|

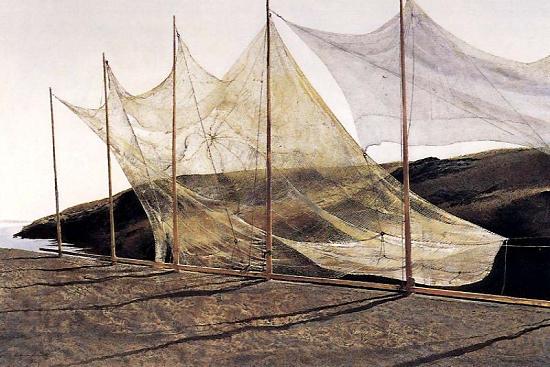

black ice

Anthony Goicolea

_______________________

Bright Moments

Anselm Hollo

when it all makes sense

"deciphers"

a great crystal forest

enchanting

terrifying

because it seems only a sneeze away

from incomprehensible chaos

whose lineaments we are

...(more)

.....................................................

Two from Where if Not Here by Anselm Hollo

Samizdat Magazine

give up your ampersands & lowercase ‘i’s

they still won’t like you

the bosses of official verse culture

(U.S. branch)

but kidding aside

I motored off that map a long time ago

yet have old friends

still happily romping in the English lyric

and Reverdy! dear Reverdy! so much of him rhymes

it must be poésie

ma chérie …

looks at the stacks of books on the floor

gods help us, dear poets

pass the salt pass the mustard

hike the present

or the hypothetically honest horse-drawn past

...(more)

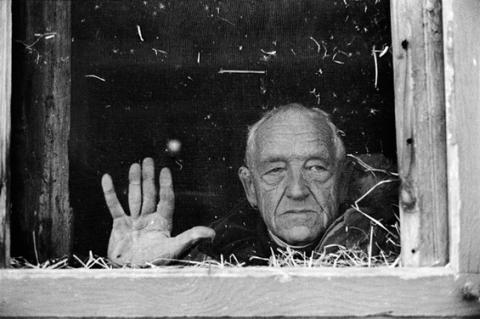

Anselm Hollo

(April 12, 1934 – January 29, 2013)

Anselm Hollo at the Academy of American Poets and PennSound

a joyful summit of old savages

youtube

On a traditionally wet and rainy wednesday night in London, on April 18th 2012, one of the most remarkable poetry readings in recent memory saw Andrei Codrescu, Gunnar Harding, Anselm Hollo and Tom Raworth perform excerpts from their work at the Horse Hospital in Bloomsbury. These four poets have collected shaped more than one generation of their peers and are without doubt four of the greatest living poets in the US and Europe, though their influence stretches far beyond.

Tom Clark remembers(....)Our mutual friend George Mattingly, publisher of much of Anselm's best work, tipped me to the news in the night. I put my head down upon the consolation and prayer beanbag and drifted off into a strange dream reverie of traversing the Laguna Colorada with Anselm and Joe Ceravolo. How strange the disordered mentations of age. The Green Lake Is Awake, and the Red Cats are running upon the distant silent peaks. Muy contento. ...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Open-Sourcing the Global Academy: Aaron Swartz's Legacy

Rebecca Gould

SSRN

(....)“There is no justice in following unjust laws,” wrote the recently-deceased computer programmer and internet activist Aaron Swartz, “It’s time to come into the light and, in the grand tradition of civil disobedience, declare our opposition to this private theft of public culture.” Swartz was twenty-one years old when he wrote these words in his “Guerilla Open Access Manifesto” (2008). Two aspects of Swartz’s manifesto are particularly prescient, when measured against statements made by other visionary open access advocates twice and three times his age. First, there is Swartz’s emphasis on the need to make all scholarship, not just future scholarship but particularly scholarship from past eras, available to anyone with internet access. Second, there is Swartz’s insistence that this scholarship belongs to the entire world. From a very early age, Swartz realized that “books are the cornerstone of our planet’s cultural legacy” and that our survival as a species depended on our making this vast archive accessible to all. Beyond simply speaking on the subject, he created technologies and databases, such as the Open Library, to make such access possible.

(....)

Among Swartz’s many remarkable qualities, the most remarkable from the perspective of this scholar is that, although he defended freedom of inquiry more powerfully and influentially than any scholar in recent memory, Swartz was not himself an academic. He left Stanford because he found the classroom environment unreceptive to his many questions, specifically concerning US militarization in Vietnam. Even as a college dropout, Swartz never stopped defending academic values, in particular freedom of expression. When the academia-oriented magazine Lingua Franca closed down in 2001, Swartz created a special program so that the magazine’s archives could be publicly accessed. He was fifteen, and already passionately dedicated to the promotion of intellectual culture through technology. As the reviews compiled on his website reveal, Swartz’s excitement about books ranging from Malinkowski to Berubé made him a born intellectual. Swartz’s learning provoked Tim Berners-Lee, the renowned inventor of the World Wide Web, to remark of his deceased friend that among the computer programmers he knew “I don’t know if there’s anybody…who has read as many books as Aaron read…he had to read in order to feed that thought process.” This was about Aaron, aged fourteen.

(....)

_______________________

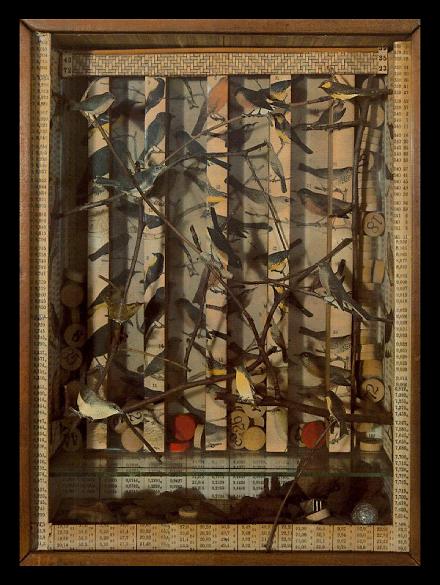

jettisoned

Anthony Goicolea

_______________________

Driftworks (pdf)

Jean-Franēois Lyotard

Translated by Roger McKeon

Is an introduction to these essays really necessary? Don't they introduce themselves? Their presentation can only be a re presentation. I shall place myself behind them, under them, and say: this is what they mean. Thus, my representation will say what they mean and what they actually say will automatically be invalidated, "absented" and considered illusory. By representing them I make them characters in an affair under my control, parts in a text which is mine and not theirs, while the opposite is true: theirs is the only text, and I who would pretend to refer the production of (and the credit for) these essays to my authorship through this representation, am in fact nothing authorized before them, nothing interesting without them. I have no secret to reveal. everything is there, exposed on the surface.

--In that case, why do you preface them?

Not to provide the key and demonstrate their unity, but rather to make them drift a little more than they seem to. What should be suspected is their apparent unity; their collection is interesting insofar as some elements remain uncollected. There is in every text a principle of displaceability (Verschiebbarkeit. said Freud). on account of which the wrillen'work induces other displacements here and there (within author and readers both). and can thus never be but the snapshot of a mobile, itself a referred, secondary unity, under which currents flow in all directions. By collecting texts and making them a book, one encloses them in a protective membrane and they become part of a cell which will defend its unity; my aim, in presenting the essays collected here. is to break up this unity.

What is important in a text is not what it means, but what it does and incites to do. What it does: the charge of affect it contains and transmits. What it incites to do: the metamorphoses of this potential energy into other things-other texts, but also paintings, photographs, film sequences, political actions, decisions, erotic inspirations, acts of insubordination, economic initiatives, etc. These essays conceal nothing, they do or do not contain a certain amount of force with which the reader will or will not do something; their content is not a signification but a potentiality. As a consequence, I am not in a privileged position to detect their intensity in general. I have only read them before the readers.

(....)

_______________________

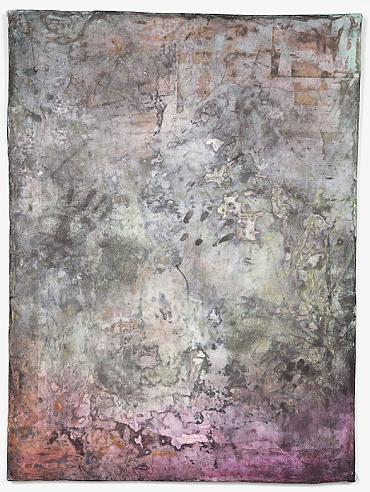

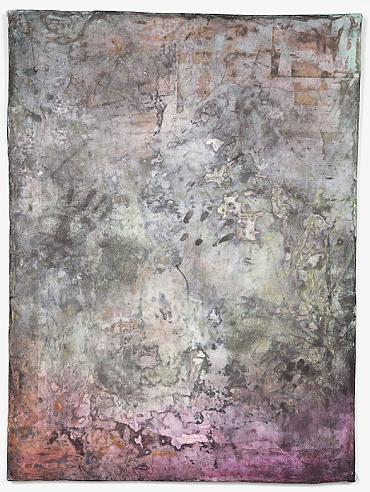

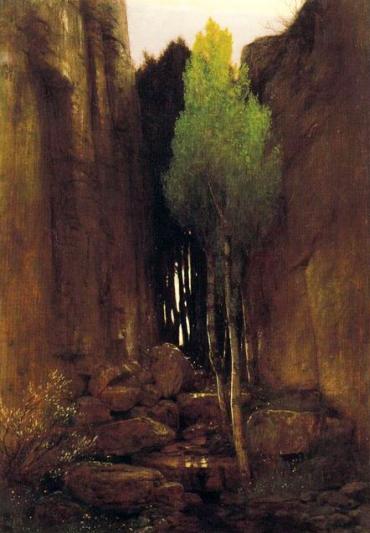

Ear of Dionysius

Jay Heikes

Collection Walker Art Center

Painter Painter

The Walker ... new work by 15 artists from the US and Europe in a focused survey of emergent developments in abstract painting and studio practice.

via Deborah Barlow (Slow Muse)

_______________________

Individual copy

Unpacking Walter Benjamin's iterations

Jacob Edmond

jacket2

(....)“Unpacking My Library” (pdf) finds in the book precisely the problem that Benjamin describes in “The Work of Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproducibility.” There, Benjamin writes: “the technology of reproduction detaches the reproduced object form the sphere of tradition. By replicating the work many times over, it substitutes a mass existence for a unique existence. And in permitting the reproduction to reach the recipient in his or her own situation, it actualizes that which is reproduced.” In “Unpacking My Library,” Benjamin “actualizes” the copy in this way: “For [collector], not only books but also copies of books have their fates. And in this sense, the most important fate of a copy is its encounter with him, with his own collection. I am not exaggerating when I say that to a true collector the acquisition of an old book is its rebirth.”...(more)

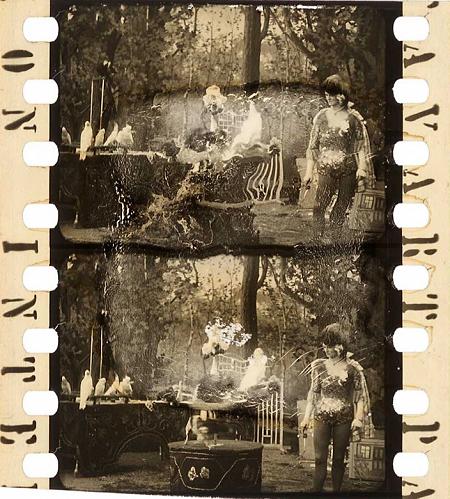

Red Eagle

(di. Lawrence Trimble, Vitagraph, 1911)

Nitrate Nocturne 2

Decomposed nitrate film frame

clippings from the Turconi Collection

50 Watts

_______________________

Globus Hystericus

Timothy Donnelly

paris review

(....)

7.

After the panic grew more or less customary, the pity

dissolved into a mobile fogbank, dense, reducing visibility

from the rooftop observation deck. Mobile in the sense

that it possessed mobility, not in the sense that it actually

moved. Because it didn’t. It just stayed there, reducing

visibility but not in the sense that it simply diminished it

or diminished it partly. Because it didn’t. It pretty much

managed to do away with it altogether, as my photography

will come to show: field after field of untouched white.

After the possibility of change grew funny, threadbare,

too embarrassing to be with, I eased into the knowledge

that you’d never appear at the foot of the bed, the vale

turned into a lifetime’s heap of laundry, and not the gentle

tuffets and streambanks of an afterlife it seems we only

imagined remembering, that watercolor done in greens

and about which I predicted its monotony of fair weather

over time might deaden one all over again, unless being

changed with death means not only changing past change

but past even the wish for it. I worried to aspire towards

that condition might actually dull one’s aptitude for change.

That I would grow to protect what I wished to keep from

change at the cost of perpetuating much that required it.

In this sense I had come to resemble the fogbank, at once

given to motion but no less motionless than its photograph.

The last time I saw myself alive, I drew the curtain back

from the bed, stood by my sleeping body. I felt tenderness

towards it. I knew how long it had waited, and how little

time remained for it to prepare its bundle of grave goods.

When I tried to speak, rather than my voice, my mouth

released the tight, distinctive shriek of an aerophone of clay.

I wanted to stop the shock of that from taking away from

what I felt. I couldn’t quite manage it. Even at this late hour,

even here, the purity of a feeling is ruined by the world.

...(more)

.....................................................

“The Halls of Aspartame”

Timothy Donnelly on writing challenging verse, the cultural faith bred by 30 Rock, and the poet’s need to reach for the eternities

(....)

Do you see your writing as appealing to the establishment or as more experimental?

I’m disinclined to let myself think that my poems might appeal to an “establishment,” because that word suggests to me a league of misguided writers struggling to maintain the status quo. Deep down they’re anxious about how boring their work is, or if they’re plainspoken confessional poets, they probably aren’t really poets at all, but just heartfelt expressers in verse, and they will insist that that’s what poetry is, goddammit — and trying to loosen them up and get them to think otherwise can be about as useless as encouraging a bullfrog to fly. You might get them to leap a little, but that’s about it.

You might then expect the “experimental” team to be a breath of fresh air or a band of emancipatory rebels, like one bright bold Prometheus after another, but in fact they can be just as tediously narrow-minded and border-patrolling as the “establishment.” They can dismiss all conventionally expressive work as passé or else deride it for one cooked-up reason or another, up to and including convoluted ethical imperatives. At some point you grow immune to all the factionalism, or maybe just numb to it. Happily, a lot of the poets who went to college in the late Eighties and Nineties, which is to say my generation, seem to be more able to appreciate work from either side of the divide, and many have been influenced by both, and wouldn’t feel comfortable identifying with either one or the other exclusively.

I’m one of these poets, the synthesizers, although I think my work probably tends to be more traditional in its forms and in the pitch of its rhetoric than most of my immediate peers. Because of this, at least in part, there have been some “establishment” — or let’s just say mainstream — poets who have responded kindly to it. At the same time, my poems tend to draw attention to their constructedness, to make use of citation and collage, to include discursive or overtly philosophical language, and to do their best never to devolve into reportage, or worse, into the glimmery complacent idiom used for poignant reminiscences one might associate with much mainstream poetry....(more)

Timothy Donnelly at the Poetry Foundation and the Academy of American Poets_______________________

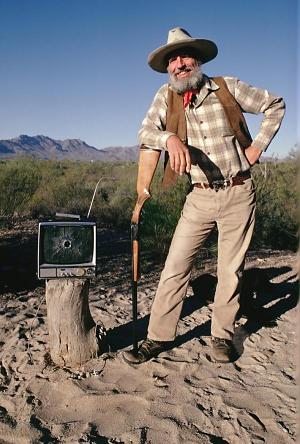

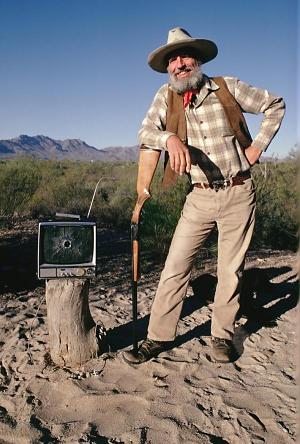

"If I'm serious, and I am, the desert has driven me crazy. Not that I mind"

—

Edward Abbey

Edward Abbey

b. January 29, 1927

photo - Terrence Moore

Excerpt From Desert Solitaire

Edward Abbey

(....)

In the shade of the big trees, whose leaves tinkle musically, like gold foil, above our heads, we eat lunch and fill our bellies with the cool sweet water, and lie on our backs and sleep and dream. A few flies, the fluttering leaves, the trickle of water give a fine edge and scoring to the deep background of - silence? No - of stillness, peace.

I think of music, and of a musical analogy to what seems to me the unique spirit of desert places. Suppose for example that we can find a certain resemblance between the music of Bach and the sea; the music of Debussy and a forest glade; the music of Beethoven and (of course) great mountains; then who has written of the desert?

Mozart? Hardly the outdoor type, that fellow - much too elegant, symmetrical, formally perfect. Vivaldi, Corelli, Monteverdi? - cathedral interiors only - fluid architecture. Jazz? The best of jazz for all its virtues cannot escape the limitations of its origin: it is indoor music, city music, distilled from the melancholy nightclubs and the marijuana smoke of dim, sad, nighttime rooms: a joyless sound, for all its nervous energy.

In the desert I am reminded of something quite different - the bleak, thin-textured work of men like Berg, Schoenberg, Ernst Krenek, Webern and the American, Elliot Carter. Quite by accident, no doubt, although both Schoenberg and Krenek lived part of their lives in the Southwest, their music comes closer than any other I know to representing the apartness, the otherness, the strangeness of the desert. Like certain aspects of this music, the desert is also a-tonal, cruel, clear, inhuman, neither romantic nor classical, motionless and emotionless, at one and the same time - another paradox - both agonized and deeply still.

Like death? Perhaps. And perhaps that is why life nowhere appears so brave, so bright, so full of oracle and miracle as in the desert....(more)

_______________________

Moderne Dresseur (Pathé, 1910)

50 watts

_______________________

To His Own Device

Timothy Donnelly

That figure in the cellarage you hear upsetting boxes

is an antic of the mind, a baroque imp cobbled

up under bulbs whose flickering perplexes night’s

impecunious craftsman, making what he makes

turn out irregular, awry, every effort botched

in its own wrong way. You belong, I said, laid out chalk-

white between a layer of tautened cotton gauze

and another of the selfsame rubbish that you are

wreaking havoc on tonight—and it didn’t disagree.

(....)

Looking out on the water in time we came to see

being itself had made things fall apart this way.

We envied the simplicity implicit in sea-sponges

and similar marine life, their resistance to changes

across millennia we took to be deliberate, an art

practiced untheatrically beneath the water’s surface.

We admired the example the whole sea set, actually.

Maritime pauses flew like gulls in our exchanges.

We wondered that much longer before we had left.

...(more)

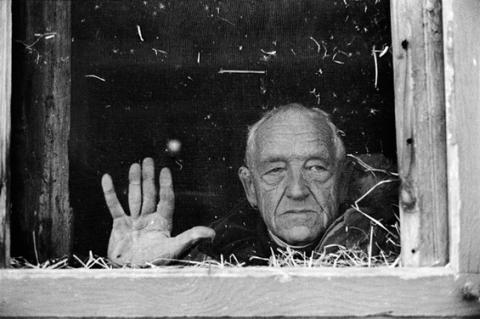

Ayr

1979

Raymond Moore

(1920 – 1987)

Interview with Raymond Moore

(1981)

“Light, from the gentle and persuasive to the harsh and strident, is the magical communicating agent, without it, all in life and the photographic print is black.”

-

Raymond Moore

_______________________

Refrains for Robert Quine

John Taggart

(....)

3

Can we stay in the weave of

that meaning can we/should we attempt to stay to linger

in a pleasure garden everlasting dream of

love tomorrow its unseen/secret structure when our time remains a

bad time and what time wasn’t

bad

wasn’t and isn’t a time of hunger and danger of young men and older men

in tears our time a time

of terror and counterterror can

we/should

we our

time remaining a really bad time a really down and dirty time

of terror what

walls do not fall and who says they have no fear.

...(more)

John Taggart at the Poetry Foundation and PennSound.....................................................

John Taggart FlashPoint Interview

(....)

How do you approach the writing of a new poem, as an inspiration or as a discipline?

JT: It can be both, obviously, but to work with just those two terms I'd probably lean towards ‘discipline' at the beginning - and this is going to jump ahead a bit into one of your other questions, but it's connected - I see it as addressing form, and working with form, and that's the first consideration. And the way I think of that is as a grid. The task is to set it up; then once you're in it, to not so much get out of it, but as you're going along to go beyond it, to go off grid. ‘Grid' is obviously visual, as in many ways, for many people at least, the whole notion of ‘form' is visual. I'm interested. My beginnings tend to be visual, and I hope the ends are not. An example I would give you would be visual, again, say someone like Rothko, who would spend hours just looking at the canvas making preliminary marks indicating his dimensions on the canvas. Okay, now this is very strict, and when you look at things like the paintings in the Rothko Chapel at Houston, he worked on this for a very long time. These are huge paintings, and they vary in the way they are set up, just by inches and fractions of inches, all of which is highly deliberate. The point is what you get in the end are these big, floating blocks that have a life of their own, and you're not thinking ‘grid' at all. But what made those blocks possible is the grid, or grid-like considerations, we'll say. To put it another way, I want the end of the poem to have resonance - literally sound that lingers, whether that is a sound as mood, a sound as a cadence, a rhythm. I want the sense that when you come to the end of the poem, whether you're listening to me read it aloud or you're reading it, that the poem exceeds the last line, the last period, the last page, that there might be a sort of hovering quality.

...(more)

John Taggart

Reading at the Rothko Chapel

October, 2012 video

_______________________

Raymond Moore

_______________________

Content's Dream: Essays, 1975-1984

Charles Bernstei

google books

Writing and Method

(....)

The question is always: what is the meaning of this language practice; what values does it propagate; to what degree does it encourage an understanding, a visibility, of its own values or to what degree does it repress that awareness?

To what degree is it in dialogue with the reader and to what degree does it command or hypnotize the reader? Is its social function liberating or repressive? Such questions of course open up into much larger issues than ones of aesthetics, open the door by which aesthetics and ethics are unified. And so • they pertain to not only the art situation but more generally the language of the job, of the state, of the family, and of the street. And my understanding of these issues coines as much from working as a commercial writer as from reading and writing poetry. Indeed, the fact that the overwhelming majority of steady paid employment for writing involves using the authoritative plain styles, if it is not explicitly advertising; involves writing, that is, filled with preclusions, is a measure of why this is not simply a matter of stylistic chpice but of social governance: we are not free to choose the language of the workplace or of the family we are born into, though we are free, within limits, to rebel against it. Nor am I therefore advocating that expository writing should not be taught; I can think of few more valuable survival skills. "But if one learns to dress as the white man dresses one does not have to think the white man dresses best." And again the danger is that writing is taught in so formal and objectified a way that most people are forever alienated from it as Other. It needs, to use Alan Davies's terms, to be taught as the presentation of a tool, not mystified as a value-free product, in which the value-creating process that led to it is repressed into a norm and the mode itself is impenalized. Coherence cannot be reduced to the product of any given set of tools. This will not necessarily entail that all writing be revolu- tionary in respect to style or even formally self-conscious about it-though that is a valuable course-but rather that styles and modes have social meaning that cannot be escaped and that can and should be understood. _______________________

Raymond Moore

_______________________

The Tyee's Crash Course in Climate Change

The facts, in eight parts. Plus a quiz just to assure you have achieved climate geek status. Prepared by Eric Nadal, a Vancouver based writer and UBC graduate with degrees spanning physics, planetary science, ethics and the philosophy of science. Drawing on his background in both science and philosophy, Eric seeks to equip readers with a fresh and more sharply honed understanding of the problem. Edited by Chris Wood.

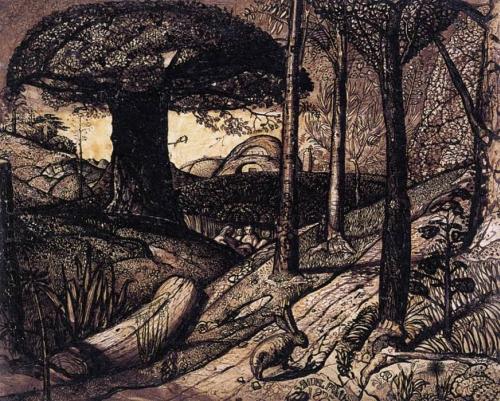

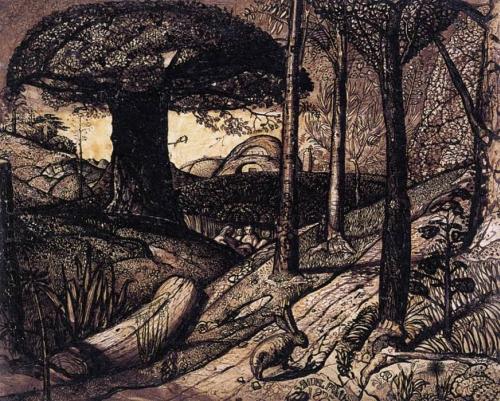

Early Morning

1825

Samuel Palmer

b. Jan. 27, 1805

_______________________

Land Beast

Kate Wyer

There are great kelp bladders, air mouthed into their growth, fed into them. The process of lifting near rootless: sea constant against each hollow knuckle: falling, unfalling.

I have no built-in buoy. I collapse into the undrinkable.

But mostly, I remember the river. My head rooted under that water, pulling against anything that wanted to lift. The plants thin green and mucus-rich in my teeth.

Arms, off. Legs, off. No, that's not true. Just the horn and some skull.

My hard hollow frame for breath collapses under sedation. A matter of giving away, of no longer resisting. Heaviness from needled sleep.

I would like to continue.

...(more)

The Collagist Issue Forty-TwoDzanc Books

_______________________

Kirsty Hooper’s ‘Writing Galicia into the World’ as Co-Savoir

Erķn Moure

In post 13, when I spoke of Blanchot and translation as a step outside time, I briefly mentioned UK critic and Galician literary scholar Kirsty Hooper. Her landmark book Writing Galicia into the World is also a step outside time, one important to translation in a critical sense and in a wider optic. Its mission is other, but it opens up the stakes of translation itself, in a way that is co-incident with, and that has learned from, ideas of writers such as Édouard Glissant and Gilles Deleuze. Her work allows us to look anew at what it means to cross the borders of language, and better understand literature’s role in this crossing.

...(more)

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Winter

H. L. Hix

from "The God of Window Screens and Honeysuckle"

Stubble rows, four matte, four shiny in morning sun,

show the combine’s direction. What can be preserved

must be preserved as some self other than its own.

Bent cattails mimic stubble in the frozen pond.

Suet nearly gone, chickadees cling upside down

to the feeder. Above it, a hedgeapple wedged

between branches since fall. Past that, changing direction

at once, fast as mackerel, a thousand blackbirds.

Skaters on a pond, we fall into what we know,

drown in disorienting light before we freeze.

In angled afternoon sun, the fence’s shadow

caresses the snow’s contours like tight-fitting clothes.

Even when grass greens to re-enact spring, the snow

will linger, longest in the shadows of houses.

H. L. Hix at the Poetry Foundation and the PIP

H. L. Hix - four poems

drunken boat

_______________________

Meet the Flannery O’Connor of the Internet age

Maud Newton on Ellen Ullman

(....)

Ullman’s first book, “Close to the Machine,” is a smart, appealingly unpretentious hybrid of memoir and cultural criticism that achieved what until its appearance in 1997 seemed impossible: It made computer programming human. Technology as she portrays it is an inevitable outgrowth of our imagination and drive, almost as inescapable as the longing for love and for sex, but she’s no techno-triumphalist. Ullman exposes the ways the world we’ve created reflects our own shortcomings back at us and isolates us from each other. The computer, she contends, “is not like us. It is a projection of a very slim part of ourselves; that portion devoted to logic, order, rule and clarity.” No matter how good the programming, eventually “the irregularities of human thinking start to emerge” in the code.

(....)

Yet people are hung up on the absence of computers. “I find it funny when someone says that the narrator’s search for the birth mother would have taken a few minutes if only he’d had the Internet,” Ullman tells me. “I think that focusing all experiences through the lens of the Internet is an example of not being able to see history through the eyes of others, to be so enamored of one’s present time that one cannot see that the world was once elsewise and was not about you. Has Google appropriated the word ‘search’? If so, I find it sad. Search is a deep human yearning, an ancient trope in the recorded history of human life.”

She is at work on another book about technology, a subject that still fascinates her, “but thousands of years of history came before a computer ever existed.” So “By Blood” was a way of “temporarily breaking a link to the computing era, which was becoming rather smothering, a forced way to view the world.” She wanted to explore the idea that the way we live now is “in no way inevitable.” Reading Tony Judt’s “Postwar” convinced her that “small changes could have resulted in a completely different view of the world.”

What makes "By Blood" and all her writing so sharp, so insightful and so timeless is the obsessive way Ullman visits and revisits the intersection between possibility and reality - "what you have inherited and what you can jettison, what you can possibly escape, and what you cannot" - you in the individual sense, and in the universal. From every vantage point accessible to her she interrogates "the dreadful question of who we become."

...(more)

_______________________

Samuel Palmer

Ulysses

1947

Robert Motherwell

b. Jan. 24, 1915

_______________________

Louise Glück’s Metamorphoses

David Orr

(....)... the structures of poems are ways of organizing (that is, controlling) experience. But it’s one thing to want to control the way a poem looks, quite another to have dreamed up the beginning of “The Drowned Children,” which appeared in Glück’s collection “Descending Figure” (1980):

You see, they have no judgment.

So it is natural that they should drown,

first the ice taking them in

and then, all winter, their wool scarves

floating behind them as they sink

until at last they are quiet.

And the pond lifts them in its manifold dark arms.

“So it is natural”: obviously, it isn’t natural at all for children to drown — or to the extent it is natural, it should make us wonder what we mean by the word. Which is Glück’s point. The impersonal forces that really do control our lives (time, space, our own unconscious desires) operate in a way that transcends the day-to-day demands of car payments and deadlines. They’re not so much irrational as unrational, and they are implacable. That truth can be frightening, but as Glück’s first few books demonstrate, it can also be unsettlingly beautiful, in the way that a shark can be beautiful, or a tidal wave.

...(more)

_______________________

A Marzipan Factory

Grzegorz Wróblewski

amazon

Grzegorz Wroblewski’s poems performed in English, to music

Marcus Slease

_______________________

The State of the Art III: Facebook (and 500px and Flickr) as a Window Into Social Media

Timothy Burke

Easily Distracted

Why is Facebook such a repeatedly bad actor in its relationship to its users, constantly testing and probing for ways to quietly or secretly breach the privacy constraints that most of its users expect and demand, strategems to invade their carefully maintained social networks? Because it has to. That’s Facebook’s version of the Red Queen’s race, its bargain with investment capital. Facebook will keep coming back and back again with various schemes and interface trickery because if it stops, it will be the LiveJournal or BBS of 2020, a trivia answer and nostalgic memory.

That is not the inevitable fate of all social media. It is a distinctive consequence of the intersection of massive slops of surplus investment capital looking desperately for somewhere to come to rest; the character of Facebook’s niche in the ecology of social media; and the path-dependent evolution of Facebook’s interface....(more)

_______________________

Small Ads

Dushko Petrovich

n+1

So there you are, on a Sunday with your coffee reading Harper’s, or Bookforum, or the New Yorker, and after a series of carefully orchestrated, full-page ads that either flatter your interests (Why yes, I am curious about Bolańo!) or accede quietly to their evolution (Enough with the ˇi˛ek, already!)—you come across something altogether different. Their size congratulates your sense of discovery. At first you think these little rectangles are amusing because they offer monogrammed sweaters and self-publishing opportunities—things that are undoubtedly funny, in a sad, Skymall sort of way. But sometimes the funny sadness goes deeper than that, like the sadness of “unique diamond fish jewelry” for $15,000. And then sometimes you are plunged so deep into these ads, you wish there was a German word, or school of social thought, that could sufficiently describe the experience.

...(more)

_______________________

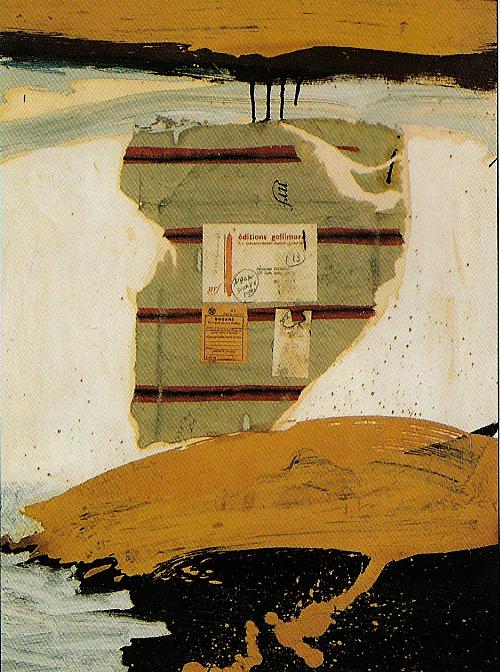

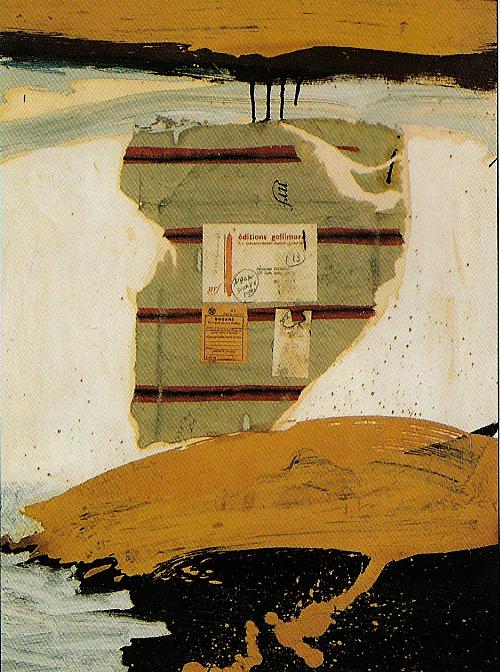

N.R.F. Collage No.2

Robert Motherwell

1960

_______________________

She’s just not that into you

Nina Power on Tiqqun's Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl

Radical Philosophy

How best to describe the colonization of the body at this particular juncture of capitalist life? Much recent theorizing has focused on a kind of war of affects where depression, euphoria and other states of being are read not merely as signs or symptoms, but as directly produced by (and productive of) particular economic relations. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi’s notion of ‘semio-capitalism’ has attempted to track the implications of cyberspace and cybertime for the increasingly depressed mind and body of the contemporary subject. Herve Juvin in the recent The Coming of the Body (reviewed in RP 165, January/February 2011) has similarly attempted to describe what it means for contemporary life when the body has become the ‘bearer’ of all meaning, where every aspect of existence is exchangeable and where nothing is hidden or hideable. While the trajectory of this kind of analysis is not exactly new, even where it occasionally remembers the vast feminist literature on embodiment, affect and labour from the 1960s onwards, there is something novel about the peculiar combination of consumerism, despair, visibility and immaturity that characterizes postwar life in its later stages. It is this ‘new physiognomy of Capital’, where ‘the generalized credit that rules every exchange … strikes within the image of its uniform emptiness the “heart of darkness” of every “personality” and every “character”‘ that Tiqqun address in this short, wilfully fragmentary text first published in France in 1999. The question of gender is raised here, there and everywhere – from the title of the book, to the extracts from magazines marketed to women that Tiqqun scatter throughout the text, to something much more nebulous and disturbing at the heart of their endeavour.

Theory of the Young-Girl is a text that both parodies and mirrors the misogyny that resonates at the heart of a culture that celebrates youth and beauty above all else while simultaneously denigrating the bearers – young women, overwhelmingly – of these purportedly desirable characteristics. The translator of the text, poet Ariana Reines, has written of the visceral reaction the task engendered. The translation, she writes in the online magazine Triple Canopy, ‘gave me migraines, made me puke; I couldn’t sleep at night, regressed into totally out-of-character sexual behaviour’. It is indeed a book that disturbs in its relentless depiction of the fully weaponized, consumerist body of a world in which ‘[although everyone senses that their existence has become a battleground upon which neuroses, phobias, somatizations, depression, and anxiety each sound a retreat, nobody has yet really grasped what is happening or what is at stake.’ The language of colonization, immunization, meat and fluids seeps through the abstract framework of image-analysis, economic structure and ruminations on modernity: ‘the Young-Girl doesn’t kiss you, she drools over you through her teeth. Materialism of secretion.’ If parts of the text read like a theoretically inflected revenge manual for male nerds, one assumes that this effect is – on one level – intentional. The quotation from Hamlet that appears at the beginning of the text, ‘I did love you once’, hints at past betrayals, as does the claim that ‘the “male sex” becomes both the victim and the object of its own alienated desire.’ But who is this ‘male sex’ if everyone is required to permanently ‘self-valorise’, that is to say, to be a Young-Girl? What is left of the body, love, personality when all life resembles a cross between a spreadsheet and a horoscope? ‘Unhappiness makes people consume’ reads one aphoristic statement, and yet unhappiness appears to be all there is, even as everything shrieks of fulfilment and perkiness.

...(more)

.....................................................

Raw Materials for a Theory of the "Young-Girl"

Tiqqun

_______________________

photo - mw

_______________________

Tyee Launches Crash Course in Climate Change

Cut through the smoke, learn the facts, win debates. In eight easy lessons starting today.

Light and Shadow

Y. Ernest Satow

Gallery 916via

_______________________

From The Summits Of Empire

The Auden brothers and the twilight of the Empire

Deborah Baker

Caravan

(....)BY THE END OF THE 1920S, two decades of tragedy had complicated the triumphal myth upon which the British Empire once stood. In 1912, Roald Amundsen bested Royal Navy officer Robert Falcon Scott in the race to the South Pole; on his return leg, Scott froze to death with his team on the Ross Ice Shelf. A year later, Lytton Strachey eviscerated the moral pretensions of the Age of Empire with his satirical take on its heroes in Eminent Victorians. By 1918, an entire generation of men lay martyred and immortalised beneath the mud of Flanders fields. The jockeying for colonial possessions among the civilised nations of the West, had led directly to the savagery of the trenches of the Somme and Ypres, and to the extended massacre at Gallipoli. By the time Robert Graves’ war memoir Goodbye to All That was published in 1929, the extent of the First World War’s senseless slaughter—and the British establishment’s blundering complicity in it—was clear. For a period, John Auden’s generation seemed baffled not only by having been born too late for the Great War, but also by a vague call for martyrdom or heroic action of some sort.

If mountaineering represented one sort of response to this call, literature, in its own way, was another. During the 1930s, as many reputations were being made in English letters as in the Himalayas, and the incidence of sibling rivalry across these two domains was remarkable. The novelist Graham Greene invariably compared his early mixed literary successes with the accomplishments of his dashing older brother, Raymond, a doctor who had joined Shipton on both his successful Kamet climb and the failed 1933 attempt on Everest. Auden’s younger brother, Wystan Hugh (WH) Auden, and Michael Spender’s younger brother, the poet Stephen, had even been part of the same left-leaning cohort at Oxford, together with the writers Christopher Isherwood, Louis MacNeice and Cecil Day Lewis.

...(more)

_______________________

Reflections on Mortality From a Land of Ice and Snow

DJ Spooky

(....)

It’s a paradox of time and space to think that the ice can actually contain fragments of volcanic activity from millions of years ago. There is something eerily disquieting about a remote and deeply ancient place where humanity isn’t capable of enduring long. I was thinking about all of this and the idea that music can reframe the climate change “debate” (most environmental scientists concur: climate change is happening) in a way that wouldn’t let right-wing ideologues shout down the facts with a cacophony of lies and distortions. By approaching the topic from the point of view of the arts, I wanted to show that it left open the idea of interpretation—and above all, of asking questions of the landscape that can never be answered.

When I looked at the incredible beauty of Antarctica’s ice landscapes, what struck me was how alien human beings seemed in this place. No animals were scared of us; they were surprised we were there at all. I recognized that this continent needs to be preserved. The Antarctic Treaty of 1959 has kept the worst despoilers away and made Antarctica a place of true science. It was up to me to figure out the Sphinx-like landscape and see how to put it in compositional form. It’s a puzzle I’m still playing over in my mind....(more)

_______________________

New Lectoure, France

Kenneth Josephson

2003 1 2 3

_______________________

A Fantasy Piece For Helen Adam

Robert Duncan

The pyramids throbbing to the purr of the Sphinx-

her claws digging in, her luxurious gaze

fixt on the quivering horizon land

that lies enthralld in her thought as in a heat

where the great Sun by Day

burns with the fury of a lion's head,

and palls of Night

smouldering

surround the Advent of the Lion-

She broods beyond history upon a plan.

"There was a great emptiness where first I came.

It was like the body of a lion with a woman's breast and face.

It was like a woman's smile that penetrates and shakes

Paradise until a fearful expectation uncoils Itself

and speaks from the cen ter of that Place."

She watches with a murderous patience for the emergence of Man.

She kneads the sands with her paws

until from their dreaming depths

secret currents of power arise

stirring her fur with an electric wave,

charging and recharging the glare of her eyes,

all Egypt becoming a country of her hair

invaded by moonlight.

"Long before that great Architect and engineer,

enslaving the multitudes, piled up in stone

his dream of my Image

I was here.

He but erected me where I was.

Mine the lust for my own body in stone.

Mine the ancient lust for the enslavement of Man.

Mine the whips and the insurmountable way.

Mine the weights under which the builders groan.

Mine the force. Mine the sway."

From the heart of black Africa

the Nile pours forth

to lie at her feet,

supine,

spreading,

hypnotized.

in Roof: An Anthology, Summer 1976 [pdf]

Roof

all issues Jacket2 Reissue

Founded in 1976 by James Sherry to anthologize writing by poets working at the Naropa Institute, Roof magazine played a key role in the development of Language poetry.

_______________________

Front Street

Rochester, NY

Kenneth Josephson

1956

Stephen Daiter Gallery

_______________________

Fanny Howe interviewed

by Kim Jensen

bombsite

(....)

FH The 19th-century writers looked down on the world as God would. I was looking up from under, which is the feminine fate that is no longer serviceable. That must be why I was screaming off the pages. I wrote one novel after another in a fever. Seven of them belong together.

KJ So in terms of the “fate of women that is no longer serviceable,” were the modernist women writers like Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, Anaļs Nin, and Doris Lessing also “looking up from under” as you say? Do you identify with this lineage, which could include James Joyce, who was of course quite a “feminine” writer?

FH Yes, though they are all very different. Djuna Barnes? Wow. Nightwood made an impact on me. I think poetry is making the novel change into something weird and powerful. And this is coming out of the strength of American women poets on the cusp of the 20th and 21st centuries. Let’s mention Zora Neale Hurston at first, and then Bernadette Mayer, and then you can continue into Lyn Hejinian and Leslie Scalapino and dip into Dawn Lundy Martin and Ntozake Shange—poets who moved around prose and different subjectivities freely inventing.

KJ The intersection of gender and writing is fascinating. And as much as I am in love with the idea of the poetic underground—the Emily Dickinson model for women—without a certain dose of masculine ego, where would literature be? I’m immediately thinking, for example, about the late great Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish whose body of work came to fruition as the culmination of a huge talent but also from a national tragedy—a historic injustice, a poetic tradition, and a wide appreciative audience.

FH Most of those kinds of great, powerful spokespeople of our time have been men who articulated their moments very clearly—the anxiety and problem of their historical moments. But a woman has a different problem. A woman’s problem IS men!

...(more)

_______________________

25 Points

Approaching The Memoirs Of Jonbenet By Kathy Acker

Michael Du Plessis

(....)

3. Then there’s Kathy Acker, who I want to haunt me like the sun does, and she does sometimes, and she surrounds the air of the people I eat dinner with here in San Francisco.

4. Kathy Acker is a force invented by both fiction and second-hand statements that act as a guide when the bullshit becomes too much.

5. Have I mentioned there is also a chapter where JonBenet as Kathy Acker (or the other way around) is O from Story of O (which retains such a more beautiful sounding title en francais, Histoire D’O) and Rene is nowhere to be found and certainly NOT Little Lord Fauntelroy but rather Boulder is Roissy somehow and the carpet is all similar and the entire facade crumbles under the watchful eyes of O I mean JonBenet I mean Kathy Acker I mean Michael Du Plessis.

...(more)

_______________________

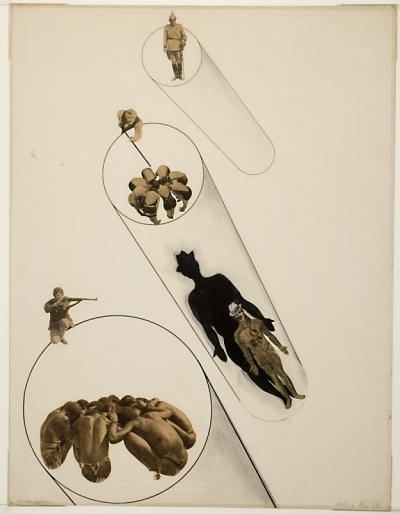

Mass Psychosis

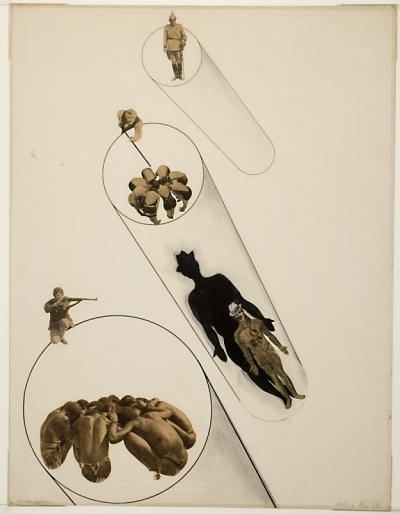

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

_______________________

The New Extremism and Politics of Distraction in the Age of Austerity

Henry A Giroux

The debate in both Washington and the mainstream media over austerity measures, the alleged fiscal cliff and the looming debt crisis not only function to render anti-democratic pressures invisible, but also produce what the late sociologist C. Wright Mills once called "a politics of organized irresponsibility." For Mills, authoritarian politics developed, in part, by making the operations of power invisible while weaving a network of lies and deceptions through what might be called a politics of disconnect. That is, a politics that focuses on isolated issues that serve to erase the broader relations and historical contexts that give them meaning. These isolated issues become flashpoints in a cultural and political discourse that hide not merely the operations of power, but also the resurgence of authoritarian ideologies, modes of governance, policies and social formations that put any viable notion of democracy at risk. Decontextualized ideas and issues, coupled with the overflow of information produced by the new electronic media, make it more difficult to create narratives that offer historical understanding, relational connections and developmental sequences. The fragmentation of ideas and the cascade of information reinforce new modes of depoliticization and authoritarianism.

At the same time, more important issues are buried in the fog of what might be called isolated and manufactured crises, that when given legitimacy, actually benefit the wealthy and hurt working- and middle-class individuals and families....(more)

_______________________

Hegemonic Masculinity and Mass Murderers in the United States

Deniese Kennedy-Kollar and Christopher A.D. Charles

The Unbearable Invisibility of White Masculinity:

Innocence In the Age of White Male Mass Shootings

David J. Leonard

photo - mw

_______________________

Oak

presented by John Latta

Isola di Rifiuti

(....)

. . . Hue

gait a day—by new

sill a rose pause seen—

nape—horse whose tizzied head

O my—lip own anatomy

the oak I. Trivial uttered

hard to stand under . . .

—

Louis Zukofsky, out of “A”-23 (“A”-22 & -23, 1975)

(....)

. . . There was no life you could live out to its end

And no attitude which, in the end, would save you.

The monkish and the frivolous alike were to be trapped in death’s capacious claw

But listen while I tell you about the wallpaper—

There was a key to everything in that oak forest

But a sad one . . .

—

John Ashbery, out of “The Ecclesiast” (Rivers and Mountains, 1966) ...(more)

_______________________

Sol Lewitt: Sentences on Conceptual Art

First published in 1969

Lemon Hound

(....)

The concept and idea are different. The former implies a general direction while the latter is the component. Ideas implement the concept.

Ideas can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form. All ideas need not be made physical.

Ideas do not necessarily proceed in logical order. They may set one off in unexpected directions, but an idea must necessarily be completed in the mind before the next one is formed.

For each work of art that becomes physical there are many variations that do not.

A work of art may be understood as a conductor from the artist’s mind to the viewer’s. But it may never reach the viewer, or it may never leave the artist’s mind.

...(more)

_______________________

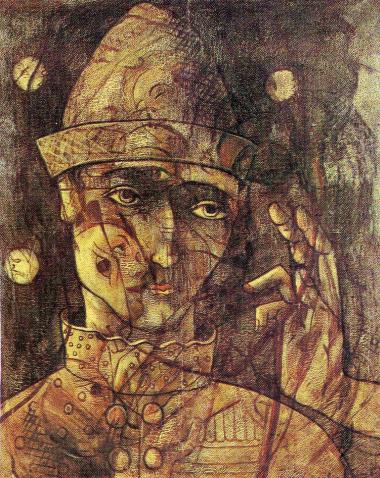

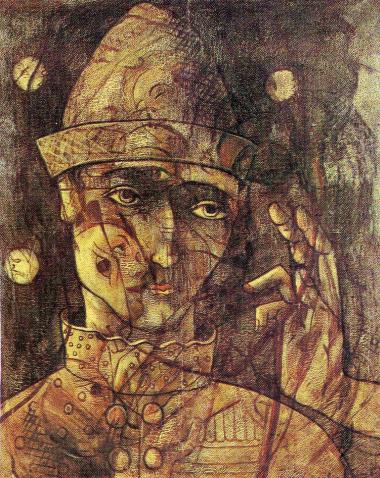

Transparence (Hera)

Francis Picabia

b. Jan. 22, 1879

_______________________

The Self in Self-Help

We have no idea what a self is. So how can we fix it?

Kathryn Schulz

(....)

I know people who wouldn’t so much as walk through the self-help section of a bookstore without The Paris Review under one arm and a puzzled oh-I-thought-the-bathroom-was-over-here look on their face. I understand where they’re coming from, since some of the genre’s most persistent pitfalls—charlatanism, cheerleading, bad science, silver bullets, New Age hoo-ha—are my own personal peanut allergies: deadly even in tiny doses. And yet I don’t share the contempt for self-help, not least because I have sought succor there myself. The first time was for writer’s block—which is, I realize, a rarefied little issue, sort of the artisanal pickle of personal problems. (I got over it: QED.) The second time was for its very nasty older brother, depression—of which more anon. In both cases, I ventured into the self-help section for the usual reason: the help. Last month, though, I went back to investigate the other half of the equation: the self.

If, like me, you have read your way through sober Stephen R. Covey (The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People) and godly Norman Vincent Peale (The Power of Positive Thinking), through exuberant Tony Robbins (Unleash the Power Within) and ridiculous Rhonda Byrne (The Secret), through John Gray who Is From Mars and Timothy Ferriss who has a four-hour everything and Deepak Chopra who at this point really is one with the universe (65 books and counting)—anyway, if you, too, have reckoned with the size and scope of the self-help movement, you probably share my initial intuition about what it has to say about the self: lots. It turns out, though, that all that surface noise is deceptive. Underneath what appears to be umptebajillion ideas about who we are and how we work, the self-help movement has a startling paucity of theories about the self. To be precise: It has one.

...(more)

The Self-Help Issuenew york magazine

_______________________

Fantasmas flotantes

Willi Baumeister

b. Jan. 22, 1889

_______________________

The Normal Well-Tempered Mind

A Conversation with Daniel C. Dennett

edge

(....)

Evolutionary biologist David Haig has some lovely papers on intrapersonal conflicts where he's talking about how even at the level of the genetics, even at the level of the conflict between the genes you get from your mother and the genes you get from your father, the so-called madumnal and padumnal genes, those are in opponent relations and if they get out of whack, serious imbalances can happen that show up as particular psychological anomalies.

We're beginning to come to grips with the idea that your brain is not this well-organized hierarchical control system where everything is in order, a very dramatic vision of bureaucracy. In fact, it's much more like anarchy with some elements of democracy. Sometimes you can achieve stability and mutual aid and a sort of calm united front, and then everything is hunky-dory, but then it's always possible for things to get out of whack and for one alliance or another to gain control, and then you get obsessions and delusions and so forth.

You begin to think about the normal well-tempered mind, in effect, the well-organized mind, as an achievement, not as the base state, something that is only achieved when all is going well, but still, in the general realm of humanity, most of us are pretty well put together most of the time. This gives a very different vision of what the architecture is like, and I'm just trying to get my head around how to think about that.

What we're seeing right now in cognitive science is something that I've been anticipating for years, and now it's happening, and it's happening so fast I can't keep up with it. We're now drowning in data, and we're also happily drowning in bright young people who have grown up with this stuff and for whom it's just second nature to think in these quite abstract computational terms, and it simply wasn't possible even for experts to get their heads around all these different topics 30 years ago. Now a suitably motivated kid can arrive at college already primed to go on these issues. It's very exciting, and they're just going to run away from us, and it's going to be fun to watch.

The vision of the brain as a computer, which I still champion, is changing so fast. The brain's a computer, but it's so different from any computer that you're used to. It's not like your desktop or your laptop at all, and it's not like your iPhone except in some ways. It's a much more interesting phenomenon. What Turing gave us for the first time (and without Turing you just couldn't do any of this) is a way of thinking in a disciplined way about phenomena that have, as I like to say, trillions of moving parts. Until late 20th century, nobody knew how to take seriously a machine with a trillion moving parts. It's just mind-boggling.

...(more)

_______________________

Eiko and Koma I

Philip Trager

1993

_______________________

Three poems by Osip Mandelstam

translated by Stephen Dodson

Qarrtsiluni

Insomnia. Homer. Taut sails.

To midpoint have I read the catalog of ships:

That long, that drawn-out brood, those cranes, a crane procession

That over Hellas rose how many years ago,

Cranes like a wedge of cranes aimed at an alien shore—

A godly foam spread out upon the heads of kings—

Where are you sailing to? If Helen were not there,

What would Troy be to you, mere Troy, Achaean men?

Both Homer and the sea—everything moves by love.

Who shall I listen to? Homer is silent now,

And a black sea, a noisy orator, resounds,

And with a grinding crash comes up to the bed’s head.

...(more)

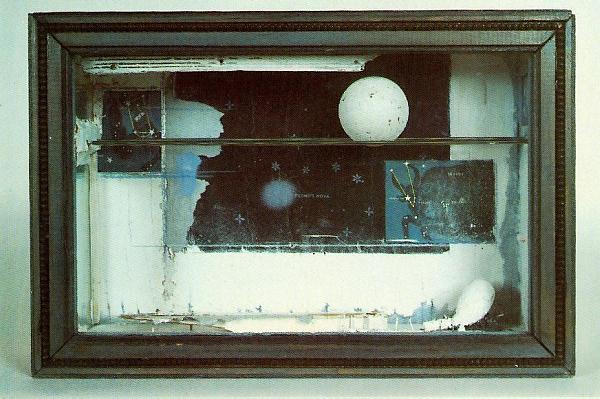

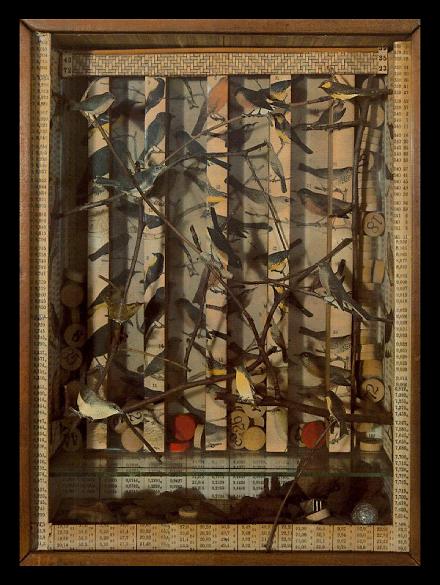

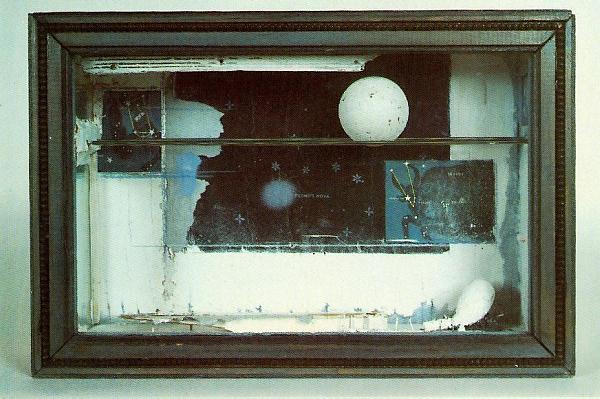

Cassiopeia 1

Joseph Cornell

_______________________

A letter from Joseph Cornell to Dorothea Tanning

by Robert Kelly

brooklyn rail

(....)

The body is a sheen of glory with nothing inside it. The skin is our panoply and declaration. We artists are so fortunate, because we are the servants and masters of the visual world, the world of shape and color, form and geometry, tension and release, we are the lords and ladies of blank space! And all that happens to fill it! We know that what we see when we look with our artist loving judging smart tender broken eyes, when we look at someone standing there, we see the utter and absolute truth of him. We say: I see you. And that is exactly right. When I look at him, I see him. I see all there is. Poets and psychiatrists and philosophers and other types who do not have the grace of seeing, they talk about personality and character and inner motivation and neurosis and meaning and drives and complexes and memory and desire, they rave on and on about those things and think that such things somehow live inside the person they have before them—the person they don’t know how to see. All that stuff, all that cognitive crap (forgive the coarse word, my dear, mama isn’t looking), is lies. Personality is a lie. Psychology is a lie. People say I make my little boxes (focused environments?) to represent the tumult of repressed images and confusions in me. Not at all. My boxes express nothing but themselves. Don’t people understand that artists aren’t spewing out their guts, they’re adding things to the world. We are increasing the intensity and beauty of matter. And one day matter itself will be perfect and complete, and this will be heaven. Our heaven, because we made it so, and knew it true.

...(more)

_______________________

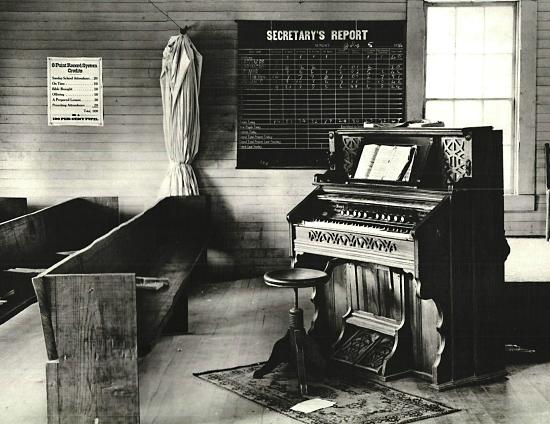

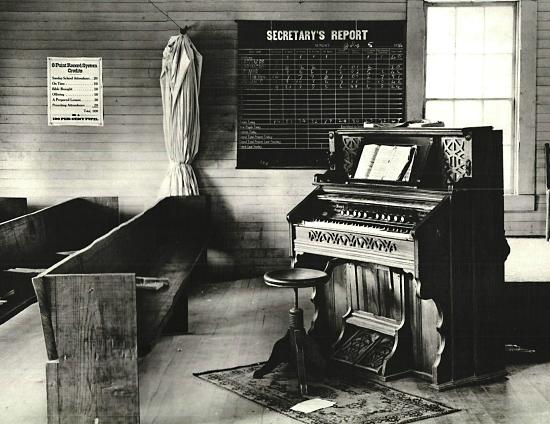

Walker Evans

.....................................................

Ghost is Guest

Ana Solal on Walker Evans' Message from the interior

Translated from French by Chris Farmer and Florian Aimard

The book’s title – Message from the interior – is both open and reserved, preparing the reader not only for its subject matter, but also for the atmosphere of intensity it contains. Here, through objects and places, the photographer speaks to us of absence, the difficulty of communication and the passage of time. Starting with the book’s physical incarnation, one first notices the tender care taken in separating each print with a fine sheet of tracing paper, and that the intense black finish appears to be lightly coated with a metallic sheen. The project’s overall tone meanders through a strange union of the human voice’s warmth and the night’s bitter chill....(more)

_______________________

All Streets Lead to the Sea

Andre Bagoo

allmost island

Chacon Street

For those who walk the pavement below, the building is invisible.

Small stores are fronts for a hidden chamber, where a silver

Car, daily, is parked. Invisible are the three floors in this moss-hulk

Where the rooms are knots. Naked men sleep outside by a black

Iron gate concealing mystery, they know. They all know.

Shreds of plastic bags, cardboard, sticks – the apparatuses of their

Deception – will one day revert to the Cathedral, with its fine stone

Pillows. And the men will all rise, walk past the mall

Nobody shops in, past: the empty lots the colour of rum and piss, the old

Colonial Building and Loan Society building, and the madder wall

Oozing puzzling chemistries, and say, ‘This is where joy lives

On the saddest street in the world.’

...(more)

_______________________

There are all too many people who, in some great period of social change, fail to achieve the new mental outlooks that the new situation demands. There is nothing more tragic than to sleep through a revolution. There can be no gainsaying of the fact that a great revolution is taking place in our world today. It is a social revolution, sweeping away the old order of colonialism. And in our own nation it is sweeping away the old order of slavery and racial segregation. The wind of change is blowing, and we see in our day and our age a significant development. Victor Hugo said on one occasion that there is nothing more powerful in all the world than an idea whose time has come. In a real sense, the idea whose time has come today is the idea of freedom and human dignity. Wherever men are assembled today, the cry is always the same, ‘We want to be free.’ And so we see in our own world a revolution of rising expectations. The great challenge facing every individual graduating today is to remain awake through this social revolution.”

- Martin Luther King Jr., Oberlin College Commencement Address, 1965

_______________________

The Centre Cannot Hold: Six Contemporary Filipino Poets

Stuart Cooke

cordite review

Three Poems by Mabi David

Toy

And because I’d gone ahead and done

the unthinkable, I want to know

what else I won’t ever do. I go ahead

and do that too. I think of a thing or two

the mere thought of which makes me

retch: I do it. And do it

until the idea of me and my turns

silly, toy, being built a certain way

has little truth, until I get to the bottom

of where I came undone and keep at it

until the hurt it gives gets good

and the good I give gets animal.

...(more)

_______________________

Joseph Cornell

Shomei Tomatsu

_______________________

World enough

John Quiggin

aeon

... can we share the advantages of the developed world with the entire population of the planet without running into limits on mineral and renewable resources? Not according to many environmentalists. They say we can’t even maintain them for the few people who presently enjoy them; that it’s technologically impossible to sustain current consumption levels on a global scale, let alone to spread prosperity more broadly.

Having spent much of my professional life as an economist studying problems of this kind, I’m convinced that this is not true. The question is not: ‘Can we let everyone live like prosperous residents of the First World without destroying our natural environment?’ It is: ‘Will we?’ A balance is achievable, if we want it. That goes against a lot of powerful convictions, of course. So, although arithmetic might not be part of everyone’s idea of utopia, we need to look at the numbers....(more)

_______________________

Cruel Optimism

a symposium on Lauren Berlant's book at Social Text

Lauren Berlant’s most recent book, Cruel Optimism (Duke UP, 2011), undertakes the ambitious and necessary project of thinking the political present. Cruel Optimism attends closely to what goes undernoticed about living in relation to waning or worn-out models of legibility, sovereignty and sustainability. Working through the rhythms of crisis ordinariness, patiently tracking the emergence of new genres, styles and modes of response to the diffused conditions of precariousness that constitute contemporary life, revising critical models of agency to incorporate the floundering and gestural ways people attempt to make sense of their worlds, Cruel Optimism extends Berlant’s longstanding critical concern with the development of intimate publics into the present, exploring “what happens to fantasies of the good life when the ordinary becomes a landfill for overwhelming and impending crises of life-building and expectation whose sheer volume so threatens what it has meant to ‘have a life’ that adjustment seems like accomplishment.”

This dossier assembles responses to the book by scholars Kandice Chuh, Lisa Duggan, Micki McGee, José Muńoz, Sianne Ngai, Kathryn Bond Stockton, Kyla Wazana Tompkins, and Rebecca Wanzo. In a dialogue with dossier editor Dana Luciano, Berlant engages these responses in turn and reflects on her own recent and forthcoming projects.

_______________________

The Peter Iredale

Oregon

Photo: Sarah Lynch

30 Beautifully Haunting Shipwrecks

gizmodo

_______________________

The Lefka Tree & New Aural Fashions

Mark Sargent

exquisite corpse

3. The Kung Fu master has no ride

(....)

Ah grasshopper, may all our cryptic utterances

squeegee away the condensation of illusion

and may the donkey of good fortune

always be tied in your orchard.

Nevermind the martial arts, we walk through the fig orchard

to the beach, the sun flashes off the churning waves washing

great stretches of empty sand and

over the hill come two fire planes roaring,

huge lumbering yellow swallows swooping over the sea to drink.

Somewhere near is burning, the planes return every ten minutes

arcing over the blue, pounding along the waves then laboring up

barely clearing the eucalyptus trees along the shore and the boys

are manic in the surf and radiant in the September light.

Life’s too short for idylls, we snatch these foaming moments

on the curl, even the children are too old for innocence.

We float in the luxury of the sea

yet always the waves push us towards the beach,

the lies we find ourselves leading,

beknotted with so many

everyone pulling in another direction

yet the rotation of things churns on:

every year the turtle people show up,

the animals breed, the tree grows,

the plans,

our gestures fall short of the fatal.

...(more)

_______________________

Protest

Shomei Tomatsu

Michael Hoppen Gallery

Remembering Shomei Tomatsu (1930-2012)

_______________________

E·ratio 16 · 2013

ITERLOGUE 1-10

Spencer Selby

2

Framed need or wrinkled

wish that cannot be fulfilled

In the long run only pause

while existence has never

been more than dread good

getting used to static before

a transformation confused

with bushes leaves no trace

in the wind-ruffled prints of

bare feet and legs outstretched

on the move dumping facts

that give the impression of

a spacious landscape in the

windows hazy from smoke

while in reality air itself is

a forest of fading barriers

built up with transmitters

tempting manifold forms

determined to go by instinct

to judge demand returning

from a nearby market feeling

impossible attempt made

at communication during

torrent from book still closed

...(more)

_______________________

Speaking Truth to Power

a collection of writings by and about Aaron Swartz.

Bob Stein

if book, a project of the future of the book

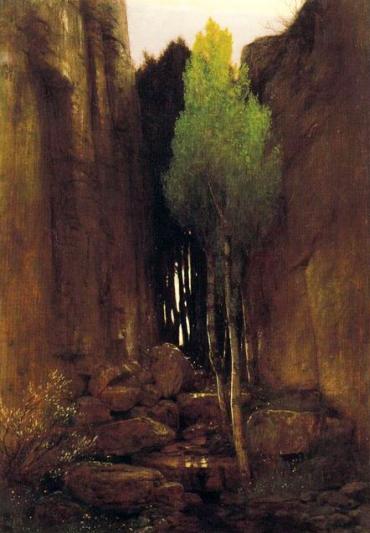

Arnold Böcklin

d. Jan. 16, 1901

_______________________

Alms for Oblivion

Lapham's Quarterly

(....)

Whether declared by church or state, the war against human nature is by definition lost. The Puritan inspectors of souls in seventeenth-century New England deplored even the tentative embrace of Bacchus as “great licentiousness,” the faithful “pouring out themselves in all profaneness,” but the record doesn’t show a falling off of attendance at Boston’s eighteenth-century inns and taverns. The laws prohibiting the sale and manufacture of alcohol in the 1920s discovered in the mark of sin the evidence of crime, but the attempt to sustain the allegation proved to be as ineffectual as it was destructive of the country’s life and liberty. Instead of resurrecting from the pit a body politic of newly risen saints, Prohibition guaranteed the health and welfare of society’s avowed enemies. The organized-crime syndicates established on the delivery of bootleg whiskey evolved into multinational trade associations commanding the respect that comes with revenues estimated at $2 billion per annum. In 1930 alone, Al Capone’s ill-gotten gains amounted to $100 million.

(....)

If what was at issue was a concern for people trapped in the jail cells of addiction, the keepers of the nation’s conscience would be better advised to address the conditions—poverty, lack of opportunity and education, racial discrimination—from which drugs provide an illusory means of escape. That they are not so advised stands as proven by their fond endorsement of the more expensive ventures into the realms of virtual reality. Our pharmaceutical industries produce a cornucopia of prescription drugs—eye opening, stupefying, mood swinging, game changing, anxiety alleviating, performance enhancing—currently at a global market-value of more than $300 billion. Add the time-honored demand for alcohol, the modernist taste for cocaine, and the uses, as both stimulant and narcotic, of tobacco, coffee, sugar, and pornography, and the annual mustering of consummations devoutly to be wished comes to the cost of more than $1.5 trillion. The taking arms against a sea of troubles is an expenditure that dwarfs the appropriation for the military defense budget....(more)

_______________________

A conversation with Jonathan Miller

... when I say I'm not an atheist, it's not that I'm an agnostic and I'm hedging my bets. It's just that I cannot think it is worth having a word to describe it. It's so trivial, my not believing in God in the present day. I don't believe in witches, but I don't call myself an ahexist....(more)

_______________________

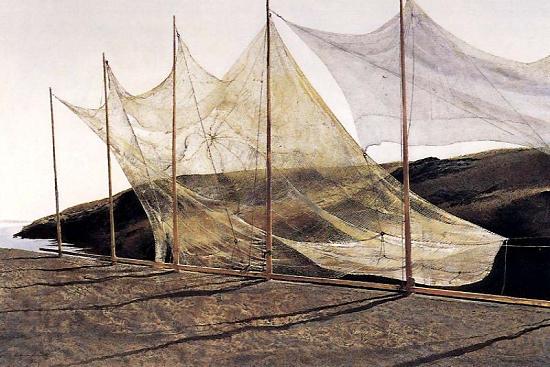

Pentecost

Andrew Wyeth

Andrew Wyeth

d. Jan. 16, 2009

©David Alan Harvey/Magnum

_______________________

Interview with Andrew Gallix

Editor-in-Chief of 3 AM Magazine

(....)

... I am absolutely fascinated by the impact that someone’s physical and psychological life can have on his/her thinking and writing — how apparently rational choices are due, for instance, to a tiny todger, short stature, child abuse, or the absence of a parent. Sartre claimed that he began writing to make up for his ugliness and impress women. We all want to be loved, and writing is always a love letter of sorts. As Richard Brautigan put it, “Just because people love your mind, doesn’t mean they have to have your body” — but one lives in hope, of course.

Perhaps Cioran’s remark makes more sense in the context of philosophy, but literature is the space of contradiction and ambiguity, and that’s what interests me....(more)

Full Stop

_______________________

Borges’ translation of Ulysses

Or of the last page of Ulysses as a translation of Ulysses

Erķn Moure

jaclet2

In post 7, I quoted Sergio Waisman from Borges and Translation: The Irreverence of the Periphery: “Like any act of writing, translation is always undertaken from a specific site: the translator’s language, but also the entire cultural and sociohistorical context in which translators perform their task.” In the in-traduisible, we translate the intra-duisible. Induce the text through the veil of the nuisible.

Which makes it almost impossible to answer the question of who the translator serves. The reader-cannibal-flesh/word-eater? Or the mercenary-writer who uses the translator (sometimes from beyond the grave) to pull a hat over her or his own face? Translating, one wishes to serve the text itself, but the conditions of reception in one’s own language make the process like shuffling a deck of cards with your arms behind a curtain.

The translation that results bears the memory of the original, and also incorporates into its fibre the resistance of the reader to let the foreign into their language, the resistance that is a cauterization of any reading practice from its very start: because we live somewhere. Somewhere translates itself into the translation. The prescription of untranslatability may haunt the translator, but as I translate, no, I am not haunted, I turn and wear the text, making its fibre into my fibre.

I think here of Borges, who in January of 1925 published the first translation in the Spanish-speaking world (so many sites!) of James Joyce’s Ulysses in the Argentinian magazine Proa, nine years before the book was available in English in North America (its first printing was burned as obscene on arrival from Europe)....(more)

_______________________

the little Tay

Perth, ON

photo - mw

_______________________

Fascism: Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies

Studying Fascism in a Postfascist Age. From New Consensus to New Wave?

Roger Griffin

Abstract

The article suggests a way of mapping the remit for Fascism: Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies by considering how far a “new consensus” has formed between specialists working in this area which conceptualizes fascism as a revolutionary form of ultra-nationalism that attempts to realize the myth of the regenerated nation. It is a myth which applied in practice creates a totalitarian movement or regime engaged in combating cultural, ethnic and even biological (‘dysgenic’) decadence and engineering a new sort of ‘man’ in a alternative socio-political and cultural modernity to liberal capitalism. Having surveyed empirical evidence for the spontaneous emergence of a broad, though contested, scholarly convergence around this approach in the historical and social sciences in the last two decades, even beyond Anglophone academia, the article suggests that this development is part of an even wider phenomenon. This is the tendency for scholars to take seriously the utopian ideological and cultural dynamics of political phenomena once generally dismissed as exercises in the monopoly of power, of exercise of violence for its own ‘nihilistic’ sake rather than as a rebellion against nihilism in the search for a new order. It finishes with a reminder from several experts that fascism is not a static or immutable phenomenon, an insight that demands from scholars a willingness to track the way it adapts to the unfolding conditions of modernity, thereby assuming new guises practically unrecognizable from its inter-war manifestations.

|