Schipol Airport, Amsterdam Thursday, March 11

I enter the waiting room for Gate D5. The ratio of men to women appears to be about 60/40. Very few of the women have their heads covered. As boarding time approaches, the scarves start to go up. Many of these coverings, though, continually slip back, as though the person underneath is pushing it away.

I do not see any woman pass by the ticket taker without her scarf in place. Once in the lounge, they start, once again though, to fall back.

There is one woman on the flight who remains uncovered and I have not yet seen her scarf. She is dressed in jeans and is with a male companion.

I have only observed two female cabin crew and several males. All of them are middle aged. The two women are almost stern in their composure. Their faces reveal nothing, as they glance about the cabin.

An older woman stands in the aisle engaged in conversation. Her face sparkles as she smiles continually. Her light demeanor is highlighted by her light blue and cream-colored head scarf.

There is still a reluctance to stay in place being expressed by some of the head scarves, but the closer we get to the Islamic Republic of Iran the more firmly they stay up. All, that is, except for the woman in seat 7A.

Headsets are being handed out, but there doesn’t appear to be anything to listen to. We continue to watch a toy plane traverse Europe on its way to Tehran on our TV screens.

Sometimes I wonder if I should be censoring my writing, for fear someone will insist on reading my words before I enter the Republic. Fear has the power to shape and direct behavior in many ways.

To me, most passengers on this plane appear to be native of Iran. There is much friendly banter. I expect these people are not representative of the population, as these are people who can afford to fly to Europe. Perhaps, though, they are ex-pats returning for a visit.

Suddenly, a movie begins to show on the screen. A quote from Charles Dickens flashes on the screen: “I hope we are all judged based upon the truth.” The movie, with English sub-titles is called “The Last Dinner”. I find the movie engages me. In some ways it seems to parallel “Reading Lolita in Tehran”, as it is about a Professor of Architecture at the University of Tehran. In this story, however, the 45-year-old Professor is sought after by a much younger man in his twenties. It is an interesting social commentary on the institution of marriage.

With the movie over, I am now intrigued by the route of our aircraft displayed on the screen. From Amsterdam across Europe, we cross the Black Sea north of Istanbul. We continue south easterly to the border with Iraq, and then veer left, staying in Turkish airspace to the Iranian border. Our groundspeed is in excess of 1,000 km/h, so far topping out at 1020 km/h.

I am speaking with my seatmate and I ask him if he is from Iran. “No”, he states, “I am from Kurdistan.” We talk about the movie we have just seen, which leads to a discussion of the social situation in Iran. He explains that in many places, such as Europe, people are living for today. “Here, we live for the future.” His expression is relaxed, and he speaks with confidence.

You know you are in Iran when you exit the door of your Airbus 300 onto an unsheltered stairway leading down to the tarmac. You then walk to a waiting crowded bus, where everyone stands, holding on for dear life as we make our way to the airport. As we start rumbling along I have no idea how long this part of my journey will take, but mercifully, it ends after three or four minutes. I simply follow the crowd.

Ours is the second of two flights to arrive within minutes of each other and the passport control lines are deepening. I am standing behind a short balding, yet swarthy gentleman who, upon noting my Canadian passport, strikes up a conversation. I note that I am feeling guarded in my response, as I am unsure of his motives. Suddenly, a man appears behind me to my right and, without warning, snatches my passport and entry document and begins scribbling on it. Perhaps noticing my startled look, he starts to explain, “validation” and hands my documents back. By this time my “swarthy” companion has explained that he is of Iranian origin but now a Canadian, and the person who snatched my passport was a policeman who just made my entry a little bit easier. I just think to myself “I hope so.” (Later, I reflect that perhaps this was the reason they required me to submit a photograph of myself when I applied for my visa.) Easy, though, my entry is, as no questions are asked as my passport is stamped.

Next I approach what I assume to be custom control where I will be questioned. There is a simple guard with an x-ray machine to my right, and about fifty feet of open space to his left. About fifty feet directly in front of me is a vast sea of faces. I place my bag in the x-ray machine. Apparently I pass inspection as I am waved through without questioning. I am free to join the sea of faces. But, is one of them familiar to me? And then, I spot Masoud. I dive in, we meet, and he introduces me to his brother Ali.

Within half an hour of touching down, I am walking to the parking lot. The driving in Tehran is surreal. In a word, it is nightmarish. The main problem with traffic in this country is that very few people follow the rules of the road. Cars drive without headlights. I observe four people on a motorcycle driving on the wrong side of the road. I will have more to say about it later, but it is like nothing I have ever seen.

After about half an hour of hell on the streets, I am introduced to Masoud and Ali’s mother in her beautiful three-bedroom apartment, just off of Vali-Asr Street. It is after two in the morning before I am asleep.

After a simple breakfast I am experiencing Tehran traffic in daylight. Traffic is an overwhelming consideration, as I will later find out, in this country. There are simply too many cars, and not enough infrastructure to carry those cars. It is constant chaos.

In my first venture into it we head north to a mountain overlooking

Tehran known as Tochal. Being Friday, it is a day off for most people

in this country. Thousand of mostly young Iranians have come here to walk

up the road or hike up the cliffs. A uniformed man stops four very attractive

young women. I am told that in the eyes of the police they are not appropriately

dressed for public as they are wearing tight clothes. Their only deference

to Islam is the loosely worn headscarves.

In my first venture into it we head north to a mountain overlooking

Tehran known as Tochal. Being Friday, it is a day off for most people

in this country. Thousand of mostly young Iranians have come here to walk

up the road or hike up the cliffs. A uniformed man stops four very attractive

young women. I am told that in the eyes of the police they are not appropriately

dressed for public as they are wearing tight clothes. Their only deference

to Islam is the loosely worn headscarves.

Men and women also are not permitted to touch each other in public according to Islamic law. However, that doesn’t mean it never happens, as our observation up the mountain discovers. We notice what appears to be someone far up the slope. Using the zoom of my camera shows there are actually two people who are perhaps closer than the Republic would ordinarily permit. There is some behaviour that is simply too natural for any law to curtail.

The landscape is rugged with mountains looming to the north. They are barren, devoid of any vegetation. A strong wind swirls dust and debris around us. Tehran is a city whose population is well over ten million, having doubled in less than twenty years. Building sites are continually being developed up the mountain slopes. This population also is young, with over half under the age of thirty.

My time in Tehran is cut short, as I have a four thirty flight to Shiraz. This requires another round of Tehran traffic. The city is choking with cars, fulfillment of a government decision to build millions of cheap vehicles for the masses. The brand name is the Paykan. The demand for transportation far exceeds the supply. At virtually every street corner I see lines of people trying to flag down a ride, for a price. Many vehicles with empty seats are usually seen pulling over to the curb (or within a few meters) and negotiating the price of a ride with those standing by the road. The starting price for a straight line ride of a couple of kilometers is 100 toman (about fifteen CDN cents). If you want the car to yourself, you have to pay for all five seats, or five times the price. If you are in the front bucket seat, expect to share it.

Our initial flight takes us to Shiraz, where, after a three-hour stopover, we fly to Esfahan, arriving at 9:30 that evening. Hundreds of years ago this city was the capital. At its height, the Shah Abas ruled an area extending from Turkey to India from this city.

The Esfahan airport has recently been rebuilt and has a modern feel to it. The buildings have a fine stone façade. Esfahan is a city of art. This becomes clear to me as our taxi takes us to our hotel. Our driver welcomes me to “antique” Iran. He shares a laugh with Masoud on this comment as I realize he is not just talking about the buildings. We drive down a wide boulevard on the south side of the Zayandeh River. This takes us past some of their famous bridges, first the Khajou Bridge, the Jouee Bridge, and finally stopping in front of Se-o-Se Pol Bridge. Our hotel, the Suites, and our second floor room, overlooks this famous site.

After two days in this beautiful city I feel I have lived an explosion of experiences since arriving. These experiences have been relentless. I feel pummeled. And, I would not trade a moment of it. I have a strong need to put these last two days into perspective, before the memory fades.

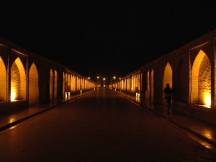

Our hotel is (according to my map) at the corner of Chadar Bagh and Boustan-e-Mellat, overlooking Se-o-Se Pol Bridge. The literal translation of this bridge is “thirty-three bridges” bridge, because of the thirty-three arches in its structure. Just say “Se-o-Se Pol” to any Iranian, and they seem to know what you mean, and where you have been.

The hotel itself is a standard, mid-city hotel, outfitted with brass and a uniformed bellhop. Our room costs 45 USD per night. Upon arrival on Friday evening, I am tired but exhilarated. Masoud wants tea and a bite to eat, and has already noted a teahouse across he road that should fit the bill. However, our second floor corner room with small balcony affords us some of the best entertainment in town, watching the traffic.

I find it difficult to pull myself away from the real life movie that constantly unfolds before me. Cars making a left hand turn from the far right side of the road, cutting against oncoming traffic on the opposing street to make a u-turn. Throw in a half a dozen pedestrians going in whatever direction suits them, a motorcycle or two traveling against traffic without headlights, perhaps carrying two or three passengers, and a couple of police officers standing in the boulevard observing it all with me.

It is after eleven o’clock before we head to the tearoom. I descend into the basement of a non-descript 1960’s three-storey commercial building. On the left are some large polyester bags. To my right is a rectangular room covered in carpet with carpeted and cushioned raised areas about eight feet square around the sides. Several groups of young men are sitting, smoking from traditional pipes and drinking tea. A young man sitting at a table directly in front of the entrance greets us. Masoud explains to me that we must remove our shoes before entering. Now the purpose of the bags becomes apparent, as they are for our shoes. We sit in the nearest raised area, ordering tea and mint tobacco.

Our host, a young man in his twenties, decides to sit down and join us in conversation. He explains that all businesses must close by midnight, and that the authorities will check to ensure that everyone complies. As we still have not yet eaten, we decide to finish our tea and smoke and find a snack in one of the shops above us. Having purchased sausages in a bun, we take a midnight walk across Se-o-Se-Pol. Even at this late hour the streets are still alive with traffic and strolling young people.

The stone of Esfahan is unique yellow ochre. It is seen throughout the city, including this bridge. A strong wind is blowing as I sit on a park bench viewing the beautiful thirty-three arches. Suddenly, I observe a woman in full flowing black chador walking north on the path to the bridge. She is a haunting lonely figure, silhouetted against the yellow light of the bridge.

It is so beautiful this night, I feel like I never want to go to bed. The warm breeze, the extraordinary site of this fascinating architecture entrances me. It is well past midnight before we stroll back to our hotel room.

We have two days in Eshfahan before departing for Shiraz early Sunday evening. We intend to make the most of our time. We once again walk across Se-o-Se Pol this time on a beautiful Saturday morning. Traffic, as ever, is chaotic. Just crossing the street requires skill not resident in most westerners. Masoud instructs me to stay close, and follow me. I feel like a child as he offers me his hand to begin the slow yet steady dodge and weave through cars, bicycles, and people. Over time, I develop this skill and will feel bolder as I venture into traffic. For now, however, I am Masoud’s shadow, mimicking his every move as we cross the street.

It is now time to find a taxi, so we join the crowds standing near the curb and Masoud begins the process. Cream-colored Paykans (apparently the Iranian national brand of car) continually pull over, and the negotiation begins. I soon find myself jammed in the back seat and off we go. Including the driver there are at least five people, and occasionally up to seven in the vehicle as we head to our destination near the famous bazaar of Eshfahan.

I found the following information on the web:

The bazaar forms a part of the Imam Khomeini (former Naqsh-e Jahan) Square, which is one of the largest and most beautiful squares in the world. This square, measuring 500 x 160 meters, was set up in the second half of the 16th century AD by the Safavid King, Shah Abbas I. On the south side of the square is the Imam Mosque. The Ali Ghapou monumental compound on the west and Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque on the east occupy other sides of the square.

The Isfahan bazaar is essentially a district consisting of numerous streets

with stores on both sides connected together, under a high-rise roof. Some

of the arcades, including the textiles bazaar and the Qeisariye market,

have been ornately designed, thanks to their proximity to the royal

palaces, and the famous mosques. In order to provide the necessary

lighting for the bazaar's environment, some skylights were built

on the roof to let the sunlight in.

I have visited Tianenmen Square, reputedly the largest in the world. It pales, however, to what I am viewing now. This is alive with people, activity and history. From the beautiful mosques, to the Ali Ghapou compound, and the bustle of commercial activity, to say it is steeped in history and culture is certainly understatement.