|

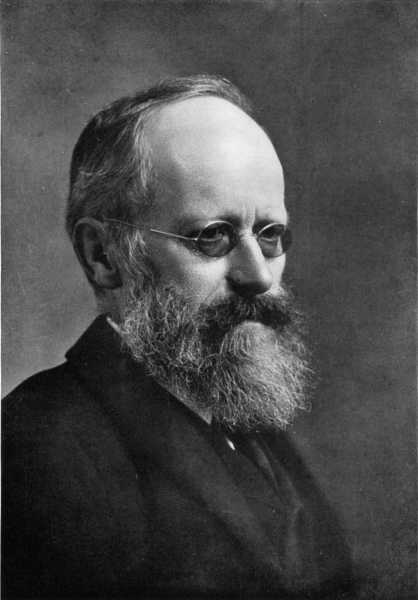

The above photograph of George William Johnson is taken from his book "The Evolution of Woman,

from subjection to comradeship", published in 1926 by Robert Holden, London.

The following short biography on George William Johnson appeared as a memoir at the front of the book.

GWJ finished the book, but did not live to see it published.

The memoir was compiled with the help of various friends and relations, to whom the compilers desired to express their thanks. The actual

quotations - except where otherwise indicated - are taken from the many letters and appreciations received at the time of the author's

death. A more detailed biography may be found in the book by his sister, Alice Johnson, "George William Johnson, civil servant and

social worker", published in 1927 for private circulation, in Cambridge.

EARLY DAYS AT CAMBRIDGE

GEORGE WILLIAM JOHNSON was born July 5, 1857, in the historic Llandaff House, Cambridge (residence of the once-famous Dr.

Watson, Bishop of Llandaff), to an inheritance of upright, liberal Nonconformity, tempered by a keen love for literature and a typically

English enthusiasm for games and politics. The deeply personal religion of his parents in a home neither sanctimonious nor

pharisaical, together with an inheritance of scholastic and academic tradition, tended to direct his thoughts and conduct towards the

moral and intellectual welfare of his fellow-men.

These were fighting days for Dissent, when, if no longer persecuted for their opinions, men who could not conform to the Established

Church were shut out from many preferments or handicapped in their choice of professions, and socially held of little or no account.

His father, W. H. F. Johnson, the second dissenter to receive a degree at Cambridge, had to wait a further ten years for admission to

the Senate; his uncle, George Brimley, had been vigorously urging the abolition of all "Tests" in the Spectator; the minister of their

family (Baptist) chapel had been imprisoned for refusing to pay church rates.

Years afterwards a friend wrote "I was brought up in Anglicanism, and in the theory that there was no church or religion in England

except Anglicanism. . . . George was the first nonconformist of enlightened literary and artistic tastes with whom I ever came into close

contact," who "contributed to my education by enabling me to appreciate properly the religious balance of England."

The later movement in the universities to secure for women what had been won for Dissent was no less actively supported in his

home, from the first closely associated with the pioneers in this movement.

From these influences came the demand for universal freedom of thought and for the complete legal equality of the sexes ; the

continual battle against all arbitrary disabilities the eager instinct to help everyone despised or oppressed,- which were the mainsprings

of his life and character, so fully reflected in this book.

He was decidedly precocious, with a retentive memory and regularly industrious habits which enabled him to master Euclid at the age

of ten. He was educated at his father's school, and owed much to his father's teaching ; but having outdistanced all the other boys,

was, at the age of twelve or thirteen, sent for special lessons in Latin and Greek to a private tutor, who used to tell his undergraduate

pupils that he was teaching a little boy who could run between their legs and who knew more Greek than they did. In the Cambridge

Senior Local Examination, at the age of seventeen, he was first in all England in Classics and second in Mathematics.

The fact that throughout life everyone noticed "how young he seemed" - "a little boyish and irresponsible" -"one who made friends quite

simply with young and inexperienced things" - is enough to prove that serious moral and intellectual training combined did not make

him either unsociable or pedantic. He was always, in fact, keenly interested in cricket, an enthusiastic chess player, an indefatigable

walker; given to eager talk on all subjects - trivial or profound; with a cheerful, equable temperament, a keen sense of fun and a great

power of enjoying the simplest pleasures. The boy of eighteen who had experienced "the keen agony" of homesickness, when sent

away for some months to the sea for his health, was neither a crusty bookworm nor absorbed in the cultivation of his own brain.

He entered Trinity College in I 876 as a Sizar, and next year obtained a Foundation Scholarship, thus gaining, as his old friend and

tutor, the Rev. Percival Frost, playfully expressed it, "the first place in the first College of the first University in the first Empire in the

first planet which has a moon." He read both Classics and Mathematics ; and it seems almost more than a coincidence that in the

latter he should have been placed eighth wrangler, in a bracket with Miss Scott of Girton, the first woman to secure a really

distinguished position in an Honours examination of any university; though not, of course, at that time, thereby entitled to any of the

privileges or rewards due to success. He could not fail to be impressed by the injustice.

Meanwhile the religious features of the stricter Puritanism, already modified in his parents generation by the influence of broad

Churchmen like F. D. Maurice, F. W. Robertson, and Charles Kingsley, were both strengthened and widened for him by active

participation in the work of unsectarian Adult Schools, supported by university men with every variety of faith. He came under the spell

of Rendel Harris (Fellow of Clare), whose "spiritual genius attracted a wide circle of undergraduate friends" ; and he also attended "a

small Positivist Club," started by Homersham Cox (a brother of the editor of the Edinburgh Review), where the members read and

discussed Comte's Catechisrn and other "bibles," not officially recognised as "inspired."

AT THE COLONIAL OFFICE

Though not chosen at once, or without careful reflection, the Civil Service naturally offered peculiar attractions to George Johnson, with

reasonable promise of usefulness and distinction. Once more his gift for doing himself full justice in examinations stood him in good

stead, and in 1881 he obtained a clerkship in the Colonial Office.

Henceforth, as one of his colleagues writes, "he became a part of the Civil Service machine, a cog on the wheel, doing his share in the

common work" ; but even the routine executive of an Empire must involve responsibilities and interests enough to occupy a

conscientious intelligence, and he, at any rate, put his whole soul into the work; even on his holidays the official Government pouch

followed him about. For a long time he was occupied in the Eastern Department, but in 1904 he succeeded Sir John Anderson as

head of the old North American and Australian (later transformed into the Dominions) Department ; having become a First Class Clerk

in 1897 and a Principal Clerk in 1900.

In 1898, as a consequence of overstrain, the sight of one eye entirely failed. For three weeks he had to lie on his back, blindfold, but it

was typical of his nature that he made no complaint. He never fully recovered the use of his eyes, and for many years was not allowed

to do any Continuous reading. He was able, however, to resume his work at the Colonial Office with the help of a Junior Clerk, who

read aloud most of the documents he had to study or examine.

Outside regular department work he was, for a time, an Assistant Private Secretary to Mr. Joseph Chamberlain, Private Secretary to

Sir Robert Meade, and, in 1907, joint Secretary to the Colonial Conference. He had also considerable "Committee" experience, being

Secretary to the Eastern Currency Committee of I 893 and a member of the Straits Settlements Currency Committee 1902-3 ; also

Secretary to the Pacific Cable Conference of 1905.

When offering him the C.M.G. in 1905, Mr. Alfred Lyttelton, then Colonial Secretary, wrote personally "I have an instinct that honours

are not a great object to you. Yet in the Civil Service they have a real meaning, and my submission of your name to the King for a

C.M.G. is not an empty form, but implies on my part a sincere admiration of your work and an appreciation of the independence with

which you look on affairs and impress your character upon them. If this distinction gives you any pleasure, you may be certain that I

also am made happy by bestowing it." Though "a strenuous Civil Servant" and always loyally carrying out the decisions and policy of

his Chiefs with energetic ability, there were from the first two marked characteristics which made him "as unlike as could possibly be

imagined to the typical, starched, precise Head of a Department, the dried creature of forms and precedents, the bloodless thing of

parchment and red-tape of the stage and the press. His juniors were permitted liberties which, though they undoubtedly made for

harmonious working in the Department, would have shocked, and perhaps did shock, more conventionally minded Principal Clerks" ;

while, on the other hand, "there were times when his high sense of public duty and of the standard that is incumbent on the public

service to maintain required him, in his judgment, to take up a line in official matters which would perhaps seem unduly severe to more

easy-going colleagues."

In the second place, he never was one to delay decisions through confusing expediency with principle, or regarding the one as of

equal value with the other. His mind was governed by principles well formulated and unshakeable. "His views on certain questions

- for instance, those of the undesirability of the public toleration of vice, the importance of maintaining a fair treatment of the native and

of preventing his exploitation, and the extreme desirability of maintaining direct financial control; his vigorous hatred of 'jobs' of all

kinds, and wholesome scepticism of the sometimes supposed omniscience of the man on the spot, were never concealed, and may

sometimes have been urged, as St. Paul bids us, not merely in season but out of season. I am not sure that some of his popularity

with his colleagues was not due to this circumstance, for popular he undoubtedly was."

In various directions it is clear that, apart from the general advantage of gaining experience and knowledge of public life, his thirty-six

years at the Colonial Office, from which he retired in 19I7, were of special value to his later, more personal activities in social reform,

by giving him a wide and intimate familiarity with all executive procedure, an accurate knowledge of law and statecraft, and, above all,

much inside information on various special social problems and on the practical difficulties - in the face of prejudice - of securing

justice for subject races. He had acquired, in one word, the international outlook.

HOME LIFE

In 1883, two years after entering the Colonial Office, he married Lucy Nutter, whose family had been long and intimately associated

with his own.

He was never a man to keep one ideal "to face the world with" and another for the home. It was in the home that his characteristic

tenderness and supremely unselfish nature were most fully revealed. His mother once wrote "When you were a tiny baby I used to

have all sorts of great hopes and thoughts about you, and I often asked our Father in Heaven to make you a very good man." Literal

answer to prayer is sometimes granted us; and it was assuredly his goodness that first impressed, and always remained with, all who

knew him. One, on hearing of his death, wrote of his friendship with those "who had no other return to make on their part than a

grateful affection for all that he liberally and unconsciously gave"; and another that his youthfulness of spirit "makes it so much easier

to realise him as living still, in a fuller sort of life even than before."

For more than thirty years he put into practice that equal comradeship between man, woman, and child which is the personal side of a

true ideal of absolute liberty for the individual. He could not be "the master" of the house or a stern parent. The friendship with his

children, which not many parents attempted in those days, was eager and quite spontaneous. He always enjoyed telling the story of a

favourite book ; he could carry you away into strange lands with the people of Notre Dame and Peveril of the Peak, though it was

English Dickens of whom he talked and told most. He took an enthusiastic interest in their games, especially cricket, to their delight

forming a cricket club for boys and girls - his own children and their young friends - and teaching them chess. From the first he led

them to take a keen interest in politics, to know about public men, to read speeches and watch elections, to understand the great

principles of Liberalism which, as he believed, had won so much for the world. His zeal both for citizenship and for social reform was

intimately shared with his wife and children.

He always attached far greater importance to faith and conduct than to outward forms and ceremonies, and it was literally a desire to

see the Sermon on the Mount put into practice that inspired him with the energy to devote so much of his leisure to supporting various

causes which he thought would help mankind. Never associating religion with a sad face, he had a rare gift for inspiring his children

with ideas while encouraging and entering into their daily amusements. On Sundays they played delightful games. For instance, they

used "bricks" to build up the walls of Jericho, round which he would lead them in a vigorous and cheerful march - until the walls fell.

They made trenches of sand outside Babylon, building a dam at one end of her gates, that the mighty Euphrates should flow out of the

proud city, wherein Belshazzar, the king, sat at the feast - and, behold, the soldiers of Cyrus were upon them, walking dryshod along

the river-bed.

He had himself continued and developed the truly broad-minded religious enquiries of his college days. For many years he regularly

attended the services of prominent Nonconformists of advanced views, and finally found himself in sympathy with Dr. W. E. Orchard of

the King's Weigh House Church, discovering there an unexpected appreciation of even elaborate ritual as taught and practised by the

Free Catholics - a remarkable development from the precise Puritanism of an earlier generation. It was, however, in strict accord with

his lifelong battle for absolute freedom that he should uphold the time-honoured right of Congregationalists not to be tied by any

traditions of orthodox denominationalism.

PUBLIC AND SOCIAL WORK

So far as possible to a Government official, he had always been actively engaged in practical work for the many bodies of religious,

educational, political, and social progress which in their different spheres were working for all the causes he had at heart. For a time

closely associated with Fabians, and Editor of the Christian Socialist, he was for many years a valued member of the National Liberal

Club ; from I887 to 1898 he was Chairman of Morley College for Working Men and Women ; he served on the Committee of the

Browning Settlement at Walworth, and was Secretary of the Moffat Institute Council in Kennington; for several years a member of the

Governing Bodies, first of Hackney College, and later of the amalgamated Hackney and New Colleges; a Director of the London

Missionary Society from 1906, and on its Committee from 1909, until his death; one of the original nine Trustees, and Chairman, of the

Stansfeld Trust; an active worker for the Women's Suffrage Societies which later amalgamated into the "National Union of Societies for

Equal Citizenship"; and for more than thirty years a "tower of strength" to all the leading spirits of the "Association for Moral and Social

Hygiene."

The Governors of Hackney and New College have put on record their sense of personal loss, and their recognition of his "business

acumen and wide experience" so cheerfully devoted to their service "throughout the delicate and difficult process of drawing up the Bill

(of July, 1924, for amalgamation), and the necessary negotiations with the Board of Education, Charity Commission, and the Trustees

of Denominational Trusts."

Mr. Frank Lenwood, Foreign Secretary of the London Missionary Society, has written a striking, human appreciation of George

Johnson, as he knew him: "My first memories are connected with the picture of an official high up in the Colonial Office who had a

keen interest in foreign missions. . . . He was glad enough to help, as everyone who knew him will understand, and I came away with

exactly the direction I needed. He criticised constructively, with knowledge and disarming gentleness. But the dominant impression I

brought away from that rather drab apartment was of a public servant handling great world-interests, who cared for God's Kingdom

before any official or personal interest, and never forgot that he was there to be consul and trustee for the common man. . . . Then as

the years brought his retirement from office, he became a member and later Vice-Chairman of our India Committee. . . . His

experience was invaluable in consultation. Never was a man less ridden by officialism. . . . He was for allowing to everyone as much

liberty as possible. If theology came into question, and some missionary seemed too broad for certain cautious folk, George Johnson

was always inclined to freedom. When a progressive policy was afoot, he would be skirmishing away on the flank of the advance,

supplying all the reinforcement he could by terse, pointed, rather professorial speech. Now and then he would expose the unreality of

some argument by a witty phrase. . . . He found it hard to understand that there were people who did not want to be progressive. For

him Christianity was a place of broad rivers and streams, a far-stretching land, without fences or straight-cut arterial roads.

"I can see him now in Committee, a very individual figure, with the distinction that still lingers round the universities and circles where

men use their brains in planning and criticism. He was not particular about his clothes or appearance, and extreme short sight added

to the general aspect of rather amusing unworldliness. . . . What I remember best is his perpetual desire to help those responsible for

the business of the meeting. He moved motions when others were uninspired and reluctant to speak, he drafted phrases which might

secure the end the Committee sought, and altered them with eager friendliness if they failed to meet the need. He was full of a loyal

humility and affection; one of those who, whether they carry a hod or carve a corner-stone, are bound to build. What he built will stand

the fiery test of the years."

Through the acute stage of "excitements and agitation" in the Suffrage Movement he was a devoted supporter, "peculiar in combining

enthusiasm with judgment," walking in the processions and helping a woman candidate for Parliament on more than one occasion.

From an early period of close personal friendship with Mrs. Josephine Butler, James Stuart, (1) and

Henry J. Wilson, (2) he gave of his best,

for long years of untiring perseverance, to the principles for which they stood, once summarised by Mrs. Butler herself as "the unity of

the moral law and the equality of all human souls before God."

When the Contagious Diseases Acts were repealed in 1886, Josephine Butler and her colleagues transferred their support to

abolitionist work in the Empire and on the Continent of Europe, forming the "British Committee of the International Abolitionist

Federation," afterwards known as the "Association for Moral and Social Hygiene." In 1887-8 their main task was to secure the

adoption in the Crown Colonies of the same policy which had just been accepted for Britain. In the words of Dr. Helen Wilson, the

President of the Association : "It was at this stage that George Johnson came into the movement. . . His position at the Colonial Office

enabled him to render substantial service to the cause . . . he was frequently called into consultation by the leaders, and he drew up

several of the manifestoes and memoranda issued at this period. . . When he resigned from the Colonial Office in 1917, he became a

full member of the British Committee, and held several offices, including that of Vice-Chairman.

"It would be difficult to overestimate the value of the service which he gave so ungrudgingly. There was nothing spectacular about it ; it

was honest, faithful, dogged work. He was always to be relied on to be in his place at the meetings, to give careful attention to every

subject and to bring to bear on it his experience and balanced judgment. . . . He believed in the work of the Association with his whole

heart and soul, and gave heart and soul to it. . . He was a member of the unofficial Commission of Enquiry, organised at the close of

the war, to review English legislation and administration bearing on sexual morality, and wrote its Report - The State and Sexual

Morality, a useful compendium of the law as it stands and the necessary amendments to make it as it should be.

"In practical support of the Committee's chief work during the last two or three years, he drafted a Bill which was introduced by Lady

Astor, M.P., in 1925. It proposed to abolish the special clauses relating to 'common prostitutes,' and to substitute a section making it

an offence for any person to annoy another in the street, but stipulating that no prosecution can take place except on the complaint of

the person annoyed. This Bill was the expression of his conviction that it is only by equal laws, embodying individual liberty and

individual responsibility, that a higher social order will be attained."

It may be added that he was chosen as one of the delegates of the Association to give evidence before the Joint Select Committee of

Lords and Commons on the Criminal Law Amendment Bill in 1920. He also attended two of the Conferences of the International

Abolitionist Federation, at Geneva in 1920 and at Graz in 1924. On hearing of his death in February, 1926, Monsieur A. de Meuron,

Chairman of the International Abolitionist Bureau, wrote : "Il a défendu, et parfois avec une belle intransigeance, les principes dont se

sont inspirées Joséphine Butler et toute la Fédération. Ainsi les vétérans disparaissent; puissent des jeunes relever le drapeau tombé

des mains des aînés et continuer la lutte dans le même esprit qu'eux!"

Partly because he saw these questions as one aspect, though the most morally fundamental, of the general principles of liberty,

justice, and equality, and still more from his training and well-balanced mind, he was never tempted to the unfortunate exaggerations

or violence so often inspired by generous zeal. Few have given their lives to these questions with such sanity of vision, real charity -

applied equally to all persons - and broad-minded, practical common sense.

It was these characteristics, combined with sound knowledge, patient industry, and administrative experience, that gave special value

to his work, that stamped the man, that led to, and have governed, the comprehensive and wisely proportioned construction of his

book.

He died, after a few days' illness, on February 13, 1926, at the age of sixty-eight. No narrative of facts, however faithfully told, can

completely and adequately show him as he really was. His very gentleness of character and extreme tenderness and patience could

be revealed only to those to whom he was most near and dear. We cannot think of his life as in any way ended, or separated from

those with whom he worked, but rather as continuing his usefulness, only with more light and a clearer understanding of the fulfilment

of his Father's will.

1 Professor Stuart, M.P. (a personal friend of his), made Privy Councillor 1909.

2 H. J. Wilson, of Sheffield, M.P., prominent worker for the Abolitionist cause.

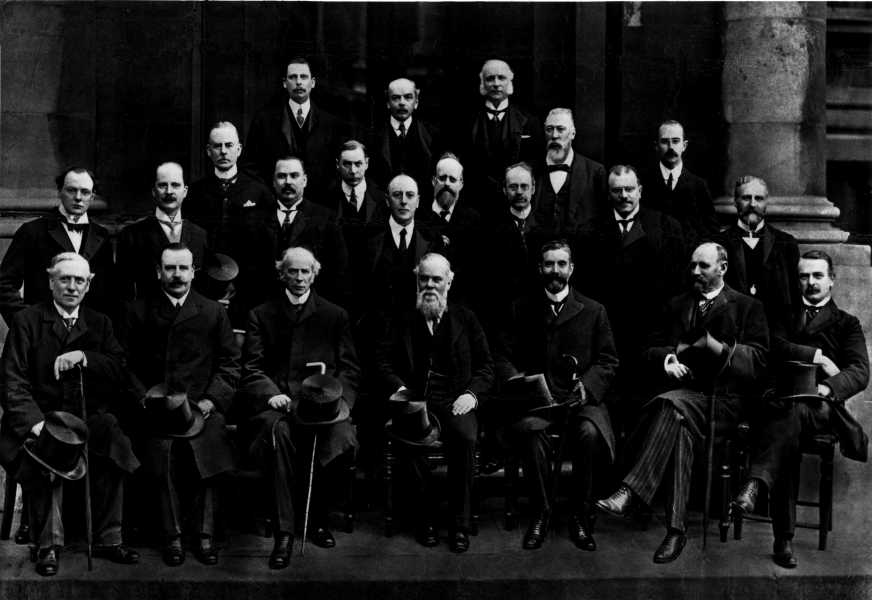

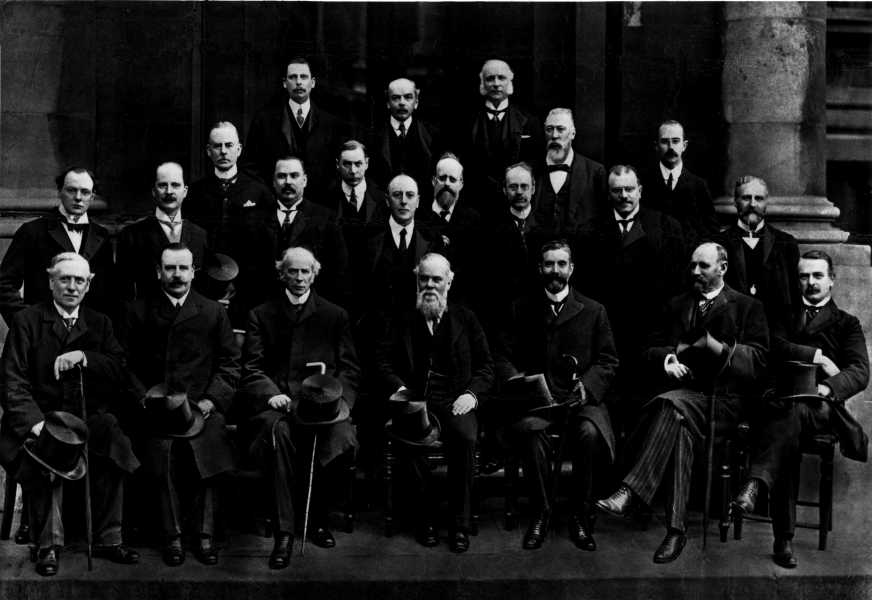

George William Johnson in the company of politicians like Lord Elgin, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Winston Churchill, Lloyd George, H. Asquith,

General Botha,

at the 1907 Conference of Colonial Prime Ministers, of which GWJ was co-secretary.

Sir Cosmo Parkinson, in his book "The Colonial Office from Within, 1909-1945", London: Faber and Faber, 1947, on page 126 says:

And there is a tradition - but I cannot vouch for its truth - that one day a certain senior official was busy on some urgent matter, when a

rather tedious colleague came into his room uninvited, and left the door ajar. "You might shut the door," said the occupant of the room

in a quiet voice. The visitor did so, and was about to launch out into his usual flow of speech when he was cut short by the further

words, "On the other side please."

These remarks were attributed to George William Johnson by Sir Charles Jeffries in his book "The Colonial Office", London: Geo Allen

& Unwin; NY: Oxford University Press, 1956, pp16-17.

There are half a dozen references to him in John Edward Kendle, "The Colonial and Imperial Conferences, 1887-1911", Longmans,

1967.

Sir Arthur Francis Grimble (1888-1956), in his book titled "A Pattern of Islands" (3) republished for

the Reprint Society by John Murray, 1954, makes extensive reference to George William Johnson. On pp14-19, there is a description of GWJ

and of his interviewing Grimble for his first job in the Pacific. References to this interview are

to be found on pp 35 (para 2), 36 (para 3), 40 (paras 2 & 3) and on the bottom of p 56. There is also a reference to

"Kind Mr Johnson ..." on the last page (p312):

I did, indeed, secure an interview at the Colonial Office, but my nearest approach to stubbornness with the quiet old gentleman who

received me there was to confess, with a gulp in my throat, that the imaginary picture of myself in the act of meting out imperial

kindness-but-firmness to anybody, anywhere in the world, made me sweat with shame.

The quiet old gentleman was Mr. Johnson, a Chief Clerk in the department which handled the affairs of Fiji and the Western Pacific

High Commission. That discreet title of his (abandoned today in favour of Principal and Secretary) gave no hint of the enormous

penetrating power of his official word. In the Western and Central Pacific alone, his modest whisper from behind the throne of authority

had power to affect the destinies of scores of races in hundreds of islands scattered over millions of square miles of ocean. I was led

to him on a bleak afternoon of February, 1914, high up in the gloomy Downing Street warren that housed the whole Colonial Office

staff of those days. The air of his cavernous room enfolded me with the chill of a mortuary as I entered. He was a spare little man with

a tenuous sandy beard and heavily tufted eyebrows of the same colour. He stood before the fire, slightly bent in the middle like a

monkey-nut, combing his beard with one fragile hand and elevating the tails of his cutaway coat with the other, as lie listened to my

story. I can see him still, considering me over his glasses with the owlish yet not unkindly stare of an undertaker considering a corpse.

(Senior officials in the Colonial Office don't wear beards today, but they still cultivate that way of looking at you.) When I was done, he

went on staring a bit; then he heaved a quiet sigh, ambled over to a bookcase, pottered there breathing hard for a long while (I think

now he must have been laughing), and eventually hauled out a big atlas, which he carried to his desk.

"Let us see, now," he murmured, settling into his chair, "let us see . . yes . . . let us go on a voyage of discovery together. Where . . .

precisely . . . are the Gilbert and Ellice Islands? If you will believe me, I have often been curious to know."

He started whipping over the pages of the atlas; I could do nothing but goggle at him while he pursued his humiliating research.

"Ah!" he chirruped at last, "here we have them: five hundred miles of islands lost in the wide Pacific. Remote . . . I forbear, in

tenderness for your feelings, from saying anything so Kiplingesque as far-flung. Do we agree to say remote and not far-flung?" He

cocked his wicked httle eye at me.

I made sounds in my throat, and he went on at once, "Remote ... yes . . . and romantic . . . romantic! Eastwards as far as ship can sail .

. . up against the gateways of the dawn . . . coconut-palms, but of course not pines, ha-ha! . . . the lagoon islands, the Line Islands,

Stevenson's islands! Do we accept palms, not pines? Do we stake our lives on Stevenson, not Kipling? Do we insist upon the

dominion of romance, not the romance of dominion? I should appreciate your answer."

I joyfully accepted Stevenson and ruled Kipling out (except, of course, for Puck of Pook's Hill and Kim, and the Long Trail, and others

too numerous to mention); but my callowness squirmed shamefully at romance. He became suddenly acid at that: "Come, come! You

owe perhaps more to your romanticism than you imagine - your appointment as a cadet, for example." The truth was, according to him,

that I had been the only candidate to ask for the job in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. But for that. . . if, in fact, I had been up against the

least competition. . . well... who could say? As I, for one, could not, he leaned back in his chair and fired a final question at me: "I may

take it, may I not, that, despite certain doubts which you entertain about the imperialism of Mr. Kipling and . . . hm . . . a great many of

your betters, you still nurse your laudable wish to go to the Central Pacific?"

I replied yes, sir, certainly, sir, but how was I going to tackle this thing about leadership, sir.

"He peered at me incredulously, rose at once, and lifted his coat-tails again at the fire, as if I had chilled whatever it was. "I had

imagined," he confided in a thin voice to the ceiling, "that I had already - and with considerable finesse - managed to put all that in its

right perspective for this queer young man."

"However," he continued, after a long and, to me, frightful silence, "let us dot our i's and cross our t's. The deplorable thing about your

romanticism is that you display it as a halo around your own head. You seem to think that, when you arrive in the Gilbert and Ellice

Islands, the entire population will forthwith stop work to stand with bated breath awaiting your apotheosis as a leader among them."

The blend of venomous truth and ghastly unfairness in this bit deep into my young soul; I opened my mouth to protest, but he overrode

me: "You permit me to proceed? Thank you. Now, believe me, your egocentric surmise is grotesquely incorrect. You will encounter out

there a number of busy men interested primarily in only one thing about you, namely, your ability to learn and obey orders. These will

severely deplore any premature motion of your own to order them - or, in fact, anybody else-about. They will expect you to do as you

are told - neither more nor less - and to do it intelligently. In the process of learning how to obey orders with intelligence and good

cheer, you may, we hope, succeed in picking up some first, crude notions about the true nature of leadership. I say 'we hope' because

that is the gamble we, in the Colonial Office, have taken on you. Kindly do your best to justify it."

Though his tone had been as cutting as his words, the flicker of a smile had escaped once or twice, as if by permission, through his

beard. I got the notion that the smiles meant, "You incredible young ass! Can't you see this is the way round to put it to your uncles?"

But when I gave him back a timid grin, he asked me sharply why. I answered sheepishly that he had eased my mind, because truly,

truly I didn't want to go ordering anybody round any more than he wanted me to.

At that, his manner changed again to one of sprightly good humour. He began to tell me a whole lot of things about a cadet's training in

the field (or, at least, the training he thought I was destined to get in the Central Pacific) that nobody else had ever hinted at. As I

understood the burden of it, it was that I would serve my first year or so of probation on Ocean Island, the administrative capital of the

Protectorate, where I would be passed from department to department of the public service to learn in successive order, from a series

of rugged but benevolent Heads (all of whom quite possibly harboured a hidden passion for the writings of R.L.S.), the basic functions

of the Secretariat, the Treasury, the Magistrate's Court, the Customs, the Works Department, the Police, the Post Office, and the

Prisons organization. I don't know what magic he used - he certainly never spoke above a chirp; but he managed to make that arid list

of departmental flames roll from his lips like the shouting of golden trumpets upon my ear. I had a vision as he spoke: the halo he had

mentioned burst into sudden glory around my head.

It was dawn. I was hurrying, loaded with papers of the utmost import, through the corridors of a vast white office building set on an

eminence above a sapphire ocean. I had been toiling all night with the Chief Secretary, the Treasurer, the Magistrate, the Collector of

Customs, the Commissioner of Works, the Chief of Police, the Postmaster General, and the Keeper of the Prisons. The job was done!

I had pulled them all through. Just in time! There in the bay below lay a ship with steam up, waiting for final orders. I opened a door. A

man with a face like a sword - my beloved Chief, the Resident Commissioner himself - sat tense and stern-eyed at his desk. His

features softened swiftly as he saw me: "Ah . . . you, Grimble . . . at last!" He eagerly scanned my papers: "Good man . . . good man!

It's all there. I knew I could trust you. Where shall I sign?. . . God, how tired I am!". "Sign here, sir. . . I'll see to everything else. . . leave

it all to me." My voice was very quiet, quiet but firm ...

". . . and remember this," broke in the voice of Mr Johnson, "a cadet is a nonentity." The vision fled. The reedy voice persisted:

"A cadet washes bottles for those who are themselves merely junior bottle-washers. Or so he should assess his own importance,

pending his confirmation as a permanent officer."

He must have seen something die in my face, for he added at once, "Not that this should unduly discourage you. All Civil Servants, of

whatever seniority, are bottle-washers of one degree or another. They have to learn humility. Omar Khayyam doubtless had some

over-ambitious official of his own epoch chiefly in mind when he wrote 'and think that, while thou art, thou art but what thou shalt be,

NOTHING: thou shalt not be less.' Sane advice, especially for cadets! Nevertheless, you would do well to behave, in the presence of

your seniors, with considerably less contempt for high office than Omar seems to have felt. Your approach to your Resident

Commissioner, for example, should preferably suggest the attitude of one who humbly aspires to 'pluck down, proud clod, the neck of

God'."

Who was I, to question the rightness of this advice? I certainly felt no disposition to do so then (I don't remember having felt any since)

and, as he showed no further wish to pursue the topic, I passed to another that had been on my mind. A marriage had been arranged.

My pay as a cadet would be £300 a year, plus free furnished quarters. Did he think a young married couple could live passably well on

that at Ocean Island? I pulled out a written list of questions about the local cost of living. At the word "marriage" he started forward with

a charming smile, light-stepping as a faun, whisked the paper from my hand, laid it on the mantelpiece, and turned back to face me:

"Ah . . . romance . . . romance again," he breathed, "a young couple . . . hull-down on the trail of rapture . . . the islands of desire . . .

but there is method, too . . . let us look before we leap . . . the cost of living! A businesslike approach. Very proper. Well . . . now . . .

hmm . . . yes . . . my personal conjecture is that you should find the emoluments adequate for your needs, provided always, of course,

that you neither jointly nor severally acquire the habit of consuming vast daily quantities of champagne and caviare. Remember, for the

rest . . . in your wilderness . . . how the ravens fed Elijah . . . or was it Elisha?"

And that was that about the cost of living. I was too timid to recover my list from the mantelpiece.

3 In England and Canada, the title was "A Pattern of Islands". In the USA, the edn. published in 1952

was titled "We Chose the Islands"

He is listed in "Who's Who -1906", -1908, -1909, -1910, -1911, -1912, -1913, -1914, -1915, -1916, -1917, -1918, -1919, -1920, -1921,

-1922, -1924, -1925, -1926, and in "Who Was Who, 1916-1928". The entries generally read:

"Johnson, George William, C.M.G. 1905; M.A.; Principal clerk in Colonial Office, 1900-17; eldest son of W.H.F. Johnson, M.A., J.P., of

Llandaff House, Cambridge; b. 1857; m. 1883, Lucy, 6th d. of late James Nutter of Cambridge; two sons, two daughters. Educ: his

father's school; Perse Grammar School; Trinity College, Cambridge (Foundation Scholar 1877), 8th wrangler and 3rd class Classical

Tripos, 1880. Appointed 2nd class Clerk Colonial Office, 1881; Secretary to Eastern Currency Committee, 1893; Assistant Private

Secretary to Mr Chamberlain, 1896; Private Secretary to late Hon. Sir R. Meade, 1896; member of the Straits Settlements Currency

Committee, 1902; Secretary to Pacific Cable Conference, 1905. Publications: Dickens' Dictionary of Cambridge; editor of the Christian

Solialist, 1891; occasional reviews in the Spectator etc.; (in conjunction with his wife) Memoir of Josephine E. Butler, 1909; The State

and Sexual Morality, 1920. Recreations (depending on date): golf, cycling, music, reading, chess. Address: varies. Club: National

Liberal."

His address was variously given as: 223 Brixton Hill (1906), 2 Mount Ephraim Rd, Streatham (1908-19), 22 Westbourne Park Villas

(1920-1926).

|