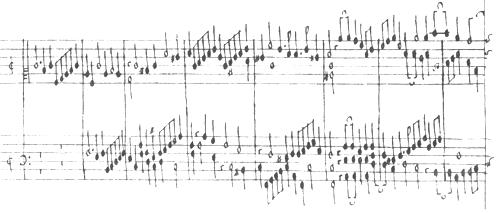

part of the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book

William Byrd (1543-1623) was one of England's most gifted and respected composers of the late Renaissance. Justly called "a father of music" even during his lifetime, he had that rare ability to see the future without being rejected by his own time. His vocal music in particular stands supreme amongst all of the time, being, in his own words, "framed to the life of the words", instead of being constructed solely on musical logic as in the past. He probably studied with Thomas Tallis, was appointed organist of Lincoln Cathedral in 1563 (aged 19!), and to the prestigious post of "Gentleman of Her Maiesties Chappell", co-organist with Tallis, in 1569. His music for the "virginalls" (the word then included what we today separate as harpsichord, spinet and virginal) is only a tiny portion of his work, but he brought the style to maturity virtually singlehandedly.

All my harpsichord recordings are Copyright © John Sankey, 2000, under the Berne convention in order to protect the right of all to continue to use them freely. Anyone may copy, link to, or distribute any of them as much as they wish as long as as long as this notice of copyright and permission to further copy is distributed with all copies. You are free to modify them as you wish for your personal use, but I require that solely my original unaltered files be posted or distributed to others. No one may restrict their further use as above in any way, by collection copyright or any other means. The courtesy of a site reference or credit is always appreciated.

Download them all as a zipped file (460 kB).

The first European music notation system was neumes, which were totally musical signs - they indicated the sounds and techniques to be used to perform the music. About the 9th century, theorists got the upper hand in music, and everything had to be fitted into diatonic modes to be officially acceptable. Of course, good musicians have always insisted on singing in tune and have always cared more about their sound than about theory, so musica ficta came to mean the rules that musicians used to translate from modes back to good music, and that is the way I always interpret them.

As late as Byrd, English music was still in transition from the melodically-based (horizontal) modes to those of harmony (counterpoint, or vertical structure), and it is sometimes unclear from musical context which was in a composer's mind. Much ficta was written out by then, but some was still left unsaid; many texts still used accidentals only as the mark of the unusual. Accidentals mostly applied solely to the note on which they were written, but often were intended to affect some prior notes as well, and they normally modified the expected pitch of the note, not the white-note pitch as today. A marking of B-dur or B-molle was often meant to last until cancelled, and the range of influence of flats seems larger than that of sharps. The medieval sharpening of leading notes in conjunct motion and the flattening of summit notes may no longer be assumed - it was becoming more common to sharpen in upward motion and flatten in downward. Musica ficta was a very variable practise, in fact it seems at times as though it was used like idiom in spoken language - to identify the foreigner in a society.

All music was hand copied and recopied then, music printing being in the future, so errors accumulated rapidly. Whole sections of a piece were sometimes lost and the remainder patched together, or "old-fashioned" sections omitted. New sections were often added to pieces at a later time by the composers themselves, especially as a mark of esteem for an honoured pupil. Misattributions are common, especially in the case of Byrd, who had a son Thomas who also composed - "Mr.Birde" is all we have in some cases. However, for Wm.Byrd we have two exceptionally trustworthy texts. My Ladye Nevells Booke was completed in 1591 by one of Byrd's colleagues at the Royal chapel, possibly corrected by Byrd personally, then presented to Queen Elizabeth I, and Parthenia was engraved by the finest engraver in England, also with the care appropriate for a royal gift, mostly from composers' manuscripts, in 1612. My other major source is the folio of Catholic composers' works copied from divers sources, probably by a Francis Tregian between 1609 and 1619, known today as the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book. I obtained useful guidance from E.H.Fellowes, "William Byrd" (1923) and from volumes 27 and 28 of Musica Britannica, edited by Alan Brown (1969). I am greatly indebted to Mark Newbold for arranging access for me to Musica Britannica to complete these recordings.

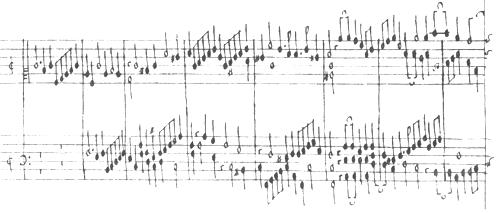

A large portion of ornamentation is written out in full in these texts, as it had not yet become as stylised as later on. Many texts contain extensive relics of the neumes, in the form of single or double crosses at the ends of, or through, the note stems. (Unfortunately, sharp signs were often also written at the stem ends, so were easily confused with stem crosses even by careful copyists.) The interpretation of these stem crosses was as variable as the practise of ficta. Their occurrence varies greatly between various copies, and in some seems almost random at times. Perhaps, even, they were used partly for visual effect, to make a manuscript seem more impressive. Many works can be played in a plain metered style, as used for dancing, in an accented multirhythmic style, or in a very florid attention-grabbing style as might be appropriate in a large hall of the time, filled with scurrying servants serving food. I use rhythmic style for some of the short pieces, but the florid style rarely - I prefer dance meter for danceable music.

part of the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book

So, printing is black and white, and music isn't. A musician has to peer through the limitations of notation to hear a live person, the composer, then bring that composer's ideas to life in the performer's world. The further back one goes in time, the more necessary it is to accept that the composer's world can never exist again - too much of that world has been lost to truly recreate it. My approach is to study sources as close as possible to the time, apply the rules of the time, use instruments of the time, then let my ears be the guide, based on the whole oeuvre of the composer.

Byrd is the earliest composer with whom I feel my method is reliable - his music can mostly be understood by modern ears, as mine of course are. Faced with the new concept of solo keyboard music, restricted to a small selection of fixed pitches in contrast to the flexibility of prior vocal practise, Byrd grasped two essential elements of its nature, regular rhythm paired with consonance, with remarkable sureness. (By contrast, John Bull fought the fixed pitch restriction fiercely all his life.) Most of Byrd's keyboard music is based upon dance, and the human body has not changed. So, if you feel impelled to motion as you stand and listen, at least part of Byrd's world has been recreated in yours.

I admit, however, that with music as early as Byrd, I remain uncertain as to the treatment of modal modulation. Modern players instinctively pause at such points, viewing them as breaks in what the music is saying. I have, with some uncertainty, refrained from this, mostly on the grounds that such modulations are often found in rapid sequence within passages where pauses seem inappropriate. Also, the construction of music within the modal system and meantone tuning often seems to be a combinatoric exercise, rather than an emotional one. (I don't believe for a minute that popular music of the time was treated this way in the village square!)

The tuning I use is quarter-comma meantone, one in which thirds are pure in common keys. Music of this period modulates in mode rather than in key, and this tuning was used more often than any other at that time. English instruments then had a more powerful treble and more evanescent bass than my instrument, as well as those used as the model for most MIDI harpsichords, so I reduce the volume of the bass notes in the files to partially compensate.

My sources are shown in brackets: NE numbers are those in Nevell, PA in Parthenia, FW in FitzWilliam, MB Musica Britannica.