Llandaff House (1710-1933)

Llandaff House Academy, 2 Regent Street, Cambridge

Former residence of the Bishop of Llandaff.

Home of the Johnsons from 1823 to 1903.

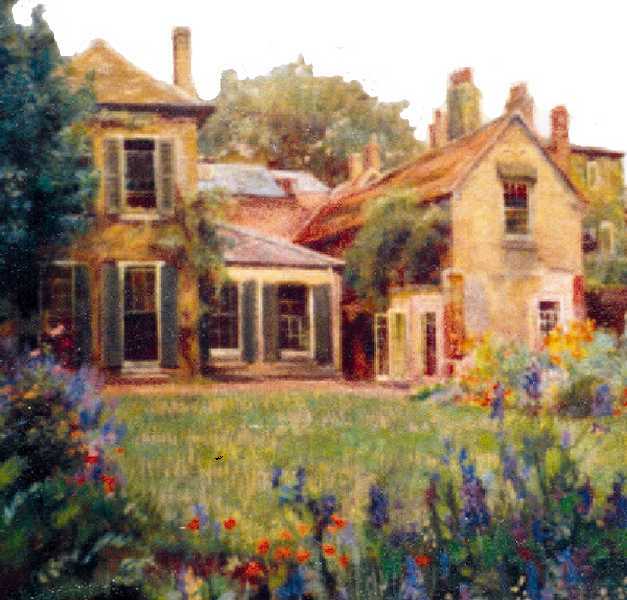

Perhaps overly enhanced images of Llandaff House and garden, from the photos below.

At the back of the garden is the Grove, referred to in the article below.

, 395x300.jpg)

, 405x300.jpg)

From the negatives of photos taken of the paintings of Llandaff House and garden by Nellie Erichsen.

The original paintings are presently owned by Stephen Johnson, great-grandson of William Henry Farthing Johnson.

Robinson's Bicycle Shop and Llandaff House in 1933, just prior to demolition.

[Cambridge Public Library, Cambridge Collection, Print B Reg K2 30904.]

Looking north down St Andrews Street.

[Cambridge Public Library, Cambridge Collection, Print B Reg K2 2340.]

On the left hand side (from closest to furthest): Llandaff House, Police Station (?), St Andrews Baptist Church,

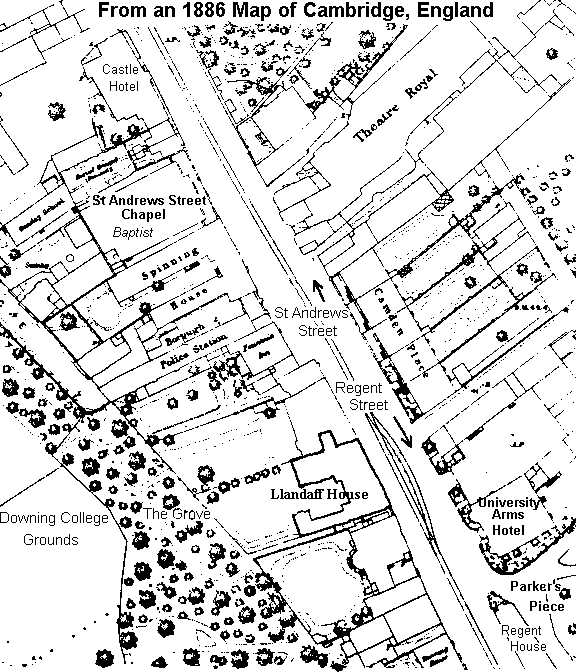

see map below.

[Cambridgeshire Sheet XLVII 2.13, Cambridge Public Library call number XLVII 2.13]

The following article about the history of Llandaff House, was found in the Public Library, Cambridge.

It was originally published in the Cambridge Local History Society Bulletin No. 39, 1984.

The version appearing here was slightly edited, and added to by Micheline Johnson in November 1996.

A Nonconformist School

The Story of

Llandaff House and its Academy,

Regent Street, Cambridge

by Kenneth Parsons

(Archivist, Baptist Church, St. Andrews Street, Cambridge)

1 Lees Way, Girton, Cambridge, CB3 0JR

Tel: 276721

First published in the

Cambridge Local History Society

Bulletin No. 39, 1984

with additions from

Alice Johnson, "George William Johnson"

Edited by Micheline Johnson , November 1996

The University of Cambridge has long acted as a magnet

for those interested in science and mathematics.

It was probably on this account that a young man of twenty-two, named Olinthus Gregory,

[1] settled in

Cambridge towards the end of 1796. Gregory was a native of Yaxley, a small village near Peterborough. He

had been a precocious boy and at an early age had shown a marked predilection for mathematics. In this he

had been encouraged by his schoolmaster and, by the time he was nineteen - this was in 1793 - he had

published a book under the title Lessons, astronomical and philosophical, for the amusement and

instruction of British youth.

The book, which had been well received, brought Gregory to the notice of some students in Cambridge

(among them John Cropley, afterwards MP for the University) who tried to persuade him to enter the

University and take Anglican orders. However, as a Dissenter, he had felt bound to refuse. Nevertheless,

the prospect of working in Cambridge must have had its attractions. There was the prospect of meeting

members of the University and of following up his particular interests in mathematics and astronomy.

Gregory's first job was to act as sub-editor of The Cambridge Intelligencer, a weekly newspaper run by

Benjamin Flower[2], a well-known local Dissenter. This newspaper was more than a local 'rag'. It was radical

in its views, opposing the Napoleonic War, and was 'read, admired and hated', as one person has put it, 'from

the town of Berwick-upon-Tweed to the Land's End in Cornwall'[3].

Flower was a member of the Baptist meeting in St. Andrew's Street. It was his custom to give out the hymns

from the front of the meeting-house and to lead the singing.[4] It is not unnatural, therefore, to find Gregory

attending St. Andrew's Street as his place of worship and making acquaintance with the minister, the famous

preacher, Robert Hall.[5] He himself records the meeting as taking pace in January 1797.

[6] Hall took an

immediate liking to the young man and before long, as we may suppose, was inviting him round to his

lodgings at the east end of Petty Cury. A warm friendship soon developed and, throughout that year, Hall and

Gregory dined together most days - probably at one of the eating-houses in Petty Cury. Later that year,

Gregory was baptised and received into membership of the church.

Towards the end of 1797, a quarrel arose between Hall and Flower over doctrinal matters as a result of which

the later resigned his membership.[7] The break must have put Gregory into an embarrassing position. He

owed loyalty to his employer; nevertheless, his sympathies lay entirely with Hall. Soon after, he resigned his

position on the paper and opened a bookshop in Bridge Street (as it then was) not far from Holy Trinity

Church.[8]

Hall enjoyed the company of his young friend (he was ten years older than Gregory) and now suggested that,

for their mutual improvement, the two got together for an hour each morning during the week; Gregory to

instruct Hall in higher mathematics, while Hall took up with Gregory the subject of metaphysics. These study

sessions, which were conducted by the friends in turn, lasted about a year. Hall's friendship, together with

the discussions that followed, Gregory describes afterwards as 'among my richest blessings' at that time.[9]

Gregory's bookshop flourished. In July 1799, we find him removing to a new site on Market Hill and appealing

to his erstwhile patrons for support. Meanwhile, he had started a new venture. This was a day and evening

school for youngsters held, it would appear, in a room not far from the Market itself. The school had grown

quickly in numbers and, in the same July, he announced that he was about to engage an assistant.[10] These

events mark the beginning, in effect, of the establishment that was later to become Llandaff House Academy.

Gregory's assistant was a man named Newton Bosworth. We know little about him at this stage. Bosworth

was born in Peterborough in 1778, and at age 22 moved to Cambridge in 1800. He was twenty-three years

of age, well-educated (having probably attended a seminary in London) and, like Gregory, held Baptist views.

The arrangement appears to have been that Bosworth took charge of the younger boys while Gregory

concentrated on tutorial work, especially the teaching of mathematics. Finding teaching more profitable than

bookselling, Gregory soon gave up the bookshop altogether.

We have already mentioned that Gregory was author of a book.

A second edition was called for that year,

i.e., in 1799, and he now began work on another book to be entitled A treatise on astronomy. This was

completed in 1801, but not published until the following year. On the title-page he grandly describes himself

'Teacher of Mathematics, Cambridge'. The preface to this book carries a note saying 'the treatise was

composed during the intervals of leisure which could be snatched from the employment of a large school, an

employment which requires the author's persevering attention for more than eight hours a day'. But this was

not all. Gregory, Bosworth, and another man whose name we do not know, embarked on an ambitious plan

to produce a new encyclopedia.[11] Unfortunately, the plan ran into difficulties. Their collaborator withdrew and

had to be replaced. However, a new collaborator was found and the work was eventually completed in 1813

in 12 volumes. Pantologia was its name and, for many years, it served as an important reference work of

its kind.

Throughout these years, busy as they were, Gregory maintained close relations with Robert Hall, whose

company he often shared during the week. Bosworth also was admitted to the circle of Hall's friends. It must

have been a shock, therefore, when Gregory announced that he had obtained a post at the Royal Military

Academy, Woolwich, and would be leaving Cambridge for good early in 1803. From this time onward Gregory

drops out of our story. He was to become eventually Professor of Mathematicians at Woolwich Academy and

one of the country's leading mathematicians. He was one of the projectors, in later years, of London

University - the fourth university to be established in this country after Oxford, Cambridge and Durham.

Following Gregory's departure, Bosworth took over the running of the school. This was located at that time

in a building overlooking All Saints churchyard.[12]

Bosworth was a man of outstanding charm and personality. A contemporary has described him as 'learned,

accomplished and amiable'.[13] There was much poverty in Cambridge in those days and, in 1801, a group of

friends belonging to various churches got together to form a Benevolent Society for the relief of the sick and

aged poor. Funds, it was agreed, should be raised by means of subscriptions and donations, and from a

collection taken at a sermon to be preached annually in one or other of the local churches, Anglican or

nonconformist. The prime mover was Mrs. Eliza Flower (wife of Benjamin Flower, already mentioned) who

became its first secretary.[14] Robert Hall wrote the

prospectus[15] and Bosworth was evidently one of its keen

supporters. When the Flowers left Cambridge in 1804, Bosworth became the new secretary - an office he

continued to hold for many years.[16] His wife,

Catharine, was installed as one of the visitors.

In March, 1807, Bosworth announced[17]

that he would shortly be opening a boarding school for young

gentlemen in what he called 'a commodious house and in a pleasant and airy situation'. This house, now in

the possession of St. John's College, was called Merton Hall. It stands adjacent to the famous School of

Pythagoras in Northampton Street. It may be of interest to quote from the advertisement:

"Board and education in the English, Latin and Greek languages, writing, arithmetic, and

mathematics, with their application to book-keeping, surveying, geography, globes, etc., or such of

these as may be deemed most suitable for the pupil, THIRTY GUINEAS per annum. Entrance, one

guinea.

Tea in the afternoon, when desired, half-a-guinea per quarter additional ....

Washing and mending may be conveniently done in the town, and will be regularly attended to by Mrs.

Bosworth.

Music, drawing, French, etc., by the best masters.

The health, morals and religious instruction of the pupils will be objects of constant attention."

[18]

Later that year, Mr. and Mrs. Bosworth joined with others in starting an undenominational

Sunday school[19] on

a site in Sidney Street now occupied by Messrs Woolworth's store. This school, which was supported by both

Anglicans and nonconformists, attracted about 40 children. It began at 9 a.m. and, at the close of lessons,

the children were marched through the streets to their respective churches or chapels to attend morning

service. The school re-assembled in the afternoon. In 1810, the school broke up to form separate Sunday

schools at the churches or chapels concerned. One scholar to attend this early Sunday school was John

Pink,[20] father of John Pink, the first Borough Librarian, whose portrait may be seen hanging in the room

occupied by the Cambridgeshire Collection in the city's Central Library.

By 1811, Bosworth's school, or academy as it was now styled, had so increased in numbers that a full-time

assistant became necessary. The young man to be engaged was William Johnson,[21]

a native of Ramsey in Huntingdonshire. Johnson stayed for about three years, then returned to Ramsey to open a school of his own.

About 1816, he married Miss Eliza Barker, a schoolmistress some years older than himself.

Meanwhile, Bosworth obtained offer, in 1817,

[22] of a property in Regent Street called Llandaff House. The

older part of this house (which dated from 1710) had at one time been a tavern bearing the sign "Bishop

Blaize". In 1784, Dr. Watson, Bishop of Llandaff,[23] had

acquired the tavern, added an annexe and extra

rooms at the back, and turned the whole into his private residence. One may ask what the Bishop of Llandaff

was doing in Cambridge. The answer is that, like other ecclesiastics of his day, he was a pluralist. Not only

was he Bishop of Llandaff, but Regius Professor of Divinity in the University as well, besides holding two

benefices in other parts of the country. Although a very able man, and in some ways an enlightened one, he

was not a popular figure. An epigram circulating at the time ran thus:

"Two of a trade can ne'er agree,

No proverb can be juster;

They've ta'en Bishop Blaize, you see,

And put up Bishop Bluster"[24]

Watson was a man of considerable scientific attainments and liberal political principles, chiefly known for his

Apology for the Bible, written in answer to Thomas Paine's Age of Reason; and the earlier Apology for

Christianity, in answer to Gibbon's attacks on Christianity in the Decline and Fall of the Roman

Empire.[3]

Not only was Watson the Bishop of Llandaff, but he held two benefices in other parts of the country. This

pluralism was common amongst ecclesiastics of his day[14]. In Canada, for example, country ministers were

not paid until the late 19th century, and had to find other sources of income. Bosworth, who late emigrated

to Canada, supported himself and his family, with the help of his son, from the proceeds of his farm.

Llandaff House was commodious and eminently suitable for use as a school. Besides that, it was near

Parker's Piece - good for team games - and close to the Baptist meeting of which Bosworth had been deacon

now for six years. At the back were fields, part of Downing College grounds, and a rented garden known as

'the Grove', where the younger boys could play. Features of the building were the pillared porch, jutting out

over the pavement and, inside, a beautiful oak staircase and gallery, as well as panelled rooms.

Bosworth carried on the school - now dignified by the title "Llandaff House Academy" - for six years. By 1823,

the burden of the work appears to have become too much for him. The boarders were given up and the

Academy reverted to a day school instead.[25] Early that Summer, he announced that he would shortly be

removing to London and that the school was being taken over by his former assistant, Mr. William Johnson

(1793-1871).[26] The property thus acquired remained in the hands of the Johnson family for close on 80 years.

Bosworth moved to Totenham in London, but dissatisfied with that living, decided at the age of 56, to emigrate

to Canada in 1834. He settled in York Mills, 8 miles north of Toronto (Yonge St). From 1835 to 1837, he was

minister of the St Helen St Church in Montreal. In 1839, he published Hochelaga Depicta, a pictorial

description of all the major buildings in Montreal at that time, together with a description of the uprising that

occured east of Montreal that year. During 1839 to 1843 he travelled as a touring minister, spending part of

that time on his son's farm at Trafalgar just west of Toronto). On 16 Dec 1841, Bosworth wrote from Trafalgar

to Mrs Olinthus Gregory, on the death of her husband, promising to document for her his recollections of the

earlier part of the life of his friend Olinthus Gregory, who had started the school that Bosworth took over. This

letter and an extensive diary written by Bosworth are in the archives at the Baptist Divinity School at McMaster

University, in Hamilton. In Feb 1843, Bosworth became pastor of the Baptist church in Woodstock (then

Oxford), Ontario. In 1845, following a disagreement with his parishioners, he moved to a job as minister of

Paris, Ontario, where he died in 1848, aged 70 years.

William Johnson's grand-daughter, Alice Johnson (1860-1940), who was born and brought up in Llandaff

House, described it as follows[21]:

It was a large, rambling old house, - the earliest part, with a beautiful wide staircase and

gallery and panelled rooms, dating back probably to Queen Anne; - originally the last house

on the south-east exit from the town. The pillared porch extending over the pavement once

bore great extinguishers, such as are still retained as ornaments on the porches of some old

London houses, wherewith to put out the torches of link-boys escorting travellers into the

town at night. There was a low railing of posts connected by chains in front of this oldest part

of the house.

The garden at the back led into the semi-private grounds of Downing College, now mostly

built over, but in our childhood an open space about a third of a mile long with fields and trees

haunted by rooks and many other birds. Our garden opened on to one part, the much-loved

" Grove," to which only we and our next-door neighbours had access.

The house had gone through many changes at the hands of its different owners. The Bishop

had added a wing consisting of two largo and lofty rooms, one on each floor, looking on to

the garden, and in the ground-floor room had built a spacious book-case of fine proportions,

which remained one of the treasures of his successors, and was regarded with special

veneration by the children, to whom he was a semi-mythical hero. This the living-room and

best room of the house-always kept its ancient name, The Parlour, the word " drawing-room

" being thought by us slightly vulgar and pretentious.

Adjoining the Bishop's rooms was a yard with cloisters on two sides of it, a delightful place

for games in bad weather. The big schoolroom, looking out on to the garden and yard, was

over one of the cloisters and a sort of rabbit-warren of offices beyond.

In the kitchen was a pump which supplied drinking water for the house, supposed in our

childhood to be superior in all respects to the waterworks water. One of my earliest

recollections is seeing enormous joints for the school dinners roasting on the spit turning

before the great open fire. A hatchway opened from the kitchen dresser into the dining-room,

which had originally been the Bishop's coach-house, and later a sweetshop, kept by an old

man named Fuller. It was rumoured that the boys in the bedroom above used to let down

a basket in the dead of night for surreptitious trading in sweets with this old man.

Our grandfather divided the older part of the house from the rest, and let it for a girls' school,

the relation of which to his own was somewhat like that of the two adjoining schools in

Villette. He also made a passage on the upper floor, giving separate access to rooms which

originally opened into one another. The rooms on both floors were on different levels, with

steps up and down everywhere, besides the regular staircases. And there were great deep

cupboards, long passages between the attic walls and the walls of the house, entered by

trap-doors, big lofts and other spaces, in which several persons might have been hidden for

days without the knowledge of the household. This gave an air of mystery and romance to

the house, especially in the eyes of the children. There were regions into which they seldom

or never penetrated, - of uncertain, and perhaps unlimited extent - and most of them believed

in the existence of at least one "secret room", though there was no general tradition as to

where it was situated.

Such a house, with the accumulated traditions and associations handed on from one

generation to another, comes to play a part in the life of its inmates hardly conceivable to

families that are always changing their abode. Each room and each region takes on an

individual - almost a human-character of its own; it may be loved or hated; admired,

respected, despised, or feared; it can never be regarded with indifference.

William Johnson's objective, like that of his predecessors, was to provide a high-class education. An

advertisement in the local paper in 1829 reads as follows:

"Any gentlemen working to prepare for the university will find in this establishment every

requisite to assist him in the prosecution of his studies, as well as every domestic

arrangement calculated to promote his comfort.[27]

The boarding school was re-established and, by the 1830s, we have evidence to show that the number of

pupils had risen to about fifty.[28] In 1830, Johnson

delivered a lecture to friends and supporters of his

academy, including we are told the University Professors of Greek, Arabic and Natural Philosophy, explaining

his system of education. This was afterwards published in the form of a pamphlet entitled Thoughts on

education[39], part of which is reproduced below.

The pamphlet contains an advertisement showing that the basic cost of board and tuition was

still 30 guineas per annum. However, this figure was doubled for 'parlour boarders', i.e., pupils living with the

family, whilst the charge for private pupils, including a separate study and bedroom, was 80 guineas per

annum.

The academy's nonconformist tradition continued. Johnson himself joined the Baptist church in 1832. His

wife, although a regular attendant, appears to have been less committed. The couple had four children - three

sons and a daughter - all of whom were brought up in the academy. The eldest son died suddenly in 1841.

Mrs. Johnson died also the following year. A headstone to the memory of these two members of the family

stands in the small graveyard attached to the church.[40]

Of the other children, the only one to concern us is the second son, William Henry Farthing Johnson (or WHF

as we shall call him), born at Llandaff House in 1825. WHF went in 1841 as assistant master to a school in

Brixton. He was only sixteen, but it was of course usual in those days for boys to commence their careers

at an early age. The work was strenuous, as, owing to the indolent disposition of the head, WHF was left

practically in charge of the school, and the older boys (who were about his own age) naturally tried to defy his

authority, and drove him to the use of his fists. Fortunately, he was big and strong, as well as determined, and

soon succeeded in reducing them to order. But he had also a boyish sympathy for boys, and though only

there for six months established the most friendly relations with them. They nicknamed him "Mr. Elephant"

and after he left sent him affectionate letters of quite unconventional type.

[29]

On return to Cambridge, WHF taught for a while in his father's school. In 1843, he entered Corpus Christi

College as an undergraduate. The College had been willing to accept him, but on completion of his studies

and having passed the examination, he was precluded from taking a degree because of the University Tests.

He had in fact joined the Baptist church in 1845 and could not in conscience subscribe to something in which

he did not believe.

Upon leaving college, WHF returned to his father's school as assistant master. Four years later, in 1851, he

married Harriet Brimley, a young woman belonging to one of the church families. The elder Johnson now

retired to his native Ramsey and the son took over the headship instead.

Harriet Brimley was well connected. Her father, Augustine G. Brimley, was a prosperous grocer living on

Market Hill. He was keenly interested in civic affairs and became Mayor of the Borough in 1853-54. Harriet's

two sisters were also well established locally. Caroline, the elder, was wife of Alexander Macmillan, one of

the founders of the now famous publishing firm; while Fanny, the younger, was wife of Robert Bowes,

proprietor of the Cambridge bookshop now known as Bowes and Bowes.

Harriet herself was a gifted woman. One of her daughters writes of her thus: "She was a great lover of poetry

and a beautiful reader. Men of letters were her chief heroes ... In the severe frugality of her married

household, new books rarely entered the house except as birthday or Christmas presents, but our father

generally managed to give each new volume of Tennyson as it came out. Next to Tennyson she loved

Wordsworth and named her eldest daughter after his 'Lucy'. For long she acted as matron and at first taught

regularly in the school till forced to give up by the cares of housekeeping and a growing family (she had eight

children) which had to be brought up on very limited means. She continued, however, for many years to take

occasional pupils in German and Latin."[30]

The census returns of 1851[31]

show that the academy at that time took in 25 borders. There were probably

at least as many day boys as well. Most of the boarders - about two-thirds - came from towns and villages

in Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire; the remainder from places slightly further away. A list of old boys -

"Old Johnsonians" as they called themselves - drawn up in 1903, shows on investigation a great variety of

backgrounds and occupations. Farmers and small business men seem to predominate, but there is also a

fair sprinkling of professional men - clergymen (both Anglican and nonconformists), doctors, barristers,

solicitors, schoolmasters, and even a handful of Cambridge University dons. Among the names to occur are

those of Frederick and Maurice Macmillan, sons of Daniel Macmillan, the latter Maurice being father of Harold

Macmillan (now Lord Stockton) a former Prime Minister.[32]

WHF had the distinction of being one of the first two nonconformists to be granted a Cambridge B.A. degree.

This took place in October 1856, following an enabling Act of Parliament passed the previous July.[33]

Five years later, he migrated to Trinity and obtained his M.A. These degrees, in fact, were titular only. It was not

until 1871 that University Tests were abolished and nonconformists were allowed to take their place in the

Senate and to compete for University offices and posts.[34]

WHF served as headmaster of Llandaff House School (as it was afterwards styled) for 42 years. He was no

cold academic. Tall and well-built, he entered fully into the lives of his pupils, sharing their games and

pastimes and playing cricket with them when opportunity occurred. He was active in young people's work of

all kinds. One of the founders of the Cambridge Y.M.C.A., he served as its first President in 1852. Again, in

later years, he became the first President of the Cambridgeshire Sunday School Union. At the Baptist church,

he was deacon (later senior deacon) for 45 years. In public affairs, he served as a Justice of the

Peace.[35]

In 1875, The Post Office Directory of Cambridgeshire lists:

Johnson, Wm. Hy. Farthing, school for gentlemen, 2 Regent st

At the age of sixty-eight (this was in 1893), WHF felt it time to retire. The boys school was given up and his

eldest daughter, Harriet, with the help of her cousin, Janet Bowes, opened a mixed preparatory school for

younger children. It was to this school that Maynard and Geoffrey Keynes went as youngsters in the 1890s.

Their mother, Mrs. Florence Keynes (in her book, Gathering up the threads, p.65) recalls the feuding that

went on with certain errand boys in their journeys across Parker's Piece!

In July 1901, the old man - now seventy-six years of age - died. The reporter who wrote his obituary in the

local paper says 'quite a number of well-known public men in the town and country passed through his hands,

and the influence of such a personality has repeatedly shown its effect in their lives; a large percentage of the

yeoman class in the country will lament the loss of their old master'.[36]

Alice Johnson wrote[21]:

Perhaps our strongest feelings were excited by the Grove, which gave beauty and dignity to

the house. We clung to it with all the more passionate affection because, since it was on a

separate tenure, there was always the fear that we might be deprived of it. This fear

especially haunted our father, who had an almost religious devotion to the Grove. The

Downing grounds were gradually built on towards the end of his life; but we were thankful

that the greater part of it remained intact up to the time of his death, in 1901. When he died,

his coffin was carried out through the garden and Grove on its way to the back entrance the

chapel where funeral service was held.

It was about this time that the Baptist chapel, which WHF had so long attended, was declared unsafe. A fund

was started to build a new one the result of which was the erection of the present edifice in 1903. A number

of former pupils of Llandaff House School got together to raise a memorial to their old master. This took the

form of the fine pulpit which now adorns the building and from which

so many well-known men (including our Billy Graham) have preached over the years.

In 1903, Llandaff House was sold to Mr. Herbert Robinson (father of David Robinson, the multi-millionaire)

who converted part of it to his cycle business. The older portion, which had been let off some years previously

as offices and re-named Llandaff Chambers, was left as it was. In 1932-33, the entire property was

demolished and replaced by the buildings we have today. The monogram HR above the new 'Llandaff

Chambers' identifies the spot upon which the old tavern once stood.

Following the break-up of the family home in 1902, Harriet Johnson (later wife of Mr. Arthur Berry, Vice-Provost of King's College), removed her school to a temporary situation in Grange Road. From thence it was

transferred in 1907 to a newly-built schoolhouse in Millington Road. In 1925, she retired and Miss. Mary Tilley,

a former pupil and a graduate of Newnham, took charge.[37] At the time of the demolition in Regent Street, the

school was re-named "Llandaff School'.[38] Miss. Tilley left Cambridge in 1941 and the school came under new

management, but it is interesting to note that it still exists under the title of the 'Millington Road Nursery

School'.

Three of Mr. Johnson's family - Mr. W.E. Johnson and the Misses Alice and Fanny Johnson -- lived for many

years in a house on Barton Road at the corner of Millington Road. Aptly, this was named "Ramsey House"

after their grandfather's birth-place, and so it still remains.

In 1830, William Johnson, the father of WHF Johnson, who also ran the school at Llandaff house,

published a pamphlet[39] promoting the school.

An extract from the pamphlet, showing its tone, is included below:

:

THOUGHTS

ON

EDUCATION:

AN

ADDRESS

DELIVERED TO THE

FRIENDS AND SUPPORTERS

OF

Llandaff=House Academy,

REGENT STREET

CAMBRIDGE

LONDON:

PRINTED BY W. TEW,

34, Queen Street, Cheapside, near Southwark Bridge.

SOLD BY SIMPKIN & MARSHALL, STATIONERS' COURT,

LONDON; AND STEVENSON, CAMBRIDGE.

1830

PREFACE.

The substance of this small publication was recently delivered, in the form of a Lecture, to the

friends of my Establishment, nor was any thing further originally contemplated. Encouraged

however, by its favourable reception, as well as by the opinion of several eminent Members of the

University, who honored me with their attendance on that occasion, I have ventured to give it more

extended publicity through the medium of the press.

The method of reading the Classics, described in page 20, &c., I have found, after a trial of nearly

twelve months, to be very successful. It was introduced into my Academy by my friend, Mr. John

Bligh, who has assisted me in conducting the Classical department during that period, and also in

preparing the following statement of our plans.

It only remains for me to say, that we are convinced of our liability to err, in adverting to topics so

numerous, and admitting of so much difference of opinion, as those contained in the following

pages: I am, however, willing to hope, that while parts of the system may be open to objection, or

susceptible of improvement, the general tendency of the whole is such as will secure the approbation

of those numerous Friends who have so kindly encouraged the publication of this small Treatise.

W. JOHNSON.

Llandaff House Academy,

Regent Street, July 10, 1830.

ADDRESS, &C.

The subject of the present Address is one of the most important that can occupy the attention of the

human mind--the Education of Youth; and though it is usual to restrict the meaning of the term to

that process of mental discipline, which prepares young persons for their future destination in this

world; yet, as man is immortal, and as his residence here is as nothing compared to his existence

hereafter, it is surely most desirable, and in the highest degree rational, to extend the application of

the term to the whole duration of his being.

To point out therefore, its nature and objects, and to specify what portion of time may fairly be

devoted to each branch of study, according to its relative importance, will be the design of the

following observations.

The design of Education may be considered as two-fold, viz. to fit youth for this world and the next;

the one requiring more particularly an intellectual, the other a moral training; of these, the

intellectual must chiefly be regarded as valuable, in proportion as it coincides with the moral, and

is preparatory to it.

I. The first object of education, which is to fit youth for the service of society, will

comprehend three subordinate ones; to impart, first, that practical knowledge, which will directly

contribute to the attainment of an honourable subsistence in life; secondly, that particular

information, which will more especially tend to exercise and call forth the intellect; thirdly, the

minor accomplishments, which, although they form no part of our necessary duties, are nevertheless

of considerable importance with reference to the well-being of society.

1. The first of these subdivisions will include Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic. And although

these are, in many schools, the chief objects of attention on the part of the Instructor, and of

solicitude on that of the Parent; yet we have always found, that a sufficient progress in them may be

obtained, without that loss of time, which, to the sacrifice of higher attainments, is often incurred,

provided only that the Pupil be early initiated, and continue under the same Teacher, during the

principal part of his Studies. It would be a difficult question to solve, whether more injury be

inflicted on youth by the incapacity of their Instructors, or by the caprice of their Parents. Education

is too generally subjected to casual, irregular, and sometimes diverse impulses. Its termination in

such cases will have no systematic connexion with its beginning, nor, in fact, any one stage with

another; and rare are the instances, where the experiment has been fairly tried, of the efficacy of an

uninterrupted course of systematic training, preserving throughout a direct relation to its ultimate

design.

The art of Reading is generally considered so unimportant, as to deserve but little attention on the

part of the Instructor, or little skill in the method of communicating it; and hence has generally arisen

that monotony of tone, or that precipitancy of utterance, which we frequently find in persons of

acknowledged learning and talent. This, however, in our opinion, is a matter of primary importance,

and "were there no other benefits resulting from reading well, then the necessity under which it lays

us, of ascertaining the precise meaning of what we read, and the habit thence acquired of doing this

with facility, these would afford a sufficient compensation for all the labour we could bestow upon

the subject." In teaching beginners, then, if due care were taken to exclude all books which are

naturally above their comprehension, and to explain those which are not, their ability to read well,

would keep pace with the progress of their understandings. Having selected a suitable book, we

should make it a point to require from them only a small portion at a time; and to see that they

thoroughly understand it; and then if they are allowed and taught to follow nature in their tone, they

will seldom fail to read with propriety. The more difficult task, however, is, to correct a confirmed

habit of bad reading. That this will require considerable time will be obvious to all, who reflect, that

the progress of the human mind, is in every case, slow and gradual, particularly so, where ground

is to be retraced. Instead, however, of discouraging such a Pupil with an unpleasing recital of all his

faults at one time, such as, his precipitancy, indistinctness, inaccuracy of pronunciation, incorrectness

of pause, emphasis, or tone, we ought to fix on the most prominent, and to take no further notice of

the rest, till that be in some measure corrected. Our attention may then be directed to the next most

glaring defect. It now only remains for us to observe on this head, that to remedy those errors,

example will be more efficacious than precept; and that the best way to expose and correct a vicious

habit, is to contract it with a just one.

With respect to Writing, though it would not be difficult to lay down a considerable number of rules

for its acquirement, we have found, from long experience, that a strict attention to uniformity of slope

and distance, includes almost all that is requisite for the assistance of the Pupil. Having explained

the meaning of our terms (a practice which ought never to be lost sight of in elementary instruction),

we lay particular stress on the necessity of their application, and in no instance should we omit to

notice a deviation from it. The Pupils, once aware of this severity of criticism on the part of the

Master, will soon learn to examine for themselves.

Nor can any thing be more easy or obvious than the method we adopt, in order to induce this habit.

As soon, for example, as the first line is written, the Pupil should be diligently taught to compare it

with the original, and if he discover any inequality in point of distance or slope, every effort must

be made to avoid the repetition of it in the subsequent line; and thus, by comparing one line with

another throughout the whole copy, he will immediately see whether each letter falls under its

corresponding one; if not, he will be convinced of his own faults; and consequently will perceive the

necessity of cooperating with the Master in his endeavours to correct them. Hence we infer the

necessity of doing every thing in which Writing is concerned, correctly and methodically; and thus,

by an undeviating adherence to one principle, to make it bear immediately upon the mental faculties,

and to produce a habit of neatness and order, which will seldom fail to carry itself into the other and

higher branches of Education, as well as into the concerns of life.

At the close of this evening, a few specimens of our Pupils' productions will be submitted to the

inspection of the present Company; who will have the goodness to observe, that little pains have

been taken to cover their deficiencies by superfluous embellishments; and, that if the penmanship

be not characterized by the finished elegance of a writing-master, the general execution is marked

by a legibility and neatness, which do not yield to it in practical utility, and which far surpass it as

an index of character. We shall offer no apology for attaching so much importance to legibility;

although it has long seemed to be a maxim with a certain class, that to write legibly is a plebeian

accomplishment, and beneath the attention of a lady or a gentleman. Such a maxim, surely, could

only have originated in a politic desire to conceal their own ignorance of orthography, by adopting

emblems to express their sentiments, not less unintelligible and difficult to decipher, than the

Hieroglyphics of the Ancients.

Arithmetic is, in the next place, a branch of Learning so justly appreciated, that it will be perfectly

unnecessary here to add any remarks to those, which have already appeared on this topic. With

respect to the time to be devoted to these studies, viz. Reading, Writing and Arithmetic, we find they

may fairly claim four out of the eight hours which are daily devoted to study; hence it will appear,

that one half of the stated time for Instruction is devoted to the attainment of the first subordinate end

of secular education, viz. the preparation of youth for commercial occupation in future life.

2. The second subordinate end of secular Education, which we stated to be, to impart a taste

for such knowledge as is calculated to expand the intellect, includes chiefly the ancient and modern

Classics, History, Geography, and the Mathematics. It is, we believe, a fundamental error in the

common modes of Education, that these subjects are brought to bear so much more upon the memory

than upon the intellect.

In Geography and History, for example, little is generally acquired beyond a rudis indigestaque

moles of dry facts, and the ability to repeat a long monotonous catalogue of places, persons, and

dates; and this is considered the most satisfactory proof of proficiency; whereas it is not only

possible, but even highly probable, that the Pupil has exhausted the Geographical nomenclature of

the Earth, without gaining any clear conception of its actual condition--the records of History,

without drawing one practical inference--and the Diary of Time, without acquiring any clear view

of the progress of the human species in civilization and religion. The seed has been scattered, but

has taken no root: much information has been given, but little knowledge acquired. On the contrary,

it will always be our chief endeavour to give to all these subjects, a specific bearing upon the

intellect. In Geography we commence with a general outline, which is progressively filled up as the

Pupil advances. His attention is directed rather to the relative position, magnitudes and climate of

the national divisions of the earth, and to the religion, government, and social character of their

respective inhabitants*, than to the names of the places included in those divisions. These names,

we think, may be best acquired indirectly, by a frequent reference to maps, and by an occasional

construction of them. And as we suffer nothing to be committed to memory, which has not first been

commended to the judgement, we make it an invariable rule, to introduce each fresh lesson, with

familiar explanations of all the complex terms it may happen to contain; and, in this way, we often

find that a lesson of Geography, or History, or even of the simplest catechism, may be made the

medium of inculcating principles of practical wisdom, of introducing clear and distinct conceptions,

in the place of vague notions, and, in short, of leading to habits of individual thought. Such abstract

terms as genius, inconstancy, pride, vanity, temperance, superstition, austerity, policy, patriotism,

&c., which often occur in a geographical estimate of national character, are very apt to slip through

the minds, not of children only, but even of adults, without bringing any distinct notion along with

them; and thus it is, that a knowledge of words is substituted for that of things, and the memory

exercised, to the prejudice of the understanding. It would be idle for us to specify all the benefits

which must accrue from a right apprehension of such terms. As the ambiguity which attaches to

them, is perhaps one of the primary sources of error, we have often been gratified by the thought, that

our familiar explanations may probably be the means of preserving our Pupils from many an

erroneous opinion, and unprofitable dispute, in after life, and of contributing in some degree to a

right decision on the most momentous of all questions.

In History, we would labor to fix the attention of the Pupil, rather on the motives, exciting causes

and results, than on the mere circumstantials of actions and events; and in Chronology, on the

contemporary genius, civilization, and power of respective countries, at any given period, than on

the precise dates of isolated occurrences. A parish register would afford as clear an insight into the

character and condition of its inhabitants, as much of what has been treasured up as erudition does,

into those of antiquity.

It is also our endeavour, as much as possible, to bring the plan of induction to bear upon the records

of History.

We give our Pupils a general principle, and require them to adduce accordant facts; such an one, for

example, as, that Strength of Character consists in the habitual preference of the future to the present;

Weakness of Character, in the habitual preference of the present to the future. This principle, which

is a sort of touch-stone of individual and national character, we bid them carry with them into all

their historical surveys, as well as into all their observations upon living society. A principle like

this, will "grow with their growth, and strengthen with their strength;" its circle of accordant facts

may be small at first, but every additional page of History, every new prospect of human nature, will

enlarge its circumference, until it comprise all that appertains to Time, and conduct them to the

sublime conclusion, that Eternity is the only legitimate futurity of a rational intelligence. A principle

like this, comprehends alike the vast and the little--it points out to the opening minds, on the one

hand, the moral weakness of the nations, whose passions were exclusively enlisted in the service of

immediate gratification; and, on the other, that of the school-boy, who lavishes the resources of

months of futurity on the enjoyment of the passing hour. It marks the difference betwixt the heroism

of the Pagan, and that of the Christian Martyr; ......[p.10, para 2, in the original]

[The original goes on in a similar vein for another 31pp. At the back of the pamphlet is a list of

Subscribers, including the former owner of the school: Mr Newton Bosworth of Hackney; Mr

Brimley of Market-hill [Cambridge]; Mr John Nutter and Mr Thomas Nutter, both of Bridge-street;

... etc.

"Mr Brimley of Market-hill" is probably Augustine Gutteridge Brimley (1795-1862), father of

Harriet Brimley who married WHF Johnson. Kenneth Parsons (in the first article above) describes him as

"Augustine G. Brimley was a prosperous grocer living on Market Hill. He was keenly interested in civic affairs

and became Mayor of the Borough in 1853-54".

The pamphlet ends with the following advertisement:]

W. JOHNSON's ESTABLISHMENT unites the several advantages of public and

private Instruction, and his system of Education combines the study of the Latin and Greek

Languages, with a proportionate attention to Reading, Writing, Arithmetic (in all its branches),

History, Geography, English Composition, Algebra and Euclid, or such of these as may be most

appropriate for the Pupil.

Terms

For Board and Tuition, THIRTY GUINEAS per Annum. Or, including

Lessons, Books and Stationary,

with the use of Library, Globes, Maps, Instruments, &c. &c. .............................. 40 Guineas per Ann.

Parlour Boarders ................................................................................ 60 Guineas per Ann.

Private Pupils, requiring a separate Study and Bed-room ..................... 80 Guineas per Ann.

TEW, Printer,34, Queen-street, Cheapside, London

|