"As regards paint, the bulwarks and houses were painted white with bright panels. The lower masts and bowsprit were painted white, the upper masts and yards black, with all doublings, and mastheads, jibboom end, martingale, spanker gaff and boom, and spencer gaff white."

Lubbock adds on the same page that her boats were white with black topsides until Woodget painted them all white. Her specifications note that her belaying pins were steel and that she was sheathed with Muntz metal, an alloy of zinc and copper that stays a dull brass yellow colour, not copper that turns green with brown streaks. The Cutty Sark was built with the best materials and craftsmanship in every way, and Muntz metal was the best - it lasts far longer and stays sounder in salt water than the less expensive copper. Her backstays were parcelled wire - black. Sheets above the courses, and hoists above the lower topsails, were chain - black. Deadeye reeving and ratlines were hemp, unpainted; the former had to be retightened at intervals and the latter frequently replaced as they were worn.

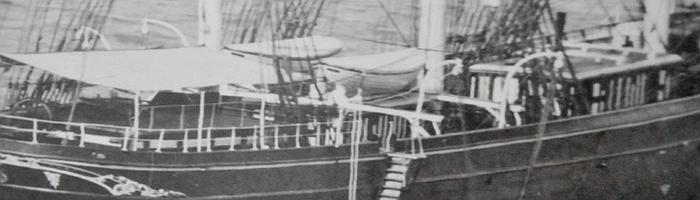

Captain Woodget's photos, notably the one in Sydney Harbour, a detail of which is below, show the way in which the fore and mid house panels and a horizontal stripe of the Liverpool cabin were painted white, that the heads were all white, that the entrance to the officers' cabins was all varnished, and that the wood masts, wood bowsprit, deadeyes, blocks and shroud fairleads were black. Although there was no doubling between the topgallant and royal sails, the masts were painted white there as if there was one. The deadeyes, blocks and fairleads may not have been painted; lignum vitae turns very dark after exposure to sun. (It must have been some time after this photo that Woodget painted the boats all white.)

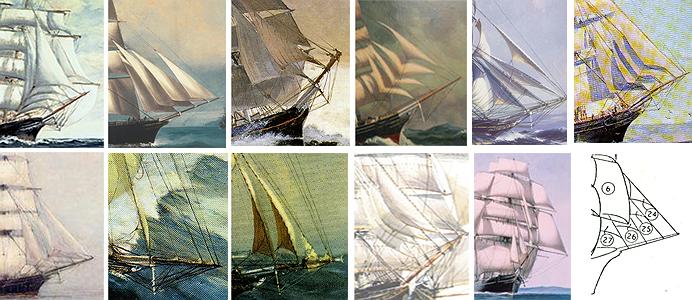

But, that isn't the way she was restored in the 1950's. Based supposedly on the secondary evidence of a single painting once owned by Jock Willis, detail below, the house panels and wood masts were varnished rather than being painted white and black respectively. (I suspect that Trust members, who undoubtedly viewed teak as the luxury furniture wood it is today rather than a wood suitable for dock pilings and the like as it was when the Cutty Sark was built, couldn't stomach the notion that anyone would just paint it.)

Why are paintings secondary evidence, and more unreliable than much secondary evidence from the time? Most paintings of ships, then and now, are generic and mostly painted in a studio by artists who all too often have never sailed a ship similar to the one they paint. Far more painterly attention is normally given to spectacular sea and sky than to the details of a ship.

The jibs in paintings labelled as being the Cutty Sark show this all too clearly. Most ships in the late 1800's had four foresails: three jibs and a fore topmast staysail. But, as her specification and photographs attest, the Cutty Sark had only two jibs. You'd never know that from the vast majority of paintings, as the following sample shows:

Models, even contemporary ones, can be equally unreliable. And, the less said about a 2015 model offered worldwide by National Geographic with three jibs and wildly oversized sails clewed to yardarms instead of to quarters, the better.

There's no substitute for Lubbock's careful combing and balancing of primary documents and the photos of Captain Woodget if you want to make an accurate model. Masting & Rigging, Harold Underhill, contains a myriad of details on how ship rigging works, also essential for accuracy.

John Sankey 2015

The Ship Cutty Sark

other notes on family history