Sunday 23 November 1997

Ready to face the music

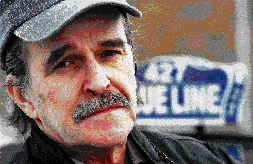

Wayne Hiebert, The Ottawa Citizen / Behind the scenes in the '60s, Bill Hawkins was tutor and mentor to Market musicians including Bruce Cockburn, David Wiffen and Sneezy Waters. After some rough times in the past 25 years, Hawkins is now putting the finishing touches on a new recording. Wayne Hiebert, The Ottawa Citizen / Behind the scenes in the '60s, Bill Hawkins was tutor and mentor to Market musicians including Bruce Cockburn, David Wiffen and Sneezy Waters. After some rough times in the past 25 years, Hawkins is now putting the finishing touches on a new recording. |

There are those who say one of the best places in this world to hide out is behind the wheel of a taxi cab. Sure, you pick up dozens of people every day but, mostly, all they see is the back of your head and all they want to talk about is the weather or last night's hockey game.

There are those who say Bill Hawkins has been hiding out behind the wheel of a Blue Line cab for almost a quarter-century. Hiding from temptation, maybe, or hiding out from old friends, good friends and bad friends.

Bill Hawkins was once a pretty big fish in this small-ish pond. As a poet, a songwriter and a musician in the '60s, he was at the epicentre of Ottawa's thriving blues-rock-folk scene, a scene that pre-dated the snootier and over-hyped Yorkville. He was tutor, mentor and self-described "megalomaniac manipulator" behind a series of lamented bands that featured younger artists like Bruce Cockburn, David Wiffen, Colleen Peterson, Sneezy Waters and a dozen others.

There are those who were around at the time who insist to this day that, with a break or two and maybe a little more discipline, Hawkins could have been a bigger fish in a bigger pond. But, in case you weren't there, the '60s weren't a time of moderation and Hawkins wasn't the sort of guy to deny himself a pleasure or two. Ask people who were around at the time and they'll tell you -- in terms midway between admiration and a shudder -- that Hawkins was a guy of considerable appetites, even taking the open-mindedness of the times into consideration.

As sometimes happens, the pleasures eventually became liabilities, and then just plain dangerous, and life can drift away from you.

Unlike some less fortunate victims of the times, Hawkins was strong enough and had enough friends to come out the other side. But the stress was powerful and, in the early time of recovery there's always the fear of relapse. For some, a nice, fairly comfortable job as a cab-driver is a lot more attractive and healthy sounding occupation than trying to push your luck in the music business snake pit.

"The cab was a perfect way to hide out," Hawkins says now. "It was an outlaw existence, nobody knew where you were. It kept the temptations away."

But, anyway, the past is done with, for better or worse. At 57, he's looking to the future and he figures he's finally ready to face the music business again.

More important, he's confident the music business is finally ready for him.

You who read me Tennyson reluctantly

And James Whitcomb Riley digging every line

-- For Jenny Louisa Lockyear

Bill Hawkins

He laughs and calls himself "just a lad from the Valley," but that's not strictly true.

William Hawkins is Ottawa born and bred, son of the late Graham Hawkins, a car salesman, and mother Fern (now Fern Horsey). He grew up mostly around Ottawa, near Hopewell Avenue School. To hear him tell it now, he wasn't much of a student, not much interest in it really, but he was raised to be a hungry reader by his maternal grandmother Jenny Louisa Lockyear, who was the subject of one of his first poems.

"She was a wonderful old woman. She read everything, she had this broad, exciting imagination and she made me see the world of books and writing."

Jenny Louisa Lockyear gave him a love of writing, but Hawkins says the Canadian Press news agency, which he joined at the age of 17, taught him the basics of writing. The agency's meat-and-potatoes, just-the-facts style taught him to organize thoughts on paper and tell a story simply and effectively.

What the agency couldn't provide was an outlet for Hawkins' growing love of poetry. Coming into the '60s, Hawkins was hanging out more and more with the bohemian types who gathered in the Market and, in 1961, he and author Roy MacSkimming combined for their first published work, a chapbook with the goofy title Shoot Low Sheriff, They're Riding Shetland Ponies!

The book was a minor phenomenon in Bytown literary circles, such as there might have been at the time. More important, it caught the attention of Harvey Glatt, then and now something of a godfather for the Ottawa music scene. Glatt, now chairman of radio station CHEZ-FM, was then the owner of the Treble Clef chain of music stores and he encouraged Hawkins to keep writing, offering him a job selling records in the downtown Treble Clef store.

"It was one of those things that Harvey did that he did for so many musicians and artists in this town, things he never talks about but things that are crucial moments in peoples' lives," Hawkins says.

Around this time, the memories start to get fuzzy. It's probably the '60s/Woodstock syndrome: If you were a full-fledged participant you really can't pin specific dates to specific events. All anyone can agree on is that, around the mid-'60s, the nucleus of what was to become The Children, one of the most talent-heavy acts to ever come out of Ottawa, were hanging out together.

For example, Hawkins remembers running into a teenaged Bruce Cockburn at a "jazz-mass" Cockburn had composed for a west-end church. Other original Children, people like Sneezy Waters, Neville Wells and Sandy Crawley were hanging out at Glatt's Le Hibou coffee house on Sussex Drive. Later, folk-blues singer David Wiffen joined the group. The characters and personalities just seemed to float together until they gained critical mass. Hawkins urged Cockburn to write lyrics, Cockburn urged Hawkins to write music.

"It was probably the nature of the time," says Hawkins.

"You met people, you jammed, you showed people your stuff. It was, I hate the way this sounds now, a sharing period and we came together as mostly equal partners."

Well, by Hawkins' memory of events, some members were more equal than others. In a way, there were just too many talented people for The Children to remain together as a band. In another way, though, Hawkins says he feels responsible, as the oldest member of the band, for not being able to keep the group together.

"It's true that there were a lot of internal pressures. But I was slipping badly, drinking way too much, partying too much. You've got to remember I was five years older than the rest of the band. When you're 50 or something, five years is nothing, but when you're in your 20s, it's a huge difference and I was the de facto leader and I wasn't leading."

The highlight of the band's career was an opening slot for the Lovin' Spoonful at Maple Leaf Gardens ("probably in 1966"), but by early 1967 The Children were no more and things started getting strange.

Hawkins still had some personal control and he formed the band Occasional Flash, which included the late Colleen Peterson and Cockburn and which performed before the Queen and 50,000 others at Lansdowne Park for Centennial year. There was the jazz blues supergroup Heavenly Blue with Amos Garrett on guitar, Darius Brubeck (son of Dave) on piano, Sandy Crawley on bass and Carl Corbeau on drums. There was another top-rate band called Heaven's Radio É

For this period in his life, Hawkins' memory starts to get shaky. He and his crowd were the centre of attraction in Ottawa and not only did they have party friends in the community, visiting performers looked to Hawkins and the bunch to show them the sights.

"Every day was party time. I remember going up to Wakefield (then a major centre of pharmaceutical distribution) with Wiffen, Jerry Jeff Walker and (insane Cajun fiddler) Doug Kershaw. We got into more trouble in six hours than most people could get into in six years."

By 1969, even Hawkins realized things were out of control and he came up with the idea of travelling to Mexico to get his life together. It seemed like a good idea at the time. In hindsight, it was stupid.

"(David) Wiffen tells me I left in October (1969) but I'm sure it was earlier. Anyway, all I know is I got in the car with (his ex-wife) and two kids and didn't stop until we got to Mexico.

"I thought I'd go down there to get my strength back, that's how screwed up I was. I mean, beer was, like eight cents a litre, tequila was eights cents a glass and you could walk into the pharmacy and say 'Could I have a quarter-grain of heroin, please?' and they'd give it to you. A guy like me was not going to get healthy there."

Of course, it took him about 10 months to come to that realization, and by the time he got to Toronto in the summer of '70 he was worse off than when he left. He tried gigging and got a little work that way, but mostly he remembers the early '70s as the years he spent dealing dope and using it.

The memories are also unclear as to how he ended up at the Donwood rehab centre in 1973. He knows the entry sheet listed "acute malnutrition (he weighed 118 pounds), alcoholism, heroin and a bunch of pills. I can't remember which ones."

Twenty-eight days later he was certified clean and sober and was faced with a choice. So, he got behind the wheel of a Blue Line taxi.

I keep my divorce papers

with my underwear, top drawer, in fact

-- Sheila Frances Louise

William Hawkins

Which brings us to the Elgin Street Diner on a Sunday morning in 1997.

It's not that nothing's happened to Hawkins for 24 years, it's just that, fortunately, it's been pretty much a normal existence. There was a divorce from Sheila Frances Louise, although Hawkins says they remain good friends and the three kids grew up and left home, one a tree-planter in B.C., one a Harvard-trained Wall Street economist and one, 26-year-old Cassandra, fronts her own rock band down in Toronto. There are four grandkids ("the loves of my life, it's a whole lot less responsibility than raising your own"). There's the cab.

What there wasn't was music.

"I don't know if it was a conscious thing or not but I just stopped listening to anything, really. Bruce's 23 albums? I haven't heard one of 'em."

That started to turn around a couple of years ago when he stopped smoking cigarettes. He started fooling around on guitar again and found himself invited to a workshop at the 1996 Folk Festival with the late Colleen Peterson. Surprising himself as much as anyone, he found himself enjoying performing a couple of songs on stage.

"It was the first time in my life I'd been on stage when I was straight. I was terrified, but what a rush."

He picked up the pace a little bit and, on a vacation to visit his son in B.C., he put together the idea of a comeback.

"He's built this beautiful home up in the mountains (near Lillooet) and he offered to build me a sort-of grampy-cabin on the property. It's spectacular up there in the mountains and it's completely different from Vancouver, it's dry and crisp. When you get to be my age you don't need damp weather.

"So I had this offer of a cabin but he's sure not going to give me spending money so I started thinking about an album of my songs and maybe a complete book of my poetry."

Oddly, in this age when 12-year-olds in garage bands have CDs, neither Hawkins songs nor The Children as a band ever officially recorded their own material, so Hawkins and producer Victor Nesrallah had lots of fresh material to work with. Nesrallah, a respected singer-songwriter and musician, brought his recording equipment to Hawkins' living room, looking for simplicity, and together they put down 15 tracks.

What surprises many listeners hearing the 95-per-cent-finished tape for the first time is how current most of the material is, despite having been written 30 and more years ago.

"I think there are a lot of factors, but I like some of the songs and Bill's performance a lot more than I did when I heard them the first time (30 years ago)," Harvey Glatt says today.

"Maybe he just didn't have the voice to carry the material then, I don't know, but it's there now. The music is very current, too, I hear chord changes that were out of place then but they're almost perfect now."

"I stole a lot of shit from Schubert," Hawkins says, grinning.

"Really, though, I try to give 'em a simple story, give 'em a hook and get out, don't try too hard. That's why I like guys like Steve Earle, just simple stories that mean a lot."

Right now, Nesrallah's putting some finishing touches on the recording while Hawkins girds himself to take on the music business again. This time, he's going to try to do things as much on his own terms as he can.

"For one thing, I'm not going to play any more bars. I want to concentrate on the universities and the folk circuit and the festivals. I just want to get this together and make a few bucks. I'll survive, I'll be poor and humble."

In conversation, Hawkins recalls a typical evening in his heyday, getting high in a hotel room with Joni Mitchell, Jimi Hendrix and Richie Havens. He played them a song of his and Havens was knocked out but also a little worried.

"I was trying to get into Joni's pants actually. Richie looked at me and said 'I don't know if the world's ready for you, man.' "

Maybe that's changed.