|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword

I first was made aware of Bender Hamlet by my late father, Jerry, in the late 1970s. Our family went for a day trip to Gimli on the shore of Lake Winnipeg. Before we went home, we took a side trip, 20 km west down a gravel road. The road eventually curved to the north, and where the CNR cut across the gravel road we turned right and travelled another few kilometres. This road was narrow and wet. To the left was range land. To the south was nothing. Or almost nothing. Lines of trees stood away perpendicular to the narrow road. Between and close to the road were many small pits, surrounded by stones and rocks and uncontrolled growth. The land was wet but not swampy. It was as if the land was a saturated sponge. "This," my father told me, "is Bender Hamlet. My father grew up here." I felt a great sense of pride and emotion coming from my father that afternoon. In effect, it was this side trip that sparked my interest in who I was. Where I came from. And who came before me. I was now hooked. For the next twenty odd years I have attempted to research my family, through genealogy and history. It has taken me back to Bender Hamlet and forward to my family. In this respect, my research has covered the scope of history, geography, economics, politics, and my family's history and genealogy. My interest in genealogy has even expanded to include taking part in the initiation of the Genealogical Institute of the Jewish Historical Society of Western Canada although other interests have dominated my time since then. In fact, this document is more than five years in the making. The memories of my first visit to Bender Hamlet will always be remembered as the passing of knowledge from one generation to the next. Midor l'dor. And so, I dedicate this publication to my daughters, Samantha, Elizabeth and Danielle, and all the legacies of Bender Hamlet. Acknowledgements

In researching this topic, I have accessed every source that was I could find, as can be witnessed in my bibliography and credits. Over and above these materials, I must acknowledge the assistance of a few individuals who made everthing possible. The staff of the Jewish Historical Society, Esther Slater and Bonnie Tregebov, for their assistance in obtaining access to the Society's vast resources at the Society's offices and at the Provincial Archives of Manitoba. Quick Chronology

1902 Autumn. The first settlers set to work to build houses. 1903. All the settlers had their own houses. 1910. Only 391 acres had been cleared in the area surrounding the colony, as well two farmers jointly purchased a steam tractor with a gang plow and harrows for breaking and preparing new land, as noted by P. R. A. Belanger in his report. 1915. 39 families and 182 people lived in Bender Hamlet and the surrounding district. 1949. The last building at Bender Hamlet was destroyed by a grass fire. Only the basements remained to mark the former size and location of the houses. Dominion Lands Act 1872

The Dominion Lands Act of 1872 allowed a settler one free quarter-section for a token registration fee of ten dollars. The settler was obliged to improve and work the land after which application for ownership could be made for the original quarter-section within three years as well as any unoccupied quarter-sections adjacent to the original parcel of land. Alexander II and III

The assassination of Czar Alexander II of Russia by a revolutionary's bomb in 1881 was followed by a violent reaction against Russian Jewry. Pogroms had been occurring throughout southwestern Russia. Combined with the introduction and rigorous enforcement of the discriminatory "Temporary Rules" or "May Laws" of 1882, which emposed severe economic, social and political restrictions on Jews, the pogroms led to a massive exodus of Russian Jewry to Western Europe and North America which continued until the onset of the First World War. Jacob Bender

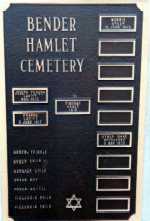

Jacob Bender is believed to have been a land speculator, who at the beginning of the twentieth century was living in Teulon, Manitoba. Bender purchased 160 acres of Manitoba Interlake farmland in February 1902 to serve as the centre of a new farm colony. Bender Colony was to be located as far north as one could travel by road all year round. This particular quarter- section was chosen by Bender because of its availability more than any other reason as other better and more southerly parcels of land were previously claimed due to the popularity of the Dominion Lands Act (DLA) of 1872 for the previous 30 years. Jacob Bender saw an economic potential in the harvest of the forest of trees surrounding the new colony. However, except for isolated stands, most of the prime spruce and tamarack was razed by fire in the 1870s, and most of the secondary cover was of little economic value. One could conclude that Jacob Bender was ignorant of the true value of the land, but he was not alone as the immigrants also believed that if the land could support trees it would support agriculture. Unfortunately, this land in Manitoba's Interlake was mainly suitable for trees and not for cereal grain crops. This quarter-section (NW¼ 36-19-1W) became Bender Hamlet and was divided in to nineteen equal strips one-half mile deep, each the full length of the ¼-section; about eight and one-half acres each running north and south. The Canadian Government gave its permission to Jacob Bender to allow for this subdivision. The fourth lot from the east was used for the Achdus Yeshurun synagogue (shul [synagogue] and cheder [Hebrew school]) at the north end of the lot and the cemetery at the south end of the lot. The beginning for Bender Hamlet was in 1902 as Jacob Bender visited Russia and England to discuss with potential immigrants the possibility of a village settlement emphasizing the advantages of free land the Canadian Government was offering to interested settlers. In England, Jacob Bender was so successful that Rabbi M. B. Dagutski wrote to the Dominion Lands Office to request that Jacob Bender be given the power-of-attorney for potential emigrants from Manchester. It is not clear if any assistance was received from either the Mansion House Committee or the Baron Maurice de Hirsch Foundation. In Russia, where Jews were not permitted to own land, the promise of free land was an even more powerful lure. Jacob Bender's idea of a village settlement (shtetl) was particularly attractive to the Russians, most of whom were from agricultural villages, but not necessarily farmers due to either restriction or vocation. Of the 19 families that arrived at Bender Hamlet in 1902, most came from England and Russia, a few from Winnipeg and one from Boston. As a Jew already living near the proposed settlement Jacob Bender was quickly accepted as a leader in the colony until 1907 when Bender severed all ties to the Hamlet. First Settlers

The Lavitt Family

In the late 1800s the Czar of Russia pushed the Jewish farmers into the larger cities such as Kiev as the Pale of Settlement evolved; Joseph, like many of the oppressed people of his time, took his lot and found his way to England and eventually Canada. Joseph Yehuda Lavitt was born in Ukraine in 1840 and sixteen years later married Charna Brotsky, who was also born in 1840, to avoid the otherwise compulsory 25 years of military service in the Russian Czar's army. With the hope of freedom from oppression, Joseph and 18 other Jewish families settled in the Interlake region of Manitoba in a new colony called Bender. Friedl worked in "yerid" marketplace as a trader in Russia and then as a bookkeeper in a lumbercamp. In England, Freidl was in the creamery business when he heard that land was available in Canada for $10.00. Joseph's son was Friedl Sholom Lavitt. Friedl, his wife Kayla Sosin and their family arrived in Bender in 1902. Friedl and Kayla had an arranged marriage in 1877 to allow Freidl to avoid the otherwise mandatory twenty-five years of service in Czar Nicolas' army. Friedl's oldest two sons Isadore and Alex never stayed at Bender Hamlet. Isadore remained in Winnipeg as his family moved onto Bender Hamlet. Alex stayed in Bender Hamlet a while and then returned to Winnipeg. Harry left Bender Hamlet when he was 17 and Rae left as well. Isadore was a musician and eventually an orchestra leader at the Capitol Theatre and the Orpheum in Winnipeg. In Winnipeg, he met Clara Blizen and together they had 5 children. Clara who was born in Winnipeg in 1889 was one of the first people to be born in Winnipeg. Clara, in a 1972 oral history interview detailed life at Bender Hamlet from her summer visits to the colony as well as her life in Winnipeg and Flin Flon. There was a shul [synagogue], a school, a store and even a mikveh [ritual bath]. The homes were whitewashed log cabins which they bulit themselves. Aside from the regular stove, there was a brick oven built into the house where food was kept warm over the Sabbath. Kashruth [Jewish dietary laws] was strictly observed. Dixon was the shochet [ritual butcher]. Kayla was a good housekeeper; everthing was spotless. She visited Bender Hamlet every summer after she married Isadore. She saw how hard the life was there, and tells how good the milk and cream were. The Lavitts gradually all left Bender, visiting Isadore and Clara at their home on Jarvis and Powers in Winnipeg. The older Lavitts opened a store when they came to Winnipeg. Friedl once walked to Teulon to fetch a doctor when Kayla was delivering twins, although Charna the grandmother had been a midwife in Russia. At one time, Clara, her young sister, Doc Stern's mother and Charna took lunch to the men who were working in the fields. They walked along the main road taking the dog with them. The dog went off to chase a rabbit and suddenly they were face to face with a bear and her cubs. The frightened women all stood still and outstared the bear which finally trotted off. Jack Lavitt stayed in Bender until its breakup. He detailed life in Bender in a 1972 oral history interview. The colony started in 1903. The Jewish people who went to Bender tried to farm, the country was rough, there were no facilities and no railroad. Everthing had to be brought in by oxen or horses. A group of Jews in England contacted the JCA. Recruitng was done in England and Winnipeg. Jacob Bender started it through the Baron de Hirsch Institute. The Lavitts came from England, but were originally from the Ukraine. People didn't know anything about farming. It was a very rough experience. Jacob Bender was a land agent or something. Nineteen families originally at Bender. From the east end: Feldman, Frank Lavitt and J. Lavitt, lot for shul [synagogue], Posen, Gerber, Warshawsky, Weinstock, Fedis, Brodsky, Max Arbor, Nathan Arbor, Green, Dixon (shochet) [ritual butcher], Winogratsky, Joe Gordon, Ludwig, and Ben Gordon. The colony was arranged in a straight row for half a mile. Rest of land was a mile and a half spread out around whole area. The appearance of spruce, tamarack and white poplar made the colonists think it was worth a fortune, but they didn't realize that there was no railway nearby. Originally started with one machine - mower, rake, plough. Everybody would use it. After, they bought their own, some farmers bought them together. Some never stayed too long, left before the First World War as they could not succeed. By 1910, the Lavitts had all their own implements. The buildings were made of spruce logs, intertwined and held together with pins. The produce was hauled by oxen to Teulon, Fraserwood and Gimli and then by rail when the train came. The roads were rough as there was no grading until 1914 or 1915. A journey to Inwood, a distance of 12 miles was done by oxen in 4 hours. A horse took 3 hours. Cattle raising began for cream. The cattle buyers usually bought the cream. A fews cows to begin. Flour was obtained from Greenberg's store in Gimli. Enough wheat was taken to make their flour and some to sell after the freeze up. Matzos for Pesach [Passover] were received from the city. The first log house burnt down. The second house was framed. The meat could only be frozen in the winter. The rural school had 30 children and one teacher for grades one to eight. There was no future for the children there. When the boys had Bar Mitzvahs the whole town would come. Births were registered in Gimli. Dr. Hunter lived in Teulon, 24 miles distant. Charna cooked up concoctions that made you well. The colony was at its height in 1921 and 1922, and started to disintegrate. In the three years of 1924 to 1926, the crops were rained out and the government offered no assistance. Friedl couldn't hold out. The settlers left everything and ownership went back to the government. The Jacobsons and the Warshawskys were some of the last families. The Leverhants left once and came back. Posen had a store at Chatfield, Weinstock at Fisher Branch and Hodgson. The children bought the land their parents owned at Bender. Friedl Lavitt had 8 children, some born at Bender Hamlet, but moved to the larger city of Winnipeg in its boom period. Living in the North End of Winnipeg, cut-off from the rest of the city by the Canadian Pacific Railway Main Yards, the family began its own diaspora across the North American continent. The Leverhant Family

Joseph Leverhant and his four sons homesteaded to the west of Bender Hamlet in 1905. A daughter, Eda, was born on September 5 to Itzak and Sara Leverhant. The Ludwig Family

Hyman Ludwig arrived at Bender Hamlet in 1909 from Winnipeg where he had been tailoring for several years. With him was his wife Sonia and children Becky (10 or 12 years old), and Etta (later changed to Edna) a few years younger. Later in 1909, a son, Albert was born, and in 1911 another son, Morrie was born. The Ludwigs left for Winnipeg in 1917. The railroad and the creamery

The Narcisse Cooperative Creamery and Cheese Factory was to open in 1915 as the settlers were encouraged by the arrival of the rail road. However, it burnt down before it could open. As well, Hyman Winogratsky raised horses for shipment to Montreal via the rail road. A Lavitt dairy herd took off into the bush and stayed out all summer in 1926, denying the family any dairy revenue for the year. Jack Lavitt said in an interview with the Winnipeg Free Press in 1980, "We'd do things wrong. We only fenced in the crop land and not the range land. So the cattle would get away in the bush for long periods." The railway station was built in 1914, two years after the Canadian Northern laid down its line two miles west of Bender Hamlet. A station was built at this site and was dedicated to Narcisse Leven, then the president of the ICA. The Canadian Northern Railway later merged with the Canadian Pacific Trunk Railway and was renamed the Canadian National Railway. The railway tracks remained until late 1990, when the rails were removed leaving a trail of empty ties south to Teulon. The First World War

At the onset of the First World War the Canadian Government urged all farmers to expand their operations to assist in the war effort. Many farmers complied by borrowing to enlarge their planting, often on unsuitable land, and by increasing their livestock; this also made more land necessary, which was purchased with more borrowed money. The sharp decline in grain prices in 1919 and 1920 then forced many farmers out of business. Instead of building up the colonies further, after the war the Jewish Colonization Association (ICA) had to engage in rescue operations to save farmers from bankruptcy. The decline of the colony

There were many factors that resulted in what some of called the "failure" of the colony. As the land was stony and short of water, drinking water had to be hauled by oxcart from a common well. Newcomers ceased to compensate for the losses of people by 1923. Torrential spring rains in 1924, 1925 and 1926 washed out the crops. In November 1926, Jack Lavitt, born on the colony in 1910 was the last of the Bender Hamlet settlers as he left for Winnipeg with his family. It is the isolation, poor soil and decline in grain prices which are blamed for the the "failure" of Bender Hamlet. However, "failure" must be defined before it can be applied to what occurred to Bender Hamlet and the people that lived there. A failure, in its most basest terms is not achieving the desired ends or more generally, a decline or weakening. In respect to the former, Bender Hamlet was a success. The colony allowed scores of immigrant Jews to settle and begin a new life in Canada. To these people, there is no failure. Freedom and the potential for prosperity and self-determination were their own successes. The latter, nevertheless, is true by the simple fact that Bender Hamlet ceased to exist as a living entity, incapable of continuing to support the lives of its former inhabitants. Regardless of this second definition, Bender Hamlet was no failure. Although the colony may have ceased to exist as a location in Manitoba's Interlake, it has not ceased to exist in its legacy of the people who occupied its former confines. No less than a parent does not fail when death comes, Bender Hamlet did not fail when it gave life and hope to scores of people. Rediscovery and dedication

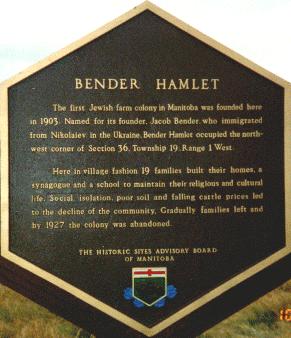

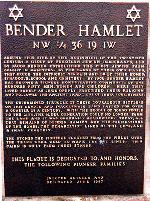

A Crown lands inspector came across the graveyard at Bender Hamlet in 1964, thought "lost" since 1927. The inspector was working on the survey for the soon to be established Narcisse Wildlife Management Area. After the discovery of the graveyard, descendants of Bender Hamlet families were notified by the Government and offered the opportunity to repurchase the land once owned by their ancestors. The work of Joseph Lavitt, grandson of Friedl, to commemorate Bender Hamlet and its pioneers may have had its origins in the early 1960s as he was one of the founders of the Jewish Historical Society of Western Canada (JHS) in 1968. At first, letters were written to gather information about Bender Hamlet and it "descendants". By 1970, the Province of Manitoba had declared Bender Hamlet a historic site. Through the JHS, Joseph organized an oral history committee to interview Jewish pioneers. Some of these oral histories have been used in this document. In 1975, Joseph Lavitt and Jack Walker (Warshawsky) began a process to officially declare Bender Hamlet a historic site. Joseph assembled a list of 300 descendants in the spring of 1986 requesting contributions to erect a marker on a site at Bender Hamlet. In October the plaque at Bender was erected and in the spring of 1987 Joseph sent out invitations to all 300 people to whom he originally wrote, the synagogues and community organizations for the unveiling of the cairn at Bender Hamlet that June. The above, while gathered from the many different sources indicated on my bibliography, remains the intellectual property of myself. You are free to use it for research, education or family, but it may not be published, distributed or re-broadcast in any way, shape or form, without my permission and this notice attached. Please contact me for more information. © 1993-2006 Lawrence D. Lavitt |

|

|

|

|

|

|