Larry Lavitt

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tickling the Dragon's Tail

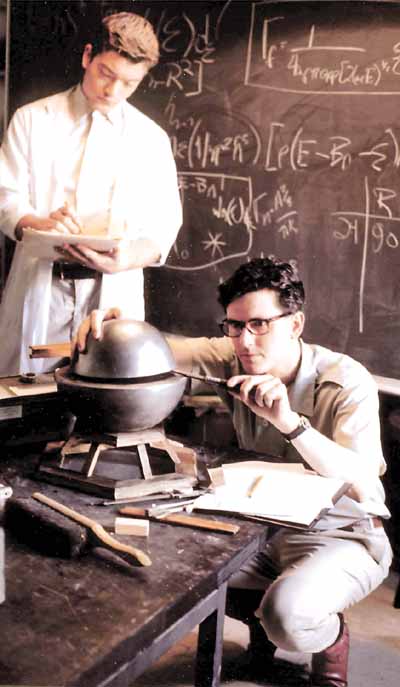

UNSUNG HEROBy Brad Oswald, ColumnistWinnipeg Free Press, Friday, April 16, 1999 Imagine, if you can, what must go through your mind the moment death arrives. Then try to imagine realizing you're dead, but having to wait nine more days for the end to actually arrive. That is, for all intents and purposes, the fate that befell Louis Slotin, a brilliant, locally born scientist who played an instrumental role in the development of the first atomic bomb. It was May 21, 1946 - mere months after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought an end to the Second World War, and less than a year after a triggering mechanism he built was used to detonate the first test bomb, nicknamed Trinity, in the New Mexico desert - when a laboratory accident exposed Slotin to a lethal dose of radiation. The mishap might have been even more tragic, but Slotin's decisive, heroic action saved the lives of several other scientists in the laboratory. The little-known story of this celebrated Winnipegger's remarkable life and untimely death is told this weekend in Tickling the Dragon's Tail: The Story of Louis Slotin, a fascinating one-hour documentary that airs tomorrow at 8 p.m. on Global. The title of the film refers to a dangerous, hands-on technique used by Slotin and his contemporaries to create the beginnings of a fission reaction by bringing two metal hemispheres of highly reactive, beryllium-coated plutonium close together. The idea of the procedure - which was conducted bare handed, with nothing more than a screwdriver and the scientist's wits to judge the critical separation - was to bring the two halves as close together as possible without allowing them to touch. Slotin had "tickled the dragon's tail" at least 40 times before. On that fateful, day, however, the dragon turned around and bit him. The screwdriver slipped, the hemispheres came in contact, and a blue glow and a wave of heat swept through the room. Slotin acted instantly, probably instinctively, using his body to shield his co-workers from the radiation while he separated the hemispheres. "By his actions, he was able to prevent the other men in the room from suffering permanent injury," said Winnipeg writer Martin Zeilig, who has been researching Slotin's story for more than a decade. "I think it's remarkable that he had the wherewithal and the presence of mind to do what he did. "His comment to one of his co-workers was, 'You'll be OK, but I think I'm done for.' He knew right away what had happened to him." Slotin died nine days later, with his family by his side. His body was flown back to Winnipeg in a lead coffin - under instructions from the U.S. military that it was not to be opened under any circumstances - and a funeral was held at the Slotin family's home. More than 3,000 people crowded onto Scotia Street for the outdoor service. Zeilig, who has written several articles about Slotin's accomplishments, acted as researcher, co-writer and associate producer of the documentary. The film was produced by Edmonton-based Great North Productions, whose past credits include the Canadian TV series Jake and the Kid and Destiny Ridge. He said it's important to tell this story because most U.S.-written histories of the development of the atomic bomb have overlooked Slotin's role. "If you look at any of the histories of the Manhattan Project, Louis Slotin is hardly mentioned - if anything, he's generally a footnote." said Zeilig. "He was an important figure, but he was not viewed as a major figure. I guess that's partly because he was working alongside some of the greatest minds of the century - Oppenheimer, Teller, Fermi and the rest of them. But he was a crucial part of the machinery that built the first atomic bomb." The eldest of three children of Russian-Jewish immigrants, Louis Slotin was an exceptionally bright kid who graduated near the top of his class at St. John's High School and attended the University of Manitoba. His academic performance earned him a scholarship at King's College in London, England, and upon his return to Canada, he applied for a job with the National Research Council. He was rejected - the film suggests the slight was the product of lingering anti-Semitism within the government of the day - so, with financial support from his father, Slotin took an unpaid research position at the University of Chicago - which for intellectuals, during the 1930s, was considered the place to be. His efforts there caught the attention of scientists working on atom-splitting research and when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour pulled the U.S. into the Second World War, Slotin was part of the team that began the frantic race to develop the bomb before Hitler could. "The family knew about the work he was doing before the war, because it was just applied research with the cyclotron and with early radiation treatments for cancer patients," explained Winnipeg lawyer Israel Ludwig, who is Slotin's nephew. "When he got drafted into the Manhattan Project, a veil of secrecy came over his work. The family had very little idea what he was doing during that time, which is why it came as such a shock when the accident occurred and the call came saying that my uncle was dying." Slotin accompanied the Manhattan Project team when it moved from Chicago to Oak Ridge, Tenn., and again when it relocated to Los Alamos, N.M. His work with the critical-assembly team led to development of the aforementioned trigger device used in the Trinity bomb. By 1945, he had applied for U.S. citizenship, but he was still considered a foreign national and was not granted security clearance to work on Fat Man and Little Boy, the two bombs which were dropped on Japan. Nevertheless, he remained in Los Alamos and continued his work after the war. He was preparing to leave the program and return to his cancer-research job in Chicago when the accident that took his life occurred. Ludwig said it's important for Slotin's story - and the stories of other Canadians who have had an impact on the history of the past century - to be told. "I think it's important that Canadians know who their heroes are. There's something about us as Canadians - we don't put a lot of emphasis on our heroes, the way Americans do. Our young people don't know much about Canadians who have made sacrifices and who have created history in this country." He added that this film also helps to put into context the story of a man who contributed to what many view as the most terrifying development in human history. "It's important for people to understand how an individual can get into a situation with such tremendous conflicts," he said. "I think it's an important lesson in morality. Here, you have the story of a man who, by the course of history, found himself working on a project that in many ways had very terrible consequences. "He was doing it for all the right reasons - he saw it as a way to help

win the war and defeat the Nazis, which he viewed as the darkest, blackest

force in history - but he was fully aware there was a dark side to what

he was doing. And the accident showed how it could lash back and strike

at you."

|

Created: Friday, April 16, 1999

|

|

|

|

|

|