Al Filreis

If we look in the direction

these words will have to do

adding to the enormous burden of words

The entire concept

is entirely too conceptual

all we need is a few good words

Anybody can relate to

to declare an identity

no one can take away

(....)

We are going to have a great year

there is going to be hell to pay

it’s gonna be a fuckin bloodbath

Then the return to words

thought has taken a contract out on

in order to move them around

...(more)

_______________________

Making the Mind Whole

Douglas Messerli on Charles Bernstein

American Cultural Treasures

In “Matters of Policy,” the reader is asked to participate with the poet in an exploration of the failures and successes of contemporary American culture, a culture that has assimilated and now presumes the great technological advancements of this century, a society that, through “electricity” and “Speed,” has seemingly been given more time for amusement and, thus, has achieved a greater worldliness than any society in history. As the poet somewhat cynically observes:

....Electricity hyperventilates even the

most tired veins. Books strew the streets.

Bicycles are stored beneath every other staircase.

The Metropolitan Opera fills up every night as the

great masses of the people thrill to Pavarotti,

Scotto, Plishka, & Caballe. The halls of the

museums are clogged with commerce. Metroliners

speed us here & there with a graciousness

only imagined in earlier times. Tempers are

not lost since the bosses no longer order about

their workers. Guacamole has replaced turkey as

the national dish of most favor. .....(“Matters of Policy,” p. 4)

In such a post-Mauberlian world, guacamole may have cast out turkey (as “croissants” have replaced “absinthe”, but, along with the poet, what we “most care about / is another sip of....Pepsi-Cola”. For, the benefits of change have engendered not only extreme eclecticisms, but an insatiable desire for change itself, as if it, too, were a consumer product; “Even nostalgia has been used up”. Our perspective has shifted from despair for what we have lost to impatience for what the future is about to bring. The “wasteland” has metamorphosed into “a broad plain in a universe of / anterooms”, into one boundless waiting place.

But what is most disturbing, Bernstein hints, is not that we wait, but how we wait. There is a “spirit / of the place–a certain je ne sais quoi that / lurks, like the miles of subway tunnels, electrical / conduits, & sewage ducts, far below the surface”; there is a passive acceptance of the future that is of far greater import than the customs and values we have surrendered. As we (like our reporters) “sit around talking over Pelican Punch tea about the underlying issues”, there is a danger that we will fail to note our own demise, there is a possibility that we may become the “matters of policy” – the subjects of a course of action. Will we be determined by or will we determine our future technology? The poet fears that, although there’s now “plenty of time,” there are few individuals “with enough integrity or intensity to / fill it with the measure we’ve / begun to crave”....(more)

_______________________

Fritz Fabert

west of Kaladar

trans-Canada highway

photo - mw

Into the Woods

Silje Bekeng

[n1br: issue six]

Norwegians are said to be born with skis on their feet—ready from birth for a life in harmony with the inhospitable Nordic nature.

Maybe my mother was lacking some important vitamin during the pregnancy. No skis accompanied me into this world. Instead of seeking the woods and mountains like a true Norwegian—"There is no bad weather, only poor clothing!" as we say—I came to prefer asphalt under my feet, the safety of skyscrapers, and the soft breeze from passing subway cars, deep underground. I am allergic to trees.

But I didn't miss out on the other thing Norwegians are born with: citizenship in the world's most generous and equitable welfare state.

This is about what happens when rich, well-traveled, and well-educated children from a tiny Viking country covered in forest grow up and try to write fiction....(more)

_______________________

'The Politics of Aesthetics': Jacques Rancière Interviewed by Nicolas Vieillescazes

There is no opposition between a trans-historical orientation and an historical critique. Philosophy, as I practise it, is not a science of the Eternal. It deals with the singular knots that bring into being this or that configuration of experience: art, politics, social life, philosophy itself. I embarked on a study of workers’ archival resources because I wanted to escape the dogmatic categories for thinking history, the workers’ movement, class struggle, etc. I set these against the uniqueness of the workers’ emancipation by mobilizing the resources of the historian, the philosopher and the writer, that is to say by blurring the boundaries that are meant to separate not only disciplines, but also the theoretical and the empirical, the scientific and the poetic. When working on Plato’s texts on the division of labour, Aristotle’s texts on the unique sensibility of the political animal or Hannah Arendt’s work on “political life”, I did so by constantly translating these propositions into the terms of the distribution of the sensory that I analyzed in its most concrete form through the workers’ archives: I approached Plato’s work on the artisan’s “absence of time” via a carpenter’s texts, and the difference between Aristotle’s human speech and animal voice through 19th century strikers’ manifestoes. It is not a case of a return from history to philosophy but rather a constant use of one form of discourse and knowledge so as to challenge another. The historical helps to deconstruct philosophical truisms, but, moreover, philosophical categories help to identify what is widely at stake in what historians always present as realities and mentalities that cannot be dissociated from their context. I wished in this way to allow for a thinking capacity that resists confinement within disciplinary boundaries that function as taboos. To go from the historical mode to the philosophical mode and vice-versa means that thought is one and that everyone thinks....(more)

Naked Punch

_______________________

Ratzeburg

East/West German Border

1987

The Lost Border

Photographs of the Iron Curtain

Brian Rose

_______________________

Speaking Places

Nathaniel Tarn and the Poetics of Voicing Culture

Richard Deming

Tarn’s arguments move from discussions of place and voice out to include a model of poetry as the means of transforming the perpetual human condition of absence or loss or exile into a generative, inclusive sense of being. In Tarn’s view of things, poetry is not a way of resolving that feeling of exile, instead it is a means of finding one’s way towards the freedom of exile. Along the way of addressing the implications and context of Tarn’s ideas, I will point to relevant examples of this incredibly expansive and decidedly challenging poet’s oeuvre, which is superbly represented in a recent selection, published by Wesleyan University Press. To first locate the staging of Tarn’s poetics, though, we might begin by looking to one of modernism’s most influential and most ambitious voices (Wallace Stevens)....(more)

A Multitude of One: Celebrating Nathaniel Tarnin the emerging Jacket 39

_______________________

“A Lot of Guys Who Know All About Bricks”

Mark Silverberg's introduction to The New York School Poets and the Neo-avant-garde: Between Radical Art and Radical Chic

jacket

_______________________

Women who blog

about poetry & poetics

a master list from Ron Silliman

_______________________

On the Vanity of This Life

Competing for position

And shares of the best stock.

This one hides in the dark,

That one wanders the block,

Another remodels his cave.

Some sing, and others groan.

Some serve while others rule.

And while we love our prison

As if it were no prison,

Death comes in his black cape,

His broad black hat and gloves,

And helps us to escape.

Thomas Moore [pdf]

translated from the Latin by Jerry Harp

Pleiades Magazine—volume 30, number 1, 2010

_______________________

The Lost Border

Brian Rose

_______________________

Impolitic: Kent Johnson’s Radical Hybridity on Doubled Flowering: [pdf]

Michael Theune

pleiades

Attempting to heal rifts in American poetry and poetic theory, middle space thinking and poetry do not then want to create new divisions by providing what one in fact expects of a significant literary movement: a new kind of revelatory theory about or approach to writing, one that would be critically decisive and, thus, of necessity, exclusionary. And yet, of course, exclusions were being made all the time: particular middle space poems were being published and anthologized, others not; particular middle space manuscripts won awards, others not. However, because there has been no substantive middle space thinking, no real middle space reasons have ever been offered for these choices. Instead, such choices have come to seem the results more of sociological factors than of any kind of aesthetic urgency—the middle space anthologies certainly abound with in-group selectivity. The rise of the middle space and the advent of Foetry are not entirely coincidental.

As a result, though swaddled in the sheen of the new, middle space thinking has ended up mostly feeding into and supporting poetry business as usual, allowing, and in fact requiring (because it in fact offers so little that’s new), poetry to quickly fall back onto old taxonomic systems and evaluative judgments.

(....)

Kent Johnson is one of the great critics of the middle space. Though prolific—Johnson is the author of numerous books and chapbooks, an active translator (including, most recently, of two books, co-translated with Forrest Gander, by Bolivian poet Jaime Saenz), and the editor of four anthologies, including Beneath a Single Moon: Buddhism in Contemporary American Poetry, Third Wave: The New Russian Poetry, and two books featuring work by Araki Yasusada—Johnson is much less well-known than he deserves to be. Johnson deserves greater recognition because in the past decade he has emerged as one of the middle space’s most significant thinkers and indisputably inventive poets. Johnson’s significance in this regard, however, is not the result of an easy fit into the middle space but rather is due to the fact that Johnson situates his work at odd angles in and to the middle space in order to engage, challenge, and even disrupt the often facile middle space. What follows is not a full review of Johnson’s complete oeuvre or even all of his significant recent work, but rather an extended examination of Johnson’s work, specifically, as middle space poet and provocateur, the gadfly, the muckraker of the too-well-oiled middle space machine....(more)[pdf]

_______________________

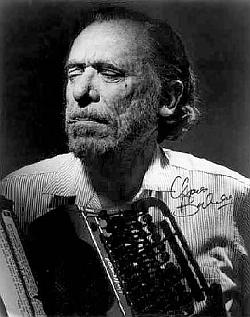

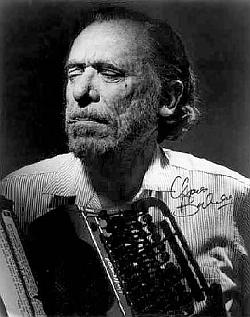

Charles Bukowski

(August 16, 1920 – March 9, 1994)

Friends Within The Darkness

I can remember starving in a

small room in a strange city

shades pulled down, listening to

classical music

I was young I was so young it hurt like a knife

inside

because there was no alternative except to hide as long

as possible--

not in self-pity but with dismay at my limited chance:

trying to connect.

the old composers -- Mozart, Bach, Beethoven,

Brahms were the only ones who spoke to me and

they were dead.

finally, starved and beaten, I had to go into

the streets to be interviewed for low-paying and

monotonous

jobs

by strange men behind desks

men without eyes men without faces

who would take away my hours

break them

piss on them.

now I work for the editors the readers the

critics

but still hang around and drink with

Mozart, Bach, Brahms and the

Bee

some buddies

some men

sometimes all we need to be able to continue alone

are the dead

rattling the walls

that close us in.

photo - mw

_______________________

Questions and Answers on Environmental Poetics

James Sherry in conversation with Stan Apps

jacket

Environmental poetics contains that critique of the machine, but includes human rational processes, such as technology, as part of nature. As Kant said, "Reason is a gift of nature." Putting humanity and nature together allows us to expand the possibilities of nature for poetry. Otherwise nature poetry can tend to be dull or repetitive.

Environmental poetics does not focus on writing poems with nature as the theme. Instead it relates to nature through patterns of organization. It focuses on relationships, rather than describing our environment as an array of things in a container.

(....)

...even the most celebrated eco-poets like Gary Snyder and Theodore Roethke have only scratched the surface of possibilities that need to be explored in developing a culture that links humanity and nature. Without that more complete culture based on environmental principles to support the science and politics of change, humanity will have difficulty generating the will to change because our self-centered myths about nature prohibit us from seeing the larger picture or even seeing the details accurately....(more)

James Sherry at PennSound

_______________________

Quadrat 1+2

Samuel Beckett

(1982)

UbuWeb Film

Marjorie Perloff Picks UbuWeb’s Top Ten for March 2010

bist eulen?

(1984)

Ernst Jandl (1925-2000)

UbuWeb Sound

_______________________

Predatory Habits

How Wall Street Transformed Work in America

Etay Zwick

Pick up the New York Times today, and you’re likely to read yet another article about finance’s infidelity with the general public, another violation of the (invisible) norms of propriety. It is only with immense discipline, a well-stocked inventory of financial jargon and a readiness for self-deception that one can actually distinguish these “violations” from business-as-usual. Yet despite ubiquitous references to Wall Street offenses, maybe even because of them, Americans don’t seem deeply troubled, or even all that perplexed, that this abusive sector remains largely undisturbed. Most of us can dutifully recite the scandals and statistics, but few dare to imagine life without Wall Street. For all the talk of a rapidly evolving economic environment, we treat one feature of this environment as permanent: the existence of a class of individuals who make millions by making nothing. We’re no longer surprised to see business elites divine exorbitant bonuses, paid for through record unemployment levels and unprecedented government support. This trick is getting old.

Though Wall Street consistently updates its instruments and practices, one governing rule has remained since Veblen’s time: financial propriety has nothing to do with social and economic growth. Certain rules must be followed, but the construction of those rules is absolutely distinct from considerations of general social welfare. Rather, regulations and rules are defined according to the culture’s metric of success, of value, of esteem—and that metric is money. All financial practices that increase the wealth of the sector are not merely permitted, they are required. No profitable innovation can be ignored. Destabilizing the global economy is fine. Undermining one’s firm, or jeopardizing the system of trading and speculating, is not.

Finance today is not geared toward getting entrepreneurs the credit they need to actualize their good ideas. It is riddled with archaic social forms that perpetuate barbaric status anxieties. The appeal of the Wall Street lifestyle—money, clean working conditions, (paradoxical) status as stewards of prosperity—has blighted the rest of society with its message that the best kind of work is devoid of social utility, knowledge and permanence. Nonetheless, we continue, even in the wake of economic crisis, to accept the barbarians’ rules for social and economic life. The discussion in government today revolves around minor matters of transparency and enforcement. The barbarian does not abide by rules; indeed, it is a point of pride that he knows his way around them. No matter what regulations are passed, the barbarian will figure out a way to make money from them....(more)

The Point MagazineIssue Two, Winter 2010 via Dialogic

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

We can no more renounce the devil than we can renounce physicality, the abuse of power, and the pleasures of sanctimony, hierarchy, gorgeous costumes, pageantry and hypocrisy. The more we denounce and externalize the devil, the more we cast him into hell, the more Satanic we become. That was the truth of the great ages of satire, and I am sure a long exploded heresy, for which any number of heretics have been burned at the stake by any number of holy men holding the cross before the sinner's eyes and feasting on his agony.

- Phil Cubeta

_______________________

Neither party rules. Corporations do the ruling. Politicians conduct the public sing-along about democracy.

Like anyone else who has soberly observed this age of peak everything, and the avaricious clowns in charge of our future, I'm a doomer. Even if Abe Lincoln, FDR or Gandhi were in charge at this point, I'd be a doomer. But with enough booze, I can gut it out in relative cheer. As for making predictions, I try to avoid it. You see, I am in the racket of appearing as if I might know these sorts of things, so publishers will pay me money. It's a delicate balancing act. Readers believe way too much of what I say, and my wife doesn't believe anything I say. Fortunately, my dog is a good listener and never comments, unless there is bacon involved.

- Joe Bageant

_______________________

There's something deeply unsettling about living in a country where millions of people froth at the mouth at the idea of giving health care to the tens of millions of Americans who don't have it, or who take pleasure at the thought of privatizing and slashing bedrock social programs like Social Security or Medicare. It might not be as hard to stomach if other Western countries also had a large, vocal chunk of the population who thought like this, but the US is seemingly the only place where right-wing elites can openly share their distaste for the working poor. Where do they find their philosophical justification for this kind of attitude?

It turns out, you can trace much of this thinking back to Ayn Rand, a popular cult-philosopher who exerts a huge influence over much of the right-wing and libertarian crowd, but whose influence is only starting to spread out of the US.

One reason why most countries don't find the time to embrace her thinking is that Ayn Rand is a textbook sociopath. Literally a sociopath: Ayn Rand, in her notebooks, worshiped a notorious serial murderer-dismemberer, and used this killer as an early model for the type of "ideal man" that Rand promoted in her more famous books -- ideas which were later picked up on and put into play by major right-wing figures of the past half decade, including the key architects of America's most recent economic catastrophe -- former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan and SEC Commissioner Chris Cox -- along with other notable right-wing Republicans such as Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, Rush Limbaugh, and South Carolina Gov. Mark Sanford.

The loudest of all the Republicans, right-wing attack-dog pundits and the Teabagger mobs fighting to kill health care reform and eviscerate "entitlement programs" increasingly hold up Ayn Rand as their guru. Sales of her books have soared in the past couple of years; one poll ranked "Atlas Shrugged" as the second most influential book of the 20th century, after The Bible.

So what, and who, was Ayn Rand for and against? The best way to get to the bottom of it is to take a look at how she developed the superhero of her novel, Atlas Shrugged, John Galt. Back in the late 1920s, as Ayn Rand was working out her philosophy, she became enthralled by a real-life American serial killer, William Edward Hickman, whose gruesome, sadistic dismemberment of 12-year-old girl named Marion Parker in 1927 shocked the nation. Rand filled her early notebooks with worshipful praise of Hickman. According to biographer Jennifer Burns, author of Goddess of the Market, Rand was so smitten by Hickman that she modeled her first literary creation -- Danny Renahan, the protagonist of her unfinished first novel, The Little Street -- on him.

What did Rand admire so much about Hickman? His sociopathic qualities: "Other people do not exist for him, and he does not see why they should," she wrote, gushing that Hickman had "no regard whatsoever for all that society holds sacred, and with a consciousness all his own. He has the true, innate psychology of a Superman. He can never realize and feel 'other people.'"

-

Mark Ames

_______________________

Naglfar

1998

Anselm Kiefer

b. March 8, 1945

Lenin Imports

_______________________

A Preface to Silence:

On the Duty of Vigilant Critique

Norman K. Swazo

janus head

So, we must consider: what is the duty of vigilant critique insofar as it speaks at the juncture of philosophical and political responsibility? It is the duty of speech which delivers into the present its memory, links present and past, and indicts the present after the indictments of the past and the judgments of memory. But one feels compelled to ask: Is this strategy not to be rejected in principle? Is it not to be rejected even with regard to consequences, with regard to a judgment of historical efficacy? Must we forever "cling to our shame" and so hold the future hostage to our ressentiment? To speak the name is to call forth the thing -- to utter the demon’s name is to call forth the demon. Such is the admonition of ancestral tradition. To name is to convey from non-being to being: male dictus, male dictus. . .

Speech, in its essential structure, is apophantic, as Aristotle already pointed out in his On Interpretation. Speech, as Heidegger reminds us in echo of Aristotle, "lets us see," "makes manifest what is being talked about," and thus "makes it accessible to another" (see Being and Time, Ch. II, Section 7B). To name, then, is to call out "into the distance," to call the temporally afar "into nearness." Such calling brings into nearness. To bring into nearness, to "bridge," is not to bring into presence-at-hand, granted. Yet, such calling ever remains an oblique invitation, a bidding to come, such that what is called thereby has bearing, i.e., bears upon us in our presence. In this bearing, a world is borne by the word; thus, the word "gathers a world," unfolds and discloses it in the manner of its bearing. That gathering of world, as a disclosure of a "referential totality," can be a benign gathering. It can also be a gathering of malignity: Some bridges are better left unbuilt. ....(more)

_______________________

An Interview with Robert Kelly

Conjunctions:13, Spring 1989

_______________________

An American Abroad: England in the Mid-Sixties

Tom Clark interviewed by Jeffrey Side, September 2009

Vanitas

_______________________

Anselm Kiefer

_______________________

"the poetry of self-promotion"

Joshua Corey

To succeed as a writer—and I define "success" quite simply as being able to continue in one's work—you not only have to "create the taste by which [one] is to be relished" (Wm. Wordsworth) but you have to create relationships and infrastructure and paths of distribution. Start a press, start a blog, form a reading group, start a reading series. If you can synergize with institutions, do so, but don't sit around waiting for them to recognize or rescue you: they can offer you everything but initiative. This is the best path I've found for resisting the otherwise inevitable alienation from one's own creative labor that comes from permitting oneself and one's work to be processed by workshops and editors and tenure committees.

"Self-promotion" is a crass phrase, or rather a class phrase: I was raised to be squeamish about such things because I grew up in the middle-class "meritocracy" with the assumption that the privileges I was born into would be continued automatically, provided that I did well enough on standardized tests to go to the "right" schools. Needless to say, neither I nor many other people from such circumstances can afford to go on thinking this way. This is not something to be regretted. At the same time, I'm not advocating that writers shrug their shoulders and just convert to the cult of self-commodification. I'm not quite sure that the phrase "the poetry of self-promotion" will ever enable me to see self-promotion itself as poetic. (Though I can't help but be skeptical about the corollary saying of Robert Graves', "There's no money in poetry but there's no poetry in money either.") But I do think that what poetry you promote and how you promote it matters, and that ultimately we can't and shouldn't separate a poem from the context of its production and means distribution....(more)

The Blenheim Oaks

photos and text

Simon Norfolk

Visura Magazine 8

_______________________

"The Battle of Blenheim"

Robert Southey

(....)

"They said it was a shocking sight

After the field was won;

For many thousand bodies here

Lay rotting in the sun;

But things like that, you know, must be

After a famous victory.

"Great praise the Duke of Marlbro' won,

And our good Prince Eugene."

"Why, 'twas a very wicked thing!"

Said little Wilhelmine.

"Nay ... nay ... my little girl," quoth he,

"It was a famous victory."

"And everybody praised the Duke

Who this great fight did win."

"But what good came of it at last?"

Quoth little Peterkin.

"Why, that I cannot tell," said he,

"But 'twas a famous victory."

_______________________

Hieronymus Bosch

_______________________

Cultural Cognition of Scientific Consensus

Dan M. Kahan, Hank Jenkins-Smith, Donald Braman

Abstract:

Why do members of the public disagree - sharply and persistently - about facts on which expert scientists largely agree? We designed a study to test a distinctive explanation: the cultural cognition of scientific consensus. The “cultural cognition of risk” refers to the tendency of individuals to form risk perceptions that are congenial to their values. The study presents both correlational and experimental evidence confirming that cultural cognition shapes individuals’ beliefs about the existence of scientific consensus, and the process by which they form such beliefs, relating to climate change, the disposal of nuclear wastes, and the effect of permitting concealed possession of handguns. The implications of this dynamic for science communication and public policy-making are discussed.

Social Science Research Network (SSRN)

_______________________

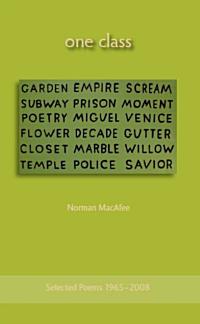

one class

selected poems, 1965–2008

Norman MacAfee

Harbor Mountain Press

from

Italy ’76

Norman MacAfee

one class

—for Pasolini, Visconti, Rossellini

dead with a year of each other

(Poets and filmmakers in an apartment in

a working-class Milan neighborhood)

The human individual in his living room

is only half that story, the other being

the world of torture, the over-made-up

cheering sections for the two, while, at

the color slide flooding in the linedrawing

of a window penciled

earlier from it on the white wall,

I answered “reality,” then “part of it,”

for dense plethoras of reality love

thirty-three-year-old child prodigies,

love the true center of story telling:

unscriving mouths from which comes this

indubitable child of me and the world

.....................................................

Poems

Pier Paolo Pasolini

selected and translated by Norman MacAfee

Norman MacAfee's web site

The Coming of Fascism to America

Norman MacAfee

jacket

I Am Astro Place

Norman MacAfee

jacket

_______________________

'Cowper's Poetical Works'

Goat skin and red maple wood

Binder unknown, 1874

Beautiful Bookbinding

Bibliodyssey

_______________________

The Social Contract of Scholarly Publishing

Dan Cohen

The social contract of the book is profoundly entrenched and powerful—almost mythological—especially in the humanities. As John Updike put it in his diatribe against the digital (and most humanities scholars and tenure committees would still agree), “The printed, bound and paid-for book was—still is, for the moment—more exacting, more demanding, of its producer and consumer both. It is the site of an encounter, in silence, of two minds, one following in the other’s steps but invited to imagine, to argue, to concur on a level of reflection beyond that of personal encounter, with all its merely social conventions, its merciful padding of blather and mutual forgiveness.”

As academic projects have experimented with the web over the past two decades we have seen intense thinking about the supply side. Robust academic work has been reenvisioned in many ways: as topical portals, interactive maps, deep textual databases, new kinds of presses, primary source collections, and even software. Most of these projects strive to reproduce the magic of the traditional social contract of the book, even as they experiment with form.

The demand side, however, has languished. Far fewer efforts have been made to influence the mental state of the scholarly audience. The unspoken assumption is that the reader is more or less unchangeable in this respect, only able to respond to, and validate, works that have the traditional marks of the social contract: having survived a strong filtering process, near-perfect copyediting, the imprimatur of a press.(....)

Can we change the views of humanities scholars so that they may accept, as some legal scholars already do, the great blog post as being as influential as the great law review article? Can we get humanities faculty, as many tenured economists already do, to publish more in open access journals? Can we accomplish the humanities equivalent of FiveThirtyEight.com, which provides as good, if not better, in-depth political analysis than most newspapers, earning the grudging respect of journalists and political theorists? Can we get our colleagues to recognize outstanding academic work wherever and however it is published?...(more)

_______________________

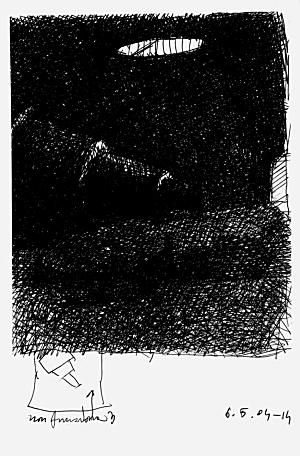

Scolari’s Shadows

Lebbeus Woods

Massimo Scolari

_______________________

Time Capsule: Distended Triptych

Robert Gibbons

II.

Goya’s Trees

Tree limb split in the storm last week made things more worrisome, when

placed in perspective. Goya resurrected trees as scenic ploys, backdrops for

lost body parts, stump altars to mutilated corpses, or war-torn camouflage for

stripping the dead of all belongings. My split tree limb in the backyard

caused by the storm last week bore strange fruit imagined in Spain, Black

Forest, Alabama, Nam, Afghanistan.

...(more)

_______________________

Frank Paynter has a new blog - Class War

_______________________

LinkMachineGo celebrates ten years.

_______________________

Bertha, The Child-Flower:

A Raymond Roussel Illustration Contest

A Journey Round My Skull

including the text

Bertha, The Child-Flower

by Raymond Roussel

Translated by Mary Ann Caws

Surrealist Painters and Poets

_______________________

The Garden of Earthly Delights

Detail

Hieronymus Bosch

ca.1450-1516

_______________________

from

Pictures from Bosch

Norman MacAfee

one class

Pity abets the crimes. Perhaps even

resistance is hypocritical. Money is

always only paid out to silence

witnesses to murder. Exploration is

most rewarded by imprisonment. Part

fear and guilt, but only small parts, mostly

disbelief, keep the phone ringing and me

not answering. The painter cries, “Don’t you

see beneath the surface? Are you blind?”

World-madness starts as innocent child’s play.

(....)

_______________________

Victory

by Pier Paolo Pasolini

(March 5, 1922 – November 2, 1975)

translated by Norman MacAfee with Luciano Martinengo

Where are the weapons?

I have only those of my reason

and in my violence there is no place

for even the trace of an act that is not

intellectual. Is it laughable

if, suggested by my dream on this

gray morning, which the dead can see

and other dead too will see but for us

is just another morning,

(....)

Good. I wake up and—for the first time

in my life—I want to take up arms.

Absurd to say it in poetry

—and to four friends from Rome, two from Parma

who will understand me in this nostalgia

ideally translated from the German, in this archeological

calm, which contemplates a sunny, depopulated

Italy, home of barbaric Partisans who descend

the Alps and Apennines, down the ancient roads...

...(more)

_______________________

former teahouse

Kabul

Forensic Traces of War

Simon Norfolk

lens culture

_______________________

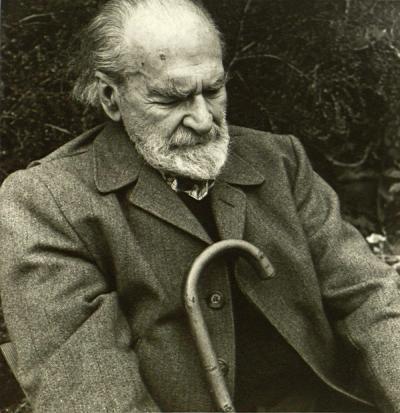

Introduction

Hayden Carruth

Existentialism entered the American consciousness like an elephant entering a dark room: there was a good deal of breakage and the people inside naturally mistook the nature of the intrusion. What would it be? An engine of destruction perhaps, a tank left over from the war? After a while the lights were turned on and it was seen to be "only" an elephant; everyone laughed and said that a circus must be passing through town. But no, soon they found the elephant was here to stay; and then, looking closer, they saw that although he was indeed a newcomer, an odd-looking one at that, he was not a stranger: they had known him all along. ...........

Nausea

Jean-Paul Sartre Translated from the French by Lloyd Alexander. Introduction by Hayden Carruth aaaarg free reg. req.

As for the square at Meknes, where I used to go every day, it's even simpler: I do not see it at all any more. All that remains is the vague feeling that it was charming, and these five words are indivisibly bound together: a charming square at Meknes. Undoubtedly, if I close my eyes or stare vaguely at the ceiling I can re-create the scene: a tree in the distance, a short dingy figure run towards me. But I am inventing all this to make out a case. That Moroccan was big and weather-beaten, besides, I only saw him after he had touched me. So I still know he was big and weather-beaten: certain details, somewhat curtailed, live in my memory. But I don't see anything any more: I can search the past in vain, I can only find these scraps of images and I am not sure what they represent, whether they are memories or just fiction.

There are many cases where even these scraps have disappeared: nothing is left but words: I could still tell stories, tell them too well (as far as anecdotes are concerned, I can stand up to anyone except ship's officers and professional people) but these are only the skeletons. There's the story of a person who does this, does that, but it isn't I, I have nothing in common with him. He travels through countries I know no more about than if I had never been there. Sometimes, in my story, it happens that I pronounce these fine names you read in atlases, Aranjuez or Canterbury. New images are born in me, images such as people create from books who have never travelled. My words are dreams, that is all.

For a hundred dead stories there still remain one or two living ones. I evoke these with caution, occasionally, not too often, for fear of wearing them out, I fish one out, again I see the scenery, the characters, the attitudes. I stop suddenly: there is a flaw, I have seen a word pierce through the web of sensations. I suppose that this word will soon take the place of several images I love. I must stop quickly and think of something else; I don't want to tire my memories. In vain; the next time I evoke them a good part will be congealed.

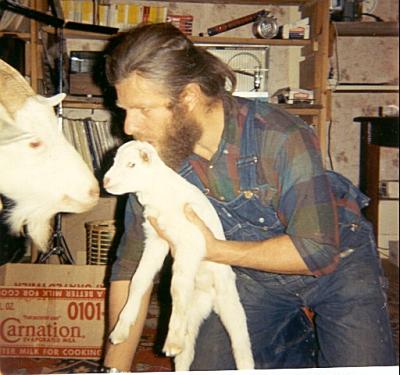

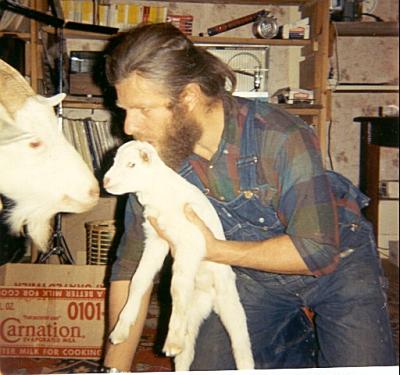

Peter Orlovsky, mama goat ("Shiva") and baby

Cherry Valley, New York farmhouse

February l970

Ginsberg & Beat Fellows: Photographs 1969 - 1997

Gordon Ball

_______________________

Moon Over Gringo Gulch

In God we can only trust, but in hashish rests assurance

Joe Bageant

An American never quite gets over the sight of half a dozen retired middle class seventy year olds in puffy white velcro strap tennis shoes, nonchalantly passing a fat bomber. ...(more)

_______________________

Depression’s Upside

Jonah Lehrer

"Pain or suffering of any kind," he wrote, "if long continued, causes depression and lessens the power of action, yet it is well adapted to make a creature guard itself against any great or sudden evil." And so sorrow was explained away, because pleasure was not enough. Sometimes, Darwin wrote, it is the sadness that informs as it "leads an animal to pursue that course of action which is most beneficial." The darkness was a kind of light....(more)

Jonah Lehrer blogs at The Frontal Cortex.....................................................

Wonderful behavioral science writer Jonah Lehrer (Proust Was a Neuroscientist) writes for the New York Times Magazine on the idea that depression may be adaptive. It is not a new idea; I have followed the intriguing literature about possible evolutionary reasons for the persistence of depression ever since I was a psychiatric resident troubled by how readily we in the field want to obliterate any signs of the condition whenever our patients present with it. Some theories have focused on the advantages of resource preservation, given the social isolation, decreased motivation and lessened self-indulgence the depressed person displays. It has also been suggested that the depressive alteration in cognition, in the direction of impaired self-esteem, decreased sense of efficacy and control over one’s circumstances, and pessimism , may actually be more realistic, at least in some circulstances, than the rose-colored glasses with which we usually walk around.

Eliot Gelwan

Follow Me Here

_______________________

Frozen History

Josef Hoflehner

1 2

_______________________

"No bird has the heart to sing in a thicket of questions"

- René Char

The Aesthetics Of SilenceSusan Sontag

The exemplary modern artist's choice of silence isn't often carried to this point of final simplification, so that he becomes literally silent. More typically, he continues speaking, but in a manner that his audience can't hear. Most valuable art in our time has been experienced by audiences as a move into silence (or unintelligibility or invisibility or inaudibility); a dismantling of the artist's competence, his responsible sense of vocation — and therefore as an aggression against them.

Modern art's chronic habit of displeasing, provoking, or frustrating its audience can be regarded as a limited, vicarious participation in the ideal of silence which has been elevated as a prime standard of seriousness in the contemporary scene.

But it is also a contradictory form of participation in the ideal of silence. It's contradictory not only because the artist still continues making works of art, but also because the isolation of the work from its audience never lasts. With the passage of time and the intervention of newer, more difficult works, the artist's transgression becomes ingratiating, eventually legitimate. Goethe accused Kleist of having written his plays for an "invisible theatre." But in time the invisible theatre becomes "visible" The ugly and discordant and senseless become "beautiful." The history of art is a sequence of successful transgressions. (....)

The art of our time is noisy with appeals for silence.

A coquettish, even cheerful nihilism. One recognizes the imperative of silence, but goes on speaking anyway. Discovering that one has nothing to say, one seeks a way to say that....(more)

Aspen no. 5+6

The Minimalism issue _______________________

Fishing Boat

Iceland

Josef Hoflehner

_______________________

After all the pretty contrast of life and death

Proves that these opposite things partake of one,

At least that was the theory, when bishops' books

Resolved the world. We cannot go back to that.

The squirming facts exceed the squamous mind,

If one may say so . And yet relation appears,

A small relation expanding like the shade

Of a cloud on sand, a shape on the side of a hill.

- Wallace Stevens, from Connoisseur of Chaos

_______________________

Private Property, Austria

Josef Hoflehner

_______________________

"what is a body that can be a body not constantly exposed" :

A Celebration of the work and life of kari edwards

Xpoetics

.....................................................

Bharat jiva

kari edwards

litmus press

no gender

Reflections on the Life & Work of kari edwards

edited by Julian T. Brolaski, erica kaufman,

and E. Tracy Grinnell

litmus press

_______________________

Jim Carroll

a memoir by Tom Clark

Longhouse

"A poet departs, too soon, and there is a void that will not be filled. From somewhere deep and old the tears well up in the dark night. When I met Jim in 1967 he was seventeen. He had been leading a triple life: high school All-American basketball star, heroin addict/ street hustler, poet."

_______________________

Imagination as Plagiarism

Raymond Federman

aaaarg - free reg. req.

_______________________

The Future as Sci Fi: A New Cold War

Slavoj Zizek

... an extraordinary social and psychological change is taking place right in front of our eyes – the impossible is becoming possible. An event first experienced as impossible but not real (the prospect of a forthcoming catastrophe which, however probable we know it is, we do not believe it will effectively occur and thus dismiss it as impossible) becomes real but no longer impossible (once the catastrophe occurs, it is “renormalized,” perceived as part of the normal run of things, as always-already having been possible). The gap which makes these paradoxes possible is the one between knowledge and belief: we know the (ecological) catastrophe is possible, probable even, yet we do not believe it will really happen....(more)

_______________________

Of Nantucket in a Gravid Light

Clayton Eshleman

action yes

A silence older than being.

A sound that has nothing to do with noise.

Anaximander’s “apeiron”

Indeterminate potentiality.

Orison pulsing in all beings and events.

I am the lavender word, son of the arsinother,

daughter of the basilosaur.

I teach that each word is shredded with carnifex,

spongy, a capstone capping sunyata.

To play, as cello, the Grunewald Altarpiece.

To draw out its mole tones, its Sadean larvae.

...(more)

ACTION YES winter 2010

_______________________

Water Walk

Japan

Josef Hoflehner

_______________________

Night Does Not Fall

Nikos Violaris

Translated from GreekGreek by Peter Constantine

words without borders

Night

does not fall

nor does it come

Night slowly

breaks within me

Because I am a lake

ever faceless

and I am mud

in the dreams of secret

stars

So night

no longer falls

nor does it come

night takes leave

like a good

guest

Imported landscape

Pétur Thomsen

_______________________

Johann Sebastian Summoned to the Royal Court

Nathaniel Tarn

Drunken Boat Winter 2007-2008

A dream while sitting here, obedient.

To go back to our long white houses,

furthest away from this white palace,

the wicker furniture, also all white,

[as white as foam dreamed on the lips

of famed thalassa never seen or heard

contrasting with l’azur, l’azur, l’azur,]

in which it would be fine to loll, to

pause for longer times than the time

granted, to play what we desired to

play for once, instead of duty calling

evermore to play the work of friends,

always more friends. Not that there’s

no desire to play the friends, but it is

hard to read two scores without four

eyes. And then to find ourselves again

as we’d once been in morning sunlight

ages ago after the second visitation,

when terror waned, disease retreated,

when all of poverty forgave the rich,

and every universal garden flourished

in all its blooms together, all birdlings

sang amalgams of single melodies to

infinitely variable musics -- this was,

it seemed to us, the dream of paradise

[what if illusion, ah, pitiless illusion!]

which kept us deaf to any summons,

before the ruling classes lost their minds,

their properties; before we served only

burrocrassies as spare-time artists, mere

intellectuals, performing elephants and

fleas. The life which is, which only is,

which never changes into what is not, the

key to all these longings, the single defi-

nition of what we must perform. And then

our counterpoint, our what is left of any-

thing, the sum of all and any definition,

the means whereby a god [specified as

“God”] bleeds out its life into the universe.

Selected poems: 1950-2000

Nathaniel Tarn google books

Ins and Outs of the Forest Rivers

Nathaniel Tarn

google books

The embattled lyric:

essays and conversations in poetics and anthropology

Nathaniel Tarn

google books

Nathaniel Tarn at PennSound

from

Chapbook: Up by the Maritime Museum

Nathaniel Tarn and

Nancy Victoria David

big bridge

TARN : a tribute

Robert Kelly

Golden Handcuffs #11

Steady Turbulence

Brenda Hillman reviews Selected Poems 1950-2000 by Nathaniel Tarn

jacket

.....................................................

Nathaniel Tarn

in conversation with Daniel Bouchard

jacket

There’s a dichotomy “Home” and “Away. ” The older I get, the more I love “Home” and the more “Home” may be replacing “Exile, ” but, for most of my life, I always wanted to be “Away. ” (And I was fortunate to be able to do it). Coming “Home” was always (often still is) subject to serious post-partum blues. Doubtless, “Away” is the “Home” of “Exile: ” it’s gotta to be something like that. Seeing such monuments, peoples, landscapes or living with them induces anticipation, a sense of importance and significance leading to thoughts of life’s worthwhileness (as opposed to the usual gran nada of the depressive) and the hard-to-define intuition of something worthwhile having been accomplished. This presumably connects with a desire to do something worthwhile in response, as gratitude perhaps, and since what I do is poems… Given the major importance of books, these senses can be linked to the experience in youth of finding a book that you would need in ten years or so and the idea that you had saved the book from barbarism — I later discovered the same feelings in Benjamin’s “Illuminations.”

(....)

Leaving aside the old saw about “things were always better in the old days, ” I truly believe that the conditions of daily life are deliquescing so rapidly that there is a serious question about how writing poems ever gets done. Forget the planet’s condition, the population problem, the never-ending wars; forget the saturated criminality of politics and of corporations and transnationals; forget the ever growing gap between rich and poor and the other ten thousand ills. I’m talking right now about the “blessings” of technology which, while allegedly making everything “easier” for us actually complicate them a zillion miles beyond what they were when I grew up. The brutality of computer codes never destined to be understood by normal users. The fact that the phone industry was fucked up from the moment the answering machine was invented leading, of course, to massive automation. The insanity of our becoming accumulations of passwords, IDs, card numbers which everyone knows you will forget. The lunacy of security-mania complicating the simplest things from mail to travel. The fact that, if you write a letter about a problem, the answer is a call to write another letter about that problem. The incremental growth of requirements in applying for anything; filling out anything; explaining anything: every time a new duty arises, there is one more thing to do, to think about, to try to figure out. The interminability of dealing with hordes, armies, invasions of chores. Even getting to the desk of a morning seems to take more and more time every week.

Beyond this, there is the serious problem of the poetic environment itself, the whole “pobiz” phenomenon. ...(more)

_______________________

Lost Spaces,

Found Gardens

Paul Raphaelson

_______________________

Correspondences in the Air: On The Ecco Anthology of Poetry

Ilya Kaminsky

Octavio Paz once wrote that the modern poet “extracts his visions from within himself.” It is my hope that our comprehensive, aesthetically varied anthology of poetry from around the globe will allow American poets and readers a chance to extract such visions not just from “within themselves” but in conversation with a global poetic tradition. Reading an anthology of world poetry gives one a chance to overhear similarities, or what Anna Akhmatova once called “correspondences in the air”—that is, moments where authors of different geographical and historical circumstances, languages, and traditions, seem to address each other in their works. I hope that these voices brought from outside our borders will allow us, in this somewhat unsettling time in Anglo-American political history, to find the voice within that is strong and compelling, an instrument of poetry which—to rephrase Auden—is our chief means of breaking the bread with the world.

Such “correspondences in the air” abound in this collection ...(more)

words without borders

March 2010: Correspondences in the Air: International Poetry

_______________________

Alice in Wonderland

(1903)

youtube

_______________________

Adolf Hitler & Christian Nationalism: Nazis’ Program of Positive Christianity

Austin Cline

Prayer Warriors and Sarah Palin

Are Organizing Spiritual Warfare to Take Over America

Bill Berkowitz

Glenn Beck, Radical Hit Man for the Tea Partiers

Les Leopold

Glenn Beck's eliminationist attacks on progressives:

How long before someone acts on this violent rhetoric?

David Neiwert

_______________________

Weaponizing Mozart

How Britain is using classical music as a form of social control

Brendan O'Neill

via mosses from an old manse

_______________________

Angelika Sher

_______________________

The perverse core of Christianity

Carl Packman

To get the full sense of what is meant by perversity requires a small deviation into the world of French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan - Žižek's mentor - via Sigmund Freud. Freud characterises the superego as the part of the psychic apparatus which acts as a kind of moral high ground, an overseer of the ego which represents an understanding of reality distinct from the id which can make no coordinated considerations of the world in which the subject finds himself.