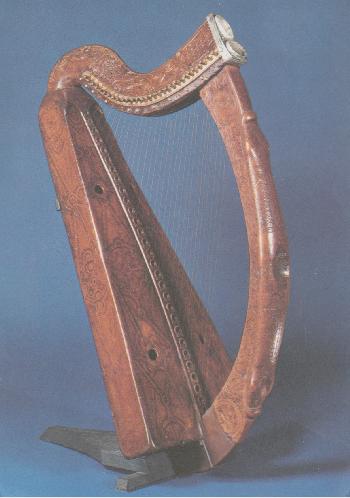

I divide the history of the Irish harp into three periods, which I call pre-Cromwell, post-Cromwell, and modern. This note is about building a musical reproduction of the oldest period, specifically about the 'Trinity College' harp. As a member of the Galpin Society, I got to correspond at length with the curators who re-stabilized the original instrument after it was recovered from a student group who "liberated" it for a few years. Today, plans are available from several harp sources, such as the Folk Harp Journal. There is also far more information now on the Internet that I had access to, for example at http://www.earlygaelicharp.info

Pre-Cromwell, harpers were the soul of Ireland, granted access everywhere as protected guests even in the middle of wars. They travelled between locations by foot, alone, and were the eyes and ears of the country militarily as well as culturally. When Cromwell invaded, he deliberately killed them all off, to shut down Irish communications. After Cromwell's death, efforts were made to revive the playing tradition, but it came back mostly as a drawing room tradition and an occupation for the blind, with larger instruments and a plucking technique, which didn't last very long. This century, the singing tradition was revived, but almost entirely with small plucked Welsh-style ('minstrel') harps - most makers didn't even bother to curve the front post. They were called Irish harps in contrast to the by-then very large Welsh harps (which were enlarged when the English took over their design mid 19th century), and are totally unlike the early Irish harps.

Medieval Irish harps were designed to live outdoors but be played indoors. The instruments had to be totally weatherproof, able to withstand soaking fogs then still perform while being dried out in front of main hall fireplaces. Traditionally, they were only made from woods that grow in bogs - willow and a couple of hardwoods, bog oak apparently being the commonest. Several seed oils were used then to preserve wood and leather, and would have been used on harps. I used urethane, but would use tung oil now.

The body of the Irish harp was hollowed out of a log of willow, so the soundboard grain ran lengthwise. As with all instruments, tradition mixes up with a quest for good sound until the two are almost indistinguishable. The combination of lengthwise grain and metal strings works. Metal strings are acoustically stiffer to their soundboard than the Welsh horsehair. (Gut came later; it was so expensive even as late as 1600 that lute players had to stop playing when they could no longer afford the strings.) A lengthwise grain means that the whole harp body flexes from vibration, the sides moving in as the top is pulled out, so there is quite a different coupling to the air than with the Welsh tradition (which used soundboard grain at right angles to the length of the body, which in turn works with low-impedance strings like horsehair/gut).

I couldn't get good seasoned willow as a log, so selected four pieces cut with grain curving lengthwise (anti-quartercut, if you will) so that, when assembled, the grain orientation is close to what you would get by carving it from a solid log. Other than that, the box construction is standard, with corner fillets to increase the glue area. The only reason the soundboard holes are needed is for stringing, by the way - their effect on the sound is minimal (again, different than with Welsh harps, where the rear slot is essential to keep the sound clean). The width of the soundboard at the bass is a few centimeters less than the original - I couldn't get wood of the required quality quite as large as needed, so made the sides a bit deeper to keep the same inside volume.

The other special thing about old Irish instruments is the curved front post. This is not just for looks - metal strings are much stiffer than horsehair, so when the harp changes size as a result of changes in humidity, the pitch of metal strings will change much more than horsehair strings will. The curved front post, if properly made, has the right elasticity so that, as the wood expands and the string tension goes up, the post will bend so that the bass and treble strings will tend to stay in tune with each other. Otherwise, since the treble strings are under higher tension than the bass ones, the bass strings would rise in pitch more than the treble ones and the instrument would go out of tune with itself faster than it does with the curved post. (The best harpsichords are made with this effect in mind too.) I used birch for the two frame pieces, copied the curves of the Trinity College harp, and did my best to calculate the cross section tapers to get this aspect right.

Everything else about the construction is standard for early stringed instruments, hand done without power tools or machine jigs. The three frame joints are slightly wedged square tenons, oriented so that they are held tight by string tension (although there is glue in them, for ease of assembly). The tuning pegs are iron rod, drilled & filed by hand. There was a small piece of birch wedged into the upper side of each string hole in the soundboard to prevent the string from cutting the willow then buzzing. Turned bushings of hardwood or even ivory were used for this purpose on expensive instruments. When my neice Tanah, a professional harpist, began playing it, she added bushings. (She also refinished the soundboard and decorated it in Celtic style, as you can see.)

The most misunderstood fact about the old Irish playing tradition is this: every authority on early Gaelic that I talked to insisted that there was only one word used at the time for the old technique - the strings were "struck" with long nails. I am assured that there was a perfectly good word for "plucked" at the time, and it was never used for Irish harpers before the Cromwell purge. There is only one way this works anatomically - the finger has to be flicked outward so that the outside of the nail hits the string. That's the only way a nail is strong enough to stand up to it, the way it's arched. This skill was developed solely with the left hand - the right hand was used for damping strings to keep the sound consonant. This is so difficult to do at speed that most people simply refuse to believe it. But, there is good reason to believe that the technique was extraordinarily difficult - the apprenticeship was considered to be ten years, and a player had to start when very young. Several harpers were renowned for their sensitivity of composition, but started playing only when 8-10 years of age, and were held to be audibly handicapped by this misfortune. It didn't take 10 years to learn to be a musician (as it does with several Asian traditions) - it took it solely to develop the required technique. I practised doing it just one finger at a time (as a hand flick, really), and when I got it right, the sound just jumped out of the instrument like a bell. I'm personally convinced that that is the way an Irish harp really worked. Anything else, and it will sound less than it can.

the original (very heavily restored and refinished)

my daughter Margaret learning to play the new one

my neice Tanah bringing its sound to life.